- Our Mission

4 Strategies for Sparking Critical Thinking in Young Students

Fostering investigative conversation in grades K–2 isn’t easy, but it can be a great vehicle to promote critical thinking.

In the middle of class, a kindergartner spotted an ant and asked the teacher, “Why do ants come into the classroom?” Fairly quickly, educational consultant Cecilia Cabrera Martirena writes , students started sharing their theories: Maybe the ants were cold, or looking for food, or lonely.

Their teacher started a KWL chart to organize what students already knew, what they wanted to know, and, later, what they had learned. “As many of the learners didn’t read or write yet, the KWL was created with drawings and one or two words,” Cabrera Martirena writes. “Then, as a group, they decided how they could gather information to answer that first question, and some possible research routes were designed.”

As early elementary teachers know, young learners are able to engage in critical thinking and participate in nuanced conversations, with appropriate supports. What can teachers do to foster these discussions? Elementary teacher Jennifer Orr considered a few ideas in an article for ASCD .

“An interesting question and the discussion that follows can open up paths of critical thinking for students at any age,” Orr says. “With a few thoughtful prompts and a lot of noticing and modeling, we as educators can help young students engage in these types of academic conversations in ways that deepen their learning and develop their critical thinking skills.”

While this may not be an “easy process,” Orr writes—for the kids or the teacher—the payoff is students who from a young age are able to communicate new ideas and questions; listen and truly hear the thoughts of others; respectfully agree, disagree, or build off of their peers’ opinions; and revise their thinking.

4 Strategies for Kick-Starting Powerful Conversations

1. Encourage Friendly Debate: For many elementary-aged children, it doesn’t take much provoking for them to share their opinions, especially if they disagree with each other. Working with open-ended prompts that “engage their interest and pique their curiosity” is one key to sparking organic engagement, Orr writes. Look for prompts that allow them to take a stance, arguing for or against something they feel strongly about.

For example, Orr says, you could try telling first graders that a square is a rectangle to start a debate. Early childhood educator Sarah Griffin proposes some great math talk questions that can yield similar results:

- How many crayons can fit in a box?

- Which takes more snow to build: one igloo or 20 snowballs?

- Estimate how many tissues are in a box.

- How many books can you fit in your backpack?

- Which would take less time: cleaning your room or reading a book?

- Which would you rather use to measure a Christmas tree: a roll of ribbon or a candy cane? Why?

Using pictures can inspire interesting math discussions as well, writes K–6 math coach Kristen Acosta . Explore counting, addition, and subtraction by introducing kids to pictures “that have missing pieces or spaces” or “pictures where the objects are scattered.” For example, try showing students a photo of a carton of eggs with a few eggs missing. Ask questions like, “what do you notice?” and “what do you wonder?” and see how opinions differ.

2. Put Your Students in the Question: Centering students’ viewpoints in a question or discussion prompt can foster deeper thinking, Orr writes. During a unit in which kids learned about ladybugs, she asked her third graders, “What are four living and four nonliving things you would need and want if you were designing your own ecosystem?” This not only required students to analyze the components of an ecosystem but also made the lesson personal by inviting them to dream one up from scratch.

Educator Todd Finley has a list of interesting writing prompts for different grades that can instead be used to kick off classroom discussions. Examples for early elementary students include:

- Which is better, giant muscles or incredible speed? Why?

- What’s the most beautiful person, place, or thing you’ve ever seen? Share what makes that person, place, or thing so special.

- What TV or movie characters do you wish were real? Why?

- Describe a routine that you often or always do (in the morning, when you get home, Friday nights, before a game, etc.).

- What are examples of things you want versus things you need?

3. Open Several Doors: While some students take to classroom discussions like a duck to water, others may prefer to stay on dry land. Offering low-stakes opportunities for students to dip a toe into the conversation can be a great way to ensure that everyone in the room can be heard. Try introducing hand signals that indicate agreement, disagreement, and more. Since everyone can indicate their opinion silently, this supports students who are reluctant to speak, and can help get the conversation started.

Similarly, elementary school teacher Raquel Linares uses participation cards —a set of different colored index cards, each labeled with a phrase like “I agree,” “I disagree,” or “I don’t know how to respond.” “We use them to assess students’ understanding, but we also use them to give students a voice,” Linares says. “We obviously cannot have 24 scholars speaking at the same time, but we want everyone to feel their ideas matter. Even if I am very shy and I don’t feel comfortable, my voice is still heard.” Once the students have held up the appropriate card, the discussion gets going.

4. Provide Discussion Sentence Starters: Young students often want to add their contribution without connecting it to what their peers have said, writes district-level literacy leader Gwen Blumberg . Keeping an ear out for what students are saying to each other is an important starting point when trying to “lift the level of talk” in your classroom. Are kids “putting thoughts into words and able to keep a conversation going?” she asks.

Introducing sentence starters like “I agree…” or “I feel differently…” can help demonstrate for students how they can connect what their classmate is saying to what they would like to say, which grows the conversation, Blumberg says. Phrases like “I’d like to add…” help students “build a bridge from someone else’s idea to their own.”

Additionally, “noticing and naming the positive things students are doing, both in their conversation skills and in the thinking they are demonstrating,” Orr writes, can shine a light for the class on what success looks like. Celebrating when students use these sentence stems correctly, for example, helps reinforce these behaviors.

“Students’ ability to clearly communicate with others in conversation is a critical literacy skill,” Blumberg writes, and teachers in grades K–2 can get students started on the path to developing this skill by harnessing their natural curiosity and modeling conversation moves.

- NAEYC Login

- Member Profile

- Hello Community

- Accreditation Portal

- Online Learning

- Online Store

Popular Searches: DAP ; Coping with COVID-19 ; E-books ; Anti-Bias Education ; Online Store

Conversations with Children! Asking Questions That Stretch Children’s Thinking

You are here

When we ask children questions—especially big, open-ended questions—we support their language development and critical thinking. We can encourage them to tell us about themselves and talk about the materials they are using, their ideas, and their reflections.

This is the fifth and final article in this TYC series about asking questions that support rich conversations. During the past year, Conversations with Children! has documented and analyzed the many different types of questions teachers ask and the rich discussions with children that flowed from those questions. The series has explored children’s interests, considered their developmental needs, respected their cultural perspectives, and highlighted their language development and thinking.

Using an adaptation of Bloom’s Taxonomy to think about the types of questions teachers ask children, this article focuses on intentionally using questions that challenge children to analyze, evaluate, and create. This can increase the back-and-forth dialogues teachers have with children—stretching children’s thinking!

For this article, I spent the morning in a classroom of 3- and 4-year-olds, located in a large, urban elementary school in Passaic, New Jersey. All 15 children spoke both Spanish and English (with varying levels of English proficiency), as did their teacher and assistant teacher. The teachers in this classroom stretch their conversations with children, having extended exchanges in both languages by listening to and building on children’s answers.

Understanding Different Types of Questions

Bloom’s Taxonomy has long been used as a way to think about the types of questions we ask students. We have adapted it for young children. Although Remember has mostly right or wrong one-word answers and Create invites use of the imagination and answers that are complex and unique to each child, these levels are just guides. It is up to you to consider which types of questions are appropriate for each child you work with. The lower levels form the foundation for the higher ones.

identify, name, count, repeat, recall

describe, discuss, explain, summarize

explain why, dramatize, identify with/relate to

recognize change, experiment, infer, compare, contrast

express opinion, judge, defend/criticize

make, construct, design, author

A conversation about building with cups in the makerspace

A conversation between the teacher and two children began during planning time and continued as the children built in the makerspace.

During planning time

Teacher : I am excited to see how you will build with the cups. Do you have any idea how you will build with them? ( Analyze )

Child 1 : I will show you what I can do. ( He draws his plan on a piece of paper .)

Child 2 : I want to work with the cups too.

Teacher : Maybe you can collaborate and share ideas.

Child 2 : Yeah, we can work together.

Child 1 : We can build a tower.

Teacher : I wonder how tall it will be. I am very curious. I wonder, what will you do with the cups? ( Create ) I can’t wait to see!

Later, as the first child is building

Teacher : Can you describe what you did? ( Understand )

Child : I put these two and put these one at a time and then these two.

Teacher : How did you stack these differently? ( Analyze ) (The child doesn’t respond.)

Teacher : I noticed you stacked this one and this one in a diff erent way. How did you stack them differently? ( Analyze )

Child : (He becomes excited, pointing.) I show you!

Teacher : Please demonstrate!

Child : I knew what my idea was. (He shows the teacher how he stacked the cups.)

Teacher : Can you describe what parts of the cups were touching? ( Understand )

Child : The white part. Teacher: Oh, that is called the rim of the cup. How did you stack this one? ( Apply )

Child : I was trying and trying and trying!

Teacher : So you are stacking the rims together. And how is this stack different? ( Analyze )

Child : This one is the right way and this one is down.

Teacher : Oh, this one is right side up and this one is upside down!

A conversation about creating a zoo in the block area

The children were preparing for a visit to a local zoo. After listening to the teacher read several books about zoos, one child worked on building structures in the block area to house giraff es and elephants.

Teacher : I am excited to see how you are building the enclosures.

Child : It fell down and I’m making it different.

Teacher : So it fell down and now you’re thinking about building it a different way. Architects do that; they talk about the stability of the structure. How can you make it sturdier so it doesn’t fall? ( Evaluate )

Child : I’m trying to make a watering place for the elephant to drink water. I have to make it strong so he can drink and the water doesn’t go out.

Teacher : Maybe you can be the architect and draw the plans and your friend can be the engineer and build it. How do you feel about that? ( Evaluate )

Child : I’m gonna ask him.

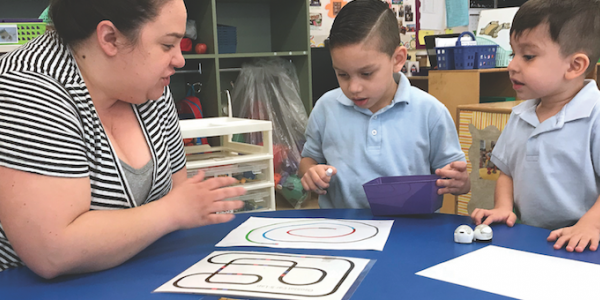

A conversation about coding with robots

The children had been using the Ozobot Bit, a small robot that introduces children to coding, for many months. Because these robots are programmed to follow lines and respond to specific color patterns (e.g., coloring small segments of the line blue, red, and green will make the robot turn right), preschoolers engage in a basic form of coding just by drawing lines. In this conversation, the teacher helps a child develop his own code.

Teacher : So tell me: what do we have to do first? ( Understand )

Child : (He draws as he speaks.) You have to keep going.

Teacher : Why do we have to do it that way first? ( Apply )

Child : Because have to draw it ’fore it can go. And you don’t draw it, it don’t go nowhere. Wanna see?

Teacher : So if it’s not on the line, it won’t go anywhere. It only goes on the line.

Child : Yeah.

Teacher : Okay. So are there any rules you have to follow? What rules do I need to know? ( Apply , Analyze , Evaluate )

Child : You can’t stop it with your hand. . . . And if you want to make another one, first you have to turn it off and then you make another one. (He demonstrates with four markers how to code on the paper and then puts the robot on the line.) Now it going backwards.

Teacher : So how could you fix it so it continues? ( Analyze , Evaluate , Create )

Child : (He makes the black line on the paper thicker and retries the Ozobot, but it still stops and turns around.)

Teacher : How can you fix it? Try something else to solve the problem. What should we try next? ( Analyze , Evaluate , Create )

Child : I gonna do the whole thing again. (The child starts drawing the code.)

A conversation to stretch dramatic play

A child held a baby doll and a girl doll as the teacher entered the dramatic play area.

Teacher : Tell me about the baby. ( Apply )

Child : This girl has a baby. We going to the doctor because we all sick.

Teacher : How do you think the doctor will help you get better? ( Evaluate )

Child : The doctor has to check my heart and then he gonna check my mouth.

Teacher : So what can you do to help your friends get better after the doctor checks your mouth and heart? How will you take care of them and yourself? ( Apply , Analyze , Evaluate )

Child : They go to bed back home and go to sleep.

Teacher : And what will you do? Tell me more about that. ( Apply , Analyze , Evaluate )

Child : I’m going read them a book.

Teacher : Oh, that is such a good idea! Do you have a special book in mind? ( Understand , Apply )

Child : (She nods her head in affirmation and smiles broadly.) I have a special book. (She holds up My House: A Book in Two Languages/Mi Casa: Un Libro en Dos Lenguas , by Rebecca Emberley.)

Teacher : Will you read the book to me? I’ll pretend that I am sick and I am in the bed and you can read the book to me. (The child gives the teacher a small blanket.) You are giving me my blankie. You read and I’ll listen. ( Apply , Create ) (The child invents her own story as she turns the pages.)

As the teacher, it’s up to you, the one who knows your students best in an educational setting, to decide which questions are appropriate for which children during a particular interaction. It can be challenging to develop and ask questions that engage children in analyzing, evaluating, and creating, such as, “If you could come to school any way you wanted, how would you get here? Why?” But questions that each child will answer in her own way are well worth the effort!

Note : Thank you, Megan (teacher), Ms. Perez (assistant teacher), and all of the wonderful students who taught me so much about coding! In addition to being the teacher, Megan King is the author of the chapter “A Makerspace in the Science Area” in the book Big Questions for Young Minds: Extending Children’s Thinking . And a great big final thank-you to the five preschool classrooms that invited me into their worlds, sharing their questions and conversations with TYC readers.

Suggestions for Intentionally Stretching Conversations with Young Children

- Make sure to allow plenty of wait time for children to process what you are saying, think about it, and answer. Give them at least a few seconds, but vary this according to the children’s needs.

- Listen to the children’s responses. Use active listening strategies: make eye contact, encourage children to share their ideas, and restate or summarize what they say.

- Ask another quesiton or make a comment after the child answers. If you aren’t sure how to respond, you can almost always say, “What else can we add to that?” or “Tell me more about that.”

More high-level questions to spark conversations

In the makerspace:

- Which material worked better in this experiment? Why? ( Analyze )

- What are some reasons your machine worked/didn’t work? How will you change it now? ( Evaluate )

- What will you be constructing today? Can you draw your plans? ( Create )

In the block area:

- How is the house you built different from/the same as your home? ( Analyze )

- What do you think would happen if we removed this block to make a doorway or window? ( Evaluate )

- How will you create on paper the house you want to build? What details will you write or draw so you can remember what you want to build in case you don’t have time to finish today? ( Create )

With robots:

- Why do you think the robot got stuck? ( Evaluate )

- Why didn’t the code work this time? ( Evaluate )

- How will you design a game for the robots to play? ( Create )

During dramatic play:

- How could you turn this piece of fabric into part of your costume? ( Analyze )

- How could we change the house area to make it cozier for the babies? ( Evaluate )

- I wrote down the story you told your patient when she said she was afraid of the dentist. Can you illustrate the story to make a picture book? ( Create )

Photographs: Courtesy of the author

Janis Strasser, EdD, is a teacher educator and coordinator of the MEd in Curriculum and Learning Early Childhood concentration at William Paterson University in Wayne, New Jersey. She has worked in the field of early childhood for more than 40 years.

Vol. 12, No. 3

Print this article

MSU Extension Child & Family Development

The importance of critical thinking for young children.

Kylie Rymanowicz, Michigan State University Extension - May 03, 2016

Critical thinking is essential life skill. Learn why it is so important and how you can help children learn and practice these skills.

We use critical thinking skills every day. They help us to make good decisions, understand the consequences of our actions and solve problems. These incredibly important skills are used in everything from putting together puzzles to mapping out the best route to work. It’s the process of using focus and self-control to solve problems and set and follow through on goals. It utilizes other important life skills like making connections , perspective taking and communicating . Basically, critical thinking helps us make good, sound decisions.

Critical thinking

In her book, “Mind in the Making: The seven essential life skills every child needs,” author Ellen Galinsky explains the importance of teaching children critical thinking skills. A child’s natural curiosity helps lay the foundation for critical thinking. Critical thinking requires us to take in information, analyze it and make judgements about it, and that type of active engagement requires imagination and inquisitiveness. As children take in new information, they fill up a library of sorts within their brain. They have to think about how the new information fits in with what they already know, or if it changes any information we already hold to be true.

Supporting the development of critical thinking

Michigan State University Extension has some tips on helping your child learn and practice critical thinking.

- Encourage pursuits of curiosity . The dreaded “why” phase. Help them form and test theories, experiment and try to understand how the world works. Encourage children to explore, ask questions, test their theories, think critically about results and think about changes they could make or things they could do differently.

- Learn from others. Help children think more deeply about things by instilling a love for learning and a desire to understand how things work. Seek out the answers to all of your children’s “why” questions using books, the internet, friends, family or other experts.

- Help children evaluate information. We are often given lots of information at a time, and it is important we evaluate that information to determine if it is true, important and whether or not we should believe it. Help children learn these skills by teaching them to evaluate new information. Have them think about where or who the information is coming from, how it relates to what they already know and why it is or is not important.

- Promote children’s interests. When children are deeply vested in a topic or pursuit, they are more engaged and willing to experiment. The process of expanding their knowledge brings about a lot of opportunities for critical thinking, so to encourage this action helps your child invest in their interests. Whether it is learning about trucks and vehicles or a keen interest in insects, help your child follow their passion.

- Teach problem-solving skills. When dealing with problems or conflicts, it is necessary to use critical thinking skills to understand the problem and come up with possible solutions, so teach them the steps of problem-solving and they will use critical thinking in the process of finding solutions to problems.

For more articles on child development, academic success, parenting and life skill development, please visit the MSU Extension website.

This article was published by Michigan State University Extension . For more information, visit https://extension.msu.edu . To have a digest of information delivered straight to your email inbox, visit https://extension.msu.edu/newsletters . To contact an expert in your area, visit https://extension.msu.edu/experts , or call 888-MSUE4MI (888-678-3464).

Did you find this article useful?

Early childhood development resources for early childhood professionals.

new - method size: 3 - Random key: 2, method: personalized - key: 2

You Might Also Be Interested In

MSU researcher awarded five-year, $2.5 million grant to develop risk assessment training program

Published on October 13, 2020

MSU Product Center helps Michigan food entrepreneurs survive and thrive throughout pandemic

Published on August 31, 2021

Protecting Michigan’s environment and wildlife through the Conservation Reserve Enhancement Program

Published on September 1, 2021

MSU Extension to undertake three-year, $7 million vaccination education effort

Published on August 17, 2021

MSU to study precision livestock farming adoption trends in U.S. swine industry

Published on March 15, 2021

MSU research team receives USDA grant to evaluate effectiveness, cost of new blueberry pest management strategies

Published on February 19, 2021

- approaches to learning

- child & family development

- cognition and general knowledge

- early childhood development

- life skills

- msu extension

- rest time refreshers

- approaches to learning,

- child & family development,

- cognition and general knowledge,

- early childhood development,

- life skills,

- msu extension,

- Trying to Conceive

- Signs & Symptoms

- Pregnancy Tests

- Fertility Testing

- Fertility Treatment

- Weeks & Trimesters

- Staying Healthy

- Preparing for Baby

- Complications & Concerns

- Pregnancy Loss

- Breastfeeding

- School-Aged Kids

- Raising Kids

- Personal Stories

- Everyday Wellness

- Safety & First Aid

- Immunizations

- Food & Nutrition

- Active Play

- Pregnancy Products

- Nursery & Sleep Products

- Nursing & Feeding Products

- Clothing & Accessories

- Toys & Gifts

- Ovulation Calculator

- Pregnancy Due Date Calculator

- How to Talk About Postpartum Depression

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

How to Teach Your Child to Be a Critical Thinker

Blue Planet Studio / iStockphoto

What Is Critical Thinking?

- Importance of Critical Thinking

Benefits of Critical Thinking Skills

- Teach Kids to Be Critical Thinkers

Every day kids are bombarded with messages, information, and images. Whether they are at school, online, or talking to their friends, they need to know how to evaluate what they are hearing and seeing in order to form their own opinions and beliefs. Critical thinking skills are the foundation of education as well as an important life skill. Without the ability to think critically, kids will struggle academically, especially as they get older.

In fact, no matter what your child plans to do professionally someday, they will need to know how to think critically, solve problems, and make decisions. As a parent, it's important that you ensure that your kids can think for themselves and have developed a healthy critical mindset before they leave the nest.

Doing so will help them succeed both academically and professionally as well as benefit their future relationships. Here is what you need to know about critical thinking, including how to teach your kids to be critical thinkers.

Critical thinking skills are the ability to imagine, analyze, and evaluate information in order to determine its integrity and validity, such as what is factual and what isn't. These skills help people form opinions and ideas as well as help them know who is being a good friend and who isn't.

"Critical thinking also can involve taking a complex problem and developing clear solutions," says Amy Morin, LCSW, a psychotherapist and author of the best-selling books "13 Things Mentally Strong People Don't Do" and "13 Things Mentally Strong Parents Don't Do."

In fact, critical thinking is an essential part of problem-solving, decision-making, and goal-setting . It also is the basis of education, especially when combined with reading comprehension . These two skills together allow kids to master information.

Why Critical Thinking Skills Are Important

According to the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), which evaluated 15-year-old children in 44 different countries, more than one in six students in the United States are unable to solve critical thinking problems. What's more, research indicates that kids who lack critical thinking skills face a higher risk of behavioral problems.

If kids are not being critical thinkers, then they are not thinking carefully, says Amanda Pickerill, Ph.D. Pickerill is licensed with the Ohio Department of Education and the Ohio Board of Psychology and is in practice at the Ohio State School for the Blind in Columbus, Ohio.

"Not thinking carefully [and critically] can lead to information being misconstrued; [and] misconstrued information can lead to problems in school, work, and relationships," she says.

Critical thinking also allows kids to gain a deeper understanding of the world including how they see themselves in that world. Additionally, kids who learn to think critically tend to be observant and open-minded.

Amy Morin, LCSW

Critical thinking skills can help someone better understand themselves, other people, and the world around them. [They] can assist in everyday problem-solving, creativity, and productivity.

There are many ways critical thinking skills can benefit your child, Dr. Pickerill says. From being able to solve complex problems in school and determining how they feel about particular issues to building relationships and dealing with peer pressure, critical thinking skills equip your child to deal with life's challenges and obstacles.

"Critical thinking skills [are beneficial] in solving a math problem, in comparing and contrasting [things], and when forming an argument," Dr. Pickerill says. "As a psychologist, I find critical thinking skills also to be helpful in self-reflection. When an individual is struggling to reach a personal goal or to maintain a satisfactory relationship it is very helpful to apply critical thinking."

Critical thinking also fosters independence, enhances creativity, and encourages curiosity. Kids who are taught to use critical thinking skills ask a lot of questions and never just take things at face value—they want to know the "why" behind things.

"Good critical thinking skills also can lead to better relationships, reduced distress, and improved life satisfaction," says Morin. "Someone who can solve everyday problems is likely to feel more confident in their ability to handle whatever challenges life throws their way."

How to Teach Kids to Be Critical Thinkers

Teaching kids to think critically is an important part of parenting. In fact, when we teach kids to be critical thinkers, we are also teaching them to be independent . They learn to form their own opinions and come to their own conclusions without a lot of outside influence. Here are some ways that you can teach your kids to become critical thinkers.

Be a Good Role Model

Sometimes the best way to teach your kids an important life skill is to model it in your own life. After all, kids tend to copy the behaviors they see in their parents. Be sure you are modeling critical thinking in your own life by researching things that sound untrue and challenging statements that seem unethical or unfair.

"Parents, being the critical thinkers that they are, can begin modeling critical thinking from day one by verbalizing their thinking skills," Dr. Pickerill says. "It’s great for children to hear how parents critically think things through. This modeling of critical thinking allows children to observe their parents' thought processes and that modeling lends itself to the child imitating what [they have] observed."

Play With Them

Children are constantly learning by trial and error and play is a great trial and error activity, says Dr, Pickerill. In fact, regularly playing with your child at a very young age is setting the foundation for critical thinking and the depth of their critical thinking skills will advance as they develop, she says.

"You will find your child’s thinking will be more on a concrete level in the earlier years and as they advance in age it will become more abstract," Dr. Pickerill says. "Peer play is also helpful in developing critical thinking skills but parents need to be available to assist when conflicts arise or when bantering takes a turn for the worse."

As your kids get older, you can play board games together or simply spend time talking about something of interest to them. The key is that you are spending quality time together that allows you the opportunity to discuss things on a deeper level and to examine issues critically.

Teach Them to Solve Problems

Morin says one way to teach kids to think critically is to teach them how to solve problems. For instance, ask them to brainstorm at least five different ways to solve a particular problem, she says.

"You might challenge them to move an object from one side of the room to the other without using their hands," she says. "At first, they might think it’s impossible. But with a little support from you, they might see there are dozens of solutions (like using their feet or putting on gloves). Help them brainstorm a variety of solutions to the same problem and then pick one to see if it works."

Over time, you can help your kids see that there are many ways to view and solve the same problem, Morin says.

Encourage Them to Ask Questions

As exhausting as it can be at times to answer a constant barrage of questions, it's important that you encourage your child to question things. Asking questions is the basis of critical thinking and the time you invest in answering your child's questions—or finding the answers together— will pay off in the end.

Your child will learn not only learn how to articulate themselves, but they also will get better and better at identifying untrue or misleading information or statements from others. You also can model this type of questioning behavior by allowing your child to see you question things as well.

Practice Making Choices

Like everything in life, your child will often learn through trial and error. And, part of learning to be a critical thinker involves making decisions. One way that you can get your child thinking about and making choices is to give them a say in how they want to spend their time.

Allow them to say no thank-you to playdates or party invitations if they want. You also can give them an allowance and allow them to make some choices about what to do with the money. Either of these scenarios requires your child to think critically about their choices and the potential consequences before they make a decision.

As they get older, talk to them about how to deal with issues like bullying and peer pressure . And coach them on how to make healthy choices regarding social media use . All of these situations require critical thinking on your child's part.

Encourage Open-Mindedness

Although teaching open-mindedness can be a challenging concept to teach at times, it is an important one. Part of becoming a critical thinker is the ability to be objective and evaluate ideas without bias.

Teach your kids that in order to look at things with an open mind, they need leave their own judgments and assumptions aside. Some concepts you should be talking about that encourage open-mindedness include diversity , inclusiveness , and fairness.

A Word From Verywell

Developing a critical mindset is one of the most important life skills you can impart to your kids. In fact, in today's information-saturated world, they need these skills in order to thrive and survive. These skills will help them make better decisions, form healthy relationships, and determine what they value and believe.

Plus, when you teach your kids to critically examine the world around them, you are giving them an advantage that will serve them for years to come—one that will benefit them academically, professionally, and relationally. In the end, they will not only be able to think for themselves, but they also will become more capable adults someday.

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA): Results from PISA 2012 problem-solving .

Sun RC, Hui EK. Cognitive competence as a positive youth development construct: a conceptual review . ScientificWorldJournal . 2012;2012:210953. doi:10.1100/2012/210953

Ghazivakili Z, Norouzi Nia R, Panahi F, Karimi M, Gholsorkhi H, Ahmadi Z. The role of critical thinking skills and learning styles of university students in their academic performance . J Adv Med Educ Prof . 2014;2(3):95-102. PMID:25512928

Schmaltz RM, Jansen E, Wenckowski N. Redefining critical thinking: teaching students to think like scientists . Front Psychol . 2017;8:459. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00459

By Sherri Gordon Sherri Gordon, CLC is a published author, certified professional life coach, and bullying prevention expert.

For Employers

Bright horizons family solutions, bright horizons edassist solutions, bright horizons workforce consulting, featured industry: healthcare, find a center.

Locate our child care centers, preschools, and schools near you

Need to make a reservation to use your Bright Horizons Back-Up Care?

I'm interested in

Developing critical thinking skills in kids.

Developing Critical Thinking Skills

Learning to think critically may be one of the most important skills that today's children will need for the future. In today’s rapidly changing world, children need to be able to do much more than repeat a list of facts; they need to be critical thinkers who can make sense of information, analyze, compare, contrast, make inferences, and generate higher order thinking skills.

Building Your Child's Critical Thinking Skills

Building critical thinking skills happens through day-to-day interactions as you talk with your child, ask open-ended questions, and allow your child to experiment and solve problems. Here are some tips and ideas to help children build a foundation for critical thinking:

- Provide opportunities for play . Building with blocks, acting out roles with friends, or playing board games all build children’s critical thinking.

- Pause and wait. Offering your child ample time to think, attempt a task, or generate a response is critical. This gives your child a chance to reflect on her response and perhaps refine, rather than responding with their very first gut reaction.

- Don't intervene immediately. Kids need challenges to grow. Wait and watch before you jump in to solve a problem.

- Ask open-ended questions. Rather than automatically giving answers to the questions your child raises, help them think critically by asking questions in return: "What ideas do you have? What do you think is happening here?" Respect their responses whether you view them as correct or not. You could say, "That is interesting. Tell me why you think that."

- Help children develop hypotheses. Taking a moment to form hypotheses during play is a critical thinking exercise that helps develop skills. Try asking your child, "If we do this, what do you think will happen?" or "Let's predict what we think will happen next."

- Encourage thinking in new and different ways. By allowing children to think differently, you're helping them hone their creative problem solving skills. Ask questions like, "What other ideas could we try?" or encourage your child to generate options by saying, "Let’s think of all the possible solutions."

Of course, there are situations where you as a parent need to step in. At these times, it is helpful to model your own critical thinking. As you work through a decision making process, verbalize what is happening inside your mind. Children learn from observing how you think. Taking time to allow your child to navigate problems is integral to developing your child's critical thinking skills in the long run.

Recommended for you

- preparing for kindergarten

- language development

- Working Parents

- digital age parenting

- Student Loans

We have a library of resources for you about all kinds of topics like this!

Birth To 5 Matters

Guidance by the sector, for the sector

Thinking Creatively and Critically (Thinking)

Having their own ideas (creative thinking) • Thinking of ideas that are new and meaningful to the child • Playing with possibilities (what if? what else?) • Visualising and imagining options • Finding new ways to do things

Making links (building theories) • Making links and noticing patterns in their experience • Making predictions • Testing their ideas • Developing ideas of grouping, sequences, cause and effect

Working with ideas (critical thinking) • Planning, making decisions about how to approach a task, solve a problem and reach a goal • Checking how well their activities are going • Flexibly changing strategy as needed • Reviewing how well the approach worked

• Use the language of thinking and learning: think, know, remember, forget, idea, makes sense, plan, learn, find out, confused, figure out, trying to do. • Model being a thinker, showing that you don’t always know, are curious and sometimes puzzled, and can think and find out. I wonder? • Give children time to talk and think. Make time to actively listen to children’s ideas. • Encourage open-ended thinking, generating more alternative ideas or solutions, by not settling on the first suggestions: What else is possible?. • Always respect children’s efforts and ideas, so they feel safe to take a risk with a new idea and feel comfortable with mistakes. • Encourage children to question and challenge assumptions. • Help children to make links to what they already know. • Support children’s interests over time, reminding them of previous approaches and encouraging them to make connections between their experiences. • Help children to become aware of their own goals, make plans, and to review their own progress and successes. Describe what you see them trying to do, and encourage children to talk about what they are doing, how they plan to do it, what worked well and what they would change next time. • Talking aloud helps children to think and control what they do. Model self-talk, describing your actions in play. • Value questions, talk, and many possible responses, without rushing toward answers too quickly. • Sustained shared thinking helps children to explore ideas and make links. Follow children’s lead in conversation, and think about things together. • Encourage children to choose personally meaningful ways to represent and clarify their thinking through graphics. • Take an interest in what the children say about their marks and signs, talk to them about their meanings and value what they do and say. • Encourage children to describe problems they encounter, and to suggest ways to solve the problem. • Show and talk about strategies – how to do things – including problem-solving, thinking and learning. • Encourage children to reflect and evaluate their work and review their own progress and learning. • Model the plan-do-review process yourself.

• In planning activities, ask yourself: Is this an opportunity for children to find their own ways to represent and develop their own ideas? Avoid children just reproducing someone else’s ideas. • Build in opportunities for children to play with materials before using them in planned tasks. • Play is a key opportunity for children to think creatively and flexibly, solve problems and link ideas. Establish the enabling conditions for rich play: space, time, flexible resources, choice, control, warm and supportive relationships. • Recognisable and predictable routines help children to predict and make connections in their experiences. • Routines can be flexible, while still basically orderly. • Provide extended periods of uninterrupted time so that children can develop their activities. • Keep significant activities out instead of routinely tidying them away, so that there are opportunities to revisit what they have been doing to explore possible further lines of enquiry. • Plan linked experiences that follow the ideas children are really thinking about. • Represent thinking visually, such as mind-maps to represent thinking together, finding out what children know and want to know. • Develop a learning community which focuses on how and not just what we are learning. • Setting leaders should give staff time to think about children’s needs, to make links between their knowledge and practice.

Previous page: Active Learning | Next page: Learning and Development

Creative and Critical Thinking in Early Childhood

- First Online: 02 January 2023

Cite this chapter

- Nicole Leggett 3 , 4

Part of the book series: Integrated Science ((IS,volume 13))

922 Accesses

1 Altmetric

Early childhood (from prenatal to eight years of life) is the most important period of growth in human development, with peak synaptic activity in all brain regions occurring in the first ten years of life. This time-sensitive course of brain development results in different functions emerging at different times. It is during the preschool years that sensitive periods for cognitive development are formed, in particular, creative and critical thinking skills. Sociocultural perspectives ascertain that a child’s cognition is co-constructed through the social environment. This chapter draws from Vygotsky’s sociocultural cognitive theory and creative imagination theory to explain the processes involved as young children generate new knowledge. Examples from children’s interactions in social learning environments are presented, demonstrating how children think creatively and critically as they solve problems and seek meaning through play and imagination.

Graphical Abstract/Art Performance

Collaborative problem-solving.

(Photography by Nicole Leggett).

Creativity is intelligence having fun. Albert Einstein

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

McCain MN, Mustard F, Shanker S (2007) Early years study 2. Putting science into action. Canada: The Council for Early Child Development, pp 7

Google Scholar

Shonkoff J, Boyce WT, McEwen B (2009) Neuroscience, molecular biology, and the childhood roots of health disparities: building a new framework for health promotion and disease prevention. J Am Med Assoc 301:2252–2259

Article CAS Google Scholar

Siegel DJ (2012) The developing mind: how relationships and the brain interact to shape who we are, 2nd edn. The Guilford Press, New York, NY

Berardi N, Sale A, Maffei L (2015) Brain structural and functional development: genetics and experience. Developmental Med Child Neurol 57 (2):4–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/dmcn.12691

Hensch TK, Bilimoria PM (2012) Re-opening windows: manipulating critical periods for brain development. Cerebrum. 2012 Jul–Aug; 2012: 11. PMCID: PMC3574806

Mustard F (2010) Early brain development and human development. In: Conference proceedings

Knudsen EI (2004) Sensitive periods in the development of the brain and behavior. J Cogn Neurosci 16:1412–1425

Article Google Scholar

Voss P (2013) Sensitive and critical periods in visual sensory deprivation. Frontiers in Psychology. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00664

Fox NA (2014) What do we know about sensitive periods in human development and how do we know it? Hum Dev 57(4):173–175. https://doi.org/10.1159/000363663

Gopnik A, Wellman HM (2012) Reconstructing constructivism: causal models, Bayesian learning mechanisms, and the theory theory. Psychol Bull 138:1085–1108

Armstrong VL, Brunet PM, He C Nishimura M, Poole HL, Spector FJ (2006) What is so critical?: A commentary on the re-examination of critical periods. Developmental Psychobiology 48(4):326–31. https://doi.org/10.1002/dev.20135

Zhang TY, Labonté B, Wen XL, Turecki G, Meaney MJ (2013) Epigenetic mechanisms for the early environmental regulation of hippocampal glucocorticoid receptor gene expression in rodents and humans. Neuropsychopharmacology 38:111–123

Wen XL, Turecki G, Meaney MJ (2013) Epigenetic mechanisms for early environmental regulation of hippocampal glucocorticoid receptor gene expression in rodents and humans. Neuropsychopharmacology 38:111–123

Vygotsky LS (1930/1978) Mind in society: the development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press

Vygotsky L (1930/1967/2004) Imagination and creativity in childhood. J Russian East European Psychol 42(1):7–97

John-Steiner V, Moran S (2012) Creativity in the making: Vygotsky’s contemporary contribution to the dialectic of development and creativity. Oxford Scholarship Online. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195149005.001.0001

John-Steiner V, Connery MC, Marjanovic-Shane A (2010) Dancing with the muses. In: Connery MC, John-Steiner V, Marjanovic-Shane A (eds), Vygotsky and creativity: a cultural-historical approach to play, meaning-making, and the arts. New York: Peter Lang Publishing, Inc, p 6

Vygotskij LS (1995) Fantasi och kreativitet i barndomen [Imagination and creativity in childhood]. Göteborg: Daidalos. (Original work published 1950)

Lindqvist G (2003) Vygotsky’s theory of creativity. Creat Res J 15(2):245–251. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15326934CRJ152&3_14

Vygotsky LS (1987) Imagination and its development in childhood. In: Rieber RW, Carton AS (eds) The collected works of L.S. Vygotsky (vol 1) New York: Plenum Press, pp 339

Smolucha L, Smolucha FC (1986, August). LS Vygotsky’s theory of creative imagination. Paper presented at 94th Annual Convention of the American psychological Association, Washington, DC, pp 4

Vygotsky LS (1976) Play and its role in the mental development of the child. In: Bruner JS, Jolly A, Sylva K (eds) Play-Its role in development and evolution. Penguin Books Ltd., New York, pp 537–554

Connery MC, John-Steiner V, Marjanovic-Shane A (eds), Vygotsky and creativity: a cultural-historical approach to play, meaning-making, and the arts. New York: Peter Lang Publishing, Inc

Freud S (1907) Creative writers and day-dreaming, pp 21

Scarlett WG, Naudeau S, Salonius-Pasternak D, Ponte I (2005) Play in early childhood: the golden age of make-believe Children’s play (pp 51–73). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc

Policastro E, Gardner H (1999) From case studies to robust generalisations: an approach to the study of creativity. In: Sternberg RJ (ed) Handbook of creativity. Cambridge University Press, New York, pp 213–225

Montessori (1946) Unpublished London Lecture #24, pp 95–96

Wang Z, Wang L (2015) Cognitive development: child education. In: Wright JD (ed) in chief), International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioural Sciences, vol 4, 2nd edn. Elsevier, Oxford, pp 38–42

Chapter Google Scholar

Gelman SA, Gottfried GM (2006) Creativity in young children’s thought. In: Kaufman JC, Baer J Creativity and reason in cognitive development. New York: Cambridge University Press

Holton G (1973) Thematic origins of scientific thought. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

Weisberg R (2006) Expertise and reasons in creative thinking. In: Kauffman JC, Baer J (eds) Creativity and reason in cognitive development. New York: Cambridge University Press

Doidge N (2007) The brain that changes itself. Stories of personal triumph from the frontiers of brain science. Penguin Group, New York

Eliot L (1999) What’s going on in there? How the brain and mind develop in the first five years of life. Bantam Books, New York

Goswami U (2004) Neuroscience and education: from research to practice? Br J Educ Psychol 74(2004):1–14

McCain M, Mustard F (1999) Reversing the real brain drain: early years study, final report. Toronto, ON: Ontario children’s secretariat

Siraj-Blatchford I (2005) Birth to eight matters! Seeking seamlessness—Continuity? Integration? Creativity? Paper presented at the TACTYC Annual conference, Cardiff

Wallas G (2014) The art of thought. Kent, England: Solis Press [first published in 1926]:39

Sawyer R (2006) Explaining creativity. Oxford University Press, The science of human innovation New York

Pfenninger K, Shubik V (2001) Insights into the foundations of creativity: a synthesis. In: Pfenninger K, Shubik V (eds.) The origins of creativity, pp 213–236. New York: Oxford University Press

Torrance EP (1996) Cumulative bibliography on the Torrance tests of creative thinking (brochure). Georgia Studies of Creative Behaviour, Athens

Moran J (1988) Creativity in young children. ERIC Clearinghouse on Elementary and Early Childhood Education ED306008

Gifford S (2010) Problem solving. In: Miller L, Cable C, Goodliff G (Eds.) Supporting children’s learning in the early years (2nd ed). London: Routledge

Runco M (2007) Creativity. Theories and themes: research, development, and practice. MA: Elsevier Academic Press

Sternberg R (2006) The nature of creativity. Creat Res J 18(1):87–98. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326934crj1801_10

Galinsky E (2010) Mind in the making. The seven essential life skills every child needs. Harper Collins Publishing, New York NY

Jones C, Pimdee P (2017) Innovative ideas: Thailand 4.0 and the fourth industrial revolution. Asian Int J Soc Sci 17(1): 4–35. https://doi.org/10.29139/aijss.20170101

Lubawy J (2006) From observation to reflection: a practitioner’s guide to programme planning and documentation. NSW, Australia: Joy and Pete Consulting, pp 15

Dangel JR, Durden TR (2008) Teacher-involved conversations with young children during small group activity. Early Years: An Int J Res Dev 28(3):235–250

Robson S, Hargreaves DJ (2005) What do early childhood practitioners think about young children’s thinking. Eur Early Child Educ Res J 13(1):81–96

Taggart G, Ridley K, Rudd P, Benefield P (2005) Thinking skills in the early years: a literature review. Slough: NFER

Gottfredson LS (1997) Mainstream science on intelligence: an editorial with 52 signatories, history, and bibliography. Intelligence 24:13–23

Halpern DF (2014) Thought and knowledge: an introduction to critical thinking, 5th edn. Psychology Press, New York, NY

Sternberg RJ (2005) Creativity or creativities. Int J Hum Comput Stud 63(4–5):370–382

Sterberg RJ, Torff B, Grigorenko EL (1999) Teaching triachically improves school achievement. J Educ Psychol 90:374–384

Tomasello M, Kruger AC, Ratner HH (1993) Cultural learning. Behav Brain Sci 16:495–511

Dissanayake E (2000) Art and intimacy: how the arts began. University of Washington Press, Seattle

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

University of Newcastle, Callaghan, Australia

Nicole Leggett

Integrated Science Association (ISA), Universal Scientific Education and Research Network (USERN), Callaghan, Australia

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Nicole Leggett .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Universal Scientific Education and Research Network (USERN), Stockholm, Sweden

Nima Rezaei

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Leggett, N. (2022). Creative and Critical Thinking in Early Childhood. In: Rezaei, N. (eds) Integrated Education and Learning. Integrated Science, vol 13. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-15963-3_7

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-15963-3_7

Published : 02 January 2023

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-031-15962-6

Online ISBN : 978-3-031-15963-3

eBook Packages : Education Education (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

ISSN 1179 - 6812

Subscribe >

- ABOUT HE KUPU

- CALL FOR PAPERS

- EDITORIAL REVIEW BOARD

Critical literacy in early childhood education: Questions that prompt critical conversations

Shu-yen law new zealand tertiary college, practitioner research: vol 6, no 3 - may 2020.

This article proposes the use of questioning as a strategy to foster and provoke children’s critical thinking through the medium of literacy. The art of questioning includes adults both asking questions in purposeful ways and eliciting children’s responses and questions. This strategy prompts children to make connections to prior knowledge and experiences, share perspectives, reflect on ideas and explore possible responses. This article is informed by both the author’s own research and a range of literature. Examples of questions and conversations are provided to demonstrate how critical thinking can be fostered in early childhood education settings. In this article, picture books are viewed as a valuable resource for teachers to nurture critical thinking as they can portray concepts and ideas that are meaningful and relevant for children.

Introduction

When children engage in shared reading with educators, they develop an understanding of the story and meaning of the world around them. This understanding can be deepened by supporting children to develop a critical stance so that they become confident to engage in critical discussions on current and meaningful topics that touch their lives. Picture book reading is not just about what children can see and hear, but also how it makes them feel, think and how these ideas might be applied to their lives. This comprises engagement in critical literacy: a learning journey where children are encouraged to think critically and reflect on meanings presented in texts. This article draws on findings from my own studies in China (Law & Zheng, 2013) and New Zealand (Law, 2012) to explore the ways in which teachers can use picture books to support the development of children’s critical thinking.

What is critical literacy and why is it important in early childhood education?

The origins of critical literacy can be traced to domains such as feminism, multiculturalism, critical theory, anti-racism, and post-structuralism, each presenting different perspectives on the influence of power dynamics in society (Janks, 2000). Comber (1999) clarifies that despite the different orientations, the starting point of these viewpoints are:

…about shaping young people who can analyse what is going on; who will ask why things are the way they are; who will question who benefits from the ways things are and who can imagine how things might be different and who can act to make things more equitable (p. 4).

Based on a literature review spanning thirty years, Lewison, Flint and van Sluys (2002) found that critical literacy provides educators with the opportunity to explore social issues and discuss ways children can contribute to positive change in the community (cited in Norris, Lucas, & Prudhoe, 2012). It is vital to encourage children to be open to different perspectives and explore challenging concepts presented in texts, such as diversity, divorce, stereotypes, bullying, disability, and poverty as these are issues relevant to people of all ages, including children in the early years (Lewison et el., 2002; Mankiw & Strasser, 2013). The objective of the discussion therefore does not stop at the analysis of text but includes reflection on one’s own experiences, which promotes social awareness and positive actions.

One might question how relevant social issues are to children in early childhood education. Ayers, Connolly, Harper and Bonnano (cited in Hawkins, 2014) point out that “children as young as three have the capability to develop negative attitudes and prejudices towards particular groups” (p. 725). The New Zealand Early Childhood Curriculum Te Whāriki: He whāriki mātauranga mō ngā mokopuna o Aotearoa (Te Whāriki) (MoE, 2017) supports the cultivation of social justice. The strand contribution voices the aspiration that children will demonstrate “confidence to stand up for themselves and others against biased ideas and discriminatory behaviour” (p. 37). Teachers can achieve this through creating opportunities for children to “discuss bias and to challenge prejudice and discriminatory attitudes” (p. 39). Therefore, young children can be involved in critical literacy through meaning making, perspective sharing, and reflecting on the social justice concepts presented in picture books.

Picture book reading

Picture book reading is an interactive, sociocultural experience, where adults and children can engage in collaborative learning (Helming & Reid, 2017; Norris et al., 2012). Picture books make great teaching tools as they bring in fresh perspectives on social issues, prompting children to explore concepts and consider how this might influence their actions (Robertson, 2018). When children’s perspectives broaden through critical discussions, positive attitudes towards others in society are also likely to take shape (Kim, 2016). Picture book reading also supports the development of oral language needed for critical thinking and discussion (Education Review Office [ERO], 2017). Shared picture book reading enables meaningful, shared conversations and the introduction of a wide vocabulary, while children ask questions and share their understandings and experiences (ERO, 2017). An example of this was evident in my study when children were asked during a reading session using the children’s book Don’t Panic Annika (Bell & Morris, 2011):

“What does that mean when you say ‘panic’? When did you feel scared?” to which a child responded: “When I was four or even three, every morning, I was scared and I could not even see my mum or my dad; I thought it was a monster”, while another expressed, “When I was trying to peel the potatoes, I thought I was going to hit my finger. I know what panicky means. You scream, crying and like stomping your feet” (Law, 2012, p. 66).

This question supported the children to connect a new word to their real life experiences, which helped them “make sense of learning, literacy, life and themselves” (MoE, 2009, p. 23). When teachers support children to learn new words through making connections to prior knowledge and experiences, children will then have the vocabulary needed to engage in further conversations around the topic.

The art of questioning

Questioning is defined by how adults ask questions meaningfully and how adults elicit children’s questions through strategies such as probing, listening, commenting, and modelling thinking out loud. Open-ended questions foster a good balance between a hands-on and hands-off approach to teaching as they provoke thinking while accepting individual unique perspectives. Open-ended questions promote open-mindedness and endless possibilities. A child-centred approach allows children to bring their own cultural perspectives and understanding of the world to the table, enabling them to make connections and form their own working theories (Peters & Kelly, 2011). These abilities to make meanings and connections, ask questions, consider multiple perspectives, and make predictions are also learning dispositions beneficial for success in reading (Whyte, 2019).

In addition to teacher questioning, children should be encouraged to be proactive at asking questions as well. It is vital to strike a balance between teacher questioning and child questioning where both engage in active listening and exchanging of thoughts, opinions, and wonderings based on personal experiences and feelings (Mackey & de Vocht-van Alphen, 2016). This can be achieved by moving away from the commonly used ‘teacher-question, student-answer, and teacher-reaction‘ pattern which can inhibit learning if used improperly, as it can cause excessive attention to guessing what is in the teacher’s mind rather than being creative in exploring more in-depth about the texts (MoE, 2003). Levy (2016) supports this noting the importance of creating learning environments where children are encouraged to ask questions and explore dominant discourses in texts, while teachers’ open-ended questions welcome individual opinions and model critical thinking. Te Whāriki (MoE, 2017)aspires for children to be active questioners and thinkers on issues in life that are relevant to them. Supporting this goal, children should be encouraged to inquire, reflect, challenge ideas and make meanings, which support engagement in critical literacy. These opportunities for children to express opinions and ask questions are a way to advocate for their own and others’ rights (Luff, Kanyal, Shehu, & Brewis, 2016), contributing both to social justice and creating an equitable learning environment.

Examples of questions

Some examples of questions will be shared and discussed in this section to show how they can be used in purposeful ways to promote engagement in critical literacy. This includes making connections to prior knowledge and experiences; sharing perspectives and reflecting on ideas in the story to explore possible responses. It is worth noting that the proposed practices are not hierarchical in importance or sequential, but rather implemented according to both the content and storyline of the books, and the children’s sociocultural context. This includes taking into consideration factors such as families’ beliefs and values, development appropriateness, and the intended outcomes for the children.

Prompts for making connections to prior knowledge and experiences

What happened in the story? What does this [picture/word] say? How do you know? Have you [done/seen] this before? Tell me about it. Can you remember …? What happened? How is [the character] feeling? Why is [the character] feeling this way?

When teachers actively support children to make meaning through connecting to their prior knowledge experiences, children are supported in developing a critical stance towards text (Mackey & de Vocht-van Alphen, 2016). When being read a story about Alfie and the Big Boys (Hughes, 2007) a group of five-year-old children were asked, “Why is Ian [a big boy in the story] not talking to the little kids?” Although the story portrays Ian as happy playing with another little girl, the children offered their own interpretations suggesting; “He may be angry at them” and “He doesn’t know their names”. This story was purposefully selected for the children who had just transitioned from early childhood centres into new entrant classrooms. By eliciting the children’s voice, the teacher was able to understand the challenges the children were facing and the thoughts that were guiding their actions, and was able to introduce strategies to support their sense of belonging and social competence (Law, 2012).

Books such as Mum and Dad Glue (Gray, 2009) and No Ordinary Family (Krause, 2013) convey messages around the different family structures; the first a narrative about a child’s feelings over his parents’ separation and the latter looking at children’s experience of being in a blended family. These books resonate with many children nowadays and present opportunities for teachers to use them as a tool to support children to help clarify misconceptions or provide reassurance for the anxiety they may be feeling. Questions like “Who do you live with now?”, “What do you do when you are with [Mum/Dad]?” or “Do you like sharing your room with your [half/step siblings]? Why?” provokes children to talk about their own experience or opinions which could then lead to further discussions around fairness and family diversity.

Prompts for sharing perspectives

What do you think [the character] could do? What else? What is going to happen next? Are these pictures the same or different? Teachers need to also allow time for children to respond to images before starting to read. Prompt or model thinking out loud if needed, for example: “What can you see?”, “I wonder how [the character] is feeling?”

Empowerment is one of the principles that drives the vision for children at the heart of Te Whāriki (MoE, 2017). Effective questioning and giving time for children to respond to what they see, can empower them to create stories in different ways according to their own views and interests. Questions like “What is going to happen next?” prompt children to make predictions about the story and form questions based on their knowledge of the world, understanding that their voice and opinion are valid while realising that others can bring in their own perspectives too.

It is equally important that teachers take time to listen to children, allowing them to share their ideas and ask questions, thereby recognising that they are active participants (Peters & Kelly, 2011). This facilitation of social interactions amongst children prompts them to be open-minded and become aware that people give meaning to texts in different ways (Bailin, Case, Coombs, & Daniels, 2010). This is crucial to critical literacy as perspective-taking and empathy are two social competencies that enhance the attributes of sharing and caring (Robertson, 2018). The digital book Oat the Goat (MoE, 2018) is a great teaching tool for encouraging perspective-taking and empathy as children are given opportunities to make choices and justify their opinions. This can be done by asking “What would you do if you were the Goat? Why?” in the scene where Amos, a mossy, green, hairy creature, was laughed at and criticised by a few sheep for how he looks, calling him “a weirdo” and “mossy head”. Further probing concepts of bullying or discrimination can be done by modelling thinking out loud, “Look at Amos, I wonder how he’s feeling when the sheep laugh at him?” With this, children are encouraged to reflect on the situation, share their perspectives, while respecting that their peers may hold differing views from their own.

Wordless picture books like Bee & Me (Jay, 2016) is one that facilitates children to use their own unique imagination and prior knowledge to fill in the details, taking away different meanings with them (Law & Zheng, 2013). Throughout the text, children are presented with images that leave them room to question or add their own voice to it. Simple probing questions like, “What can you see?”, “What do you think this picture means?” encourage children’s voice and input, which supports the strand of contribution in Te Whāriki (MoE, 2017) where children become increasingly capable of “recognising and appreciating their own ability to learn” (p. 37).

Prompts to reflect on concepts and exploring actions

What would happen if…? Is it good or bad to…? Is it ok if/when…? Why or why not? What would you do/feel if you are [a character]? Who do you like in this story? Why?

It is imperative that children recognise how a particular text may affect their feelings, thoughts, or perceptions in order to be active citizens who are able to think about their responsibilities in the environment they live in. The Selfish Crocodile (Charles, 2010) illustrates a self-centered crocodile who initially refuses to share the forest with the other animals but eventually becomes friendly and considerate after being helped by a mouse. Children can be invited to share their thoughts through questions such as “Is it ok to have the whole space to yourself? What will happen if you do that?” or “What can you say to your friends so they play with you?” These questions prompt children to use their comprehension of the story and the images to reflect on issues of equality and inclusion and through a collaborative reading experience, they can develop an awareness of certain positive behaviours in life that promotes social justice.

One example from the book Zoobots (Whatley & Whatley, 2010) shows how children are supported to not only identify key message of the story but also further reflect on their own thoughts about friendship.

Teacher: What do you think this story is about? Child A: Making friends . Teacher: What about making friends? Child A: Like they build a friend and that‘s kind of like people finding friends. At this time, another child, B, added his own point of view about friendship. Child B: You cannot have too many friends. Teacher: But was it ok they (the characters) found another friend? Child B: Yes. Teacher: Did it matter in the end what the friend looked like? Child B: No. (Law, 2012, p. 64)

In this example, the teacher ensures that the main concept in the story connects to the children’s lives and that Child B can form an inclusive view about making friends. Similarly, other social justice issues such as bullying and discrimination can be explored by using books such as Isaac and His Amazing Asperger Superpowers (Walsh, 2016) or Julian Is A Mermaid (Love, 2018) engaging children in further discussions around the message, leading to prompts that support their application to their own experiences. The first book illustrates how a child with Asperger’s syndrome would perceive the world and the second book is about a boy who wants to be a mermaid. Questions such as “If you are Isaac’s [character] friend, what will you do to play with him?” or “Is it okay for boys to play with dolls?” and “Is it okay for girls to be firemen?” can foster positive attitudes in children to matters relevant to their lives and with the growing awareness of equality, empower them to act with kindness and empathy.

Critical literacy in early childhood education is warranted with the increased complexity and diversity of society and the need for children to be socially responsible individuals who can take the lead and make good decisions and actions in life. Critical literacy helps address real life issues through empowering children to make connections, share perspectives, and reflect on ideas and explore possible responses. This article advocates for the purposeful use of questioning in promoting critical literacy through picture book reading experiences, where there is a balance between teacher questioning and children questioning to promote critical, creative, and reflective conversations. A sociocultural approach has been applied, where children’s prior knowledge and experience are activated and where picture book choices are relevant to matters relating to their lives in order for the learning to be meaningful and impactful. This can be practiced by having reflective teachers who are critical and conscious of their own beliefs, assumptions, and biases, and an environment that ensures children’s views and feelings are valued and that their voices are listened to.

- Bailin, S., Case, R., Coombs, J. R., & Daniels, L. B. (2010). Conceptualizing critical thinking. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 31( 3), 285-302.

- Bell, J. C., & Morris, J. (2011). Don’t panic Annika . Australia: Koala Book Company.

- Charles, F. (2010). The selfish crocodile. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Comber, B. (1999, November). Critical literacies: Negotiating powerful and pleasurable curricula - How do we foster critical literacy through English language arts? Paper presented at the National Council of Teachers of English 89th Annual Convention, Denver, Colorado. Retrieved from https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED444183

- Education Review Office (2017). Extending their language - Expanding their world: Children’s oral language (birth - 8 years). Wellington, New Zealand: Author.

- Gray, K. (2009). Mum and Dad glue . London: Hachette Children’s Group.

- Hawkins, K. (2014). Teaching for social justice, social responsibility and social inclusion: a respectful pedagogy for twenty-first century early childhood education. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 22 (5), 723-738.

- Helmling, L. & Reid, R. (2017). Unpacking picture books: Space for complexity? Early Education, Vol. 61, 14-17.

- Hughes, S. (2007). Alfie and the big boys . United Kingdom: Random House.

- Janks, H. (2000). Domination, access, diversity and design: A synthesis for critical literacy education. Educational Review, 52 (2), 175-186.

- Jay, A. (2016). Bee & me. Denver: Accord Publishing.

- Kim, S. J. (2016). Opening up spaces for early critical literacy: Korean kindergarteners exploring diversity through multicultural picture books. Australian Journal of Language and Literacy, 39 (2), 176-187.

- Krause, U. (2013). No ordinary family . Germany: North-South Books.

- Law, S. -Y. (2012). Effective strategies for teaching young children critical thinking through picture book reading: A case study in the New Zealand context (Unpublished master’s thesis). Victoria University of Wellington, Wellington, New Zealand.

- Law, S. –Y. & Zheng, L. (2013). Children’s comprehension of visual texts: A study conducted based on 5-6 year-old children’s oral narration of picture books. Published in Zao³ Qi¹ Jiao⁴ Yu⁴ (Jiao⁴ Ke¹ Yan² Ban³), China. Retrieved from https://ishare.iask.sina.com.cn/f/335ceALmHca.html

- Levy, R. (2016). A historical reflection on literacy, gender and opportunity: implications for the teaching of literacy in early childhood education. International Journal of Early Years Education, 24 (3), 279-293.

- Lewison, M., Flint, A. S., & Van Sluys, K. (2002). Taking on critical literacy: The journey of newcomers and novices. Language Arts, 79 (5), 382-392.

- Love, J. (2018). Julian is a mermaid. Massachusetts: Candlewick Press.

- Luff, P., Kanyal, M., Shehu, M. & Brewis, N. (2016). Educating the youngest citizens - possibilities for early childhood education and care, in England. Journal for Critical Education Policy Studies, 14 (3), 197-219.

- Mackey, G. & de Vocht-van Alphen, L. (2016). Teachers explore how to support young children’s agency for social justice. International Journal of Early Childhood, 48 (3), 353-367.

- Mankiw, S. & Strasser, J. (2013). Tender topics: Exploring sensitive issues with pre-K through first grade children through read-alouds. Young Children, 68( 1), 84-89.

- Ministry of Education. (2003). Effective literacy practice: in Years 1 to 4. Wellington: Learning Media Ltd.

- Ministry of Education. (2009). Learning Through Talk: Oral Language in Years 1 to 3 . Wellington: Learning Media Ltd.

- Ministry of Education. (2017). Te Whāriki: He Whāriki Mātauranga mō ngā Mokopuna o Aotearoa: Early Childhood Curriculum. Wellington: Learning Media Ltd.

- Ministry of Education. (2018). Oat the goat. Retrieved from https://www.bullyingfree.nz/parents-and-whanau/oat-the-goat/

- Norris, K., Lucas, L., & Prudhoe, C. (2012). Examining critical lteracy: Preparing preservice teachers to use critical lteracy in the early childhood classroom. Multicultural Education, 19 (2), 59–62.