- Privacy Policy

Home » Data Collection – Methods Types and Examples

Data Collection – Methods Types and Examples

Table of Contents

Data Collection

Definition:

Data collection is the process of gathering and collecting information from various sources to analyze and make informed decisions based on the data collected. This can involve various methods, such as surveys, interviews, experiments, and observation.

In order for data collection to be effective, it is important to have a clear understanding of what data is needed and what the purpose of the data collection is. This can involve identifying the population or sample being studied, determining the variables to be measured, and selecting appropriate methods for collecting and recording data.

Types of Data Collection

Types of Data Collection are as follows:

Primary Data Collection

Primary data collection is the process of gathering original and firsthand information directly from the source or target population. This type of data collection involves collecting data that has not been previously gathered, recorded, or published. Primary data can be collected through various methods such as surveys, interviews, observations, experiments, and focus groups. The data collected is usually specific to the research question or objective and can provide valuable insights that cannot be obtained from secondary data sources. Primary data collection is often used in market research, social research, and scientific research.

Secondary Data Collection

Secondary data collection is the process of gathering information from existing sources that have already been collected and analyzed by someone else, rather than conducting new research to collect primary data. Secondary data can be collected from various sources, such as published reports, books, journals, newspapers, websites, government publications, and other documents.

Qualitative Data Collection

Qualitative data collection is used to gather non-numerical data such as opinions, experiences, perceptions, and feelings, through techniques such as interviews, focus groups, observations, and document analysis. It seeks to understand the deeper meaning and context of a phenomenon or situation and is often used in social sciences, psychology, and humanities. Qualitative data collection methods allow for a more in-depth and holistic exploration of research questions and can provide rich and nuanced insights into human behavior and experiences.

Quantitative Data Collection

Quantitative data collection is a used to gather numerical data that can be analyzed using statistical methods. This data is typically collected through surveys, experiments, and other structured data collection methods. Quantitative data collection seeks to quantify and measure variables, such as behaviors, attitudes, and opinions, in a systematic and objective way. This data is often used to test hypotheses, identify patterns, and establish correlations between variables. Quantitative data collection methods allow for precise measurement and generalization of findings to a larger population. It is commonly used in fields such as economics, psychology, and natural sciences.

Data Collection Methods

Data Collection Methods are as follows:

Surveys involve asking questions to a sample of individuals or organizations to collect data. Surveys can be conducted in person, over the phone, or online.

Interviews involve a one-on-one conversation between the interviewer and the respondent. Interviews can be structured or unstructured and can be conducted in person or over the phone.

Focus Groups

Focus groups are group discussions that are moderated by a facilitator. Focus groups are used to collect qualitative data on a specific topic.

Observation

Observation involves watching and recording the behavior of people, objects, or events in their natural setting. Observation can be done overtly or covertly, depending on the research question.

Experiments

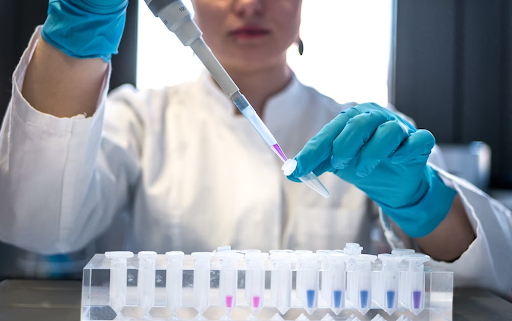

Experiments involve manipulating one or more variables and observing the effect on another variable. Experiments are commonly used in scientific research.

Case Studies

Case studies involve in-depth analysis of a single individual, organization, or event. Case studies are used to gain detailed information about a specific phenomenon.

Secondary Data Analysis

Secondary data analysis involves using existing data that was collected for another purpose. Secondary data can come from various sources, such as government agencies, academic institutions, or private companies.

How to Collect Data

The following are some steps to consider when collecting data:

- Define the objective : Before you start collecting data, you need to define the objective of the study. This will help you determine what data you need to collect and how to collect it.

- Identify the data sources : Identify the sources of data that will help you achieve your objective. These sources can be primary sources, such as surveys, interviews, and observations, or secondary sources, such as books, articles, and databases.

- Determine the data collection method : Once you have identified the data sources, you need to determine the data collection method. This could be through online surveys, phone interviews, or face-to-face meetings.

- Develop a data collection plan : Develop a plan that outlines the steps you will take to collect the data. This plan should include the timeline, the tools and equipment needed, and the personnel involved.

- Test the data collection process: Before you start collecting data, test the data collection process to ensure that it is effective and efficient.

- Collect the data: Collect the data according to the plan you developed in step 4. Make sure you record the data accurately and consistently.

- Analyze the data: Once you have collected the data, analyze it to draw conclusions and make recommendations.

- Report the findings: Report the findings of your data analysis to the relevant stakeholders. This could be in the form of a report, a presentation, or a publication.

- Monitor and evaluate the data collection process: After the data collection process is complete, monitor and evaluate the process to identify areas for improvement in future data collection efforts.

- Ensure data quality: Ensure that the collected data is of high quality and free from errors. This can be achieved by validating the data for accuracy, completeness, and consistency.

- Maintain data security: Ensure that the collected data is secure and protected from unauthorized access or disclosure. This can be achieved by implementing data security protocols and using secure storage and transmission methods.

- Follow ethical considerations: Follow ethical considerations when collecting data, such as obtaining informed consent from participants, protecting their privacy and confidentiality, and ensuring that the research does not cause harm to participants.

- Use appropriate data analysis methods : Use appropriate data analysis methods based on the type of data collected and the research objectives. This could include statistical analysis, qualitative analysis, or a combination of both.

- Record and store data properly: Record and store the collected data properly, in a structured and organized format. This will make it easier to retrieve and use the data in future research or analysis.

- Collaborate with other stakeholders : Collaborate with other stakeholders, such as colleagues, experts, or community members, to ensure that the data collected is relevant and useful for the intended purpose.

Applications of Data Collection

Data collection methods are widely used in different fields, including social sciences, healthcare, business, education, and more. Here are some examples of how data collection methods are used in different fields:

- Social sciences : Social scientists often use surveys, questionnaires, and interviews to collect data from individuals or groups. They may also use observation to collect data on social behaviors and interactions. This data is often used to study topics such as human behavior, attitudes, and beliefs.

- Healthcare : Data collection methods are used in healthcare to monitor patient health and track treatment outcomes. Electronic health records and medical charts are commonly used to collect data on patients’ medical history, diagnoses, and treatments. Researchers may also use clinical trials and surveys to collect data on the effectiveness of different treatments.

- Business : Businesses use data collection methods to gather information on consumer behavior, market trends, and competitor activity. They may collect data through customer surveys, sales reports, and market research studies. This data is used to inform business decisions, develop marketing strategies, and improve products and services.

- Education : In education, data collection methods are used to assess student performance and measure the effectiveness of teaching methods. Standardized tests, quizzes, and exams are commonly used to collect data on student learning outcomes. Teachers may also use classroom observation and student feedback to gather data on teaching effectiveness.

- Agriculture : Farmers use data collection methods to monitor crop growth and health. Sensors and remote sensing technology can be used to collect data on soil moisture, temperature, and nutrient levels. This data is used to optimize crop yields and minimize waste.

- Environmental sciences : Environmental scientists use data collection methods to monitor air and water quality, track climate patterns, and measure the impact of human activity on the environment. They may use sensors, satellite imagery, and laboratory analysis to collect data on environmental factors.

- Transportation : Transportation companies use data collection methods to track vehicle performance, optimize routes, and improve safety. GPS systems, on-board sensors, and other tracking technologies are used to collect data on vehicle speed, fuel consumption, and driver behavior.

Examples of Data Collection

Examples of Data Collection are as follows:

- Traffic Monitoring: Cities collect real-time data on traffic patterns and congestion through sensors on roads and cameras at intersections. This information can be used to optimize traffic flow and improve safety.

- Social Media Monitoring : Companies can collect real-time data on social media platforms such as Twitter and Facebook to monitor their brand reputation, track customer sentiment, and respond to customer inquiries and complaints in real-time.

- Weather Monitoring: Weather agencies collect real-time data on temperature, humidity, air pressure, and precipitation through weather stations and satellites. This information is used to provide accurate weather forecasts and warnings.

- Stock Market Monitoring : Financial institutions collect real-time data on stock prices, trading volumes, and other market indicators to make informed investment decisions and respond to market fluctuations in real-time.

- Health Monitoring : Medical devices such as wearable fitness trackers and smartwatches can collect real-time data on a person’s heart rate, blood pressure, and other vital signs. This information can be used to monitor health conditions and detect early warning signs of health issues.

Purpose of Data Collection

The purpose of data collection can vary depending on the context and goals of the study, but generally, it serves to:

- Provide information: Data collection provides information about a particular phenomenon or behavior that can be used to better understand it.

- Measure progress : Data collection can be used to measure the effectiveness of interventions or programs designed to address a particular issue or problem.

- Support decision-making : Data collection provides decision-makers with evidence-based information that can be used to inform policies, strategies, and actions.

- Identify trends : Data collection can help identify trends and patterns over time that may indicate changes in behaviors or outcomes.

- Monitor and evaluate : Data collection can be used to monitor and evaluate the implementation and impact of policies, programs, and initiatives.

When to use Data Collection

Data collection is used when there is a need to gather information or data on a specific topic or phenomenon. It is typically used in research, evaluation, and monitoring and is important for making informed decisions and improving outcomes.

Data collection is particularly useful in the following scenarios:

- Research : When conducting research, data collection is used to gather information on variables of interest to answer research questions and test hypotheses.

- Evaluation : Data collection is used in program evaluation to assess the effectiveness of programs or interventions, and to identify areas for improvement.

- Monitoring : Data collection is used in monitoring to track progress towards achieving goals or targets, and to identify any areas that require attention.

- Decision-making: Data collection is used to provide decision-makers with information that can be used to inform policies, strategies, and actions.

- Quality improvement : Data collection is used in quality improvement efforts to identify areas where improvements can be made and to measure progress towards achieving goals.

Characteristics of Data Collection

Data collection can be characterized by several important characteristics that help to ensure the quality and accuracy of the data gathered. These characteristics include:

- Validity : Validity refers to the accuracy and relevance of the data collected in relation to the research question or objective.

- Reliability : Reliability refers to the consistency and stability of the data collection process, ensuring that the results obtained are consistent over time and across different contexts.

- Objectivity : Objectivity refers to the impartiality of the data collection process, ensuring that the data collected is not influenced by the biases or personal opinions of the data collector.

- Precision : Precision refers to the degree of accuracy and detail in the data collected, ensuring that the data is specific and accurate enough to answer the research question or objective.

- Timeliness : Timeliness refers to the efficiency and speed with which the data is collected, ensuring that the data is collected in a timely manner to meet the needs of the research or evaluation.

- Ethical considerations : Ethical considerations refer to the ethical principles that must be followed when collecting data, such as ensuring confidentiality and obtaining informed consent from participants.

Advantages of Data Collection

There are several advantages of data collection that make it an important process in research, evaluation, and monitoring. These advantages include:

- Better decision-making : Data collection provides decision-makers with evidence-based information that can be used to inform policies, strategies, and actions, leading to better decision-making.

- Improved understanding: Data collection helps to improve our understanding of a particular phenomenon or behavior by providing empirical evidence that can be analyzed and interpreted.

- Evaluation of interventions: Data collection is essential in evaluating the effectiveness of interventions or programs designed to address a particular issue or problem.

- Identifying trends and patterns: Data collection can help identify trends and patterns over time that may indicate changes in behaviors or outcomes.

- Increased accountability: Data collection increases accountability by providing evidence that can be used to monitor and evaluate the implementation and impact of policies, programs, and initiatives.

- Validation of theories: Data collection can be used to test hypotheses and validate theories, leading to a better understanding of the phenomenon being studied.

- Improved quality: Data collection is used in quality improvement efforts to identify areas where improvements can be made and to measure progress towards achieving goals.

Limitations of Data Collection

While data collection has several advantages, it also has some limitations that must be considered. These limitations include:

- Bias : Data collection can be influenced by the biases and personal opinions of the data collector, which can lead to inaccurate or misleading results.

- Sampling bias : Data collection may not be representative of the entire population, resulting in sampling bias and inaccurate results.

- Cost : Data collection can be expensive and time-consuming, particularly for large-scale studies.

- Limited scope: Data collection is limited to the variables being measured, which may not capture the entire picture or context of the phenomenon being studied.

- Ethical considerations : Data collection must follow ethical principles to protect the rights and confidentiality of the participants, which can limit the type of data that can be collected.

- Data quality issues: Data collection may result in data quality issues such as missing or incomplete data, measurement errors, and inconsistencies.

- Limited generalizability : Data collection may not be generalizable to other contexts or populations, limiting the generalizability of the findings.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Research Process – Steps, Examples and Tips

Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

Institutional Review Board – Application Sample...

Evaluating Research – Process, Examples and...

Research Questions – Types, Examples and Writing...

Data collection in research: Your complete guide

Last updated

31 January 2023

Reviewed by

Cathy Heath

In the late 16th century, Francis Bacon coined the phrase "knowledge is power," which implies that knowledge is a powerful force, like physical strength. In the 21st century, knowledge in the form of data is unquestionably powerful.

But data isn't something you just have - you need to collect it. This means utilizing a data collection process and turning the collected data into knowledge that you can leverage into a successful strategy for your business or organization.

Believe it or not, there's more to data collection than just conducting a Google search. In this complete guide, we shine a spotlight on data collection, outlining what it is, types of data collection methods, common challenges in data collection, data collection techniques, and the steps involved in data collection.

Analyze all your data in one place

Uncover hidden nuggets in all types of qualitative data when you analyze it in Dovetail

- What is data collection?

There are two specific data collection techniques: primary and secondary data collection. Primary data collection is the process of gathering data directly from sources. It's often considered the most reliable data collection method, as researchers can collect information directly from respondents.

Secondary data collection is data that has already been collected by someone else and is readily available. This data is usually less expensive and quicker to obtain than primary data.

- What are the different methods of data collection?

There are several data collection methods, which can be either manual or automated. Manual data collection involves collecting data manually, typically with pen and paper, while computerized data collection involves using software to collect data from online sources, such as social media, website data, transaction data, etc.

Here are the five most popular methods of data collection:

Surveys are a very popular method of data collection that organizations can use to gather information from many people. Researchers can conduct multi-mode surveys that reach respondents in different ways, including in person, by mail, over the phone, or online.

As a method of data collection, surveys have several advantages. For instance, they are relatively quick and easy to administer, you can be flexible in what you ask, and they can be tailored to collect data on various topics or from certain demographics.

However, surveys also have several disadvantages. For instance, they can be expensive to administer, and the results may not represent the population as a whole. Additionally, survey data can be challenging to interpret. It may also be subject to bias if the questions are not well-designed or if the sample of people surveyed is not representative of the population of interest.

Interviews are a common method of collecting data in social science research. You can conduct interviews in person, over the phone, or even via email or online chat.

Interviews are a great way to collect qualitative and quantitative data . Qualitative interviews are likely your best option if you need to collect detailed information about your subjects' experiences or opinions. If you need to collect more generalized data about your subjects' demographics or attitudes, then quantitative interviews may be a better option.

Interviews are relatively quick and very flexible, allowing you to ask follow-up questions and explore topics in more depth. The downside is that interviews can be time-consuming and expensive due to the amount of information to be analyzed. They are also prone to bias, as both the interviewer and the respondent may have certain expectations or preconceptions that may influence the data.

Direct observation

Observation is a direct way of collecting data. It can be structured (with a specific protocol to follow) or unstructured (simply observing without a particular plan).

Organizations and businesses use observation as a data collection method to gather information about their target market, customers, or competition. Businesses can learn about consumer behavior, preferences, and trends by observing people using their products or service.

There are two types of observation: participatory and non-participatory. In participatory observation, the researcher is actively involved in the observed activities. This type of observation is used in ethnographic research , where the researcher wants to understand a group's culture and social norms. Non-participatory observation is when researchers observe from a distance and do not interact with the people or environment they are studying.

There are several advantages to using observation as a data collection method. It can provide insights that may not be apparent through other methods, such as surveys or interviews. Researchers can also observe behavior in a natural setting, which can provide a more accurate picture of what people do and how and why they behave in a certain context.

There are some disadvantages to using observation as a method of data collection. It can be time-consuming, intrusive, and expensive to observe people for extended periods. Observations can also be tainted if the researcher is not careful to avoid personal biases or preconceptions.

Automated data collection

Business applications and websites are increasingly collecting data electronically to improve the user experience or for marketing purposes.

There are a few different ways that organizations can collect data automatically. One way is through cookies, which are small pieces of data stored on a user's computer. They track a user's browsing history and activity on a site, measuring levels of engagement with a business’s products or services, for example.

Another way organizations can collect data automatically is through web beacons. Web beacons are small images embedded on a web page to track a user's activity.

Finally, organizations can also collect data through mobile apps, which can track user location, device information, and app usage. This data can be used to improve the user experience and for marketing purposes.

Automated data collection is a valuable tool for businesses, helping improve the user experience or target marketing efforts. Businesses should aim to be transparent about how they collect and use this data.

Sourcing data through information service providers

Organizations need to be able to collect data from a variety of sources, including social media, weblogs, and sensors. The process to do this and then use the data for action needs to be efficient, targeted, and meaningful.

In the era of big data, organizations are increasingly turning to information service providers (ISPs) and other external data sources to help them collect data to make crucial decisions.

Information service providers help organizations collect data by offering personalized services that suit the specific needs of the organizations. These services can include data collection, analysis, management, and reporting. By partnering with an ISP, organizations can gain access to the newest technology and tools to help them to gather and manage data more effectively.

There are also several tools and techniques that organizations can use to collect data from external sources, such as web scraping, which collects data from websites, and data mining, which involves using algorithms to extract data from large data sets.

Organizations can also use APIs (application programming interface) to collect data from external sources. APIs allow organizations to access data stored in another system and share and integrate it into their own systems.

Finally, organizations can also use manual methods to collect data from external sources. This can involve contacting companies or individuals directly to request data, by using the right tools and methods to get the insights they need.

- What are common challenges in data collection?

There are many challenges that researchers face when collecting data. Here are five common examples:

Big data environments

Data collection can be a challenge in big data environments for several reasons. It can be located in different places, such as archives, libraries, or online. The sheer volume of data can also make it difficult to identify the most relevant data sets.

Second, the complexity of data sets can make it challenging to extract the desired information. Third, the distributed nature of big data environments can make it difficult to collect data promptly and efficiently.

Therefore it is important to have a well-designed data collection strategy to consider the specific needs of the organization and what data sets are the most relevant. Alongside this, consideration should be made regarding the tools and resources available to support data collection and protect it from unintended use.

Data bias is a common challenge in data collection. It occurs when data is collected from a sample that is not representative of the population of interest.

There are different types of data bias, but some common ones include selection bias, self-selection bias, and response bias. Selection bias can occur when the collected data does not represent the population being studied. For example, if a study only includes data from people who volunteer to participate, that data may not represent the general population.

Self-selection bias can also occur when people self-select into a study, such as by taking part only if they think they will benefit from it. Response bias happens when people respond in a way that is not honest or accurate, such as by only answering questions that make them look good.

These types of data bias present a challenge because they can lead to inaccurate results and conclusions about behaviors, perceptions, and trends. Data bias can be avoided by identifying potential sources or themes of bias and setting guidelines for eliminating them.

Lack of quality assurance processes

One of the biggest challenges in data collection is the lack of quality assurance processes. This can lead to several problems, including incorrect data, missing data, and inconsistencies between data sets.

Quality assurance is important because there are many data sources, and each source may have different levels of quality or corruption. There are also different ways of collecting data, and data quality may vary depending on the method used.

There are several ways to improve quality assurance in data collection. These include developing clear and consistent goals and guidelines for data collection, implementing quality control measures, using standardized procedures, and employing data validation techniques. By taking these steps, you can ensure that your data is of adequate quality to inform decision-making.

Limited access to data

Another challenge in data collection is limited access to data. This can be due to several reasons, including privacy concerns, the sensitive nature of the data, security concerns, or simply the fact that data is not readily available.

Legal and compliance regulations

Most countries have regulations governing how data can be collected, used, and stored. In some cases, data collected in one country may not be used in another. This means gaining a global perspective can be a challenge.

For example, if a company is required to comply with the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), it may not be able to collect data from individuals in the EU without their explicit consent. This can make it difficult to collect data from a target audience.

Legal and compliance regulations can be complex, and it's important to ensure that all data collected is done so in a way that complies with the relevant regulations.

- What are the key steps in the data collection process?

There are five steps involved in the data collection process. They are:

1. Decide what data you want to gather

Have a clear understanding of the questions you are asking, and then consider where the answers might lie and how you might obtain them. This saves time and resources by avoiding the collection of irrelevant data, and helps maintain the quality of your datasets.

2. Establish a deadline for data collection

Establishing a deadline for data collection helps you avoid collecting too much data, which can be costly and time-consuming to analyze. It also allows you to plan for data analysis and prompt interpretation. Finally, it helps you meet your research goals and objectives and allows you to move forward.

3. Select a data collection approach

The data collection approach you choose will depend on different factors, including the type of data you need, available resources, and the project timeline. For instance, if you need qualitative data, you might choose a focus group or interview methodology. If you need quantitative data , then a survey or observational study may be the most appropriate form of collection.

4. Gather information

When collecting data for your business, identify your business goals first. Once you know what you want to achieve, you can start collecting data to reach those goals. The most important thing is to ensure that the data you collect is reliable and valid. Otherwise, any decisions you make using the data could result in a negative outcome for your business.

5. Examine the information and apply your findings

As a researcher, it's important to examine the data you're collecting and analyzing before you apply your findings. This is because data can be misleading, leading to inaccurate conclusions. Ask yourself whether it is what you are expecting? Is it similar to other datasets you have looked at?

There are many scientific ways to examine data, but some common methods include:

looking at the distribution of data points

examining the relationships between variables

looking for outliers

By taking the time to examine your data and noticing any patterns, strange or otherwise, you can avoid making mistakes that could invalidate your research.

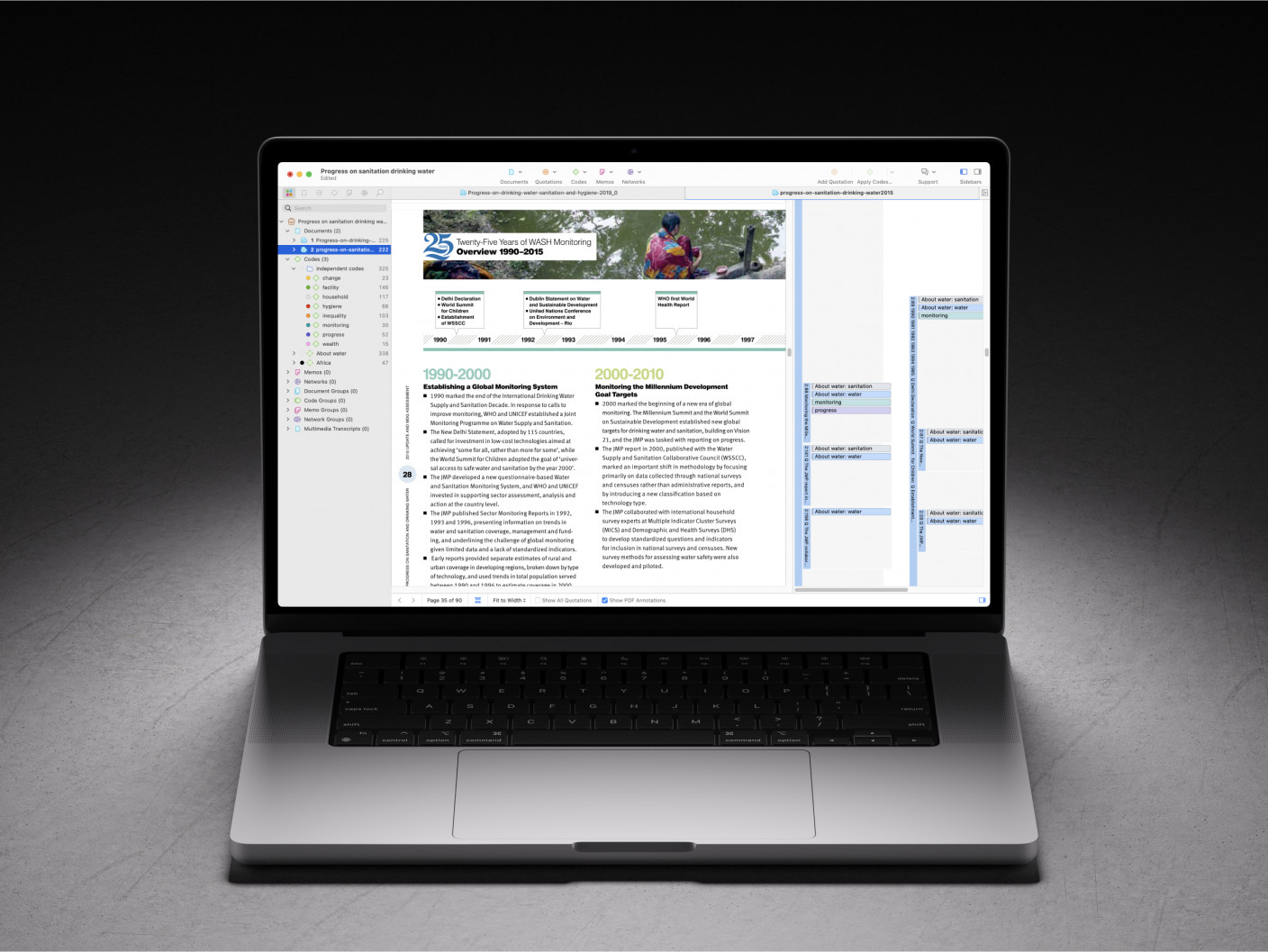

- How qualitative analysis software streamlines the data collection process

Knowledge derived from data does indeed carry power. However, if you don't convert the knowledge into action, it will remain a resource of unexploited energy and wasted potential.

Luckily, data collection tools enable organizations to streamline their data collection and analysis processes and leverage the derived knowledge to grow their businesses. For instance, qualitative analysis software can be highly advantageous in data collection by streamlining the process, making it more efficient and less time-consuming.

Secondly, qualitative analysis software provides a structure for data collection and analysis, ensuring that data is of high quality. It can also help to uncover patterns and relationships that would otherwise be difficult to discern. Moreover, you can use it to replace more expensive data collection methods, such as focus groups or surveys.

Overall, qualitative analysis software can be valuable for any researcher looking to collect and analyze data. By increasing efficiency, improving data quality, and providing greater insights, qualitative software can help to make the research process much more efficient and effective.

Learn more about qualitative research data analysis software

Should you be using a customer insights hub.

Do you want to discover previous research faster?

Do you share your research findings with others?

Do you analyze research data?

Start for free today, add your research, and get to key insights faster

Editor’s picks

Last updated: 11 January 2024

Last updated: 15 January 2024

Last updated: 17 January 2024

Last updated: 12 May 2023

Last updated: 30 April 2024

Last updated: 18 May 2023

Last updated: 25 November 2023

Last updated: 13 May 2024

Latest articles

Related topics, .css-je19u9{-webkit-align-items:flex-end;-webkit-box-align:flex-end;-ms-flex-align:flex-end;align-items:flex-end;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-flex-direction:row;-ms-flex-direction:row;flex-direction:row;-webkit-box-flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-box-pack:center;-ms-flex-pack:center;-webkit-justify-content:center;justify-content:center;row-gap:0;text-align:center;max-width:671px;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}}@media (max-width: 799px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}} decide what to .css-1kiodld{max-height:56px;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-1kiodld{display:none;}} build next, decide what to build next.

Users report unexpectedly high data usage, especially during streaming sessions.

Users find it hard to navigate from the home page to relevant playlists in the app.

It would be great to have a sleep timer feature, especially for bedtime listening.

I need better filters to find the songs or artists I’m looking for.

Log in or sign up

Get started for free

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- QuestionPro

- Solutions Industries Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Cannabis Technology Use Case NPS+ Communities Audience Contactless surveys Mobile LivePolls Member Experience GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Help center

Home Market Research

Data Collection: What It Is, Methods & Tools + Examples

Let’s face it, no one wants to make decisions based on guesswork or gut feelings. The most important objective of data collection is to ensure that the data gathered is reliable and packed to the brim with juicy insights that can be analyzed and turned into data-driven decisions. There’s nothing better than good statistical analysis .

LEARN ABOUT: Level of Analysis

Collecting high-quality data is essential for conducting market research, analyzing user behavior, or just trying to get a handle on business operations. With the right approach and a few handy tools, gathering reliable and informative data.

So, let’s get ready to collect some data because when it comes to data collection, it’s all about the details.

Content Index

What is Data Collection?

Data collection methods, data collection examples, reasons to conduct online research and data collection, conducting customer surveys for data collection to multiply sales, steps to effectively conduct an online survey for data collection, survey design for data collection.

Data collection is the procedure of collecting, measuring, and analyzing accurate insights for research using standard validated techniques.

Put simply, data collection is the process of gathering information for a specific purpose. It can be used to answer research questions, make informed business decisions, or improve products and services.

To collect data, we must first identify what information we need and how we will collect it. We can also evaluate a hypothesis based on collected data. In most cases, data collection is the primary and most important step for research. The approach to data collection is different for different fields of study, depending on the required information.

LEARN ABOUT: Action Research

There are many ways to collect information when doing research. The data collection methods that the researcher chooses will depend on the research question posed. Some data collection methods include surveys, interviews, tests, physiological evaluations, observations, reviews of existing records, and biological samples. Let’s explore them.

LEARN ABOUT: Best Data Collection Tools

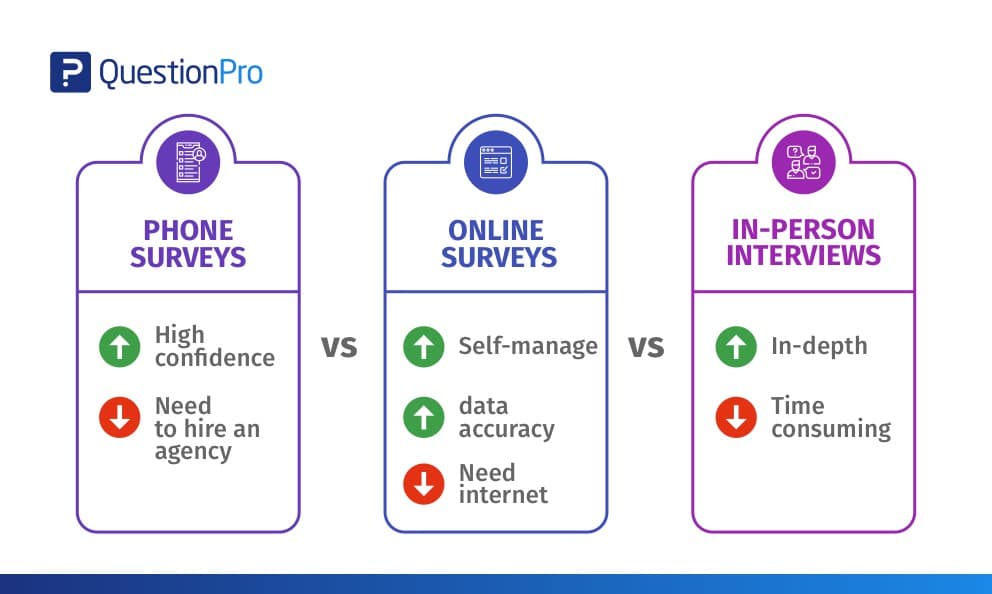

Phone vs. Online vs. In-Person Interviews

Essentially there are four choices for data collection – in-person interviews, mail, phone, and online. There are pros and cons to each of these modes.

- Pros: In-depth and a high degree of confidence in the data

- Cons: Time-consuming, expensive, and can be dismissed as anecdotal

- Pros: Can reach anyone and everyone – no barrier

- Cons: Expensive, data collection errors, lag time

- Pros: High degree of confidence in the data collected, reach almost anyone

- Cons: Expensive, cannot self-administer, need to hire an agency

- Pros: Cheap, can self-administer, very low probability of data errors

- Cons: Not all your customers might have an email address/be on the internet, customers may be wary of divulging information online.

In-person interviews always are better, but the big drawback is the trap you might fall into if you don’t do them regularly. It is expensive to regularly conduct interviews and not conducting enough interviews might give you false positives. Validating your research is almost as important as designing and conducting it.

We’ve seen many instances where after the research is conducted – if the results do not match up with the “gut-feel” of upper management, it has been dismissed off as anecdotal and a “one-time” phenomenon. To avoid such traps, we strongly recommend that data-collection be done on an “ongoing and regular” basis.

LEARN ABOUT: Research Process Steps

This will help you compare and analyze the change in perceptions according to marketing for your products/services. The other issue here is sample size. To be confident with your research, you must interview enough people to weed out the fringe elements.

A couple of years ago there was a lot of discussion about online surveys and their statistical analysis plan . The fact that not every customer had internet connectivity was one of the main concerns.

LEARN ABOUT: Statistical Analysis Methods

Although some of the discussions are still valid, the reach of the internet as a means of communication has become vital in the majority of customer interactions. According to the US Census Bureau, the number of households with computers has doubled between 1997 and 2001.

Learn more: Quantitative Market Research

In 2001 nearly 50% of households had a computer. Nearly 55% of all households with an income of more than 35,000 have internet access, which jumps to 70% for households with an annual income of 50,000. This data is from the US Census Bureau for 2001.

There are primarily three modes of data collection that can be employed to gather feedback – Mail, Phone, and Online. The method actually used for data collection is really a cost-benefit analysis. There is no slam-dunk solution but you can use the table below to understand the risks and advantages associated with each of the mediums:

Keep in mind, the reach here is defined as “All U.S. Households.” In most cases, you need to look at how many of your customers are online and determine. If all your customers have email addresses, you have a 100% reach of your customers.

Another important thing to keep in mind is the ever-increasing dominance of cellular phones over landline phones. United States FCC rules prevent automated dialing and calling cellular phone numbers and there is a noticeable trend towards people having cellular phones as the only voice communication device.

This introduces the inability to reach cellular phone customers who are dropping home phone lines in favor of going entirely wireless. Even if automated dialing is not used, another FCC rule prohibits from phoning anyone who would have to pay for the call.

Learn more: Qualitative Market Research

Multi-Mode Surveys

Surveys, where the data is collected via different modes (online, paper, phone etc.), is also another way of going. It is fairly straightforward and easy to have an online survey and have data-entry operators to enter in data (from the phone as well as paper surveys) into the system. The same system can also be used to collect data directly from the respondents.

Learn more: Survey Research

Data collection is an important aspect of research. Let’s consider an example of a mobile manufacturer, company X, which is launching a new product variant. To conduct research about features, price range, target market, competitor analysis, etc. data has to be collected from appropriate sources.

The marketing team can conduct various data collection activities such as online surveys or focus groups .

The survey should have all the right questions about features and pricing, such as “What are the top 3 features expected from an upcoming product?” or “How much are your likely to spend on this product?” or “Which competitors provide similar products?” etc.

For conducting a focus group, the marketing team should decide the participants and the mediator. The topic of discussion and objective behind conducting a focus group should be clarified beforehand to conduct a conclusive discussion.

Data collection methods are chosen depending on the available resources. For example, conducting questionnaires and surveys would require the least resources, while focus groups require moderately high resources.

Feedback is a vital part of any organization’s growth. Whether you conduct regular focus groups to elicit information from key players or, your account manager calls up all your marquee accounts to find out how things are going – essentially they are all processes to find out from your customers’ eyes – How are we doing? What can we do better?

Online surveys are just another medium to collect feedback from your customers , employees and anyone your business interacts with. With the advent of Do-It-Yourself tools for online surveys, data collection on the internet has become really easy, cheap and effective.

Learn more: Online Research

It is a well-established marketing fact that acquiring a new customer is 10 times more difficult and expensive than retaining an existing one. This is one of the fundamental driving forces behind the extensive adoption and interest in CRM and related customer retention tactics.

In a research study conducted by Rice University Professor Dr. Paul Dholakia and Dr. Vicki Morwitz, published in Harvard Business Review, the experiment inferred that the simple fact of asking customers how an organization was performing by itself to deliver results proved to be an effective customer retention strategy.

In the research study, conducted over the course of a year, one set of customers were sent out a satisfaction and opinion survey and the other set was not surveyed. In the next one year, the group that took the survey saw twice the number of people continuing and renewing their loyalty towards the organization data .

Learn more: Research Design

The research study provided a couple of interesting reasons on the basis of consumer psychology, behind this phenomenon:

- Satisfaction surveys boost the customers’ desire to be coddled and induce positive feelings. This crops from a section of the human psychology that intends to “appreciate” a product or service they already like or prefer. The survey feedback collection method is solely a medium to convey this. The survey is a vehicle to “interact” with the company and reinforces the customer’s commitment to the company.

- Surveys may increase awareness of auxiliary products and services. Surveys can be considered modes of both inbound as well as outbound communication. Surveys are generally considered to be a data collection and analysis source. Most people are unaware of the fact that consumer surveys can also serve as a medium for distributing data. It is important to note a few caveats here.

- In most countries, including the US, “selling under the guise of research” is illegal. b. However, we all know that information is distributed while collecting information. c. Other disclaimers may be included in the survey to ensure users are aware of this fact. For example: “We will collect your opinion and inform you about products and services that have come online in the last year…”

- Induced Judgments: The entire procedure of asking people for their feedback can prompt them to build an opinion on something they otherwise would not have thought about. This is a very underlying yet powerful argument that can be compared to the “Product Placement” strategy currently used for marketing products in mass media like movies and television shows. One example is the extensive and exclusive use of the “mini-Cooper” in the blockbuster movie “Italian Job.” This strategy is questionable and should be used with great caution.

Surveys should be considered as a critical tool in the customer journey dialog. The best thing about surveys is its ability to carry “bi-directional” information. The research conducted by Paul Dholakia and Vicki Morwitz shows that surveys not only get you the information that is critical for your business, but also enhances and builds upon the established relationship you have with your customers.

Recent technological advances have made it incredibly easy to conduct real-time surveys and opinion polls . Online tools make it easy to frame questions and answers and create surveys on the Web. Distributing surveys via email, website links or even integration with online CRM tools like Salesforce.com have made online surveying a quick-win solution.

So, you’ve decided to conduct an online survey. There are a few questions in your mind that you would like answered, and you are looking for a fast and inexpensive way to find out more about your customers, clients, etc.

First and foremost thing you need to decide what the smart objectives of the study are. Ensure that you can phrase these objectives as questions or measurements. If you can’t, you are better off looking at other data sources like focus groups and other qualitative methods . The data collected via online surveys is dominantly quantitative in nature.

Review the basic objectives of the study. What are you trying to discover? What actions do you want to take as a result of the survey? – Answers to these questions help in validating collected data. Online surveys are just one way of collecting and quantifying data .

Learn more: Qualitative Data & Qualitative Data Collection Methods

- Visualize all of the relevant information items you would like to have. What will the output survey research report look like? What charts and graphs will be prepared? What information do you need to be assured that action is warranted?

- Assign ranks to each topic (1 and 2) according to their priority, including the most important topics first. Revisit these items again to ensure that the objectives, topics, and information you need are appropriate. Remember, you can’t solve the research problem if you ask the wrong questions.

- How easy or difficult is it for the respondent to provide information on each topic? If it is difficult, is there an alternative medium to gain insights by asking a different question? This is probably the most important step. Online surveys have to be Precise, Clear and Concise. Due to the nature of the internet and the fluctuations involved, if your questions are too difficult to understand, the survey dropout rate will be high.

- Create a sequence for the topics that are unbiased. Make sure that the questions asked first do not bias the results of the next questions. Sometimes providing too much information, or disclosing purpose of the study can create bias. Once you have a series of decided topics, you can have a basic structure of a survey. It is always advisable to add an “Introductory” paragraph before the survey to explain the project objective and what is expected of the respondent. It is also sensible to have a “Thank You” text as well as information about where to find the results of the survey when they are published.

- Page Breaks – The attention span of respondents can be very low when it comes to a long scrolling survey. Add page breaks as wherever possible. Having said that, a single question per page can also hamper response rates as it increases the time to complete the survey as well as increases the chances for dropouts.

- Branching – Create smart and effective surveys with the implementation of branching wherever required. Eliminate the use of text such as, “If you answered No to Q1 then Answer Q4” – this leads to annoyance amongst respondents which result in increase survey dropout rates. Design online surveys using the branching logic so that appropriate questions are automatically routed based on previous responses.

- Write the questions . Initially, write a significant number of survey questions out of which you can use the one which is best suited for the survey. Divide the survey into sections so that respondents do not get confused seeing a long list of questions.

- Sequence the questions so that they are unbiased.

- Repeat all of the steps above to find any major holes. Are the questions really answered? Have someone review it for you.

- Time the length of the survey. A survey should take less than five minutes. At three to four research questions per minute, you are limited to about 15 questions. One open end text question counts for three multiple choice questions. Most online software tools will record the time taken for the respondents to answer questions.

- Include a few open-ended survey questions that support your survey object. This will be a type of feedback survey.

- Send an email to the project survey to your test group and then email the feedback survey afterward.

- This way, you can have your test group provide their opinion about the functionality as well as usability of your project survey by using the feedback survey.

- Make changes to your questionnaire based on the received feedback.

- Send the survey out to all your respondents!

Online surveys have, over the course of time, evolved into an effective alternative to expensive mail or telephone surveys. However, you must be aware of a few conditions that need to be met for online surveys. If you are trying to survey a sample representing the target population, please remember that not everyone is online.

Moreover, not everyone is receptive to an online survey also. Generally, the demographic segmentation of younger individuals is inclined toward responding to an online survey.

Learn More: Examples of Qualitarive Data in Education

Good survey design is crucial for accurate data collection. From question-wording to response options, let’s explore how to create effective surveys that yield valuable insights with our tips to survey design.

- Writing Great Questions for data collection

Writing great questions can be considered an art. Art always requires a significant amount of hard work, practice, and help from others.

The questions in a survey need to be clear, concise, and unbiased. A poorly worded question or a question with leading language can result in inaccurate or irrelevant responses, ultimately impacting the data’s validity.

Moreover, the questions should be relevant and specific to the research objectives. Questions that are irrelevant or do not capture the necessary information can lead to incomplete or inconsistent responses too.

- Avoid loaded or leading words or questions

A small change in content can produce effective results. Words such as could , should and might are all used for almost the same purpose, but may produce a 20% difference in agreement to a question. For example, “The management could.. should.. might.. have shut the factory”.

Intense words such as – prohibit or action, representing control or action, produce similar results. For example, “Do you believe Donald Trump should prohibit insurance companies from raising rates?”.

Sometimes the content is just biased. For instance, “You wouldn’t want to go to Rudolpho’s Restaurant for the organization’s annual party, would you?”

- Misplaced questions

Questions should always reference the intended context, and questions placed out of order or without its requirement should be avoided. Generally, a funnel approach should be implemented – generic questions should be included in the initial section of the questionnaire as a warm-up and specific ones should follow. Toward the end, demographic or geographic questions should be included.

- Mutually non-overlapping response categories

Multiple-choice answers should be mutually unique to provide distinct choices. Overlapping answer options frustrate the respondent and make interpretation difficult at best. Also, the questions should always be precise.

For example: “Do you like water juice?”

This question is vague. In which terms is the liking for orange juice is to be rated? – Sweetness, texture, price, nutrition etc.

- Avoid the use of confusing/unfamiliar words

Asking about industry-related terms such as caloric content, bits, bytes, MBS , as well as other terms and acronyms can confuse respondents . Ensure that the audience understands your language level, terminology, and, above all, the question you ask.

- Non-directed questions give respondents excessive leeway

In survey design for data collection, non-directed questions can give respondents excessive leeway, which can lead to vague and unreliable data. These types of questions are also known as open-ended questions, and they do not provide any structure for the respondent to follow.

For instance, a non-directed question like “ What suggestions do you have for improving our shoes?” can elicit a wide range of answers, some of which may not be relevant to the research objectives. Some respondents may give short answers, while others may provide lengthy and detailed responses, making comparing and analyzing the data challenging.

To avoid these issues, it’s essential to ask direct questions that are specific and have a clear structure. Closed-ended questions, for example, offer structured response options and can be easier to analyze as they provide a quantitative measure of respondents’ opinions.

- Never force questions

There will always be certain questions that cross certain privacy rules. Since privacy is an important issue for most people, these questions should either be eliminated from the survey or not be kept as mandatory. Survey questions about income, family income, status, religious and political beliefs, etc., should always be avoided as they are considered to be intruding, and respondents can choose not to answer them.

- Unbalanced answer options in scales

Unbalanced answer options in scales such as Likert Scale and Semantic Scale may be appropriate for some situations and biased in others. When analyzing a pattern in eating habits, a study used a quantity scale that made obese people appear in the middle of the scale with the polar ends reflecting a state where people starve and an irrational amount to consume. There are cases where we usually do not expect poor service, such as hospitals.

- Questions that cover two points

In survey design for data collection, questions that cover two points can be problematic for several reasons. These types of questions are often called “double-barreled” questions and can cause confusion for respondents, leading to inaccurate or irrelevant data.

For instance, a question like “Do you like the food and the service at the restaurant?” covers two points, the food and the service, and it assumes that the respondent has the same opinion about both. If the respondent only liked the food, their opinion of the service could affect their answer.

It’s important to ask one question at a time to avoid confusion and ensure that the respondent’s answer is focused and accurate. This also applies to questions with multiple concepts or ideas. In these cases, it’s best to break down the question into multiple questions that address each concept or idea separately.

- Dichotomous questions

Dichotomous questions are used in case you want a distinct answer, such as: Yes/No or Male/Female . For example, the question “Do you think this candidate will win the election?” can be Yes or No.

- Avoid the use of long questions

The use of long questions will definitely increase the time taken for completion, which will generally lead to an increase in the survey dropout rate. Multiple-choice questions are the longest and most complex, and open-ended questions are the shortest and easiest to answer.

Data collection is an essential part of the research process, whether you’re conducting scientific experiments, market research, or surveys. The methods and tools used for data collection will vary depending on the research type, the sample size required, and the resources available.

Several data collection methods include surveys, observations, interviews, and focus groups. We learn each method has advantages and disadvantages, and choosing the one that best suits the research goals is important.

With the rise of technology, many tools are now available to facilitate data collection, including online survey software and data visualization tools. These tools can help researchers collect, store, and analyze data more efficiently, providing greater results and accuracy.

By understanding the various methods and tools available for data collection, we can develop a solid foundation for conducting research. With these research skills , we can make informed decisions, solve problems, and contribute to advancing our understanding of the world around us.

Analyze your survey data to gauge in-depth market drivers, including competitive intelligence, purchasing behavior, and price sensitivity, with QuestionPro.

You will obtain accurate insights with various techniques, including conjoint analysis, MaxDiff analysis, sentiment analysis, TURF analysis, heatmap analysis, etc. Export quality data to external in-depth analysis tools such as SPSS and R Software, and integrate your research with external business applications. Everything you need for your data collection. Start today for free!

LEARN MORE FREE TRIAL

MORE LIKE THIS

Data Information vs Insight: Essential differences

May 14, 2024

Pricing Analytics Software: Optimize Your Pricing Strategy

May 13, 2024

Relationship Marketing: What It Is, Examples & Top 7 Benefits

May 8, 2024

The Best Email Survey Tool to Boost Your Feedback Game

May 7, 2024

Other categories

- Academic Research

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assessments

- Brand Awareness

- Case Studies

- Communities

- Consumer Insights

- Customer effort score

- Customer Engagement

- Customer Experience

- Customer Loyalty

- Customer Research

- Customer Satisfaction

- Employee Benefits

- Employee Engagement

- Employee Retention

- Friday Five

- General Data Protection Regulation

- Insights Hub

- Life@QuestionPro

- Market Research

- Mobile diaries

- Mobile Surveys

- New Features

- Online Communities

- Question Types

- Questionnaire

- QuestionPro Products

- Release Notes

- Research Tools and Apps

- Revenue at Risk

- Survey Templates

- Training Tips

- Uncategorized

- Video Learning Series

- What’s Coming Up

- Workforce Intelligence

The Ultimate Guide to Qualitative Research - Part 1: The Basics

- Introduction and overview

- What is qualitative research?

- What is qualitative data?

- Examples of qualitative data

- Qualitative vs. quantitative research

- Mixed methods

- Qualitative research preparation

- Theoretical perspective

- Theoretical framework

- Literature reviews

- Research question

- Conceptual framework

- Conceptual vs. theoretical framework

- Introduction

Data in research

Data collection methods, challenges in data collection, using technology in data collection, data organization.

- Qualitative research methods

- Focus groups

- Observational research

- Case studies

- Ethnographical research

- Ethical considerations

- Confidentiality and privacy

- Power dynamics

- Reflexivity

Data collection - What is it and why is it important?

The data collected for your study informs the analysis of your research. Gathering data in a transparent and thorough manner informs the rest of your research and makes it persuasive to your audience.

We will look at the data collection process, the methods of data collection that exist in quantitative and qualitative research , and the various issues around data in qualitative research.

When it comes to defining data, data can be any sort of information that people use to better understand the world around them. Having this information allows us to robustly draw and verify conclusions, as opposed to relying on blind guesses or thought exercises.

Necessity of data collection skills

Collecting data is critical to the fundamental objective of research as a vehicle to organize knowledge. While this may seem intuitive, it's important to acknowledge that researchers must be as skilled in data collection as they are in data analysis .

Collecting the right data

Rather than just collecting as much data as possible, it's important to collect data that is relevant for answering your research question . Imagine a simple research question: what factors do people consider when buying a car? It would not be possible to ask every living person about their car purchases. Even if it was possible, not everyone drives a car, so asking non-drivers seems unproductive. As a result, the researcher conducting a study to devise data reports and marketing strategies has to take a sample of the relevant data to ensure reliable analysis and findings.

Data collection examples

In the broadest terms, any sort of data gathering contributes to the research process. In any work of science, researchers cannot make empirical conclusions without relying on some body of data to make rational judgments.

Various examples of data collection in the social sciences include:

- responses to a survey about product satisfaction

- interviews with students about their career goals

- reactions to an experimental vitamin supplement regimen

- observations of workplace interactions and practices

- focus group data about customer behavior

Data science and scholarly research have almost limitless possibilities to collect data, and the primary requirement is that the dataset should be relevant to the research question and clearly defined. Researchers thus need to rule out any irrelevant data so that they can develop new theory or key findings.

Types of data

Researchers can collect data themselves (primary data) or use third-party data (secondary data). The data collection considerations regarding which type of data to work with have a direct relationship to your research question and objectives.

Primary data

Original research relies on first-party data, or primary data that the researcher collects themselves for their own analysis. When you are collecting information in a primary study yourself, you are more likely to gain the high quality you require.

Because the researcher is most aware of the inquiry they want to conduct and has tailored the research process to their inquiry, first-party data collection has the greatest potential for congruence between the data collected and the potential to generate relevant insights.

Ethnographic research , for example, relies on first-party data collection since a description of a culture or a group of people is contextualized through a comprehensive understanding of the researcher and their relative positioning to that culture.

Secondary data

Researchers can also use publicly available secondary data that other researchers have generated to analyze following a different approach and thus produce new insights. Online databases and literature reviews are good examples where researchers can find existing data to conduct research on a previously unexplored inquiry. However, it is important to consider data accuracy or relevance when using third-party data, given that the researcher can only conduct limited quality control of data that has already been collected.

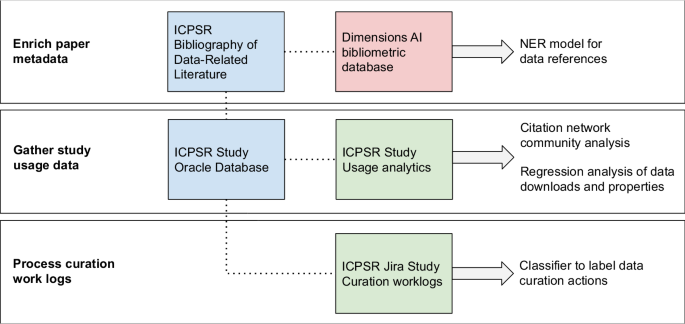

A relatively new consideration in data collection and data analysis has been the advent of big data, where data scientists employ automated processes to collect data in large amounts.

The advantage of collecting data at scale is that a thorough analysis of a greater scope of data can potentially generate more generalizable findings. Nonetheless, this is a daunting task because it is time-consuming and arduous. Moreover, it requires skilled data scientists to sift through large data sets to filter out irrelevant data and generate useful insights. On the other hand, it is important for qualitative researchers to carefully consider their needs for data breadth versus depth: Qualitative studies typically rely on a relatively small number of participants but very detailed data is collected for each participant, because understanding the specific context and individual interpretations or experiences is often of central importance. When using big data, this depth of data is usually replaced with a greater breadth of data that includes a much greater number of participants. Researchers need to consider their need for depth or breadth to decide which data collection method is best suited to answer their research question.

Data science made easy with ATLAS.ti

ATLAS.ti handles all research projects big and small. See how with a free trial.

Different data collection procedures for gathering data exist depending on the research inquiry you want to conduct. Let's explore the common data collection methods in quantitative and qualitative research.

Quantitative data collection methods

Quantitative methods are used to collect numerical or quantifiable data. These can then be processed statistically to test hypotheses and gain insights. Quantitative data gathering is typically aimed at measuring a particular phenomenon (e.g., the amount of awareness a brand has in the market, the efficacy of a particular diet, etc.) in order to test hypotheses (e.g., social media marketing campaigns increase brand awareness, eating more fruits and vegetables leads to better physical performance, etc.).

Some qualitative methods of research can contribute to quantitative data collection and analysis. Online surveys and questionnaires with multiple-choice questions can produce structured data ready to be analyzed. A survey platform like Qualtrics, for example, aggregates survey responses in a spreadsheet to allow for numerical or frequency analysis.

Qualitative data collection methods

Analyzing qualitative data is important for describing a phenomenon (e.g., the requirements for good teaching practices), which may lead to the creation of propositions or the development of a theory. Behavioral data, transactional data, and data from social media monitoring are examples of different forms of data that can be collected qualitatively.

Consideration of tools or equipment for collecting data is also important. Primary data collection methods in observational research , for example, employ tools such as audio and video recorders , notebooks for writing field notes , and cameras for taking photographs. As long as the products of such tools can be analyzed, those products can be incorporated into a study's data collection.

Employing multiple data collection methods

Moreover, qualitative researchers seldom rely on one data collection method alone. Ethnographic researchers , in particular, can incorporate direct observation , interviews , focus group sessions , and document collection in their data collection process to produce the most contextualized data for their research. Mixed methods research employs multiple data collection methods, including qualitative and quantitative data, along with multiple tools to study a phenomenon from as many different angles as possible.

New forms of data collection

External data sources such as social media data and big data have also gained contemporary focus as social trends change and new research questions emerge. This has prompted the creation of novel data collection methods in research.

Ultimately, there are countless data collection instruments used for qualitative methods, but the key objective is to be able to produce relevant data that can be systematically analyzed. As a result, researchers can analyze audio, video, images, and other formats beyond text. As our world is continuously changing, for example, with the growing prominence of generative artificial intelligence and social media, researchers will undoubtedly bring forth new inquiries that require continuous innovation and adaptation with data collection methods.

Collecting data for qualitative research is a complex process that often comes with unique challenges. This section discusses some of the common obstacles that researchers may encounter during data collection and offers strategies to navigate these issues.

Access to participants

Obtaining access to research participants can be a significant challenge. This might be due to geographical distance, time constraints, or reluctance from potential participants. To address this, researchers need to clearly communicate the purpose of their study, ensure confidentiality, and be flexible with their scheduling.

Cultural and language barriers

Researchers may face cultural and language barriers, particularly in cross-cultural research. These barriers can affect communication and understanding between the researcher and the participant. Employing translators, cultural mediators, or learning the local language can be beneficial in overcoming these barriers.

Non-responsive or uncooperative participants

At times, researchers might encounter participants who are unwilling or unable to provide the required information. In these situations, rapport-building is crucial. The researcher should aim to build trust, create a comfortable environment for the participant, and reassure them about the confidentiality of their responses.

Time constraints

Qualitative research can be time-consuming, particularly when involving interviews or focus groups that require coordination of multiple schedules, transcription , and in-depth analysis . Adequate planning and organization can help mitigate this challenge.

Bias in data collection

Bias in data collection can occur when the researcher's preconceptions or the participant's desire to present themselves favorably affect the data. Strategies for mitigating bias include reflexivity , triangulation, and member checking .

Handling sensitive topics

Research involving sensitive topics can be challenging for both the researcher and the participant. Ensuring a safe and supportive environment , practicing empathetic listening, and providing resources for emotional support can help navigate these sensitive issues.

Collecting data in qualitative research can be a very rewarding but challenging experience. However, with careful planning, ethical conduct, and a flexible approach, researchers can effectively navigate these obstacles and collect robust, meaningful data.

Considerations when collecting data

Research relies on empiricism and credibility at all stages of a research inquiry. As a result, there are various data collection problems and issues that researchers need to keep in mind.

Data quality issues

Your analysis may depend on capturing the fine-grained details that some data collection tools may miss. In that case, you should carefully consider data quality issues regarding the precision of your data collection. For example, think about a picture taken with a smartphone camera and a picture taken with a professional camera. If you need high-resolution photos, it would make sense to rely on a professional camera that can provide adequate data quality.

Quantitative data collection often relies on precise data collection tools to evaluate outcomes, but researchers collecting qualitative data should also be concerned with quality assurance. For example, suppose a study involving direct observation requires multiple observers in different contexts. In that case, researchers should take care to ensure that all observers can gather data in a similar fashion to ensure that all data can be analyzed in the same way.

Data quality is a crucial consideration when gathering information. Even if the researcher has chosen an appropriate method for data collection, is the data that they collect useful and detailed enough to provide the necessary analysis to answer the given research inquiry?

One example where data quality is consequential in qualitative data collection includes interviews and focus groups. Recordings may lose some of the finer details of social interaction, such as pauses, thinking words, or utterances that aren't loud enough for the microphone to pick up.

Suppose you are conducting an interview for a study where such details are relevant to your analysis. In that case, you should consider employing tools that collect sufficiently rich data to record these aspects of interaction.

Data integrity

The possibility of inaccurate data has the potential to confound the data analysis process, as drawing conclusions or making decisions becomes difficult, if not impossible, with low-quality data. Failure to establish the integrity of data collection can cast doubt on the findings of a given study. Accurate data collection is just one aspect researchers should consider to protect data integrity. After that, it is a matter of preserving the data after data collection. How is the data stored? Who has access to the collected data? To what extent can the data be changed between data collection and research dissemination?

Data integrity is an issue of research ethics as well as research credibility . The researcher needs to establish that the data presented for research dissemination is an accurate representation of the phenomenon under study.

Imagine if a photograph of wildlife becomes so aged that the color becomes distorted over time. Suppose the findings depend on describing the colors of a particular animal or plant. In that case, then not preserving the integrity of the data presents a serious threat to the credibility of the research and the researcher. In addition, when transcribing an interview or focus group, it is important to take care that participants’ words are accurately transcribed to avoid unintentionally changing the data.

Transparency

As explored earlier, researchers rely on both intuition and data to make interpretations about the world. As a result, researchers have an obligation to explain how they collected data and describe their data so that audiences can also understand it. Establishing research transparency also allows other researchers to examine a study and determine if they find it credible and how they can continue to build off it.

To address this need, research papers typically have a methodology section, which includes descriptions of the tools employed for data collection and the breadth and depth of the data that is collected for the study. It is important to transparently convey every aspect of the data collection and analysis , which might involve providing a sample of the questions participants were asked, demographic information about participants, or proof of compliance with ethical standards, to name a few examples.

Subjectivity

How to gather data is also a key concern, especially in social sciences where people's perspectives represent the collected data, and these perspectives can vastly differ.