Homosexuality from Religious and Philosophical Perspectives Essay

Introduction, christian perspective and homosexuality, human flourishing and homosexuality, works cited.

People have different views on homosexuality and the moral acceptability of the open manifestation of the homosexual lifestyle. This topic is controversial, and every side has a foregrounded argument based on their ethical values. For example, the proponents of open homosexuality insist that this lifestyle allows them to feel happy and contribute to human flourishing, which means there is nothing wrong with this practice. When the person hide their sexual inclinations and deny the part of their nature, they cannot be satisfied with their lives, which has a destructive impact on them and their surrounding. The opponents of open homosexuality insist that it is a sinful practice that violates the divine laws and leads to the spread of the wrong perception of relationships. It is possible to assume that people’s perspectives on homosexuality have deep cultural and religious roots, which makes the attempts to change their opinions on this issue ineffective.

From the Christian perspective, a homosexual lifestyle is against God’s Moral Law. It explains the believers’ detest of the legalization of homosexual marriages and open manifestations of such relationships. The religious point of view clearly defines homosexuality as the sin of sodomy punished by God. It is written in Romans 1:26-27: “God gave them over to shameful lusts. Even their women exchanged natural sexual relations for unnatural ones. In the same way, the men also abandoned natural relations with women and were inflamed with lust for one another. Men committed shameful acts with other men and received in themselves the due penalty for their error” ( New International Version, Romans 1:26-27). Therefore, the Holy Scripture condemns homosexuality.

The only acceptable variant of relationships is the heterosexual married couple with intimate contact only for conception and subsequent birth to children. A faithful Christian who finds people of the same sex attractive should regard it as an evil temptation and oppose it; otherwise, they sin (Yuan 55). At the same time, there is the opinion that the Bible does not directly condemn homosexuality. This perspective is the cultural belief shared by most Christian communities (Dailey vi). Even when people insist that homosexuality is the inborn inclination a person does not choose, the Christian perspective supposes that the individual should fight this temptation to achieve holiness or at least not violate God’s laws (Grudem 861). Therefore, the religious point of view on homosexuality is quite clear, and it is not easy to persuade believers to develop the opposite attitude to the homosexual lifestyle.

Not all people agree that opposing homosexual inclinations is a positive thing. The notion of human flourishing is among the significant concepts in the philosophical discourse, and it supposes the pursuit of happiness by people ( Natural Law and Human Flourishing Handout 2-3). The question is whether the opportunity to fulfill all sexual desires leads to joy in the end. Many people who embraced the liberal attitude to sexuality destroyed their lives with these immense opportunities (Budziszewski 2). At the same time, it does not mean that if homosexuals are restricted in their sexual options, they will become happy or be satisfied with the heterosexual family.

It is essential to understand that there are various opinions on homosexuality. People with religious backgrounds disagree with the freedom to choose an intimate partner of the same sex. At the same time, other individuals understand that restricting their desires and changing their nature does not lead to happiness and human flourishing. The only critical issue is that people should decide how to live their lives, and others should be tolerant of their views.

Budziszewski, J. The Natural Laws of Sex. n.p., 2022. Doc file.

Dailey, Timothy J. The Bible, the Church, and Homosexuality. Family Research Council, 2004.

Grudem, W. Christian Ethics. Crossway, 2018.

Holy Bible. New International Version, Zondervan Publishing House, 1984. n.a. Natural Law and Human Flourishing Handout-2. n.p., 2022. Pdf file.

Yuan, Christopher. Holy Sexuality and the Gospel. Crown Publishing Group, 2018.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2024, May 6). Homosexuality from Religious and Philosophical Perspectives. https://ivypanda.com/essays/homosexuality-from-religious-and-philosophical-perspectives/

"Homosexuality from Religious and Philosophical Perspectives." IvyPanda , 6 May 2024, ivypanda.com/essays/homosexuality-from-religious-and-philosophical-perspectives/.

IvyPanda . (2024) 'Homosexuality from Religious and Philosophical Perspectives'. 6 May.

IvyPanda . 2024. "Homosexuality from Religious and Philosophical Perspectives." May 6, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/homosexuality-from-religious-and-philosophical-perspectives/.

1. IvyPanda . "Homosexuality from Religious and Philosophical Perspectives." May 6, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/homosexuality-from-religious-and-philosophical-perspectives/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Homosexuality from Religious and Philosophical Perspectives." May 6, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/homosexuality-from-religious-and-philosophical-perspectives/.

- Homosexuality - Nature or Nurture?

- Should Homosexuality be Legalized?

- Medical and Social Stances on Homosexuality

- LGBTQ+ Discrimination in Professional Settings

- Sexual Orientation Discrimination

- The "LGBTQ+ Inclusion in the Workplace" Article by Ellsworth et al.

- LBGT (Queer)-Specific Mental Health Interventions

- Stigmatization of Kathoeys and Gay Minorities

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Acquisition

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music and Religion

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Society

- Law and Politics

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Ethics

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Games

- Computer Security

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business History

- Business Strategy

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Systems

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Theory

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Politics and Law

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

15 Nature, Morality and Homosexuality

- Published: February 1999

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This chapter argues that Sullivan’s critique of natural law thinking about homosexuality and other questions of sexual morality ignores a distinction that is crucial to understanding this area, namely, the distinction between reasons for action and restraint, and desires , which may, rightly or wrongly, also motivate people. As in Sullivan’s essentially neo-Humean account of value, the basic goods of human nature which provide reasons for action should not be reduced, to desires , even of the deep and more or less stable sort which Sullivan describes as ‘yearnings’. The chapter aims to bring this distinction into focus which will prove that there is no inconsistency in the natural law position.

Signed in as

Institutional accounts.

- Google Scholar Indexing

- GoogleCrawler [DO NOT DELETE]

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

- Add your ORCID iD

Institutional access

Sign in with a library card.

- Sign in with username/password

- Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Sign in through your institution

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Homosexuality and Africa: a philosopher’s perspective

Associate Professor of Philosophy , University of Ghana

Disclosure statement

Martin Odei Ajei does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

University of Ghana provides support as an endorsing partner of The Conversation AFRICA.

View all partners

Most African countries are constitutional democracies that afford extensive rights and freedoms to their citizens, and safeguard their dignity.

It is arbitrary, to say the least, to exclude from these the right to express sexuality or gender identity. But opponents of homosexuality would like to do just that. They often invoke “public interest”, “protection of community” and “morals” to violate the dignity of homosexuals.

Ghana’s current constitution , for example, is widely hailed as an inspiring model of a state’s observance of these freedoms. Yet, on 29 June 2021, The Promotion of Proper Human Sexual Rights and Ghanaian Family Values Bill 2021 was introduced in parliament. It aims to promote “proper human sexual rights and Ghanaian family values, and proscribe the promotion of and advocacy for LGBTQ+ practice”.

The bill’s supporters claim to be motivated by religious and cultural values and ideals. The trend of the discussion of homosexuality in Africa since the 1980s suggests that this view is not uniquely Ghanaian, and that homosexuality nags at the conscience of Africans.

From religious perspectives, homosexuality is problematic because it is sinful, and sinful because it offends against God’s will. Several theologians deny this.

But whether or not religions condemn same-sex relationships, my position is that in many African societies the problem has to do less with sinfulness than with an existential and moral commitment.

To put it more plainly, I believe that many people oppose homosexuality because they feel they have a culturally sanctioned moral commitment to have children. And that commitment stems from the ultimate goal of promoting community welfare. In my view, this is a value which can accommodate same-sex relationships and protect homosexual people.

Culture and nature

I start by accepting that being African is a culturally distinct mode of being. I mean merely that certain values are more prevalent in sub-Saharan Africa than in other geographical locations. I don’t mean that all Africans share one culture. And African cultures evolve all the time. I also start from the position that a person does not choose to be gay.

Being gay in Africa can pose culturally specific problems which the dominant, heterosexual culture may find hard to accept. But I think African culture can also offer a solution to this nonacceptance – a moral theory that allows people to embrace both their sexual being and their cultural being. Being gay and being African need not be seen as a contradiction.

First let’s look at the dominant African culture I’m talking about.

In African societies, an important factor in anti-gay agitation is the moral weight assigned to having children, and emphasis on heterosexual intercourse as a way to achieving this. Procreation ensures continuation of biological heritage, through which the history of society unfolds.

Hence raising children and contributing to a lineage is upheld as a vitally important good for community. In this way, biological reproduction through heterosexual sex becomes a moral responsibility.

To write off the preference for heterosexuality as pre-modern and as biased against homosexuals is insulting and unimaginative. Rather than condemning this preference, it’s more productive to find a way for culture to make room for homosexuality.

Some people describe homosexuality as “unnatural”, “anti-social” or “un-African”. This is not true. Several studies, including one on 50 societies in every region of the continent, decisively support the conclusion that homosexual relationships constitute “a consistent and logical feature of African societies and belief systems.”

The argument that same-sex practice is unnatural because it violates human nature also overlooks the fact that sexuality is a natural feature of human beings. Sexuality is part of what it is to be human. To be human is to be a sexually oriented being.

The tendency in Africa to relegate sexuality to a relatively minor part of human life – to the drive to procreate – tends to treat homosexual expressions as inappropriate. But sexual orientation is central to every person’s entire sense of self, and not just to a small part of it which can be lopped off or put on hold at will.

Accepting the centrality of a person’s sexual orientation to their humanity has significant moral implications which do not square with the existential and moral commitments of African societies I’ve described.

Opponents of homosexuality put more emphasis on the duty to have children, and overlook a deeper value, that of building and sustaining community. They gloss over the role that homosexuals can play in achieving the latter task.

A moderate communitarian solution

My view is that the rights of homosexuals can be better protected by an African moral theory than by the standard constitutional safeguards.

The African moral theory that can achieve this is the Ghanaian philosopher Kwame Gyekye’s “ moderate communitarianism .” This theory holds that an action is intrinsically good if it serves the communal good – namely “ the social conditions that will enable each individual to function satisfactorily in a human society.”

Moderate communitarianism gives equal value to what is good for individuals and what is good for community – as long as individuals and community serve and protect each other’s value and dignity.

From this perspective, homosexual people contribute to the communal good. If what you are is not a matter of choice, and sexuality is part of who you are, then it is morally unjustifiable to consider a homosexual person as incapable of contributing to the common good just because of their sexuality.

Under moderate communitarianism, simply having children is not enough to make you a moral person. It would not be moral to have children and abandon your responsibility to guide these children to acquire virtues that promote communality and human flourishing.

And there are other ways to replenish community. The moderate communitarian acknowledges that heterosexual sex is not the only way to reproduce. For example, there is surrogate parenthood and sperm donation for artificial insemination. Community and human life can also flourish through adopting children in need of parenting or supporting those in need.

A moral person, under this philosophy, is one who cherishes communal relationships and virtues, and whose conduct adds to the communal stock of good. Not bearing children, in itself, cannot count as immoral.

- Christianity

- Peacebuilding

- Cultural bias

- Africa homosexuality

- Same-sex couples

- procreation

Content Coordinator

Lecturer / Senior Lecturer - Marketing

Assistant Editor - 1 year cadetship

Executive Dean, Faculty of Health

Lecturer/Senior Lecturer, Earth System Science (School of Science)

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

- In Gay Marriage Debate, Both Supporters and Opponents See Legal Recognition as ’Inevitable’

- Section 3: Religious Belief and Views of Homosexuality

Table of Contents

- Section 1: Same-Sex Marriage, Civil Unions and Inevitability

- Section 2: Views of Gay Men and Lesbians, Roots of Homosexuality, Personal Contact with Gays

- About the Survey

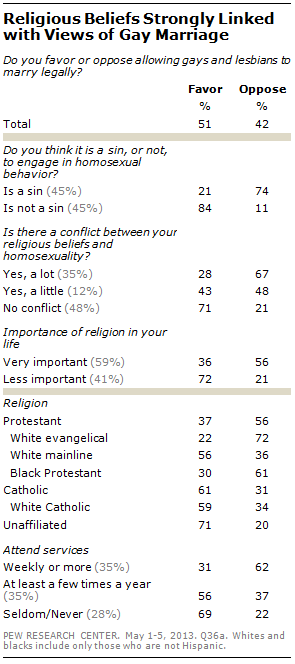

Religious belief continues to be an important factor in opposition to societal acceptance of homosexuality and same-sex marriage.

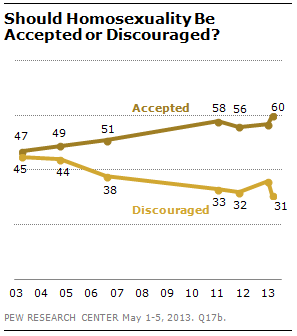

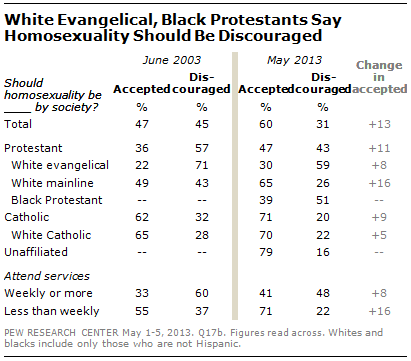

Overall, the share of Americans who say that homosexuality should be accepted by society has increased from 47% to 60% over the past decade, while the percentage saying it should be discouraged has fallen from 45% to 31%.

Yet among those who attend religious services weekly or more, there continues to be slightly more opposition than support for societal acceptance of homosexuality. And when the nearly one-third of Americans who say homosexuality should be discouraged are asked in

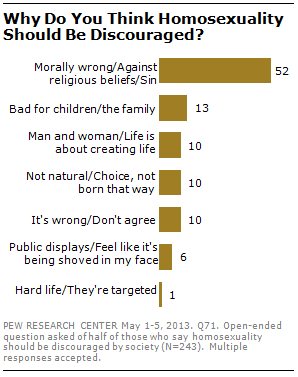

an open-ended question why they feel this way, by far the most common reason –given by 52% – is that homosexuality conflicts with their religious or moral beliefs.

A 62-year-old man said: “ My religious background taught me that this was something that was taboo and not accepted .” A 32-year-old woman described her reasons for why homosexuality should be discouraged this way: “ It clearly states in the Bible that it goes against God’s teachings. ”

Much smaller percentages cite other reasons, such as concerns that homosexuality is bad for the family or bad for children (mentioned by 13%), that a man and woman are needed to create life, that it’s not natural, or “just wrong” (10% each).

Across most demographic subgroups, including most religious groups, the percentage saying homosexuality should be accepted has increased over the past decade. Nonetheless, about half (48%) of those who attend religious services weekly or more

often say homosexuality should be discouraged. Among less frequent attenders, 71% favor societal acceptance of homosexuality.

White evangelical Protestants, by about two-to-one (59% to 30%), think that homosexuality should be discouraged. Among black Protestants, as well, more say homosexuality should be discouraged (51%) than accepted (39%).

By contrast, wide majorities of Catholics (71%) and white mainline Protestants (65%) say homosexuality should be accepted by society. And those without religious affiliation favor societal acceptance of homosexuality by roughly five-to-one (79% to 16%).

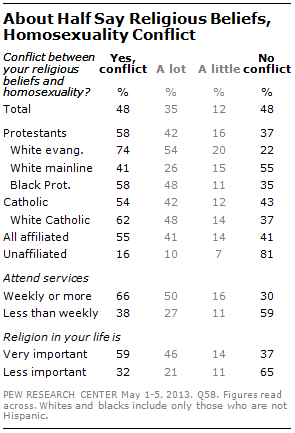

Conflict Between Religious Beliefs and Homosexuality

About half of Americans (48%) say there is a conflict between their religious beliefs and homosexuality, with 35% saying there is a lot of conflict. Another 48% see no conflict between

their religious beliefs and homosexuality.

Among those who attend religious services weekly or more, 66% say homosexuality conflicts with their religious beliefs, with 50% saying there is a great deal of conflict. Most people (59%) who attend religious services less than once a week see no conflict between their beliefs and homosexuality.

Fully 74% of white evangelical Protestants say there is a conflict between homosexuality and their religious beliefs, as do majorities of white Catholics (62%) and black Protestants (58%).

Among white mainline Protestants, however, 41% say there is a conflict between their religious beliefs and homosexuality, while 55% see

no conflict.

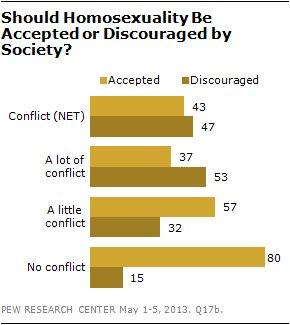

The tension between religious beliefs and homosexuality is closely associated with views about societal acceptance of homosexuality. Among those who see a lot of conflict between their own religious beliefs and homosexuality, a majority (53%) opposes societal acceptance. Those who see a little conflict between religion and homosexuality favor societal acceptance by 57% to 32%. And 80% of those who say there is no conflict between their religious beliefs and homosexuality support societal acceptance.

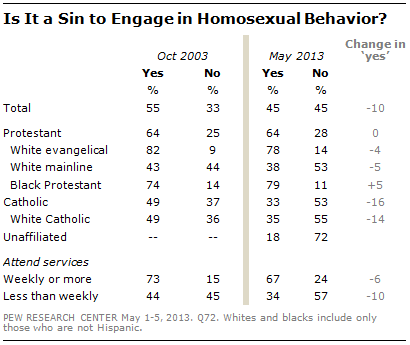

Fewer See Homosexual Behavior as a Sin

The public is divided over whether engaging in homosexual behavior is a sin: 45% say it

is a sin while an identical percentage says it is not. In 2003, a majority (55%) viewed homosexual behavior as was sinful, while 33% disagreed.

Among several religious groups, there has been relatively little change in these opinions over the past decade. Fully 78% of white evangelical Protestants view homosexual behavior as a sin; 82% said this in 2003. About as many black Protestants view homosexuality as a sin today (79%) as did so ten years ago (74%).

However, opinions among Catholics have changed substantially. In 2003, more Catholics said homosexual behavior was a sin than said it was not (49% vs. 37%). Today, a third of Catholics (33%) say it is sin, while 53% disagree.

People who attend religious services weekly or more continue to view homosexual behavior as a sin by a wide margin (67% to 24%). Nearly six-in-ten (57%) of those who attend less often think such behavior is not a sin, while 34% say it is; 10 years ago, opinion was divided (44% sin, 45% not a sin).

Opinions about whether homosexuality is sinful – as well as views about the conflict between religious beliefs and homosexuality – are highly associated with attitudes toward gay marriage.

Nearly three-quarters (74%) of those who say engaging in homosexual behavior is a sin oppose same-sex marriage. An even larger percentage (84%) of those who say it is not sinful favor gay marriage.

The gap in opinions about gay marriage is nearly as wide between those who say there is a lot of conflict between homosexuality and their religious beliefs (67% oppose gay marriage) and those who see no conflict (71% favor gay marriage).

Similarly, those who say religion is very important in their lives are only half as likely to support gay marriage as those who place less importance on religion (36% favor vs. 72% favor).

Sign up for our weekly newsletter

Fresh data delivery Saturday mornings

Sign up for The Briefing

Weekly updates on the world of news & information

- Beliefs & Practices

- National Conditions

- Political Issues

- Same-Sex Marriage

How common is religious fasting in the United States?

8 facts about atheists, spirituality among americans, how people in south and southeast asia view religious diversity and pluralism, religion among asian americans, most popular, report materials.

- Voices : Views of Same-Sex Marriage, Homosexuality

- Graphic : Changing Attitudes on Same Sex Marriage, Gay Friends and Family

- May 2013 Political Survey

1615 L St. NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20036 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Age & Generations

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Economy & Work

- Family & Relationships

- Gender & LGBTQ

- Immigration & Migration

- International Affairs

- Internet & Technology

- Methodological Research

- News Habits & Media

- Non-U.S. Governments

- Other Topics

- Politics & Policy

- Race & Ethnicity

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

Copyright 2024 Pew Research Center

The morality of homosexuality

Affiliation.

- 1 North Carolina State University, Raleigh.

- PMID: 8106742

- DOI: 10.1300/J082v25n04_06

Homosexuality has been considered a form of mental illness, morally wrong and socially deviant. The purpose of this paper is to present both sides of the homosexuality issue from a religious standpoint: opponents of homosexuality versus supporters of homosexuality. It is proposed that how one interprets the morality of homosexuality will depend upon one's level of moral development according to Kohlberg's theory. Ten churches in the Raleigh area of North Carolina completed a questionnaire designed to ascertain the church's position on the issue of homosexuality. Specifically, questions were asked to ascertain the church's level of moral development.

- Christianity

- Homosexuality / psychology*

- Psychosexual Development

- Religion and Psychology*

- Religion and Sex*

- Social Values

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Natural Law Ethics, Homosexuality and Morality

Many, both from within the Roman Catholic Church and outside thereof, have argued that, from the standpoint of natural law ethics, homosexual sexual engagement is morally wrong. This conclusion drawn by supposed natural law ethicists has been a crucial factor contributing towards increased intolerance and condemnation of the homosexual community across the globe. Through exploring the natural law position this paper exposes such a conclusion to be an erroneous misunderstanding of the natural law position. I build my natural law position on the foundation of an explication of the metaphysics underpinning natural law ethics. Having established the natural law ethics position, the paper then goes on to show that many of the arguments claiming homosexuality to be immoral do not sit well with the natural law ethics position, and many stem from a misunderstanding or a misapplication of natural law ethics. Firstly, I briefly dismiss the view that because homosexual sex is outside of a biological norm it is thus immoral. I then move on to dismiss Bradshaw’s view that homosexuality entails a violation of the body’s moral space by showing that his argument misunderstands natural law ethics and relies on vagaries and intuition-pumping rhetoric. Moving from there I engage the claim that homosexual sex is immoral on the grounds that the partners involved utilise each other instrumentally. Both Finnis and George argue for this claim and I attempt to show that neither of their arguments holds any water. The paper also refutes two other arguments against the morality of homosexuality: the first that because homosexual sexual engagement cannot take part in the all-level union of a reproductive marriage that it cannot be moral; the other argues that homosexual sexual engagement is subversive to the understanding of a society and is thus immoral. In conclusion I claim that none of the arguments that the paper considers give us a justifiable reason for believing that homosexual sex is immoral, and that in many cases it may even be considered moral due to it’s ability to contribute to the partners overall flourishing: the telos of natural law ethics.

Related Papers

The Heythrop Journal

Michael G. Lawler

Journal of Applied Philosophy

Kurt Blankschaen

Revista Direito Gv

Ben Williamson

In this paper I will argue from a Natural Law Metaethic by offering three objections to certain underlying notions that are foundational to arguments for same-sex marriage. I will argue that same-sex marriage entails a constructionist position on gender, sex, and the family, a constructionist view of human telos, and undermines marriage equality by its own principles. Natural law theory, by contrast, affirms the following views as true: an essentialist view of gender, sex and the family, an Aristotelian-Thomistic conception of human telos, and that marital rights are ultimately grounded in the teleological function of human nature, not mere human desires or consent. Finally, I will target the fundamental metaphysical issues that lurk behind certain arguments for same-sex marriage, attempt to show they result in certain absurdities and represent an inferior model of marriage than the traditional view.

Raymond Marcin

Robert P. George

Anil Rodrigues

Liton Chandra Biswas

Legal arguments both for and against homosexual rights often are dogmatic, indecisive, unnecessarily complex, and ultimately futile. The arguments, which show a homogeneous pattern irrespective of jurisdictions, forums, and eras, cause more complexities and problems than decisively solving them. Judgments related to homosexuality, including the glorious judgements ranging from Dudgeon to Navtej, have fundamental flaws in their reasoning. The judgements are founded on personal choice-based secondary justifications which are self-contradictory, self-limiting, self-defeating, confusing, and contingent. Consequently, the rights of homosexual people are often interpreted as secondary rights which are subject to the sympathy or kindness of the heterosexual majority. This precarious situation places the fate of homosexual people in a constant state of uncertainty swaying on the fulcrum of principles, provisos, and probabilities that the inconsiderate legal reasoning gives rise to.

Termaine Chizikani

The paper sought to demonstrate that if homosexuality is determined then an ethics of tolerance should be adopted in order to cater for people who have no choice in their being who they are. It was observed that moral theories rest their conclusions on the assumption that the human being is responsible for all their actions and hence should be held morally accountable for them. However, in light of deterministic factors both in the individual and their environment, this responsibility in terms of choosing to become homosexual is taken away. Hence, the harsh treatment that these people receive on the African continent can be seen from this perspective as unwarranted, and it is high time that these factors need to be taken into consideration for the betterment of Africa’s future. The previous paper argued that certain types of food could cause hormonal imbalances. The natural response to this argument is that people should refrain from eating them. There is more to this than meets the eye. The social status of different members of society is such that they cannot afford variety and to avoid such food as soya beans and soya chunks. This is the normal food consumed by average people especially in Zimbabwe. There is also the regional or geographical argument that suggests that some countries have staple foods most of the listed food. This is what can be properly grown in their climatic regions and geographic soil. In view of such issues, it is apparent to posit that one cannot starve for fear of inciting hormonal imbalances. One can now fully appreciate the dilemma that is at hand.

Maxime Rowson

RELATED PAPERS

EMBnet.journal

Athina Ropodi

Angélica de Godoy Torres Lima

Physical Review C

Steven Koonin

Shih-Yu Tsai

Mutation Research/Genetic Toxicology and Environmental Mutagenesis

maritxu guiresse

Margareth Helfer, Domenico Rosani. In: G. M. Caletti, K. Summerer (eds.), Criminalizing Intimate Image Abuse, Oxford University Press, 2024

Domenico Rosani

Environmental Science & Technology

Bala Rathinasabapathi

Journal of Cystic Fibrosis

Carlo Corbetta

Australian Journal of Rural Health

Bruce Chater

KAPIL ,Roll no 71

Science and Technology Development Journal - Natural Sciences

Vishal Kumar

Iranian Journal of Science and Technology, Transactions A: Science

Golnaz Sayyadzadeh

Betsy Hirsch

Nigar Pandrianto

Microbiologia Medica

Ibrahima SENE

Peter K. Swart

Journal of Perinatology

Alison Walsh

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Homosexuality

The term ‘homosexuality’ was coined in the late 19 th century by a German psychologist, Karoly Maria Benkert. Although the term is new, discussions about sexuality in general, and same-sex attraction in particular, have occasioned philosophical discussion ranging from Plato's Symposium to contemporary queer theory. Since the history of cultural understandings of same-sex attraction is relevant to the philosophical issues raised by those understandings, it is necessary to review briefly some of the social history of homosexuality. Arising out of this history, at least in the West, is the idea of natural law and some interpretations of that law as forbidding homosexual sex. References to natural law still play an important role in contemporary debates about homosexuality in religion, politics, and even courtrooms. Finally, perhaps the most significant recent social change involving homosexuality is the emergence of the gay liberation movement in the West. In philosophical circles this movement is, in part, represented through a rather diverse group of thinkers who are grouped under the label of queer theory. A central issue raised by queer theory, which will be discussed below, is whether homosexuality, and hence also heterosexuality and bisexuality, is socially constructed or purely driven by biological forces.

2. Natural Law

3. queer theory and the social construction of sexuality, 4. conclusion, bibliography, other internet resources, related entries.

As has been frequently noted, the ancient Greeks did not have terms or concepts that correspond to the contemporary dichotomy of ‘heterosexual’ and ‘homosexual’. There is a wealth of material from ancient Greece pertinent to issues of sexuality, ranging from dialogues of Plato, such as the Symposium , to plays by Aristophanes, and Greek artwork and vases. What follows is a brief description of ancient Greek attitudes, but it is important to recognize that there was regional variation. For example, in parts of Ionia there were general strictures against same-sex eros , while in Elis and Boiotia (e.g., Thebes), it was approved of and even celebrated (cf. Dover, 1989; Halperin, 1990).

Probably the most frequent assumption of sexual orientation is that persons can respond erotically to beauty in either sex. Diogenes Laeurtius, for example, wrote of Alcibiades, the Athenian general and politician of the 5 th century B.C., “in his adolescence he drew away the husbands from their wives, and as a young man the wives from their husbands.” (Quoted in Greenberg, 1988, 144) Some persons were noted for their exclusive interests in persons of one gender. For example, Alexander the Great and the founder of Stoicism, Zeno of Citium, were known for their exclusive interest in boys and other men. Such persons, however, are generally portrayed as the exception. Furthermore, the issue of what gender one is attracted to is seen as an issue of taste or preference, rather than as a moral issue. A character in Plutarch's Erotikos ( Dialogue on Love ) argues that “the noble lover of beauty engages in love wherever he sees excellence and splendid natural endowment without regard for any difference in physiological detail.” ( Ibid ., 146) Gender just becomes irrelevant “detail” and instead the excellence in character and beauty is what is most important.

Even though the gender that one was erotically attracted to (at any specific time, given the assumption that persons will likely be attracted to persons of both sexes) was not important, other issues were salient, such as whether one exercised moderation. Status concerns were also of the highest importance. Given that only free men had full status, women and male slaves were not problematic sexual partners. Sex between freemen, however, was problematic for status. The central distinction in ancient Greek sexual relations was between taking an active or insertive role, versus a passive or penetrated one. The passive role was acceptable only for inferiors, such as women, slaves, or male youths who were not yet citizens. Hence the cultural ideal of a same-sex relationship was between an older man, probably in his 20's or 30's, known as the erastes , and a boy whose beard had not yet begun to grow, the eromenos or paidika . In this relationship there was courtship ritual, involving gifts (such as a rooster), and other norms. The erastes had to show that he had nobler interests in the boy, rather than a purely sexual concern. The boy was not to submit too easily, and if pursued by more than one man, was to show discretion and pick the more noble one. There is also evidence that penetration was often avoided by having the erastes face his beloved and place his penis between the thighs of the eromenos , which is known as intercrural sex. The relationship was to be temporary and should end upon the boy reaching adulthood (Dover, 1989). To continue in a submissive role even while one should be an equal citizen was considered troubling, although there certainly were many adult male same-sex relationships that were noted and not strongly stigmatized. While the passive role was thus seen as problematic, to be attracted to men was often taken as a sign of masculinity. Greek gods, such as Zeus, had stories of same-sex exploits attributed to them, as did other key figures in Greek myth and literature, such as Achilles and Hercules. Plato, in the Symposium , argues for an army to be comprised of same-sex lovers. Thebes did form such a regiment, the Sacred Band of Thebes, formed of 500 soldiers. They were renowned in the ancient world for their valor in battle.

Ancient Rome had many parallels in its understanding of same-sex attraction, and sexual issues more generally, to ancient Greece. This is especially true under the Republic. Yet under the Empire, Roman society slowly became more negative in its views towards sexuality, probably due to social and economic turmoil, even before Christianity became influential.

Exactly what attitude the New Testament has towards sexuality in general, and same-sex attraction in particular, is a matter of sharp debate. John Boswell argues, in his fascinating Christianity, Social Tolerance, and Homosexuality , that many passages taken today as condemnations of homosexuality are more concerned with prostitution, or where same-sex acts are described as “unnatural” the meaning is more akin to ‘out of the ordinary’ rather than as immoral (Boswell, 1980, ch.4; see also Boswell, 1994). Yet others have criticized, sometimes persuasively, Boswell's scholarship (see Greenberg, 1988, ch.5). What is clear, however, is that while condemnation of same-sex attraction is marginal to the Gospels and only an intermittent focus in the rest of the New Testament, early Christian church fathers were much more outspoken. In their writings there is a horror at any sort of sex, but in a few generations these views eased, in part due no doubt to practical concerns of recruiting converts. By the fourth and fifth centuries the mainstream Christian view allowed for procreative sex.

This viewpoint, that procreative sex within marriage is allowed, while every other expression of sexuality is sinful, can be found, for example, in St. Augustine. This understanding leads to a concern with the gender of one's partner that is not found in previous Greek or Roman views, and it clearly forbids homosexual acts. Soon this attitude, especially towards homosexual sex, came to be reflected in Roman Law. In Justinian's Code, promulgated in 529, persons who engaged in homosexual sex were to be executed, although those who were repentant could be spared. Historians agree that the late Roman Empire saw a rise in intolerance towards sexuality, although there were again important regional variations.

With the decline of the Roman Empire, and its replacement by various barbarian kingdoms, a general tolerance (with the sole exception of Visigothic Spain) of homosexual acts prevailed. As one prominent scholar puts it, “European secular law contained few measures against homosexuality until the middle of the thirteenth century.” (Greenberg, 1988, 260) Even while some Christian theologians continued to denounce nonprocreative sexuality, including same-sex acts, a genre of homophilic literature, especially among the clergy, developed in the eleventh and twelfth centuries (Boswell, 1980, chapters 8 and 9).

The latter part of the twelfth through the fourteenth centuries, however, saw a sharp rise in intolerance towards homosexual sex, alongside persecution of Jews, Muslims, heretics, and others. While the causes of this are somewhat unclear, it is likely that increased class conflict alongside the Gregorian reform movement in the Catholic Church were two important factors. The Church itself started to appeal to a conception of “nature” as the standard of morality, and drew it in such a way so as to forbid homosexual sex (as well as extramarital sex, nonprocreative sex within marriage, and often masturbation). For example, the first ecumenical council to condemn homosexual sex, Lateran III of 1179, stated that “Whoever shall be found to have committed that incontinence which is against nature” shall be punished, the severity of which depended upon whether the transgressor was a cleric or layperson (quoted in Boswell, 1980, 277). This appeal to natural law (discussed below) became very influential in the Western tradition. An important point to note, however, is that the key category here is the ‘sodomite,’ which differs from the contemporary idea of ‘homosexual’. A sodomite was understood as act-defined, rather than as a type of person. Someone who had desires to engage in sodomy, yet did not act upon them, was not a sodomite. Also, persons who engaged in heterosexual sodomy were also sodomites. There are reports of persons being burned to death or beheaded for sodomy with a spouse (Greenberg, 1988, 277). Finally, a person who had engaged in sodomy, yet who had repented of his sin and vowed to never do it again, was no longer a sodomite. The gender of one's partner is again not of decisive importance, although some medieval theologians single out same-sex sodomy as the worst type of sexual crime.

For the next several centuries in Europe, the laws against homosexual sex were severe in their penalties. Enforcement, however, was episodic. In some regions, decades would pass without any prosecutions. Yet the Dutch, in the 1730's, mounted a harsh anti-sodomy campaign (alongside an anti-Gypsy pogrom), even using torture to obtain confessions. As many as one hundred men and boys were executed and denied burial (Greenberg, 1988, 313-4). Also, the degree to which sodomy and same-sex attraction were accepted varied by class, with the middle class taking the narrowest view, while the aristocracy and nobility often accepted public expressions of alternative sexualities. At times, even with the risk of severe punishment, same-sex oriented subcultures would flourish in cities, sometimes only to be suppressed by the authorities. In the 19 th century there was a significant reduction in the legal penalties for sodomy. The Napoleonic code decriminalized sodomy, and with Napoleon's conquests that Code spread. Furthermore, in many countries where homosexual sex remained a crime, the general movement at this time away from the death penalty usually meant that sodomy was removed from the list of capital offenses.

In the 18 th and 19 th centuries an overtly theological framework no longer dominated the discourse about same-sex attraction. Instead, secular arguments and interpretations became increasingly common. Probably the most important secular domain for discussions of homosexuality was in medicine, including psychology. This discourse, in turn, linked up with considerations about the state and its need for a growing population, good soldiers, and intact families marked by clearly defined gender roles. Doctors were called in by courts to examine sex crime defendants (Foucault, 1980; Greenberg, 1988). At the same time, the dramatic increase in school attendance rates and the average length of time spent in school, reduced transgenerational contact, and hence also the frequency of transgenerational sex. Same-sex relations between persons of roughly the same age became the norm.

Clearly the rise in the prestige of medicine resulted in part from the increasing ability of science to account for natural phenomena on the basis of mechanistic causation. The application of this viewpoint to humans led to accounts of sexuality as innate or biologically driven. The voluntarism of the medieval understanding of sodomy, that sodomites chose sin, gave way to the modern notion of homosexuality as a deep, unchosen characteristic of persons, regardless of whether they act upon that orientation. The idea of a ‘latent sodomite’ would not have made sense, yet under this new view it does make sense to speak of a person as a ‘latent homosexual.’ Instead of specific acts defining a person, as in the medieval view, an entire physical and mental makeup, usually portrayed as somehow defective or pathological, is ascribed to the modern category of ‘homosexual.’ Although there are historical precursors to these ideas (e.g., Aristotle gave a physiological explanation of passive homosexuality), medicine gave them greater public exposure and credibility (Greenberg, 1988, ch.15). The effects of these ideas cut in conflicting ways. Since homosexuality is, by this view, not chosen, it makes less sense to criminalize it. Persons are not choosing evil acts. Yet persons may be expressing a diseased or pathological mental state, and hence medical intervention for a cure is appropriate. Hence doctors, especially psychiatrists, campaigned for the repeal or reduction of criminal penalties for consensual homosexual sodomy, yet intervened to “rehabilitate” homosexuals. They also sought to develop techniques to prevent children from becoming homosexual, for example by arguing that childhood masturbation caused homosexuality, hence it must be closely guarded against.

In the 20 th century sexual roles were redefined once again. For a variety of reasons, premarital intercourse slowly became more common and eventually acceptable. With the decline of prohibitions against sex for the sake of pleasure even outside of marriage, it became more difficult to argue against gay sex. These trends were especially strong in the 1960's, and it was in this context that the gay liberation movement took off. Although gay and lesbian rights groups had been around for decades, the low-key approach of the Mattachine Society (named after a medieval secret society) and the Daughters of Bilitis had not gained much ground. This changed in the early morning hours of June 28, 1969, when the patrons of the Stonewall Inn, a gay bar in Greenwich Village, rioted after a police raid. In the aftermath of that event, gay and lesbian groups began to organize around the country. Gay Democratic clubs were created in every major city, and one fourth of all college campuses had gay and lesbian groups (Shilts, 1993, ch.28). Large gay urban communities in cities from coast to coast became the norm. The American Psychiatric Association removed homosexuality from its official listing of mental disorders. The increased visibility of gays and lesbians has become a permanent feature of American life despite the two critical setbacks of the AIDS epidemic and an anti-gay backlash (see Berman, 1993, for a good survey). The post-Stonewall era has also seen marked changes in Western Europe, where the repeal of anti-sodomy laws and legal equality for gays and lesbians has become common.

Today natural law theory offers the most common intellectual defense for differential treatment of gays and lesbians, and as such it merits attention. The development of natural law is a long and very complicated story, but a reasonable place to begin is with the dialogues of Plato, for this is where some of the central ideas are first articulated, and, significantly enough, are immediately applied to the sexual domain. For the Sophists, the human world is a realm of convention and change, rather than of unchanging moral truth. Plato, in contrast, argued that unchanging truths underpin the flux of the material world. Reality, including eternal moral truths, is a matter of phusis . Even though there is clearly a great degree of variety in conventions from one city to another (something ancient Greeks became increasingly aware of), there is still an unwritten standard, or law, that humans should live under.

In the Laws , Plato applies the idea of a fixed, natural law to sex, and takes a much harsher line than he does in the Symposium or the Phraedrus . In Book One he writes about how opposite-sex sex acts cause pleasure by nature, while same-sex sexuality is “unnatural” (636c). In Book Eight, the Athenian speaker considers how to have legislation banning homosexual acts, masturbation, and illegitimate procreative sex widely accepted. He then states that this law is according to nature (838-839d). Probably the best way of understanding Plato's discussion here is in the context of his overall concerns with the appetitive part of the soul and how best to control it. Plato clearly sees same-sex passions as especially strong, and hence particularly problematic, although in the Symposium that erotic attraction could be the catalyst for a life of philosophy, rather than base sensuality (Cf. Dover, 1989, 153-170; Nussbaum, 1999, esp. chapter 12).

Other figures played important roles in the development of natural law theory. Aristotle, with his emphasis upon reason as the distinctive human function, and the Stoics, with their emphasis upon human beings as a part of the natural order of the cosmos, both helped to shape the natural law perspective which says that “True law is right reason in agreement with nature,” as Cicero put it. Aristotle, in his approach, did allow for change to occur according to nature, and therefore the way that natural law is embodied could itself change with time, which was an idea Aquinas later incorporated into his own natural law theory. Aristotle did not write extensively about sexual issues, since he was less concerned with the appetites than Plato. Probably the best reconstruction of his views places him in mainstream Greek society as outlined above; the main issue is that of active versus a passive role, with only the latter problematic for those who either are or will become citizens. Zeno, the founder of Stoicism, was, according to his contemporaries, only attracted to men, and his thought had no prohibitions against same-sex sexuality. In contrast, Cicero, a later Stoic, was dismissive about sexuality in general, with some harsher remarks towards same-sex pursuits (Cicero, 1966, 407-415).

The most influential formulation of natural law theory was made by Thomas Aquinas in the thirteenth century. Integrating an Aristotelian approach with Christian theology, Aquinas emphasized the centrality of certain human goods, including marriage and procreation. While Aquinas did not write much about same-sex sexual relations, he did write at length about various sex acts as sins. For Aquinas, sexuality that was within the bounds of marriage and which helped to further what he saw as the distinctive goods of marriage, mainly love, companionship, and legitimate offspring, was permissible, and even good. Aquinas did not argue that procreation was a necessary part of moral or just sex; married couples could enjoy sex without the motive of having children, and sex in marriages where one or both partners is sterile (perhaps because the woman is postmenopausal) is also potentially just (given a motive of expressing love). So far Aquinas' view actually need not rule out homosexual sex. For example, a Thomist could embrace same-sex marriage, and then apply the same reasoning, simply seeing the couple as a reproductively sterile, yet still fully loving and companionate union.