Along with Stanford news and stories, show me:

- Student information

- Faculty/Staff information

We want to provide announcements, events, leadership messages and resources that are relevant to you. Your selection is stored in a browser cookie which you can remove at any time using “Clear all personalization” below.

A pandemic that disproportionately affected communities of color, roadblocks that obstructed efforts to expand the franchise and protect voting discrimination, a growing movement to push anti-racist curricula out of schools – events over the past year have only underscored how prevalent systemic racism and bias is in America today.

What can be done to dismantle centuries of discrimination in the U.S.? How can a more equitable society be achieved? What makes racism such a complicated problem to solve? Black History Month is a time marked for honoring and reflecting on the experience of Black Americans, and it is also an opportunity to reexamine our nation’s deeply embedded racial problems and the possible solutions that could help build a more equitable society.

Stanford scholars are tackling these issues head-on in their research from the perspectives of history, education, law and other disciplines. For example, historian Clayborne Carson is working to preserve and promote the legacy of Martin Luther King Jr. and religious studies scholar Lerone A. Martin has joined Stanford to continue expanding access and opportunities to learn from King’s teachings; sociologist Matthew Clair is examining how the criminal justice system can end a vicious cycle involving the disparate treatment of Black men; and education scholar Subini Ancy Annamma is studying ways to make education more equitable for historically marginalized students.

Learn more about these efforts and other projects examining racism and discrimination in areas like health and medicine, technology and the workplace below.

Update: Jan. 27, 2023: This story was originally published on Feb. 16, 2021, and has been updated on a number of occasions to include new content.

Understanding the impact of racism; advancing justice

One of the hardest elements of advancing racial justice is helping everyone understand the ways in which they are involved in a system or structure that perpetuates racism, according to Stanford legal scholar Ralph Richard Banks.

“The starting point for the center is the recognition that racial inequality and division have long been the fault line of American society. Thus, addressing racial inequity is essential to sustaining our nation, and furthering its democratic aspirations,” said Banks , the Jackson Eli Reynolds Professor of Law at Stanford Law School and co-founder of the Stanford Center for Racial Justice .

This sentiment was echoed by Stanford researcher Rebecca Hetey . One of the obstacles in solving inequality is people’s attitudes towards it, Hetey said. “One of the barriers of reducing inequality is how some people justify and rationalize it.”

How people talk about race and stereotypes matters. Here is some of that scholarship.

For Black Americans, COVID-19 is quickly reversing crucial economic gains

Research co-authored by SIEPR’s Peter Klenow and Chad Jones measures the welfare gap between Black and white Americans and provides a way to analyze policies to narrow the divide.

How an ‘impact mindset’ unites activists of different races

A new study finds that people’s involvement with Black Lives Matter stems from an impulse that goes beyond identity.

For democracy to work, racial inequalities must be addressed

The Stanford Center for Racial Justice is taking a hard look at the policies perpetuating systemic racism in America today and asking how we can imagine a more equitable society.

The psychological toll of George Floyd’s murder

As the nation mourned the death of George Floyd, more Black Americans than white Americans felt angry or sad – a finding that reveals the racial disparities of grief.

Seven factors contributing to American racism

Of the seven factors the researchers identified, perhaps the most insidious is passivism or passive racism, which includes an apathy toward systems of racial advantage or denial that those systems even exist.

Scholars reflect on Black history

Humanities and social sciences scholars reflect on “Black history as American history” and its impact on their personal and professional lives.

The history of Black History Month

It's February, so many teachers and schools are taking time to celebrate Black History Month. According to Stanford historian Michael Hines, there are still misunderstandings and misconceptions about the past, present, and future of the celebration.

Numbers about inequality don’t speak for themselves

In a new research paper, Stanford scholars Rebecca Hetey and Jennifer Eberhardt propose new ways to talk about racial disparities that exist across society, from education to health care and criminal justice systems.

Changing how people perceive problems

Drawing on an extensive body of research, Stanford psychologist Gregory Walton lays out a roadmap to positively influence the way people think about themselves and the world around them. These changes could improve society, too.

Welfare opposition linked to threats of racial standing

Research co-authored by sociologist Robb Willer finds that when white Americans perceive threats to their status as the dominant demographic group, their resentment of minorities increases. This resentment leads to opposing welfare programs they believe will mainly benefit minority groups.

Conversations about race between Black and white friends can feel risky, but are valuable

New research about how friends approach talking about their race-related experiences with each other reveals concerns but also the potential that these conversations have to strengthen relationships and further intergroup learning.

Defusing racial bias

Research shows why understanding the source of discrimination matters.

Many white parents aren’t having ‘the talk’ about race with their kids

After George Floyd’s murder, Black parents talked about race and racism with their kids more. White parents did not and were more likely to give their kids colorblind messages.

Stereotyping makes people more likely to act badly

Even slight cues, like reading a negative stereotype about your race or gender, can have an impact.

Why white people downplay their individual racial privileges

Research shows that white Americans, when faced with evidence of racial privilege, deny that they have benefited personally.

Clayborne Carson: Looking back at a legacy

Stanford historian Clayborne Carson reflects on a career dedicated to studying and preserving the legacy of civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr.

How race influences, amplifies backlash against outspoken women

When women break gender norms, the most negative reactions may come from people of the same race.

Examining disparities in education

Scholar Subini Ancy Annamma is studying ways to make education more equitable for historically marginalized students. Annamma’s research examines how schools contribute to the criminalization of Black youths by creating a culture of punishment that penalizes Black children more harshly than their white peers for the same behavior. Her work shows that youth of color are more likely to be closely watched, over-represented in special education, and reported to and arrested by police.

“These are all ways in which schools criminalize Black youth,” she said. “Day after day, these things start to sediment.”

That’s why Annamma has identified opportunities for teachers and administrators to intervene in these unfair practices. Below is some of that research, from Annamma and others.

New ‘Segregation Index’ shows American schools remain highly segregated by race, ethnicity, and economic status

Researchers at Stanford and USC developed a new tool to track neighborhood and school segregation in the U.S.

New evidence shows that school poverty shapes racial achievement gaps

Racial segregation leads to growing achievement gaps – but it does so entirely through differences in school poverty, according to new research from education Professor Sean Reardon, who is launching a new tool to help educators, parents and policymakers examine education trends by race and poverty level nationwide.

School closures intensify gentrification in Black neighborhoods nationwide

An analysis of census and school closure data finds that shuttering schools increases gentrification – but only in predominantly Black communities.

Ninth-grade ethnic studies helped students for years, Stanford researchers find

A new study shows that students assigned to an ethnic studies course had longer-term improvements in attendance and graduation rates.

Teaching about racism

Stanford sociologist Matthew Snipp discusses ways to educate students about race and ethnic relations in America.

Stanford scholar uncovers an early activist’s fight to get Black history into schools

In a new book, Assistant Professor Michael Hines chronicles the efforts of a Chicago schoolteacher in the 1930s who wanted to remedy the portrayal of Black history in textbooks of the time.

How disability intersects with race

Professor Alfredo J. Artiles discusses the complexities in creating inclusive policies for students with disabilities.

Access to program for black male students lowered dropout rates

New research led by Stanford education professor Thomas S. Dee provides the first evidence of effectiveness for a district-wide initiative targeted at black male high school students.

How school systems make criminals of Black youth

Stanford education professor Subini Ancy Annamma talks about the role schools play in creating a culture of punishment against Black students.

Reducing racial disparities in school discipline

Stanford psychologists find that brief exercises early in middle school can improve students’ relationships with their teachers, increase their sense of belonging and reduce teachers’ reports of discipline issues among black and Latino boys.

Science lessons through a different lens

In his new book, Science in the City, Stanford education professor Bryan A. Brown helps bridge the gap between students’ culture and the science classroom.

Teachers more likely to label black students as troublemakers, Stanford research shows

Stanford psychologists Jennifer Eberhardt and Jason Okonofua experimentally examined the psychological processes involved when teachers discipline black students more harshly than white students.

Why we need Black teachers

Travis Bristol, MA '04, talks about what it takes for schools to hire and retain teachers of color.

Understanding racism in the criminal justice system

Research has shown that time and time again, inequality is embedded into all facets of the criminal justice system. From being arrested to being charged, convicted and sentenced, people of color – particularly Black men – are disproportionately targeted by the police.

“So many reforms are needed: police accountability, judicial intervention, reducing prosecutorial power and increasing resources for public defenders are places we can start,” said sociologist Matthew Clair . “But beyond piecemeal reforms, we need to continue having critical conversations about transformation and the role of the courts in bringing about the abolition of police and prisons.”

Clair is one of several Stanford scholars who have examined the intersection of race and the criminal process and offered solutions to end the vicious cycle of racism. Here is some of that work.

Police Facebook posts disproportionately highlight crimes involving Black suspects, study finds

Researchers examined crime-related posts from 14,000 Facebook pages maintained by U.S. law enforcement agencies and found that Facebook users are exposed to posts that overrepresent Black suspects by 25% relative to local arrest rates.

Supporting students involved in the justice system

New data show that a one-page letter asking a teacher to support a youth as they navigate the difficult transition from juvenile detention back to school can reduce the likelihood that the student re-offends.

Race and mass criminalization in the U.S.

Stanford sociologist discusses how race and class inequalities are embedded in the American criminal legal system.

New Stanford research lab explores incarcerated students’ educational paths

Associate Professor Subini Annamma examines the policies and practices that push marginalized students out of school and into prisons.

Derek Chauvin verdict important, but much remains to be done

Stanford scholars Hakeem Jefferson, Robert Weisberg and Matthew Clair weigh in on the Derek Chauvin verdict, emphasizing that while the outcome is important, much work remains to be done to bring about long-lasting justice.

A ‘veil of darkness’ reduces racial bias in traffic stops

After analyzing 95 million traffic stop records, filed by officers with 21 state patrol agencies and 35 municipal police forces from 2011 to 2018, researchers concluded that “police stops and search decisions suffer from persistent racial bias.”

Stanford big data study finds racial disparities in Oakland, Calif., police behavior, offers solutions

Analyzing thousands of data points, the researchers found racial disparities in how Oakland officers treated African Americans on routine traffic and pedestrian stops. They suggest 50 measures to improve police-community relations.

Race and the death penalty

As questions about racial bias in the criminal justice system dominate the headlines, research by Stanford law Professor John J. Donohue III offers insight into one of the most fraught areas: the death penalty.

Diagnosing disparities in health, medicine

The COVID-19 pandemic has disproportionately impacted communities of color and has highlighted the health disparities between Black Americans, whites and other demographic groups.

As Iris Gibbs , professor of radiation oncology and associate dean of MD program admissions, pointed out at an event sponsored by Stanford Medicine: “We need more sustained attention and real action towards eliminating health inequities, educating our entire community and going beyond ‘allyship,’ because that one fizzles out. We really do need people who are truly there all the way.”

Below is some of that research as well as solutions that can address some of the disparities in the American healthcare system.

Stanford researchers testing ways to improve clinical trial diversity

The American Heart Association has provided funding to two Stanford Medicine professors to develop ways to diversify enrollment in heart disease clinical trials.

Striking inequalities in maternal and infant health

Research by SIEPR’s Petra Persson and Maya Rossin-Slater finds wealthy Black mothers and infants in the U.S. fare worse than the poorest white mothers and infants.

More racial diversity among physicians would lead to better health among black men

A clinical trial in Oakland by Stanford researchers found that black men are more likely to seek out preventive care after being seen by black doctors compared to non-black doctors.

A better measuring stick: Algorithmic approach to pain diagnosis could eliminate racial bias

Traditional approaches to pain management don’t treat all patients the same. AI could level the playing field.

5 questions: Alice Popejoy on race, ethnicity and ancestry in science

Alice Popejoy, a postdoctoral scholar who studies biomedical data sciences, speaks to the role – and pitfalls – of race, ethnicity and ancestry in research.

Stanford Medicine community calls for action against racial injustice, inequities

The event at Stanford provided a venue for health care workers and students to express their feelings about violence against African Americans and to voice their demands for change.

Racial disparity remains in heart-transplant mortality rates, Stanford study finds

African-American heart transplant patients have had persistently higher mortality rates than white patients, but exactly why still remains a mystery.

Finding the COVID-19 Victims that Big Data Misses

Widely used virus tracking data undercounts older people and people of color. Scholars propose a solution to this demographic bias.

Studying how racial stressors affect mental health

Farzana Saleem, an assistant professor at Stanford Graduate School of Education, is interested in the way Black youth and other young people of color navigate adolescence—and the racial stressors that can make the journey harder.

Infants’ race influences quality of hospital care in California

Disparities exist in how babies of different racial and ethnic origins are treated in California’s neonatal intensive care units, but this could be changed, say Stanford researchers.

Immigrants don’t move state-to-state in search of health benefits

When states expand public health insurance to include low-income, legal immigrants, it does not lead to out-of-state immigrants moving in search of benefits.

Excess mortality rates early in pandemic highest among Blacks

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has been starkly uneven across race, ethnicity and geography, according to a new study led by SHP's Maria Polyakova.

Decoding bias in media, technology

Driving Artificial Intelligence are machine learning algorithms, sets of rules that tell a computer how to solve a problem, perform a task and in some cases, predict an outcome. These predictive models are based on massive datasets to recognize certain patterns, which according to communication scholar Angele Christin , sometimes come flawed with human bias .

“Technology changes things, but perhaps not always as much as we think,” Christin said. “Social context matters a lot in shaping the actual effects of the technological tools. […] So, it’s important to understand that connection between humans and machines.”

Below is some of that research, as well as other ways discrimination unfolds across technology, in the media, and ways to counteract it.

IRS disproportionately audits Black taxpayers

A Stanford collaboration with the Department of the Treasury yields the first direct evidence of differences in audit rates by race.

Automated speech recognition less accurate for blacks

The disparity likely occurs because such technologies are based on machine learning systems that rely heavily on databases of English as spoken by white Americans.

New algorithm trains AI to avoid bad behaviors

Robots, self-driving cars and other intelligent machines could become better-behaved thanks to a new way to help machine learning designers build AI applications with safeguards against specific, undesirable outcomes such as racial and gender bias.

Stanford scholar analyzes responses to algorithms in journalism, criminal justice

In a recent study, assistant professor of communication Angèle Christin finds a gap between intended and actual uses of algorithmic tools in journalism and criminal justice fields.

Move responsibly and think about things

In the course CS 181: Computers, Ethics and Public Policy , Stanford students become computer programmers, policymakers and philosophers to examine the ethical and social impacts of technological innovation.

Homicide victims from Black and Hispanic neighborhoods devalued

Social scientists found that homicide victims killed in Chicago’s predominantly Black and Hispanic neighborhoods received less news coverage than those killed in mostly white neighborhoods.

Algorithms reveal changes in stereotypes

New Stanford research shows that, over the past century, linguistic changes in gender and ethnic stereotypes correlated with major social movements and demographic changes in the U.S. Census data.

AI Index Diversity Report: An Unmoving Needle

Stanford HAI’s 2021 AI Index reveals stalled progress in diversifying AI and a scarcity of the data needed to fix it.

Identifying discrimination in the workplace and economy

From who moves forward in the hiring process to who receives funding from venture capitalists, research has revealed how Blacks and other minority groups are discriminated against in the workplace and economy-at-large.

“There is not one silver bullet here that you can walk away with. Hiring and retention with respect to employee diversity are complex problems,” said Adina Sterling , associate professor of organizational behavior at the Graduate School of Business (GSB).

Sterling has offered a few places where employers can expand employee diversity at their companies. For example, she suggests hiring managers track data about their recruitment methods and the pools that result from those efforts, as well as examining who they ultimately hire.

Here is some of that insight.

How To: Use a Scorecard to Evaluate People More Fairly

A written framework is an easy way to hold everyone to the same standard.

Archiving Black histories of Silicon Valley

A new collection at Stanford Libraries will highlight Black Americans who helped transform California’s Silicon Valley region into a hub for innovation, ideas.

Race influences professional investors’ judgments

In their evaluations of high-performing venture capital funds, professional investors rate white-led teams more favorably than they do black-led teams with identical credentials, a new Stanford study led by Jennifer L. Eberhardt finds.

Who moves forward in the hiring process?

People whose employment histories include part-time, temporary help agency or mismatched work can face challenges during the hiring process, according to new research by Stanford sociologist David Pedulla.

How emotions may result in hiring, workplace bias

Stanford study suggests that the emotions American employers are looking for in job candidates may not match up with emotions valued by jobseekers from some cultural backgrounds – potentially leading to hiring bias.

Do VCs really favor white male founders?

A field experiment used fake emails to measure gender and racial bias among startup investors.

Can you spot diversity? (Probably not)

New research shows a “spillover effect” that might be clouding your judgment.

Can job referrals improve employee diversity?

New research looks at how referrals impact promotions of minorities and women.

- My Reading List

- Account Settings

- Newsletters & alerts

- Gift subscriptions

- Accessibility for screenreader

Resources to understand America’s long history of injustice and inequality

Protest and activism

Income inequality

Policing and criminal justice

Arrests of minors aged 10 to 17

Per 100,000 people

Adult incarceration rate

Source: U.S. Department of Justice

Arrests of minors

aged 10 to 17

Incarceration rate

of adult population

We noticed you’re blocking ads!

Find anything you save across the site in your account

How Do We Change America?

By Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor

The national uprising in response to the brutal murder of George Floyd , a forty-six-year-old black man, by four Minneapolis police officers, has been met with shock, elation, concern, fear, and gestures of solidarity. Its sheer scale has been surprising. Across the United States, in cities large and small, streets have filled with young, multiracial crowds who have had enough. In the largest uprisings since the Los Angeles rebellion of 1992, anger and bitterness at racist and unrestrained police violence, abuse, and even murder have finally spilled over in every corner of the United States.

More than seventeen thousand National Guard troops have been deployed—more soldiers than are currently occupying Iraq and Afghanistan—to put down the rebellion. More than ten thousand people have been arrested ; more than twelve people, mostly African-American men, have been killed. Curfews were imposed in at least thirty cities, including New York, Chicago, Philadelphia, Omaha, and Sioux City. Solidarity demonstrations have been organized from Accra to Dublin—in Berlin, Paris, London, and beyond. And, most surprisingly, two weeks after Floyd’s death, the protests have not ended. Last Saturday saw the largest protests so far, as tens of thousands of people gathered on the National Mall and marched down the streets of Brooklyn and Philadelphia.

The relentless fury and pace of rebellion has forced states to shrug off their stumbling efforts to subdue the novel coronavirus that continues to sicken thousands in the United States. State leaders have been much more adept in calling up the National Guard and coördinating police actions to confront marchers than they were in any of their efforts to curtail the virus. In a show of both cowardice and authoritarianism, Donald Trump threatened to call up the U.S. military to occupy American cities. “Crisis” does not begin to describe the political maelstrom that has been unleashed.

There have been planned demonstrations, and there have also been violent and explosive outbursts that can only be described as a revolt or an uprising. Riots are not only the voice of the unheard, as Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., famously said ; they are the rowdy entry of the oppressed into the political realm. They become a stage of political theatre where joy, revulsion, sadness, anger, and excitement clash wildly in a cathartic dance. They are a festival of the oppressed.

For once in their lives, many of the participants can be seen, heard, and felt in public. People are pulled from the margins into a powerful force that can no longer be ignored, beaten, or easily discarded. Offering the first tastes of real freedom, when the police are for once afraid of the crowd, the riot can be destructive, unruly, violent, and unpredictable. But within that contradictory tangle emerge demands and aspirations for a society different from the one in which we live. Not only do the rebels express their own dismay but they also showcase our entire social dilemma. As King said , of the uprisings in the late nineteen-sixties, “I am not sad that Black Americans are rebelling; this was not only inevitable but eminently desirable. Without this magnificent ferment among Negroes, the old evasions and procrastinations would have continued indefinitely. Black men have slammed the door shut on a past of deadening passivity. Except for the Reconstruction years, they have never in their long history on American soil struggled with such creativity and courage for their freedom. These are our bright years of emergence; though they are painful ones, they cannot be avoided.”

King continued, “The black revolution is much more than a struggle for the rights of Negroes. It is forcing America to face all its interrelated flaws—racism, poverty, militarism, and materialism. It is exposing the evils that are rooted deeply in the whole structure of our society. It reveals systemic rather than superficial flaws and suggests that radical reconstruction of society itself is the real issue to be faced.”

By now, it should be clear what the demands of young black people are: an end to racism, police abuse, and violence; and the right to be free of the economic coercion of poverty and inequality.

The question is: How do we change this country? It’s not a new question; for African-Americans, it’s a question as old as the nation itself. A large part of the reason that rebels swell the streets with clenched fists and expressive eyes is the refusal or inability of this society to engage that question in a satisfying way. Instead, those asking the question are patronized with sweet-sounding speeches, made with alliterative apologia, often interspersed with recitations about the meaning of America, and ultimately in defense of the status quo. There is a palpable poverty of intellect, a lack of imagination, and a banality of ideas pervading mainstream politics today. Old and failed propositions are recycled, but proclaimed as new, reviving cynicism and dismay.

Take the recent comments of the former President Barack Obama. On Twitter, Obama counselled that “Real change requires protest to highlight a problem, and politics to implement practical solutions and laws.” He continued to say that “there are specific evidence-based reforms that would build trust, save lives, and lead to a decrease in crime, too,” including the policy proposals of his Task Force on 21st Century Policing, convened in 2015. Such a simple, plain-stated plan fails to answer the most basic question: Why do police reforms continue to fail? African-Americans have been demonstrating against police abuse and violence since the Chicago riots of 1919. The first riot directly in response to police abuse occurred in 1935, in Harlem. In 1951, a contingent of African-American activists, armed with a petition titled “We Charge Genocide,” tried to persuade the United Nations to decry the U.S. government’s murder of black people. Their petition read :

Once the classic method of lynching was the rope. Now it is the policeman’s bullet. To many an American the police are the government, certainly its most visible representative. We submit that the evidence suggests that the killing of Negroes has become police policy in the United States and that police policy is the most practical expression of government policy.

It has been the lack of response, and a lack of “practical solutions” to beatings, harassment, and murder, that has led people into the streets, to challenge the typical dominance of police in black communities.

Many have compared the national revolt today to the urban rebellions of the nineteen-sixties, but it is more immediately shaped by the Los Angeles rebellion of 1992 and the protests it unleashed across the country. The 1992 uprising grew out of the frustrated mix of growing poverty, violence generated by the drug war, and widening unemployment. By 1992, official black unemployment had reached a high of fourteen per cent, more than double that of white Americans. In South Central Los Angeles, where the uprising took hold, more than half of people over the age of sixteen were unemployed or out of the labor force. A combination of police brutality and state-sanctioned accommodation of violence against a black child ultimately lit the fuse.

We remember that, on March 3, 1991, Rodney King, a black motorist, was beaten by four L.A. police officers by the side of the freeway. But it is also true that, two weeks later, a fifteen-year-old black girl, Latasha Harlins, was shot in the head by a convenience-store owner, Soon Ja Du, after a confrontation about whether Harlins intended to pay for a bottle of orange juice. A jury found Du guilty of manslaughter and recommended the maximum sentence, but the judge in the case disagreed and sentenced Du to five years probation, community service, and a five-hundred-dollar fine. The L.A. rebellion began on April 29, 1992, when the officers who had beaten King were unexpectedly acquitted, but it was also fuelled by the fact that, a week earlier, an appeals court had upheld the lesser sentence for Du.

In the immediate aftermath of the verdict, a multiracial throng of protesters gathered outside the headquarters of the Los Angeles Police Department, chanting, “No justice, no peace!” and “Guilty!” As people began to gather in South Central, the police arrived and attempted to arrest them, before realizing that they were overmatched and deserting the scene. At one point, the L.A. Times recounted, at Seventy-first and Normandie streets, two hundred people “lined the intersection, many with raised fists. Chunks of asphalt and concrete were thrown at cars. Some yelled, ‘It’s a black thing.’ Others shouted, ‘This is for Rodney King.’ ” By the end of the day, more than three hundred fires burned across the city, at police headquarters and city hall, downtown, and in the white neighborhoods of Fairfax and Westwood. In Atlanta, hundreds of black young people chanted “Rodney King” as they smashed through store windows in the business district of the city. In Northern California, seven hundred students from Berkeley High School walked out of their classes in protest. In a short span of five days, the L.A. uprising emerged as the largest and most destructive riot in U.S. history, with sixty-three dead, a billion dollars in property damage, nearly twenty-four hundred injured, and seventeen thousand arrested. President George H. W. Bush invoked the Insurrection Act , to mobilize units from the U.S. Marines and Army to put down the rebellion. A black man named Terry Adams spoke to the L.A. Times , and captured the motivation and the mood. “Our people are in pain,” he said. “Why should we draw a line against violence? The judicial system doesn’t.”

The uprising in L.A. shared with the rebellions of the nineteen-sixties an igniting spark of police abuse, widespread violence, and the fury of the rebels. But, in the nineteen-sixties, the flush economy and the still-intact notion of the social contract meant that President Lyndon B. Johnson could attempt to drown the civil-rights movement and the Black Power radicalization with enormous social spending and government-program expansion, including the passage of the Housing and Urban Development Act of 1968, which produced the first government-backed, low-income homeownership opportunities directed at African-Americans.

By the late nineteen-eighties and early nineties, the economy was in recession and the social contract had been ripped to shreds. The rebellions of the nineteen-sixties and the enormous social spending intended to bring them under control were wielded by the right to generate a backlash against the expanded welfare state. Political conservatives argued that the market, not government intervention, could create efficiencies and innovation in the delivery of public services. This rhetoric was coupled with virulent racist characterizations of African-Americans, who relied disproportionately on welfare programs. Ronald Reagan mastered the art of color-blind racism in the post-civil-rights era with his invocations of “welfare queens.” Not only did these distortions pave the way for undermining the welfare state, they reinforced racist delusions about the state of black America that legitimized deprivation and marginalization.

The Los Angeles uprising not only exposed the police state that African-Americans were subjected to but also uncovered the hollowed-out core of the U.S. economy after the supposed economic genius of the Reagan Revolution. The rebellions of the nineteen-sixties were disparaged as race riots because they were confined almost exclusively to segregated black communities. The L.A. rebellion spread rapidly across the city: fifty-one per cent of those arrested were Latino, and only thirty-six per cent were black. A smaller number of whites were also arrested. Public officials had used racism as a crowbar to dismantle the welfare state, but the effects were felt across the board. Though African-Americans were disproportionate recipients of welfare, whites made up the majority, and they suffered, too, when cuts were imposed. As Willie Brown, who was then the speaker of the California Assembly, wrote, in the San Francisco Examiner , days after the uprising, “For the first time in American history, many of the demonstrations and much of the violence and crime, especially the looting, was multiracial—blacks, whites, Hispanics, and Asians were all involved.” Though typically segregated from each other socially, each group found ways to express their overlapping grievances in the furious revolt against the L.A.P.D.

The period after the L.A. rebellion didn’t usher in new initiatives to improve the quality of the lives of people who had revolted. To the contrary, the Bush White House spokesman Marlin Fitzwater blamed the uprising on the social-welfare programs of previous administrations, saying, “We believe that many of the root problems that have resulted in inner-city difficulties were started in the sixties and seventies and that they have failed.” The nineteen-nineties became a moment of convergence for the political right and the Democratic Party, as the Democrats cemented their turn toward a similar agenda of harsh budget cuts to social programs and an insistence that African-American hardship was the result of non-normative family structures. In May, 1992, Bill Clinton interrupted his normal campaign activities to travel to South Central Los Angeles, where he offered his analysis of what had gone so wrong. People were looting, he said, “because they are not part of the system at all anymore. They do not share our values, and their children are growing up in a culture alien from ours, without family, without neighborhood, without church, without support.”

Democrats responded to the 1992 Los Angeles rebellion by pushing the country further down the road of punishment and retribution in its criminal-justice system. Joe Biden , the current Democratic Presidential front-runner, emerged from the fire last time brandishing a new “crime bill” that pledged to put a hundred thousand more police on the street, called for mandatory prison sentences for certain crimes, increased funding for policing and prisons, and expanded the use of the death penalty. The Democrats’ new emphasis on law and order was coupled with a relentless assault on the right to welfare assistance. By 1996, Clinton had followed through on his pledge to “end welfare as we know it.” Biden supported the legislation, arguing that “the culture of welfare must be replaced with the culture of work. The culture of dependence must be replaced with the culture of self-sufficiency and personal responsibility. And the culture of permanence must no longer be a way of life.”

The 1994 crime bill was a pillar in the phenomenon of mass incarceration and public tolerance for aggressive policing and punishment directed at African-American neighborhoods. It helped to build the world that young black people are rebelling against today. But the unyielding assaults on welfare and food stamps have also marked this latest revolt. These cuts are a large part of the reason that the coronavirus pandemic has landed so hard in the U.S., particularly in black America . These are the reasons that we do not have a viable safety net in this country, including food stamps and cash payments during hard times. The weakness of the U.S. social-welfare state has deep roots, but it was irreversibly torn when Democrats were at the helm.

The current climate can hardly be reduced to the political lessons of the past, but the legacy of the nineties dominates the political thinking of elected officials today. When Republicans insist on tying work requirements to food stamps in the midst of a pandemic, with unemployment at more than thirteen per cent, they are conjuring the punitive spirit of the policies shaped by Clinton, Biden, and other leading Democrats throughout the nineteen-nineties. So, though Biden desperately wants us to believe that he is a harbinger of change, his long record of public service says otherwise. He has claimed that Barack Obama’s selection of him as his running mate was a kind of absolution for Biden’s dealings in the Democrats’ race-baiting politics of the nineteen-nineties. But, from the excesses of the criminal-justice system and the absence of a welfare state to the inequality rooted in an unbridled, rapacious market economy, Biden has shaped much of the world that this generation has inherited and is revolting against.

More important, the ideas honed in the nineteen-eighties and nineties continue to beat at the center of Biden’s political agenda. His campaign advisers include Larry Summers, who, as Clinton’s Treasury Secretary, was an enthusiastic supporter of deregulation, and, as Obama’s chief economic adviser during the recession, endorsed the Wall Street bailout while allowing millions of Americans to default on their mortgages. They also include Rahm Emanuel, whose tenure as the mayor of Chicago ended in disgrace, when it was revealed that his administration covered up the police murder of the seventeen-year-old Laquan McDonald, who was shot sixteen times by a white police officer. But Emanuel’s damage to Chicago ran much deeper than his defense of a particularly racist and abusive police force. He also carried out the largest single closure of public schools in U.S. history—nearly fifty in one fell swoop, in 2013. After two terms, he left the city in the same broken condition he found it, with forty-five per cent of young black men in Chicago both out of school and unemployed.

This points to the importance of expanding our national discussion about what ails the country, beyond the racism and brutality of the police. We must also discuss the conditions of economic inequality that, when they intersect with racial and gender discrimination, disadvantage African-Americans while also making them vulnerable to police violence. Otherwise, we risk reducing racism to the outrageous and intentional acts of depraved individuals, while downplaying the cumulative impact of public policies and private-sector discrimination that, regardless of personal intent, have crippled the vitality of African-American life.

When the focus narrows to the barbarism of the act that stole George Floyd’s life, it allows for the likes of the former President George W. Bush to enter the conversation and claim to deplore racism. Bush wrote, in an open letter on the Floyd killing, that “it remains a shocking failure that many African Americans, especially young African American men, are harassed and threatened in their own country.” This would be laughable if George W. Bush were not the grim reaper who hid beneath a shroud he described as “compassionate conservatism.” As the governor of Texas, he oversaw a rampant and racist death-penalty system, personally signing off on the execution of a hundred and fifty-two incarcerated people, a disproportionate number of them African-American. As President, Bush oversaw the stunningly incompetent government response to Hurricane Katrina, which contributed to the deaths of nearly two thousand people and displaced tens of thousands of African-American residents of New Orleans. That Bush is able to sanctimoniously enter into a discussion about American racism while ignoring his own role in its perpetuation and sustenance speaks to the superficiality of the conversation. Although many are becoming comfortable spurting out phrases like “systemic racism,” the solutions proposed remain mired in the system that is being critiqued. The result is that the roots of oppression and inequality that constitute what many activists refer to as “racial capitalism” are left in place.

Joe Biden, in a recent, rare public appearance, came to Philadelphia to describe the leadership necessary to emerge from this current moment. His speech sounded as if it could have been made at any time in the last twenty years. He promulgated a proposal to end choke holds—even though many police departments have done that already, at least on paper. The New York Police Department is one of them, though this did not prevent Daniel Pantaleo from choking Eric Garner to death, nor did it cause Pantaleo to be sent to jail for it. Biden called for accountability, oversight, and community policing. These proposals for curbing racist policing are as old as the first declarations for reform that came out of the Kerner Commission, in 1967. Then, too, as the nation’s cities combusted into a frenzy of uprisings, federal reformers enumerated changes to police policy such as these, and, more than fifty years later, the police remain impervious to reform and often in arrogant refusal to heel. It is simply astounding that Joe Biden has not a single meaningful or new idea to offer about controlling the police.

Barack Obama, in an essay that he posted on Medium, describes voting as the road to making “real change,” although he also writes that “if we want to bring about real change, then the choice isn’t between protest and politics. We have to do both. We have to mobilize to raise awareness, and we have to organize and cast our ballots to make sure that we elect candidates who will act on reform.” Obama has developed a tendency to intervene in political debates as if he were a curious and detached observer, rather than a former officeholder of the most powerful position in the world. The Black Lives Matter movement bloomed during the final years of Obama’s Presidency. At each stage of its development, Obama seemed unable to curb the police abuses that were fuelling its development. It is easy to get bogged down in the intricacies of federalism and the constraints on executive power, given that police abuse is such a local issue. But Obama did, after all, convene a national task force aimed at providing guidance and leadership on police accountability, and we can consider its effectiveness from the standpoint of today.

Obama’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing delivered sixty-three recommendations, including ending “racial profiling” and extending “community policing” efforts. It called for “better training” and revamping the entire criminal-justice system. But they were no more than suggestions; there was no mechanism to make the country’s eighteen thousand different law-enforcement agencies comply. The Task Force’s interim report was released on March 2, 2015. That month , police across the country killed another hundred and thirteen people, thirty more than in the previous month. On April 4th, Walter Scott, an unarmed black man running away from a white cop, Michael Slager, in North Charleston, South Carolina, was shot five times from behind. Eight days later, Freddie Gray was picked up by Baltimore police, placed in a van with no restraints, and driven recklessly around the city. When he emerged from the van, his spine was eighty-per-cent severed at his neck. He died seven days later. Baltimore exploded in rage. And Baltimore was not like Ferguson, Missouri, which was run by a white political establishment and patrolled by a white police force. From Mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake to a multiracial police force, Baltimore was a black-led city.

Even as the wanton violence of law enforcement has come into sharper focus in the last five years, there has been almost no consequence in terms of municipal budget allocations. Police continue to absorb absurd portions of local operating budgets—even in departments that are sources of embarrassment and abuse lawsuits. In Los Angeles, with its homelessness crisis and out-of-control rents, the police absorb an astounding fifty-three per cent of the city’s general fund. Chicago, a city with a notoriously corrupt and abusive police force, spent thirty-nine per cent of its budget on police. Philadelphia’s operating budget needed to be recalibrated because of the collapse of tax collections due to the coronavirus pandemic; the only agency that will not suffer any budget cuts is the police department. While public schools, affordable housing, violence-prevention programming, and the police-oversight board prepare for three hundred and seventy million dollars in budget cuts, the Philadelphia Police Department, which already garners sixteen per cent of the city’s funds, is slated to receive a twenty-three-million-dollar increase.

Throughout the Obama and Trump Administrations, the failures to rein in racist policing practices have been compounded by the economic stagnation in African-American communities, measured by stalled rates of homeownership and a widening racial wealth gap. Are these failures of governance and politics all Obama’s fault? Of course not, but, when you run on big promises of change and end up overseeing a brutal status quo, people draw dim conclusions from the experiment. For many poor and working-class African-Americans, who still have enormous pride in the first black President and his spouse, Michelle Obama, the conclusion is that electing the nation’s first black President was never going to change America. One might even interpret the failures of the Obama Administration as some of the small kindling that has set the nation ablaze.

We cannot insist on “real change” in the United States by continuing to use the same methods, arguments, and failed political strategies that have brought us to this moment. We cannot allow the current momentum to be stalled by a narrow discussion about reforming the police. In Obama’s essay, he wrote, “I saw an elderly black woman being interviewed today in tears because the only grocery store in her neighborhood had been trashed. If history is any guide, that store may take years to come back. So let’s not excuse violence, or rationalize it, or participate in it.” If we are thinking of these problems in big and broad strokes, or in a systemic way, we might ask: Why is there only a single grocery store in this woman’s neighborhood? That might lead to a discussion about the history of residential segregation in that neighborhood, or job discrimination or under-resourced schools in the area, which might, in turn, provide deeper insights into an alienation that is so profound in its intensity that it compels people to fight with the intensity of a riot to demand things change. And this is where the trouble actually begins. Our society cannot end these conditions without massive expenditure.

In 1968, King, in the weeks before he was assassinated, said, “In a sense, I guess you could say, we are engaged in the class struggle.” He was speaking to the costs of the programs that would be necessary to lift black people out of poverty and inequality, which were, in and of themselves, emblems of racist subjugation. Ending segregation in the South, then, was cheap compared with the huge costs necessary to end the kinds of discrimination that kept blacks locked out of the advantages of U.S. society, from well-paying jobs to well-resourced schools, good housing, and a comfortable retirement. The price of the ticket is quite steep, but, if we are to have a real conversation about how we change America, it must begin with an honest assessment of the scope of the deprivation involved. Racist and corrupt policing is the tip of the iceberg.

We have to make space for new politics, new ideas, new formations, and new people. The election of Biden may stop the misery of another Trump term, but it won’t stop the underlying issues that have brought about more than a hundred thousand COVID -19 deaths or continuous protests against police abuse and violence. Will the federal government intervene to stop the looming crisis of evictions that will disproportionately impact black women? Will it use its power and authority to punish police, and to empty prisons and jails, which not only bring about social death but are now also sites of rampant COVID -19 infection ? Will it end the war on food stamps and allow African-Americans and other residents of this country to eat in the midst of the worst economic crisis since the Great Depression? Will it finance the health-care needs of tens of millions of African-Americans who have become susceptible to the worst effects of the coronavirus, and are dying as a result? Will it provide the resources to depleted public schools, allowing black children the opportunity to learn in peace? Will it redistribute the hundreds of billions of dollars necessary to rebuild devastated working-class communities? Will there be free day care and transportation?

If we are serious about ending racism and fundamentally changing the United States, we must begin with a real and serious assessment of the problems. We diminish the task by continuing to call upon the agents and actors who fuelled the crisis when they had opportunities to help solve it. But, more importantly, the quest to transform this country cannot be limited to challenging its brutal police alone. It must conquer the logic that finances police and jails at the expense of public schools and hospitals. Police should not be armed with expensive artillery intended to maim and murder civilians while nurses tie garbage sacks around their bodies and reuse masks in a futile effort to keep the coronavirus at bay.

We have the resources to remake the United States, but it will have to come at the expense of the plutocrats and the plunderers, and therein lies the three-hundred-year-old conundrum: America’s professed values of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, continually undone by the reality of debt, despair, and the human degradation of racism and inequality.

The unfolding revolt in the U.S. today holds the real promise to change this country. While it reflects the history and failures of past endeavors to confront racism and police brutality, these protests cannot be reduced to them. Unlike the uprising in Los Angeles, where Korean businesses were targeted and some white bystanders were beaten, or the rebellions of the nineteen-sixties, which were confined to black neighborhoods, today’s protests are stunning in their racial solidarity. The whitest states in the country, including Maine and Idaho, have had protests involving thousands of people. And it’s not just students or activists; the demands for an end to this racist violence have mobilized a broad range of ordinary people who are fed up.

The protests are building on the incredible groundwork of a previous iteration of the Black Lives Matter movement. Today, young white people are compelled to protest not only because of their anxieties about the instability of this country and their compromised futures in it but also because of a revulsion against white supremacy and the rot of racism. Their outlooks have been shaped during the past several years by the anti-racist politics of the B.L.M. movement, which move beyond seeing racism as interpersonal or attitudinal, to understanding that it is deeply rooted in the country’s institutions and organizations.

This may account, in part, for the firm political foundation that this round of struggle has begun upon. It explains why activists and organizers have so quickly been able to gather support for demands to defund police, and in some cases introduce ideas about ending policing altogether. They have been able to quickly link bloated police budgets to the attacks on other aspects of the public sector, and to the limits on cities’ abilities to attend to the social crises that have been exposed by the COVID -19 pandemic. They have built upon the vivid memories of previous failures, and refuse to submit to empty or rhetoric-driven calls for change. This is evidence again of how struggles build upon one another and are not just recycled events from the past.

Race, Policing, and Black Lives Matter Protests

- The death of George Floyd , in context.

- The civil-rights lawyer Bryan Stevenson examines the frustration and despair behind the protests.

- Who, David Remnick asks, is the true agitator behind the racial unrest ?

- A sociologist examines the so-called pillars of whiteness that prevent white Americans from confronting racism.

- The Black Lives Matter co-founder Opal Tometi on what it would mean to defund police departments , and what comes next.

- The quest to transform the United States cannot be limited to challenging its brutal police.

By signing up, you agree to our User Agreement and Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement . This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

By Isaac Chotiner

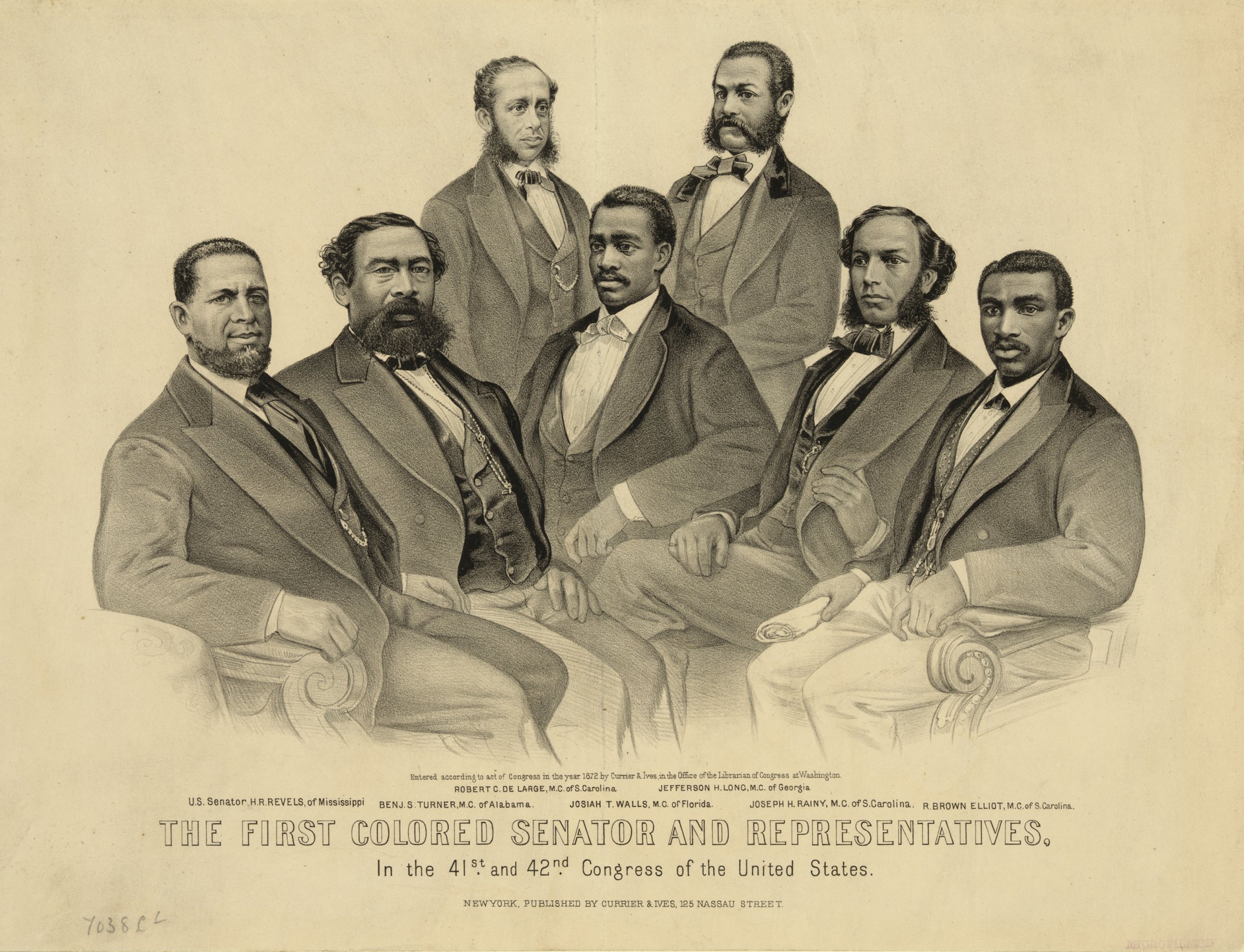

How Reconstruction Still Shapes American Racism

D uring an interview with Chris Rock for my PBS series African American Lives 2 , we traced the ancestry of several well-known African Americans. When I told Rock that his great-great-grandfather Julius Caesar Tingman had served in the U.S. Colored Troops during the Civil War — enrolling on March 7, 1865, a little more than a month after the Confederates evacuated from Charleston, S.C. — he was brought to tears. I explained that seven years later, while still a young man in his mid-20s, this same ancestor was elected to the South Carolina house of representatives as part of that state’s Reconstruction government. Rock was flabbergasted, his pride in his ancestor rivaled only by gratitude that Julius’ story had been revealed at last. “It’s sad that all this stuff was kind of buried and that I went through a whole childhood and most of my adulthood not knowing,” Rock said. “How in the world could I not know this?”

I realized then that even descendants of black heroes of Reconstruction had lost the memory of their ancestors’ heroic achievements. I have been interested in Reconstruction and its tragic aftermath since I was an undergraduate at Yale University, and I have been teaching works by black authors from the second half of the 19th century for decades. But the urgent need for a broader public conversation about the period first struck me only in that conversation with Rock.

Reconstruction, the period in American history that followed the Civil War, was an era filled with great hope and expectations, but it proved far too short to ensure a successful transition from bondage to free labor for the almost 4 million black human beings who’d been born into slavery in the U.S. During Reconstruction, the U.S. government maintained an active presence in the former Confederate states to protect the rights of the newly freed slaves and to help them, however incompletely, on the path to becoming full citizens. A little more than a decade later, the era came to an end when the contested presidential election of 1876 was resolved by trading the electoral votes of South Carolina, Louisiana and Florida for the removal of federal troops from the last Southern statehouses.

Today, many of us know precious little about what happened during those years. But, regardless of its brevity, Reconstruction remains one of the most pivotal eras in the history of race relations in American history — and probably the most misunderstood.

Reconstruction was fundamentally about who got to be an American citizen. It was in that period that the Constitution was amended to establish birthright citizenship through the 14th Amendment, which also guaranteed equality before the law regardless of race. The 15th Amendment, ratified in 1870, barred racial discrimination in voting, thus securing the ballot for black men nationwide. As Eric Foner, the leading historian of the era, puts it, “The issues central to Reconstruction — citizenship, voting rights, terrorist violence, the relationship between economic and political democracy — continue to roil our society and politics today, making an understanding of Reconstruction even more vital.” A key lesson of Reconstruction, and of its violent, racist rollback, is, Foner continues, “that achievements thought permanent can be overturned and rights can never be taken for granted.”

Another lesson this era of our history teaches us is that, even when stripped of their rights by courts, legislatures and revised state constitutions, African Americans never surrendered to white supremacy. Resistance, too, is their legacy.

By 1877 , in a climate of economic crisis, the “cost” of protecting the freedoms of African Americans became a price the American government was no longer willing to pay. The long rollback began in earnest: the period of retrenchment, voter suppression, Jim Crow segregation and quasi re-enslavement that was called by white Southerners, ironically, “Redemption.” As a worried Frederick Douglass, sensing the storm clouds gathering on the horizon, put it in a speech at the Republican National Convention on June 14, 1876: “You say you have emancipated us. You have; and I thank you for it. You say you have enfranchised us; and I thank you for it. But what is your emancipation? — What is your enfranchisement? What does it all amount to if the black man, after having been made free by the letter of your law, is unable to exercise that freedom, and, after having been freed from the slaveholder’s lash, he is to be subject to the slaveholder’s shotgun?”

What confounds me is how much longer the rollback of Reconstruction was than Reconstruction itself, how dogged was the determination of the “Redeemed South” to obliterate any trace of the gains made by freed people. In South Carolina, for example, the state university that had been integrated during Reconstruction (indeed, Harvard’s first black college graduate, Richard T. Greener, was a professor there) was swiftly shut down and reopened three years later for whites only. That color line remained in place there until 1963.

In addition to their moves to strip African Americans of their voting rights, “Redeemer” governments across the South slashed government investments in infrastructure and social programs across the board, including those for the region’s first state-funded public-school systems, a product of Reconstruction. In doing so, they re-empowered a private sphere dominated by the white planter class. A new wave of state constitutional conventions followed, starting with Mississippi in 1890. These effectively undermined the Reconstruction Amendments, especially the right of black men to vote, in each of the former Confederate states by 1908. To take just one example: whereas in Louisiana, 130,000 black men were registered to vote before the state instituted its new constitution in 1898, by 1904 that number had been reduced to 1,342.

And at what the historian Rayford W. Logan dubbed the “nadir” of American race relations—the time of political, economic, social and legal hardening around segregation — widespread violence, disenfranchisement and lynching coincided with a hardening of racist concepts of “race.”

This painfully long period following Reconstruction saw the explosion of white-supremacist ideology across an array of media and through an extraordinary variety of forms, all designed to warp the mind toward white-supremacist beliefs. Minstrelsy and racist visual imagery were weapons in the battle over the status of African Americans in postslavery America, and some continue to be manufactured to this day.

The process of dehumanization triggered a resistance movement. Among a rising generation of the black elite, this resistance was represented after 1895 through the concept of “The New Negro,” a counter to the avalanche of racist images of black people that proliferated throughout Gilded Age American society in advertisements, posters and postcards, helped along by technological innovations that enabled the cheap mass production of multicolored prints. Not surprisingly, racist images of black people — characterized by exaggerated physical features, the blackest of skin tones, the whitest of eyes and the reddest of lips — were a favorite subject of these multicolored prints during the rollback of Reconstruction and the birth of Jim Crow segregation in the 1890s.

We can think of the New Negro as Black America’s first superhero, locked in combat against the white-supremacist fiction of African Americans as “Sambos,” by nature lazy, mentally inferior, licentious and, beneath the surface, lurking sexual predators. The New Negro would undergo several transformations within the race between the mid-1890s and the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s, but, in its essence, it was a trope — summarized by one writer in 1928 as a continuously evolving “mythological figure” — that would be drawn upon and revised over three decades by black leaders in the country’s first social-media war: the New Negro vs. Sambo.

The concept would prove to be quite volatile. Supposedly New Negroes could be supplanted by even “newer” Negroes. For example, Booker T. Washington, the conservative, accommodationist educator, would be hailed as the first New Negro in 1895, only to be dethroned exactly a decade later on the cover of the Voice of the Negro magazine by his nemesis, W.E.B. Du Bois, the Harvard-trained historian. Du Bois had globalized his version of the New Negro in a landmark photography exhibition at the 1900 Paris Exposition and then, three years later, in his monumental work, The Souls of Black Folk , mounted a devastating attack on Washington’s philosophy of race relations as dangerously complicitous with Jim Crow segregation and, especially, black male disenfranchisement. Du Bois, a founder of the militant Niagara Movement in 1905, would co-found the NAACP in 1909. And while Douglass had already seen the potential of photography to present an authentic face of black America, and thus to counteract the onslaught of negative stereotypes pervading American society, the children of Reconstruction were the ones who picked up the torch after his death in 1895.

This new generation experimented with a range of artistic mediums to carve out a space for a New Negro who would lead the race — and the country — into the rising century, one whose racial attitudes would be more modern and cosmopolitan than those of the previous century, marred by slavery and Civil War. When D.W. Griffith released his racist Lost Cause fantasy film The Birth of a Nation in 1915, New Negro activists responded not only with protest but also with support for African American artists like the pioneering independent producer and director Oscar Micheaux, whose reels of silent films exposed the horrors of white supremacy while advancing a fuller, more humanistic take on black life.

Their pushback against Redemption took many forms. Denied the ballot box, African American women and men organized political associations, churches, schools and social clubs, both to nurture their own culture and to speak out as forcefully as they could against the suffocating oppression unfolding around them. Though brutalized by the shockingly extensive practices of lynching and rape, reinforced by terrorism and vigilante violence, they exposed the crimes and hypocrisy of white supremacy in their own newspapers and magazines, and in marches and political rallies. But no weapon was drawn upon more frequently than images of the New Negro and what the historian Evelyn Higginbotham calls “the politics of respectability.”

Assaulted by the degrading, mass-produced imagery of the Lost Cause, its romanticization of the Old South and stereotypes of “Sambo” and the “Old Negro,” they avidly counterpunched with their own images of modern women and men, which they widely disseminated in journalism, photography, literature and the arts. Drawing on the tradition of agitation epitomized by the black Reconstruction Congressmen, such as John Mercer Langston, and former abolitionists, such as the inimitable Douglass, the children of Reconstruction would lay the foundation for the civil rights revolution to come in the 20th century.

But what also seems clear to me today is that it was in that period that white-supremacist ideology, especially as it was transmuted into powerful new forms of media, poisoned the American imagination in ways that have long outlasted its origin. You might say that anti-black racism once helped fuel an economic system, and that black crude was pumped and freighted around the world. Now, more than a century and a half since the end of slavery in the U.S., it drifts like a toxic oil slick as the supertanker lists into the sea.

When Dylann Roof murdered the Reverend Clementa Pinckney and the eight other innocents in Mother Emanuel AME Church in Charleston, S.C. , on June 17, 2015, he didn’t need to have read any of this history; it had, unfortunately, long become part of our country’s cultural DNA and, it seems, imprinted on his own. It is important that we both celebrate the triumphs of African Americans following the Civil War and explain how the forces of white supremacy did their best to undermine those triumphs—then and in all the years since, through to the present.

Gates is the Alphonse Fletcher university professor and director of the Hutchins Center for African and African American Research at Harvard University. His PBS series on Reconstruction airs April 9 and April 16. This essay is adapted from his new book, Stony the Road: Reconstruction, White Supremacy, and the Rise of Jim Crow . Published by Penguin Press, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC . Copyright © 2019 by Henry Louis Gates, Jr.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Javier Milei’s Radical Plan to Transform Argentina

- The New Face of Doctor Who

- How Private Donors Shape Birth-Control Choices

- What Happens if Trump Is Convicted ? Your Questions, Answered

- The Deadly Digital Frontiers at the Border

- Scientists Are Finding Out Just How Toxic Your Stuff Is

- The 31 Most Anticipated Movies of Summer 2024

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at [email protected]

Dismantling racism today starts by understanding slavery’s ‘horrific’ past

Facebook Twitter Print Email

Education is the “most powerful weapon” in the world’s arsenal to combat the brutal legacy of racism playing out today, the UN chief said on Monday, as the General Assembly met to mark the International Day of Remembrance of the Victims of Slavery and the Transatlantic Slave Trade.

“It is incumbent on us to fight slavery’s legacy of racism ,” the UN Secretary-General António Guterres said. “The most powerful weapon in our arsenal is education, the theme of this year’s commemoration.”

“It is crucial to invest in quality education. In a time where racism still affects our laws, systems & the descendants of its victims, education is the key to countering injustice and moving forward” @taylorcassidyj @UN #UNGA commemorative meeting on #RememberSlavery Day. https://t.co/x1mW0rGBH2 Remember Slavery rememberslavery March 27, 2023

Observed on 25 March, the international day commemorates the victims of one of history’s most horrific crimes against humanity that was legalized for more than 400 years, well into the 19th century , resulting in the forced deportation of over 15 million men, women, and children.

Long shadow of slavery

“The scars of slavery are still visible in persistent disparities in wealth, income, health, education, and opportunity,” he said, also pointing to the current resurgence of white supremacist hate .

Just as the slave trade underwrote the wealth and prosperity of the colonizers, it devastated the African continent , thwarting its development for centuries, he said.

“The long shadow of slavery still looms over the lives of people of African descent who carry with them the transgenerational trauma and who continue to confront marginalization, exclusion, and bigotry ,” he said.

Teach histories of ‘righteous defiance’

Governments everywhere should introduce lessons into school curricula on the causes, manifestations, and far-reaching consequences of the transatlantic slave trade, he said.

“We must learn and teach the horrific history of slavery, and we must learn and teach the history of Africa and the African diaspora , whose people have enriched societies wherever they went, and excelled in every field of human endeavour,” the Secretary-General said.

He pointed to examples of righteous resistance, resilience, and defiance as Queen Nanny of the Maroons, in Jamaica, Queen Ana Nzinga of Ndongo in Angola, freedom fighter Sojourner Truth , who was born into slavery, and Toussaint Louverture of Saint-Domingue, who transformed a rebellion into a revolutionary movement and is known today as the “Father of Haiti”.

“By teaching the history of slavery, we help to guard against humanity’s most vicious impulses , and by honouring the victims of slavery, we restore some measure of dignity to those who were so mercilessly stripped of it,” he said.

Dismantle the foundations

General Assembly President Csaba Kőrösi said that while the transatlantic slave trade is over, the foundations on which it stood have not been fully dismantled, he said, adding that racism, including anti-black racism and discrimination, are still present in societies .

“Many Africans and people of African descent continue to feel that they are fighting an uphill battle for the recognition of an assault on their rights that was neither repaired nor rectified,” he said.

This is why this Day of Remembrance is so important, because it creates a space to reflect on a dark and shameful chapter of the world’s shared history, he said.

“History, the facts of which should not be distorted, must serve as a lesson for all of us,” he said. “Through education , we can confute any revisionism with undisputable facts, raise awareness of the dangers caused by misconceptions of supremacy past or present, and ensure that no one will ever experience the hell lived by the 15 million we commemorate today.”

“Through education, the painful stories of racism can be transformed into a future of peace ,” he said.

‘A more hopeful future’

During the event, Brazilian philosopher and journalist, Djamila Ribeiro, delivered the keynote address, explaining how she has been using the power of education to fight discrimination against Afro-Brazilians. Her work is reflected in her bestselling book ‘Little Anti-Racist Manual’ and her influential Instagram account, which has more than one million followers.

“It’s important to remember that Brazil was the last in the Americas to abolish slavery,” she said. “ History needs to be remembered so that, in the present, we can overcome and transform its consequences and build a more hopeful future .”

Also addressing the world body was American university student Taylor Cassidy, recognized as one of TikTok’s 2020 Top 10 Voices of Change, empowering her 2.2 million followers with uplifting videos related to Black history.

“It is crucial to invest in quality education ,” she said. “At a time when racism still affects our laws, systems and descendants of its victims, education is the key to countering injustice and moving forward .”

How the UN helps to remember the victims of slavery and the transatlantic slave trade:

- The UN Department of Global Communications Outreach Programme on the Transatlantic Slave Trade and Slavery will host a panel discussion at UN Headquarters on Thursday to highlight efforts by museums to include the voices of people of African descent and deal with the colonial past.The featured speaker will be Bryan Stevenson, Founder and Executive Director of the Equal Justice Initiative – a non-profit working to end mass incarceration in the United States.

- A free interactive exhibition Slavery: Ten True Stories of Dutch Colonial Slavery , brought to the UN by the Rijksmuseum of the Netherlands, opened in February at the UN Headquarters’ Visitors’ Lobby, on display until 30 March.

- The UN Remember Slavery Programme has, since its inception in 2007, established a global network of partners, including from educational institutions and civil society, and developed resources and initiatives to educate the public about this dark chapter of history and promote action against racism.

- The UN Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization ( UNESCO ) Slave Route Project focuses on breaking the silence surrounding the history of slavery, promoting the contributions of people of African descent to the general progress of humanity, and questioning the social, cultural and economic inequalities inherited from this tragedy.

- The Ark of Return , by Haitian-American architect Rodney Leon, is a permanent memorial located at UN Headquarters, and open to all visitors.

- International Day of Remembrance of the Victims of Slavery and the Transatlantic Slave Trade

Black Progress: How far we’ve come, and how far we have to go

Subscribe to governance weekly, abigail thernstrom and at abigail thernstrom senior fellow, manhattan institute stephan thernstrom st stephan thernstrom.

March 1, 1998

- 16 min read

Let’s start with a few contrasting numbers.

60 and 2.2. In 1940, 60 percent of employed black women worked as domestic servants; today the number is down to 2.2 percent, while 60 percent hold white- collar jobs.

44 and 1. In 1958, 44 percent of whites said they would move if a black family became their next door neighbor; today the figure is 1 percent.

18 and 86. In 1964, the year the great Civil Rights Act was passed, only 18 percent of whites claimed to have a friend who was black; today 86 percent say they do, while 87 percent of blacks assert they have white friends.

Progress is the largely suppressed story of race and race relations over the past half-century. And thus it’s news that more than 40 percent of African Americans now consider themselves members of the middle class. Forty-two percent own their own homes, a figure that rises to 75 percent if we look just at black married couples. Black two-parent families earn only 13 percent less than those who are white. Almost a third of the black population lives in suburbia.

Because these are facts the media seldom report, the black underclass continues to define black America in the view of much of the public. Many assume blacks live in ghettos, often in high-rise public housing projects. Crime and the welfare check are seen as their main source of income. The stereotype crosses racial lines. Blacks are even more prone than whites to exaggerate the extent to which African Americans are trapped in inner-city poverty. In a 1991 Gallup poll, about one-fifth of all whites, but almost half of black respondents, said that at least three out of four African Americans were impoverished urban residents. And yet, in reality, blacks who consider themselves to be middle class outnumber those with incomes below the poverty line by a wide margin.

A Fifty-Year March out of Poverty