Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 02 January 2024

Scale up urban agriculture to leverage transformative food systems change, advance social–ecological resilience and improve sustainability

- Jiangxiao Qiu ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3741-5213 1 , 2 ,

- Hui Zhao ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1414-3443 1 , 2 ,

- Ni-Bin Chang 3 ,

- Chloe B. Wardropper ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0652-2315 4 ,

- Catherine Campbell ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1574-3221 5 ,

- Jacopo A. Baggio ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9616-4143 6 ,

- Zhengfei Guan 7 ,

- Patrice Kohl 8 ,

- Joshua Newell ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1440-8715 9 &

- Jianguo Wu 10

Nature Food volume 5 , pages 83–92 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

1861 Accesses

3 Citations

76 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Agroecology

- Ecosystem services

Scaling up urban agriculture could leverage transformative change, to build and maintain resilient and sustainable urban systems. Current understanding of drivers, processes and pathways for scaling up urban agriculture, however, remains fragmentary and largely siloed in disparate disciplines and sectors. Here we draw on multiple disciplinary domains to present an integrated conceptual framework of urban agriculture and synthesize literature to reveal its social–ecological effects across scales. We demonstrate plausible multi-phase developmental pathways, including dynamics, accelerators and feedback associated with scaling up urban agriculture. Finally, we discuss key considerations for scaling up urban agriculture, including diversity, heterogeneity, connectivity, spatial synergies and trade-offs, nonlinearity, scale and polycentricity. Our framework provides a transdisciplinary roadmap for policy, planning and collaborative engagement to scale up urban agriculture and catalyse transformative change towards more robust urban resilience and sustainability.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

111,21 € per year

only 9,27 € per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Global projections of future urban land expansion under shared socioeconomic pathways

Urban change as an untapped opportunity for climate adaptation

Urbanization can benefit agricultural production with large-scale farming in China

Data availability.

All data used in this manuscript are made publicly available and deposited into Figshare at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.24449713 .

Code availability

All code used in this manuscript is made publicly available and deposited into Figshare at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.24449713 .

Elmqvist, T. et al. Urbanization in and for the Anthropocene. npj Urban Sustain. 1 , 1–6 (2021).

Article Google Scholar

Forman, R. T. T. & Wu, J. Where to put the next billion people. Nature 537 , 608–611 (2016).

Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Elmqvist, T. et al. Sustainability and resilience for transformation in the urban century. Nat. Sustain. 2 , 267–273 (2019).

Seto, K. C. & Satterthwaite, D. Interactions between urbanization and global environmental change. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2 , 127–128 (2010).

Meerow, S., Newell, J. P. & Stults, M. Defining urban resilience: a review. Landsc. Urban Plan. 147 , 38–49 (2016).

Steffen, W. et al. Planetary boundaries: guiding human development on a changing planet. Science 347 , 1259855 (2015).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

O’Brien, K. Global environmental change II: from adaptation to deliberate transformation. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 36 , 667–676 (2012).

Chaffin, B. C. et al. Transformative environmental governance. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 41 , 399–423 (2016).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

McPhearson, T. et al. Radical changes are needed for transformations to a good Anthropocene. npj Urban Sustain. 1 , 1–13 (2021).

Alberti, M., McPhearson, T. & Gonzalez, A. Embracing urban complexity. in Urban Planet: Knowledge Towards Sustainable Cities 1st edn, 45–67 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2018); https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316647554.004

Hebinck, A. et al. A sustainability compass for policy navigation to sustainable food systems. Glob. Food Sec. 29 , 100546 (2021).

Vermeulen, S. J., Dinesh, D., Howden, S. M., Cramer, L. & Thornton, P. K. Transformation in practice: a review of empirical cases of transformational adaptation in agriculture under climate change. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2 , 65 (2018).

Schell, C. J. et al. The ecological and evolutionary consequences of systemic racism in urban environments. Science 369 (2020).

Schlosberg, D., Collins, L. B. & Niemeyer, S. Adaptation policy and community discourse: risk, vulnerability, and just transformation. Environ. Politics 26 , 413–437 (2017).

Zimmerer, K. S. et al. Grand challenges in urban agriculture: ecological and social approaches to transformative sustainability. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 5 , 101 (2021).

Hebinck, A. et al. Exploring the transformative potential of urban food. npj Urban Sustain. 1 , 9 (2021).

Forman, R. T. Urban Regions: Ecology and Planning Beyond the City (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2008).

Langemeyer, J., Madrid-Lopez, C., Mendoza Beltran, A. & Villalba Mendez, G. Urban agriculture—a necessary pathway towards urban resilience and global sustainability? Landsc. Urban Plan. 210 , 104055 (2021).

Lal, R. Home gardening and urban agriculture for advancing food and nutritional security in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Food Secur. 12 , 871–876 (2020).

Siegner, A., Sowerwine, J. & Acey, C. Does urban agriculture improve food security? Examining the nexus of food access and distribution of urban produced foods in the United States: a systematic review. Sustainability 10 , 2988 (2018).

Gerster-Bentaya, M. Urban agriculture’s contributions to urban food security and nutrition. in Cities and Agriculture: Developing Resilient Urban Food Systems 139–161 (2015).

Payen, F. T. et al. How much food can we grow in urban areas? Food production and crop yields of urban agriculture: a meta‐analysis. Earth’s Future 10 , e2022EF002748 (2022).

Article ADS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Tornaghi, C. Critical geography of urban agriculture. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 38 , 551–567 (2014).

Hawes, J. K., Gounaridis, D. & Newell, J. P. Does urban agriculture lead to gentrification? Landsc. Urban Plan. 225 , 104447 (2022).

Tornaghi, C. Urban agriculture in the food‐disabling city: (re)defining urban food justice, reimagining a politics of empowerment. Antipode 49 , 781–801 (2017).

Campbell, C. G., Ruiz-Menjivar, J. & DeLong, A. Commercial urban agriculture in Florida: needs, opportunities, and barriers. Horttechnology 32 , 331–341 (2022).

Pearson, L. J., Pearson, L. & Pearson, C. J. Sustainable urban agriculture: stocktake and opportunities. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 8 , 7–19 (2010).

Schneider, M. & McMichael, P. Deepening, and repairing, the metabolic rift. J. Peasant Stud. 37 , 461–484 (2010).

Lukas, M., Rohn, H., Lettenmeier, M., Liedtke, C. & Wiesen, K. The nutritional footprint—integrated methodology using environmental and health indicators to indicate potential for absolute reduction of natural resource use in the field of food and nutrition. J. Clean. Prod. 132 , 161–170 (2016).

Harvey, J. & Jowsey, E. Urban Land Economics (Bloomsbury, 2019).

Newell, J. P., Foster, A., Borgman, M. & Meerow, S. Ecosystem services of urban agriculture and prospects for scaling up production: a study of Detroit. Cities 125 , 103664 (2022).

Goldstein, B., Hauschild, M., Fernández, J. & Birkved, M. Urban versus conventional agriculture, taxonomy of resource profiles: a review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 36 , 9 (2016).

Wilhelm, J. A. & Smith, R. G. Ecosystem services and land sparing potential of urban and peri-urban agriculture: a review. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 33 , 481–494 (2018).

Lovell, S. T. Multifunctional urban agriculture for sustainable land use planning in the United States. Sustainability 2 , 2499–2522 (2010).

Evans, D. L. et al. Ecosystem service delivery by urban agriculture and green infrastructure—a systematic review. Ecosyst. Serv. 54 , 101405 (2022).

Ramaswami, A. et al. An urban systems framework to assess the trans-boundary food–energy–water nexus: implementation in Delhi, India. Environ. Res. Lett. 12 , 025008 (2017).

Article ADS Google Scholar

Hu, Y. et al. Transboundary environmental footprints of the urban food supply chain and mitigation strategies. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54 , 10460–10471 (2020).

Chang, N.-B. et al. Integrative technology hubs for urban food–energy–water nexuses and cost–benefit–risk tradeoffs (II): design strategies for urban sustainability. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 51 , 1533–1583 (2021).

Asseng, S. et al. Wheat yield potential in controlled-environment vertical farms. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2002655117 (2020).

Daigger, G. T. et al. Scaling Up Agriculture in City-Regions to Mitigate FEW System Impacts (2015).

Zhang, S., Bi, X. T. & Clift, R. A life cycle assessment of integrated dairy farm–greenhouse systems in British Columbia. Bioresour. Technol. 150 , 496–505 (2013).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Benis, K. & Ferrao, P. Potential mitigation of the environmental impacts of food systems through urban and peri-urban agriculture (UPA)—a life cycle assessment approach. J. Clean. Prod. 140 , 784–795 (2017).

Lwasa, S. et al. A meta-analysis of urban and peri-urban agriculture and forestry in mediating climate change. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 13 , 68–73 (2015).

Valencia, A., Qiu, J. & Chang, N.-B. Integrating sustainability indicators and governance structures via clustering analysis and multicriteria decision making for an urban agriculture network. Ecol. Indic. 142 , 109237 (2022).

Bryld, E. Potentials, problems, and policy implications for urban agriculture in developing countries. Agric. Human Values 20 , 79–86 (2003).

Wortman, S. E. & Lovell, S. T. Environmental challenges threatening the growth of urban agriculture in the United States. J. Environ. Qual. 42 , 1283–1294 (2013).

Cinner, J. E. & Barnes, M. L. Social dimensions of resilience in social–ecological systems. One Earth 1 , 51–56 (2019).

Reyers, B., Folke, C., Moore, M.-L., Biggs, R. & Galaz, V. Social–ecological systems insights for navigating the dynamics of the Anthropocene. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 43 , 267–289 (2018).

Eakin, H. & Lemos, M. C. Institutions and change: the challenge of building adaptive capacity in Latin America. Glob. Environ. Change 1 , 1–3 (2010).

Grothmann, T. & Patt, A. Adaptive capacity and human cognition: the process of individual adaptation to climate change. Glob. Environ. Change 15 , 199–213 (2005).

Boonstra, W. J., Björkvik, E., Haider, L. J. & Masterson, V. Human responses to social–ecological traps. Sustain. Sci. 11 , 877–889 (2016).

Frank, E., Eakin, H. & López-Carr, D. Social identity, perception and motivation in adaptation to climate risk in the coffee sector of Chiapas, Mexico. Glob. Environ. Change 21 , 66–76 (2011).

Eakin, H. et al. Cognitive and institutional influences on farmers’ adaptive capacity: insights into barriers and opportunities for transformative change in central Arizona. Reg. Environ. Change 16 , 801–814 (2016).

Baggio, J. A. & Hillis, V. Managing ecological disturbances: learning and the structure of social–ecological networks. Environ. Model. Softw. 109 , 32–40 (2018).

Nyborg, K. et al. Social norms as solutions. Science 354 , 42–43 (2016).

Horst, M., McClintock, N. & Hoey, L. The intersection of planning, urban agriculture, and food justice: a review of the literature. J. Am. Plann. Assoc. 83 , 277–295 (2017).

Loorbach, D., Frantzeskaki, N. & Avelino, F. Sustainability transitions research: transforming science and practice for societal change. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 42 , 599–626 (2017).

Rostow, W. W. The stages of economic growth. Econ. Hist. Rev. 12 , 1–16 (1959).

Drescher, A. W., Isendahl, C., Cruz, M. C., Karg, H. & Menakanit, A. Urban and peri-urban agriculture in the Global South. in Urban Ecology in the Global South 293–324 (2021).

de Zeeuw, H., Dubbeling, M., Wilbers, J. & van Veenhuizen, R. Courses of action for municipal policies on urban agriculture. Urban Agric. Mag. 16 , 10–19 (2006).

Google Scholar

Van Veenhuizen, R. & Danso, G. Profitability and Sustainability of Urban and Periurban Agriculture . vol. 19 (Food & Agriculture Org., 2007).

O’Sullivan, C. A., Bonnett, G. D., McIntyre, C. L., Hochman, Z. & Wasson, A. P. Strategies to improve the productivity, product diversity and profitability of urban agriculture. Agric. Syst. 174 , 133–144 (2019).

McClintock, N. Radical, reformist, and garden-variety neoliberal: coming to terms with urban agriculture’s contradictions. Local Environ. 19 , 147–171 (2014).

Gliessman, S. R. Agroecology: roots of resistance to industrialized food systems. in Agroecology: A Transdisciplinary, Participatory and Action-oriented Approach 23–35 (2016).

Dehaene, M., Tornaghi, C. & Sage, C. Mending the metabolic rift: placing the ‘urban’ in urban agriculture. in Urban Agriculture Europe 174–177 (Jovis, 2016).

Rundgren, G. Food: from commodity to commons. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 29 , 103–121 (2016).

Patel, R., Balakrishnan, R. & Narayan, U. Transgressing rights: La Via Campesina’s call for food sovereignty/Exploring collaborations: heterodox economics and an economic social rights framework/Workers in the informal sector: special challenges for economic human rights. Fem. Econ. 13 , 87–116 (2007).

MacKinnon, D. & Derickson, K. D. From resilience to resourcefulness: a critique of resilience policy and activism. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 37 , 253–270 (2013).

Hudson, R. Resilient regions in an uncertain world: wishful thinking or a practical reality? Camb. J. Reg. Econ. Soc. 3 , 11–25 (2010).

Qiu, J. et al. Evidence-based causal chains for linking health, development, and conservation actions. Bioscience 68 , 182–193 (2018).

Zhou, W., Pickett, S. T. A. & McPhearson, T. Conceptual frameworks facilitate integration for transdisciplinary urban science. npj Urban Sustain. 1 , 1–11 (2021).

Tornaghi, C. & Dehaene, M. Resourcing an Agroecological Urbanism: Political, Transformational and Territorial Dimensions (Routledge, 2021).

Dorr, E., Goldstein, B., Horvath, A., Aubry, C. & Gabrielle, B. Environmental impacts and resource use of urban agriculture: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ. Res. Lett. 16 , 093002 (2021).

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar

Download references

Acknowledgements

This study is funded by the National Science Foundation (ICER-1830036). J.Q. also acknowledges the US Department of Agriculture, National Institute of Food and Agriculture, Research Capacity Fund (FLA-FTL-006277) and McIntire–Stennis (FLA-FTL-006371), and University of Florida School of Natural Resources and Environment for partial financial support of this work.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Forest, Fisheries, and Geomatics Sciences, Fort Lauderdale Research and Education Center, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, USA

Jiangxiao Qiu & Hui Zhao

School of Natural Resources and Environment, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, USA

Department of Civil, Environmental, and Construction Engineering, University of Central Florida, Orlando, FL, USA

Ni-Bin Chang

Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Sciences, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, IL, USA

Chloe B. Wardropper

Department of Family, Youth and Community Sciences, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, USA

Catherine Campbell

School of Politics, Security, and International Affairs and National Center for Integrated Coastal Research, University of Central Florida, Orlando, FL, USA

Jacopo A. Baggio

Food and Resource Economics Department, Gulf Coast Research and Education Center, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, USA

Zhengfei Guan

Department of Environmental Studies, College of Environmental Science and Forestry, State University of New York, Syracuse, NY, USA

Patrice Kohl

School for Environment and Sustainability, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA

Joshua Newell

School of Life Sciences and School of Sustainability, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ, USA

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

J.Q. led the initial conceptualization of this work, and all authors contributed to the development of ideas. J.Q. designed the analyses, developed the visualizations and led the writing of the original draft. H.Z. conducted the literature search and screening of relevant empirical urban agriculture studies. All co-authors contributed to editing and revision of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Jiangxiao Qiu .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information.

Nature Food thanks Manuel Bickel, Chiara Tornaghi and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended data fig. 1 schematic diagram to illustrate the concept and spatial scale of the ‘urban regions’, at which urban agriculture is defined..

Urban regions are essentially a large regional landscape encompassing a major central population center, a network of urban centers, and a mosaic of surrounding natural, rural, and production lands with internal heterogeneity and contrasting patterns. Different forms of urban agriculture practices can occur in locales (for example, as shown in arrows) along the spatial gradient of the urban regions.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Nascent real-world examples of scaling up urban agriculture across the globe.

Paris, France (A) has opened one of the world’s largest operating urban rooftop farms to feed its residents and foster climate resilience; New York City, United States (B) boasts the most extensive network of community gardens (>550) to improve food access and life quality of residents and local communities; and Shanghai, China (C) has implemented the masterplans (construction began in 2017) to develop Sunqiao Urban Agriculture District ( ∼ 100 hectare) with numerous large-scale vertical farming systems for feeding burgeoning urban populations and reducing external food dependency.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Dominant urban agriculture types along the infrastructure and technology, and size gradients, with typical commercial (purple colored) and non-commercial (green colored) types.

Size of the boxes is in relative terms, and approximates the common and representative range of each urban agriculture type along these two axes. The location of urban agriculture types along these gradients is determined based on qualitative notions of the authors after the comprehensive review of the contemporary literature, which may evolve over time.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information.

Combined PDF Supplementary Information with three sections.

Reporting Summary

Rights and permissions.

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Qiu, J., Zhao, H., Chang, NB. et al. Scale up urban agriculture to leverage transformative food systems change, advance social–ecological resilience and improve sustainability. Nat Food 5 , 83–92 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-023-00902-x

Download citation

Received : 10 April 2023

Accepted : 21 November 2023

Published : 02 January 2024

Issue Date : January 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-023-00902-x

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

- Open supplemental data

- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Original research article, consumers' perception of urban farming—an exploratory study.

- 1 Morrison School of Agribusiness, W. P. Carey School of Business, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ, United States

- 2 School of Sustainable Engineering and the Built Environment, Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ, United States

- 3 School of Mathematical and Statistical Sciences, College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ, United States

Urban agriculture offers the opportunity to provide fresh, local food to urban communities. However, urban agriculture can only be successfully embedded in urban areas if consumers perceive urban farming positively and accept urban farms in their community. Success of urban agriculture is rooted in positive perception of those living close by, and the perception strongly affects acceptance of farming within individuals' direct proximity. This research investigates perception and acceptance of urban agriculture through a qualitative, exploratory field study with N = 19 residents from a major metropolitan area in the southwest U.S. Specifically, in this exploratory research we implement the method of concept mapping testing its use in the field of Agroecology and Ecosystem Services. In the concept mapping procedure, respondents are free to write down all the associations that come to mind when presented with a stimulus, such as, “urban farming.” When applying concept mapping, participants are asked to recall associations and then directly link them to each other displaying their knowledge structure, i.e., perception. Data were analyzed using content analysis and semantic network analysis. Consumers' perception of urban farming is related to the following categories: environment, society, economy, and food and attributes. The number of positive associations is much higher than the number of negative associations signaling that consumers would be likely to accept farming close to where they live. Furthermore, our findings show that individuals' perceptions can differ greatly in terms of what they associate with urban farming and how they evaluate it. While some only think of a few things, others have well-developed knowledge structures. Overall, investigating consumers' perception helps designing strategies for the successful adoption of urban farming.

Introduction

At present, the number of people living in urban areas worldwide is over three billion, or 55% of the world population, and it is projected that 68% of the world's population will be living in urban areas by 2050 ( United Nations, 2018 ). In the United States alone, 82% of the population currently lives in urban areas ( World Bank, 2016 ). The continued expansion of cities nationwide places a heavy toll on the demand for resources, such as sustainable infrastructure and affordable food retail options, to meet the basic needs of households living within city limits. Within the food sector, the accelerating rate of migration into cities coupled with a growing population imposes the challenge of producing sufficient quantities of food ( Satterthwaite et al., 2010 ). This challenge needs to be addressed to ensure everyone has access to high-quality, nutrient-dense food. Simultaneously, it raises the question of how to provide satisfactory nourishment while consumers are increasingly asking for fresh and local foods ( Grebitus et al., 2017 ).

With urbanization on the rise, one solution to this challenge is the development and expansion of urban agriculture 1 . Figure 1 below shows the replacement of agricultural areas (yellow) by urban areas (red) in the Phoenix Metropolitan Area. Urban agriculture is a growing sector within the farming industry that aims to increase overall food production in urban and peri-urban areas through the conversion of available land into agricultural farms. As reported in Smith et al. (2017) , there are 67,032 vacant parcels (19,592 hectares) potentially suitable for urban agriculture in the Phoenix Metropolitan Area.

Figure 1 . Land use map showing the replacement of agricultural areas (yellow) by urban areas (red). Data from the 2006 and 2016 USGS National Land Cover Dataset.

Cities across the United States have already begun to integrate food production, such as commercial urban farms and private or community gardens, into communities ( Hughes and Boys, 2015 ; Printezis and Grebitus, 2018 ). To predict whether urban farming will be successful and to influence its longevity, it is important to understand consumer perception ( Grebitus and Bruhn, 2008 ). Hence, the objective of this research is to investigate how consumers perceive urban farming and to evaluate whether they would accept this form of commercial agriculture close to their residence.

Food produced in urban and peri-urban communities has various implications. For example, for small- to mid-size farmers, the profitability of urban farmers can be dependent on producing local foods that can be (exclusively) sold through direct channels, such as farmers markets. Urban agriculture also has an effect on societal health. Direct access to local produce through direct-to-consumer marketing channels affects the dietary quality and diversity of food choices of urban consumers. Unlike large agricultural production facilities that occupy 75% of the land in the U.S. and predominantly grow commodity crops used for animal feed, biofuels, and industrial inputs ( DeHaan, 2015 ), outputs from urban agricultural production are largely specialty crops, which require comparatively minimal processing before consumption. Specialty crops, which include most fruits, vegetables, and tree nuts, are rich in nutrients, vitamins, and minerals and are constituents of an optimal diet ( WHO, 2018 ). In this way, both the increased consumption of fruits and vegetables along with the diversity of produce consumed is closely linked with positive human health outcomes and serves as a measure of societal health. Finally, urban agriculture affects environmental quality through changes in urban-vegetation-atmosphere interactions, e.g., the reduction in food miles and the mitigation effects of urban heat islands, as a result of urban agriculture practices. Overall, urban agriculture has the potential to provide a number of benefits, for instance, improving sustainability, and local ecology ( Wakefield et al., 2007 ), assisting with food security ( Dimitri et al., 2016 ; Freedman et al., 2016 ; Sadler, 2016 ), and contributing to healthy dietary patterns ( Zezza and Tasciotti, 2010 ; Warren et al., 2015 ).

Alternatively, urban agriculture may produce negative externalities ( Brown and Jameton, 2000 ; Wortman and Lovell, 2013 ). For example, a farmer growing food in a city might encounter pushback by the people living next to the farm who might be bothered by dirt and noise from machinery, odors from organic fertilizers, or they might be afraid that pesticides and fertilizers are polluting the air they breathe and the water they drink. A recent study by Wielemaker et al. (2019) showed urban farmers apply fertilizers in excess of crop needs by 450–600%, potentially leading to negative public perceptions. At the same time, urban farms might be preferred due to access to fresh, local, nutrient-dense food which enhance positive perceptions. This suggests that consumers' perception and acceptance of urban farms is vital to ensure that urban agriculture can be successful ( Grebitus et al., 2017 ).

Previous empirical research on urban agriculture has focused on investigating the relationship between urban agriculture and nutrition (variety, food security, and nutrition status), with a particular emphasis on its role in developing countries [see Warren et al. (2015) for a broad review of previous studies]. Mougeot (2005) compiles case studies of development strategies used by developing countries and pays specific attention to the potential that urban agriculture has in meeting development goals (e.g., increased food availability, decreased poverty, increased health status) in each respective country. Studies focused on developed countries highlight the social context of urban agriculture. They assess how community gardens affect communities ( Armstrong, 2000 ; Wakefield et al., 2007 ; Firth et al., 2011 ), analyze what urban farmers need when only limited resources are available ( Surls et al., 2015 ), and examine success factors of urban agriculture, such as positive consumer attitudes and increased knowledge regarding local food production ( Grebitus et al., 2017 ).

Recently, Grebitus et al. (2017) found in a quantitative online consumer survey that consumers perceive urban agriculture positively based on food quality characteristics, such as food safety and health. More generally, related to perception, they find the three sustainability pillars (economy, society, and environment) are important with regards to consumer perception. Nevertheless, the authors state that consumers' perception is sometimes conflicting. For example, some consumers perceive produce from urban farms as less expensive while others perceive it as more expensive. Our research builds on the study by Grebitus et al. (2017) by investigating the in-depth perception of urban farming using qualitative, exploratory methods in a face-to-face study. While Grebitus et al. (2017) used a word association test, we employ the method of concept mapping. Concept maps can uncover cognitive structures related to urban farming and show differences between individuals regarding their knowledge structures.

The implications of our findings will offer several insights to those charged with designing and implementing food and agricultural policy. Such policies have the potential to affect new and emerging trends in urban communities, stimulate the growth of direct-to-consumer marketing channels where small- to mid-size farmers sell their products and address the effects of urban agriculture on the environment. Our results will provide insight into how urban farming is perceived by individuals to ensure that incorporating farms in urban areas is accepted by those living there. For example, if our analysis shows that consumers are apprehensive and afraid, e.g., of pesticides or fertilizer run-off, targeted communication can be used to alleviate such tensions.

In the following section, the methodological background is described covering concept mapping, counting, and content analysis. Section three presents the results and section four concludes.

Materials and Methods

Concept mapping.

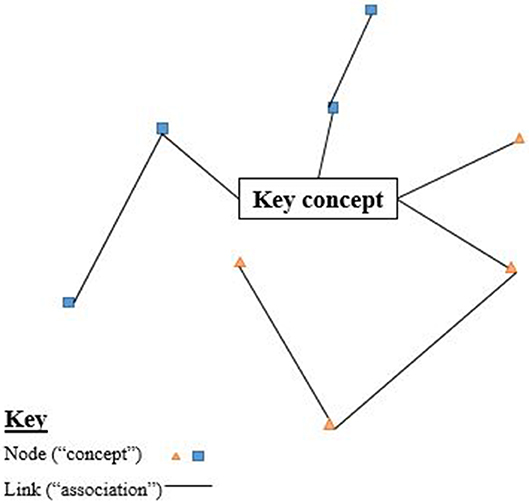

In consumer behavior research, perception is defined as subjective and selective information processing ( Kroeber-Riel et al., 2009 ). Whether something is positively or negatively perceived by consumers is determined by cognitive structures, i.e., semantic networks, which capture a part of the knowledge (associations/concepts) in memory ( Martin, 1985 ; Joiner, 1998 ). A semantic network is composed of nodes, which represent concepts and units of information, and links, connecting the concepts, which represent the type and the strength of the association between the concepts ( Cowley and Mitchell, 2003 ). To investigate perception toward urban farming we aim to provide insight into consumers' individual cognitive structures, i.e., semantic networks ( Kanwar et al., 1981 ; Jonassen et al., 1993 ).

Associative elicitation techniques are appropriate to analyze semantic networks ( Bonato, 1990 ). By presenting stimuli, spontaneous reactions and unconscious thoughts are evoked and enable us to analyze individual cognitive structures ( Grebitus and Bruhn, 2008 ). A great variety of associative elicitation techniques exists, ranging from the most qualitative techniques like word association technique ( Roininen et al., 2006 ; Ares et al., 2008 ) to more structured techniques such as repertory grid ( Sampson, 1972 ; Russell and Cox, 2004 ) or laddering ( Grunert and Bech-Larsen, 2005 ).

For this study, the qualitative graphing procedure concept mapping was chosen. Concept mapping is a method that produces a schematic representation of the relationships of stored units of information, which are activated by the stimulus ( Zsambok, 1993 ). The interviewees are asked to recall freely their associations concerning a certain stimulus ( Olson and Muderrisoglu, 1979 ). Additionally, they are asked to directly link the associations to each other, which allows the visualization of the semantic networks ( Bonato, 1990 ). The open setting of tasks optimizes the variety of associations of the interviewees ( Joiner, 1998 ). Concept map diagrams are two-dimensional and show relationships between units of information concerning a certain theme. The concepts are understood as terms, i.e., associations, which come to mind regarding the stimulus ( Jonassen et al., 1993 ).

Concept mapping is supported by semantic network theory and can be explained using the spreading activation network model ( Rye and Rubba, 1998 ). Retrieving stored knowledge can be explained by the spreading activation ( Collins and Loftus, 1975 ; Anderson, 1983a , b ). When consumers perceive/associate something with a stimulus, information-processing takes place and cognitive structures are activated for interpretation, assessment, and decision-making. The stored knowledge is retrieved by spreading activation from associations ( Anderson, 1983b ). In this context, existing networks are active cognitive units that can, once activated, influence behavior directly ( Olson, 1978 ). How much and what information is integrated into the information-processing depends on the construction of the semantic network ( Cowley and Mitchell, 2003 ).

The spread of activation constantly expands through the links to all connected nodes (associations) in the network, starting with the first activated concept. At first, it expands to all the nodes directly linked to the first node, and then to all the nodes linked to each of those nodes. This way, the activation is spreading through all nodes of the network, even through those nodes that are only indirectly associated with the “stimulus node” ( Collins and Loftus, 1975 ). The stronger the link between two nodes, the easier and faster the activation passes to the connected nodes ( Cowley and Mitchell, 2003 ). How far the activation spreads also depends on the distance from the stimulus node. Concepts that are closely related and directly linked will be activated faster and with higher intensity ( Henderson et al., 1998 ). See Figure 2 for an illustration of nodes and links in a semantic network.

Figure 2 . Illustrative figure of a semantic network.

The concept mapping technique elicits respondents to recall knowledge from long-term memory and to write down what they know, which stimulates the spread of activation in memory ( Rye and Rubba, 1998 ). The more linkages a semantic network contains, the higher is the dimensionality and complexity of cognitive structures. The higher the dimensionality of the cognitive structures, the larger the number of concepts that can be activated and the more differentiated and complex the networks ( Kanwar et al., 1981 ). Depending on personal relevance and involvement, consumers' semantic networks are more or less extensively structured ( Peter and Olson, 2008 ).

Concept Mapping Application to Urban Agriculture

To conduct the concept mapping procedure, we adapted the instructions used by Grebitus (2008) . Respondents received an instructions page. At the top of the page, the respondents read the following passage:

Researchers believe that our knowledge is stored in memory. The knowledge we have can be described through central concepts and the relationship between them. These concepts depict our belief of different knowledge domains such as food or vacation. These beliefs can also be related to each other. For example, when you think of a car, you may spontaneously think of “tires”, “white”, or “traffic”. If you then think further, “gas” and “expensive” may come to mind. These can also be related to each other and thus are indirectly related with a car. People have a lot of such associations. To find out yours is one objective of this study .

Respondents were then given a blank piece of paper and started by writing the term “Urban Farming” in the center of the paper. They were then instructed to start thinking of anything that comes to mind, related to the key concept and write it down. After writing down the concepts, the interviewees had to construct the concept map by connecting all the words that they believe, in their minds, are related to each other and belong to each other (i.e., drawing links). Then, they had to add a plus or minus to associations they thought to be positive or negative.

To investigate how many associations and what kind of information is stored in memory concerning urban farming, the items were counted and aggregated ( Kanwar et al., 1981 ; Martin, 1985 ; Grebitus, 2008 ). Next, the individual associations were evaluated using qualitative content analysis following Mayring (2002) . This allowed us to make assumptions, and investigate intent and motivation regarding the topic in a formal way ( Stempel, 1981 ; Hsia, 1988 ). Content analysis is an objective and systematic way to apply quantitative measures to qualitative data ( Stempel, 1981 ; Wimmer and Dominick, 1983 ; Hsia, 1988 , p. 320).

The aim of this study is to provide meaning to the participants' associations. Hence, we classified the content according to categories. This offers a framework to assess the perception of urban farming. The associations written down by the respondents in the concept maps regarding the key stimulus, urban farming, were organized and categorized, then they were added up into frequencies ( Bonato, 1990 ; Lamnek, 1995 ). The categories are the core of the perception analysis. They are used to investigate the topic further ( Wimmer and Dominick, 1983 ). Therefore, the categories should be closely related to the research topic. They have to be practical, reliable, comprehensive (each word fits into one of the categories) and mutually exclusive (each word fits only one category) ( Stempel, 1981 ; Wimmer and Dominick, 1983 ). In this research, we used the categories provided by Grebitus et al. (2017) who used a word association test for the key concept: urban agriculture, a close proxy for the one used in our study “urban farming.” Accordingly, we used the three sustainability pillars Economy, Society, and Environment, as well as, Food and Attributes, and Others as categories to group the data for urban farming in a meaningful way.

Empirical Results

Design of the study and sample characteristics.

To investigate consumer perception of urban farming, exploratory, face-to-face interviews were conducted. The qualitative graphing procedure concept mapping was used to reveal consumers' associations regarding urban farming. In addition to concept mapping, participants filled out a survey to collect socio-demographic information. For detailed information on the data collected, refer to Table S1 in the Supplementary Material.

We collected data in Phoenix, AZ. We chose this location because the Phoenix metropolitan area is ideal for a case study as it is home to a large and growing urban population. Phoenix provides context that has many similar natural and social complexities and barriers (e.g., climate challenges, a lack of food access, rapidly growing, diverse, multi-cultural population), with a large variance in educational and economic levels of residents compared to other urban areas in the U.S. The Phoenix metropolitan area (i.e., Maricopa and Pinal Counties) is the eleventh largest metro area in the U.S. with Maricopa County identified as the fastest-growing county in the U.S. ( U.S. Census Bureau, 2019 ). This rapid population growth demonstrates an important need for sustainable urban farming practices, given the benefits of food security, economic stability, and environmental conservation. Phoenix has a climate where food can be grown all year round, with multiple growing seasons. The extended growing season allows harvest year-round and may affect consumer purchasing patterns and related dietary quality differently than when food is grown only during certain seasons. Meanwhile, Phoenix experiences unique climatic extremes: from being an urban heat island, experiencing short and long-term drought, while simultaneously dealing with seasonal monsoons that can bring rapid and devastating flooding. Hence, urban farming might have different environmental impacts compared to cities where this is not the case. Also, within urban planning and development, Phoenix has begun to recognize urban agriculture as an attractive fixture in revitalizing communities, especially since urban expansion has replaced nearby agriculture at a large rate ( Shrestha et al., 2012 ). Also, Phoenix has vacant land available that can potentially be used for urban farming ( Aragon et al., 2019 ).

We interviewed a total of 19 participants in the summer of 2019 at two locations. A total of 14 participants were interviewed at a large public farmers' market. Another five participants were interviewed at a second location near an open green space 2 . All interviews were carried out by one interviewer. The sample is a convenience sample. Participants were reimbursed for their time with $10 each.

In terms of sample characteristics, 47% of the sample were female, the average age was 38 years old. Household size was on average three persons in the household, with 26% having children in the household. 21% were graduate students and 21% were undergraduate students. In terms of the level of education, 26% had some college education, 32% a Bachelor's degree, and 42% a graduate degree.

Perception of Urban Farming: Results From Content Analysis

This paper aims to analyze consumers' perception of urban farming. This objective is based on the notion that for urban farming to be more fully and successfully integrated into urban and peri-urban communities, consumers need to perceive it positively.

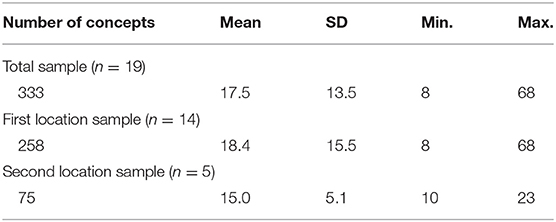

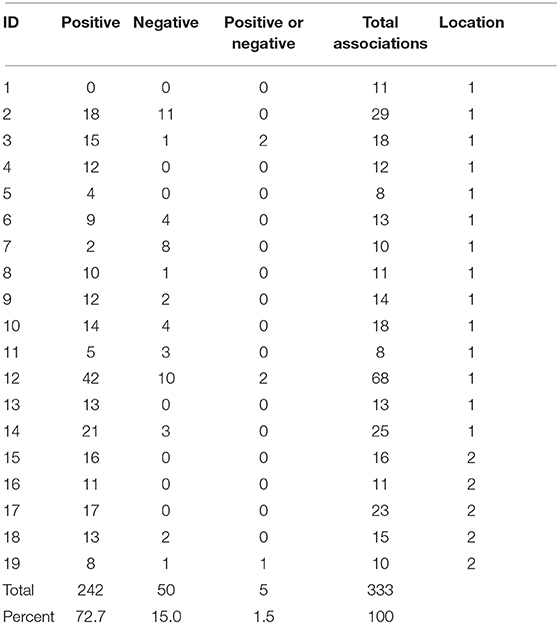

Table 1 depicts the descriptive findings for the counting of the concepts of the two groups and the total over both samples. The results show a total of 333 associations were written down when considering all participants. The mean is 17.5 concepts with a standard deviation of 13.5. The lowest number of concepts associated with urban farming is eight, the highest 68. The farmers' market sample had a higher mean (18.4) than the second location ( M = 15). The standard deviation, however, was considerably smaller at the second location ( SD = 5.1) compared to the farmers' market sample ( SD = 15.5).

Table 1 . Descriptive statistics for the associated concepts.

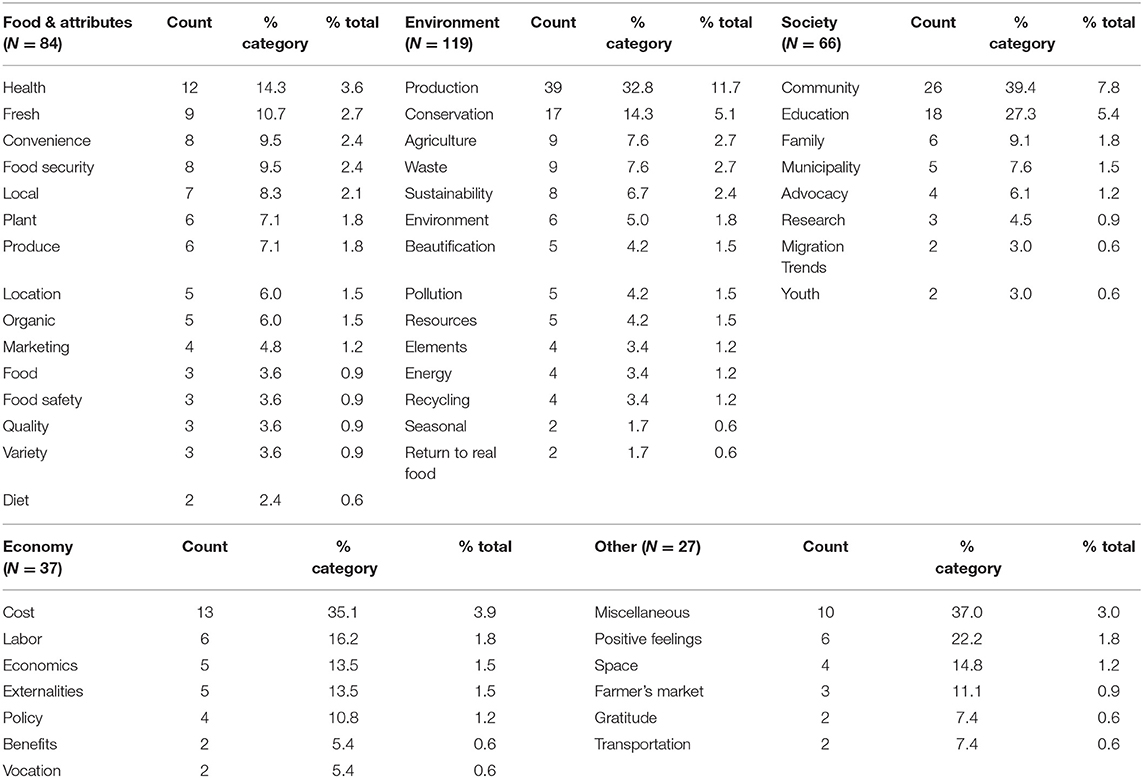

Among the 333 concepts were single terms (e.g., community, convenience, microclimate) and whole phrases [e.g., “Creates ‘villages' (people work together)”]. Following Grebitus et al. (2017) , the concepts were grouped into five categories: Economy, Society, Environment, Food and Attributes, and Other shown in Table 2 . Note, Grebitus et al. (2017) had a sixth category, Point of Sale, but this did not apply to our data. Findings show that participants primarily think of environment-related associations (36%) followed by specific foods and attributes associated with urban farming (25%), and society (20%). The category economy ranks fourth with 11%.

Table 2 . Content categories.

Table 3 shows the associations that were organized in the categories. To reduce the large number of associations, concepts were merged based on similarity using content analysis. For example, “community,” “community centered,” and “community experience” were aggregated up to “community” (see the complete list of associations in Appendix A included in the Supplementary Material). The strongest category, “environment” is dominated by associations related to production (33% of category associations) and conservation (14% of category associations), as well as agriculture (8% of category associations) and waste (8% of category associations). “Sustainability,” “environment,” “beautification,” and “pollution” are also included in this category. The category “food and attributes,” is dominated by associations related to health (14% of category associations) and fresh (11% of category associations), as well as convenience (10% of category associations) and food security (10% of category associations). “Local,” “plant,” and “produce” are also mentioned, as well as, “location” and “organic.” The category “society” is dominated by associations related to community building (39% of category associations), education (27% of category associations), family (9% of category associations) and municipality (8%). “Advocacy,” “research,” “migration trends,” and “youth” also fit this category. The category “economy” is dominated by associations related to cost (35% of category associations) and labor (16% of category associations), as well as economics (14% of category associations) and externalities (14% of category associations). “Policy,” “benefits,” and “vocation” are the remaining associations in this category. The category “other” entails associations, such as “positive feelings” and “gratitude,” that did not fit in the other established categories. Out of all associations, community and sustainability are among those associated most with urban farms. The result that these two concepts are the most prevalent among our responses suggests the importance of environmentally sustainable farms in urban communities.

Table 3 . Results of concept mapping and content analysis.

Overall, findings show that consumers mainly associate production and environmentally related concepts with urban farming. Many food attribute associations can be considered as generally positive, such as “fresh,” “healthy,” “convenient,” “organic,” and “local.” Participants also associate sustainability and conservation with urban farming. They think of social aspects, such as “flourishing neighborhood,” “friend development,” and “meet other gardeners,” when asked about urban farming. Furthermore, urban farming evokes thoughts of “the economy,” “saving money,” “reducing grocery cost,” and “cost effectiveness.” In this regard, we find some differing opinions with some participants believing that they can save money while others consider urban farming is expensive. This is an indicator that urban farming most likely will not be perceived positively by everyone. Some citizens will be in favor of urban farming and others not. This could be resolved using educational measures given that previous studies have shown that individuals do not feel very knowledgeable with regards to urban agriculture ( Grebitus et al., 2017 ).

To get a better understanding of consumer acceptance of urban farming and whether they perceive urban farming as predominantly positive or negative, they were asked to indicate with a plus (+) those associations they think are positive, and with a minus (–) those they consider to be negative. Table 4 summarizes the number of positive and negative evaluations that were given. Appendix A provides a complete list of all associations including the evaluations. As shown in Table 4 , urban farming is mainly perceived as positive. Seventy-three percent (73%) of all associations are evaluated positively while only 15% are evaluated as negative. Less than two percent (1.5%) of the associations fall in the category where individuals felt it could go either way. Except for ID 7, all participants that evaluated their associations have a larger share of positively perceived characteristics. ID 7 has 20% positive and 80% negative associations. Only a small share of associations was left unevaluated. Examples of positive associations are “community,” “environment,” “fresh,” “local,” “green,” “farmer's market,” “healthy,” “organic,” and “sustainability.” Meanwhile, “cost,” “expensive,” “pollution,” “smell,” “possible bacteria,” “disease,” and “pesticides” are examples of negative associations.

Table 4 . Evaluation of Urban farming.

Perception of Urban Farming: Results From Semantic Network Analysis

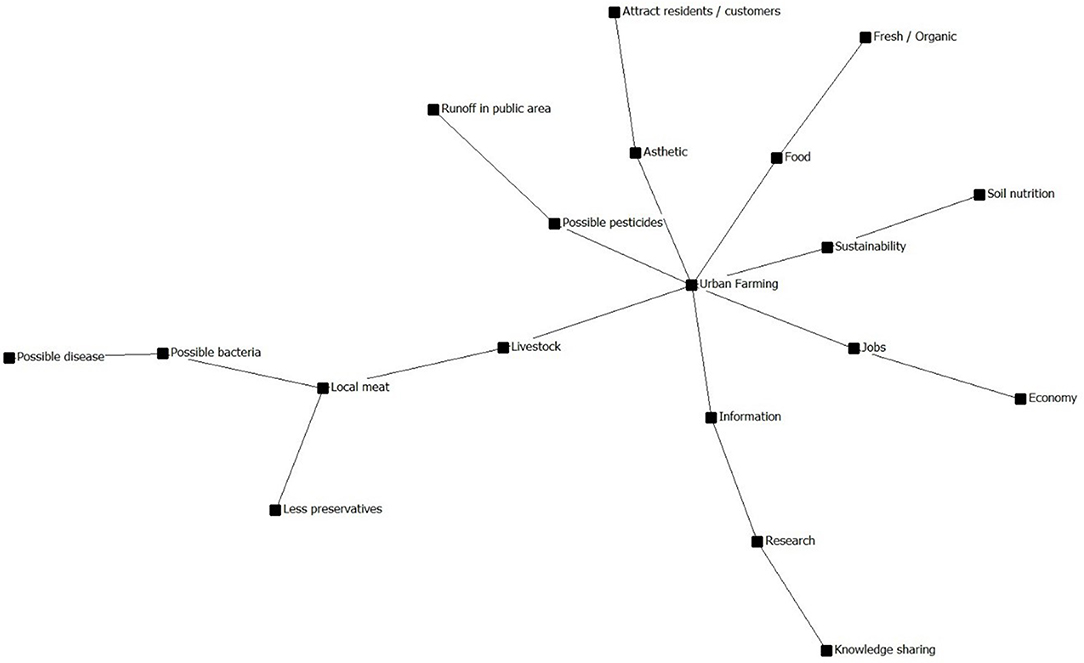

After considering what associations are stored in memory regarding urban farming, this section aims to give insight into how the information is stored and what relationships exist between the stated concepts described in the section Perception of urban farming: Results from content analysis. In this regard, figures 3 through 7 show five different concept maps as examples of semantic networks from five different participants, illustrated by the use of the software UCInet ( Borgatti et al., 2002 ). The concept maps differ in shape and complexity.

Figure 3 is a star-shaped semantic network ( Wasserman and Faust, 1994 ). Based on the spreading activation network theory, this pattern means that when “urban farming” is activated, i.e., the individual thinks about it all related associations will be activated and included in thoughts, evaluations and decision making. In this case, sustainability, jobs, information, livestock, possible pesticides, aesthetic and food. These associations can then lead to further associations if the activation is strong enough. For example, possible pesticides can lead to thoughts about runoff in public areas.

Figure 3 . Example of an individual network 1 (location 1, ID 10).

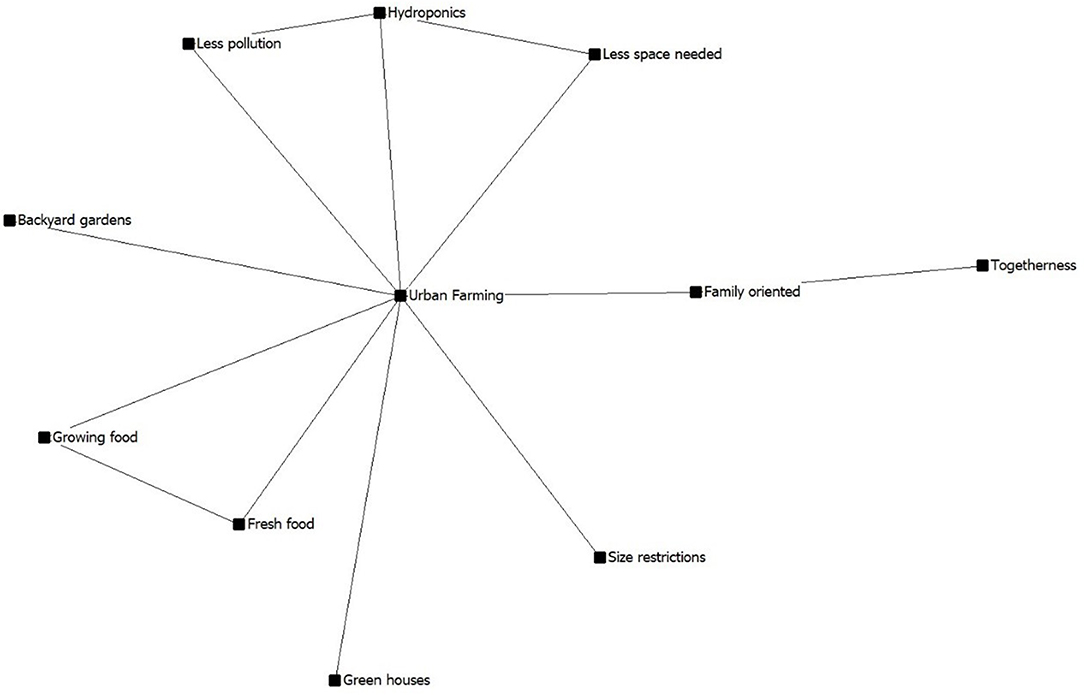

Figure 4 depicts a graph that contains three cycles but is also mainly in a star-shaped composition ( Wasserman and Faust, 1994 ). Here, urban farming is seen as family-oriented, providing fresh food with less pollution and less space, e.g., when using hydroponics.

Figure 4 . Example of an individual network 2 (location 2, ID 19).

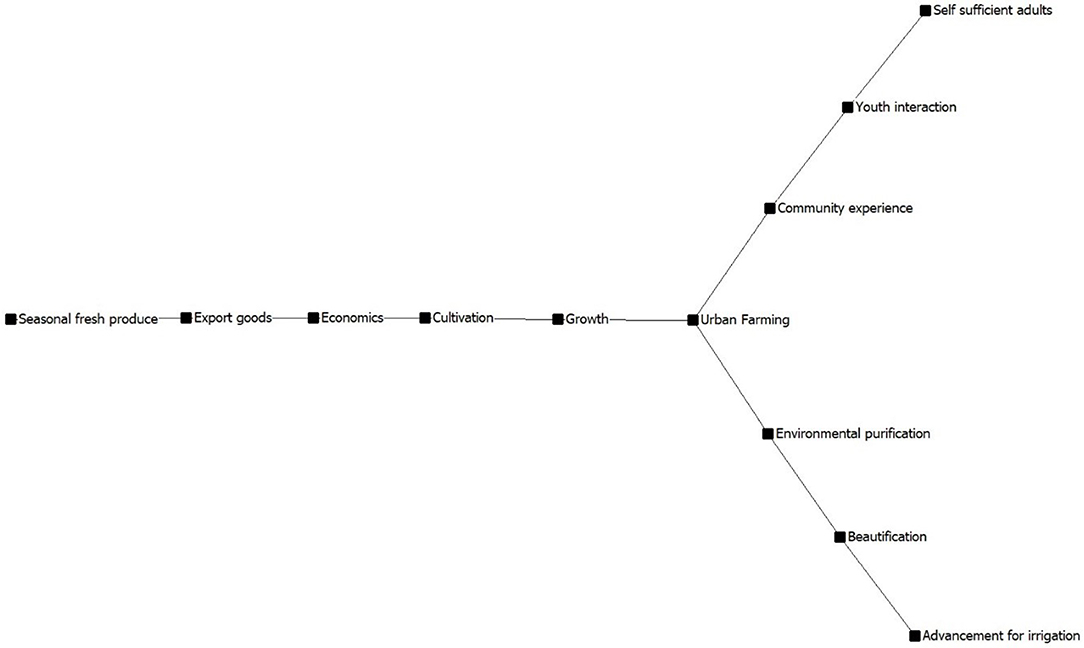

Figure 5 depicts a graph in a tree-shaped composition ( Wasserman and Faust, 1994 ). In this case, more activation is needed to reach associations that are further away from the key stimulus. For example, self-sufficient adults might not be activated, and hence not be included in decisions unless the activation is strong. That said this individual has a semantic network that is more developed in terms of linking associations further. For example, the individual thinks that urban farming is a community experience that can lead to youth interaction, which then should ultimately lead to self-sufficient adults.

Figure 5 . Example of an individual network 3 (location 2, ID 16).

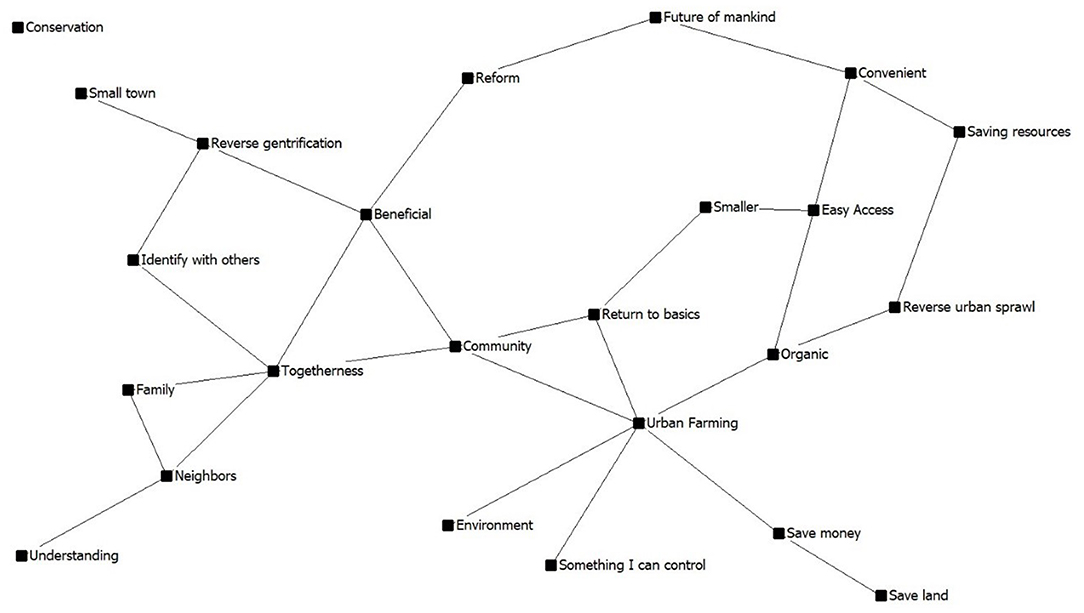

Figure 6 displays a more complex semantic network as displayed by the larger number of associations that are more connected to each other. This individual thinks urban farming can save money, land, and resources in general. The individual also associates organic and easy access, i.e., convenience with urban farming. Community is linked to urban farming and then has links to togetherness and beneficial. Togetherness, in turn, is linked to family and neighbors which are both connected to understanding. This suggests that urban farming could play a role in the communication of people living together, the family and the neighbors.

Figure 6 . Example of an individual network 4 (location 2, ID 17).

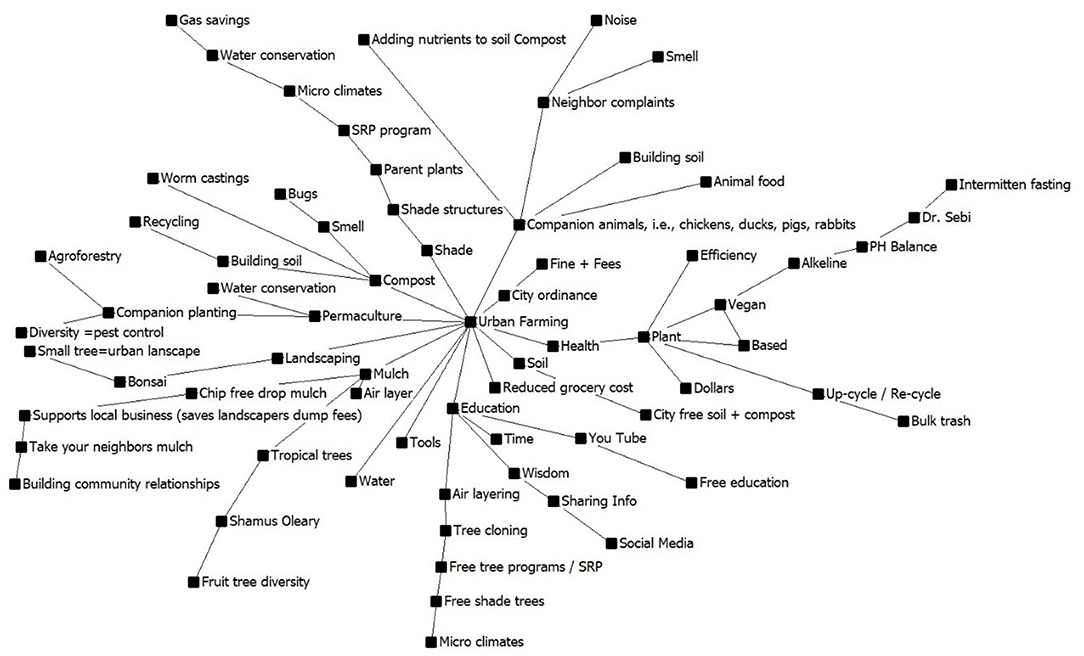

Figure 7 displays the most complex semantic network of the participants with over 60 associations. In this case, a lot of activation would be needed so that the individual would access all stored information regarding urban farming. For example, between intermittent fasting and urban farming, six other associations need to be activated and processed before intermittent fasting is accessed. This individual points out less favorable associations, such as “neighbor complaints,” which are related to “smell” and “noise.” Overall, this concept map is highly differentiated and complex.

Figure 7 . Example of an individual network 5 (location 1, ID 12).

These examples are by no means exhaustive. There is a wide variety of different network structures among the 19 individuals. However, there are few visual differences observed between the concept maps of the two groups in terms of shapes and structures. Each group varies in complexity. Some participants have complex cognitive structures using a great number of associations, while others hold simple cognitive structures, i.e., semantic networks, which can be explained by the use of key information. In this case, urban farming is related to several key associations, so that the activation of a lower amount of stored information is sufficient for its perception. The rather simple network structures can also result from low familiarity with urban farming or a potential lack of interest by some individuals.

Urban agriculture offers a promising opportunity to provide direct access to fresh produce close to urban residents. This may enhance dietary quality and food diversity while addressing consumers' preference for local food. However, urban agriculture will only be successful if it is accepted and perceived positively by those living in close proximity. Therefore, one must account for consumer perception. Hence, our research provides an exploratory analysis of consumer perception regarding urban farming catering to the success of urban agriculture.

To better evaluate consumers' perception, we employ the method of concept mapping in an exploratory and qualitative study of 19 participants from the Phoenix Metropolitan Area. This analysis provided 333 associations with urban farming. Using content analysis, five categories—Environment, Food and Attributes, Society, Economy and Other—were distinguished to group the concepts/associations in a meaningful way. Participants offered a great variety of perceptions, such as organic, local, community, family, agriculture, and sustainability. One of the overarching themes that emerged from our study was the myriad positive perceptions, e.g., fresh, local, and green. Though negative associations exist, e.g., expensive, possible disease, and pollution, these were fewer in comparison. From a marketing standpoint, highlighting those positive aspects of urban agriculture could incite a more favorable perception and willingness to accept urban agriculture. This could also present opportunities for cities to offer incentives to households who do perceive urban farming negatively. The negative associations also deserve further research as they have the potential to deter the further development of urban agriculture.

In terms of individual semantic networks concerning urban farming, we found that there are vast differences regarding how many associations individuals hold and how connected the associations are. Generally, the more associations and the more links in a network the greater the expertise and involvement. Investigating this more deeply could be used to infer educational strategies.

The use of concept mapping offers detailed insight into participants' semantic networks. It serves as an important, theoretically motivated tool to demonstrate what individuals think and how different concepts are related to each other. Individuals' evaluations of positive and negative associations enables the researcher to determine if the researched area (e.g., urban farming) is perceived favorably or not. That said, knowledge structures are complex, and, with increasing sample sizes, analysis on topics that induce many associations – both positive and negative – can quickly become computationally intensive.

This research is not without limitations. While our findings are encouraging toward acceptance of farming in the city, it should be kept in mind that this is an exploratory study. The present study analyzes stored information, i.e., semantic networks regarding urban farming using qualitative methods for a small sample size from only two study locations, so the results might be dependent on the study area. A more robust approach would be sampling from different regions in the U.S. Future research should include a larger number of participants and expand to more study sites. In doing so, recommendations to stakeholders can be made for the successful integration of sustainable urban agriculture. Garnering an understanding of regional perceptions is of importance, as minimizing the length of the supply chain is associated with a number of benefits, especially in resource-limited environments like the Southwest, and improved well-being at the individual level. Future research could examine the multi-scalar dynamics of urban agriculture, shedding light on market opportunities for agricultural producers and regulators, while simultaneously identifying those factors that could lead to market rejection, e.g., consumer reactance, or practices that may reduce the long-term environmental sustainability of the urban farm. Ultimately, there is a need for interdisciplinary research, for instance, between social scientists, economists, and agroecologists to provide insight into different perspectives that underscore the future success and adoption of urban agriculture.

Data Availability Statement

All datasets generated for this study are included in the article/ Supplementary Material .

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Arizona State University IRB, Study Number STUDY00010463. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author Contributions

CG contributed to conception and design of the study, organized the database, performed the analysis, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. LC served as secondary writer of the manuscript and contributed to study design. LC and RM contributed to initial discussions of methods and the review of the concept categorization. RM reviewed and revised the draft for important intellectual content and created Figure 1 . AM contributed to conception and design of the study. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

This work was supported by EASM-3: Collaborative Research: Physics-Based Predictive Modeling for Integrated Agricultural and Urban Applications, USDA-NIFA (Grant Number: 2015-67003-23508), NSF-MPS-DMS (Award Number: 1419593), and by the Swette Center for Sustainable Food Systems, Arizona State University.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fsufs.2020.00079/full#supplementary-material

1. ^ The FAO defines urban agriculture as “a dynamic concept that comprises a variety of livelihood systems ranging from subsistence production and processing at the household level to more commercialized agriculture. It takes place in different locations and under varying socioeconomic conditions and political regimes” ( FAO, 2007 , p. 5).

2. ^ Note the relatively small sample size in this study. While this would be a drawback for a quantitative study targeting to be representative, our objective is to provide an exploratory study on the perception of urban farming. The aim is not to uncover the perception of the whole population. In that case, a method such as concept mapping would not be well-suited, rather one would use free elicitation technique. That said, free elicitation technique does not allow for a depiction of cognitive structures. This could be tackled by future research. In this research, we set out to conduct qualitative research. The sample size for qualitative studies often ranges from 5 to 50 participants, as pointed out by Dworkin (2012) : “An extremely large number of articles, book chapters, and books recommend guidance and suggest anywhere from 5 to 50 participants as adequate.” Participant numbers are similarly small, for example in studies by Sonneville et al. (2009) ; Lachal et al. (2012) ; Bennett et al. (2013) ; Van Gilder and Abdi (2014) ; Takahashi et al. (2016) ; Hunold et al. (2017) , and Mitter et al. (2019) ranging from 12 to 21.

Anderson, J. R. (1983a). Retrieval of information from long-term memory. Science 220, 25–30. doi: 10.1126/science.6828877

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Anderson, J. R. (1983b). A spreading activation theory of memory. J. Verb. Learn. Verb. Behav. 22, 261–295. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5371(83)90201-3

Aragon, N. U., Stuhlmacher, M., Smith, J. P., Clinton, N., and Georgescu, M. (2019). Urban agriculture's bounty: contributions to phoenix's sustainability goals. Environ. Res. Lett. 14:105001. doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/ab428f

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Ares, G., Gámbaro, A., and Giménez, A. (2008). Understanding consumers' perception of conventional and functional yoghurts using word association and hard laddering. Food Qual. Prefer . 19, 636–643. doi: 10.1016/j.foodqual.2008.05.005

Armstrong, D. (2000). A survey of community gardens in upstate New York: implications for health promotion and community development. Health Place 6, 319–327. doi: 10.1016/S1353-8292(00)00013-7

Bennett, J., Greene, G., and Schwartz-Barcott, D. (2013). Perceptions of emotional eating behavior. A qualitative study of college students. Appetite 60, 187–192. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2012.09.023

Bonato, M. (1990). Wissensstrukturierung mittels struktur-lege-techniken, eine graphentheoretische analyse von wissensnetzen, europäische hochschulschriften. Psychologie 6:297.

Borgatti, S. P., Everett, M. G., and Freeman, L. C. (2002). Ucinet for Windows: Software for Social Network Analysis . Harvard, MA: Analytic Technologies.

Brown, K. H., and Jameton, A. L. (2000). Public health implications of urban agriculture. J. Public Health Policy 21, 20–39. doi: 10.2307/3343472

Collins, A. M., and Loftus, E. (1975). A spreading-activation theory of semantic processing. Psychol. Rev . 82, 407–428. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.82.6.407

Cowley, E., and Mitchell, A. (2003). The moderating effect of product knowledge on the learning and organization of product information. J. Consum. Res . 30, 443–454. doi: 10.1086/378620

DeHaan, L. R. (2015). “Perennial crops are a key to sustainably productive agriculture,” in Food Security: Production and Sustainability . Institute on Science for Global Policy, ISGP Academic Partnership with Eckerd College. Available online at: https://www.scienceforglobalpolicy.org (accessed May, 2020).

Google Scholar

Dimitri, C., Oberholtzer, L., and Pressman, A. (2016). Urban agriculture: connecting producers with consumers. Br. Food J. 118, 603–617. doi: 10.1108/BFJ-06-2015-0200

Dworkin, S. L. (2012). Sample size policy for qualitative studies using in-depth interviews. Arch. Sex. Behav. 41, 1319–1320. doi: 10.1007/s10508-012-0016-6

FAO (2007). Profitability and Sustainability of Urban and Peri-urban Agriculture . Agricultural Management, Marketing and Finance Occasional Paper 19.

Firth, C., Maye, D., and Pearson, D. (2011). Developing “community” in community gardens. Local Environ. 16, 555–568. doi: 10.1080/13549839.2011.586025

Freedman, D. A., Vaudrin, N., Schneider, C., Trapl, E., Ohri-Vachaspati, P., and Taggart, M‘. (2016). Systematic review of factors influencing farmers' market use overall and among low-income populations. J. Acad. Nutr. Dietetics 116, 1136–1155. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2016.02.010

Grebitus, C. (2008): Food Quality from the Consumer's Perspective - An Empirical Analysis of Perceived Pork Quality . Göttingen: Cuvillier Publisher.

Grebitus, C., and Bruhn, M. (2008). Analysing semantic networks of pork quality by means of concept mapping. Food Qual. Prefer. 19, 86–96. doi: 10.1016/j.foodqual.2007.07.007

Grebitus, C., Printezis, I., and Printezis, A. (2017). Relationship between consumer behavior and success of urban agriculture. Ecol. Econ. 136, 189–200. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2017.02.010

Grunert, K. G., and Bech-Larsen, T. (2005). Explaining choice option attractiveness by beliefs elicited by the laddering method. J. Econ. Psychol. 26, 223–241. doi: 10.1016/j.joep.2004.04.002

Henderson, G. R., Iacobucci, D., and Calder, B. J. (1998). Brand diagnostics: mapping branding effects using consumer associative networks. Eur. J. Operat . Res. 111, 306–327. doi: 10.1016/S0377-2217(98)00151-9

Hsia, H. J. (1988). “Mass communications research methods: a step-by-step approach,” in Communication Textbook Series. Mass Communication , eds J. Bryant and A. M. Rubin (Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.).

Hughes, D.W., and Boys, K. A. (2015). What we know and don't know about the economic development benefits of local food systems . Choices 1–6 . Available online at: http://choicesmagazine.org/choices-magazine/theme-articles/community-economics-of-local-foods/what-we-know-and-dont-know-about-the-economic-development-benefits-of-local-food-systems (accessed May, 2020).

Hunold, C., Sorunmu, Y., Lindy, R., Spatari, S., and Gurian, P. (2017). Is urban agriculture financially sustainable? An exploratory study of small-scale market farming in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. J. Agric. Food Syst. Commun. Dev. 7, 51–67. doi: 10.5304/jafscd.2017.072.012

Joiner, C. (1998). Concept mapping in marketing: a research tool for uncovering consumers' knowledge structure associations. Adv. Consum. Res. 25, 311–317.

Jonassen, D. H., Beissner, K., and Yacci, M. (1993). Structural Knowledge: Techniques for Representing, Conveying and Acquiring Structural Knowledge . Hillsdale, NJ: Routledge.

Kanwar, R., Olson, J. C., and Sims, L. S. (1981). Toward conceptualizing and measuring cognitive structures. Adv. Consum. Res. 8, 122–127.

Kroeber-Riel, W., Weinberg, P., and Gröppel-Klein, A. (2009). Konsumentenverhalten, 9th Edn . München: Vahlen.

Lachal, J., Speranza, M., Taïeb, O., Falissard, B., Lefèvre, H., Moro, M. R., and Revah-Levy, A. Q. (2012). Qualitative research using photo-elicitation to explore the role of food in family relationships among obese adolescents. Appetite 58, 1099–1105. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2012.02.045

Lamnek, S. (1995). Qualitative Sozialforschung. Band 2: Methoden und Techniken, 3rd Edn. Weinheim Verlag.

Martin, J. (1985). Measuring clients' cognitive competence in research on counseling. J. Couns. Dev. 63, 556–560. doi: 10.1002/j.1556-6676.1985.tb00680.x

Mayring, P. (2002). Einführung in die Qualitative Sozialforschung. Eine Anleitung zu Qualitativem Denken, 5th Edn . Weinheim: Beltz Studium.

Mitter, H., Larcher, M., Schönhart, M., Stöttinger, M., and Schmid, E. (2019). Exploring farmers' climate change perceptions and adaptation intentions: empirical evidence from Austria. Environ. Manag. 63, 804–821. doi: 10.1007/s00267-019-01158-7

Mougeot, L. J. (Ed.). (2005). Agropolis: The Social, Political, and Environmental Dimensions of Urban Agriculture . London: IDRC.

Olson, J. C. (1978). Inferential belief formation in the cue utilization process. Adv. Consum. Res . 5, 706–713.

Olson, J. C., and Muderrisoglu, A. (1979). The stability of responses obtained by free elicitation: implications for measuring attribute salience and memory structures. Adv. Consum . Res. 6, 269–275.

Peter, J. P., and Olson, J. C. (2008). Consumer Behavior and Marketing Strategy, 8th Edn. New York, NY: Mcgraw-Hill/Irwin Series in Marketing.

Printezis, I., and Grebitus, C. (2018). Marketing channels for local food. Ecol. Econ. 152, 161–171. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2018.05.021

Roininen, K., Arvola, A., and Lähteenmäki, L. (2006). Exploring consumers' perceptions of local food with two different qualitative techniques: laddering and word association. Food Qual. Prefer. 17, 20–30. doi: 10.1016/j.foodqual.2005.04.012

Russell, C., and Cox, D. (2004). Understanding middle-aged consumers' perception of meat using repertory grid methodology. Food Qual. Prefer. 15, 317–329. doi: 10.1016/S0950-3293(03)00073-9

Rye, J. A., and Rubba, P. A. (1998). An exploration of the concept map as an interview tool to facilitate the externalization of students' understandings about global atmospheric change. J. Res. Sci. Teach . 35, 521–546. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2736(199805)35:5<521::AID-TEA4>3.0.CO2-R

Sadler, R. C. (2016). Strengthening the core, improving access: bringing healthy food downtown via a farmers' market move. Appl. Geogr. 67, 119–128. doi: 10.1016/j.apgeog.2015.12.010

Sampson, P. (1972). Using the repertory grid test. J. Market. Res . 9, 78–81. doi: 10.1177/002224377200900117

Satterthwaite, D., McGranahan, G., and Tacoli, C. (2010). Urbanization and its implications for food and farming. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. Series B Biol. Sci. 365, 2809–2820. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2010.0136

Shrestha, M. K., York, A. M., Boone, C. G., and Zhang, S. (2012). Land fragmentation due to rapid urbanization in the phoenix metropolitan area: analyzing the spatiotemporal patterns and drivers. Appl. Geogr. 32, 522–531. doi: 10.1016/j.apgeog.2011.04.004

Smith, J. P., Li, X., and Turner, B. L. (2017). Lots for greening: identification of metropolitan vacant land and its potential use for cooling and agriculture in phoenix, AZ, USA. Appl. Geogr. 85, 139–151. doi: 10.1016/j.apgeog.2017.06.005

Sonneville, K. R., La Pelle, N., Taveras, E. M., Gillman, M. W., and Prosser, L. A. (2009). Economic and other barriers to adopting recommendations to prevent childhood obesity: results of a focus group study with parents. BMC Pediatr 9:81. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-9-81

Stempel, G. H. III. (1981). “Content analysis,” in Research Methods in Mass Communication , eds G. H. Stempel III and B. H. Westley (New Jersey, NY: Prentice-Hall, Inc.).

Surls, R., Feenstra, G., Golden, S., Galt, R., Hardesty, S., Napawan, C., et al. (2015). Gearing up to support urban farming in California: preliminary results of a needs assessment. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 30, 33–42. doi: 10.1017/S1742170514000052

Takahashi, B., Burnham, M., Terracina-Hartman, C., Sopchak, A. R., and Selfa, T. (2016). Climate change perceptions of NY state farmers: the role of risk perceptions and adaptive capacity. Environ. Manag. 58, 946–957. doi: 10.1007/s00267-016-0742-y

U.S. Census Bureau (2019). Annual Estimates of the Resident Population. American FactFinder . Available online at: https://www.factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.%20xhtml?src=CF (accessed February 10, 2019).

United Nations (2018). 68% of the World Population Projected to live in Urban Areas by 2050, Says UN. Available online at: https://www.un.org/development/desa/en/news/population/2018-revision-of-world-urbanization-prospects.html (accessed April 12, 2019).

Van Gilder, B., and Abdi, S. (2014). Identity management and the fostering of network ignorance: accounts of queer Iranian women in the United States. J. Intercult. Commun. Res. 43, 151–170. doi: 10.1080/17475759.2014.892895

Wakefield, S., Yeudall, F., Taron, C., Reynolds, J., and Skinner, A. (2007). Growing urban health: community gardening in South-East Toronto. Health Promot. Int. 22, 92–101. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dam001

Warren, E., Hawkesworth, S., and Knai, C. (2015). Investigating the association between urban agriculture and food security, dietary diversity, and nutritional status: a systematic literature review. Food Policy 53, 54–66. doi: 10.1016/j.foodpol.2015.03.004

Wasserman, S., and Faust, K. (1994). Social Network Analysis: Methods and Applications. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511815478

WHO (2018). WHO . Available online at: http://www.who.int/elena/titles/fruit_vegetables_ncds/en/ (accessed August 23, 2018).

Wielemaker, R., Oenema, O., Zeeman, G., and Weijma, J. (2019). Fertile cities: nutrient management practices in urban agriculture. Sci. Total Environ. 668, 1277–1288. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.02.424

Wimmer, R. D., and Dominick, J. R. (1983). “Mass media research. An introduction,” in Wadsworth Series in Mass Communication , ed R. Hayden (Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing Company).

World Bank (2016). Urban Population (% of total) . Available online at: https://www.data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.URB.TOTL.IN.ZS (accessed January 15, 2017).

Wortman, S. E., and Lovell, S. T. (2013). Environmental challenges threatening the growth of urban agriculture in the United States. J. Environ. Qual. 42, 1283–1294. doi: 10.2134/jeq2013.01.0031

Zezza, A., and Tasciotti, L. (2010). Urban agriculture, poverty, and food security: empirical evidence from a sample of developing countries. Food Policy 35, 265–273. doi: 10.1016/j.foodpol.2010.04.007

Zsambok, C. E. (1993). Implications of a recognitional decision model for consumer behavior. Adv. Consum. Res. 20, 239–244.

Keywords: cognitive structures, concept mapping, exploratory, semantic network, urban agriculture

Citation: Grebitus C, Chenarides L, Muenich R and Mahalov A (2020) Consumers' Perception of Urban Farming—An Exploratory Study. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 4:79. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2020.00079

Received: 22 December 2019; Accepted: 01 May 2020; Published: 12 June 2020.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2020 Grebitus, Chenarides, Muenich and Mahalov. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Carola Grebitus, carola.grebitus@asu.edu

This article is part of the Research Topic

Current Status and Trends in Urban Agriculture

Urban Agriculture from a Historical Perspective

- First Online: 10 June 2022

Cite this chapter

- Teresa Marat-Mendes 5 ,

- Sara Silva Lopes 6 ,

- João Cunha Borges 7 &

- Patrícia Bento d’Almeida 8

322 Accesses

the landscape This chapter presents, through a literature review, an operative definition of urban agriculture, to serve as a basis for a survey, conducted by the authors of this Atlas, on all the municipalities of the Lisbon Region. Moreover, we present a methodology for surveying and classifying examples of this practice.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

This is Alves Redol’s description of the landscape of the Tagus Wetland, whose southern end is the Great Wetland in Vila Franca de Xira.

Aben R, de Wit (1999) The enclosed garden. History and development of the Hortus Conclusus and its reintroduction into the present-day urban landscape. Nai010 publishers, Amsterdam

Google Scholar

Abusaada H, Elshater A (2020) COVID-19’s challenges to urbanism: social distancing and the phenomenon of boredom in urban spaces. J Urban. https://doi.org/10.1080/17549175.2020.1842484

Article Google Scholar

Ashe LM, Sonnino R (2013) At the crossroads: new paradigms of food security, public health nutrition and school food. Public Health Nutr 16(6):1020–1027

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Barthes R (1971 [2009]) Sade Fourier Loyla. Points, Paris

Cabannes Y, Raposo I (2013) Peri-urban agriculture, social inclusion of migrant population and Right to the City—Practices in Lisbon and London. City 17(29):235–250. https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2013.765652

Costa S, Fox-Kämper R, GoodR, Sentić I, Treija S, Atanasovska JR, Bonnavaud H (2016) The position of urban allotment gardens within the urban fabric. In: Bell S, Fox-Kämper R, Keshavarz N, Benson M, Caputo S, Noori S, Voigt A (eds) Urban allotment gardens in Europe. Routledge, London, pp 201–228

Deakin M, Diamantini D, Borrelli N (eds) (2016) The governance of city food systems: case studies from around the world. Fondazione Giangiacomo Feltrine, Milan

Delgado C (2018) Contrasting practices and perceptions of urban agriculture in Portugal. Int J Urban Sustain Develop 10:170–185

Dias AM, Marat-Mendes T (2020) The morphological impact of municipal planning instruments on urban agriculture. Cidades, Comunidades & Territórios 41. http://journals.openedition.org/cidades/2991