Overview of Education in the Philippines

- Later version available View entry history

- First Online: 24 December 2021

Cite this chapter

- Lorraine Pe Symaco 3 &

- Marie Therese A. P. Bustos 4

Part of the book series: Springer International Handbooks of Education ((SIHE))

252 Accesses

The Philippines has embarked on significant education reforms for the past three decades to raise the quality of education at all levels and address inclusion and equity issues. The country’s AmBisyon Natin 2040 or the national vision for a prosperous and healthy society by 2040 is premised on education’s role in developing human capital through quality lifelong learning opportunities. Education governance is handled by three government agencies overseeing the broad education sector of the country. At the same time, regional initiatives relating to ASEAN commitments are also witnessed in the sector. However, despite the mentioned education reforms and initiatives, the education system remains beset by challenges. This chapter will give readers an overview of the education system of the Philippines through an account of its historical context and its main providers and programs. Key reforms and issues within the sector are also discussed.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Institutional subscriptions

Batalla EVC, Thompson MR (2018) Introduction. In: Thompson MR, Batalla EVC (eds) Routledge handbook of the contemporary Philippines. Routledge, New York, pp 1–13

Google Scholar

Bautista MB, Bernardo AB, Ocampo D (2008) When reforms don’t transform: reflections on institutional reforms in the Department of Education. Available at: https://pssc.org.ph/wp-content/pssc-archives/Works/Maria%20Cynthia%20Rose%20Bautista/When_Reforms_Don_t_Transform.pdf . Accessed 29 Jan 2021

Behlert B, Diekjobst R, Felgentreff C, Manandhar T, Mucke P, Pries L, et al (2019) World Risk Report 2020. Available at: https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/WorldRiskReport-2020.pdf . Accessed 29 Jan 2021

Bustos MT (2019) Special educational needs and disabilities in Secondary Education (Philippines). Bloomsbury Education and Childhood Studies. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781350995932.0023

CHED (2005) CHED memorandum order 1: revised policies and guidelines on voluntary accreditation in aid of quality and excellence in higher education. CHED, Pasig

CHED (2008) Manual of regulations for private higher education. CHED, Pasig

CHED (2013) CHED Memoradum Order 20: General Education Curriculum: Holistic Understandings, Intellectual and Civic Cometencies. CHED, Pasig

CHED (2019a) AQRF referencing report of the Philippines 2019. CHED, Quezon City

CHED (2019b) CHED Memorandum Order 3 Extension of the Validity Period of Designated Centres of Excellence (COEs) and Centres of Developments (CODs) for Various Disciplines

CHED (2019c) Professional regulation commission national passing average 2014–2018. Retrieved from https://ched.gov.ph/wp-content/uploads/2004_2018-PRC-natl-pass-rate-from-2393-heis-as-of-18June2019.pdf

CHED (n.d.-a). Statistics. Available at: https://ched.gov.ph/statistics/ . Accessed 30 Jan 2021

CHED (n.d.-b) About CHED. Available at: http://ched.gov.ph . Accessed 10 Aug 2020

CHED (n.d.-c) Expanded Tertiary Education Equivalency and Accreditation (ETEEAP). Available at: https://ched.gov.ph/expanded-tertiary-education-equivalency-accreditationeteeap/ . Accessed 11 Sept 2020

CHED (n.d.-d) Higher education data and indicators: AY 2009–10 to AY 2019–20. Available at: https://ched.gov.ph/wp-content/uploads/Higher-Education-Data-and-Indicators-AY-2009-10-to-AY-2019-20.pdf . Accessed 29 Jan 2021

CHED (n.d.-e) CHED K to 12 transition program. Retrieved from https://ched.gov.ph/k-12-project-management-unit/ . Accessed 1 Mar 2021

Cohen C, Werker E (2008) The political economy of “natural” disasters. J Confl Resolut 52(6):795–819

Article Google Scholar

Department of Budget (DBM) (2020) PRRD signs the P4.506 Trillion National Budget for FY 2021. Available at: https://www.dbm.gov.ph/index.php/secretary-s-corner/press-releases/list-of-press-releases/1778-prrd-signs-the-p4-506-trillion-national-budget-for-fy-2021#:~:text=President%20Rodrigo%20Roa%20Duterte%20today,to%20the%20COVID%2D19%20pandemic . Accessed 11 Feb 2021

Department of Interior and Local Government (DILG) (2020) Regional summary number of Provinces, Cities, Municipalities and Barangays, by region as of September 30, 2020. Retrieved from https://www.dilg.gov.ph/PDF_File/factsfigures/dilg-facts-figures-2020124_c3876744b4.pdf . Accessed 1 Mar 2021

DepEd (2005) Basic Education Sector Reform Agenda (2006–2010). Available at: http://www.fnf.org.ph/downloadables/Basic%20Education%20Sector%20Reform%20Agenda.pdf . Accessed 29 Jan 2021

DepEd (2010) Implementation of the basic Education Madrasah Programs for Muslim Out-of School Youth and Adults, Department Order 57, s. 2010

DepEd (2012) Adoption of the unique learner reference number, Department Order 22, S. 2012

DepEd (2017) Policy guidelines on Madrasah Education in the K to 12 Basic Education Program, Department Order 41, s. 2017

DepEd (2019) Policy guidelines on the K to 12 Basic Education Program, Department Order 21, s. 2019

DepEd (2020) Major projects, programs & activities status of implementation. Available at: https://www.deped.gov.ph/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/List-of-Programs-and-Project-Implementation-Status.Final_.TS_.pdf . Accessed 29 Jan 2021

Department of Education (DepEd) (n.d.-a) Historical perspective of the Philippines Educational System. Available at: https://www.deped.gov.ph/about-deped/history/ . Accessed 11 Sept 2020

DepEd (n.d.-b) Entollment Statistics. DepEd, Pasig.

Early Childhood Care and Development (ECCD) (n.d.) The National Child Development Centre. Available at: https://eccdcouncil.gov.ph/ncdc.html . Accessed 9 Jan 2021

ECCD Council (n.d.) Early Childhood Care 2018 Annual Report. Pasig, ECCD Council, Metro Manila

ECCD Council/UNICEF (n.d.) The National Early Learning Framework of the Philippines . Available at: https://eccdcouncil.gov.ph/downloadables/NELF.pdf . Accessed 28 June 2020

GoP (1990) Barangay-Level Total Development and Protection of Children Act. Republic Act 6972

GoP (1994a) Higher Education Act. Republic Act 7722

GoP (1994b) TESDA Act. Republic Act 7796

GoP (1998) Expanded Government Assistance to Students and Teachers in Private Education Act, Republic Act 8545

GoP (2000) Institutionalizing the System of National Coordination, Assessment, Planning and Monitoring of the Entire Educational System, Executive Order 273, s. 2000

GoP (2001) Governance of Basic Education Act of 2001, Republic Act 9155. Available at: https://www.officialgazette.gov.ph/2001/08/11/republic-act-no-9155/ . Accessed 29 Jan 2021

GoP (2002) Early Childhood Care and Development Act. Republic Act 8980

GoP (2007) Amending Executive Order No. 273 (Series of 2000) and Mandating a Presidential Assistant to Assess, Plan and Monitor the Entire Educational System, Executive Order 632, S. 2007

GoP (2013) Enhanced Basic Education Act. Republic Act 10533

GoP (2014) Ladderized Education Act. Republic Act 10647

GoP (2016) Executive Order No. 5, s. 2016. Approving and Adopting the Twenty-five-year long term vision entitled Ambisyon Natin 2040 as guide for development planning

GoP (2018a) PQF Act. Republic Act 10986

GoP (2018b) Organic Law for the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao Act. Republic Act 11054

GoP (2018c) Safe Spaces Act. Republic Act 11313

GoP (2019a) Transnational Higher Education Act. Republic Act 11448

GoP (2019b) Executive Order No. 100, s. 2019. Institutionalising the Diversity and Inclusion Program, Creating an Inter-Agency Committee on Diversity and Inclusion, and for Other Purposes

GoP (2020) Alternative Learning Systems Act . Republic Act 11510

Government of the Philippines (1987) 1987 Constitution of the Republic of the Philippines

GOVPH (n.d.) About the Philippines. Available at: https://www.gov.ph/about-the-philippines . Accessed 29 Jan 2021

Malipot (2019) DepEd in 2019: the quest for quality education continues. Available at: https://mb.com.ph/2019/12/29/year-end-report-deped-in-2019-the-quest-for-quality-education-continues/ (Manila Bulletin). Accessed 9 Jan 2021

Mendoza DJ, Thompson MR (2018) Congress: separate but not equal. In: Thompson MR, Batalla EVC (eds) Routledge handbook of the contemporary Philippines. Routledge, New York, pp 107–117

Chapter Google Scholar

National Economic and Development Authority (NEDA) (2017) Philippine Development Plan 2017–2022. Available at: http://pdp.neda.gov.ph/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/PDP-2017-2022-10-03-2017.pdf . Accessed 29 Jan 2021

OECD (2019) Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) Result from PISA 2018 (Philippines). Available at: https://www.oecd.org/pisa/publications/PISA2018_CN_PHL.pdf . Accessed 11 Sept 2020

Paqueo V, Orbeta A Jr (2019) Gender equity in education: helping the boys catch up. Philippine Institute for Development Studies, Quezon City

Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA) (2020) SGD watch Philippines. Available at: https://psa.gov.ph/sites/default/files/phdsd/PH_SDGWatch_Goal04.pdf . Accessed 9 Jan 2021

Philippines Qualifications Framework (PQF) (n.d.-a) The Philippine Education and Training System. Available at: https://pqf.gov.ph/Home/Details/16 . Accessed 9 Jan 2021

PQF (n.d.-b) Philippine Qualifications Framework. Available at: https://pqf.gov.ph/Home/Details/7 . Accessed 9 Jan 2021

Professional Regulations Commission (PRC) (2019) March 2019 LET teachers board exam list of passers. Available at: https://www.prcboardnews.com/2019/04/official-results-march-2019-let-teachers-board-exam-list-of-passers.html . Accessed 11 Sept 2020

PSA (2019a) 2019 Philippines statistical yearbook. PSA, Quezon City

PSA (2019b) Proportion of Poor Filipinos in ARMM registered at 63.0 percent in the First Semester of 2018. Available at: http://rssoarmm.psa.gov.ph/sites/default/files/001%20Proportion%20of%20Poor%20Filipinos%20in%20ARMM%20registered%20at%2063.0%20percent%20in%20the%20First%20Semester%20of%202018.pdf . Accessed 11 Sept 2020

PSA (n.d.) List of Institutions with Ladderized Program under EO 358, July 2006 – December 31, 2007. Available at: https://psa.gov.ph/classification/psced/downloads/ladderizedprograms.pdf . Accessed 29 Jan 2021

Schwab K (2019) The global competitiveness report 2020. Available at: http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_TheGlobalCompetitivenessReport2019.pdf . Accessed 29 Jan 2021

Senate of the Philippines (SoP) (2007) Senate P.S. Resolution No.96 Resolution directing the committee on education, arts and culture and committee on constitutional amendments, revisions of codes and laws to conduct a joint inquiry, in aid of legislation, into the implementation of executive order no. 632 abolishing the national coordinating council for education (NCCE) and mandating a presidential assistant to exercise its functions

Syjuco A (n.d.) The Philippine Technical Vocational Education and Training (TVET) System . Available at: https://www.tesda.gov.ph/uploads/file/Phil%20TVET%20system%20-%20syjuco.pdf . Accessed 11 Sept 2020

Symaco LP (2013) Geographies of social exclusion: education access in the Philippines. Comp Educ 49(3):361–373. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050068.2013.803784

Symaco, TLP (2019) Special educational needs and disabilities in primary education (Philippines). Bloomsbury Education and Childhood Studies. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781474209472.0025

Technical Education and Skills Development Authority (TESDA) (2007) TESDA circular 2007. Available at: https://tesda.gov.ph/uploads/file/issuances/omnibus_guide_2007.pdf . Accessed 10 Aug 2020

TESDA (2012) Philippines qualification framework. Available at: http://www.tesda.gov.ph/uploads/File/policybrief2013/PB%20Philippine%20Qualification%20Framework.pdf . Accessed 11 Sept 2020

TESDA (2020a) Philippine TVET statistics 2017–2019 report. Available at: https://www.tesda.gov.ph/Uploads/File/Planning2020/TVETStats/20.12.03_BLUE_TVET-Statistics_2017-2019_Final-min.pdf . Accessed 29 Jan 2021

TESDA (2020b) TVET statistics 2020 4th quarter report. TESDA, Taguig

TESDA (2020c) 2020 TVET statistics annual report. TESDA, Taguig

TESDA (n.d.-a) TVET programmes. Available at: https://www.tesda.gov.ph/About/TESDA/24 . Accessed 9 Jan 2021

TESDA (n.d.-b) National Technical Education and Skills Development Plan 2018–2022. Available at: https://www.tesda.gov.ph/About/TESDA/47 . Accessed 9 Jan 2021

TESDA (n.d.-c) Competency standards development. Available at: https://www.tesda.gov.ph/About/TESDA/85 . Accessed 9 Jan 2021

TESDA (n.d.-d) Assessment and certification. Available at: https://www.tesda.gov.ph/About/TESDA/25 . Accessed 9 Jan 2021

Timberman G (2018) Persistent poverty and elite-dominated policymaking. In: Thompson MR, Batalla EVC (eds) Routledge handbook of the contemporary Philippines. Routledge, New York, pp 293–306

TIMSS & PIRLS International Study Center (n.d.) TIMSS 2019 international results in Mathematics and Science. Available at: https://timss2019.org/reports/ . Accessed 9 Jan 2021

UNESCO Institute of Statistics (2020) COVID-19 A global crisis for teaching and learning. Available at: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000373233 . Accessed 11 Sept 2020

UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UNESCO UIS) (2021) Philippines education and literacy. http://uis.unesco.org/en/country/ph?theme=education-and-literacy . Accessed 18 Feb 2021

Valencia C (2019) Companies still hesitant to hire K12 graduates. Available at: https://www.philstar.com/business/business-as-usual/2019/09/30/1955967/companies-still-hesitant-hire-k-12-graduates . Accessed 28 June 2020

Worldometer (n.d.) Philippines demographics. https://www.worldometers.info/demographics/philippines-demographics/ . Accessed 27 Sept 2021

Useful Websites

Ambisyon Natin 2040 . http://2040.neda.gov.ph/

Commission on Higher Education (CHED) https://ched.gov.ph/

Department of Education (DepED). https://www.deped.gov.ph/

ECCD Council of the Philippines (ECCD Council). https://eccdcouncil.gov.ph/

National Council on Disability Affairs (NCDA). https://www.ncda.gov.ph/

Technical Education and Skills Development Authority (TESDA) https://www.tesda.gov.ph/

UNESCO Institute for Statistics Philippines profile. http://uis.unesco.org/en/country/ph?theme=education-and-literacy

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

College of Education, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China

Lorraine Pe Symaco

College of Education, University of the Philippines, Quezon City, Philippines

Marie Therese A. P. Bustos

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Lorraine Pe Symaco .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

School of education, Southern Cross University, Lismore, NSW, Australia

Martin Hayden

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this chapter

Symaco, L.P., Bustos, M.T.A.P. (2022). Overview of Education in the Philippines. In: Symaco, L.P., Hayden, M. (eds) International Handbook on Education in South East Asia. Springer International Handbooks of Education. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-8136-3_1-1

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-8136-3_1-1

Received : 02 November 2021

Accepted : 02 November 2021

Published : 24 December 2021

Publisher Name : Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN : 978-981-16-8135-6

Online ISBN : 978-981-16-8136-3

eBook Packages : Education Reference Module Humanities and Social Sciences Reference Module Education

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

Chapter history

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-8136-3_1-3

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-8136-3_1-2

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-8136-3_1-1

- Find a journal

- Track your research

UNESCO and DepEd launch the 2020 Global Education Monitoring Report in the Philippines

MANILA, 25 November 2020. Along with government officials, international aid agencies, education and humanitarian experts, policymakers, teachers and learners, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) and the Department of Education (DepEd) launched the 2020 Global Education Monitoring (GEM) Report on 25 November 2020 virtually.

With the theme “Inclusion and education: All means All,” the national launch was organized to increase awareness of the Report’s messages and recommendations on inclusion in education with a wider education community, with those working on humanitarian responses, and with government officials and policymakers. The event was broadcasted live on the official Facebook of UNESCO Jakarta and the Philippines’ Department of Education.

As part of its progress towards achieving the Sustainable Development Goal 4 (SDG 4)and its targets, the 2020 GEM Report ( https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000373721 ) provides an in-depth analysis of key factors in exclusion of learners in education systems worldwide, such as background, identity and ability (i.e. gender, age, location, poverty, disability, ethnicity, indigeneity, language, religion, migration or displacement status, sexual orientation or gender identity expression, incarceration, beliefs and attitudes).

One of the numerous examples highlighted in the report is the gender-responsive basic education policy created by DepEd. The policy calls for an end to discrimination based on gender, sexual orientation, and gender identity by defining ways for education administrators and school leaders such as improving curricula and teacher education programmes with the content on bullying, discrimination, gender, sexuality and human rights.

The Report also identifies the heightening of exclusion during the COVID-19 pandemic, where it has shown that about 40% of low and lower-middle income countries have not supported disadvantaged learners during temporary school shutdown. The event featured speeches and presentations from experts on inclusion from both government and non-governmental organizations, policy makers and practitioners, including a message from UNESCO’s Global Champion of Inclusive Education, Ms Brina Kei Maxino, and performances by the world-renowned and 2009 UNESCO Artist for Peace, the Philippine Madrigal Singers.

The highlight of the event was the live discussion between DepEd Secretary, Professor Emeritus Leonor Magtolis-Briones, and the Director of UNESCO Jakarta, Dr Shahbaz Khan, as they explored the findings of the report and deliberated on issues such as inclusion and education and its implementation; adjustment on the school policies during Covid-19; a horizontal collaboration between government and non-government stakeholders; education budget and spending; grants for students; and, social programs to support education.

Alongside today’s publication, UNESCO GEM Report team has also launched a new website called Profiles Enhancing Education Reviews (PEER) that contains information on laws and policies concerning inclusion in education for every country in the world. According to UNESCO, PEER shows that although many countries still practice education segregation, which reinforces stereotyping, discrimination and alienation, some countries like the Philippines have already crafted education policies strong on inclusiveness that target vulnerable groups.

The 2020 Global Education Monitoring (GEM) Report urges countries to focus on those left behind as schools reopen to foster more resilient and equal societies.

- Global Education Monitoring Report

Related items

- Education for sustainable development

- Country page: Philippines

- UNESCO Office in Jakarta and Regional Bureau for Science

- SDG: SDG 4 - Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all

- See more add

This article is related to the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals .

Other recent news

Overview of the Structure of the Education System in the Philippines

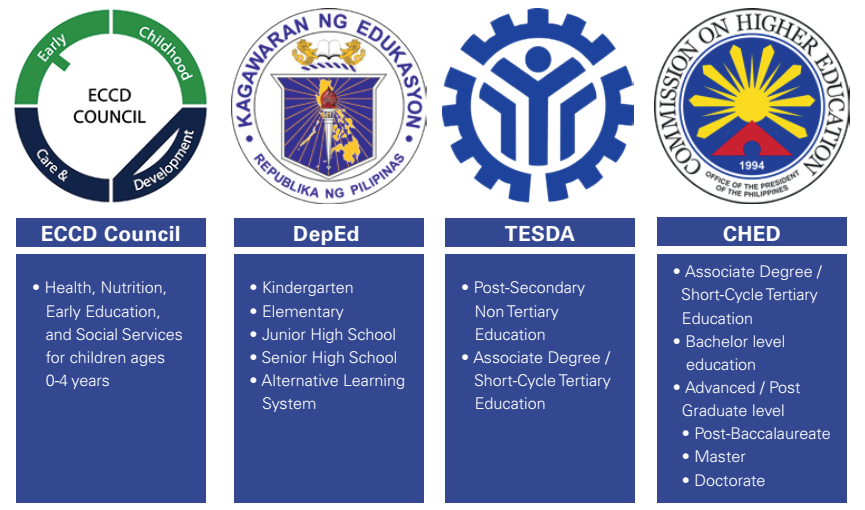

The Philippine education system includes Early Childhood Care and Development (ECCD), Basic Education, Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET), and Higher Education.

The Department of Education (DepEd) is responsible for basic education, ECCD Council for ECCD, the Technical Education and Skills Development Authority (TESDA) for post-secondary, technical and vocational education, and the Commission on Higher Education (CHED) for higher education.

Figure 1: Levels of Philippine Education

Early childhood programs (i.e., daycare centers) are governed by the ECCD Council, an attached agency of the Department of Education. The Early Years Act of 2013 mandated the Early Childhood Care and Development (ECCD) Council to act as the primary agency supporting the government’s ECCD programs that cover health, nutrition, early education, and social services for children ages 0-4 years.

It is responsible for developing policies and programs, providing technical assistance and support to ECCD service providers, and monitoring ECCD service benefits and outcomes.

Most daycare centers are projects sponsored by local government units (LGUs) in coordination with the Department of Social Work and Development (DSWD).

The Department of Education (DepEd) governs Basic Education Schools. TESDA governs technical-vocational schools not run by DepEd and offers certification certificates. CHED governs tertiary-level institutions offering university and college courses.

The Department of Education (DepEd), CHED, and TESDA are co-equal in rank, and their heads all have cabinet-level rank. The heads of the three agencies are represented in the NEDA Social Development Committee and are members of the Philippine Qualifications Framework (PQF) Task Force. Collaborations across the three education agencies are ad hoc and depend on the urgency of issues.

In addition, two agencies were also created to focus on culture and sports: National Commission for Culture and the Arts (NCCA) and the Philippine Sports Commission (PSC), respectively.

In November 2019, DepEd created/constituted the Philippines Basic Education Forum, where representatives from the three agencies and other stakeholders participate. The Forum attempts to meet quarterly to discuss DepEd and other education initiatives.

Table of Contents

Formal Education in the Philippines

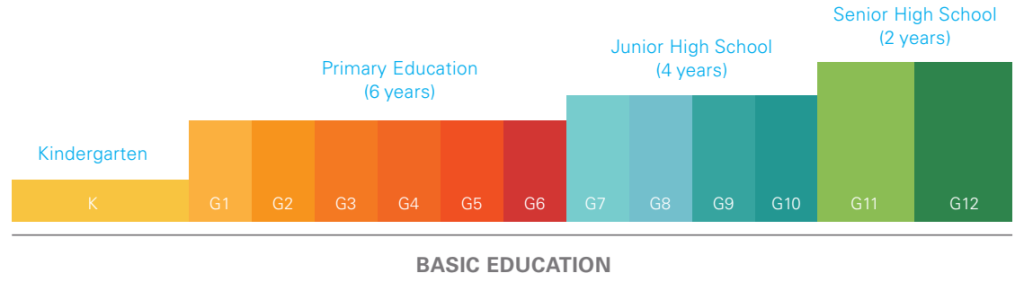

The Enhanced Basic Education Act of 2013 established one year of Kindergarten and introduced Grades 11 and 12 to high school education (RA 10533, May 15, 2013).

The program covers Kindergarten and 12 years of basic education (six years of primary education, four years of Junior High School [JHS], and two years of Senior High School [SHS]). During which students should have sufficient time for the mastery of concepts and skills, develop as lifelong learners, and prepare for tertiary education, middle-level skills development, employment, and entrepreneurship.

Figure 2: The K to 12 Reform

The K to 12 is grouped into three levels: elementary school (Kindergarten-Grade 6), Junior High School (Grades 7-10), and Senior High School (Grades 11-12).

They may also be grouped into four key stages: first key stage (Lower Primary: Kindergarten – Grade 3), second key stage (Upper Primary: Grades 4-6), third key stage (Junior High School: Grades 7-10) and fourth key stage (Senior High School: Grades 11-12).

Since SY 2012-2013, the K to 12 Basic Education Curriculum has been implemented, starting with the roll-out of Grades 1 and 7 for public and private schools.

Kindergarten to Grade 3 (Primary School)

Every Filipino child now has access to early childhood education through Universal Kindergarten. Children start schooling at five years of age and are given the means to adjust to formal education slowly.

Adopting the UNESCO belief that children can learn best through their first language, Mother Tongue (MT) instruction has been adopted by the Department of Education (DepEd) as the first language of instruction in the first four years of formal schooling (K to Grade 3).

Nineteen Mother Tongue languages are being used: Bahasa Sug, Bikol, Cebuano, Chabacano, Hiligaynon, Iloko, Kapampangan, Maguindanaoan, Meranao, Pangasinense, Tagalog, Waray, Ybanag, Ivatan, Sambal, Akianon, Kinaray-a, Yakan, and Surigaonon.

Aside from the Mother Tongue, English and Filipino are taught as subjects starting in Grade 3, focusing on oral fluency. From Grades 4 to 6, English and Filipino are gradually introduced as languages of instruction. Both become primary languages of instruction in Junior High School (JHS) and Senior High School (SHS).

Kindergarten was made mandatory and added to the Basic Education curriculum through the Kindergarten Act (RA 10157, January 20, 2012) to effectively promote physical, social, intellectual, and emotional skills stimulation and values formation to sufficiently prepare them for formal elementary schooling. Children can start entering Kindergarten at age 5.

Grades 4 to 6 (Middle School)

Upper Primary is the continuation of Lower Primary expanding simple literacy and numeracy to functional literacy, developing higher order thinking skills. The purpose of which is to develop knowledge and skills, attitudes, and values essential to personal development and necessary for living in and contributing to a developing and changing environment.

The basic learning areas include Filipino, English, Science, Mathematics, History Geography and Civics (Sibika), Edukasyonng Pantahanan at Pangkabuhayan (work education), and Music and Art.

Grades 7 to 10 (Junior High School)

Junior High School (JHS) is discipline-based. Subjects covered are Mathematics; Science and Technology; English; and Filipino. Other subjects are Makabayan (History, Economics); Technology and Livelihood; Music, Art, Physical Education, and Health; and Values Education.

Grades 11 to 12 (Senior High School)

In June 2016, DepEd launched Senior High School (SHS) , a major social undertaking that had many issues and challenges at the beginning. These included

- teacher training,

- availability of materials,

- quantity and quality of schools offering SHS,

- students selection of appropriate SHS tracks, and

- societal acceptance of the possible benefits of the program.

Finishing SHS allows the student to access TESDA programs, enter college/university or join the world of work with more knowledge and skills.

SHS is two years of specialized upper secondary education during which students should have sufficient time for the mastery of concepts and skills to develop as lifelong learners and to prepare for tertiary education, middle-level skills development, or employment .

In Senior High School, students may choose a specialization based on aptitude, interests, and school capacity. The choice of career track will define the content of the subjects a student will take in Grades 11 and 12.

SHS subjects fall under either the Core Curriculum or specific Tracks. There are seven Learning Areas under the Core Curriculum. Languages, Literature, Communication, Mathematics, Philosophy, Natural Sciences, and Social Sciences.

Current content from some General Education subjects is embedded in the SHS curriculum. Each student in Senior High School can choose among four tracks: Academic; Technical-Vocational-Livelihood; Arts and Design; and Sports.

The Academic track includes three strands: Accountancy, Business, and Management (ABM) ; Humanities and Social Sciences (HUMSS) ; and Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics (STEM) .

Students undergo immersion , which may include earn-while-you-learn opportunities to provide them with relevant exposure and experience in their chosen track.

After finishing Grade 10, a student can obtain Certificates of Competency (COC) or a National Certificate Level I (NC I). After finishing a Technical-Vocational-Livelihood track in Grade 12, a student may obtain a National Certificate Level II (NC II), provided he/she passes the competency-based assessment of the Technical Education and Skills Development Authority (TESDA).

Alternative Learning System (ALS)

The Alternative Learning System (ALS) is a parallel learning system that provides a viable alternative to formal education instruction. It encompasses both non-formal and informal sources of knowledge and skills. The ALS curriculum is substantially aligned with the competencies of the formal K to 12 curriculum but is not a mirror of the formal one.

It covers Information, Communication and Technology (ICT) and Life and Career skills and competencies not found in the formal curricula, including competencies in everyday life. It provides opportunities for learners to acquire vocational and technical skills to enhance work readiness and employability.

ALS learners are assessed through a Functional Literacy Test (FLT). The Basic Literacy Program (BLP) aims to eradicate illiteracy among out-of-school children in special cases and adults by developing literacy skills in reading, writing, numeracy, and simple comprehension.

The Accreditation and Equivalency (A&E) Program provides an alternative learning pathway to out-of-school children in special cases and adults who have not completed basic education.

This program allows school dropouts and early school leavers to complete elementary and secondary education outside the formal system. The tests taken at the elementary and junior high school level allow students who pass an equivalency test to transition to the next level.

Private Education in the Philippines

Private schools are legally-registered institutions offering educational services to the public in exchange for fees of whatever amount is agreed between school and community. Private schools are, for the most part, not-for-profit, though there is a minority that is registered as for-profit entities, especially universities and colleges.

Private schools offering education services are regulated by the above three agencies depending on their coverage and level of operations (Basic, Tertiary, or Technical-Vocational Education).

Private schools are privately run entities that have to follow the government curriculum but are free to offer more than the required but not less than the mandated. DepEd issued the “Revised Manual of Regulations for Private Schools in Basic Education” in 2010.

Private schools are privately funded, although a certain number of high schools can apply for and receive government subsidies through the Education Service Contracting (ESC) and the Senior High School Voucher Program (VP).

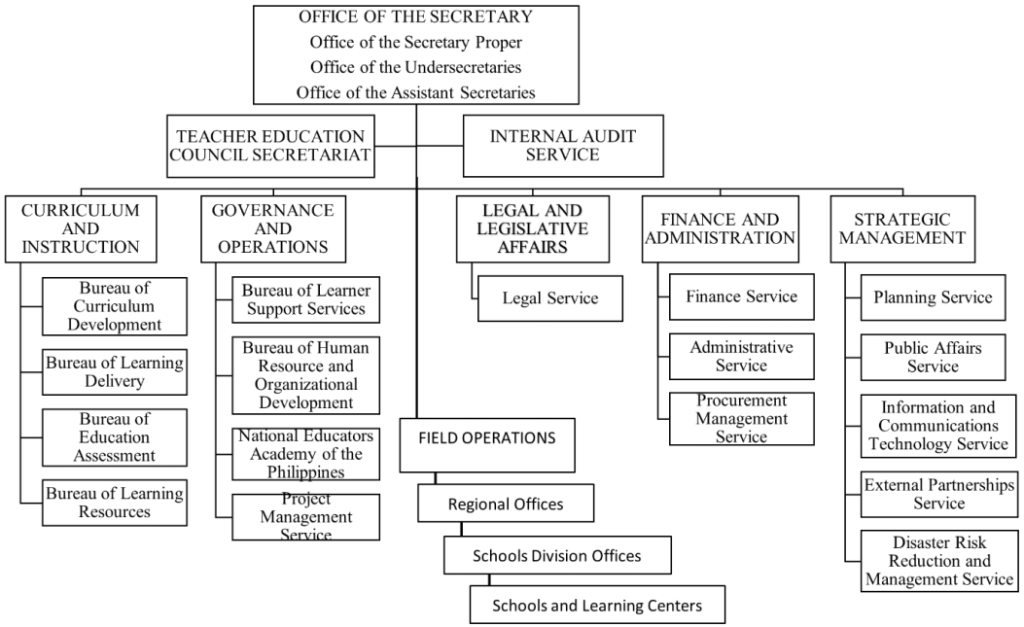

Department of Education (DepEd)

The Department of Education (DepEd) has a Central Office, 17 Regional Offices (including BARMM), and 223 Schools Division Offices. There are school districts throughout the country.

The structure of DepEd is outlined in RA 9155, the law creating the new Department of Education and setting down its organizational structure.

The Central Office has more than 30 offices, bureaus, and services after restructuring in 2016. Regional offices coincide with the administrative regions of the country.

BARMM (Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao) is autonomous and not administratively under the Department of Education. It has its own DepEd.

The Division Offices coincide with provinces, or sometimes it coincides with cities (especially chartered or large cities). Municipalities do not have their own Division Offices and are usually included in provincial Divisions.

Under Divisions are School Districts, which should not be confused with the country’s legislative districts. The Districts are geographic areas usually equivalent to towns or municipalities.

In cities, districts coincide with large barangays or groups of small barangays. The districts’ lowest administrative units of DepEd are schools and Community Learning Centers (CLC).

Figure 3: Department of Education (DepEd) Organizational Structure

Central Office

The Central Office (CO) is responsible for setting standards and translating direction and policy by these.

The Central Office (CO) is organized into:

(a) Bureaus, which address direct education-related matters (e.g., curriculum, learning delivery, education assessment, learning materials, organizational development, and human resource); and

(b) Service units (e.g., budget; accounting; administration; physical facilities; planning; others).

The Central Office (CO) was the subject of a major reorganization in 2015. Some responsibilities are shared by the central office and field offices.

For the most part, operating funds are delivered directly to field units in the spirit of RA 9155 as spelled out in the Direct Release System (DRS) worked out as far back as 2004 by the Department of Budget & Management (DBM), DepEd and the Commission on Audit (COA).

However, large programs continue to be managed at the central office, particularly foreign-funded programs such as the BEST (Basic Education Sector Transformation) program, which ended in 2019.

Other centrally funded programs, such as teacher learning & development (L&D), are managed under the newly-transformed National Educators Academy of the Philippines (NEAP).

NEAP downloads funds to regions and divisions for programs delivered at that level, under national budget issuances or the general/specific provisions of the General Appropriations Act.

Regional Office

Regional Office (RO) roles and responsibilities include translating policy and standards for the operating units, including organizational structure and regional contextualization.

Major challenges include contextualizing policies and programs given differences from region to region. Addressing each region’s different capacities and capabilities is also a significant challenge, given each region’s different socio-economic and demographic realities.

Schools Division Office

Schools Division Office (SDO) roles and responsibilities include describing the accountabilities of the Curriculum Implementation Division and the Schools Governance and Operations Division, as well as the critical role of the School District Supervisors (SDS) in providing technical assistance to schools. Significant challenges include providing equitable technical assistance to schools and learning centers.

District Offices (District Supervisors) assist SDOs at the elementary school level.

Schools are the most basic unit of governance in the system. Within schools are teachers and non-teaching staff. Schools are classified as Elementary Schools, Junior High Schools (JHS), Senior High Schools (SHS), and Integrated schools).

Schools are headed by principals, school heads, or teachers-in-charge (for schools not having the minimum number of teachers to qualify for a principal).

School heads ensure proper school-based management (SBM), stakeholder engagement, and LGU support/partnership.

Community Learning Centers

Community Learning Centers (CLCs) are smaller centers within the system that may deal with special circumstances (multi-grade schooling, special needs, alternative learning). Significant challenges in operating CLCs include addressing difficult situations with limited resources.

Number of Schools and Plantilla in DepEd (Public and Private, Formal Education)

There are a total of 47,188 schools in the Public Schools system (37,628 elementary schools, 1,511 junior high schools, and 216 senior high schools [2020]).

In addition, there are 14,458 schools that are privately run and 271 operated by state universities and colleges (SUC) or local universities and colleges (LUCs).

Table 1: Classification of Schools in the Philippines

| Classification | Public | Private | SUCs/LUCs | PSO | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elementary School | 37,628 | 7,282 | 6 | – | 44,916 |

| Junior High School (JHS) | 1,511 | 267 | 46 | – | 1,824 |

| Senior High School (SHS) | 216 | 1,119 | 85 | – | 1,420 |

| JHS with SHS | 6,391 | 913 | 96 | – | 7,400 |

| Integrated School (Kindergarten to G10) | 961 | 2,004 | 8 | 9 | 2,973 |

| Integrated School (Kindergarten to G12) | 481 | 2,873 | 30 | 20 | 3,384 |

| Total Schools | 47,188 | 14,458 | 271 | 29 | 61,946 |

As of January 2021, DepEd has 965,660 regular employees making it the largest bureaucracy in the Philippine government.

The table below presents the distribution of DepEd employees across all levels of governance. Out of the total number of employees, 88% are teaching staff, and 5% are teaching-related staff . Of all the teaching staff, 46% occupy Teacher 1 positions in elementary and secondary schools.

Over the past two decades, the annual growth rate of the teaching force has been 6.77%. These figures, however, do not include two major categories of personnel: individuals under Contracts of Service or other non-regular engagements, both in schools and administrative offices, and an estimated 8,205 local government-funded teachers in public schools.

Table 2: Teaching and Non-teaching Personnel in DepEd

| Teaching Personnel (including ALS) | Teaching-related Personnel | Non-teaching Personnel | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Central Office | 1,297 | ||

| Regional Offices | 2,097 | ||

| Division Offices | 22,657 | ||

| Senior High School | 67,291 | 4,747 | 9,844 |

| Junior High School | 276,778 | 16,680 | 21,249 |

| Elementary School | 503,396 | 30,441 | 9,183 |

| Subtotal | 847,465 (88%) | 51,868 (5%) | 66,327 (7%) |

Education Stakeholders and Partners

Local government units (lgus).

Local Governments participate in education through the Local School Board (LSB) and the Special Education Fund (SEF) . The LSB controls the use of the SEF, which is generated from the local real estate or property tax (equivalent to 1%).

The SEF can be quite substantial in size for very large LGUs. The SEF for the city of Manila, for example, is the largest in the country at PhP 1 Billion per year.

Most LGU SEF, however, are less than PhP 5 Million a year, reflecting the wide disparity in LGUs. The SEF for 5th and 6th class status (lowest in terms of revenue) would be in the thousands of pesos.

Commission on Higher Education (CHED)

CHED oversees colleges and universities which produce graduates who become teachers in the system. This relationship informs the CHED and aligns the teacher education curriculum with the newly-established Philippine Professional Standards for Teachers (PPST). The relationship, however, is at arm’s length and could be closer, especially in teacher education and development.

Technical Education and Skills Development Authority (TESDA)

TESDA oversees technical and vocational education in the country where there is an overlap with DepEd. The only difference is that Tech-Voc in DepEd is below certification. Certification in DepEd would expand the value of this senior high school offering and should be seriously pursued.

Early Childhood Care and Development Council (ECCD)

The ECCD Council is a government agency mandated by RA 10410 or the Early Years Act (EYA) of 2013 to act as the primary agency supporting the government’s ECCD programs that cover health, nutrition, early education, and social services for children aged 0-4 years. The ECCD Council is an autonomous unit that is attached to DepEd for administrative purposes.

National Government Line Agencies

DepEd works with a range of Philippine line agencies on a wide range of education-related programs.

Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH)

DPWH delivers fully constructed school buildings and other facilities based on mutually-agreed building specifications and plans. These facilities are funded by the DepEd GAA, which is transferred to DPWH for construction.

Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD)

DSWD overseas ECCD (0-4 years old). DSWD also manages the conditional cash transfer program (4Ps), which has an education component.

Department of Health (DOH)

DOH helps DepEd with school health and nutrition programs.

National Economic Development Authority (NEDA)

NEDA works with DepEd to flesh out the basic education section of the Philippine Development Plan and provides assistance in monitoring the programs of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) related to education.

Department of Budget and Management (DBM)

DepEd works with DBM on budget planning, management, and accountability. Over the years, DBM and DepEd (with Commission on Audit concurrence) have designed and set up budget mechanisms to facilitate and make efficient the usage and flow of funds, such as the Direct Release System, where funds for field units no longer had to pass through the central office.

National Nutrition Council (NNC)

The NNC provides valuable data on the state of nutrition of children essential for the planning of school health and school feeding programs.

National Commission on Indigenous People (NCIP)

NCIP provides information and contacts with IP communities, many of which are in GIDA areas and might be the subject of the Last-Mile-Schools program.

Private Sector in Education

Philippine Colleges and Universities and Schools

Philippine universities are grouped into associations that interact with DepEd in different fora depending on the issue. COCOPEA (Coordinating Council of Private Educational Associations) is the umbrella organization with five educational associations with over 2,500 educational and learning institutions among its member schools.

The five associations are:

- Philippine Associations of Colleges and Universities (PACU);

- Catholic Educational Association of the Philippines (CEAP);

- Association of Christian Schools, Colleges and Universities (ASCU);

- Philippine Association of Private Schools, Colleges and Universities (PAPSCU);

- Tech-Voc Schools Association of the Philippines (TVSA).

The Government has a policy of complementarity in education between the private and public sectors (Philippine Constitution of 1987, Article XIV, Section 4), which is currently being tested by specific government programs and policies such as the free tertiary education program in state universities and colleges.

Teacher Education Institutions (Private and Public)

Philippine colleges and universities with teacher education institutions (TEIs) are working with DepEd, notably through the National Educators Academy of the Philippines (NEAP), on teacher education, particularly in-service training. At present, this is limited to Centers of Excellence and Centers of Development, which are identified by CHED designations.

Academic Think Tanks

Academic think tanks are institutions that do academic scholarly work of peer-reviewed quality and publication. Two Philippine education think tanks have worked with DepEd continuously over the past seven years: RCTQ (Regional Center for Teacher Quality at the Philippine Normal University, in partnership with the University of Newcastle, Australia) and ACT-RC (Assessment Curriculum and Technology Research Center at the University of the Philippines, in partnership with the University of Melbourne) through the BEST program.

SEAMEO-Innotech (Southeast Asian Ministers of Education Organization) has done years of collaborative work with DepEd on a wide range of education topics.

Philippine Institute of Development Studies (PIDS) has done studies on education financing, out-of-school youth, senior high school, private education, and education-labor market dynamics.

Donor Community

Major Donors

Two multilateral donors – the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank – have provided loans and technical assistance to DepEd since the 1980s. Bilateral agencies have also extended financial and technical assistance to DepEd, including DFAT (Australia), USAID (USA), JICA (Japan), GIZ (Germany), and KOICA (Korea). The UN system has also extended technical assistance to DepEd, notably through UNICEF.

The relationships and contributions of these foreign donors are coordinated through the Philippine Development Forum.

International NGOs

A number of international NGOs (INGOs) are active in Philippine education. Save the Children Philippines, World Vision, and Oxfam are three of the largest. Many others work at a more local level on very specific interventions in education delivery, child support, health & nutrition, WASH, and others.

Civil Society Organization (CSO) or Non-Governmental Organization (NGO)

The Philippines has a large and active NGO sector, many of which have supported public education. Two of the most active are Philippine Business for Social Progress (PBSP) and Philippine Business for Education (PBEd), both of which are members of the Philippine Education Forum created by DepEd.

One special organization created to work exclusively with DepEd is Teach for the Philippines, a local affiliate of the international Teach for All.

The League of Corporate Foundations, with over 50 corporate foundation members, has many that support education projects. These include such foundations as the Bato Balani Foundation, the Coca-Cola Foundation, the Ramon Aboitiz Foundation, the Jollibee Foundation, and more.

Share of Private Schools Enrollment in Basic Education in the Philippines

Language as a Key Element of Quality of Learning

Importance of Time in School Assigned to Teaching and Learning

Teacher Quality as a Key Factor Influencing Student Learning Outcomes

Curriculum Issues Affecting Student Learning Outcomes in the Philippines

Reading Performance Declining in the Philippines

Transition Issues Between Learning Stages in the Philippines

Overview of Student Learning Outcome Assessments in the Philippines

Bullying and School-Related Gender-Based Violence in the Philippines

Jasper Klint de la Fuente

High School Teacher 👩🏽🏫🍎| Lifelong Learner 📚| Passionate about developing the next generation of leaders 📝💻🎓

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Can't find what you're looking for.

We are here to help - please use the search box below.

- Where We Work

- Philippines

Assessing Basic Education Service Delivery in the Philippines: Public Education Expenditure Tracking and Quantitative Service Delivery Study

Over the last decade, the Government of the Philippines has embarked on an ambitious education reform program to ensure that all Filipinos have the opportunity to obtain the skills that they need to play a full and productive role in society. The government has backed up these reforms, particularly over the last five years, with substantial increases in investment in the sector.

While there have been improvements in education sector outcomes, significant challenges remain if the government’s goals for the education sector are to be realized. Addressing these challenges will not only require further increases in education spending but also improvements in the systems that manage and govern these resources.

A World Bank study assesses the quality of basic education services and the strength of existing systems used to allocate and manage public education resources. It tracked public education resources from national and local governments to a nationally representative sample of elementary schools and high schools in the Philippines and assessed the availability and quality of key education inputs.

The key findings of the report are as follows:

· The availability of teachers in schools has improved as a result of recent teacher hiring efforts. However, there are signs of growing inefficiency in teacher deployment because of weaknesses in teacher allocation systems.

· Teacher absenteeism rates in elementary and high schools are generally low compared to other countries. However, they tend to be high in highly urbanized cities.

· There have been big improvements in the hiring process but significant delays still exist.

· Teacher performance on content knowledge assessments is poor and professional development systems are inadequate.

School infrastructure

· The availability of key facilities has improved but classroom deficits still remain.

· Public infrastructure improvement systems suffer from many problems which result in poor quality and incomplete classrooms and water and sanitation facilities.

School funding and management

· Schools have only limited discretionary funding to implement their own school improvement plans.

· While most discretionary funding is provided by the national government, a significant portion fails to reach schools.

· Schools face difficulties in using public funds because of burdensome management and reporting requirements.

· Transparency and accountability for fund use is relatively weak at the school level.

· School level accountability through School Governing Councils is generally weak.

· Parental awareness of the existence of School Governing Councils is limited. However, parents are more aware and participate more actively in Parent Teacher Associations.

Local government funding

· Local government funding to basic education is relatively low, declining and unequal.

· Poor record-keeping and reporting makes it difficult to assess the distribution and effectiveness of local government funding for education.

· Significant differences in levels of education spending and the quality of the learning environment exist across regions and provinces.

· Even though urban schools tend to serve wealthier populations, they tend to perform poorly compared to rural schools.

· Schools serving poorer communities tend to be more resource-constrained than wealthier schools.

Detailed policy suggestions are provided in the main report for each of the topics covered. Common policy suggestions include:

· Increase public spending on education.

· Improve allocation of education inputs through better planning.

· Give schools greater authority in planning and resource management decisions and simplify reporting requirements.

· Improve transparency of fund allocation and resource use across the system.

· Strengthen the role of School Governing Councils and Parent Teacher Associations.

· Address funding and quality inequalities through improved financing mechanisms and focused interventions for schools serving disadvantaged groups.

The main findings and policy suggestions of the study are presented as a series of policy notes on specific issues as well as a combined report . In addition to the policy notes, the report provides an overview and a detailed description of the study and its approach.

- Full report: Assessing Basic Education Service Delivery in the Philippines: Public Education Expenditure Tracking and Quantitative Service Delivery Study

- Report and associated policy notes’

- East Asia Pacific

You have clicked on a link to a page that is not part of the beta version of the new worldbank.org. Before you leave, we’d love to get your feedback on your experience while you were here. Will you take two minutes to complete a brief survey that will help us to improve our website?

Feedback Survey

Thank you for agreeing to provide feedback on the new version of worldbank.org; your response will help us to improve our website.

Thank you for participating in this survey! Your feedback is very helpful to us as we work to improve the site functionality on worldbank.org.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE PHILIPPINE EDUCATION SYSTEM IN SELECTED ASEAN COUNTRIES TIME TO INVEST

Related Papers

AEI Insights

Mario Arturo Ruiz Estrada

The significant damage of COVID-19 on the world economy forces us to reconsider a deep restructuration domestically and internationally in the next few years. This paper suggests a Post-COVID-19 reconstruction model is called “The National Domestic Economic AutoSustainability Model (NDEAS-Model).” The NDEAS-Model proposes four economic platforms: (i) the domestic education and technical training standardization platform (P1); (ii) the domestic productive infrastructure and transportation platform (P2); (iii) the selective strategic trade, investment, and tourism protection platform (P3); (iv) the environmental and natural resources management platform (P4). The main objective of NDEAS-Model is to avoid imported massive pandemic diseases, non-sustainable and weak food security platforms, and job diversion, respectively.

Joselito Ereño

Eena Morada

Benjamin Jose Galela Bautista

khaliq bashar

jaechul sim

Semmy Tyar Armandha

Faraidi R Almira

The AEC has become the region’s biggest move to date, the vision of regional economic integration brings a lot of promise, one of them the improvement of economy, one of them is the anticipated free-flow of the labor force. With this amount of competition, education has got to be the main focus of the movement to make sure there will be equal opportunity for all, but the truth is not quite the same as the vision. This paper would talk about the definition of AEC and the effect of education on the employment rate of nation-states.

ralfmei ajirben

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

RELATED PAPERS

Gizelle Kim , Nehemiah Hipos

Emile Kok-Kheng Yeoh (editor) (2019), Contemporary Chinese Political Economy and Strategic Relations: An International Journal (CCPS), Vol. 5, No. 1

Emile Kok-Kheng Yeoh

ARCID China Update

Tarida Baikasame

John Polesel

William Holland

Professor Alexander Franco, Ph.D.

Oliver N A P I L A Gomez

Tek Jung Mahat

Ted Patrick B Boglosa

Brigid Freeman , John Polesel

Higher Education in Southeast Asia and Beyond

Madhav B Karki

Primer C Pagunuran

Dondie Capellan

Syamsuddin Putra Daeng Saido

Erlinda Medalla

Erdem Guven

Students Internship Project as One of Learning Experiences

natalia damastuti

Renato De Castro

In: Angress, A.& Wuttig, S. (eds.) The ASEM Education Process: History and Vision – Looking back, looking ahead

Sebastian Bersick , Julia Schwerbrock

mohammad wasil

Renato De Castro , Dindo Manhit

Hansley Juliano , Jocelyn Celero

Legal Economic Institutions,Entrepreneurship and Management. Perspectives on the Dynamics of Institutional Change from Emerging Markets.

Ernesto Alejandro O'Connor , Julio J . Nogues

Fernando Aldaba

Asian and Pacific Migration Journal 23(3):299-324, 2014

Sheila Siar

Philip Jay-ar Dimailig

Emerson Kim Lineses

Tilamsik Working Papers

Tilamsik: The Southern Luzon Journal of Arts and Sciences , Nicanor L . Guinto

The New Southern Policy – Catalyst for Deepening ASEAN-ROK Cooperation

Chiew-Ping Hoo

Contemporary Chinese Political Economy and Strategic Relations: An International Journal

Abdul Msakati

CED, MSU-IIT

Merjoerie Villareal

Alexander Degelsegger-Márquez

Asian Politics & Policy

Ador Torneo

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

- < Previous

Home > Libraries and Archives > Rizal Library > Theses/Dissertations > Browse All > 15

Theses and Dissertations (All)

A historical analysis of the philippine public education system (1901-2017) and an investigation of external investments in access and quality.

CLARISSA ISABELLE L. DELGADO , Ateneo de Manila University

Date of Award

Document type, degree name.

Master of Arts in Education, major in Educational Administration

First Advisor

Soto, Cornelia, Ph.D.

There is no such thing as a neutral educational process. Inspired by the work of Brazilian educator Paulo Freire, this statement describes the current philosophical state of education in the Philippines: The Philippine system of education is biased. Yet, while a biased system is not necessarily a problem in itself, the root challenge of the Philippine system lies in that it has never been studied holistically or chronologically from its colonial beginnings to its most recent developments. Thus, the systems inherent imbalances and biases remain unclear to this day. This impedes any ability to develop proposals and programs appropriately contextualized to a unique history and are thus not impactful, resulting in the systems current state of poor learning outcomes.This study begins with the first attempted scholarly review of the history of public education in the Philippines, from the turn of the 20th century to the present including interviews with every living Secretary of Education. Then, using the conceptual framework of Dr. Emmanuel Jimenez, Access versus Quality, further questions arise on why the current state of education has not improved: in the absence of administrative direction, what accredited nongovernment investments have been made over the years, what impact have these investments had, and if there are not alternative investments that could be explored. The thesis ultimately builds towards a proposed action. If the first question of history and its impact on the systems current state, leads to the second question of what outside investments have since been made, the proposed action highlights those investments in public education that focus on Quality and a dual approach from both the Top and the Bottom [of power]. In its final analysis, this study aims to (1) create the condition for others to be successfulby conducting a macro-level thematic investigation; (2) arm those with the capability to affect education reform or policy with context; (3) encourage Filipinos to look beyond transplanting best practices and understand historical root challenges.

The E3.D448 2018

Recommended Citation

DELGADO, CLARISSA ISABELLE L., (2018). A Historical analysis of the Philippine public education system (1901-2017) and an investigation of external investments in access and quality. Archīum.ATENEO . https://archium.ateneo.edu/theses-dissertations/15

Since March 21, 2021

Advanced Search

- Notify me via email or RSS

- Collections

- Libraries & Archives

- Ateneo Journals

- Disciplines

Author Corner

- Why contribute?

- Getting started

- Working with publishers and Open Access

- Copyright and intellectual property

- Contibutor FAQ

About Archium

- License agreement

- University website

- University libraries

Home About Help My Account Accessibility Statement

Privacy & Data Protection Copyright

AECC Global

How does the education system in the philippines compare to the rest of the world's.

It is important to understand how the tertiary or higher education system in a country works so that you can pick the best study destination abroad. The standard of education in a nation mainly depends on the amount of money that its government and private owners spend to support it. That said, you should look at certain metrics like the quality of life, job opportunities, economic security, and safety, to determine the quality of education systems around the world.

Based on these factors, we have listed below some of the countries with the best education systems in the world. Before we delve into the list, let us look at what the education system in the Philippines is like.

Let’s dive right in… The Education System in the Philippines The American Education System The UK Education System The Australian Education System The Canada Education System The New Zealand Education System The Singapore Education System Why Choose to Study in These Countries Over the Philippines? Kickstart Your Study Abroad Journey Now!

The Education System in the Philippines

The education system in the Philippines uniquely blends Eastern and Western educational traditions, marked by its recent adoption of the K-12 system, aligning with global standards. Home to over 2,000 universities and colleges, many with Roman Catholic affiliations reflecting its colonial past, the system offers a bilingual curriculum in Filipino and English. Catering to over 5,000 international students annually, it provides a diverse and inclusive learning environment across student-friendly cities like Metro Manila and Cebu.

Despite facing challenges such as underfunding, the Philippines is committed to enhancing its educational quality and global competitiveness. This evolving system, balancing traditional Filipino values with modern practices, positions the Philippines as an emerging player in global education.

Key Differences in the Philippines Education System Compared to the Global Standard

- K-12 Program: Extended basic education to 12 years, aligning more with international standards.

- Bilingual Approach: Uses both English and Filipino as mediums of instruction.

- Technical and Vocational Focus: Emphasizes vocational training through TESDA.

- Religious Affiliations: Many schools have strong religious ties, influencing their curriculum.

- Diverse Higher Education: Offers a wide range of courses with flexible pathways.

- American Educational Influence: Historically shaped by American systems, particularly in language and structure.

- Overseas Employment Orientation : Education geared towards preparing students for international job markets.

- Colonial History Impact: Unique blend of Eastern and Western educational practices due to Spanish and American colonization.

- Challenges and Reforms: Addressing issues like underfunding and regional disparities through initiatives like the K-12 program.

The Best Education Systems in the World

You should identify countries with the best education systems to make informed decisions regarding where to study further. No two countries have the same education system, so you should look at facts and figures to determine which one is right for you. With this in mind, let us dive into the list of countries with the best education system in the world.

The American Education System

The USA has some of the world's best universities and student cities. US universities offer over two million programs and employ semester- or trimester-based schedules for admission. Higher education is a part of the American education system, and almost every university in it follows a semester credit hours system that requires students to complete 30 credits or more for a degree.

Larger US universities have individual schools or colleges for different fields of study, like business schools and engineering colleges. As per the National Center for Education Statistics, the USA has over 5,900 tertiary education institutions, many of which play a part in holding the American education system in high regard – which means a higher number of programs on offer for international students. There are three university intake periods in the country: fall (starting in August), spring (starting in January), and summer (starting around May).

|

| 46 |

|

| 14 |

|

| 16 |

|

| 3 |

The UK Education System

The United Kingdom is also home to some of the top-ranking universities and best student cities in the world. The UK offers its international students access to more than just quality education – starting from the affordable tuition fees to its student-friendly visa policies, the education system in the UK has so much going for it.

Higher education providers in the UK offer great flexibility to students with 3-year bachelor's, 1-year master's, and 2-year doctoral degree options. The UK education system allows students to benefit from dynamic learning experiences and opportunities, such as workshops, conferences, seminars, and webinars. The UK has two intake periods: September to October and January to February. However, certain UK universities also have April/May intakes for some programs.

|

| 33 |

|

| 15 |

|

| 22 |

|

| 2 |

The Australian Education System

Australia has 43 universities as well as other institutions that provide higher education programs. Many of these universities rank among the world's best, which helps put the Australian education system in the spotlight. Students also enrol in combined bachelor's degree programs in Australia, leading to the grant of two bachelor's qualifications. This is more common in commerce, science, the arts, and law . Institutions in Australia also offer courses in business, management, engineering , humanities , health sciences, technology, environmental science, finance , medicine , and so forth.

Under the Australian education system, students must complete a certain number of credit points. Undergraduate students must complete 144 points, while postgraduate students must complete 96 points. There are two major intake periods at universities in Australia: February to May (or March to June) and July/August to November. That said, some universities in Australia also invite applications in the summer.

|

| 18 |

|

| 7 |

|

| 21 |

|

| 2 |

The Canada Education System

The Canada education system ticks a lot of boxes, especially when it comes to higher education, as the country is home to some of the world's best universities and student cities. The country has more than 800,000 international students, as per the latest data from IRCC, the department of immigration. Some facets of the Canada education system may vary between provinces, but there are consistently high standards of education throughout the nation. Apart from the quality of education and the welcoming and diverse culture, it is the relatively lower tuition fees and cost of living that make Canada a magnet for international students.

Engineering , business, the arts, and medicine are among the best-known programs opted for by international students in Canada. There are three intake periods at universities in Canada: fall (September), winter (January), and summer (May).

|

| 11 |

|

| 4 |

|

| 27 |

|

| 3 |

The New Zealand Education System

The tuition fees in New Zealand are way more affordable than some of the other major study destinations. This is startling, especially for a country that offers world-class higher education. The country is known for its doctoral research opportunities, especially with regard to PhD. Unlike some of the other countries, international PhD candidates in New Zealand only have to pay the same tuition fees as domestic students and can work any number of hours while studying. There are also no restrictions on work hours for foreign nationals who pursue master's degrees in New Zealand.

The government of New Zealand invests heavily in new pieces of technology, like machine learning and artificial intelligence, in addition to research tie-ups with top international universities. There are two major intake periods in New Zealand: February to June and July to November.

|

| 5 |

|

| 2 |

|

| 17 |

|

| 2 |

The Singapore Education System

Students in Singapore have high scores in the PISA world rankings, leading to the Singapore education system earning high esteem. The country has a bilingual policy that focuses on education in English and the native language of any of the local ethnic communities. This is one aspect of the Singapore education system that makes it unique.

There are six autonomous universities in the country, in addition to the privately-funded SIM University. Singapore also has branches of ten foreign institutions that offer higher education programs and two privately-funded arts colleges. Some government-affiliated institutions also offer degree programs in Singapore.

Singapore universities attract a large number of teachers and students from all over the world. A majority of foreign academics and students go to the National University of Singapore and Nanyang Technological University. Universities in the country have also made major breakthroughs in science and modern technology.

There are two intake periods at universities in Singapore: one starting in August and the other in January. Travel and tourism, aviation , business administration, engineering , and science are among the most popular course options pursued by international students in Singapore. Singapore has plenty of study programs that place an emphasis on the development of skills to prepare students for life after graduation.

|

| 2 |

|

| 1 |

|

| 30 |

|

| 2 |

Grading System in the Philippines vs. Other Countries: Detailed Comparison

- Primary & Secondary: Percentage-based, 75% typically the passing mark.

- Higher Education: Numeric scale from 1.0 (excellent) to 5.0 (fail).

- Letter grades: A (excellent) to F (fail).

- GPA: Scale of 0.0 to 4.0, with 4.0 being the highest.

- Numerical scale: Commonly 1 (lowest) to 10 or 20 (highest), varying by country.

- Mix of letter grades, percentages, or numerical scales.

- For example, Japan uses a scale of 1 (lowest) to 5 (highest), with 5 being excellent.

- Shift towards holistic assessment aligning with global standards.

- Emphasis on skills and competencies alongside academic performance.

- Adapting to resource constraints and regional educational disparities.

- Flexible assessment methods, especially in response to the pandemic.

- Western countries often favour GPA and letter grades for broader assessment.

- Asian and European countries may use more varied and localised grading systems.

Why Should You Choose to Study in These Countries Over the Philippines?

The education system in the Philippines ranks among the best in Asia. That said, you may want to consider higher education in any of the other countries as they have certain perks and opportunities that put them ahead of the pack. Here are some of the other features of tertiary education in the other nations that you may want to consider before determining where to study.

- More intake periods: There are more than two intake periods in the non-Asian countries mentioned above, including summer intakes. This offers you more windows to apply to a higher education institute and start your studies at virtually any time during the year without missing out on classes.

- Greater potential return on investment: The tuition fees for undergraduate, postgraduate and doctoral degrees abroad may be more as compared to the Philippines, but you can earn more with any of these qualifications. After you reach a point where your income exceeds your cost of studying abroad, you will start to realise the value of the greater income there. In most cases, you will breach that break-even point after one year of graduation.

- Greater quality research: There are some universities with research capabilities in the Philippines, but most study destinations abroad have a higher number of public research universities with "above world standard research". The quality of university research matters for students as it helps them have a more comprehensive analysis of certain topics. With a more in-depth analysis of a topic, you will have more fruitful results and greater knowledge.

Which country has the best education system in the world?

The word 'best' is subjective. Each country has its own unique higher education system, making it difficult to pick one over the rest. It is more important to consider whether a particular country's education system suits your preferences and requirements. For instance, you may find it more useful to have unlimited work hours with a PhD in New Zealand or a STEM degree for a prolonged stay in the USA.

Which factors affect the standard of higher education the most?

The main factors that impact the standard of post-secondary education are the quality of academics, available technological infrastructure, curriculum standards, accreditation regime, research environments, as well as the administrative procedures and policies implemented at higher educational institutions.

Why is European education good?

There are many factors that help explain why higher education in Europe is highly regarded across the globe, including the greater number of academic opportunities and greater access to university research. A combination of these factors results in globally recognised qualifications.

What is unique about the Australian education system?

The use of academic credit points is a factor that makes the Australian education system different from many other countries. Academic credits are used and recognised all over the world, but unlike in other countries, each university in Australia has its own credit system.

How does the European credit system differ from the UK one?

The credit system is one aspect that differentiates the European education system from the rest of the world. Aside from the UK, all European countries follow the ECTS system. A year of education equals 60 ECTS credits, and the workload for one ECTS credit is 25 to 30 hours of study. On the other hand, one academic credit in the UK numerically represents the level of knowledge and/or skills acquired in 10 notional hours.

If you are still in two minds about where to pursue higher education, feel free to approach our counsellors to get help in making the best decision possible.

Contact us right away!

About the author

Related Posts

English language – your access to the world, australian education system for international students overview, uk education system for international students overview.

Let's get social.

- fab fa-facebook-square

- fab fa-linkedin

- fab fa-instagram

Our Services

Study destinations.

Study in Australia Study in USA Study in Canada Study in UK Study in New Zealand Study in Ireland Other Study Destinations

Our Timeline

Our Leadership Team

Partner With Us

Awards Recognitions

Quick Links

- Australia |

- Bangladesh |

- Indonesia |

- Philippines |

- Singapore |

- Sri Lanka |

- Admission Counselling

- Student Health Insurance

- Student Accommodation

- Student Visa For Australia

- Student Visa For Canada

- Student Visa For New Zealand

- Student Visa For UK

- Student Visa For USA

- Personality Assessment Test

- Virtual Internships

- Australia Universities

- Canada Universities

- New Zealand Universities

- UK Universities

- USA Universities

- Ireland Universities

- Architecture

- Social Work

- Human Resource Management

- Digital Marketing

- Business Analytics

- Logistics and Supply Chain Management

- Creative Arts, Design & Communication

- Computer Science

- Cybersecurity

- Data Science

- Information Technology

- Hotel Management

- Culinary Arts

- Scholarships in Australia

- Scholarships in New Zealand

- Scholarships in Canada

- Scholarships in United Kingdom

- Scholarships in USA

- Fill out an Enquiry

- Book An Appointment

- Visit our Virtual Office

- Upcoming Events

Your Passport to International Education! Sign Up for a Free Consultation session

- Top Stories

- Pinoy Abroad

- #ANONGBALITA

- Economy & Trade

- Banking & Finance

- Agri & Mining

- IT & Telecom

- Fightsports

- Sports Plus

- One Championship

- Paris Olympics

- TV & Movies

- Celebrity Profiles

- Music & Concerts

- Digital Media

- Culture & Media

- Health and Home

- Accessories

- Motoring Plus

- Commuter’s Corner

- Residential

- Construction

- Environment and Sustainability

- Agriculture

- Performances

- Malls & Bazaars

- Hobbies & Collections

President Ferdinand Marcos, Jr. on Friday called for sweeping reforms to the country’s education system amid the lackluster performance of Filipino students in the 12 years since the K-12 program was implemented.

The chief executive called for solutions to teaching gaps ahead of Senator Sonny Angara’s stepping in as head of the Department of Education (DepEd) when Vice President Sara Duterte vacates the position on July 19.

President Marcos emphasized the need to enhance graduates’ employability under the K-12 system, which he said has fallen short of expectations.

“If you remember, we implemented K-12 because employers were looking for more years of training from our job applicants and here in the Philippines, it was lacking because it was only 10 years (primary plus secondary education), so we needed 12 years,” he said.

“Okay. So, that was the reason we did it to make our graduates more employable,” he added.