- Event Website Publish a modern and mobile friendly event website.

- Registration & Payments Collect registrations & online payments for your event.

- Abstract Management Collect and manage all your abstract submissions.

- Peer Reviews Easily distribute and manage your peer reviews.

- Conference Program Effortlessly build & publish your event program.

- Virtual Poster Sessions Host engaging virtual poster sessions.

- Customer Success Stories

- Wall of Love ❤️

How to Write an Abstract For a Poster Presentation Application

Published on 15 Aug 2023

Attending a conference is a great achievement for a young researcher. Besides presenting your research to your peers, networking with researchers of other institutions and building future collaborations are other benefits.

Above all, it allows you to question your research and improve it based on the feedback you receive. As Sönke Ahrens wrote in How To Take Smart Notes "an idea kept private is as good as one you never had".

The poster presentation is one way to present your research at a conference. Contrary to some beliefs, poster presenters aren't the ones relegated to oral presentation and poster sessions are far from second zone presentations; Poster presentations favor natural interactions with peers and can lead to very valuable talks.

The application process

The abstract submitted during the application process is not the same as the poster abstract. The abstract submission is usually longer and you have to respect several points when writing it:

- Use the template provided by the conference organization (if applicable);

- Specify the abstract title, list author names, co-authors and the institutions in the banner;

- Use sub-headings to show out the structure of your abstract (if authorized);

- Respect the maximum word count (usually about a 300 word limit) and do not exceed one page;

- Exclude figures or graphs, keep them for your poster;

- Minimize the number of citations/references.

- Respect the submission deadline.

The 3 components of an abstract for a conference application

Most poster abstract submissions follow the classical IMRaD structure, also called the hourglass structure.

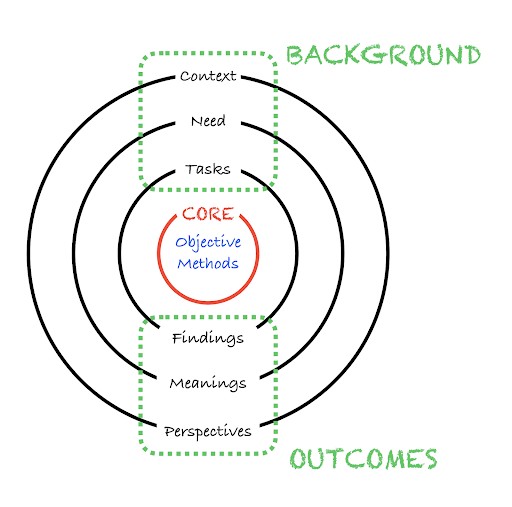

To make your abstract more memorable and impactful, you can try the Russian doll structure. Contrary to IMRaD, which has a more linear progression of ideas, the Russian doll structure emphasizes the WHY and WHAT. It unravels the research narrative layer by layer, capturing the reader’s attention more effectively.

Your abstract should be something the reviewer wants to open in order to discover the different layers of your research down to its core (like opening a Russian doll or peeling an onion). Then, it should be wrapped up elegantly with the outcomes (see figure below) like dressing the same Russian doll.

Hence, to design the best Russian doll, I recommend Jean-Luc Doumont's structure as detailed in his book Trees, Maps and Theorems that I adapted in 3 main components:

1. Background. The first component answers to the WHY and details the motivations of your research at different levels:

- Context : Why now? Describe the big picture, the current situation.

- Need : Why is it relevant to the reader? Describe the research question.

- Tasks : Why do we have to do this way? Review the studies related to your research question and emphasize the gap between the need and what was done.

2. Core . The center component answer to the HOW and consists in describing the objective of your research and its method:

- Objective : How did I focus on the need? Detail the purpose of your study.

- Methods : How did I proceed? Describe briefly the workflow (study population, softwares, tools, process, models, etc.)

3. Outcomes . The final component answers to the WHAT and details the take-aways of your research at different levels:

- Findings : What resulted from my method? Describe the main results (only).

- Meanings : What do the research findings mean to the reader? Discuss your results by linking them to your objective and research question.

- Perspectives : What should be the next steps? Propose further studies that could improve, complement or challenge yours.

It's worth noting that this structure emphasizes the WHY and the WHAT more than the HOW. It is the secret of great scientific storytelling .

The illustration below provides a clearer understanding of the logical flow among the three components and their respective layers. Note that, if authorized, sub-headings can be used for each section mentioned above.

4 tips to help get your abstract qualified

Here are some tips to give yourself the best chance of success for having your poster abstract accepted:

- Start by answering questions . It is very hard for the human brain to create something totally from scratch. Hence, allow the questions detailed above to guide you in creating the first path to explore.

- Write first, then edit . Do not try to do both at the same time. You won't get the final version of your abstract after your first try. Be patient, and "let your text die" before editing it with a fresh new point of view.

- "Kill your darlings'' . Not everything is necessary in the abstract. In Stephen Sondheim's words , West Side Story composer, "you have to throw out good stuff to get the best stuff". You will be amazed at just how surprising and efficient this tip is.

- Steal like an artist . As suggested by Austin Kleon's book title , get inspiration from others by reading other abstracts. It can be very helpful if you struggle finding punchy phrasing or transitions. I'm not referring to plagiarism, only getting good ideas about form (and not content) that can be adapted and used in your abstract.

When you get accepted, it's time to design your poster board and prepare your pitch. Pick your favorite graphics software and bring your abstract to life with figures, tables, and colors. We have written an article on how to make a scientific poster , do not hesitate to take a look.

5 Best Event Registration Platforms for Your Next Conference

By having one software to organize registrations and submissions, a pediatric health center runs aro...

5 Essential Conference Apps for Your Event

In today’s digital age, the success of any conference hinges not just on the content and speakers bu...

USF St. Petersburg Nelson Poynter Library will be closed on Monday, Dec 12, 2022 for the USF Libraries In-Service Day event. Operations will resume on Tuesday, Dec 13, 2022

Due to severe weather, the USF St. Petersburg Library will remain closed on Thursday, August 31st and reopen on Friday, September 1st.. For information concerning the libraries on the Tampa and Sarasota-Manatee campuses and the Shimberg Health Sciences Library , please visit their webpages. Students and faculty can visit www.usf.edu/news For official USF News regarding the weather and other closures.

There will be a preventative maintenance done on our ILLiad software on February 24, 2023 between the hours of 9pm and 1am . Patrons may not be able to make requests during this time. Thank you for your patience.

- Nelson Poynter Memorial Library

- USF St. Petersburg Library

- General Guides

Research Posters: Toolkit

Writing abstracts.

- Data Visualization

- Design Choices

- Before you Print

- Virtual Presentations

- In-Person Presentations

- Publishing Your Poster

- Citing Sources This link opens in a new window

- Workshop: Creating Research Poster Presentations

What is an abstract?

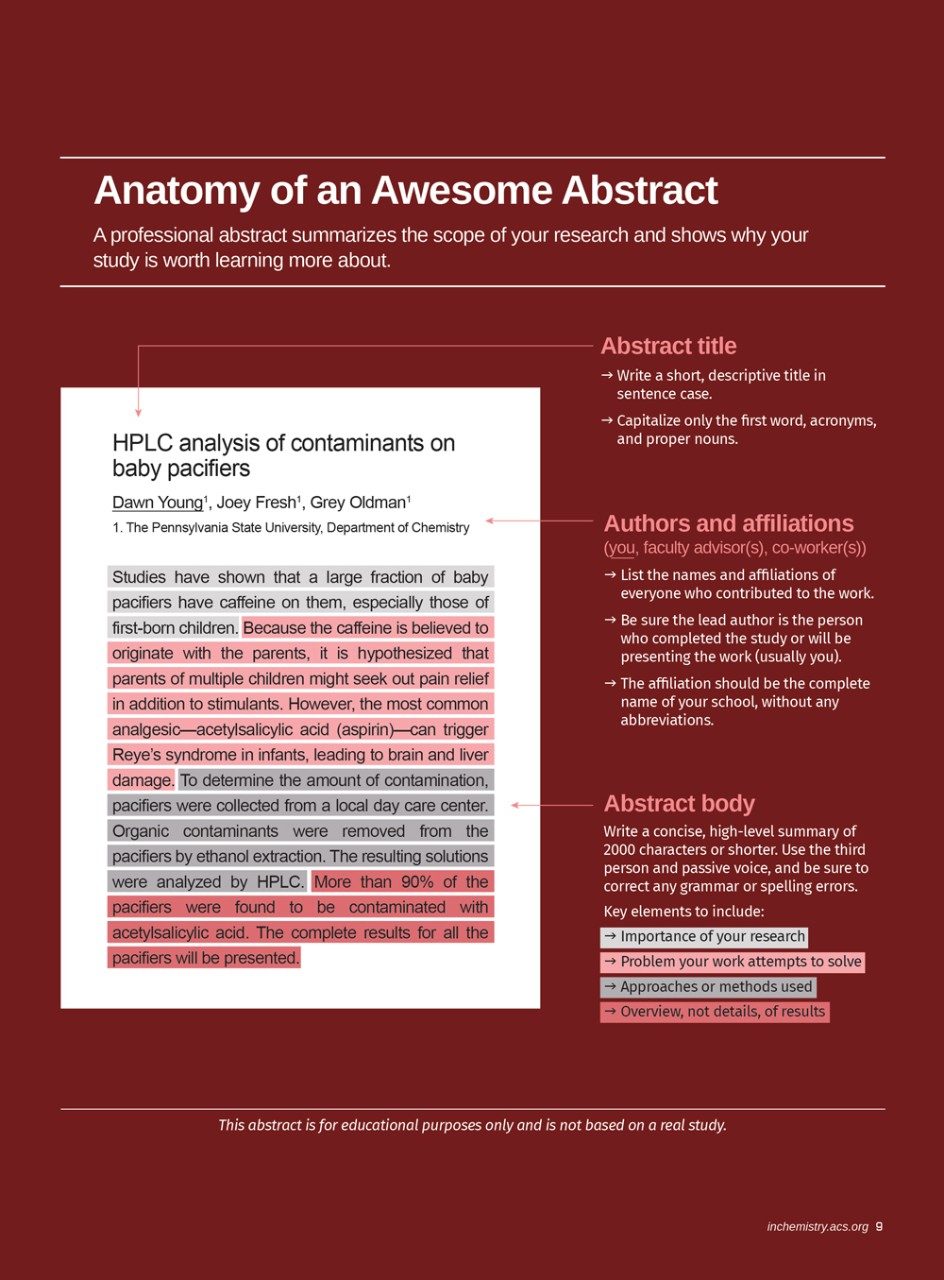

An abstract is a short, concise overview (usually 100-150 words) of your research project. An abstract requires academic writing that is persuasive in nature and should compel the reader to want to know more about your research.

Typically there are five (5) components that can be identified in an effective research abstract. While components mentioned may vary according to the discipline, in general the elements mentioned below apply across disciplines.

Components of an Abstract

Each sentence of the following abstract represents a key component of a research abstract, and the below table lists and defines each component. Can you identify which sentence provides the information for each key component?

| Background Information | Establishes the issue you are addressing with your research. In the first sentence let the reader know why they should care about your work. |

| Thesis statement/Research Question/Hypothesis | Provides the details of the issue that your research addresses. Frames the rest of the ideas in the abstract. |

| Methods/Approaches/Materials | Briefly describes the research was carried out. It is not necessary to go into minor details. |

| Results/Findings/Expectations | Outlines the major findings of your research project (or what you hope to find). Best to list one key finding rather than all of the findings. |

| Conclusions/Implications/Future Research | Explanation regarding WHY the research is significant and HOW it contributes to your discipline. May also discuss the lasting impacts of the work on society, policy, or future research. |

Write and Re-Write

It is not easy to include all this information in just a few words. Start by writing a summary that includes whatever you think is important, and then gradually prune it down to size by removing unnecessary words, while still retaining the necessary concepts.

Don't use acronyms, abbreviations, or in-text citations. It should be able to stand alone without any citations.

Hornstein, Maddie (n.d.) The Anatomy of an Abstract. Kathleen Jones White Writing Center at Indiana University of Pennsylvania.

Lighthouse, A. (2017, December 15). Anatomy of an abstract for a scholarly journal article: A five-sentence model. Retrieved from http://www.newlearnerlab.com/blog/anatomy-of-an-abstract-for-a-scholarly-journal-article-a-five-sentence-model

- << Previous: Home

- Next: Templates and Designing Your Poster >>

- Last Updated: Jan 26, 2024 3:17 PM

- URL: https://lib.stpetersburg.usf.edu/posterpresentations

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Scientific Posters

Characteristics of a scientific poster.

- Organized, clean, simple design.

- Focused on one specific research topic that can be explained in 5-15 minutes.

- Contains a Title, Authors, Abstract, Introduction, Materials & Methods, Results, Discussion, References and Acknowledgements.

- Has four to ten high-resolution figures and/or tables that describe the research in detail.

- Contains minimal text, with figures and tables being the main focus.

Scientific Poster

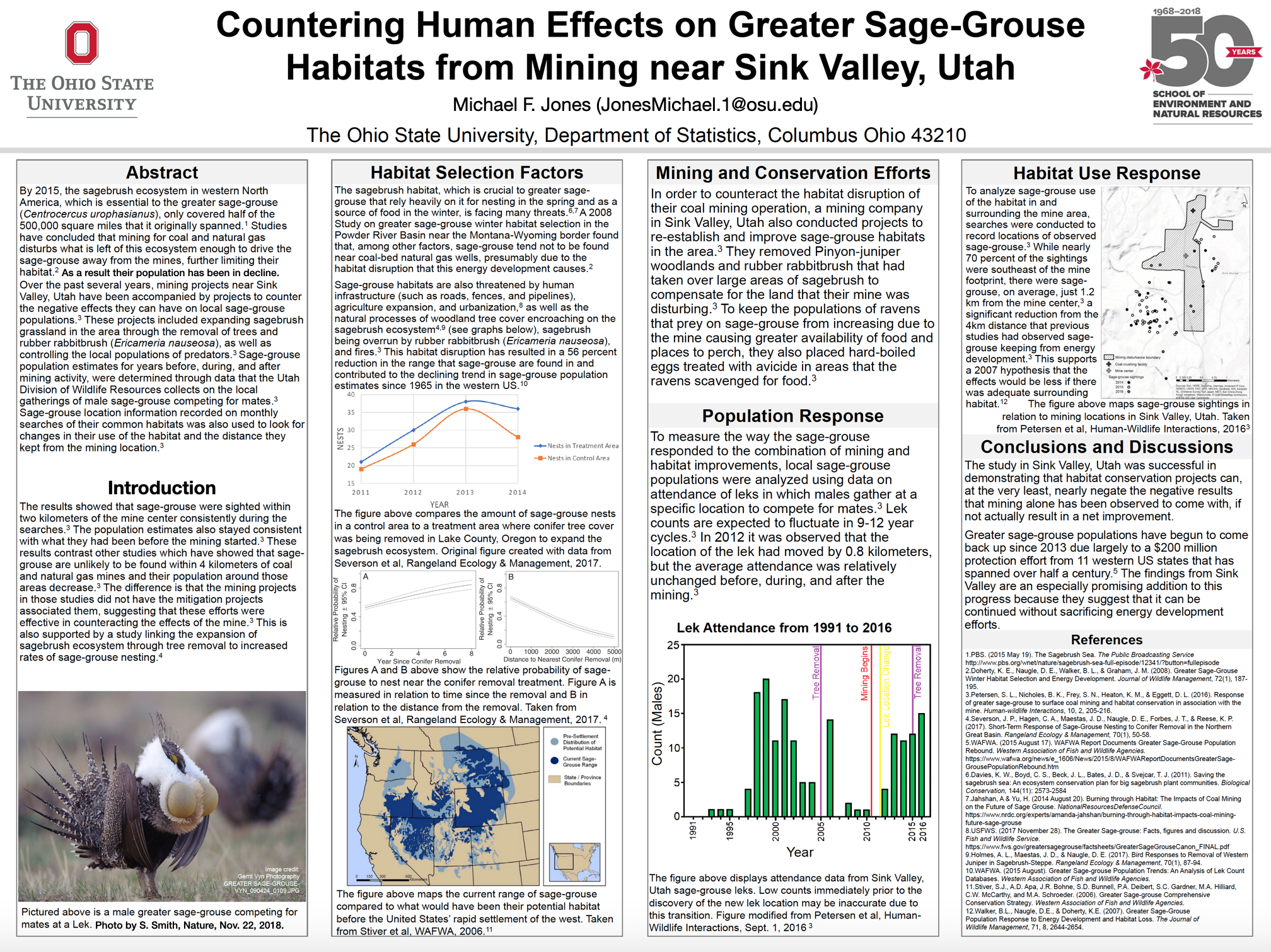

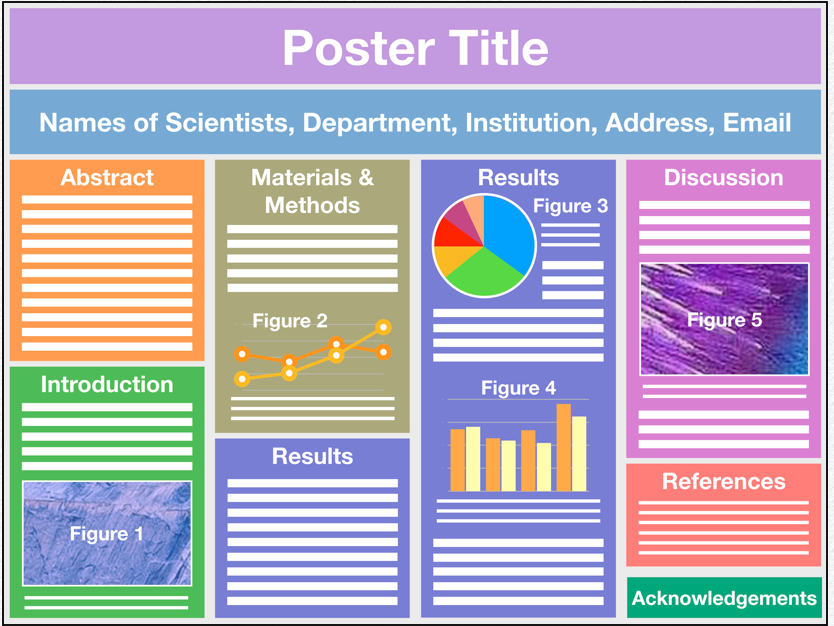

A scientific poster ( Fig.1 ) is an illustrated summary of research that scientists and engineers use to present their scientific discoveries to larger audiences. A typical poster is printed on paper with dimensions of 36-inches (height) by 48-inches (width).

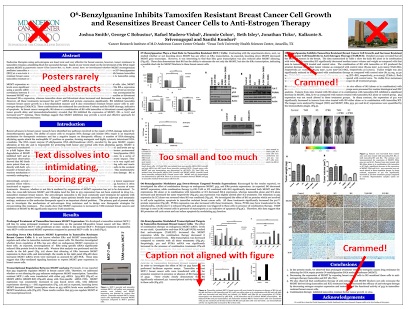

Figure 1. Scientific Poster

Posters are displayed at events such as symposiums, conferences and meetings to show new discoveries, new results and new information to scientists and engineers from different fields. A large event can have hundreds of posters on display at one time with scientists and engineers standing beside their individual posters to showcase their research. A typical interaction between a poster presenter and an audience member will last 5-15 minutes.

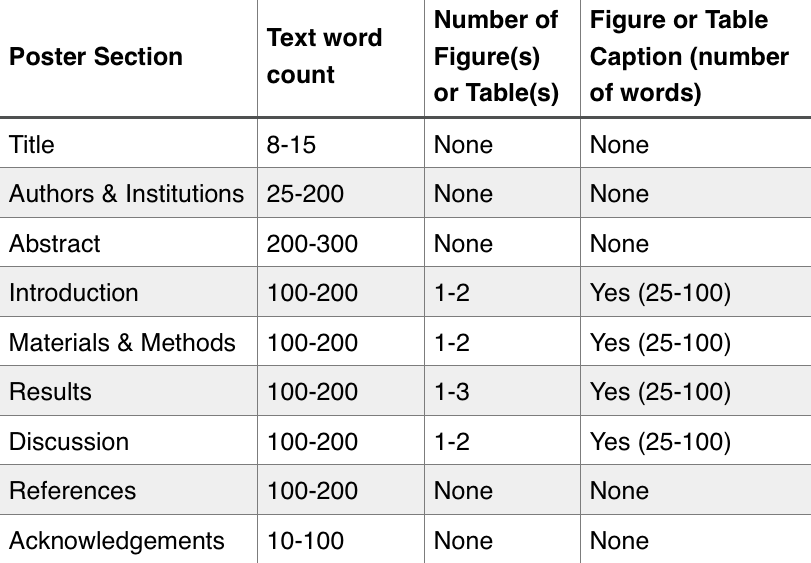

Scientific posters are organized systematically into the following parts (or sections): Title, Authors, Abstract, Introduction, Materials and Methods, Results, Discussion, Acknowledgments and References ( Table 1 and Fig. 2 ). Organizing a poster in this manner allows the reader to quickly comprehend the major points of the research and to understand the significance of the work.

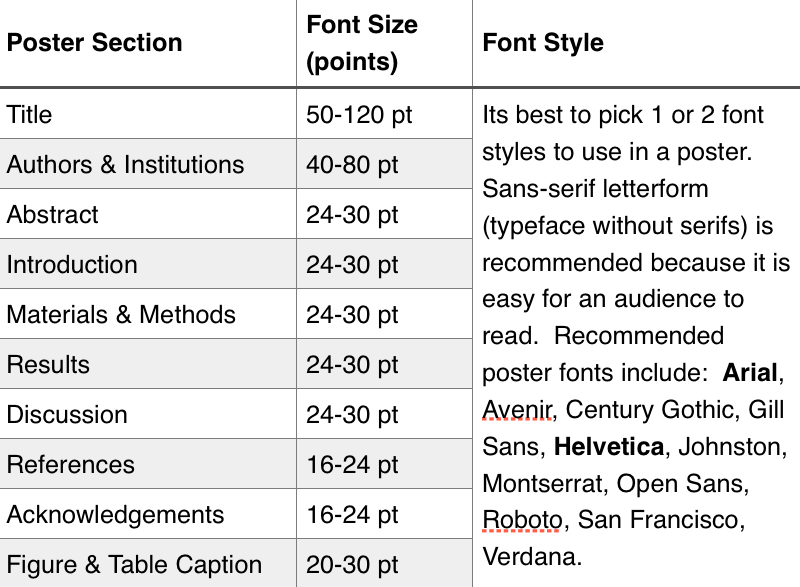

Table 1. Characteristics of a Scientific Poster

The most important parts of a scientific poster will likely be its figures and/or tables because these are what an audience will naturally focus their attention on. The phrase “a picture is worth a thousand words” is certainly true for scientific posters, and so it is very important for the poster’s author(s) to create informative figures that a reader can understand. The “ideal” figure can be challenging to create. Providing too much information in a figure will only serve to confuse the reader (or audience). Provide too little information and the reader will be left with an incomplete understanding of the research. Both situations should be avoided because they prevent a scientist from effectively communicating with their audience.

Authors use different sizes of font for their poster text ( Table 2 ). The general rule is to use a font size that can be read from a distance of 3-feet (1 meter), which is the approximate distance that a person will stand when viewing a poster. The largest fonts (e.g., 40-120 point font) will be used for the title, author list and institutions. Section headings will use 30-40 point font. Section text, table captions, figure captions and references will typically use 20-30 point font. Font sizes smaller than about 20-points can be difficult for an audience to read and should only be used for the References and Acknowledgements sections ( Table 2 ).

Table 2. Poster Font Size and Style

A poster abstract contains all text (no figures, no tables) and appears at the beginning of the poster ( Fig. 2 ). An abstract is one paragraph containing 200-300 words in length. The Introduction section ( Fig. 2 ) appears after the abstract and typically contains 100-200 words of text, a figure(s) and/or table(s) and a caption for each figure and table consisting of 25-100 words for each caption. The Material and Methods sections ( Fig. 2 ) appears third and consists of 100-200 words of text, a figure(s) and/or table(s) and a caption for each figure and table consisting of 25-100 words for each caption. This is followed by the Results section and Discussion section ( Fig. 2 ). Each of these sections contain 100-200 words of text, a figure(s) and/or table(s) and a caption for each figure and table consisting of 25-100 words for each caption. Sometimes these two parts of a poster are combined into one large section titled Results and Discussion. Some posters contain a Conclusion section, which follows the Discussion section. The example shown is Figure 2 does not contain a Conclusion section. The final parts of a poster are the References and Acknowledgements sections ( Fig. 2 ).

Figure 2. Parts of a Scientific Poster

An audience will focus most of their attention on the poster title, abstract, figures and tables. Therefore, it is important to pay particular attention to these parts of a poster. A general rule is that less text is best and a figure is worth a thousand words. The text contained within a poster should be reserved for the most important information that a presenter wants to convey to their audience. The rest of the information will be communicated to the audience verbally by the scientist during their presentation.

Its very important for a scientist to thoroughly understand all the data and information contained within their poster so that they can effectively communicate the research to an audience both verbally (i.e., during their presentation) and visually (i.e., using the figures and tables contained within the poster). It is also important that the References section of a poster contains a thorough summary of all publications pertinent to the research presented in the poster. This way, if an audience member wants more information on a particular topic (e.g., instrument, technique, method, study site) the presenter can direct the audience to the publication(s) where more information can be found.

Scientific Posters: A Learner's Guide Copyright © 2020 by Ella Weaver; Kylienne A. Shaul; Henry Griffy; and Brian H. Lower is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- You are here:

- American Chemical Society

- Meetings & Events

- ACS Meetings & Expositions

- ACS Fall 2024

How to Write an Undergraduate Abstract

Writing an abstract for the undergraduate research poster session.

By Elzbieta Cook, Louisiana State University

General Rules and Accepted Practices

Successful abstracts exhibit what is generally accepted as good scientific communication. The following guidelines specify all aspects of how a good abstract is written.

The Title is informative; it is neither too long nor too short, and it does not oversell or sensationalize the content of the presentation.

- Make the title descriptive, yet short and sweet.

- Do not start the t itle with “The”, “A”, or “An.”

- Capitalize only the first letter of the first word of the title, the first letter of the first word after a colon, and any proper names, acronyms (e.g., NMR) or chemical formulas (e.g., NaOH).

- Do not put a period at the end of the title.

The body of the abstract briefly frames the researched issue, succinctly describes the performed research, and outlines the findings and general conclusions without going into too many details or numbers.

- Do not write everything you did in your work. Briefly frame the research you will be describing. Your poster will be a better place to elaborate on selected aspects of your research. Instead, make general statements in regards to what was done, what techniques were used, what type of information was gained (without going into details of specific results), and what the potential benefits or significance of the findings are.

- Ensure that the content of the abstract is approved by your research advisor. In addition to getting valuable feedback on how you write, your research advisor will know which results are ready to be shared in your presentation and which belong elsewhere. Additionally, the advisor is responsible for your work and, consequently, your work and results.

- Do not make literature references to other published research in the abstract. A good place for literature references is in the introduction of your poster. Likewise, unless specifically requested by the session organizers, do not include funding information in the abstract. Your research program and funding sources can be mentioned in the acknowledgment part of your poster.

- Do not use “I” and “we” when reporting on you research. It is okay to state, for instance, that “research in our group is focused on…” The passive voice is still the standard in scientific literature, even if it makes your English teacher cringe.

- Exercise restraint when placing figures, schemes, and tables in the abstract. The body of your poster is a much better place for the majority of artwork. Having said that, figures, schemes, and tables are allowed in the abstract, but you need to watch the character count, as these features quickly add hundreds of characters.

- Limit the number of characters for the entire abstract to 2,500 . This includes the title, the body, and the authors, along with their affiliations.

The list of authors, in addition to the presenting undergraduate student(s), always includes the name of the research advisor(s) as well as any other non-presenting author who contributed to the presented work.

- The list of authors must include the presenting author(s) . The presenting author is you and any other undergraduate student who will present the research with you.

- Include the name(s) of your research advisor(s) on the list of poster authors. With few exceptions, undergraduate research is typically funded through a grant applied for and received by a research mentor, and must be properly acknowledged. Your research project is likely the brainchild of your research advisor, even if you contributed to its development. Remember that credit must go where it belongs! Even if you are the only person who performs the experiments, you do so under the supervision of a research advisor or graduate student (who, in turn, is financially supported by the mentor). In addition, the costs of hosting you in the laboratory, including disposables, software licenses, hazardous waste disposal, and even the costs of keeping the lab air-conditioned, the lights on and the elevator functioning, are typically courtesy of the host group (covered from your mentor’s indirect costs). The reviewer of your abstract will check whether the list of authors includes the name of the research advisor. Submissions without this information will not be accepted until the necessary correction is made.

- List the presenting author first. While there is no strict rule about the order of authors, it is common that the presenting author is listed first. If there is more than one presenting author, the order should follow that of their contributions, followed by non-presenting authors, with the research mentor being listed at the end. Some research mentors elect to be the first authors on undergraduate research posters, but care must be taken so that they are not listed as presenting authors. Again, the reviewer of your abstract will check to see whether the research mentor is listed as a presenting author, and if that is the case, the abstract will be returned to the authors for further clarification.

NOTE: Only undergraduate students are allowed to present in the Undergraduate Research Poster session. Any research mentor who wishes to present the results from an undergraduate project must do so in another session.

Affiliations

- Ensure that the name and the address of each college, university, institute, etc., is the same for all authors who come from that school. For instance, MAPS, the ACS’s abstract submission system, will “think” that Penn State and The Pennsylvania State University are two different schools and will assign two different affiliations to authors who were, after all, working in the same lab!

- The order of affiliations should follow the order of authors.

Submitting an Abstract to the Correct Session

It is a common error for students and faculty to submit a poster abstract to an incorrect session. The confusion often comes from the fact that the Chemical Education division of the ACS (DivCHED) accepts two types of poster abstracts: those from faculty about their chemical education research and those from undergraduate students about their research in a particular technical discipline.

The Undergraduate Research Poster Session in DivCHED is custom made for undergraduate student research. It is a good place to submit an abstract here, whether it’s your first presentation at a National Meeting or your third or fourth (as long as you’re still an undergrad).

Nevertheless, you should consult with your research advisor to find the right place to submit. If you do plan on submitting to a division other than DivCHED (e.g. Division of Analytical Chemistry), it’s a good idea to check with the division program chair to find the best place to showcase your research.

The Undergraduate Research Poster Session is meant only for undergraduate student presenters (i.e., you!). ACS has created several sub-divisions for the various sub-disciplines in chemistry, so you can present in an area that closely relates to your research.

In the Undergraduate Research Poster Session, you’ll want to choose the area of chemistry your research fits best, such as biochemistry, environmental, etc. If your undergraduate research is organic chemistry, for example, select Undergraduate Research Posters: Organic Chemistry-Poster . Only if you have helped to develop a new laboratory experiment or in-class demonstration, or you have analyzed learning outcomes of new learning strategies or a new pedagogy—will you want to submit your abstract to Undergraduate Research Posters: Chemical Education-Poster.

Remember, you, as an undergraduate researcher, must register and attend the meeting to present your work. Please note that if a faculty researcher, a postdoctoral candidate, or a graduate student wishes to present a poster on chemistry education research, they should submit their abstract to the CHED division in the General Poster Session. This article is not meant for such submissions.

Get Support

Talk to our meetings team.

Contacts for registration, hotel, presenter support or any other questions.

Contact Meetings Team

Frequently Asked Questions

Access helpful tips to get the most out of ACS Meetings.

Denver, CO & Hybrid

Colorado Convention Center | August 18 - 22

#ACSFall2024

Accept & Close The ACS takes your privacy seriously as it relates to cookies. We use cookies to remember users, better understand ways to serve them, improve our value proposition, and optimize their experience. Learn more about managing your cookies at Cookies Policy .

1155 Sixteenth Street, NW, Washington, DC 20036, USA | service@acs.org | 1-800-333-9511 (US and Canada) | 614-447-3776 (outside North America)

- Terms of Use

- Accessibility

Copyright © 2024 American Chemical Society

How to Create an Academic Poster

- Designing Effective Research Posters

- Poster Templates

- Poster Printing Guidelines

How to Write a Poster Abstract or Proposal

- More Research Help

Little Memorial Library Printing Guidelines

How to print a poster:.

- Submit your poster print request here: https://midway.libwizard.com/f/posterprinting

- Submit your poster print request at least one week in advance of when you need it

- Go to the Business Office in LRC and pay for the poster (You may also call them at 859-846-5402 .)

- Wait for an email from The Center@Midway telling you to come pick up your poster

Printing specifications:

- Make your poster 36" x 48".

- Save your poster as a PDF. Only PDF files will be accepted.

- Use at least 300 dpi (but no more than 1200 dpi)

- File size should be no more than 10MB

- Poster must be school/study-related.

- Cost: $20 per poster (you will incur an additional $20 charge every time you want your poster re-printed because of a typo, wanting to change information, etc.).

- Poster Abstracts

What is an abstract/proposal and why should I write one?

If you want to submit your paper/research at a conference, you must first write a proposal. A poster proposal tells the conference committee what your poster is about and, depending on the conference guidelines, might include a poster abstract, your list of contributors, and/or presentation needs.

The poster abstract is the most important part of your proposal. It is a summary of your research poster, and tells the reader what your problem, method, results, and conclusions are. Most abstracts are only 75 -- 250 words long.

- << Previous: Poster Printing Guidelines

- Next: More Research Help >>

- Last Updated: Mar 23, 2021 11:17 AM

- URL: https://midway.libguides.com/AcademicPoster

RESEARCH HELP

- Research Guides

- Databases A-Z

- Journal Search

- Citation Help

LIBRARY SERVICES

- Accessibility

- Interlibrary Loan

- Study Rooms

INSTRUCTION SUPPORT

- Course Reserves

- Library Instruction

- Little Memorial Library

- 512 East Stephens Street

- 859.846.5316

- [email protected]

- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- How to make a...

How to make a scientific poster

- Related content

- Peer review

- Fiona Tasker , core medical trainee doctor

- 1 Royal Sussex County Hospital, Brighton BN2 5BE

Conference attendees will look at your poster only briefly, so a clear presentation is crucial

A scientific poster is an illustrated abstract of research that is displayed at meetings and conferences. A poster is a good way of presenting your information because it can reach a large audience, including people who might not be in your field. It is also a useful step towards publishing your research. Some conferences publish poster abstracts, which then count as publications in their own right.

A successful poster captures the viewer’s attention and communicates the key points clearly and succinctly. One author reviewed 142 posters at a national meeting and found that 33% were cluttered or sloppy, 22% had fonts that were too small to be easily read, and 38% had research objectives that could not be located in a one minute review. 1 Avoiding these mistakes is important to ensure your poster has a positive impact.

Where do I start?

If you have completed a project, you will need to research the right meeting or conference to submit your abstract to, if you have not done so already. You might need to ask your supervisor or consultants in the field of your topic for information about relevant conferences at which you can present your work.

You will usually be asked to submit an abstract online. The submission guidelines on the website should guide you on how to do this, as well as provide other valuable information such as formatting instructions and deadlines. Your abstract should state why your work is important, the specific objective or objectives, a brief but clear explanation of the methods, a summary of the main results, and the conclusions. I would not recommend adding the abstract to your poster unless this was stated in the conference guidelines because a poster is already a …

Log in using your username and password

BMA Member Log In

If you have a subscription to The BMJ, log in:

- Need to activate

- Log in via institution

- Log in via OpenAthens

Log in through your institution

Subscribe from £184 *.

Subscribe and get access to all BMJ articles, and much more.

* For online subscription

Access this article for 1 day for: £33 / $40 / €36 ( excludes VAT )

You can download a PDF version for your personal record.

Buy this article

How to Create a Research Poster

- Poster Basics

- Design Tips

- Logos & Images

What is a Research Poster?

Posters are widely used in the academic community, and most conferences include poster presentations in their program. Research posters summarize information or research concisely and attractively to help publicize it and generate discussion.

The poster is usually a mixture of a brief text mixed with tables, graphs, pictures, and other presentation formats. At a conference, the researcher stands by the poster display while other participants can come and view the presentation and interact with the author.

What Makes a Good Poster?

- Important information should be readable from about 10 feet away

- Title is short and draws interest

- Word count of about 300 to 800 words

- Text is clear and to the point

- Use of bullets, numbering, and headlines make it easy to read

- Effective use of graphics, color and fonts

- Consistent and clean layout

- Includes acknowledgments, your name and institutional affiliation

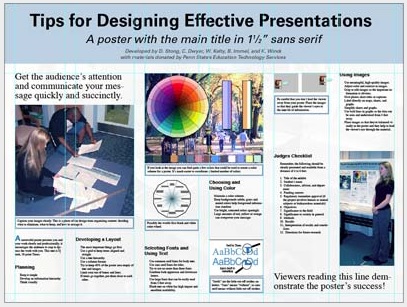

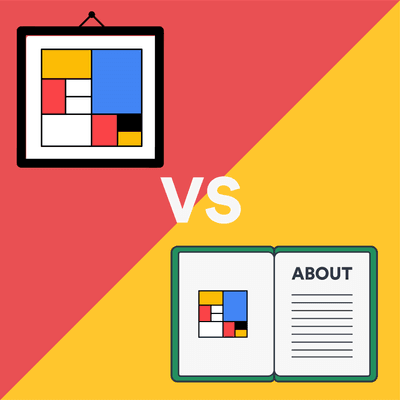

A Sample of a Well Designed Poster

View this poster example in a web browser .

Image credit: Poster Session Tips by [email protected], via Penn State

Where do I begin?

Answer these three questions:.

- What is the most important/interesting/astounding finding from my research project?

- How can I visually share my research with conference attendees? Should I use charts, graphs, photos, images?

- What kind of information can I convey during my talk that will complement my poster?

What software can I use to make a poster?

A popular, easy-to-use option. It is part of Microsoft Office package and is available on the library computers in rooms LC337 and LC336. ( Advice for creating a poster with PowerPoint ).

Adobe Illustrator, Photoshop, and InDesign

Feature-rich professional software that is good for posters including lots of high-resolution images, but they are more complex and expensive. NYU Faculty, Staff, and Students can access and download the Adobe Creative Suite .

Open Source Alternatives

- OpenOffice is the free alternative to MS Office (Impress is its PowerPoint alternative).

- Inkscape and Gimp are alternatives to Adobe products.

- For charts and diagrams try Gliffy or Lovely Charts .

- A complete list of free graphics software .

A Sample of a Poorly Designed Poster

View this bad poster example in a browser.

Image Credit: Critique by Better Posters

- Next: Design Tips >>

- Last Updated: Jul 11, 2023 5:09 PM

- URL: https://guides.nyu.edu/posters

NCURA.edu | Contact Us |

- Registration Pricing

- Bulk Registration Packages

- Conference and Pre-Conference Workshop Cancellation Policy

- A Personal Welcome

- About the Conference

- Pre-Conference Workshops

- Certificate Program

- CPE/CEU Information

Guide to Writing A Poster Abstract

- Exhibitor Registration

Poster abstracts submitted to NCURA should serve as the initial report of knowledge, experience, or best practices in the field of research Administration. Submissions are evaluated by a review committee.

A well-written abstract is more likely to be considered as a finalist and, ultimately, for a recognition award. To expedite the review process, to assure effective communication, and to elevate the work toward the recognition award following, the following general suggestions will be helpful in submitting your abstract and description.

General suggestions

- Check for proper spelling and grammar.

- Use a standard typeface, such as Times Roman with a font size of 12.

- It is important to keep nonstandard abbreviations/acronyms to a minimum, to allow for readability and understanding.

- Do not include tables, figures, or graphs in the abstract. Such content is appropriate for the poster.

- Abstract should be 250 words or less and should summarize the overall objectives being presented in the poster. This can be included in bullet point format if preferred.

- The application should include a detailed description of poster make up itself and include the outcomes to be presented. Limit to 500 words (use the less=more concept).

- Try to organize the abstract with the following headings where appropriate, as explained below; purpose, methods, results, conclusions.

The abstract title conveys the content/subject of the poster. The title may be written as a question or the title may be written to suggest the conclusions, if appropriate. A short concise title may more easily catch a reader’s attention. Try to not use abbreviations or acronyms in titles.

The introductory sentence(s) may be stated as a hypothesis, a purpose, an objective, or as current evidence for a finding. Hypothesis is a supposition or conjecture used as a basis for further investigations. Purpose is a statement of the reason for conducting a project or reporting on a program, process or activity. Objective is the result that the author is trying to achieve by conducting a project, program, process or activity.

Briefly describe the methods of the project to define the data or population, outcome variables, and analytic techniques, as well as data collection procedures and frequencies. A description of statistical methods used may be included if appropriate.

The results should be stated succinctly to support only the purpose, objectives, hypothesis, or conclusions.

Conclusions

The conclusion(s) should highlight the impact of the project, and follow the methods and results in a logical fashion. This section should not restate results. Rather, the utility of the results and their potential role in the management of the project should be emphasized. New information or conclusions not supported by data in the results section should be avoided.

Important note

Poster program finalists are determined following evaluation of each actual poster by the review committee. Finalists will be notified by email no later than June 25th.

CONFERENCE PROGRAM

Registration information, workshop information, registration options, frequently asked questions, exhibitor information.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Palliat Med

Writing Abstracts and Developing Posters for National Meetings

Gordon j. wood.

1 Department of Medicine, Section of Palliative Care and Medical Ethics, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

R. Sean Morrison

2 Department of Geriatrics and Palliative Medicine, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, New York, and the James J. Peters VA, Bronx, New York.

Presenting posters at national meetings can help fellows and junior faculty members develop a national reputation. They often lead to interesting and fruitful networking and collaboration opportunities. They also help with promotion in academic medicine and can reveal new job opportunities. Practically, presenting posters can help justify funding to attend a meeting. Finally, this process can be invaluable in assisting with manuscript preparation. This article provides suggestions and words of wisdom for palliative care fellows and junior faculty members wanting to present a poster at a national meeting describing a case study or original research. It outlines how to pick a topic, decide on collaborators, and choose a meeting for the submission. It also describes how to write the abstract using examples that present a general format as well as writing tips for each section. It then describes how to prepare the poster and do the presentation. Sample poster formats are provided as are talking points to help the reader productively interact with those that visit the poster. Finally, tips are given regarding what to do after the meeting. The article seeks to not only describe the basic steps of this entire process, but also to highlight the hidden curriculum behind the successful abstracts and posters. These tricks of the trade can help the submission stand out and will make sure the reader gets the most out of the hard work that goes into a poster presentation at a national meeting.

Introduction

A track record of successful presentations at national meetings is important for the junior academic palliative medicine clinician. Unfortunately, palliative care fellows report minimal training in how to even start the process by writing the abstract. 1 What follows is a practical, step-by-step guide aimed at the palliative care fellow or junior palliative care faculty member who is hoping to present original research or a case study at a national meeting. We will discuss the rationale for presenting at national meetings, development of the abstract, creation and conduct of the presentation, as well as what to do after the meeting. We will draw on the literature where available 2 – 7 and on our experience where data are lacking. We will focus on the development of posters rather than oral presentations or workshops as these are typically the first and more common experiences for junior faculty and fellows. Finally, in addition to discussing the nuts and bolts of the process, we will also focus on the “hidden curriculum” behind the successful submissions and poster presentations (see Table 1 ).

The Hidden Curriculum: Tips To Get the Most Out of Your Submission

| • Choose the right meeting for the submission |

| ∘ Will the audience be interested? |

| ∘ Is there a theme to the meeting and does my project/case fit with that theme? |

| ∘ Has my mentor attended/presented at the meeting and what is his/her advice? |

| ∘ Where will the information have the most impact? |

| ∘ Which meeting will provide the best networking/collaborating opportunities? |

| ∘ Which meeting will best help advance my career? |

| ∘ Will my research be completed in time for the abstract deadline? Conversely, will the abstract deadline serve as an incentive to help move my research along? |

| • Use all available resources |

| ∘ Look at accepted abstracts from last year. |

| ∘ Seek feedback on your abstract and poster from people who have not been primarily involved in the project and ideally have presented at the meeting to which you are submitting. |

| ∘ See if your institution has a required poster template or ask a colleague for the electronic version of his/her poster so you do not have to generate your template from scratch. |

| ∘ Before your poster presentation, have your mentor contact important people in the field and ask them to come by your poster. Know who they are, when they are coming, and have questions prepared. Suggest these people as reviewers when you submit your manuscript. |

| • Talking points for a poster presentation |

| ∘ Do you have any questions? |

| ∘ Do you see any flaws in my methods? |

| ∘ Do my conclusions make sense? |

| ∘ Specific questions targeted at the people contacted by your mentor |

| • After the presentation |

| ∘ Contact anyone who requested more information or wanted to collaborate. |

| ∘ Double-dip wherever possible by using charts and figures in talks, etc. |

| ∘ Write it up for publication! |

Why Present at National Meetings?

Given that it takes a fair amount of work to put together an abstract and presentation, it is fair to ask what is to be gained from the effort. The standard answer is that presentations at national meetings aid in the dissemination of your findings and help further the field. Although this is certainly true, there are also several practical and personal reasons that should hold at least equal importance to fellows or junior faculty members (see Table 2 ). Perhaps most importantly, presenting at a national meeting helps develop your national reputation. People will begin to know your name and associate it with the topic you are presenting. Additionally, it provides an opportunity to network and collaborate, which can then lead to other projects. Many of us have begun life-long collaborative relationships after connecting with someone at a national meeting. Even if you don't make a personal connection at the meeting, if people begin to associate your name with a topic, they will often reach out to you when they need an expert to sit on a committee, write a paper, or collaborate on a project.

Personal Reasons To Present Abstracts/Posters

| • Develop your national reputation |

| • Associate your name with a topic |

| • Network and collaborate |

| • Job promotion |

| • Find new jobs |

| • Obtain funding to attend the meeting |

| • Help with manuscript preparation |

| ∘ Forces organization of your thoughts |

| ∘ Gives you a deadline |

| ∘ Gives you feedback before manuscript submission to shape analyses, interpretation, and future research directions |

Development of a national reputation is important not only in garnering interesting opportunities, but it is also key to career advancement. For fellows, presenting at national meetings can forge connections with future employers and lead to that all-important “first job.” For junior faculty, demonstration of a national reputation is often the main criterion for promotion and presentations at national meetings help establish this reputation. 8 Junior faculty may also make connections that lead to potential job opportunities of which they might not otherwise have been aware.

There are three additional practical reasons to present at a national meeting. First, having something accepted for presentation is often the only way your department will reimburse your trip to the meeting. Second, going through the work of abstract submission and presentation helps tremendously in manuscript preparation. It provides a deadline and forces you to organize your thoughts, analyze your data, and place them in an understandable format. This makes the eventual job of writing the manuscript much less daunting. Third, presenting also allows you to get immediate feedback, which can then make the manuscript stronger before it is submitted. Such feedback often gives the presenter additional ideas for analyses, alternate explanations for findings, and ideas regarding future directions.

Although these personal and practical reasons for presenting are derived from our own experiences, they are concordant with the survey results of 219 presenters at the Society of General Internal Medicine Annual Meeting. 9 This survey also highlighted how posters and oral presentations can meet these needs differently. For example, for these presenters, posters were preferred for getting feedback and criticism and for networking and collaborating. Oral presentations, on the other hand, were preferred for developing a national reputation and sharing important findings most effectively. For all of these reasons, many academic centers have developed highly effective programs for trainees and junior faculty to help encourage submissions 10 , 11 so it is wise to seek out such programs if they exist in your home institution.

Getting Started

Realizing the importance of presenting at national meetings may be the easy part. Actually getting started and putting together a submission is where most fall short. The critical first step is to pick something that interests you. For original research, hopefully your level of interest was a consideration at the beginning of the project, although how anxious you are to work on the submission may be a good barometer for your true investment in the project.

For case studies, make sure the topic, and ideally the case, fuel a passion. Unlike original research, in which mentors and advisors are usually established at study conception, case studies often require you to seek appropriate collaborators when contemplating submission. It is the rare submission that comes from a single author. In choosing collaborators, look for a senior mentor with experience submitting posters and an investment in both you and the topic. There is nothing more disheartening for the junior clinician than having to harass a mentor whose heart is not in the project.

Another critical step is to choose the right meeting for the submission. Although many submissions may be to palliative care meetings (e.g., American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine), there is great benefit to both the field and your career in presenting at other specialty meetings. Presentations at well-recognized nonpalliative care meetings further legitimize the field, increase your national visibility, and lead to interesting and fruitful collaborations. Additionally, these types of presentations may be looked on with more favor by people reviewing your CV who are not intimately familiar with the world of palliative care. Table 1 presents some questions you should discuss with your mentor and ask yourself when choosing a meeting. Some of these questions may have conflicting answers, and you should be thoughtful in weighing what is most important.

Once you have chosen your meeting, go to the meeting's website and review all of the instructions. Check requirements regarding what material can be presented. For example, many meetings will allow you to present data that were already presented at a regional meeting but not data that were previously presented at another national meeting. Most meetings also do not allow you to present data that are already published, although it is generally acceptable to submit your abstract at the same time you submit your paper for publication. If the paper is published before the meeting, make sure to inform the committee—most often you will still be able to present but will be asked to note the publication in your presentation. Regarding the submission, most conferences have very specific instructions and the rules are strict. The applications are generally online with preset fields and word limits. It is helpful to examine review criteria and deadlines for submission, paying particular attention to time zones. Finally, it can be invaluable to read published abstracts from the last meeting and to talk with prior presenters to get a sense of the types of abstracts that are accepted.

The next step is to start writing. The key to success is to leave enough time as there are often unavoidable and unplanned technical issues with the online submission that you will confront. Additionally, you will want to leave time to get input from all of the authors and from people who have not been primarily involved in the project—to make sure that a “naïve” audience understands the message of the abstract. Finally, remember that an abstract/poster does not have to represent all of the data for a study and can just present an interesting piece of the story.

Most submissions require several rewrites. These can become frustrating, but it is important to realize that there is a very specific language for these types of submissions that your mentor should know and that you will learn over time. The most common issue is the need to shorten the abstract to fit the word limit. Strategies to ensure brevity include using the active voice, employing generic rather than trade names for drugs and devices, and avoiding jargon and local lingo. Use no more than two or three abbreviations and always define the abbreviations on first use. Do a spelling/grammar check and also have someone proofread the document before submitting. References are generally not included on abstracts. Most importantly, be concise, write lean, and avoid empty phrases such as “studies show.” A review of 45 abstracts submitted to a national surgical meeting found that concise abstracts were more likely to be accepted, 12 and this small study certainly reflects our experiences as submitters and reviewers.

The Abstract for an Original Research Study

The styles of abstracts for original studies vary. Guidelines exist for manuscript abstracts reporting various types of original research (CONSORT, 13 – 15 IDCRD, 16 PRISMA, 17 QUOROM, and STROBE 18 ) and review of these guidelines can be helpful to provide a format. There are also guidelines that exist for evaluating conference abstracts that may be informative, such as the CORE-14 guidelines for observational studies. 19 In general, a structured abstract style is favored. 20 – 21 In this paper, we will present general styles for each type of abstract that will need to be adapted to the type of study and the rules of the conference. Table 3 outlines the general format for an abstract for original research. Each section contains tips for how to write the section, rather than example text from a study. Therefore, you may find it most helpful to review the figures alongside examples of previously accepted abstracts.

Abstract for an Original Research Study

| 10–12 words describing what was investigated and how |

| : The most involved is first with the most senior last. Only include affiliations relevant to the project. Disclosures are often included here as well. |

| This section describes your learning objectives. These are measurable behaviors that the learner should be able to perform after reviewing your poster. For a poster describing a study of the side effects of haloperidol when used as an antiemetic, an objective may be: Describe the two most common adverse effects of haloperidol when used as an antiemetic in home hospice patients. |

| Only include background that is relevant to why you did the study. Avoid general background statements such as “Heart disease is the number one cause of death in America.” Instead, focus on clearly describing the hole in the research that this study fills. |

| These are the specific aims of your study. This section may also include hypotheses. Sometimes this information is included at the end of the introduction/background. |

| This section explains the study design, the population and how it was sampled, the context of the study, and the measurements that were made. Different types of trials will require different information. For example, the CONSORT criteria for reporting randomized controlled trials require: participants, interventions, objective, outcome, randomization, blinding. |

| This is where you present what you found so there is a temptation to include everything. It is generally better to present only relevant data, including the primary outcome (even if negative), key secondary outcomes, and significant adverse events. Relevant statistics such as odds ratios, confidence intervals, and values for key outcomes should be included. Avoid discussing results that “trend toward significance.” Some conferences will allow a table/figure as part of the abstract, although this is rare and should only be done if the data cannot be conveyed otherwise and if the table/figure is legible when reduced in size. The CONSORT criteria for randomized trials suggest including: numbers randomized, recruitment, numbers analyzed, outcome, and harms. |

| This should be a brief description of the main outcome of the study. The key here is to not overstate your findings by inferring anything that is not directly supported by your data. |

| This should be a brief discussion of how the research will impact clinical practice, health care policy, or subsequent research. Again, the key here is to avoid overstating your results. |

In any abstract, it is particularly important to focus on the title as it is often the only item people will look at while scanning the meeting program or wandering through the poster session. It should be no more than 10–12 words 2 and should describe what was investigated and how, instead of what was found. It should be engaging, but be cautious with too much use of humor as this can become tiresome and distracting. Below the title, list authors and their affiliations. The remaining sections of the abstract are discussed in the figure.

The Abstract for a Case Study

The abstract for a case study contains many of the same elements as the abstract for original research with a few important differences. Most importantly, you need to use the abstract to highlight the importance of the issue the case raises and convince the reader that both the case and the issue are interesting, novel, and relevant. A general format is provided in Table 4 .

Abstract for a Case Study

| Should be engaging but should also clearly describe the issue the case raises |

| The most involved is first with the most senior last. Only include affiliations relevant to the project. Disclosures are often included here as well. |

| This section describes the learning objectives you have for presenting the case. These are measurable behaviors that the learner should be able to perform after reviewing your poster. For example, for a poster about prognosticating in congestive heart failure, an objective may be: Describe two key prognostic indicators in advanced heart failure. |

| This is similar to the background in an abstract for original research in that it should be concise and only present information immediately relevant to the topic at hand. The difference here is that you are presenting the topic that the case addresses with the goal of highlighting its importance and relevance to the reader. This section is often ended with a statement specifically stating why the case is being presented. Occasionally, the guidelines may ask that this statement is separated out from the section. |

| The most common mistake is to present too much information in this section. This is generally written in paragraph form (i.e., not separated out into chief complaint, history of present illness, etc.) starting with age, gender, and race (if important). Other than these standard identifiers, the case description should only contain information relevant to the point you are trying to make by presenting this case. For example, there is probably not a good reason to include information about family history in a case highlighting a novel antiemetic. As with all sections, brevity is key. |

| This should highlight the take-home point brought up by the case. A discussion of the relevance of the issue discussed, including future research needs, implications, etc., is generally included, although be careful to not overstate your conclusions. |

Preparing Posters

Once the abstract is prepared, submitted, and, hopefully, accepted, your next job is to prepare the presentation. Whereas a few select abstracts are typically selected for oral presentation (usually 8–10 minutes followed by a short question-and-answer period), the majority of submitted abstracts will be assigned to poster sessions. (Readers interested in advice for oral presentations are referred to reference 22 ). Posters are large (generally approximately 3 × 6 ft) visual representations of your work. Most posters are now one-piece glossy prints from graphics departments or commercial stores, although increasingly academic departments have access to printing facilities that may be less expensive than commercial stores. Additionally, many meetings now partner with on-site printing services, which are convenient and reasonably priced. Generally, the material is prepared on a PowerPoint (or equivalent) slide and this is given to the production facility. The easiest way to prepare your first poster is to ask your institution if it has a preferred or required template. If such a template does not exist, ask for a trusted colleague's slide from an accepted poster. This gives you the format and institutional logos, and you simply need to modify the content. In preparing your poster for printing, review the meeting instructions and try to make your poster as close to the maximum dimensions as possible. Try to complete the poster early to allow for production delays. Consider shipping your poster to the conference or carry it in a protective case and check with the airline regarding luggage requirements. On-site printing eliminates travel hassles but does not allow much time for any problems that may arise.

What goes on the poster?

Both the content and the visual appeal of the poster are important. In fact, one study found that visual appeal was more important than content for knowledge transfer. 23 Although the poster expands the content of your abstract, resist the urge to include too much information. It is helpful to remember the rule of 10s: the average person scans your poster for 10 seconds from 10 feet away. When someone stops, you should be able to introduce your poster in 10 seconds and they should be able to assimilate all of the information and discuss it with you in 10 minutes. 3 Figures 1 and and2 2 show the layouts of posters for a case and for an original study. The general rule is to keep each section as short and simple as possible, which allows for a font large enough (nothing smaller than 24 point 4 ) for easy reading of the title from 10 feet away and the text from 3–5 feet away. Leave blank space and use colors judiciously. Easily read and interpretable figures and simple tables are more visually appealing than text, and they are typically more effective in getting one's message across. It is helpful to get feedback on one's poster before finalizing and printing—ideally from people not familiar with the work to get a true objective view.

Poster for original research.

Poster for case study.

Although it may seem simple enough to prepare a good poster, many fall short. One author reviewed 142 posters at a national meeting and found that 33% were cluttered or sloppy, 22% had fonts that were too small to be easily read, and 38% had research objectives that could not be located in a 1-minute review. 5 Another study of an evaluation tool for case report posters found that the areas most needing improvement were statements of learning objectives, linkages of conclusions to learning objectives, and appropriate amount of words. 24

The Poster Presentation

Posters are presented at “Poster Sessions,” which are designated periods during the meeting when presenters stand by their posters while conference attendees circulate through the room. Refreshments are often served during these sessions and the atmosphere is generally more relaxed and less stressful than during oral presentations. Additionally, the one-on-one contact allows greater opportunity for discussion, feedback, and networking. Awards are often presented to the best posters and ribbons may designate these posters during the session.

The first step to a successful poster presentation is to simply show up. Surveys of conference attendees clearly indicate that it is necessary for the presenter to be with his/her poster for effective communication of the results. 23 This is also your time to grow your reputation, network, and get feedback, so do not miss the opportunity to reap the rewards of your hard work. In preparation, read any specific conference instructions and bring business cards and handouts of the poster or related materials. While standing at your poster, make eye contact with people who approach but allow them to finish reading before beginning a discussion. 4 As noted above, you should be prepared to introduce your poster in 10 seconds then answer questions and discuss as needed. Practicing your introduction and answers to common questions with colleagues before the meeting can be invaluable. Before your presentation, your mentor should also contact important people in the field related to your topic and ask them to come by your poster. You should have a list of these people and know who they are and when they are coming. Standard questions you may ask are included in Table 1 . You should also have prepared questions targeted specifically for each of the people your mentor has contacted. You should then suggest these people as reviewers when you submit your manuscript.

After the Presentation

After the presentation, key steps remain to get the most out of the process. First, ask for feedback so you can make adjustments for the next presentation. Also, think about what parts of the poster you can use for other reasons. It is often helpful to export a graph or figure to use in future presentations. The key is to “double-dip” and use everything to its fullest extent. In addition, to make the maximal use of the networking opportunities you should follow up with anyone who asked for more information or inquired about collaborations. In the excitement of the meeting anything seems possible, but it is easy to lose that momentum when you get home. In one study, only 29% of presenters replied to requests for additional information, and they generally took over 30 days to respond. 25

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, it is critical to write up your work for publication. Although posters are important, publications are the true currency of academia. Unfortunately, the percentage of abstracts that are eventually published is low. 26 When asked why they had yet to publish, respondents in one study 27 cited: lacked time (46%), study still in progress (31%), responsibility for publication belonged to someone else (20%), difficulty with co-authors (17%), and low priority (13%). Factors that have been shown to increase the likelihood of abstract publication include: oral presentation (as opposed to a poster), statistical analysis, number of authors, and university affiliation. 28 – 31 Time to publication is generally about 20 months. 29

Conclusions

Writing abstracts and developing posters for national meetings benefit the field in general and the junior clinician in particular. This process develops critical skills and generates innumerable opportunities. We have presented a stepwise approach based on the literature and our personal experiences. We have also highlighted the hidden curriculum that separates the successful submissions from the rest of the pack. Hopefully, these tools will help palliative care fellows and junior faculty more easily navigate the process and benefit the most from the work they put into their projects.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Morrison is supported by a Mid-Career Investigator Award in Patient Oriented Research from the National Institute on Aging (K24 AG022345). A portion of this work was funded by the National Palliative Care Research Center.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Writing the Poster Abstract

Cite this chapter.

- Peter J. Gosling Ph.D. 2

514 Accesses

The poster abstract is the part of the overall presentation that is usually destined for publication in the proceedings or abstract book of the meeting. Specific skills are required to summarize large amounts of scientific text and data into a few sentences that still adequately set the scene and convey the appropriate message. The abstract is not merely a summary of your findings. It must be able to, and indeed will, stand alone. The restriction on the number of words, the format, and the deadline for receipt will be given by the conference organizers. It is common to supply a box outline in which the abstract must be typed or printed in a camera ready format. This is the lasting part of your presentation, and you need to devote a suitable amount of time to ensuring that it maintains the same high quality as the rest of your presentation. For this reason a good quality copy should be sent for publication, avoiding faxing, as the results are often difficult to read. For casual readers this may be the only part of your presentation that is seen. You should therefore avoid the use of phrases such as “evidence will be presented,” and make the abstract as representative of the whole presentation as possible.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Unable to display preview. Download preview PDF.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Peter Gosling Associates, Staines, UK

Peter J. Gosling Ph.D.

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 1999 Springer Science+Business Media New York

About this chapter

Gosling, P.J. (1999). Writing the Poster Abstract. In: Scientist’s Guide to Poster Presentations. Springer, Boston, MA. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4615-4761-7_4

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4615-4761-7_4

Publisher Name : Springer, Boston, MA

Print ISBN : 978-1-4613-7157-1

Online ISBN : 978-1-4615-4761-7

eBook Packages : Springer Book Archive

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Learn more about how the Cal Poly Humboldt Library can help support your research and learning needs.

Stay updated at Campus Ready .

- Cal Poly Humboldt Library

- Research Guides

Creating a Research Poster

- Creating your poster step by step

- Getting Started

- Citing Images

- Creative Commons Images

- Printing options

- More Resources

Preparing your poster

There are three components to your poster session:

- Your poster

All three components should complement one another, not repeat each other.

Poster: Your poster should be an outline of your research with interesting commentary about what you learned along the way.

You: You should prepare a 10-30 second elevator pitch and a 1-2 minute lightning talk about your research. This should be a unique experience or insight you had about your research that adds depth of understanding to what the attendee can read on your poster.

Handout: Best practices for handouts - Your handout should be double-sided. The first side of the paper should include a picture of your poster (this can be in black and white or color). The second side of the handout should include your literature review, cited references, further information about your topic and your contact information.

Creating your poster by answering 3 questions:

- What is the most important and/or interesting finding from my research project?

- How can I visually share my research with conference attendees? Should I use charts, graphs, images, or a wordcloud?

- What kind of information do I need to share during my lightning talk that will complement my poster?

- *Title (at least 72 pt font).

- Research question or hypothesis (all text should be at least 24 pt font).

- Methodology. What is the research process that you used? Explain how you did your research.

- Your interview questions.

- Observations. What did you see? Why is this important?

- *Findings. What did you learn? Summarize your conclusions.

- Pull out themes in the literature and list in bullet points.

- Consider a brief narrative of what you learned - what was the most interesting/surprising part of your project?

- Interesting quotes from your research.

- Turn your data into charts or tables.

- Use images (visit the "Images" tab in the guide for more information). Take your own or legally use others.

- Recommendations and/or next steps for future research.

- You can include your list of citations on your poster or in your handout.

- *Make sure your name, and Cal Poly Humboldt University is on your poster.

*Required. Everything else is optional - you decide what is important to put on your poster. These are just suggestions. Use the tabs in this guide for more tips on how to create your poster.

Poster Sizes

You can create your poster from scratch by using PowerPoint or a similar design program.

Resize the slide to fit your needs before you begin adding any content. Standard poster sizes range from 40" by 30" and 48" by 36" but you should check with the conference organizers. If you don't resize your design at the beginning, when it is printed the image quality will be poor and pixelated if it is sized up to poster dimensions.

The standard poster sizes for ideaFest are 36" x 48" and 24" by 36".

To resize in PowerPoint, go to "File" then "Page Setup..." and enter your dimensions in the boxes for "width" and "height". Make sure to select "OK" to save your changes.

To resize in Google Slides, go to "File" then "Page setup" and select the "Custom" option in the drop down menu. Enter the dimensions for your poster size and then select "Apply" to save your changes.

Step Four: Final checklist

Final checklist for submitting your poster for printing:.

- Proofread your poster for spelling and grammar mistakes. Ask a peer to read your poster, they will catch the mistakes that you miss. Print your poster on an 8 1/2" by 11" sheet of paper - it is easier to read for mistakes and to judge your design.

- Make sure you followed Step 3 and resized your PPT slide correctly.

- Does your poster have flow? Did you "chunk" information into easily read pieces of information?

- Do your visualizations (e.g. charts, graphs, tag clouds, etc.) tell a story? Are they properly labeled and readable?

- Make sure that your images we not resized in PPT. You should use the original size of the image or try an image editor (e.g. Photoshop). Did you cite your image?

- Is your name, department, and affiliation on your poster?

- Did you want to include acknowlegments on your poster? This may be appropriate if your advisor and a graduate student provided leadership during the research process.

- Most importantly- Save your PPT slide to PDF before you send to the printer in order to avoid any printing mishaps. You should also double-check the properties to make sure it is still sized correctly in PDF.

- << Previous: Getting Started

- Next: Images >>

Reference management. Clean and simple.

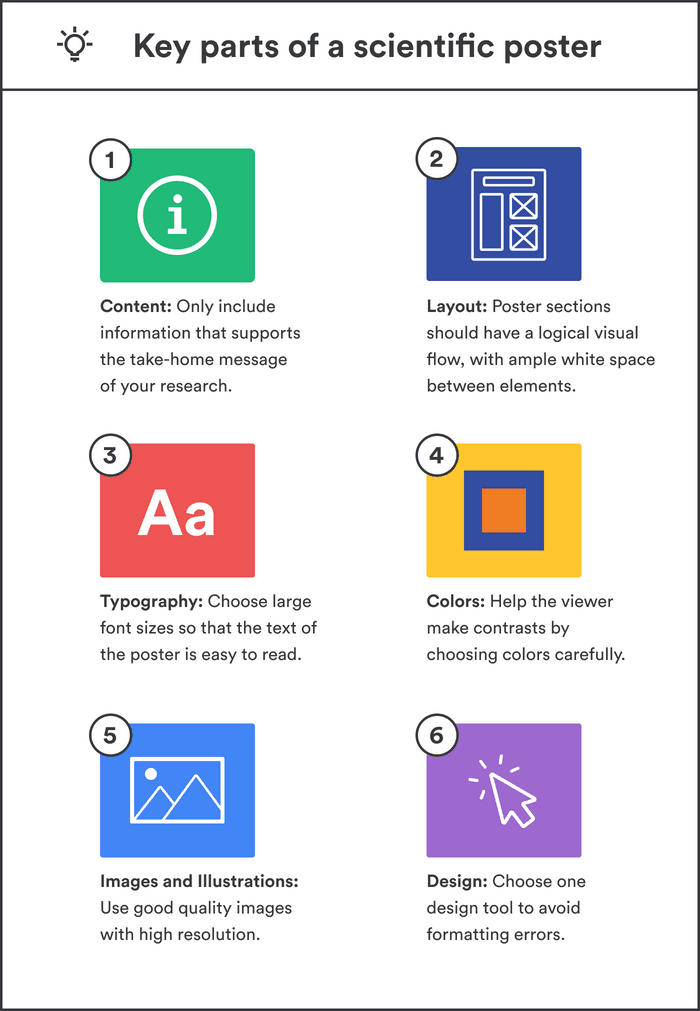

The key parts of a scientific poster

Why make a scientific poster?

Type of poster formats, sections of a scientific poster, before you start: tips for making a scientific poster, the 6 technical elements of a scientific poster, 3. typography, 5. images and illustrations, how to seek feedback on your poster, how to present your poster, tips for the day of your poster presentation, in conclusion, other sources to help you with your scientific poster presentation, frequently asked questions about scientific posters, related articles.

A poster presentation provides the opportunity to show off your research to a broad audience and connect with other researchers in your field.

For junior researchers, presenting a poster is often the first type of scientific presentation they give in their careers.

The discussions you have with other researchers during your poster presentation may inspire new research ideas, or even lead to new collaborations.

Consequently, a poster presentation can be just as professionally enriching as giving an oral presentation , if you prepare for it properly.

In this guide post, you will learn:

- The goal of a scientific poster presentation

- The 6 key elements of a scientific poster

- How to make a scientific poster

- How to prepare for a scientific poster presentation

- ‘What to do on the day of the poster session.

Our advice comes from our previous experiences as scientists presenting posters at conferences.

Posters can be a powerful way for showcasing your data in scientific meetings. You can get helpful feedback from other researchers as well as expand your professional network and attract fruitful interactions with peers.

Scientific poster sessions tend to be more relaxed than oral presentation sessions, as they provide the opportunity to meet with peers in a less formal setting and to have energizing conversations about your research with a wide cross-section of researchers.

- Physical posters: A poster that is located in an exhibit hall and pinned to a poster board. Physical posters are beneficial since they may be visually available for the duration of a meeting, unlike oral presentations.

- E-posters: A poster that is shown on a screen rather than printed and pinned on a poster board. E-posters can have static or dynamic content. Static e-posters are slideshow presentations consisting of one or more slides, whereas dynamic e-posters include videos or animations.

Some events allow for a combination of both formats.

The sections included in a scientific poster tend to follow the format of a scientific paper , although other designs are possible. For example, the concept of a #betterposter was invented by PhD student Mike Morrison to address the issue of poorly designed scientific posters. It puts the take-home message at the center of the poster and includes a QR code on the poster to learn about further details of the project.

| Poster section | Description |

|---|---|

Heading | The title of your research project, and one of the most important features of your poster. Use a specific and informative headline to attract interest from passers-by. Logos for funding agencies and institutions hosting the research project are often placed on either side of the heading. |

Subheading | List of contributing authors, affiliations, and contact details of corresponding author (usually the person presenting the poster). List the authors in the same order as on the publication. |

Introduction | Includes only essential background information as well as the goals of the study. Keep it brief, and use bullet points. The introduction should also highlight the novelty of your research. |

Methods | A chronological order of the steps and techniques used in your project. Include an image or diagram representing your study system if possible. |

Results | Has at most 3 graphs showing the key findings of your study, along with short descriptions. This section should occupy the most space on your poster. |

Conclusion | Summarizes the take-home message of your work. |

References | Includes the key sources used in your study. Have at most 6 references listed. |

Acknowledgments | List funding sources, and contributions from anyone who helped with the research. |

- Anticipate who your audience during the poster session will be—this will depend on the type of meeting. For example, presenting during a poster session at a large conference may attract a broad audience of generalists and specialists at a variety of career stages. You would like for your poster to appeal to all of these groups. You can achieve this by making the main message accessible through eye-catching figures, concise text, and an interesting title.

- Your goal in a poster session is to get your research noticed and to have interesting conversations with attendees. Your poster is a visual aid for the talks you will give, so having a well-organized, clear, and informative poster will help achieve your aim.