- Essay Topic Generator

- Summary Generator

- Thesis Maker Academic

- Sentence Rephraser

- Read My Paper

- Hypothesis Generator

- Cover Page Generator

- Text Compactor

- Essay Scrambler

- Essay Plagiarism Checker

- Hook Generator

- AI Writing Checker

- Notes Maker

- Overnight Essay Writing

- Topic Ideas

- Writing Tips

- Essay Writing (by Genre)

- Essay Writing (by Topic)

Essay about Family Values & Traditions: Prompts + Examples

A family values essay (or a family traditions essay) is a type of written assignment. It covers such topics as family traditions, customs, family history, and values. It is usually assigned to those who study sociology, culture, anthropology, and creative writing.

In this article, you will find:

- 150 family values essay topics

- Outline structure

- Thesis statement examples

- “Family values” essay sample

- “Family traditions” essay sample

- “What does family mean to you?” essay sample.

Learn how to write your college essay about family with our guide.

- 👪 What Is a Family Values Essay about?

- 💡 Topic Ideas

- 📑 Outlining Your Essay️

- 🏠️ Family Values: Essay Example

- 🎃 Family Traditions: Essay Example

- 😍 What Does Family Mean to You: Essay Example

👪 Family Values Essay: What Is It about?

What are family values.

Family values are usually associated with a traditional family. In western culture, it is called “ a nuclear family .”

A nuclear family represents a family with a husband, wife, and children living together.

The nuclear family became common in the 1960s – 1970s. That happened because of the post-war economic boom and the health service upgrade. That allowed elder relatives to live separately from their children.

These days, the nuclear family is no longer the most common type of family. There are various forms of families:

- Single-parent families

- Non-married parents

- Blended families

- Couples with no children

- Foster parents, etc.

How did the nuclear family become so wide-spread?

The nuclear family culture was mostly spread in western cultures. According to many historians, it was because of the Christian beliefs.

However, many people believe that Christianity was not the only reason. The industrial revolution also played a significant role.

Nowadays, the understanding of the term varies from person to person. It depends on their religious, personal, or cultural beliefs.

Family Values List

Cultural background plays a significant role in every family’s values. However, each family has its own customs and traditions as well.

Some common types of family values include:

- Having a sense of justice

- Being honest

- Being respectful to others

- Being patient

- Being responsible

- Having courage

- Participating in teamwork

- Being generous

- Volunteering

- Being respectful

- Featuring dignity

- Demonstrating humanity

- Saving salary

- Prioritizing education

- Doing your best at work

- Maintaining respectful relationships with coworkers/classmates

- Being caring

- Willing to learn

- Treating others with respect

- Being modest

- Family game nights

- Family vacations

- Family meals

- Being patriotic

- Being tolerant

- Following the law

- Being open-minded

💡 150 Family Values Essay Topics

If you find it challenging to choose a family values topic for your essay, here is the list of 150 topics.

- Social family values and their impact on children.

- Divorce: Psychological Effects on Children.

- Do family values define your personality?

- Toys, games, and gender socialization.

- The correlation between teamwork and your upbringing.

- Family Structure and Its Effects on Children.

- What does honesty have to do with social values?

- Solution Focused Therapy in Marriage and Family.

- The importance of being respectful to others.

- Parent-Child Relationships and Parental Authority.

- Political family values and their impact on children.

- Postpartum Depression Effect on Children Development.

- The importance of patriotism.

- Social factors and family issues.

- Is being open-minded crucial in modern society?

- Modern Society: American Family Values.

- What role does tolerance play in modern society?

- Does hard work identify your success?

- Family involvement impact on student achievement.

- Religious family values and their impact on children.

- Native American Women Raising Children off the Reservation.

- What does spiritual learning correlate with family values?

- Modest relations and their importance.

- The role of parental involvement.

- What is violence, and why is it damaging?

- Myths of the Gifted Children.

- Work family values and their impact on children.

- When Should Children Start School?

- Does salary saving help your family?

- Family as a System and Systems Theory.

- Why should education be a priority?

- Child-free families and their values.

- Family violence effects on family members.

- Why is doing your best work important for your family?

- School-Family-Community Partnership Policies.

- Moral values and their impact on children.

- Does being trustworthy affect your family values?

- Gender Inequality in the Study of the Family.

- Can you add your value to the world?

- Your responsibility and your family.

- Family in the US culture and society.

- Recreational family values and their impact.

- Balancing a Career and Family Life for Women.

- Family vacations and their effects on relationships.

- Family meal and its impact on family traditions.

- Children Play: Ingredient Needed in Children’s Learning.

- Family prayer in religious families.

- Family changes in American and African cultures.

- Hugs impact on family ties.

- Are bedtime stories important for children?

- How Video Games Affect Children.

- Do family game nights affect family bonding?

- Divorce Remarriage and Children Questions.

- What is the difference between tradition and heritage culture?

- How Autistic Children Develop and Learn?

- The true meaning of family values.

- Egypt families in changed and traditional forms.

- Does culture affect family values?

- Are family values a part of heritage?

- The Development of Secure and Insecure Attachments in Children.

- Does supporting family traditions impact character traits?

- Parents’ Accountability for Children’s Actions.

- Does your country’s history affect your family’s values?

- Do family traditions help with solving your family problems?

- Impact of Domestic Violence on Children in the Classroom.

- Does having business with your family affect your bonding?

- Family as a social institution.

- Different weekly family connections ideas and their impact.

- Different monthly family connections ideas and their impact.

- The importance of your family’s daily rituals.

- Group and Family Therapies: Similarities and Differences.

- Holiday family gatherings as an instrument of family bonding.

- Should a family have separate family budgets?

- Parental non-engagement in education.

- Globalization and its impact on family values.

- The difference between small town and big city family values.

- Divorce and how it affects the children.

- Child’s play observation and parent interview.

- Family fights and their impact on the family atmosphere.

- Why are personal boundaries important?

- Single-parent family values.

- Gender Differences in Caring About Children.

- Does being an only child affect one’s empathy?

- Grandparents’ involvement in children upbringing.

- Use of Social Networks by Underage Children.

- Same-sex marriage and its contribution to family values.

- Does surrogacy correspond to family values?

- Are women better parents than men?

- Does the age gap between children affect their relationship?

- Does having pets affect family bonding?

- Parenting Gifted Children Successfully Score.

- Having a hobby together and its impact.

- Discuss living separately from your family.

- Shopping together with your family and its impact on your family values.

- Movie nights as a family tradition.

- Parents’ perception of their children’s disability.

- Does being in the same class affect children’s relationships?

- Does sharing a room with your siblings affect your relationship?

- Raising Awareness on the Importance of Preschool Education Among Parents.

- Pros and cons of having a nanny.

- Do gadgets affect your children’s social values?

- The Role of Parents in Underage Alcohol Use and Abuse.

- Pros and cons of homeschooling.

- Limiting children’s Internet usage time and their personal boundaries.

- Is having an heirloom important?

- Divorce influence on children’s mental health.

- Is daycare beneficial?

- Should your parents-in-law be involved in your family?

- Children’s Foster Care and Associated Problems.

- Pets’ death and its impact on children’s social values.

- Clinical Map of Family Therapy.

- Passing of a relative and its impact on the family.

- How Do Parents See the Influence of Social Media Advertisements on Their Children?

- Relationship within a family with an adopted child.

- Discuss naming your child after grandparents.

- The Effects of Post-Divorce Relationships on Children.

- Discuss the issue of spoiling children.

- Discuss nuclear family values.

- Parental Involvement in Second Language Learning.

- Children’s toys and their impact on children’s values.

- Discuss the children’s rivalry phenomenon.

- Family Educational Rights & Privacy Act History.

- Relationship between parents and its impact on children.

- Lockdown and its impact on family values.

- Financial status and children’s social values.

- Do parents’ addictions affect children?

- Corporal punishment and its effects on children.

- Discuss step-parents’ relationship with children.

- Severe diseases in the family and their impact.

- Developing Family Relationship Skills to Prevent Substance Abuse Among Youth Population.

- Arranged marriages and their family values.

- Discuss the age gap in marriages.

- The Effects of Parental Involvement on Student Achievement.

- International families and their values.

- Early marriages and their family values.

- Parental Divorce Impact on Children’s Academic Success.

- Discuss parenting and family structure after divorce.

- Mental Illness in Children and Its Effects on Parents.

- Discuss family roles and duties.

- Healthy habits and their importance in the family.

- Growing-up Family Experience and the Interpretive Style in Childhood Social Anxiety.

- Discuss different family practices.

- Dealing With Parents: Schools Problem.

- Ancestors worship as a family value.

- The importance of family speech.

- Does the Sexual Orientation of Parents Matter?

- Mutual respect as a core of a traditional family.

- Experiential Family Psychotherapy.

- Should the law protect the family values?

- Family as a basic unit of society.

Couldn’t find the perfect topic for your paper? Use our essay topic generator !

📑 Family Values Essay Outline

The family values essay consists of an introduction, body, and conclusion. You can write your essay in five paragraphs:

- One introductory paragraph

- Three body paragraphs

- One conclusion paragraph.

Family values or family history essay are usually no more than 1000 words long.

What do you write in each of them?

| The introduction part should grab your reader’s attention. It includes the description of the topic you chose and your thesis statement. The thesis statement will be explained later on. | |

| In the body part, you should elaborate on your thesis. You can give three different points (one for each paragraph) and support all of them. So, each body paragraph consists of your claim and evidence. Make sure to start each body paragraph with a . Topic sentence reveals your paragraph’s main idea. By reading it, your reader can understand what this paragraph will be about. | |

| The conclusion should not be long. One paragraph is more than enough. In the conclusion part, you can sum up your essay and/or restate your thesis. |

Learn more on the topic from our article that describes outline-making rules .

Thesis Statement about Family Values

The thesis statement is the main idea of your essay. It should be the last sentence of the introduction paragraph .

Why is a thesis statement essential?

It gives the reader an idea of what your essay is about.

The thesis statement should not just state your opinion but rather be argumentative. For the five-paragraph family values essay, you can express one point in your thesis statement.

Let’s take a look at good and bad thesis statement about family values templates.

| Children with social values are respectful. | Social values play a significant role in children’s ability to be respectful because they teach how to live in a society. |

| Everyone should be open-minded. | Being open-minded is a crucial feature in modern society since every day brings something new to our lives. |

| Only educated people have a broad mind. | Education plays a massive role in broadening one’s mind because we can learn something new. |

Need a well-formulated thesis statement? You are welcome to use our thesis-making tool !

🏠️ Family Values Essay: Example & Writing Prompts

So, what do you write in your family values essay?

Start with choosing your topic. For this type of essay, it can be the following:

- Your reflection about your family’s values

- The most common family values in your country

- Your opinion on family values.

Let’s say you want to write about your family values. What do you include in your essay?

First, introduce family values definition and write your thesis statement.

Then, in the body part, write about your family’s values and their impact on you (one for each paragraph).

Finally, sum up your essay.

Family Values Essay Sample: 250 Words

| Every family has specific values that define children’s upbringing. My family is no different, as we believe that some of the most important values are honesty, generosity, and responsibility because they define your personality and attitude. | |

| Being honest is an important character trait that can help you build strong relationships with others. Many children are taught that if they get into trouble, it is better not to hide it. If a person keeps that in mind since childhood, it will be much easier for them to communicate with others when they grow up. | |

| Generosity is beneficial not only for others but also for yourself. It is essential to teach children to be generous because it can build a strong community. Human beings are social species. That is why we need to cooperate and help the ones in need. My family believes this is what being generous is about. | |

| Being responsible can help you get through many things. If you are responsible, you are generally more reliable and confident. That can bring you better relationships with others as well. Not to mention that in adulthood, your responsibility can positively affect your work. | |

| To sum up, even though each family might have different family values, they all have a common goal. Every parent wants their children to become good people with strong beliefs. If we all uphold these values, we will build a better community. |

🎃 Family Traditions Essay: Example & Writing Prompts

Family traditions essay covers such topics as the following:

- Family traditions in the USA (in England, in Spain, in Pakistan, etc.)

- Traditions in my family

- The importance of family traditions for children.

- My favorite family traditions

After you decide on your essay topic, make an outline.

For the introduction part, make sure to introduce the traditions that you are going to write about. You can also mention the definition of traditions.

In the body part, introduce one tradition for each paragraph. Make sure to elaborate on why they are essential for you and your family.

Finally, sum up your essay in the conclusion part.

Family Traditions Essay Sample: 250 Words

| Family traditions vary from country to country and from family to family. Some families go hiking together, read bedtime stories for children, and have family walks. As for my family, we have some annual traditions like celebrating holidays together, taking family trips, and having game nights. | |

| Every Christmas and Thanksgiving, my family and I gather together to celebrate. We exchange gifts, have family dinner, and overall have a good time. We also like winter outdoor activities, so every Christmas we go ice-skating, skiing or snowboarding. Every year I’m looking forward to these holidays because I can spend some quality time with my family. | |

| Every summer, my family and I go on a family trip. Although everyone is busy with their own work, we try to spend time travelling together. Last year we visited India. We went sightseeing, explored the temples, and ate delicious Indian food. This time helped us form stronger bond. | |

| During our family reunions, we usually have family game nights. We love board games, so we spend some hours playing them. Although these games require competition, they only help maintain a good relationship within one family. | |

| To sum up, I personally believe that family traditions are an irreplaceable part of people’s lives. You may see your family only a couple of times a year, but the time you spend together remains in your memory forever. |

😍 What Does Family Mean to You Essay: Example & Writing Prompts

The family definition essay covers your opinion on family and its importance for you.

Some of the questions that can help you define your topic:

- How has your family shaped your character?

- How can you describe your upbringing?

In the introduction part, you can briefly cover the importance of family in modern society. Then make sure to state your thesis.

As for the body parts, you can highlight three main ideas of your essay (one for each paragraph).

Finally, sum up your essay in the conclusion part. Remember that you can restate your thesis statement here.

What Does Family Mean to You Essay Sample: 250 Words

| Family plays one of the crucial roles in personal development because they form one’s character and points of view. My family had a significant influence on me and my personality in many ways. | |

| My family’s values defined my character traits, such as being responsible and trustworthy, always doing my best at any given work, and being honest with others. These personal qualities always help me get through all the difficulties in my life. | |

| I learned about being generous from my family, and I believe it can help me build my own family in the future. Generosity is about empathy for others. In my opinion, it is one of the essential features of not only family but of any community. So, I hope my future family can inherit this value. | |

| Family traditions are the way to get away from your everyday routine and to spend some quality time. Everyone is busy with their own life. So, if I have some free time, it is always an excellent option to spend it with my family. Whether it is some national holiday or just a regular weekend, I try to have a family meal or take a family trip somewhere. It helps me unwind and gain some energy. | |

| To sum up, every family has a significant influence on their children. If this influence is positive, the children will carry these values through their whole life and influence their children. |

Now you have learned how to write your family values essay. What values have you got from your family? Let us know in the comments below!

❓ Family Values FAQ

Family values are the principles, traditions, and beliefs that are upheld in a family. They depend on family’s cultural, religious, and geographical background. They might be moral values, social values, work values, political values, recreational values, religious values, etc. These values are usually passed on to younger generations and may vary from family to family.

Why are family values important?

Family values are important because they have a strong impact on children’s upbringing. These values might influence children’s behavior, personality, attitude, and character traits. These can affect how the children are going to build their own families in the future.

What are Christian family values?

Some Christian family values are the following: 1. Sense of justice 2. Being thankful 3. Having wisdom 4. Being compassion 5. Willing to learn 6. Treating others with respect 7. Modesty

What are traditional family values?

Each family has its own values. However, they do have a lot of resemblances. Some traditional family values are the following: 1. Having responsibilities to your family 2. Being respectful to your family members 3. Not hurting your family members 4. Compromising

Family Values: What They Are, What They Are And Examples

Every time we have thought that the families of our friends or close acquaintances are different from ours, we usually end up reflecting on the reason for their priorities. Families form a system of values that is generally transmitted from generation to generation, a system that allows them to evaluate the most appropriate and healthy ways to achieve interpersonal and intrapersonal coexistence.

Family values are the fundamental beliefs, principles, and norms that guide the behaviors, attitudes, and interactions within a family unit. These values shape the family’s identity, culture, and cohesion, influencing how members communicate, relate to one another, and navigate life’s challenges together. In this article, we delve into the significance, components, and importance of family values in fostering strong and resilient relationships.

Table of Contents

What are family values

Family values are precepts, norms or agreements that guide the members of each family to have a harmonious, fluid and balanced coexistence. Generally, family values are based on various concepts of love. Love as the basis of different relationships usually leads to a coexistence of tolerance, mutual growth, respect, solidarity and empathy. That is, family values direct attitudes, interests and thoughts towards human development

As Ramos explains (1) , boys and girls need to be educated based on the existence of clear, well-configured values with a coherence that gives them credibility. Double speech or double life cannot exist here because experiences are transmitted and lived. On the other hand, children learn from home even when their parents have no intention of doing so due to the powerful factor of imitation.

The notion of good and evil is not something innate in children; it is adults, with their way of approving or disapproving certain attitudes, who will propose the rules. For example, from the age of 3, good is what makes mom happy and calm and bad is what makes her angry; This is how the child’s moral conscience is born. In the following article you will find more information about Ethical Values: what they are, list and examples.

Significance of Family Values

Family values serve as the cornerstone of healthy and functional family dynamics, providing a framework for:

- Identity Formation : Family values help shape individuals’ sense of identity, belonging, and self-concept by instilling a shared set of beliefs, traditions, and customs.

- Socialization : Family values play a crucial role in socializing children and teaching them essential life skills, moral principles, and ethical standards that guide their behavior and decision-making.

- Relationship Building : Family values foster strong bonds, trust, and communication among family members, promoting empathy, understanding, and mutual respect.

- Conflict Resolution : Family values serve as a foundation for resolving conflicts, managing disagreements, and promoting forgiveness, reconciliation, and healing within the family unit.

Components of Family Values

Family values encompass a wide range of beliefs, attitudes, and practices, including:

- Love and Support : Unconditional love, acceptance, and emotional support are central to family values, fostering a sense of security, belonging, and well-being among all members.

- Respect and Empathy : Respect for individual differences, perspectives, and boundaries promotes empathy, tolerance, and harmonious relationships within the family.

- Communication and Trust : Open, honest, and respectful communication builds trust, transparency, and understanding among family members, facilitating meaningful connections and problem-solving.

- Responsibility and Accountability : Teaching responsibility, accountability, and integrity instills a strong work ethic, moral values, and a sense of duty to oneself and others.

- Tradition and Ritual : Honoring family traditions, rituals, and celebrations fosters a sense of continuity, heritage, and belonging across generations, strengthening family bonds and collective identity.

Importance of Family Values

Family values play a vital role in shaping individuals’ attitudes, behaviors, and relationships, contributing to:

- Stability and Resilience : Strong family values provide a stable foundation that helps family members navigate life’s challenges, transitions, and crises with resilience and adaptability.

- Well-Being and Mental Health : A supportive family environment characterized by positive values promotes emotional well-being, self-esteem, and mental health for all members.

- Social Connectedness : Family values reinforce the importance of social connectedness, fostering a sense of belonging, community, and solidarity that extends beyond the immediate family unit.

- Generational Legacy : Passing down family values from one generation to the next preserves cultural heritage, traditions, and wisdom, ensuring continuity and cohesion within the family lineage.

Defining family values for children

Family values are all those recommendations that our parents have given us at certain times or recommendations on how we should behave with our friends, family and neighbors. It is also all the advice that they give us on how to deal with the things that worry us, make us sad or upset.

Many times family values guide us to respect any living being, including schoolmates, friends, siblings, cousins, teachers, animals, nature and any other person we know. That attitude of respect that family values teach us allows us to accept and promote the freedom of every living being.

List of family values

The most important family values are the following:

- Solidarity.

- Resilience.

- Responsibility.

- Compassion.

- Conviction.

- Discipline.

- Independence.

- Commitment.

- Perseverance.

- Self-control.

- Friendship.

If you want to know more about other types of values, in the following article you will find information about the 20 Professional Values: what they are, list and examples.

Examples of family values

Finally, it is important to be aware that family values teach us to live with our peers, although without a doubt we are not all the same. Below we leave you some examples of how to apply family values in our lives:

- Solidarity and equity : We are not all the same nor have we lived the same experiences. A child who has grown up in a community far removed from the city with few services at home (for example, electricity and water) will be relatively limited in some aspects in relation to another who has grown up in the metropolis (with more services and access than facilitate their development); both children despite differences in their performance (social, academic, emotional, cognitive, and so on). Both express the same interest in growing, so solidarity guides us towards supporting the interests of both. A child who learns that there will be notable differences in people will know that this does not correspond to the exception of the practice of family values.

- Gratitude : the learning of this family value is observed, for example, in those moments where the child is taught the corresponding social skills – especially in recognizing how important a person and his or her efforts are – guiding him or her to practice verbal and bodily gestures. (a hug, a handshake and its corresponding articulation). Here we explain what gratitude is and how it is practiced.

- Empathy : An example from childhood of this family value is the frequent attitude of the child when he observes one of his classmates or a little brother crying and he approaches to ask – What’s wrong? – and maybe a few pats on the back too. Empathy allows the human being – and in this case the child – to try to understand the emotional life and everything else that happens in the people, events and animals that surround them.

- Friendship : From childhood we must be able to learn the value of friendship, mutual affection and the loyalty that is born from contact with others.

Family values are the bedrock of strong, nurturing, and harmonious relationships, providing guidance, stability, and support for individuals and families as they navigate life’s journey together. By upholding and embodying positive family values, individuals can cultivate a sense of belonging, purpose, and fulfillment within their family units, fostering bonds that endure through time and adversity.

This article is merely informative, at PsychologyFor we do not have the power to make a diagnosis or recommend a treatment. We invite you to go to a psychologist to treat your particular case.

If you want to read more articles similar to Family values: what they are, what they are and examples we recommend that you enter our Social Psychology category.

- Maria Ramos. (2000). To educate in values. theory and practice. UC Edition.

- What Are Family Values...

What Are Family Values Exactly and Are They Important?

by Rick Stephens

What are family values? Do they differ from other values? Are they important? Do you need them? Can they change? Most parents trying to raise thoughtful and responsible kids find themselves asking these kinds of questions more often than you might think.

Most of us believe we are clear on our values and generally live our lives accordingly. But then we get married and perhaps have children. Suddenly, we’re tested in all kinds of ways, making some small and some very large decisions that affect our partners and our kids. It’s then that we realize our priorities might have to change.

For some, that comes easily. For others, it can be a difficult evolution. At Raising Families, we talk about values and family values a lot. We want to make sure you’re clear on what exactly family values are and why they’re important.

Personal Values Help You Make Decisions

Personal values are the characteristics or habits that motivate us to make a particular decision or act one way or another. Whether we consciously think about it or not, we all have our own values that guide the decisions we make and how we live day-to-day.

Our values provide the foundation for nearly all decisions we make as individuals and as parents. They determine our priorities and often are the measure by which we decide if we are living our best life. That’s why it matters that we become familiar with our true values and figure out if those are family values we want to pass on to our children.

What Are Family Values?

Family values are the values you and your partner intentionally or unintentionally use to guide your family. These are most likely a combination of your and your partner’s personal values. And yes, they can absolutely change over time as your children mature and you both gain wisdom and insight as parents.

Even if you haven’t had a discussion with your partner or as a family about the values you believe are important for your family, you’ve been basing the family decisions on your family values. These can include decisions about what you do together, where you live, and how you spend the family money.

Here are some examples of both personal and/or family values:

- Love and respect for others

- Honesty and openness

- Patience or tolerance

- Forgiveness

- The importance of hard work

- Flexibility

- Wanting to learn

- Spirituality

- Importance of education

- Personal accountability

Personal and Family Values Aren’t Always the Same

Your family values will most likely overlap with your personal ones, but they can include different ones as well. Personal values at work may not be appropriate to the family setting. Maybe you value being right and having the last word in your business environment, but you may soon find that children play by different rules than employees.

Do you value having quiet and obedient children? Or do you want them to feel seen and heard and be intrinsically motivated to contribute to the family team? You may want to revise your priority of being right and instead prioritize connection before correction.

That may look like you doing the internal work to stop yelling at your children for minor mistakes (valuing control and being right) and instead finding a way to take a breath and work on problem-solving together (valuing your relationship more than rule following).

Maybe you’re fine (prefer even) eating lunch by yourself and scrolling social media every day at work. At home, however, you feel strongly that eating together as a family each night is an important tradition. It makes you feel like a good parent, so you make a commitment to share that time, free of cell phones and other distractions.

Understanding our personal values raises our level of self-awareness and helps us to be more thoughtful and intentional with our children and partners. Ultimately that makes for happier, more cooperative, and higher functioning families.

How Family Influences Your Values

Values will be different for everyone. Your personal and family values are based on things that you’ve been exposed to and that influence you. You can get your values from your parents, your beliefs, the media, or the experiences you’ve had, to name a few.

Your family can be one of the most influential things when it comes to developing your own values, which is one of the reasons it’s so important to be intentional with your family values. Even without meaning to, you are passing on your values to your children in an unconscious way through everyday interactions, simple conversations, and how you use your resources like time, money, and attention. This can create a problem if your children often spend time with extended family and their values don’t align with your family values .

Why Family Values Are Important

Whether you’ve intentionally thought about your family values or not, you have them. If you don’t intentionally decide on what your family values are, you end up making decisions that ultimately impact your entire family based on things that may not be important to you or your family.

Another way of saying it is your family values represent what your family judges to be important in life. If your family believes something is important, you’ll spend time and money to acquire it. If not, your family won’t care as much about having it.

Your finances, time, and emotional stamina can be invested in any number of ways. The key to living an intentional and fulfilled life is to align those investments with your family values.

One of the keys to a prosperous and harmonious family life is aligning those values with those of your partner. If you aren’t sure what your values are or whether or not they’re aligned with your partner’s, take a look at your actions. Your actions reflect what you value. Are your actions consistent with what you believe your values are? If not, how can you change your actions to show what you do value?

If you know that your actions, the results of your decisions, are rooted in your values, then it only follows that what you experience in life is directly related to those values.

Just because you say you value something doesn’t mean your actions support it. With new awareness, however, you have the power to make changes in the right direction.

It is paramount that you talk as a family team about your values, why you make the decisions you do, what’s most important to you, and whether your values are really in sync with your behaviors. Remember, values are the root of everything.

Values Are At the Root of Everything

A workbook for parents to identify and align their family values around money, time, and emotional resources.

- Designed for parents to do together

- 16 page PDF workbook

- Includes four simple exercises to do together

What To Do Next

1. read more in the blog:.

The Family Wisdom Blog shares valuable ideas across diverse topics.

2. Explore the Printables Library:

Our printables library is filled with must-have activity ideas, checklists, guides, and workbooks.

3. Subscribe to Our Newsletter:

Sign up for our newsletter for parenting tips to help you create the family team you've always wanted.

More to Explore

8 Things You Can Do to Stop Kids from Lying

3 Things to Help Your Kids Turn Dreams into Reality

4 Simple Ways to Encourage Children to Read More

Rick Stephens

Rick Stephens is a co-founder of Raising Families. With 33 years of experience as a top-level executive at The Boeing Company and having raised four children of his own, he is able to support parents and grandparents by incorporating his knowledge of business, leadership, and complex systems into the family setting.

In his free time Rick enjoys road biking, scuba diving, visiting his grandkids, and generally trying to figure out which time zone he’s in this week. Read full bio >>

Essay about Family: What It Is and How to Nail It

Humans naturally seek belonging within families, finding comfort in knowing someone always cares. Yet, families can also stir up insecurities and mental health struggles.

Family dynamics continue to intrigue researchers across different fields. Every year, new studies explore how these relationships shape our minds and emotions.

In this article, our dissertation service will guide you through writing a family essay. You can also dive into our list of topics for inspiration and explore some standout examples to spark your creativity.

What is Family Essay

A family essay takes a close look at the bonds and experiences within families. It's a common academic assignment, especially in subjects like sociology, psychology, and literature.

.webp)

So, what's involved exactly? Simply put, it's an exploration of what family signifies to you. You might reflect on cherished family memories or contemplate the portrayal of families in various media.

What sets a family essay apart is its personal touch. It allows you to express your own thoughts and experiences. Moreover, it's versatile – you can analyze family dynamics, reminisce about family customs, or explore other facets of familial life.

If you're feeling uncertain about how to write an essay about family, don't worry; you can explore different perspectives and select topics that resonate with various aspects of family life.

Tips For Writing An Essay On Family Topics

A family essay typically follows a free-form style, unless specified otherwise, and adheres to the classic 5-paragraph structure. As you jot down your thoughts, aim to infuse your essay with inspiration and the essence of creative writing, unless your family essay topics lean towards complexity or science.

.webp)

Here are some easy-to-follow tips from our essay service experts:

- Focus on a Specific Aspect: Instead of a broad overview, delve into a specific angle that piques your interest, such as exploring how birth order influences sibling dynamics or examining the evolving role of grandparents in modern families.

- Share Personal Anecdotes: Start your family essay introduction with a personal touch by sharing stories from your own experiences. Whether it's about a favorite tradition, a special trip, or a tough time, these stories make your writing more interesting.

- Use Real-life Examples: Illustrate your points with concrete examples or anecdotes. Draw from sources like movies, books, historical events, or personal interviews to bring your ideas to life.

- Explore Cultural Diversity: Consider the diverse array of family structures across different cultures. Compare traditional values, extended family systems, or the unique hurdles faced by multicultural families.

- Take a Stance: Engage with contentious topics such as homeschooling, reproductive technologies, or governmental policies impacting families. Ensure your arguments are supported by solid evidence.

- Delve into Psychology: Explore the psychological underpinnings of family dynamics, touching on concepts like attachment theory, childhood trauma, or patterns of dysfunction within families.

- Emphasize Positivity: Share uplifting stories of families overcoming adversity or discuss strategies for nurturing strong, supportive family bonds.

- Offer Practical Solutions: Wrap up your essay by proposing actionable solutions to common family challenges, such as fostering better communication, achieving work-life balance, or advocating for family-friendly policies.

Family Essay Topics

When it comes to writing, essay topics about family are often considered easier because we're intimately familiar with our own families. The more you understand about your family dynamics, traditions, and experiences, the clearer your ideas become.

If you're feeling uninspired or unsure of where to start, don't worry! Below, we have compiled a list of good family essay topics to help get your creative juices flowing. Whether you're assigned this type of essay or simply want to explore the topic, these suggestions from our history essay writer are tailored to spark your imagination and prompt meaningful reflection on different aspects of family life.

So, take a moment to peruse the list. Choose the essay topics about family that resonate most with you. Then, dive in and start exploring your family's stories, traditions, and connections through your writing.

- Supporting Family Through Tough Times

- Staying Connected with Relatives

- Empathy and Compassion in Family Life

- Strengthening Bonds Through Family Gatherings

- Quality Time with Family: How Vital Is It?

- Navigating Family Relationships Across Generations

- Learning Kindness and Generosity in a Large Family

- Communication in Healthy Family Dynamics

- Forgiveness in Family Conflict Resolution

- Building Trust Among Extended Family

- Defining Family in Today's World

- Understanding Nuclear Family: Various Views and Cultural Differences

- Understanding Family Dynamics: Relationships Within the Family Unit

- What Defines a Family Member?

- Modernizing the Nuclear Family Concept

- Exploring Shared Beliefs Among Family Members

- Evolution of the Concept of Family Love Over Time

- Examining Family Expectations

- Modern Standards and the Idea of an Ideal Family

- Life Experiences and Perceptions of Family Life

- Genetics and Extended Family Connections

- Utilizing Family Trees for Ancestral Links

- The Role of Younger Siblings in Family Dynamics

- Tracing Family History Through Oral Tradition and Genealogy

- Tracing Family Values Through Your Family Tree

- Exploring Your Elder Sister's Legacy in the Family Tree

- Connecting Daily Habits to Family History

- Documenting and Preserving Your Family's Legacy

- Navigating Online Records and DNA Testing for Family History

- Tradition as a Tool for Family Resilience

- Involving Family in Daily Life to Maintain Traditions

- Creating New Traditions for a Small Family

- The Role of Traditions in Family Happiness

- Family Recipes and Bonding at House Parties

- Quality Time: The Secret Tradition for Family Happiness

- The Joy of Cousins Visiting for Christmas

- Including Family in Birthday Celebrations

- Balancing Traditions and Unconditional Love

- Building Family Bonds Through Traditions

Looking for Speedy Assistance With Your College Essays?

Reach out to our skilled writers, and they'll provide you with a top-notch paper that's sure to earn an A+ grade in record time!

Family Essay Example

For a better grasp of the essay on family, our team of skilled writers has crafted a great example. It looks into the subject matter, allowing you to explore and understand the intricacies involved in creating compelling family essays. So, check out our meticulously crafted sample to discover how to craft essays that are not only well-written but also thought-provoking and impactful.

Final Outlook

In wrapping up, let's remember: a family essay gives students a chance to showcase their academic skills and creativity by sharing personal stories. However, it's important to stick to academic standards when writing about these topics. We hope our list of topics sparked your creativity and got you on your way to a reflective journey. And if you hit a rough patch, you can just ask us to ' do my essay for me ' for top-notch results!

Having Trouble with Your Essay on the Family?

Our expert writers are committed to providing you with the best service possible in no time!

FAQs on Writing an Essay about Family

Family essays seem like something school children could be assigned at elementary schools, but family is no less important than climate change for our society today, and therefore it is one of the most central research themes.

Below you will find a list of frequently asked questions on family-related topics. Before you conduct research, scroll through them and find out how to write an essay about your family.

How to Write an Essay About Your Family History?

How to write an essay about a family member, how to write an essay about family and roots, how to write an essay about the importance of family.

Daniel Parker

is a seasoned educational writer focusing on scholarship guidance, research papers, and various forms of academic essays including reflective and narrative essays. His expertise also extends to detailed case studies. A scholar with a background in English Literature and Education, Daniel’s work on EssayPro blog aims to support students in achieving academic excellence and securing scholarships. His hobbies include reading classic literature and participating in academic forums.

is an expert in nursing and healthcare, with a strong background in history, law, and literature. Holding advanced degrees in nursing and public health, his analytical approach and comprehensive knowledge help students navigate complex topics. On EssayPro blog, Adam provides insightful articles on everything from historical analysis to the intricacies of healthcare policies. In his downtime, he enjoys historical documentaries and volunteering at local clinics.

Related Articles

.webp)

Essay on Importance Of Family Values

Students are often asked to write an essay on Importance Of Family Values in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Importance Of Family Values

What are family values.

Family values are the beliefs and ideals that families consider important. They guide how family members treat each other and others outside the family. Common values include honesty, kindness, and respect.

Teaching Respect and Love

Support and strength.

Family values give support. When life is hard, family members help each other. This makes everyone feel strong and able to face challenges.

Guiding Choices

Values help children make good choices. Knowing what is right and wrong helps them grow into responsible adults who can take care of themselves and others.

250 Words Essay on Importance Of Family Values

One important family value is respect. When children learn to respect their parents and siblings, they also learn to respect others. This helps them make friends and do well in school. Love is another key value. When family members show love to one another, they feel safe and happy. This love helps kids grow up to be caring adults.

Families that share strong values give each other support. For example, they help with homework or cheer at sports games. This support makes family members feel strong, even when they face tough times. It also means they have people to turn to for help and advice.

Passing Down Traditions

Family values include traditions, like holiday meals or weekend outings. These traditions create lasting memories and bring everyone closer. They also teach kids about their family’s history and culture, which is important for their identity.

In short, family values are very important. They teach kids how to act, help families support each other, and keep traditions alive. These values shape children into good people and create a loving home where everyone feels they belong.

500 Words Essay on Importance Of Family Values

Family values are the beliefs and ideas that families think are important. They are like a hidden guide that teaches us how to behave, how to tell right from wrong, and how to treat other people. These values include things like being honest, kind, and respectful to others. Just like a tree gets strength from its roots, we get our strength and shape from our family values.

Learning Good Behavior

Feeling safe and loved.

A family that has strong values creates a safe space for everyone. When children feel safe and loved, they grow up to be confident and happy. They know their family will always support them, even when they make mistakes. This feeling of security is like a cozy blanket that keeps us warm and protected.

Helping Each Other

Families with good values help each other, just like a team. When one person is having a tough time, others step in to help. This teaches us that we are not alone and that it is good to help others. It’s like passing the ball in a soccer game so that the team can score a goal.

Respecting Differences

Family values also teach us to respect people who are different from us. In a family, everyone is unique, but they all are loved the same. This helps us understand that in the big world, people may look or think differently, and that’s okay. We learn to treat everyone with kindness, no matter what they look like or believe in.

Working Hard

Staying together in tough times.

Life can sometimes be hard, like a storm that shakes the trees. But just like trees with strong roots stay standing, families with strong values stay together during tough times. They talk to each other, solve problems together, and keep each other strong. This teaches us that no matter what happens, we can get through it if we stick together.

If you’re looking for more, here are essays on other interesting topics:

Apart from these, you can look at all the essays by clicking here .

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

27 Top Family Values Examples (to Strive For)

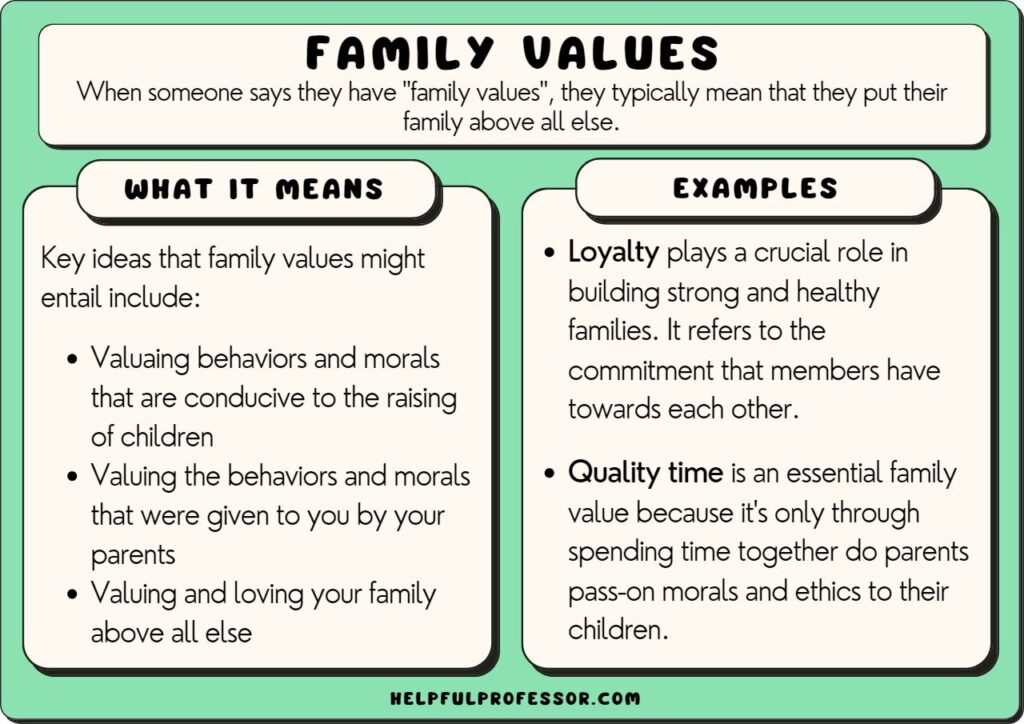

When someone says they have “family values”, they typically mean that they put their family above all else.

Sometimes, family values also refers to the idea that they uphold certain moral and ethical principles that were instilled in them through their childhood by their parents or other family members.

These principles ostensibly guide their behavior, decision-making, and importantly, affect who they will choose to have a relationship with (the idea being that they seek someone else whose personal values embrace the same family values as them).

Definition of Family Values

The term ‘family values’ is vague and contextual to the point you may have to ask the person who says they have family values to unpack what it means to them.

Key ideas that it might entail include:

- Valuaing behaviors and morals that are conducive to the raising of children

- Valuing the behaviors and morals that were given to you by your parents

- Valuing and loving your family above all else

The term is also often used as shorthand to suggest a traditional or conservative perspective on ethics and morality, often associated with strong beliefs in traditional marriage, the importance of the role of the parent, respect for authority figures within the family, and sometimes even religious principles (such as principles about the family found in religious texts or teachings).

For example, someone who adheres to “family values” in a traditional or conservative sense may prioritize a same-sex marriage that can lead to raising children and maintaining a stable family unit. They may place high importance on traditional gender roles within the family. Similarly, there may be a sense of commitment to family activities that are conducive to raising a well-mannered child.

Nevertheless, as I’m sure many of my readers would argue, many people’s idea of ‘family values’ may differ from the conservative image outlined above, and again I’d refer back to the idea that ‘family values’ is a rather vague concept, sometimes to the point of being entirely meaningless beyond saying “I think family is extremely important to me.”

Family Values Examples

The below examples of family values may represent what many people mean when they use the term, but as I hope I’ve already stressed, the term’s vagueness means it is hard to pin-down exactly what someone means when they use the term.

1. Family First

When referring to family values, we’re often referring to the fact that we place family above all else. We need to have this mindset in order to be good providers to our children.

When individuals make a conscious decision to put their families first it sends the message that their loved ones’ well-being takes precedence over other competing interests.

This can manifest itself in various ways – be it spending more quality time together by scheduling regular outings or setting aside time for meaningful bonding activities; making personal adjustments (changing work schedules or geographic location), and ensuring uninterrupted quality time at home even in the face of outside obligations .

Prioritizing family provides emotional support where members can depend on each other for encouragement, guidance and fulfilment of shared values.

Moreover, putting family first lays the foundation for passing down valuable lessons including teamwork, collaboration and empathy towards others – qualities that shape children into emotionally intelligent adults capable of nurturing relationships towards building stronger communities.

Loyalty is a fundamental value that plays a crucial role in building strong and healthy families. It refers to the commitment and dedication that members have towards each other, especially during challenging times.

Loyalty is demonstrated when family members support and defend each other through thick and thin, regardless of their personal opinions or disagreements.

For instance, if one family member faces an adverse situation, all others must come forward without any delay or hesitation to stand by them.

Loyalty also means supporting one another’s goals and aspirations while helping them overcome any obstacles they might encounter along the way.

Moreover, loyalty helps to maintain family bonds even through turbulent times such as financial hardships or unexpected life events such as illnesses or deaths. Having strong relationships with family members ensures no one feels alone in difficult situations resulting in more positive communal outcomes – be it sharing resources or emotional support.

3. Caring for One Another

Caring for one another is an essential family value that facilitates the development of meaningful relationships, support systems, and emotional well-being. It refers to the act of showing concern for each other’s physical, emotional, and social needs.

Caring for one another is demonstrated by sharing responsibilities and helping out in everyday tasks such as cooking a meal together or offering assistance with household chores or errands. The ability to make small gestures shows an interest in contributing to another person’s comfort.

Emotional support is equally important when it comes to caring in a family context. It involves being there for family members through challenging times such as sicknesses, breakups or job losses – offering a listening ear as well as words of encouragement.

Family members who practice compassion and empathy towards each other in all circumstances creates strong bonds within the unit – leading to better mental health outcomes including reduction in stress levels, anxiety or depression.

4. Community

When it’s time to settle down and raise a family, people often return to small towns or tight-knit communities where they can ‘put down roots’. Part of the appeal of this is that you can have a close-knit and safe community in which you can raise your children.

A solid community that cares for its children fosters the creation of supportive and positive social networks beyond the immediate household.

Being part of a community allows family members to form meaningful relationships with others outside their home and provides opportunities to engage in activities that can be beneficial for the entire family. Children learn new things and broaden their horizons from interacting with various members of society including building social skills.

Community involvement teaches children that as members of a larger group, we are responsible towards contributing positively towards the betterment of others too.

5. Quality Time

In today’s fast-paced and technology-driven world, quality time has become an extremely valuable commodity for many families. It refers to the time that family members spend together in meaningful ways, building strong connections and relationships with each other.

Often, when we talk about wanting a partner with family values, we’re using it as a shorthand to say we want to be with someone who has time for their family.

Quality time is also important because it helps to create a sense of security and belonging within the family unit. When children feel loved, valued, and supported by their parents and siblings, they are more likely to develop self-confidence and a positive self-image which makes them emotionally stronger individuals ready for challenges in life.

By spending quality time together, families can also establish traditions that hold significance throughout generations. Simple weekend routines or holiday traditions can be the glue that keeps everyone close-knit even when busy schedules may be pulling them apart.

Related: The 8 Types of Values

It is very common to hear the phrase ‘family values’ being promoted by religious adherents, whereby they believe their religion teaches values that are conducive to a good family life.

Religion can provide a sense of structure and order within family life, with regular attendance at services, prayer, or other rituals creating an anchor or routine for families to come back to.

Having a shared faith can also promote strong moral and ethical principles among family members. Faith-based values such as love, forgiveness, compassion and humility become central tenets within families that help guide them in making decisions throughout life.

7. Hard Work

Hard work and work ethic are important family values that emphasize the importance of diligence, perseverance, and responsibility towards one’s professional or personal goals .

This value embodies the discipline to continuously strive for success by setting and achieving measurable targets as a marking of progress.

Teaching hard work within families can set children on the path to establishing a successful life and avoiding a path of delinquence. They learn that sustained commitment is required beyond any instant gratification periods in order to achieve long term rewards.

Work ethic also helps instill a sense of pride and accomplishment when meeting targets and achieving desired results thereby increasing self-esteem.

Moreover, embodying this value teaches children discipline necessary for both academic pursuits as well as any personal projects they may undertake in life – hobbies that bring them joy too!

As parents model industrious behavior within their careers it sets an example for their children about financial management – showing how only diligent effort can lead to their dreams being met.

Honesty is a critical family value that emphasizes the importance of having truthfulness, integrity and transparency in all interactions and relationships within the immediate household.

Honesty ensures that every individual understands the value of telling the truth, being transparent in their communication, actions or even intentions. This involvement strengthens emotional ties and builds a solid foundation of trust – one where mutual respect thrives.

By establishing honesty as a core family value, parents or guardians can set an example for how children communicate with each other.

They understand that dishonest behavior damages foundations of communication – creating strife- leading to difficulty problem solving – thereby making interpersonal relationships challenging overt time.

Moreover, imparts important life skills- understanding personal ownership of consequences while boosting self-awareness beyond just instant gratification living.

Honesty reinforces community values by demonstrating appropriate ways to navigate difficult conversations and maintain a strong reputation within your work and social environments.

Respectfulness highlights the significance of treating each other with courtesy, consideration and equality.

When family members treat each other with respect, it leads to better communication, better understanding and more positive engagement in day-to-day activities. This is because everyone feels valued and appreciated which helps foster good relations among everybody irrespective of differences that may exist.

Respect in a family context also involves recognizing individual choices and genuinely considering the opinions of each family member during shared decision-making processes- whether big or small.

When all members feel heard and considered when varying viewpoints are given fair weightage it results in more productive outcomes.

Moreover, fostering respect helps instill an environment for children where they are encouraged to be kind towards others, promoting empathy and strong character development.

10. Accountability

Accountability as a family value refers to the idea that family members should be responsible for their actions and decisions, and are willing to accept the consequences of those actions.

One of the ways in which accountability becomes a family value is through communication. When family members communicate openly and honestly with each other, they are more likely to hold themselves accountable for their behavior.

For example, if one family member makes a mistake or behaves inappropriately, they should be held accountable by others in the family who are affected by their actions.

Another way in which accountability can become a family value is by setting clear expectations and boundaries.

Parents need to establish rules and guidelines for behavior within the family unit so that everyone knows what is expected of them. When these expectations are violated, it is important for there to be consequences that reinforce the importance of being accountable.

When accountability becomes one of the core values of a family unit, it not only leads to better communication but also helps build strong relationships based on mutual trust and respect.

Additional Family Values

- Forgiveness

- Open-mindedness

- Self-reliance

- Cooperation

- Self-discipline

Related Article: The Sociology of Values (Why do we have values, anyway?)

While the term ‘family values’ is vague and depends upon the person using it, it generally points toward a mindset of a person whose personal qualities are rooted in family. For these people, family comes above all else, and they behave in a way that is conducive to raising children in a wholesome, safe, and morally upstanding environment. While all families need to come up with their own set of values to live by, generally, if a person says they seek a mate with good family values, they’ll be looking for someone with love and loyalty to their family before anything else.

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 15 Self-Actualization Examples (Maslow's Hierarchy)

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ Forest Schools Philosophy & Curriculum, Explained!

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ Montessori's 4 Planes of Development, Explained!

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ Montessori vs Reggio Emilia vs Steiner-Waldorf vs Froebel

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

How it works

Transform your enterprise with the scalable mindsets, skills, & behavior change that drive performance.

Explore how BetterUp connects to your core business systems.

We pair AI with the latest in human-centered coaching to drive powerful, lasting learning and behavior change.

Build leaders that accelerate team performance and engagement.

Unlock performance potential at scale with AI-powered curated growth journeys.

Build resilience, well-being and agility to drive performance across your entire enterprise.

Transform your business, starting with your sales leaders.

Unlock business impact from the top with executive coaching.

Foster a culture of inclusion and belonging.

Accelerate the performance and potential of your agencies and employees.

See how innovative organizations use BetterUp to build a thriving workforce.

Discover how BetterUp measurably impacts key business outcomes for organizations like yours.

A demo is the first step to transforming your business. Meet with us to develop a plan for attaining your goals.

- What is coaching?

Learn how 1:1 coaching works, who its for, and if it's right for you.

Accelerate your personal and professional growth with the expert guidance of a BetterUp Coach.

Types of Coaching

Navigate career transitions, accelerate your professional growth, and achieve your career goals with expert coaching.

Enhance your communication skills for better personal and professional relationships, with tailored coaching that focuses on your needs.

Find balance, resilience, and well-being in all areas of your life with holistic coaching designed to empower you.

Discover your perfect match : Take our 5-minute assessment and let us pair you with one of our top Coaches tailored just for you.

Research, expert insights, and resources to develop courageous leaders within your organization.

Best practices, research, and tools to fuel individual and business growth.

View on-demand BetterUp events and learn about upcoming live discussions.

The latest insights and ideas for building a high-performing workplace.

- BetterUp Briefing

The online magazine that helps you understand tomorrow's workforce trends, today.

Innovative research featured in peer-reviewed journals, press, and more.

Founded in 2022 to deepen the understanding of the intersection of well-being, purpose, and performance

We're on a mission to help everyone live with clarity, purpose, and passion.

Join us and create impactful change.

Read the buzz about BetterUp.

Meet the leadership that's passionate about empowering your workforce.

For Business

For Individuals

How to instill family values that align with your own

Jump to section

What are family values?

Why family values are important, how do family values affect society, types of family values, 8 family value examples, how to instill values in your family, how family values transfer to the workplace, uncover and implement family values that matter to you.

A huge chunk of your day is spent at work. But for many people, most of their time outside of work is spent with their families.

How that time is spent — and the quality of that time — is often informed by family values.

Not all families consciously instill values in their members. Often, family values get passed down from generation to generation implicitly. Those values don’t ever get questioned, even if they’re not the right fit for the current generation.

But family values have the power to shape the people you, your partner, your children, and anyone else who is part of your family unit. Whether you’ve explicitly outlined those values or not, they’re present. And once you take ownership of those values, you can shape them to be in line with what you envision your family to be.

Let’s define family values, why they’re important, and how you can instill them into your family starting today.

Family values are similar to personal values or work values , but they include the entire family. Regardless of what your family looks like, how many parents and children it may (or may not include), these values inform family life and how you deal with challenges as a unit.

They also establish the value system under which children grow up and everyone (old and young) mature and develop as individuals. Family values can guide your entire family to become the kind of people you want to be. And ultimately, if your family includes children, family values can have a huge influence on child-rearing.

These values don’t necessarily have to be focused on child-rearing. They can be aligned with whatever your family most believes in. For example, a family can prioritize quality time together instead of pursuing careers that consume most of your time. This is valid even without children to care for. Family members of all ages are worthy of quality time.

Whenever someone in your family goes through a teachable moment, your family values will shine through. This is true whether those values are intentional or not.

Here’s how family values contribute to your loved ones and relationships.

1. They guide family decisions

Family values define what you and the other people in your family consider to be right or wrong. These values can help you stay consistent when making decisions in everyday life. They can also guide those decisions in moments of uncertainty.

This is especially true when you’re tempted to make rash decisions based on an emotional reaction . When you have clearly established family values, you can take a step back. Instead of acting impulsively, what do your values suggest is the right course of action?

For instance, how do you deal with someone who has lied to another family member? How do you set boundaries with your partner and with younger children in the family unit?

2. They provide clarity and structure

Children learn by modeling what the people around them do. Because of the plasticity of their brains , they can adapt and change depending on what environment they grow up in.

When their parents or guardians follow a set of clear values, they have clarity on what is right and wrong. Values give them structure and boundaries within which they can thrive.

On the other hand, unclear values can create inconsistencies for children. They may struggle to figure out right from wrong if their family values constantly change.

And while you may have clear personal values, other adults in the family may have completely different values. When those values clash, it can be confusing for the children involved.

Defining your family values helps avoid confusion and creates a clear definition of right and wrong.

3. They help your family achieve a sense of identity

Growing up is difficult. Children are constantly trying to figure out who they are and who they want to be. And because their brains aren’t fully developed yet, this process can be grueling on its own.

When you add in the other challenges that life can throw at them, you can imagine how hard it is to grow up.

Clear family values can help children build a sense of identity. While the rest of the world around them is uncertain, they know they can rely on their family values to identify themselves.

Family values can also give the family its own sense of identity as a family unit.

4. They improve communication among family members

When values are clear, communication is easier . Everyone is on the same page. All family members are working with the same definition of right and wrong.

It’s much easier to have productive conversations when there isn’t any ambiguity in values. This can help maintain a healthy family dynamic.

Family values are the roots of the next generation. They inform what kind of people our future decision-makers will grow up to become.

For example, if several families implement generosity in their values, the next generation will grow up to be more generous. As a result, adults in this generation are more likely to take other people’s needs into consideration when making important decisions.

While younger generations are still growing up, they’ll one day be the ones holding positions of power.

They’ll also be the ones to raise the next generation of young people when they have their own families.

In that sense, family values are one of the most impactful components of society. Even if you don’t yet see the connection, your family values are directly connected to how society will evolve .

Most core values for families fall into specific categories.

Here are five types of family values that all families should establish. Not all families will have the same approach to these values, but defining them is important.

1. Relationship to others

Your family likely has a set of values that dictate how to behave around others. These values can also define how you develop relationships with other people .

You don’t just have to define values for how you want to treat the people you have close relationships with. How do you and your family believe you should treat other people in general, including strangers?

Some families believe everyone deserves respect. Other families believe this respect needs to be earned first.

How your family views their relationships with others can also help you determine how to handle unpleasant situations. For instance, how would you deal with children in your family being bullied? Or, how would you react if children in your family bullied someone else?

And how do you treat relationships with your extended family?

These are all important questions to consider when establishing your family values.

2. Relationship with each other

In some cases, the way you handle family relationships will differ from how you handle outside relationships.

For instance, some families work under the assumption that family comes first, no matter what. Other families prefer a more egalitarian approach .

In either case, it’s important to define values that determine how family members treat each other. These values can define:

- How children should act with each other

- How children should act toward their parents

- How spouses deal with their children (how child care is handled)

- How spouses treat each other

- How parents co-parent

3. Relationship to oneself

Family values can set rules for how to treat others, in and out of the family. But they can also guide how every person treats themselves .

How should individuals act when they’ve done something wrong? What should they do when they’re having a bad day or having a hard time dealing with their emotions ?

Values about how to treat oneself can often be forgotten or set aside. But how you treat yourself is just as important as the way you treat others.

4. Priorities

What does your family prioritize? Some values can define what matters to your family first and what’s less important.

Some examples include:

- How you spend family time

- What spiritual or religious rituals matter to your family

- What type of education you’ll provide for your children

- How you deal with holiday stress

- How you create traditions and celebrate different cultures