Advertisement

Review: systematic review of effectiveness of art psychotherapy in children with mental health disorders

- Review Article

- Open access

- Published: 06 July 2021

- Volume 191 , pages 1369–1383, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Irene Braito ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3695-6464 1 , 2 ,

- Tara Rudd 3 ,

- Dicle Buyuktaskin ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4679-3846 1 , 4 ,

- Mohammad Ahmed 1 ,

- Caoimhe Glancy 1 &

- Aisling Mulligan ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7708-1177 3 , 5

13k Accesses

12 Citations

2 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Art therapy and art psychotherapy are often offered in Child and Adolescent Mental Health services (CAMHS). We aimed to review the evidence regarding art therapy and art psychotherapy in children attending mental health services. We searched PubMed, Web of Science, and EBSCO (CINHAL®Complete) following PRISMA guidelines, using the search terms (“creative therapy” OR “art therapy”) AND (child* OR adolescent OR teen*). We excluded review articles, articles which included adults, articles which were not written in English and articles without outcome measures. We identified 17 articles which are included in our review synthesis. We described these in two groups—ten articles regarding the treatment of children with a psychiatric diagnosis and seven regarding the treatment of children with psychiatric symptoms, but no formal diagnosis. The studies varied in terms of the type of art therapy/psychotherapy delivered, underlying conditions and outcome measures. Many were case studies/case series or small quasi-experimental studies; there were few randomised controlled trials and no replication studies. However, there was some evidence that art therapy or art psychotherapy may benefit children who have experienced trauma or who have post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms. There is extensive literature regarding art therapy/psychotherapy in children but limited empirical papers regarding its use in children attending mental health services. There is some evidence that art therapy or art psychotherapy may benefit children who have experienced trauma. Further research is required, and it may be beneficial if studies could be replicated in different locations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Art Therapy Interventions for Syrian Child and Adolescent Refugees: Enhancing Mental Well-being and Resilience

Art and evidence: balancing the discussion on arts- and evidence- based practices with traumatized children.

Art Therapy

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) often offer art therapy, as well as many other therapeutic approaches; we wished to review the literature regarding art therapy in CAMHS. Previous systematic reviews of art therapy were not specifically focused on the effectiveness in children [ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 ] or were focused on the use of art therapy in children with physical conditions rather than with mental health conditions [ 6 ]. The use of art or doodling as a communication tool in CAMHS is long established—Donald Winnicott famously used “the Squiggle Game” to break boundaries between a patient and professional to narrate a story through a simple squiggle [ 7 ]. Art is particularly useful to build a rapport with a child who presents with an issue that is too difficult to verbalise or if the child does not have words to express a difficulty. The term art therapy was coined by the artist Adrian Hill in 1942 following admission to a sanatorium for the treatment of tuberculosis, where artwork eased his suffering. “Art psychotherapy” expands on this concept by incorporating psychoanalytic processes, seeking to access the unconscious. Jung influenced the development of art psychotherapy as a means to access the unconscious and stated that “by painting himself he gives shape to himself” [ 8 ]. Art psychotherapy often focuses on externalising the problem, reflecting on it and analysing it which may then give way to seeing a resolution.

The UK Joint Commissioning Panel for Mental Health 2013 recommends that psychotherapists and creative therapists are part of the CAMHS teams [ 9 ]. There is a specific UK recommendation that art therapy may be used in the treatment of children and young people recovering from psychosis, particularly those with negative symptoms [ 10 ], but no similar recommendation in the Irish HSE National Clinical Programme for Early Intervention in Psychosis [ 11 ]. There is less clarity about the use of art therapy in the treatment of depression in young people—arts therapies were previously recommended [ 12 ], but more recent NICE guidelines appear to have dropped this advice, though the recommendation for psychodynamic psychotherapy has remained [ 13 ]. Art therapy is often offered to treat traumatised children, but we note that current NICE guidelines on the management of PTSD do not include a recommendation for art therapy [ 14 ]. The Irish document “Vision for Change” did not include a recommendation regarding art psychotherapy or creative therapies [ 15 ]. Similarly, the document “Sharing the Vision” does not make any recommendation regarding creative or art therapies, though it recommends psychotherapy for adults and recommends arts activities as part of social prescribing for adults [ 16 ]. Meanwhile, it is not uncommon for there to be an art therapist in CAMHS inpatient units, working with those with the highest mental healthcare needs. We wished to find out more about the evidence for, or indeed against, the use of art therapy in CAMHS. We performed a systematic review which aimed to clarify if art psychotherapy is effective for use in children with mental health disorders. This review aimed to address the following questions: (1) Is art therapy/psychotherapy an effective treatment for children with mental health disorders? (2) What are the various methods of art therapy or art psychotherapy which have been used to treat children with mental health disorders and how do they differ in terms of (i) setting and duration, (ii) procedure of the sessions, and (iii) art activities details?

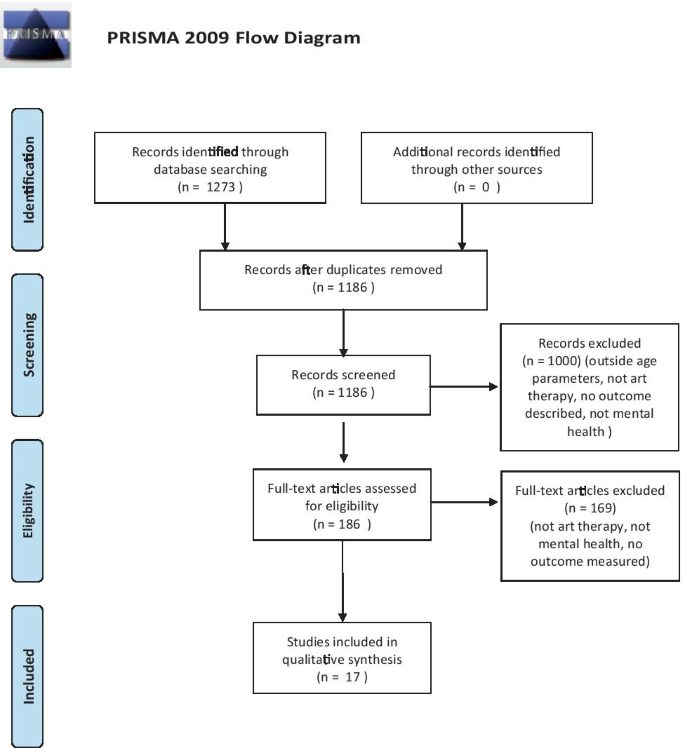

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews (PRISMA) statement for systematic reviews was followed. Searches and analysis were conducted between September 2016 and April 2020 using the following databases: PubMed, Web of Science and EBSCO (CINHAL®Complete). The following “medical subject terms” were utilized for searches: (“creative therapy” OR “art therapy”) AND (child* OR adolescent OR teen*). Review publications were excluded. Studies in the English language meeting the following inclusion criteria were selected: (i) use of art therapy/art psychotherapy, (ii) psychiatric disorder/diagnosis and/or mood disturbances and/or psychological symptoms, (iii) human participants aged 0–17 years inclusive. Articles investigating the efficiency of art therapy in children with medical conditions were included only if the measured outcome related to psychological well-being/symptoms. Exclusion criteria included: (i) application of therapies which do not involve art activities, (ii) application of a combination of therapies without individual results for art therapy, (iii) not clinical studies (review, meta-analysis, reports, others), (iv) studies which focused on the artwork itself/art therapy procedure and did not measure and publish any clinical outcomes, (v) absence of any pre psychiatric symptoms or comorbidity in the participant sample prior to art intervention. All articles were screened for inclusion by the authors (MA, TR, IB, AM, DB), unblinded to manuscript authorship.

Data extraction

The authors (IB, TR, AM, MA, DB) extracted all data independently (unblinded). Data were extracted and recorded in three tables with specific information from each study on (i) the study details, (ii) art therapy details and outcome measures and (iii) art therapy results. The following specific study details were extracted: author/journal, country, year of publication, study type (i.e. study design), study aims, study setting, participant details (number, age and gender), disease/disorder studied and inclusion criteria and exclusion criteria of the study. The following details were extracted regarding the art therapy provided and outcome measures : type of art therapy provided (individual or group therapy), the art therapy procedure and/or techniques used, the art therapy setting, therapy duration (including frequency and duration of each art therapy session), the type of outcome measure used, the investigated domains, the time points (for outcome measures) and the presence or absence of pre-/post-test statistical analysis. Finally, we extracted specific information on the art therapy results , including therapy group results, control group results, the number and percentage of who completed therapy, whether or not a pre-/post-test statistical difference was found and the general outcome of each study. Following the extraction of all data, studies included were divided into two groups: (1) children with psychiatric disorder diagnosis and (2) children with psychiatric symptoms. Finally, the QUADAS-2 tool was used to assess the risk of bias for each study, and a summary of the risk of bias for all data was calculated [ 17 ]. The QUADAS-2 is designed to assess and record selection bias, performance bias, detection bias, attrition bias, reporting bias and any other bias [ 17 ].

Study inclusion and assessment

A total of 1273 articles were initially identified (Fig. 1 ). After repeats and duplicates were removed, 1186 possible articles were identified and screened for inclusion/exclusion according to the title and abstract, which resulted in 1000 articles being excluded. The remaining 186 full articles were retrieved and full text considered. Following review of the full text, 70 articles were selected and further analysed. Fifty-three of them did not meet our criteria for review. Reasons for exclusion were grouped into four main categories: (1) not art therapy [ n = 2]; (2) not mental health [ n = 5]; (3) no outcome measured [ n = 18]; (4) other reasons (i.e. descriptive texts, full article not available) [ n = 28]. In conclusion, there were 17 articles remaining that met the full inclusion criteria, and further descriptive analysis was performed on these 17 studies. All the considered articles were produced in the twenty-first century, between 2001 and 2020, most in the USA (60%), followed by Canada (30%) and Italy (10%). The characteristics of studies included in our final synthesis are reported in Tables 1 and 2 .

PRISMA 2009 flow diagram

Participant characteristics

Participants in the 17 studies ranged from 2 to 17 years old inclusive. In ten articles, children with an established psychiatric diagnosis were included (Group 1, see Table 1 ). The type of psychiatric disorders as (i) PTSD, (ii) mood disorders (bipolar affective disorder, depressive disorders, anxiety disorder), (iii) self-harm behaviour, (iv) attachment disorder, (v) personality disorder and (vi) adjustment disorder. In seven articles, children with psychiatric symptoms were enrolled, usually referred by practitioners and school counsellors (Group 2, see Table 2 ). Participants had a wide variety of conditions including (i) symptoms of depression, anxiety, low mood, dysthymic features; (ii) attention and concentration disorder symptoms; (iii) socialisation problems and (iv) self-concept and self-image difficulties. Some children had medical conditions such as leukaemia requiring painful procedures, or glaucoma, cancer, seizures, acute surgery; others had experienced adversity such as parental divorce, physical, emotional and/or sexual abuse or had developed dangerous and promiscuous social habits (drugs, prostitution and gang involvement).

Study design: children with an established psychiatric diagnosis (Table 1 )

A summary of the ten studies on art therapy in children with a psychiatric diagnosis can be seen in Table 1 , with further information about each study. There are just two randomised controlled in this category, both treating PTSD in children [ 18 , 19 ]. Chapman et al. [ 18 ] provided individual art therapy to young children who had experienced trauma and assessed symptom response using the PTSD-I assessment of symptoms 1 week after injury and 1 month after hospital admission [ 18 ]. Their study included 85 children; 31 children received individual art therapy, 27 children received treatment as usual and 27 children did not meet criteria for PTSD on the initial PTSD-I assessment [ 18 ]. The art therapy group had a reduction in acute stress symptoms, but there was no significant difference in PTSD scores [ 18 ]. The second randomised controlled trial provided trauma-focused group art therapy in an inpatient setting and showed a significant reduction in PTSD symptoms in adolescents who attended art therapy in comparison to a control group who attended arts-and-crafts. However, this study had a high drop-out rate, with 142 patients referred to the study and just 29 patients who completed the study [ 19 ].

The remaining studies regarding art therapy or art psychotherapy in children with psychiatric disorders are case studies, case series or quasi experimental studies, most with less than five participants. All these studies reported positive effects of art therapy; we did not find any published negative studies. We can summarise that the studies differed greatly in the type of therapy delivered, in the setting (group or individual therapy) and in the types of disorders treated (Table 1 ).

Forms of art therapy intervention and assessment (Table 1 )

The various modalities and duration of art therapy described in the ten studies with children with psychiatric diagnoses are summarised in Table 1 . The treatment of PTSD was described in two studies, but each described a different art therapy protocol, and the studies varied in terms of setting and duration [ 18 , 19 ]. The Trauma Focused Art Therapy (TF-ART) study described 16 weekly in-patient group sessions [ 19 ], whereas the Chapman Art Therapy Treatment Intervention (CATTI) is a short-term individual therapy, lasting 1 h at the bedside of hospital inpatients [ 18 ]. Despite the differences, the methods have some common aspects. Both therapy methods focused on helping the individual express a narrative of his/her life story, supporting the individual to reflect on trauma-related experiences and to describe coping responses. Relaxation techniques were used, such as kinaesthetic activities [ 18 ] and “feelings check-ins” [ 19 ]. In the TF-ART protocol, each participant completed at least 13 collages or drawings and compiled in a hand-made book to describe his/her “life story” [ 19 ]. The use of art therapy in a traumatised child has also been described in a single case study [ 20 ].

Group art therapy has been described in the treatment of adolescent personality disorder, in an intervention where adolescents met weekly in two separate periods of 18 sessions over 6 months, with each session lasting 90 min, facilitated by a psychotherapist [ 21 ]. Sessions consisted of a short group conversation regarding events/issues during the previous week followed by a brief relaxing activity (e.g. listening to music), a period of art-making and an opportunity to explain their work, guided by the psychotherapist.

A long course of art psychotherapy over 3 years with a vulnerable female adolescent who presented with self-harm and later disclosed being a victim of a sexual assault has been described [ 22 ]. The young person described an “enemy” inside her which she had overcome in her testimony to her improvement, which was included in the published case study [ 22 ]. The approach of “art as therapy” has been described with children with bipolar disorder and other potential comorbidities, such as Asperger syndrome and attention deficit disorder, using the “naming the enemy” and “naming the friend” approaches [ 23 ].

The concept of the “transitional object”—a coping device for periods of separation in the mother–child dyad during infancy—has been considered in art therapy [ 24 ]. It was proposed that “transitional objects” could be used as bridging objects between a scary reality and the weak inner-self. Children brought their transitional objects to therapy sessions, and the therapy process aimed to detach the participant from his/her transitional object, giving him/her the strength to face life situations with his/her own capabilities [ 24 ].

Two studies of art therapy in children with adjustment disorders were included in our systematic review [ 25 , 26 ]. Children attended two or three video-recorded sessions and were encouraged to use art materials to explore daily life events. The child and therapist then watched the video-recorded session and participated in a semi-structured interview that employed video-stimulated recall. The therapy aimed to transport the participant to a comfortable imaginary world, giving the child the possibility to create powerful, strong characters in his/her story, thus enhancing the ability to cope with life’s challenges [ 25 , 26 ].

Outcome measures and statistical analysis (Table 1 )

Three articles on psychiatric disorders evaluated potential changes in outcome using an objective measure [ 18 , 19 , 22 ]. Two studies used the “The University of California at Los Angeles Children’s PTSD Index” (UCLA PTSD-I), which is a 20-item self-report tool [ 18 , 19 ]. Statistical differences were evaluated by calculating the mean percentage change [ 18 ] and the ANOVA [ 19 ]. The 12-item “MacKenzie’s Group Climate Questionnaire” was used to measure the outcome of group art therapy in adolescents with personality disorder, and a significant reduction in conflict in the group was found [ 21 ]. However, the sample size was small, and there was no control group [ 21 ]. Many studies did not use highly recognised measures of outcome but relied instead on a comprehensive description of outcome or change after art therapy/psychotherapy, in case studies or case series [ 20 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 ].

Study design: children with psychiatric symptoms (Table 2 )

We included seven studies in our review synthesis where art therapy or art psychotherapy was used as an intervention for psychiatric symptoms—many of these studies occurred in paediatric hospitals, where children were being treated for other conditions. Two of these studies were non-randomised controlled trials, one of which was waitlist controlled [ 28 , 29 ], and the other five were quasi-experimental studies [ 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 ].

Forms of intervention and assessment (Table 2 )

Three articles described art therapy in paediatric hospital patients but varied in terms of therapy and underlying condition [ 28 , 29 , 33 ]. The effectiveness of art therapy on self-esteem and symptoms of depression in children with glaucoma has been investigated; a number of sensory-stimulating art materials were introduced during six individual 1-h sessions [ 33 ]. Short-term or single individual art therapy sessions have also been used in hospital aiming to improve quality of life [ 28 , 29 ]. Art therapy has been provided to children with leukaemia; the children transformed unused socks into puppets called “healing sock creatures” [ 29 ]. Short-term art therapy prior to painful procedures, such as lumbar puncture or bone marrow aspiration, has also been described, using “visual imagination” and “medical play” with age-appropriate explanations about the procedure, with a cloth doll and medical instruments [ 28 ].

The remaining articles described the provision of art therapy to vulnerable patients, where the therapy aimed to increase self-confidence or address worries. Two studies focused on female self-esteem and self-concept, both using group activities [ 31 , 32 ]. Hartz and Thick [ 32 ] compared two different art therapy protocols: art psychotherapy, which employed a brief psychoeducational presentation and encouraged abstraction, symbolization and verbalization and an art as therapy approach, which highlighted design potentials, technique and the creative problem-solving process, trying to evoke artistic experimentation and accomplishment rather than different strengths and aspects of personality [ 32 ]. Participants completed a known questionnaire about self-esteem as well as a study-specific questionnaire.

Coholic and Eys [ 34 ] described the use of a 12-week arts-based mindfulness group programme with vulnerable children referred by mental health or child welfare services, with a combination of group work and individual sessions [ 34 ]. Children were given tasks which included the “thought jar” (filling an empty glass jar with water and various-shaped and coloured beads representing thoughts and feelings), the “me as a tree” activity, during which the participant drew him/herself as a tree, enabling the participant to introduce him/herself, the “emotion listen and draw” activity which provided the opportunity to draw/paint feelings while listening to five different songs and the “bad day better” activity which involved painting what a “bad day” looked like, and then to decorate it to turn it into a “good day”. The research included quantitative analysis and qualitative assessment using self-report Piers-Harris Children’s Self-Concept Scale and the Resiliency Scales for Children and Adolescents [ 37 , 38 ].

Kearns [ 30 ] described a single case study of art therapy with a child with a sensory integration difficulty, comparing teacher-reported behaviour patterns after art therapy sessions using kinaesthetic stimulation and visual stimulation with behaviour after 12 control sessions of non-art therapy; a greater improvement was reported with art therapy [ 30 ].

Outcome measures and statistical analysis (Table 2 )

Most of the studies on art therapy in children with psychiatric symptoms (but not confirmed disorders) used widely accepted outcome measures [ 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 ] (Table 2 ), such as self-report measurements including the 27-item symptom-orientated Children’s Depression Inventory or the Tennessee Self Concept Scale: Short Form [ 33 , 35 , 36 ]. The 60-item Piers-Harris Children’s Self-Concept Scale (2nd edition) and the Resiliency Scales for Children and Adolescents (RSCA) were used in a study on vulnerable children [ 34 , 37 , 38 ]. The Piers-Harris Children’s Self-Concept Scale is a widely used self-report measure of psychological health and self-concept in children and teens and consists of three global self-report scales presented in a 5-point Likert-type scale: sense of mastery (20 items), sense of relatedness (24 items) and emotional reactivity (20 items) [ 37 ]. A modified version of the Daley and Lecroy’s Go Grrrls Questionnaire was administered at group intake and follow-up, to rank various self-concept items including body image and self-esteem along a four-point ordinal scale in group therapy with young females [ 31 , 39 ].

Some researchers created their own outcome measures [ 28 , 29 , 30 , 33 ]. One study group created a mood questionnaire for young children—this was administered by a research assistant to patients before and after each therapy session, in their small wait-list controlled study [ 29 ]. Another group evaluated classroom performance using an observational system rated by the teacher for each 30-min block of time every day during the study [ 30 ]. The classroom study also used the “person picking an apple from a tree” (PPAT) drawing task—this was the only measurement tool in the studies we reviewed which assessed the features of the artworks themselves [ 30 , 40 ]. Pre- and post-test drawings were evaluated for evidence of changes in various qualities over the course of the research period [ 30 ].

Hartz and Thick [ 32 ] used both the 45-items Self-Perception Profile for Adolescents (SPPA) [ 41 ] which is widely used and considered reliable, as well as the Hartz Art Therapy Self-Esteem Questionnaire (Hartz AT-SEQ) [ 32 ], which is a 20-question post-treatment questionnaire designed by the author, to understand how specific aspects of art therapy treatment affect self-esteem in a quasi-experimental study with group art therapy. Four of the seven articles performed statistical analysis of the data collected, using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test [ 31 ], Fisher’s t [ 32 ], MANOVA [ 34 ], and two-tailed Student’s t test [ 29 ].

Assessment of bias

The QUADAS-2 assessment of bias for each study included in our systematic review synthesis can be seen in Table 3 , with a summary of the results of the QUADAS-2 assessment for all included studies in our review in Table 4 . Studies marked in green had a low risk of bias; those marked in red had a high risk of bias while those in yellow had an unclear risk of bias. Just two studies were found to have a low risk of bias [ 19 , 29 ].

We found extensive literature regarding the use of art therapy in children with mental health difficulties ( N = 1273), with a large number of descriptive qualitative studies and cases studies, but a limited number of quantitative studies which we could include in our review synthesis ( N = 17). The predominance of descriptive studies is not surprising considering that the field of art therapy and art psychotherapy has developed from the descriptive writings of Freud, Jung, Winnicott and others, and for many years, academic psychotherapy focused on detailed case descriptions rather than quantitative outcome studies. The numerous descriptive and qualitative publications generally described positive changes in participants undergoing art therapy, which may represent publication bias. Our aim was however to describe the quantitative evidence regarding the use of art therapy or art psychotherapy in children and adolescents with mental health difficulties, and we found a limited number of studies to include in our review synthesis. There were just two randomised controlled trials, no replication studies and insufficient information to allow for a meta-analysis. However, the articles in our review synthesis suggested that art therapy may have a positive outcome in various groups of patients, especially if the therapy lasts at least 8 weeks.

There is some evidence from controlled trials to support the use of art therapy in children who have experienced trauma [ 18 , 19 ]. It should be noted that art therapy or art psychotherapy was delivered as individual sessions in most of the studies in our review, especially for children with a psychiatric diagnosis. A group approach to art therapy was used in some studies with vulnerable children such as children in need, female adolescents with self-esteem issues and female offenders [ 22 , 31 , 34 ]. However, the studies on group art therapy or psychotherapy are quasi-experimental studies of limited size, and it would be useful if larger, more robust studies such as randomised controlled trials could study the efficacy of group art therapy or group art psychotherapy.

Many of the studies included in our review synthesis ranked low in the Cochrane Risk of Bias criteria, with a high risk of bias. Our review synthesis highlights the heterogeneity of the studies—various methods of individual or group art therapy were delivered, with some studies delivering psychoanalytic-type interventions while others delivered interventions resembling cognitive behaviour therapy, delivered via art. The literature also showed a general lack of standardisation with regard to the duration of art therapy and outcome measures used. Despite this, the authors of many of the studies described common themes and hypothesised about the value of art therapy or art psychotherapy in improving self-esteem, communication and integration. The interventions often encouraged the child to re-enact or to process trauma, and the authors described improved integration, and therapeutic change or transformation of the young person. It appears that there were varied interventions in the studies in the review synthesis but that many studies had theoretical similarities.

Strengths and limitations

We used clearly defined aims and followed PRISMA guidelines to perform this systematic review. However, we did not incorporate unpublished studies into our review and did not examine trial websites. By following strict exclusion criteria, we excluded studies on art psychotherapy and mental health where one or more participant commenced treatment before his/her eighteenth birthday and completed after the eighteenth birthday such as that by Lock et al. [ 42 ]. The Lock et al. [ 42 ] study may be of interest to those who are considering commissioning art therapy services for CAMHS, as it is a randomised controlled trial and suggests that art therapy may be a useful adjunct to Family-Based Treatment for adolescent anorexia nervosa in those with obsessive symptoms [ 42 ]. Our strict criteria also led us to exclude many studies where the primary focus was on educational issues including school behaviour or educational achievement—this is both a strength and limitation of our study. By excluding these studies, our systematic review can give useful information to CAMHS staff regarding the suitability of art therapy or art psychotherapy for children and adolescents with mental health difficulties. However, we note that a complete assessment of the effectiveness of art therapy or art psychotherapy in children would also include studies on the use of art therapy or art psychotherapy with children who have educational difficulties [ 43 , 44 ], those with physical illness or disability, as well as describing the many studies on art therapy or art psychotherapy in children who are refugees or living in emergency accommodation. We focused our review on quantitative research, but there are many mixed-methods studies in art therapy and art psychotherapy, where qualitative studies analysis may be used to generate hypotheses, and quantitative methods are used to test the hypothesis. A complete analysis of the effectiveness of art therapy or art psychotherapy in children could include summaries of qualitative or mixed-methods studies as well as quantitative studies.

Meanwhile, it should be noted that there is considerable evidence for the effectiveness of psychotherapy in general [ 45 , 46 ]. It has long been established that the common factors of alliance, empathy, expectations, cultural adaptation and therapist differences are important in the provision of effective psychotherapy [ 47 ]. Art therapy and art psychotherapy are more likely than the traditional talking therapies to provide these factors for those working with children.

Conclusions and future perspectives

There is extensive literature which suggests that art therapy or art psychotherapy provide a non-invasive therapeutic space for young children to work through and process their fears, trauma and difficulties. Art has been used to enhance the therapeutic relationship and provide a non-verbal means of communication for those unable to verbally describe their feelings or past experiences. We noted that there is considerably more qualitative and case description research than quantitative research regarding art therapy and art psychotherapy in children. We found some quantitative evidence that art therapy may be of benefit in the treatment of children who were exposed to trauma. However, while there are positive outcomes in many studies regarding art therapy for children with mental health difficulties, further robust research and randomised controlled trials are needed in order to define new and stronger evidence-based guidelines and to establish the true efficacy of art psychotherapy in this population. It would be helpful if there were studies with standardised outcome measures to facilitate cross comparison of results.

Availability of data and material

Data can be made available to reviewers if required.

Reynolds MW, Nabors L, Quinlan A (2000) The effectiveness of art therapy: does it work? Art Ther 17(3):207–213

Article Google Scholar

Slayton SC, D’archer J, Kaplan F (2010) Outcome studies on the efficacy of art therapy: a review of findings. J Am Art Therapy Assoc 27(3):108–118

Uttley L, Stevenson M, Scope A et al (2015) The clinical and cost effectiveness of group art therapy for people with non-psychotic mental health disorders: a systematic review and cost-effectiveness analysis [published correction appears in BMC Psychiatry. 2015;15:212]. BMC Psychiatry 15:151. Published 7 July 2015. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-015-0528-4

Maujean A, Pepping CA, Kendall E (2014) A systematic review of randomized controlled studies of art therapy. Art Ther 31(1):37–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2014.873696

Regev D, Cohen-Yatziv L (2018) Effectiveness of art therapy with adult clients in 2018-what progress has been made? Front Psychol 9:1531. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01531

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Clapp LA, Taylor EP, Di Folco S, Mackinnon VL (2019) Effectiveness of art therapy with pediatric populations affected by medical health conditions: a systematic review. Arts and Health 11(3):183–201. https://doi.org/10.1080/17533015.2018.1443952

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Winnicott DW (1971) Therapeutic consultations in child psychiatry. 1971 Karnac, London

Jung C (1968) Analytical psychology: the Tavistock lectures, 1968. New York, NY

Joint Commissioning Panel for Mental Health (2013) Guidance for commissioners of child and adolescent mental health services, available at https://www.jcpmh.info/resource/guidance-commissioners-child-adolescent-mental-health-services/ . Accessed 1st Dec 2020

Psychosis and schizophrenia in children and young people: recognition and management: Guidance, NICE (2013), available at https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg155/chapter/Recommendations#first-episode-psychosis . Accessed 20th Oct 2020

HSE National Clinical Programme for Early Intervention in Psychosis; available at https://www.hse.ie/eng/about/who/cspd/ncps/mental-health/psychosis/ . Last Accessed 01/06/2021

Depression in children and young people: identification and management: Guidance, NICE (2005) https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg28 . Accessed 20 Aug 2018

Depression in children and young people: identification and management | Guidance | NICE (2019) available at https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng134 . Accessed 23 July 2019

Post-traumatic stress disorder: Guidance, NICE (2018) https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng116/chapter/Recommendations#management-of-ptsd-in-children-young-people-and-adults . Accessed 21 Aug 2019

A Vision for Change – Report of the Expert Group on Mental Health Policy (2006) https://www.hse.ie/eng/services/publications/mentalhealth/mental-health---a-vision-for-change.pdf ; last accessed 01/06/2021

Sharing the vision: a mental health policy for everyone. https://www.gov.ie/en/publication/2e46f-sharing-the-vision-a-mental-health-policy-for-everyone/ ; last accessed 01/06/2021

Whiting PF, Rutjes AW, Westwood ME et al (2011) QUADAS-2: a revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann Intern Med 155(8):529–536. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-155-8-201110180-00009 (PMID: 22007046)

Chapman L, Morabito D, Ladakakos C et al (2001) The effectiveness of art therapy interventions in reducing post traumatic stress disorder (ptsd) symptoms in pediatric trauma patients. Art Ther 18(2):100–104

Lyshak-Stelzer F, Singer P, Patricia SJ, Chemtob CM (2007) Art therapy for adolescents with posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms: a pilot study. Art Ther 24(4):163–169

Mallay JN (2002) Art Therapy, an effective outreach intervention with traumatized children with suspected acquired brain injury. Arts Psychother 29(3):159–172

Gatta M, Gallo C, Vianello M (2014) Art therapy groups for adolescents with personality disorders. Arts Psychother 41(1):1–6

Briks A (2007) Art therapy with adolescents. Can Art Ther Assoc J 20(1):2–15

Henley D (2007) Naming the enemy: an art therapy intervention for children with bipolar and comorbid disorders. Art Ther 24(3):104–110

McCullough C (2009) A child’s use of transitional objects in art therapy to cope with divorcE. Art Ther 26(1):19–25

Lee SY (2013) “Flow” in art therapy: empowering immigrant children with adjustment difficulties. Art Ther 30(2):56–63

Lee SY (2015) Flow indicators in art therapy: artistic engagement of immigrant children with acculturation gaps. Art Ther 32(3):120–129

Shore A (2014) Art therapy, attachment, and the divided brain. Art Ther 31(2):91–94

Favara-Scacco C, Smirne G, Schilirò G, Di Cataldo A (2001) Art therapy as support for children with leukemia during painful procedures. Med Pediatr Oncol 36(4):474–480

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Siegel J, Iida H, Rachlin K, Yount G (2016) Expressive arts therapy with hospitalized children: a pilot study of co-creating healing sock creatures. J Pediatr Nurs 31(1):92–98

Kearns D (2004) Art therapy with a child experiencing sensory integration difficulty. Art Ther 21(2):95–101

Higenbottam W (2004) In her image. Can Art Ther Assoc J 17(1):10–16

Hartz L, Thick L (2005) Art therapy strategies to raise self-esteem in female juvenile offenders: a comparison of art psychotherapy and art as therapy approaches. Art Ther 22(2):70–80

Darewych O (2009) The effectiveness of art psychotherapy on self-esteem, self-concept, and depression in children with glaucoma. Can Art Ther Assoc J 22(2):2–17

Coholic DA, Eys M (2016) Benefits of an Arts-Based Mindfulness Group Intervention for Vulnerable Children. Child Adolesc Soc Work J 33:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-015-0431-3

Kovacs M (1992) Children’s depression inventory: manual. 1992 Multi-Health Systems North Tonawanda, NY

Fitts WH, Warren WL (1996) Tennessee self-concept scale: TSCS-2: Western Psychological Services Los Angeles

Piers EV, Herzberg DS (2002) Piers-Harris children’s self-concept scale: Manual: Western Psychological Services

Prince-Embury S, Courville T (2008) Comparison of one-, two-, and three-factor models of personal resiliency using the resiliency scales for children and adolescents. Can J Sch Psychol 23(1):11–25

LeCroy CW, Daley J (2001) Empowering adolescent girls: examining the present and building skills for the future with the “Go Grrrls” program. New York, NY: W. W. Norton

Gantt LM (2001) The formal elements art therapy scale: a measurement system for global variables in art. Art Ther 18(1):50–55

Harter S, Pike R (1984) The pictorial scale of perceived competence and social acceptance for young children. Child Dev 55:1969–1982

Lock J, Fitzpatrick KK, Agras WS et al (2018) Feasibility study combining art therapy or cognitive remediation therapy with family-based treatment for adolescent anorexia nervosa. Eur Eat Disord Rev 26(1):62–68. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.2571

McDonald A, Drey NS (2018) Primary-school-based art therapy: a review of controlled studies. Int J Art Ther 23(1):33–44

Cortina MA, Fazel M (2015) The art room: an evaluation of a targeted school-based group intervention for students with emotional and behavioural difficulties. Arts Psychother 42:35–40

Munder T, Flückiger C, Leichsenring F et al (2019) Is psychotherapy effective? A re-analysis of treatments for depression. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci 28(3):268–274

Stiles WB, Barkham M, Wheeler S (2015) Duration of psychological therapy: relation to recovery and improvement rates in UK routine practice. Br J Psychiatry 207(2):115–122

Wampold BE (2015) How important are the common factors in psychotherapy? An update. World Psychiatry 14(3):270–277

Download references

Acknowledgements

However we would like to acknowledge the support of the European Erasmus mobility scheme which allowed Dr. Irene Braito and Dr. Dicle Buyuktaskin to join the Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, University College Dublin for placements. We would also like to acknowledge the summer student research scheme in University College Dublin which supported Mohammad Ahmed.

Open Access funding provided by the IReL Consortium

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Medicine, University College Dublin, Dublin, Ireland

Irene Braito, Dicle Buyuktaskin, Mohammad Ahmed & Caoimhe Glancy

Paediatric Medicine, Great North Children’s Hospital, United Kingdom, UK

Irene Braito

Dublin North City and County Child and Adolescent Mental Health Service, Dublin, Ireland

Tara Rudd & Aisling Mulligan

Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Cizre Dr. Selahattin Cizrelioglu State Hospital, Cizre, Sirnak, Turkey

Dicle Buyuktaskin

Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, University College Dublin, Dublin, Ireland

Aisling Mulligan

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Aisling Mulligan .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

Professor Aisling Mulligan is the Director of the UCD Child Art Psychotherapy MSc programme. There are no other interests to be declared.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Braito, I., Rudd, T., Buyuktaskin, D. et al. Review: systematic review of effectiveness of art psychotherapy in children with mental health disorders. Ir J Med Sci 191 , 1369–1383 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-021-02688-y

Download citation

Received : 14 December 2020

Accepted : 09 June 2021

Published : 06 July 2021

Issue Date : June 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-021-02688-y

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Art therapy

- Mental health

- Psychotherapy

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

REVIEW article

Art therapy in the digital world: an integrative review of current practice and future directions.

- 1 Institute of Health Research and Innovation, University of the Highlands and Islands, Inverness, United Kingdom

- 2 Independent Researcher, Moray, United Kingdom

- 3 Population Health Science Institute, Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne, United Kingdom

- 4 Cumbria, Northumberland, Tyne and Wear NHS Foundation Trust, Newcastle upon Tyne, United Kingdom

Background: Psychotherapy interventions increasingly utilize digital technologies to improve access to therapy and its acceptability. Opportunities that digital technology potentially creates for art therapy reach beyond increased access to include new possibilities of adaptation and extension of therapy tool box. Given growing interest in practice and research in this area, it is important to investigate how art therapists engage with digital technology or how (and whether) practice might be safely adapted to include new potential modes of delivery and new arts media.

Methods: An integrative review of peer-reviewed literature on the use of digital technology in art therapy was conducted. The methodology used is particularly well suited for early stage exploratory inquiries, allowing for close examination of papers from a variety of methodological paradigms. Only studies that presented empirical outcomes were included in the formal analysis.

Findings: Over 400 records were screened and 12 studies were included in the synthesis, pertaining to both the use of digital technology for remote delivery and as a medium for art making. Included studies, adopting predominantly qualitative and mixed methods, are grouped according to their focus on: art therapists’ views and experiences, online/distance art therapy, and the use of digital arts media. Recurring themes are discussed, including potential benefits and risks of incorporating digital technology in sessions with clients, concerns relating to ethics, resistance toward digital arts media, technological limitations and implications for therapeutic relationship and therapy process. Propositions for best practice and technological innovations that could make some of the challenges redundant are also reviewed. Future directions in research are indicated and cautious openness is recommended in both research and practice.

Conclusion: The review documents growing research illustrating increased use of digital technology by art therapists for both online delivery and digital art making. Potentially immense opportunities that technology brings for art therapy should be considered alongside limitations and challenges of clinical, pragmatic and ethical nature. The review aims to invite conversations and further research to explore ways in which technology could increase relevance and reach of art therapy without compromising clients’ safety and key principles of the profession.

Introduction

Digital technology is increasingly present in psychotherapy practice worldwide, enabling clients and therapists to connect remotely. This way of improving access to therapy is important for those who might not otherwise be able to benefit from treatment due to living in more remote locations or having disabilities or mobility problems preventing them to attend therapy sessions in person. Despite this general trend of expansion in telehealth provision, to include also psychotherapy services, relatively little is known about its use within art therapy practice ( Choe, 2014 ; Levy et al., 2018 ). Research in the area focuses primarily on verbal therapies and more specifically on cognitive-behavioral therapy conducted online ( Hedman et al., 2012 ; Saddichha et al., 2014 ; Vigerland et al., 2016 ) with some notable examples of work highlighting issues key to psychodynamic psychotherapy ( De Bitencourt Machado et al., 2016 ; Feijó et al., 2018 ).

Art therapists support clients in engaging in creative processes to improve their psychological wellbeing. Due to incorporating art making within therapy process and the key role of triangular therapeutic relationship between the therapist, the client and the artwork ( Schaverien, 2000 ; Gussak and Rosal, 2016 ), art therapy practice is arguably more difficult to translate to online situations. However, suggestions have also been made that art therapy is particularly well suited to distance delivery, partially due to increasing ease of sharing images via online channels and non-reliance on verbal communication, and also due to dealing with symbols, metaphors and projections, which can manifest irrespective of medium used ( McNiff, 1999 ; Austin, 2009 ).

Art therapy profession has not entered the digital world only recently. In fact, it has been critically engaged in often difficult discussions on the risks and potential of digital technology for art therapy practice for over three decades ( Weinberg, 1985 ; Canter, 1987 , 1989 ; Johnson, 1987 ). Back in 1999 the Art Therapy Journal dedicated a special issue to the links between computer technology and art therapy and has repeated a similar issue a decade later. In 2019, the Journal asked therapists and researchers to consider ways in which professional assumptions can be updated, modernized or reframed to meet contemporary needs.

The use of digital technology in art therapy is not limited to online communication tools but extends to the application of digital media for the purpose of art making, equally relevant to face-to-face practice. While distance art therapy could potentially widen the reach of therapy to include new groups of clients, expanding the range of therapeutic tools to include digital arts media might extend art therapy toolbox to widen access for those clients who might not otherwise engage in traditional art materials for a variety of reasons.

However, it has been argued that the process of digital media adoption in art therapy is slow ( Carlton, 2014 ; Choe, 2014 ) and resistance to digital technology as well as concerns about the use of digital tools for art making in therapy have been reported in literature ( Kuleba, 2008 ; Klorer, 2009 ; Potash, 2009 ). It has been even implied that art therapists themselves may be more conservative and hesitant in their use of digital media than their clients ( McNiff, 1999 ; Peterson et al., 2005 ; Carlton, 2014 ). This cautiousness is stipulated to be informed by a heightened sense of responsibility for clients’ safety and wellbeing ( Orr, 2016 ). Art therapists’ own emotional factors and biases were cited to be important barriers to adoption of technology ( Asawa, 2009 ) while it has been suggested that therapists experience “conflict between the desire to promote art therapy and engage in technology and the desire to remain loyal to the field’s origins in traditional methods of communication and art media” ( Asawa, 2009 , p. 58).

The use of digital arts media is unique to art therapy practice and is perhaps not yet sufficiently researched for that reason, despite its potentially enormous implications for art therapy practice ( Kapitan, 2009 ). Lack of in-depth research on digital art making has been cited as a key barrier for practitioners to introduce digital arts media in therapy sessions ( Klorer, 2009 ; Potash, 2009 ). Similarly, limited guidelines from professional associations and importance of more specific technology-oriented ethical codes for practitioners are frequently highlighted ( Kuleba, 2008 ; Asawa, 2009 ; Alders et al., 2011 ; Evans, 2012 ).

A challenge identified in early stages of discussion on the use of technology in art therapy was the need for increased collaboration between art therapists, designers and developers in order to device technological solutions suitable to art therapy practice ( Gussak and Nyce, 1999 ). Limited attempts to develop art therapy-specific electronic devices to date lacked in-depth input from art therapists at the technical stage and, in consequence, appropriate integration of the established processes of art therapy with technology (e.g., Mihailidis et al., 2010 ; Mattson, 2015 ). In effect, art therapists who incorporate digital arts media in their practice elect to use painting apps not necessarily suitable for art therapy practice. There is also an ongoing debate on the tactile nature of art materials being lost if art is made using digital tools and potential impact on clients ( Kuleba, 2008 ; Garner, 2017 ). A similar discussion concerns the therapeutic relationship and specifically whether it could be recreated in distance therapy ( Klorer, 2009 ; Potash, 2009 ).

Despite these indicated debates on the usefulness of digital technology for art therapy practice and polarized opinions, some scholars and practitioners have advocated for increased efforts to incorporate digital art-making in the therapy process suggesting rising and permanent role of technology in art therapy ( McNiff, 2000 ; Kapitan, 2007 ; Thong, 2007 ). Given the rapidly growing interest in digital technology applications to art therapy practice, research has been developing relatively slowly and has not yet been systematized. Doing so would help paint an inevitably complex picture of how art therapy is currently engaging with digital technology and how it might make the best use of the opportunities it presents and critically address challenges early in the process.

In order to identify key topics important for practitioners and areas for further research, we aimed to capture and synthesize available research literature that explores the role of digital technology in the current and future art therapy practice (understood here as within-session work with clients). More specific research questions were:

- How do art therapists use digital technology in their practice?

- What benefits and challenges of using digital technology with clients do they identify?

- How do clients experience art therapy sessions with digital technology elements?

Methodology

Through our own experiences in research and practice and following some initial literature searches we were aware that the area we set to explore is complex and relatively novel. Thus, we anticipated that any published research accounts were likely to include a variety of study designs, appropriately to the overall exploratory character of research in the area and in line with research in arts therapies in general, which tends to draw upon diverse methodologies and beyond qualitative and quantitative paradigms, to include also arts-based approaches. We chose an integrative review framework as a guide to allow us to undertake a well-rounded but flexible evidence synthesis that would present a breadth of perspectives and combine methodologies without overvaluing specific hierarchies of evidence ( Whittemore and Knafl, 2005 ). Integrative review is an appropriate method at early stages of systematizing knowledge on a developing subject area ( Russell, 2005 ; Souza et al., 2010 ) and as such was deemed suitable for our exploratory work which aimed to identify central issues in the area, indicate the state of the scientific evidence across diverse methodological paradigms and identify gaps in current research ( Russell, 2005 ).

Search Strategy

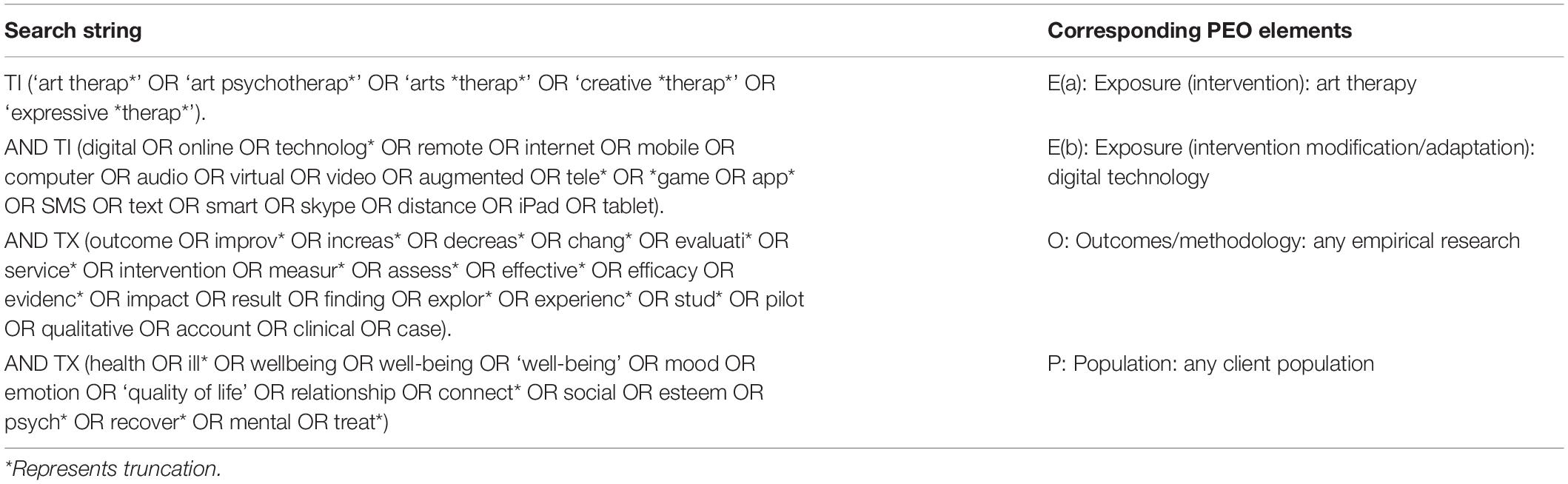

The following databases were searched for studies published until July 2020: MEDLINE, CINAHL Complete, APA PsycInfo, APA PsycArticles, Academic Search Complete and the Cochrane Library. Google Scholar search, backward and forward reference screening of included publications, and peer consultation were used to identify any other relevant articles. Search string ( Table 1 ) included the four key elements of this review: intervention (art therapy), intervention modification/adaptation (digital technology), methodology (empirical research) and population of interest (all client populations, any setting). These elements of a search strategy were conceptually guided by the PEO (Population-Exposure-Outcome) framework ( Khan et al., 2011 ; Bettany-Saltikov, 2016 ) instead of the more popular PICO (Population-Intervention-Comparison-Outcome), as the former was considered more suitable for capturing mixed method studies ( Methley et al., 2014 ).

Table 1. Search string development: concepts shaping this review and corresponding PEO elements.

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

We opted for broad inclusion criteria to report on all research studies pertaining to the use of digital technology in art therapy and therefore no specific definition of ‘digital’ was adopted other than how authors describe the focus of their paper(s). Time of publication was not initially considered a selection criterion but on reviewing the papers a decision was made to exclude those that focused on technology no longer relevant to modern practice, which, it was felt, related to articles published before 1999.

Articles were included in the review if they:

- concerned the use of modern (currently relevant) digital technology (DT) in within-session art therapy practice with clients;

- reported outcomes observed through empirical study, regardless of whether these were investigated using quantitative, qualitative, mixed or arts-based methods;

- were available online and in English.

Articles were excluded if they:

- focused exclusively on the use of digital technology for office work, assessment, supervision, training or research;

- were PhD theses, dissertations or books/book chapters;

- were theoretical/opinion papers with no empirical data reported.

Data Extraction

Data were extracted from included papers using a data collection form based on the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR; Hoffmann et al., 2014 ) which helped to record the characteristics of the studies, interventions, outcomes and main findings reported.

Data Synthesis

We followed the recommended process for synthesizing data in an integrative review ( Whittemore and Knafl, 2005 ) by initially comparing the extracted data item by item, recognizing similarities and groupings, to eventually identifying meaningful categories for studies and interventions included in the review. Each of the papers was read multiple times to generate a mental map of ideas explored across the literature. Iterative process of examining the classified data enabled us to identify themes and relationships which constitute the essence of this synthesis process. Due to expectedly heterogenic character of included studies, attempts at establishing a meaningful classification were at all times guided by the above principles.

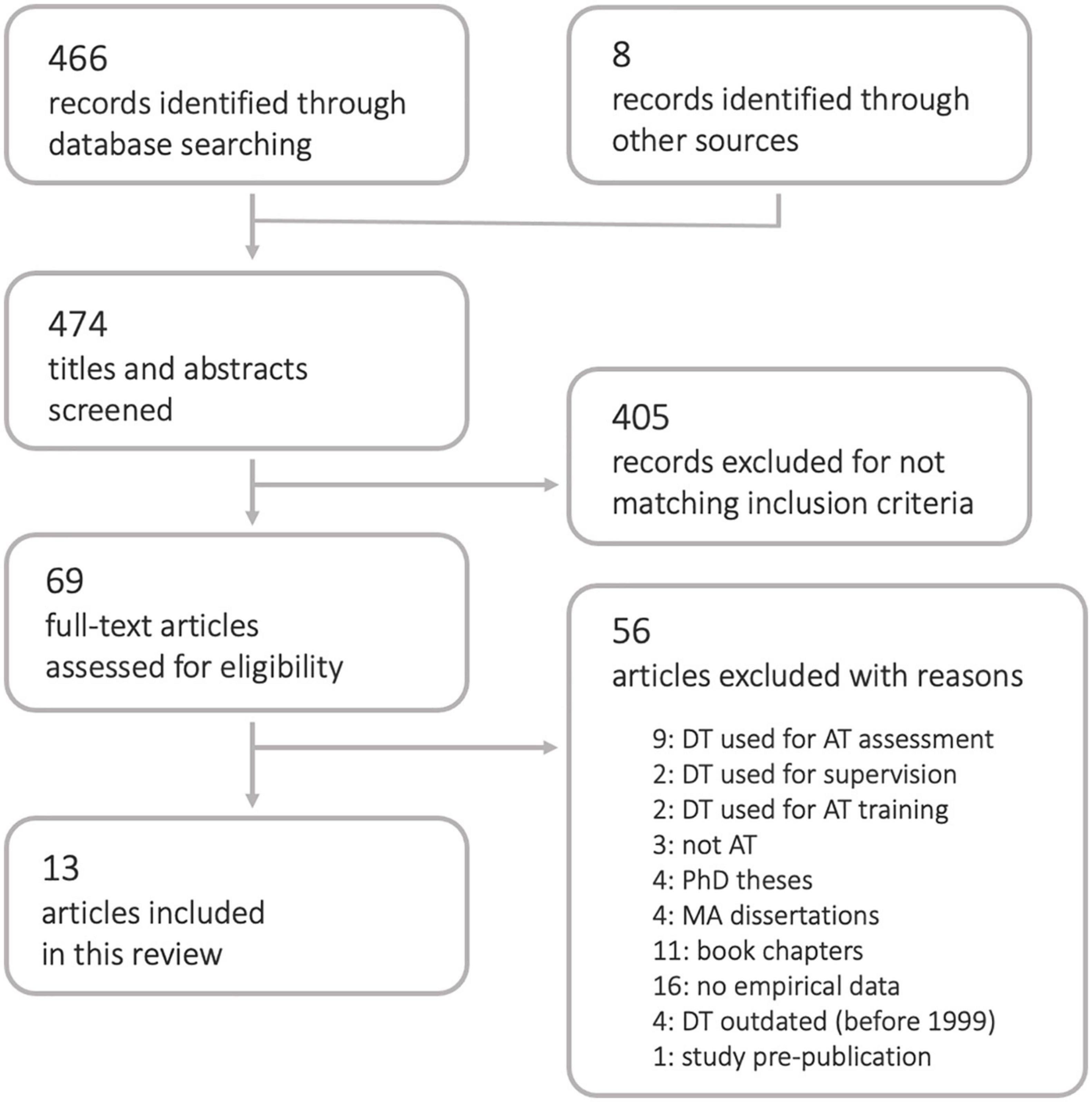

Of 474 records identified through database searching and consulting reference lists, 405 were excluded based on title and abstract screening. Full-texts for the remaining 69 records were consulted and 56 were excluded with reasons ( Figure 1 ). Many of the excluded papers were opinion pieces which did not present empirical outcomes, but were nevertheless helpful in gaining a fuller perspective of the topic and are frequently referred to in the discussion. Selection process resulted in 13 articles included in this review.

Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram.

Study Characteristics

All of included research was undertaken either in the US (9 studies) or in Canada (4 studies). The studies were varied methodologically, with qualitative (6 studies), quantitative (1 study) and mixed methods (5 studies) paradigms all represented. The studies employed primarily surveys, focus groups, interviews, case studies and prototyping workshops, often following participatory and mixed-method designs, which seems appropriate for early explorations and for highly applied research with direct implications for clinical practice. Art therapists themselves were research participants in the majority of included papers with only three reporting specifically on client experiences ( Darewych et al., 2015 ; Levy et al., 2018 ; Spooner et al., 2019 ). Numbers of participants in qualitative, client-focused and/or workshop-based studies (8 studies) were generally low (ranging from single figures to 25 participants) and numbers of respondents in survey-based studies (4 studies) ranged from 45 to 195. Two papers ( Collie and Čubranić, 1999 , 2002 ) reported on the same research study and are referred to jointly throughout this review (including in tables).

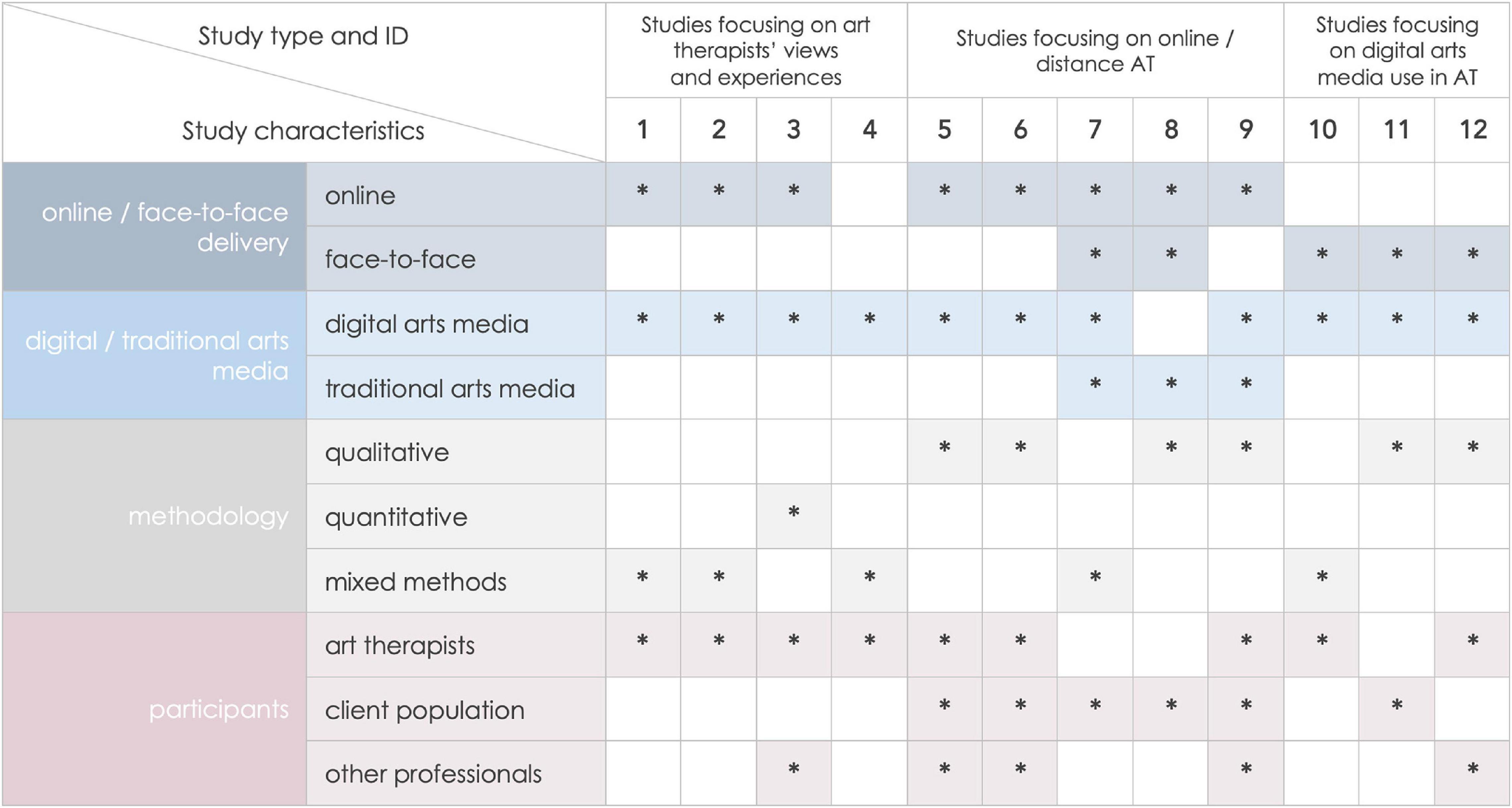

The articles tended to discuss the use of digital technology in art therapy practice in a more general way or focus on one of the two uses of digital technology identified in our initial literature review: the use of online tools for distance art therapy and the use of digital media for art making within therapy sessions. Majority of the survey-based studies which examined directly arts therapists’ opinions on the use of digital technology in art therapy were interested in both uses of technology, while workshop-based studies typically focused on either distance delivery or exploration of digital media for art making. There were overlaps and we tried to capture the relationship between the digital technology interest and the categories we eventually decided to group the articles into in Figure 2 , which also provides an overview of methodologies and participant groups. The results are presented below in three seemingly separate groups of studies. However, the concepts explored in this research are inevitably intertwined, which is important to note to avoid over-simplifying the nature of opportunities and challenges brought into art therapy realm by the progressing developments in digital technology. Paragraphs below present key messages from the papers grouped in the three categories, except findings pertaining directly to the challenges and benefits of using digital technology within therapy, which will be discussed separately.

Figure 2. Selected characteristics of included studies: online/face-to-face delivery, digital/traditional arts media, methodology, participant group. *Indicates that a characteristic is present in a study.

General Views on Technology, Online Art Therapy, and Digital Arts Media

Art therapists’ views and opinions.

Four articles from two US-based research teams focused entirely on the views and opinions of art therapists on the use of digital technology in art therapy practice and utilized a survey design ( Table 2 : Peterson et al., 2005 ; Orr, 2006 , 2012 ; Peterson, 2010 ). They gathered both the therapists’ experience (based on practice) and expectations (based on personal attitudes). A total number of responses for the four included papers was 474, with majority coming from qualified art therapists and students in art therapy training (in one survey, only 61.5% of respondents were qualified art therapists with the other respondents being not practizing attendees of the AAT conference, Peterson et al., 2005 ). In one study, follow-up interviews were also undertaken with eight respondents selected according to their readiness for adopting new technologies ( Peterson, 2010 ).

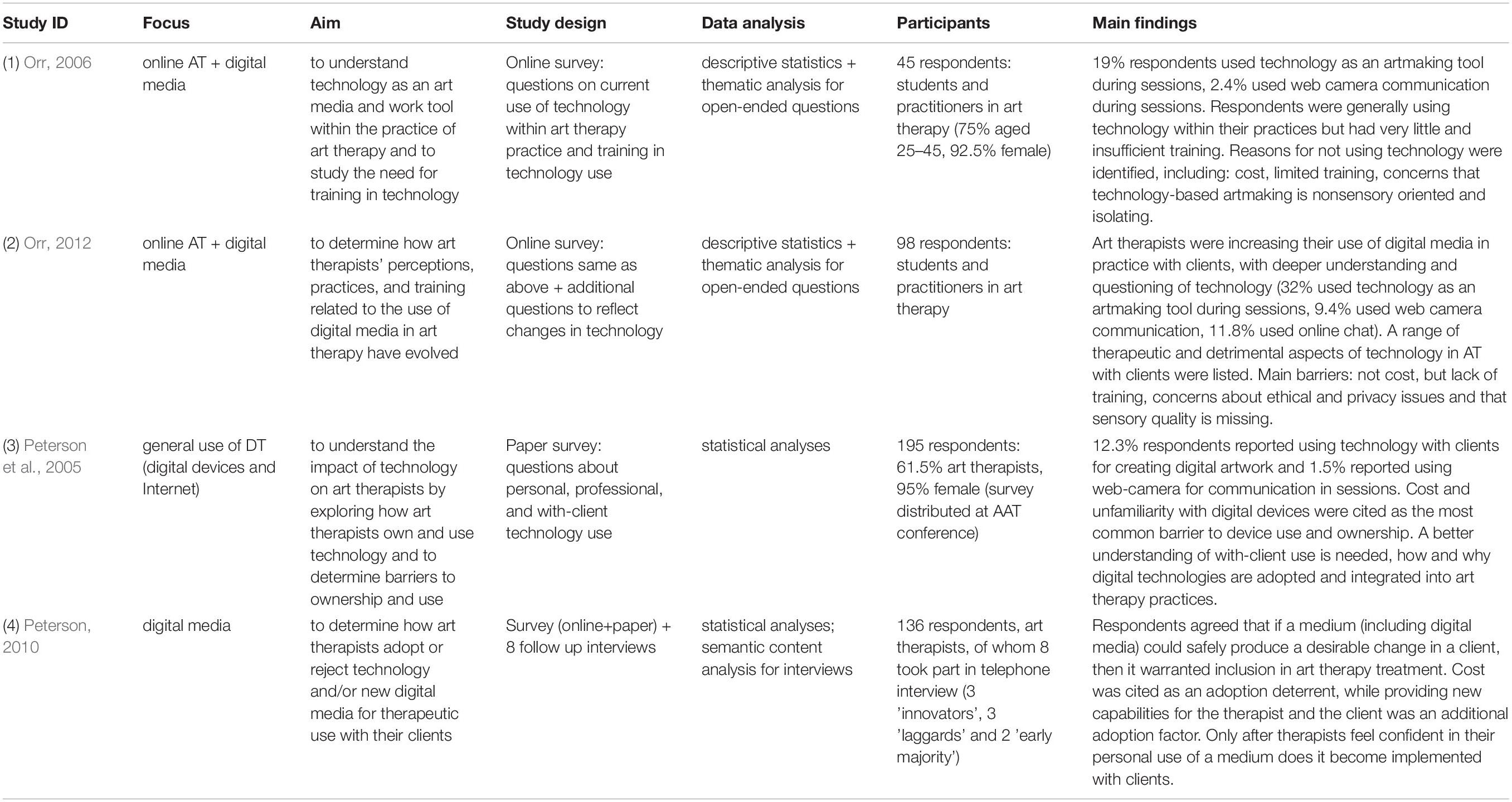

Table 2. Characteristics of studies focusing on art therapists’ views and experiences.

Although all studies reported also on the general adoption of technology by art therapists in personal and professional practice including office work, research and training, this review extracted findings pertaining to in-session practice with clients as far as it was possible or to any aspects of digital technology use that directly affect work with clients. Therefore, information on other uses of technology by art therapists, although reported in the cited papers, is not presented here. The general message coming from all included surveys was that art therapists tended to use technology far more often for their own personal practice and for administrative professional tasks than within sessions with clients.

Across the studies, a trend emerged suggesting an increasing use of digital technology within art therapy sessions. A study comparing results from surveys undertaken 7 years apart, found that between 2004 and 2011 art therapists increased their use of digital media in their art therapy practice with clients: from 19 to 32% using technology as an artmaking tool during sessions and from 2.4 to 9.4% using web camera communication during sessions ( Orr, 2006 , 2012 ). In addition, in the 2011 survey, 11.8% respondents reported using online chat ( Orr, 2012 ). In an even earlier survey from 2002 ( Peterson et al., 2005 ), 12.3% respondents reported using technology with clients for creating digital artwork and 1.5% reported using web camera for communication in sessions, confirming the rise in in-session technology use over the years.

Two studies highlighted the need for specialist training in digital technology use for art therapists. Orr (2006) reported that in her 2004 survey only 28.5% respondents received some training in using technology to create art, 4.8% respondents felt that the training received met their needs well, while none felt that it met their needs very well. In 2011, the percentage of therapists who reported receiving training in the use of technology as therapeutic tool with clients increased slightly and stood at 36.5% and 11.5% of respondents felt that it has met their needs well ( Orr, 2012 ). Despite this rise in training opportunities, the author concluded that the training “has not kept up with the adoption rate of technology by art therapists” ( Orr, 2012 , p. 234) and that more and better education is indeed needed.

Another survey conducted almost a decade ago moved beyond establishing how art therapists use digital technology to determine their reasons for adopting or rejecting emerging digital tools for therapeutic use with their clients ( Peterson, 2010 ). A client’s response to a form of digital technology was found to be a key factor in art therapists’ decision as to whether the technology was an effective therapeutic medium. The respondents agreed that if a medium (including digital media) could safely contribute to a desirable change, then its inclusion in treatment is warranted. Cost was, again, cited as an adoption deterrent, while providing new capabilities for the therapist and the client was an additional adoption factor.

A theme consistent across the presented surveys seems to be the highly ethical and professional approach of art therapists in deciding on the use of technology with clients. The responses seemed consistent in indicating that a degree of familiarity with digital medium is necessary for therapists to implement it in therapy session with clients. Importantly, the clients’ response to any novel arts medium is the guiding factor in making decision about a specific technology adoption. Being certain of the benefits for clients seems to be a prerequisite for introducing a specific technology in art therapy sessions. The survey from 2011 revealed that art therapists were increasingly more concerned about ethical and confidentiality issues than 7 years before and that their main reservations about using digital media were linked with uncertainties around ethics ( Orr, 2006 , 2012 ).

Online Art Therapy: Digital Technology Used for Distance Art Therapy Sessions

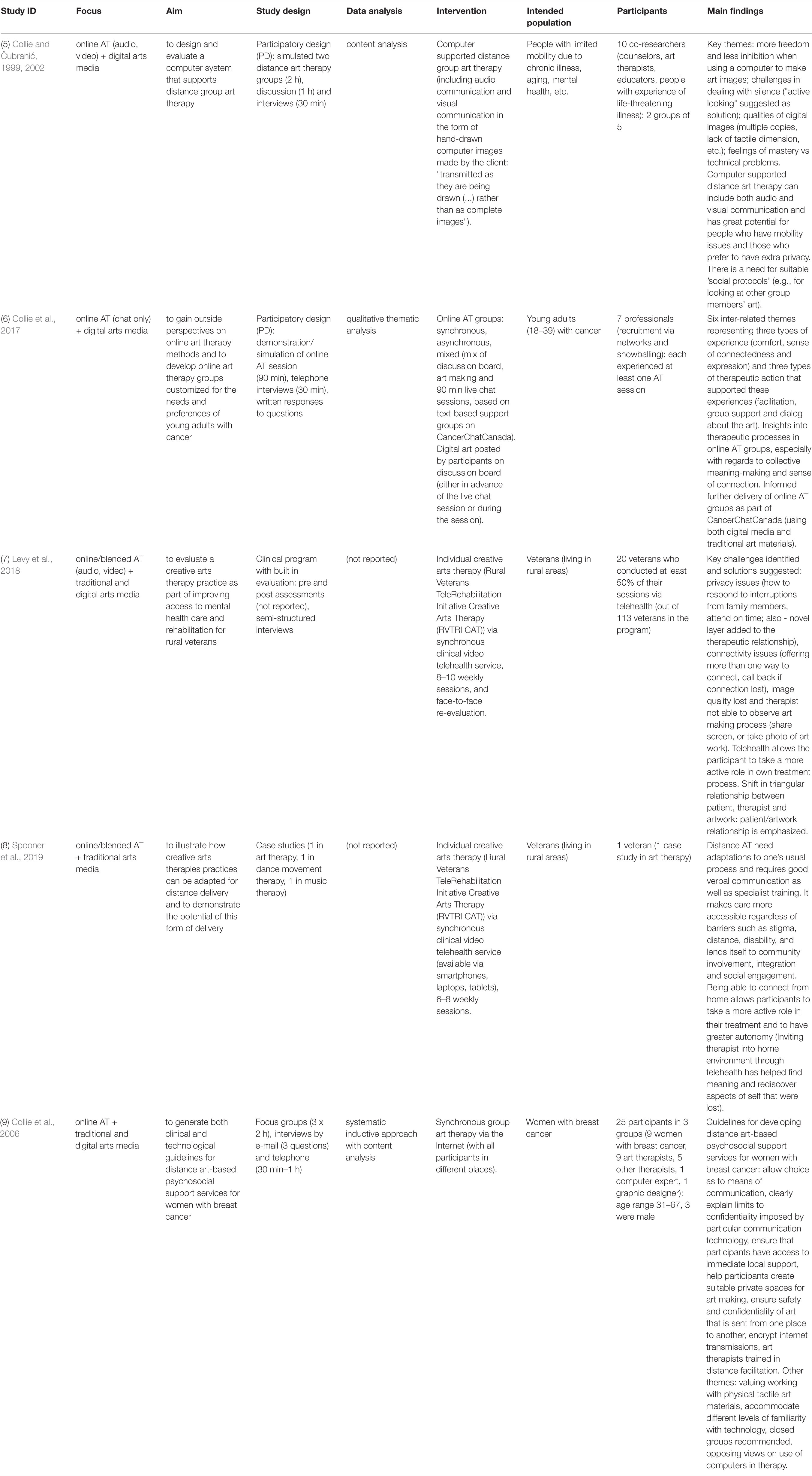

We identified five research studies (of which one was reported in two articles) that were concerned primarily with application of digital technology solutions to remote art therapy delivery ( Table 3 : Collie and Čubranić, 1999 , 2002 ; Collie et al., 2006 , 2017 ; Levy et al., 2018 ; Spooner et al., 2019 ). Three of these studies, all from the same Canadian research team, similarly to research discussed above, examined art therapists’ opinions through focus groups ( Collie et al., 2006 ), interviews and participatory designs, including simulated online art therapy interventions ( Collie and Čubranić, 1999 , 2002 ; Collie et al., 2017 ). The studies were concerned with development of an online art therapy service for people with limited mobility, women with breast cancer and, most recently, young adult cancer patients. Two other studies from one US-based research team examined the experience of veterans participating in a blended (primarily online, with face-to-face initial assessment and re-evaluation) creative arts therapies program via semi-structured interviews and a single case study of an art therapy participant ( Levy et al., 2018 ; Spooner et al., 2019 ). Both studies were undertaken as part of a clinical program evaluation and therefore did not follow a fully experimental design. Although pre-post assessments were undertaken, these have not been reported yet.

Table 3. Characteristics of studies focusing on online / distance art therapy.

In two studies ( Collie and Čubranić, 2002 ; Collie et al., 2017 ) the participants were also co-researchers, described as art therapists, counselors, educators and people with experience of life-threatening illness (total n = 17), who were invited to take part in simulated online art therapy group sessions. The interventions experienced in the two studies were quite different, one being a group art therapy session in which participants communicated and shared digital images created in real time ( Collie and Čubranić, 2002 ), while the other included both synchronous and asynchronous elements, allowing participants to take part in live chat-based session and also upload images to a discussion board outside of scheduled session times ( Collie et al., 2017 ). In both studies participants shared their experience via discussions and follow-up interviews. Another study ( Collie et al., 2006 ) used focus groups and interviews with similarly diverse participants ( n = 25) to generate clinical and technological guidelines for distance art therapy.

One of the key conclusions coming from the studies was that online group art therapy, being a relatively novel intervention, would require certain adaptations in relation to face-to-face practice ( Spooner et al., 2019 ), for example development of suitable “social protocols” ( Collie and Čubranić, 1999 ), refining of communication procedures ( Collie and Čubranić, 2002 ) and development of “new therapeutic models” ( Collie et al., 2006 ). These adaptations would need to comply with the legal and ethical guidelines, with new telehealth-related guidance eventually required for art therapy profession and initially adapted from related disciplines such as counseling or psychology ( Spooner et al., 2019 ).

Among participating health professionals (including a large proportion of art therapists), there seemed to be quite polarized opinions about the use of computers in therapy, with majority in favor of distance art therapy, but some participants also expressing concerns about “antitherapeutic” character of technology ( Collie et al., 2006 ). Distance delivery was not generally viewed as allowing anonymous participation – in fact, high value was put on close personal interaction regardless of communication technology used ( Collie et al., 2006 ). A sense of connection and “togetherness” was observed in a study of an online group art therapy ( Collie et al., 2017 ), suggesting that the usual therapeutic group factors may be transferable in a distance therapy setup.

In their evaluation of a US-based creative arts therapy program for veterans living in rural areas, Levy et al. (2018) reported primarily positive experiences of using an online art therapy service. Participants appreciated the delivery mode and not having to travel long distances to sessions and described the normally expected positive effects of therapy like increased confidence, improved communication and making sense of emotions through self-expression. A case study of a female veteran participating in the program ( Spooner et al., 2019 ) initially revealed a decrease in perceived quality of life and satisfaction with health, which was attributed by her and her therapist to the actual progress in therapy being made: becoming more aware of emotions and ready to explore more difficult topics to eventually rediscover aspects of herself that were previously lost. These accounts seem to confirm that the therapeutic process can manifest within distance art therapy sessions and therapeutic outcomes can be achieved.

Two papers, published almost two decades apart ( Collie and Čubranić, 1999 ; Levy et al., 2018 ), proposed that distance art therapy creates subtle shifts within the usual triangular relationship between the client, the therapist and the artwork ( Schaverien, 2000 ). It was suggested that the client/artwork relationship is emphasized, while the client and the therapist are geographically separated and the client remains particularly connected and “co-present” with the art. This could create new opportunities for therapy and mean that the physical separation between the client and the therapist might affect art therapy less than verbal forms of therapy.

Digital Arts Media: Digital Technology Used for Making Artwork in Art Therapy Sessions

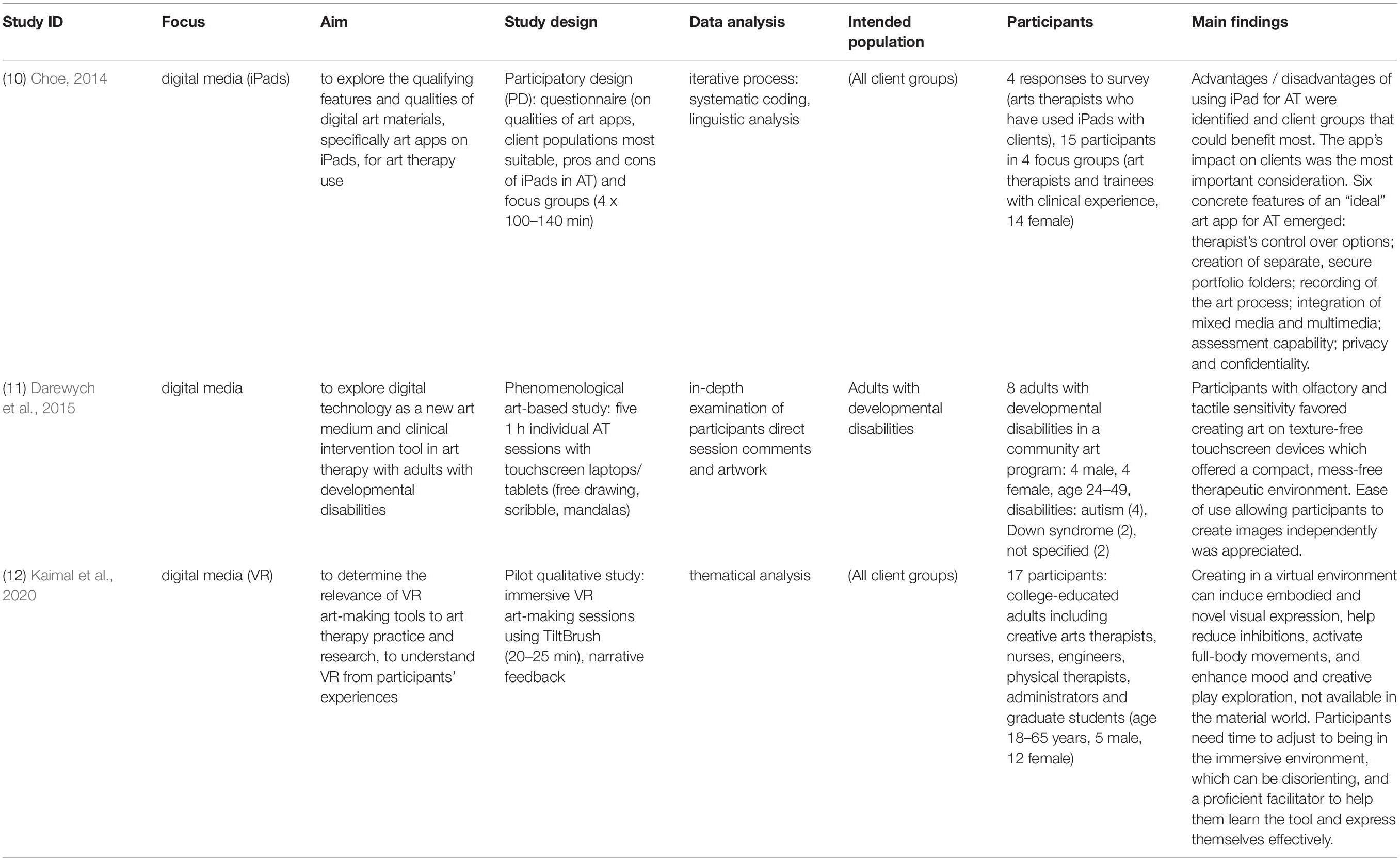

Three articles focused primarily on the use of digital media within face-to-face therapy settings ( Table 4 : Choe, 2014 ; Darewych et al., 2015 ; Kaimal et al., 2016 ), but it needs to be noted that the technologies discussed can potentially be successfully applied in distance therapy situations. Two papers examined applicability of iPads and/or other touchscreen devices to art therapy. One study reported on the experiences of adults with developmental disabilities through phenomenological approach ( Darewych et al., 2015 ), while the other set to explore some unique potentially therapeutic features of art applications for iPads from art therapists’ perspective, utilizing the methods of a survey and focus groups ( Choe, 2014 ). The third and most recent study focused on the relevance of virtual reality art-making tools ( Kaimal et al., 2016 ). This small selection of papers nevertheless provides a good overview of the current application of digital media to making art in art therapy sessions and introduces a client perspective.

Table 4. Characteristics of studies focusing on digital arts media use in art therapy.

In her investigation on iPads’ applicability to art therapy, Choe (2014) defined three qualities of art apps most valued by art therapists: ease of use or intuitiveness, simplicity, and responsiveness. The therapists who took part in the study believed that it was essential that any art apps were matched with the needs of individual clients and that no single app examined in this project could satisfy the needs of all clients and art therapists. The study found that the therapists had higher expectations of digital than of traditional art materials and were not prepared to compromise on the app’s speed, control or immediacy of working with images. It was suggested that certain client populations may in particular benefit from digital art making in therapy, including, among others, clients with developmental disorders, clients with suppressed immune systems (due to iPads being easier to clean), and clients who have experienced tactile trauma. It was also proposed that digital art making posed risks to some client groups, including those with internet addiction, psychosis or obsessive-compulsive disorder ( Choe, 2014 ). Another study similarly recommended caution about using immersive VR-based tools for art making with clients managing acute psychiatric symptoms ( Kaimal et al., 2020 ).

A study examining the experiences of eight adults with developmental disabilities who used digital art making in art therapy sessions ( Darewych et al., 2015 ), concluded that the participants appreciated the ease of use of the apps tested, which allowed them to create images independently. Those with olfactory and tactile sensitivity preferred the texture-free touchscreen devices to traditional art materials.

Making art in virtual reality, as “a new medium that challenges the traditional laws of the physical world and materials” ( Kaimal et al., 2020 , p. 17), was also tried and tested for use in art therapy in a small experiential study. The authors propose that therapeutic change can occur in VR environments and that it relates primarily to the unique qualities of the medium and to the fact that the participant is exposed to new environments of choice and creative opportunities not available in the material world ( Kaimal et al., 2020 ).

Challenges and Opportunities of Using Digital Technology in Art Therapy Practice

The following section presents findings across the three sets of studies that pertain more specifically to the challenges and opportunities of the use of digital technology in art therapy practice. Although these are grouped into three categories, not dissimilar to the categories of studies presented above, findings are based on contributions from across all papers examined in this review. We found frequent overlaps in aspects of technology discussed within papers, for example it was common for studies generally focusing on digital media to provide insights on remote delivery and vice versa. Not wanting to lose those, we decided to thematically analyze the content of all 13 included articles to identify themes relating to the advantages and disadvantages of technology use in art therapy, pertaining in particular to digital media and technologies and processes enabling remote delivery.

General Concerns About Including Digital Technology in Art Therapy Practice

Cost of equipment.

High cost of equipment was cited as the main reason for not including technology in art therapy sessions in a survey from 2004 ( Orr, 2006 ) and from 2002 ( Peterson et al., 2005 ), particularly the cost of electronic art tools advanced enough to allow for true emotional expression ( Orr, 2006 ). However, this issue was not as prominent in a survey from 2011, when it seemed that ethical concerns of art therapists were predominant barriers to introducing technology in therapy sessions ( Orr, 2012 ).

The importance of a specialist training for art therapists in the use of digital technology is highlighted across studies ( Collie et al., 2006 ; Orr, 2006 , 2012 ; Kaimal et al., 2020 ). It is recognized that skilful and active facilitation, essential for providing appropriate container (safe environment) and ensuring client safety ( Collie et al., 2017 ; Kaimal et al., 2020 ), requires extra time for learning ( Orr, 2006 ). Similarly, more effort and time investment in training might be needed on the client’s side, either to adjust to an online mode of therapy ( Spooner et al., 2019 ) or to a new type of digital arts media ( Kaimal et al., 2020 ). A concern has been raised about this additional learning potentially impeding the therapeutic process and that extra time might be needed for establishing a therapeutic relationship ( Collie et al., 2006 ).

Technical issues

Unfamiliarity and not being comfortable with the devices were cited as key barriers to engaging technology in art therapy sessions ( Peterson et al., 2005 ; Orr, 2006 ), which could present a challenge for both the therapist and the client ( Spooner et al., 2019 ). Problems with connectivity, including not having sufficient strength of signal and reliability, were cited as common issues in studies that examined online art therapy ( Levy et al., 2018 ; Spooner et al., 2019 ). Both inexperience and technical breakdowns could cause distress to clients ( Collie et al., 2006 , 2017 ).

Concerns Related to Online Art Therapy

Confidentiality and safety.