- Corpus ID: 143047626

College Admissions Essays: A Genre of Masculinity

- Published 2010

- Young Scholars In Writing

One Citation

School leadership: implicit bias and social justice, related papers.

Showing 1 through 3 of 0 Related Papers

Nathan's Writ 101 Blog

Thursday, september 25, 2014, college admissions essays: a genre of masculinity (response), no comments:, post a comment.

Wallace Casper

Thursday, september 25, 2014, college admissions essays: a genre of masculinity response, no comments:, post a comment.

New Perspectives on the Anglophone World

Home Issues 3 Reading, Writing and the “Straigh...

Reading, Writing and the “Straight White Male”: What Masculinity Studies Does to Literary Analysis

This article aims at mapping out some of the ways in which masculinity studies has recently renewed the critical approach to certain literary texts. It argues that this fairly new disciplinary field has helped to de-territorialize literary inquiry and challenges deep-rooted assumptions about reading and writing. Essentialist notions like “masculine writing,” bodily analogies between the pen and the phallus, and psychoanalytical tools such as the Oedipus myth have tended to obfuscate the multitude of masculine identities at work in literature. Combined with the textual and performative approach developed by queer theorists, the work done by historians of masculinity enables, for instance, to shed light on the pressures that burdened authorial identity in a context of homophobia like the Cold War period in the United States, to delineate the ways in which the constitutive homosociality of poetic circles in the 1950s fashioned their aesthetic norms and practices, and to deconstruct the narrative codes and the fictions of masculinity which structured certain literary genres like the crime novel and the adventure novel.

Cet article se propose d’examiner la façon dont les études sur la masculinité ont récemment permis de renouveler l’approche de certains textes littéraires. Il défend l’idée que ce champ disciplinaire relativement nouveau a permis de déterritorialiser l’épistémologie littéraire et d’interroger certains présupposés qui structurent l’approche critique de l’écriture et de la lecture. Qu’il s’agisse de notions essentialistes telles que « l’écriture masculine », des analogies corporelles entre stylo et phallus ou de certains outils psychanalytiques comme le mythe d’Œdipe, l’analyse littéraire du genre est parfois restée aveugle à la multiplicité d’identités masculines à l’œuvre en littérature. Conjugué à l’approche textuelle et performative formulée par les théoriciens queer, le travail des historiens de la masculinité permet par exemple de rendre visible les pressions qui s’exercent sur l’identité auctoriale dans un contexte d’homophobie généralisée comme celui de la Guerre froide aux Etats-Unis, de comprendre comment l’homosocialité constitutive des cercles poétiques des années 1950 façonne leurs normes et leurs pratiques esthétiques et de déconstruire les codes narratifs et les fictions du masculin qui structurent certains genres littéraires comme le roman noir et le roman d’aventure.

Index terms

Mots-clés : , keywords: .

“To be a successful reader in the academy, it was argued, was to learn to read as a straight white male, at the cost of fidelity to one’s actual experience of life.” Geoff Hall (95)

1 Drawing on feminism, gender studies and queer theory, the field of masculinity studies emerged in American academia in the early 1990s, mostly as a reaction against the anti-feminist men’s movements that were then enjoying a significant popularity in the United States. Its avowed goal was to map out in detail the history of a gender that had not received the critical attention necessary to a better understanding of gender relations. As it had been the center, the norm from which all other gender identities had been defined, masculinity had always remained invisible as such, an invisibility that had been central to its successfully maintaining a hegemonic and privileged position. Rooted in the assumption that gender is historically contingent and culturally constructed, scholars in the field set out to refine our understanding of the normative principles, narrative strategies, epistemological categories and power relations which have structured the experience and representation of masculinity. In particular, they insisted on the performative, relational, prosthetic, homosocial and plural dimension of masculine identity. Yet, since masculinity studies has been predominantly concerned with establishing a historiographical account of men as men, its impact on literary studies has remained somewhat limited.

2 Reading both male- and female-authored texts from this particular vantage point enables to raise a series of questions that cast literary analysis in a new light. What does it mean to write or read as “a straight white male”? What gendered assumptions are entrenched in our interpretive practices? Haven’t we all, men and women, black and white, straight and queer, learned to interpret texts as “straight white males”? And what does it mean to read otherwise? What is significantly lacking from contemporary literary analysis is a questioning of the way we continue, as readers of literary works and authors of literary analysis, to heavily rely on definitions of notions like sign, style, trope, genre or narrative that were developed within a critical tradition that was blind to questions of gender and uninformed by queer theory. Especially in France, where the intellectual sway of structuralist thought, the universalist ideals of Republicanism and the post-May 1968 backlash against theory have worked together to maintain women’s studies, LGBT studies, gender studies, feminist theory and queer theory in a marginal status, literary analysis has been constituted as an autonomous, self-legitimating field with specific questions and methods, often at the cost of social or political import and impact. I would suggest that a more refined understanding of masculinity and of the way it has shaped literary epistemology can produce insightful and refreshing readings.

3 The point here, therefore, is not to rehash the now formulaic idea that the literary canon is mostly composed of “dead white European men” as the phrase goes (and as true as it may be), or to simply analyze the “representation” of masculinity (though it may prove fruitful), or to be satisfied with just “contextualizing” literary works in a gendered perspective (however useful it may prove), but to underline the importance of disciplinary disaffiliation and deterritorialization in order to question and transform our textual practices as readers, teachers and researchers. Since masculinity studies only exists as a supplement to feminism, gender studies, LGBT studies and queer theory (and a whole series of other disciplines), it participates in further de-compartmentalizing academic fields without ever successfully reclaiming a critical master-narrative. Viewing literary texts through the prism of masculinities (and vice versa) opens up new questions and provides crucial answers which can reinvigorate the field of literary analysis and challenge our most deeply rooted assumptions about reading and writing.

1. Masculinity studies, or reading the norm

- 1 The mid-1990s saw the almost simultaneous publication of Manliness and Civilization (1996) by Gai (...)

- 2 Among the encyclopedias, see for instance Flood (2007), Carroll (2003), and Kimmel and Aronson (2 (...)

- 3 See for instance Fergusson (2009). It should also be noted that an international conference entit (...)

4 Although it is possible to trace antecedents in the late 1970s and 1980s (Joseph H. Pleck’s The Myth of Masculinity published in 1981 and Harry Brod’s The Making of Masculinity in 1987), masculinity studies only emerged as a separate and autonomous field of research in the mid-1990s. 1 It originated first and foremost in American academia, finding few echoes in Europe (with the exception of Scandinavian countries), and it originally was essentially the product of the work of historians, sociologists and psychologists. Since then, various encyclopedias about men have been published; several publications are dedicated to the study of men and masculinity; associations of scholars working on the question have been created around the world; book series have been launched on the subject; and more recently, under the direction of Michael Kimmel, the Center for the Study of Men and Masculinities was established at Stony Brook University where the first Master’s Degree in Masculinity Studies was launched in September 2016. 2 In France, with the notable exceptions of Pierre Bourdieu’s La Domination masculine (1998), Elisabeth Badinter’s XY: de l’identité masculine (1992) and several sociological studies by Daniel Welzer-Lang, all of which met with extensive and justified criticisms, there was only sporadic academic research on the question until the mid-2000s, leaving the field of masculinity open to uninformed approaches like Eric Zemmour’s Le Premier sexe (2006). Though a significant amount of research has been done in France since then, it has overwhelmingly originated from the area of film studies, practitioners of literary analysis remaining largely uninterested in the question. 3

5 Besides the analysis of what feminist historians and philosophers had already described in so many terms—from “patriarchy” or “phallo(go)centrism” to “masculine domination” and “male hegemony,” here are the interrelated paradigms that have defined the field of masculinity studies:

Masculinity is the privilege of invisibility. By being the center, the norm from which all other identities proceed, masculinity has remained largely invisible as such. Although library shelves are packed with books that narrate the “great deeds” of “great men,” those historical narratives never questioned the way being male has influenced and structured the lives, actions and thoughts of these men. To put it differently, men had no history as men and the aim of critical studies of men and masculinities, therefore, has been “to turn attention to men in a way that renders them and their practices visible, apparent and subject to question, and to undertake this examination with an explicit political intent” (qtd. in Flood 402).

Masculinity is a historical construct . As such, it encompasses a wide array of representations and experiences that differ from one culture, historical period or social class to another. As historian Rotundo puts its, “manhood is not a social edict determined on high and enforced by law. As a human invention, manhood is learned, used, reinforced, and reshaped by individuals in the course of life” (7). In other words, to paraphrase Simone de Beauvoir’s famous claim, one is not born a man, but rather becomes a man. Masculinity studies thus argues that the masculine gender has little to do with the male biological sex or with physical phenotypic features, but is essentially the product of cultural codes, social norms and ideological imperatives which vary across time and space.

Masculinity is multiple and variable . Masculinity studies emphasizes the multiplicity of masculine identities at work in any culture, something which was for a long time hidden by the somewhat homogenizing and reductive terms used by 1970s feminist theory like “patriarchy” or “phallocentrism.” It is thus more pertinent to talk of masculinities in the plural form, not only to show how it is shaped by competing or mutually reinforcing identities, but also to account for the dominant position of hegemonic models of masculinity over subaltern, marginalized identities. It thus refines, rather than invalidates, the feminist premise of “masculine domination.”

Masculinity is a homosocial enactment . Besides being constructed in opposition to femininity, masculinity is also to a large extent the result of male bonding, of socialization between men. If one is not born a man, but rather becomes a man, historians of masculinity have tried to analyze the various social processes by which this becoming is achieved, as well as the myths and rituals that regulate it. They have identified how, especially in exclusively male spaces like fraternities, boy gangs, sports teams and gentlemen’s clubs, male-to-male relationships structure masculine identity by encouraging certain behaviors and excluding others. In particular, the suspicion of homosexuality that hovers over those homosocial ties requires homophobia in order to safeguard an otherwise threatened heterosexual identity.

Masculinity is a performance . In keeping with Judith Butler’s influential proposition that “gender is always a doing” (33) rather than a fixed identity and that it is performatively constituted through “a repeated stylization of the body” (44), theories of masculinity have posited that any attempt at grounding masculine identity in biological sex, in Oedipal anxiety or in trans-historical archetypes amounts to a conceptual fallacy. Masculinity has little to do with the male body and is essentially prosthetic, so much so that it can be said to be “all the more legible when it leaves the white male body” (Halberstam 2) as is the case with “female masculinity”—that is, biological women assuming masculine gender.

6 Before we see how those various paradigms can help redraw the contours of literary analysis, a few comments should be made as to the disciplinary status of masculinity studies. Though it has surely participated in the fragmentation of disciplines and the hyperspecialization of academia, masculinity studies cannot really be said to be an autonomous field or to have explored a no-man’s-land. Not only has it heavily borrowed from both queer theory and gender studies, but it has always had an uneasy relationship to both feminism (as the awkwardness of the term “pro-feminist” suggests) and to the mythopoetic men’s movement (to which it was meant to be a critical reaction). It does not have a methodology of its own, but has relied on the epistemological tools taken from sociology, psychology, historiography, philosophy and various other disciplines. Besides, masculinity studies has experienced many developments since its inception—like boyhood studies or black masculinity studies—further deterritorializing a disciplinary field that has no separate, independent existence.

2. Genre, gender and the fictions of masculinity

- 4 This recurrent discourse is symptomatic of the cyclic fear that masculinity is in danger of decli (...)

7 When social historian Arthur Schlesinger published “The Crisis of American Masculinity” in the November 1958 issue of Esquire , the idea that men in the United States were going through an identity malaise and that society was becoming more and more feminized was far from new and already had a long history. 4 What is far more interesting is how Schlesinger, though not a literary critic, resorts to literature in his analysis of masculinity and retraces a short genealogy of the virility of the male hero in the American novel—from certainty about what masculinity meant until the Civil War, to the first cracks and doubts in male protagonists at the beginning of the 20 th century and the then-contemporary confusion about what made a man:

For a long time, [the American male] seemed utterly confident in his manhood, sure of his masculine role in society, easy and definite in his sense of sexual identity. The frontiersmen of James Fenimore Cooper, for example, never had any concern about masculinity; they were men, and it did not occur to them to think twice about it. Even well into the 20 th century, the heroes of Dreiser, of Fitzgerald, of Hemingway remain men. But one begins to detect a new theme emerging in some of these authors, especially in Hemingway: the theme of the male hero increasingly preoccupied with proving his virility to himself. And by mid-century, the male role had plainly lost its rugged clarity of outline. (Schlesinger 292)

- 5 First, his choice of Cooper’s Natty Bumppo as a starting point is rather problematic, the protago (...)

8 Though Schlesinger’s wide-ranging meta-narrative approach to the relationship between masculinity and literature in the United States lacks contextual specificity and conceptual accuracy, his intuition that fiction betrays or reformulates the tension between the experience and the ideal of masculinity is highly useful. 5 What is enabling in this way of understanding the history of literary forms is that it goes beyond simple structural or formal typologies and allows to account for the social norms and gender codes which affect aesthetic categories and determine poetic choices. Yet, genre and gender are bound together in intricate ways that require a refined work of contextualization. Narrative strategies, stylistic choices, rhetorical effects and diegetic realms reflect generic concerns that are often built on specific assumptions about what a man should be. By bringing attention to masculine identities in its multiple forms, masculinity studies has enabled to draw out an archeology of literary masculinity that goes beyond the relation of binary opposition to a purportedly unified feminine tradition and can account for the ways in which definitions of literary genres are fraught with gender implications.

9 In that perspective, several studies have focused on specific genres such as the crime novel, a genre which includes the roman noir , the hard-boiled novel and the detective novel, and encompasses the “highbrow” novels written by Chester Himes, Raymond Chandler, James M. Cain and Dashiell Hammett and the more popular fiction found in dime novels. In the context of anti-homosexual panic, virulent anti-intellectualism and anti-feminist discourses, the protagonist of crime novels — “ the white man wandering the urban streets, threatened and alone”—o ffers a figure “whose compulsive representation can help to examine the troubled and troubling consolidation of white masculinity in pre-and post-World War II American culture” (Abbott 5). Chandler’s defining essay on the genre does not leave any doubt as to the gender or sexual identity of characters like the Continental Op: “He must be a complete man and a common man, yet an unusual man,” “a man of honor” who “is neither a eunuch nor a satyr” and who “will take no man’s dishonesty, and no man’s insolence without due and dispassionate revenge,” “a lonely man” whose “pride is that you will treat him as a proud man or be very sorry you ever saw him” (qtd. in Kimmel, 2006 141). Confronted with stock characters like the femme fatale or the “homosexual pervert” and defined in opposition to the emasculating conformity of the “man in the grey-flannel suit,” this independent, violent and affectless character is resolutely straight and excessively masculine, as well as systematically white. Popular sub-genres like sports fiction, travel narratives and war accounts, which were the stuff of men’s adventure magazines during the heyday of pulp publishing, offer similar narrative codes, stock characters, textual motifs and narrative strategies that reflect the sexual anxiety of their exclusively male readership and of society at large. They all draw a rather strict line between winners and losers, rugged individualists and domesticated family men, real men and wimps, hard-boiled and soft men, straight and queer, brave men and sissies. As such, they produce and reproduce representations about what men are, can be or ought to be.

10 Another revealing example of the unlikely connections between literary genre and masculine gender is the opposition that structured novel writing in the late 19 th century in the United States with, on the one hand, the cult of virility among self-declared realist writers like Frank Norris, Jack London, Mark Twain and William Dean Howells, and, on the other hand, the local-color regionalism of female writers like Sarah Orne Jewett, Rose Terry Cooke, Mary E. Wilkins Freeman or Constance Fenimore Woolson and its supposedly feminine sentimentality, abstraction and idealism. As Nathaniel Hawthorne’s famous description of late 19 th -century female novelists as a “damned mob of scribbling women” (304) reminds us, male novelists then feared that women were colonizing the field of novel writing, a loss of privilege that also meant a threatening feminization of their status and identity as practitioners of literature. “Fiction is not an affair of women and aesthetes,” Norris writes, before adding that “[o]f all the arts it is the most virile” (1155). Not only was novel writing a man’s game in which women had no part, but his conception of the female muse was far removed from any hint of femininity: she was not a “chaste, delicate, super-refined mademoiselle of delicate roses and ‘elegant’ attitudinizing, but a robust, red-armed bonne femme who rough-shoulders her way among men” (1155), a butch, masculine woman who significantly differs from the femme fatale of English Romantic poetry (like John Keats’s Belle Dame sans Merci ). As Michael David Bell puts it in his influential study of American realism, “[t]o claim to be a ‘realist,’ in late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century America, was among other things to suppress worries about one’s sexuality and sexual status and to proclaim oneself a man” (37).

11 Like fiction, poetry has also been troubled by gender controversy. Postwar literary communities in the United States are a case in point. Whereas European bohemia of the early 20 th century offered women important venues for artistic creation and collaboration, American poetic circles in the 1950s did not provide much recognition or support to women writers who had to define themselves largely within male circles. Allen Ginsberg remarked that “[t]he social organization which is most true of itself to the artist is the boy gang, not society’s perfum’d marriage” (80), opposing the joyful carelessness and freedom of schoolboys and bachelors to the institution of marriage which can only stifle the poet’s creativity. Similarly, Robert Duncan referred to the San Francisco Renaissance as “the champions of the boys’ team in Poetry,” a team that was divided between “star players, bench sitters and water boys”, while the only women allowed were Helen Adam as a maternal poetic figure of sorts—“team godmother”—and Joanne Kyger—“[she] could play on the team, but she was a girl” (qtd. in Davidson, 1989 175). Literary communities have indeed been mostly conceived on the model of gentlemen’s clubs, most often excluding, or at least belittling, women’s literary ambitions. They could be muses, lovers, prostitutes, mother figures, monsters of virtue or of bitchery, but rarely authors in their own right.

12 Besides, competing definitions of masculinity were often at stake in poetic debates. For instance, the distinction made by Robert Lowell between two schools of poetry in his 1960 National Book Award acceptance speech is symptomatic of the conflicting tension between two radically diverging perceptions of male authorial identity: on the one hand, the “raw” poetry of Black Mountain, Beat Generation, San Francisco Renaissance and New York School poets—“blood dripping gobbets of unseasoned experience […] dished up for midnight listeners,” “a poetry that can only be declaimed,” “a poetry of scandal” (qtd. in Staples 13)—and the “cooked” poetry of the New Formalists like Richard Wilbur, James Merrill, Anthony Hecht and Elizabeth Bishop—“marvelously expert,” “laboriously concocted to be tasted and digested by a graduate seminar,” “a poetry that can only be studied,” “a poetry of pedantry” (13). The latter is more aristocratic and elitist, civilized and domesticated, influenced by European modernism and denounced as effete intellectualism by its opponents and as downright “castration of the pure masculine urge to freely sing” by Jack Kerouac (1993 56); the former is crude and rugged, spontaneous and primitive, and purports to convey an all-American feeling of energy, freedom and virility. The homosocial nature of literary communities, the correlative marginalization of women and the uncritical celebration of masculine qualities thus provide an interesting background for reading certain literary texts through which writers of both sexes defended their respective poetics and transformed the field of literature. Instead of a grand narrative based on the loss or conquest of the Phallus, one has to follow the local relations of intertextuality and the way writers have revised gender representations. Diane di Prima’s “The Practice of Magical Evocation,” a sardonic response to Gary Snyder’s somewhat misogynist poem “Praise for Sick Women,” or Denise Levertov’s “Hypocrite Women,” an equally scathing poem that constitutes a poetic reply to Jack Spicer’s celebration of male beauty and love in “For Joe,” are two cases in point in that regard (Davidson 1989).

3. Writing masculinity: from the pen(is) to the mask

- 6 In their following work, No Man’s Land , the two feminist critics actually presented the literary (...)

13 In their groundbreaking work on 19 th -century female novelists, The Madwoman in the Attic , Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar begin their analysis by insisting that “[t]he poet’s pen is in some sense (even more figuratively) a penis” (Gilbert and Gubar, 1984 4). In their eyes, this means that women who wanted to write had to seize the pen from male authors, adopt the phallic power it confers, before adapting it to their own purposes. 6 Yet, as Michael Davidson remarked in his influential study of masculinity in American postwar poetry, such a proposition raises a certain number of questions and its theoretical flaws have to be deconstructed in the light of gender and queer theory:

Is the penis a penis, and can it stand up, as it were, to the work of masculinity in its multiple forms? Is the possession of biological signs of masculinity the same as being masculine? At what point does the penis become the phallus, a free-floating signifier of authority capable of being possessed by both biological males and females? (Davidson 159)

14 This series of questions opens up multiple perspectives of inquiry that do not equate sex, gender and sexuality and can renew our approach to the relationship between masculinity and writing. By drawing out a history of the masculine gender, masculinity studies does not only allow to contextualize the representation of male characters, but also allows to account for the way in which certain stylistic characteristics are perceived, at a certain place and time, in a gendered perspective. The act of writing is not an idiosyncratic expression or a trans-historical artifact that takes place in the intimate space of the author’s study room and reflects his inner self or his hidden psyche, but a performative act that takes place on a socio-political stage and constitutes the identity that is said to pre-exist. Masculinity is not a question of sex, of a biological body, of a nature or of an identity that would predate writing or that writing would express or complete. It is performative in the sense that it is articulated, achieved and conveyed through the act of writing itself. There is no “masculine writing” and the pen is not a penis; there are textual effects of gender that result from the stylized reiteration of, and in, writing.

- 7 The article about Willa Cather published in the July 1927 issue of Vanity Fair is entitled “An Am (...)

15 Several interconnected consequences follow. First, gendered metaphors of style should be deconstructed and seen as what they are—namely, tropes which are given materiality through stylistic devices. Let’s take the example of “muscular prose,” best embodied by Ernest Hemingway’s lean, sparse, unadorned style. It is characterized by the use of few adjectives and tropes, short sentences, simple syntactical structures, asyndetic parataxis and minimal dramatization. What is “masculine” or “muscular” about it remains unclear, though it certainly has to do with the emotional detachment and the sense of restraint that it supposedly conveys. Yet, by virtue of its being associated with Hemingway’s heroic masculinity and literary persona, it has represented a model for many writers (one can think of James Baldwin’s praise of Norman Mailer’s The Naked and the Dead [1948] and Philip Roth’s admiration for Saul Bellow’s Augie March [1953], both explicitly mentioning their “muscular prose”). Yet, when applied to Willa Cather’s novels by a magazine writer in Vanity Fair in 1927, it has to be read as a way of legitimizing a female writer for writing “like a man” and entering the “man’s game” of novel writing, incidentally reaffirming a long tradition that associates aesthetic profusion (as well as sentimentality and regionalism) with femininity. 7 However, terms such as “muscular” are subjective, connoted and potentially reversible. For 1950s poets like Michael McClure, who claimed that his writing obeyed the “muscular principle” which “comes from the body—it is the action of the senses—[…] it is the voice’s athletic action on the page and in the world” (vii), muscularity came to be associated with the very opposite qualities, namely dramatization of enunciation, lyricism, polysyndeton, accumulation of adjectives, multiplicity of tropes and an expressionist aesthetic.

16 The second consequence is that the connection between writing and masculinity is historically contingent and pragmatically constituted. Writing does not take place ex nihilo , but is intricately woven with a network of social, cultural and aesthetic norms which precede and exceed the writing subject. Authorial identity does not emerge on the corner of a blank page, but on the public stage of literature. The author is well aware that his identity is going to be perceived through the reader’s eye and inferred from the stylistic characteristics of his prose. In the context of post-World War II anti-homosexual paranoia in the United States for instance, a period that witnessed the emergence of endless talk about a perceived “crisis of masculinity,” the suspicion of effeminacy loomed large over the literary scene. Considering the close ties that bind one’s writing to one’s literary persona, building a resolutely masculine identity meant writing in a way that denoted manly skills. Especially in first-person narratives and poetry, stylistic vir tuosity became a way of conveying vir ility. Writing about what one had experienced was a guarantee of authentic authorship, a badge of honor, as if “real men” wrote about “real life” in “real prose.” Writing, in that context, had to convey the sense of danger and implied taking risks, and this is how we should read the popularity of a certain brand of realism in the postwar era. Hemingway’s fascination for bullfighting and his vision of the bullfighter as the epitomic model for the writer—because “bullfighting is the only art in which the artist is in danger of death and in which the degree of brilliance in the performance is left to the fighter’s honor” (Hemingway, 2000 80)—participates in his attempt to build a virile literary persona. Likewise, Kerouac’s comparing himself to an athlete or his writing to running a sprint, a football game or boxing match, is revealing in a context in which Americans were thought to be too “soft” by President John F. Kennedy himself. For Kerouac, writing had to convey the sense of speed and movement that stirred the writer at the typewriter, as well as the sweat, tears and blood that it had cost him to write On the Road in three weeks and The Subterraneans in three days. In his eyes, this physical feat made him a literary hero of masculinity and attested to his belonging to the hard-boiled tradition of American novelists.

17 Thirdly, considering that the pen is not a penis, figuratively or otherwise, results in recognizing that masculinity is not the exclusive preserve of males. The performance of masculinity has to be read as a series of prosthetic effects, of cultural markers without which masculinity becomes undecipherable. In Female Masculinity , Jack Halberstam brilliantly demonstrates how masculinity should not be reduced to biological men and was all the more legible when it was not attached to the white male body. The “inverts” who people the narrative of modernist women writers like Virginia Woolf or John Radclyffe Hall are examples of women who lived “their lives as, if not men, wholly masculine beings, […] did effectively change sex inasmuch as they passed as men, took wives as men, and lived as men,” and “satisfied their desire for masculine identification through various degrees of cross-dressing and various degrees of overt masculine presentation” (Halberstam 87). In The Well of Loneliness (1928), Stephen—a young woman named with a boy’s name, who dresses like a man and falls in love with a woman named Angela—and the eponymous protagonist in Orlando (1928)—a young nobleman who wakes up a woman and dresses alternatively as both man and woman—are well-known instances of literary performances of gender which raise essential questions as to the nature of masculinity.

18 Finally, performative approaches to masculinity in literature are helpful in so far as they enable to identify narrative masquerades and the staging of the writing self—the props, the masks and the postures that convey the sense of a properly masculine performance. One revealing example in that regard is the gendered use made by white male authors of African-American vernacular English, cultural codes and myths. This tendency to borrow elements from black culture for purposes that vary from comic parody—as in blackface minstrelsy—to serious pastiche—in jazz-influenced poetry for example—has been a constant feature of American culture. Passing for black was often a way to make up for what was perceived as the lack of vigor and potency of white middle-class culture. Many writers saw black culture as the expression of a primitivist ethos that denoted a libidinal energy and a virile strength in which they could drape themselves in order to stand out from the conformity of their social class and liberate themselves from their cultural milieu, often indulging in downright racial stereotyping. Norman Mailer’s notorious essay “The White Negro” (1957), in which the American novelist celebrates a new breed of white men who have “absorbed the existentialist synapses of the Negro” and go out at night “with a black man’s code to fit their facts” is a revealing literary example of white-to-black passing and the racial clichés that inevitably arise in such a performance: “ in the worst of perversion, promiscuity, pimpery, drug addiction, rape, razor-slash, bottle-break, what-have-you, the Negro discovered and elaborated a morality of the bottom” (341, 348). Beat Generation writers’ endorsement of bebop jazz as developed by Charlie Parker, Thelonious Monk and Dizzie Gillespie must be read in this way. Although these writers’ desire to put on a black mask most certainly participates in an attempt to transgress the codes of a segregated society and to betray one’s cultural heritage, this cultural re-appropriation also expresses a desire to gain visibility and adopt the supposed virility of African-Americans at the cost of racist stereotypes. When the narrator of On the Road walks the streets of a black neighborhood in Denver, “ wishing [he] were a Negro, feeling that the best the white world had offered was not enough ecstasy […], wishing [he] could exchange worlds with the happy, true-hearted, ecstatic Negroes of America” (Kerouac, 1998 169-170), he unwillingly expresses how the revitalizing of white middle-class masculinity through racial passing only idealizes the living conditions and overlooks the political situation of African-Americans.

4. Beyond Oedipus: desire and masculinity in narrative

19 Before the emergence of masculinity studies, masculine identity was often understood through the prism of psychoanalysis. Analyses focused on the Phallus as the master signifier of masculinity and the Oedipus myth as its main structuring narrative. From Vladimir Propp (1968) to Jurij Lotman (1979) , Marthe Robert (1980) and Roland Barthes (1977) , the Oedipus complex has played a central role in early analyses of masculinity in narratives. In Alice Doesn’t: Feminism, Semiotics, Cinema (1984) , queer theorist Teresa de Lauretis herself conceives of desire in narrative structure as essentially male since its object is woman, an active/passive configuration of gender roles which, according to her, raises problems of identification for female readers. Like a specter, Oedipus is summoned again and again by literary theorists and functions like the return of the repressed—the Law, Authority, the Other, the Name of the Father, castration. Consequently, in this theoretical context, writing, like desire, is always viewed as patricidal (or incestuous), a transgression of the Law, a rebellion against tradition; and as Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari argued in Anti-Oedipus (1972), projecting the familial neurotic triangular logics of “Daddy-Mommy-Me” onto social functions, cultural logics or legal fictions does not essentially affect the psychoanalytical perception of the male subject who remains caught in the same dialectics—father and son, law and transgression, jouissance and symptom.

- 8 The Oedipus complex has indeed played a central role in psychoanalytical accounts of homosexualit (...)

20 The point here is not simply to rehearse an age-old argument against psychoanalysis per se , though it has undeniably tended to reduce gender identity to sexual difference, a binary distribution which stems from the double bind of incest and patricide in the Oedipal triangle. The main concern is that psychoanalytically-influenced literary critiques often tended to lay male novelists, poets and playwrights on the analyst’s sofa, presenting their texts as personal confessions or family narratives in which they could detect the symptomatic expressions of repressed primal scenes and unconscious desires. Particularly in the cases of autobiographies and of first-person narratives, the net result of such an approach was to transform authors into little boys expressing the regressive desire to return to the maternal realm and condemned to repeat immature acts of transgression against paternal authority or great precursors. As Alice Ferrebe noted in her thorough analysis of masculinity in late 20 th -century British literature, “[i]dentification with this constantly alienated and superior attitude—reading male-authored texts as listening to little boys bolstering their egos—is […] problematic for a contemporary reader” (5). This tendency to infantilize authors and readers not only prevents literary critics from taking certain literary works seriously, but more importantly, it treats non-normative expressions of masculinity as boyish (for they fail to accept the castration inherent to adult masculinity) and thus tacitly reproduces heteronormative accounts of gender. 8 For instance, though Leslie Fiedler’s Love and Death in the American Novel (1960) could be considered as one of the first full-length literary study of masculinity, in particular for its groundbreaking analysis of male bonding in Mark Twain’s Tom Sawyer (1876) and Huckleberry Finn (1884), it fails insofar as it relies on uncritical definitions of masculinity and homosexuality inherited from Jungian archetypes. This leads Fiedler to frame American literature within the confines of regression and immaturity, regarding it as children’s literature that avoids the representation of sexuality.

21 Masculinity studies, following the findings of queer theory in that regard, has revised this perception and shown the theoretical deficiencies on which it is founded. In her crucial study of male homosocial desire in British literature, Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick based her analysis on René Girard’s mimetic (rather than Oedipal) approach to desire to show that, “in any male-dominated society, there is a special relationship between male homosocial ( including homosexual) desire and the structures for maintaining and transmitting patriarchal power” (Sedgwick, 1985 26). She goes on to explain how this structural congruence can take the form of “ideological homophobia, ideological homosexuality, or some highly conflicted but intensively structured combination of the two” (26). What emerges from her work is the double-bind of masculine identity—the way male writers and characters have had to navigate between prescribed forms of homosocial bonding and proscribed forms of homosexual desire: “For a man to be a man’s man is separated only by an invisible, carefully blurred, always-already-crossed line from being ‘interested in men’” (89). In this perspective, several plays in the vein initiated by William Wycherley’s The Country Wife (1675), in which male characters’ measures of success are either a marriage in which one is not cuckolded, or how many husbands one has cuckolded, come out as works about male subjects’ struggle for mastery against other men, rather than for female objects of desire. Besides, if same-sex desire has historically been the love that dares not speak its name, one shall maybe lend a careful ear to oblique, indirect expressions of same-sex desire. William Shakespeare’s Sonnet XVII (1609), Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass (1855) and Tennessee Williams’ Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (1955) are well-known instances that call for other works to be read in that perspective.

22 What follows from this is a renewed understanding of the textual function of homophobia which, like homosexuality, has often been the object of an Oedipal reading that has obscured its working in fiction. In what has become one of the most influential articles written about masculinity, “Masculinity as Homophobia: Fear, Shame, and Silence in the Construction of Gender Identity,” Michael Kimmel explains how homophobia is not so much the fear of homosexual men as the etymology of the word seems to suggest, but “the fear of being perceived as gay,” a feeling that leads men to exaggerate all the traditional codes of masculinity (from sexual predation to physical violence or emotional containment) for fear of being perceived (and shamed and marginalized) as “soft” men, “sissies,” or “faggots”: “[m]asculinity has become a relentless test by which we prove to other men, to women, and ultimately to ourselves, that we have successfully mastered the part” (Kimmel, 2005 41). Interpreting signs of homophobia as symptoms of an author’s repressed same-sex desire and transforming him into a closeted or repressed homosexual opens speculations that do not carry very far and only reveals open secrets that one already knew about all along, most often by resorting to biographical data that supposedly support the uncovering of an Oedipal logic.

23 In contrast with those paranoid readings, homophobia as Kimmel defines it allows to account for its narrative function—regulating the spectrum of male-to-male relationships by reinforcing fraternal feelings of virile comradeship while condemning homoerotic feelings, particularly in historical contexts which saw the rise of discourses about the so-called “crisis of masculinity.” Homophobia serves the function of purging male friendship, bachelorhood and attachment to mother figures of any suspicion of homosexuality: Kerouac’s On the Road (1957), Roth’s Portnoy’s Complaint (1969) and Mailer’s An American Dream (1965) are well-known examples of narratives which present protagonists whose uneasy relationship to women (ranging from pornography, prostitution to excessive maternal attachment, chastity or wife-killing) and homosocial environment require explicit homophobia to save them from being identified as homosexuals. Jake Barnes, the protagonist of The Sun Also Rises (1926), who, like many of Hemingway’s characters, lives in a world of “men without women” to borrow the title of one of the author’s collections of short stories, can only confess his failure to embody heroic masculinity—“it is awfully easy to be hard-boiled about everything in the daytime, but at night it is another thing” (Hemingway, 2006 42)—by asserting at the same time a homophobic vision of the world: “Somehow they [gay men] always made me angry. I know they are supposed to be amusing, and you should be tolerant, but I wanted to swing on one, any one, anything to shatter that superior, simpering composure” (28). Besides, in the case of autobiographical narratives, one should pay attention to the way the author’s anxiety about being perceived as homosexual often contaminates the narrative. Kerouac’s well-known fear of being identified as gay—“Posterity will laugh at me if it thinks I was queer […] I am not a fool! A queer! I am not! He-he! Understand?” (Kerouac, 1995 167)—has to be read in parallel with his deleting from the published version of the novel the scene in which the narrator watches the hero of On the Road prostituting himself with a gay man, a scene that appears unedited in the original scroll published in 2007. Yet, rather than serving an account of Kerouac’s homophobia which would present him as a closeted homosexual pathologically attached to his mother, this act of self-censorship ought to be seen in the historical context of the persecution of homosexuals in the 1950s (which historian David K. Johnston terms the “lavender scare”) and the anti-homosexual paranoia that haunted poets, novelists and playwrights in the early 1950s ( see Johnson 2004) .

Conclusion: Is there a theory in this class?

24 De-compartmentalizing academic fields is not only desirable to improve and refine one’s respective disciplinary practices—in France, Anglophone studies are typically divided between “linguistique,” “civilisation,” “littérature” and “traductologie,”. Within the field of literary studies in France, for instance, it has become a vital necessity to make a stronger case in favor of grounding the analysis of style, narrative and genre in questions of race, class, gender and cultural identity. In particular, the current development and partial success of gender studies in the different established disciplines tends to both disrupt epistemological frontiers and lead to unlikely and often fruitful connections and tensions. Since the sphere of literature is not separate from the world outside literature (if such a distinction can actually be made), it is urgent that French academics such as myself consider our interpretive practices and their cultural assumptions, in particular the supposed scientific objectivity of structuralist approaches and the universalist ideals inherent to France’s particular brand of republicanism (see Scott 2005) .

25 Literary studies used to play a central role in intellectual and scientific debates in France. The fact that language was its raw material and that writing was its organizing principle seemed to naturally grant it a privileged position in the comprehension of human life. It attracted students and researchers from other disciplines who looked at literary analysis as a model for reformulating disciplinary practices and methods. Later, those thinkers whom American colleagues call post-structuralists and often group together under the label “French Theory” could not devise a philosophical system that did not make room for literature. In this context, to say that literary studies has lost its power of attraction is an understatement. Though critical theory has been legitimately criticized for the way in which it has occasionally supplanted the analysis of literary texts and led to normative readings—one thinks of Stanley Fish’s critique Is There a Text in this Class? (1980)—, it has also instilled a lively atmosphere of emulation and creativity which François Cusset aptly described in French Theory (2003).

26 The point, though, is not to lament over the glory days of literary theory in France, nor to apologize for its supposed excesses on the other side of the Atlantic, but to find new ways of reading that can help us account for the world in which we live. For a long time, literature has been read as if it were essentially concerned with itself. Form was the main concern and object of literary analysis, reinforcing in the process the autonomous and differential status of the field. Since literary studies needed to be legitimated as a scientific enterprise, it drew precise boundaries and set up specific methodologies that have then limited its scope and influence. If we have all learnt to read as “straight white males,” then maybe reading otherwise means rethinking the epistemological and hermeneutic tools we have been using. However useful and precise, these tools make us blind to larger and more crucial questions, especially in the classroom. Saying that form is content or that the world itself is a matter of formal organization is not enough. Metaphors, narratives, characters, styles and genres tell us about individual and collective identity at least as much as they tell us about literature and aesthetics. Ecopoetics and ecocriticism, care and disability studies, queer theory and gender studies are just a few examples of lines of inquiry which have already played a central role in reconnecting everyday life with the world of literature. Thanks to their close ties with English-speaking academia, English language departments in France are arguably well positioned to bridge this gap and revive the sense that literature is crucial to us all.

Bibliography

Abbott, Megan E. The Street Was Mine: White Masculinity and Urban Space in Hardboiled Fiction and Film Noir . New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2002.

Baldwin, James. Nobody Knows my Name . New York: Vintage, [1961] 1993.

Barthes, Roland. “Introduction to the Structural Analysis of Narratives.” Image-Music-Text . New York: Hill and Wang, [1966] 1977.

Bederman, Gail. Manliness and Civilization: A Cultural History of Gender and Race in the United States, 1880-1917 . Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1995.

Bell, Michael Davitt. The Problem of American Realism. Studies in the Cultural History of a Literary Idea . Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1996.

Butler, Judith. Gender Trouble . 1990. New York: Routledge, 1999.

Caroll, Brett E. American Masculinities: A Historical Encyclopedia . New York: Sage, 2003.

Cusset, François. French Theory. Foucault, Derrida, Deleuze & Cie et les mutations de la vie intellectuelle aux Etats-Unis . Paris: La Découverte, 2005.

Davidson, Michael. The San Francisco Renaissance: Poetics and Community at Mid-Century . Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1989.

Davidson, Michael. Guys Like Us: Citing Masculinity in Cold War Poetics . Chicago: U of Chicago P, 2004.

Deleuze, Gilles, Félix Guattari. L’Anti-Œdipe . Paris: Minuit, 1972.

Fergusson, Gary, ed. L’Homme en tous genres. Masculinités, textes et contextes . Paris: L’Harmattan, 2009.

Ferrebe, Alice. Masculinity in Male-Authored Fiction, 1950-2000: Keeping It Up. Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2005.

Fiedler, Leslie. Love and Death in the American Novel . London: Paladin, [1960] 1970.

Fish, Stanley. Is There A Text In This Class? The Authority of Interpretive Communities . Cambridge: Harvard UP, 1980.

Flood, Michael, Judith Keegan Guattari , Bob Pease, Keith Pringle, eds. International Encyclopedia of Men and Masculinities . Abingdon: Routledge, 2007.

Ginsberg, Allen. Journals: Early Fifties, Early Sixties . New York: Grove Press, 1977.

Gubar, Susan, Sandra M. Gilbert. The Madwoman in the Attic: The Woman Writer and the Nineteenth-Century Literary Imagination . New Haven: Yale UP, 1984.

Gubar, Susan, Sandra M. Gilbert. No Man’s Land: The Place of the Woman Writer in the Twentieth Century . New Haven: Yale UP, 1991.

Halberstam, Judith. Female Masculinity . Durham: Duke UP, 1998.

Hall, Geoff. Literature in Language Education . Basingstroke: Palgrave MacMillan, 2005.

Hawthorne, Nathaniel. The Centenary Edition of the Works of Nathaniel Hawthorne. Vol. 16. Columbus: Ohio State UP, 1987.

Hemingway, Ernest. The Sun Also Rises . New York: Scribner, [1926] 2006.

Hemingway, Ernest. Death in the Afternoon . London: Vintage, [1932] 2000.

Hocquenghem, Guy. Le Désir homosexuel . Paris: Fayard, [1972] 2000.

Johnson, David K. The Lavender Scare: The Cold War Persecution of Gays and Lesbians in the State Department . Chicago: U of Chicago P, 2004.

Kerouac, Jack. On the Road . New York: Penguin, [1957] 1998.

Kerouac, Jack. Good Blonde and Others . San Francisco: City Lights, 1993.

Kerouac, Jack. Selected Letters I . New York: Penguin, 1995.

Kimmel, Michael. Manhood in America: A Cultural History . New York: Oxford UP, 2006.

Kimmel, Michael. “Masculinity as Homophobia.” 1994. The Gender of Desire: Essays on Male Sexuality . Albany: State University of New York Press, 2005. 25-42.

Kimmel, Michael, Amy Aronson, eds. Men and Masculinities: A Social, Cultural, and Historical Encyclopedia . Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, 2004.

Lauretis, Teresa de. Alice Doesn’t: Feminism, Semiotics, Cinema . Bloomington: Indiana UP, 1984.

Lawrence, D. H. Studies in Classic American Literature . Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2003.

Lotman, Jurij. “The Origin of Plot in the Light of Typology.” 1973. Poetics Today 1 (Autumn 1979): 161-184. DOI: 10.2307/1772046

Mailer, Norman. “The White Negro.” 1957. In The Portable Beat Reader . Ed. Ann Charters. New York: Penguin, 1992. 581-605.

Mcclure, Michael. Rebel Lions . New York: New Directions, 1991.

Messner, Michael A. Politics of Masculinity: Men in Movements . Thousand Oaks: Sage, 1997.

Norris, Frank. “Novelists of the Future.” 1901. Ed. Donald Pizer, Novels and Essays . New York: Library of America, 1986. 1152-1156.

Propp, Vladimir. Morphology of the Folktale . Austin: U of Texas P, [1928] 1968.

Robert, Marthe. Origins of the Novel . Brighton: Harvester Press, [1972] 1980.

Roth, Philip. “Writing American Fiction.” In The Novel Today: Contemporary Writers on Modern Fiction . Ed. Malcolm Bradbury. Manchester: Manchester UP, 1977. 32-47.

Rotundo, E. Anthony. American Manhood: Transformations in Masculinity from the Revolution to the Modern Era . New York: BasicBooks, 1993.

Schlesinger, Arthur. “The Crisis of American Masculinity.” 1958. In The Politics of Hope and The Bitter Heritage . Princeton: Princeton UP, 2008. 292-303.

Scott, Joan W. Parité: Sexual Equality and the Crisis of French Universalism . Chicago: U of Chicago P, 2005.

Sedgwick, Eve Kosofsky. Between Men: English Literature and Male Homosocial Desire . New York: Columbia UP, 1985.

Staples, Hugh B. Robert Lowell: The First Twenty Years . New York: Farrar, Strauss & Cudahy, 1962.

“An American Pioneer—Willa Cather,” Vanity Fair , July 1927: 30. https://archive.vanityfair.com/article/19270701039

1 The mid-1990s saw the almost simultaneous publication of Manliness and Civilization (1996) by Gail Bederman, Masculinities (1995) by R. W. Connell, Michael Kimmel’s Manhood in America (1996), Anthony E. Rotundo’s American Manhood (1993) and Michael Messner’s Politics of Masculinities (1997).

2 Among the encyclopedias, see for instance Flood (2007), Carroll (2003), and Kimmel and Aronson (2004). Academic journals include the Journal of Men’s Studies (since 1992), the Journal of Men and Masculinities (since 1998) and Norma: International Journal for Masculinity Studies (since 2006). The American Men’s Studies Association and the Nordic Association for Research on Men and Masculinities are two examples of active scholarly societies. As for book series, the Sage Series on ‘Men and Masculinities’ and Palgrave’s Series on ‘Global Masculinities’ have played a decisive role in publishing research in this area.

3 See for instance Fergusson (2009). It should also be noted that an international conference entitled “Performing the Invisible: Masculinities in the English-Speaking World” was organized at the Université Sorbonne Nouvelle-Paris 3 on September 25-26, 2010, following a two-year research project on masculinity which brought together young researchers from various disciplinary backgrounds, including literary studies.

4 This recurrent discourse is symptomatic of the cyclic fear that masculinity is in danger of decline. The fact that a distinguished intellectual like Schlesinger took up the question is yet another proof of the deep roots of this thesis in the minds of Americans and, in particular, among the American elite. According to Schlesinger, gender roles have been blurred, both at home and in public life. The American male has become feminized and domesticated, performing “female” duties like changing diapers or cooking meals, thus transforming himself into “a substitute for wife and mother” (Schlesinger 292). Women, by contrast, are described as the “new rulers,” as an “aggressive force” or a “conquering army” (293), a military simile which presents men as victims of emasculating women.

5 First, his choice of Cooper’s Natty Bumppo as a starting point is rather problematic, the protagonist of the Leatherstocking Tales (1823-1841) being what David Leverenz calls the first embodiment of the “Last Real Man in America,” which is far from being representative of the American colonists of the second half of the 18 th century. Also, putting in perspective Natty Bumppo and, say, Fitzgerald’s Jay Gatsby ( The Great Gatsby, 1925), or Hemingway’s Jake Barnes ( The Sun Also Rises, 1926), leads Schlesinger to draw a questionable picture of literary masculinity. Besides, one should not forget that novels like The Last of the Mohicans (1826) and their rugged, manly characters, merely reflect the fantasies of a Paris-based author who belonged to the Manhattan elite, an irony which was not lost on D. H. Lawrence who described Cooper as “a gentleman in the worst sense of the word” (52).

6 In their following work, No Man’s Land , the two feminist critics actually presented the literary field as a battleground where both “sexes” had fought a war for hegem ony, from Mid-Victorian writers “dramatiz[ing] a defeat of the female” to slowly “envision[ing] the possibility of women’s triumph,” a tendency which culminated in the modernist era, when “both sexes by and large agreed that women were winning,” before “postmodernist male and female writers, working in the 1940s and 1950s, reimagined masculine victory” (Gilbert and Gubar 1991: 5).

7 The article about Willa Cather published in the July 1927 issue of Vanity Fair is entitled “An American Pioneer—Willa Cather” (30). James Baldwin’s comment about Norman Mailer’s prose in The Naked and the Dead and Barbary Shore is from “The Black Boy Looks at the White Boy” (228), an essay published in Nobody Knows my Name . Philip Roth characterizes Saul Bellow’s Augie March as “nervous muscular prose” (Roth 1977: 43).

8 The Oedipus complex has indeed played a central role in psychoanalytical accounts of homosexuality, often depicting same-sex desire as an immature and regressive libidinal impulse, which Guy Hocquenghem aptly named the “oedipianization of the homosexual.” After originally presenting homosexuality as the expression of the constitutive bisexuality of men and women, then connecting it to narcissism later in his career, Sigmund Freud finally accounted for same-sex desire through the Oedipal logic, a theory that was widely disseminated by popular psychology: unable to give up the mother as a love object, to identify with the father-rival and to substitute another woman of his choice, the now homosexual male seeks other men as his love object. By reducing it to an arrest in the child’s sexual development, this etiology of homosexuality ineluctably leads to pathologizing same-sex desire as “abnormal.”

Electronic reference

Pierre-Antoine Pellerin , “ Reading, Writing and the “Straight White Male”: What Masculinity Studies Does to Literary Analysis ” , Angles [Online], 3 | 2016, Online since 01 November 2016 , connection on 10 July 2024 . URL : http://journals.openedition.org/angles/1663; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/angles.1663

About the author

Pierre-antoine pellerin.

Pierre-Antoine Pellerin is a lecturer in English studies at the Université Jean Moulin-Lyon 3, where he teaches American literature and translation. His PhD focused on the experience and representation of masculinity in Jack Kerouac’s autobiographical cycle. He has published several articles on Beat Generation authors, most recently “Masculinité, immaturité et devenir-enfant dans l’œuvre de Jack Kerouac” in Leaves 2 (2016). His other research interests include ecocriticism and animal studies (“Jack Kerouac’s Ecopoetics in The Dharma Bums and Desolation Angels : Domesticity, Wilderness and Masculine Fantasies of Animality”, Transatlantica 2 / 2011). Contact: pierre-antoine.pellerin [at] univ-lyon3.fr

The text only may be used under licence CC BY 4.0 . All other elements (illustrations, imported files) are “All rights reserved”, unless otherwise stated.

Full text issues

- 17 | 2024 Re-Viewing and Re-Imagining Scottish Waters in Word and Image

- 16 | 2023 Cities in Scotland: Cultural Heritage and National Identity

- 15 | 2022 Cities in the British Isles in the 19th-21st centuries

- 14 | 2022 Angles on Naya/New Pakistan

- 13 | 2021 The Torn Object

- 12 | 2021 COVID-19 and the Plague Year

- 11 | 2020 Are You Game?

- 10 | 2020 Creating the Enemy

- 9 | 2019 Reinventing the Sea

- 8 | 2019 Neoliberalism in the Anglophone World

- 7 | 2018 Digital Subjectivities

- 6 | 2018 Experimental Art

- 5 | 2017 The Cultures and Politics of Leisure

- 4 | 2017 Unstable States, Mutable Conditions

- 3 | 2016 Angles and limes

- 2 | 2016 New Approaches to the Body

- 1 | 2015 Brevity is the soul of wit

The Journal

- Editorial Policy

- Editorial Team

- Submission Guidelines

- Publication Ethics & Malpractice Statement

Call for papers

- Call for papers – open

Information

- Website credits

- Publishing policies

Newsletters

- OpenEdition Newsletter

In collaboration with

Electronic ISSN 2274-2042

Read detailed presentation

Site map – Contact us – Website credits – Syndication

Privacy Policy – About Cookies – Report a problem

OpenEdition member – Published with Lodel – Administration only

You will be redirected to OpenEdition Search

Studies of Masculinities: State of the Art and Latest Trends

- First Online: 26 March 2024

Cite this chapter

- Josep M. Armengol 2

56 Accesses

While offering a quick look at the state of the art of masculinity studies, this chapter emphasizes some new directions within the field, particularly the repercussions of poststructuralist thinking on the latest research on gender. While studies of masculinities concentrate on the analysis of men and male identities, poststructuralism has recently challenged rigid concepts of identity, including gender identity. By questioning a number of binary oppositions, such as man/woman or masculine/feminine, this line of deconstructive thought, supported mostly by queer studies within gender studies, has demonstrated that gender identity is very far from being stable and fixed.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or Ebook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

The University of California at Berkeley led the way by incorporating this field of study into its curriculum in 1976 (Kidder, 2002 , 1).

Personally, I agree with Harry Brod’s idea that it is neither necessary nor convenient. As he explains himself, studies of masculinities «do not demand that attention to men is greater, but qualitatively different […] they are a complement, not a cooptation, of women’s studies. For these reasons, it seems best to eschew the conceptualization at the field as gender studies» ( 1987 , 60).

That is the case, for example, of the former women’s studies departments and programs at Indiana University (Bloomington); at Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey; and at UCLA (University of California at Los Angeles). While Indiana University created a new «Department of Gender Studies» (offering courses on masculinity studies, LGTBIQ + , and women’s studies), Rutgers and UCLA have simply added the term «gender» to their path-breaking women’s studies programs, thus creating departments of «Women’s and Gender Studies». Both options appear equally useful to underline the relevance of offering not only women’s studies but also gender studies.

Influenced by feminist texts, the first wave, which emerged mostly in the U.S., runs roughly from the mid-1970s to the 1980s. Among the key texts that resulted from this period,oneshouldmakereference to books such as Warren Farrell’s The Liberated Man ( 1974 ). Although these texts were clearly inspired by feminism, they mainly focused on denouncing the negative effect of traditional gender roles on men, rather than on the question of men’s privilege and their oppressive power over women (Armengol et al., 2017 ; Kidder, 2002 , 1–4; Kimmel and Messner, 1998 , xiii–xv). As Kimmel and Messner ( 1998 , xiii) have noted in this respect, these works «discussed costs to men’s health (both physical and psychological) and the quality of relationships with women, other men, and their children». We should not, nevertheless, forget other important feminist texts of this first wave of studies of masculinities that explored the costs but also the privileges of being a man in contemporary culture (Kimmel and Messner, 1998 , xiv) such as JosephPleckandJack Sawyer’s Men and Masculinity ( 1974 ).

Such a perspective can be seen in several recent works, such as Harry Brod ( 1987 ); Michael Kimmel ( 1987 ; 2000 ); Raewyn Connell ( 1998 ); Jeff Hearn ( Gender ); and Michael Kimmel and Michael Messner ( 1989 ). Probably, Connell’s Gender and Power ( 1987 ), represent «the most sophisticated theoretical statements of this perspective» (Kimmel and Messner, 1998 , xv).

Harry Brod ( 1994 , 82–3) provides a genealogy of the term masculinities in its present usage.

Some authors already speak of a fourth wave of feminism, which could be situated from the 2010s onwards, particularly influenced by technology, social networks, and the # MeToo movement. Personally, I consider it is still too venturesome, nonetheless, to speak of a fourth phase, mainly based on «the means»—in other words, technology and digitalization—rather than the ends of feminist thinking, even recognizing its enormous influence on the movement.

Petersen ( 2003 , 61) himself acknowledges, however, that there are in-between positions. For example, psychoanalysis often intersects with socially informed theories. Although grounded in social constructionism, the present study will itself rely on different disciplines (see chapter 3 ), including psychology and psychoanalysis. It does indeed seem both possible and desirable to move away from psychological or sociological reductionism, since psychological and sociological approaches to gender often complement each other and are not always mutually exclusive.

Armengol (ed.). Aging Masculinities in Contemporary U.S. Fiction . New York: Palgrave, 2021.

Google Scholar

———. “Past, Present (and Future) of Studies of Literary Masculinities: A Case Study in Intersectionality.” Men and Masculinities 22.1 (2019): 64–74.

Armengol, Josep M. et al. (eds.). Masculinities and Literary Studies: Intersections and New Directions . New York: Routledge, 2017.

Brod, Harry. “Envy: Or with My Brains and Your Looks.” Men in Feminism . Ed. Alice Jardine and Paul Smith. New York and London: Methuen, 1987. 233–41.

———. “Some Thoughts on Some Histories of Some Masculinities: Jews and Other Others.” Theorizing Masculinities . Ed. Harry Brod and Michael Kaufman. Thousand Oaks: Sage, 1994. 82–96.

———. “The Case for Men’s Studies.” The Making of Masculinities: The New Men’s Studies . Ed. Harry Brod. Boston: Allen and Unwin, 1987. 39–62.

Connell, Raewyn. Gender and Power [1987]. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1998.

English, Deirdre. Mother Jones . San Francisco: Mother Jones Reprint, 1980.

Farrell, Warren. The Liberated Man . New York: Random House, 1974.

Kidder, Kristen M. “Men’s Studies.” Encyclopedia of Men and Masculinity , 30 August 2002. http://www.referenceworld.com/mosgroup/masculinity/mstudies.html .

Kimmel, Michael (ed.). Changing Men. New Directions in Research on Men and Masculinity . Newsbury Park: Sage, 1987.

———. Manhood in America: A Cultural History [1996]. New York: The Free Press, 1997.

———. The Gendered Society . New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000.

———. “Violence.” Men and Masculinities: A Social, Cultural, and Historical Encyclopedia . 2 vols. Ed. Michael Kimmel and Amy Aronson. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-Clio Press, 2003. 809–12.

Kimmel, Michael and Michael Messner. “Introduction.” Men’s Lives . Ed. Michael Kimmel and Michael Messner [1989]. Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 1998. ix–xvii.

May, Elaine Tyler. “Prologue.” Him/Her/Self: Gender Identities in Modern America . Ed. De Peter G. Filene. 1974. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998. ix–xiv.

Middleton, Peter. The Inward Gaze. Masculinity and Subjectivity in Modern Culture . London and New York: Routledge, 1990.

Newton, Judith. “Masculinity Studies: The Longed for Profeminist Movement for Academic Men?” Masculinity Studies and Feminist Theory: New Directions . Ed. Judith Kegan Gardiner. New York: Columbia University Press, 2002. 176–92.

Petersen, Alan. “Research on Men and Masculinities: Some Implications of Recent Theory for Future Work.” Men and Masculinities 6.1 (2003): 54–69.

Pleck, Joseph and Jack Sawyer (eds.). Men and Masculinity . Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1974.

Robinson, Sally. Marked Men: White Masculinity in Crisis . New York: Columbia University Press, 2000.

Book Google Scholar

Rotundo, E. Anthony. American Manhood: Transformations in Masculinity from the Revolution to the Modern Era . New York: Basic Books, 1993.

The Men’s Bibliography: A Comprehensive Bibliography of Writing on Men, Masculinities, Gender, and Sexualities . Ed. Michael Flood, 4 January 2022. http://www.xyonline.net/mensbiblio/ .

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Modern Philology, University of Castilla-La Mancha, Ciudad Real, Spain

Josep M. Armengol

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Josep M. Armengol .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2024 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Armengol, J.M. (2024). Studies of Masculinities: State of the Art and Latest Trends. In: Rewriting White Masculinities in Contemporary Fiction and Film. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-53349-5_2

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-53349-5_2

Published : 26 March 2024

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-031-53348-8

Online ISBN : 978-3-031-53349-5

eBook Packages : Literature, Cultural and Media Studies Literature, Cultural and Media Studies (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Affiliate Program

- UNITED STATES

- 台灣 (TAIWAN)

- TÜRKIYE (TURKEY)

- Academic Editing Services

- - Research Paper

- - Journal Manuscript

- - Dissertation

- - College & University Assignments

- Admissions Editing Services

- - Application Essay

- - Personal Statement

- - Recommendation Letter

- - Cover Letter

- - CV/Resume

- Business Editing Services

- - Business Documents

- - Report & Brochure

- - Website & Blog

- Writer Editing Services

- - Script & Screenplay

- Our Editors

- Client Reviews

- Editing & Proofreading Prices

- Wordvice Points

- Partner Discount

- Plagiarism Checker

- APA Citation Generator

- MLA Citation Generator

- Chicago Citation Generator

- Vancouver Citation Generator

- - APA Style

- - MLA Style

- - Chicago Style

- - Vancouver Style

- Writing & Editing Guide

- Academic Resources

- Admissions Resources

College Application Essay Format Rules

The college application essay has become the most important part of applying to college. In this article, we will go over the best college essay format for getting into top schools, including how to structure the elements of a college admissions essay: margins, font, paragraphs, spacing, headers, and organization.

We will focus on commonly asked questions about the best college essay structure. Finally, we will go over essay formatting tips and examples.

Table of Contents

- General college essay formatting rules

- How to format a college admissions essay

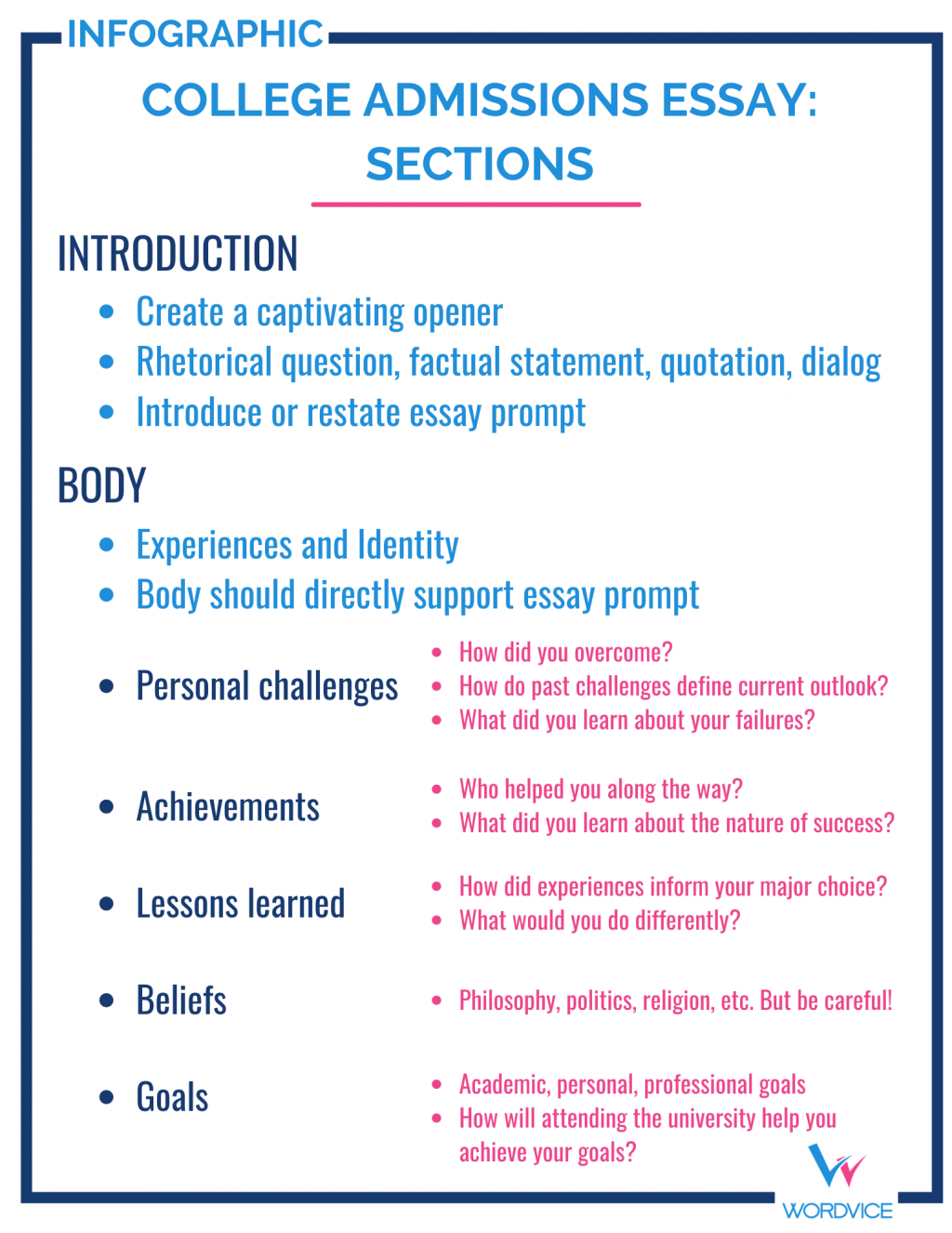

- Sections of a college admissions essay

- College application essay format examples

General College Essay Format Rules

Before talking about how to format your college admission essays, we need to talk about general college essay formatting rules.

Pay attention to word count

It has been well-established that the most important rule of college application essays is to not go over the specific Application Essay word limit . The word limit for the Common Application essay is typically 500-650 words.

Not only may it be impossible to go over the word count (in the case of the Common Application essay , which uses text fields), but admissions officers often use software that will throw out any essay that breaks this rule. Following directions is a key indicator of being a successful student.

Refocusing on the essay prompt and eliminating unnecessary adverbs, filler words, and prepositional phrases will help improve your essay.

On the other hand, it is advisable to use almost every available word. The college essay application field is very competitive, so leaving extra words on the table puts you at a disadvantage. Include an example or anecdote near the end of your essay to meet the total word count.

Do not write a wall of text: use paragraphs

Here is a brutal truth: College admissions counselors only read the application essays that help them make a decision . Otherwise, they will not read the essay at all. The problem is that you do not know whether the rest of your application (transcripts, academic record, awards, etc.) will be competitive enough to get you accepted.

A very simple writing rule for your application essay (and for essay editing of any type) is to make your writing readable by adding line breaks and separate paragraphs.

Line breaks do not count toward word count, so they are a very easy way to organize your essay structure, ideas, and topics. Remember, college counselors, if you’re lucky, will spend 30 sec to 1 minute reading your essay. Give them every opportunity to understand your writing.

Do not include an essay title

Unless specifically required, do not use a title for your personal statement or essay. This is a waste of your word limit and is redundant since the essay prompt itself serves as the title.

Never use overly casual, colloquial, or text message-based formatting like this:

THIS IS A REALLY IMPORTANT POINT!. #collegeapplication #collegeessay.

Under no circumstances should you use emojis, all caps, symbols, hashtags, or slang in a college essay. Although technology, texting, and social media are continuing to transform how we use modern language (what a great topic for a college application essay!), admissions officers will view the use of these casual formatting elements as immature and inappropriate for such an important document.

How To Format A College Application Essay

There are many tips for writing college admissions essays . How you upload your college application essay depends on whether you will be cutting and pasting your essay into a text box in an online application form or attaching a formatted document.

Save and upload your college essay in the proper format

Check the application instructions if you’re not sure what you need to do. Currently, the Common Application requires you to copy and paste your essay into a text box.

There are three main formats when it comes to submitting your college essay or personal statement:

If submitting your application essay in a text box

For the Common Application, there is no need to attach a document since there is a dedicated input field. You still want to write your essay in a word processor or Google doc. Just make sure once you copy-paste your essay into the text box that your line breaks (paragraphs), indents, and formatting is retained.

- Formatting like bold , underline, and italics are often lost when copy-pasting into a text box.

- Double-check that you are under the word limit. Word counts may be different within the text box .

- Make sure that paragraphs and spacing are maintained; text input fields often undo indents and double-spacing .

- If possible, make sure the font is standardized. Text input boxes usually allow just one font .

If submitting your application essay as a document

When attaching a document, you must do more than just double-check the format of your admissions essay. You need to be proactive and make sure the structure is logical and will be attractive to readers.

Microsoft Word (.DOC) format

If you are submitting your application essay as a file upload, then you will likely submit a .doc or .docx file. The downside is that MS Word files are editable, and there are sometimes conflicts between different MS Word versions (2010 vs 2016 vs Office365). The upside is that Word can be opened by almost any text program.