- Games & Quizzes

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction

Early waste disposal

Developments in waste management, composition and properties, generation and storage.

- Collecting and transporting

- Transfer stations

- Furnace operation

- Energy recovery

- Sorting and shredding

- Digesting and processing

- Constructing the landfill

- Controlling by-products

- Importance in waste management

- What role can living organisms play in environmental engineering?

solid-waste management

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- Engineering LibreTexts - Solid Waste Management

- Frontiers - Solid Waste Management in Indian Himalayan Region: Current Scenario, Resource Recovery, and Way Forward for Sustainable Development

- DigitalCommons at UMaine - Solid Waste Management (SWM) Options: The Economics of Variable Cost and Conventional Pricing Systems in Maine

- European Commission - Solid waste management

- The World Bank - Solid Waste Management

- Table Of Contents

solid-waste management , the collecting, treating, and disposing of solid material that is discarded because it has served its purpose or is no longer useful. Improper disposal of municipal solid waste can create unsanitary conditions, and these conditions in turn can lead to pollution of the environment and to outbreaks of vector-borne disease—that is, diseases spread by rodents and insects . The tasks of solid-waste management present complex technical challenges. They also pose a wide variety of administrative, economic, and social problems that must be managed and solved.

Historical background

In ancient cities, wastes were thrown onto unpaved streets and roadways, where they were left to accumulate. It was not until 320 bce in Athens that the first known law forbidding this practice was established. At that time a system for waste removal began to evolve in Greece and in the Greek-dominated cities of the eastern Mediterranean. In ancient Rome , property owners were responsible for cleaning the streets fronting their property. But organized waste collection was associated only with state-sponsored events such as parades. Disposal methods were very crude, involving open pits located just outside the city walls. As populations increased, efforts were made to transport waste farther out from the cities.

After the fall of Rome, waste collection and municipal sanitation began a decline that lasted throughout the Middle Ages . Near the end of the 14th century, scavengers were given the task of carting waste to dumps outside city walls. But this was not the case in smaller towns, where most people still threw waste into the streets. It was not until 1714 that every city in England was required to have an official scavenger. Toward the end of the 18th century in America, municipal collection of garbage was begun in Boston , New York City , and Philadelphia . Waste disposal methods were still very crude, however. Garbage collected in Philadelphia, for example, was simply dumped into the Delaware River downstream from the city.

A technological approach to solid-waste management began to develop in the latter part of the 19th century. Watertight garbage cans were first introduced in the United States, and sturdier vehicles were used to collect and transport wastes. A significant development in solid-waste treatment and disposal practices was marked by the construction of the first refuse incinerator in England in 1874. By the beginning of the 20th century, 15 percent of major American cities were incinerating solid waste. Even then, however, most of the largest cities were still using primitive disposal methods such as open dumping on land or in water.

Technological advances continued during the first half of the 20th century, including the development of garbage grinders, compaction trucks, and pneumatic collection systems. By mid-century, however, it had become evident that open dumping and improper incineration of solid waste were causing problems of pollution and jeopardizing public health . As a result, sanitary landfills were developed to replace the practice of open dumping and to reduce the reliance on waste incineration. In many countries waste was divided into two categories, hazardous and nonhazardous, and separate regulations were developed for their disposal. Landfills were designed and operated in a manner that minimized risks to public health and the environment. New refuse incinerators were designed to recover heat energy from the waste and were provided with extensive air pollution control devices to satisfy stringent standards of air quality. Modern solid-waste management plants in most developed countries now emphasize the practice of recycling and waste reduction at the source rather than incineration and land disposal.

Solid-waste characteristics

The sources of solid waste include residential, commercial, institutional, and industrial activities. Certain types of wastes that cause immediate danger to exposed individuals or environments are classified as hazardous; these are discussed in the article hazardous-waste management . All nonhazardous solid waste from a community that requires collection and transport to a processing or disposal site is called refuse or municipal solid waste (MSW). Refuse includes garbage and rubbish. Garbage is mostly decomposable food waste; rubbish is mostly dry material such as glass, paper, cloth, or wood. Garbage is highly putrescible or decomposable, whereas rubbish is not. Trash is rubbish that includes bulky items such as old refrigerators, couches, or large tree stumps. Trash requires special collection and handling.

Construction and demolition (C&D) waste (or debris) is a significant component of total solid waste quantities (about 20 percent in the United States), although it is not considered to be part of the MSW stream. However, because C&D waste is inert and nonhazardous, it is usually disposed of in municipal sanitary landfills.

Another type of solid waste, perhaps the fastest-growing component in many developed countries, is electronic waste , or e-waste, which includes discarded computer equipment, televisions , telephones , and a variety of other electronic devices. Concern over this type of waste is escalating. Lead , mercury , and cadmium are among the materials of concern in electronic devices, and governmental policies may be required to regulate their recycling and disposal.

Solid-waste characteristics vary considerably among communities and nations. American refuse is usually lighter, for example, than European or Japanese refuse. In the United States paper and paperboard products make up close to 40 percent of the total weight of MSW; food waste accounts for less than 10 percent. The rest is a mixture of yard trimmings, wood, glass, metal, plastic, leather, cloth, and other miscellaneous materials. In a loose or uncompacted state, MSW of this type weighs approximately 120 kg per cubic metre (200 pounds per cubic yard). These figures vary with geographic location, economic conditions, season of the year, and many other factors. Waste characteristics from each community must be studied carefully before any treatment or disposal facility is designed and built.

Rates of solid-waste generation vary widely. In the United States , for example, municipal refuse is generated at an average rate of approximately 2 kg (4.5 pounds) per person per day. Japan generates roughly half this amount, yet in Canada the rate is 2.7 kg (almost 6 pounds) per person per day. In some developing countries the average rate can be lower than 0.5 kg (1 pound) per person per day. These data include refuse from commercial, institutional, and industrial as well as residential sources. The actual rates of refuse generation must be carefully determined when a community plans a solid-waste management project.

Most communities require household refuse to be stored in durable, easily cleaned containers with tight-fitting covers in order to minimize rodent or insect infestation and offensive odours. Galvanized metal or plastic containers of about 115-litre (30-gallon) capacity are commonly used, although some communities employ larger containers that can be mechanically lifted and emptied into collection trucks. Plastic bags are frequently used as liners or as disposable containers for curbside collection. Where large quantities of refuse are generated—such as at shopping centres, hotels, or apartment buildings—dumpsters may be used for temporary storage until the waste is collected. Some office and commercial buildings use on-site compactors to reduce the waste volume.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 19 August 2023

Household practices and determinants of solid waste segregation in Addis Ababa city, Ethiopia

- Worku Adefris 1 ,

- Shimeles Damene ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9690-7111 1 &

- Poshendra Satyal 2

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 10 , Article number: 516 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

5858 Accesses

3 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Development studies

- Environmental studies

- Health humanities

Solid waste segregation plays a critical role in effective waste management; however, the practice remains at a low level in developing countries like Ethiopia. Despite the persistent nature of the problem, there are limited studies to date that can provide sufficient empirical evidence to support appropriate efforts by policy makers and practitioners, particularly in the context of the developing world. Therefore, the main objective of this study was to analyze household practices and determinants of solid waste segregation in the urban areas of Addis Ababa, the capital city of Ethiopia. To achieve this objective, data were generated through a household survey, focus group discussions, key informant interviews, and field observations. The collected quantitative data were cleaned, encoded, and statistically analyzed using descriptive statistics in SPSS, while thematic analysis was undertaken to evaluate and describe the qualitative data. The data analysis revealed that only 21.3% of respondents reported frequent solid waste segregation, while about half (45.5%) segregated solid waste rarely. Conversely, a considerable proportion (28.7%) of the respondents reported not segregating solid waste, and the remaining 4.5% of respondents were unsure about the practice. This implies that only one-fifth of the total sampled respondents actually implement solid waste segregation practices at the household level. The chi-square test showed that respondents’ awareness/training ( P = 0.000) and use of social organizations to discuss waste management ( P = 0.001) are significantly associated with the practice of solid waste segregation. This highlights the need to focus on awareness-raising efforts among the general public in order to improve the knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors of individual households and residents toward solid waste segregation practices. Additionally, enabling policies, sufficient infrastructure, and incentive mechanisms can also help enhance wider adoption of the practices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Realising a global One Health disease surveillance approach: insights from wastewater and beyond

Climate change to exacerbate the burden of water collection on women’s welfare globally

Removal of heavy metal ions from wastewater: a comprehensive and critical review

Introduction.

Solid waste management is a critical issue in various countries around the world (Nyampundu et al., 2020 ). Factors such as rising population density, urbanization, economic growth, and industrialization often contribute to an increasing volume of solid waste generated (Xiao et al., 2020 ). Globally, the average annual volume of solid waste generated by cities is estimated to be 1.9 billion tons (Kasozi and Von Blottnitz, 2010 ). In sub-Saharan cities, the volume reaches approximately 62 million tons per year (Hoornweg and Bhada-Tata, 2012 ). Effective solid waste management is crucial in minimizing health and environmental risks associated with waste in urban areas, particularly in the developing world (Hoornweg and Bhada-Tata, 2012 ; Amuda et al., 2014 ; Xiao et al., 2020 ). However, local authorities, especially in the urban settings of sub-Saharan Africa, face significant challenges in implementing effective and well-organized solid waste management (Firdaus and Ahmad, 2010 ). Rapid urbanization leading to increasing consumption and waste generation (both in terms of quantity and diversity) can deplete resources, cause environmental problems, and have significant social and economic impacts (Rousta and Ekström, 2013 ).

Developed countries have recognized the importance of waste segregation and recycling in improving solid waste management, leading them to implement various approaches such as the 3Rs (Reduce, Reuse, and Recycle) policies, legislations, and strategies (Falk and McKeever, 2004 ; Kang and Schoenung, 2005 ; Kumar et al., 2017 ). However, developing countries, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, have made limited progress and effort in this regard. A study by Kihila et al. ( 2021 ) highlighted the weak legal reinforcement of waste segregation practices in Tanzania at all stages, including household, collection, and disposal. This is primarily due to a lack of attention, inefficient coordination among various actors, financial constraints, capacity deficiencies, poor infrastructure, and governance issues.

Ethiopia, like many other developing countries in sub-Saharan Africa, has experienced rapid urbanization in recent years. This has resulted in overcrowding and the emergence of informal settlements with poor waste management practices, leading to public health and environmental problems (Nebiyou, 2020 ). Among developing cities, Addis Ababa has faced significant challenges related to poorly managed solid waste operations. The city’s waste generation has increased, but effective solid waste collection and management practices have been lacking (Gelan, 2021 ). These problems are influenced by various factors, including institutional, social, and contextual aspects of waste segregation (Zemena, 2016 ). Despite the persisting issues of solid waste collection and management, particularly regarding the practice of solid waste segregation, there is a limited empirical research in this area for Addis Ababa. This study aims to fill this research gap by assessing the determinants of solid waste segregation practices in Addis Ababa city. In so doing, the study seeks to provide an evidence-based understanding of the issue, support waste management implementation activities, facilitate policy-making, and contribute additional knowledge on the subject. The findings from this study may also offer valuable insights for other developing cities facing similar challenges.

Literature review

Theoretical background.

The evolving concept of waste management is centered around the principles of waste reduction, reuse, and recycling, with the aim of preventing harm to human health and the environment (Pongrácz et al., 2004 ). In addition, effective waste management plays a crucial role in achieving a circular economy, which has become a priority in many developed regions, especially in Europe. The circular economy aims to conserve resources and promote their circularity, leading to a more sustainable and economically viable future.

There is no single universal theory of waste management that can be directly applied as a practical tool for controlling waste-related activities (Pongrácz et al., 2004 ; Pongrácz, 2002 ). According to Pongrácz et al. ( 2004 ), a comprehensive waste management theory should involve a conceptual description of waste management that provides clear definitions of all waste-related concepts. Therefore, the achievement of sustainable waste management relies heavily on defining it properly and proposing an appropriate methodology that organizes the various variables of waste management systems. Pongrácz et al. ( 2004 ) emphasized four fundamental notions that should form the basis of waste management theory: (i) prevention of waste causing harm to human health and the environment; (ii) conservation of resources; (iii) reduction of waste creation by producing useful objects; and (iv) transformation of waste into non-waste materials.

In the context of waste management practices at the city or municipal level, it is important to apply and contextualize these core notions. Municipal solid waste management encompasses a range of tasks and activities, including waste generation control, storage, collection, transfer and transport, processing, and disposal (Rada et al., 2013 ). The overarching objective of these activities is to minimize the negative impacts of waste on human health and the environment, while simultaneously promoting economic development and improving quality of life (USEPA, 2020 ). Effective municipal solid waste management plays a crucial role in achieving efficient resource utilization, enhancing environmental quality and human health, and delivering socioeconomic benefits to local residents.

Solid waste management practices

The total urban waste generation is approximately 2 billion tons per year globally, with a projected per-capita increase of around 20% by the year 2100 (World Bank, 2018 ). As a result, municipal solid waste is considered a significant issue worldwide, as reflected in its inclusion within the Sustainable Development Goals, particularly Goals 11 (sustainable cities and communities) and 12 (responsible consumption and production). Effective waste management also plays a role in reducing global greenhouse gas emissions by 10–20% (Wilson, 2015 ; Hondo et al., 2020 ) and protecting the environment (Izvercian and Ivascu, 2015 ).

The generation rate and composition of solid waste vary across countries and regions due to socio-economic and cultural factors that influence consumption and production patterns. Therefore, it is crucial to understand the waste generation patterns within national and local contexts, taking into account socio-economic factors. This understanding helps inform waste management planning and actions (Ngoc and Schnitzer, 2009 ). Accurate data on solid waste generation and waste management practices are also essential for estimating the necessary human resources, equipment, and materials. Such data helps determine the size and location of waste collection and segregation facilities, design waste disposal systems, and develop overall waste management policies and plans (Ezeah and Roberts, 2012 ).

Solid waste production, particularly in developing countries, is experiencing a significant increase that exceeds the capacities of cities and municipalities in terms of removal and recycling. In these countries, the waste collection rates are 70% lower than the generation rates, and over 50% of the collected waste is disposed of in uncontrolled landfills or open dumpsites, often without adequate recycling measures (UNDESA, 2012 ). Ethiopia serves as an example of the consequences of inadequate solid waste management, with approximately 20–30% of the waste generated in its capital city, Addis Ababa, remaining uncollected (Tilaye and Dijk 2014 ).

Waste segregation practices

In the developed world, solid waste management methods have undergone progressive changes over the years. For instance, in Japan, separate waste collection was introduced in the 1970s and gradually became a common practice among citizens (Africa Data Book, 2019 ). However, in developing countries, waste segregation is not widely practiced (Hoornweg and Bhada-Tata, 2012 ). Source segregation of waste ensures that it is less contaminated and can be collected and transported for further processing. It also optimizes waste processing and treatment technologies, resulting in a higher quantity of segregated materials that can be recycled and reused, thus reducing the need for virgin materials (Ministry of Indian Urban Development, 2016 ). Similarly, waste segregation during or before collection improves efficiency and reduces costs by minimizing the labor and infrastructure required for segregating mixed wastes. However, in many developing countries, regular solid waste segregation is not practiced by users at the source, making the collection of segregated waste challenging in urban areas (Saja et al., 2021 ). This may be attributed to factors such as a lack of public awareness, limited investment in recycling facilities, and slow adoption of solid waste segregation practices (Abdel-Shafy and Mansour, 2018 ).

According to Kihila et al. ( 2021 ), there is still inadequate implementation of recycling practices in sub-Saharan Africa, primarily due to slow and limited behavioral change, as well as insufficient technologies for reuse, recycling, and recovery. In Ethiopia, the amount of generated waste varies (ranging between 0.25 and 0.49 kilogram per capita per day) by source in urban areas, including households, health institutions, commercial centers, industries, hotels, and street sweepings. Among these sources, households account for 70% of the total volume of solid waste generated in Addis Ababa municipality, with the remaining contributions coming from commercial centers (9%), industries (6%), hotels (3%), health institutions (1%), street sweepings (10%), and other sources (1%). The physical composition of the waste is estimated to include fruit and vegetables (4.2%), paper (2.5%), rubber/plastics (2.9%), woody materials (2.3%), bone (1.1%), textiles (2.4%), metals (0.9%), glass (0.5%), combustibles leaves (15.1%), non-combustible stones (2.5%), and 65.6% different fine materials such as sand, ash, and dust (Gelan, 2021 ). Moreover, solid waste management strategies such as prevention (reduction), reuse, and recycling, along with appropriate solid waste collection, segregation, transportation, and disposal, have been rarely adopted in Ethiopian cities. Source separation of solid waste can promote reuse and recycling practices and encourage informal private sector involvement in these activities (Hirpe and Yeom, 2021 ).

Ethiopia has established a legal framework (Negarit Gazeta Proclamation No. 513/ 2007 ) for solid waste management. Article 11:1 of the proclamation mandates households to segregate non-decomposable solid waste at the source for proper disposal at designated collection sites. However, despite these legal provisions, solid waste segregation has not been widely adopted (Abebe, 2017 ). Therefore, it is crucial to understand the factors influencing and the barriers to the practice of solid waste segregation. This study aimed to address the knowledge gap regarding this issue by analyzing the determinants of solid waste segregation in Addis Ababa city. The findings of the study can offer empirical insights and evidence-based recommendations for practitioners, policy makers, and the research community in improving solid waste management practices.

Methodology

Description of the study area.

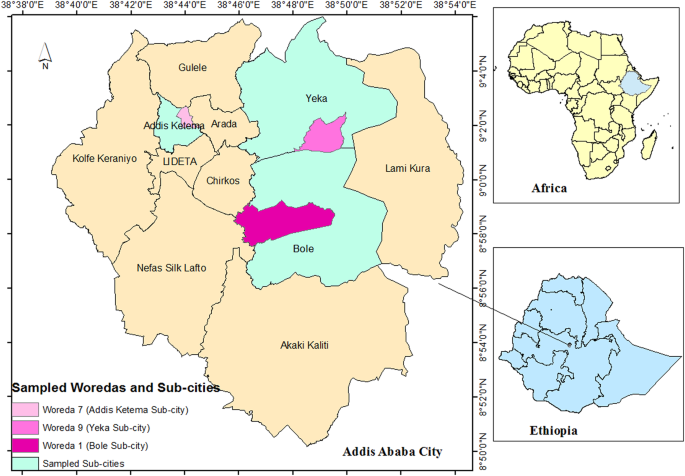

Addis Ababa, the political capital of Ethiopia and its primary commercial and cultural center, is situated geographically between 8°50’ and 9°06’N latitude and 38°39’ to 38°55’E longitude (Fig. 1 ). The city is located at an average altitude of 2400 meters above sea level (a.s.l.), with the highest elevations reaching approximately 3200 meters a.s.l. at mount Entoto in the north. As a result, Addis Ababa is classified as a high-altitude global city. The city spans a total land area of 540 square kilometers and is surrounded by hilly and mountainous terrain to the north and west. Drainage in Addis Ababa is facilitated by small rivers known as Akaki, including small and big Akaki, which originate from different locations and converge near the city’s outskirts. These rivers, namely small and big Akaki, have influenced the city’s landform (Abnet et al., 2017 ) and are vulnerable to pollution from solid and liquid waste.

Map of the study districts showing the location of sample woredas (Pinkish) and sub-cities (Indicolite Green) of Addis Ababa City (Topaz Sand) the capital of Ethiopia (Sodalite Blue) in Africa (Yucca Yellow) (Source of the data/(shape file: Ethiopian Central Statistical Authority, 2007). Source: Developed by the researcher using Ethio-GIS database (2007).

In recent years, waste generation in Addis Ababa has experienced a significant increase, with no signs of reduction, while waste management practices have remained largely traditional. The city has an estimated daily per capita solid waste generation capacity of approximately 0.45 kg (Gelan, 2021 ). Considering the city’s geographical area and population, the average waste generation is estimated to be around 330 kg/m 3 , resulting in a daily solid waste generation of approximately 6019 m 3 . Currently, the municipal solid waste produced in the city is directed to an uncontrolled landfill site called Koshe ( Reppi ). This landfill site has been associated with serious health and environmental risks, including foul odor and the discharge of contaminated leachates into surrounding areas and communities.

The population of Addis Ababa engages in various economic activities, with different sectors contributing to the city’s livelihoods. The major occupations include trade and commerce, which accounts for 22.6% of the population, followed by manufacturing (21.6%), the construction industry (15.3%), public service (13.5%), transport and communication (9.6%), social services—including health, education and other (8.1%), hotel and similar services (6.2%), and 3.1% urban agriculture (3.1%) (Abebe, 2017 ). The city has a considerable capacity of delivering economies of scale due to its concentrated demand, specialization, diversity, innovation, and technology transfer, enabling a broader range of operations (Hoornweg and Bhada-Tata, 2012 ). However, as consumption and production patterns continue to rise, Addis Ababa faces a significant challenge of generating a high volume of solid waste (Gelan, 2021 ). Despite this, solid waste management, particularly waste segregation practices, lags behind considerably in the city.

Sampling and data collection

In this study, Addis Ababa city was divided into three clusters based on economic activities, and waste generation capacity. The clusters were determined based on dominant activities such as business, residence, office, and other services one sub-city was purposefully selected from each cluster in consultation with the city’s solid waste management office. Out of the 11 sub-cities, the selected sub-cities were Addis Ketema (representing low waste generation capacity), Yeka (representing medium waste generation capacity), and Bole (representing high waste generation capacity). Subsequently, one woreda (district) was randomly chosen from each selected sub-city using a lottery method. The selected woredas were woreda 07, woreda 09, and woreda 01, representing Addis Ketema, Yeka, and Bole sub-cities, respectively. Based on the city administration data for the year 2022, the total number of households in the sampled woredas were as follows: 3576 in woreda 07; 4573 in woreda 09; and 3523 households in woreda 01.

The study utilized a descriptive research approach to examine the pattern of solid waste segregation practices in Addis Ababa. Both primary and secondary data were collected to achieve the research objectives. The primary data was collected from households through a questionnaire survey, focus group discussions, key informant interviews, and field observations. The survey questions had varying properties, with some being dichotomous (requiring a single response) and others allowing for multiple responses. As a result, certain variables in the analysis do not add up to the total sample size (i.e. n = 245).

Focus group discussions were conducted in each woreda , involving groups of 8–12 participants. The participants mainly consisted of members of waste collection enterprises who were engaged in door-to-door waste collection and segregation at the source (temporary collection site). It is important to note that the segregation at the source primarily focused on separating non-decomposable materials such as plastic bags, bottles, metal scraps, and glass from decomposable materials.

Fifteen interviews were conducted with woreda leaders of waste collectors, officials from the Addis Ababa City Solid Waste Management Agency, and staff from the solid waste cleansing office in the sampled woredas . Before the actual household survey and data collection, a pilot test was conducted to ensure the effectiveness of the questionnaire. Field observations were also conducted, with a specific focus on door-to-door waste collection, segregation, and management practices. These observations were guided by a checklist and documented in a research diary, which served as an important resource for data interpretation and analysis.

In the study, the sample size was determined by Cochran’s formula (Cochran, 1977 ): ( \({{{n}}} = {\textstyle{{{{{Z}}}^2{{{pq}}}} \over {{{{e}}}^2}}}\) ). In this formula, n represents the sample size, z is the selected critical value corresponding to the desired confidence level, p is the estimated proportion of an attribute in the population, q = 1− p , and e is the desired level of precision, with a 95% confidence level and a maximum variability in a population of 0.5. Accordingly, the survey questionnaire was administered to 245 respondents by a trained enumerator in May 2022 from the three sampled woredas with a total household population of 11,762.

Using the Cochran ( 1977 ) formula with a 95% confidence level and a precision of 0.05, and assuming a variability of 20% due to time constraints, the sample size was calculated as follows:

Therefore, the sample size was determined to be 245.

The sampled proportion was then distributed in each woreda (Table 1 ) based on the number of households, using the formula: \(nh = \left( {{\textstyle{{Nh} \over N}}} \right){{{n}}}\) where Nh represents the population on each woreda , N is the total household population, nh is the total sampled population.

It is worth noting that one questionnaire had missing values, resulting in a total of 244 questionnaires being used for the analysis. The survey questionnaire also included a section on the socio-demographic profile of the households. In this study, a chi-square model was employed to test the relationship between categorical data.

Results and discussion

Solid waste segregation practices.

Table 2 presents the findings of the solid waste segregation practices based on the analysis of data from 244 respondents. The analysis revealed that the majority of survey households (63.5%) recognized the importance of solid waste segregation practices. This indicates that the community has a significant understanding of solid waste segregation, which can encourage the actual implementation of segregation practices.

According to the input from focus group discussions and key informant interviews, mass media, health extension services, and waste collectors have played a major role in disseminating information (although it has been limited thus far) on the importance of solid waste segregation. A study conducted by Otitoju and Seng ( 2014 ) in Malaysia also indicated that a large proportion (86.3%) of respondents had heard about waste segregation through mass media or community discussions. However, the authors emphasized that simply providing information does not guarantee people’s active involvement in implementing waste segregation practices. Similarly, Abdel-Shafy and Mansour ( 2018 ) reported that the success of any solid waste segregation practice heavily relies on the level of public awareness and active participation of different communities. It is essential for the community to undergo a radical attitudinal change that allows the acquired knowledge to be translated into practical implementation.

The study also examined the willingness of respondents to engage in solid waste segregation practices, revealing that the majority (84%) expressed their willingness to implement the practice. This indicates a significant potential to translate this willingness into action through further efforts in public awareness campaigns, capacity-building initiatives, and policy support.

A similar study conducted in Suzhou, China demonstrated that residents’ positive attitudes and willingness to engage in solid waste separation played a crucial role in the rapid adoption of the practice (Zhang and Wen, 2014 ). This suggests that by leveraging the positive attitudes and willingness of individuals, combined with educational initiatives, the implementation of solid waste segregation practices can be accelerated.

The study found that slightly more than half of the respondents (54.1%) reported a lack of sufficient space to segregate waste in their residence areas. Focus group discussants further highlighted the challenges faced by waste collectors in segregating waste in congested living conditions. This indicates that the absence of adequate space to segregate collected waste in situ in residential areas is a barrier to achieving the required level of segregation for different communities.

This finding aligns with a study conducted by the United States Environmental Protection Agency ( 2020 ), which emphasized that a well-designed storage system will not be effective if the locations or containers for waste segregation are inconvenient for residents or waste collectors. Therefore, addressing the issue of limited space and ensuring convenient and accessible segregation points are crucial factors for promoting effective waste segregation practices.

The study found that 54.5% of the respondents do not prepare different containers for solid waste segregation, while 45.9% of respondents reported not having the necessary materials for segregating waste or keeping different kinds of waste separately. This indicates that overall, the practice of solid waste segregation at the source (household) is poor in the community.

A study conducted by Tassie et al. ( 2019 ) supports these findings, highlighting the importance of good awareness and appropriate facilities for the proper implementation of segregation practices. When the community has sufficient awareness and motivation, individual households can use materials available at home such as baskets, cardboard boxes, bamboo containers, cans, plastic bags, barrels, etc., to prepare temporary storage containers for waste segregation. Similarly, Otitoju and Seng ( 2014 ) found that providing more facilities such as bins and containers in housing areas, in addition to creating awareness, can enhance community participation in waste segregation.

Among the survey households, 45.5% reported segregating waste sometimes, while 21.3% reported segregating waste regularly. On the other hand, 28.7% of respondents did not segregate waste before disposing of it from their homes or compounds, and 4.5% were unsure about the practice. This indicates that only one-fifth of sampled respondents correctly implement solid waste segregation at the household level, while the majority (79%) either practice segregation rarely or not at all. For those households not practicing segregation or uncertain about it, targeted interventions such as education, public awareness campaigns, enabling policies, sufficient infrastructure, and incentive mechanisms need to be implemented by the relevant authorities to promote the adoption and scaling up of segregation practices. A study by Yoada et al. ( 2014 ) in Accra, Ghana, reported that only 17.3% of respondents indicated that the households sort waste by category at home before delivering it to collectors, which reflects the broader trend observed in many African cities.

Table 2 provides insights into the reasons for the non-segregation of waste at the household or outdoor level. According to the table, 50.4% of the respondents thought that they generate a very small amount of waste, leading them to consider waste separation as pointless. Additionally, 25.6% of respondents reported a lack of facilities for waste segregation, 10.5% mentioned the inability to afford dust bins due to cost, and another 10.5% were not aware of the practice of segregation.

During the focus group discussions, participants expressed the view that segregation could be more feasible if they generated larger volumes of solid waste. Some participants expressed the need for external support to provide facilities such as dust bins, while others showed a lack of concern and awareness about the importance of solid waste segregation. These findings suggest a lack of awareness and limited motivation among the community to engage in segregation practices. In line with these findings, Kihila et al. ( 2021 ) also reported that people often disregard segregating waste at the source due to poor awareness, lack of facilities and equipment like containers, or the low volumes of recyclable materials generated.

The study found that in terms of separating waste at temporary solid waste disposal places, 36.9% of the respondents do not separate the waste at all, and 12.3% are unsure about whether they separate solid waste. On the other hand, 29.9% of the respondents always separate waste, and 20.9% sometimes separate waste. These findings suggest that, in general, the community has a low inclination toward practicing solid waste segregation outside their homes. There seems to be a common attitude of “I don’t care after I’ve used it”.

These findings align with the study conducted by Otitoju and Seng ( 2014 ), which revealed that communities do not have a promising attitude towards solid waste segregation as long as the waste is collected. The research conducted in Accra by Yoada et al. ( 2014 ) also highlighted that citizens do not take responsibility for proper waste disposal, including segregation, as they rely on the government to remove household-generated waste. This can be attributed, in part, to a poor attitude and lack of concern about the environment and public health.

These attitudes and behaviors reflect a need for increased awareness, education, and a shift in mindset toward the importance of proper waste segregation and disposal. Efforts to promote community engagement, responsible waste management practices, and environmental consciousness can help address these challenges and encourage greater participation in waste segregation.

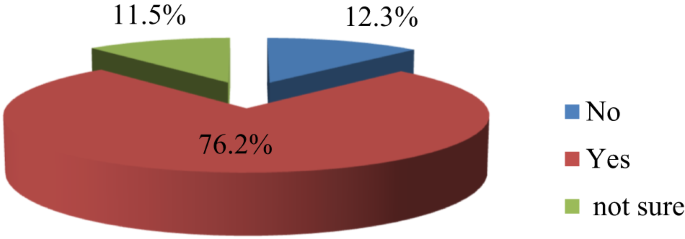

According to Fig. 2 , the majority (76.2%) of respondents associate the 3Rs (Reuse, Recycling, and Recovery) primarily with the segregation of waste. A portion of respondents (12.3%) reported not knowing about the 3Rs, and 11.5% were unsure. Overall, the majority of participants demonstrated a good understanding of the 3Rs, particularly in relation to solid waste segregation. They recognized the economic value of waste and provided examples such as using animal dung or other decomposable waste for composting and selling plastic bottles to generate income.

Source: Questionnaire survey (2022).

Kihila et al. ( 2021 ) reported that waste segregation is a crucial element in the waste management chain for effective implementation of the 3Rs. Segregation at the source simplifies handling and processing, thereby facilitating resource recovery, promoting reuse and recycling, and reducing operational costs. Similarly, Otitoju and Seng ( 2014 ) suggested that discarded products and waste materials possess economic value when they are reused or reintroduced into the technological cycle. Therefore, source segregation is fundamental for successful and economically viable recycling activities.

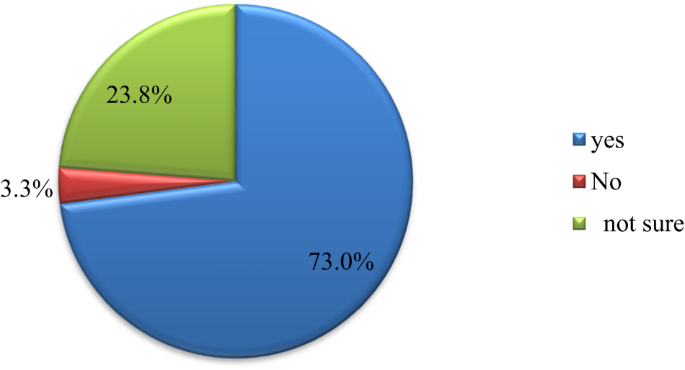

According to Fig. 3 , when asked about the importance of solid waste segregation at the source for waste reduction, over 73% of the respondents believed that the practice is effective in reducing waste. Only 3.2% perceived that it does not contribute to waste reduction, and the remaining respondents were unsure. This indicates that a significant number of community members understand that segregating waste at the source can lead to a reduction in the volume of generated solid waste at various levels.

Source: Questionnaire survey, 2022.

This finding is consistent with the study conducted by Otitoju and Seng ( 2014 ), which emphasizes that practicing segregation at the source can significantly reduce the amount of solid waste that ends up in landfills. Similarly, the study by Kihila et al. ( 2021 ) suggests that waste segregation at the source can lead to a significant reduction in waste volumes, ultimately improving the efficiency of collection and disposal processes. These findings highlight the importance of promoting and implementing solid waste segregation practices as an effective means of waste reduction, contributing to more efficient waste management systems.

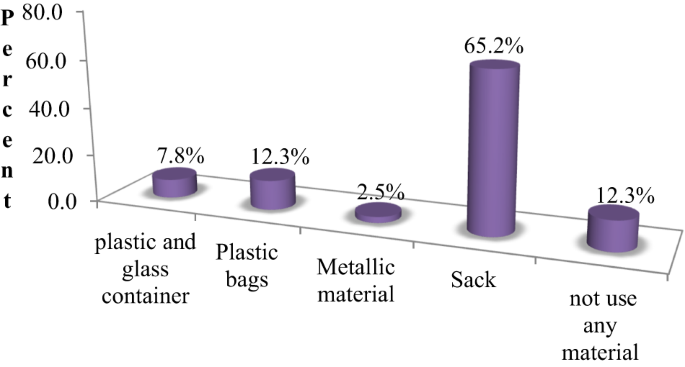

Figure 4 illustrates the type of materials used for waste collection among the survey respondents. The majority (65.2%) reported using sacks, 12.3% use plastic bags, 7.7% use both plastic and glass containers, 2.5% use metallic materials, and 12.3% do not use any fixed type of material. The predominant use of sacks for sorting solid waste indicates a potential for reusing or recycling them. However, it is important to note that the use of sacks can lead to the escape of leachate materials, which poses a risk of environmental pollution (e.g., water or soil contamination) and may require frequent replacement (Abebe, 2017 ).

Overall, the key informant interviewees and focus group discussants confirmed the low level of understanding and awareness among households regarding solid waste segregation in Addis Ababa, despite some recent improvements. They attributed the limited progress to sporadic door-to-door awareness activities conducted by the health extension workers and informal communication from the waste collectors. However, in most residential areas of the city, proper practices of solid waste segregation have been lagging at all levels.

Determinants of solid waste segregation practices

In the study, Chi-square and t -test analyses were conducted to examine the relationship between various variables and the willingness of solid waste segregation. The p -value was used to assess the statistical significance of the observed results. A p -value of <0.005 indicates a higher level of statistical significance, suggesting a significant correlation between the variables.

The variables of gender, educational level, monthly income, willingness, awareness/training, and use of social organizations were specifically analyzed to determine their potential association with solid waste segregation practices. The results of these analyses can provide insights into the factors that influence the willingness of individuals to engage in solid waste segregation.

Gender and solid waste segregation practice

According to the results presented in Table 3 , the calculated value of Chi-square is 1.565 with a p -value of 0.211. This indicates that there is no significant association between the gender of the respondents and their practice of solid waste segregation at the gate/door.

Traditionally, domestic chores and household management, including activities related to house cleaning, have been culturally associated with women’s roles in many developing countries (Banga, 2011 ). However, our analysis did not find a significant difference between male and female respondents in terms of segregating solid waste before disposal. It is worth noting that female members generally have knowledge and decision-making authority regarding what is considered useful and non-waste, although male members also cooperate in waste management practices.

Educational level of the respondents

According to Table 3 , the p -value obtained for the association between educational level and solid waste segregation practice at the gate/door is 0.446, indicating an insignificant difference. The analysis suggests that the educational level of the respondents is not significantly associated with their practice of solid waste segregation.

This finding is consistent with previous studies conducted by Abebe ( 2017 ) and Otitoju and Seng ( 2014 ), which also reported a lack of significant relationship between the educational level of households and their participation in solid waste segregation at the source. It implies that people’s attitude towards waste segregation, rather than their education or knowledge, plays a more significant role in determining their household-level waste segregation practices.

Monthly income of the respondents

As indicated in Table 3 , the calculated t -test value for the association between monthly income (with a mean monthly income of 5141.4 Birr and 4618.4 Birr std. deviation) and solid waste segregation practice at the gate is −0.185, assuming equal variances, with a p -value of 0.220. This suggests that there is an insignificant association between the monthly income of respondents and their practice of solid waste segregation practice at the gate.

The focus group discussions also supported this finding, as they did not observe any substantial difference in waste segregation practices among households with different income levels. This implies that income level does not play a significant role in determining the extent to which households segregate their solid waste at the source. Other factors, such as awareness, motivation, and access to facilities, may have a stronger influence on waste segregation practices than income alone.

Awareness and training

As presented in Table 3 , the Chi-square test value for the association between respondents’ awareness/training and practice of solid waste segregation at the gate is 50.920, with a p -value of 0.000. This indicates a highly significant ( p < 001) association between respondent’s awareness or training and their practice of solid waste segregation at the gate.

The analysis demonstrates that an increase in public awareness and the provision of relevant training can have a significant impact on promoting and encouraging solid waste segregation practices at the household or gate/door level. When individuals are aware of the importance of waste segregation and have received appropriate training on how to implement it effectively, they are more likely to actively engage in segregating their waste at the source.

These findings emphasize the importance of targeted awareness campaigns and training programs to improve waste management practices, particularly in promoting solid waste segregation. By increasing the knowledge and understanding of the community, it becomes more feasible to enhance the adoption and implementation of waste segregation practices, leading to more effective waste management and environmental sustainability.

Role of social organizations (e.g. Idir , Ikub )

As indicated in Table 3 , the Chi-square test value for the relationship between the use of social organizations (such as Idir and Iqub ) and the practice of solid waste segregation at the gate is 10.878, with a p -value of 0.001. This suggests a significant association between the use of social organizations and the practice of solid waste segregation.

The findings highlight that individuals who actively participate in social organizations, such as Idir and Iqub , are more likely to engage in solid waste segregation practices at the household or gate/door level. While Idir is aimed at helping each other, especially in funerals or burials, Iqub is a traditional mutual saving and credit association. These social organizations can serve as platforms for disseminating information, promoting awareness, and encouraging community members to adopt sustainable waste management practices. The collective nature of these associations can foster a sense of social responsibility and cooperation, leading to increased participation in waste segregation activities.

Other studies have also shown that active participation in social groups or associations can positively influence individuals’ attitudes and behaviors, including waste management practices. The sense of belonging, shared values, and mutual support within these organizations can contribute to the adoption of group decisions and actions, such as the implementation of waste segregation practices (Begashaw, 1978 ; Aredo, 1993 ).

Therefore, leveraging the existing social organizations in the community and engaging them in waste management initiatives can be an effective strategy to promote and enhance solid waste segregation practices at the household level. By working together through these organizations, communities can create a collective impact and contribute to the improvement of waste management and environmental sustainability.

This study focused on exploring household practices and determinants of solid waste segregation in Addis Ababa city. The findings reveal that solid waste segregation practices at the household level are very low in the city, with significant variations in awareness, understanding, and willingness among the community to adequately implement these practices effectively. Only one-fifth of sampled respondents reported implementing solid waste segregation, while the majority (79%) of the respondents either rarely practiced the segregation or did not at all. Analysis of both qualitative and quantitative data from this study indicates that awareness and attitude regarding solid waste segregation in Addis Ababa city are still poor, despite some recent progress. Consequently, the actual implementation of solid waste segregation practices is generally weak. The analysis demonstrates that household awareness/training and the use of social organizations have a positive and significant impact on solid waste segregation practices. However, other household factors such as gender, income, and education level do not seem to influence households’ willingness to segregate solid waste at home or at the gate. Based on these findings, efforts should be focused on raising broad public awareness and providing training to improve the knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors of individual households and residents regarding solid waste segregation practices. This should be complemented by necessary policy interventions, such as additional regulatory measures, and support for recycling facilities. Therefore, targeted interventions, including intensive awareness campaigns, the facilitation of relevant infrastructure, and other incentive mechanisms, should be considered by the government and local authorities to promote the adoption and scaling up of waste segregation practices. Although this study had limitations in fully understanding the barriers and opportunities in waste management practices, it provides useful insights for other rapidly urbanizing cities in the developing world. A more detailed study focusing on people’s knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors could further explore the underlying causes of poor waste segregation practices.

Data availability

Data will be shared on reasonable request.

Abdel-Shafy HI, Mansour MS (2018) Solid waste issue: Sources, composition, disposal, recycling, and valorization. Egypt J Pet 27(4):1275–1290

Article Google Scholar

Abebe MA (2017) Segregation of solid waste at household level in Addis Ababa City. Int J Sci Eng Sci 1(4):1–10

Google Scholar

Abnet G, Dawit B, Imam M, Tsion L, Yonas A (2017) City profile. Addis Ababa. Social Inclusion and Energy Management for Informal Urban Settlements, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

Africa Data Book (2019) Africa solid waste management. Data Book

Amuda OS, Adebisi SA, Jimoda LA, Alade AO (2014) Challenges and possible panacea to the municipal solid wastes management in Nigeria. J Sustain Dev Stud 6(1):64–70

Aredo D (1993) The informal and semi-formal financial sectors in Ethiopia: a study of the iqub, iddir and savings and credit co-operatives. African Economic Research Consortium, Research paper 21, pp. 11–12

Banga M (2011) Household knowledge, attitudes and practices in solid waste segregation and recycling: the case of urban Kampala. Zambia. Soc Sci J 2(1):27–39

Begashaw G (1978) The economic role of traditional savings and credit institutions in Ethiopia. Sav Dev 2(4):249–264

Cochran WG (1977) Sampling techniques, 3rd edn. John Wiley and Sons, New York

Ezeah C, Roberts CL (2012) Analysis of barriers and success factors affecting the adoption of sustainable management of municipal solid waste in Nigeria. J Environ Manag 103:9–14

Falk RH, McKeever DB (2004) Recovering wood for reuse and recycling: a United States perspective. In: Gallis C (ed) European COST E31 conference: management of recovered wood recycling bioenergy and other options, proceedings, 22–24 April 2004, Thessaloniki. University Studio Press, Thessaloniki, pp. 29–40

Firdaus G, Ahmad A (2010) Management of urban solid waste pollution in developing countries. Int J Environ Res 4(4):795–806

Gelan E (2021) Municipal solid waste management practices for achieving green architecture concepts in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Technologies 9(48):1–17

Hirpe L, Yeom C (2021) Municipal solid waste management policies, practices, and challenges in ethiopia: a systematic review. Sustainability 13(20):11241

Hondo D, Arthur L, Gamaralalage PJD (2020) Solid waste management in developing Asia: prioritizing waste separation. ADB Institute, No. 2020-7. https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/652121/adbi-pb2020-7.pdf

Hoornweg D, Bhada-Tata P (2012) What a waste: a global review of solid waste management. Urban development series; knowledge papers no. 15. World Bank, Washington, DC

Izvercian M, Ivascu L (2015) Waste management in the context of sustainable development: case study in Romania. Procedia Econ Finance 26:717–721

Kang HY, Schoenung JM (2005) Electronic waste recycling: a review of US infrastructure and technology options. Resour Conserv Recycl 45(4):368–400

Kasozi A, Von Blottnitz H (2010) Solid waste Management in Nairobi: a situation analysis. Report for City Council of Nairobi, contract for UNEP

Kihila JM, Wernsted K, Kaseva M (2021) Waste segregation and potential for recycling—a case study in Dar es Salaam City, Tanzania. Sustain Environ 7(1):1935532

Kumar A, Holuszko M, Espinosa DCR (2017) E-waste: an overview on generation, collection, legislation and recycling practices. Resour Conserv Recycl 122:32–42

Ministry of Indian Urban Development (2016) Municipal solid waste management manual. Central Public Health and Environmental Engineering Organization (CPHEEO)

Nebiyou M (2020) Decentralization and municipal service delivery: the case of solid waste management in Debre Markos Town, Amhara National Regional State. MA thesis submitted to Addis Ababa University, Ethiopia

Negarit Gazeta of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Proclamation No. (513/12007). Solid Waste Management Proclamation, p. 3524. 13th Year No. 13, Addis Ababa,12 February 2007

Ngoc UN, Schnitzer H (2009) Sustainable solutions for solid waste management in Southeast Asian countries. Waste Manag 29(6):1982–1995

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Nyampundu K, Mwegoha WJ, Millanzi WC (2020) Sustainable solid waste management measures in Tanzania: an exploratory descriptive case study among vendors at Majengo market in Dodoma City. BMC Public Health 20(1):1–16

Otitoju TA, Seng L (2014) Municipal solid waste management: household waste segregation in Kuching South City, Sarawak, Malaysia. Am J Eng Res 3(6):82–91

Pongrácz E (2002) Re-defining the concepts of waste and waste management evolving the theory of waste management. Acta Universitatis Ouluensis. Series C, Technica, p. 32

Pongrácz E, Phillips PS, Keiski RL (2004) Evolving the theory of waste management-implications to waste minimization. In: Pongrácz E (ed) Proceedings of the waste minimization and resources use. Optimization Conference. June 10, 2004, University of Oulu, Finland, Oulu, p.61-67

Rada EC, Ragazzi M, Fedrizzi P (2013) Web–GIS oriented systems viability for municipal solid waste selective collection optimization in developed and transient economies. Waste Manag 33:785–792

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Rousta K, Ekström KM (2013) Assessing incorrect household waste sorting in a medium-sized Swedish city. Sustainability 5(10):4349–4361

Saja AMA, Zimar AMZ, Junaideen SM (2021) Municipal solid waste management practices and challenges in the southeastern coastal cities of Sri Lanka. Sustainability 13(8):4556

Tassie K, Endalew B, Mulugeta A (2019) Composition, generation and management method of municipal solid waste in Addis Ababa city, central Ethiopia: a review. Asian J Environ Ecol 9(2):1–19

Tilaye M, Dijk MP (2014) Sustainable solid waste collection in Addis Ababa: the users’ perspective. Int J Waste Resour 4(3):1–11

UNDESA (2012) Shanghai manual: a guide for sustainable urban development in the 21st century. UNDESA

United States Environmental Protection Agency (2020) Best practices for solid waste management: a guide for decision-makers in developing countries. United States Environmental Protection Agency

USEPA (2020) Best practices for solid waste management: a guide for decision-makers in developing countries. https://www.iges.or.jp/en/pub/best-practices-solid-waste-management-guide-decision-makers-developing-countries/

World Bank (2018) What a waste 2.0: a global snapshot of solid waste management to 2050. The World Bank, Washington, DC

Wilson D (2015) Global waste management outlook: summary for decision-makers. https://repository.udca.edu.co/bitstream/handle/11158/3009/GWMO%20

Xiao S, Dong H, Geng Y, Francisco MJ, Pan H, Wu F (2020) An overview of the municipal solid waste management modes and innovations in Shanghai, China. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 27(16):29943–29953

Yoada RM, Chirawurah D, Adongo PB (2014) Domestic waste disposal practice and perceptions of private sector waste management in urban Accra. BMC Public Health 14(1):1–10

Zemena G (2016) Solid waste management practice and factors influencing its effectiveness: the case of selected private waste collecting companies in Addis Ababa. Doctoral dissertation, St. Mary’s University

Zhang H, Wen ZG (2014) Residents’ household solid waste (HSW) source separation activity: a case study of Suzhou, China. Sustainability 6(9):6446–6466

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors express their sincere gratitude to all the respondents who participated in the survey, focus group discussion, and key informant interviews. The valuable time and willingness of the participants to share their insights and information were essential for the success of this study. Their contributions have greatly contributed to the generation of meaningful data and the overall quality of the research. The authors appreciate their cooperation and willingness to engage in the research process.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Center for Environment and Development Studies, College of Development Studies, Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

Worku Adefris & Shimeles Damene

BirdLife International, Cambridge, UK

Poshendra Satyal

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

All authors of this manuscript made significant contributions throughout the research process and the writing of the manuscript. Each author played a crucial role in the conception or design of the study, the collection and analysis of data, and the interpretation of the findings. They actively participated in drafting and revising the manuscript, ensuring its intellectual content and overall quality. All authors have provided their final approval for the version to be published and have agreed to take responsibility for the accuracy and integrity of the work. They are committed to addressing any questions or concerns related to the research and resolving them appropriately.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Shimeles Damene .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests. They take full responsibility for any unethical acts such as presenting false statements or failure to adhere to standard expectations.

Ethical approval

The study proposal and the assessment tools underwent a thorough review and received approval from the Addis Ababa University (AAU)’s College of Development Studies (CoDS) Institutional Review Board (IRB).

Informed consent

The data collection process was conducted with strict adherence to ethical considerations. Informed consent was obtained for all respondents, and the research was carried out in accordance with ethical standards, following established social sciences approaches. Prior to the survey, data collectors were thoroughly briefed on the importance of ethical considerations during field research. Respondents were assured that their data would be treated confidentially and used solely for research purposes. They were also informed that all personal information, including their names, would be anonymized in the research outputs. Participants were assured that their participation was voluntary, and they had the right to ask questions or withdraw from the interview at any time.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Assessment tools, raw data used in segregation practice and challenge in addis ababa city, rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Adefris, W., Damene, S. & Satyal, P. Household practices and determinants of solid waste segregation in Addis Ababa city, Ethiopia. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10 , 516 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01982-7

Download citation

Received : 08 November 2022

Accepted : 25 July 2023

Published : 19 August 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01982-7

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Information

- Author Services

Initiatives

You are accessing a machine-readable page. In order to be human-readable, please install an RSS reader.

All articles published by MDPI are made immediately available worldwide under an open access license. No special permission is required to reuse all or part of the article published by MDPI, including figures and tables. For articles published under an open access Creative Common CC BY license, any part of the article may be reused without permission provided that the original article is clearly cited. For more information, please refer to https://www.mdpi.com/openaccess .

Feature papers represent the most advanced research with significant potential for high impact in the field. A Feature Paper should be a substantial original Article that involves several techniques or approaches, provides an outlook for future research directions and describes possible research applications.

Feature papers are submitted upon individual invitation or recommendation by the scientific editors and must receive positive feedback from the reviewers.

Editor’s Choice articles are based on recommendations by the scientific editors of MDPI journals from around the world. Editors select a small number of articles recently published in the journal that they believe will be particularly interesting to readers, or important in the respective research area. The aim is to provide a snapshot of some of the most exciting work published in the various research areas of the journal.

Original Submission Date Received: .

- Active Journals

- Find a Journal

- Proceedings Series

- For Authors

- For Reviewers

- For Editors

- For Librarians

- For Publishers

- For Societies

- For Conference Organizers

- Open Access Policy

- Institutional Open Access Program

- Special Issues Guidelines

- Editorial Process

- Research and Publication Ethics

- Article Processing Charges

- Testimonials

- Preprints.org

- SciProfiles

- Encyclopedia

Article Menu

- Subscribe SciFeed

- Recommended Articles

- PubMed/Medline

- Google Scholar

- on Google Scholar

- Table of Contents

Find support for a specific problem in the support section of our website.

Please let us know what you think of our products and services.

Visit our dedicated information section to learn more about MDPI.

JSmol Viewer

Testing the role of waste management and environmental quality on health indicators using structural equation modeling in pakistan.

1. Introduction

2. theoretical model, inter-relationships between constructs, 3. research methods, 3.1. data collection, 3.2. measurement model (mm), 5. discussion, 6. conclusions and policy implications, author contributions, institutional review board statement, informed consent statement, data availability statement, acknowledgments, conflicts of interest.

| 15–20 | 21–30 | 31–40 | 41–50 | >51 | |

| Female | 153 | 221 | 119 | 47 | 11 |

| Male | 92 | 94 | 109 | 3 | 1 |

| <30k | 31k–50k | 51k–70k | 51k–70k | 71k–100,000 | |

| Illiterate | 92 | 57 | 21 | 7 | 26 |

| Primary | 30 | 10 | 9 | 3 | 5 |

| Secondary | 70 | 41 | 38 | 13 | 46 |

| Higher | 29 | 38 | 46 | 19 | 56 |

| Professional | 27 | 32 | 28 | 24 | 73 |

| Health Status | Waste Disposal | Environmental Quality | Environmental Knowledge | Defensive Behavior | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health status | 1 | ||||

| Waste disposal | −0.111 ** (0.001) | 1 | |||

| Environmental quality | −0.114 ** (0.001) | −0.15 (0.666) | 1 | ||

| Environmental knowledge | 0.294 ** (0.00) | −0.61 (0.76) | −0.71 * (0.038) | 1 | |

| Defensive behavior | 0.69 * (0.044) | 0.0179 ** (0.00) | −0.283 ** (0.00) | 0.010 (0.769) | 1 |

- Yukalang, N.; Clarke, B.; Ross, K. Solid waste management solutions for a rapidly urbanizing area in Thailand: Recommendations based on stakeholder input. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018 , 15 , 1302. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ] [ Green Version ]

- Kumar, S.; Pandey, A. Current developments in biotechnology and bioengineering and waste treatment processes for energy generation: An introduction. In Current Developments in Biotechnology and Bioengineering ; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 1–9. [ Google Scholar ]

- Rai, R.K.; Bhattarai, D.; Neupane, S. Designing solid waste collection strategy in small municipalities of developing countries using choice experiment. J. Urban Manag. 2019 , 8 , 386–395. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Pek, C.-K.; Jamal, O. A choice experiment analysis for solid waste disposal option: A case study in Malaysia. J. Environ. Manag. 2011 , 92 , 2993–3001. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ] [ Green Version ]

- Thi NB, D.; Kumar, G.; Lin, C.-Y. An overview of food waste management in developing countries: Current status and future perspective. J. Environ. Manag. 2015 , 157 , 220–229. [ Google Scholar ]

- Marshall, R.E.; Farahbakhsh, K. Systems approaches to integrated solid waste management in developing countries. Waste Manag. 2013 , 33 , 988–1003. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Srivastava, V.; Ismail, S.A.; Singh, P.; Singh, R.P. Urban solid waste management in the developing world with emphasis on India: Challenges and opportunities. Rev. Environ. Sci. Bio/Technol. 2015 , 14 , 317–337. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Pervin, I.A.; Rahman, S.M.; Nepal, M.; Hague, A.E.; Karim, H.; Dhakal, G. Adapting to urban flooding: A case of two cities in South Asia. Water Policy 2020 , 22 (Suppl. 1), 162–188. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Yoada, R.M.; Chirawurah, D.; Adongo, P.B. Domestic waste disposal practice and perceptions of private sector waste management in urban Accra. BMC Public Health 2014 , 14 , 697. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Choon, S.W.; Tan, S.H.; Chong, L.L. The perception of households about solid waste management issues in Malaysia. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2017 , 19 , 1685–1700. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Wazir, M.A.; Goujon, A. Assessing the 2017 Census of Pakistan Using Demographic Analysis: A Sub-National Perspective. Available online: https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/207062/1/1667013416.pdf (accessed on 2 March 2021).

- Fatima, S.A. A Study of Evaluation of Solid Waste Management System and Assessment of Waste Generation in Samanabad Town, Lahore ; University of the Punjab: Lahore, Pakistan, 2010. [ Google Scholar ]

- Majeed, A.; Batool, S.A.; Chaudhry, M.N. Environmental Quantification of the Existing Waste Management System in a Developing World Municipality Using EaseTech: The Case of Bahawalpur, Pakistan. Sustainability 2018 , 10 , 2424. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Akmal, T.; Jamil, F. Assessing Health Damages from Improper Disposal of Solid Waste in Metropolitan Islamabad–Rawalpindi, Pakistan. Sustainability 2021 , 13 , 2717. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Rafiq, M.; Khan, M.; Gillani, H.S. Health and economics implication of solid waste dumpsite: A case study Hazar Khawani Peshawar. FWU J. Soc. Sci 2015 , 9 , 40–52. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ejaz, N.; Janjua, M.S. Solid Waste Management Issue in Small Towns of Developing World: A Case Study of Taxila City. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Dev. 2012 , 3 , 167–171. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Syeda, A.B.; Jadoon, A.; Chaudhry, M.N. Life Cycle Assessment Modelling of Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Existing and Proposed Municipal Solid Waste Management System of Lahore, Pakistan. Sustainability 2017 , 9 , 2242. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Irfan, M. Disamenity impact of Nala Lai (open sewer) on house rent in Rawalpindi city. Environ. Econ. Policy Stud. 2017 , 19 , 77–97. [ Google Scholar ]

- Aleisa, E.; Al-Jarallah, R. A triple bottom line evaluation of solid waste management strategies: A case study for an arid Gulf State, Kuwait. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2018 , 23 , 1460–1475. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Malakahmad, A.; Abualqumboz, M.S.; Kutty SR, M.; Abunama, T.J. Assessment of carbon footprint emissions and environmental concerns of solid waste treatment and disposal techniques; case study of Malaysia. Waste Manag. 2017 , 70 , 282–292. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Miner, J.K.; Rampedi, T.I.; Ifegbesan, P.A.; Machete, F. Survey on Household Awareness and Willingness to Participate in E-Waste Management in Jos, Plateau State, Nigeria. Sustainability 2020 , 12 , 1047. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Xu, L.; Ling, M.; Lu, Y.; Shen, M. Understanding household waste separation behavior: Testing the roles of moral, past experience, and perceived policy effectiveness within the theory of planned behavior. Sustainability 2017 , 9 , 625. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- IPCC. Fifth Assessment Report on Climate Change: Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change ; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. [ Google Scholar ]

- Mudga, V.; Madaan, N.; Mudgal, A.; Singh, R.B.; Mishra, A. Effect of toxic metals on human health. Open Nutraceuticals J. 2010 , 3 , 94–99. [ Google Scholar ]

- Njoku, P.O.; Edokpayi, J.N.; Odiyo, J.O. Health and environmental risks of residents living close to a landfill: A case study of thohoyandou landfill, Limpopo province, South Africa. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019 , 16 , 2125. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ] [ Green Version ]

- Nwanta, J.A.; Ezenduka, E. Analysis of Nsukka Metropolitan Abattoir Solid Waste in South Eastern Nigeria: Public Health Implications. Arch. Environ. Occup. Health 2010 , 65 , 21–26. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Karija, M.K.; Shihua, Q.I.; Lukaw, Y.S. The impact of poor municipal solid waste management practices and sanitation status on water quality and public health in cities of the least developed countries: The case of Juba, South Sudan. Int. J. Appl. Sci. Technol. 2013 , 3 , 87–99. [ Google Scholar ]

- Karshima, S.N. Public health implications of poor municipal waste management in Nigeria. Vom J. Vet. Sci. 2016 , 11 , 142–148. [ Google Scholar ]

- Serge Kubanza, N.; Simatele, M.D. Sustainable solid waste management in developing countries: A study of institutional strengthening for solid waste management in Johannesburg, South Africa. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2020 , 63 , 175–188. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Awosan, K.J.; Oche, M.O.; Yunusa, E.U.; Raji, M.O.; Isah, B.A.; Aminu, K.U.; Kuna, A.M. Knowledge, risk perception and practices regarding the hazards of unsanitary solid waste disposal among small-scale business operators in Sokoto, Nigeria. Int. J. Trop. Dis. Health 2017 , 26 , 1–10. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Omar, D.; Karuppanan, S.; AyuniShafiea, F. Environmental health impact assessment of a sanitary landfill in an urban setting. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012 , 68 , 146–155. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Palmiotto, M.; Fattore, E.; Paiano, V.; Celeste, G.; Colombo, A.; Davoli, E. Influence of a municipal solid waste landfill in the surrounding environment: Toxicological risk and odor nuisance effects. Environ. Int. 2014 , 68 , 16–24. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Osman, A.D.A.B.; Jusoh, M.S.; Amlus, M.H.; Khotob, N. Exploring The Relationship Between Environmental Knowledge and Environmental Attitude Towards Pro-Environmental Behavior: Undergraduate Business Students Perspective. Am. Eurasian J. Sustain. Agric. 2014 , 8 , 1–4. [ Google Scholar ]

- Yadav, P.; Samadder, S.R. Environmental impact assessment of municipal solid waste management options using life cycle assessment: A case study. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018 , 25 , 838–854. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modelling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988 , 103 , 411–423. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate Data Analysis ; Prentice Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [ Google Scholar ]

- Raza, M.H.; Abid, M.; Yan, T.; Ali Naqvi, S.A.; Akhtar, S.; Faisal, M. Understanding farmers’ intentions to adopt sustainable crop residue management practices: A structural equation modeling approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2019 , 227 , 613–623. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Raza, M.H.; Bakhsh, A.; Kamran, M. Managing climate change for wheat production: An evidence from southern Punjab, Pakistan. J. Econ. Impact. 2019 , 1 , 48–58. [ Google Scholar ]

- López-Mosquera, N.; García, T.; Barrena, R. An extension of the theory of planned behaviour to predict willingness to pay for the conservation of an urban park. J. Environ. Manag. 2014 , 135 , 91–99. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- DeVellis, R.F. Scale Development: Theory and Applications, Applied Social Research Methods Series ; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1991. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Bagozzi, R.P. The effects of arousal on the organization of positive and negative affect and cognitions: Application to attitude theory. Struct. Equ. Model. 1994 , 1 , 222–252. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Bentler, P.M. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychol. Bull. 1990 , 107 , 238. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Henry, J.W.; Stone, R.W. A Structural Equation Model of End-User Satisfaction with a Computer-Based Medical Information System. Inform. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 1994 , 7 , 21–33. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling ; Guilford Publication: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Chen, M.F.; Tung, P.J. Developing an extended Theory of Planned Behavior model to predict consumers’ intention to visit green hotels. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014 , 36 , 221–230. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]