Get science-backed answers as you write with Paperpal's Research feature

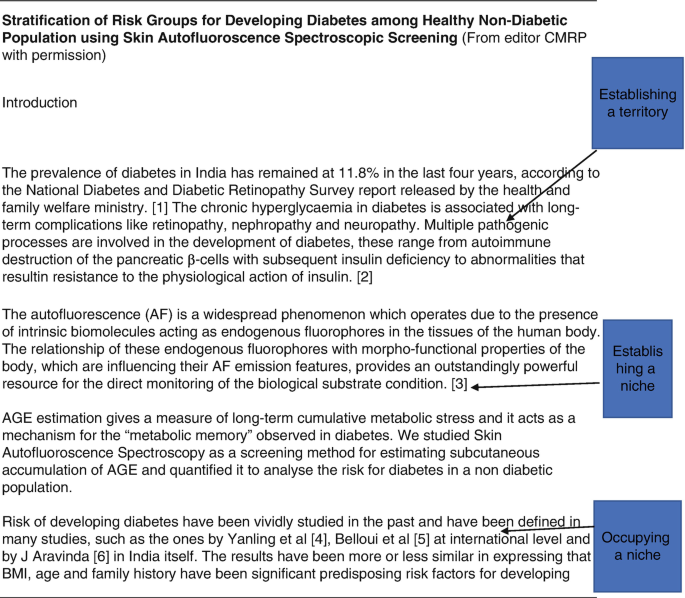

How to Write a Research Paper Introduction (with Examples)

The research paper introduction section, along with the Title and Abstract, can be considered the face of any research paper. The following article is intended to guide you in organizing and writing the research paper introduction for a quality academic article or dissertation.

The research paper introduction aims to present the topic to the reader. A study will only be accepted for publishing if you can ascertain that the available literature cannot answer your research question. So it is important to ensure that you have read important studies on that particular topic, especially those within the last five to ten years, and that they are properly referenced in this section. 1 What should be included in the research paper introduction is decided by what you want to tell readers about the reason behind the research and how you plan to fill the knowledge gap. The best research paper introduction provides a systemic review of existing work and demonstrates additional work that needs to be done. It needs to be brief, captivating, and well-referenced; a well-drafted research paper introduction will help the researcher win half the battle.

The introduction for a research paper is where you set up your topic and approach for the reader. It has several key goals:

- Present your research topic

- Capture reader interest

- Summarize existing research

- Position your own approach

- Define your specific research problem and problem statement

- Highlight the novelty and contributions of the study

- Give an overview of the paper’s structure

The research paper introduction can vary in size and structure depending on whether your paper presents the results of original empirical research or is a review paper. Some research paper introduction examples are only half a page while others are a few pages long. In many cases, the introduction will be shorter than all of the other sections of your paper; its length depends on the size of your paper as a whole.

- Break through writer’s block. Write your research paper introduction with Paperpal Copilot

Table of Contents

What is the introduction for a research paper, why is the introduction important in a research paper, craft a compelling introduction section with paperpal. try now, 1. introduce the research topic:, 2. determine a research niche:, 3. place your research within the research niche:, craft accurate research paper introductions with paperpal. start writing now, frequently asked questions on research paper introduction, key points to remember.

The introduction in a research paper is placed at the beginning to guide the reader from a broad subject area to the specific topic that your research addresses. They present the following information to the reader

- Scope: The topic covered in the research paper

- Context: Background of your topic

- Importance: Why your research matters in that particular area of research and the industry problem that can be targeted

The research paper introduction conveys a lot of information and can be considered an essential roadmap for the rest of your paper. A good introduction for a research paper is important for the following reasons:

- It stimulates your reader’s interest: A good introduction section can make your readers want to read your paper by capturing their interest. It informs the reader what they are going to learn and helps determine if the topic is of interest to them.

- It helps the reader understand the research background: Without a clear introduction, your readers may feel confused and even struggle when reading your paper. A good research paper introduction will prepare them for the in-depth research to come. It provides you the opportunity to engage with the readers and demonstrate your knowledge and authority on the specific topic.

- It explains why your research paper is worth reading: Your introduction can convey a lot of information to your readers. It introduces the topic, why the topic is important, and how you plan to proceed with your research.

- It helps guide the reader through the rest of the paper: The research paper introduction gives the reader a sense of the nature of the information that will support your arguments and the general organization of the paragraphs that will follow. It offers an overview of what to expect when reading the main body of your paper.

What are the parts of introduction in the research?

A good research paper introduction section should comprise three main elements: 2

- What is known: This sets the stage for your research. It informs the readers of what is known on the subject.

- What is lacking: This is aimed at justifying the reason for carrying out your research. This could involve investigating a new concept or method or building upon previous research.

- What you aim to do: This part briefly states the objectives of your research and its major contributions. Your detailed hypothesis will also form a part of this section.

How to write a research paper introduction?

The first step in writing the research paper introduction is to inform the reader what your topic is and why it’s interesting or important. This is generally accomplished with a strong opening statement. The second step involves establishing the kinds of research that have been done and ending with limitations or gaps in the research that you intend to address. Finally, the research paper introduction clarifies how your own research fits in and what problem it addresses. If your research involved testing hypotheses, these should be stated along with your research question. The hypothesis should be presented in the past tense since it will have been tested by the time you are writing the research paper introduction.

The following key points, with examples, can guide you when writing the research paper introduction section:

- Highlight the importance of the research field or topic

- Describe the background of the topic

- Present an overview of current research on the topic

Example: The inclusion of experiential and competency-based learning has benefitted electronics engineering education. Industry partnerships provide an excellent alternative for students wanting to engage in solving real-world challenges. Industry-academia participation has grown in recent years due to the need for skilled engineers with practical training and specialized expertise. However, from the educational perspective, many activities are needed to incorporate sustainable development goals into the university curricula and consolidate learning innovation in universities.

- Reveal a gap in existing research or oppose an existing assumption

- Formulate the research question

Example: There have been plausible efforts to integrate educational activities in higher education electronics engineering programs. However, very few studies have considered using educational research methods for performance evaluation of competency-based higher engineering education, with a focus on technical and or transversal skills. To remedy the current need for evaluating competencies in STEM fields and providing sustainable development goals in engineering education, in this study, a comparison was drawn between study groups without and with industry partners.

- State the purpose of your study

- Highlight the key characteristics of your study

- Describe important results

- Highlight the novelty of the study.

- Offer a brief overview of the structure of the paper.

Example: The study evaluates the main competency needed in the applied electronics course, which is a fundamental core subject for many electronics engineering undergraduate programs. We compared two groups, without and with an industrial partner, that offered real-world projects to solve during the semester. This comparison can help determine significant differences in both groups in terms of developing subject competency and achieving sustainable development goals.

Write a Research Paper Introduction in Minutes with Paperpal

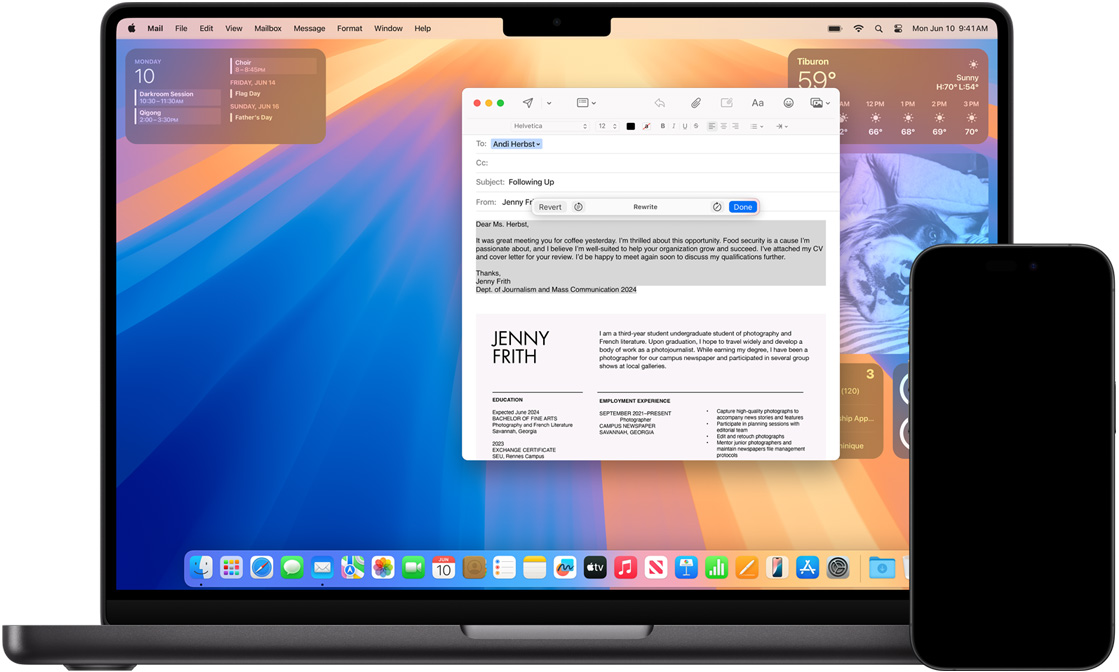

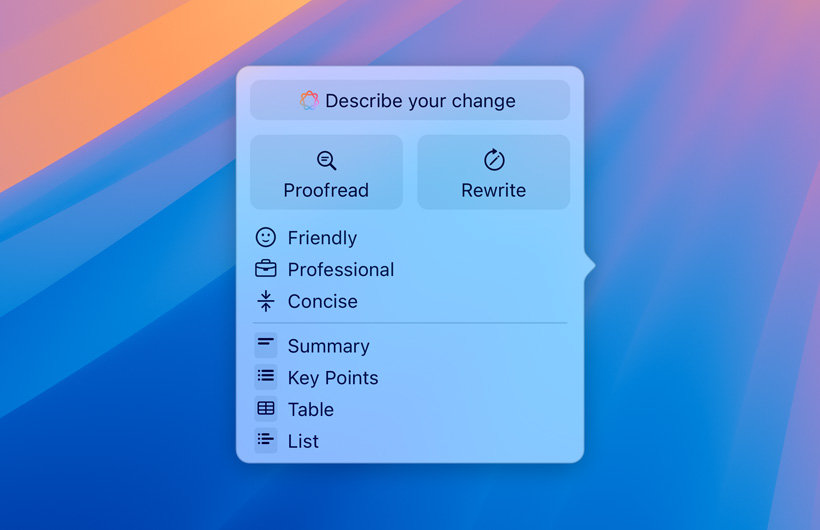

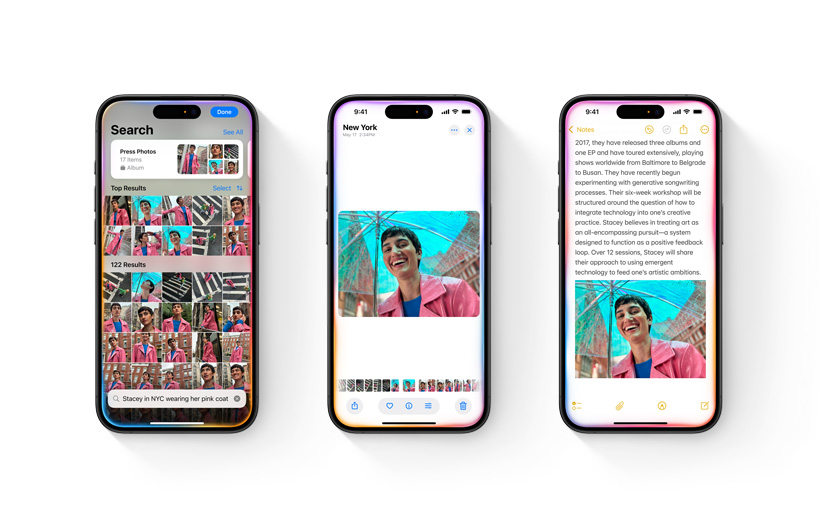

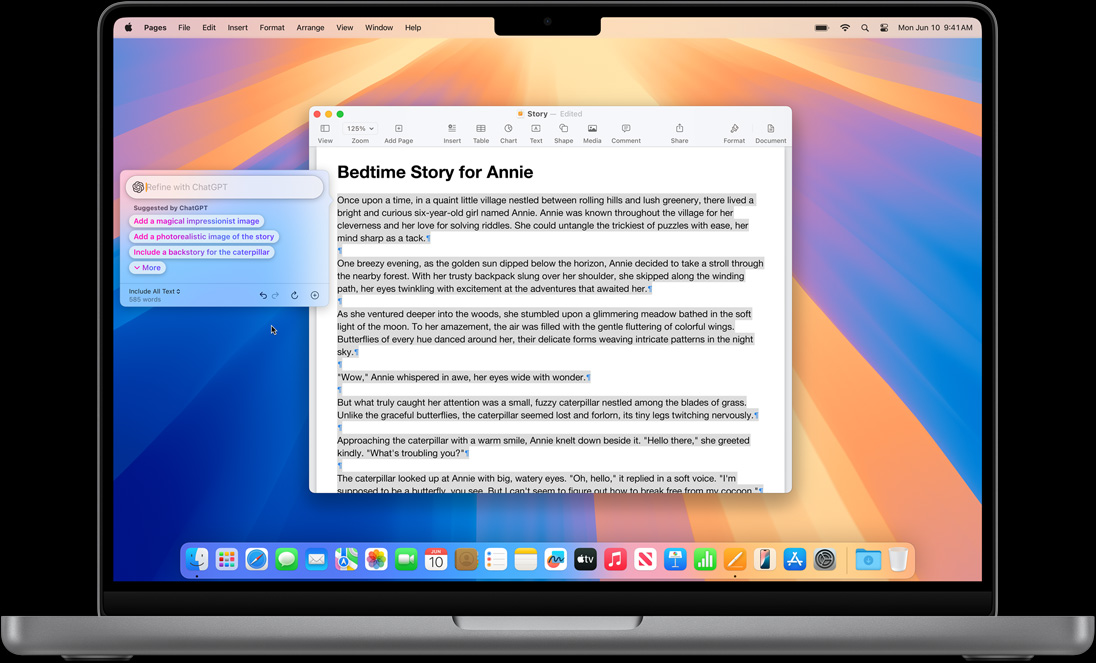

Paperpal Copilot is a generative AI-powered academic writing assistant. It’s trained on millions of published scholarly articles and over 20 years of STM experience. Paperpal Copilot helps authors write better and faster with:

- Real-time writing suggestions

- In-depth checks for language and grammar correction

- Paraphrasing to add variety, ensure academic tone, and trim text to meet journal limits

With Paperpal Copilot, create a research paper introduction effortlessly. In this step-by-step guide, we’ll walk you through how Paperpal transforms your initial ideas into a polished and publication-ready introduction.

How to use Paperpal to write the Introduction section

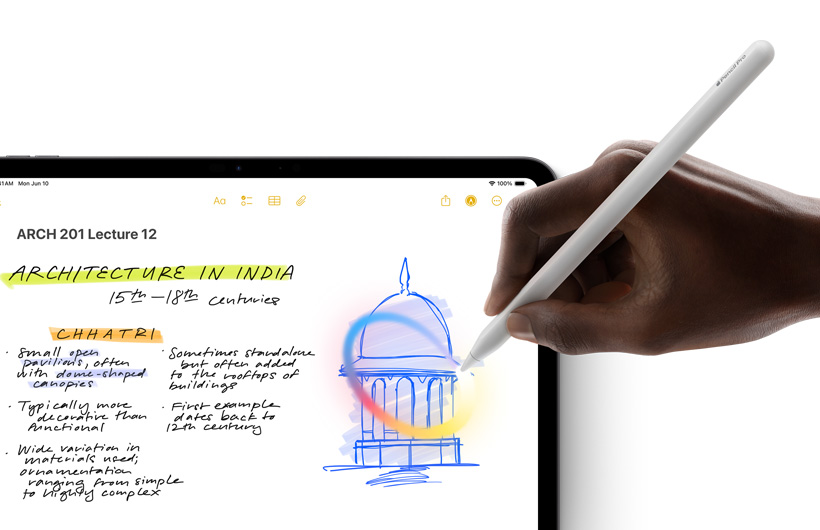

Step 1: Sign up on Paperpal and click on the Copilot feature, under this choose Outlines > Research Article > Introduction

Step 2: Add your unstructured notes or initial draft, whether in English or another language, to Paperpal, which is to be used as the base for your content.

Step 3: Fill in the specifics, such as your field of study, brief description or details you want to include, which will help the AI generate the outline for your Introduction.

Step 4: Use this outline and sentence suggestions to develop your content, adding citations where needed and modifying it to align with your specific research focus.

Step 5: Turn to Paperpal’s granular language checks to refine your content, tailor it to reflect your personal writing style, and ensure it effectively conveys your message.

You can use the same process to develop each section of your article, and finally your research paper in half the time and without any of the stress.

The purpose of the research paper introduction is to introduce the reader to the problem definition, justify the need for the study, and describe the main theme of the study. The aim is to gain the reader’s attention by providing them with necessary background information and establishing the main purpose and direction of the research.

The length of the research paper introduction can vary across journals and disciplines. While there are no strict word limits for writing the research paper introduction, an ideal length would be one page, with a maximum of 400 words over 1-4 paragraphs. Generally, it is one of the shorter sections of the paper as the reader is assumed to have at least a reasonable knowledge about the topic. 2 For example, for a study evaluating the role of building design in ensuring fire safety, there is no need to discuss definitions and nature of fire in the introduction; you could start by commenting upon the existing practices for fire safety and how your study will add to the existing knowledge and practice.

When deciding what to include in the research paper introduction, the rest of the paper should also be considered. The aim is to introduce the reader smoothly to the topic and facilitate an easy read without much dependency on external sources. 3 Below is a list of elements you can include to prepare a research paper introduction outline and follow it when you are writing the research paper introduction. Topic introduction: This can include key definitions and a brief history of the topic. Research context and background: Offer the readers some general information and then narrow it down to specific aspects. Details of the research you conducted: A brief literature review can be included to support your arguments or line of thought. Rationale for the study: This establishes the relevance of your study and establishes its importance. Importance of your research: The main contributions are highlighted to help establish the novelty of your study Research hypothesis: Introduce your research question and propose an expected outcome. Organization of the paper: Include a short paragraph of 3-4 sentences that highlights your plan for the entire paper

Cite only works that are most relevant to your topic; as a general rule, you can include one to three. Note that readers want to see evidence of original thinking. So it is better to avoid using too many references as it does not leave much room for your personal standpoint to shine through. Citations in your research paper introduction support the key points, and the number of citations depend on the subject matter and the point discussed. If the research paper introduction is too long or overflowing with citations, it is better to cite a few review articles rather than the individual articles summarized in the review. A good point to remember when citing research papers in the introduction section is to include at least one-third of the references in the introduction.

The literature review plays a significant role in the research paper introduction section. A good literature review accomplishes the following: Introduces the topic – Establishes the study’s significance – Provides an overview of the relevant literature – Provides context for the study using literature – Identifies knowledge gaps However, remember to avoid making the following mistakes when writing a research paper introduction: Do not use studies from the literature review to aggressively support your research Avoid direct quoting Do not allow literature review to be the focus of this section. Instead, the literature review should only aid in setting a foundation for the manuscript.

Remember the following key points for writing a good research paper introduction: 4

- Avoid stuffing too much general information: Avoid including what an average reader would know and include only that information related to the problem being addressed in the research paper introduction. For example, when describing a comparative study of non-traditional methods for mechanical design optimization, information related to the traditional methods and differences between traditional and non-traditional methods would not be relevant. In this case, the introduction for the research paper should begin with the state-of-the-art non-traditional methods and methods to evaluate the efficiency of newly developed algorithms.

- Avoid packing too many references: Cite only the required works in your research paper introduction. The other works can be included in the discussion section to strengthen your findings.

- Avoid extensive criticism of previous studies: Avoid being overly critical of earlier studies while setting the rationale for your study. A better place for this would be the Discussion section, where you can highlight the advantages of your method.

- Avoid describing conclusions of the study: When writing a research paper introduction remember not to include the findings of your study. The aim is to let the readers know what question is being answered. The actual answer should only be given in the Results and Discussion section.

To summarize, the research paper introduction section should be brief yet informative. It should convince the reader the need to conduct the study and motivate him to read further. If you’re feeling stuck or unsure, choose trusted AI academic writing assistants like Paperpal to effortlessly craft your research paper introduction and other sections of your research article.

1. Jawaid, S. A., & Jawaid, M. (2019). How to write introduction and discussion. Saudi Journal of Anaesthesia, 13(Suppl 1), S18.

2. Dewan, P., & Gupta, P. (2016). Writing the title, abstract and introduction: Looks matter!. Indian pediatrics, 53, 235-241.

3. Cetin, S., & Hackam, D. J. (2005). An approach to the writing of a scientific Manuscript1. Journal of Surgical Research, 128(2), 165-167.

4. Bavdekar, S. B. (2015). Writing introduction: Laying the foundations of a research paper. Journal of the Association of Physicians of India, 63(7), 44-6.

Paperpal is a comprehensive AI writing toolkit that helps students and researchers achieve 2x the writing in half the time. It leverages 21+ years of STM experience and insights from millions of research articles to provide in-depth academic writing, language editing, and submission readiness support to help you write better, faster.

Get accurate academic translations, rewriting support, grammar checks, vocabulary suggestions, and generative AI assistance that delivers human precision at machine speed. Try for free or upgrade to Paperpal Prime starting at US$19 a month to access premium features, including consistency, plagiarism, and 30+ submission readiness checks to help you succeed.

Experience the future of academic writing – Sign up to Paperpal and start writing for free!

Related Reads:

- Scientific Writing Style Guides Explained

- 5 Reasons for Rejection After Peer Review

- Ethical Research Practices For Research with Human Subjects

- 8 Most Effective Ways to Increase Motivation for Thesis Writing

Practice vs. Practise: Learn the Difference

Academic paraphrasing: why paperpal’s rewrite should be your first choice , you may also like, how to write the first draft of a..., mla works cited page: format, template & examples, how to write a high-quality conference paper, academic editing: how to self-edit academic text with..., measuring academic success: definition & strategies for excellence, phd qualifying exam: tips for success , ai in education: it’s time to change the..., is it ethical to use ai-generated abstracts without..., what are journal guidelines on using generative ai..., quillbot review: features, pricing, and free alternatives.

- Privacy Policy

Home » Research Paper Introduction – Writing Guide and Examples

Research Paper Introduction – Writing Guide and Examples

Table of Contents

Research Paper Introduction

Research paper introduction is the first section of a research paper that provides an overview of the study, its purpose, and the research question (s) or hypothesis (es) being investigated. It typically includes background information about the topic, a review of previous research in the field, and a statement of the research objectives. The introduction is intended to provide the reader with a clear understanding of the research problem, why it is important, and how the study will contribute to existing knowledge in the field. It also sets the tone for the rest of the paper and helps to establish the author’s credibility and expertise on the subject.

How to Write Research Paper Introduction

Writing an introduction for a research paper can be challenging because it sets the tone for the entire paper. Here are some steps to follow to help you write an effective research paper introduction:

- Start with a hook : Begin your introduction with an attention-grabbing statement, a question, or a surprising fact that will make the reader interested in reading further.

- Provide background information: After the hook, provide background information on the topic. This information should give the reader a general idea of what the topic is about and why it is important.

- State the research problem: Clearly state the research problem or question that the paper addresses. This should be done in a concise and straightforward manner.

- State the research objectives: After stating the research problem, clearly state the research objectives. This will give the reader an idea of what the paper aims to achieve.

- Provide a brief overview of the paper: At the end of the introduction, provide a brief overview of the paper. This should include a summary of the main points that will be discussed in the paper.

- Revise and refine: Finally, revise and refine your introduction to ensure that it is clear, concise, and engaging.

Structure of Research Paper Introduction

The following is a typical structure for a research paper introduction:

- Background Information: This section provides an overview of the topic of the research paper, including relevant background information and any previous research that has been done on the topic. It helps to give the reader a sense of the context for the study.

- Problem Statement: This section identifies the specific problem or issue that the research paper is addressing. It should be clear and concise, and it should articulate the gap in knowledge that the study aims to fill.

- Research Question/Hypothesis : This section states the research question or hypothesis that the study aims to answer. It should be specific and focused, and it should clearly connect to the problem statement.

- Significance of the Study: This section explains why the research is important and what the potential implications of the study are. It should highlight the contribution that the research makes to the field.

- Methodology: This section describes the research methods that were used to conduct the study. It should be detailed enough to allow the reader to understand how the study was conducted and to evaluate the validity of the results.

- Organization of the Paper : This section provides a brief overview of the structure of the research paper. It should give the reader a sense of what to expect in each section of the paper.

Research Paper Introduction Examples

Research Paper Introduction Examples could be:

Example 1: In recent years, the use of artificial intelligence (AI) has become increasingly prevalent in various industries, including healthcare. AI algorithms are being developed to assist with medical diagnoses, treatment recommendations, and patient monitoring. However, as the use of AI in healthcare grows, ethical concerns regarding privacy, bias, and accountability have emerged. This paper aims to explore the ethical implications of AI in healthcare and propose recommendations for addressing these concerns.

Example 2: Climate change is one of the most pressing issues facing our planet today. The increasing concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere has resulted in rising temperatures, changing weather patterns, and other environmental impacts. In this paper, we will review the scientific evidence on climate change, discuss the potential consequences of inaction, and propose solutions for mitigating its effects.

Example 3: The rise of social media has transformed the way we communicate and interact with each other. While social media platforms offer many benefits, including increased connectivity and access to information, they also present numerous challenges. In this paper, we will examine the impact of social media on mental health, privacy, and democracy, and propose solutions for addressing these issues.

Example 4: The use of renewable energy sources has become increasingly important in the face of climate change and environmental degradation. While renewable energy technologies offer many benefits, including reduced greenhouse gas emissions and energy independence, they also present numerous challenges. In this paper, we will assess the current state of renewable energy technology, discuss the economic and political barriers to its adoption, and propose solutions for promoting the widespread use of renewable energy.

Purpose of Research Paper Introduction

The introduction section of a research paper serves several important purposes, including:

- Providing context: The introduction should give readers a general understanding of the topic, including its background, significance, and relevance to the field.

- Presenting the research question or problem: The introduction should clearly state the research question or problem that the paper aims to address. This helps readers understand the purpose of the study and what the author hopes to accomplish.

- Reviewing the literature: The introduction should summarize the current state of knowledge on the topic, highlighting the gaps and limitations in existing research. This shows readers why the study is important and necessary.

- Outlining the scope and objectives of the study: The introduction should describe the scope and objectives of the study, including what aspects of the topic will be covered, what data will be collected, and what methods will be used.

- Previewing the main findings and conclusions : The introduction should provide a brief overview of the main findings and conclusions that the study will present. This helps readers anticipate what they can expect to learn from the paper.

When to Write Research Paper Introduction

The introduction of a research paper is typically written after the research has been conducted and the data has been analyzed. This is because the introduction should provide an overview of the research problem, the purpose of the study, and the research questions or hypotheses that will be investigated.

Once you have a clear understanding of the research problem and the questions that you want to explore, you can begin to write the introduction. It’s important to keep in mind that the introduction should be written in a way that engages the reader and provides a clear rationale for the study. It should also provide context for the research by reviewing relevant literature and explaining how the study fits into the larger field of research.

Advantages of Research Paper Introduction

The introduction of a research paper has several advantages, including:

- Establishing the purpose of the research: The introduction provides an overview of the research problem, question, or hypothesis, and the objectives of the study. This helps to clarify the purpose of the research and provide a roadmap for the reader to follow.

- Providing background information: The introduction also provides background information on the topic, including a review of relevant literature and research. This helps the reader understand the context of the study and how it fits into the broader field of research.

- Demonstrating the significance of the research: The introduction also explains why the research is important and relevant. This helps the reader understand the value of the study and why it is worth reading.

- Setting expectations: The introduction sets the tone for the rest of the paper and prepares the reader for what is to come. This helps the reader understand what to expect and how to approach the paper.

- Grabbing the reader’s attention: A well-written introduction can grab the reader’s attention and make them interested in reading further. This is important because it can help to keep the reader engaged and motivated to read the rest of the paper.

- Creating a strong first impression: The introduction is the first part of the research paper that the reader will see, and it can create a strong first impression. A well-written introduction can make the reader more likely to take the research seriously and view it as credible.

- Establishing the author’s credibility: The introduction can also establish the author’s credibility as a researcher. By providing a clear and thorough overview of the research problem and relevant literature, the author can demonstrate their expertise and knowledge in the field.

- Providing a structure for the paper: The introduction can also provide a structure for the rest of the paper. By outlining the main sections and sub-sections of the paper, the introduction can help the reader navigate the paper and find the information they are looking for.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Research Paper Abstract – Writing Guide and...

Research Results Section – Writing Guide and...

APA Research Paper Format – Example, Sample and...

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Appendices – Writing Guide, Types and Examples

Research Paper Format – Types, Examples and...

- If you are writing in a new discipline, you should always make sure to ask about conventions and expectations for introductions, just as you would for any other aspect of the essay. For example, while it may be acceptable to write a two-paragraph (or longer) introduction for your papers in some courses, instructors in other disciplines, such as those in some Government courses, may expect a shorter introduction that includes a preview of the argument that will follow.

- In some disciplines (Government, Economics, and others), it’s common to offer an overview in the introduction of what points you will make in your essay. In other disciplines, you will not be expected to provide this overview in your introduction.

- Avoid writing a very general opening sentence. While it may be true that “Since the dawn of time, people have been telling love stories,” it won’t help you explain what’s interesting about your topic.

- Avoid writing a “funnel” introduction in which you begin with a very broad statement about a topic and move to a narrow statement about that topic. Broad generalizations about a topic will not add to your readers’ understanding of your specific essay topic.

- Avoid beginning with a dictionary definition of a term or concept you will be writing about. If the concept is complicated or unfamiliar to your readers, you will need to define it in detail later in your essay. If it’s not complicated, you can assume your readers already know the definition.

- Avoid offering too much detail in your introduction that a reader could better understand later in the paper.

- picture_as_pdf Introductions

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- 4. The Introduction

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

The introduction leads the reader from a general subject area to a particular topic of inquiry. It establishes the scope, context, and significance of the research being conducted by summarizing current understanding and background information about the topic, stating the purpose of the work in the form of the research problem supported by a hypothesis or a set of questions, explaining briefly the methodological approach used to examine the research problem, highlighting the potential outcomes your study can reveal, and outlining the remaining structure and organization of the paper.

Key Elements of the Research Proposal. Prepared under the direction of the Superintendent and by the 2010 Curriculum Design and Writing Team. Baltimore County Public Schools.

Importance of a Good Introduction

Think of the introduction as a mental road map that must answer for the reader these four questions:

- What was I studying?

- Why was this topic important to investigate?

- What did we know about this topic before I did this study?

- How will this study advance new knowledge or new ways of understanding?

According to Reyes, there are three overarching goals of a good introduction: 1) ensure that you summarize prior studies about the topic in a manner that lays a foundation for understanding the research problem; 2) explain how your study specifically addresses gaps in the literature, insufficient consideration of the topic, or other deficiency in the literature; and, 3) note the broader theoretical, empirical, and/or policy contributions and implications of your research.

A well-written introduction is important because, quite simply, you never get a second chance to make a good first impression. The opening paragraphs of your paper will provide your readers with their initial impressions about the logic of your argument, your writing style, the overall quality of your research, and, ultimately, the validity of your findings and conclusions. A vague, disorganized, or error-filled introduction will create a negative impression, whereas, a concise, engaging, and well-written introduction will lead your readers to think highly of your analytical skills, your writing style, and your research approach. All introductions should conclude with a brief paragraph that describes the organization of the rest of the paper.

Hirano, Eliana. “Research Article Introductions in English for Specific Purposes: A Comparison between Brazilian, Portuguese, and English.” English for Specific Purposes 28 (October 2009): 240-250; Samraj, B. “Introductions in Research Articles: Variations Across Disciplines.” English for Specific Purposes 21 (2002): 1–17; Introductions. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; “Writing Introductions.” In Good Essay Writing: A Social Sciences Guide. Peter Redman. 4th edition. (London: Sage, 2011), pp. 63-70; Reyes, Victoria. Demystifying the Journal Article. Inside Higher Education.

Structure and Writing Style

I. Structure and Approach

The introduction is the broad beginning of the paper that answers three important questions for the reader:

- What is this?

- Why should I read it?

- What do you want me to think about / consider doing / react to?

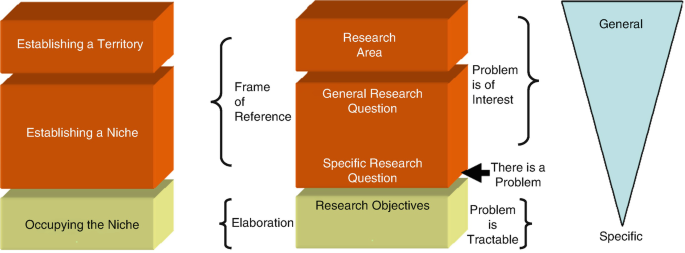

Think of the structure of the introduction as an inverted triangle of information that lays a foundation for understanding the research problem. Organize the information so as to present the more general aspects of the topic early in the introduction, then narrow your analysis to more specific topical information that provides context, finally arriving at your research problem and the rationale for studying it [often written as a series of key questions to be addressed or framed as a hypothesis or set of assumptions to be tested] and, whenever possible, a description of the potential outcomes your study can reveal.

These are general phases associated with writing an introduction: 1. Establish an area to research by:

- Highlighting the importance of the topic, and/or

- Making general statements about the topic, and/or

- Presenting an overview on current research on the subject.

2. Identify a research niche by:

- Opposing an existing assumption, and/or

- Revealing a gap in existing research, and/or

- Formulating a research question or problem, and/or

- Continuing a disciplinary tradition.

3. Place your research within the research niche by:

- Stating the intent of your study,

- Outlining the key characteristics of your study,

- Describing important results, and

- Giving a brief overview of the structure of the paper.

NOTE: It is often useful to review the introduction late in the writing process. This is appropriate because outcomes are unknown until you've completed the study. After you complete writing the body of the paper, go back and review introductory descriptions of the structure of the paper, the method of data gathering, the reporting and analysis of results, and the conclusion. Reviewing and, if necessary, rewriting the introduction ensures that it correctly matches the overall structure of your final paper.

II. Delimitations of the Study

Delimitations refer to those characteristics that limit the scope and define the conceptual boundaries of your research . This is determined by the conscious exclusionary and inclusionary decisions you make about how to investigate the research problem. In other words, not only should you tell the reader what it is you are studying and why, but you must also acknowledge why you rejected alternative approaches that could have been used to examine the topic.

Obviously, the first limiting step was the choice of research problem itself. However, implicit are other, related problems that could have been chosen but were rejected. These should be noted in the conclusion of your introduction. For example, a delimitating statement could read, "Although many factors can be understood to impact the likelihood young people will vote, this study will focus on socioeconomic factors related to the need to work full-time while in school." The point is not to document every possible delimiting factor, but to highlight why previously researched issues related to the topic were not addressed.

Examples of delimitating choices would be:

- The key aims and objectives of your study,

- The research questions that you address,

- The variables of interest [i.e., the various factors and features of the phenomenon being studied],

- The method(s) of investigation,

- The time period your study covers, and

- Any relevant alternative theoretical frameworks that could have been adopted.

Review each of these decisions. Not only do you clearly establish what you intend to accomplish in your research, but you should also include a declaration of what the study does not intend to cover. In the latter case, your exclusionary decisions should be based upon criteria understood as, "not interesting"; "not directly relevant"; “too problematic because..."; "not feasible," and the like. Make this reasoning explicit!

NOTE: Delimitations refer to the initial choices made about the broader, overall design of your study and should not be confused with documenting the limitations of your study discovered after the research has been completed.

ANOTHER NOTE: Do not view delimitating statements as admitting to an inherent failing or shortcoming in your research. They are an accepted element of academic writing intended to keep the reader focused on the research problem by explicitly defining the conceptual boundaries and scope of your study. It addresses any critical questions in the reader's mind of, "Why the hell didn't the author examine this?"

III. The Narrative Flow

Issues to keep in mind that will help the narrative flow in your introduction :

- Your introduction should clearly identify the subject area of interest . A simple strategy to follow is to use key words from your title in the first few sentences of the introduction. This will help focus the introduction on the topic at the appropriate level and ensures that you get to the subject matter quickly without losing focus, or discussing information that is too general.

- Establish context by providing a brief and balanced review of the pertinent published literature that is available on the subject. The key is to summarize for the reader what is known about the specific research problem before you did your analysis. This part of your introduction should not represent a comprehensive literature review--that comes next. It consists of a general review of the important, foundational research literature [with citations] that establishes a foundation for understanding key elements of the research problem. See the drop-down menu under this tab for " Background Information " regarding types of contexts.

- Clearly state the hypothesis that you investigated . When you are first learning to write in this format it is okay, and actually preferable, to use a past statement like, "The purpose of this study was to...." or "We investigated three possible mechanisms to explain the...."

- Why did you choose this kind of research study or design? Provide a clear statement of the rationale for your approach to the problem studied. This will usually follow your statement of purpose in the last paragraph of the introduction.

IV. Engaging the Reader

A research problem in the social sciences can come across as dry and uninteresting to anyone unfamiliar with the topic . Therefore, one of the goals of your introduction is to make readers want to read your paper. Here are several strategies you can use to grab the reader's attention:

- Open with a compelling story . Almost all research problems in the social sciences, no matter how obscure or esoteric , are really about the lives of people. Telling a story that humanizes an issue can help illuminate the significance of the problem and help the reader empathize with those affected by the condition being studied.

- Include a strong quotation or a vivid, perhaps unexpected, anecdote . During your review of the literature, make note of any quotes or anecdotes that grab your attention because they can used in your introduction to highlight the research problem in a captivating way.

- Pose a provocative or thought-provoking question . Your research problem should be framed by a set of questions to be addressed or hypotheses to be tested. However, a provocative question can be presented in the beginning of your introduction that challenges an existing assumption or compels the reader to consider an alternative viewpoint that helps establish the significance of your study.

- Describe a puzzling scenario or incongruity . This involves highlighting an interesting quandary concerning the research problem or describing contradictory findings from prior studies about a topic. Posing what is essentially an unresolved intellectual riddle about the problem can engage the reader's interest in the study.

- Cite a stirring example or case study that illustrates why the research problem is important . Draw upon the findings of others to demonstrate the significance of the problem and to describe how your study builds upon or offers alternatives ways of investigating this prior research.

NOTE: It is important that you choose only one of the suggested strategies for engaging your readers. This avoids giving an impression that your paper is more flash than substance and does not distract from the substance of your study.

Freedman, Leora and Jerry Plotnick. Introductions and Conclusions. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Introduction. The Structure, Format, Content, and Style of a Journal-Style Scientific Paper. Department of Biology. Bates College; Introductions. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Introductions. The Writer’s Handbook. Writing Center. University of Wisconsin, Madison; Introductions, Body Paragraphs, and Conclusions for an Argument Paper. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; “Writing Introductions.” In Good Essay Writing: A Social Sciences Guide . Peter Redman. 4th edition. (London: Sage, 2011), pp. 63-70; Resources for Writers: Introduction Strategies. Program in Writing and Humanistic Studies. Massachusetts Institute of Technology; Sharpling, Gerald. Writing an Introduction. Centre for Applied Linguistics, University of Warwick; Samraj, B. “Introductions in Research Articles: Variations Across Disciplines.” English for Specific Purposes 21 (2002): 1–17; Swales, John and Christine B. Feak. Academic Writing for Graduate Students: Essential Skills and Tasks . 2nd edition. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2004 ; Writing Your Introduction. Department of English Writing Guide. George Mason University.

Writing Tip

Avoid the "Dictionary" Introduction

Giving the dictionary definition of words related to the research problem may appear appropriate because it is important to define specific terminology that readers may be unfamiliar with. However, anyone can look a word up in the dictionary and a general dictionary is not a particularly authoritative source because it doesn't take into account the context of your topic and doesn't offer particularly detailed information. Also, placed in the context of a particular discipline, a term or concept may have a different meaning than what is found in a general dictionary. If you feel that you must seek out an authoritative definition, use a subject specific dictionary or encyclopedia [e.g., if you are a sociology student, search for dictionaries of sociology]. A good database for obtaining definitive definitions of concepts or terms is Credo Reference .

Saba, Robert. The College Research Paper. Florida International University; Introductions. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina.

Another Writing Tip

When Do I Begin?

A common question asked at the start of any paper is, "Where should I begin?" An equally important question to ask yourself is, "When do I begin?" Research problems in the social sciences rarely rest in isolation from history. Therefore, it is important to lay a foundation for understanding the historical context underpinning the research problem. However, this information should be brief and succinct and begin at a point in time that illustrates the study's overall importance. For example, a study that investigates coffee cultivation and export in West Africa as a key stimulus for local economic growth needs to describe the beginning of exporting coffee in the region and establishing why economic growth is important. You do not need to give a long historical explanation about coffee exports in Africa. If a research problem requires a substantial exploration of the historical context, do this in the literature review section. In your introduction, make note of this as part of the "roadmap" [see below] that you use to describe the organization of your paper.

Introductions. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; “Writing Introductions.” In Good Essay Writing: A Social Sciences Guide . Peter Redman. 4th edition. (London: Sage, 2011), pp. 63-70.

Yet Another Writing Tip

Always End with a Roadmap

The final paragraph or sentences of your introduction should forecast your main arguments and conclusions and provide a brief description of the rest of the paper [the "roadmap"] that let's the reader know where you are going and what to expect. A roadmap is important because it helps the reader place the research problem within the context of their own perspectives about the topic. In addition, concluding your introduction with an explicit roadmap tells the reader that you have a clear understanding of the structural purpose of your paper. In this way, the roadmap acts as a type of promise to yourself and to your readers that you will follow a consistent and coherent approach to addressing the topic of inquiry. Refer to it often to help keep your writing focused and organized.

Cassuto, Leonard. “On the Dissertation: How to Write the Introduction.” The Chronicle of Higher Education , May 28, 2018; Radich, Michael. A Student's Guide to Writing in East Asian Studies . (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Writing n. d.), pp. 35-37.

- << Previous: Executive Summary

- Next: The C.A.R.S. Model >>

- Last Updated: Jun 18, 2024 10:45 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

Microsoft 365 Life Hacks > Writing > How to write an introduction for a research paper

How to write an introduction for a research paper

Beginnings are hard. Beginning a research paper is no exception. Many students—and pros—struggle with how to write an introduction for a research paper.

This short guide will describe the purpose of a research paper introduction and how to create a good one.

What is an introduction for a research paper?

Introductions to research papers do a lot of work.

It may seem obvious, but introductions are always placed at the beginning of a paper. They guide your reader from a general subject area to the narrow topic that your paper covers. They also explain your paper’s:

- Scope: The topic you’ll be covering

- Context: The background of your topic

- Importance: Why your research matters in the context of an industry or the world

Your introduction will cover a lot of ground. However, it will only be half of a page to a few pages long. The length depends on the size of your paper as a whole. In many cases, the introduction will be shorter than all of the other sections of your paper.

Write with Confidence using Editor

Elevate your writing with real-time, intelligent assistance

Why is an introduction vital to a research paper?

The introduction to your research paper isn’t just important. It’s critical.

Your readers don’t know what your research paper is about from the title. That’s where your introduction comes in. A good introduction will:

- Help your reader understand your topic’s background

- Explain why your research paper is worth reading

- Offer a guide for navigating the rest of the piece

- Pique your reader’s interest

Without a clear introduction, your readers will struggle. They may feel confused when they start reading your paper. They might even give up entirely. Your introduction will ground them and prepare them for the in-depth research to come.

What should you include in an introduction for a research paper?

Research paper introductions are always unique. After all, research is original by definition. However, they often contain six essential items. These are:

- An overview of the topic. Start with a general overview of your topic. Narrow the overview until you address your paper’s specific subject. Then, mention questions or concerns you had about the case. Note that you will address them in the publication.

- Prior research. Your introduction is the place to review other conclusions on your topic. Include both older scholars and modern scholars. This background information shows that you are aware of prior research. It also introduces past findings to those who might not have that expertise.

- A rationale for your paper. Explain why your topic needs to be addressed right now. If applicable, connect it to current issues. Additionally, you can show a problem with former theories or reveal a gap in current research. No matter how you do it, a good rationale will interest your readers and demonstrate why they must read the rest of your paper.

- Describe the methodology you used. Recount your processes to make your paper more credible. Lay out your goal and the questions you will address. Reveal how you conducted research and describe how you measured results. Moreover, explain why you made key choices.

- A thesis statement. Your main introduction should end with a thesis statement. This statement summarizes the ideas that will run through your entire research article. It should be straightforward and clear.

- An outline. Introductions often conclude with an outline. Your layout should quickly review what you intend to cover in the following sections. Think of it as a roadmap, guiding your reader to the end of your paper.

These six items are emphasized more or less, depending on your field. For example, a physics research paper might emphasize methodology. An English journal article might highlight the overview.

Three tips for writing your introduction

We don’t just want you to learn how to write an introduction for a research paper. We want you to learn how to make it shine.

There are three things you can do that will make it easier to write a great introduction. You can:

- Write your introduction last. An introduction summarizes all of the things you’ve learned from your research. While it can feel good to get your preface done quickly, you should write the rest of your paper first. Then, you’ll find it easy to create a clear overview.

- Include a strong quotation or story upfront. You want your paper to be full of substance. But that doesn’t mean it should feel boring or flat. Add a relevant quotation or surprising anecdote to the beginning of your introduction. This technique will pique the interest of your reader and leave them wanting more.

- Be concise. Research papers cover complex topics. To help your readers, try to write as clearly as possible. Use concise sentences. Check for confusing grammar or syntax . Read your introduction out loud to catch awkward phrases. Before you finish your paper, be sure to proofread, too. Mistakes can seem unprofessional.

Get started with Microsoft 365

It’s the Office you know, plus the tools to help you work better together, so you can get more done—anytime, anywhere.

Topics in this article

More articles like this one.

What is independent publishing?

Avoid the hassle of shopping your book around to publishing houses. Publish your book independently and understand the benefits it provides for your as an author.

What are literary tropes?

Engage your audience with literary tropes. Learn about different types of literary tropes, like metaphors and oxymorons, to elevate your writing.

What are genre tropes?

Your favorite genres are filled with unifying tropes that can define them or are meant to be subverted.

What is literary fiction?

Define literary fiction and learn what sets it apart from genre fiction.

Everything you need to achieve more in less time

Get powerful productivity and security apps with Microsoft 365

Explore Other Categories

Introductions

What this handout is about.

This handout will explain the functions of introductions, offer strategies for creating effective introductions, and provide some examples of less effective introductions to avoid.

The role of introductions

Introductions and conclusions can be the most difficult parts of papers to write. Usually when you sit down to respond to an assignment, you have at least some sense of what you want to say in the body of your paper. You might have chosen a few examples you want to use or have an idea that will help you answer the main question of your assignment; these sections, therefore, may not be as hard to write. And it’s fine to write them first! But in your final draft, these middle parts of the paper can’t just come out of thin air; they need to be introduced and concluded in a way that makes sense to your reader.

Your introduction and conclusion act as bridges that transport your readers from their own lives into the “place” of your analysis. If your readers pick up your paper about education in the autobiography of Frederick Douglass, for example, they need a transition to help them leave behind the world of Chapel Hill, television, e-mail, and The Daily Tar Heel and to help them temporarily enter the world of nineteenth-century American slavery. By providing an introduction that helps your readers make a transition between their own world and the issues you will be writing about, you give your readers the tools they need to get into your topic and care about what you are saying. Similarly, once you’ve hooked your readers with the introduction and offered evidence to prove your thesis, your conclusion can provide a bridge to help your readers make the transition back to their daily lives. (See our handout on conclusions .)

Note that what constitutes a good introduction may vary widely based on the kind of paper you are writing and the academic discipline in which you are writing it. If you are uncertain what kind of introduction is expected, ask your instructor.

Why bother writing a good introduction?

You never get a second chance to make a first impression. The opening paragraph of your paper will provide your readers with their initial impressions of your argument, your writing style, and the overall quality of your work. A vague, disorganized, error-filled, off-the-wall, or boring introduction will probably create a negative impression. On the other hand, a concise, engaging, and well-written introduction will start your readers off thinking highly of you, your analytical skills, your writing, and your paper.

Your introduction is an important road map for the rest of your paper. Your introduction conveys a lot of information to your readers. You can let them know what your topic is, why it is important, and how you plan to proceed with your discussion. In many academic disciplines, your introduction should contain a thesis that will assert your main argument. Your introduction should also give the reader a sense of the kinds of information you will use to make that argument and the general organization of the paragraphs and pages that will follow. After reading your introduction, your readers should not have any major surprises in store when they read the main body of your paper.

Ideally, your introduction will make your readers want to read your paper. The introduction should capture your readers’ interest, making them want to read the rest of your paper. Opening with a compelling story, an interesting question, or a vivid example can get your readers to see why your topic matters and serve as an invitation for them to join you for an engaging intellectual conversation (remember, though, that these strategies may not be suitable for all papers and disciplines).

Strategies for writing an effective introduction

Start by thinking about the question (or questions) you are trying to answer. Your entire essay will be a response to this question, and your introduction is the first step toward that end. Your direct answer to the assigned question will be your thesis, and your thesis will likely be included in your introduction, so it is a good idea to use the question as a jumping off point. Imagine that you are assigned the following question:

Drawing on the Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass , discuss the relationship between education and slavery in 19th-century America. Consider the following: How did white control of education reinforce slavery? How did Douglass and other enslaved African Americans view education while they endured slavery? And what role did education play in the acquisition of freedom? Most importantly, consider the degree to which education was or was not a major force for social change with regard to slavery.

You will probably refer back to your assignment extensively as you prepare your complete essay, and the prompt itself can also give you some clues about how to approach the introduction. Notice that it starts with a broad statement and then narrows to focus on specific questions from the book. One strategy might be to use a similar model in your own introduction—start off with a big picture sentence or two and then focus in on the details of your argument about Douglass. Of course, a different approach could also be very successful, but looking at the way the professor set up the question can sometimes give you some ideas for how you might answer it. (See our handout on understanding assignments for additional information on the hidden clues in assignments.)

Decide how general or broad your opening should be. Keep in mind that even a “big picture” opening needs to be clearly related to your topic; an opening sentence that said “Human beings, more than any other creatures on earth, are capable of learning” would be too broad for our sample assignment about slavery and education. If you have ever used Google Maps or similar programs, that experience can provide a helpful way of thinking about how broad your opening should be. Imagine that you’re researching Chapel Hill. If what you want to find out is whether Chapel Hill is at roughly the same latitude as Rome, it might make sense to hit that little “minus” sign on the online map until it has zoomed all the way out and you can see the whole globe. If you’re trying to figure out how to get from Chapel Hill to Wrightsville Beach, it might make more sense to zoom in to the level where you can see most of North Carolina (but not the rest of the world, or even the rest of the United States). And if you are looking for the intersection of Ridge Road and Manning Drive so that you can find the Writing Center’s main office, you may need to zoom all the way in. The question you are asking determines how “broad” your view should be. In the sample assignment above, the questions are probably at the “state” or “city” level of generality. When writing, you need to place your ideas in context—but that context doesn’t generally have to be as big as the whole galaxy!

Try writing your introduction last. You may think that you have to write your introduction first, but that isn’t necessarily true, and it isn’t always the most effective way to craft a good introduction. You may find that you don’t know precisely what you are going to argue at the beginning of the writing process. It is perfectly fine to start out thinking that you want to argue a particular point but wind up arguing something slightly or even dramatically different by the time you’ve written most of the paper. The writing process can be an important way to organize your ideas, think through complicated issues, refine your thoughts, and develop a sophisticated argument. However, an introduction written at the beginning of that discovery process will not necessarily reflect what you wind up with at the end. You will need to revise your paper to make sure that the introduction, all of the evidence, and the conclusion reflect the argument you intend. Sometimes it’s easiest to just write up all of your evidence first and then write the introduction last—that way you can be sure that the introduction will match the body of the paper.

Don’t be afraid to write a tentative introduction first and then change it later. Some people find that they need to write some kind of introduction in order to get the writing process started. That’s fine, but if you are one of those people, be sure to return to your initial introduction later and rewrite if necessary.

Open with something that will draw readers in. Consider these options (remembering that they may not be suitable for all kinds of papers):

- an intriguing example —for example, Douglass writes about a mistress who initially teaches him but then ceases her instruction as she learns more about slavery.

- a provocative quotation that is closely related to your argument —for example, Douglass writes that “education and slavery were incompatible with each other.” (Quotes from famous people, inspirational quotes, etc. may not work well for an academic paper; in this example, the quote is from the author himself.)

- a puzzling scenario —for example, Frederick Douglass says of slaves that “[N]othing has been left undone to cripple their intellects, darken their minds, debase their moral nature, obliterate all traces of their relationship to mankind; and yet how wonderfully they have sustained the mighty load of a most frightful bondage, under which they have been groaning for centuries!” Douglass clearly asserts that slave owners went to great lengths to destroy the mental capacities of slaves, yet his own life story proves that these efforts could be unsuccessful.

- a vivid and perhaps unexpected anecdote —for example, “Learning about slavery in the American history course at Frederick Douglass High School, students studied the work slaves did, the impact of slavery on their families, and the rules that governed their lives. We didn’t discuss education, however, until one student, Mary, raised her hand and asked, ‘But when did they go to school?’ That modern high school students could not conceive of an American childhood devoid of formal education speaks volumes about the centrality of education to American youth today and also suggests the significance of the deprivation of education in past generations.”

- a thought-provoking question —for example, given all of the freedoms that were denied enslaved individuals in the American South, why does Frederick Douglass focus his attentions so squarely on education and literacy?

Pay special attention to your first sentence. Start off on the right foot with your readers by making sure that the first sentence actually says something useful and that it does so in an interesting and polished way.

How to evaluate your introduction draft

Ask a friend to read your introduction and then tell you what they expect the paper will discuss, what kinds of evidence the paper will use, and what the tone of the paper will be. If your friend is able to predict the rest of your paper accurately, you probably have a good introduction.

Five kinds of less effective introductions

1. The placeholder introduction. When you don’t have much to say on a given topic, it is easy to create this kind of introduction. Essentially, this kind of weaker introduction contains several sentences that are vague and don’t really say much. They exist just to take up the “introduction space” in your paper. If you had something more effective to say, you would probably say it, but in the meantime this paragraph is just a place holder.

Example: Slavery was one of the greatest tragedies in American history. There were many different aspects of slavery. Each created different kinds of problems for enslaved people.

2. The restated question introduction. Restating the question can sometimes be an effective strategy, but it can be easy to stop at JUST restating the question instead of offering a more specific, interesting introduction to your paper. The professor or teaching assistant wrote your question and will be reading many essays in response to it—they do not need to read a whole paragraph that simply restates the question.

Example: The Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass discusses the relationship between education and slavery in 19th century America, showing how white control of education reinforced slavery and how Douglass and other enslaved African Americans viewed education while they endured. Moreover, the book discusses the role that education played in the acquisition of freedom. Education was a major force for social change with regard to slavery.

3. The Webster’s Dictionary introduction. This introduction begins by giving the dictionary definition of one or more of the words in the assigned question. Anyone can look a word up in the dictionary and copy down what Webster says. If you want to open with a discussion of an important term, it may be far more interesting for you (and your reader) if you develop your own definition of the term in the specific context of your class and assignment. You may also be able to use a definition from one of the sources you’ve been reading for class. Also recognize that the dictionary is also not a particularly authoritative work—it doesn’t take into account the context of your course and doesn’t offer particularly detailed information. If you feel that you must seek out an authority, try to find one that is very relevant and specific. Perhaps a quotation from a source reading might prove better? Dictionary introductions are also ineffective simply because they are so overused. Instructors may see a great many papers that begin in this way, greatly decreasing the dramatic impact that any one of those papers will have.

Example: Webster’s dictionary defines slavery as “the state of being a slave,” as “the practice of owning slaves,” and as “a condition of hard work and subjection.”

4. The “dawn of man” introduction. This kind of introduction generally makes broad, sweeping statements about the relevance of this topic since the beginning of time, throughout the world, etc. It is usually very general (similar to the placeholder introduction) and fails to connect to the thesis. It may employ cliches—the phrases “the dawn of man” and “throughout human history” are examples, and it’s hard to imagine a time when starting with one of these would work. Instructors often find them extremely annoying.

Example: Since the dawn of man, slavery has been a problem in human history.

5. The book report introduction. This introduction is what you had to do for your elementary school book reports. It gives the name and author of the book you are writing about, tells what the book is about, and offers other basic facts about the book. You might resort to this sort of introduction when you are trying to fill space because it’s a familiar, comfortable format. It is ineffective because it offers details that your reader probably already knows and that are irrelevant to the thesis.

Example: Frederick Douglass wrote his autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave , in the 1840s. It was published in 1986 by Penguin Books. In it, he tells the story of his life.

And now for the conclusion…

Writing an effective introduction can be tough. Try playing around with several different options and choose the one that ends up sounding best to you!

Just as your introduction helps readers make the transition to your topic, your conclusion needs to help them return to their daily lives–but with a lasting sense of how what they have just read is useful or meaningful. Check out our handout on conclusions for tips on ending your paper as effectively as you began it!

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Douglass, Frederick. 1995. Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, Written by Himself . New York: Dover.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

- Resources Home 🏠

- Try SciSpace Copilot

- Search research papers

- Add Copilot Extension

- Try AI Detector

- Try Paraphraser

- Try Citation Generator

- April Papers

- June Papers

- July Papers

How to Write an Introduction for a Research Paper

Table of Contents

Writing an introduction for a research paper is a critical element of your paper, but it can seem challenging to encapsulate enormous amount of information into a concise form. The introduction of your research paper sets the tone for your research and provides the context for your study. In this article, we will guide you through the process of writing an effective introduction that grabs the reader's attention and captures the essence of your research paper.

Understanding the Purpose of a Research Paper Introduction

The introduction acts as a road map for your research paper, guiding the reader through the main ideas and arguments. The purpose of the introduction is to present your research topic to the readers and provide a rationale for why your study is relevant. It helps the reader locate your research and its relevance in the broader field of related scientific explorations. Additionally, the introduction should inform the reader about the objectives and scope of your study, giving them an overview of what to expect in the paper. By including a comprehensive introduction, you establish your credibility as an author and convince the reader that your research is worth their time and attention.

Key Elements to Include in Your Introduction

When writing your research paper introduction, there are several key elements you should include to ensure it is comprehensive and informative.

- A hook or attention-grabbing statement to capture the reader's interest. It can be a thought-provoking question, a surprising statistic, or a compelling anecdote that relates to your research topic.

- A brief overview of the research topic and its significance. By highlighting the gap in existing knowledge or the problem your research aims to address, you create a compelling case for the relevance of your study.

- A clear research question or problem statement. This serves as the foundation of your research and guides the reader in understanding the unique focus of your study. It should be concise, specific, and clearly articulated.

- An outline of the paper's structure and main arguments, to help the readers navigate through the paper with ease.

Preparing to Write Your Introduction

Before diving into writing your introduction, it is essential to prepare adequately. This involves 3 important steps:

- Conducting Preliminary Research: Immerse yourself in the existing literature to develop a clear research question and position your study within the academic discourse.

- Identifying Your Thesis Statement: Define a specific, focused, and debatable thesis statement, serving as a roadmap for your paper.

- Considering Broader Context: Reflect on the significance of your research within your field, understanding its potential impact and contribution.

By engaging in these preparatory steps, you can ensure that your introduction is well-informed, focused, and sets the stage for a compelling research paper.

Structuring Your Introduction

Now that you have prepared yourself to tackle the introduction, it's time to structure it effectively. A well-structured introduction will engage the reader from the beginning and provide a logical flow to your research paper.

Starting with a Hook

Begin your introduction with an attention-grabbing hook that captivates the reader's interest. This hook serves as a way to make your introduction more engaging and compelling. For example, if you are writing a research paper on the impact of climate change on biodiversity, you could start your introduction with a statistic about the number of species that have gone extinct due to climate change. This will immediately grab the reader's attention and make them realize the urgency and importance of the topic.

Introducing Your Topic

Provide a brief overview, which should give the reader a general understanding of the subject matter and its significance. Explain the importance of the topic and its relevance to the field. This will help the reader understand why your research is significant and why they should continue reading. Continuing with the example of climate change and biodiversity, you could explain how climate change is one of the greatest threats to global biodiversity, how it affects ecosystems, and the potential consequences for both wildlife and human populations. By providing this context, you are setting the stage for the rest of your research paper and helping the reader understand the importance of your study.

Presenting Your Thesis Statement

The thesis statement should directly address your research question and provide a preview of the main arguments or findings discussed in your paper. Make sure your thesis statement is clear, concise, and well-supported by the evidence you will present in your research paper. By presenting a strong and focused thesis statement, you are providing the reader with the information they could anticipate in your research paper. This will help them understand the purpose and scope of your study and will make them more inclined to continue reading.

Writing Techniques for an Effective Introduction

When crafting an introduction, it is crucial to pay attention to the finer details that can elevate your writing to the next level. By utilizing specific writing techniques, you can captivate your readers and draw them into your research journey.

Using Clear and Concise Language

One of the most important writing techniques to employ in your introduction is the use of clear and concise language. By choosing your words carefully, you can effectively convey your ideas to the reader. It is essential to avoid using jargon or complex terminology that may confuse or alienate your audience. Instead, focus on communicating your research in a straightforward manner to ensure that your introduction is accessible to both experts in your field and those who may be new to the topic. This approach allows you to engage a broader audience and make your research more inclusive.

Establishing the Relevance of Your Research

One way to establish the relevance of your research is by highlighting how it fills a gap in the existing literature. Explain how your study addresses a significant research question that has not been adequately explored. By doing this, you demonstrate that your research is not only unique but also contributes to the broader knowledge in your field. Furthermore, it is important to emphasize the potential impact of your research. Whether it is advancing scientific understanding, informing policy decisions, or improving practical applications, make it clear to the reader how your study can make a difference.

By employing these two writing techniques in your introduction, you can effectively engage your readers. Take your time to craft an introduction that is both informative and captivating, leaving your readers eager to delve deeper into your research.

Revising and Polishing Your Introduction

Once you have written your introduction, it is crucial to revise and polish it to ensure that it effectively sets the stage for your research paper.

Self-Editing Techniques

Review your introduction for clarity, coherence, and logical flow. Ensure each paragraph introduces a new idea or argument with smooth transitions.

Check for grammatical errors, spelling mistakes, and awkward sentence structures.

Ensure that your introduction aligns with the overall tone and style of your research paper.

Seeking Feedback for Improvement

Consider seeking feedback from peers, colleagues, or your instructor. They can provide valuable insights and suggestions for improving your introduction. Be open to constructive criticism and use it to refine your introduction and make it more compelling for the reader.