ANA Nursing Resources Hub

Search Resources Hub

What Is Nursing Theory?

3 min read • July, 05 2023

Nursing theories provide a foundation for clinical decision-making. These theoretical models in nursing shape nursing research and create conceptual blueprints, ultimately determining the how and why that drive nurse-patient interactions.

Nurse researchers and scholars naturally develop these theories with the input and influence of other professionals in the field.

Why Is Nursing Theory Important?

Nursing theory concepts are essential to the present and future of the profession. The first nursing theory — Florence Nightingale's Environmental Theory — dates back to the 19th century. Nightingale identified a clear link between a patient's environment (such as clean water, sunlight, and fresh air) and their ability to recover. Her discoveries remain relevant for today's practitioners. As health care continues to develop, new types of nursing theories may evolve to reflect new medicines and technologies.

Education and training showcase the importance of nursing theory. Nurse researchers and scholars share established ideas to ensure industry-wide best practices and patient outcomes, and nurse educators shape their curricula based on this research. When nurses learn these theories, they gain the data to explain the reasoning behind their clinical decision-making. Nurses position themselves to provide the best care by familiarizing themselves with time-tested theories. Recognizing their place in the history of nursing provides a validating sense of belonging within the greater health care system. That helps patients and other health care providers better understand and appreciate nurses’ contributions.

Types of Nursing Theories

Nursing theories fall under three tiers: grand nursing, middle-range, and practical-level theories . Inherent to each is the nursing metaparadigm , which focuses on four components:

- The person (sometimes referred to as the patient or client)

- Their environment (physical and emotional)

- Their health while receiving treatment

- The nurse's approach and attributes

Each of these four elements factors into a specific nursing theory.

Grand Nursing Theories

Grand theories are the broadest of the three theory classifications. They offer wide-ranging perspectives focused on abstract concepts, often stemming from a nurse theorist’s lived experiences or nursing philosophies. Grand nursing theories help to guide research in the field, with studies aiming to explore proposed ideas further.

Hildegard Peplau's Theory of Interpersonal Relations is an excellent example of a grand nursing theory. The theory suggests that for a nurse-patient relationship to be successful, it must go through three phases: orientation, working, and termination. This grand theory is broad in scope and widely applicable to different environments.

Middle-Range Nursing Theories

As the name suggests, middle-range theories lie somewhere between the sweeping scope of grand nursing and a minute focus on practice-level theories. These theories are often phenomena-driven, attempting to explain or predict certain trends in clinical practice. They’re also testable or verifiable through research.

Nurse researchers have applied the concept of Dorothea E. Orem's Self-Care Deficit Theory to patients dealing with various conditions, ranging from hepatitis to diabetes. This grand theory suggests that patients recover most effectively if they actively and autonomously perform self-care.

Practice-Level Nursing Theories

Practice-level theories are more specific to a patient’s needs or goals. These theories guide the treatment of health conditions and situations requiring nursing intervention. Because they’re so specific, these types of nursing theories directly impact daily practices more than other theory classifications. From patient education to practicing active compassion, bedside nurses use these theories in their everyday responsibilities.

Nursing Theory in Practice

Theory and practice inform each other. Nursing theories determine research that shapes policies and procedures. Nurses constantly apply theories to patient interactions, consciously or due to training. For example, a nurse who aims to provide culturally competent care — through a commitment to ongoing education and open-mindedness — puts Madeleine Leininger's Transcultural Nursing Theory into effect. Because nursing is multifaceted, nurses can draw from multiple theories to ensure the best course of action for a patient.

Applying theory in nursing practice develops nursing knowledge and supports evidence-based practice. A nursing theoretical framework is essential to understand decision-making processes and to promote quality patient care.

Images sourced from Getty Images

Related Resources

Item(s) added to cart

- Subscribe to journal Subscribe

- Get new issue alerts Get alerts

Secondary Logo

Journal logo.

Colleague's E-mail is Invalid

Your message has been successfully sent to your colleague.

Save my selection

Case Studies in Nursing Theory

Winstead-Fry, Patricia

Full Text Access for Subscribers:

Individual subscribers.

Institutional Users

Not a subscriber.

You can read the full text of this article if you:

- + Favorites

- View in Gallery

Readers Of this Article Also Read

Medication update, trees as a social determinant of health, th</sup> annual aprn legislative update: trends in aprn practice authority during the covid-19 global pandemic', 'phillips susanne j. dnp aprn fnp-bc faanp faan', 'the nurse practitioner', 'january 2022', '47', '1' , 'p 21-47');" onmouseout="javascript:tooltip_mouseout()" class="ejp-uc__article-title-link">34 th annual aprn legislative update: trends in aprn practice authority during..., pain management for patients with chronic kidney disease in the primary care..., legislative update 2009: despite legal issues, apns are still standing strong.

- UR Research

- Citation Management

- NIH Public Access

More information on Research

- Apps and Mobile Resources

- Med Students Phase 1

- School of Nursing

- Faculty Resources

More information on Guides and Tutorials

- iPad Information and Support

More information on Computing and iPads

- Library Hours

- Make A Gift

- A-Z Site Index

More information on us

- Miner Library Classrooms

- Multimedia Tools and Support

- Meet with a Librarian

More information on Teaching and Learning

- History of Medicine

More information on Historical Services

- Order Articles and Books

- Find Articles

- Access Resources from Off Campus

- Get Info for my Patient

- Contact my Librarian

More information on our services

- Research and Publishing

- Guides and Tutorials

- Computing and iPads

- Teaching and Learning

- How Do I..?

School of Nursing: Nursing Theory

- Core Clinical eBooks

- Nursing Books

- Visible Body Suite: Anatomy App

- Search Basics

- Video Tutorials

- Middle Range Theories

- Specific Nursing Theory Books

- Nursing Theory Articles

- What to Search

- Citation Managers

- Library Space

- Printing, Photocopying, and Scanning

- ClinicalKey for Nursing

- Create a MyNCBI Account

Introduction

Here you will find books, both eBooks and Print books, that are collections of nursing theories/mid range theories/social theories. These books are designed to inform the user about the theorist and their theories. These books are not primary or original sources for nursing theories.

Print Books

- << Previous: Key Tools

- Next: Middle Range Theories >>

- Last Updated: Jun 21, 2024 9:16 AM

- URL: https://libguides.urmc.rochester.edu/son

Nurse Theorists

- Patricia Benner

- Virginia Henderson

- Dorothy Johnson

- Imogene King

- Madeleine Leininger

- Myra Levine

- Betty Neuman

- Margaret Newman

- Florence Nightingale

- Dorothea Orem

- Ida Jean Orlando Pelletier

- Rosemarie Rizzo Parse

- Nola Pender

- Hildegard Peplau

- Martha Rogers

- Callista Roy

- Joyce Travelbee

- Jean Watson

- General Nursing Theory

Additional Resources

Contact the library.

Ask a Librarian

Document Delivery: All Mayo staff with LAN IDs and passwords can use Document Delivery to receive copies of journal articles and book chapters.

Newer Books

- << Previous: Jean Watson

- Last Updated: Oct 26, 2023 10:55 AM

- URL: https://libraryguides.mayo.edu/nursetheorists

NUR 3805: Nursing Theory and Theorists - Tucker, Tinley

- Researching Nursing Theorists

- Finding Biographical Information

- eBooks on Theories and Theorists This link opens in a new window

- Peer-Reviewed Articles

Case Studies

Find scholarly research & clinical cases using nursing theorist or theory.

TIPS:

- Search using the nursing theorist's nam e, but also do separate searches using the name of their theory. Putting words in quotes often allows them to be searched as a phrase.

- Using the AND function of the Boolean Search in CINAHL can yield more accurate results.

- Try the Advanced Search feature on the library website if you are not finding good information in specific databases

- CINAHL Complete (EBSCO) This link opens in a new window Scholarly Nursing journal articles. Select for evidence based practice and other specific search limiters to improve search results. BSC, NUR, HSA

- Ovid Nursing Journals This link opens in a new window Selection of over 40 scholarly nursing journals. Includes a wide range of subject areas, evidence based practrice, clinical trials and more.

- Health & Medicine (Gale) This link opens in a new window Search full text Nursing and Allied Health journals. Research case studies, viewpoints, product/service evaluations and scholarly articles.

- Health & Nursing (EBSCO) This link opens in a new window Three databases in one. Contains the American Psychological Association's PsycArticles, the professional nursing database CINAHL, and MEDLINE.

- << Previous: eBooks on Theories and Theorists

- Next: APA >>

- Last Updated: Jun 29, 2023 4:26 PM

- URL: https://libguides.scf.edu/nursing_theory_theorists

- OJIN Homepage

- Table of Contents

- Volume 21 - 2016

- Number 2: May 2016

- Integrating Lewin’s Theory with Lean’s System Approach

A Case Review: Integrating Lewin’s Theory with Lean’s System Approach for Change

Elizabeth Wojciechowski is a doctorally prepared APN in mental health nursing with 25 years of experience in clinical management, strategic planning, graduate-level education, and qualitative and quantitative research. Her most recent professional experience as Education Program Manager and Project Consultant includes collaborating with professionals on hospital-wide change management projects; developing a website and hospital-wide patient and family education system; project lead for strategic planning for a new cancer rehabilitation center; and leading the inception of the nursing research committee. Former experience as an associate professor of nursing and a nurse manager includes serving on a university IRB board; teaching epidemiology, research, leadership and management at the graduate school level; developing and administering an outpatient dual-diagnosis program servicing children and families; and securing outside funding to pursue clinical research projects that resulted in publications in peer-reviewed journals and awards.

Tabitha Pearsall received a business degree in Seattle, WA and has 25 years operations experience, 11 years of experience utilizing Lean or Six Sigma improvement methodologies, with the last eight years focused in healthcare. She is Lean Certified through John Black & Associates, whose method is modeled after the Toyota Production System. She has implemented improvement programs in three organizations, two of which are in healthcare focused on Lean. Currently, Director of Performance Improvement at a large acute rehabilitation hospital, creating structure and implementing plan for integrating Lean methods and facilitating improvements hospital wide.

Patricia J. Murphy has over 30 years of experience in nursing leadership and education. She currently is the Associate Chief Nurse at a large acute inpatient rehabilitation institute where she is responsible for the operations of seven inpatient-nursing units, the nursing supervisors, radiology, respiratory therapy, laboratory services, dialysis, and chaplaincy. In this leadership role, she identifies, facilitates, implements, supports, and monitors evidence based nursing practices, projects and nursing development initiatives in order to improve nurse sensitive patient outcomes and add to the body of knowledge of rehabilitation nursing practice. Former experience includes Director of Oncology Services and Hospice; strategic planning of a new cancer center; leading quality projects in oncology and within the stem cell transplant unit; designing and implementing an oncology support program; and developing and implementing a complementary therapy program to support inpatients, outpatients, and the community.

Eileen French received a BSN from Northern Illinois University and an MSN from Loyola University. She is certified in rehabilitation nursing and has worked for over 30 years at a large acute inpatient rehabilitation institute, as a direct care nurse, clinical educator, clinical nurse consultant, and nurse manager. She is currently Manager of Nursing Outcomes, and has led a group of nurses responsible for planning and initiating bedside shift report in this rehabilitation setting.

- Figures/Tables

The complexity of healthcare calls for interprofessional collaboration to improve and sustain the best outcomes for safe and high quality patient care. Historically, rehabilitation nursing has been an area that relies heavily on interprofessional relationships. Professionals from various disciplines often subscribe to different change management theories for continuous quality improvement. Through a case review, authors describe how a large, Midwestern, rehabilitation hospital used the crosswalk methodology to facilitate interprofessional collaboration and develop an intervention model for implementing and sustaining bedside shift reporting. The authors provide project background and offer a brief overview of the two common frameworks used in this project, Lewin’s Three-Step Model for Change and the Lean Systems Approach. The description of the bedside shift report project methods demonstrates that multiple disciplines are able to utilize a common framework for leading and sustaining change to support outcomes of high quality and safe care, and capitalize on the opportunities of multiple views and discipline-specific approaches. The conclusion discusses outcomes, future initiatives, and implications for nursing practice.

Key words: Outcomes, quality improvement, interprofessional collaboration, Lewin, Lean, crosswalk, case review, outcomes

Providing today’s healthcare requires professional collaboration among disciplines to address complex problems and implement new practices, processes, and workflows. Providing today’s healthcare requires professional collaboration among disciplines to address complex problems and implement new practices, processes, and workflows ( AACN, 2011 ; Bridges, Davidson, Odegard, Maki, &Tomkowski, 2011 ; IOM, 2011 ). Often this collaboration magnifies competing or alternative discipline specific theories, language, and strategies to lead and sustain change management and to implement and support Continuous Quality Improvement (CQI) projects. Initially, professionals may perceive these differing views as mutually exclusive.

Lewin’s Three-Step Model Change Management is highlighted throughout the nursing literature as a framework to transform care at the bedside ( Shirey, 2013 ). One criticism of Lewin’s theory is that it is not fluid and does not account for the dynamic healthcare environment in which nurses function today ( Shirey, 2013 ). With the need to streamline resources and provide quality and safe healthcare, nurse leaders have focused on a rapid cycle approach to lead and sustain quality improvement changes at the bedside. One specific approach that is gaining rapid attention in healthcare is the “Lean System” for transformation. Experts assert that Lewin’s theory provides the fundamental principles for change, while the Lean system also provides the particular elements to develop and implement change, including accountability, communication, employee engagement, and transparency. The purpose of this case review is to describe how one large, Midwestern, rehabilitation facility used a crosswalk methodology to promote interprofessional collaboration and to design an intervention model comes to implement and sustain bedside shift reporting.

Project Background: Setting, Theoretical Bases, and Topic of Interest

Founded in the mid-1950s, this 182-bed, acute, inpatient rehabilitation facility (IRF) is located in a large Midwestern city and known for its commitment to promoting interprofessional and collaborative patient care. Rehabilitation is an interprofessional practice by nature that requires physiatrists, nurses, occupational therapists, speech therapists, physical therapists, and ancillary departments to collaborate to identify and achieve patient goals and outcomes. In early spring of 2017, the IRF will open a new research hospital to replace the current building. The new research hospital, a private, not-for-profit acute in-patient and outpatient rehabilitation facility, will expand patient care and combine research activities that translate directly to patient care in real time to improve patient outcomes.

This evolving research hospital environment requires that nurse executives demonstrate collaborative problem solving across the spectrum of care. Nurse leaders and executives’ formal training supports frequent use of Lewin’s Three-Step Model for Change Management. Meanwhile, healthcare institutions’ performance improvement departments often institute the Lean Systems Approach to quality improvement ( Toussaint & Berry, 2013 ; Toussaint & Gerad, 2010 ).

Integrating language from the Lean model within the theoretical basis of change theories used by the IRF healthcare culture would likely be a key factor for success continuous quality improvement activities. The IRF executive leadership team identified that the organization was reliable in initiating improvements, but was challenged to sustain and spread improvements throughout the organization. The Lean model had been adapted as the improvement system for the IRF. Integrating language from the Lean model within the theoretical basis of change theories used by the IRF healthcare culture would likely be a key factor for success continuous quality improvement activities. The Director of Performance Improvement gained leadership team approval to lead an effort to connect the Lean System tools with concepts that were common to several change management theories or frameworks, such as Diffusion of Innovations Theory; Donabedian’s Structure, Process, and Outcomes Framework; and the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) Rapid Cycle Improvement Model, including Lewin ( Donabedian, 2003 ; IHI, 2001 ; Lewin, 1951 ; Rogers, 2003 ).

Concurrently, the manager of nursing outcomes met with her clinical nursing team to plan a pilot project for bedside shift reporting (BSR). Ultimately, this project serves to coalesce the aforementioned simultaneous events of the new research environment of the facility and the combination of change theory and Lean model concepts into a workable framework for interprofessional collaboration. While the BSR is not the focus of this case review, this project served as a catalyst for the interprofessional collaboration among executives; mid-level and staff nurses; performance improvement professionals; the patient-family education resource center; and director of ethics. The purpose of this article is to discuss an interprofessional collaboration that sought consensus among members of different disciplines who typically utilized different theoretical approaches to problem solving. We selected the crosswalk method to further collaboration and to create an intervention model for BSR. As BSR happened to be a substantive topic of interest to the organization, a natural opportunity emerged to display the utility of a crosswalk method as a tool to developing an intervention model.

Brief Overview: Lewin’s Model for Planned Change and the Lean Systems Approach

Inherent in interprofessional collaboration is a requisite that each discipline shares an understanding of the similarities and a common language of the change process... With the current emphasis on interprofessional problem-solving approaches for CQI in mind, collaboration becomes an essential part in delivering quality care and leading CQI projects ( AACN, 2011 ; Bridges et al., 2011 ; IOM, 2011 ). Inherent in interprofessional collaboration is a requisite that each discipline shares an understanding of the similarities and a common language of the change process it proposes to use to develop an intervention model. Because the language and perspectives differ, professionals often struggle to find common ground for understanding so that each discipline maintains an influence. Historically, many nurses have subscribed to Lewin’s Three-Step Model for Change ( Shirley 2013 ). For the past 10 years, the Lean System Approach has been at the forefront of efforts to implement and sustain change in healthcare delivery organizations (D'Andreamatteo, Lappi, Lega, & Sargiacomo, 2015 ). This section provides a brief overview of Lewin’s Three-Step Model for Change and the Lean System Approach to change.

Lewin’s Three-Step Model for Change Healthcare organizations are complex adaptive systems where change is a complex process with varying degrees of complexity and agreement among disciplines. The Change Model. Complex adaptive systems require that, in order for organizations to maintain equilibrium and survive, the organizations must respond to an ever-changing environment. Healthcare organizations are complex adaptive systems where change is a complex process with varying degrees of complexity and agreement among disciplines ( Plsek & Greenhalgh, 2001 ; Porter-O’Grady & Malloch, 2011 ). Lewin’s Change Management Theory ( Lewin, 1951 ) is a common change theory used by nurses across specialty areas for various quality improvement projects to transform care at the bedside ( Chaboyer, McMurray, & Wallis, 2010 ; McGarry, Cashin & Fowler, 2012 ; Shirey, 2013 ; Suc, Prokosch & Ganslandt, 2009 ; Vines, Dupler, Van Son, & Guido, 2014 ).

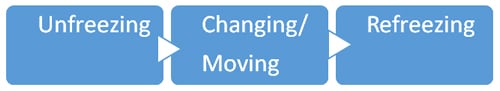

Lewin’s theory proposes that individuals and groups of individuals are influenced by restraining forces, or obstacles that counter driving forces aimed at keeping the status quo, and driving forces, or positive forces for change that push in the direction that causes change to happen. The tension between the driving and restraining maintains equilibrium. Changing the status quo requires organizations to execute planned change activities using his three-step model. This model consists of the following steps ( Lewin 1951 ; Manchester, et al., 2014 ; Vines, et al., 2104 ).

- Unfreezing, or creating problem awareness, making it possible for people to let go of old ways/patterns and undoing the current equilibrium (e.g., educating, challenging status quo, demonstrating issues or problems)

- Changing/moving, which is seeking alternatives, demonstrating benefits of change, and decreasing forces that affect change negatively (e.g., brainstorming, role modeling new ways, coaching, training)

- Refreezing, which is integrating and stabilizing a new equilibrium into the system so it becomes habit and resists further change (e.g., celebrating success, re-training, and monitoring Key Performance Indicators [KPIs])

Other Considerations . Criticisms of Lewin’s change theory are lack of accountability for the interaction of the individual, groups, organization, and society; and failure to address the complex and iterative process of change ( Burnes, 2004 ). Figure 1 depicts this change model as a linear process.

Figure 1. Lewin’s Three-Step Model for Planned Change

However, in addition to change theory, healthcare has also shifted to a robust system for change called the Lean Systems Approach.

Lean Systems Approach

The Lean Model. The Lean Systems Approach (Lean) is a people-based system, focusing on improving the process and supporting the people through standardized work to create process predictability, improved process flow, and ways to make defects and inefficiencies visible to empower staff to take action at all levels ( Liker, 2004 ; Toussaint & Gerard, 2010 ). To that end, Lean creates value for internal and external customers through eliminating waste (e.g., time, defects, motion, inventory, overproduction, transportation, processing). To create value and meet customer needs, Lean resources are provided in a robust toolkit. Value stream mapping is a tool to identify process relating to material and information and people flow. It is useful to identify value added and non-value added actions. Value stream mapping is then used to create a plan to eliminate waste, create transparency (visual management), implement standard work, improve flow, and sustain change.

...Lean is a way of thinking about improvement as a never-ending journey. Overall, Lean is a way of thinking about improvement as a never-ending journey. Lean starts as a top-down, bottom-up approach, requiring leadership support. Over time, the goal is for all staff to contribute to problem solving and designing improvements to add value as defined by the customer. Value is defined as the services that the customer is willing to purchase ( Toussaint &Gerard, 2010 ).

In healthcare, adding value or meeting the customer or patient needs often occurs at the bedside, and nurses who provide care are closest to the bedside. Lean offers a common system, philosophy, language, and tool kit for improvement. Many quality improvement approaches have parallels and one well known is Deming’s Improvement Model of Plan, Do, Check, Act ( Deming Institute, 2015 ). Deming’s model is also utilized in the Lean approach as a structure to make and sustain improvements. The IHI refers to this as Plan, Do, Study, Act-Rapid Cycle Improvement Model ( Scoville & Little, 2014 ). Both models, like Lean, strive for structure, methods, and improvement that never ends – continuous improvement, or Kaizen, in Lean terms. For an organization to reap the full benefit of the Lean approach, it is necessary to integrate a system-wide approach ( D’Andreamatteo et al., 2015 ; Liker, 2004 ; Toussaint, 2015 ). Lean tools are designed to work together to maximize improvements within an organization and create a culture that embraces the journey of continuous quality improvement.

...the Lean System exemplifies a culture where each staff member is empowered to make change. To this end, the Lean System exemplifies a culture where each staff member is empowered to make change. This culture focuses on creating value, supporting staff, and improving process flow to increase quality, reduce costs, and increase efficiency. Interprofessional collaboration is a necessary component to make improvements that involve going to the gemba (i.e., where the work is done or patient floor), to observe with our own eyes, ask questions, and learn. Other aspects of Lean are the importance of utilizing data and identifying root cause (5 Why’s, or asking why five times). Becoming a learning organization by creating a safe environment to make mistakes (taking into account patient safety) is key in Lean; it is better to try, fail, learn, adjust, than to not try at all ( Simon & Canacari, 2012 ). The Lean tools provide a medium for staff to break down problems, eliminate non-value added activities, and not only implement a new standard process, but sustain it as well ( Kimsey, 2010 ; Liker, 2004 ; Mann, 2010 ).

Kaizen, or continuous improvement, means adjusting how healthcare organizations operate to create value. Other Considerations . Incorporating Lean into the healthcare industry has been met with barriers. A common reaction to Lean within healthcare is that it only applies to manufacturing cars (e.g., the Toyota Production System) ( Liker, 2004 ; Toussaint & Gerad, 2010 ; Toussaint & Berry, 2013 ). This reaction, in itself, becomes a barrier to apply and incorporate Lean into the healthcare industry. The interpretation of standard work being inflexible is also a barrier within healthcare. Standard work can be made flexible to adjust to unique patient scenarios and change according to changes in the healthcare environment, technology, and patient needs. Kaizen, or continuous improvement, means adjusting how healthcare organizations operate to create value. Many hospitals have been applying Lean, such as Virginia Mason Medical Center, ThedaCare, Mayo Clinic, and Seattle Children’s Hospital ( Toussaint & Berry, 2013 ). Furthermore, regulatory changes, such as those from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), and pressure on healthcare organizations to deliver high quality, safe and cost-effective care ( Toussaint & Berry, 2013 ).

[A no-blame culture] creates an environment whereby any member(s) of the organization can take action to improve performance and outcomes. Healthcare can often be a shame and blame culture, which is very different than Lean ( Simon & Canacari, 2012 ; Toussaint & Gerad, 2010 ). A fundamental principle of Lean is that it attacks the process rather than the person or people to create a no-blame culture. The Lean Systems Approach is designed to build trust, engage staff to trystorm (try ideas rapidly to see if they work), measure improvement, and implement and sustain. The Lean System is designed for problems to rise to the surface and become transparent so that they can be addressed. This transparency (visual management), along with clear measures and coaching, keeps important concerns in view of staff. This creates an environment whereby any member(s) of the organization can take action to improve performance and outcomes ( Mann, 2010 ).

Considering concepts from both Lewin’s Three-Step Model for change and the Lean Systems Approach opens the possibility of using the best of each of these models to facilitate interprofessional collaboration and a problem-solving approach. Through interprofessional collaboration, nursing and other disciplines can continue to improve processes and outcomes for the greater good of patient outcomes and the healthcare industry ( Brooks, Rhodes & Tefft, 2014 ). The next section offers a short explanation of the concept of interprofessional collaboration, which served as the problem-solving basis of our project to develop an intervention model for bedside shift reporting.

Interprofessional Collaboration: A Problem Solving Approach

...collaboration can enhance collegial relationships and collapse professional silos, as well as improve patient outcomes. In one of the more widely-cited definitions of collaboration, Gray ( 1989 ) describes "a process through which parties who see different aspects of a problem can constructively explore their differences and search for solutions that go beyond their own limited vision of what is possible” ( p. 5 ). Collaboration involves multiple disciplines that span across individual professional silos, hence the term interprofessional is used for this case review. Collaboration is based on a naturalistic inquiry process, whereby each party takes on the teacher role, educating others, and the learner role, an openness and willingness to receive information from others, relinquishing power and control to move beyond their own perspectives for benefit of change ( Denzin & Lincoln, 2011 ; Gray, 1989 ).

Communication serves as a mechanism for sharing knowledge and is the hallmark for improving working relationships ( Gray, 1989 ). Collaborative efforts create spaces where connections are made, ideas are shared, opportunities for innovation flourish, and strategies for change to transpire ( London, 2012 ). Today, healthcare associations and committees work diligently to ensure that interprofessional collaboration is part of their educational curriculum and practice standards.

The American Nurses Association ( ANA, 2009 ) lists “collaboration” as a standard of practice for nursing administration. Similarly, the Institute of Medicine ( IOM, 2011 ) recommends that “nurses should be full partners, with physicians and other health professionals, in redesigning healthcare in the United States” ( p. 32 ).

Nursing driven improvement projects and change initiatives that require interprofessional collaboration are common in redesigning healthcare delivery. However, simply grouping healthcare professionals from differing disciplines together to work on a project does not always cultivate collaboration ( Kotecha et al., 2015 ). Effective interprofessional collaboration is a blending of professional cultures that arises from sharing knowledge and skills to improve patient care, and exhibits accountability, coordination, communication, cooperation, and mutual respect among its members ( Bridges et al., 2011 ; Reber, et al., 2011 ). Such collaboration can enhance collegial relationships and collapse professional silos, as well as improve patient outcomes ( Kotecha et al., 2015 .).

There are facilitating and hindering factors for interprofessional collaboration associated with nursing driven projects ( Tviet, Belew, & Noble, 2015 ). Facilitating factors cited include: identifying key roles and individuals; soliciting early involvement and commitment from individuals and the group; and continuing to monitor progress and compliance well after implementation, including follow up with staff whose compliance is low. Hindering factors cited include: difficulty coordinating meeting times among multiple professions; bias of each profession as to what would work for them; discipline specific professional jargon; and the ability of one person or group to resist change and stop the project from moving forward ( Ellison, 2014 ).

Interprofessional collaboration lessens discipline-specific perspectives, thus improving quality of care and patient outcomes, and increasing efficiency and reducing healthcare resources. Interprofessional collaboration lessens discipline-specific perspectives, thus improving quality of care and patient outcomes, and increasing efficiency and reducing healthcare resources ( Patton, Lim, Ramlow, & White, 2015 ). An initial effort by all parties to visually display alignments and confront differences may minimize frustration and miscommunication among professionals. As we considered the synergy of concepts from both the Lewin Three-Step Model for Change and Lean Systems Approach, our idea was to use crosswalk methodology to begin collaboration with an interprofessional perspective.

Crosswalk Methodology

The crosswalk is a robust qualitative method, often associated with theory building and inductive reasoning, which provides a compressed display or visual of meaningful information ( Miles & Huberman, 1994 ). Table 1 demonstrates the utility of the crosswalk method across domains, with examples from various domains to make comparative evaluations among programs, assessment tools, and theories to determine alignments and misalignments. Advantages of conducting a crosswalk are that it elucidates key connections and critical opportunities for growth and knowledge expansion, equitable resource allocation, and inquiry; and it depicts a large amount of information in a clear and concise manner. Disadvantages of the crosswalk method are that it often lacks the rigor and depth necessary to make causal links or provide generalizable information ( Miles & Huberman, 1994 ). However, since the goals of qualitative methods are not causal links or generalizability, crosswalks can offer an intentional, systematic method to consider complex information in a meaningful way.

Table 1. Examples: Utility of Crosswalk Across Domains

|

|

|

|

| Academia | American Association of Colleges of Nursing, 2011 | To show interface between the nine master’s essentials against themes in the IOM’s report ( ). |

| Administration- | Rudisill & Thompson, 2012 | To conduct a gap analysis between required skills for nurse executives and competency assessment. |

| Clinical | Brandenburg, Worrall, Rodgriguez, & Bagraith, 2015 | To delineate self-report measures using two aphasia tools. |

| Clinical | Sink, et al., 2015 | To compare the findings of two mental state exams in the African Americans for accurate interpretation. |

| Public Policy, & Accreditation | Kamoie & Borzi, 2001 | To confirm congruency between the final HIPAA privacy rule and federal substance abuse policy. |

| Public Health Surveillance | Parsons, Enewold, Banks, Barrett & Warren, 2015 | To link unique physician identifiers from two national directories so that Medicare data can be used for research. |

| Public Health & Performance Management | Gorenflo, Klater, Mason, Russo, & Rivera, 2014; Kamoie & Borzi, 2001 | To demonstrate the robust congruencies between two performance management programs. |

| Research | Lai, Cella, Yanez, & Stone, 2014 | To further refine the psychometric properties of two fatigue scales. |

Bedside Shift Report Project Methods

Through a case review, we will describe how this IRF implemented a CQI process that integrated theory into practice via both Lewin’s theory and a Lean Systems Approach. We used crosswalk methodology to compare Lewin’s Theory and Lean, a process that ultimately led to collaboration and the creation of an intervention model for BSR. For this case, the crosswalk was used to visually examine the relationships, concepts, and language used within two approaches to change and quality improvement. Team members visualized the similarities and dissimilarities and adopted the teacher and learner role necessary to move the BSR project forward.

Our Team Initially, an interprofessional team of six consisting of executives; mid-level and staff nurses; performance improvement professionals; the patient-family education and resource center; and director of ethics convened through semi-monthly work sessions from early spring 2015 to early fall 2015 for the purpose of BSR. During interprofessional work sessions, the language used among team members when discussing the improvement process differed, which resulted in confusion among members and became a barrier to collaboration.

What the team experienced was similar to what Andersen and Rovik ( 2015 ) described as the many interpretations of lean thinking. Different definitions or interpretations of concepts were being made, prolonging the improvement and sustaining process. D'Andreamatteo et al. ( 2015 ) suggested that “...a common definition should be established to distinguish what is Lean and what is not…” ( p. 10 ). The team wanted all participants of the various disciplines to see the commonalities of approach, to create a better known definition of each concept, and to continue to build collaboration and understanding for better outcomes.

Visually showing theoretical connections helped improve the understanding of all team members and thus our process became more adoptable to the group. Team members identified the translation barrier very early when they conducted a crosswalk of concepts and language from Lewin’s Change Theory to the language of Lean tools and principles. Lean, being both a system and a way of thinking, and not just a quick process to make point improvements, was linked with Lewin’s, three-step model of planned change. This crosswalk, demonstrated in Table 2, launched the connection to understand improvement theory and techniques. Visually showing theoretical connections helped improve the understanding of all team members and thus our process became more adoptable to the group.

Our Process and Crosswalk Once we determined a topic of interest (bedside reporting) our interprofessional team used the following process to problem solve:

- Convened an interprofessional working group consisting of executive, mid-level and staff nursing, performance improvement, the patient-family education resource center, and director of ethics;

- Reviewed literature on BSR to familiarize team with evidence-based practice for BSR;

- Reviewed Lewin Three-Step Model for Planned Change;

- Reviewed Lean System Approach for CQI;

- Created a crosswalk;

- Refined crosswalk based on team feedback;

- Finalized crosswalk ( See Table 2 );

- Presented to nursing staff-at-large to spread understanding.

The final crosswalk led to two outcomes, described below.

Table 2. Crosswalk: Lewin Change Theory and Lean Concepts

|

|

|

|

| (Ask why is this a focus; collect data & information to tell story; define baseline) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| (Sustain, stabilize, show improvement) |

Our Outcomes This case review illustrates two outcomes. The first outcome of our project was enriched interprofessional collaboration and the second outcome was an intervention model BSR ( see Figure 2 ). These are briefly described below.

The rich interprofessional collaboration that resulted in our final crosswalk illustrated the compatibility between Lewin’s Theory and Lean, operationalized the stages of change, and provided tangible strategies and tools to implement and sustain a BSR project. This project will be implemented in 2016.

During a debriefing, the primary author (E.W) asked team members to comment about their experience with this CQI project. Anecdotal information illustrates furthered collaboration within this IRF. Team members verified the accuracy of the anecdotal information by reviewing its written form and gave permission for publication in this article.

The following remarks display three themes related to collaboration:

…the teacher-learner process where members move between educating others, and gaining knowledge by being open and willing to understand others; I came to the team with one idea about how to change systems for the benefit of patient care. …Initially, I felt the team was polarized due to their differing ways of thinking or points of view about change. Once we conducted the crosswalk between Lean and Lewin, I could visualize how we were saying similar things, but in a different way. I learned from my team members and I believe they learned from me. ... I listened and I also felt heard. [I] loved this experience and would use the crosswalk early in any interprofesssional project. …the opportunity for innovative problem solving that transpired above your own world view for the common good; Nurses first came to the team with the feeling that Lean was just a passing fancy that would attempt to improve sustaining change and would fail and soon be forgotten. [However], they came away with useful tools to support their on-going challenges to continually improve patient care and nursing outcomes. …the promotion for enhanced partnerships among professionals. Finding commonality in the Lewin and Lean languages and approach provided a way for our broader group to connect and discuss improvements in a proactive way. Recognizing we were not against one another but working towards the same goal for quality of care. Since this took crosswalk took place, our partnerships are tighter due to a better understanding of each other’s disciplines and perspective. We have a point of reference to go back to for discussion. Mutual respect was enhanced allowing us to have different conversations now with better focus on solutions.

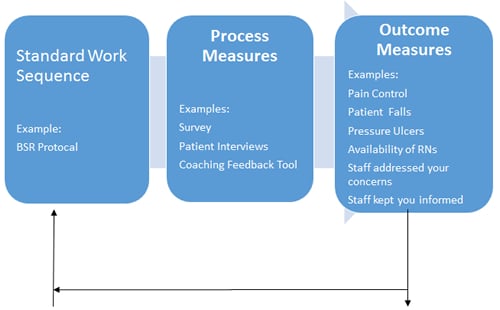

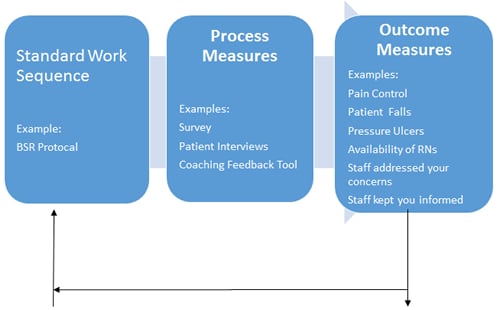

As noted previously, the manager of nursing quality and her clinical staff had done preliminary work on BSR. The second outcome of our subsequent team work, the intervention model in Figure 2 , assimilated and utilized Lean and Lewin tools and principles that comprise the Standard Work Sequence (i.e,, the BSR protocol). Examples of this protocol included:

- The design and target population of intervention

- Process measures, such as measures of the intended delivery of the intervention (e.g., survey assessing on thoroughness, accuracy and efficiency of the BSR, patient interviews, and staff coaching and feedback tool)

- Outcome measures, which included measures for the intended response or results of the intervention (e.g., pain control, patient falls, pressure ulcers, availability of RNs, staff addressing [patients’] concerns, and staff keeping patient informed)

Figure 2. Intervention Model for Beside Shift Reporting

This article describes the two outcomes resulting from our interprofessional collaborative team effort to address the topic of interest using an intentional theoretical approach. As the intervention model is implemented, baseline and follow-up data will be obtained on the process and outcomes measures listed above.

Developing and utilizing our crosswalk to educate nurses on the Lean philosophy and tools adopted by this organization for CQI also familiarized non-nursing members of the interprofessional team with Lewin’s work and the common nursing culture and language for change. It was the “aha” moment for all team members. This breakthrough led to further collaboration and demonstrated the commonalities between Lewin’s Three-Step Model for Change and the Lean Systems Approach philosophy for CQI. Collaboration enhanced nursing buy-in to this process and a better understanding of the application of Lean principles.

Critical to collaboration is that parties realize that talking about and planning collaboration does not mean that it will happen quickly and easily. Barriers to communicating and understanding the process were greatly reduced. At the conclusion, nurses could quickly and easily see the benefits of using this adaptive model to implement and sustain change. Critical to collaboration is that parties realize that talking about and planning collaboration does not mean that it will happen quickly and easily. Ultimately, the crosswalk offered two positive outcomes. The first was that it furthered interprofessional collaboration by engaging team members to clarify language and mental models of management approaches. The second outcome was the development of the intervention model for BSR project, taking preliminary work on a project by the Manager of Nursing Outcomes and her team to the next level, with an end product that is being implemented in 2016.

Future directions for our team are to determine the usefulness of the crosswalk for multi-discipline initiatives, such as the “patient up and ready” program, a joint initiative between nursing and allied health to ensure that patients are available and ready for each scheduled therapy session. In sum, the initial outcomes of this case review demonstrate willingness among providers in multiple disciplines to seek consensus in understanding and utilize a shared framework to lead and sustain change for high quality and safe patient care. Doing so capitalizes on the expanded knowledge and expertise of multiple views and discipline-specific approaches to change management.

Elizabeth Wojciechowski, PhD, PMHCNS-BC Email: [email protected]

Tabitha Pearsall, AAB, Lean Certification Email: [email protected]

Patricia Murphy, MSN, RN, NEA-BC Email: [email protected]

Eileen French, MSN, RN, CRRN Email: [email protected]

Brooks, V., Rhodes, B., & Tefft, N. (2014). When opposites don't attract: One rehabilitation hospital's journey to improve communication and collaboration between nurses and therapists. Creative Nursing , 20(2), 90-94.

Burnes, B. (2004). Kurt Lewin and complexity theories: back to the future? Journal of Change Mnagement , 4 (4), 309-325. doi: 10.1080/1469701042000303811

Ellison, D. (2014). Communication Skills. Nursing Clinics of North America , 50(1), 45-57. doi: 10.1016/j.cnur.2014.10.004

American Association of Colleges of Nursing. (2011). Crosswalk of the AACN master’s essentials and the IOM’s Future of Nursing: Leading change, advancing health recommendations . Retrieved from http://www.aacn.nche.edu/faculty/faculty-tool-kits/masters-essentials/Crosswalk.pdf

American Nurses Association. (2009). Nursing administration: Scope and standards of practice . (3rd ed.) Silver Springs, MD: American Nurses Association.

Andersen, H., & Rovik, K. A. (2015). Lost in translation: A case-study of the travel of lean thinking in a hospital. BMC Health Services Research, 15 , 401. doi: 10.1186/s12913-015-1081-z

Brandenburg, C., Worrall, L., Rodriguez, A., & Bagraith, K. (2015). Crosswalk of participation self-report measures for aphasia to the ICF: What content is being measured? Disability and Rehabilitation , 37(13), 1113-1124. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2014.955132

Bridges, D., Davidson, R., Odegard, P., Maki, I., & Tomkowski, J. (2011). Interprofessional collaboration: Three best practice models of interprofessionaleducation. Medical Education Online . doi: 10.3402/meo.v161i0.6035

Chaboyer, W., McMurray, A., & Wallis, M. (2010). Bedside nursing handover: a case study. International Journal of Nursing Practice , 16(1), 27-34. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-172X.2009.01809.x

D'Andreamatteo, A., Ianni, L., Lega, F., & Sargiacomo, M. (2015). Lean in healthcare: A comprehensive review. Health Policy, 119 (9), 1197-1209. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2015.02.002

The W. Edwards Deming Institute. (2015). The Plan, do study, act cycle (PDSA). Retrieved from https://www.deming.org/theman/theories/pdsacycle

Denzin, N. & Lincoln, Y. (2011). The Sage handbook of qualitative research . Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

Donabedian, A. (2003). An introduction to quality assurance in health care . (1st ed., Vol. 1). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Gorenflo, G. G., Klater, D. M., Mason, M., Russo, P., & Rivera, L. (2014). Performance management models for public health: Public Health Accreditation Board/Baldrige connections, alignment, and distinctions. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice , 20(1), 128-134. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0b013e3182aa184e

Gray, B. (1989). Collaborating: Finding common ground for multiparty problems . San Francisco, CA: Josey-Bass.

Interprofessional Education Collaborative Expert Panel. (2011). Core competencies for interprofessional collaborative practice: Report of an expert panel . Washington, DC: Interprofessional Education Collaborative. Retrieved from http://www.aacn.nche.edu/education-resources/IPECReport.pdf

Institute of Medicine. (2011). The Future of nursing: Leading change, advancing health. Retrieved from http://iom.nationalacademies.org/Reports/2010/The-Future-of-Nursing-Leading-Change-Advancing-Health.aspx

Kamoie, B., & Borzi, P. (2001). A crosswalk between the final HIPAA privacy rule and existing federal substance abuse confidentiality requirements. Issue Brief (George Washington University: Center for Health Service Research and Policy ) , (18-19), 1-52.

Kimsey, D. (2010). Lean methodology in health care. AORN Journal, 92 (1), 53-60. doi:10.1016/j.aorn.2010.01.015

Kotecha, J., Brown, J. B., Han, H., Harris, S. B., Green, M., Russell, G., . . . Birtwhistle, R. (2015). Influence of a quality improvement learning collaborative program on team functioning in primary healthcare. Families, System, & Health, 33 (3), 222-230. doi: 10.1037/fsh0000107

Lai, J. S., Cella, D., Yanez, B., & Stone, A. (2014). Linking fatigue measures on a common reporting metric. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 48 (4), 639-648. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2013.12.23

Lewin, K. C. (1951). Field theory in social science . New York, NY: Harper & Row.

Liker, J. K. (2004). The Toyota Way: 14 Management Principles from the world’s greatest manufacturer . New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

London, S. (2012). Building collaborative communities. In M. Bak-Mortensen & J. Nesbitt. (Eds.), On Collaboration (n.pag.) . London: Tate. Retrieved from http://www.scottlondon.com/articles/oncollaboration.html

Manchester, J., Gray-Miceli, D. L., Metcalf, J. A., Paolini, C. A., Napier, A. H., Coogle, C. L., & Owens, M. G. (2014). Facilitating Lewin's change model with collaborative evaluation in promoting evidence based practices of health professionals. Evaluation and Program Planning, 47 , 82-90. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2014.08.007

Mann, D. (2010). Creating a lean culture: Tools to sustain lean conversions (2nd ed.). New York: Productivity Press.

McGarry, D., Cashin, A., & Fowler, C. (2012). Child and adolescent psychiatric nursing and the 'plastic man': Reflections on the implementation of change drawing insights from Lewin's theory of planned change. Contemporary Nurse, 41 (2), 263-270. doi: 10.5172/conu.2012.41.2.263

Miles, M. B. & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Parsons, H. M., Enewold, L. R., Banks, R., Barrett, M. J., & Warren, J. L. (2015). Creating a National Provider Identifier (NPI) to Unique Physician Identification Number (UPIN) crosswalk for Medicare data. Medical Care . doi: 10.1097/mlr.0000000000000462

Patton, C. M., Lim, K. G., Ramlow, L. W., & White, K. M. (2015). Increasing efficiency in evaluation of chronic cough: A multidisciplinary, collaborative approach. Quality Management in Health Care, 24 (4), 177-182. doi: 10.1097/qmh.0000000000000072

Plsek, P. E., & Greenhalgh, T. (2001). Complexity science: The challenge of complexity in health care. BMJ, 323 (7313), 625-628.

Porter-O’Grady, T. & Malloch, K. (2011). Quantum leadership: Advancing innovation, transforming healthcare (3rd ed.). Sudbury, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Reber, P. A., DiPietro, E. A., Paraway, Y., Obst, B. P., Smith, R. A., & Koller, C. L. (2011). Communication: The key to effective interdisciplinary collaboration in the care of a child with complex rehabilitation needs. Rehabilitation Nursing, 36 (5), 181-185, 213.

Rogers, E. M. (2003). Diffusion of Innovations (5th ed.). New York, NY: Free Press.

Rudisill, P. T., & Thompson, P. A. (2012). The American Organization of Nurse Executives system CNE task force: A work in progress. Nursing Administration Quarterly, 36 (4), 289-298. doi: 10.1097/NAQ.0b013e3182669453

Scoville R. & Little K. (2014). Comparing lean and quality improvement. IHI White Paper . Cambridge, Massachusetts: Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Retrieved from http://www.ihi.org/resources/pages/ihiwhitepapers/comparingleanandqualityimprovement.aspx

Shirey, M. R. (2013). Lewin’s theory of planned change as a strategic resource. Journal of Nursing Administration, 43 (2), 69-72. doi: 10.1097/NNA.0b013e31827f20a9

Simon, R. W. & Canacari, E. G. (2012). A Practical guide to applying lean tools and management principles to health care improvement projects. AORN, 95 (1), 85-100; quiz 100-103. doi: 10.1016/j.aorn.2011.05.021

Sink, K. M., Craft, S., Smith, S. C., Maldjian, J. A., Bowden, D. W., Xu, J., . . . Divers, J. (2015). Montreal cognitive assessment and modified mini mental state examination in African Americans. Journal of Aging Research, 2015 , 872018. doi: 10.1155/2015/872018

Suc, J., Prokosch, H. & Ganslandt, T. (2009). Applicability of Lewin s change management model in a hospital setting. Methods of Information in Medicine , 48 (5), 419-28. doi: 10.3414/ME9235

Tviet, C., Belew, J., & Noble, C. (2015). Prewarming in a pediatric hospital: Process improvement through interprofessional collaboration. Journal of PeriAnesthesia Nursing, 30 (1), 33-38. doi: 10.1016/j.jopan.2014.01.008

Toussaint, J.S. (2015). A Rapidly adaptable management system. Journal of Healthcare Management, 60 (5), 312-315.

Toussaint, J. S. & Berry, L. L. (2013). The promise of lean in health care. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 88 (1), 74-82. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2012.07.025

Toussaint, J. S., & Gerard, R. A. (2010). On the mend: Revolutionizing healthcare to save lives and transform the industry . Cambridge, MA, USA: Lean Enterprise Institute.

Vines, M. M., Dupler, A. E., Van Son, C. R., & Guido, G. W. (2014). Improving client and nurse satisfaction through the utilization of bedside report. Journal of Nurses in Professional Development, 30 (4), 166-173; quiz E161-162. doi: 10.1097/nnd.0000000000000057

|

|

|

|

| Academia | American Association of Colleges of Nursing, 2011 | To show interface between the nine master’s essentials against themes in the IOM’s report ( ). |

| Administration- | Rudisill & Thompson, 2012 | To conduct a gap analysis between required skills for nurse executives and competency assessment. |

| Clinical | Brandenburg, Worrall, Rodgriguez, & Bagraith, 2015 | To delineate self-report measures using two aphasia tools. |

| Clinical | Sink, et al., 2015 | To compare the findings of two mental state exams in the African Americans for accurate interpretation. |

| Public Policy, & Accreditation | Kamoie & Borzi, 2001 | To confirm congruency between the final HIPAA privacy rule and federal substance abuse policy. |

| Public Health Surveillance | Parsons, Enewold, Banks, Barrett & Warren, 2015 | To link unique physician identifiers from two national directories so that Medicare data can be used for research. |

| Public Health & Performance Management | Gorenflo, Klater, Mason, Russo, & Rivera, 2014; Kamoie & Borzi, 2001 | To demonstrate the robust congruencies between two performance management programs. |

| Research | Lai, Cella, Yanez, & Stone, 2014 | To further refine the psychometric properties of two fatigue scales. |

|

|

|

|

| (Ask why is this a focus; collect data & information to tell story; define baseline) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| (Sustain, stabilize, show improvement) |

May 31, 2016

DOI : 10.3912/OJIN.Vol21No02Man04

https://doi.org/10.3912/OJIN.Vol21No02Man04

Citation: Wojciechowski, E., Murphy, P., Pearsall, T., French, E., (May 31, 2016) "A Case Review: Integrating Lewin’s Theory with Lean’s System Approach for Change" OJIN: The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing Vol. 21 No. 2, Manuscript 4.

- Article May 31, 2016 Outcome Measurement in Nursing: Imperatives, Ideals, History, and Challenges Terry L. Jones, PhD, RN

- Article May 31, 2016 Information and Communication Technology: Design, Delivery, and Outcomes from a Nursing Informatics Boot Camp Manal Kleib, RN, MSN, MBA, PhD; Nicole Simpson, RN, BScN; Beverly Rhodes, RN, MSN

- Article October 26, 2017 Potential of Virtual Worlds for Nursing Care: Lessons and Outcomes Nitin Walia, PhD; Fatemeh Mariam Zahedi, DBA; Hemant Jain, PhD

- Article May 31, 2016 Why Causal Inference Matters to Nurses: The Case of Nurse Staffing and Patient Outcomes Deena Kelly Costa, PhD, RN; Olga Yakusheva, PhD

- Article May 31, 2016 Multigenerational Challenges: Team-Building for Positive Clinical Workforce Outcomes Jill M. Moore, PhD, RN, CNE; Marcee Everly, DNP, ND, MSN, RN, CNM; Renee Bauer,PhD, MS, RN

- Article March 15, 2017 A National Comparison of Rural/Urban Pressure Ulcer and Fall Rates Marianne Baernholdt, PhD, MPH, RN, FAAN; Ivora D. Hinton, PhD; Guofen Yan, PhD; Wenjun Xin, MS; Emily Cramer, PhD; Nancy Dunton, PhD, FAAN

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

Case studies in nursing theory. Orlando's theory

- PMID: 3636765

PubMed Disclaimer

Similar articles

- Communication and Technology: Ida Orlando's Theory Applied. Gaudet C, Howett M. Gaudet C, et al. Nurs Sci Q. 2018 Oct;31(4):369-373. doi: 10.1177/0894318418792891. Nurs Sci Q. 2018. PMID: 30223753

- Sensing presence and sensing space: a middle range theory of nursing. Orticio LP. Orticio LP. Insight. 2007 Oct-Dec;32(4):7-11. Insight. 2007. PMID: 18306939 Review. No abstract available.

- Orlando's deliberative nursing process theory: a practice application in an extended care facility. Faust C. Faust C. J Gerontol Nurs. 2002 Jul;28(7):14-8. doi: 10.3928/0098-9134-20020701-05. J Gerontol Nurs. 2002. PMID: 12168713

- Reformulation of deviance and labeling theory for nursing. Trexler JC. Trexler JC. Image J Nurs Sch. 1996 Summer;28(2):131-5. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.1996.tb01205.x. Image J Nurs Sch. 1996. PMID: 8690429 Review.

- Problematic situations in nursing: analysis of Orlando's theory based on Dewey's theory of inquiry. Schmieding NJ. Schmieding NJ. J Adv Nurs. 1987 Jul;12(4):431-40. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1987.tb01352.x. J Adv Nurs. 1987. PMID: 3655132

Publication types

- Search in MeSH

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

- Open access

- Published: 18 June 2024

Cognitive load theory in workplace-based learning from the viewpoint of nursing students: application of a path analysis

- Shakiba Sadat Tabatabaee 1 ,

- Sara Jambarsang 2 &

- Fatemeh Keshmiri 3

BMC Medical Education volume 24 , Article number: 678 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

151 Accesses

Metrics details

The present study aimed to test the relationship between the components of the Cognitive Load Theory (CLT) including memory, intrinsic and extraneous cognitive load in workplace-based learning in a clinical setting, and decision-making skills of nursing students.

This study was conducted at Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences in 2021–2023. The participants were 151 nursing students who studied their apprenticeship courses in the teaching hospitals. The three basic components of the cognitive load model, including working memory, cognitive load, and decision-making as the outcome of learning, were investigated in this study. Wechsler’s computerized working memory test was used to evaluate working memory. Cognitive Load Inventory for Handoffs including nine questions in three categories of intrinsic cognitive load, extraneous cognitive load, and germane cognitive load was used. The clinical decision-making skills of the participants were evaluated using a 24-question inventory by Lowry et al. based on a 5-point scale. The path analysis of AMOS 22 software was used to examine the relationships between components and test the model.

In this study, the goodness of fit of the model based on the cognitive load theory was reported (GIF = 0.99, CFI = 0.99, RMSEA = 0.03). The results of regression analysis showed that the scores of decision-making skills in nursing students were significantly related to extraneous cognitive load scores ( p -value = 0.0001). Intrinsic cognitive load was significantly different from the point of view of nursing students in different academic years ( p = 0.0001).

The present results showed that the CLT in workplace-based learning has a goodness of fit with the components of memory, intrinsic cognitive load, extraneous cognitive load, and clinical decision-making skill as the key learning outcomes in nursing education. The results showed that the relationship between nursing students’ decision-making skills and extraneous cognitive load is stronger than its relationship with intrinsic cognitive load and memory Workplace-based learning programs in nursing that aim to improve students’ decision-making skills are suggested to manage extraneous cognitive load by incorporating cognitive load principles into the instructional design of clinical education.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Cognitive load was introduced as a key theory in medical education [ 1 ] This theory guides the components of human cognitive architecture concerning learning and education to create a correct understanding of the characteristics and conditions of education and learning [ 2 ].

Cognitive load theory (CLT)

The CLT was first proposed in the 1980s by John Sweller [ 3 ]. This theory explains learning according to three important aspects including types of memory (working and long-term memory), learning process, and forms of cognitive load that affect learning [ 4 ].

The cognitive architecture assumed by CLT includes long-term memory (LTM) and working memory (WM). The key subsystem of memory in the CLT is working memory [ 5 ].

- Cognitive load

Cognitive load is defined as the load that a specific task imposes on the learner’s cognitive system [ 6 ]. In the CLT, three types of cognitive load are proposed, including intrinsic cognitive load (ICL), extraneous cognitive load (ECL), and germane cognitive load (GCL) [ 7 , 8 ]. ICL is related to the complexity of educational materials rather than their quantity [ 9 ]. ICL depends on several factors, including the individual’s skill, the number of information elements, and the degree of interaction of different elements of the tasks. ECL caused by the training format includes training strategies, training design, and teaching-learning methods [ 4 , 10 , 11 ]. GCL refers to the load imposed by the mental processes necessary for learning (such as the formation of schemata) [ 11 ]. Germane load means trying to build and modify learning schemata, which is mainly under the control of job components such as motivation, effort, and the learner’s metacognitive skills [ 7 ]. Also, the level of learner’s proficiency can moderate the ICL arising from the interaction of elements. This means that the availability and automaticity of the learner’s schemata can moderate intrinsic load [ 11 ].

Learning process

Education in medical science systems is a complex and multidimensional process that is affected by many factors [ 12 ]. In the process of clinical education, students need to learn several professional tasks and activities and apply them in the provision of health care services by simultaneously integrating a set of knowledge, skills, and behaviors [ 11 ]. These characteristics of clinical education can impose a high cognitive load on students and harm their effective learning [ 11 , 13 ].

CLT in health professions education

The CLT has emerged as one of the foremost models in educational psychology considered in different fields such as health professions education. The goal of CLT has been to improve learning at the individual student level in different environments including the classroom, and complex professional learning environments [ 14 ]. Sweller and colleagues showed there have been main developments in CLT and instructional design over the last 20 years. The ‘cognitive theory of multimedia learning’ focusing on the design of multimedia educational materials and the ‘four-component instructional design (4 C/ID)’ focusing on the design of whole-task courses and curricula have been built based on the CLT [ 15 ]. In addition, the CLT provides principles that are recommended to apply to the design of instructional messages and instructional units, such as lessons, written materials consisting of text and pictures, and educational multimedia (instructional animations, videos, simulations, games) [ 15 ].

The theoretical scope of the cognitive load has been expanded by including the physical environment as a key factor affecting cognitive load. Physical environments that evoke stress, emotions, and/or uncertainty raise new questions about how to deal with cognitive load. The questions require examining the human cognitive architecture of educational design in environments that are accompanied by uncertainty and stress [ 15 ]. Likewise, Paas et al. (2020) introduced variables affecting cognitive load and introduced factors including instructional design and learning environment as an effective factor that affects students’ learning process. They stated that the learning environment can affect cognitive load and suggested a way of managing it [ 5 ].

Advances in CLT have set the trends for future developments in different learning environments such as workplace-based learning, simulation, and games [ 15 ]. Most studies used the CLT principles in instructional design in simulation, virtual reality, and game settings in nursing education [ 1 , 16 , 17 , 18 ]. Yiin et al., (2023) indicated the multi-media interactive learning materials and an active learning mechanism reduced nursing students’ intrinsic and extrinsic cognitive load and encouraged the students to learn [ 19 ]. Takhdat et al., (2024) showed that mindfulness meditation practice optimizes cognitive load, and decreases the anxiety of nursing students in a simulation setting [ 20 ].

Clinical education in the workplace is defined as a main educational setting where students improve their competencies and prepare for their future careers. Sewell and colleagues (2019) in a BEME guide (Best Evidence in Medical Education guide) discussed cognitive load in workplace-based learning in the real environment [ 21 ]. The workplace-based learning in clinical education imposes high levels of cognitive load that negatively impact on learning of learners and their performances. Sewell et al. indicated the factors of, complex tasks, settings, and novice learners mostly predispose the students to high levels of cognitive load. They stated aspects of workplace environments contribute to extraneous load, and adversely impact capacity for engaging in tasks that enhance germane load and learning [ 15 ]. Further studies are recommended to understand the manner and the extent of the impact of cognitive load on different learning outcomes in various learning environments in systems of health professions education [ 1 , 16 , 17 ].

The present study aimed to test the relationship between the components of the Cognitive Load Theory (CLT) including memory, intrinsic and extraneous cognitive load in workplace-based learning, and decision-making skills of nursing students in clinical settings.

Materials and methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted in 2021–2023 at Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran. In the present study, the path analysis was used to predict a defined theoretical model that posits hypothesized linear relations among variables and decreases to the solution of one or more multiple regression analyses.

The present university has conducted a four-year nursing degree curriculum. The students have participated in workplace-based learning in the clinical setting from the second semester. They contributed to care processes as team members from the third semester of the academic course. In the present nursing curriculum, there is no reasoning and decision-making training course. The decision-making skills have been learned by the students in the process of workplace-based learning in the clinical environment. The stages of experiential learning, including observation, practice and repetition, feedback, and self-reflection, have been implemented in the nursing clinical education program. In clinical education courses, the students have used study guides nursing flowcharts, and clinical guidelines.

Participants

Undergraduate nursing students of the faculties affiliated with Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences participated in this study. The inclusion criteria were nursing students who had completed at least six months of apprenticeship courses in their field in the hospital. Students with working experience as health technicians ( Behvarz ) were excluded from the study. This exclusion criterion aims to control for potential confounding variables that could influence the study’s outcomes, such as previous professional experience impacting cognitive load assessments and decision-making skills [ 22 , 23 ].

The rule of thumb is to have at least 10–15 observations per parameter (i.e., 10–15 cases for each independent variable and the dependent variable) to have reliable estimates of the model parameters [ 24 ]. Thus, a total of 151 eligible students were randomly selected in this study.

Data collection

To conduct the examination, the researcher explained the objectives of the research, the instruments of data collection, the duration of the examinations, and the confidentiality of data. The participants were asked to perform the Wechsler computerized working memory test and fill the Questionnaires of Cognitive Load Inventory for Handoffs and Clinical Decision-making in a calm environment and away from disturbing side factors. The informed consent form was completed by the students.

Study tools

Working memory measurement tool: Wechsler’s computerized working memory test was used to evaluate working (active) memory [ 25 , 26 ]. In this test, two sections of forward and backward recall of digits are used to measure the memory span. The total working memory score is obtained from the sum of the scores of the two parts of forward and backward recall with a maximum score is 28. For the correct evaluation of the subject, the soft table is used for the desired ages. In this software, the score of memory span (auditory and visual) is also provided. This score represents the number of items memorized by the examinee.

The cognitive Load Inventory for Handoffs (CLIH) was compiled by Yang et al., (2016) [ 27 ] to assess the cognitive load of students in their clinical education. The questionnaire includes 9 questions in three domains of ICL, ECL, and GCL which is based on a 10-point Likert. The validity of the tool was confirmed in the present study. The qualitative content validity of the Persian version of the questionnaire was confirmed from the viewpoints of 15 experts. To determine content validity quantitatively, two indices “Content Validity Ratio (CVR)” and “Content Validity Index (CVI)” were used. The findings of the quantitative content validity assessment indicated that the CVR for all items was higher than the minimum acceptable value (= 0.49), and the CVI values of all items were above 0.79. According to the indices, all items were kept in the questionnaire. S-CVI/Ave was 0.94, which was desirable. The internal consistency of the tool was reported as Cronbach’s alpha coefficient = 0.86.

Clinical decision-making as a learning outcome of nursing students in clinical education was evaluated using the 24-item questionnaire designed by Lauri et al. (2001) which is based on a 5-point scale [ 12 ]. The reliability and validity were confirmed in the Karimi et al. study (2013) (Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of intrinsic consistency = 0.8) [ 28 ].

Data analysis

Demographic information of the participants (including gender, age, level of education, and the last externship/internship period of the students) was collected. Descriptive statistics (including frequency percentage, mean, and standard deviation) and analytical statistics (ANOVA) were used to investigate the variables. SPSS statistical software (Ver. 24) was used for data analysis.

This study employed path analysis as the primary statistical analysis method due to its ability to examine the relationships between multiple variables, including the direct and indirect effects of predictor variables on the outcome variable. Specifically, path analysis was used to investigate the relationships between memory, internal and external cognitive load, and decision-making skill, as well as the indirect effects of these variables on learning outcomes. Moreover, path analysis is suited for examining the relationships among the variables in this study due to the capability of path analysis to handle complex models and multiple relationships simultaneously. The use of path analysis was further justified by the need to examine the causal relationships between variables, as well as to account for measurement error and unexplained variance in the data. Path analysis allows for the estimation of standardized regression coefficients, which can be used to interpret the magnitude and direction of the relationships between variables.

In terms of model evaluation, this study employed several indices to assess the goodness-of-fit of the proposed model. The goodness-of-fit index (GFI) was also used to evaluate the model’s fit relative to a baseline model, with a value of 0.95 or higher indicating a good fit [ 29 ]. In addition, acceptable levels of indices of the path analysis include Adjusted Goodness-of-Fit Index (AGFI) > 0.8, Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) > 0.9, the Incremental Fit Index (IFI) > 0.8. Regarding the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) with a value of greater than 0.90 is very good fit, 0.80 to 0.89 is adequate but marginal fit, 0.60 to 0.79 is poor fit, a and lower than 0.60 very poor fit. Finally, the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) was used to evaluate the model’s fit to the data, with a value of 0.05 or less indicating a good fit [ 30 ]. These results indicate that the proposed model provided an adequate representation of the relationships among the variables studied. In the present study, AMOS 22 software was used to assess the fitness of this model.

In total, 151 nursing students participated in this study, 77 of them (51%) were women and 74 (49%) were men. The mean age of the participants was 21.97 ± 2.20. The demographic information of the participants is shown in Table 1 .