How to Write a Dissertation: Step-by-Step Guide

Contributing Writer

Editor & Writer

www.bestcolleges.com is an advertising-supported site. Featured or trusted partner programs and all school search, finder, or match results are for schools that compensate us. This compensation does not influence our school rankings, resource guides, or other editorially-independent information published on this site.

Turn Your Dreams Into Reality

Take our quiz and we'll do the homework for you! Compare your school matches and apply to your top choice today.

- Doctoral students write and defend dissertations to earn their degrees.

- Most dissertations range from 100-300 pages, depending on the field.

- Taking a step-by-step approach can help students write their dissertations.

Whether you're considering a doctoral program or you recently passed your comprehensive exams, you've probably wondered how to write a dissertation. Researching, writing, and defending a dissertation represents a major step in earning a doctorate.

But what is a dissertation exactly? A dissertation is an original work of scholarship that contributes to the field. Doctoral candidates often spend 1-3 years working on their dissertations. And many dissertations top 200 or more pages.

Starting the process on the right foot can help you complete a successful dissertation. Breaking down the process into steps may also make it easier to finish your dissertation.

How to Write a Dissertation in 12 Steps

A dissertation demonstrates mastery in a subject. But how do you write a dissertation? Here are 12 steps to successfully complete a dissertation.

Choose a Topic

It sounds like an easy step, but choosing a topic will play an enormous role in the success of your dissertation. In some fields, your dissertation advisor will recommend a topic. In other fields, you'll develop a topic on your own.

Read recent work in your field to identify areas for additional scholarship. Look for holes in the literature or questions that remain unanswered.

After coming up with a few areas for research or questions, carefully consider what's feasible with your resources. Talk to your faculty advisor about your ideas and incorporate their feedback.

Conduct Preliminary Research

Before starting a dissertation, you'll need to conduct research. Depending on your field, that might mean visiting archives, reviewing scholarly literature , or running lab tests.

Use your preliminary research to hone your question and topic. Take lots of notes, particularly on areas where you can expand your research.

Read Secondary Literature

A dissertation demonstrates your mastery of the field. That means you'll need to read a large amount of scholarship on your topic. Dissertations typically include a literature review section or chapter.

Create a list of books, articles, and other scholarly works early in the process, and continue to add to your list. Refer to the works cited to identify key literature. And take detailed notes to make the writing process easier.

Write a Research Proposal

In most doctoral programs, you'll need to write and defend a research proposal before starting your dissertation.

The length and format of your proposal depend on your field. In many fields, the proposal will run 10-20 pages and include a detailed discussion of the research topic, methodology, and secondary literature.

Your faculty advisor will provide valuable feedback on turning your proposal into a dissertation.

Research, Research, Research

Doctoral dissertations make an original contribution to the field, and your research will be the basis of that contribution.

The form your research takes will depend on your academic discipline. In computer science, you might analyze a complex dataset to understand machine learning. In English, you might read the unpublished papers of a poet or author. In psychology, you might design a study to test stress responses. And in education, you might create surveys to measure student experiences.

Work closely with your faculty advisor as you conduct research. Your advisor can often point you toward useful resources or recommend areas for further exploration.

Look for Dissertation Examples

Writing a dissertation can feel overwhelming. Most graduate students have written seminar papers or a master's thesis. But a dissertation is essentially like writing a book.

Looking at examples of dissertations can help you set realistic expectations and understand what your discipline wants in a successful dissertation. Ask your advisor if the department has recent dissertation examples. Or use a resource like ProQuest Dissertations to find examples.

Doctoral candidates read a lot of monographs and articles, but they often do not read dissertations. Reading polished scholarly work, particularly critical scholarship in your field, can give you an unrealistic standard for writing a dissertation.

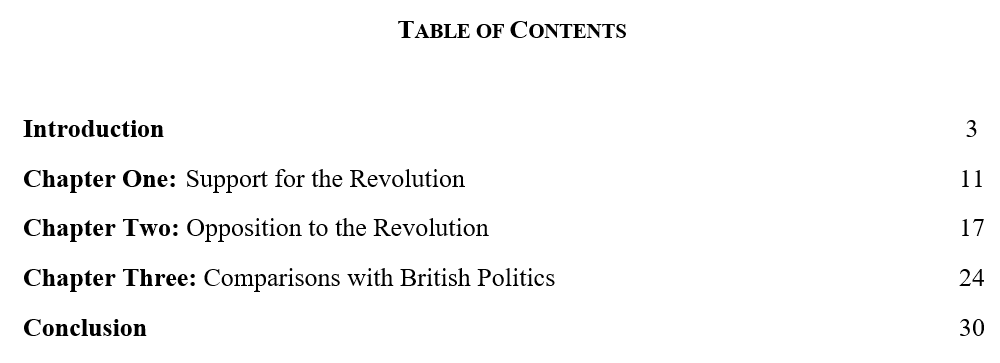

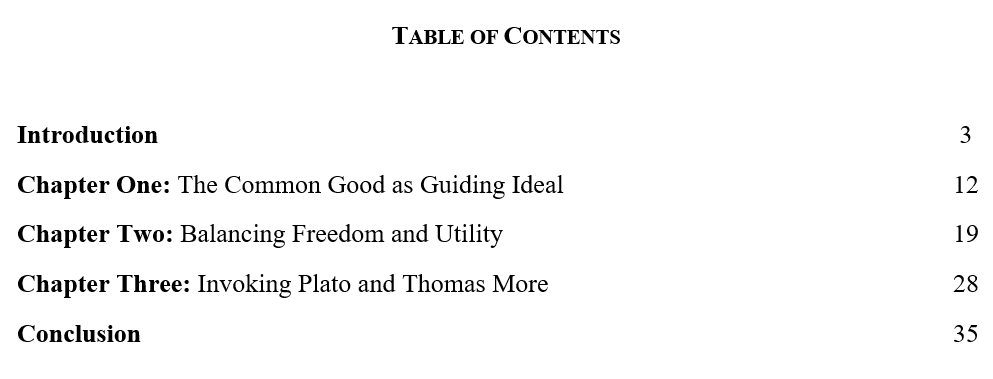

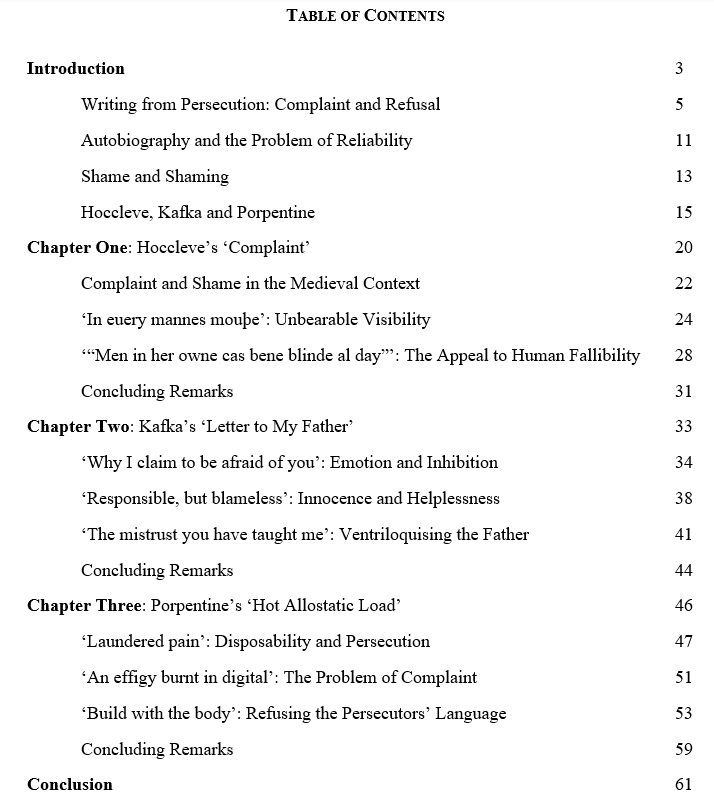

Write Your Body Chapters

By the time you sit down to write your dissertation, you've already accomplished a great deal. You've chosen a topic, defended your proposal, and conducted research. Now it's time to organize your work into chapters.

As with research, the format of your dissertation depends on your field. Your department will likely provide dissertation guidelines to structure your work. In many disciplines, dissertations include chapters on the literature review, methodology, and results. In other disciplines, each chapter functions like an article that builds to your overall argument.

Start with the chapter you feel most confident in writing. Expand on the literature review in your proposal to provide an overview of the field. Describe your research process and analyze the results.

Meet With Your Advisor

Throughout the dissertation process, you should meet regularly with your advisor. As you write chapters, send them to your advisor for feedback. Your advisor can help identify issues and suggest ways to strengthen your dissertation.

Staying in close communication with your advisor will also boost your confidence for your dissertation defense. Consider sharing material with other members of your committee as well.

Write Your Introduction and Conclusion

It seems counterintuitive, but it's a good idea to write your introduction and conclusion last . Your introduction should describe the scope of your project and your intervention in the field.

Many doctoral candidates find it useful to return to their dissertation proposal to write the introduction. If your project evolved significantly, you will need to reframe the introduction. Make sure you provide background information to set the scene for your dissertation. And preview your methodology, research aims, and results.

The conclusion is often the shortest section. In your conclusion, sum up what you've demonstrated, and explain how your dissertation contributes to the field.

Edit Your Draft

You've completed a draft of your dissertation. Now, it's time to edit that draft.

For some doctoral candidates, the editing process can feel more challenging than researching or writing the dissertation. Most dissertations run a minimum of 100-200 pages , with some hitting 300 pages or more.

When editing your dissertation, break it down chapter by chapter. Go beyond grammar and spelling to make sure you communicate clearly and efficiently. Identify repetitive areas and shore up weaknesses in your argument.

Incorporate Feedback

Writing a dissertation can feel very isolating. You're focused on one topic for months or years, and you're often working alone. But feedback will strengthen your dissertation.

You will receive feedback as you write your dissertation, both from your advisor and other committee members. In many departments, doctoral candidates also participate in peer review groups to provide feedback.

Outside readers will note confusing sections and recommend changes. Make sure you incorporate the feedback throughout the writing and editing process.

Defend Your Dissertation

Congratulations — you made it to the dissertation defense! Typically, your advisor will not let you schedule the defense unless they believe you will pass. So consider the defense a culmination of your dissertation process rather than a high-stakes examination.

The format of your defense depends on the department. In some fields, you'll present your research. In other fields, the defense will consist of an in-depth discussion with your committee.

Walk into your defense with confidence. You're now an expert in your topic. Answer questions concisely and address any weaknesses in your study. Once you pass the defense, you'll earn your doctorate.

Writing a dissertation isn't easy — only around 55,000 students earned a Ph.D. in 2020, according to the National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics. However, it is possible to successfully complete a dissertation by breaking down the process into smaller steps.

Frequently Asked Questions About Dissertations

What is a dissertation.

A dissertation is a substantial research project that contributes to your field of study. Graduate students write a dissertation to earn their doctorate.

The format and content of a dissertation vary widely depending on the academic discipline. Doctoral candidates work closely with their faculty advisor to complete and defend the dissertation, a process that typically takes 1-3 years.

How long is a dissertation?

The length of a dissertation varies by field. Harvard's graduate school says most dissertations fall between 100-300 pages .

Doctoral candidate Marcus Beck analyzed the length of University of Minnesota dissertations by discipline and found that history produces the longest dissertations, with an average of nearly 300 pages, while mathematics produces the shortest dissertations at just under 100 pages.

What's the difference between a dissertation vs. a thesis?

Dissertations and theses demonstrate academic mastery at different levels. In U.S. graduate education, master's students typically write theses, while doctoral students write dissertations. The terms are reversed in the British system.

In the U.S., a dissertation is longer, more in-depth, and based on more research than a thesis. Doctoral candidates write a dissertation as the culminating research project of their degree. Undergraduates and master's students may write shorter theses as part of their programs.

Explore More College Resources

How to write an effective thesis statement.

How to Write a Research Paper: 11-Step Guide

How to Write a History Essay, According to a History Professor

BestColleges.com is an advertising-supported site. Featured or trusted partner programs and all school search, finder, or match results are for schools that compensate us. This compensation does not influence our school rankings, resource guides, or other editorially-independent information published on this site.

Compare Your School Options

View the most relevant schools for your interests and compare them by tuition, programs, acceptance rate, and other factors important to finding your college home.

How To Write A Dissertation Or Thesis

8 straightforward steps to craft an a-grade dissertation.

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) Expert Reviewed By: Dr Eunice Rautenbach | June 2020

Writing a dissertation or thesis is not a simple task. It takes time, energy and a lot of will power to get you across the finish line. It’s not easy – but it doesn’t necessarily need to be a painful process. If you understand the big-picture process of how to write a dissertation or thesis, your research journey will be a lot smoother.

In this post, I’m going to outline the big-picture process of how to write a high-quality dissertation or thesis, without losing your mind along the way. If you’re just starting your research, this post is perfect for you. Alternatively, if you’ve already submitted your proposal, this article which covers how to structure a dissertation might be more helpful.

How To Write A Dissertation: 8 Steps

- Clearly understand what a dissertation (or thesis) is

- Find a unique and valuable research topic

- Craft a convincing research proposal

- Write up a strong introduction chapter

- Review the existing literature and compile a literature review

- Design a rigorous research strategy and undertake your own research

- Present the findings of your research

- Draw a conclusion and discuss the implications

Step 1: Understand exactly what a dissertation is

This probably sounds like a no-brainer, but all too often, students come to us for help with their research and the underlying issue is that they don’t fully understand what a dissertation (or thesis) actually is.

So, what is a dissertation?

At its simplest, a dissertation or thesis is a formal piece of research , reflecting the standard research process . But what is the standard research process, you ask? The research process involves 4 key steps:

- Ask a very specific, well-articulated question (s) (your research topic)

- See what other researchers have said about it (if they’ve already answered it)

- If they haven’t answered it adequately, undertake your own data collection and analysis in a scientifically rigorous fashion

- Answer your original question(s), based on your analysis findings

In short, the research process is simply about asking and answering questions in a systematic fashion . This probably sounds pretty obvious, but people often think they’ve done “research”, when in fact what they have done is:

- Started with a vague, poorly articulated question

- Not taken the time to see what research has already been done regarding the question

- Collected data and opinions that support their gut and undertaken a flimsy analysis

- Drawn a shaky conclusion, based on that analysis

If you want to see the perfect example of this in action, look out for the next Facebook post where someone claims they’ve done “research”… All too often, people consider reading a few blog posts to constitute research. Its no surprise then that what they end up with is an opinion piece, not research. Okay, okay – I’ll climb off my soapbox now.

The key takeaway here is that a dissertation (or thesis) is a formal piece of research, reflecting the research process. It’s not an opinion piece , nor a place to push your agenda or try to convince someone of your position. Writing a good dissertation involves asking a question and taking a systematic, rigorous approach to answering it.

If you understand this and are comfortable leaving your opinions or preconceived ideas at the door, you’re already off to a good start!

Step 2: Find a unique, valuable research topic

As we saw, the first step of the research process is to ask a specific, well-articulated question. In other words, you need to find a research topic that asks a specific question or set of questions (these are called research questions ). Sounds easy enough, right? All you’ve got to do is identify a question or two and you’ve got a winning research topic. Well, not quite…

A good dissertation or thesis topic has a few important attributes. Specifically, a solid research topic should be:

Let’s take a closer look at these:

Attribute #1: Clear

Your research topic needs to be crystal clear about what you’re planning to research, what you want to know, and within what context. There shouldn’t be any ambiguity or vagueness about what you’ll research.

Here’s an example of a clearly articulated research topic:

An analysis of consumer-based factors influencing organisational trust in British low-cost online equity brokerage firms.

As you can see in the example, its crystal clear what will be analysed (factors impacting organisational trust), amongst who (consumers) and in what context (British low-cost equity brokerage firms, based online).

Need a helping hand?

Attribute #2: Unique

Your research should be asking a question(s) that hasn’t been asked before, or that hasn’t been asked in a specific context (for example, in a specific country or industry).

For example, sticking organisational trust topic above, it’s quite likely that organisational trust factors in the UK have been investigated before, but the context (online low-cost equity brokerages) could make this research unique. Therefore, the context makes this research original.

One caveat when using context as the basis for originality – you need to have a good reason to suspect that your findings in this context might be different from the existing research – otherwise, there’s no reason to warrant researching it.

Attribute #3: Important

Simply asking a unique or original question is not enough – the question needs to create value. In other words, successfully answering your research questions should provide some value to the field of research or the industry. You can’t research something just to satisfy your curiosity. It needs to make some form of contribution either to research or industry.

For example, researching the factors influencing consumer trust would create value by enabling businesses to tailor their operations and marketing to leverage factors that promote trust. In other words, it would have a clear benefit to industry.

So, how do you go about finding a unique and valuable research topic? We explain that in detail in this video post – How To Find A Research Topic . Yeah, we’ve got you covered 😊

Step 3: Write a convincing research proposal

Once you’ve pinned down a high-quality research topic, the next step is to convince your university to let you research it. No matter how awesome you think your topic is, it still needs to get the rubber stamp before you can move forward with your research. The research proposal is the tool you’ll use for this job.

So, what’s in a research proposal?

The main “job” of a research proposal is to convince your university, advisor or committee that your research topic is worthy of approval. But convince them of what? Well, this varies from university to university, but generally, they want to see that:

- You have a clearly articulated, unique and important topic (this might sound familiar…)

- You’ve done some initial reading of the existing literature relevant to your topic (i.e. a literature review)

- You have a provisional plan in terms of how you will collect data and analyse it (i.e. a methodology)

At the proposal stage, it’s (generally) not expected that you’ve extensively reviewed the existing literature , but you will need to show that you’ve done enough reading to identify a clear gap for original (unique) research. Similarly, they generally don’t expect that you have a rock-solid research methodology mapped out, but you should have an idea of whether you’ll be undertaking qualitative or quantitative analysis , and how you’ll collect your data (we’ll discuss this in more detail later).

Long story short – don’t stress about having every detail of your research meticulously thought out at the proposal stage – this will develop as you progress through your research. However, you do need to show that you’ve “done your homework” and that your research is worthy of approval .

So, how do you go about crafting a high-quality, convincing proposal? We cover that in detail in this video post – How To Write A Top-Class Research Proposal . We’ve also got a video walkthrough of two proposal examples here .

Step 4: Craft a strong introduction chapter

Once your proposal’s been approved, its time to get writing your actual dissertation or thesis! The good news is that if you put the time into crafting a high-quality proposal, you’ve already got a head start on your first three chapters – introduction, literature review and methodology – as you can use your proposal as the basis for these.

Handy sidenote – our free dissertation & thesis template is a great way to speed up your dissertation writing journey.

What’s the introduction chapter all about?

The purpose of the introduction chapter is to set the scene for your research (dare I say, to introduce it…) so that the reader understands what you’ll be researching and why it’s important. In other words, it covers the same ground as the research proposal in that it justifies your research topic.

What goes into the introduction chapter?

This can vary slightly between universities and degrees, but generally, the introduction chapter will include the following:

- A brief background to the study, explaining the overall area of research

- A problem statement , explaining what the problem is with the current state of research (in other words, where the knowledge gap exists)

- Your research questions – in other words, the specific questions your study will seek to answer (based on the knowledge gap)

- The significance of your study – in other words, why it’s important and how its findings will be useful in the world

As you can see, this all about explaining the “what” and the “why” of your research (as opposed to the “how”). So, your introduction chapter is basically the salesman of your study, “selling” your research to the first-time reader and (hopefully) getting them interested to read more.

How do I write the introduction chapter, you ask? We cover that in detail in this post .

Step 5: Undertake an in-depth literature review

As I mentioned earlier, you’ll need to do some initial review of the literature in Steps 2 and 3 to find your research gap and craft a convincing research proposal – but that’s just scratching the surface. Once you reach the literature review stage of your dissertation or thesis, you need to dig a lot deeper into the existing research and write up a comprehensive literature review chapter.

What’s the literature review all about?

There are two main stages in the literature review process:

Literature Review Step 1: Reading up

The first stage is for you to deep dive into the existing literature (journal articles, textbook chapters, industry reports, etc) to gain an in-depth understanding of the current state of research regarding your topic. While you don’t need to read every single article, you do need to ensure that you cover all literature that is related to your core research questions, and create a comprehensive catalogue of that literature , which you’ll use in the next step.

Reading and digesting all the relevant literature is a time consuming and intellectually demanding process. Many students underestimate just how much work goes into this step, so make sure that you allocate a good amount of time for this when planning out your research. Thankfully, there are ways to fast track the process – be sure to check out this article covering how to read journal articles quickly .

Literature Review Step 2: Writing up

Once you’ve worked through the literature and digested it all, you’ll need to write up your literature review chapter. Many students make the mistake of thinking that the literature review chapter is simply a summary of what other researchers have said. While this is partly true, a literature review is much more than just a summary. To pull off a good literature review chapter, you’ll need to achieve at least 3 things:

- You need to synthesise the existing research , not just summarise it. In other words, you need to show how different pieces of theory fit together, what’s agreed on by researchers, what’s not.

- You need to highlight a research gap that your research is going to fill. In other words, you’ve got to outline the problem so that your research topic can provide a solution.

- You need to use the existing research to inform your methodology and approach to your own research design. For example, you might use questions or Likert scales from previous studies in your your own survey design .

As you can see, a good literature review is more than just a summary of the published research. It’s the foundation on which your own research is built, so it deserves a lot of love and attention. Take the time to craft a comprehensive literature review with a suitable structure .

But, how do I actually write the literature review chapter, you ask? We cover that in detail in this video post .

Step 6: Carry out your own research

Once you’ve completed your literature review and have a sound understanding of the existing research, its time to develop your own research (finally!). You’ll design this research specifically so that you can find the answers to your unique research question.

There are two steps here – designing your research strategy and executing on it:

1 – Design your research strategy

The first step is to design your research strategy and craft a methodology chapter . I won’t get into the technicalities of the methodology chapter here, but in simple terms, this chapter is about explaining the “how” of your research. If you recall, the introduction and literature review chapters discussed the “what” and the “why”, so it makes sense that the next point to cover is the “how” –that’s what the methodology chapter is all about.

In this section, you’ll need to make firm decisions about your research design. This includes things like:

- Your research philosophy (e.g. positivism or interpretivism )

- Your overall methodology (e.g. qualitative , quantitative or mixed methods)

- Your data collection strategy (e.g. interviews , focus groups, surveys)

- Your data analysis strategy (e.g. content analysis , correlation analysis, regression)

If these words have got your head spinning, don’t worry! We’ll explain these in plain language in other posts. It’s not essential that you understand the intricacies of research design (yet!). The key takeaway here is that you’ll need to make decisions about how you’ll design your own research, and you’ll need to describe (and justify) your decisions in your methodology chapter.

2 – Execute: Collect and analyse your data

Once you’ve worked out your research design, you’ll put it into action and start collecting your data. This might mean undertaking interviews, hosting an online survey or any other data collection method. Data collection can take quite a bit of time (especially if you host in-person interviews), so be sure to factor sufficient time into your project plan for this. Oftentimes, things don’t go 100% to plan (for example, you don’t get as many survey responses as you hoped for), so bake a little extra time into your budget here.

Once you’ve collected your data, you’ll need to do some data preparation before you can sink your teeth into the analysis. For example:

- If you carry out interviews or focus groups, you’ll need to transcribe your audio data to text (i.e. a Word document).

- If you collect quantitative survey data, you’ll need to clean up your data and get it into the right format for whichever analysis software you use (for example, SPSS, R or STATA).

Once you’ve completed your data prep, you’ll undertake your analysis, using the techniques that you described in your methodology. Depending on what you find in your analysis, you might also do some additional forms of analysis that you hadn’t planned for. For example, you might see something in the data that raises new questions or that requires clarification with further analysis.

The type(s) of analysis that you’ll use depend entirely on the nature of your research and your research questions. For example:

- If your research if exploratory in nature, you’ll often use qualitative analysis techniques .

- If your research is confirmatory in nature, you’ll often use quantitative analysis techniques

- If your research involves a mix of both, you might use a mixed methods approach

Again, if these words have got your head spinning, don’t worry! We’ll explain these concepts and techniques in other posts. The key takeaway is simply that there’s no “one size fits all” for research design and methodology – it all depends on your topic, your research questions and your data. So, don’t be surprised if your study colleagues take a completely different approach to yours.

Step 7: Present your findings

Once you’ve completed your analysis, it’s time to present your findings (finally!). In a dissertation or thesis, you’ll typically present your findings in two chapters – the results chapter and the discussion chapter .

What’s the difference between the results chapter and the discussion chapter?

While these two chapters are similar, the results chapter generally just presents the processed data neatly and clearly without interpretation, while the discussion chapter explains the story the data are telling – in other words, it provides your interpretation of the results.

For example, if you were researching the factors that influence consumer trust, you might have used a quantitative approach to identify the relationship between potential factors (e.g. perceived integrity and competence of the organisation) and consumer trust. In this case:

- Your results chapter would just present the results of the statistical tests. For example, correlation results or differences between groups. In other words, the processed numbers.

- Your discussion chapter would explain what the numbers mean in relation to your research question(s). For example, Factor 1 has a weak relationship with consumer trust, while Factor 2 has a strong relationship.

Depending on the university and degree, these two chapters (results and discussion) are sometimes merged into one , so be sure to check with your institution what their preference is. Regardless of the chapter structure, this section is about presenting the findings of your research in a clear, easy to understand fashion.

Importantly, your discussion here needs to link back to your research questions (which you outlined in the introduction or literature review chapter). In other words, it needs to answer the key questions you asked (or at least attempt to answer them).

For example, if we look at the sample research topic:

In this case, the discussion section would clearly outline which factors seem to have a noteworthy influence on organisational trust. By doing so, they are answering the overarching question and fulfilling the purpose of the research .

For more information about the results chapter , check out this post for qualitative studies and this post for quantitative studies .

Step 8: The Final Step Draw a conclusion and discuss the implications

Last but not least, you’ll need to wrap up your research with the conclusion chapter . In this chapter, you’ll bring your research full circle by highlighting the key findings of your study and explaining what the implications of these findings are.

What exactly are key findings? The key findings are those findings which directly relate to your original research questions and overall research objectives (which you discussed in your introduction chapter). The implications, on the other hand, explain what your findings mean for industry, or for research in your area.

Sticking with the consumer trust topic example, the conclusion might look something like this:

Key findings

This study set out to identify which factors influence consumer-based trust in British low-cost online equity brokerage firms. The results suggest that the following factors have a large impact on consumer trust:

While the following factors have a very limited impact on consumer trust:

Notably, within the 25-30 age groups, Factors E had a noticeably larger impact, which may be explained by…

Implications

The findings having noteworthy implications for British low-cost online equity brokers. Specifically:

The large impact of Factors X and Y implies that brokers need to consider….

The limited impact of Factor E implies that brokers need to…

As you can see, the conclusion chapter is basically explaining the “what” (what your study found) and the “so what?” (what the findings mean for the industry or research). This brings the study full circle and closes off the document.

Let’s recap – how to write a dissertation or thesis

You’re still with me? Impressive! I know that this post was a long one, but hopefully you’ve learnt a thing or two about how to write a dissertation or thesis, and are now better equipped to start your own research.

To recap, the 8 steps to writing a quality dissertation (or thesis) are as follows:

- Understand what a dissertation (or thesis) is – a research project that follows the research process.

- Find a unique (original) and important research topic

- Craft a convincing dissertation or thesis research proposal

- Write a clear, compelling introduction chapter

- Undertake a thorough review of the existing research and write up a literature review

- Undertake your own research

- Present and interpret your findings

Once you’ve wrapped up the core chapters, all that’s typically left is the abstract , reference list and appendices. As always, be sure to check with your university if they have any additional requirements in terms of structure or content.

Psst... there’s more!

This post was based on one of our popular Research Bootcamps . If you're working on a research project, you'll definitely want to check this out ...

You Might Also Like:

20 Comments

thankfull >>>this is very useful

Thank you, it was really helpful

unquestionably, this amazing simplified way of teaching. Really , I couldn’t find in the literature words that fully explicit my great thanks to you. However, I could only say thanks a-lot.

Great to hear that – thanks for the feedback. Good luck writing your dissertation/thesis.

This is the most comprehensive explanation of how to write a dissertation. Many thanks for sharing it free of charge.

Very rich presentation. Thank you

Thanks Derek Jansen|GRADCOACH, I find it very useful guide to arrange my activities and proceed to research!

Thank you so much for such a marvelous teaching .I am so convinced that am going to write a comprehensive and a distinct masters dissertation

It is an amazing comprehensive explanation

This was straightforward. Thank you!

I can say that your explanations are simple and enlightening – understanding what you have done here is easy for me. Could you write more about the different types of research methods specific to the three methodologies: quan, qual and MM. I look forward to interacting with this website more in the future.

Thanks for the feedback and suggestions 🙂

Hello, your write ups is quite educative. However, l have challenges in going about my research questions which is below; *Building the enablers of organisational growth through effective governance and purposeful leadership.*

Very educating.

Just listening to the name of the dissertation makes the student nervous. As writing a top-quality dissertation is a difficult task as it is a lengthy topic, requires a lot of research and understanding and is usually around 10,000 to 15000 words. Sometimes due to studies, unbalanced workload or lack of research and writing skill students look for dissertation submission from professional writers.

Thank you 💕😊 very much. I was confused but your comprehensive explanation has cleared my doubts of ever presenting a good thesis. Thank you.

thank you so much, that was so useful

Hi. Where is the excel spread sheet ark?

could you please help me look at your thesis paper to enable me to do the portion that has to do with the specification

my topic is “the impact of domestic revenue mobilization.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

- +44 (0) 207 391 9032

Recent Posts

- How to Write a Research Paper Like a Pro

- Academic Integrity vs. Academic Dishonesty: Understanding the Key Differences

- How to Use AI to Enhance Your Thesis

- Guide to Structuring Your Narrative Essay for Success

- How to Hook Your Readers with a Compelling Topic Sentence

- Is a Thesis Writing Format Easy? A Comprehensive Guide to Thesis Writing

- The Complete Guide to Copy Editing: Roles, Rates, Skills, and Process

- How to Write a Paragraph: Successful Essay Writing Strategies

- Everything You Should Know About Academic Writing: Types, Importance, and Structure

- Concise Writing: Tips, Importance, and Exercises for a Clear Writing Style

- Academic News

- Custom Essays

- Dissertation Writing

- Essay Marking

- Essay Writing

- Essay Writing Companies

- Model Essays

- Model Exam Answers

- Oxbridge Essays Updates

- PhD Writing

- Significant Academics

- Student News

- Study Skills

- University Applications

- University Essays

- University Life

- Writing Tips

11 quick fixes to get your thesis back on track

(Last updated: 21 December 2023)

Since 2006, Oxbridge Essays has been the UK’s leading paid essay-writing and dissertation service

We have helped 10,000s of undergraduate, Masters and PhD students to maximise their grades in essays, dissertations, model-exam answers, applications and other materials. If you would like a free chat about your project with one of our UK staff, then please just reach out on one of the methods below.

Struggles with a dissertation can begin at any phase in the process. From the earliest points in which you are just trying to generate a viable idea, to the end where there might be time-table or advisor issues.

If you feel like you're struggling, you are not alone.

For as much as the situation might feel unique to you, the truth of the matter is that it's not. You are one of hundreds of thousands of students who will have endured, and eventually triumphed, over a centuries-old process.

So, rest assured that any struggles or difficulties are completely and totally normal, and not likely to be insurmountable. Your goal to ace your thesis is certainly achievable.

There is one book that you should have on your shelf and should have read. Umberto Eco’s 'How to Write a Thesis' (MIT Press, 2015) , was originally published in the late 70’s for his Italian students, and most of his analysis and advice rings true today.

It is, in essence, a guide on how to be productive and produce a large body of research writing, and it contains lots of really sound and useful advice.

"Help! I've only just started my dissertation and already I'm stuck."

For as weighty and profound as the final product might appear to be, the essence of a dissertation is quite simple: it is an answer to a question.

Dissertation writers often stumble over the same block. They try to find an answer without first asking themselves what question they are actually answering.

One of the greatest advances in physics was a result of a question so simple, it is almost child-like: ‘what would light look like if I ran alongside it?’. For those of you interested, have a read about Einstein’s thought experiment on chasing a light beam .

For many, a problem arises with a dissertation because after becoming accustomed, over several years of earlier education, to ‘spitting back’ and regurgitating information, you suddenly and largely – if not entirely – feel expected to say something original.

Try flipping your thesis statement on its head and see it as a question; what is a thesis statement but a question that has been turned into a declaration?

So just to recap, the first step in the early stages of your dissertation really should be identifying a research question.

In fact, for some advisors this is the first thing they want to see. Not, ‘what do you want to talk about?’ or, ‘what is your thesis statement?’ but, ‘what is your research question? What are you trying to answer?’.

What to do if you don't know where to start

One of the easiest ways to get started is by simply reading .

A professor we know often recommended this as a simple way of getting ideas flowing. He would have his students read about a dozen of the most recent articles pertaining to a particular topic.

Not broad topics, mind you, like twelve recent articles on Shakespeare or globalisation, but more focused, like ‘Shakespeare and travel’ or ‘globalisation and education’.

What is particularly useful about reading in this way is that most articles are part of some thread of academic discussion, and so will mention and account for previous research in some way.

By reading such articles, you’ll gain an idea of what has been and is being discussed in your area of interest and what the critical issues are. Usually, after just a handful of articles, some rough ideas and focus start to emerge.

What to do if you don’t have anything to say

Maybe you have found a general idea, that ‘question’, but you are still left without something to talk about. At this point, you just don’t have the data, or the material, to work up a dissertation. The answer is quite simple: you need to do research .

Have you ever considered what research is? Why the ‘re-‘? Why isn’t it just called ‘search’? This step requires you to look over and over and over again, for patterns, themes, arguments… You are looking at other people’s work to see what they have wrong and right, which will allow for plenty of discussion.

Follow your instincts

Not to make the process sound overly mystical, but at this point in your academic career there should be a gut response to what you read.

A noteworthy idea or a passage should make your academic antennae sit up and pay attention, without you necessarily even knowing why. Perhaps you are simply struck by the notion that what you just read was interesting, for some reason. This ‘reason’ is what we mean by ‘instincts’.

In fact, studies have shown that you can be right up to 90% of the time when trusting your gut .

We know many, many academics and the process is very much the same for them – something for some reason or other just catches their attention. As you go through your research – your reading, reading, and reading – you should always note these things that draw your eye.

Write (don't type) everything down

Now seems like a great time to tell you that here at Oxbridge Essays HQ, we are HUGE fans of the index card.

We’re not joking when we say that a few books or printed articles and a half-stack of index cards for jotting down notes and ideas is all you need to get going.

Index cards are easier to sort and move around than a notebook, and easier to lay out than a computer screen. In fact, outside of research and materials-gathering for which internet access is vital, for the first stages of your dissertation writing the humble index card might be all you need. After you’ve created a good-sized stack of index cards, a pattern (though maybe not the pattern) should start to develop.

And for the sake of all that is holy and dear, write everything down ! Do not trust your memory with even the smallest detail because there is little worse than spending hours trying to remember where you saw something that could have been helpful, and never finding it.

"Argh! I'm mid-way through my dissertation and suddenly, I've run out of steam."

There is a famous phrase; you probably know it: ‘Never a day without a line’.

You should never go a day without writing something, or rewriting something.

If the notion of working every day on your dissertation fills you with dread, consider this: a dissertation, as we just suggested; is merely a form of work. In life, there are few good reasons to not go to work, and so should there be few that mean you do not work on your dissertation.

Try using methods like The Pomodoro Technique to help you work more productively.

Some days will always be better than others, and some days you will feel more or less enthusiastic. But don’t trick yourself into thinking that your ‘feeling’ towards your work on any particular day may make what you produce better or worse.

Ultimately, the quality of your work should stem from the good habits that you have cultivated. Make working on your dissertation every day one of your good habits.

What to do if you feel like you've reached a dead end

This may not be what you want to hear, but even if you are struggling, you should work every day including weekends.

And try not to book any holidays that will mean you’ll be away from your computer – or tempted to be – whilst you’re doing your dissertation. It’s likely there will be at least one time when you’ll be forced to take time off (illness, for example, or a family bereavement), so if you work every day, it’ll help you stay on track should anything like this come up.

And work begets work . It’s far easier to pick up where you last left off if you only left off yesterday. But trying to do so when you haven’t worked for a week, or even a few days, can be a hard task.

Some people do complain of writer’s block, but this just doesn’t fly with us. First, you aren’t writing Ulysses . Second, and more important, there is always something to do. Have you read everything in your field? Updated your bibliography? Read over your notes?

Granted, sometimes you can get stuck. There may be times when paragraphs or sections just do not cooperate. This is not uncommon and it can take days or weeks to figure out what the problem is.

It can help, when you come to a dead-end in this way, to think about two things: is it necessary and, if so, is it right? If it’s neither necessary or right, it can and probably should be deleted.

You’ll have to get used to, particularly in the early stages of your dissertation, binning sections of work that just don’t fit or do your dissertation justice. Don’t be afraid to be ruthless; just quietly move the offending passage into a scraps file (do not delete it entirely) and move on. Maybe it will make more sense later.

If it helps, one academic who contributed to this blog post had, for their 100,000-word dissertation, a file of 40,000 useless scraps.

What to do if you are falling behind

Not to finger wag, but if you had planned well and worked every day, this statement should never be one you relate to.

But, sadly, sometimes it happens. Time can be remarkably fragile and unexpected life events can ruin what probably looked good and doable on paper. Setbacks do not mean you failed, nor do they mean you will fail. It might mean, however, that you have to take a different approach.

Any time you have a serious issue that jeopardises your ability to complete your thesis, the first place to go is your advisor to discuss options. There are also mentoring services on many campuses.

If you have fallen behind, you need to honestly assess how bad the situation is. Is this something that can be resolved by, say, putting in a few extra hours each day? Adding a half-day on the weekends? Neither of these situations are uncommon. Or will you perhaps require an extension? If the amount of time is serious enough to warrant taking it to an administrative level, be honest and frank with both yourself and the person you speak to.

"If you have fallen behind, you need to honestly assess how bad the situation is. Be honest and frank with both yourself and the person you speak to."

One of the most practical ways to avoid falling behind is not to let some of the smaller things get away from you. Reading, note-taking, data collection and bibliography building can all be tedious tasks left for another day.

But sitting down to read thousands of pages in one marathon go is unproductive. The best advice is still ‘read a little, write a little, every single day’.

The math favours you here. Reading a single article or a few chapters every day builds a nice familiarity with your field over the course of a year. And writing 500-1000 words every day yields enough content for two to three dissertations.

In fact, it has been shown that professional academics who write just that many words each day are more productive than colleagues who attempt marathon (and sometimes panicky and stressful) sessions.

"I'm so close to finishing my dissertation, but I'm having last-minute worries."

What to do if you think your idea is terrible.

If you work on something long enough, doubts are going to start creeping in. The further in you are, the less of an objective view you will be able to take on your work.

Some perspective can be helpful here.

There are two fairly common rules of thumb for dissertations and theses among academics. The first is that you are finished when your work is more right than wrong. The second is that it does not have to be perfect, but it does have to be finished.

You can waste time obsessing about how awful your idea is, or you can just finish the bloody thing. Examiners commonly disagree on the quality of your work, its merit and its value, and make suggestions for improvement. This will happen no matter how brilliant your idea might be.

It also helps to keep in mind that you are very unlikely to write anything with which examiners do not disagree.

What to do if your idea is no longer viable

This is the stuff of nightmares for dissertation writers. You spend oodles of time and effort coming up with a brilliant idea. Your advisor and/or committee are supportive and excited for you. You are certain that nothing of what you are talking about has been essayed by anyone else.

And yet, there is a lurking terror. A terror that you are going to be scooped and find research that is exactly like what you are doing. We speak from experience here, and we know people who have had this happen.

The scenario usually plays out in one of two ways.

More often than not you'll find that you and your new nemesis have taken two completely different approaches. This is actually great news for you. Now you have a discussion that you can incorporate into your work. You have something in which you can find and comment on positive aspects as well as shortcomings.

In the less likely event that you have, in fact, rewritten the work of another researcher then you will need to account for that work and perhaps try to develop another line of approach.

The most important point to bear in mind is that the vast majority of academic work exists in dialogue with other works. So it is often a good thing that someone else is researching the same problem you are. Indeed, you might even consider reaching out and contacting that person just to hone your ideas or solicit feedback. In general, if you do this politely and professionally, you will be warmly received.

What to do if you don’t have enough words

Everyone writes differently. Some people are amazingly concise writers. They can elegantly shoehorn into a single sentence what balloons into a paragraph for another. Most dissertation requirements have a set range.

Notably, some advisors can adjust that and add or subtract. The aforementioned academic who contributed to this blog post – his doctoral supervisor tacked on 20,000 words just because he felt it was necessary. The academic still disagrees with it to this day.

Our point is that the word limit is not arbitrarily set. It is generally agreed that this is the amount of words required to discuss a topic fully. Thus, if you're short of words then unfortunately you haven't discussed your topic as fully as you should have.

If this is the case, you need to look for where your gaps have settled in. The best way to do this will be to solicit outside readers – two or three, one of whom should be your supervisor .

But you don’t want to drop a stack of papers in front of someone and say, ‘can you read this and tell me what to do?’. The better approach will be to assemble a very thorough outline of 3-5 pages that shows the structure and ask if they will look this over. We can assure you, the response will be much more positive and their response time markedly shorter.

Another approach to increasing word count is to generate an indirectly related discussion and add it as an appendix.

What to do if you have too many words

Congratulations! You are probably in the minority, but cutting words is often much easier than finding them.

Still, the acceptable range rule stands for an excess of words just as it does for too few.

If you find yourself in this position, then quite likely you have academic bloat . It’s quite a common trap for dissertation writers as they develop what they perceive to be an academic style and tone in their writing.

But before you simply jettison whole sections of your thesis to bring the word count down, we would especially recommend, for later stage thesis and dissertation writing, a wonderful little book by Richard Lanham called 'Revising Prose' (Pearson, 2006).

When it was first introduced it was a welcome sensation. It’s a short and clear-cut guide to cutting the bloat and bull out of academic writing and making your prose more precise and refined at the sentence and paragraph level. This might sound overly simplistic but don’t sniff at the notion – the book is a potent little text and we wish it were read by every dissertation and thesis writer.

What to do if your supervisor isn’t helpful

This is a problem that can actually present itself at any stage of the dissertation or thesis writing process. It can be one of the most frustrating matters with which you might have to contend.

One thing that you must understand is that the university wants and needs to see you complete your project.

That is not to say that they’ll be pleased with shoddy work. But the more graduates, the more vital the department appears, and the more funding they can request and be allocated.

So there is a vested interest in your success, even if there are points at which it doesn’t feel this way. At some universities, one of the ways in which these conflicts are avoided is through a general contract of expectations. This is done at the outset and lays out the basics of the working relationship (when and how often you will meet, for instance). Hopefully you will have formally or informally handled this early and can identify where a fault might lay.

It can also help to arrange at the outset for a co-supervisor. This person can be invaluable. Often a co-supervisor will practically take over a project, especially if the co-supervisor is young and eager to build credibility and experience as a supervisor (the best sort, really).

Read more about how to make your relationship with your dissertation supervisor productive, rewarding, and enjoyable.

If you have an unproductive working relationship with your supervisor, consider seriously the nature and expectations of it from both sides.

Not to shift the fault to you, but sometimes supervisees can have unrealistic expectations of their supervisor. The truth is that very few supervisors have the time or inclination to pal around with their supervisees, drinking cognac into the wee hours and talking about high enlightened matters.

The reality is that the better and more capable students are often regarded to be the ones who come in, write their projects, and move on. Supervisors have other obligations (e.g. teaching, their own research, other students writing projects). They expect supervisees to be able to work independently and not need too much hand-holding.

There is, nevertheless, tremendous anxiety that surrounds one’s relationship with their supervisor. This is largely due to the extremely imbalanced power relationship. Your supervisor is, after all, someone on whom you will depend for letters, vetting, and generally someone on whom you will rely professionally.

It is not a relationship you want to sour. But you should also consider that the relationship has to be professional and nothing should be taken personally. Think about what you need from your advisor, not what you want . If your professional needs are not being met than you should consider mediation, provided you have discussed these needs with your advisor and they remain unmet.

A final thought...

Throughout the months or years that you are preparing your dissertation or thesis you should keep in mind two helpful words: don’t panic.

It is extremely unlikely that anything you are experiencing hasn’t been experienced by someone else. Or that it presents an obstacle with which your supervisors or the university is unfamiliar.

There are few obstacles that are insurmountable, so try to remember this if you ever feel panic rising. Remember to keep your advisor in the loop and deal with any problems that arise promptly; don’t let them fester.

Also, the more prepared you are to begin with the easier it will be to deal with problems and frustrations down the road.

Advice for successfully writing a dissertation

How to write a dissertation literature review

Dissertation findings and discussion sections

- dissertation help

- dissertation tips

- dissertation writing

- dissertation writing service

- student worries

- study skills

Writing Services

- Essay Plans

- Critical Reviews

- Literature Reviews

- Presentations

- Dissertation Title Creation

- Dissertation Proposals

- Dissertation Chapters

- PhD Proposals

- Journal Publication

- CV Writing Service

- Business Proofreading Services

Editing Services

- Proofreading Service

- Editing Service

- Academic Editing Service

Additional Services

- Marking Services

- Consultation Calls

- Personal Statements

- Tutoring Services

Our Company

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Become a Writer

Terms & Policies

- Fair Use Policy

- Policy for Students in England

- Privacy Policy

- Terms & Conditions

- [email protected]

- Contact Form

Payment Methods

Cryptocurrency payments.

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Thesis and Dissertation: Getting Started

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

The resources in this section are designed to provide guidance for the first steps of the thesis or dissertation writing process. They offer tools to support the planning and managing of your project, including writing out your weekly schedule, outlining your goals, and organzing the various working elements of your project.

Weekly Goals Sheet (a.k.a. Life Map) [Word Doc]

This editable handout provides a place for you to fill in available time blocks on a weekly chart that will help you visualize the amount of time you have available to write. By using this chart, you will be able to work your writing goals into your schedule and put these goals into perspective with your day-to-day plans and responsibilities each week. This handout also contains a formula to help you determine the minimum number of pages you would need to write per day in order to complete your writing on time.

Setting a Production Schedule (Word Doc)

This editable handout can help you make sense of the various steps involved in the production of your thesis or dissertation and determine how long each step might take. A large part of this process involves (1) seeking out the most accurate and up-to-date information regarding specific document formatting requirements, (2) understanding research protocol limitations, (3) making note of deadlines, and (4) understanding your personal writing habits.

Creating a Roadmap (PDF)

Part of organizing your writing involves having a clear sense of how the different working parts relate to one another. Creating a roadmap for your dissertation early on can help you determine what the final document will include and how all the pieces are connected. This resource offers guidance on several approaches to creating a roadmap, including creating lists, maps, nut-shells, visuals, and different methods for outlining. It is important to remember that you can create more than one roadmap (or more than one type of roadmap) depending on how the different approaches discussed here meet your needs.

Dissertation Strategies

What this handout is about.

This handout suggests strategies for developing healthy writing habits during your dissertation journey. These habits can help you maintain your writing momentum, overcome anxiety and procrastination, and foster wellbeing during one of the most challenging times in graduate school.

Tackling a giant project

Because dissertations are, of course, big projects, it’s no surprise that planning, writing, and revising one can pose some challenges! It can help to think of your dissertation as an expanded version of a long essay: at the end of the day, it is simply another piece of writing. You’ve written your way this far into your degree, so you’ve got the skills! You’ll develop a great deal of expertise on your topic, but you may still be a novice with this genre and writing at this length. Remember to give yourself some grace throughout the project. As you begin, it’s helpful to consider two overarching strategies throughout the process.

First, take stock of how you learn and your own writing processes. What strategies have worked and have not worked for you? Why? What kind of learner and writer are you? Capitalize on what’s working and experiment with new strategies when something’s not working. Keep in mind that trying out new strategies can take some trial-and-error, and it’s okay if a new strategy that you try doesn’t work for you. Consider why it may not have been the best for you, and use that reflection to consider other strategies that might be helpful to you.

Second, break the project into manageable chunks. At every stage of the process, try to identify specific tasks, set small, feasible goals, and have clear, concrete strategies for achieving each goal. Small victories can help you establish and maintain the momentum you need to keep yourself going.

Below, we discuss some possible strategies to keep you moving forward in the dissertation process.

Pre-dissertation planning strategies

Get familiar with the Graduate School’s Thesis and Dissertation Resources .

Create a template that’s properly formatted. The Grad School offers workshops on formatting in Word for PC and formatting in Word for Mac . There are online templates for LaTeX users, but if you use a template, save your work where you can recover it if the template has corrruption issues.

Learn how to use a citation-manager and a synthesis matrix to keep track of all of your source information.

Skim other dissertations from your department, program, and advisor. Enlist the help of a librarian or ask your advisor for a list of recent graduates whose work you can look up. Seeing what other people have done to earn their PhD can make the project much less abstract and daunting. A concrete sense of expectations will help you envision and plan. When you know what you’ll be doing, try to find a dissertation from your department that is similar enough that you can use it as a reference model when you run into concerns about formatting, structure, level of detail, etc.

Think carefully about your committee . Ideally, you’ll be able to select a group of people who work well with you and with each other. Consult with your advisor about who might be good collaborators for your project and who might not be the best fit. Consider what classes you’ve taken and how you “vibe” with those professors or those you’ve met outside of class. Try to learn what you can about how they’ve worked with other students. Ask about feedback style, turnaround time, level of involvement, etc., and imagine how that would work for you.

Sketch out a sensible drafting order for your project. Be open to writing chapters in “the wrong order” if it makes sense to start somewhere other than the beginning. You could begin with the section that seems easiest for you to write to gain momentum.

Design a productivity alliance with your advisor . Talk with them about potential projects and a reasonable timeline. Discuss how you’ll work together to keep your work moving forward. You might discuss having a standing meeting to discuss ideas or drafts or issues (bi-weekly? monthly?), your advisor’s preferences for drafts (rough? polished?), your preferences for what you’d like feedback on (early or late drafts?), reasonable turnaround time for feedback (a week? two?), and anything else you can think of to enter the collaboration mindfully.

Design a productivity alliance with your colleagues . Dissertation writing can be lonely, but writing with friends, meeting for updates over your beverage of choice, and scheduling non-working social times can help you maintain healthy energy. See our tips on accountability strategies for ideas to support each other.

Productivity strategies

Write when you’re most productive. When do you have the most energy? Focus? Creativity? When are you most able to concentrate, either because of your body rhythms or because there are fewer demands on your time? Once you determine the hours that are most productive for you (you may need to experiment at first), try to schedule those hours for dissertation work. See the collection of time management tools and planning calendars on the Learning Center’s Tips & Tools page to help you think through the possibilities. If at all possible, plan your work schedule, errands and chores so that you reserve your productive hours for the dissertation.

Put your writing time firmly on your calendar . Guard your writing time diligently. You’ll probably be invited to do other things during your productive writing times, but do your absolute best to say no and to offer alternatives. No one would hold it against you if you said no because you’re teaching a class at that time—and you wouldn’t feel guilty about saying no. Cultivating the same hard, guilt-free boundaries around your writing time will allow you preserve the time you need to get this thing done!

Develop habits that foster balance . You’ll have to work very hard to get this dissertation finished, but you can do that without sacrificing your physical, mental, and emotional wellbeing. Think about how you can structure your work hours most efficiently so that you have time for a healthy non-work life. It can be something as small as limiting the time you spend chatting with fellow students to a few minutes instead of treating the office or lab as a space for extensive socializing. Also see above for protecting your time.

Write in spaces where you can be productive. Figure out where you work well and plan to be there during your dissertation work hours. Do you get more done on campus or at home? Do you prefer quiet and solitude, like in a library carrel? Do you prefer the buzz of background noise, like in a coffee shop? Are you aware of the UNC Libraries’ list of places to study ? If you get “stuck,” don’t be afraid to try a change of scenery. The variety may be just enough to get your brain going again.

Work where you feel comfortable . Wherever you work, make sure you have whatever lighting, furniture, and accessories you need to keep your posture and health in good order. The University Health and Safety office offers guidelines for healthy computer work . You’re more likely to spend time working in a space that doesn’t physically hurt you. Also consider how you could make your work space as inviting as possible. Some people find that it helps to have pictures of family and friends on their desk—sort of a silent “cheering section.” Some people work well with neutral colors around them, and others prefer bright colors that perk up the space. Some people like to put inspirational quotations in their workspace or encouraging notes from friends and family. You might try reconfiguring your work space to find a décor that helps you be productive.

Elicit helpful feedback from various people at various stages . You might be tempted to keep your writing to yourself until you think it’s brilliant, but you can lower the stakes tremendously if you make eliciting feedback a regular part of your writing process. Your friends can feel like a safer audience for ideas or drafts in their early stages. Someone outside your department may provide interesting perspectives from their discipline that spark your own thinking. See this handout on getting feedback for productive moments for feedback, the value of different kinds of feedback providers, and strategies for eliciting what’s most helpful to you. Make this a recurring part of your writing process. Schedule it to help you hit deadlines.

Change the writing task . When you don’t feel like writing, you can do something different or you can do something differently. Make a list of all the little things you need to do for a given section of the dissertation, no matter how small. Choose a task based on your energy level. Work on Grad School requirements: reformat margins, work on bibliography, and all that. Work on your acknowledgements. Remember all the people who have helped you and the great ideas they’ve helped you develop. You may feel more like working afterward. Write a part of your dissertation as a letter or email to a good friend who would care. Sometimes setting aside the academic prose and just writing it to a buddy can be liberating and help you get the ideas out there. You can make it sound smart later. Free-write about why you’re stuck, and perhaps even about how sick and tired you are of your dissertation/advisor/committee/etc. Venting can sometimes get you past the emotions of writer’s block and move you toward creative solutions. Open a separate document and write your thoughts on various things you’ve read. These may or may note be coherent, connected ideas, and they may or may not make it into your dissertation. They’re just notes that allow you to think things through and/or note what you want to revisit later, so it’s perfectly fine to have mistakes, weird organization, etc. Just let your mind wander on paper.

Develop habits that foster productivity and may help you develop a productive writing model for post-dissertation writing . Since dissertations are very long projects, cultivating habits that will help support your work is important. You might check out Helen Sword’s work on behavioral, artisanal, social, and emotional habits to help you get a sense of where you are in your current habits. You might try developing “rituals” of work that could help you get more done. Lighting incense, brewing a pot of a particular kind of tea, pulling out a favorite pen, and other ritualistic behaviors can signal your brain that “it is time to get down to business.” You can critically think about your work methods—not only about what you like to do, but also what actually helps you be productive. You may LOVE to listen to your favorite band while you write, for example, but if you wind up playing air guitar half the time instead of writing, it isn’t a habit worth keeping.

The point is, figure out what works for you and try to do it consistently. Your productive habits will reinforce themselves over time. If you find yourself in a situation, however, that doesn’t match your preferences, don’t let it stop you from working on your dissertation. Try to be flexible and open to experimenting. You might find some new favorites!

Motivational strategies

Schedule a regular activity with other people that involves your dissertation. Set up a coworking date with your accountability buddies so you can sit and write together. Organize a chapter swap. Make regular appointments with your advisor. Whatever you do, make sure it’s something that you’ll feel good about showing up for–and will make you feel good about showing up for others.

Try writing in sprints . Many writers have discovered that the “Pomodoro technique” (writing for 25 minutes and taking a 5 minute break) boosts their productivity by helping them set small writing goals, focus intently for short periods, and give their brains frequent rests. See how one dissertation writer describes it in this blog post on the Pomodoro technique .

Quit while you’re ahead . Sometimes it helps to stop for the day when you’re on a roll. If you’ve got a great idea that you’re developing and you know where you want to go next, write “Next, I want to introduce x, y, and z and explain how they’re related—they all have the same characteristics of 1 and 2, and that clinches my theory of Q.” Then save the file and turn off the computer, or put down the notepad. When you come back tomorrow, you will already know what to say next–and all that will be left is to say it. Hopefully, the momentum will carry you forward.

Write your dissertation in single-space . When you need a boost, double space it and be impressed with how many pages you’ve written.

Set feasible goals–and celebrate the achievements! Setting and achieving smaller, more reasonable goals ( SMART goals ) gives you success, and that success can motivate you to focus on the next small step…and the next one.

Give yourself rewards along the way . When you meet a writing goal, reward yourself with something you normally wouldn’t have or do–this can be anything that will make you feel good about your accomplishment.

Make the act of writing be its own reward . For example, if you love a particular coffee drink from your favorite shop, save it as a special drink to enjoy during your writing time.

Try giving yourself “pre-wards” —positive experiences that help you feel refreshed and recharged for the next time you write. You don’t have to “earn” these with prior work, but you do have to commit to doing the work afterward.

Commit to doing something you don’t want to do if you don’t achieve your goal. Some people find themselves motivated to work harder when there’s a negative incentive. What would you most like to avoid? Watching a movie you hate? Donating to a cause you don’t support? Whatever it is, how can you ensure enforcement? Who can help you stay accountable?

Affective strategies

Build your confidence . It is not uncommon to feel “imposter phenomenon” during the course of writing your dissertation. If you start to feel this way, it can help to take a few minutes to remember every success you’ve had along the way. You’ve earned your place, and people have confidence in you for good reasons. It’s also helpful to remember that every one of the brilliant people around you is experiencing the same lack of confidence because you’re all in a new context with new tasks and new expectations. You’re not supposed to have it all figured out. You’re supposed to have uncertainties and questions and things to learn. Remember that they wouldn’t have accepted you to the program if they weren’t confident that you’d succeed. See our self-scripting handout for strategies to turn these affirmations into a self-script that you repeat whenever you’re experiencing doubts or other negative thoughts. You can do it!

Appreciate your successes . Not meeting a goal isn’t a failure–and it certainly doesn’t make you a failure. It’s an opportunity to figure out why you didn’t meet the goal. It might simply be that the goal wasn’t achievable in the first place. See the SMART goal handout and think through what you can adjust. Even if you meant to write 1500 words, focus on the success of writing 250 or 500 words that you didn’t have before.

Remember your “why.” There are a whole host of reasons why someone might decide to pursue a PhD, both personally and professionally. Reflecting on what is motivating to you can rekindle your sense of purpose and direction.

Get outside support . Sometimes it can be really helpful to get an outside perspective on your work and anxieties as a way of grounding yourself. Participating in groups like the Dissertation Support group through CAPS and the Dissertation Boot Camp can help you see that you’re not alone in the challenges. You might also choose to form your own writing support group with colleagues inside or outside your department.

Understand and manage your procrastination . When you’re writing a long dissertation, it can be easy to procrastinate! For instance, you might put off writing because the house “isn’t clean enough” or because you’re not in the right “space” (mentally or physically) to write, so you put off writing until the house is cleaned and everything is in its right place. You may have other ways of procrastinating. It can be helpful to be self-aware of when you’re procrastinating and to consider why you are procrastinating. It may be that you’re anxious about writing the perfect draft, for example, in which case you might consider: how can I focus on writing something that just makes progress as opposed to being “perfect”? There are lots of different ways of managing procrastination; one way is to make a schedule of all the things you already have to do (when you absolutely can’t write) to help you visualize those chunks of time when you can. See this handout on procrastination for more strategies and tools for managing procrastination.

Your topic, your advisor, and your committee: Making them work for you

By the time you’ve reached this stage, you have probably already defended a dissertation proposal, chosen an advisor, and begun working with a committee. Sometimes, however, those three elements can prove to be major external sources of frustration. So how can you manage them to help yourself be as productive as possible?

Managing your topic