- Collaboration for Development Members

- What's New

Blog » Editorial essay: Covid‐19 and protected and conserved areas

Editorial essay: Covid‐19 and protected and conserved areas

- Protected Areas

- Conservation

- Restoration

- Ecosystem Services

- Biodiversity

- Deforestation

Read the full article

| Title | Editorial essay: Covid‐19 and protected and conserved areas |

| Organization | WWF - Marc Hockings, Nigel Dudley, Wendy Ellio, Mariana Napolitano Ferreira and others. |

| Language | English |

| Year | 2020 |

| File type | |

| Keywords English | Amazon, biodiversity, Brazil, Colombia, Peru, conservation, deforestation, ecosystem services, indigenous, protected areas, restoration. |

| Palabras clave Español | Amazonía, biodiversidad, Brasil, Colombia, Perú, conservación, deforestación, servicios ecosistémicos, indígenas, áreas protegidas, restauración. |

| Palavras-chave Português | Amazônia, biodiversidade, Brasil, Colômbia, Peru, conservação, desmatamento, serviços ecossistêmicos, povos indígenas, áreas protegidas, restauração. |

|

These publications are shared by our members and are meant for knowledge exchange. The content and findings of the publications do not reflect the views of the World Bank Group, the ASL and its partners, and the sole responsibility for these publications lies with the authors. | |

EXPLORE OUR CONTENT

- 5. Employment and Skills Development. (1)

- Indigenous (27)

- Conservation (31)

- Rural Livelihoods (1)

- Publications and Research (1)

- tourism (1)

- Biodiversity (30)

- Bolivia (3)

- Mining (21)

- COVID-19 (2)

- wetlands (1)

- Restoration (21)

- Brazil (34)

- Agriculture (1)

- wildlife (1)

- Deforestation (32)

- Ecosystem Services (19)

- Colombia (37)

- Ecuador (3)

- Sustainable Finance (1)

- Protected Areas (24)

- Finance (1)

- Local Economic Development (1)

- Governance (7)

- Venezuela (1)

- Landscapes (12)

- Climate Change (3)

- Conflict (7)

- Webinars (1)

- Environment (1)

- Suriname (1)

- Amazon (58)

- 2019 August (4)

- 2019 October (3)

- 2019 November (3)

- 2019 December (25)

- 2020 January (1)

- 2020 February (18)

- 2020 March (1)

- 2020 April (3)

- 2020 May (9)

- 2020 June (6)

- 2020 July (2)

- 2020 August (15)

- 2020 October (9)

- 2021 March (3)

- 2021 September (2)

- 2021 November (1)

- 2021 December (8)

- 2022 March (4)

- 2022 April (9)

- 2022 August (1)

- 2022 September (1)

- 2022 December (5)

- 2023 March (3)

- 2023 April (1)

- 2023 May (1)

- 2023 June (10)

- 2023 July (2)

- 2023 October (1)

- 2024 February (3)

A full-text copy of this article may be available. Please email the WCS Library to request.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Perspective

- Published: 29 July 2020

Conserving Africa’s wildlife and wildlands through the COVID-19 crisis and beyond

- Peter Lindsey ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9197-2897 1 , 2 , 3 ,

- James Allan 4 ,

- Peadar Brehony ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1315-7683 5 ,

- Amy Dickman 6 ,

- Ashley Robson ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6433-0602 7 ,

- Colleen Begg 8 ,

- Hasita Bhammar 9 ,

- Lisa Blanken 10 ,

- Thomas Breuer ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8387-5712 11 ,

- Kathleen Fitzgerald 12 ,

- Michael Flyman 13 ,

- Patience Gandiwa 14 ,

- Nicia Giva 15 ,

- Dickson Kaelo 16 ,

- Simon Nampindo 17 ,

- Nyambe Nyambe ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1275-0178 18 ,

- Kurt Steiner ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4686-0375 19 ,

- Andrew Parker 20 ,

- Dilys Roe ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6547-6427 21 , 22 ,

- Paul Thomson ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9566-3293 3 ,

- Morgan Trimble ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9914-0788 23 ,

- Alexandre Caron ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5213-3273 24 , 25 &

- Peter Tyrrell ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9599-8138 26 , 27

Nature Ecology & Evolution volume 4 , pages 1300–1310 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

40k Accesses

167 Citations

519 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Conservation biology

- Environmental studies

This article has been updated

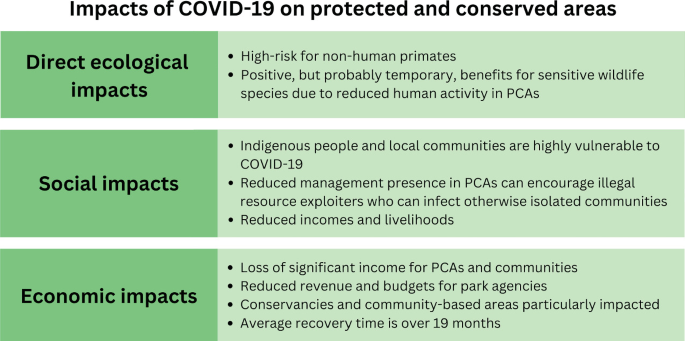

The SARS-CoV-2 virus and COVID-19 illness are driving a global crisis. Governments have responded by restricting human movement, which has reduced economic activity. These changes may benefit biodiversity conservation in some ways, but in Africa, we contend that the net conservation impacts of COVID-19 will be strongly negative. Here, we describe how the crisis creates a perfect storm of reduced funding, restrictions on the operations of conservation agencies, and elevated human threats to nature. We identify the immediate steps necessary to address these challenges and support ongoing conservation efforts. We then highlight systemic flaws in contemporary conservation and identify opportunities to restructure for greater resilience. Finally, we emphasize the critical importance of conserving habitat and regulating unsafe wildlife trade practices to reduce the risk of future pandemics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Global opportunities and challenges for transboundary conservation

Global shortfalls in documented actions to conserve biodiversity

Caught in the crossfire: biodiversity conservation paradox of sociopolitical conflict

The world is currently facing a major disease pandemic due to SARS-CoV-2 and its associated illness, COVID-19 1 . Governments are taking drastic steps to stem disease spread, including international travel restrictions and lockdowns of hundreds of millions of people. These measures are having massive socioeconomic impacts, as businesses and industries halt or scale back operations. The world’s stock markets have become volatile, and a global recession is imminent. Virtually all sectors of life are affected and will likely remain so for at least 6–12 months 2 . Africa’s economy could suffer from reductions in foreign investment, reduced inflows of remittances and foreign aid, and lower overall earnings 3 . Gross domestic products (GDPs) may contract by 4%, and governments face reduced tax revenues and devalued currencies, resulting in severe budget deficits and knock-on effects on African livelihoods 4 . Lockdown restrictions and economic turmoil could also compromise conservation of Africa’s immensely valuable wildlife and wildlands, and the people who benefit from them.

Africa has nearly 2,000 Key Biodiversity Areas and supports the world’s most diverse and abundant large mammal populations 5 , 6 . Financially, the most apparent value of Africa’s wildlife and wildlands stems from wildlife-based tourism, which generates over US$29 billion annually and employs 3.6 million people 7 . Trophy hunting, a subset of the tourism industry, generates an estimated ~US$217 million annually over >1 million km 2 (refs. 8 , 9 ). Tourism helps governments justify protecting wildlife habitat. It creates revenue for state wildlife authorities, generates foreign exchange earnings, diversifies and strengthens local economies, and contributes to food security and poverty alleviation (Table 1 ). Tourism generates 40% more full-time jobs per unit investment than agriculture, has twice the job creation power of the automotive, telecommunications and financial industries, and employs proportionally more women than other sectors 10 .

Africa’s wildlife also attracts considerable foreign investment via funding for conservation efforts (Table 1 ). Contributors range from multilateral institutions and bilateral funding agencies to private foundations, philanthropists, zoos and non-governmental organizations (NGOs). Reliable data on the scale and composition of donor funding are scarce, but external support makes up a substantial proportion of the total funding for wildlife conservation (Table 1 ). For example, donor contributions account for 32% of protected area (PA) funding in Africa, reaching 70–90% in some countries 11 .

Wildlands and conservation areas provide critical resources for local people who benefit from using wildlife, grass, water, firewood and non-timber forest products. During times of distress such as economic downturns, people rely more heavily on such resources 12 . In addition, Africa’s wildlife provides important cultural and heritage values for multiple ethnic groups, and charismatic species have extensive symbolic value internationally 13 . Africa’s wildlife also holds considerable ‘existence’ value—the value people derive from simply knowing it exists 14 .

The state of African conservation

The backbone of African conservation efforts is made up of 7,800 terrestrial PAs covering 5.3 million km 2 , ~17% of the continent’s land area 15 . PA coverage in some countries (notably in southern and East Africa) far exceeds the global average. In parts of Africa, vast transfrontier conservation areas transcend national borders, creating protected landscapes spanning hundreds of thousands of square kilometres. Most PAs are state-owned and managed by government wildlife authorities, often with substantial support from tourism and hunting operators 16 . Increasingly, conservation NGOs and private sector entities cooperate with governments to manage state-owned PAs through collaborative management partnerships (CMPs) 17 . In addition, conservation efforts on private and community lands have grown in recent years 18 , 19 , expanding wildlife habitat, buffering PAs, reducing edge-effects, improving ecosystem representation, securing seasonal migration areas, and meaningfully engaging and benefiting rural communities that live with wildlife 20 , 21 , 22 . In Namibia, community conservancies account for 170,000 km 2 , and in South Africa, game ranches cover 205,000 km 2 , both exceeding the land area encompassed by state PAs 19 , 23 . Community-based conservation (CBC) programmes have grown in the last 20 years, supporting millions of rural African livelihoods 22 , 24 .

Despite impressive political commitment to conservation in Africa, the continent suffers severe and persistent funding shortages that hinder management effectiveness. Africa’s state-owned savannah PAs with lions face recurrent budget deficits of US$1.2 billion per annum, rendering wildlife susceptible to threats, while forest PAs are likely no better protected 11 . Key threats include habitat loss, degradation, fragmentation, encroachment, poaching and climate change 25 , 26 , 27 . These factors, combined with poor governance, poverty, increasing human populations and illegal wildlife trade, continue to drive wildlife declines across the continent 11 , 28 , 29 , 30 . In particular, the loss of large mammals compromises ecosystem function 31 , 32 . Thus, with few localized exceptions, African conservation was in crisis even before COVID-19 hit. The pandemic could amplify the crisis to catastrophic effect.

Environmental impacts of the COVID-19 crisis

Researchers have documented some positive environmental outcomes of the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, reduced industrial activity and mechanized transport have lowered emissions and air pollution worldwide 33 . Some Asian countries (notably China and Vietnam) have taken steps to restrict trade that threatens wildlife. If regulated and enforced over the long term, such restrictions could reduce poaching in Africa for illegally sourced products that supply Asian markets. Gabon has banned consumption of bats and pangolins following the COVID-19 crisis 34 . Transport restrictions due to lockdowns may curb trade in wildlife products and provide respite for PAs that suffer negative impacts of tourist congestion.

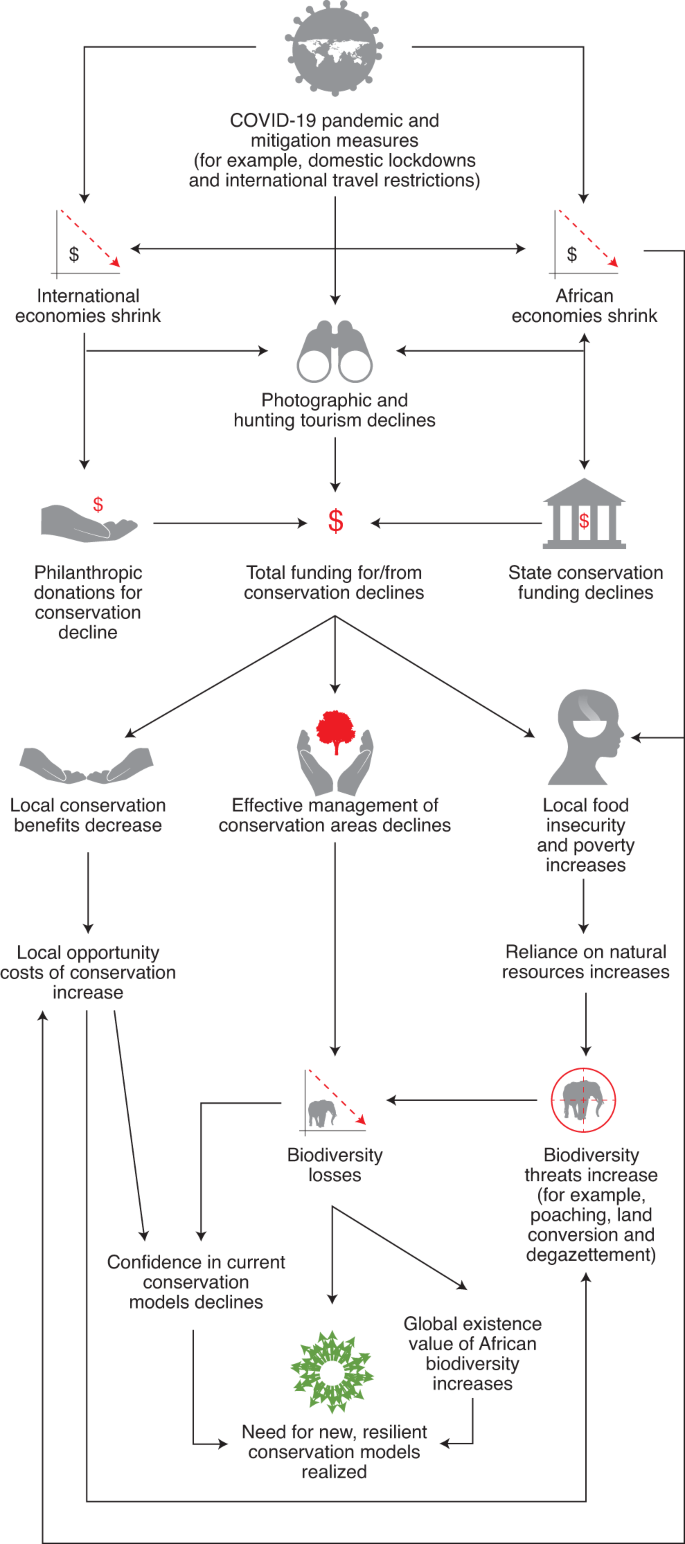

These positive environmental outcomes are likely temporary and prone to reversal when travel restrictions ease and countries return to business as usual. We argue that the net environmental impact of the COVID-19 crisis in Africa will be strongly negative because the crisis creates a ‘perfect storm’ of reduced funding, lower conservation capacity, and increased threats to wildlife and ecosystems (Fig. 1 ). Wildlife conservation arguably faces its most serious challenge in decades.

Arrows indicate the directionality of potential impacts among different elements in Africa’s conservation framework.

Reduced conservation funding

Governments face severe budget crises driven by the economic fallout of the COVID-19 pandemic and the cost of relief measures. Shortages will compel policymakers to cut anything perceived as ‘non-essential’ 4 . African wildlife authority budgets, already grossly inadequate, risk being slashed further, jeopardizing wildlife and wildlands.

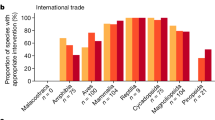

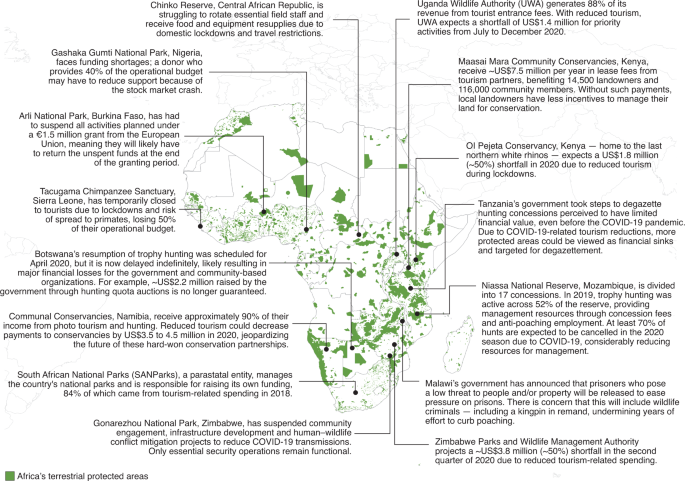

Compounding these effects is the continent-wide collapse of wildlife-based tourism due to travel restrictions and traveller concerns (Fig. 2 ; Table 1 ). While previous shocks, for example, the 2014 Ebola epidemic and the 2008 financial crisis, markedly reduced tourism in some African countries, the negative, continent-wide impacts of COVID-19 on the industry are unprecedented in scale and severity 35 . Some 90% of African tour operators have experienced >75% declines in bookings 36 . Because tourism is the largest contributor to PA financing in some countries, lost revenues have major ramifications for state wildlife authorities, private concessionaires and landowners, and community conservation programmes (Figs. 1 and 2 ) 37 . Decreasing tourism revenue threatens millions of jobs and peripheral industries, severely impacting the livelihoods of some of the continent’s poorest people (Box 1 ). For nations less reliant on wildlife tourism for conservation (for example, in the forest biome), the impact will be lower. However, if the industry is slow to bounce back, under-visited PAs developing nascent tourism products may be the last to see visitors.

‘Africa’s terrestrial protected areas’ refers to all nationally gazetted, terrestrial protected areas in Africa 15 . The source of each example is shown in Supplementary Table 1 .

Beyond tourism revenue losses, we expect reduced donor funding for African conservation over the next 1–2 years and possibly longer due to flagging economies and shifting priorities. During the previous global financial crisis, total charitable giving in the United States dropped by 7% in 2008 and 6.2% in 2009 38 , and conservation endowments declined in value by 40% 39 . The current economic downturn and stock market volatility, to an even greater degree, may reduce capacity of private donors, corporations and foundations to give philanthropically. Restrictions on travel and gatherings have caused cancellation and postponement of key conferences and conservation fund-raising events. Many zoos are closed, and reduced revenues will likely limit support for in situ conservation efforts. The pandemic will also shift focus from conservation towards humanitarian causes. Some bi- and multilateral donor agencies increased funding to developing countries in response to the 2008 financial crisis 40 , but the extent of the current economic and humanitarian challenges is such that any additional funding would likely be directed at those realms. Some emergency conservation funding is being organized in response to the crisis 36 , though it will likely fall far short of offsetting losses.

Box 1 Impact of COVID-19 on local communities and conservation threats

People living on the periphery of PAs are often food-insecure, neglected by governments and heavily dependent on natural resources 96 . However, they are the users of and potential custodians of natural resources. They bear costs of conservation (for example, through human–wildlife conflict, exclusion from natural resources, and, in some cases, loss of land), often without receiving commensurate benefits. For several decades, community-based conservationists have tested economic and engagement models to empower local communities to own and manage natural resources in the ecosystems where they live 97 .

The COVID-19 crisis challenges these models. Impacts on community-based conservation and the tourism industry have massive economic implications for communities 3 . Loss of tourism and trophy hunting revenue can increase opportunity costs of conservation and the risk of land conversion. The sudden loss of wildlife-based revenue could erode communities’, private landowners’, and even governments’ confidence in wildlife conservation as a reliable land-use option. Movement restrictions and social-distancing rules curtail engagement between conservation groups and communities, compromising hard-won trust with local people 98 .

Besides the loss of tourism revenue, rural communities face financial hardship from the wider economic turmoil wrought by the COVID-19 pandemic and governmental responses. In some areas, livestock markets have closed, cutting off revenue streams for rural communities. Nearly 20 million jobs are at risk on the continent if the crisis continues 3 . Following lockdown-driven unemployment, people may return to rural homes, as has been observed for transnational labourers, many of whom returned to communities next to PAs near international borders 99 .

Increased poverty and food insecurity will likely increase conservation threats. In the absence of financial capital reserves, food-insecure rural Africans could be attracted to the periphery of PAs to draw upon natural resources 100 . Anticipated effects include increased poaching, tree cutting for timber and charcoal, artisanal mining, PA encroachment by people and livestock, and conversion of natural habitat 101 . We expect the threat posed by the increase in consumption of bushmeat to be particularly severe, with anecdotal evidence reported from Tsavo East National Park ( https://go.nature.com/32rNQYH ). These threats will coincide with reduced funding, operational ability, and field presence of community conservancies, state wildlife authorities, private landowners, conservation NGOs, and tourism and hunting companies.

Following the emergency response to the crisis in the periphery of PAs, new models linking conservation and local development will be needed.

Impaired conservation operations

Reduced funding is likely to constrain the ability of conservation practitioners to manage PAs and other conservation landscapes, force lay-offs of key staff, and prevent purchase of critical supplies 35 (Figs. 1 and 2 , Box 1 ). In addition, COVID-related restrictions on people’s movements undermine the ability of practitioner agencies to undertake their conservation work, as reported by the author group’s extended network of field colleagues (Figs. 1 and 2 ). Some lockdown policies in African countries prevent all but ‘essential services’. Generally, anti-poaching seems to be permitted, but rotating staff and supplying field rangers with essential consumables may be disrupted, resulting in exhaustion and reduced morale of rangers (Figs. 1 and 2 ). Policies that prevent operations and activities deemed non-essential could have considerable impacts on community conservation, which often relies on regular meetings, interactions and collaboration among a variety of actors, often without access to remote communication technology (Box 1 ).

Increased conservation threats

Natural resources and the ecosystems that produce them face heightened pressure due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Plummeting tourism revenue and negative economic impacts of the pandemic will likely increase rural poverty. Simultaneously, COVID-19-related restrictions and budget constraints will impair conservation operations. Consequently, as detailed in Fig. 1 and Box 1 , we expect increased poaching, tree cutting, artisanal mining, PA encroachment, agricultural conversion and possibly the ultimate degazettement of the most-affected PAs. With many ecosystems and wildlife populations already near tipping points, the current crisis may result in population declines, local extinctions of some species, and intensified disruptions of ecological processes 6 .

Risk of future outbreaks due to human impacts on nature

The COVID-19 pandemic, like the SARS-CoV 1 and Ebola epidemics, likely originated from human consumption of wild animals. Live wildlife markets create opportunities for pathogens to infect naïve domestic species or humans and trigger new diseases 41 , 42 . In Africa, particularly in the tropical forest biome, bushmeat markets expose human populations to species identified as high risk for pathogen spillover, such as primates, bats and rodents 43 . The combined effects of reduced conservation efforts and increased poverty could create a positive feedback loop where intensified reliance on natural resources spurs human encroachment into natural habitats, increases exposure to and consumption of wild animals, and amplifies future pandemic risks 44 . Conversely, effective conservation of species and habitats has been directly linked to decreases in the number of viruses that animals share with humans 45 . Adapted disease surveillance systems, especially for the wildlife–domestic–human interface, need to be developed and supported in emergence hotspots 46 .

How can the world mitigate these risks?

The conservation crisis facing Africa must not be overlooked, even as governments and NGOs respond to the health and humanitarian crisis. While the current focus on health and the economy is critical, a longer-term perspective is vital. Supporting conservation efforts will help national and local African economies recover from the devastating impacts of COVID-19 by diversifying and bolstering economies, creating employment for rural citizens, and protecting ecosystem services. Safeguarding wild habitats against encroachment can also help tackle a key root cause of emerging zoonotic diseases, lessening future pandemic risks. Reducing support for African conservation at this critical juncture could undo decades of progress. Here, we describe steps necessary to safeguard African wildlife and landscapes and associated rural populations during and beyond the COVID-19 crisis. We outline actions needed to (1) manage the immediate crisis; (2) tackle environmental destruction and address the ongoing threats of habitat destruction and illegal, unsustainable and/or unsafe wildlife trade; and (3) address systemic flaws in the current conservation model.

1. Manage the immediate crisis

African conservation will flounder unless the international community intervenes to provide crisis funding, recognizing conservation as an essential service and PAs as global public goods. The developed world is rapidly implementing mechanisms to bail out impacted businesses and industries, which in the United States runs into trillions of dollars. However, cash-strapped governments in developing countries lack such potential. Furthermore, no such mechanisms exist for supporting conservation specifically. Donors could unite to create an emergency fund for struggling wildlife authorities, communities, private landowners and conservation NGOs. In addition, key industries underpinning conservation efforts, such as tourism, need support, both via tax breaks and direct financial assistance, provided they can demonstrate ongoing investment into protection of the wildlands on which they depend. Realistically, the developed world would have to be the primary source of such funding, from multi- and bilateral institutions, corporations and the public. International philanthropic foundations have an opportunity to intervene, make a transformational difference to conservation in Africa and help avert disaster.

Business as usual will not be possible for most conservation practitioners during the crisis. They will require strategic planning to prioritize critical activities and minimize risks of ‘overstretching’. They should emphasize maintaining crucial operations and retaining as many members of staff as possible, such that they can expand again when the crisis abates. Conservation practitioners and large NGOs in particular must cut wastage and excesses. NGOs should prioritize salaries for staff in Africa where possible, noting that salary protection schemes do not generally exist on the continent.

2. Defend against future disease outbreaks by regulating wildlife trade and minimizing habitat loss

China and Vietnam have taken steps to restrict trade and consumption of wildlife in response to the COVID-19 outbreak. Worldwide, governments and organizations should improve regulations and enforce existing laws to clamp down on unsafe wildlife trade practices that jeopardize human health or conservation objectives. Trade restrictions should be appropriate, proportionate and enacted with local buy-in and political commitment. Otherwise, unsustainable or dangerous trade may resume as soon as the immediate crisis abates. Efforts to stamp out unsafe and unsustainable practices should not, however, undermine legal components of the wildlife trade industry that are or could be well regulated, pose a controlled disease-transmission risk and support millions of livelihoods 47 .

In addition to addressing the disease-transmission risk of the wildlife trade, governments and organizations should tackle the other critical drivers of infectious disease emergence including habitat destruction, which can be driven by industrial livestock production 44 , 48 . In forest regions of the continent, logging and mining are encroaching into remote areas 49 , 50 , likely facilitating disease spread into and amongst human populations, as seen in the Amazon 51 . Forest regions urgently require flexible funding mechanisms to prevent the sale of forest concessions and construction of development corridors through and unsustainable resource extraction from natural habitats. Such steps could also help protect Indigenous peoples from disease and from losing ancestral lands.

3. Address systemic flaws in the structure and function of conservation in Africa

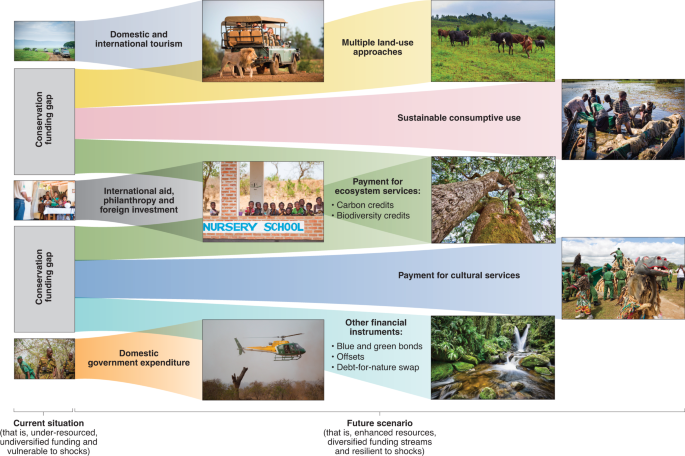

The COVID-19 crisis has highlighted the fragility of conservation efforts in Africa and has exposed fundamental shortcomings (Fig. 3 ).

Enhancing the magnitude and diversity of funding could increase resilience and efficacy. For more detail, see Table 2 . Photograph credit: Morgan Trimble.

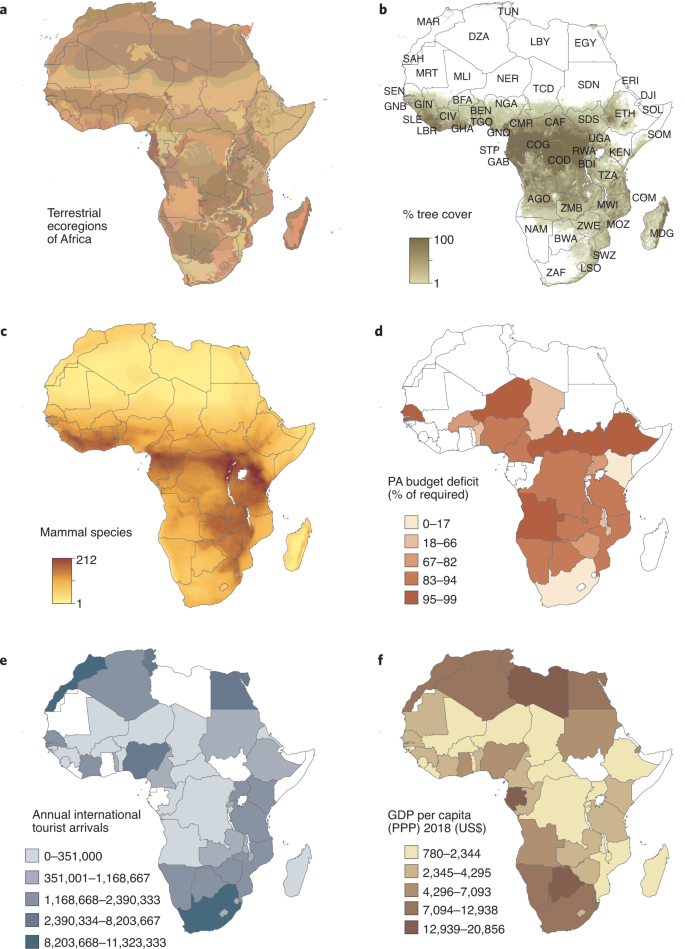

Baseline funding for conservation from African governments is simply inadequate. Many nations struggle with high poverty rates and do not have the luxury and the wealth to conserve African wildlife and wildlands alone. Currently, overreliance on short term, ad hoc external funding streams (including philanthropy) is unsustainable and insecure. Many PAs rely on a single, inadequate funding source. Tourism is a promising but insufficient source of conservation funding. Some African countries’ overreliance on international tourism to support conservation creates vulnerability to stochastic events. Few hold sufficient funds in reserve to finance conservation operations through hard times. Other countries do not benefit substantially from wildlife-based tourism at all (Fig. 4 ). Where tourism does flourish, the communities bearing the costs of wildlife often receive negligible benefits, disincentivizing conservation.

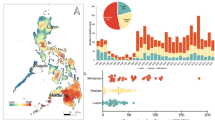

a , The terrestrial ecoregions of Africa 91 . b , Percentage tree cover with >10% canopy density in 2000 92 (source: Hansen/UMD/Google/USGS/NASA). Countries are labelled with their ISO-3 codes. c , Mammal species richness 93 . d , Funding deficits of national protected area networks in African lion range states 11 . e , The average number of annual international tourist arrivals to African countries from 2016–2018 94 . f , The GDP per capita (corrected for purchasing power parity (PPP)) in current US dollars of African countries in 2018 95 . In d – f , countries are filled white where data were unavailable, and values were classified using the Jenks natural breaks method.

There is also a lack of sufficient, long-term, systematic support for African conservation from the Global North, who benefit considerably from Africa’s wildlife and lands, without contributing sufficiently towards its costs. Relative to their wealth, some African countries carry a disproportionately high burden from their conservation efforts and so, the international community should provide support at commensurate levels, recognizing that Africa’s natural treasures are global assets; environmental services from Africa benefit the world through carbon sequestration; and African ecosystems play a critical role in safeguarding human mental and physical health 11 , 12 , 13 , 52 .

Most fundamentally, there is insufficient alignment between conservation and human-development agendas. Here, we outline emerging opportunities to rethink and restructure conservation funding in Africa to improve long-term resilience (Fig. 3 ).

Increase the resilience of conservation

Africa is diverse, presenting an array of contexts in which conservation must be practised. Thus, the solutions we suggest must be tailored appropriately (Fig. 4 ).

3a. Recognize the reliance of development on natural assets

Effective long-term conservation in Africa depends on finding sufficient funding and building political and public will. Aligning conservation and development interests could help on both fronts. African economies depend considerably on ecosystem services, so this alignment can be supported in several ways, for example:

Quantify the value of natural assets and ecosystem services and incorporate those values into national budgets, balance sheets, and planning for natural resource use to reinforce the value of conservation.

Position PAs in their broader landscapes as hubs for local development, service provision and even disaster relief. This has been achieved via collaborative management partnerships for some African PAs 17 , 24 .

Properly engage local people as stakeholders in conservation. Inside PAs, create forums that enable communities to participate in PA governance and ensure communities benefit from tourism to strengthen engagement. Outside PAs, promote policies that devolve resource and wildlife utilization rights to communities to support sustainable management and strengthen institutions that allow communities to optimize their economic opportunities 53 .

Encourage conservation organizations to work with development specialists on visible support for core community livelihoods, such as livestock and crop production, thereby earning public backing and increasing resilience of local communities to shocks such as the COVID-19 pandemic 22 . For example, if conservation organizations provide security or markets for livestock, local people would link those benefits to conservation; the ‘herding for health’ programme is testing this approach in northern Kenya and southern Africa 54 .

3b. Support African civil society conservation efforts

With international conservation organizations limited by travel restrictions, there is an opportunity for national conservation organizations and civil society efforts to fill gaps. International partners should support local people and services by providing funding and sharing expertise remotely. Once the crisis has subsided, local conservation capacity will have increased and could continue to be supported, together with revived efforts by international NGOs.

3c. Diversify revenue-generating options from wildlife areas

The volatility of international tourism and decline in trophy hunting demonstrate the need to create local revenue streams that are resilient to global shocks (Fig. 3 , Table 2 ). Only a handful of African countries earn substantial wildlife tourism revenue 16 . Others need to unlock tourism potential by investing in infrastructure and wildlife protection and creating an enabling environment for tourism 55 , 56 (Fig. 3 , Table 2 ). Conversely, some southern and East African nations heavily reliant on international tourism should foster domestic tourism to increase resilience to global shocks and build longer-term public support for conservation 57 , 58 . With the trophy hunting industry apparently waning, due in part to pressure from Western anti-hunting advocates, PAs that currently depend on trophy hunting revenue should seek alternative income streams 59 . Given the existing serious funding deficits for conservation in Africa (Fig. 4 ), collapse of the trophy hunting industry in the absence of alternatives carries grave ramifications for conservation across vast areas 16 , 59 . Wealthier countries must contribute towards alternative and improved revenue-generating mechanisms to help pay for the management and opportunity costs of Africa’s vast network of semi-protected areas. In some contexts, livestock or sustainable use of wildlife can be compatible with conservation 60 , 61 . In South Africa, a biodiversity economy strategy promotes bioprospecting and game ranching for hunting and meat-, skin- and leather exports as key revenue streams complementing eco-tourism 62 . Africa is developing at a rapid pace, and governments should use the ‘biodiversity mitigation hierarchy’ to diminish ecological damage and mandate offset payments to generate sustainable revenue for conservation 63 .

3d. Increase domestic expenditure

Ultimately, for wildlife and wildlands to deliver on their economic potential, African governments must invest sufficiently to protect their own assets. After the crisis subsides, African nations could identify a set budgetary allocation for the protection of nature, similar to the 2003 Maputo Declaration on Agriculture and Food Security. National governments could also establish endowment funds with the help of foreign investment, mandate a biodiversity mitigation hierarchy, and develop green and blue bonds.

3e. Increase international funding

While greater domestic investment is desirable, substantially more financial support is needed beyond this. Emerging mechanisms for international governments, corporations, individuals and NGOs to provide funding include investments in PAs and community land, payments for ecosystem and cultural services, and debt-for-nature swaps (Table 2 ).

3f. Improve revenue distribution mechanisms

Africa needs improved mechanisms to effectively generate and disburse wildlife-related revenue and offset the opportunity, indirect and direct costs of wildlife. Such mechanisms need to recognize the role of governments, private landowners, and communities in Africa as custodians of global wildlife assets. Examples include: (1) direct payments by wealthy countries to African nations for setting aside wilderness, such as the payments made by Norway to Gabon 64 ; (2) land leases, whereby land is leased from owners and set aside for conservation to prevent conversion to less biodiversity friendly land use, as occurs, for example, in conservancies around the Maasai Mara 65 ; (3) biodiversity stewardship programmes that pay or incentivize landowners to practice conservation-friendly land management; (4) performance payment schemes that reward local people for conserving wildlife (as is being trialled in Mozambique, Namibia and Tanzania, for example, http://wildlifecredits.com ); (5) ‘conservation basic incomes’ that compensate communities who protect nature 66 ; and (6) schemes and actions that reduce the cost of coexisting with wildlife 67 .

Conclusions

The COVID-19 crisis threatens conservation efforts in Africa with a ‘perfect storm’ of reduced conservation funding, depleted management capacity, collapse of community-based natural resource management enterprises, and elevated threats. The crisis demands a concerted international effort to protect and support Africa’s wildlife and wildlands and people that are dependent on them. African governments, the international community, donors and conservation practitioners should collaborate through decisive effort and adaptive management to minimize negative impacts. At this critical juncture, business as usual could be catastrophic, but decisive and collaborative action can ensure that Africa’s wildlife survives COVID-19 and that more resilient conservation models benefit humans and wildlife for generations.

Change history

15 december 2021.

In the version of this article initially published online, the Supplementary Information file was incomplete, and has been restored.

COVID-19 Dashboard (JHU CSSE, 2020); https://go.nature.com/39lfrey

Ferguson, N., Laydon, D., Nedjati-Gilani, G. & Imai, N. Impact of Non-Pharmaceutical Interventions (Npis) to Reduce COVID-19 Mortality and Healthcare Demand (Imperial College London, 2020); https://go.nature.com/3j8qjSv

Impact of Coronavirus (COVID-19) on the African Economy (African Union, 2020); https://icsb.org/covid19ontheafricaneconomy/

Jayaram, B. K., Leke, A., Ooko-ombaka, A. & Sun, Y. S. Tackling COVID-19 in Africa: An Unfolding Health and Economic Crisis that Demands Bold Action (McKinsey & Company, 2020).

Wolf, C. & Ripple, W. J. Prey depletion as a threat to the world’s large carnivores. R. Soc. Open Sci. 3 , 160252 (2016).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Ripple, W. J. et al. Collapse of the world’s largest herbivores. Sci. Adv. 1 , e1400103 (2015).

The Economic Impact of Global Wildlife Tourism - Travel and Tourism As An Economic Tool For The Protection Of Wildlife (World Travel and Tourism Council, 2019).

Lindsey, P. A., Roulet, P. A. & Romañach, S. S. Economic and conservation significance of the trophy hunting industry in sub-Saharan Africa. Biol. Conserv. 134 , 455–469 (2007).

Article Google Scholar

di Minin, E., Leader-Williams, N. & Bradshaw, C. J. A. Banning trophy hunting will exacerbate biodiversity loss. Trends Ecol. Evol. 31 , 99–102 (2016).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Building a Wildlife Economy (Space for Giants, UNEP & Conservation Capital, 2019); https://go.nature.com/2ZDrwt2

Lindsey, P. A. et al. More than $1 billion needed annually to secure Africa’s protected areas with lions. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115 , E10788–E10796 (2018).

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Galvani, A. P., Bauch, C. T., Anand, M., Singer, B. H. & Levin, S. A. Human-environment interactions in population and ecosystem health. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113 , 14502–14506 (2016).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Stolton, S. & Dudley, N. The New Lion Economy: Unlocking the Value of Lions (Equilibrium Research, 2019); www.lionrecoveryfund.org/newlioneconomy

Macdonald, E. A. et al. Conservation inequality and the charismatic cat: Felis felicis . Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 3 , 851–866 (2015).

The World Database on Protected Areas (WDPA) (UNEP-WCMC & IUCN, 2019); www.protectedplanet.net

Lindsey, P. A., Balme, G. A., Funston, P. J., Henschel, P. H. & Hunter, L. T. B. Life after Cecil: channelling global outrage into funding for conservation in Africa. Conserv. Lett. 9 , 296–301 (2016).

Baghai, M. et al. Models for the collaborative management of Africa’s protected areas. Biol. Conserv. 218 , 73–82 (2018).

Mills, M. et al. How conservation initiatives go to scale. Nat. Sustain. 2 , 935–940 (2019).

Taylor, W. A., Lindsey, P. A., Nicholson, S. K., Relton, C. & Davies-Mostert, H. T. Jobs, game meat and profits: the benefits of wildlife ranching on marginal lands in South Africa. Biol. Conserv. 245 , 108561 (2020).

Western, D., Russell, S. & Cuthill, I. The status of wildlife in protected areas compared to non-protected areas of Kenya. PLoS ONE 4 , e6140 (2009).

Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar

Riggio, J., Jacobson, A. P., Hijmans, R. J. & Caro, T. How effective are the protected areas of East Africa? Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 17 , e00573 (2019).

Western, D. et al. Conservation from the inside‐out: winning space and a place for wildlife in working landscapes. People Nat. 2 , 279–291 (2020).

The State of Community Conservation in Namibia (NACSO, 2018); https://go.nature.com/30jMLiL

Pringle, R. M. Upgrading protected areas to conserve wild biodiversity. Nature 546 , 91–99 (2017).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Strindberg, S. et al. Guns, germs, and trees determine density and distribution of gorillas and chimpanzees in Western Equatorial Africa. Sci. Adv. 4 , eaar2964 (2018).

Lindsey, P. A. et al. Underperformance of African protected area networks and the case for new conservation models: insights from Zambia. PLoS ONE 9 , e94109 (2014).

Ogutu, J. O. et al. Extreme wildlife declines and concurrent increase in livestock numbers in Kenya: what are the causes? PLoS ONE 11 , e0163249 (2016).

Craigie, I. D. et al. Large mammal population declines in Africa’s protected areas. Biol. Conserv. 143 , 2221–2228 (2010).

Maisels, F. et al. Devastating decline of forest elephants in Central Africa. PLoS ONE 8 , e59469 (2013).

Robson, A. S. et al. Savanna elephant numbers are only a quarter of their expected values. PLoS ONE 12 , e0175942 (2017).

Dirzo, R. et al. Defaunation in the Anthropocene. Science 345 , 401–406 (2014).

Hempson, G. P., Archibald, S. & Bond, W. J. The consequences of replacing wildlife with livestock in Africa. Sci. Rep. 7 , 17196 (2017).

Airborne Nitrogen Dioxide Plummets over China (NASA Earth Observatory, 2020); https://go.nature.com/397mtEl

Gabon Bans Eating of Pangolin and Bats amid Pandemic (AFP, 2020).

Spenceley, A. COVID-19 and Protected Area Tourism: A Spotlight on Impacts and Options in Africa (World Trade Organization, 2020).

Hockings, M. et al. Editorial essay: COVID‐19 and protected and conserved areas. Parks 26 , 7–24 (2020).

Spenceley, A., Snyman, S. & Eagle, P. F. J. Guidelines for Tourism Partnerships and Concessions for Protected Areas: Generating Sustainable Revenues for Conservation and Development (IUCN, 2017); https://go.nature.com/3hapGpK

Reich, R. & Wimer, C. Charitable Giving and the Great Recession. Recession Trends (Stanford Center on Poverty and Inequality, 2012).

Martin, M. Managing Philanthropy after the Downturn: What is Ahead for Social Investment? 10–21 (Viewpoint, 2010).

te Velde, D. W. & Massa, I. Donor Responses to the Global Financial Crisis – A Stock Take Global Financial Crisis Discussion Series (Overseas Development Institute, 2009).

Daszak, P., Cunningham, A. A. & Hyatt, A. D. Anthropogenic environmental change and the emergence of infectious diseases in wildlife. Acta Tropica 78 , 1–14 (2001).

Markotter, W., Coertse, J., de Vries, L., Geldenhuys, M. & Mortlock, M. Bat-borne viruses in Africa: a critical review. J. Zool. 311 , 77–98 (2020).

Olival, K. J. et al. Host and viral traits predict zoonotic spillover from mammals. Nature 546 , 646–650 (2017).

Di Marco, M. et al. Sustainable development must account for pandemic risk. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117 , 3888–3892 (2020).

Johnson, C. K. et al. Global shifts in mammalian population trends reveal key predictors of virus spillover risk. Proc. R. Soc. B 287 , 20192736 (2020).

Jones, K. E. et al. Global trends in emerging infectious diseases. Nature 451 , 990–993 (2008).

Broad, S. Wildlife Trade, COVID-19, and Zoonotic Disease Risks (TRAFFIC, 2020).

Karesh, W. B. et al. Ecology of zoonoses: natural and unnatural histories. Lancet 380 , 1936–1945 (2012).

Edwards, D. P. et al. Mining and the African environment. Conserv. Lett. 7 , 302–311 (2014).

Kleinschroth, F., Healey, J. R., Gourlet-Fleury, S., Mortier, F. & Stoica, R. S. Effects of logging on roadless space in intact forest landscapes of the Congo Basin. Conserv. Biol. 31 , 469–480 (2017).

Castro, M. C. et al. Development, environmental degradation, and disease spread in the Brazilian Amazon. PLoS Biol. 17 , e3000526 (2019).

Green, J. M. H. et al. Local costs of conservation exceed those borne by the global majority. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 14 , e00385 (2018).

Zahia, B. et al. Voices of the communities: a new deal for rural communities and wildlife and natural resources. in Africa’s Wildlife Economy Summit 1–13 (UNEP, 2019).

Heyl, A. Herding for Health (Univ. Pretoria, 2017).

Closing the gap. The financing and resourcing of protected and conserved areas in Eastern and Southern Africa . Jane’s Defence Weekly (IUCN ESARO, 2020).

Naidoo, R., Fisher, B., Manica, A. & Balmford, A. Estimating economic losses to tourism in Africa from the illegal killing of elephants. Nat. Commun. 7 , 13379 (2016).

The Bio-economy Strategy (Department of Science and Technology, 2013); https://go.nature.com/2DLxAaw

Economic Crisis, International Tourism Decline and its Impact on the Poor (World Tourism Organization & International Labour Organization, 2013); https://go.nature.com/3hdpJkF

Dickman, A., Cooney, R., Johnson, P. J., Louis, M. P. & Roe, D. Trophy hunting bans imperil biodiversity. Science 365 , 874 (2019).

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar

Lindsey, P. A. et al. Benefits of wildlife-based land uses on private lands in Namibia and limitations affecting their development. Oryx 47 , 41–53 (2013).

Keesing, F. et al. Consequences of integrating livestock and wildlife in an African savanna. Nat. Sustain. 1 , 566–573 (2018).

National Biodiversity Economy Strategy (Department of Environmental Affairs, 2016); https://go.nature.com/2B81bKt

The Mitigation Hierarchy (Forest Trends, 2020); https://go.nature.com/3h7Folf

Dahir, A. L. Gabon will be paid by Norway to preserve its forests. Quartz (23 September 2019).

Bedelian, C. Conservation and Ecotourism on Privatised Land in the Mara, Kenya: The Case of Conservancy Land Leases LDPI Working Paper 9 (The Land Deal Politics Initiative, 2012).

Buscher, B. & Fletcher, R. Towards convivial conservation. Conserv. Soc. 17 , 283–296 (2019).

Dickman, A. J., Macdonald, E. A. & Macdonald, D. W. A review of financial instruments to pay for predator conservation and encourage human-carnivore coexistence. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108 , 13937–13944 (2011).

Balmford, A. et al. Walk on the wild side: estimating the global magnitude of visits to protected areas. PLoS Biol. 13 , e1002074 (2015).

Annual Report 2017 (Kenya Wildlife Service, 2017); https://go.nature.com/3jdHli4

State of Wildlife Conservancies in Kenya (KWCA, 2016).

Tumusiime, D. M. & Vedeld, P. False promise or false premise? Using tourism revenue sharing to promote conservation and poverty reduction in Uganda. Conserv. Soc. 10 , 15–28 (2012).

Annual Performance Plan 2018/2019 (South African National Parks, 2018); https://go.nature.com/32qNxx7

Naidoo, R. et al. Complementary benefits of tourism and hunting to communal conservancies in Namibia. Conserv. Biol. 30 , 628–638 (2016).

Analysis of International Funding to Tackle Illegal Wildlife Trade. Analysis of International Funding to Tackle Illegal Wildlife Trade (World Bank Group, 2016); https://doi.org/10.1596/25340

2018 Annual Report on Conservation and Science (Association of Zoos and Aquariums, 2018); https://go.nature.com/30n8Dd1

The Northern Rangeland Trust State of Conservancies Report 2018 (NRT, 2018).

Our Gorongosa – A Park for the People (The Gorongosa Project, 2019); https://go.nature.com/393Wwpe

Financials (WWF, 2019); https://go.nature.com/30iFT5n

Consolidated Financial Statements (African Wildlife Foundation, 2019); https://go.nature.com/392BUOm

Annual Report - Unlocking the Value of Protected Areas (African Parks, 2018); https://www.africanparks.org/unlocking-value-protected-areas

2018 Annual Report (Sheldrick Wildlife Trust, 2018).

COVID-19 Update: Taking Action in Unprecedented Times (Association of Zoos and Aquariums, 2020).

Lott, L. et al. Aid for Museums Impacted by Coronavirus (International Council of Museums, 2020).

Damania, R., Scandizzo, P. L., Mikou, M., Gohil, D. & Said, M. When Good Conservation Becomes Good Economics: Kenya’s Vanishing Herds (The World Bank, 2019).

Malhi, Y. et al. Climate change and ecosystems: threats, opportunities and solutions. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 375 , 20190104 (2020).

Article CAS Google Scholar

Roberts, C. M., O’Leary, B. C. & Hawkins, J. P. Climate change mitigation and nature conservation both require higher protected area targets. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 375 , 20190121 (2020).

Good, C., Burnham, D. & Macdonald, D. W. A cultural conscience for conservation. Animals 7 , 52 (2017).

Article PubMed Central Google Scholar

Munevar, D. A Debt Moratorium for Low Income Economies (Eurodad, 2020); https://www.cadtm.org/A-debt-moratorium-for-Low-Income-Economies

Lamble, L. Africa leads calls for debt relief in face of coronavirus crisis. The Guardian (25 March 2020).

Seychelles Debt Conversion for Marine Conservation and Climate Adaptation (Convergence, 2017).

Olson, D. M. et al. Terrestrial ecoregions of the world: a new map of life on Earth. BioScience 51 , 933–938 (2001).

Hansen, M. et al. High-resolution global maps change, 21st-century forest cover. Science 850 , 850–854 (2013).

Jenkins, C. N., Pimm, S. L. & Joppa, L. N. Global patterns of terrestrial vertebrate diversity and conservation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110 , E2603–E2610 (2013).

International Tourism, Number of Arrivals World Development Indicators (The World Bank, 2020); https://go.nature.com/2CNGAva

GDP per capita, PPP (current international $) World Development Indicators (The World Bank, 2020); https://go.nature.com/3h9zdxk

Barrow, E. & Fabricius, C. Do rural people really benefit from protected areas - rhetoric or reality? Parks 12 , 67–79 (2002).

Google Scholar

Dressler, W. et al. From hope to crisis and back again? A critical history of the global CBNRM narrative. Environ. Conserv. 37 , 5–15 (2010).

Mease, L. A., Erickson, A. & Hicks, C. Engagement takes a (fishing) village to manage a resource: principles and practice of effective stakeholder engagement. J. Environ. Manag. 212 , 248–257 (2018).

Chirindza, J. 23,000 Mozambicans return to the country in the last 24 hours. O País (26 March 2020).

Guerbois, C. & Fritz, H. Patterns and perceived sustainability of provisioning ecosystem services on the edge of a protected area in times of crisis. Ecosyst. Serv. 28 , 196–206 (2017).

Lindsey, P. A. et al. The performance of African protected areas for lions and their prey. Biol. Conserv. 209 , 137–149 (2017).

Download references

Acknowledgements

A.C. and N.G. were supported by the EU funded ‘ProSuLi in TFCAs’ project (FED/20 I 7/ 394 -443) and the research platform RP-PCP ( www.rp-pcp.org ). A.D. was supported by a fellowship from the Recanati-Kaplan Foundation.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Mammal Research Institute, Department of Zoology and Entomology, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa

Peter Lindsey

Environmental Futures Research Institute, Griffith University, Nathan, Queensland, Australia

Wildlife Conservation Network, San Francisco, CA, USA

Peter Lindsey & Paul Thomson

Institute for Biodiversity and Ecosystem Dynamics (IBED), University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

James Allan

Department of Geography, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK

Peadar Brehony

University of Oxford, Tubney, UK

Amy Dickman

Institute for Communities and Wildlife in Africa, Department of Biological Science, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa

Ashley Robson

TRT Conservation Foundation, Rondebosch, South Africa

Colleen Begg

World Bank, Washington, DC, USA

Hasita Bhammar

Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH, Eschborn, Germany

Lisa Blanken

WWF Germany, Berlin, Germany

Thomas Breuer

Conservation Capital, Nairobi, Kenya

Kathleen Fitzgerald

Department of Wildlife and National Parks, Gaborone, Botswana

Michael Flyman

International Conservation Affairs Department, Parks and Wildlife Management Authority, Harare, Zimbabwe

Patience Gandiwa

Faculty of Agronomy and Forestry Engineering, Universidade Eduardo Mondlane, Maputo, Mozambique

Kenya Wildlife Conservancies Association, Nairobi, Kenya

Dickson Kaelo

Wildlife Conservation Society, Uganda Country Programme, Kampala, Uganda

Simon Nampindo

Kavango Zambezi Transfrontier Conservation Area Secretariat, Kasane, Botswana

Nyambe Nyambe

Independent consultant, Johannesburg, South Africa

Kurt Steiner

Conserve Africa, Johannesburg, South Africa

Andrew Parker

International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED), London, UK

IUCN Sustainable Use and Livelihoods Specialist Group (SULi), London, UK

Independent consultant, Cape Town, South Africa

Morgan Trimble

ASTRE, Uni Montpellier, CIRAD, INRA, Montpellier, France

Alexandre Caron

Faculdade de Veterinaria, Universidade Eduardo Mondlane, Maputo, Mozambique

South Rift Association of Landowners, Nairobi, Kenya

Peter Tyrrell

Department of Geography and Environmental Studies, University of Nairobi, Nairobi, Kenya

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

P.L., J.A., P.B., A.D., A.R., C.B., H.B., L.B., T.B., K.F., M.F., P.G., N.G., D.K., S.N., N.N., K.S., A.P., D.R., P. Thomson, M.T., A.C. and P. Tyrrell contributed to conceptualizing, writing and editing the paper.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Peter Lindsey .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information.

Supplementary Table 1 and references.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Lindsey, P., Allan, J., Brehony, P. et al. Conserving Africa’s wildlife and wildlands through the COVID-19 crisis and beyond. Nat Ecol Evol 4 , 1300–1310 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-020-1275-6

Download citation

Received : 22 April 2020

Accepted : 13 July 2020

Published : 29 July 2020

Issue Date : October 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-020-1275-6

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Food safety-related practices among residents aged 18–75 years during the covid-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study in southwest china.

- Zhourong Li

BMC Public Health (2024)

Building resilience in primate tourism: insights from the COVID-19 pandemic and future directions

- Lori K. Sheeran

- Lene Pedersen

Primates (2024)

Mammal responses to global changes in human activity vary by trophic group and landscape

- A. Cole Burton

- Christopher Beirne

- Roland Kays

Nature Ecology & Evolution (2024)

Post-2020 biodiversity framework challenged by cropland expansion in protected areas

- Jinwei Dong

- Xiangming Xiao

Nature Sustainability (2023)

Effects of global shocks on the evolution of an interconnected world

- Andrés Viña

- Jianguo Liu

Ambio (2023)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

COVID-19 and protected areas: Impacts, conflicts, and possible management solutions

Affiliations.

- 1 Department of Land Economy, University of Cambridge Conservation Research Institute University of Cambridge Cambridge UK.

- 2 Snowdonia National Park Authority Penrhyndeudraeth Wales UK.

- 3 Department of Environment University of the Aegean Mytilene Greece.

- PMID: 34230839

- PMCID: PMC8250896

- DOI: 10.1111/conl.12800

During the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, management authorities of numerous Protected Areas (PAs) had to discourage visitors from accessing them in order to reduce the virus transmission rate and protect local communities. This resulted in social-ecological impacts and added another layer of complexity to managing PAs. This paper presents the results of a survey in Snowdonia National Park capturing the views of over 700 local residents on the impacts of COVID-19 restrictions and possible scenarios and tools for managing tourist numbers. Lower visitor numbers were seen in a broadly positive way by a significant number of respondents while benefit sharing issues from tourism also emerged. Most preferred options to manage overcrowding were restricting access to certain paths, the development of mobile applications to alert people to overcrowding and reporting irresponsible behavior. Our findings are useful for PA managers and local communities currently developing post-COVID-19 recovery strategies.

Keywords: Wales; biodiversity conservation; lockdown; overcrowding; protected areas management; social impacts; visitors.

© 2021 The Authors. Conservation Letters published by Wiley Periodicals LLC.

PubMed Disclaimer

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest

Life during lockdown for locals…

Life during lockdown for locals in Snowdonia National Park (Spring 2020): Positive and…

Impact of COVID‐19 restrictions linked…

Impact of COVID‐19 restrictions linked with the National Park

Preferences for different tools managing…

Preferences for different tools managing overcrowding in Snowdonia National Park

Similar articles

- The nature of the pandemic: Exploring the negative impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic upon recreation visitor behaviors and experiences in parks and protected areas. Ferguson MD, Lynch ML, Evensen D, Ferguson LA, Barcelona R, Giles G, Leberman M. Ferguson MD, et al. J Outdoor Recreat Tour. 2023 Mar;41:100498. doi: 10.1016/j.jort.2022.100498. Epub 2022 Feb 28. J Outdoor Recreat Tour. 2023. PMID: 37521260 Free PMC article.

- Protected area management effectiveness and COVID-19: The case of Plitvice Lakes National Park, Croatia. Mandić A. Mandić A. J Outdoor Recreat Tour. 2023 Mar;41:100397. doi: 10.1016/j.jort.2021.100397. Epub 2021 Jun 3. J Outdoor Recreat Tour. 2023. PMID: 37521258 Free PMC article.

- The threat of COVID-19 to the conservation of Tanzanian national parks. Ranke PS, Kessy BM, Mbise FP, Nielsen MR, Arukwe A, Røskaft E. Ranke PS, et al. Biol Conserv. 2023 Jun;282:110037. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2023.110037. Epub 2023 Apr 3. Biol Conserv. 2023. PMID: 37056580 Free PMC article.

- Tourism, biodiversity and protected areas--Review from northern Fennoscandia. Tolvanen A, Kangas K. Tolvanen A, et al. J Environ Manage. 2016 Mar 15;169:58-66. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2015.12.011. Epub 2015 Dec 22. J Environ Manage. 2016. PMID: 26720330 Review.

- Ten factors that affect the severity of environmental impacts of visitors in protected areas. Pickering CM. Pickering CM. Ambio. 2010 Feb;39(1):70-7. doi: 10.1007/s13280-009-0007-6. Ambio. 2010. PMID: 20496654 Free PMC article. Review.

- Mobile phone data reveals spatiotemporal recreational patterns in conservation areas during the COVID pandemic. Kim JY, Kubo T, Nishihiro J. Kim JY, et al. Sci Rep. 2023 Nov 20;13(1):20282. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-47326-y. Sci Rep. 2023. PMID: 37985851 Free PMC article.

- Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on SCUBA diving experience in marine protected areas. Marconi M, Giglio VJ, Pereira-Filho GH, Motta FS. Marconi M, et al. J Outdoor Recreat Tour. 2023 Mar;41:100501. doi: 10.1016/j.jort.2022.100501. Epub 2022 Mar 3. J Outdoor Recreat Tour. 2023. PMID: 37521255 Free PMC article.

- Tourism as a Tool in Nature-Based Mental Health: Progress and Prospects Post-Pandemic. Buckley RC, Cooper MA. Buckley RC, et al. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022 Oct 12;19(20):13112. doi: 10.3390/ijerph192013112. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022. PMID: 36293691 Free PMC article. Review.

- Marine reserves and resilience in the era of COVID-19. King C, Adhuri DS, Clifton J. King C, et al. Mar Policy. 2022 Jul;141:105093. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2022.105093. Epub 2022 May 6. Mar Policy. 2022. PMID: 35540179 Free PMC article.

- Bibliometric Analysis of Post Covid-19 Management Strategies and Policies in Hospitality and Tourism. Khan KI, Nasir A, Saleem S. Khan KI, et al. Front Psychol. 2021 Nov 15;12:769760. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.769760. eCollection 2021. Front Psychol. 2021. PMID: 34867674 Free PMC article. Review.

- Agresti, A. (2010). Analysis of ordinal categorical data (2nd ed.) Hoboken N.J: Wiley.

- Ban, N. C. , Gurney, G. G. , Marshall, N. A. , Whitney, C. K. , Mills, M. , Gelcich, S. , Bennett, N. J. , … Tran, T. C. (2019). Well‐being outcomes of marine protected areas. Nature Sustainability, 2(6), 524–532. 10.1038/s41893-019-0306-2 - DOI

- Bennett, N. J. (2016). Using perceptions as evidence to improve conservation and environmental management. Conservation Biology, 30, 582–592. 10.1111/cobi.12681 - DOI - PubMed

- Bennett, N. J. , DiFranco, A. , Calò, A. , Nethery, E. , Niccolini, F. , Milazzo, M. , & Guidetti, P. (2019). Local support for conservation is associated with perceptions of good governance social impacts and ecological effectiveness. Conservation. Letters, 12, e12640. 10.1111/conl.12640 - DOI

- Bennett, N. J. , Finkbeiner, E. M. , Ban, N. C. , Belhabib, D. , Jupiter, S. D. , Kittinger, J. N. , … Christie, P. (2020). The COVID‐19 pandemic, small‐scale fisheries and coastal fishing communities. Coastal Management, 48(4), 336–347. 10.1080/08920753.2020.1766937 - DOI

Related information

Linkout - more resources, full text sources.

- Europe PubMed Central

- PubMed Central

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

How COVID-19 is Affecting the World’s Protected and Conserved Areas

Global Wildlife Conservation (GWC) changed its name to Re:wild in 2021

A global publication outlines the strains the pandemic is putting on parks – and the opportunities for new ways of thinking.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, many of us have turned to nature to relieve stress and improve our mental health. A stroll through a park or forest can feel like a much-needed escape from sheltering in place. At the same time, this outbreak has reminded us that nature is not separate from humanity – our fates are intertwined. Whether we live in urban or rural areas, the planet is our home. The coronavirus came from our encroachment upon wildlife and wildlands, and now our response to it is putting severe stress on our world’s protected and conserved areas.

Protected and conserved areas such as national parks make up at least 15% of the world’s land surface . These areas provide refuge for plants and animals, biodiverse buffers against climate change, homes for Indigenous Peoples and livelihoods for local communities. In a paper released in the latest issue of PARKS, The International Journal of Protected Areas and Conservation , 35 conservationists compiled a comprehensive account of how protected and conserved areas around the world are being impacted by COVID-19. GWC Director of Protected Area Management Mike Appleton and GWC Senior Director of Species Conservation Dr. Barney Long, are among the paper’s authors.

“Across the global protected area community, we realized pretty quickly that COVID-19 was going to have some serious impacts,” says Appleton. “We had a strong desire to give a ‘state of the parks’ report early on so we can be aware of the problems as well as opportunities for new types of action and new ways of thinking when we come out on the other side of this.”

After gathering data and updates from members of the World Commission on Protected Areas and partners at parks all over the world, the paper’s authors found humans’ changing patterns of movement, spending and resource consumption are straining parks.

Declining revenues, budgets and staff

Lockdowns and travel restrictions have significantly decreased tourism to many protected and conserved areas. A recent survey of African safari tour operators found over 90% had experienced a 75% or greater decline in bookings and many had no bookings at all. Tourism employs 16 million people in Africa, either directly or indirectly, and represents the main income source for many families.

This loss of income from tourism is unlikely to be short-lived: a study by Global Rescue and the World Travel and Tourism Council (2019) found the average time from impact to economic recovery of tourism following disease outbreaks was 19.4 months. This major loss of tourism revenue has caused many parks to cut staff and programs.

At the same time, many governments are reallocating funds from their environmental budgets to pay for pandemic response.

“Coronavirus is a massive emergency, but this is a short-sighted approach,” says Long. “All the zoonotic disease outbreaks over the last decades have come from the wild because that human/wild interface is expanding. Protected areas are the cornerstone of protecting the wild, so pulling funding is the exact opposite of what we need to do.”

Budget cuts mean rangers and other staff have to do more with less . Some protected areas, especially community conservancies and privately protected areas that depend heavily on tourism to pay staff salaries, have had to reduce enforcement capacity. They’ve also had to abandon or postpone monitoring and routine management tasks. And in some areas rangers are being diverted to distribute food or transport personal protective equipment to places of need.

Increased human reliance on parks

At the same time, many parks are seeing increased pressures that need monitoring and enforcement – and that can lead to degradation of land and threats to species over time.

There are increased reports of illegal resource extraction in many countries. In Nepal for example, more cases of illegal extraction of forest resources, such as illicit logging and harvesting, took place in the first month of lockdown (514 cases) than in the entire previous year (483 cases). Hard data on poaching trends during the lockdown is not yet widely available, and while some areas are seeing relief, others are reporting increases. For example, six musk deer were killed in Sagarmatha National Park, Nepal, in one of the worst recent cases of wildlife poaching in the region.

Another source of pressure comes from more people turning to parks to fulfill their basic needs, from food to fuel wood. After losing their jobs, many city dwellers have returned to their family homes in villages near parks. And many living in those villages have also lost income streams.

“Natural resources are usually an insurance policy in times of hardship for people close to the poverty line,” Long says. And we've seen millions, if not billions of people across the world fall into times of hardship. Historically, that wouldn't have been a problem, but now we've got so few natural resources left, and lots of them are concentrated in these parks.”

Additionally, while many protected areas are suffering from lack of tourism revenue, widespread closures have put increased visitor pressures on those remaining open.

Addressing short-term needs

GWC works with protected and conserved areas worldwide to develop long-term conservation strategies for both wildlife and wildlands. Right now, our focus is on helping with emergency response and filling critical gaps while respecting the needs of our Indigenous partners. In many parks, Indigenous residents have closed their territory to the outside world to protect themselves. This is true of the residents of Mounts Iglit-Baco Natural Park in the Philippines, with whom we’re working to save the Tamaraw , a Critically Endangered wild dwarf buffalo.

“We are relying on text messages and WhatsApp messages through intermediaries and doing our best,” Appleton says. While we can’t do fieldwork right now, there are a lot of other jobs we can do to help our partners, including developing reports, systems and processes; conducting studies; writing project proposals; fundraising; and making sure everyone's well and looked after and okay.”

Looking at long-term recovery

The PARKS paper lays out three scenarios for long-term recovery: a return to normal, a global economic depression and decline in conservation and protection, or a new and transformative relationship with nature. It is too early to predict which scenarios will play out in various regions around the world.

The global nature of the COVID-19 pandemic can make this overwhelming. But it also provides an opportunity: parks and organizations can share information and best practices. The paper recommends several calls to action, noting that effectively, equitably managed networks of well-connected protected and conserved areas provide one of the most important ways In which to strengthen and repair the relationship between people and the natural systems on which they depend. A focus on equity not only recognizes the rights and ownership of Indigenous Peoples, but it can also provide stability going forward.

“The systems we’ve established to manage many parks are incredibly vulnerable because as soon as funding streams are cut off, they start to fail,” says Appleton. “At GWC we’re focused on co-management arrangements, where Indigenous Peoples and local people are managers, supported by or in partnership with government agencies. In many cases, it’s the most effective, most cost-efficient and sustainable way of doing it.”

GWC will be working with the World Commission on Protected Areas to explore long-term recovery solutions. In April, we launched the Coalition to End the Trade with Wildlife Conservation Society and WildAid to prevent the next pandemic by permanently ending the commercial trade and sale in markets of terrestrial wild animals (particularly birds and mammals), for consumption.

Taking action every day: what you can do

Many people wonder what they can do to make a difference. The first thing is to visit your nearest park as soon as you’re able to do so. Be a responsible visitor by staying on trails, practicing social distancing, wearing a face covering and following the park’s guidelines. And if you see a ranger, thank them – they’re the essential workers of our planet.

“The wild is essential to our future well-being. Not only for the sake of the plants and animals. It’s great therapy for people who've been living stressed existences for months, and is also as an insurance against this happening again. It’s important to enjoy it and to tell other people, decision-makers, that it's important to you,” says Appleton.

(Top photo by Robin Moore, Global Wildlife Conservation)

About the author

Erica Hess is a strategic content writer specializing in sustainability and corporate social responsibility. Erica enjoys telling stories about people finding new ways to protect our planet’s vital resources. Her work has helped raise awareness of issues ranging from overfishing to electronics recycling. Learn more at plumemarketing.com.

Related News and Other Stories

By Mike Appleton on September 25, 2018

Plotting A Future For The Wildlife Of Redonda Island

By Lindsay Renick Mayer on July 23, 2019

Grassroots Plan Sprouts to Protect the Forests of Indio Maíz

cannot display this part of the Library website. Please visit our browser compatibility page for more information on supported browsers and try again with one of those.

- News & Events

- Eastern and Southern Africa

- Eastern Europe and Central Asia

- Mediterranean

- Mexico, Central America and the Caribbean

- North America

- South America

- West and Central Africa

- IUCN Academy

- IUCN Contributions for Nature

- IUCN Library

- IUCN Red List of Threatened Species TM

- IUCN Green List of Protected and Conserved Areas

- IUCN World Heritage Outlook

- IUCN Leaders Forum

- Protected Planet

- Union Portal (login required)

- IUCN Engage (login required)

- Commission portal (login required)

Data, analysis, convening and action.

- Open Project Portal

- SCIENCE-LED APPROACH

- INFORMING POLICY

- SUPPORTING CONSERVATION ACTION

- GEF AND GCF IMPLEMENTATION

- IUCN CONVENING

- IUCN ACADEMY

The world’s largest and most diverse environmental network.

CORE COMPONENTS

- Expert Commissions

- Secretariat and Director General

- IUCN Council

- IUCN WORLD CONSERVATION CONGRESS

- REGIONAL CONSERVATION FORA

- CONTRIBUTIONS FOR NATURE

- IUCN ENGAGE (LOGIN REQUIRED)

IUCN tools, publications and other resources.

Get involved

Conserving Nature in a time of crisis: Protected Areas and COVID-19

Many of the threats facing biodiversity and protected areas will be exacerbated during, and following, the Covid-19 outbreak. The health of humans, animals and ecosystems are interconnected. An expanding agricultural frontier and human incursions into natural areas for logging, mining and other purposes has led to habitat loss and fragmentation, increased contact between human and wildlife and greater exploitation and trade of wild animal products. This enables the spread of diseases from animal populations to humans who have little or no resistance to them; Covid-19 is just the latest and most widespread of these zoonotic pandemics, following SARS, MERS and Ebola.

Photo: IUCN / Charles Besancon

Protected and conserved areas are key to maintaining healthy ecosystems, protecting diverse natural habitats and wild species; terrestrial protected areas now cover more than 15% of the world’s land surface. But PAs are not just about wildlife or biodiversity, important though these are. When governed and managed effectively, they also support human health and well-being, contributing to food and water security, disaster risk reduction, climate mitigation and adaptation, and local livelihoods. Globally there is increasing recognition of these wider benefits (IPBES 2019), but these contributions of well-managed protected areas are still often undervalued, or ignored, when it comes to practical policy or development decisions.

This global pandemic will have both immediate and longer-term effects on protected and conserved areas. The pandemic has already resulted in the closure of parks and protected areas in many countries, resulting in a cascade of impacts:

- Park staff being sent home to self-isolate or even being laid off. Many park agencies are already cutting staff duties. Because staffing levels are key to protected area effectiveness, this can have serious impacts on conservation of key habitats and species.

- Closure of protected areas to people for tourism and recreation. Many protected areas have been closed to visitors. For example, World Heritage sites have been completely closed to visitation in 72 percent of the 167 countries with listed sites, though anti-poaching patrols, monitoring and emergency interventions may continue. [i]

- Concerns that charismatic threatened species may be susceptible to the virus has led to closures of areas supporting gorillas and other great ape populations [ii] .

- Suspension of protected area management and restoration programmes, including fire management, invasive alien species control, and species re-introductions. In Australia, efforts to restore park habitats damaged during the catastrophic wildfires are now on hold.

- Reduced revenue from tourism and cuts in park operational budgets. This can be especially challenging for private protected areas and community conservancies. For example, in the Mara Nabisco Conservancy in Kenya, tourism revenue that provided the salaries of 40 rangers has ceased entirely [iii] and the closure of local businesses linked to tourism has resulted in the loss of employment and livelihoods for over 600 Maasai families.

- Suspension of ranger patrols is widespread in some parts of the world, with the resulting possibility of environmentally-damaging activities, including agricultural encroachment, illegal logging and poaching. There are already emerging reports of increased poaching and illegal resource extraction in countries such as Cambodia [iv] , India [v] , South Africa and Botswana [vi] linked to loss of rural livelihoods and reduced capacity to conduct patrols and fieldwork by enforcement staff [vii] .