Because differences are our greatest strength

Homework anxiety: Why it happens and how to help

By Gail Belsky

Expert reviewed by Jerome Schultz, PhD

Quick tips to help kids with homework anxiety

Quick tip 1, try self-calming strategies..

Try some deep breathing, gentle stretching, or a short walk before starting homework. These strategies can help reset the mind and relieve anxiety.

Quick tip 2

Set a time limit..

Give kids a set amount of time for homework to help it feel more manageable. Try using the “10-minute rule” that many schools use — that’s 10 minutes of homework per grade level. And let kids know it’s OK to stop working for the night.

Quick tip 3

Cut out distractions..

Have kids do homework in a quiet area. Turn off the TV, silence cell phones, and, if possible, limit people coming and going in the room or around the space.

Quick tip 4

Start with the easiest task..

Try having kids do the easiest, quickest assignments first. That way, they’ll feel good about getting a task done — and may be less anxious about the rest of the homework.

Quick tip 5

Use a calm voice..

When kids feel anxious about homework, they might get angry, yell, or cry. Avoid matching their tone of voice. Take a deep breath and keep your voice steady and calm. Let them know you’re there for them.

Sometimes kids just don’t want to do homework. They complain, procrastinate, or rush through the work so they can do something fun. But for other kids, it’s not so simple. Homework may actually give them anxiety.

It’s not always easy to know when kids have homework anxiety. Some kids may share what they’re feeling when you ask. But others can’t yet identify what they’re feeling, or they're not willing to talk about it.

Homework anxiety often starts in early grade school. It can affect any child. But it’s an especially big issue for kids who are struggling in school. They may think they can’t do the work. Or they may not have the right support to get it done.

Keep in mind that some kids may seem anxious about homework but are actually anxious about something else. That’s why it’s important to keep track of when kids get anxious and what they were doing right before. The more you notice what’s happening, the better you can help.

Dive deeper

What homework anxiety looks like.

Kids with homework anxiety might:

Find excuses to avoid homework

Lie about homework being done

Get consistently angry about homework

Be moody or grumpy after school

Complain about not feeling well after school or before homework time

Cry easily or seem overly sensitive

Be afraid of making even small mistakes

Shut down and not want to talk after school

Say “I can’t do it!” before even trying

Learn about other homework challenges kids might be facing .

Why kids get homework anxiety

Kids with homework anxiety are often struggling with a specific skill. They might worry about falling behind their classmates. But there are other factors that cause homework anxiety:

Test prep: Homework that helps kids prepare for a test makes it sound very important. This can raise stress levels.

Perfectionism: Some kids who do really well in a subject may worry that their work “won’t be good enough.”

Trouble managing emotions: For kids who easily get flooded by emotions, homework can be a trigger for anxiety.

Too much homework: Sometimes kids are anxious because they have more work than they can handle.

Use this list to see if kids might have too much homework .

When kids are having homework anxiety, families, educators, and health care providers should work together to understand what’s happening. Start by sharing notes on what you’re seeing and look for patterns . By working together, you’ll develop a clearer sense of what’s going on and how to help.

Parents and caregivers: Start by asking questions to get your child to open up about school . But if kids are struggling with the work itself, they may not want to tell you. You’ll need to talk with your child’s teacher to get insight into what’s happening in school and find out if your child needs help in a specific area.

Explore related topics

Is homework a necessary evil?

After decades of debate, researchers are still sorting out the truth about homework’s pros and cons. One point they can agree on: Quality assignments matter.

By Kirsten Weir

March 2016, Vol 47, No. 3

Print version: page 36

- Schools and Classrooms

Homework battles have raged for decades. For as long as kids have been whining about doing their homework, parents and education reformers have complained that homework's benefits are dubious. Meanwhile many teachers argue that take-home lessons are key to helping students learn. Now, as schools are shifting to the new (and hotly debated) Common Core curriculum standards, educators, administrators and researchers are turning a fresh eye toward the question of homework's value.

But when it comes to deciphering the research literature on the subject, homework is anything but an open book.

The 10-minute rule

In many ways, homework seems like common sense. Spend more time practicing multiplication or studying Spanish vocabulary and you should get better at math or Spanish. But it may not be that simple.

Homework can indeed produce academic benefits, such as increased understanding and retention of the material, says Duke University social psychologist Harris Cooper, PhD, one of the nation's leading homework researchers. But not all students benefit. In a review of studies published from 1987 to 2003, Cooper and his colleagues found that homework was linked to better test scores in high school and, to a lesser degree, in middle school. Yet they found only faint evidence that homework provided academic benefit in elementary school ( Review of Educational Research , 2006).

Then again, test scores aren't everything. Homework proponents also cite the nonacademic advantages it might confer, such as the development of personal responsibility, good study habits and time-management skills. But as to hard evidence of those benefits, "the jury is still out," says Mollie Galloway, PhD, associate professor of educational leadership at Lewis & Clark College in Portland, Oregon. "I think there's a focus on assigning homework because [teachers] think it has these positive outcomes for study skills and habits. But we don't know for sure that's the case."

Even when homework is helpful, there can be too much of a good thing. "There is a limit to how much kids can benefit from home study," Cooper says. He agrees with an oft-cited rule of thumb that students should do no more than 10 minutes a night per grade level — from about 10 minutes in first grade up to a maximum of about two hours in high school. Both the National Education Association and National Parent Teacher Association support that limit.

Beyond that point, kids don't absorb much useful information, Cooper says. In fact, too much homework can do more harm than good. Researchers have cited drawbacks, including boredom and burnout toward academic material, less time for family and extracurricular activities, lack of sleep and increased stress.

In a recent study of Spanish students, Rubén Fernández-Alonso, PhD, and colleagues found that students who were regularly assigned math and science homework scored higher on standardized tests. But when kids reported having more than 90 to 100 minutes of homework per day, scores declined ( Journal of Educational Psychology , 2015).

"At all grade levels, doing other things after school can have positive effects," Cooper says. "To the extent that homework denies access to other leisure and community activities, it's not serving the child's best interest."

Children of all ages need down time in order to thrive, says Denise Pope, PhD, a professor of education at Stanford University and a co-founder of Challenge Success, a program that partners with secondary schools to implement policies that improve students' academic engagement and well-being.

"Little kids and big kids need unstructured time for play each day," she says. Certainly, time for physical activity is important for kids' health and well-being. But even time spent on social media can help give busy kids' brains a break, she says.

All over the map

But are teachers sticking to the 10-minute rule? Studies attempting to quantify time spent on homework are all over the map, in part because of wide variations in methodology, Pope says.

A 2014 report by the Brookings Institution examined the question of homework, comparing data from a variety of sources. That report cited findings from a 2012 survey of first-year college students in which 38.4 percent reported spending six hours or more per week on homework during their last year of high school. That was down from 49.5 percent in 1986 ( The Brown Center Report on American Education , 2014).

The Brookings report also explored survey data from the National Assessment of Educational Progress, which asked 9-, 13- and 17-year-old students how much homework they'd done the previous night. They found that between 1984 and 2012, there was a slight increase in homework for 9-year-olds, but homework amounts for 13- and 17-year-olds stayed roughly the same, or even decreased slightly.

Yet other evidence suggests that some kids might be taking home much more work than they can handle. Robert Pressman, PhD, and colleagues recently investigated the 10-minute rule among more than 1,100 students, and found that elementary-school kids were receiving up to three times as much homework as recommended. As homework load increased, so did family stress, the researchers found ( American Journal of Family Therapy , 2015).

Many high school students also seem to be exceeding the recommended amounts of homework. Pope and Galloway recently surveyed more than 4,300 students from 10 high-achieving high schools. Students reported bringing home an average of just over three hours of homework nightly ( Journal of Experiential Education , 2013).

On the positive side, students who spent more time on homework in that study did report being more behaviorally engaged in school — for instance, giving more effort and paying more attention in class, Galloway says. But they were not more invested in the homework itself. They also reported greater academic stress and less time to balance family, friends and extracurricular activities. They experienced more physical health problems as well, such as headaches, stomach troubles and sleep deprivation. "Three hours per night is too much," Galloway says.

In the high-achieving schools Pope and Galloway studied, more than 90 percent of the students go on to college. There's often intense pressure to succeed academically, from both parents and peers. On top of that, kids in these communities are often overloaded with extracurricular activities, including sports and clubs. "They're very busy," Pope says. "Some kids have up to 40 hours a week — a full-time job's worth — of extracurricular activities." And homework is yet one more commitment on top of all the others.

"Homework has perennially acted as a source of stress for students, so that piece of it is not new," Galloway says. "But especially in upper-middle-class communities, where the focus is on getting ahead, I think the pressure on students has been ratcheted up."

Yet homework can be a problem at the other end of the socioeconomic spectrum as well. Kids from wealthier homes are more likely to have resources such as computers, Internet connections, dedicated areas to do schoolwork and parents who tend to be more educated and more available to help them with tricky assignments. Kids from disadvantaged homes are more likely to work at afterschool jobs, or to be home without supervision in the evenings while their parents work multiple jobs, says Lea Theodore, PhD, a professor of school psychology at the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia. They are less likely to have computers or a quiet place to do homework in peace.

"Homework can highlight those inequities," she says.

Quantity vs. quality

One point researchers agree on is that for all students, homework quality matters. But too many kids are feeling a lack of engagement with their take-home assignments, many experts say. In Pope and Galloway's research, only 20 percent to 30 percent of students said they felt their homework was useful or meaningful.

"Students are assigned a lot of busywork. They're naming it as a primary stressor, but they don't feel it's supporting their learning," Galloway says.

"Homework that's busywork is not good for anyone," Cooper agrees. Still, he says, different subjects call for different kinds of assignments. "Things like vocabulary and spelling are learned through practice. Other kinds of courses require more integration of material and drawing on different skills."

But critics say those skills can be developed with many fewer hours of homework each week. Why assign 50 math problems, Pope asks, when 10 would be just as constructive? One Advanced Placement biology teacher she worked with through Challenge Success experimented with cutting his homework assignments by a third, and then by half. "Test scores didn't go down," she says. "You can have a rigorous course and not have a crazy homework load."

Still, changing the culture of homework won't be easy. Teachers-to-be get little instruction in homework during their training, Pope says. And despite some vocal parents arguing that kids bring home too much homework, many others get nervous if they think their child doesn't have enough. "Teachers feel pressured to give homework because parents expect it to come home," says Galloway. "When it doesn't, there's this idea that the school might not be doing its job."

Galloway argues teachers and school administrators need to set clear goals when it comes to homework — and parents and students should be in on the discussion, too. "It should be a broader conversation within the community, asking what's the purpose of homework? Why are we giving it? Who is it serving? Who is it not serving?"

Until schools and communities agree to take a hard look at those questions, those backpacks full of take-home assignments will probably keep stirring up more feelings than facts.

Further reading

- Cooper, H., Robinson, J. C., & Patall, E. A. (2006). Does homework improve academic achievement? A synthesis of research, 1987-2003. Review of Educational Research, 76 (1), 1–62. doi: 10.3102/00346543076001001

- Galloway, M., Connor, J., & Pope, D. (2013). Nonacademic effects of homework in privileged, high-performing high schools. The Journal of Experimental Education, 81 (4), 490–510. doi: 10.1080/00220973.2012.745469

- Pope, D., Brown, M., & Miles, S. (2015). Overloaded and underprepared: Strategies for stronger schools and healthy, successful kids . San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Letters to the Editor

- Send us a letter

Along with Stanford news and stories, show me:

- Student information

- Faculty/Staff information

We want to provide announcements, events, leadership messages and resources that are relevant to you. Your selection is stored in a browser cookie which you can remove at any time using “Clear all personalization” below.

Education scholar Denise Pope has found that too much homework has negative effects on student well-being and behavioral engagement. (Image credit: L.A. Cicero)

A Stanford researcher found that too much homework can negatively affect kids, especially their lives away from school, where family, friends and activities matter.

“Our findings on the effects of homework challenge the traditional assumption that homework is inherently good,” wrote Denise Pope , a senior lecturer at the Stanford Graduate School of Education and a co-author of a study published in the Journal of Experimental Education .

The researchers used survey data to examine perceptions about homework, student well-being and behavioral engagement in a sample of 4,317 students from 10 high-performing high schools in upper-middle-class California communities. Along with the survey data, Pope and her colleagues used open-ended answers to explore the students’ views on homework.

Median household income exceeded $90,000 in these communities, and 93 percent of the students went on to college, either two-year or four-year.

Students in these schools average about 3.1 hours of homework each night.

“The findings address how current homework practices in privileged, high-performing schools sustain students’ advantage in competitive climates yet hinder learning, full engagement and well-being,” Pope wrote.

Pope and her colleagues found that too much homework can diminish its effectiveness and even be counterproductive. They cite prior research indicating that homework benefits plateau at about two hours per night, and that 90 minutes to two and a half hours is optimal for high school.

Their study found that too much homework is associated with:

* Greater stress: 56 percent of the students considered homework a primary source of stress, according to the survey data. Forty-three percent viewed tests as a primary stressor, while 33 percent put the pressure to get good grades in that category. Less than 1 percent of the students said homework was not a stressor.

* Reductions in health: In their open-ended answers, many students said their homework load led to sleep deprivation and other health problems. The researchers asked students whether they experienced health issues such as headaches, exhaustion, sleep deprivation, weight loss and stomach problems.

* Less time for friends, family and extracurricular pursuits: Both the survey data and student responses indicate that spending too much time on homework meant that students were “not meeting their developmental needs or cultivating other critical life skills,” according to the researchers. Students were more likely to drop activities, not see friends or family, and not pursue hobbies they enjoy.

A balancing act

The results offer empirical evidence that many students struggle to find balance between homework, extracurricular activities and social time, the researchers said. Many students felt forced or obligated to choose homework over developing other talents or skills.

Also, there was no relationship between the time spent on homework and how much the student enjoyed it. The research quoted students as saying they often do homework they see as “pointless” or “mindless” in order to keep their grades up.

“This kind of busy work, by its very nature, discourages learning and instead promotes doing homework simply to get points,” Pope said.

She said the research calls into question the value of assigning large amounts of homework in high-performing schools. Homework should not be simply assigned as a routine practice, she said.

“Rather, any homework assigned should have a purpose and benefit, and it should be designed to cultivate learning and development,” wrote Pope.

High-performing paradox

In places where students attend high-performing schools, too much homework can reduce their time to foster skills in the area of personal responsibility, the researchers concluded. “Young people are spending more time alone,” they wrote, “which means less time for family and fewer opportunities to engage in their communities.”

Student perspectives

The researchers say that while their open-ended or “self-reporting” methodology to gauge student concerns about homework may have limitations – some might regard it as an opportunity for “typical adolescent complaining” – it was important to learn firsthand what the students believe.

The paper was co-authored by Mollie Galloway from Lewis and Clark College and Jerusha Conner from Villanova University.

Media Contacts

Denise Pope, Stanford Graduate School of Education: (650) 725-7412, [email protected] Clifton B. Parker, Stanford News Service: (650) 725-0224, [email protected]

- Future Students

- Current Students

- Faculty/Staff

News and Media

- News & Media Home

- Research Stories

- School's In

- In the Media

You are here

More than two hours of homework may be counterproductive, research suggests.

A Stanford education researcher found that too much homework can negatively affect kids, especially their lives away from school, where family, friends and activities matter. "Our findings on the effects of homework challenge the traditional assumption that homework is inherently good," wrote Denise Pope , a senior lecturer at the Stanford Graduate School of Education and a co-author of a study published in the Journal of Experimental Education . The researchers used survey data to examine perceptions about homework, student well-being and behavioral engagement in a sample of 4,317 students from 10 high-performing high schools in upper-middle-class California communities. Along with the survey data, Pope and her colleagues used open-ended answers to explore the students' views on homework. Median household income exceeded $90,000 in these communities, and 93 percent of the students went on to college, either two-year or four-year. Students in these schools average about 3.1 hours of homework each night. "The findings address how current homework practices in privileged, high-performing schools sustain students' advantage in competitive climates yet hinder learning, full engagement and well-being," Pope wrote. Pope and her colleagues found that too much homework can diminish its effectiveness and even be counterproductive. They cite prior research indicating that homework benefits plateau at about two hours per night, and that 90 minutes to two and a half hours is optimal for high school. Their study found that too much homework is associated with: • Greater stress : 56 percent of the students considered homework a primary source of stress, according to the survey data. Forty-three percent viewed tests as a primary stressor, while 33 percent put the pressure to get good grades in that category. Less than 1 percent of the students said homework was not a stressor. • Reductions in health : In their open-ended answers, many students said their homework load led to sleep deprivation and other health problems. The researchers asked students whether they experienced health issues such as headaches, exhaustion, sleep deprivation, weight loss and stomach problems. • Less time for friends, family and extracurricular pursuits : Both the survey data and student responses indicate that spending too much time on homework meant that students were "not meeting their developmental needs or cultivating other critical life skills," according to the researchers. Students were more likely to drop activities, not see friends or family, and not pursue hobbies they enjoy. A balancing act The results offer empirical evidence that many students struggle to find balance between homework, extracurricular activities and social time, the researchers said. Many students felt forced or obligated to choose homework over developing other talents or skills. Also, there was no relationship between the time spent on homework and how much the student enjoyed it. The research quoted students as saying they often do homework they see as "pointless" or "mindless" in order to keep their grades up. "This kind of busy work, by its very nature, discourages learning and instead promotes doing homework simply to get points," said Pope, who is also a co-founder of Challenge Success , a nonprofit organization affiliated with the GSE that conducts research and works with schools and parents to improve students' educational experiences.. Pope said the research calls into question the value of assigning large amounts of homework in high-performing schools. Homework should not be simply assigned as a routine practice, she said. "Rather, any homework assigned should have a purpose and benefit, and it should be designed to cultivate learning and development," wrote Pope. High-performing paradox In places where students attend high-performing schools, too much homework can reduce their time to foster skills in the area of personal responsibility, the researchers concluded. "Young people are spending more time alone," they wrote, "which means less time for family and fewer opportunities to engage in their communities." Student perspectives The researchers say that while their open-ended or "self-reporting" methodology to gauge student concerns about homework may have limitations – some might regard it as an opportunity for "typical adolescent complaining" – it was important to learn firsthand what the students believe. The paper was co-authored by Mollie Galloway from Lewis and Clark College and Jerusha Conner from Villanova University.

Clifton B. Parker is a writer at the Stanford News Service .

More Stories

⟵ Go to all Research Stories

Get the Educator

Subscribe to our monthly newsletter.

Stanford Graduate School of Education

482 Galvez Mall Stanford, CA 94305-3096 Tel: (650) 723-2109

- Contact Admissions

- GSE Leadership

- Site Feedback

- Web Accessibility

- Career Resources

- Faculty Open Positions

- Explore Courses

- Academic Calendar

- Office of the Registrar

- Cubberley Library

- StanfordWho

- StanfordYou

Improving lives through learning

- Stanford Home

- Maps & Directions

- Search Stanford

- Emergency Info

- Terms of Use

- Non-Discrimination

- Accessibility

© Stanford University , Stanford , California 94305 .

- Child Program

- Adult Program

- At-Home Program

Take the Quiz

Find a Center

- Personalized Plans

- International Families

- Learning Disorders

- Processing Disorders

- Oppositional Defiant Disorder

- Autism Spectrum Disorder

- Behavioral Issues

- Struggling Kids

- Testimonials

The Science Behind Brain Balance

- How It Works

End Homework Anxiety: Stress-Busting Techniques for Your Child

Sometimes kids dread homework because they'd rather be outside playing when they're not at school. But, sometimes a child's resistance to homework is more intense than a typical desire to be having fun, and it can be actually be labeled as homework anxiety: a legitimate condition suffered by some students who feel intense feelings of fear and dread when it comes to doing homework. Read on to learn about what homework anxiety is and whether your child may be suffering from it.

What is Homework Anxiety?

Homework anxiety is a condition in which students stress about and fear homework, often causing them to put homework off until later . It is a self-exacerbating condition because the longer the student puts off the homework, the more anxiety they feel about it, and the more pressure they experience to finish the work with less time. Homework anxiety can cripple some kids who are perfectly capable of doing the work, causing unfinished assignments and grades that slip.

What Causes Homework Anxiety?

There are many causes of homework anxiety, and there can be multiple factors spurring feelings of fear and stress. Some common causes of homework anxiety include:

- Other anxiety issues: Students who tend to suffer anxiety and worry, in general, can begin to associate anxiety with their homework, as well.

- Fear of testing: Often, homework is associated with upcoming tests and quizzes, which affect grades. Students can feel pressure related to being "graded" and avoid homework since it feels weighty and important.

- General school struggle: When students are struggling in school or with grades, they may feel a sense of anxiety about learning and school in general.

- Lack of support: Without a parent, sibling, tutor, or other help at home, students may feel that they won't have the necessary support to complete an assignment.

- Perfectionism: Students who want to perform perfectly in school may get anxious about completing a homework assignment perfectly and, in turn, procrastinate.

Basic Tips for Helping with Homework Anxiety

To help your child with homework anxiety, there are a few basic tips to try. Set time limits for homework, so that students know there is a certain time of the day when they must start and finish assignments. This helps them avoid putting off homework until it feels too rushed and pressured. Make sure your student has support available when doing their work, so they know they'll be able to ask for help if needed. Teaching your child general tips to deal with anxiety can also help, like deep breathing, getting out to take a short walk, or quieting racing thoughts in their mind to help them focus.

How can the Brain Balance Program Help with Homework Anxiety?

Extensive scientific research demonstrates that the brain is malleable, allowing for brain connectivity change and development and creating an opportunity for improvement at any age. Brain Balance has applied this research to develop a program that focuses on building brain connectivity and improving the foundation of development, rather than masking or coping with symptoms.

If you have a child or a teenager who struggles with homework anxiety, an assessment can help to identify key areas for improvement and create an action plan for you and your child. To get started, take our quick, free online assessment by clicking the link below.

Get started with a plan for your child today.

Related posts, thinking of homeschooling five key factors to consider..

By Steve Kozak

ADD vs. ADHD: What's The Difference?

Of course, you love your child. You just wish they would slow down for just one minute. Maybe they […]

By Dr. Rebecca Jackson

Call us at 800.877.5500

Webinar Sign Up

Call 800-877-5500

When Is Homework Stressful? Its Effects on Students’ Mental Health

Are you wondering when is homework stressful? Well, homework is a vital constituent in keeping students attentive to the course covered in a class. By applying the lessons, students learned in class, they can gain a mastery of the material by reflecting on it in greater detail and applying what they learned through homework.

However, students get advantages from homework, as it improves soft skills like organisation and time management which are important after high school. However, the additional work usually causes anxiety for both the parents and the child. As their load of homework accumulates, some students may find themselves growing more and more bored.

Students may take assistance online and ask someone to do my online homework . As there are many platforms available for the students such as Chegg, Scholarly Help, and Quizlet offering academic services that can assist students in completing their homework on time.

Negative impact of homework

There are the following reasons why is homework stressful and leads to depression for students and affect their mental health. As they work hard on their assignments for alarmingly long periods, students’ mental health is repeatedly put at risk. Here are some serious arguments against too much homework.

No uniqueness

Homework should be intended to encourage children to express themselves more creatively. Teachers must assign kids intriguing assignments that highlight their uniqueness. similar to writing an essay on a topic they enjoy.

Moreover, the key is encouraging the child instead of criticizing him for writing a poor essay so that he can express himself more creatively.

Lack of sleep

One of the most prevalent adverse effects of schoolwork is lack of sleep. The average student only gets about 5 hours of sleep per night since they stay up late to complete their homework, even though the body needs at least 7 hours of sleep every day. Lack of sleep has an impact on both mental and physical health.

No pleasure

Students learn more effectively while they are having fun. They typically learn things more quickly when their minds are not clouded by fear. However, the fear factor that most teachers introduce into homework causes kids to turn to unethical means of completing their assignments.

Excessive homework

The lack of coordination between teachers in the existing educational system is a concern. As a result, teachers frequently end up assigning children far more work than they can handle. In such circumstances, children turn to cheat on their schoolwork by either copying their friends’ work or using online resources that assist with homework.

Anxiety level

Homework stress can increase anxiety levels and that could hurt the blood pressure norms in young people . Do you know? Around 3.5% of young people in the USA have high blood pressure. So why is homework stressful for children when homework is meant to be enjoyable and something they look forward to doing? It is simple to reject this claim by asserting that schoolwork is never enjoyable, yet with some careful consideration and preparation, homework may become pleasurable.

No time for personal matters

Students that have an excessive amount of homework miss out on personal time. They can’t get enough enjoyment. There is little time left over for hobbies, interpersonal interaction with colleagues, and other activities.

However, many students dislike doing their assignments since they don’t have enough time. As they grow to detest it, they can stop learning. In any case, it has a significant negative impact on their mental health.

Children are no different than everyone else in need of a break. Weekends with no homework should be considered by schools so that kids have time to unwind and prepare for the coming week. Without a break, doing homework all week long might be stressful.

How do parents help kids with homework?

Encouraging children’s well-being and health begins with parents being involved in their children’s lives. By taking part in their homework routine, you can see any issues your child may be having and offer them the necessary support.

Set up a routine

Your student will develop and maintain good study habits if you have a clear and organized homework regimen. If there is still a lot of schoolwork to finish, try putting a time limit. Students must obtain regular, good sleep every single night.

Observe carefully

The student is ultimately responsible for their homework. Because of this, parents should only focus on ensuring that their children are on track with their assignments and leave it to the teacher to determine what skills the students have and have not learned in class.

Listen to your child

One of the nicest things a parent can do for their kids is to ask open-ended questions and listen to their responses. Many kids are reluctant to acknowledge they are struggling with their homework because they fear being labelled as failures or lazy if they do.

However, every parent wants their child to succeed to the best of their ability, but it’s crucial to be prepared to ease the pressure if your child starts to show signs of being overburdened with homework.

Talk to your teachers

Also, make sure to contact the teacher with any problems regarding your homework by phone or email. Additionally, it demonstrates to your student that you and their teacher are working together to further their education.

Homework with friends

If you are still thinking is homework stressful then It’s better to do homework with buddies because it gives them these advantages. Their stress is reduced by collaborating, interacting, and sharing with peers.

Additionally, students are more relaxed when they work on homework with pals. It makes even having too much homework manageable by ensuring they receive the support they require when working on the assignment. Additionally, it improves their communication abilities.

However, doing homework with friends guarantees that one learns how to communicate well and express themselves.

Review homework plan

Create a schedule for finishing schoolwork on time with your child. Every few weeks, review the strategy and make any necessary adjustments. Gratefully, more schools are making an effort to control the quantity of homework assigned to children to lessen the stress this produces.

Bottom line

Finally, be aware that homework-related stress is fairly prevalent and is likely to occasionally affect you or your student. Sometimes all you or your kid needs to calm down and get back on track is a brief moment of comfort. So if you are a student and wondering if is homework stressful then you must go through this blog.

While homework is a crucial component of a student’s education, when kids are overwhelmed by the amount of work they have to perform, the advantages of homework can be lost and grades can suffer. Finding a balance that ensures students understand the material covered in class without becoming overburdened is therefore essential.

Zuella Montemayor did her degree in psychology at the University of Toronto. She is interested in mental health, wellness, and lifestyle.

Psychreg is a digital media company and not a clinical company. Our content does not constitute a medical or psychological consultation. See a certified medical or mental health professional for diagnosis.

- Privacy Policy

© Copyright 2014–2034 Psychreg Ltd

- PSYCHREG JOURNAL

- MEET OUR WRITERS

- MEET THE TEAM

The New York Times

Motherlode | when homework stresses parents as well as students, when homework stresses parents as well as students.

Educators and parents have long been concerned about students stressed by homework loads , but a small research study asked questions recently about homework and anxiety of a different group: parents. The results were unsurprising. While we may have already learned long division and let the Magna Carta fade into memory, parents report that their children’s homework causes family stress and tension — particularly when additional factors surrounding the homework come into play.

The researchers, from Brown University, found that stress and tension for families (as reported by the parents) increased most when parents perceived themselves as unable to help with the homework, when the child disliked doing the homework and when the homework caused arguments, either between the child and adults or among the adults in the household.

The number of parents involved in the research (1,173 parents, both English and Spanish-speaking, who visited one of 27 pediatric practices in the greater Providence area of Rhode Island) makes it more of a guide for further study than a basis for conclusions, but the idea that homework can cause significant family stress is hard to seriously debate. Families across income and education levels may struggle with homework for different reasons and in different ways, but “it’s an equal opportunity problem,” says Stephanie Donaldson-Pressman , a contributing editor to the research study and co-author of “ The Learning Habit .”

“Parents may find it hard to evaluate the homework,” she says. “They think, if this is coming home, my child should be able to do it. If the child can’t, and especially if they feel like they can’t help, they may get angry with the child, and the child feels stupid.” That’s a scenario that is likely to lead to more arguments, and an increased dislike of the work on the part of the child.

The researchers also found that parents of students in kindergarten and first grade reported that the children spent significantly more time on homework than recommended. Many schools and organizations, including the National Education Association and the Great Schools blog , will suggest following the “10-minute rule” for how long children should spend on school work outside of school hours: 10 minutes per grade starting in first grade, and most likely more in high school. Instead, parents described their first graders and kindergartners working, on average, for 25 to 30 minutes a night. That is consistent with other research , which has shown an increase in the amount of time spent on homework in lower grades from 1981 to 2003.

“This study highlights the real discrepancy between intent and what’s actually happening,” Ms. Donaldson-Pressman said, speaking of both the time spent and the family tensions parents describe. “When people talk about the homework, they’re too often talking about the work itself. They should be talking about the load — how long it takes. You can have three problems on one page that look easy, but aren’t.”

The homework a child is struggling with may not be developmentally appropriate for every child in a grade, she suggests, noting that academic expectations for young children have increased in recent years . Less-educated or Spanish-speaking parents may find it harder to evaluate or challenge the homework itself, or to say they think it is simply too much. “When the load is too much, it has a tremendous impact on family stress and the general tenor of the evening. It ruins your family time and kids view homework as a punishment,” she said.

At our house, homework has just begun; we are in the opposite of the honeymoon period, when both skills and tolerance are rusty and complaints and stress are high. If the two hours my fifth-grade math student spent on homework last night turn out the be the norm once he is used to the work and the teacher has had a chance to hear from the students, we’ll speak up.

We should, Ms. Donaldson-Pressman says. “Middle-class parents can solve the problem for their own kids,” she says. “They can make sure their child is going to all the right tutors, or get help, but most people can’t.” Instead of accepting that at home we become teachers and homework monitors (or even taking classes in how to help your child with his math ), parents should let the school know that they’re unhappy with the situation, both to encourage others to speak up and to speak on behalf of parents who don’t feel comfortable complaining.

“Home should be a safe place for students,” she says. “A child goes to school all day and they’re under stress. If they come home and it’s more of the same, that’s not good for anyone.”

Read more about homework on Motherlode: Homework and Consequences ; The Mechanics of Homework ; That’s Your Child’s Homework Project, Not Yours and Homework’s Emotional Toll on Students and Families.

What's Next

This site uses various technologies, as described in our Privacy Policy, for personalization, measuring website use/performance, and targeted advertising, which may include storing and sharing information about your site visit with third parties. By continuing to use this website you consent to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use .

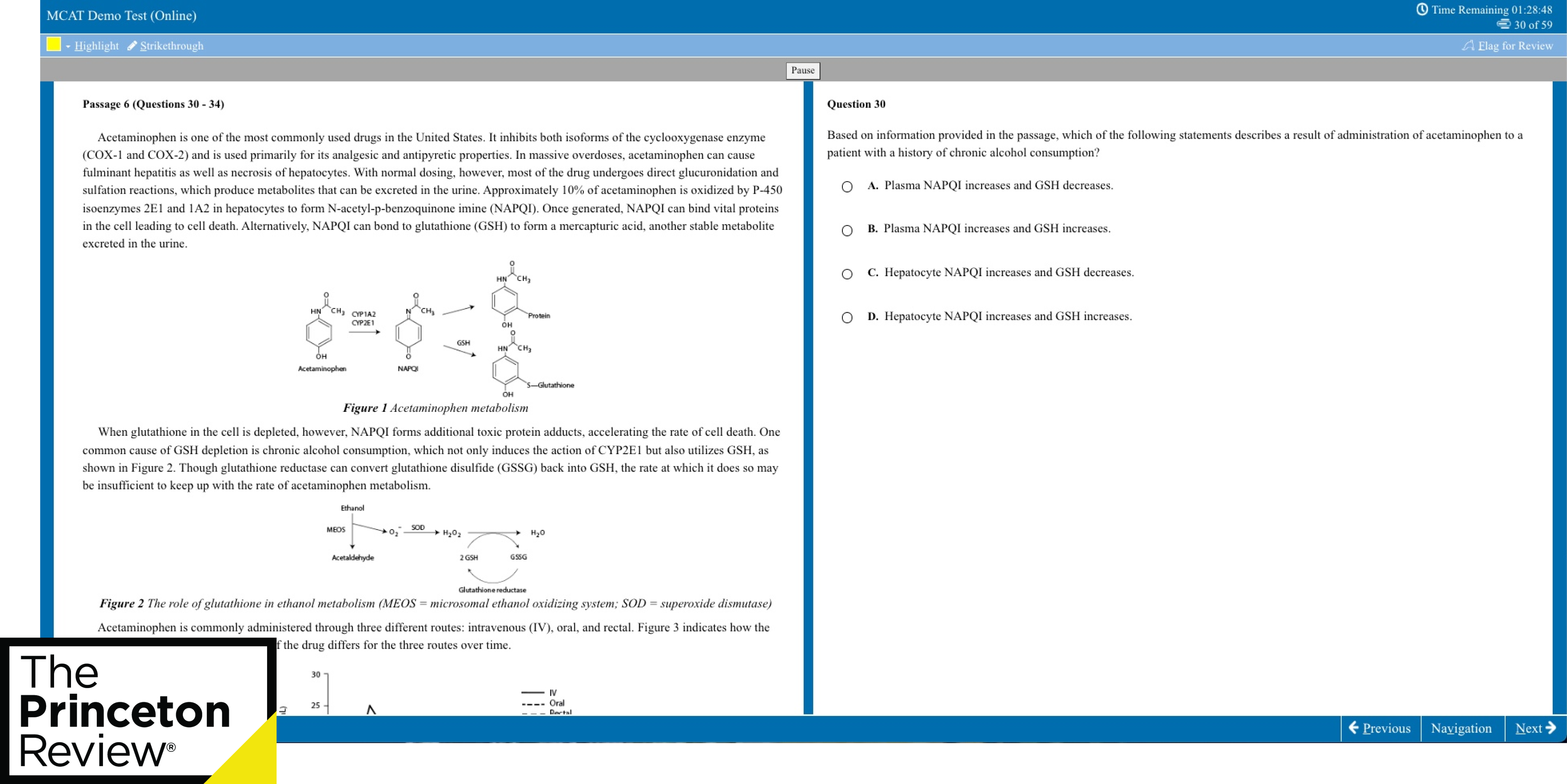

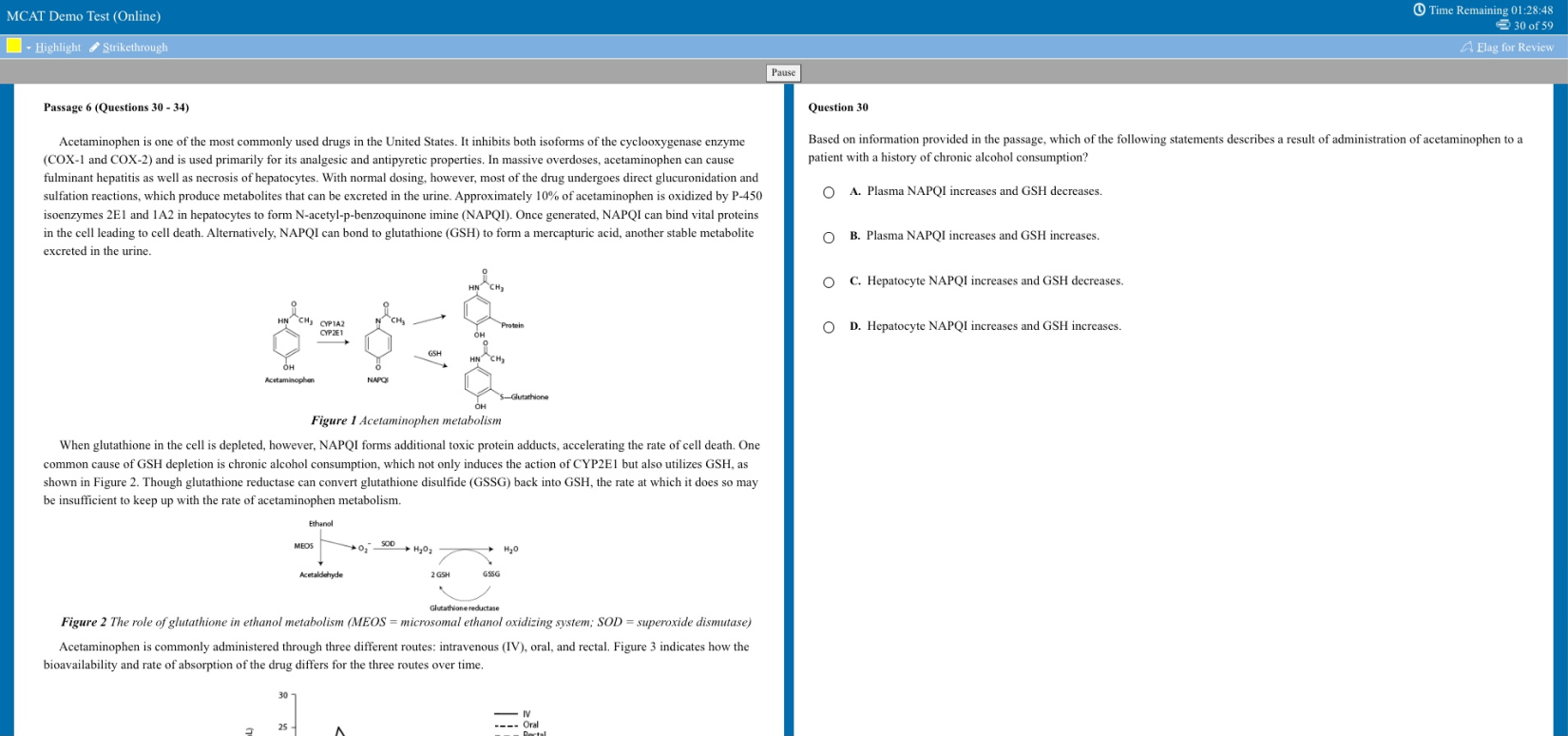

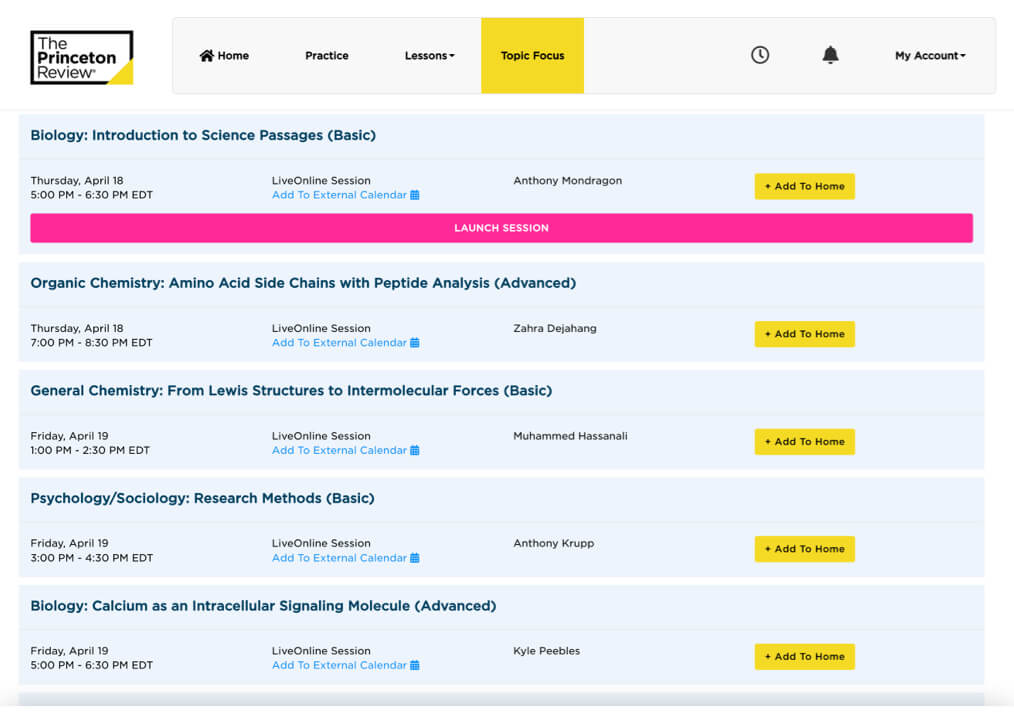

COVID-19 Update: To help students through this crisis, The Princeton Review will continue our "Enroll with Confidence" refund policies. For full details, please click here.

Enter your email to unlock an extra $25 off an SAT or ACT program!

By submitting my email address. i certify that i am 13 years of age or older, agree to recieve marketing email messages from the princeton review, and agree to terms of use., homework wars: high school workloads, student stress, and how parents can help.

Studies of typical homework loads vary : In one, a Stanford researcher found that more than two hours of homework a night may be counterproductive. The research , conducted among students from 10 high-performing high schools in upper-middle-class California communities, found that too much homework resulted in stress, physical health problems and a general lack of balance.

Additionally, the 2014 Brown Center Report on American Education , found that with the exception of nine-year-olds, the amount of homework schools assign has remained relatively unchanged since 1984, meaning even those in charge of the curricula don't see a need for adding more to that workload.

But student experiences don’t always match these results. On our own Student Life in America survey, over 50% of students reported feeling stressed, 25% reported that homework was their biggest source of stress, and on average teens are spending one-third of their study time feeling stressed, anxious, or stuck.

The disparity can be explained in one of the conclusions regarding the Brown Report:

Of the three age groups, 17-year-olds have the most bifurcated distribution of the homework burden. They have the largest percentage of kids with no homework (especially when the homework shirkers are added in) and the largest percentage with more than two hours.

So what does that mean for parents who still endure the homework wars at home?

Read More: Teaching Your Kids How To Deal with School Stress

It means that sometimes kids who are on a rigorous college-prep track, probably are receiving more homework, but the statistics are melding it with the kids who are receiving no homework. And on our survey, 64% of students reported that their parents couldn’t help them with their work. This is where the real homework wars lie—not just the amount, but the ability to successfully complete assignments and feel success.

Parents want to figure out how to help their children manage their homework stress and learn the material.

Our Top 4 Tips for Ending Homework Wars

1. have a routine..

Every parenting advice article you will ever read emphasizes the importance of a routine. There’s a reason for that: it works. A routine helps put order into an often disorderly world. It removes the thinking and arguing and “when should I start?” because that decision has already been made. While routines must be flexible to accommodate soccer practice on Tuesday and volunteer work on Thursday, knowing in general when and where you, or your child, will do homework literally removes half the battle.

2. Have a battle plan.

Overwhelmed students look at a mountain of homework and think “insurmountable.” But parents can look at it with an outsider’s perspective and help them plan. Put in an extra hour Monday when you don’t have soccer. Prepare for the AP Chem test on Friday a little at a time each evening so Thursday doesn’t loom as a scary study night (consistency and repetition will also help lock the information in your brain). Start reading the book for your English report so that it’s underway. Go ahead and write a few sentences, so you don’t have a blank page staring at you. Knowing what the week will look like helps you keep calm and carry on.

3. Don’t be afraid to call in reserves.

You can’t outsource the “battle” but you can outsource the help ! We find that kids just do better having someone other than their parents help them —and sometimes even parents with the best of intentions aren’t equipped to wrestle with complicated physics problem. At The Princeton Review, we specialize in making homework time less stressful. Our tutors are available 24/7 to work one-to-one in an online classroom with a chat feature, interactive whiteboard, and the file sharing tool, where students can share their most challenging assignments.

4. Celebrate victories—and know when to surrender.

Students and parents can review completed assignments together at the end of the night -- acknowledging even small wins helps build a sense of accomplishment. If you’ve been through a particularly tough battle, you’ll also want to reach reach a cease-fire before hitting your bunk. A war ends when one person disengages. At some point, after parents have provided a listening ear, planning, and support, they have to let natural consequences take their course. And taking a step back--and removing any pressure a parent may be inadvertently creating--can be just what’s needed.

Stuck on homework?

Try an online tutoring session with one of our experts, and get homework help in 40+ subjects.

Try a Free Session

Explore Colleges For You

Connect with our featured colleges to find schools that both match your interests and are looking for students like you.

Career Quiz

Take our short quiz to learn which is the right career for you.

Get Started on Athletic Scholarships & Recruiting!

Join athletes who were discovered, recruited & often received scholarships after connecting with NCSA's 42,000 strong network of coaches.

Best 389 Colleges

165,000 students rate everything from their professors to their campus social scene.

SAT Prep Courses

1400+ course, act prep courses, free sat practice test & events, 1-800-2review, free digital sat prep try our self-paced plus program - for free, get a 14 day trial.

Free MCAT Practice Test

I already know my score.

MCAT Self-Paced 14-Day Free Trial

Enrollment Advisor

1-800-2REVIEW (800-273-8439) ext. 1

1-877-LEARN-30

Mon-Fri 9AM-10PM ET

Sat-Sun 9AM-8PM ET

Student Support

1-800-2REVIEW (800-273-8439) ext. 2

Mon-Fri 9AM-9PM ET

Sat-Sun 8:30AM-5PM ET

Partnerships

- Teach or Tutor for Us

College Readiness

International

Advertising

Affiliate/Other

- Enrollment Terms & Conditions

- Accessibility

- Cigna Medical Transparency in Coverage

Register Book

Local Offices: Mon-Fri 9AM-6PM

- SAT Subject Tests

Academic Subjects

- Social Studies

Find the Right College

- College Rankings

- College Advice

- Applying to College

- Financial Aid

School & District Partnerships

- Professional Development

- Advice Articles

- Private Tutoring

- Mobile Apps

- International Offices

- Work for Us

- Affiliate Program

- Partner with Us

- Advertise with Us

- International Partnerships

- Our Guarantees

- Accessibility – Canada

Privacy Policy | CA Privacy Notice | Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information | Your Opt-Out Rights | Terms of Use | Site Map

©2024 TPR Education IP Holdings, LLC. All Rights Reserved. The Princeton Review is not affiliated with Princeton University

TPR Education, LLC (doing business as “The Princeton Review”) is controlled by Primavera Holdings Limited, a firm owned by Chinese nationals with a principal place of business in Hong Kong, China.

- How It Works

- Sleep Meditation

- VA Workers and Veterans

- How It Works 01

- Sleep Meditation 02

- Mental Fitness 03

- Neurofeedback 04

- Healium for Business 05

- VA Workers and Veterans 06

- Sports Meditation 07

- VR Experiences 08

- Social Purpose 11

Does Homework Cause Stress? Exploring the Impact on Students’ Mental Health

How much homework is too much?

Homework has become a matter of concern for educators, parents, and researchers due to its potential effects on students’ stress levels. It’s no secret students often find themselves grappling with high levels of stress and anxiety throughout their academic careers, so understanding the extent to which homework affects those stress levels is important.

By delving into the latest research and understanding the underlying factors at play, we hope to curate insights for educators, parents, and students who are wondering is homework causing stress in their lives?

The Link Between Homework and Stress: What the Research Says

Over the years, numerous studies investigated the relationship between homework and stress levels in students.

One study published in the Journal of Experimental Education found that students who reported spending more than two hours per night on homework experienced higher stress levels and physical health issues . Those same students reported over three hours of homework a night on average.

This study, conducted by Stanford lecturer Denise Pope, has been heavily cited throughout the years, with WebMD eproducing the below video on the topic– part of their special report series on teens and stress :

Additional studies published by Sleep Health Journal found that long hours on homework on may be a risk factor for depression while also suggesting that reducing workload outside of class may benefit sleep and mental fitness .

Lastly, a study presented by Frontiers in Psychology highlighted significant health implications for high school students facing chronic stress, including emotional exhaustion and alcohol and drug use.

Homework’s Potential Impact on Mental Health and Well-being

Homework-induced stress on students can involve both psychological and physiological side effects.

1. Potential Psychological Effects of Homework-Induced Stress:

• Anxiety: The pressure to perform academically and meet homework expectations can lead to heightened levels of anxiety in students. Constant worry about completing assignments on time and achieving high grades can be overwhelming.

• Sleep Disturbances : Homework-related stress can disrupt students’ sleep patterns, leading to sleep anxiety or sleep deprivation, both of which can negatively impact cognitive function and emotional regulation.

• Reduced Motivation: Excessive homework demands could drain students’ motivation, causing them to feel fatigued and disengaged from their studies. Reduced motivation may lead to a lack of interest in learning, hindering overall academic performance.

2. Potential Physical Effects of Homework-Induced Stress:

• Impaired Immune Function: Prolonged stress could weaken the immune system, making students more susceptible to illnesses and infections.

• Disrupted Hormonal Balance : The body’s stress response triggers the release of hormones like cortisol, which, when chronically elevated due to stress, can disrupt the delicate hormonal balance and lead to various health issues.

• Gastrointestinal Disturbances: Stress has been known to affect the gastrointestinal system, leading to symptoms such as stomachaches, nausea, and other digestive problems.

• Cardiovascular Impact: The increased heart rate and elevated blood pressure associated with stress can strain the cardiovascular system, potentially increasing the risk of heart-related issues in the long run.

• Brain impact: Prolonged exposure to stress hormones may impact the brain’s functioning , affecting memory, concentration, and cognitive abilities.

The Benefits of Homework

It’s important to note that homework also offers many benefits that contribute to students’ academic growth and development, such as:

• Development of Time Management Skills: Completing homework within specified deadlines encourages students to manage their time efficiently. This valuable skill extends beyond academics and becomes essential in various aspects of life.

• Preparation for Future Challenges : Homework helps prepare students for future academic challenges and responsibilities. It fosters a sense of discipline and responsibility, qualities that are crucial for success in higher education and professional life.

• Enhanced Problem-Solving Abilities: Homework often presents students with challenging problems to solve. Tackling these problems independently nurtures critical thinking and problem-solving skills.

While homework can foster discipline, time management, and self-directed learning, the middle ground may be to strike a balance that promotes both academic growth and mental well-being .

How Much Homework Should Teachers Assign?

As a general guideline, educators suggest assigning a workload that allows students to grasp concepts effectively without overwhelming them . Quality over quantity is key, ensuring that homework assignments are purposeful, relevant, and targeted towards specific objectives.

Advice for Students: How to balance Homework and Well-being

Finding a balance between academic responsibilities and well-being is crucial for students. Here are some practical tips and techniques to help manage homework-related stress and foster a healthier approach to learning:

• Effective Time Management : Encourage students to create a structured study schedule that allocates sufficient time for homework, breaks, and other activities. Prioritizing tasks and setting realistic goals can prevent last-minute rushes and reduce the feeling of being overwhelmed.

• Break Tasks into Smaller Chunks : Large assignments can be daunting and may contribute to stress. Students should break such tasks into smaller, manageable parts. This approach not only makes the workload seem less intimidating but also provides a sense of accomplishment as each section is completed.

• Find a Distraction-Free Zone : Establish a designated study area that is free from distractions like smartphones, television, or social media. This setting will improve focus and productivity, reducing time needed to complete homework.

• Be Active : Regular exercise is known to reduce stress and enhance mood. Encourage students to incorporate physical activity into their daily routine, whether it’s going for a walk, playing a sport, or doing yoga.

• Practice Mindfulness and Relaxation Techniques : Encourage students to engage in mindfulness practices, such as deep breathing exercises or meditation, to alleviate stress and improve concentration. Taking short breaks to relax and clear the mind can enhance overall well-being and cognitive performance.

• Seek Support : Teachers, parents, and school counselors play an essential role in supporting students. Create an open and supportive environment where students feel comfortable expressing their concerns and seeking help when needed.

How Healium is Helping in Schools

Stress is caused by so many factors and not just the amount of work students are taking home. Our company created a virtual reality stress management solution… a mental fitness tool called “Healium” that’s teaching students how to learn to self-regulate their stress and downshift in a drugless way. Schools implementing Healium have seen improvements from supporting dysregulated students and ADHD challenges to empowering students with body awareness and learning to self-regulate stress . Here’s one of their stories.

By providing students with the tools they need to self-manage stress and anxiety, we represent a forward-looking approach to education that prioritizes the holistic development of every student.

To learn more about how Healium works, watch the video below.

About the Author

Sarah Hill , a former interactive TV news journalist at NBC, ABC, and CBS affiliates in Missouri, gained recognition for pioneering interactive news broadcasting using Google Hangouts. She is now the CEO of Healium, the world’s first biometrically powered immersive media channel, helping those with stress, anxiety, insomnia, and other struggles through biofeedback storytelling. With patents, clinical validation, and over seven million views, she has reshaped the landscape of immersive media.

- About Solution-Focused Brief Therapy (SFBT)

- My Promise to You

- Christian Counseling

- Online Therapy

- Resilience Reset: A 6-Week Anxiety-Busting Kick Start

- Online Anxiety Counseling for Kids and Teens

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Fees & Insurance

Can Homework Cause Anxiety in Kids and Teens?

The amount of time students spend on homework has been trending up over time. Experts maintain this uptick is proportional to the increase in test scores, essay length requirements, and the pressure on students to succeed.

But does more homework necessarily mean more stress and anxiety ?

The answer is…it depends.

Kids can become anxious about homework for a number of reasons besides the amount and time required to complete it. They may become anxious due to lack of understanding, low confidence in their skills, or from challenging assignments.

They may be unsure of how to start an assignment, or they worry they won’t understand the instructions. Focus can also be an issue, or they might feel they need more time to complete their work but are too stressed to ask for it.

And then there’s the whole issue of timing. When is the BEST time for getting homework done?

Advantages of Completing Homework Right After School

There has long been a debate about the best time for students to complete their homework – immediately after school or after some downtime later in the afternoon. Is one option better at warding off homework anxiety than the other? Read on for the advantages of each option.

When it comes time to complete homework, getting right to it after school has some benefits. The most obvious one is that kids can get their work done earlier and have more time to relax later in the afternoon or evening.

Here are some additional benefits:

- Kids are more focused as they’ve just come from school where they’ve been concentrating hard all day. The momentum to complete work is already there.

- They can finish it all at once rather than doing it in pieces throughout the afternoon and then enjoy their evening.

- Kids learn that work comes first and play will happen after completing their school responsibilities.

- There is less arguing about homework because the expectation is always to get going and get it done!

Advantages of Completing Homework After Some Downtime

Others argue that after a long day at school, kids need some downtime before they can focus on homework. Giving your child some time to relax, have a snack, and maybe play outside before getting started can serve them well.

Many parents find that their kids are more relaxed and creative later in the afternoon, after a break. Expending energy outside also helps them to stay alert and energetic when it comes to finishing their homework.

Remember that the purpose of homework is to give kids time to practice what they have learned during that day’s school session. But when their brains are still full of school-day information, and their bodies need a break from sitting at a desk, those assignments can be very difficult. A break may be the best remedy.

As a parent, you know your child best. Some kids may be more productive sitting down to complete their homework right away while others do much better with an extended break first. With after school sports and activities, you may have days where the only time homework assignments are going to get done are later in the evening. Do what works best for your child and family!

5 Tips for Making Homework Time Go Smoothly

Aside from the decision of WHEN to complete homework, there’s also the anxiety that can surface around the assignments themselves. It’s a lot to deal with as a parent when you’ve had a full day yourself.

Here are some tips to make sure homework time goes smoothly.

Establish a time and place

Create a routine in which your child goes to their designated study spot at the same time every day. Have them work on homework until they’re finished. Try experimenting with different time slots to complete homework assignments until it becomes clear what time is most effective for your child. Also make sure your child is getting enough rest and exercise each evening.

Write down assignments

Teach your child to write down assignments in a notebook every day as this habit encourages them to take responsibility for their own planning. Then have them read instructions carefully before starting any homework assignments. Some parents prefer to check with their child’s teachers regularly to determine what work needs to be done. Whether you choose to do so or not, your role should be one of monitor and not project manager. Leave that role to your child.

Break up large tasks

Show your child how to break up larger tasks for homework assignments and projects. For example, if an assignment includes an essay or two pages of math problems, ask your child to try dividing it into manageable parts. Doing so helps them see that completing any one part is not overwhelming. This tip is especially helpful if your child often feels stressed or anxious when doing homework or struggles with Attention Deficit Disorder (ADD).

Offer to help your child if needed

Check for understanding as well as completion

Studies show that when parents make themselves available to help their kids with homework, they earn better grades. It’s important to encourage your child to ask questions when they don’t understand. Give them the support they need and encourage them to keep working at it. Over time, they’ll see their hard work pay off and realize they can do hard things.

In sum, homework can be stressful! Not understanding the best time of day to complete it, how to plan and schedule it, and how to get help when they don’t understand is often anxiety producing for both kids and teens. The good news is that there are loads of opportunities to teach important life skills to your child.

Your child is unique and there is no one-size-fits-all homework approach for all kids. So much depends on your child’s temperament, their energy level, time commitments, and individual preferences – both yours and your child’s. The best thing you can do is experiment until you find what works best for the entire family.

Begin Online Therapy for Kids and Teens with Anxiety in Illinois

Using Solution-Focused Brief Therapy , I help kids and teens reduce their anxiety and build resilience so they can become a happier, more confident version of themselves.

And kids love being able to receive counseling from the comfort and privacy of their own home. Studies have consistently proven that online therapy delivers equal results to in-office counseling.

As an experienced and caring therapist , I love providing counseling for anxiety. To start your child’s counseling journey, call me at 224-236-2296 or email [email protected] to schedule a FREE 20-minute consultation.

Helena Madsen, MA, LCPC is the founder of Briefly Counseling . I specialize in providing online short-term anxiety treatment for kids and teens ages 7 – 18 as well as Christian counseling.

Whether you’re on the North Shore, in Naperville, Chicago, Champaign, Barrington, Libertyville, Glenview, or downstate Illinois, I can help. Schedule your appointment or consultation today. I look forward to working with your child to quickly and effectively help them in activating their strengths, resources, and resilience, in order to live with confidence and hope.

(224) 236-2296 [email protected]

Solution-Focused Brief Therapy | My Promise To You | FAQs | Fees & Insurance | About Me | Contact | Blog

Transforming the understanding and treatment of mental illnesses.

Información en español

Celebrating 75 Years! Learn More >>

- Health Topics

- Brochures and Fact Sheets

- Help for Mental Illnesses

- Clinical Trials

I’m So Stressed Out! Fact Sheet

- Download PDF

- Order a free hardcopy

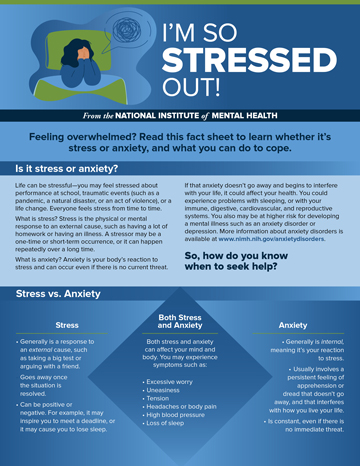

Feeling overwhelmed? Read this fact sheet to learn whether it’s stress or anxiety, and what you can do to cope.

Is it stress or anxiety?

Life can be stressful—you may feel stressed about performance at school, traumatic events (such as a pandemic, a natural disaster, or an act of violence), or a life change. Everyone feels stress from time to time.

What is stress? Stress is the physical or mental response to an external cause, such as having a lot of homework or having an illness. A stressor may be a one-time or short-term occurrence, or it can happen repeatedly over a long time.

What is anxiety? Anxiety is your body's reaction to stress and can occur even if there is no current threat.

If that anxiety doesn’t go away and begins to interfere with your life, it could affect your health. You could experience problems with sleeping, or with your immune, digestive, cardiovascular, and reproductive systems. You also may be at higher risk for developing a mental illness such as an anxiety disorder or depression. Read more about anxiety disorders .

So, how do you know when to seek help?

Stress vs. Anxiety

| Stress | Both Stress and Anxiety | Anxiety |

|---|---|---|

Both stress and anxiety can affect your mind and body. You may experience symptoms such as: |

It’s important to manage your stress.

Everyone experiences stress, and sometimes that stress can feel overwhelming. You may be at risk for an anxiety disorder if it feels like you can’t manage the stress and if the symptoms of your stress:

- Interfere with your everyday life.

- Cause you to avoid doing things.

- Seem to be always present.

Coping With Stress and Anxiety

Learning what causes or triggers your stress and what coping techniques work for you can help reduce your anxiety and improve your daily life. It may take trial and error to discover what works best for you. Here are some activities you can try when you start to feel overwhelmed:

- Keep a journal.

- Download an app that provides relaxation exercises (such as deep breathing or visualization) or tips for practicing mindfulness, which is a psychological process of actively paying attention to the present moment.

- Exercise, and make sure you are eating healthy, regular meals.

- Stick to a sleep routine, and make sure you are getting enough sleep.

- Avoid drinking excess caffeine such as soft drinks or coffee.

- Identify and challenge your negative and unhelpful thoughts.

- Reach out to your friends or family members who help you cope in a positive way.

Recognize When You Need More Help

If you are struggling to cope, or the symptoms of your stress or anxiety won’t go away, it may be time to talk to a professional. Psychotherapy (also called talk therapy) and medication are the two main treatments for anxiety, and many people benefit from a combination of the two.

If you are in immediate distress or are thinking about hurting yourself, call or text the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline at 988 or chat at 988lifeline.org .

If you or someone you know has a mental illness, is struggling emotionally, or has concerns about their mental health, there are ways to get help. Read more about getting help .

More Resources

- NIMH: Anxiety Disorders

- NIMH: Caring for Your Mental Health

- NIMH: Child and Adolescent Mental Health

- NIMH: Tips for Talking With a Health Care Provider About Your Mental Health

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Anxiety and Depression in Children

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES National Institutes of Health NIH Publication No. 20-MH-8125

The information in this publication is in the public domain and may be reused or copied without permission. However, you may not reuse or copy images. Please cite the National Institute of Mental Health as the source. Read our copyright policy to learn more about our guidelines for reusing NIMH content.

- Close Menu Search

- Award Winners

Is Excessive Homework the Cause of Many Teen Issues?

Sydney Trebus , Business Manager | September 15, 2019

Does excessive homework really make a student perform worse? Is homework a big influencer on the emotional and physical health of students? Can we change the bad reputation homework has obtained over the years or is it too late?

Today, schooling is ever-changing, currently focusing on a “necessary” end goal of attending college. Standards are rising, teachers are better trained, and students are left with rigorous courses riddled with hours and hours of homework. People are now wondering how important homework really is. Is that just the overload talking or does homework actually have a negative impact on students?

Popular opinion would suggest yes, claiming that homework is a useless and stress-inducing part of school at any age. Many Boulder High students communicate a similar complaint.

Seniors Carson Williams and Carson Bennett voiced their opinions. Bennet says that “Homework results in later bedtimes which means we get less sleep and therefore, have less energy the next day.” Williams agreed and added,“Homework is good if you need it to study, but if it is just busywork then it is useless.”

Another student, Bishal Ellison, commented that in some classes “homework doesn’t impact [his] success, there is no point … In one of [his] classes, homework is just for extra credit.”

While student opinions are extremely significant, teachers are the ones in control of this so-called “stress inducing and useless activity.”

Mr. Weatherly, an AP World Geography teacher here at Boulder High, commented that homework has an enormous impact on the success of students within the class; he claimed that there is simply not enough time in class to review everything. He does, however, agree with popular opinion, saying, “Teachers give homework thinking about their own class, not the five or six others students have.”

So which is it? How important is homework? Homework has been seen both beneficial and detrimental in association with time. Homework over a certain time limit can cause stress, depression, anxiety, lack of sleep, and more.

Homework distracts from extracurriculars and sports as well, something colleges often look for. Homework is ultimately leading students to resent school as a whole.

According to a study done by Stanford University, 56 percent of students considered homework a primary source of stress, 43 percent viewed tests as a primary stressor, while less than one percent of the students said homework was not a stressor. They were able to conclude that too much homework can result in a lack of sleep, headaches, exhaustion, and weight loss.

Experts denote that the homework assigned to students today promotes less active learning and instead leads to boredom and a lack of problem-solving skills. Active learning, done through students learning from each other through discussion and collaboration, enhances a student’s ability to analyze and apply content to aid them in a real-world setting.

This negative attitude towards homework can, unfortunately, arise at a young age, especially in today’s schooling systems.

Students in all grades are required to extend the hard rigor of school past the average eight hours they need to spend inside the building. According to an Education Week article by Marva Hinton, kindergarteners are often required to do a minimum of 30 minutes of homework a night; these young students are expected to read for 15 minutes as well as work on a packet for another 15-30 minutes.

Kindergarten is forcing children to learn concepts they may not be ready for, discouraging them at a young age. As a principle rule, the National PTA recommends 10 to 20 minutes of homework per night for children in first grade and an additional 10 minutes for every grade after that.

After this time marker, homework begins to be detrimental to the success of a student. Additionally, according to the Journal of Educational Psychology , students who did more than 90 to 100 minutes of homework per night actually did worse on tests than those with less than 90 minutes of homework.

The hours of homework students receive takes time that could be spent on extracurriculars, with family and friends, or on sports or activities. Children and young adults focus a large part of their time and energy on school, removing time to replenish and work on other skills in life, including socializing.

Physical activity can actually be very beneficial to the success rates of students, improving self-esteem, well-being, motivation, memory, focus, and higher thinking.

According to the US Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC ) , exercise has an impact on cognitive skills such as concentration and attention, and it enhances classroom attitudes and behaviors.

The more time taken away from the emotional and physical health of a student, the more resentful they will be towards school. In kindergarten, over 85 percent of students are enthusiastic about learning and attending school, whereas 40 percent of high school students are chronically disengaged from school and any learning that takes place.

What’s even more baffling is that as students enter high school, they are expected to be enthusiastic about school, obtain perfect grades and test scores, and do extracurricular activities and sports in order to get into a good college.

Logan Powell, the Dean of Admissions at Brown University asks when accepting students, “Have they learned time management skills, leadership, teamwork, discipline? How have they grown as a person and what qualities will they bring to our campus?”

These are unrealistic standards for students who most likely already have negative attitudes towards school and homework and aren’t given the opportunity to work on the skills colleges look for by exploring their community through clubs, volunteering, and working.

Experts see how detrimental homework can really be for a plethora of reasons; Donaldson Pressman reported that homework is not only not beneficial to a students grades or GPA, but it is also detrimental to their attitude towards school, their grades, their self-confidence, their social skills, and their quality of life.”

Homework, however, helps student achievement, reinforces good habits, involves parents in their students’ learning, and helps students remember material learned in class.

This is all based on the circumstances however, if schools keep making homework more prominent in the learning system, students will lose their passion for learning. Unfortunately, many of us already have. So when teachers consider giving homework to their students, they should ask themselves how they believe it will improve their students’ learning and abilities.

Clash of Clans: In Defense of “Rushing”

Casa Bonita Makes a Splash

Instagram Turns Us Into Awful People

Pecking Away at Food Waste

The Glamorization of Mental Illness

Comments (4)

Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Chris • Feb 23, 2023 at 6:24 am

I hate homework in 5th grade

Jason • May 24, 2023 at 8:25 am