IEEE Account

- Change Username/Password

- Update Address

Purchase Details

- Payment Options

- Order History

- View Purchased Documents

Profile Information

- Communications Preferences

- Profession and Education

- Technical Interests

- US & Canada: +1 800 678 4333

- Worldwide: +1 732 981 0060

- Contact & Support

- About IEEE Xplore

- Accessibility

- Terms of Use

- Nondiscrimination Policy

- Privacy & Opting Out of Cookies

A not-for-profit organization, IEEE is the world's largest technical professional organization dedicated to advancing technology for the benefit of humanity. © Copyright 2024 IEEE - All rights reserved. Use of this web site signifies your agreement to the terms and conditions.

Information

- Author Services

Initiatives

You are accessing a machine-readable page. In order to be human-readable, please install an RSS reader.

All articles published by MDPI are made immediately available worldwide under an open access license. No special permission is required to reuse all or part of the article published by MDPI, including figures and tables. For articles published under an open access Creative Common CC BY license, any part of the article may be reused without permission provided that the original article is clearly cited. For more information, please refer to https://www.mdpi.com/openaccess .

Feature papers represent the most advanced research with significant potential for high impact in the field. A Feature Paper should be a substantial original Article that involves several techniques or approaches, provides an outlook for future research directions and describes possible research applications.

Feature papers are submitted upon individual invitation or recommendation by the scientific editors and must receive positive feedback from the reviewers.

Editor’s Choice articles are based on recommendations by the scientific editors of MDPI journals from around the world. Editors select a small number of articles recently published in the journal that they believe will be particularly interesting to readers, or important in the respective research area. The aim is to provide a snapshot of some of the most exciting work published in the various research areas of the journal.

Original Submission Date Received: .

- Active Journals

- Find a Journal

- Proceedings Series

- For Authors

- For Reviewers

- For Editors

- For Librarians

- For Publishers

- For Societies

- For Conference Organizers

- Open Access Policy

- Institutional Open Access Program

- Special Issues Guidelines

- Editorial Process

- Research and Publication Ethics

- Article Processing Charges

- Testimonials

- Preprints.org

- SciProfiles

- Encyclopedia

Article Menu

- Subscribe SciFeed

- Google Scholar

- on Google Scholar

- Table of Contents

Find support for a specific problem in the support section of our website.

Please let us know what you think of our products and services.

Visit our dedicated information section to learn more about MDPI.

JSmol Viewer

New trends in e-commerce research: linking social commerce and sharing commerce: a systematic literature review.

1. Introduction

- What are the different issues/difficulties related to S-Commerce and sharing commerce?

- What are the various benefits of S-Commerce and sharing commerce?

2. Background

2.1. e-commerce, 2.2. s-commerce, 2.3. sharing commerce, 2.4. historical development/evolution of e-commerce, s-commerce, and sharing commerce, 3. methodology, 3.1. review protocol, 3.2. inclusion and exclusion criteria, 3.3. search strategy and study selection process, 3.4. quality assessment, 3.5. data extraction and synthesis, 3.5.1. publication sources overview, 3.5.2. temporal view of publication, 3.5.3. research methodologies, 3.5.4. theoretical foundations: classification of theories are based on the primary goals of each theory, 4. research questions (rqs) results, 4.1. what are the definitions of s-commerce and sharing commerce, 4.2. what are the various themes revealed by the systematic review, 4.3. what are the various factors to be understood in linking s-commerce and sharing commerce, 4.3.1. what are the challenges/issues associated with s-commerce and sharing commerce, 4.3.2. what are the various benefits/advantages of s-commerce and sharing commerce, 5. research propositions, 5.1. conceptual and theoretical development, 5.1.1. defining the key concepts and terms, 5.1.2. understanding, theorising, and measuring various integrating and influencing factors in online commerce and measuring impact, 5.2. design and interaction, 5.2.1. the role of socio-cultural factors in facilitating decision making, 5.2.2. the role of design and technological factors in facilitating decision making, 5.2.3. the role of behavioural factors in facilitating decision-making, 5.2.4. the role of various factors in linking s-commerce and sharing commerce, 5.3. implementation, 5.3.1. understanding critical success factors, 5.3.2. culture and adoption, 5.3.3. ethical and legal issues, 6. ideas for future research, 7. conclusions, supplementary materials, author contributions, acknowledgments, conflicts of interest.

| Study | Criterion #1 | Criterion #2 | Criterion #3 | Criterion #4 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rong, K., Hu, J., Ma, Y., Lim, M., Liu, Y., and Lu, C. [ ] | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.25 |

| Nica, E. and Potcovaru, A. [ ] | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Wigand, R., Benjamin, R., and Birkland, J. [ ] | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Ganapati, S., and Reddick, C. [ ] | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1.25 |

| Jeonghye, K., Youngseog Y. and Hangjung, Z. [ ] | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1.25 |

| Marinkovic, S., Gatalica, B., and Rakicevic, J. [ ] | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1.25 |

| Noor, A., Sulaiman, R. and Bakar, A. [ ] | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1.25 |

| Heinrichs, H. [ ] | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1.25 |

| Abed, S., Dwivedi, Y. and Williams, M. [ ] | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1.5 |

| Bianchi, C., Andrews, L., Wiese, M. and Fazal-E-Hasan, S. [ ] | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1.5 |

| Gregory, A., and Halff, G. [ ] | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1.5 |

| Hamari, J., Sjöklint, M., and Ukkonen, A. [ ] | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1.5 |

| Lutz, C., Hoffmann, C., Bucher, E., and Fieseler, C. [ ] | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1.5 |

| Mohd F. and Rosli M.H.B. [ ] | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1.5 |

| Parves, K. and Jim Q. C. [ ] | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1.5 |

| Pei, Z., and Yan, R. [ ] | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1.5 |

| Habibi, M., Davidson, A. and Laroche, M. [ ] | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1.5 |

| Featherman, M. and Hajli, N. [ ] | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1.5 |

| Liang, T. and Turban, E. [ ] | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1.5 |

| Chen et al. [ ] | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1.5 |

| Martin, C. [ ] | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1.5 |

| Geissinger, A., Laurell, C. Oberg, C. and Sandstrom, C. [ ] | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1.5 |

| Zang, T., Gu, H. and Jahromi, M. [ ] | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1.5 |

| Mody, M., Suess, C. and Lethto, X. [ ] | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1.5 |

| Kim, D. [ ] | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1.5 |

| Biucky, S., Abdolvand, N., and Harandi, S. R. [ ] | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1.75 |

| Escobar-Rodríguez, T., and Bonsón-Fernández, R. [ ] | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1.75 |

| Gibreel, O., AlOtaibi, D., and Altmann, J. [ ] | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1.75 |

| Hajli, N., Lin, X., Featherman, M.S., Wang, Y. [ ] | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1.75 |

| Hashim, N. A., Nor, S.M., Janor, H. [ ] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1.75 |

| Lal, P. [ ] | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1.75 |

| Lee, Z., Chan, T., Balaji, M., and Chong, A. [ ] | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1.75 |

| Mittendorf, C. [ ] | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1.75 |

| Mohlmann, M. [ ] | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1.75 |

| Rad A. A. and Benyoucef M. [ ] | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1.75 |

| Sheikh, Z., Islam, T., Rana, S., Hameed, Z., and Saeed, U. [ ] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1.75 |

| Sigala, M. [ ] | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1.75 |

| ter Huurne, M., Ronteltap, A., Corten, R., and Buskens, V. [ ] | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1.75 |

| Wang, Y. and Hajli, M. [ ] | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1.75 |

| Wang, Y. and Yu, C. [ ] | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1.75 |

| Yahia, I., Al-Neama, N., and Kerbache, L. [ ] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1.75 |

| Chen, A., Lu, Y. and Wang, B. [ ] | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1.75 |

| Hu, T., Dai, H. and Salam, A. [ ] | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1.75 |

| Esmaeili, L. and Hashemi, S. [ ] | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1.75 |

| Liu, H., Chu, H., Huang, Q. and Chen, X. [ ] | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1.75 |

| Shanmugam, M. and Jusoh, Y. [ ] | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1.75 |

| Zheng, X., Zhu, S. and Lin, Z [ ] | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1.75 |

| Stephen, A. and toubia, O. [ ] | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1.75 |

| Ng, C. [ ] | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1.75 |

| Akman, I and Mishra [ ] | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1.75 |

| Bai, Y., Yao, Z. and Dou, Y. [ ] | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1.75 |

| Zhou, H. and Miao, Y. [ ] | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1.75 |

| Chen, X. and Tao, J. [ ] | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1.75 |

| Baghdadi, Y. [ ] | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1.75 |

| Baethge, C., Klier, J. and Klier, M. [ ] | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1.75 |

| Chen, J., Su, B. and Widjaja, A. [ ] | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1.75 |

| Wang, Y., Hsiao, S., Yang, Z. and Hajli, N. [ ] | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1.75 |

| Zhang, K. and Benyoucef, M. [ ] | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1.75 |

| Li, C. and Ku, Y. [ ] | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1.75 |

| Chung, N., Song, H. and Lee, H. [ ] | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1.75 |

| Wang, C. and Zhang, P. [ ] | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1.75 |

| Liang, T., Ho, Y., Li, Y. and Turban, E. [ ] | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1.75 |

| Popescu, G. [ ] | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1.75 |

| Wallsten, S. [ ] | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1.75 |

| Seo, A., Jeong, J. and Kim, Y. [ ] | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1.75 |

| Bansal, G and Chen, L. [ ] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Bilgihan, A., Barreda, A., Okumus, F., and Nusair, K. [ ] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Hajli, M. [ ] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Hajli, N. [ ] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Kim, S., Noh, M. and Lee, K. [ ] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Kim, S., Sun, K. and Kim, D. [ ] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Ko, H. [ ] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Kwahk, K. and Ge, X. [ ] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Lai S.L. [ ] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Lin, J., Luo, Z., Cheng, X., and Li, L. [ ] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Liu, L., Cheung, C., and Lee, M. [ ] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Lu, B., Fan, W., and Zhou, M. [ ] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Saundage, D. and Lee, C.Y. [ ] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Shanmugam, M., Sun, S., Amidi, A., Khani, F. and Khani, F. [ ] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Sharma, S. and Crossler, R. [ ] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Wang, C. and Zhang, P. [ ] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Zhang, H., Lu, Y., Gupta, S. and Zhao, L. [ ] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Zhang, M., Fu, Y., Zhao, Z., Pratap, S., and Huang, G. [ ] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Wang, Y. and Herrando, C. [ ] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Wang, X. Lin, X. and Spencer, M [ ] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Kim, N. and Kim, W [ ] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Aladwani, A. [ ] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Osatuyi, B. and Qin, H [ ] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Zhang, h., Zhao, L. and Gupta, S. [ ] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Fu, S., Yan, Q. and Fen, G. [ ] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Lin, X., Li, Y. and Wang, X [ ] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Ahmad, S. and Laroche, M [ ] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Chen, Y., Lu, Y., Wang, B. and Pan, Z. [ ] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Kong, Y., Wang, Y., Hajli, S. and Featherman, M. [ ] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Tajvidi et al. [ ] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Kim, S. and Park, H. [ ] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Ng, C. [ ] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Friedrich, T. [ ] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Hajli, N and Sims, J. [ ] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Hajli, N., Sims, J., Zadeh, A. H., and Richard, M. O. [ ] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Cheng, X. Gu, Y., and Shen, Y. [ ] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Chen, J and Shen, X. [ ] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Xiang, L., Zheng, X., Lee, M. and Zhao, D. [ ] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Kim, S. and Noh, M. [ ] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Wu, Y. and Li, E. [ ] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Williams, M. [ ] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Wongkitrungruenga, A. and Assarut, N. [ ] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Molinillo, S., Anaya-Sanchez, R. and Liebana-Cabanillas, F. [ ] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Zhang, M., Guo, L. and Liu, W. [ ] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Yu, C., Tsai, C., Wang, Y., Lai, K. and Tajvidi, M. [ ] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Lam et al. [ ] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Bugshan and Attar [ ] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Choi [ ] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Zhai et al. [ ] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Ariesty and Sari [ ] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Su et al. [ ] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Ebrahimi et al. [ ] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Rai et al. [ ] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Liu et al. [ ] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Wang et al. [ ] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Da Costa and Casais [ ] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Hsieh and Lo [ ] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Liao et al. [ ] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Busalim et al. [ ] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Yang [ ] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Lina and Ahluwalia [ ] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Molinillo et al. [ ] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Hsiao [ ] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Xiang et al. [ ] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Hu et al. [ ] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Goyal et al. [ ] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Dinulescu et al. [ ] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Lăzăroiu et al. [ ] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Abdelsalam et al. [ ] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Xue et al. [ ] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Sohn and Kim [ ] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Esmaeli et al. [ ] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Nadeem et al. [ ] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Leong et al. [ ] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Hu et al. [ ] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Curty, R.G. and Zhang, P [ ] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Shen et al. [ ] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Huang and Benyoucef [ ] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

- Hajli, N. Social commerce constructs and consumer’s intention to buy. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2015 , 35 , 183–191. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Wigand, R.T.; Benjamin, R.I.; Birkland, J.L.H. Web 2.0 and beyond. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Electronic Commerce, Innsbruck, Austria, 19–22 August 2008; Volume 7. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Netscribes. 5 Emerging Technology Trends in E-Commerce. Available online: https://www.netscribes.com/ecommerce-technology-trends/ (accessed on 4 April 2019).

- ECommerce News. Amazon and eBay Account for 66% of German Ecommerce. Available online: https://ecommercenews.eu/amazon-and-ebay-account-for-66-of-german-ecommerce/ (accessed on 6 April 2019).

- Coresight Research. Deep Dive: Profiling Ten of the World’s Biggest E-Commerce Marketplaces, from Alibaba to Zalando. Available online: https://coresight.com/research/deep-dive-profiling-ten-of-the-worlds-biggest-e-commerce-marketplaces-from-alibaba-to-zalando-1/ (accessed on 5 April 2019).

- Scupids Tech. A Chatbot for Your Ecommerce Store and Customer Support Buy. Available online: https://morph.ai/ecommerce (accessed on 28 May 2020).

- Lastovetska, A. Future of E-Commerce: Innovations to Watch Out for. Available online: https://mlsdev.com/blog/future-of-e-commerce-innovations-to-watch-out-for-new (accessed on 10 April 2019).

- Lu, B.; Fan, W.; Zhou, M. Social presence, trust, and social commerce purchase intention: An empirical research. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016 , 56 , 225–237. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Pothong, C.; Sathitwiriyawong, C. Factors of s-commerce influencing trust and purchase intention. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Computer Science and Engineering Conference (ICSEC), Chiangmai, Thailand, 14–17 December 2016; pp. 1–5. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Escobar-Rodríguez, T.; Bonsón-Fernández, R. Analysing online purchase intention in Spain: Fashion e-commerce. Inf. Syst. e-Bus. Manag. 2016 , 15 , 599–622. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Biucky, S.T.; Abdolvand, N.; Harandi, S.R. The Effects of Perceived Risk on Social Commerce Adoption Based on Tam Model. Int. J. Electron. Commer. Stud. 2017 , 8 , 173–196. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Hashim, N.A.; Nor, S.M.; Janor, H. Riding the waves of social commerce: An empirical study of Malaysian entrepreneu. Malays. J. Soc. Space 2016 , 12 , 83–94. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hamari, J.; Sjöklint, M.; Ukkonen, A. The sharing economy: Why people participate in collaborative consumption. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2015 , 67 , 2047–2059. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Jeonghye, K.; Youngseog, Y.; Hangjung, Z. Why people participate in the sharing economy: A social exchange perspective. In Proceedings of the PACIS 2015 Proceedings, Singapore, 5–9 July 2015. [ Google Scholar ]

- Mittendorf, C. What Trust means in the sharing economy: A provider perspective on Airbnb.com. Conference on digital commerce—Ebusiness and ecommerce (Sigebiz). In Proceedings of the Americas’ Conference on Information Systems, San Diego, CA, USA, 11–14 August 2016. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bilgihan, A.; Barreda, A.; Okumus, F.; Nusair, K. Consumer perception of knowledge-sharing in travel-related Online Social Networks. Tour. Manag. 2016 , 52 , 287–296. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Schafer, J.B.; Konstan, J.; Riedi, J. Recommender systems in e-commerce. In Proceedings of the 1st ACM Conference on Electronic Commerce, Denver, CO, USA, 3–5 November 1999. [ Google Scholar ]

- Cui, L.; Huang, S.; Wei, F.; Tan, C.; Duan, C.; Zhou, M. SuperAgent: A customer service Chatbot for E-commerce websites. In Proceedings of the ACL 2017, System Demonstrations, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 30 July–4 August 2017; pp. 97–102. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Scarano, G. Global E-Commerce Sales to Top $ 4 Trillion in 2020. Available online: https://sourcingjournal.com/topics/retail/global-ecommerce-4-trillion-2020-51929/ (accessed on 26 October 2022).

- Hajli, N.; Sims, J. Social commerce: The transfer of power from sellers to buyers. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2015 , 94 , 350–358. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Liang, T.-P.; Ho, Y.-T.; Li, Y.-W.; Turban, E. What Drives Social Commerce: The Role of Social Support and Relationship Quality. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2011 , 16 , 69–90. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Clancy, H. Want to Make Your E-Commerce Site More Social? Here’s One Way/ZDNet. Available online: http://www.zdnet.com/article/want-to-make-your-e-commerce-site-more-social-heres-one-way/ (accessed on 22 January 2018).

- Kim, D. Under what conditions will social commerce business models survive? Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2013 , 12 , 69–77. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Zhou, H.; Miao, Y. Electronic commerce development research in sharing economic environment. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Culture, Education and Financial Development of Modern Society (ICCESE 2017), Moscow, Russia, 12–13 March 2017. [ Google Scholar ]

- Liang, T.P.; Turban, E. Introduction to the Special Issue Social Commerce: A Research Framework for Social Commerce. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2011 , 16 , 5–13. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Mohd, F.B.; Rosli, M.H. Social commerce (S-Commerce): Towards the future of retailing market industry. Bus. Econ. Res. 2015 , 13 , 5977–5985. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hopkins, J. 3 C’s of Social Media Marketing: Content, Community & Commerce. Available online: https://blog.hubspot.com/blog/tabid/6307/bid/15948/3-c-s-of-social-media-marketing-content-community-commerce.aspx (accessed on 22 January 2018).

- Lai, L.S.L. Social Commerce—E-commerce in Social Media Context. Int. Sci. Index Econ. Manag. Eng. 2010 , 4 , 39–44. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lal, P. Analysing determinants influencing an individual’s intention to use social commerce website. Future Bus. J. 2017 , 3 , 70–85. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Leitner, D. PPC Adventures Part 5: E-Commerce Trends and Best Practice Online Shops. Available online: https://smarter-ecommerce.com/blog/en/ecommerce/ppc-adventures-e-commerce-trends-best-practice-online-shops/ (accessed on 16 April 2019).

- Parves, K.; Jim, Q.C. Trust in Sharing Economy. In Proceedings of the Pacific Asia Conference on Information Systems, Chiayi, Taiwan, 27 June–1 July 2016. [ Google Scholar ]

- Liu, L.; Cheung, C.M.; Lee, M.K. An empirical investigation of information sharing behavior on social commerce sites. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2016 , 36 , 686–699. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Ko, H.-C. Social desire or commercial desire? The factors driving social sharing and shopping intentions on social commerce platforms. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2018 , 28 , 1–15. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Sigala, M. Collaborative commerce in tourism: Implications for research and industry. Curr. Issues Tour. 2014 , 20 , 346–355. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Nica, E.; Potcovaru, A. The Social Sustainability of the Sharing Economy. J. Econ. Manag. Financ. Mark. 2015 , 1 , 69–75. [ Google Scholar ]

- Marinkovic, S.; Gatalica, B.; Rakicevic, J. New technologies in commerce and sharing economy. In Proceedings of the 19th Toulon-Verona International Conference, Huelva, Spain, 5–6 September 2016. [ Google Scholar ]

- Zhang, M.; Fu, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Pratap, S.; Huang, G.Q. Game theoretic analysis of horizontal carrier coordination with revenue sharing in E-commerce logistics. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2018 , 57 , 1524–1551. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Möhlmann, M. Collaborative consumption: Determinants of satisfaction and the likelihood of using a sharing economy option again. J. Consum. Behav. 2015 , 14 , 193–207. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Huurne, M.T.; Ronteltap, A.; Corten, R.; Buskens, V. Antecedents of trust in the sharing economy: A systematic review. J. Consum. Behav. 2017 , 16 , 485–498. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Gregory, A.; Halff, G. Understanding public relations in the ‘sharing economy’. Public Relat. Rev. 2017 , 43 , 4–13. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Mero, K. E-Commerce. Available online: https://www.studocu.com/row/document/girne-amerikan-universitesi/electronic-circuits-i/ecommerce/9184918 (accessed on 22 October 2022).

- Tkacz, E. Internet Technical Development and Applications ; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2009. [ Google Scholar ]

- Winterman, D.; Kelly, J. Online Shopping: The Pensioner Who Pioneered a Home Shopping Revolution. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-24091393 (accessed on 26 October 2022).

- Wang, C.; Zhang, P. The evolution of Social Commerce: The People, Management, Technology, and Information Dimensions. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2012 , 31 , 5. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Kim, S.; Noh, M.-J.; Lee, K.-T. Effects of Antecedents of Collectivism on Consumers’ Intention to Use Social Commerce. J. Appl. Sci. 2012 , 12 , 1265–1273. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Bansal, G.; Chen, L. If they trust our E-commerce Site, will they trust our social commerce site too? Differentiating the trust in e-commerce and s-commerce: The moderating role of privacy and security concerns. In Proceedings of the MWAIS, Omaha, NE, USA, 20–21 May 2011. [ Google Scholar ]

- Cecere, L. Rise of Social Commerce: A Trail Guide for the Social Commerce Pioneer. Available online: http://www.supplychainshaman.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/11/rise_of_social_commerce_final.pdf (accessed on 22 January 2018).

- Hajli, M. Social commerce adoption model. In Proceedings of the UK Academy for Information Systems Conference, Oxford, UK, 26–28 March 2012. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kwahk, K.-Y.; Ge, X. The effects of social media on e-commerce: A perspective of social impact theory. In Proceedings of the 2012 45th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Maui, HI, USA, 4–7 January 2012; pp. 1814–1823. [ Google Scholar ]

- Rad, A.A.; Benyoucef, M. A Model for Understanding Social Commerce. J. Inf. Syst. Appl. Res. (JISAR) 2012 , 4 , 63–73. [ Google Scholar ]

- Noor, A.; Sulaiman, R.; Bakar, A. A review of factors that influenced online trust in social commerce. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Information Technology and Multimedia, Osaka, Japan, 6–8 January 2018. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hajli, N.; Lin, X.; Featherman, M.; Wang, Y. Social Word of Mouth: How Trust Develops in the Market. Int. J. Mark. Res. 2014 , 56 , 673–689. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Zhang, H.; Lu, Y.; Gupta, S.; Zhao, L. What motivates customers to participate in social com-merce? The impact of technological environments and virtual customer experiences. Inf. Manag. 2014 , 51 , 1017–1030. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Wang, Y.; Hajli, M. Co-Creation in branding through social commerce: The role of social support, relationship quality and privacy concerns. In Proceedings of the Twentieth Americas Conference on Information Systems, Savannah, Georgia, 7–9 August 2014; Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2449127 (accessed on 22 November 2022).

- Shanmugam, M.; Sun, S.; Amidi, A.; Khani, F.; Khani, F. The applications of social commerce constructs. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2016 , 36 , 425–432. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Yahia, I.B.; Al-Neama, N.; Kerbache, L. Investigating the drivers for social commerce in social media platforms: Importance of trust, social support and the platform perceived usage. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018 , 41 , 11–19. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Gibreel, O.; AlOtaibi, D.A.; Altmann, J. Social commerce development in emerging markets. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2018 , 27 , 152–162. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Wang, Y.; Yu, C. Social interaction-based consumer decision-making model in social commerce: The role of word of mouth and observational learning. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2017 , 37 , 179–189. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Bianchi, C.; Andrews, L.; Wiese, M.; Fazal-E-Hasan, S. Consumer intentions to engage in s-commerce: A cross-national study. J. Mark. Manag. 2017 , 33 , 464–494. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Lin, J.; Luo, Z.; Cheng, X.; Li, L. Understanding the interplay of social commerce affordances and swift guanxi: An empirical study. Inf. Manag. 2019 , 56 , 213–224. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Yu, C.-H.; Tsai, C.-C.; Wang, Y.; Lai, K.-K.; Tajvidi, M. Towards building a value co-creation circle in social commerce. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018 , 108 , 105476. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Pei, Z.; Yan, R. Cooperative behavior and information sharing in the e-commerce age. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2018 , 76 , 12–22. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Rong, K.; Hu, J.; Ma, Y.; Lim, M.K.; Liu, Y.; Lu, C. The sharing economy and its implications for sustainable value chains. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018 , 130 , 188–189. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Lee, Z.W.Y.; Chan, T.K.; Balaji, M.; Chong, A.Y.-L. Why people participate in the sharing economy: An empirical investigation of Uber. Internet Res. 2018 , 28 , 829–850. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Ganapati, S.; Reddick, C.G. Prospects and challenges of sharing economy for the public sector. Gov. Inf. Q. 2018 , 35 , 77–87. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Lutz, C.; Hoffmann, C.P.; Bucher, E.; Fieseler, C. The role of privacy concerns in the sharing economy. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2017 , 21 , 1472–1492. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Kitchenham, B.; Charters, S. Guidelines for performing systematic literature reviews in software engineering. Engineering 2007 , 45 , 1051. [ Google Scholar ]

- Busalim, A.H.; Hussin, A.R.C. Understanding social commerce: A systematic literature review and directions for further research. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2016 , 36 , 1075–1088. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Esmaeili, L.; Hashemi, G.S.A. A systematic review on social commerce. J. Strateg. Mark. 2017 , 27 , 317–355. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The Prisma 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021 , 372 , n71. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Webster, J.; Watson, R.T. Analyzing the past to prepare for the future: Writing a literature review. MIS Q. 2002 , 26 , 13–23. [ Google Scholar ]

- Levy, Y.; Ellis, T.J. A Systems Approach to Conduct an Effective Literature Review in Support of Information Systems Research. Inf. Sci. Int. J. Emerg. Transdiscipl. 2006 , 9 , 181–212. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ] [ Green Version ]

- Bandara, W.; Miskon, S.; Fielt, E. A systematic, tool-supported method for conducting literature reviews in IS. In Proceedings of the 19th European Conference on Information Systems, Helsinki, Finland, 9–11 June 2011. [ Google Scholar ]

- Nidhra, S.; Yanamadala, M.; Afzal, W.; Torkar, R. Knowledge transfer challenges and mitigation strategies in global software development—A systematic literature review and industrial validation. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2013 , 33 , 333–355. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Stephen, A.T.; Toubia, O. Deriving Value from Social Commerce Networks. J. Mark. Res. 2010 , 47 , 215–228. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Ng, C.S.P. Examining the cultural difference in the intention to purchase in social commerce. In Proceedings of the Pacific Asia Conference on Information Systems, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, 11–15 July 2012; p. 163. [ Google Scholar ]

- Chen, X.; Tao, J. The impact of users’ participation on EWoM on social commerce sites: An empirical analysis based on Meilishuo.com. In Proceedings of the2012 4th International Conference on Multi-media Information Networking and Security, Nanjing, China, 2–4 November 2012; pp. 810–815. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Popescu, G.H. E-commerce effects on social sustainability. Econ. Manag. Financ. Mark. 2015 , 10 , 80–85. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ng, C. Intention to purchase on social commerce websites across cultures: A cross-regional study. Inf. Manag. 2013 , 50 , 609–620. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Kim, S.; Park, H. Effects of various characteristics of social commerce (s-commerce) on con-sumers’ trust and trust performance. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2013 , 33 , 318–332. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Sharma, S.; Crossler, R. Disclosing too much? Situational factors affecting information disclosure in social commerce environment. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2014 , 13 , 305–319. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Wallsten, S. The competitive effects of the sharing economy: How is Uber changing taxis. Technol. Policy Inst. 2015 , 22 , 1–21. [ Google Scholar ]

- Zhang, K.Z.; Benyoucef, M.; Zhao, S.J. Building brand loyalty in social commerce: The case of brand microblogs. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2016 , 15 , 14–25. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Wang, Y.; Hsiao, S.-H.; Yang, Z.; Hajli, N. The impact of sellers’ social influence on the co-creation of innovation with customers and brand awareness in online communities. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2016 , 54 , 56–70. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Akman, I.; Mishra, A. Factors influencing consumer intention in social commerce adoption. Inf. Technol. People 2017 , 30 , 356–370. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Hajli, N.; Sims, J.; Zadeh, A.H.; Richard, M.-O. A social commerce investigation of the role of trust in a social networking site on purchase intentions. J. Bus. Res. 2017 , 71 , 133–141. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Seo, A.; Jeong, J.; Kim, Y. Cyber Physical Systems for User Reliability Measurements in a Sharing Economy Environment. Sensors 2017 , 17 , 1868. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Tajvidi, M.; Richard, M.-O.; Wang, Y.; Hajli, N. Brand co-creation through social commerce information sharing: The role of social media. J. Bus. Res. 2018 , 121 , 476–486. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Kim, N.; Kim, W. Do your social media lead you to make social deal purchases? Consumer-generated social referrals for sales via social commerce. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2018 , 39 , 38–48. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Zhang, H.; Zhao, L.; Gupta, S. The role of online product recommendations on customer decision making and loyalty in social shopping communities. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2018 , 38 , 150–166. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Chen, Y.; Lu, Y.; Wang, B.; Pan, Z. How do product recommendations affect impulse buying? An empirical study on WeChat social commerce. Inf. Manag. 2018 , 56 , 236–248. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Geissinger, A.; Laurell, C.; Öberg, C.; Sandström, C. How sustainable is the sharing economy? On the sustainability connotations of sharing economy platforms. J. Clean. Prod. 2018 , 206 , 419–429. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Zhang, T.C.; Gu, H.; Jahromi, M.F. What makes the sharing economy successful? An empirical examination of competitive customer value propositions. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019 , 95 , 275–283. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Hsiao, M.-H. Influence of interpersonal competence on behavioral intention in social commerce through customer-perceived value. J. Mark. Anal. 2020 , 9 , 44–55. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Nadeem, W.; Khani, A.H.; Schultz, C.D.; Adam, N.A.; Attar, R.W.; Hajli, N. How social presence drives commitment and loyalty with online brand communities? the role of social commerce trust. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020 , 55 , 102136. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Abdelsalam, S.; Salim, N.; Alias, R.A.; Husain, O. Understanding Online Impulse Buying Behavior in Social Commerce: A Systematic Literature Review. IEEE Access 2020 , 8 , 89041–89058. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Xue, J.; Liang, X.; Xie, T.; Wang, H. See now, act now: How to interact with customers to enhance social commerce engagement? Inf. Manag. 2020 , 57 , 103324. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Esmaeili, L.; Mardani, S.; Golpayegani, S.A.H.; Madar, Z.Z. A novel tourism recommender system in the context of social commerce. Expert Syst. Appl. 2020 , 149 , 113301. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Sohn, J.W.; Kim, J.K. Factors that influence purchase intentions in social commerce. Technol. Soc. 2020 , 63 , 101365. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Bugshan, H.; Attar, R.W. Social commerce information sharing and their impact on consumers. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2020 , 153 , 119875. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Choi, Y. Sharing Economy for Sustainable Commerce. Int. J. E-Bus. Res. 2020 , 16 , 60–73. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Ebrahimi, P.; Hamza, K.A.; Gorgenyi-Hegyes, E.; Zarea, H.; Fekete-Farkas, M. Consumer Knowledge Sharing Behavior and Consumer Purchase Behavior: Evidence from E-Commerce and Online Retail in Hungary. Sustainability 2021 , 13 , 10375. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Rai, H.B.; Broekaert, C.; Verlinde, S.; Macharis, C. Sharing is caring: How non-financial incentives drive sustainable e-commerce delivery. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2021 , 93 , 102794. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Molinillo, S.; Aguilar-Illescas, R.; Anaya-Sánchez, R.; Liébana-Cabanillas, F. Social commerce website design, perceived value and loyalty behavior intentions: The moderating roles of gender, age and frequency of use. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021 , 63 , 102404. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Busalim, A.H.; Ghabban, F.; Hussin, A.R.C. Customer engagement behaviour on social commerce platforms: An empirical study. Technol. Soc. 2020 , 64 , 101437. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Yang, X. Exchanging social support in social commerce: The role of peer relations. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021 , 124 , 106911. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Ariesty, W.; Sari, R.K. The effect of information quality, trust and satisfaction to e-commerce customer loyalty in sharing Economy Activities. In Proceedings of the 7Th International Conference on Electrical, Electronics and Information Engineering (ICEEIE), Malang, Indonesia, 2 October 2021. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Jiang, G.; Liu, F.; Liu, W.; Liu, S.; Chen, Y.; Xu, D. Effects of information quality on information adoption on social media review platforms: Moderating role of perceived risk. Data Sci. Manag. 2021 , 1 , 13–22. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Su, B.-C.; Wu, L.-W.; Hsu, J.-C. Social commerce: The mediating effects of trust and value co-creation on social sharing and shopping intentions. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction, Málaga, Spain, 22–24 September 2021; pp. 131–142. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Hsieh, Y.-H.; Lo, Y.-T. Understanding Customer Motivation to Share Information in Social Commerce. J. Organ. End User Comput. 2021 , 33 , 1–26. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Da Costa, T.; Casais, B. Social Media and E-commerce. In Research Anthology on Social Media Advertising and Building Consumer Relationships ; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2022; pp. 1681–1702. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Liu, F.; Liu, S.; Jiang, G. Consumers’ decision-making process in redeeming and sharing behaviors toward app-based mobile coupons in social commerce. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2022 , 67 , 102550. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Xiang, H.; Chau, K.Y.; Iqbal, W.; Irfan, M.; Dagar, V. Determinants of Social Commerce Usage and Online Impulse Purchase: Implications for Business and Digital Revolution. Front. Psychol. 2022 , 13 , 837042. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Curty, R.G.; Zhang, P. Social Commerce: Looking back and forward. Proc. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2011 , 48 , 1–10. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Lam, H.K.; Yeung, A.C.; Lo, C.K.; Cheng, T. Should firms invest in social commerce? An integrative perspective. Inf. Manag. 2019 , 56 , 103164. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Hsu, K.K. AI City’s Solar Energy Collaborative Commerce and Sharing Economy ; ICEB Proceedings: Guilin, China, 2018. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ahmad, S.N.; Laroche, M. Analysing electronic word of mouth: A social commerce construct. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2017 , 37 , 202–213. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Cheng, X.; Gu, Y.; Shen, J. An integrated view of particularized trust in social commerce: An empirical investigation. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2018 , 45 , 1–12. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Bai, Y.; Yao, Z.; Dou, Y.F. Effect of social commerce factors on user purchase behaviour: An empirical investigation from renren. com. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2015 , 35 , 538–550. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Kong, Y.; Wang, Y.; Hajli, S.; Featherman, M. In Sharing Economy We Trust: Examining the Effect of Social and Technical Enablers on Millennials’ Trust in Sharing Commerce. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019 , 108 , 105993. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Baethge, C.; Klier, J.; Klier, M. Social commerce—State-of-the-art and future research directions. Electron. Mark. 2016 , 26 , 269–290. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Heinrichs, H. Sharing Economy: A Potential New Pathway to Sustainability. GAIA Ecol. Perspect. Sci. Soc. 2013 , 22 , 228–231. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Martin, C.J. The sharing economy: A pathway to sustainability or a nightmarish form of neoliberal capitalism? Ecol. Econ. 2016 , 121 , 149–159. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Leong, L.-Y.; Hew, T.-S.; Ooi, K.-B.; Chong, A.Y.-L. Predicting the antecedents of trust in social commerce—A hybrid structural equation modeling with neural network approach. J. Bus. Res. 2020 , 110 , 24–40. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Goyal, S.; Hu, C.; Chauhan, S.; Gupta, P.; Bhardwaj, A.K.; Mahindroo, A. Social Commerce. J. Glob. Inf. Manag. 2021 , 29 , 1–33. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Habibi, M.R.; Davidson, A.; Laroche, M. What managers should know about the sharing economy. Bus. Horiz. 2016 , 60 , 113–121. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Mody, M.; Suess, C.; Lehto, X. Going back to its roots: Can hospitableness provide hotels competitive advantage over the sharing economy? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019 , 76 , 286–298. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Zhai, W.; Chen, Y.; Wu, X.; Lin, H.; Zhou, Y. Antecedents and Outcomes of Social Commerce Information Sharing in China: From Multi-medium Marketing to Consumer Behaviour. High. Educ. Orient. Stud. 2021 , 1 , 57–70. [ Google Scholar ]

- Featherman, M.S.; Hajli, N. Self-Service Technologies and e-Services Risks in Social Commerce Era. J. Bus. Ethic 2015 , 139 , 251–269. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Wang, Y.; Herrando, C. Does privacy assurance on social commerce sites matter to millennials? Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019 , 44 , 164–177. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Williams, M.D. Social commerce and the mobile platform: Payment and security perceptions of potential users. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018 , 115 , 105557. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Chen, J.; Shen, X.L. Consumers’ decisions in social commerce context: An empirical investigation. Decis. Support Syst. 2015 , 79 , 55–64. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Chen, J.V.; Su, B.-C.; Widjaja, A.E. Facebook C2C social commerce: A study of online impulse buying. Decis. Support Syst. 2016 , 83 , 57–69. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Wongkitrungrueng, A.; Assarut, N. The role of live streaming in building consumer trust and engagement with social commerce sellers. J. Bus. Res. 2018 , 117 , 543–556. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Baghdadi, Y. From E-commerce to Social Commerce: A Framework to Guide Enabling Cloud Computing. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2013 , 8 , 5–6. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Shanmugam, M.; Jusoh, Y.Y. Social commerce from the information systems perspective: A systematic literature review. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computer and Information Sciences (ICCOINS), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 3–5 June 2014; pp. 1–6. [ Google Scholar ]

- Li, C.Y.; Ku, Y.C. The power of a thumbs-up: Will e-commerce switch to social commerce? Inf. Manag. 2018 , 55 , 340–357. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Aladwani, A. A quality-facilitated socialization model of social commerce decisions. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2018 , 40 , 1–7. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Wu, Y.L.; Li, E.Y. Marketing mix, customer value, and customer loyalty in social commerce: A stimulus-organism-response perspective. Internet Res. 2018 , 28 , 74–104. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Lin, X.; Wang, X.; Hajli, N. Building E-Commerce Satisfaction and Boosting Sales: The Role of Social Commerce Trust and Its Antecedents. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2019 , 23 , 328–363. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Hu, T.; Dai, H.; Salam, A. Integrative qualities and dimensions of social commerce: Toward a unified view. Inf. Manag. 2018 , 56 , 249–270. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Xiang, L.; Zheng, X.; Lee, M.K.; Zhao, D. Exploring consumers’ impulse buying behaviour on social commerce platform: The role of parasocial interaction. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2016 , 36 , 333–347. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Zhang, M.; Guo, L.; Hu, M.; Liu, W. Influence of customer engagement with company social networks on stickiness: Mediating effect of customer value creation. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2017 , 37 , 229–240. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Sheikh, Z.; Islam, T.; Rana, S.; Hameed, Z.; Saeed, U. Acceptance of social commerce framework in Saudi Arabia. Telemat. Inform. 2017 , 34 , 1693–1708. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Shen, X.L.; Li, Y.J.; Sun, Y.; Chen, Z.; Wang, F. Understanding the role of technology attractiveness in promoting social commerce engagement: Moderating effect of personal interest. Inf. Manag. 2019 , 56 , 294–305. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Fu, S.; Yan, Q.; Feng, G.C. Who will attract you? Similarity effect among users on online purchase intention of movie tickets in the social shopping context. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2018 , 40 , 88–102. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Lăzăroiu, G.; Neguriţă, O.; Grecu, I.; Grecu, G.; Mitran, P.C. Consumers’ Decision-Making Process on Social Commerce Platforms: Online Trust, Perceived Risk, and Purchase Intentions. Front. Psychol. 2020 , 11 , 796. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Friedrich, T. On the Factors Influencing Consumers’ Adoption of Social Commerce—A Review of the Empirical Literature. Pac. Asia J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2016 , 8 , 2. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Kim, S.; Sun, K.; Kim, D. The Influence of Consumer Value-Based Factors on Attitude-Behavioural Intention in Social Commerce: The Differences between High- and Low-Technology Experience Groups. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2013 , 30 , 108–125. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Abed, S.S.; Dwivedi, Y.K.; Williams, M.D. Social media as a bridge to e-commerce adoption in SMEs: A systematic literature review. Mark. Rev. 2015 , 15 , 39–57. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Goh, K.N.; Chen, Y.Y.; Daud, S.C.; Sivaji, A.; Soo, S.T. Designing a Checklist for an E-Commerce Website Using Kansei Engineering. Adv. Vis. Inform. 2013 , 37 , 483–496. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Chen, A.; Lu, Y.; Wang, B. Customers’ purchase decision-making process in social commerce: A social learning perspective. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2017 , 37 , 627–638. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Liu, H.; Chu, H.; Huang, Q.; Chen, X. Enhancing the flow experience of consumers in China through interpersonal interaction in social commerce. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016 , 58 , 306–314. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Zheng, X.; Zhu, S.; Lin, Z. Capturing the essence of word-of-mouth for social commerce: Assessing the quality of online e-commerce reviews by a semi-supervised approach. Decis. Support Syst. 2013 , 56 , 211–222. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Chung, N.; Song, H.G.; Lee, H. Consumers’ impulsive buying behaviour of restaurant products in social commerce. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2017 , 29 , 709–731. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Saundage, D.; Lee, C.Y. Social commerce activities—A taxonomy, in ACIS 2011: Identifying the information systems discipline. In Proceedings of the 22nd Australasian Conference on Information Systems, ACIS, Sydney, Australia, 30 November–2 December 2011. [ Google Scholar ]

- Wang, X.; Lin, X.; Spencer, M.K. Exploring the effects of extrinsic motivation on consumer behaviours in social commerce: Revealing consumers’ perceptions of social commerce benefits. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019 , 45 , 163–175. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Osatuyi, B.; Qin, H. How vital is the role of effect on post-adoption behaviors? An examination of social commerce users. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2018 , 40 , 175–185. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Lin, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, X. Social commerce research: Definition, research themes and the trends. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2017 , 37 , 190–201. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Wang, X.; Wang, H.; Zhang, C. A Literature Review of Social Commerce Research from a Systems Thinking Perspective. Systems 2022 , 10 , 56. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Liao, S.-H.; Widowati, R.; Hsieh, Y.-C. Investigating online social media users’ behaviors for social commerce recommendations. Technol. Soc. 2021 , 66 , 101655. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Lina, L.F.; Ahluwalia, L. Customers’ impulse buying in social commerce: The role of flow experience in personalized advertising. J. Manaj. Maranatha 2021 , 21 , 1–8. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Hu, X.; Chen, Z.; Davison, R.M.; Liu, Y. Charting consumers’ continued social commerce intention. Internet Res. 2021 , 32 , 120–149. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Dinulescu, C.C.; Visinescu, L.L.; Prybutok, V.R.; Sivitanides, M. Customer Relationships, Privacy, and Security in Social Commerce. J. Comput. Inf. Syst. 2021 , 62 , 642–654. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Huang, Z.; Benyoucef, M. From e-commerce to social commerce: A close look at design features. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2013 , 12 , 246–259. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

Click here to enlarge figure

| Timeline | Key Topics |

|---|---|

| 2010 | Value from S-Commerce networks [ , ] |

| 2011 | Issues of trust in S-Commerce [ , , ] |

| 2012 | User participation on S-Commerce sites across cultures [ , , ] Consumers’ trust in S-Commerce [ ]; S-Commerce adoption model [ ] |

| 2013 | Online consumer behaviour in S-Commerce across cultures [ , ] Online trust and value in S-Commerce [ , ] |

| 2014 | Trust and privacy concerns [ ] Information disclosure in S-Commerce environment [ ] |

| 2015 | Consumer perception of knowledge-sharing (collaborative consumption) [ , , , , ] The shift of power from dealers to purchasers (Social Exchange Perspective) [ , ] |

| 2016 | New technologies in commerce and sharing economy [ ] Trust and risks in the sharing economy [ , , ] Developing brand loyalty in sharing commerce [ , ] |

| 2017 | Buyer intentions to engage in sharing commerce [ , , ] The role of personal privacy in the sharing economy [ , ] Understanding media in the sharing economy [ ] User reliability measuring in a sharing economy environment [ , ] |

| 2018 | Opportunities and challenges of sharing economy [ ] Why people engage in the sharing economy [ , ] Brand co-creation through S-Commerce information sharing [ ] Role of online merchandise suggestions on buyer decision making and loyalty in social shopping communities [ , ] |

| 2019 | Using S-Commerce information sharing for value co-creation [ ] Shared behaviour and information sharing in the E-Commerce age [ ] How do merchandise suggestions affect impulse purchasing? [ ] How sustainable is the sharing economy? [ ] The sharing economy and its consequences for sustainability [ ] |

| 2020 | Consumer behaviour [ , , ] Social commerce engagement [ ] Social support through recommendations [ ] Factors influencing purchase intentions [ ] Impact of information sharing activities and learning activities [ , ] |

| 2021 | Consumer behaviour [ , , ] Social support factors [ , ] Information quality on social commerce platforms [ , ] Value co-creation by stakeholders [ , ] |

| 2022 | Consumer behaviour [ , , ] |

| MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

Share and Cite

Attar, R.W.; Almusharraf, A.; Alfawaz, A.; Hajli, N. New Trends in E-Commerce Research: Linking Social Commerce and Sharing Commerce: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2022 , 14 , 16024. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142316024

Attar RW, Almusharraf A, Alfawaz A, Hajli N. New Trends in E-Commerce Research: Linking Social Commerce and Sharing Commerce: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability . 2022; 14(23):16024. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142316024

Attar, Razaz Waheeb, Ahlam Almusharraf, Areej Alfawaz, and Nick Hajli. 2022. "New Trends in E-Commerce Research: Linking Social Commerce and Sharing Commerce: A Systematic Literature Review" Sustainability 14, no. 23: 16024. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142316024

Article Metrics

Article access statistics, supplementary material.

ZIP-Document (ZIP, 327 KiB)

Further Information

Mdpi initiatives, follow mdpi.

Subscribe to receive issue release notifications and newsletters from MDPI journals

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Research on e-commerce data standard system in the era of digital economy from the perspective of organizational psychology.

- Henan University School of Law/Intellectual Property School, Institute of Civil and Commercial Law of Henan University, Kaifeng, China

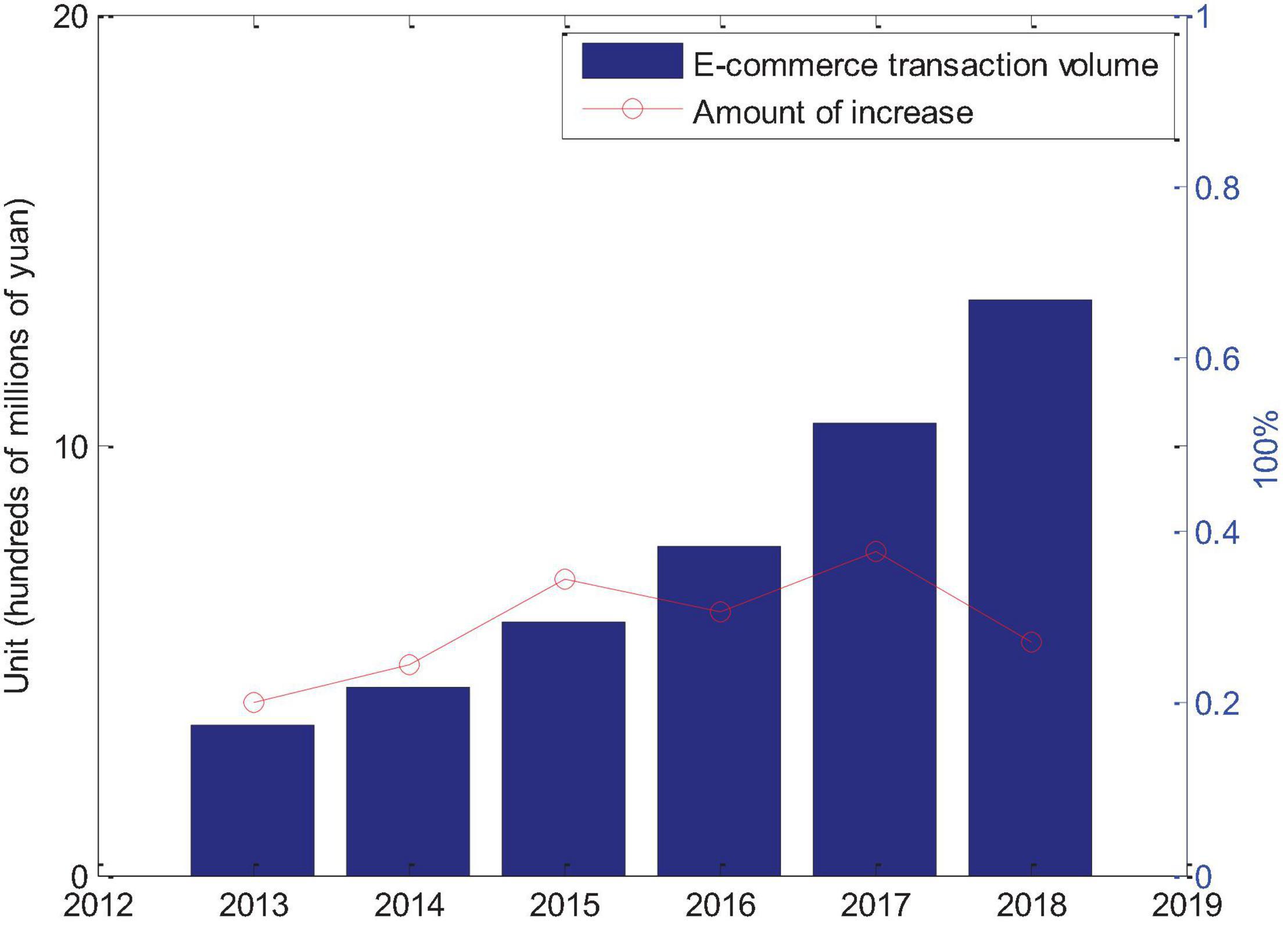

With the rapid development of technology and the economy, the expansion of the network has had a huge impact on the rapid expansion of the industrial agglomeration e-commerce industry, as well as ensuring the shopping experience of consumers. The rapid expansion of industrial cluster e-commerce has avoided precisely the limitations of logistical bottlenecks. Current networks and modern information technologies can provide good support and maintain a huge growth potential. In addition, digital technologies such as multimedia are becoming increasingly important in industry cluster marketing, and the concept of industry cluster e-commerce models is gaining more and more attention from companies. However, virtual e-commerce systems under industrial clusters have not been well researched in the existing studies. In this paper, through extensive research, literature reading and website browsing statistics, the virtual e-commerce models of different industrial agglomerations are studied. Firstly, the concept of big data and the processing of big data are given. Secondly, the concept of industrial agglomeration and the relationship between industrial agglomeration and e-commerce are analyzed. The basic number of domestic Internet users in the last 10 years is also counted, proving that the expansion of the Internet has led to a substantial growth of Internet users in the country and that e-commerce plays a significant role in the future of business activities. Finally the study concludes that different e-commerce models have different performance and roles in industrial agglomeration e-commerce and cannot be generalized. Instead, it is not good and can only develop different industrial agglomeration e-commerce models according to different environments.

Introduction

In the long history of mankind, when people explore and discover the law of unknowns, they rely mainly on reasoning methods such as experience, theory, and assumptions, which are largely influenced by personal prejudice. Later, people invented mathematical tools such as statistics, sampling, and probability. Through careful design and extraction methods, a small number of data samples were obtained to infer the whole picture of things. Therefore, there are often deviations and distortions in understanding things. According to Victor Meyer, thanks to advances in technology, people can access all the data of a research object and understand things from different angles. Analyze the different dimensions of all data from an incomprehensible perspective. With the rapid expansion of electronic signal technology, e-commerce ( Anam et al., 2017 ; Irene, 2018 ) has changed an inevitable outcome of the expansion of the times and is also a form of transaction that adapts to market demand. The expansion of e-commerce is very gratifying. After more than 10 years of expansion, B2C ( Gui et al., 2019 ) and C2C ( Navarro-Méndez et al., 2017 ) have become the main mode of e-commerce in China. The model has the vitality of information transparency, flexible trading, high efficiency and price advantage. With the rapid propagate of the Net, by the end of 2018, the number of Internet users in China reached 1.08 billion. A great deal of Internet users has established a good customer base for the expansion of e-commerce. In addition, the continuous improvement of relevant laws and regulations and the maturity of information technology have laid the foundation for the expansion of e-commerce. By combining big data with e-commerce, e-commerce based on big data will become the main research direction of the future society ( Nik et al., 2017 ).

Mega data (big data) ( Wang et al., 2017 ; Zhou et al., 2017 ) is what we often call big data, also known as massive data. Giant data is actually a data repository. In this era, it can be used as an asset. After professional analysis, the efficiency is higher, the amount of data is larger, the data is diverse, and the sources are different, most of which are instantaneous. The communication information generated during the sales process is also generated instantaneously. For example, customer basic data, website clicks, network data, etc., are all counted in big data, some are part of customer information, and some are not counted. In the 1980s, some scholars predicted big data and believed that big data will surely ignite the new wave of the third technological revolution. Since 2009, “Big Data” has made great progress with the rapid expansion of e-commerce and cloud computing ( Liu et al., 2018 ) and is gradually becoming well known to the public. As can be seen from the latest data, the growth of data on the Internet and mobile Internet has gradually approached Moore’s Law, and global data and information have been created “over doubling every 18 months” over the years. The application of big data in industrial agglomeration ( Xuan, 2017 ; Nádudvari et al., 2018 ) e-commerce is also getting more and more wide-ranging.

Industrial clusters ( Cao et al., 2017 ; Wang and Yu, 2017 ) have a long history as well-functioning organizations. At the end of the 19th century, Marshall creatively defined the concept of “industry zone,” that is, industrial clusters. He defines “industrial zone” as the agglomeration of certain industrial zones, which is determined by two factors: history and natural resources. There are many companies of different sizes in the area. There is a close relationship between cooperation and competition, which gradually affects the integration of industrial clusters and society. According to Marshall, the reason for the emergence of “industry zones” in the region is a combination of inside and outside factors. Later, Weber believed that the phenomenon of industrial clusters was the result of regional and geographic influences. Companies with regional and geographic advantages have established close partnerships through partnerships with other related companies. Establish complex and close internal network relationships, achieve the aggregation of enterprises in a specific region, and then develop into industrial clusters. In recent decades, academia and industry have been highly involved in the expansion of synergies between industrial clusters and supply chains. They actively used industrial clusters and supply chains in corporate management ( Heiner and Marc, 2018 ) and achieved remarkable results. Clusters and supply chains can provide a competitive advantage for businesses. However, with the rapid expansion of e-commerce, industrial clusters are faced with the dilemma of optimizing transformation and upgrading. The traditional approach to supply chain management is far from meeting the needs of users. Therefore, it is a major problem to study how e-commerce uses the first-mover advantage to promote synergy between industrial clusters and supply chains.

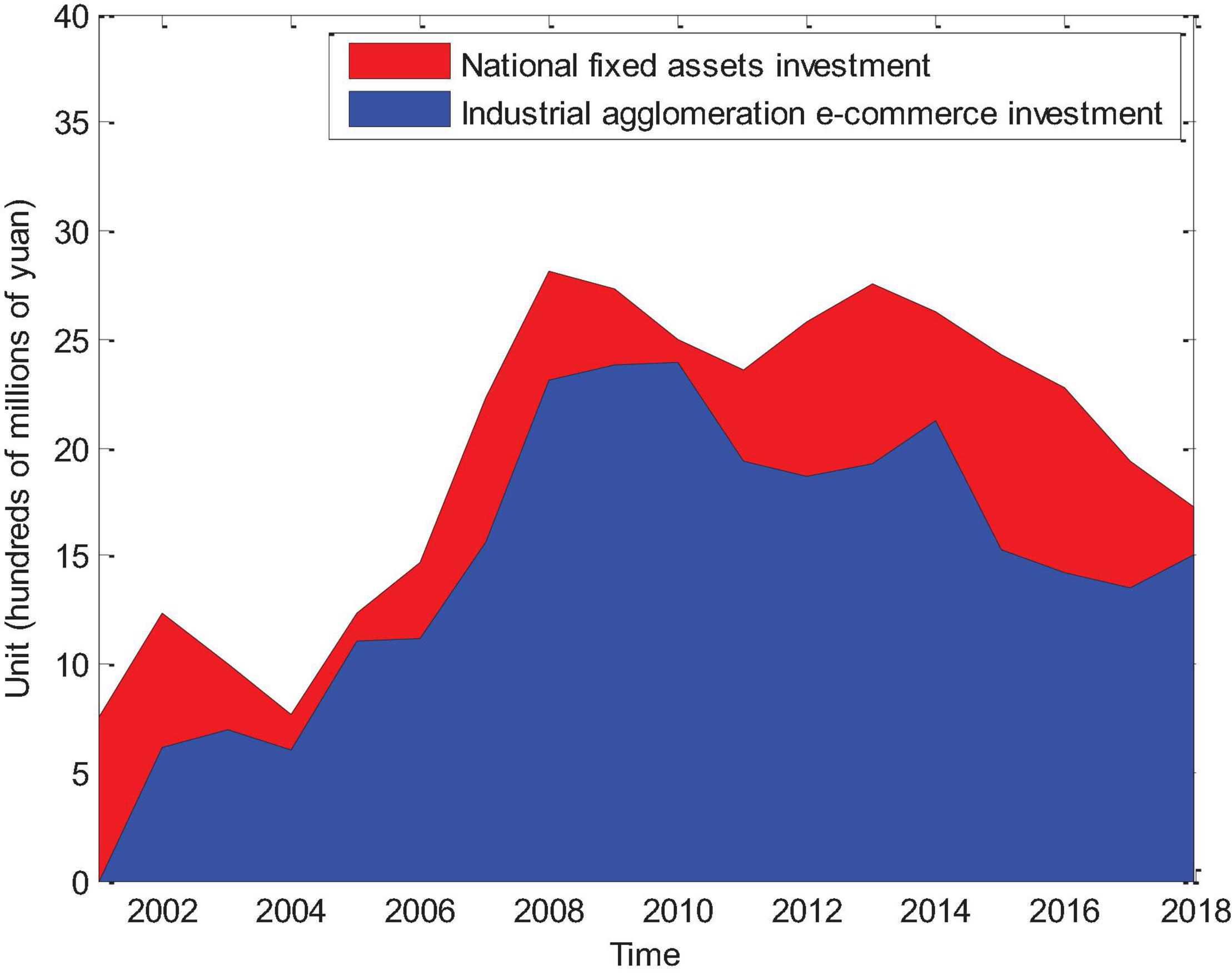

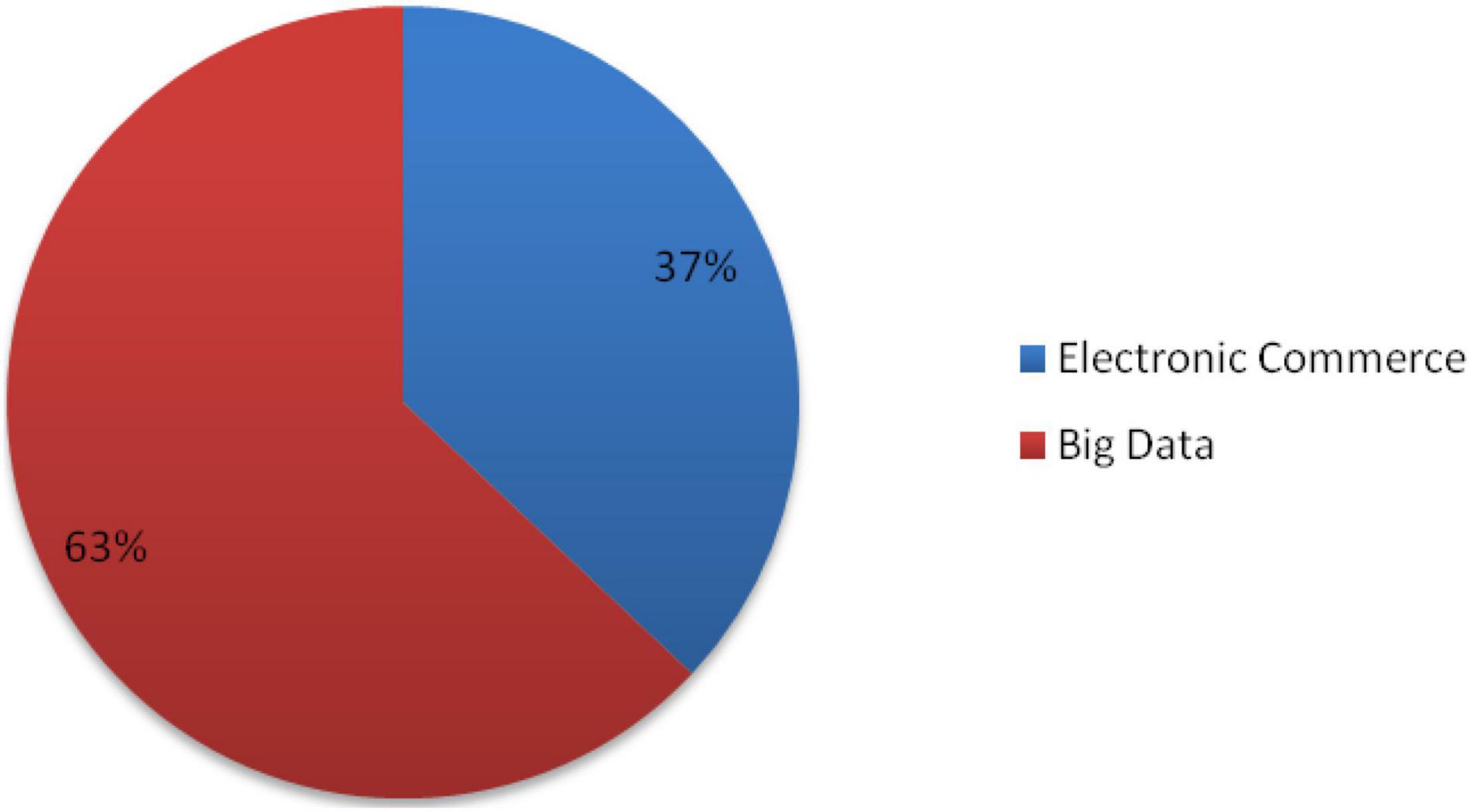

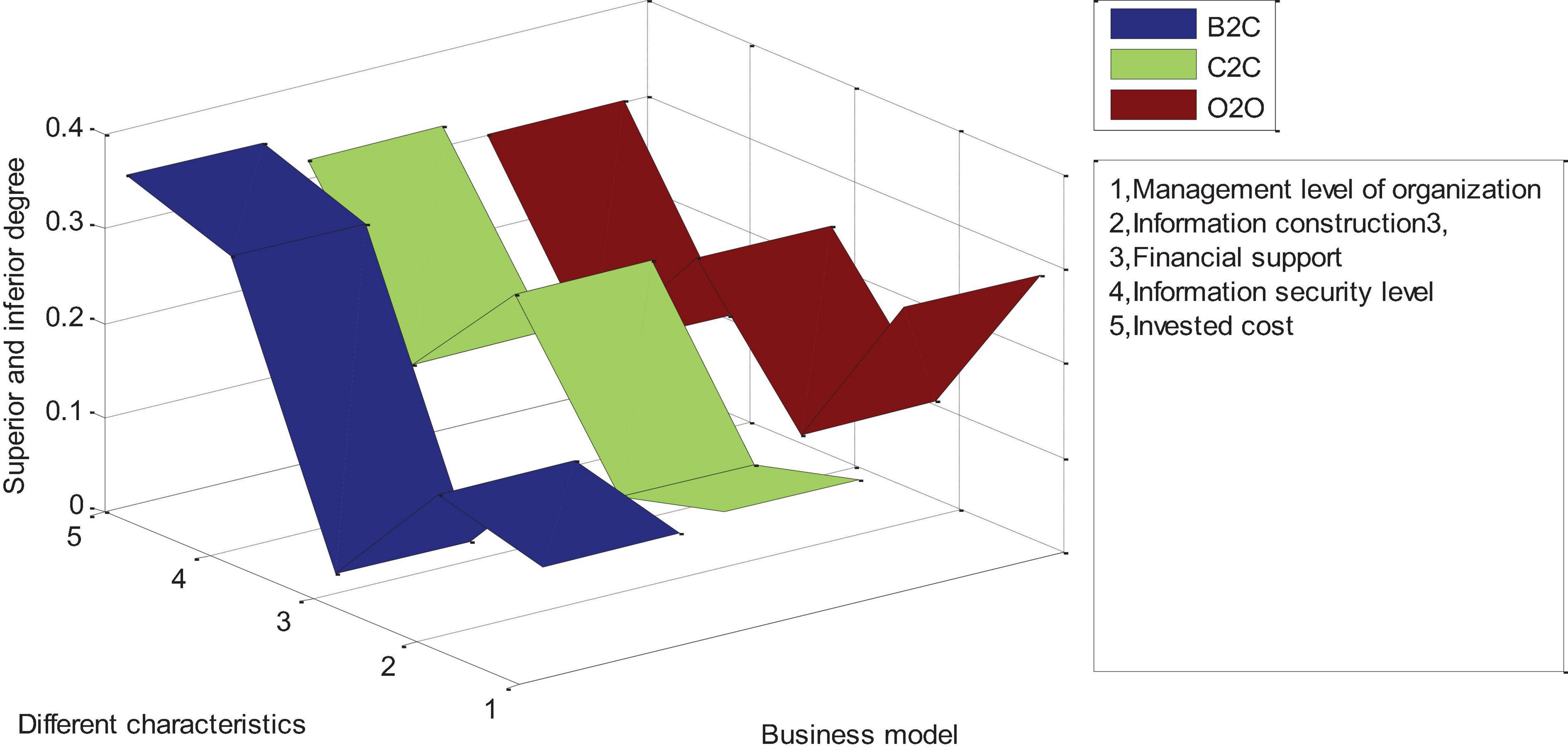

For the core enterprises in the industrial agglomeration, because of their own advantages in terms of capital and technology, as well as a number of strong manufacturers and suppliers, so that the online market established by the enterprise has a large number of members and good prospects for development, and attracts some new members to join, once the establishment of close cooperation in this online market, its members want to move to other online market will be very expensive, so that the core enterprises in the online market to consolidate their existing position ( Yang et al., 2022 ; Han et al., 2021 ; Setiawan et al., 2022 ; Suska, 2022 ; Yu et al., 2022 ). Therefore, e-commerce has developed into a new opportunity to enhance the synergy of China’s supply chain and enhance its competitive advantage. In the end, this paper starts from the business reality of big data-based industry agglomeration e-commerce, fully considers the dependence of industrial agglomeration area on e-commerce in the era of big data, and studies the relationship between the concept of industrial agglomeration and the relationship between e-commerce and industrial agglomeration. Therefore, with the support of big data, this paper analyses the number of netizens, the level of economic expansion, etc., and compares the impact of e-commerce yield and industrial agglomeration e-commerce investment and big data and e-commerce on industrial agglomeration. The merits and demerits of e-commerce in the type of industrial agglomeration, and the expectation is to provide a summary and reference for the industry to gather e-commerce enterprises to obtain competitive advantages in the market competition.

Big Data and E-Commerce Related Definitions

Big data overview.

With the popularity of the Internet and the rapid expansion of information technology, the signal age is making a subtle transition to the big data era. The network has turned into an integral part of people’s production and life. While enjoying the convenience brought by the information network, people also continuously feedback and input information to the network. Some information involves individual privacy, and network information security has become one of the hot topics of research. At present, the social network information security problem is becoming more and more obvious, the conventional information security software has been unable to deal with the endless information security problem, the network society urgently needs a new information technology to protect the increasingly huge information assets, and the big data technology has stronger insight, more scientific decision-making power and more accurate process optimization ability compared with the conventional software. Must be able to play a positive effect.

Professor Victor is known as the “Big Data Prophet.” Big data also called huge amount of data, refers to the amount of data involved is so large that it cannot be captured, managed, processed and collated in a reasonable time through the human brain or even mainstream software tools to help enterprises to make more positive decisions. By analyzing big data, we can draw conclusions that cannot be obtained in the case of small data. The big data we usually talk about is more about getting valuable information in a short time by quickly analyzing a large amount of data.

Big Data Analysis Process and Features

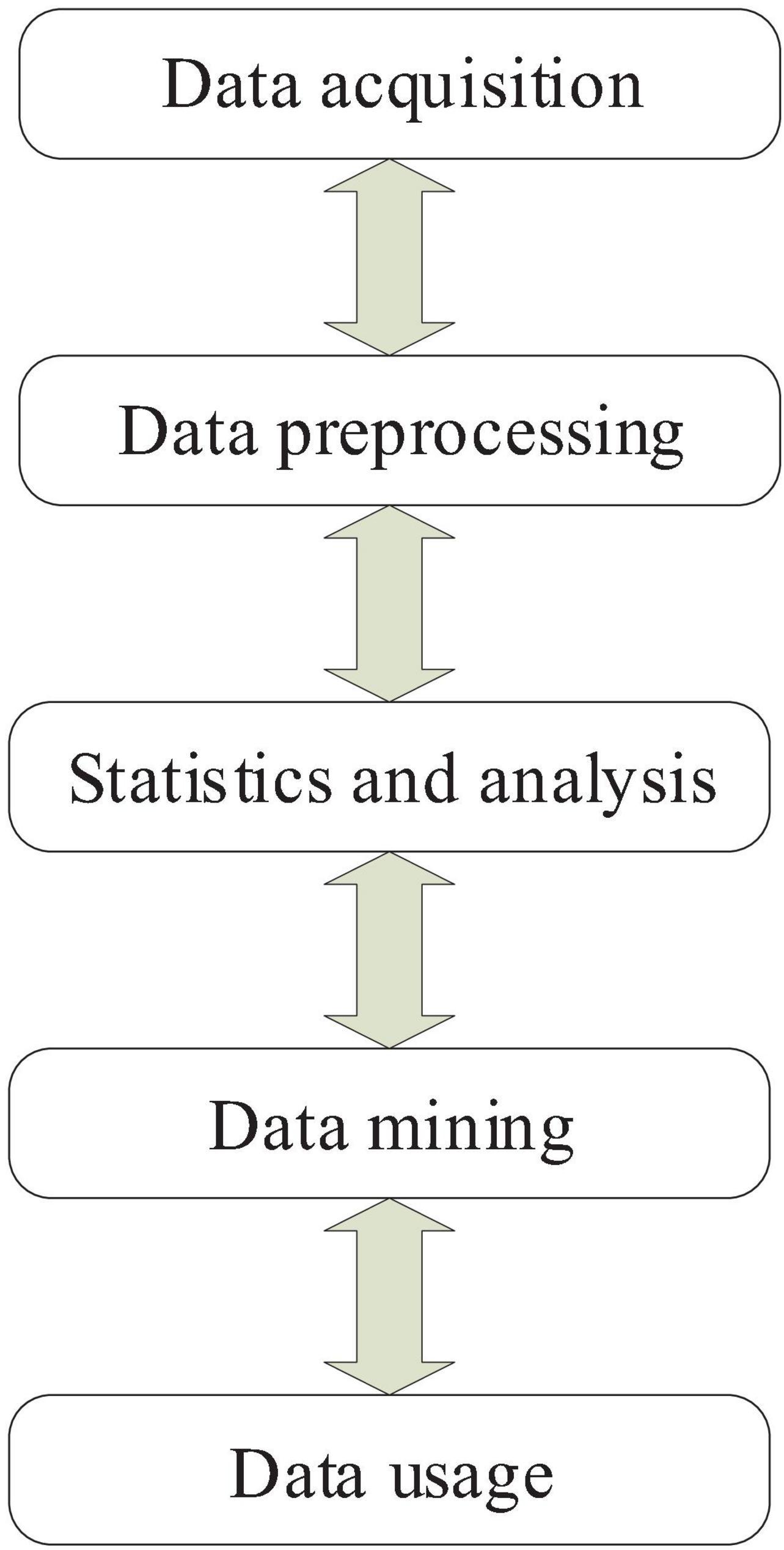

In general, there are many methods for analyzing big data, and in theory it is still in the exploration stage, but no matter what kind of big data analysis method follows the basic process, the flow chart is shown in Figure 1 .

Figure 1. Big data processing flow.

The first process of big data analysis is acquisition. Big data sampling ( Bivand and Krivoruchko, 2018 ; Cohen et al., 2018 ) means collect information collection platforms to collect users or other data. In the process of big data collection, the main problem is that the amount of data is huge, the amount of collection is large, and the data collection point is large. A large amount of data needs to be collected at the same time. Therefore, in the process of collecting big data, it is necessary to establish a larger database and how to further design the reasonable use and distribution of the database.

The second step is import and beneficiate. This mainly means that invalid information, redundant information and low-value information are excluded after the first information collection is completed, so it is necessary to execute the data before processing. Effective screening and brief analysis, and then import the resulting preliminary filtering information into another large database, this step is mainly to pre-process the big data.

The third step in big data processing is to perform statistics and analysis. This process is a process of further refinement of big data, analyzing and screening valid data, and performing statistical processing to obtain effective information.

The fourth step in big data is to deal with the mining ( Rezaei-Hachesu et al., 2017 ; Fan et al., 2018 ; Svefors et al., 2019 ) process. Unlike the above process, there is no clear path or statistical analysis method for big data information mining. It is mainly used for databases that collect large amounts of data and use various algorithms for calculations, so it is complex data. Try to get predictions or get other valid conclusions. The statistical analysis and mining process of big data is considered to be a key process for transforming data from data into value space and value sources in the process of big data information processing.

The final step is using information obtained from big data. In particular, it can be used for business decision behavior predictions, while sales companies can provide accuracy. Marketing, achieving service conversion, etc. The application prospect of big data is very broad, and it has a good application prospect in transportation, sales management, economic research and forecasting.

At present, there is no authoritative unified standard. At present, the “4V” function of big data has been widely recognized.

First, the data size is huge. In 2012, the world produced about 2.7 billion GB of data per day, the amount of data per day equals the sum of all stored data in the world before 2000. Baidu must process more than 70,000 GB of search data per minute, and Alipay generates an average of 73,000 transactions per minute. Traffic flow monitoring systems and video capture systems can generate large amounts of video data at any time. Temperature sensors in greenhouses and various detectors in the factory are also big data manufacturers. It can be said that the amount of data we generate per minute is unimaginable. Now, the scale of data that big data needs to process continues to grow, reaching orders of magnitude unimaginable in small data.

Second, there is a wide variety of data (Variety). In big data, in addition to the ever-increasing data size, the types of data that people need to deal with are beginning to emerge. The various data types are very numerous and very strange, and only a few can be handled using traditional techniques. Some are unstructured data that traditional technologies cannot handle, and this trend will be long-term, with unstructured data accounting for 90% of all data over the next decade. For example, Tudou’s video library, photos on social networking sites, records, etc., even include RFID status, mobile operator call history, video surveillance video, Weibo and status posted on WeChat. The size, format, and type of data from various sources may vary. Existing data processing techniques are useless and can cause significant difficulties when performing large amounts of processing.

Third, value is difficult to mine. The first two features show that the amount of data and data types in big data are amazing. Faced with a large amount of data, in order to mine hidden “treasures,” the analysis and processing of powerful cloud computing systems is only one aspect, not even the main one. How to analyze big data from the perspective of innovation according to needs, what to use big data ideas to examine big data to explore unimaginable economic and social values. In other words, only the combination of technology and innovation can unlock the value of big data. Otherwise, no amount of data will be useful.

Fourth, the processing speed is high (Velocity). This is the most significant feature of the big data era, unlike the era of small data and the era of probability and statistics. In traditional economic censuses, censuses and other areas, data can be tolerated for days or even a year, as the data obtained at this time still makes sense. Moreover, due to technical limitations, the collected data has been lagging behind, and the structure of statistical analysis is lagging behind, but it must be accepted. Data generation and collection is very fast, and the amount of data is growing all the time. With advanced technology, people can collect data in real time. But in most cases, if you don’t process the data in time, the advanced collection and sorting methods will be meaningless and you won’t need big data. For example, IBM proposed the concept of “big data-level stream computing,” which is designed for real-time analysis of data and results to increase practical value. Therefore, timely and fast processing of data and results is the most important feature of big data.

This is the most significant feature of the big data, unlike the era of small data and the era of probability and statistics. Due to technical limitations, the collected data is backward, and the structure of statistical analysis is also backward, but it must be accepted. Data generation and collection is very fast, and the amount of data has been growing. With advanced technology, people can collect data in real time. But in most cases, if you don’t process the data in time, the advanced collection and sorting methods will be meaningless. For example, IBM proposed the concept of “big data-level stream computing,” which aims to analyze data and results in real time to increase practical value. Therefore, timely and fast processing of data and results is the most significant feature of big data.

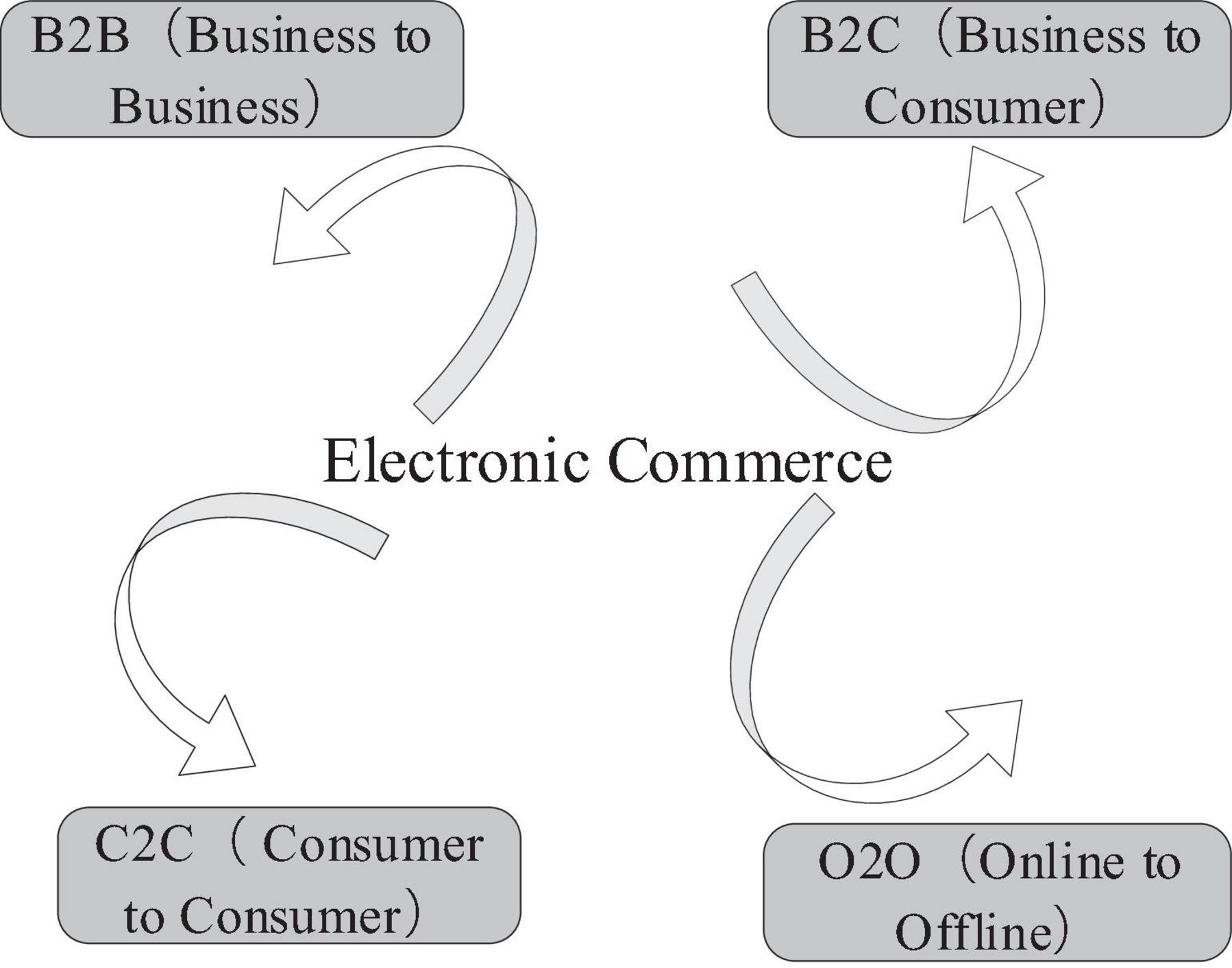

E-Commerce Concept

E-commerce generally refers to Internet technology, based on browser/server applications, through the Internet platform, buyers and sellers through various trade activities to achieve consumer online shopping, online payment and new business activities of various business activities and other models. The expansion history of e-commerce has a close relationship with the progress of computer network technology. E-commerce includes many models, such as B2B ( Ning et al., 2018 ) (Business to Business), B2C (Business to Consumer), C2C (Consumer to Consumer), and O2O (Online to Offline). The main centralized e-commerce model is shown in Figure 2 .

Figure 2. Main e-commerce model.

This article focuses on C2C ( Sukrat and Papasratorn, 2018 ) e-commerce. C2C e-commerce refers to a network service provider that uses computer and network technology to provide e-commerce platforms and transaction processes to users in a paid or non-paid manner. Allow both parties to conduct online transactions on their platform. The two sides of the transaction are mainly individual users, and the trading method is based on bidding and bargaining. Like B2B and B2C, C2C is also a basic e-commerce transaction model. In real life, it is similar to the “small commodity wholesale market.” There are many self-employed people in a website, and the website’s role in e-commerce is equivalent to the “market manager” in actual market transactions. At the same time, in order to promote smooth transactions between buyers and sellers, C2C e-commerce provides a series of support services for both parties. For example, in cooperation with market information collection, credit evaluation systems and various payment methods have been established. Due to the rapid expansion of e-commerce, industrial agglomeration has become more impressive. The most prominent performance of industrial agglomeration is the industrial concentration of “Internet + traditional industries” such as “Taobao Village.” C2C is the mainstream of this e-commerce business model. C2C e-commerce “Taobao Village” is a product based on urban and rural expansion in China. It has Chinese characteristics and is a “Chinese product.” This is both a theoretical issue and a very real social phenomenon. The Chinese government has put forward the “Internet+” proposal. With the expansion of China’s strategic emerging industries, “Internet + traditional industries” will become a shortcut for China’s backward regions to seek expansion, which can shorten the time required for expansion, making C2C e-commerce a “hometown of Taobao.” Therefore, in order for the industry to complete transactions, an e-commerce platform and online and offline resources and services are needed. It can be said that the C2C model is an e-commerce model that is very suitable for industrial agglomeration. The biggest advantage of the C2C e-commerce model is that it can produce and deliver enterprise products or services on demand, so that enterprises can quickly develop into large enterprises, and the C2C e-commerce model provides consumers with cheap and affordable purchases. Product and service platforms enable businesses and consumers to achieve a win-win situation.

In traditional market transactions, the delivery of goods from producers to stores requires warehouse storage, vehicle transportation, etc., which increases inventory costs and transportation costs, resulting in increased transaction costs. Unlike real-world trading, since e-commerce joins the virtual network, both buyers and sellers trade through the e-commerce platform, so there is no need for face-to-face communication. This form saves the seller’s transaction costs, including physical store and merchandise inventory and transportation costs. At the same time, buyers can also shop without going out, and can quickly compare products of different merchants through the network, which allows buyers to get more information, more efficient and lower cost. C2C e-commerce uses Internet communication channels based on open standards. Compared with traditional communication methods (such as mail, fax, newspaper, radio, and television), communication costs are greatly reduced.

Industry Agglomeration Virtual E-Commerce

Industrial cluster concept.

Industrial clusters attract the attention of many scholars by attracting resources, economies of scale, knowledge learning and innovation, saving transaction costs, and improving cooperation efficiency. Many mathematicians have studied the composition, characteristic mechanism, and identification criteria of industrial clusters through theoretical derivation, model construction, structural equations, and case studies, and elaborated and summarized the concept of industrial clusters. The definition of industrial agglomeration is that in a relatively limited space of a certain area, geographically adjacent or different geographical entities closely related to relevant institutions and government agencies spontaneously gather together, called industrial clusters. The division of labor between entities and continuous cooperation and innovation have formed a complex cluster network, providing environmental and technical support. The difference is that industrial clusters can adapt to economic expansion, and further transformation and upgrading will form a new industrial cluster model. At the same time, mutual trust, mutual decision-making, and close cooperation have created the greatest value and benefits for the industry. Finally, for the measurement and acquisition of industrial clusters, combined with the practical significance of empirical research, the measurement of industrial clusters is unified by the concentration of specific industries, that is, specific industries. A measure of the spontaneous aggregation of related entities or institutions in a particular industry in the region. If the total quantity or total capacity reaches the previous unified level, it indicates that there is an industrial cluster in the area.

The Relationship Between E-Commerce and Industrial Clusters

With the rise and prosperity of e-commerce, the new business organization system breaks the regional and spatial barriers, promotes the use of e-commerce and partners, establishes synergy and sharing mechanisms, and continuously meets the needs of users. Proactively improve user experience and satisfaction. In addition, e-commerce platforms and logistics platforms are increasingly used in new business models. Although these platforms are very different, the role of the company cannot be underestimated. The platform typically includes several key functional modules such as trading markets, logistics platforms, enterprise services, cluster information, and corporate communities. Cluster companies can conduct informal technology and information exchange on the platform. Through the construction of an e-commerce platform, industrial cluster enterprises can share market conditions, the latest industry technologies, and related industry information in real-time and quickly, creating greater economic benefits for enterprises. This close partnership helps industry clusters increase trust and mutual benefit. In short, e-commerce applications can help industrial clusters effectively integrate regional resources, meet market demands promptly, expand clusters, and increase the level of collaboration and competitiveness of enterprises within the cluster. Currently, the introduction of e-commerce applications has further promoted the expansion of supply chain coordination. As an effective spatial organization model, industrial clusters play an increasingly important role in improving the overall economic level of the region and optimizing the allocation of industrial resources. The rapid expansion of industrial clusters provides natural conditions for the expansion of enterprises, between enterprises and between supply chain members. Similar companies continue to gather, and upstream and downstream companies in the supply chain are also gathered to promote the use of e-commerce. A deeper impact on the synergy of the supply chain. Therefore, for the sake of strengthening the application of e-commerce. Based on continuous research by many scholars, it is further proved that the rapid expansion of industrial clusters promotes the coordinated management of supply chains.