Essay on Good and Bad Effects of Mobile Phones

Students are often asked to write an essay on Good and Bad Effects of Mobile Phones in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Good and Bad Effects of Mobile Phones

Introduction.

Mobile phones have become an integral part of our lives. They offer numerous benefits but also have some negative impacts.

Good Effects of Mobile Phones

Mobile phones improve communication. They allow us to stay connected with our family and friends. They also provide access to a wealth of information and educational resources.

Bad Effects of Mobile Phones

However, excessive use of mobile phones can lead to health issues like eye strain and sleep disturbances. It can also cause addiction, reducing physical activity and face-to-face social interaction.

In conclusion, while mobile phones have their advantages, their misuse can lead to several problems. It’s important to use them responsibly.

250 Words Essay on Good and Bad Effects of Mobile Phones

Mobile phones, an indispensable part of our lives, have transformed the way we communicate, access, and share information. However, they come with their set of pros and cons which significantly impact our lives.

Positive Impacts of Mobile Phones

Mobile phones have revolutionized communication, making it instantaneous and borderless. They facilitate social connectivity, enabling us to maintain relationships across distances. Besides, they have become a one-stop solution for various needs, from online shopping and banking to learning and entertainment.

Moreover, smartphones have paved the way for a plethora of applications, including those for health and fitness, mental well-being, and productivity enhancement. They have democratized access to information, empowering individuals to make informed decisions and contribute to societal progress.

Negative Impacts of Mobile Phones

Despite their benefits, mobile phones have a downside. Over-reliance on these devices has led to addictive behaviors, impacting physical and mental health. Excessive screen time can lead to eye strain, sleep disorders, and sedentary lifestyle-related problems.

Furthermore, the constant barrage of notifications can cause anxiety and stress, leading to decreased productivity. Mobile phones also raise privacy concerns, as they can be used for unauthorized data collection and surveillance. Cyberbullying and online harassment have become prevalent with the ubiquity of smartphones, posing serious threats to mental health and safety.

In conclusion, while mobile phones have made life more convenient and connected, they have also introduced new challenges. It is essential to use these devices judiciously, balancing their benefits with potential hazards to ensure a healthy and productive life.

500 Words Essay on Good and Bad Effects of Mobile Phones

Mobile phones, once a luxury, have become a necessity in the modern world. These devices have revolutionized communication, enabling us to connect with others swiftly and efficiently. However, their pervasive influence has sparked a debate about the good and bad effects they have on our lives.

The Good Effects of Mobile Phones

Mobile phones have undoubtedly brought about numerous positive impacts. Firstly, they have transformed communication. We can now connect with anyone, anywhere, at any time, breaking down geographical barriers and fostering global connectivity. This has made it easier for businesses to operate internationally, for families to stay in touch, and for emergencies to be reported instantly.

Secondly, mobile phones have become a hub for information and entertainment. With the advent of smartphones, we now have a world of knowledge at our fingertips. From online education to news updates, from music streaming to movie watching, our phones serve as portals to limitless information and entertainment.

Thirdly, mobile phones have facilitated convenience in our daily lives. They serve as calendars, alarm clocks, and personal assistants. They allow us to shop online, manage our finances, track our health, and even navigate unfamiliar locations. The convenience offered by mobile phones is unparalleled.

The Bad Effects of Mobile Phones

Despite these benefits, mobile phones also have their drawbacks. One of the most significant is their contribution to decreased physical interaction. As people become more engrossed in their virtual worlds, face-to-face communication is being replaced by digital interaction, leading to a decline in essential social skills.

Moreover, excessive use of mobile phones has been linked to various health issues. These range from physical problems like poor posture and eye strain to psychological problems such as addiction, anxiety, and depression. The blue light emitted by phone screens can disrupt sleep patterns, leading to insomnia and other sleep disorders.

Furthermore, the ubiquity of mobile phones has raised serious concerns about privacy and security. Personal information can be easily accessed and misused, leading to potential identity theft and cybercrime. The constant connectivity also means that we are always reachable, blurring the boundaries between work and personal life and leading to increased stress levels.

In conclusion, while mobile phones have undoubtedly made our lives easier and more connected, they also pose significant challenges. It is crucial to strike a balance between leveraging the benefits of these devices and mitigating their adverse effects. By using mobile phones mindfully and responsibly, we can harness their power for good while minimizing their potential harm.

That’s it! I hope the essay helped you.

If you’re looking for more, here are essays on other interesting topics:

- Essay on Effect of Mobile Phones on Students

- Essay on Benefits of Mobile Phones

- Essay on Internet a Wonderful Gift of Science

Apart from these, you can look at all the essays by clicking here .

Happy studying!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Uses of Mobile Phones Essay for Students and Children

500+ words essay on uses of mobile phones.

Mobile phones are one of the most commonly used gadgets in today’s world. Everyone from a child to an adult uses mobile phones these days. They are indeed very useful and help us in so many ways.

Mobile phones indeed make our lives easy and convenient but at what cost? They are a blessing only till we use it correctly. As when we use them for more than a fixed time, they become harmful for us.

Uses of Mobile Phone

We use mobile phones for almost everything now. Gone are the days when we used them for only calling. Now, our lives revolve around it. They come in use for communicating through voice, messages, and mails. We can also surf the internet using a phone. Most importantly, we also click photos and record videos through our mobile’s camera.

The phones of this age are known as smartphones . They are no less than a computer and sometimes even more. You can video call people using this phone, and also manage your official documents. You get the chance to use social media and play music through it.

Moreover, we see how mobile phones have replaced computers and laptops . We carry out all the tasks through mobile phones which we initially did use our computers. We can even make powerpoint presentations on our phones and use it as a calculator to ease our work.

Get the huge list of more than 500 Essay Topics and Ideas

Disadvantages of Mobile Phones

While mobile phones are very beneficial, they also come to a lot of disadvantages. Firstly, they create a distance between people. As people spend time on their phones, they don’t talk to each other much. People will sit in the same room and be busy on their phones instead of talking to each other.

Subsequently, phones waste a lot of time. People get distracted by them easily and spend hours on their phones. They are becoming dumber while using smartphones . They do not do their work and focus on using phones.

Most importantly, mobile phones are a cause of many ailments. When we use phones for a long time, our eyesight gets weaker. They cause strain on our brains. We also suffer from headaches, watery eyes, sleeplessness and more.

Moreover, mobile phones have created a lack of privacy in people’s lives. As all your information is stored on your phone and social media , anyone can access it easily. We become vulnerable to hackers. Also, mobile phones consume a lot of money. They are anyway expensive and to top it, we buy expensive gadgets to enhance our user experience.

In short, we see how it is both a bane and a boon. It depends on us how we can use it to our advantage. We must limit our usage of mobile phones and not let it control us. As mobile phones are taking over our lives, we must know when to draw the line. After all, we are the owners and not the smartphone.

FAQs on Uses of Mobile Phones

Q.1 How do mobile phones help us?

A.1 Mobile phones are very advantageous. They help us in making our lives easy and convenient. They help us communicate with our loved ones and carry out our work efficiently. Furthermore, they also do the work of the computer, calculator, and cameras.

Q.2 What is the abuse of mobile phone use?

A.2 People are nowadays not using but abusing mobile phones. They are using them endlessly which is ruining their lives. They are the cause of many ailments. They distract us and keep us away from important work. Moreover, they also compromise with our privacy making us vulnerable to hackers.

Customize your course in 30 seconds

Which class are you in.

- Travelling Essay

- Picnic Essay

- Our Country Essay

- My Parents Essay

- Essay on Favourite Personality

- Essay on Memorable Day of My Life

- Essay on Knowledge is Power

- Essay on Gurpurab

- Essay on My Favourite Season

- Essay on Types of Sports

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Download the App

Increase in the Use of Mobile Phones and it’s Effects on Young People Report (Assessment)

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Introduction

Mobile phones are increasingly becoming an integral constituent of society with young people, in particular, embracing the technology that has come to be associated with a multiplicity of positive and negative consequences (Suss & Waller 2011).

Emerging trends from the developed world demonstrate that the youth have the highest levels of mobile phone ownership across all age-groups and are prolific consumers of the technology (Walsh et al 2008), and the situation is marginally different in most developing countries where markets for mobile phones have been phenomenal (Thomee et al 2011).

Responsible use of these devices has been associated with desirable outcomes, such as increased feeling of belonging, better social identification and a stronger perception of security, but addictive use is often associated with undesirable outcomes which borders on stress, peer pressure, dilution of the social fabric or mobile phone dependence (Suss & Waller 2011).

For instance, younger drivers engage more on the use of mobile phone while driving, particularly to send and receive text messages, thereby endangering their lives, and mobile phone debt, occasionally leading to bankruptcy, is increasingly becoming a big challenge for many young users globally (Walsh et al, 2008).

It is indeed true that the youth form a significant component of the general population even though it is challenging to delineate this particular group, primarily because of the fact that the phase of life between childhood and adulthood differs across geographical and sociocultural contexts, not mentioning that an individual’s maturity may not necessarily correspond the number of years lived (Campbell, 2005).

Yet, it is this group of the population that is most at risk due to usage patterns coupled with an insatiable appetite to discover more about the world, of course through the use of mobile phones and other handheld devices. An emerging strand of literature (e.g., Walker et al, 2011; Thomee et al, 2011) reports of ‘addictive’ forms of mobile use, especially among the young people, in ways that have the capacity not only to destroy relationships and careers but also weaken the social fabric that holds society together.

The purpose of the present paper is to critically evaluate the effects, both positive and negative, of increased use of mobile phones on young people, and how these effects can be mitigated to avoid negative ramifications. The paper also seeks to explain the physical and physiological effects of excessive use of mobile phones on young people. Finally, the report seeks to illuminate some important insights into the social effects of mobile phones on young people.

Challenges and Effects of Excessive Use of Mobile Phones on Young People

Mobile phones are hand-held portable devices that use analogue or digital frameworks to receive frequencies transmitted by cellular towers or base stations to connect to connect calls and other services between two gadgets (Thomee et al 2011).

The gadgets have the capacity, not only to make and receive calls but also to access other services, such as text messaging (SMS), multimedia messaging (MMS), email alerts, web access, Bluetooth and infrared compatibility and functionality, business software applications, games and photo editing (Khan 2008).

Academics and industry are of the opinion that these additional services provided by mobile telephones form fertile grounds for excessive use and misuse of the gadgets, particularly by the young people (Walker et al, 2011). For instance, smart phones, which are the ‘in-thing’ for many young people across the world, offer the real possibility of accessing all these capabilities just by a single touch of the screen, thereby providing an easy channel through which young people continually engage in overuse and misuse of these services.

While some young people use the internet-enabled mobile phones to access pornographic sites containing sexually explicit materials (Abbasi & Manawar, 2011), others use the webcams installed on their phones to capture sexual images and forward them to their friends through cyberspace (Thomee et al, 2011).

According to Walker et al (2011), “…these images then become part of a young person’s digital footprint, which may last forever and damage future career prospects and relationships” (p. 9). As noted elsewhere, pornographic sites may provide the impetus for young people to start engaging in premarital or irresponsible sex (OECD/ECMT Transport Research Centre 2006).

Physical, Psychological and Physiological Effects of Excessive Use of Mobile Phones

Mobile phone dependence has been cited in the literature as contributing to negative physical and physiological ramifications on young people (Thomee et al 2011). These authors note that there exist positive correlations between mobile phone dependence on the one hand, and stress, sleeps disturbances, and enhanced symptoms of depression on the other.

Still, another study reported in Abbasi & Manawar (2011) demonstrates a positive correlation between excessive mobile phone use and undesirable psychological and physiological behavior outcomes, such as agitation, dependence on stimulants, irresponsible lifestyle, difficulty in sleeping, sleep disruption, and stress vulnerability.

Young people are more likely than old people to feel the pressure arising from these undesirable outcomes, not only because of their weak conflict-resolution mechanisms but also because their brains are not developed fully to maturity (Walker et al 2011; Walsh et al 2011), leading to the engagement of other equally risky behaviors, such as smoking, sniffing and alcohol abuse (Thomee et al 2011).

Available literature demonstrates that browsing of phonographic material via internet-enabled hand-held devices has negative psychological ramifications on young people, particularly in terms of seeking for immediate sexual gratification and blurred thought system (Walker et al 2011; Abbasi & Manawar 2011). These predispositions, according to the authors, may eventually lead to sexual disorders, stress, sexual dysfunction and risk of facing criminal charges due to engaging in prohibited content.

There is an emerging concern about the potential hazards that electromagnetic waves emitted by mobile phones pose to the health and wellbeing of users, particularly in the development of cancerous brain tumors (Khan 2008). One particular study reported by the National Cancer Institute (2011) found that people who engage in dependent mobile phone use before celebrating their 20 th birthday have more than 50 percent risk of suffering from cancer of the glial cells than those who didn’t engage in the behavior.

Additionally, as reported in this document, individuals who become over dependent on mobile phone use while still in their formative years of life have over 50 percent risk of developing benign, but often immobilizing, lumps of the auditory nerve (acoustic neuroma) than those who didn’t engage in the habit.

Social effects

On the positive front, mobiles phones have been credited for assisting young people to socialize with their peers and establish virtual relationships which are oiled by the ease and availability of the communication process (Walsh et al 2010). Young people are now more than ever before able to organize and maintain a social network, and to interact effectively with their peers (Campbell 2005).

In addition, young people can now benefit from the immense knowledge and information that could be readily accessed through their internet-enabled phones (Khan 2008). Lastly, parents are able to keep track of their children (Ong 2010).

However, these benefits are often blurred by the many negative effects associated with excessive mobile phone use, such as cyber bullying and deterioration of face-to-face interpersonal relationships (Campbell 2005; Abbasi & Manawar 2011; Khan 2008).

Research demonstrates that compared to physical interpersonal socialization, cyber bullying is a more injurious orientation as it can distract an individual from facing the real social issues – both physically and psychologically (Thomee et al 2011). Additionally, excessive use of mobile phones leads to social alienation, where young people spend a lot of time talking to absent friends while ignoring those people around them (Ong 2010).

The issue of etiquette in mobile phone use is also been overlooked by many young people, leading to scenarios where users may either create distractions to other people in the communication process, or where mobile phone usage becomes an environmental risk (Khan 2008). For instance, young people are known to create distractions in banking halls, educational settings and even in home meetings by making and receiving calls in surroundings that do not warrant such use (Thomee et al 2011).

Finally, according to Kamran (2010), “…one of the major negative consequences of addictive mobile use is financial cost or really expensive mobile phone bills” (p. 27). The heavy financial burden may lead the youth to engage in petty crimes, such as stealing money from their parents to buy credit so that they can communicate with their peers.

Not only is it evident that mobile phone use has both desirable and undesirable outcomes on young people, but it has been demonstrated beyond doubt that this group of the population has an orientation to over depend on the gadgets.

To mitigate these effects, therefore, it is imperative for relevant stakeholders, including the youth, parents, mobile phone service providers and governments, to devise strategies of ensuring responsible and controlled use of the devices, particularly by young people. Such strategies are ostensibly instrumental in limiting the serious health, psychological, physiological and social challenges posed by excessive use of these gadgets.

As suggested in a report by the Center on Media and Child Health (2010), the negative effects associated with excessive mobile phone use, particularly among the youth, are bound to increase in the future. Consequently, parents and other interested stakeholders need to create awareness about the need to limit mobile phone use due to the consequences associated with excessive use of these devices (Khan 2008).

Young people also need to be educated on the responsible use of mobile phones. Lastly, school administrators need to be empowered not only to effectively monitor the use of these gadgets but also to pass critical information about the inherent dangers posed by overuse (Center on Media and Child Health 2010).

Reference list

Abbasi S. & Manawar, M. 2011, ‘Multi-dimensional challenges facing digital youth and their consequences’, Cybersecurity Summit, London, June 2011 , Worldwide Group.

Campbell, M. 2005, ‘The impact of the mobile phone on young people’s social life’, in Social Change in the 21st Century , Queensland University of Technology, pp.1-14.

Center of Media and Child Health. 2010. Web.

Kamran, S. 2010, ‘Mobile phone: Calling and texting patterns of college students in Pakistan’, International Journal of Business and Management , vol. 5 no. 4, pp. 26-36.

Khan, M. M. 2008, ‘Adverse effects of excessive mobile phone use’, International Journal of Occupational Medicine and Environmental Health , vol. 21 no. 4, pp. 289-293.

National Cancer Institute 2011, Cell phones and cancer risk . Web.

OECD/ECMT Transport Research Centre, European Conference of Ministers of Transport, Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, United Nations. Economic Commission for Europe 2006, Young drivers: the road to safety , OECD Publishing.

Ong, R. Y. C. 2010, Mobile communication and the protection of children , Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Thomee, S., Harenstam, A. & Hagberg, M. 2011, ‘Mobile phone use and stress, sleep disturbances, and symptoms of depression – a prospective cohort study’, BMC Public Health , vol. 11 no. 9, pp. 66-76.

Walkers, S., Sanci, L. & Temple-Smith, M. 2011, ‘Sexting and young people’, Youth Studies Australia , vol. 30 no. 4, pp. 8-16.

Walsh, S. P., White, K. M. & Young, R. M. 2010, ‘Needing to connect: the effect of self and others on young people’s involvement with their mobile phones’, Australian Journal of Psychology , vol. 62 no. 4, pp. 194-203.

ScienceDaily 2008, Weep News: Excessive mobile phone use affects sleep in teens, study finds . Web.

Suss, D. & Waller, G. 2011, Mobile telephone use by young people in Switzerland: The borders between committed use and addictive behavior . Web.

- Should Drivers in Georgia Use Handheld Devices?

- Capabilities of JVC GY-HM250U 4K Cam Handheld Camcorder with 12x Lens

- Organizational Changes: Errors and Ramifications

- Phone Manufacturing Industry

- Negative Influence of Cell Towers

- Personal Digital Assistant Failure

- Effects of the Internet

- Mobile Computing and Its Future Scope

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2019, May 20). Increase in the Use of Mobile Phones and it’s Effects on Young People. https://ivypanda.com/essays/increase-in-the-use-of-mobile-phones-and-its-effects-on-young-people-assessment/

"Increase in the Use of Mobile Phones and it’s Effects on Young People." IvyPanda , 20 May 2019, ivypanda.com/essays/increase-in-the-use-of-mobile-phones-and-its-effects-on-young-people-assessment/.

IvyPanda . (2019) 'Increase in the Use of Mobile Phones and it’s Effects on Young People'. 20 May.

IvyPanda . 2019. "Increase in the Use of Mobile Phones and it’s Effects on Young People." May 20, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/increase-in-the-use-of-mobile-phones-and-its-effects-on-young-people-assessment/.

1. IvyPanda . "Increase in the Use of Mobile Phones and it’s Effects on Young People." May 20, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/increase-in-the-use-of-mobile-phones-and-its-effects-on-young-people-assessment/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Increase in the Use of Mobile Phones and it’s Effects on Young People." May 20, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/increase-in-the-use-of-mobile-phones-and-its-effects-on-young-people-assessment/.

- School Guide

- English Grammar Free Course

- English Grammar Tutorial

- Parts of Speech

- Figure of Speech

- Tenses Chart

- Essay Writing

- Email Writing

- NCERT English Solutions

- English Difference Between

- SSC CGL English Syllabus

- SBI PO English Syllabus

- SBI Clerk English Syllabus

- IBPS PO English Syllabus

- IBPS CLERK English Syllabus

Essay on Disadvantages and Advantages of Mobile Phones

- Advantages and Disadvantages of Java Sockets

- Advantages and Disadvantages of Personal Area Network

- Telecommuting: Meaning, Advantages and Disadvantages

- Advantages and Disadvantages of E-mail

- Advantages and disadvantages of mobile computers

- Advantages and Disadvantages of VoLTE

- Advantages and disadvantages of Optical Disks

- Advantages and Disadvantages of IoT

- Advantages and Disadvantages of Laptops

- Advantages and Disadvantages of WLAN

- Advantages and Disadvantages of LAN, MAN and WAN

- Advantages and Disadvantages of Electronic Wallets

- Advantages and Disadvantages of ARM processor

- Advantages and Disadvantages of Internet

- Advantages and disadvantages of Repeater

- Advantages and Disadvantages of Operating System

- Advantages and Disadvantages of Google Chrome

- Advantages and Disadvantages of Telecommunication

- Advantages and disadvantages of CDMA

Mobile Phones have become an integral part of our day-to-day life. Teaching children to use their phones more thoughtfully can benefit them in both their personal and academic lives and help them become more effective citizens of society.

A mobile phone is a personal communication device that uses a wireless connection to do various functions such as sending and receiving messages, making and receiving calls, and accessing the internet. This article will help the readers to have an overview of the examples of different types of essays on the topic “Advantages and Disadvantages of Mobile Phones”.

Let’s dive right in.

Table of Content

Advantages and Disadvantages of Mobile Phone Essay 100 words

200 words essay on advantages and disadvantages of mobile phone, advantages and disadvantages of mobile phone essay 300 words, advantages of mobile phone, disadvantages of mobile phone, 10 lines essay on advantages and disadvantages of mobile phones.

There are advantages and disadvantages to mobile phones. First, let’s discuss the positive aspects. Our mobile phones facilitate easy communication with friends and family. With our phones, we may use the internet to discover new things as well. With their maps, they make it easy for us to locate our route, and we can even snap photos with them.

However, there are also some drawbacks. Overuse of phones by some individuals can be problematic. It might cause eye pain or even make it difficult to fall asleep. Furthermore, excessive phone use might cause us to lose focus when driving or walking, which is risky.

Thus, we must use our phones responsibly. It’s important to remember to take pauses and not use them excessively. Similar to consuming candy, moderation is key when it comes to this. Utilizing our phones sensibly may make them enjoyable and beneficial. However, we must exercise caution so as not to allow them to cause us issues.

With so many benefits, mobile phones have become an essential part of our life. They facilitate communication and let us stay in touch with loved ones no matter where we are or when we want. Additionally, mobile phones offer instant access to information, which keeps us up to date on global events. They are also useful for navigation, taking pictures to save memories, and even handling our money using mobile banking.

But there are also some disadvantages to these advantages. Overuse of a phone can become addictive, diverting our attention and decreasing our productivity. Extended periods of screen usage can lead to health problems like strained eyes and disturbed sleep cycles. Other drawbacks include privacy issues and the possibility of cyberbullying, which emphasise how crucial it is to use mobile phones properly.

In conclusion, even while mobile phones are incredibly beneficial for communication, information access, and convenience, it is important to consider the possible risks they may pose to one’s health, privacy, and general well-being. Maintaining a balance in the use of mobile phones is crucial to maximise their benefits while minimising their drawbacks.

People also View:

- English Essay Writing Tips, Examples, Format

- Difference Between Article and Essay

Mobile phones also referred to as cell phones, are now an essential component of our everyday existence. As with every technology, they have disadvantages in addition to their many advantages.

- Earning Money: People can investigate flexible job choices by using mobile technology, which offers potential for generating revenue through a variety of channels, including freelance work, online markets, and gig economy applications .

- Navigation: Cell phones with built-in GPS technology make travelling easier by making it simple for users to get directions, explore new areas, and successfully navigate uncharted territory.

- Photography: The inclusion of high-quality cameras in mobile phones has made photography more accessible to a wider audience by encouraging innovation, enabling quick moment capture and sharing, and providing a platform for individual expression.

- Safety: Cell phones help people stay safe because they give them a way to communicate in an emergency, ask for assistance, get in touch with authorities, and keep aware of their surroundings.

- Health Problems: Extended usage of mobile phones is linked to possible long-term health hazards resulting from continuous exposure to radiofrequency radiation, as well as physical health problems such as soreness in the neck and back.

- Cyber Bullying: Cell phones provide people with a platform to harass, threaten, or disseminate damaging information online, which puts the victims’ mental health in serious danger.

- Road Accidents: Cell phone usage while driving increases the risk of distracted driving and traffic accidents, endangering the safety of both pedestrians and drivers.

- Noise & Disturbance: M obile phone use may cause noise pollution in public areas, which can disrupt the peace and discomfort of others. This includes loud phone conversations, notification noises, and other mobile phone-related disruptions.

- Easy Communication: Instantaneous and convenient communication is made possible by cell phones, which also develop real-time connections and bridge geographical distances, improving interpersonal relationships and job productivity.

- Online Education: Since the development of mobile technology, more people have had access to educational materials than ever before, which enables them to pursue online courses, pick up new skills, and engage in lifelong learning at their own speed.

- Social Connectivity: Through the use of various social media platforms, cell phones enable social engagement and networking, keeping individuals in touch with friends, family, and coworkers and promoting a feeling of community and shared experiences.

- Banking & Transactions: The ease with which users may manage their accounts, transfer money, and complete transactions is made possible by mobile banking applications, which lessen the need for in-person bank visits and increase overall financial accessibility.

- Promoting Buisness: Cell phones are effective instruments for marketing, communication, and company promotion. They let companies advertise to a wider audience, interact creatively with clients, and promote their goods and services.

- Entertainment: Mobile phones have completely changed the entertainment sector by giving consumers access to a vast array of games, streaming services, and multimedia material that can be enjoyed while on the go.

- Emergency Assistance: When it comes to emergency circumstances, cell phones are invaluable since they provide prompt access to emergency services, facilitate communication during emergencies, and serve as a lifeline for those in need of rapid aid.

- Addiction & Distraction: Cell phone addiction may result from excessive use, which also makes people easily distracted, reduces productivity, and lessens in-person social contacts.

- Sleeping Disorders: Due to the blue light that cell phones emit, prolonged use of them, especially right before bed, can interfere with sleep cycles, impair the generation of melatonin, and worsen insomnia and other sleeping problems.

- Hearing issues: Long-term exposure to high decibel levels via headphones or phone conversations can cause hearing issues, such as loss or impairment of hearing, and pose a serious risk to the health of the auditory system.

- Vision Problems: Digital eye strain, which can result in symptoms including dry eyes, headaches, and impaired vision, may be exacerbated by excessive cell phone screen usage. This condition may eventually cause long-term visual issues.

- Privacy & Security Risks: Since personal data is vulnerable to hacking, unauthorised access, and abuse, there is a danger to both individuals and organisations while using mobile phones, which has led to worries about privacy breaches and security threats.

- Wastage of Time: Using mobile phones excessively for unproductive purposes, including endlessly browsing social media or playing games, may lead to a major time waster that interferes with both personal and professional obligations.

The below are the 10 lines on advantages and disadvantages of mobile phones in English:

- Mobile phones help us talk to friends and family easily.

- They provide quick access to information through the internet.

- Mobiles make it easy to find our way using maps and GPS.

- We can capture memories with cameras on our phones.

- Banking and managing money is convenient with mobile apps.

- Mobiles offer entertainment with games and videos.

- Using phones too much can be bad for our health.

- It might disturb our sleep and hurt our eyes.

- Too much phone use can be a distraction and affect our work.

- Privacy can be at risk, and there might be issues like cyberbullying.

People Also View:

- Essay on My Favourite Teacher (10 Lines, 100 Words, 200 Words)

- Essay on Women Empowerment

- Essay on Ayodhya Ram Mandir in English for Students

FAQs on Advantages and Disadvantages of Mobile Phones Essay

What are the advantages of using mobile phones.

The advantages of using mobile phones are that they make our lives easier. They help us in easy communication, online education, banking and transactions, safety, emergency assistance etc.

What are the disadvantages of using mobile phones?

Some disadvantages of using mobile phones include addiction & distractions, sleeping disorders, hearing aids, noise & disturbance, wastage of time etc.

Why are mobile phones important?

Mobile phones are very important nowadays because they make an individual’s life more convenient and are the perfect way to stay connected with everyone.

How does using mobile phones affect an individual’s brain?

Research from the US National Institute of Health indicates that using a cell phone damages our brains. According to their findings, our brains utilise more sugar after every fifty minutes of phone usage. This is because sugar is an indicator of increased activity, which is detrimental for the brain.

What are the advantages of phone and disadvantages of phone?

Mobile phones offer communication and provide us the access to enormous information, but at the same time they can be addictive, cause distractions and invade our privacy.

Please Login to comment...

Similar reads.

- Banking English

- SSC English

- School English

- SSC/Banking

Improve your Coding Skills with Practice

What kind of Experience do you want to share?

Home — Essay Samples — Information Science and Technology — Smartphone — Excessive Usage of Smartphones by Junior College Students

Excessive Usage of Smartphones by Junior College Students

- Categories: College Smartphone Student

About this sample

Words: 466 |

Published: Apr 30, 2020

Words: 466 | Page: 1 | 3 min read

Conclusions

- Retrieved from https://login.ezproxy.cnc.bc.ca/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edb&AN=123285015&site=eds-live&scope=site(Naik, A.D 2017 )

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Verified writer

- Expert in: Education Information Science and Technology

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

1 pages / 580 words

3 pages / 1378 words

3 pages / 1281 words

3 pages / 1233 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Smartphone

In recent years, the pervasive use of smartphones among young people has sparked a debate about their potential negative effects on a generation's well-being and development. Some argue that smartphones have had detrimental [...]

As a college student, it is essential to recognize the impact of screen time on adolescents in today's technological world. While it is important to acknowledge the benefits of technology in education and entertainment, it is [...]

Have you ever wondered why your parents hesitated to get you a phone at a young age? What impact do smartphones have on the lives of middle and high school students? In the modern era, technological devices like smartphones play [...]

When it comes to smartphones, two brands that have dominated the market for years are Apple's iPhone and Samsung's Galaxy series. Both companies have loyal followings and offer high-quality devices with cutting-edge technology. [...]

Do you think smoking kills? How about the negative impact of smartphones? Or are we being controlled by technology unknowingly? In the previous decade, technological development boomed in the area of telecommunications, [...]

This paper aims to provide a review of MEMS-Accelerometers different operating principles. At first variety of acceleration sensing and their basic principles as well as a brief overview of their fabrication mechanism will be [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

IELTS Mentor "IELTS Preparation & Sample Answer"

- Skip to content

- Jump to main navigation and login

Nav view search

- IELTS Sample

IELTS Writing Task 2/ Essay Topics with sample answer.

Ielts writing task 2 sample 841 - excessive use of mobile phones and computers badly affects teenagers, ielts writing task 2/ ielts essay:, some people think that excessive use of mobile phones and computers badly affects teenagers' writing and reading skills..

IELTS Materials

- IELTS Bar Graph

- IELTS Line Graph

- IELTS Table Chart

- IELTS Flow Chart

- IELTS Pie Chart

- IELTS Letter Writing

- IELTS Essay

- Academic Reading

Useful Links

- IELTS Secrets

- Band Score Calculator

- Exam Specific Tips

- Useful Websites

- IELTS Preparation Tips

- Academic Reading Tips

- Academic Writing Tips

- GT Writing Tips

- Listening Tips

- Speaking Tips

- IELTS Grammar Review

- IELTS Vocabulary

- IELTS Cue Cards

- IELTS Life Skills

- Letter Types

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Copyright Notice

- HTML Sitemap

Advertisement

Impact of mobile phones and wireless devices use on children and adolescents’ mental health: a systematic review

- Open access

- Published: 16 June 2022

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Braulio M. Girela-Serrano ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3813-2610 1 , 2 na1 ,

- Alexander D. V. Spiers 3 , 4 na1 ,

- Liu Ruotong 1 ,

- Shivani Gangadia 1 ,

- Mireille B. Toledano 3 , 4 , 5 &

- Martina Di Simplicio 1

33k Accesses

17 Citations

9 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Growing use of mobiles phones (MP) and other wireless devices (WD) has raised concerns about their possible effects on children and adolescents’ wellbeing. Understanding whether these technologies affect children and adolescents’ mental health in positive or detrimental ways has become more urgent following further increase in use since the COVID-19 outbreak. To review the empirical evidence on associations between use of MP/WD and mental health in children and adolescents. A systematic review of literature was carried out on Medline, Embase and PsycINFO for studies published prior to July 15th 2019, PROSPERO ID: CRD42019146750. 25 observational studies published between January 1st 2011 and 2019 were reviewed (ten were cohort studies, 15 were cross-sectional). Overall estimated participant mean age and proportion female were 14.6 years and 47%, respectively. Substantial between-study heterogeneity in design and measurement of MP/WD usage and mental health outcomes limited our ability to infer general conclusions. Observed effects differed depending on time and type of MP/WD usage. We found suggestive but limited evidence that greater use of MP/WD may be associated with poorer mental health in children and adolescents. Risk of bias was rated as ‘high’ for 16 studies, ‘moderate’ for five studies and ‘low’ for four studies. More high-quality longitudinal studies and mechanistic research are needed to clarify the role of sleep and of type of MP/WD use (e.g. social media) on mental health trajectories in children and adolescents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Prevalence of problematic smartphone usage and associated mental health outcomes amongst children and young people: a systematic review, meta-analysis and GRADE of the evidence

Exposure to and use of mobile devices in children aged 1–60 months

The associations between screen time and mental health in adolescents: a systematic review.

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Over the last ten years, the communication and information landscape has changed drastically with the development and rapid uptake of new portable devices such as smartphones or tablets, which are able to provide instant access to the internet anywhere. The likelihood of owning a smartphone increases with age, with market research reporting 83% of children in the UK aged 12–15 own a smartphone and 59% own a tablet. Up to 64% of children aged 12–15 have three or more devices of their own [ 1 ]. Alongside increased ownership rates, multifunctionality has expanded; a child’s phone may now enable internet browsing, games, applications, learning, online communication, and social networking.

The growing use of these technologies has raised concerns about how exposure patterns may affect children and adolescents’ wellbeing, as mental health disorders constitute one of the dominant health problems of this age group [ 2 ]. Increases in digital device usage have been hypothesized to be responsible for the secular trend of increasing internalizing symptoms, poorer wellbeing, and suicidal behaviours in adolescent populations [ 3 ]. It is reported that between 10–20% of children and adolescents suffer from a mental health problem globally [ 4 , 5 ] and up to 50% of mental disorders emerge under the age of 15 [ 6 ]. A recent meta-analysis estimates the prevalence of any depressive disorder in children and adolescents is 2.6% (95% CI 1.7–3.9), and of any anxiety disorder is 6.5% (95% CI 4.7–9.1) [ 7 ]. Recent studies have shown that the usage of mobile devices in children and adolescents may be associated with depression [ 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 ], anxiety [ 8 , 10 , 15 , 16 ] and with behavioural problems [ 17 ]. Particular patterns of smartphone-related behaviour, termed as ‘problematic smartphone use’ may be responsible for poor mental health associations [ 18 ].

Initially, research focussed on the physiological aspects of exposure to mobile phones or wireless devices (MP/WD) that use radiofrequency electromagnetic fields (RF-EMF). The Stewart Report identified that children and adolescents may be especially susceptible to exposure due to their developing nervous systems, greater average RF deposition in the brain compared with adults, and a longer lifetime of exposure [ 19 ]. It is still unclear whether exposure to RF-EMF from MP/WD can affect cognitive and emotional development in children and adolescents [ 20 ].

However, health effects of MP/WD on children and adolescents could also stem from psychological, social and behavioural factors related to their use. Adolescence is a dynamic phase of social and emotional development characterised by a change in the intensity and quality of communications among peers [ 21 ]. Adolescents have a constant need to interact and to be acknowledged by others, so that they can define their role and status in the peer group [ 22 ]. This distinctive pattern of socialization contributes to and is reflected by the pervasive use of social media embedded in MP/WD at this stage of life and research so far has focussed on this aspect.

Physiologically, adolescence is characterized by a delay in bedtime and a decrease in length of sleep with age [ 23 ], and sleep deficits are highly prevalent [ 24 ]. Given the pivotal role of sleep in adolescents’ health and development, research has investigated the associations between bedtime use of MP/WD, sleep disturbance and poor mental health outcomes. Studies to date report growing evidence of the detrimental impact of these technologies on sleep, although the specific relationship with mental health remains to be fully understood [ 25 ], including potential mechanisms such as (1) displacement of sleep by directly interrupting sleep time [ 26 ], (2) impact on circadian rhythm due to exposure to blue and bright light from screens [ 27 ] and (3) sleep disturbance due to the content of messages received pre-bedtime [ 28 ].

The complex relationship between factors including (but not limited to) exposure to RF-EMF, light from screens, engagement with internet or social media content, peer communication and their physiological and psychological consequences represents a challenge to determining definitive associations of interest between children and adolescents’ MP/WD use and mental health. This research field has evolved through different theoretical approaches and become the centre of media interest. However, previous reviews have either focussed on the psychological or behavioural aspects [ 29 ], or specifically on RF-EMF exposures for MP only [ 30 , 31 ], and overlooked key information on confounders, such as socio-demographic factors. It is important when synthesizing these findings that all aspects of MP/WD use are considered. For example, mobile phone use is related to exposures hypothesized to have psychological effects (e.g., RF-EMF, screen-light), but these often occur simultaneously with changes of behaviour (e.g., reduced sleep, physical activity). Furthermore, different purposes of use may have different levels and temporal patterns of usage. Disentangling these effects often requires complex, tailored study-designs with advanced exposure measurement tools, and discussion of these issues with respect to MP/WD use and mental health is often missing. An assessment of the methodological quality of the available evidence to date could direct future research, policy and health recommendations around children and adolescents’ use of MP/WD. This evidence synthesis is also much needed now that digital tools for mental health hold the promise to overcome barriers to access support [ 32 ]. As the current COVID-19 pandemic has further accelerated the move towards a “digital mental health revolution”, it is crucial to identify if and under which conditions MP/WD use may be detrimental.

Our aims are to undertake a systematic review and appraisal of the evidence with a primary objective of assessing the relationship between duration or frequency of MP/WD use and children and adolescents’ mental health through synthesis of findings from individual quantitative observational studies conducting inferential analysis on this relationship. We define our exposure as any mobile or portable technologies that use RF-EMF to connect with the internet, cellular network, or cordless base station. This includes mobile phones, tablets and smartphones. Studies investigating only the use of devices that are not wireless (e.g. TV) or handheld in the same manner as tablets and phones (e.g. laptops) were excluded.

Secondary objectives are to synthesise findings on whether:

Impact on mental health is influenced by the temporal pattern (e.g. bedtime)

Different modes of use (e.g. calls, social media, instant messaging) have distinct effects on mental health

Impact on mental health differs for specific outcomes, in particular: internalizing symptoms (e.g. anxiety, depression, suicidal ideation/self-harm), externalizing symptoms (e.g. attention, concentration) and general wellbeing.

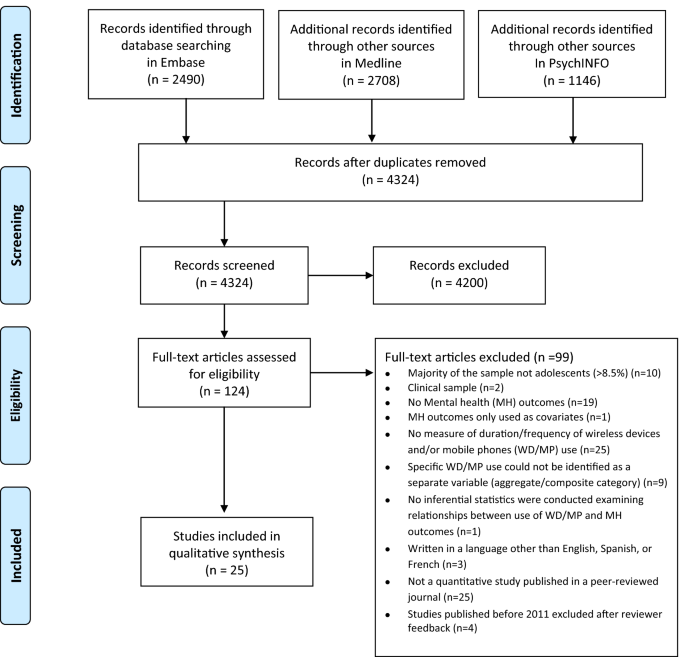

Search strategy and selection criteria

This review was written in accordance with PRISMA statement recommendations (see Supplementary Material Table S1 for PRISMA checklist) [ 33 ] and was prospectively registered on PROSPERO (CRD42019146750) [ 34 ]. Relevant published articles were identified using tailored electronic searches developed with experts on MP/WD exposure and mental health (see Supplementary Material Table S2 for search terms list where we outline examples of exposures and mental health outcomes in detail). We originally searched Medline, Embase and PsycINFO using OVID interface for all studies published prior to July 15th 2019 (see PRISMA Flowchart Fig. 1 ). Both published and unpublished studies with abstracts and full texts in English, Spanish and French were searched. BGS and AS completed backward and forward citation tracking of included studies. Any inconsistencies between selected studies were resolved by discussing this with a third author (MDS).

PRISMA Flowchart

Each study identified in the search was evaluated against the following predetermined criteria:

Population: Studies examining children or adolescent populations where at least 70% of participants are aged 18 years or under.

Exposure: Studies measuring daily or weekly duration or frequency of mobile phone or wireless device use (devices can include smartphones, cordless phones, tablets e.g., iPad).

Outcomes: Studies that report a standardized and/or quantifiable measure (i.e., administered in a consistent manner across subjects) of mental health symptoms or psychopathology prevalence, which we define as to include: measures of internalizing symptoms and disorders (e.g. anxiety, depression, suicidal ideation/self-harm), externalizing symptoms and disorders (e.g. attention, and conduct disorders), and well-being measures (e.g. measures of self-esteem, health-related quality of life) among children and adolescents.

Published in a peer-reviewed journal in English, Spanish or French.

Reported inferential statistics describing cross-sectional or longitudinal associations between MP/WD usage and mental health outcomes.

Studies were excluded if: (1) specific wireless device use could not be identified as a separate variable (i.e., the main independent variable in the statistical model is a composite such as “digital media use”, “screen time”); (2) only clinical populations; (3) only investigated: physical health (e.g.: headaches, fingers/neck pain), somatic symptoms, cognitive functions (attention, memory), safety (driving, related accidents), relational consequences (relationships, physical fitness, worse academic performance, sexual behaviour (sexting), cyberbullying, sleep habits, personality, study assessment or intervention of substance use/addiction, specific apps, smartphone and social media loss, reviews or qualitative studies. (4) Case studies, opinion pieces, editorials, comments, news, letters and not available in full text. After reviewer feedback, we excluded all articles published before January 1st 2011 as MP/WD devices used before this period are unlikely have the same interactivity of devices used at the time of search.

Data extraction and quality assessments

We (BGS, AS, ER, SG) extracted the data using a standard data extraction form (data extraction started on Aug 20, 2019). Data was verified by a second author, and then checked for statistical accuracy (AS or BGS). We chose to extract the estimands of associations from the final covariate-adjusted model specified by each group of study author, as not every iteration of the models was available to us. For transparency, the adjustment factors can be viewed clearly in the column second to the right of Tables 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 .

Authors of original papers were contacted to provide missing (subsample) data where necessary. AS and BGS both appraised each study independently for methodological quality and risk of bias using checklists adapted from the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS), originally designed to evaluate cohort studies [ 35 ], and considered a useful tool to assess risk of bias [ 36 ]. We used a customized checklist for cross-sectional studies, following an approach taken by previous systematic reviews of observational research [ 37 , 38 ]. We also used the STROBE individual component checklist to critically appraise the aspects of reporting related to risk of bias, e.g. study design or sampling methods [ 39 ]. We defined the most important covariate adjustment factors as previous diagnosis of mental disorder or prior mental health and demographic confounders (sex, age, socioeconomic status (SES)) based on the Newcastle–Ottawa quality assessment Scale (NOS). We then categorized studies by quality and risk of bias based on accepted thresholds for converting the Newcastle–Ottawa scales to AHRQ standards [ 40 ]. A description of the conversion rules can be found in the footnotes to Table S6 and S7 in the Supplementary Material.

Data synthesis

Given the high heterogeneity of the retrieved studies with regards to the primary explanatory variable of interest (MP and WD usage), the outcomes of interest (mental health), the objectives and the statistics used, statistical pooling was considered to be inappropriate and the quantitative data is synthesised narratively.

We classified studies by MP/WD exposure: (a) general MP/WD use (frequency/duration) and (b) bedtime MP/WD use; and by mental health outcomes: internalising symptoms, externalising symptoms and wellbeing. Children and adolescents’ emotional, behavioural and social difficulties are widely conceptualised in internalizing and externalizing symptoms groupings [ 41 ], endorsed by the DSM-V to provide directions in clinical and research settings [ 42 ]. We added a third category of wellbeing, to group scales measuring resilience, self-esteem, self-efficacy, optimism, life satisfaction, hopefulness etc., which are important indicators of how mental health is subjectively perceived and often valued by individuals above clinical symptoms [ 43 , 44 ].

All retrieved studies meeting eligibility criteria ( N = 25) were observational and investigated both genders. Ten (40%) employed a longitudinal design, while the remaining 15 (60%) had a cross-sectional design. One study [ 45 ] reported both cross-sectional and longitudinal findings. There were multiple studies drawing from the same population: three from the HERMES cohort [ 46 , 47 , 48 ], two from the LIFE cohort [ 49 , 50 ] and two from the same sample of high-school students [ 11 , 12 ].

The total number of research subjects was 164,284 who were aged between five and 21 years old. Most studies examined typically developing adolescents aged 8–18 years old. Three studies looked at young children aged 2–7 years old [ 50 , 51 , 52 ]. One study that included young people aged up to 21 years old was included in the review as ~ 70% of the samples met the ≤ 18-years old criteria [ 8 ].

Studies investigating associations of mental health outcomes with only aggregated screen time without device-specific measures were excluded from the review. All studies measured MP use. Three studies also investigated the effect of cordless phone usage [ 14 , 17 , 48 , 52 , 53 ]. Two studies also included specific measures of tablets [ 51 , 54 ]; one study investigated other categories of WD including: eBook reader, laptop, portable media player and portable video game console [ 54 ]. Most studies used self-report questionnaires to assess MP/WD use: for example, asking participants to rate their daily or weekly use to best match an interval provided by the questionnaire [ 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 15 , 16 , 46 , 48 , 53 , 55 , 56 ], or with ordinal scales of frequency [ 14 , 28 , 47 , 57 , 58 ]. Studies with young children instead used parent questionnaires [ 50 , 51 , 52 ]. Twenty studies reported MP/WD general use and five with bedtime use. Seven studies collected data of MP/WD usage on weekends and weekdays separately [ 9 , 10 , 45 , 46 , 55 , 56 , 59 ], with five of these reporting associations with mental health separately for weekday and weekends [ 9 , 10 , 55 , 56 , 59 ]. Twenty studies reported internalizing symptoms, 11 externalizing symptoms, and ten well-being measures.

Details on study aim, sample characteristics, MP/WD use, mental health outcomes and measures, and findings are summarised in Tables 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 .

Quality assessment

The median and mean NOS scores of the longitudinal studies were 6 and 6.3 respectively. The median and mean scores for cross-sectional studies were 5 and 5.0 respectively. We converted each NOS Score for the 25 studies to AHRQ standards: risk of bias was rated as “high” for 16 studies, “moderate” for 5 studies and “low” for 4 studies. Risk of information bias was common as self-report measures were prevalent for outcome and exposure assessment. Additional factors contributing to high risk of bias included: risk of selection bias, attrition, and the absence of adjustment for confounding factors. All details regarding quality assessment, including summaries of risk of bias across studies, are reported in the Supplementary Material (Tables S4-S8).

Main Research Findings

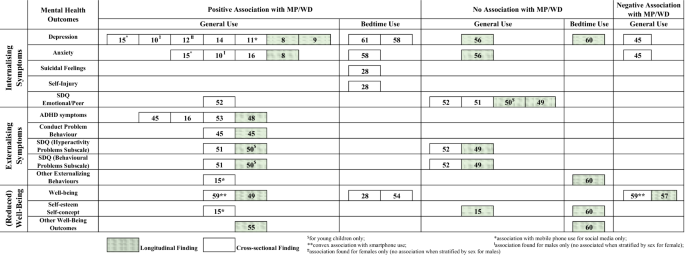

Findings are presented by exposure time (general or bedtime), design (longitudinal or cross-sectional) and outcome assessed (internalising symptoms, externalising symptoms and wellbeing). For each group of longitudinal findings, we report the AHRQ Quality Band (“high”, “moderate” or “low” below refer to risk of bias). Figure 2 categorises effects reported by direction of association with mental health outcome and by whether bedtime or daily aggregate MP/WD usage was investigated. All cross-sectional studies were rated as high risk of bias, so for brevity these are not reported in the text below. Unless otherwise stated, we describe associations adjusted for all confounding variables reported in each study (see Tables 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 for details of covariates included in adjusted models).

Harvest plot of associations between MP/WD usage and mental health outcomes among children and adolescents included in the systematic review. Numbers refer to study references as cited in the reference list. Two studies [ 46 , 47 ] were excluded from this plot as they did not report direct inferential statistics between MP/WD and mental health

General use of wireless devices

Longitudinal findings.

Nine out of the 10 longitudinal studies included in this review examined associations between mental health outcomes and general use of MP/WD (Table 1 ).

Internalising symptoms : Two out of five studies (one low risk, one high) found a significant association between general use of MP/WD and measures of internalising symptoms. Bickham et al. [ 9 ] found that more frequent MP use recorded via a diary at baseline predicted higher depression scores on the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) at one-year follow-up. Similarly, Liu et al. [ 8 ] found that baseline high MP use was associated with higher incidence of depressive and anxiety symptoms measured with the BDI and the Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS) after eight months. However, two studies (both moderate risk) from the LIFE cohort did not find any association between baseline general MP use and internalising symptoms recorded via the Strengths & Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ)—parent-reported [ 50 ] and self-reported [ 49 ] at one-year follow-up. This finding is consistent with the largest longitudinal study reviewed (low risk), a cohort study that found no association between baseline texting duration and depression or anxiety measured with the self-report versions of the Clinical Interview Schedule (CIS-R) in adolescents after two years [ 56 ].

Externalising symptoms : Three out of four studies (one low risk and two moderate risk) found a significant association between general use of MP/WD and measures of externalising symptoms. The first LIFE cohort study found that more frequent baseline parent-reported MP use predicted a higher score in the parent-reported hyperactivity/inattention and conduct problems SDQ subscales of young children after one year [ 50 ]. This evidence was consistent with the findings from two other studies: one found increase in conduct disorders after 18 months measured by ecological momentary assessment (EMA) [ 45 ] and the other found increase in concentration difficulties after one year measured by a four-point single-item Likert scale [ 48 ] in adolescents’ populations, both associated with more frequent self-reported texting [ 45 , 48 ] and duration of MP calls [ 48 ]. The latter study also measured cumulative RF-EMF dose from MP/WD and far-field environmental sources and found that whole-body RF-EMF dose was associated with concentration difficulties when calculated from self-reported duration of use (duration of data traffic, cordless phones), but not when calculated from objective measures (network operator-measured data volume and call duration) [ 48 ]. The second LIFE cohort study found no significant association with baseline MP/WD usage and self-reported SDQ in adolescents at one-year follow-up [ 49 ].

Wellbeing : Two out of three studies (both moderate risk) found a significant association between general use of MP/WD and measures of wellbeing. Use of MP/WD over a school year was negatively associated with positive self-concept but not with general wellbeing in adolescents [ 55 ]. Conversely, Poulain et al. [ 49 ] found that adolescents with higher MP use at baseline reported a decrease in wellbeing measured with the health-related quality of life (HRQoL) scale by KIDSCREEN-27 at one-year follow-up. Another study (moderate risk) found that baseline duration of MP use for social communication had a positive indirect effect on children’s wellbeing measured with a bespoke scale at one and two-year follow-up, mediated through changes in social capital [ 57 ].

Cross-sectional findings

Twelve out of the 16 studies reporting cross-sectional findings included in this review examined associations between mental health outcomes and general use of MP/WD (Table 3 ). Two studies measured general use of MP and mental health, as well as problematic use of MP via specific questionnaires [ 46 , 47 ], but as they did not report direct associations between duration or frequency of MP/WD use and mental health, we do not report their findings in this section.

Internalising symptoms : Six out of nine studies found significant cross-sectional positive associations between general use of MP/WD and measures of internalising symptoms [ 10 , 11 , 13 , 15 , 16 , 52 ]. Most samples were adolescents and symptom measures varied from a single-item self-report to validated questionnaires. Overall, higher MP/WD use was associated with more anxiety or depressive symptoms, although in some studies this was limited to activities such as social networking and online chatting [ 11 , 15 ] or in females only [ 12 ]. One study reported an association in the opposite direction, reporting that adolescents experienced less anxiety and depressive symptoms measured with the Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC) and BDI on days when sending more text messages [ 45 ]. Two studies did not find any significant association [ 51 , 52 ].

One study also investigated the direct effect of RF-EMF on internalising symptoms [ 14 ], which showed that adolescents that used cordless phones had a higher likelihood of depressive symptoms compared to those who did not, but only true for cordless phones with frequencies ≤ 900 MHz [ 14 ].

Externalising symptoms : Three out of five cross-sectional studies found a significant positive association between general MP/WD use and measures of externalising symptoms (Table 3 ).

In particular, greater MP/WD use was related to concentration problems [ 16 , 53 ], attention problems [ 16 ], hyperactivity symptoms [ 51 ], conduct problems [ 51 ], and hostility [ 15 ]. In contrast, no association was found with externalising symptoms reported by parents or teachers in young children [ 52 ].

Wellbeing : Two cross-sectional studies reported cross-sectional associations between general MP use and measures of wellbeing. One study found that adolescents who used MP for social media had significantly lower self-esteem [ 15 ]. Using more sophisticated modelling in a large sample of adolescents, Przybylski & Weinstein [ 59 ] described an inverted-U-shape relationship between digital-screen time and mental wellbeing, such that moderate engagement with MP is not harmful and may be advantageous, and effects may differ on weekdays compared to weekends.

Bedtime use of wireless devices

Only one (low risk) out of 10 longitudinal studies included in this review examined associations between mental health outcomes and bedtime MP use, measured both at baseline and at three-year follow-up [ 60 ] (Table 4 ).

Internalising symptoms : Increased bedtime MP use from baseline to follow-up was not associated with changes in depressed mood measured with a bespoke 5-item scale, after adjusting for sleep behaviour [ 60 ].

Externalising symptoms : Increased bedtime MP use from baseline to follow-up was not associated with changes in externalizing behaviour measured with a bespoke 7-item scale, after adjusting for sleep behaviour [ 60 ].

Wellbeing : Increased bedtime MP use from baseline to follow-up was not associated with changes in coping abilities and self-esteem measured with bespoke 1 item and 3-item scales, after adjusting for sleep behaviour [ 60 ].

Four out of the 19 cross-sectional studies included in this review examined associations between mental health outcomes and bedtime MP/WD use (Table 2 ).

Internalising symptoms : All three studies investigating associations between bedtime MP use and measures of internalising symptoms found significant positive associations. In particular, more frequent and longer bedtime use was associated with higher depressive [ 58 , 61 ], anxiety symptoms [ 58 ], suicidal feelings and self-injury [ 28 ]. However, in two studies this was partially mediated through reduced sleep duration [ 58 ] and sleep difficulties [ 61 ].

Externalising symptoms : No retrieved cross-sectional study investigated the associations between bedtime MP use and measures of externalising symptoms.

Wellbeing : One cross-sectional study described that adolescents who used MP at bedtime scored less on the HRQoL scale by KIDSCREEN-52 compared to those who did not, particularly when using screen mobile devices in a dark room [ 54 ].

This systematic review evaluated the current evidence on associations between MP/WD use and mental health outcomes in children and adolescents across 25 studies published up to 2019. With regards to our objectives, firstly, we found evidence to suggest that greater use of MP/WD may be associated with poorer mental health in children and adolescents, but that the strength of the associations vary partly depending on the time and nature of MP/WD usage. Secondly, we found evidence that bedtime MP/WD duration or frequency of use in particular is associated with worse mental health. Third, based on limited available research we found no evidence supporting a direct impact of RF-EMF on mental health. Finally, more studies are needed to clarify whether the different uses of MP/WD have distinct impacts on specific psychopathology. In particular, we found that the general use of MP/WD might be associated with externalising symptoms in children and adolescents.

We found substantial between-study heterogeneity in the choice of exposures and mental health outcomes, methods of exposure assessment, scales used to assess outcomes, study design, population selection, and approaches taken to address confounding variables—limiting our ability to infer general conclusions. This combined with the fact that a large proportion of studies (16 out of 25) were rated as high risk of bias, may explain the considerable between-study discrepancies on the presence/direction of associations found. Limitations to exposure assessment (as discussed below) imply that some associations could have been missed, while lack of correction for known confounding variables and differential recall bias in studies with cross-sectional design may have inflated the magnitude of associations [ 62 ]. Our synthesis is predominantly based on cross-sectional data, with few longitudinal studies to date producing inconsistent results.

The results of the current review largely align with recent systematic reviews on aggregated electronic screen time in children and young people, which have concluded that there are positive small but significant correlations between screen time and young children’s internalizing and externalizing behaviours [ 63 , 64 ], and that longitudinal associations between screen time and depressive symptoms varied between different devices and uses [ 64 ].

MP/WD usage

The strength and direction of associations between MP/WD use and mental health outcomes appear to depend on exposure-related factors including: the type of device, the purpose and the time-pattern of use, and the method of exposure assessment. For example, significant associations between MP use and symptoms of depression are reported for general MP use, but not when only measuring texting longitudinally [ 56 ] and fewer symptoms were reported on days when adolescents sent more texts in a cross-sectional study [ 45 ]. Similarly, no association with mental health outcomes emerged from specifically examining the effect of phone call duration or frequency in adolescents [ 14 , 15 , 48 ], unless calls occurred at night-time [ 58 , 60 ]. Six studies specifically reported to be measuring smartphone use [ 11 , 12 , 15 , 51 , 57 , 59 ]. Almost all other studies reported aggregated measures from devices capable of internet use with those that are not capable, making disentangling smartphone-specific effects impossible.

Overall, our observations are consistent with previous literature on differential effects depending on modes of technology use. For example, interactive screen time such as the use of a computer has been found to be more detrimental to sleep than passive screen time such as television watching [ 24 , 65 ]. Historically, aggregated “screen time” was believed to impact health via displacing activity away from more adaptive behaviours [ 66 ], but this fails to capture the current diverse scopes of MP/WD use, from information seeking, to social interaction and entertainment [ 67 ]. Future studies should clarify how different modes of MP/WD use may have distinct psychological consequences, some of which are likely to foster resilience as well as increase vulnerability to mental health disorders.

An emerging area of the literature that holds promise explaining how the use of mobile phone use may explain variation in mental health in young people involves defining problematic mobile phone use or problematic smartphone use (PSU). This domain of behaviours has been conceptualised in a way that corresponds to the constructs of behavioural addiction. Previous studies have defined PSU through self-report scales with items with diagnostic criteria that resemble the criteria for substance use disorders (SUD), specifically symptoms of dependence such as loss of control (trouble limiting one’s smartphone use), tolerance (progressive increase in smartphone use to achieve the same psychological rewards) and withdrawal (negative symptoms on withdrawal) [ 68 ]. This approach has already shown that PSU is associated with poorer wellbeing and mental illness: a recent meta-analysis investigating psychological and behavioural dysfunctions related to smartphone use in young people has shown that PSU was associated with an increased odds of depression, anxiety, and stress; however, most research subjects within the pooled sample for depression and anxiety were over the age of 18 [ 18 ]. Furthermore, in common with other related constructs of problematic technology use associated with dysfunction (such as internet addiction and internet gaming addiction [ 69 , 70 ]), some commentators have raised concerns that diagnosing individuals with PSU who display behavioural addictive symptoms with borrowed items from the diagnostic criteria of substance addiction disorders may not improve understanding of problematic use of technology’s aetiology and psychological sequelae [ 71 , 72 ]. Nonetheless, although out the scope of this review, investigating MP/WD usage through the paradigm of PSU and addiction research with younger children, who are not yet as studied as college students, could potentially inform this field.

A major limitation in most studies was the choice of self-report measures to assess MP/WD exposure without external validation. Self-report device use is subject to measurement error such as recall difficulty and bias (e.g. call duration is considerably overestimated in adolescents populations [ 73 , 74 ]). However, as children and adolescents favour online activity over calls and use wi-fi, data from self-report questionnaires may be more reliable indicators than activity inferred from operator-reported data [ 75 ]. Some self-report methods may be more robust, for example EMA may eliminate recall bias compared to self-report questionnaires or diaries [ 9 ], but participants may selectively respond to certain EMA signals [ 76 ]. Combining different methods of assessment has so far highlighted incongruencies [ 47 , 48 ] and suggests a need for refining methodological rigour in measuring exposure. Future study-designs should confront these potential sources of bias by cross-validating different self-report instruments combined with device-recorded assessments of MP/WD use. Understanding measurement of MP/WD use and how likely exposure misclassification occurs is of critical importance. Some researchers have used duration of usage as a proxy for whether smartphone usage is problematic, i.e., is excessive and includes behaviours linked to addiction and impaired control. There is no established cut-off beyond which usage is defined as problematic, nor is usage alone sufficient for this classification without subjective distress [ 77 ]. Measures of problematic use can capture constructs that are distinct from measures of daily usage and duration, yet only with improving tracking and logging media use can the relationship between the two be understood [ 78 ].

Assessment of mental health

Assessment of outcomes also included a wide range of different instruments, hindering direct comparison and limiting conclusive generalisable data synthesis. Mental health outcomes were investigated with a variety of self-report measures including ad hoc items [ 13 , 16 , 28 , 53 , 57 ], scales [ 8 , 12 , 17 , 47 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 56 , 59 ], sections of scales [ 9 , 10 , 14 , 15 , 45 , 60 , 61 ] and the same scale was even used with different cut-off levels [ 11 , 12 , 17 , 46 , 47 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 54 , 55 ].