A Guide to Literature Reviews

Importance of a good literature review.

- Conducting the Literature Review

- Structure and Writing Style

- Types of Literature Reviews

- Citation Management Software This link opens in a new window

- Acknowledgements

A literature review is not only a summary of key sources, but has an organizational pattern which combines both summary and synthesis, often within specific conceptual categories . A summary is a recap of the important information of the source, but a synthesis is a re-organization, or a reshuffling, of that information in a way that informs how you are planning to investigate a research problem. The analytical features of a literature review might:

- Give a new interpretation of old material or combine new with old interpretations,

- Trace the intellectual progression of the field, including major debates,

- Depending on the situation, evaluate the sources and advise the reader on the most pertinent or relevant research, or

- Usually in the conclusion of a literature review, identify where gaps exist in how a problem has been researched to date.

The purpose of a literature review is to:

- Place each work in the context of its contribution to understanding the research problem being studied.

- Describe the relationship of each work to the others under consideration.

- Identify new ways to interpret prior research.

- Reveal any gaps that exist in the literature.

- Resolve conflicts amongst seemingly contradictory previous studies.

- Identify areas of prior scholarship to prevent duplication of effort.

- Point the way in fulfilling a need for additional research.

- Locate your own research within the context of existing literature [very important].

- << Previous: Definition

- Next: Conducting the Literature Review >>

- Last Updated: May 10, 2024 11:34 AM

- URL: https://libguides.mcmaster.ca/litreview

Why is it important to do a literature review in research?

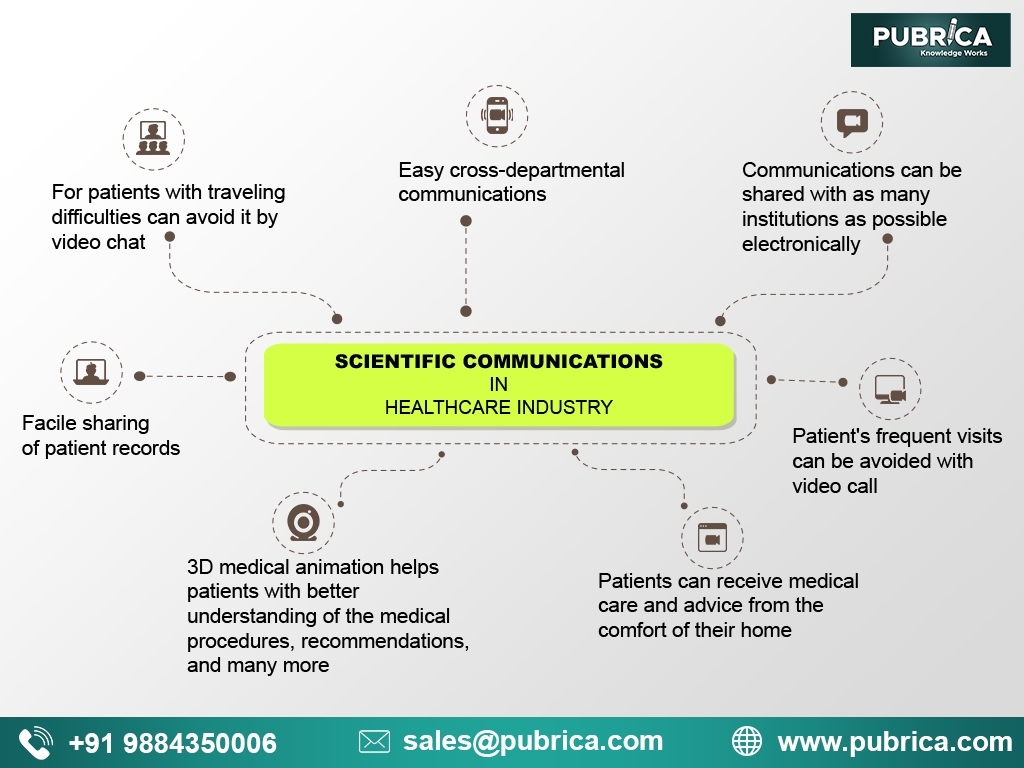

The importance of scientific communication in the healthcare industry

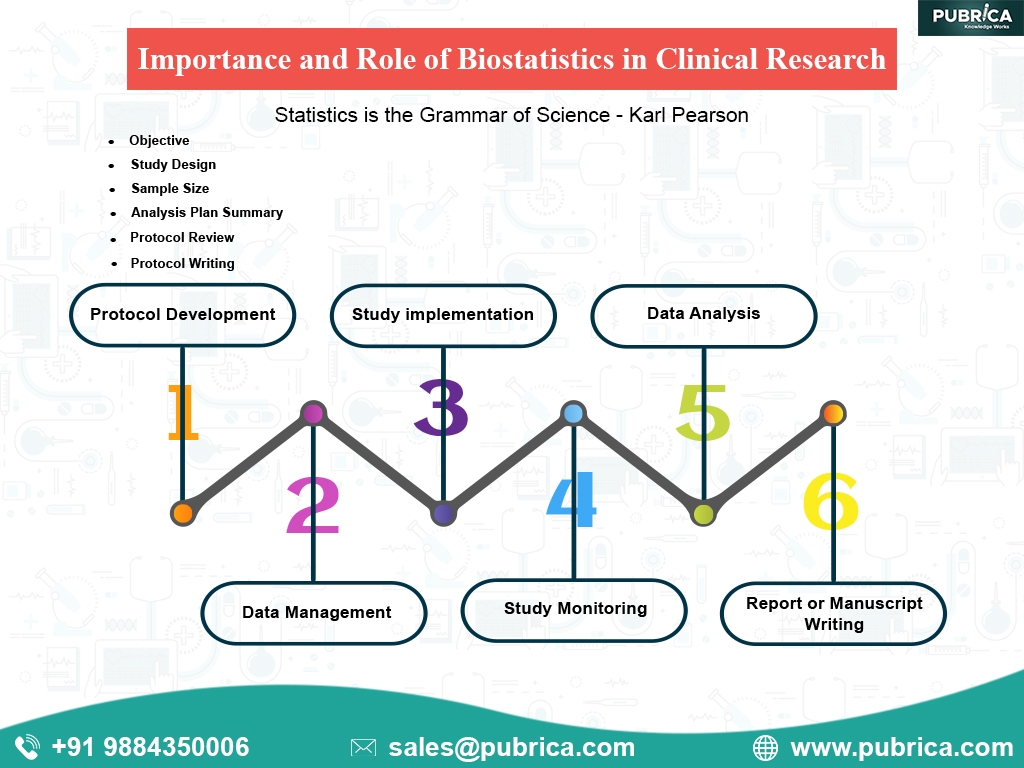

The Importance and Role of Biostatistics in Clinical Research

“A substantive, thorough, sophisticated literature review is a precondition for doing substantive, thorough, sophisticated research”. Boote and Baile 2005

Authors of manuscripts treat writing a literature review as a routine work or a mere formality. But a seasoned one knows the purpose and importance of a well-written literature review. Since it is one of the basic needs for researches at any level, they have to be done vigilantly. Only then the reader will know that the basics of research have not been neglected.

The aim of any literature review is to summarize and synthesize the arguments and ideas of existing knowledge in a particular field without adding any new contributions. Being built on existing knowledge they help the researcher to even turn the wheels of the topic of research. It is possible only with profound knowledge of what is wrong in the existing findings in detail to overpower them. For other researches, the literature review gives the direction to be headed for its success.

The common perception of literature review and reality:

As per the common belief, literature reviews are only a summary of the sources related to the research. And many authors of scientific manuscripts believe that they are only surveys of what are the researches are done on the chosen topic. But on the contrary, it uses published information from pertinent and relevant sources like

- Scholarly books

- Scientific papers

- Latest studies in the field

- Established school of thoughts

- Relevant articles from renowned scientific journals

and many more for a field of study or theory or a particular problem to do the following:

- Summarize into a brief account of all information

- Synthesize the information by restructuring and reorganizing

- Critical evaluation of a concept or a school of thought or ideas

- Familiarize the authors to the extent of knowledge in the particular field

- Encapsulate

- Compare & contrast

By doing the above on the relevant information, it provides the reader of the scientific manuscript with the following for a better understanding of it:

- It establishes the authors’ in-depth understanding and knowledge of their field subject

- It gives the background of the research

- Portrays the scientific manuscript plan of examining the research result

- Illuminates on how the knowledge has changed within the field

- Highlights what has already been done in a particular field

- Information of the generally accepted facts, emerging and current state of the topic of research

- Identifies the research gap that is still unexplored or under-researched fields

- Demonstrates how the research fits within a larger field of study

- Provides an overview of the sources explored during the research of a particular topic

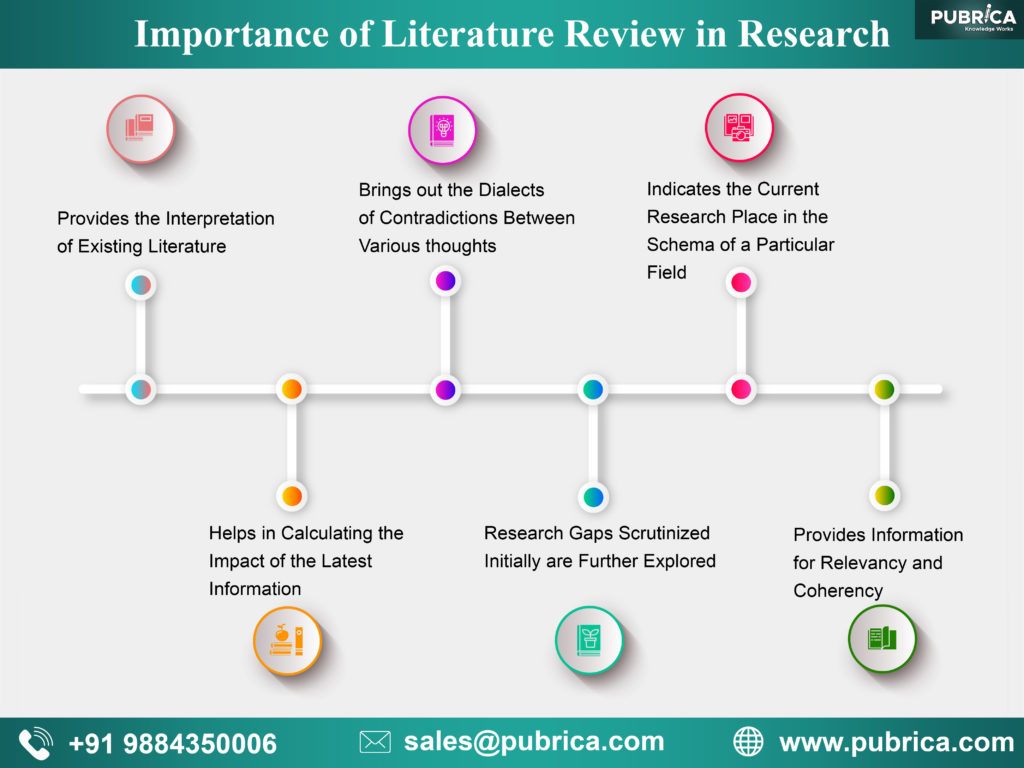

Importance of literature review in research:

The importance of literature review in scientific manuscripts can be condensed into an analytical feature to enable the multifold reach of its significance. It adds value to the legitimacy of the research in many ways:

- Provides the interpretation of existing literature in light of updated developments in the field to help in establishing the consistency in knowledge and relevancy of existing materials

- It helps in calculating the impact of the latest information in the field by mapping their progress of knowledge.

- It brings out the dialects of contradictions between various thoughts within the field to establish facts

- The research gaps scrutinized initially are further explored to establish the latest facts of theories to add value to the field

- Indicates the current research place in the schema of a particular field

- Provides information for relevancy and coherency to check the research

- Apart from elucidating the continuance of knowledge, it also points out areas that require further investigation and thus aid as a starting point of any future research

- Justifies the research and sets up the research question

- Sets up a theoretical framework comprising the concepts and theories of the research upon which its success can be judged

- Helps to adopt a more appropriate methodology for the research by examining the strengths and weaknesses of existing research in the same field

- Increases the significance of the results by comparing it with the existing literature

- Provides a point of reference by writing the findings in the scientific manuscript

- Helps to get the due credit from the audience for having done the fact-finding and fact-checking mission in the scientific manuscripts

- The more the reference of relevant sources of it could increase more of its trustworthiness with the readers

- Helps to prevent plagiarism by tailoring and uniquely tweaking the scientific manuscript not to repeat other’s original idea

- By preventing plagiarism , it saves the scientific manuscript from rejection and thus also saves a lot of time and money

- Helps to evaluate, condense and synthesize gist in the author’s own words to sharpen the research focus

- Helps to compare and contrast to show the originality and uniqueness of the research than that of the existing other researches

- Rationalizes the need for conducting the particular research in a specified field

- Helps to collect data accurately for allowing any new methodology of research than the existing ones

- Enables the readers of the manuscript to answer the following questions of its readers for its better chances for publication

- What do the researchers know?

- What do they not know?

- Is the scientific manuscript reliable and trustworthy?

- What are the knowledge gaps of the researcher?

22. It helps the readers to identify the following for further reading of the scientific manuscript:

- What has been already established, discredited and accepted in the particular field of research

- Areas of controversy and conflicts among different schools of thought

- Unsolved problems and issues in the connected field of research

- The emerging trends and approaches

- How the research extends, builds upon and leaves behind from the previous research

A profound literature review with many relevant sources of reference will enhance the chances of the scientific manuscript publication in renowned and reputed scientific journals .

References:

http://www.math.montana.edu/jobo/phdprep/phd6.pdf

journal Publishing services | Scientific Editing Services | Medical Writing Services | scientific research writing service | Scientific communication services

Related Topics:

Meta Analysis

Scientific Research Paper Writing

Medical Research Paper Writing

Scientific Communication in healthcare

pubrica academy

Related posts.

Statistical analyses of case-control studies

PUB - Selecting material (e.g. excipient, active pharmaceutical ingredient) for drug development

Selecting material (e.g. excipient, active pharmaceutical ingredient, packaging material) for drug development

PUB - Health Economics of Data Modeling

Health economics in clinical trials

Comments are closed.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Grad Med Educ

- v.8(3); 2016 Jul

The Literature Review: A Foundation for High-Quality Medical Education Research

a These are subscription resources. Researchers should check with their librarian to determine their access rights.

Despite a surge in published scholarship in medical education 1 and rapid growth in journals that publish educational research, manuscript acceptance rates continue to fall. 2 Failure to conduct a thorough, accurate, and up-to-date literature review identifying an important problem and placing the study in context is consistently identified as one of the top reasons for rejection. 3 , 4 The purpose of this editorial is to provide a road map and practical recommendations for planning a literature review. By understanding the goals of a literature review and following a few basic processes, authors can enhance both the quality of their educational research and the likelihood of publication in the Journal of Graduate Medical Education ( JGME ) and in other journals.

The Literature Review Defined

In medical education, no organization has articulated a formal definition of a literature review for a research paper; thus, a literature review can take a number of forms. Depending on the type of article, target journal, and specific topic, these forms will vary in methodology, rigor, and depth. Several organizations have published guidelines for conducting an intensive literature search intended for formal systematic reviews, both broadly (eg, PRISMA) 5 and within medical education, 6 and there are excellent commentaries to guide authors of systematic reviews. 7 , 8

- A literature review forms the basis for high-quality medical education research and helps maximize relevance, originality, generalizability, and impact.

- A literature review provides context, informs methodology, maximizes innovation, avoids duplicative research, and ensures that professional standards are met.

- Literature reviews take time, are iterative, and should continue throughout the research process.

- Researchers should maximize the use of human resources (librarians, colleagues), search tools (databases/search engines), and existing literature (related articles).

- Keeping organized is critical.

Such work is outside the scope of this article, which focuses on literature reviews to inform reports of original medical education research. We define such a literature review as a synthetic review and summary of what is known and unknown regarding the topic of a scholarly body of work, including the current work's place within the existing knowledge . While this type of literature review may not require the intensive search processes mandated by systematic reviews, it merits a thoughtful and rigorous approach.

Purpose and Importance of the Literature Review

An understanding of the current literature is critical for all phases of a research study. Lingard 9 recently invoked the “journal-as-conversation” metaphor as a way of understanding how one's research fits into the larger medical education conversation. As she described it: “Imagine yourself joining a conversation at a social event. After you hang about eavesdropping to get the drift of what's being said (the conversational equivalent of the literature review), you join the conversation with a contribution that signals your shared interest in the topic, your knowledge of what's already been said, and your intention.” 9

The literature review helps any researcher “join the conversation” by providing context, informing methodology, identifying innovation, minimizing duplicative research, and ensuring that professional standards are met. Understanding the current literature also promotes scholarship, as proposed by Boyer, 10 by contributing to 5 of the 6 standards by which scholarly work should be evaluated. 11 Specifically, the review helps the researcher (1) articulate clear goals, (2) show evidence of adequate preparation, (3) select appropriate methods, (4) communicate relevant results, and (5) engage in reflective critique.

Failure to conduct a high-quality literature review is associated with several problems identified in the medical education literature, including studies that are repetitive, not grounded in theory, methodologically weak, and fail to expand knowledge beyond a single setting. 12 Indeed, medical education scholars complain that many studies repeat work already published and contribute little new knowledge—a likely cause of which is failure to conduct a proper literature review. 3 , 4

Likewise, studies that lack theoretical grounding or a conceptual framework make study design and interpretation difficult. 13 When theory is used in medical education studies, it is often invoked at a superficial level. As Norman 14 noted, when theory is used appropriately, it helps articulate variables that might be linked together and why, and it allows the researcher to make hypotheses and define a study's context and scope. Ultimately, a proper literature review is a first critical step toward identifying relevant conceptual frameworks.

Another problem is that many medical education studies are methodologically weak. 12 Good research requires trained investigators who can articulate relevant research questions, operationally define variables of interest, and choose the best method for specific research questions. Conducting a proper literature review helps both novice and experienced researchers select rigorous research methodologies.

Finally, many studies in medical education are “one-offs,” that is, single studies undertaken because the opportunity presented itself locally. Such studies frequently are not oriented toward progressive knowledge building and generalization to other settings. A firm grasp of the literature can encourage a programmatic approach to research.

Approaching the Literature Review

Considering these issues, journals have a responsibility to demand from authors a thoughtful synthesis of their study's position within the field, and it is the authors' responsibility to provide such a synthesis, based on a literature review. The aforementioned purposes of the literature review mandate that the review occurs throughout all phases of a study, from conception and design, to implementation and analysis, to manuscript preparation and submission.

Planning the literature review requires understanding of journal requirements, which vary greatly by journal ( table 1 ). Authors are advised to take note of common problems with reporting results of the literature review. Table 2 lists the most common problems that we have encountered as authors, reviewers, and editors.

Sample of Journals' Author Instructions for Literature Reviews Conducted as Part of Original Research Article a

Common Problem Areas for Reporting Literature Reviews in the Context of Scholarly Articles

Locating and Organizing the Literature

Three resources may facilitate identifying relevant literature: human resources, search tools, and related literature. As the process requires time, it is important to begin searching for literature early in the process (ie, the study design phase). Identifying and understanding relevant studies will increase the likelihood of designing a relevant, adaptable, generalizable, and novel study that is based on educational or learning theory and can maximize impact.

Human Resources

A medical librarian can help translate research interests into an effective search strategy, familiarize researchers with available information resources, provide information on organizing information, and introduce strategies for keeping current with emerging research. Often, librarians are also aware of research across their institutions and may be able to connect researchers with similar interests. Reaching out to colleagues for suggestions may help researchers quickly locate resources that would not otherwise be on their radar.

During this process, researchers will likely identify other researchers writing on aspects of their topic. Researchers should consider searching for the publications of these relevant researchers (see table 3 for search strategies). Additionally, institutional websites may include curriculum vitae of such relevant faculty with access to their entire publication record, including difficult to locate publications, such as book chapters, dissertations, and technical reports.

Strategies for Finding Related Researcher Publications in Databases and Search Engines

Search Tools and Related Literature

Researchers will locate the majority of needed information using databases and search engines. Excellent resources are available to guide researchers in the mechanics of literature searches. 15 , 16

Because medical education research draws on a variety of disciplines, researchers should include search tools with coverage beyond medicine (eg, psychology, nursing, education, and anthropology) and that cover several publication types, such as reports, standards, conference abstracts, and book chapters (see the box for several information resources). Many search tools include options for viewing citations of selected articles. Examining cited references provides additional articles for review and a sense of the influence of the selected article on its field.

Box Information Resources

- Web of Science a

- Education Resource Information Center (ERIC)

- Cumulative Index of Nursing & Allied Health (CINAHL) a

- Google Scholar

Once relevant articles are located, it is useful to mine those articles for additional citations. One strategy is to examine references of key articles, especially review articles, for relevant citations.

Getting Organized

As the aforementioned resources will likely provide a tremendous amount of information, organization is crucial. Researchers should determine which details are most important to their study (eg, participants, setting, methods, and outcomes) and generate a strategy for keeping those details organized and accessible. Increasingly, researchers utilize digital tools, such as Evernote, to capture such information, which enables accessibility across digital workspaces and search capabilities. Use of citation managers can also be helpful as they store citations and, in some cases, can generate bibliographies ( table 4 ).

Citation Managers

Knowing When to Say When

Researchers often ask how to know when they have located enough citations. Unfortunately, there is no magic or ideal number of citations to collect. One strategy for checking coverage of the literature is to inspect references of relevant articles. As researchers review references they will start noticing a repetition of the same articles with few new articles appearing. This can indicate that the researcher has covered the literature base on a particular topic.

Putting It All Together

In preparing to write a research paper, it is important to consider which citations to include and how they will inform the introduction and discussion sections. The “Instructions to Authors” for the targeted journal will often provide guidance on structuring the literature review (or introduction) and the number of total citations permitted for each article category. Reviewing articles of similar type published in the targeted journal can also provide guidance regarding structure and average lengths of the introduction and discussion sections.

When selecting references for the introduction consider those that illustrate core background theoretical and methodological concepts, as well as recent relevant studies. The introduction should be brief and present references not as a laundry list or narrative of available literature, but rather as a synthesized summary to provide context for the current study and to identify the gap in the literature that the study intends to fill. For the discussion, citations should be thoughtfully selected to compare and contrast the present study's findings with the current literature and to indicate how the present study moves the field forward.

To facilitate writing a literature review, journals are increasingly providing helpful features to guide authors. For example, the resources available through JGME include several articles on writing. 17 The journal Perspectives on Medical Education recently launched “The Writer's Craft,” which is intended to help medical educators improve their writing. Additionally, many institutions have writing centers that provide web-based materials on writing a literature review, and some even have writing coaches.

The literature review is a vital part of medical education research and should occur throughout the research process to help researchers design a strong study and effectively communicate study results and importance. To achieve these goals, researchers are advised to plan and execute the literature review carefully. The guidance in this editorial provides considerations and recommendations that may improve the quality of literature reviews.

- UConn Library

- Literature Review: The What, Why and How-to Guide

- Introduction

Literature Review: The What, Why and How-to Guide — Introduction

- Getting Started

- How to Pick a Topic

- Strategies to Find Sources

- Evaluating Sources & Lit. Reviews

- Tips for Writing Literature Reviews

- Writing Literature Review: Useful Sites

- Citation Resources

- Other Academic Writings

What are Literature Reviews?

So, what is a literature review? "A literature review is an account of what has been published on a topic by accredited scholars and researchers. In writing the literature review, your purpose is to convey to your reader what knowledge and ideas have been established on a topic, and what their strengths and weaknesses are. As a piece of writing, the literature review must be defined by a guiding concept (e.g., your research objective, the problem or issue you are discussing, or your argumentative thesis). It is not just a descriptive list of the material available, or a set of summaries." Taylor, D. The literature review: A few tips on conducting it . University of Toronto Health Sciences Writing Centre.

Goals of Literature Reviews

What are the goals of creating a Literature Review? A literature could be written to accomplish different aims:

- To develop a theory or evaluate an existing theory

- To summarize the historical or existing state of a research topic

- Identify a problem in a field of research

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1997). Writing narrative literature reviews . Review of General Psychology , 1 (3), 311-320.

What kinds of sources require a Literature Review?

- A research paper assigned in a course

- A thesis or dissertation

- A grant proposal

- An article intended for publication in a journal

All these instances require you to collect what has been written about your research topic so that you can demonstrate how your own research sheds new light on the topic.

Types of Literature Reviews

What kinds of literature reviews are written?

Narrative review: The purpose of this type of review is to describe the current state of the research on a specific topic/research and to offer a critical analysis of the literature reviewed. Studies are grouped by research/theoretical categories, and themes and trends, strengths and weakness, and gaps are identified. The review ends with a conclusion section which summarizes the findings regarding the state of the research of the specific study, the gaps identify and if applicable, explains how the author's research will address gaps identify in the review and expand the knowledge on the topic reviewed.

- Example : Predictors and Outcomes of U.S. Quality Maternity Leave: A Review and Conceptual Framework: 10.1177/08948453211037398

Systematic review : "The authors of a systematic review use a specific procedure to search the research literature, select the studies to include in their review, and critically evaluate the studies they find." (p. 139). Nelson, L. K. (2013). Research in Communication Sciences and Disorders . Plural Publishing.

- Example : The effect of leave policies on increasing fertility: a systematic review: 10.1057/s41599-022-01270-w

Meta-analysis : "Meta-analysis is a method of reviewing research findings in a quantitative fashion by transforming the data from individual studies into what is called an effect size and then pooling and analyzing this information. The basic goal in meta-analysis is to explain why different outcomes have occurred in different studies." (p. 197). Roberts, M. C., & Ilardi, S. S. (2003). Handbook of Research Methods in Clinical Psychology . Blackwell Publishing.

- Example : Employment Instability and Fertility in Europe: A Meta-Analysis: 10.1215/00703370-9164737

Meta-synthesis : "Qualitative meta-synthesis is a type of qualitative study that uses as data the findings from other qualitative studies linked by the same or related topic." (p.312). Zimmer, L. (2006). Qualitative meta-synthesis: A question of dialoguing with texts . Journal of Advanced Nursing , 53 (3), 311-318.

- Example : Women’s perspectives on career successes and barriers: A qualitative meta-synthesis: 10.1177/05390184221113735

Literature Reviews in the Health Sciences

- UConn Health subject guide on systematic reviews Explanation of the different review types used in health sciences literature as well as tools to help you find the right review type

- << Previous: Getting Started

- Next: How to Pick a Topic >>

- Last Updated: Sep 21, 2022 2:16 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.uconn.edu/literaturereview

Libraries | Research Guides

Literature reviews, what is a literature review, learning more about how to do a literature review.

- Planning the Review

- The Research Question

- Choosing Where to Search

- Organizing the Review

- Writing the Review

A literature review is a review and synthesis of existing research on a topic or research question. A literature review is meant to analyze the scholarly literature, make connections across writings and identify strengths, weaknesses, trends, and missing conversations. A literature review should address different aspects of a topic as it relates to your research question. A literature review goes beyond a description or summary of the literature you have read.

- Sage Research Methods Core Collection This link opens in a new window SAGE Research Methods supports research at all levels by providing material to guide users through every step of the research process. SAGE Research Methods is the ultimate methods library with more than 1000 books, reference works, journal articles, and instructional videos by world-leading academics from across the social sciences, including the largest collection of qualitative methods books available online from any scholarly publisher. – Publisher

- Next: Planning the Review >>

- Last Updated: May 2, 2024 10:39 AM

- URL: https://libguides.northwestern.edu/literaturereviews

- University of Texas Libraries

Literature Reviews

- What is a literature review?

- Steps in the Literature Review Process

- Define your research question

- Determine inclusion and exclusion criteria

- Choose databases and search

- Review Results

- Synthesize Results

- Analyze Results

- Librarian Support

- Artificial Intelligence (AI) Tools

What is a Literature Review?

A literature or narrative review is a comprehensive review and analysis of the published literature on a specific topic or research question. The literature that is reviewed contains: books, articles, academic articles, conference proceedings, association papers, and dissertations. It contains the most pertinent studies and points to important past and current research and practices. It provides background and context, and shows how your research will contribute to the field.

A literature review should:

- Provide a comprehensive and updated review of the literature;

- Explain why this review has taken place;

- Articulate a position or hypothesis;

- Acknowledge and account for conflicting and corroborating points of view

From S age Research Methods

Purpose of a Literature Review

A literature review can be written as an introduction to a study to:

- Demonstrate how a study fills a gap in research

- Compare a study with other research that's been done

Or it can be a separate work (a research article on its own) which:

- Organizes or describes a topic

- Describes variables within a particular issue/problem

Limitations of a Literature Review

Some of the limitations of a literature review are:

- It's a snapshot in time. Unlike other reviews, this one has beginning, a middle and an end. There may be future developments that could make your work less relevant.

- It may be too focused. Some niche studies may miss the bigger picture.

- It can be difficult to be comprehensive. There is no way to make sure all the literature on a topic was considered.

- It is easy to be biased if you stick to top tier journals. There may be other places where people are publishing exemplary research. Look to open access publications and conferences to reflect a more inclusive collection. Also, make sure to include opposing views (and not just supporting evidence).

Source: Grant, Maria J., and Andrew Booth. “A Typology of Reviews: An Analysis of 14 Review Types and Associated Methodologies.” Health Information & Libraries Journal, vol. 26, no. 2, June 2009, pp. 91–108. Wiley Online Library, doi:10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x.

Meryl Brodsky : Communication and Information Studies

Hannah Chapman Tripp : Biology, Neuroscience

Carolyn Cunningham : Human Development & Family Sciences, Psychology, Sociology

Larayne Dallas : Engineering

Janelle Hedstrom : Special Education, Curriculum & Instruction, Ed Leadership & Policy

Susan Macicak : Linguistics

Imelda Vetter : Dell Medical School

For help in other subject areas, please see the guide to library specialists by subject .

Periodically, UT Libraries runs a workshop covering the basics and library support for literature reviews. While we try to offer these once per academic year, we find providing the recording to be helpful to community members who have missed the session. Following is the most recent recording of the workshop, Conducting a Literature Review. To view the recording, a UT login is required.

- October 26, 2022 recording

- Last Updated: Jun 18, 2024 1:00 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.utexas.edu/literaturereviews

- Link to facebook

- Link to linkedin

- Link to twitter

- Link to youtube

- Writing Tips

What is the Purpose of a Literature Review?

4-minute read

- 23rd October 2023

If you’re writing a research paper or dissertation , then you’ll most likely need to include a comprehensive literature review . In this post, we’ll review the purpose of literature reviews, why they are so significant, and the specific elements to include in one. Literature reviews can:

1. Provide a foundation for current research.

2. Define key concepts and theories.

3. Demonstrate critical evaluation.

4. Show how research and methodologies have evolved.

5. Identify gaps in existing research.

6. Support your argument.

Keep reading to enter the exciting world of literature reviews!

What is a Literature Review?

A literature review is a critical summary and evaluation of the existing research (e.g., academic journal articles and books) on a specific topic. It is typically included as a separate section or chapter of a research paper or dissertation, serving as a contextual framework for a study. Literature reviews can vary in length depending on the subject and nature of the study, with most being about equal length to other sections or chapters included in the paper. Essentially, the literature review highlights previous studies in the context of your research and summarizes your insights in a structured, organized format. Next, let’s look at the overall purpose of a literature review.

Find this useful?

Subscribe to our newsletter and get writing tips from our editors straight to your inbox.

Literature reviews are considered an integral part of research across most academic subjects and fields. The primary purpose of a literature review in your study is to:

Provide a Foundation for Current Research

Since the literature review provides a comprehensive evaluation of the existing research, it serves as a solid foundation for your current study. It’s a way to contextualize your work and show how your research fits into the broader landscape of your specific area of study.

Define Key Concepts and Theories

The literature review highlights the central theories and concepts that have arisen from previous research on your chosen topic. It gives your readers a more thorough understanding of the background of your study and why your research is particularly significant .

Demonstrate Critical Evaluation

A comprehensive literature review shows your ability to critically analyze and evaluate a broad range of source material. And since you’re considering and acknowledging the contribution of key scholars alongside your own, it establishes your own credibility and knowledge.

Show How Research and Methodologies Have Evolved

Another purpose of literature reviews is to provide a historical perspective and demonstrate how research and methodologies have changed over time, especially as data collection methods and technology have advanced. And studying past methodologies allows you, as the researcher, to understand what did and did not work and apply that knowledge to your own research.

Identify Gaps in Existing Research

Besides discussing current research and methodologies, the literature review should also address areas that are lacking in the existing literature. This helps further demonstrate the relevance of your own research by explaining why your study is necessary to fill the gaps.

Support Your Argument

A good literature review should provide evidence that supports your research questions and hypothesis. For example, your study may show that your research supports existing theories or builds on them in some way. Referencing previous related studies shows your work is grounded in established research and will ultimately be a contribution to the field.

Literature Review Editing Services

Ensure your literature review is polished and ready for submission by having it professionally proofread and edited by our expert team. Our literature review editing services will help your research stand out and make an impact. Not convinced yet? Send in your free sample today and see for yourself!

Share this article:

Post A New Comment

Got content that needs a quick turnaround? Let us polish your work. Explore our editorial business services.

9-minute read

How to Use Infographics to Boost Your Presentation

Is your content getting noticed? Capturing and maintaining an audience’s attention is a challenge when...

8-minute read

Why Interactive PDFs Are Better for Engagement

Are you looking to enhance engagement and captivate your audience through your professional documents? Interactive...

7-minute read

Seven Key Strategies for Voice Search Optimization

Voice search optimization is rapidly shaping the digital landscape, requiring content professionals to adapt their...

Five Creative Ways to Showcase Your Digital Portfolio

Are you a creative freelancer looking to make a lasting impression on potential clients or...

How to Ace Slack Messaging for Contractors and Freelancers

Effective professional communication is an important skill for contractors and freelancers navigating remote work environments....

3-minute read

How to Insert a Text Box in a Google Doc

Google Docs is a powerful collaborative tool, and mastering its features can significantly enhance your...

Make sure your writing is the best it can be with our expert English proofreading and editing.

Harvey Cushing/John Hay Whitney Medical Library

- Collections

- Research Help

YSN Doctoral Programs: Steps in Conducting a Literature Review

- Biomedical Databases

- Global (Public Health) Databases

- Soc. Sci., History, and Law Databases

- Grey Literature

- Trials Registers

- Data and Statistics

- Public Policy

- Google Tips

- Recommended Books

- Steps in Conducting a Literature Review

What is a literature review?

A literature review is an integrated analysis -- not just a summary-- of scholarly writings and other relevant evidence related directly to your research question. That is, it represents a synthesis of the evidence that provides background information on your topic and shows a association between the evidence and your research question.

A literature review may be a stand alone work or the introduction to a larger research paper, depending on the assignment. Rely heavily on the guidelines your instructor has given you.

Why is it important?

A literature review is important because it:

- Explains the background of research on a topic.

- Demonstrates why a topic is significant to a subject area.

- Discovers relationships between research studies/ideas.

- Identifies major themes, concepts, and researchers on a topic.

- Identifies critical gaps and points of disagreement.

- Discusses further research questions that logically come out of the previous studies.

APA7 Style resources

APA Style Blog - for those harder to find answers

1. Choose a topic. Define your research question.

Your literature review should be guided by your central research question. The literature represents background and research developments related to a specific research question, interpreted and analyzed by you in a synthesized way.

- Make sure your research question is not too broad or too narrow. Is it manageable?

- Begin writing down terms that are related to your question. These will be useful for searches later.

- If you have the opportunity, discuss your topic with your professor and your class mates.

2. Decide on the scope of your review

How many studies do you need to look at? How comprehensive should it be? How many years should it cover?

- This may depend on your assignment. How many sources does the assignment require?

3. Select the databases you will use to conduct your searches.

Make a list of the databases you will search.

Where to find databases:

- use the tabs on this guide

- Find other databases in the Nursing Information Resources web page

- More on the Medical Library web page

- ... and more on the Yale University Library web page

4. Conduct your searches to find the evidence. Keep track of your searches.

- Use the key words in your question, as well as synonyms for those words, as terms in your search. Use the database tutorials for help.

- Save the searches in the databases. This saves time when you want to redo, or modify, the searches. It is also helpful to use as a guide is the searches are not finding any useful results.

- Review the abstracts of research studies carefully. This will save you time.

- Use the bibliographies and references of research studies you find to locate others.

- Check with your professor, or a subject expert in the field, if you are missing any key works in the field.

- Ask your librarian for help at any time.

- Use a citation manager, such as EndNote as the repository for your citations. See the EndNote tutorials for help.

Review the literature

Some questions to help you analyze the research:

- What was the research question of the study you are reviewing? What were the authors trying to discover?

- Was the research funded by a source that could influence the findings?

- What were the research methodologies? Analyze its literature review, the samples and variables used, the results, and the conclusions.

- Does the research seem to be complete? Could it have been conducted more soundly? What further questions does it raise?

- If there are conflicting studies, why do you think that is?

- How are the authors viewed in the field? Has this study been cited? If so, how has it been analyzed?

Tips:

- Review the abstracts carefully.

- Keep careful notes so that you may track your thought processes during the research process.

- Create a matrix of the studies for easy analysis, and synthesis, across all of the studies.

- << Previous: Recommended Books

- Last Updated: Jun 20, 2024 9:08 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.yale.edu/YSNDoctoral

Research Process :: Step by Step

- Introduction

- Select Topic

- Identify Keywords

- Background Information

- Develop Research Questions

- Refine Topic

- Search Strategy

- Popular Databases

- Evaluate Sources

- Types of Periodicals

- Reading Scholarly Articles

- Primary & Secondary Sources

- Organize / Take Notes

- Writing & Grammar Resources

- Annotated Bibliography

- Literature Review

- Citation Styles

- Paraphrasing

- Privacy / Confidentiality

- Research Process

- Selecting Your Topic

- Identifying Keywords

- Gathering Background Info

- Evaluating Sources

Organize the literature review into sections that present themes or identify trends, including relevant theory. You are not trying to list all the material published, but to synthesize and evaluate it according to the guiding concept of your thesis or research question.

What is a literature review?

A literature review is an account of what has been published on a topic by accredited scholars and researchers. Occasionally you will be asked to write one as a separate assignment, but more often it is part of the introduction to an essay, research report, or thesis. In writing the literature review, your purpose is to convey to your reader what knowledge and ideas have been established on a topic, and what their strengths and weaknesses are. As a piece of writing, the literature review must be defined by a guiding concept (e.g., your research objective, the problem or issue you are discussing, or your argumentative thesis). It is not just a descriptive list of the material available, or a set of summaries

A literature review must do these things:

- be organized around and related directly to the thesis or research question you are developing

- synthesize results into a summary of what is and is not known

- identify areas of controversy in the literature

- formulate questions that need further research

Ask yourself questions like these:

- What is the specific thesis, problem, or research question that my literature review helps to define?

- What type of literature review am I conducting? Am I looking at issues of theory? methodology? policy? quantitative research (e.g. on the effectiveness of a new procedure)? qualitative research (e.g., studies of loneliness among migrant workers)?

- What is the scope of my literature review? What types of publications am I using (e.g., journals, books, government documents, popular media)? What discipline am I working in (e.g., nursing psychology, sociology, medicine)?

- How good was my information seeking? Has my search been wide enough to ensure I've found all the relevant material? Has it been narrow enough to exclude irrelevant material? Is the number of sources I've used appropriate for the length of my paper?

- Have I critically analyzed the literature I use? Do I follow through a set of concepts and questions, comparing items to each other in the ways they deal with them? Instead of just listing and summarizing items, do I assess them, discussing strengths and weaknesses?

- Have I cited and discussed studies contrary to my perspective?

- Will the reader find my literature review relevant, appropriate, and useful?

Ask yourself questions like these about each book or article you include:

- Has the author formulated a problem/issue?

- Is it clearly defined? Is its significance (scope, severity, relevance) clearly established?

- Could the problem have been approached more effectively from another perspective?

- What is the author's research orientation (e.g., interpretive, critical science, combination)?

- What is the author's theoretical framework (e.g., psychological, developmental, feminist)?

- What is the relationship between the theoretical and research perspectives?

- Has the author evaluated the literature relevant to the problem/issue? Does the author include literature taking positions she or he does not agree with?

- In a research study, how good are the basic components of the study design (e.g., population, intervention, outcome)? How accurate and valid are the measurements? Is the analysis of the data accurate and relevant to the research question? Are the conclusions validly based upon the data and analysis?

- In material written for a popular readership, does the author use appeals to emotion, one-sided examples, or rhetorically-charged language and tone? Is there an objective basis to the reasoning, or is the author merely "proving" what he or she already believes?

- How does the author structure the argument? Can you "deconstruct" the flow of the argument to see whether or where it breaks down logically (e.g., in establishing cause-effect relationships)?

- In what ways does this book or article contribute to our understanding of the problem under study, and in what ways is it useful for practice? What are the strengths and limitations?

- How does this book or article relate to the specific thesis or question I am developing?

Text written by Dena Taylor, Health Sciences Writing Centre, University of Toronto

http://www.writing.utoronto.ca/advice/specific-types-of-writing/literature-review

- << Previous: Annotated Bibliography

- Next: Step 5: Cite Sources >>

- Last Updated: Jun 13, 2024 4:27 PM

- URL: https://libguides.uta.edu/researchprocess

University of Texas Arlington Libraries 702 Planetarium Place · Arlington, TX 76019 · 817-272-3000

- Internet Privacy

- Accessibility

- Problems with a guide? Contact Us.

Frequently asked questions

What is the purpose of a literature review.

There are several reasons to conduct a literature review at the beginning of a research project:

- To familiarize yourself with the current state of knowledge on your topic

- To ensure that you’re not just repeating what others have already done

- To identify gaps in knowledge and unresolved problems that your research can address

- To develop your theoretical framework and methodology

- To provide an overview of the key findings and debates on the topic

Writing the literature review shows your reader how your work relates to existing research and what new insights it will contribute.

Frequently asked questions: Academic writing

A rhetorical tautology is the repetition of an idea of concept using different words.

Rhetorical tautologies occur when additional words are used to convey a meaning that has already been expressed or implied. For example, the phrase “armed gunman” is a tautology because a “gunman” is by definition “armed.”

A logical tautology is a statement that is always true because it includes all logical possibilities.

Logical tautologies often take the form of “either/or” statements (e.g., “It will rain, or it will not rain”) or employ circular reasoning (e.g., “she is untrustworthy because she can’t be trusted”).

You may have seen both “appendices” or “appendixes” as pluralizations of “ appendix .” Either spelling can be used, but “appendices” is more common (including in APA Style ). Consistency is key here: make sure you use the same spelling throughout your paper.

The purpose of a lab report is to demonstrate your understanding of the scientific method with a hands-on lab experiment. Course instructors will often provide you with an experimental design and procedure. Your task is to write up how you actually performed the experiment and evaluate the outcome.

In contrast, a research paper requires you to independently develop an original argument. It involves more in-depth research and interpretation of sources and data.

A lab report is usually shorter than a research paper.

The sections of a lab report can vary between scientific fields and course requirements, but it usually contains the following:

- Title: expresses the topic of your study

- Abstract: summarizes your research aims, methods, results, and conclusions

- Introduction: establishes the context needed to understand the topic

- Method: describes the materials and procedures used in the experiment

- Results: reports all descriptive and inferential statistical analyses

- Discussion: interprets and evaluates results and identifies limitations

- Conclusion: sums up the main findings of your experiment

- References: list of all sources cited using a specific style (e.g. APA)

- Appendices: contains lengthy materials, procedures, tables or figures

A lab report conveys the aim, methods, results, and conclusions of a scientific experiment . Lab reports are commonly assigned in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) fields.

The abstract is the very last thing you write. You should only write it after your research is complete, so that you can accurately summarize the entirety of your thesis , dissertation or research paper .

If you’ve gone over the word limit set for your assignment, shorten your sentences and cut repetition and redundancy during the editing process. If you use a lot of long quotes , consider shortening them to just the essentials.

If you need to remove a lot of words, you may have to cut certain passages. Remember that everything in the text should be there to support your argument; look for any information that’s not essential to your point and remove it.

To make this process easier and faster, you can use a paraphrasing tool . With this tool, you can rewrite your text to make it simpler and shorter. If that’s not enough, you can copy-paste your paraphrased text into the summarizer . This tool will distill your text to its core message.

Revising, proofreading, and editing are different stages of the writing process .

- Revising is making structural and logical changes to your text—reformulating arguments and reordering information.

- Editing refers to making more local changes to things like sentence structure and phrasing to make sure your meaning is conveyed clearly and concisely.

- Proofreading involves looking at the text closely, line by line, to spot any typos and issues with consistency and correct them.

The literature review usually comes near the beginning of your thesis or dissertation . After the introduction , it grounds your research in a scholarly field and leads directly to your theoretical framework or methodology .

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a thesis, dissertation , or research paper , in order to situate your work in relation to existing knowledge.

Avoid citing sources in your abstract . There are two reasons for this:

- The abstract should focus on your original research, not on the work of others.

- The abstract should be self-contained and fully understandable without reference to other sources.

There are some circumstances where you might need to mention other sources in an abstract: for example, if your research responds directly to another study or focuses on the work of a single theorist. In general, though, don’t include citations unless absolutely necessary.

An abstract is a concise summary of an academic text (such as a journal article or dissertation ). It serves two main purposes:

- To help potential readers determine the relevance of your paper for their own research.

- To communicate your key findings to those who don’t have time to read the whole paper.

Abstracts are often indexed along with keywords on academic databases, so they make your work more easily findable. Since the abstract is the first thing any reader sees, it’s important that it clearly and accurately summarizes the contents of your paper.

In a scientific paper, the methodology always comes after the introduction and before the results , discussion and conclusion . The same basic structure also applies to a thesis, dissertation , or research proposal .

Depending on the length and type of document, you might also include a literature review or theoretical framework before the methodology.

Whether you’re publishing a blog, submitting a research paper , or even just writing an important email, there are a few techniques you can use to make sure it’s error-free:

- Take a break : Set your work aside for at least a few hours so that you can look at it with fresh eyes.

- Proofread a printout : Staring at a screen for too long can cause fatigue – sit down with a pen and paper to check the final version.

- Use digital shortcuts : Take note of any recurring mistakes (for example, misspelling a particular word, switching between US and UK English , or inconsistently capitalizing a term), and use Find and Replace to fix it throughout the document.

If you want to be confident that an important text is error-free, it might be worth choosing a professional proofreading service instead.

Editing and proofreading are different steps in the process of revising a text.

Editing comes first, and can involve major changes to content, structure and language. The first stages of editing are often done by authors themselves, while a professional editor makes the final improvements to grammar and style (for example, by improving sentence structure and word choice ).

Proofreading is the final stage of checking a text before it is published or shared. It focuses on correcting minor errors and inconsistencies (for example, in punctuation and capitalization ). Proofreaders often also check for formatting issues, especially in print publishing.

The cost of proofreading depends on the type and length of text, the turnaround time, and the level of services required. Most proofreading companies charge per word or page, while freelancers sometimes charge an hourly rate.

For proofreading alone, which involves only basic corrections of typos and formatting mistakes, you might pay as little as $0.01 per word, but in many cases, your text will also require some level of editing , which costs slightly more.

It’s often possible to purchase combined proofreading and editing services and calculate the price in advance based on your requirements.

There are many different routes to becoming a professional proofreader or editor. The necessary qualifications depend on the field – to be an academic or scientific proofreader, for example, you will need at least a university degree in a relevant subject.

For most proofreading jobs, experience and demonstrated skills are more important than specific qualifications. Often your skills will be tested as part of the application process.

To learn practical proofreading skills, you can choose to take a course with a professional organization such as the Society for Editors and Proofreaders . Alternatively, you can apply to companies that offer specialized on-the-job training programmes, such as the Scribbr Academy .

Ask our team

Want to contact us directly? No problem. We are always here for you.

- Email [email protected]

- Start live chat

- Call +1 (510) 822-8066

- WhatsApp +31 20 261 6040

Our team helps students graduate by offering:

- A world-class citation generator

- Plagiarism Checker software powered by Turnitin

- Innovative Citation Checker software

- Professional proofreading services

- Over 300 helpful articles about academic writing, citing sources, plagiarism, and more

Scribbr specializes in editing study-related documents . We proofread:

- PhD dissertations

- Research proposals

- Personal statements

- Admission essays

- Motivation letters

- Reflection papers

- Journal articles

- Capstone projects

Scribbr’s Plagiarism Checker is powered by elements of Turnitin’s Similarity Checker , namely the plagiarism detection software and the Internet Archive and Premium Scholarly Publications content databases .

The add-on AI detector is powered by Scribbr’s proprietary software.

The Scribbr Citation Generator is developed using the open-source Citation Style Language (CSL) project and Frank Bennett’s citeproc-js . It’s the same technology used by dozens of other popular citation tools, including Mendeley and Zotero.

You can find all the citation styles and locales used in the Scribbr Citation Generator in our publicly accessible repository on Github .

Research Problem and Literature Review

Cite this chapter.

- Eunsook T. Koh 2 &

- Willis L. Owen 2

648 Accesses

Getting started is the hardest part of almost any new venture, and research is no exception. You cannot do any significant research until you have identified the area you want to investigate, learned what has been published in that area, and figured out how you are going to conduct the investigation. In this chapter, we will discuss ways by which a person can identify researchable problems, search for literature, and write the literature review.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Unable to display preview. Download preview PDF.

Ard, N.F. Long term effects of oral fructose on blood lipid components in diabetic and non-diabetic subjects. Thesis, Norman, Oklahoma; University of Oklahoma, 1984.

Google Scholar

Davidson, M. Computing and Information Technology. London: Straightforward Publishing, Ltd, 1994.

Day, R.D. How to Write and Publish a Scientific Paper. (2nd ed) Philadelphia, PA: ISI press, 1983.

Glowniak J.V., Bushway M.K. Computer networks as a medical resource: Accessing and using the internet. JAMA, 1994; 271: 1934–1939.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Fox, D.J. The Research Process in Education. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1969.

High Wire Press: Internet imprint of the Stanford University Libraries. http://www.highwire.org/

Hones, R.L., Chissom, B.S. A Student Guide for Educational Research. Statesboro, GA: Vog Press, 1975.

Koh E.T., Ard N.F., Mendoza F. Effect of fructose feeding on blood parameters and blood pressure in impaired glucose-tolerant subjects. J Am Dietet A, 1988; 88:932

CAS Google Scholar

Kroll, E. The Whole Internet: User’s Guide and Catalog. Sebastopol, O’Reilly and Associates, 1994.

Lee, R. How to Find Information — Life Science: a Guide to Searching in Published Source. London: British Library, 1992.

Loehle C. A guide to increased creativity in research — inspiration or perspiration? BioScience, 1990; 40:123–129

Article Google Scholar

Lowe H.J., Barnett G.O. Understanding and using the medical subject headings (MeSH) vocabulary to perform literature searches. JAMA, 1994; 271: 1103–1108

Morse, J. Qualitative Nursing Research. Rockville, MD: Aspen, 1989.

McKenzie, B. Medicine and the Internet: Introducing Online Resources (4 th ed.) London: Bowker Saur, 1992.

Snyder, C.W. Jr, Abernethy, B. eds. The Creative Side of Experimentation. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, 1992.

Thomas, J.R., Nelson, J.K. Research Methods in Physical Activity (3rd ed.) Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, 1996.

Van Dalen, D.B. Understanding Educational Research: An Introduction (4th ed.) New York: McGraw-Hill, 1979.

Woodsmall R.M., Benson D.A. Information resources at the National Center for Biotechnology Information. Bulletin Medical Library Association, 1993; 81:282–284

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, USA

Eunsook T. Koh & Willis L. Owen

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2000 Springer Science+Business Media New York

About this chapter

Koh, E.T., Owen, W.L. (2000). Research Problem and Literature Review. In: Introduction to Nutrition and Health Research. Springer, Boston, MA. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4615-1401-5_2

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4615-1401-5_2

Publisher Name : Springer, Boston, MA

Print ISBN : 978-1-4613-5535-9

Online ISBN : 978-1-4615-1401-5

eBook Packages : Springer Book Archive

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Topic Guide - Developing Your Research Study

- Purpose of Guide

- Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- APA 7th Edition

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

Importance of a Good Literature Review

Types of Literature Reviews

Structure and Writing Style

Writing tip, another writing tip, yet another writing tip.

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- What Is Scholarly vs. Popular?

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- 10. Proofreading Your Paper

- Writing Concisely

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Annotated Bibliography

- Types of Structured Group Activities

- Group Project Survival Skills

- Multiple Book Review Essay

- Reviewing Collected Works

- Writing a Case Study

- Writing a Research Proposal

- Bibliography

A literature review surveys books, scholarly articles, and any other sources relevant to a particular issue, area of research, or theory; thereby, provides a description, summary, and critical evaluation of the works in relation to the research problem being investigated. Literature reviews are designed to provide an overview of sources you have explored while researching a particular topic and to demonstrate to your readers how your research fits within a larger field of study.

Some more thoroughly detailed sources to follow for developing a literature review would be Conducting Research Literature Reviews and/or Doing a Literature Review by Chris Hart — both of which are located in our Squires Library collection.

Fink, Arlene. Conducting Research Literature Reviews : From the Internet to Paper . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 1998.

Hart, Chris. Doing a literature review : releasing the social science research imagination London: SAGE, 2005

A literature review may consist of simply a summary of key sources, but in many disciplines, a literature review has an organizational pattern and combines both a summary and a synthesis, often within specific conceptual categories . A summary is a recap of the important information of the source, whereas a synthesis is a re-organization, or a reshuffling, of that information in a way that informs how you are planning to investigate a research problem. The analytical features of a literature review might:

- Give a new interpretation of old material or combine new with old interpretations,

- Trace the intellectual progression of the field, including major debates,

- Depending on the situation, evaluate the sources and advise the reader on the most pertinent or relevant research, or

- Usually in the conclusion of a literature review, identify where gaps exist in how a problem has been researched to date.

The purpose of a literature review is to:

- Place each work in the context of its contribution to understanding the research problem being studied.

- Describe the relationship of each work to the others under consideration.

- Identify new ways to interpret prior research.

- Reveal any gaps that exist in the literature.

- Reveal conflicts amongst seemingly contradictory previous studies.

- Identify areas of prior scholarship to prevent duplication of effort.

- Point the way in fulfilling a need for additional research. This is often directly related to the gap(s) revealed .

- Locate your own research idea(s) / intent within the context of existing literature [very important].

Fink, Arlene. Conducting Research Literature Reviews : From the Internet to Paper. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2005; Hart, Chris. Doing a Literature Review: Releasing the Social Science Research Imagination . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2006 The Literature Review: Six Steps to Success . 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, California : Corwin, 2016.

It is important to think of knowledge in a given field as consisting of three layers. First, there are the primary studies that researchers conduct and publish. Second are the reviews of those studies that summarize and offer new interpretations built from and often extending beyond the primary studies. Third, there are the perceptions, conclusions, opinion, and interpretations that are shared informally that become part of the lore of field.

In composing a literature review, it is important to note that it is often this third layer of knowledge that is cited as "true" even though it often has only a loose relationship to the primary studies and secondary literature reviews. Given this, while literature reviews are designed to provide an overview and synthesis of pertinent sources you have explored, there are a number of approaches you could adopt depending upon the type of analysis underpinning your study.

Argumentative Review This form examines literature selectively in order to support or refute an argument, deeply imbedded assumption, or philosophical problem already established in the literature. The purpose is to develop a body of literature that establishes a contrarian viewpoint. Given the value-laden nature of some social science research [e.g., educational reform; immigration control], argumentative approaches to analyzing the literature can be a legitimate and important form of discourse. However, note that they can also introduce problems of bias when they are used to make summary claims of the sort found in systematic reviews [see below].

Integrative Review Considered a form of research that reviews, critiques, and synthesizes representative literature on a topic in an integrated way such that new frameworks and perspectives on the topic are generated. The body of literature includes all studies that address related or identical hypotheses or research problems. A well-done integrative review meets the same standards as primary research in regard to clarity, rigor, and replication. This is the most common form of review in the social sciences.

Historical Review Few things rest in isolation from historical precedent. Historical literature reviews focus on examining research throughout a period of time, often starting with the first time an issue, concept, theory, phenomena emerged in the literature, then tracing its evolution within the scholarship of a discipline. The purpose is to place research in a historical context to show familiarity with state-of-the-art developments and to identify the likely directions for future research.

Methodological Review A review does not always focus on what someone said [findings], but how they came about saying what they say [method of analysis]. Reviewing methods of analysis provides a framework of understanding at different levels [i.e. those of theory, substantive fields, research approaches, and data collection and analysis techniques], how researchers draw upon a wide variety of knowledge ranging from the conceptual level to practical documents for use in fieldwork in the areas of ontological and epistemological consideration, quantitative and qualitative integration, sampling, interviewing, data collection, and data analysis. This approach helps highlight ethical issues which you should be aware of and consider as you go through your own study.

Systematic Review This form consists of an overview of existing evidence pertinent to a clearly formulated research question, which uses pre-specified and standardized methods to identify and critically appraise relevant research, and to collect, report, and analyze data from the studies that are included in the review. The goal is to deliberately document, critically evaluate, and summarize scientifically all of the research about a clearly defined research problem . Typically it focuses on a very specific empirical question, often posed in a cause-and-effect form, such as "To what extent does A contribute to B?" This type of literature review is primarily applied to examining prior research studies in clinical medicine and allied health fields, but it is increasingly being used in the social sciences.

Theoretical Review The purpose of this form is to examine the corpus of theory that has accumulated in regard to an issue, concept, theory, phenomena. The theoretical literature review helps to establish what theories already exist, the relationships between them, to what degree the existing theories have been investigated, and to develop new hypotheses to be tested. Often this form is used to help establish a lack of appropriate theories or reveal that current theories are inadequate for explaining new or emerging research problems. The unit of analysis can focus on a theoretical concept or a whole theory or framework.

Baumeister, Roy F. and Mark R. Leary. "Writing Narrative Literature Reviews." Review of General Psychology 1 (September 1997): 311-320; Mark R. Fink, Arlene. Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From the Internet to Paper . 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2005; Hart, Chris. Doing a Literature Review: Releasing the Social Science Research Imagination . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1998; Kennedy, Mary M. "Defining a Literature." Educational Researcher 36 (April 2007): 139-147; Petticrew, Mark and Helen Roberts. Systematic Reviews in the Social Sciences: A Practical Guide . Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers, 2006; Torracro, Richard. "Writing Integrative Literature Reviews: Guidelines and Examples." Human Resource Development Review 4 (September 2005): 356-367; Rocco, Tonette S. and Maria S. Plakhotnik. "Literature Reviews, Conceptual Frameworks, and Theoretical Frameworks: Terms, Functions, and Distinctions." Human Ressource Development Review 8 (March 2008): 120-130; Sutton, Anthea. Systematic Approaches to a Successful Literature Review . Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications, 2016.

I. Thinking About Your Literature Revie w

The structure of a literature review should include the following :

- An overview of the subject, issue, or theory under consideration, along with the objectives of the literature review,

- Division of works under review into themes or categories [e.g. works that support a particular position, those against, and those offering alternative approaches entirely],

- An explanation of how each work is similar to and how it varies from the others,

- Conclusions as to which pieces are best considered in their argument, are most convincing of their opinions, and make the greatest contribution to the understanding and development of their area of research.

The critical evaluation of each work should consider :

- Provenance -- what are the author's credentials? Are the author's arguments supported by evidence [e.g. primary historical material, case studies, narratives, statistics, recent scientific findings]?

- Methodology -- were the techniques used to identify, gather, and analyze the data appropriate to addressing the research problem? Was the sample size appropriate? Were the results effectively interpreted and reported?

- Objectivity -- is the author's perspective even-handed or prejudicial? Is contrary data considered or is certain pertinent information ignored to prove the author's point?

- Persuasiveness -- which of the author's theses are most convincing or least convincing?

- Value -- are the author's arguments and conclusions convincing? Does the work ultimately contribute in any significant way to an understanding of the subject?

II. Development of the Literature Review

Four Stages 1. Problem formulation -- which topic or field is being examined and what are its component issues? 2. Literature search -- finding materials relevant to the subject being explored. 3. Data evaluation -- determining which literature makes a significant contribution to the understanding of the topic. 4. Analysis and interpretation -- discussing the findings and conclusions of pertinent literature.

This video can be of assistance as it provides direction for literature review planning, processing, and writing - Video Additionally, the speaker on the previous video, did one on Literature Review Basics: 7 Major Mistakes To Avoid — however, beware, this video is so thorough, that it is 1 hr in length. Either plan an hour or split the time up to view the content in portions.

Address the following matters prior to writing the literature review: Clarify If your assignment is not very specific about what form your literature review should take, seek clarification from your professor by asking these questions:

1. Roughly how many sources should I include?

2. What types of sources should I review (books, journal articles, websites; scholarly versus popular sources)?

3. Should I summarize, synthesize, or critique sources by discussing a common theme or issue?

5. Should I provide subheadings and other background information, such as definitions and/or a history

6. Should the literature review address the theoretical framework (theory applied to the intended study)?