Featured Topics

Featured series.

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Explore the Gazette

Read the latest.

A Chekhov play relatable to Americans today

Gain without pain

Everything, everywhere, all at once (kind of)

Images courtesy of John Patton, Ed Hagen, Samuel Mehr, Manvir Singh, and Luke Glowacki

Music everywhere

Comprehensive study explains that it is universal and that some songs sound ‘right’ in different social contexts, all over the world

Jed Gottlieb

Harvard Correspondent

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow wrote, “Music is the universal language of mankind.” Scientists at Harvard have just published the most comprehensive scientific study to date on music as a cultural product, which supports the American poet’s pronouncement and examines what features of song tend to be shared across societies.

The study was conceived by Samuel Mehr, a fellow of the Harvard Data Science Initiative and research associate in psychology, Manvir Singh, a graduate student in the Department of Human Evolutionary Biology, and Luke Glowacki, formerly a Harvard graduate student and now a professor of anthropology at Pennsylvania State University.

They set out to address big questions: Is music a cultural universal? If that’s a given, which musical qualities overlap across disparate societies? If it isn’t, why does it seem so ubiquitous? But they needed a data set of unprecedented breadth and depth. Over a five-year period, the team hunted down hundreds of recordings in libraries and private collections of scientists half a world away.

“We are so used to being able to find any piece of music that we like on the internet,” said Mehr, who is now a principal investigator at Harvard’s Music Lab . “But there are thousands and thousands of recordings buried in archives. At one point, we were looking for traditional Celtic music and we found a call number in the [Harvard] library system and librarian told us we needed to wait on the other side of the library because there was more room over there. Twenty minutes later this poor librarian comes out with a cart of about 20 cases of reel-to-reel recordings of Celtic music.”

Mehr added those reel tapes to the team’s growing discography, combining it with a corpus of ethnography containing nearly 5,000 descriptions of songs from 60 human societies. Mehr, Singh, and Glowacki call this database The Natural History of Song .

Their questions were so compelling that the project rapidly grew into a major international collaboration with musicians, data scientists, psychologists, linguists, and political scientists. Published in Science this week, it represents the team’s most ambitious study yet about music.

Manvir Singh, a graduate student in Harvard’s department of Human Evolutionary Biology, studied indigenous music and performance as a part of his fieldwork. Here Mentawai children in Siberut Island, Indonesia, are practicing in a kitchen. Video courtesy of Manvir Singh.

Music appears in every society observed.

“As a graduate student, I was working on studies of infant music perception, and I started to see all these studies that made claims about music being universal,” Mehr said. “How is it that every paper on music starts out with this big claim, but there’s never a citation backing that up … Now we can back that up.”

They looked at every society for which there was ethnographic information in a large online database, 315 in all, and found mention of music in all of them. For the discography, they collected 118 songs from a total of 86 cultures, covering 30 geographic regions. And they added the ethnographic material they’d collected.

“I started to see all these studies that made claims about music being universal. How is it that every paper on music starts out with this big claim but there’s never a citation backing that up … Now we can back that up.” Samuel Mehr, researcher

The team and their researchers coded the ethnography and discography that makes up the Natural History of Song into dozens of variables. They logged details about singers and audience members, the time of day and duration of singing, the presence of instruments, and more for thousands of passages about songs in the ethnographic corpus. The discography was analyzed four different ways: machine summaries, listener ratings, expert annotations, expert transcriptions.

They found that, across societies, music is associated with behaviors such as infant care, healing, dance, and love (among many others, like mourning, warfare, processions, and ritual). Examining lullabies, healing songs, dance songs, and love songs in particular, they discovered that songs that share behavioral functions tend to have similar musical features.

“Lullabies and dance songs are ubiquitous, and they are also highly stereotyped,” Singh said. “For me, dance songs and lullabies tend to define the space of what music can be. They do very different things with features that are almost the opposite of each other.”

The unanswered questions of music, according to researcher Manvir Singh

Transcript:.

So in this project we asked, “What is universal about music, and what varies?” This is a deep question in the study of humanity. Music is this widespread behavior but until now, we actually have not known, there have been a lot of unanswered questions about what these patterns are. There’s something that I find appealing about this array of humans doing all of these different things, producing music — which is this beautiful cultural product, but there being these echoes of similarity, or this echo of structure? That’s what I find appealing about the question and the project. But there’s also the more academic side, which is: Music is this ubiquitous human behavior. And it’s something that people engage in daily in societies around the world. And yet we understand so little about it. Obviously, music is hugely diverse, even within a classroom of students — the kind of music they listen to, engage with, and produce is, like, hugely different. But I think there’s something comforting and colorful about the fact that in this huge web of diversity there is something that we share, that we’re all speaking to.”

Definitely seeing music as cross-cultural excites Singh because he comes to the Natural History of Song project as someone who studies the social, cognitive, and cultural evolutionary foundations of complex traditions found throughout societies from music to law, narrative to witchcraft.

For Mehr, who began his academic life in music education, the study looks toward unlocking the governing rules of “musical grammar.” That idea has been percolating among music theorists, linguists, and psychologists of music for decades, but has never been demonstrated across cultures.

“In music theory, tonality is often assumed to be an invention of Western music, but our data raise the controversial possibility that this could be a universal feature of music,” he said. “That raises pressing questions about structure that underlies music everywhere — and whether and how our minds are designed to make music.”

This study was supported in part by the Harvard Data Science Initiative, an NIH Director’s Early Independence Award, the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program, and the Microsoft Research postdoctoral fellowship program.

Share this article

More like this.

Songs in the key of humanity

The look of music

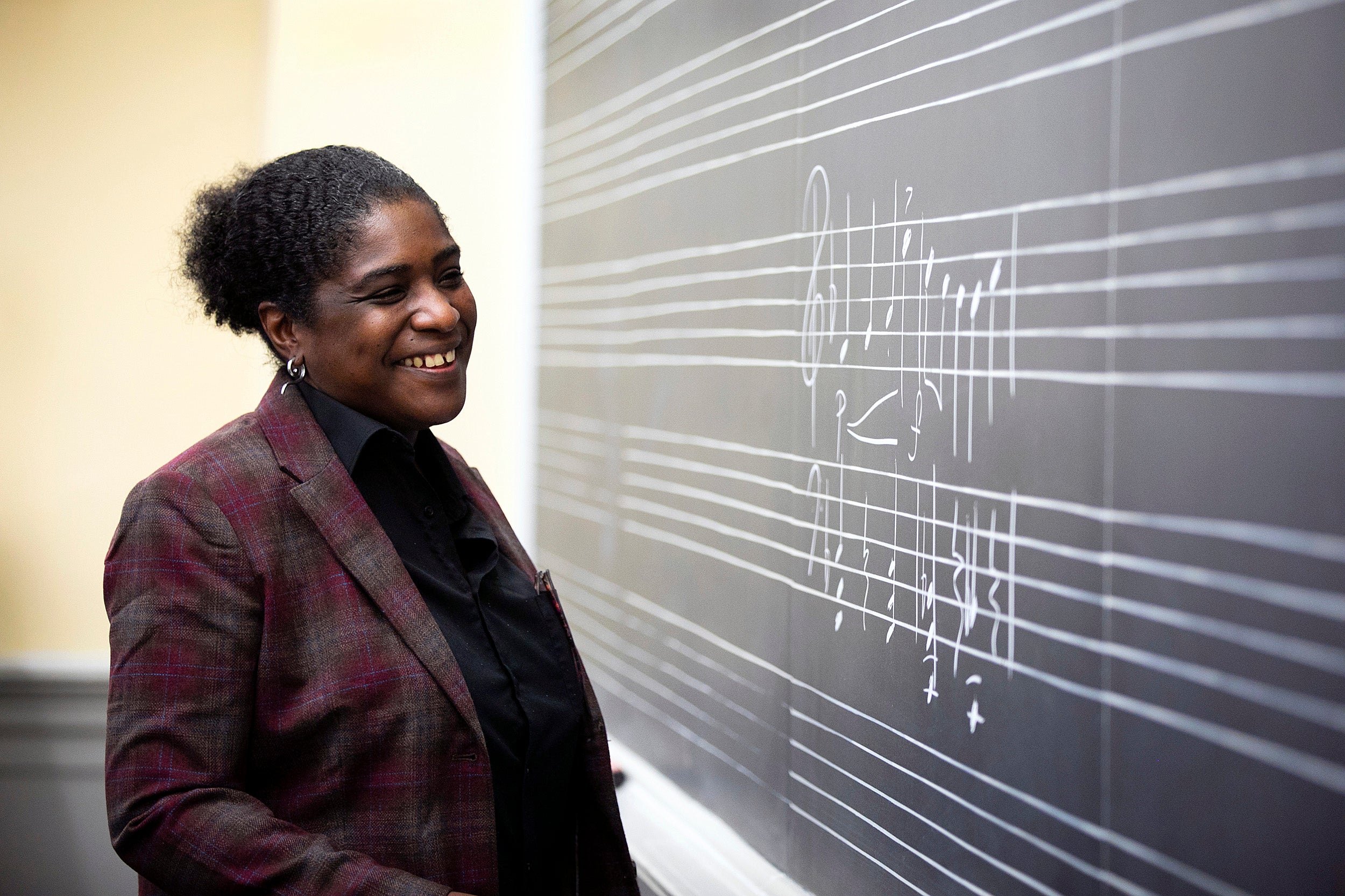

New faculty: Yvette J. Jackson

You might like.

At first, Heidi Schreck wasn’t sure the world needed another take on ‘Uncle Vanya’

OFA dance classes offer well-being through movement

There’s never a shortage of creativity on campus. But during Arts First, it all comes out to play.

Epic science inside a cubic millimeter of brain

Researchers publish largest-ever dataset of neural connections

How far has COVID set back students?

An economist, a policy expert, and a teacher explain why learning losses are worse than many parents realize

Excited about new diet drug? This procedure seems better choice.

Study finds minimally invasive treatment more cost-effective over time, brings greater weight loss

Is Music a Universal Language?

Expressing the shared human experience..

Posted July 31, 2015 | Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

Music is a universal language. Or so musicians like to claim. “With music,” they’ll say, “you can communicate across cultural and linguistic boundaries in ways that you can’t with ordinary languages like English or French.”

On one level, this statement is obviously true. You don’t have to speak French to enjoy a composition by Debussy. But is music really a universal language? That depends on what you mean by “universal” and what you mean by “language.”

Every human culture has music, just as each has language. So it’s true that music is a universal feature of the human experience. At the same time, both music and linguistic systems vary widely from culture to culture. In fact, unfamiliar musical systems may not even sound like music. I’ve overheard Western-trained music scholars dismiss Javanese gamelan as “clanging pots” and traditional Chinese opera as “cackling hens.”

Nevertheless, studies show that people are pretty good at detecting the emotions conveyed in unfamiliar music idioms—that is, at least the two basic emotions of happiness and sadness. Specific features of melody contribute to the expression of emotion in music. Higher pitch, more fluctuations in pitch and rhythm, and faster tempo convey happiness, while the opposite conveys sadness.

Perhaps then we have an innate musical sense. But language also has melody—which linguists call prosody. Exactly these same features—pitch, rhythm, and tempo—are used to convey emotion in speech, in a way that appears to be universal across languages.

Listen in on a conversation in French or Japanese or some other language you don’t speak. You won’t understand the content, but you will understand the shifting emotional states of the speakers. She’s upset, and he’s getting defensive. Now she’s really angry, and he’s backing off. He pleads with her, but she doesn’t buy it. He starts sweet-talking her, and she resists at first but slowly gives in. Now they’re apologizing and making up...

We understand this exchange in a foreign language because we know what it sounds like in our own language. Likewise, when we listen to a piece of music, either from our culture or from another, we infer emotion on the basis of melodic cues that mimic universal prosodic cues. In this sense, music truly is a universal system for communicating emotion.

But is music a kind of language? Again, we have to define our terms. In everyday life, we often use “language” to mean “communication system.” Biologists talk about the “language of bees,” which is a way to tell hive mates about the location of a new source of nectar.

Florists talk about the “language of flowers,” through which their customers can express their relationship intentions. “Red roses mean…. Pink carnations mean… Yellow daffodils mean…” (I’m not a florist, so I don’t speak flower.)

And then there’s “ body language .” By this we mean the postures, gestures, movements and facial expressions we use to convey emotions, social status, and so on. Although we often use body language when we speak, linguists don’t consider it a true form of language. Instead, it’s a communication system, just as are the so-called languages of bees and flowers.

By definition, language is a communication system consisting of (1) a set of meaningful symbols (words) and (2) a set of rules for combining those symbols (syntax) into larger meaningful units (sentences). While many species have communication systems, none of these count as a language because they lack one or the other component.

The alarm and food calls of many species consist of a set of meaningful symbols, but they lack rules for combining those symbols. Likewise, bird song and whale song have rules for combining elements, but these elements aren’t meaningful symbols. Only the song as a whole has meaning—“Hey ladies, I’m hot,” and “Hey other guys, stay away!”

Like language, music has syntax—rules for ordering elements—such as notes, chords, and intervals—into complex structures. Yet none of these elements has meaning on its own. Rather, it’s the larger structure—the melody—that conveys emotional meaning. And it does that by mimicking the prosody of speech.

Since music and language share features in common, it’s not surprising that many of the brain areas that process language also process music. But this doesn’t mean that music is language. Part of the misunderstanding comes from the way we tend to think about specific areas of the brain as having specific functions. Any complex behavior, whether language or music or driving a car, will recruit contributions from many different brain areas.

Music certainly isn’t a universal language in the sense that you could use it to express any thought to any person on the planet. But music does have the power to evoke deep primal feelings at the core of the shared human experience. It not only crosses cultures, it also reaches deep into our evolutionary past. And it that sense, music truly is a universal language.

David Ludden is the author of The Psychology of Language: An Integrated Approach .

Patel, A. D. (2008). Music, language, and the brain. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Slevc, L. R., Okada, B. M. (2015). Processing structure in language and music: a case for shared reliance on cognitive control. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 22, 637-652.

Tan, S.-L., Pfordresher, P., & Harré, R. (2010). Psychology of music: from sound to significance . New York, NY: Psychology Press.

David Ludden, Ph.D. , is a professor of psychology at Georgia Gwinnett College.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Understanding what emotional intelligence looks like and the steps needed to improve it could light a path to a more emotionally adept world.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

The Power of Music to Help Change the World (and Me!)

by Paul Wertico, CCPA Associate Professor of Jazz

Wow — it’s sometimes hard to fathom that the year 1968 was half a century ago and at a time when, comparatively speaking, life seemed relatively simple to life as we know it today.

As an avid listener, I’d routinely hear songs on the radio that I liked (either by an artist I knew, or one who was new), and I’d eventually sing along with those songs pretty much whenever I heard them. The lyrics were sometimes audible and distinguishable, and other times only some of them were, in which case I made up the rest of the “lyrics” with whatever words or syllables I felt like singing. Although a song’s sound, groove, harmony and melody were also important to me, singing along with the song was often so much fun that sometimes the “fun part” actually masked the song’s intended meaning; or in certain cases, my life’s experiences and worldly knowledge hadn’t evolved yet to the point where I was able to truly decipher the actual meaning and message of the songs.

When I reflect now on what my life was like as a 15-year-old back in 1968, it makes me realize how much of those songs I actually “heard” and how much I actually “missed.”

Growing up as a white teenager living in the predominantly white suburb of Cary, Illinois, my life was quite different from the various situations and living conditions described in the lyrics of certain songs I listened to. Even though the radio programmers were no doubt primarily interested in whatever songs would appeal to their station’s listeners (and therefore bring in money and advertisers to those stations), knowingly or unknowingly, they also performed a service to the community and to young people like myself by spreading the word and enlightening listeners through certain songs’ insightful and even profound lyrics that portrayed the outside world as a much bigger — and in many cases “badder” — place than my bedroom, my parent’s car, or wherever a radio was playing.

“When I reflect now on what my life was like as a 15-year-old back in 1968, it makes me realize how much of those songs I actually ‘heard’ and how much I actually ‘missed.’”

– Paul Wertico CCPA Associate Professor of Jazz

More in this section

Roosevelt receives $5 million grant to expand stem doctoral programs and research facilities

Awarded by the U.S. Department of Education and given to only nine institutions nationwide, the grant is part of a national effort to assist historically underserved student populations pursue a career in STEM fields and improve graduation rates.

- Learn to fundraise for Save The Music

- Start a Fundraiser on Facebook

- Start a Fundraiser on Classy

- Pledge your birthday

Home › Blog › Advocacy › How Does Music Affect Society?

November 3, 2021

How Does Music Affect Society?

By Lia Peralta

Music has shaped cultures and societies around the world for generations. It has the power to alter one’s mood, change perceptions, and inspire change. While everyone has a personal relationship with music, its effects on the culture around us may not be immediately apparent. So, how does music affect society ? The impact of music on society is broad and deeply ingrained in our history. To demonstrate how deeply our lives are affected by music, let’s delve into the sociological effects of music and how it affects culture.

How Does Music Affect Society

Music is an essential aspect of all human civilizations and has the power to emotionally, morally, and culturally affect society. When people from one culture exchange music with each other, they gain valuable insight into another way of life. Learning how music and social bonding are linked is especially crucial in times of conflict when other lines of communication prove to be challenging.

Music, as a cultural right, may aid in the promotion and protection of other human rights. It can help in the healing process, dismantling walls and boundaries, reconciliation, and education. Around the world, music is being used as a vehicle for social change and bringing communities together.

At the core of our everyday experience with music, we use it to relax, express ourselves, come to terms with our emotions, and generally improve our well-being. It has evolved into a tool for healing and self-expression, often dictating how we, as individuals, take steps to impact society.

Why is Music Beneficial to Society?

Music has the power to connect with and influence people in a way that feels fundamentally different from other forms of communication. Humans often feel that “no one understands them” or knows how they “truly feel.” Many resort to music to find connections with others to express themselves or find a sense of understanding among peers.

How does music affect our lives? Music has the ability to deeply affect our mental states and raise our mood. When we need it, music gives us energy and motivation. When we’re worried, it can soothe us; when we’re weary, it can encourage us; and when we’re feeling deflated, it can re-inspire us. It even functions to improve our physical health, as it’s been proven that high-tempo music results in better workouts . We connect with others via music, especially those who produce or perform it — we recite their lyrics, dance to their melodies, and form a sense of connection through their self-expression.

Songs and melodies have the power to inspire people, guide their actions, and aid in the formation of identities. Music can unite people – even if absorbed in solitude, capture your imagination and boost creativity. A person who has been affected by music is not alone. They are among the masses trying to find their role in society and form connections with others. Thankfully, while it can help us “find ourselves,” music influence on society can also be seen in:

– Providing a platform for the underrepresented to speak out

– Affecting mood and inspiration

– Helping us cope by encouraging us to express ourselves through movement and dancing

– Bridging a divide in communication

– Creating a venue for education and idea-sharing

Music’s Effect on Our Thoughts and Actions

Music’s effect on the self is far-reaching, tapping into our memories, subconscious thoughts, emotions, and interests. Thanks to the music artists who have put their heart and soul into creating, we feel connected with other people and their difficulties, challenges, and emotions. So much about our brains is still being discovered but through neurology, we are learning more and more about how music affects us.

We all know that being exposed to music’s beauty, rhythm, and harmony significantly influences how we feel. We also know that music emotionally impacts us, reaching into forgotten memories and connecting us to ourselves. Music therapy is often used to improve attention and memory, and can have a positive effect on those suffering from dementia or Alzheimers. Music has the potential to be a powerful healing tool in a variety of ways and pervades every aspect of our existence. Songs are used to define spiritual ceremonies, toddlers learn the alphabet via rhyme and verse, and malls and restaurants, where we choose to spend our free time, are rarely silent.

But how much can this ever-present object influence our behavior and emotions? According to research , music has a significant impact on humans. It can potentially affect disease, depression, expenditure, productivity, and our outlook on life. The impact of music on our brain is being better understood thanks to advances in neuroscience and the examination of music’s impact on the brain. It has been shown via brain scans that when we listen to or perform music, nearly all brain regions are active simultaneously. Listening to and making music may actually changes the way your brain works .

According to studies, music impacts how we view the world around us. In a 2011 research paper , 43 students were given the job of recognizing happy and sad faces while listening to happy or sad music in the background by researchers from the University of Groningen. Participants noticed more cheerful faces when upbeat music was played, while the opposite was true when sad music was played. According to the researchers, music’s effect might be because our perceptual decisions on sensory stimuli, such as facial expressions in this experiment, are directly impacted by our mental state. Music triggers physical responses in the brain and puts in motion a series of chemical reactions.

In the book, Classical Music: Expected the Unexpected , author and conductor Kent Nagano spoke with neuroscientist Daniel J. Levitin on how music interacts with the brain. The sociological effects of music can include the improvement of people’s well-being due to chemical reactions in the brain, such as an increase in oxytocin. Oxytocin, or the “love hormone,” makes us more inclined to engage in social interactions or build trust between individuals. Music also boosts the synthesis of the immunoglobulin A antibody, which is crucial for human health. Studies have also shown that melatonin, adrenaline, and noradrenaline levels increase after only a few weeks of music therapy. The hormones noradrenaline and adrenaline cause us to become more alert, experience excitement, and cause the brain’s “reward” regions to fire.

The Cultural Impact of Music

Today’s popular music reflects the culture of the day. But, how does music affect society over time? How has music changed over the past century? In the lyrics and sound of each era, we can discern the imprints of a particular generation and see history in the making. And, in this day and age, culture is changing faster than ever before, mirroring musical forms that are evolving and emerging at the same rate.

For decades, the effects of music on society have been a source of contention, and it seems that with each generation, a new musical trend emerges that has the previous generations saying, “Well back in my day, we had…”. Music and social movements are intrinsically linked together. Almost every popular kind of music was considered scandalous back in the day, and the dancing that accompanied jazz, rock ‘n’ roll, and hip-hop drew protests and boycotts from all around. Just look at The Beatles, who were considered scandalous by the older generation when they first arrived on the music scene.

While we may not like a new music trend or a particular genre of music, we must also take a step back and appreciate how lucky we are to be exposed to it at all. Music in some parts of the world is not as easily accessible. While music has always been a means of pushing the boundaries of expression, it’s clear that the world isn’t expressing itself in the same way. The various musical trends we’ve seen in just this lifetime provide an insightful look into what is and isn’t being discussed in some cultures.

Music as an Agent for Change

Another essential factor to consider is how strongly music influences society and, thus, human behavior. Music’s impact on human rights movements and its role as an agent for change is clear in the history books. One example is the impact of the “freedom songs” of the Civil Rights movement, such as “We Shall Overcome” and “Strange Fruit.” These songs broke down barriers, educated people, built empathy across the divide, and had a hand in ending segregation. Music today continues to shed light on the inequalities experienced by people worldwide, and it’s clear that music will never stop acting as an agent for change.

Because of how strong of an influence melodies and lyrics have on society, we must be acutely aware of our current culture. Still, more importantly, we must be conscious of the cultures we wish to build and develop via our music. Songs have the power to change the world in unexpected ways, challenging preconceived notions and shedding light on issues that have historically been ignored.

Music’s Impact on Youth

How does having music education impact youth? We know from our experience that music in schools improves student, teacher and community outcomes – and in turn, society, specifically the future generation. In a case study about our work in Newark, NJ , 68% of teachers reported improved academic performance. 94% of teachers also saw improvement in social-emotional skills. Schools saw better attendance and ELA (English Language Arts) scores.

Another example of this is our work in Metro Nashville Public Schools , which has been a partner district of Save The Music since 1999. Students who participated in music programs for up to one year had significantly better attendance and graduation rates, higher GPAs and test scores, and lower discipline reports than their non-music peers. Students with more than one year of music participation performed significantly better than their peers with less on each of these indicators.

We Invest in Music in Schools

Whether you’re a music buff or not, anyone can appreciate the impact music has on society. A great way to show this appreciation is by being part of music’s impact on the world and learning how you can help facilitate change. Save The Music is a music foundation that collaborates with public school districts to provide grants for music education instructors and school administrators in the form of new instruments, technology , and online music education . Our initiative helps schools get their music programs off the ground and keep students inspired.

Contact us today to learn how you can save the music through our music education advocacy programs .

Advocacy , Blog

Subscribe to our newsletter

Interested in working with us contact, how music can transcend language and impact the world, march 7, 2022, written by:, marina azcárate.

Time and time again we have heard that music is a universal language. But what exactly does that mean?

This means that music has the unique power to unite people across all boards globally. Regardless of race, class, gender identity and/or expression, religion, age, you name it, music can bring us together. If we take a minute to think that two human beings will communicate mostly via one of countless languages and dialects and that when two people don’t speak the same language communication becomes near impossible for some individuals, the power of music becomes even more astonishing. Melodies take the place of words.

While it is true that oftentimes, the most popular music in each country is that in its own language, there have been many artists who have broken the barriers of language with their music. Nowadays, this debate has become increasingly relevant as we begin to see non-English songs dominate the international charts, notably Latin music and K-Pop.

A song can serve the purpose of replacing a whole conversation, through which two or more people can tune into, entering the same wavelength by the end of it and having reached a mutual understanding of one another. Who knows, maybe the world would be a better place if language disappeared and we had to communicate via music.

In this sense, musicians kind of serve as unofficial ambassadors of intercultural communication. Cross-culture shamans.

But why is this important? Why does it matter if music can transcend language or not?

Well, it matters because if used correctly music can be one of the most transformative tools at hand that we have. It can affect social change, and prod society to evolve, helping us walk hand in hand towards a better tomorrow.

Music has been breaking language barriers for quite some time now

An early historical example of music breaking the boundaries of music would be opera. Opera famously began in Italy in the 1500s, and it eventually spread out all across the globe. An art based on storytelling, that somehow managed to wonderfully depict the most epic of tales in a foreign language. And let us tell ya, there weren’t any subtitles back then.

Now of course as opera evolved in each nation, many national composers began writing operas in their own language, but still, the favoured language was often Italian or Latin. With German and French following suit. In fact, opera is possibly one of the only music genres that haven’t been so thoroughly invaded by the English language.

While we might dismiss opera as not being all that impactful for music today, we need to remember that before opera, in Europe, grandiose music was mostly listened to in churches, cathedrals, or places of the sort. As such, music during the renaissance was sternly tied to religion and religious stories. With opera, music began its journey towards secularism once again.

French music saved lives during WW2, literally.

Possibly one of the greatest examples of music breaking down language barriers, and being subsequently used for the greater good is the case of French iconic singer, Edith Piaf, during World War 2. The singer was invited to sing in Germany, and much to the dismay of her nation she accepted. Under two conditions: Firstly she stated that if she was to sing, she would do so for everyone, meaning both German troops and French prisoner Jews. Secondly, she wanted to take photos with everyone after each performance.

Her music was so revered, that the Germans accepted. Following her concerts, Edith Piaf would pass the photos on to her influential friends who would then create false documents for the Jews in the photos. Finally, the French singer would return to Germany for another tour and once again after the concerts during the signings and photos, she would secretly slip the documents to the prisoners, helping free thousands of Jews during the war.

Now, of course, Edith Piaf was an exceptional case. But lives were literally saved because her music was so powerful, that even the Germans wanted to bask in the sheer marvellousness of her voice. Regardless of whether she was singing in French. And these are the Nazis we’re talking about, who, you know, kind of was a “their-language-above-all-else-kinda-people”.

Still, while incredibly heroic and impactful examples exist of the boundary-breaking, positive impact of music, it’s not all a bed of roses.

But music isn’t always enough, and it doesn’t always work

Truth is, although of course music can transcend language, and be an incredible tool for social and political change, it doesn’t always work.

Bob Marley transcended language, time, and cultures. But he couldn’t do it all.

Sometimes music simply isn’t enough, even when speaking the same language. Bob Marley is an incredibly iconic cultural figure, there is no denying that. He lives on in the collective memory and will most probably continue to do so for centuries. Most people know his face, his voice, his music. His impact has been such that essentially all reggae music is associated with him. Chances are you’ll see the colours red, yellow, and green, and one of Bob Marley’s songs will subconsciously begin playing in your mind. Generation after generation, Bob Marley’s songs are incorporated into contemporary culture as hymns and odes to togetherness, to unity, to universal love and solidarity.

Bob Marley’s music has undoubtedly transcended the barriers not only of language but of time too. But there was one thing he couldn’t do, help his country when it was most in need.

It was 1978, and Jamaica was on the verge of civil war between both major political parties, the Peoples National Party (PNP), and the Jamaican Labour Party (JLP). Both parties hired, essentially, gangsters for protection. Yet the tension was such, that even the local gang members thought the violence had to come to an end. And so they (the actual gang members) came up with the idea of having a concert for peace. In fact, it was one of the gang members, Claudius “Claudie” Massop who travelled to London to convince a then exiled Bob Marley to participate.

During his performance at the concert, Marley famously brought up the two opposing political leaders Michael Manley and Edward Seaga took their hands and held them up together. That moment will forever be revered in history, and for a bit there, one could even believe that the violence was over. Unfortunately, two years after the concert the event organizers were killed, and the next election year saw double the reported murders.

Music breaking language barriers today

One can’t dispute the fact that over the past few decades. English music has dominated the international charts, with the occasional foreign-language song miraculously “making it through”. It’s quite a common thing for a country to listen to their own national artist, and then the typical English speaking ones. The whole world knows Beyoncé, Lady Gaga, The Beatles, Kanye West, Michael Jackson or Eminem.

This is due in part, to the global hegemony held by the US during the last fifty years or more. But guess what? Now the US seems to be losing its position culturally, politically, economically, and socially as the world leader, and other cultures are breaking through and seeping into the global consciousness.

Today, international charts are seeing a huge shift in the languages present in the most listened to lists. One look at Youtube’s most listened to songs of 2021 will confirm this. Why Youtube you ask? Well, its streaming services reach is about 1.9 billion people per month, surpassing by far any other service. Spanish and Indian language songs are in fact the most listened to, followed closely by Korean and English.

K-Pop completely obliterates language barriers in music

It’s true that Indian songs are possibly listened to mostly by the Eastern side of the globe, but there is no doubt that Latin music and K-pop has completely obliterated the English music hegemony. These two styles have taken over the globe, and are the pure example of music transcending language barriers.

The K-Pop idols are known for being a source of inspiration and empowerment to the youth. Their distinct aesthetics and vibrant music have truly had an impact when it comes to youth culture and expressing one’s individuality.

Latin music belongs everywhere, and so do Latin people

Similarly, the rise in Latin music has highlighted the cultural relevance and importance of Latin populations in several countries. Latino communities around the globe have seen their culture appreciated, respected, and for the first time regarded as being on the same level as any other English-speaking artist. This development has marked a historical moment where Latin music isn’t just for Latin people, it’s for everyone. In the same way that Latin people don’t just belong in Latin countries, they belong everywhere.

This issue is particularly eye-opening in countries such as the US, where the Latin community has been discriminated against and oppressed for decades, and continues to live and fight systemic racism.

Thanks to music, things that before were previously frowned upon when you had foreign heritage, such as speaking a different language, are now praised and appreciated. Diversity is increasingly being celebrated and treated as something that enriches society rather than threatens it. And it is partly due to the contributions of music. Let’s not forget it, and let’s continue to push forward together.

Trust us when we say, the soundtrack of your life will be so much better if you listen beyond the words.

- Lifestyle Music

Masters of the Creative Craft, Creative Directors Edition

New Realities Of Love: Is Ethical Non-Monogamy For Real?

Giving Credit Where Credit’s Due, Producers Edition

Subscribe to stay informed of everything in our world.

Don't miss any news

Privacy Overview

Meller – Halloween Campaign

Gisela – 249 The Secret

IGWT – Create Your Balance

Born Living Yoga – Fall Campaign

The Relationship Between Music, Culture, and Society: Meaning in Music

- First Online: 14 August 2018

Cite this chapter

- Georgina Barton 2

2211 Accesses

7 Citations

Music is inextricably linked with the context in which it is produced, consumed and taught and the inter-relationship between music, society and culture has been researched for many decades. Seminal research in the field of ethnomusicology has explored how social and cultural customs influence music practices in macro and micro ways. Music, for example, can be a core feature of social celebrations such as weddings to a means of cultural expression and maintenance through ceremony. It is this meaning that can alter across contexts and therefore reflected in the ways music and sound is manipulated or constructed to form larger works with different purposes. Whether to entertain or play a crucial role in ceremonial rituals music practices cannot be separated from the environment in which it exists.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Almén, B. (2017). A theory of musical narrative . Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Book Google Scholar

Andersen, W. M., & Lawrence, J. E. (1991). Integrating music into the classroom (2nd ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing Company.

Google Scholar

Baldwin, J. R., Faulkner, S. L., Hecht, M. L., & Lindsley, S. L. (2008). Redefining culture: Perspectives across the disciplines . London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers.

Barton, G. M. (2004). The influence of culture on instrumental music teaching: A participant-observation case study of Karnatic and Queensland instrumental music teachers in context . Unpublished PhD thesis, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, Australia.

Barton, G. M. (2006). The real state of music education: What students and teachers think. In E. MacKinlay (Ed.), Music Education, Research and Innovation journal (MERI) . Sydney, Australia: Australian Society for Music Education.

Blacking, J. (1973). How musical is man? Seattle and London: University of Washington Press.

Born, G., & Hesmondhalgh, D. (2000). Western music and its others: Difference, representation and appropriation in music . Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Boyce-Tillman, J. (1996). A framework for intercultural dialogue. In M. Floyd (Ed.), World musics in education (pp. 43–49). Hants, UK: Scholar Press.

Brennan, P. S. (1992). Design and implementation of curricula experiences in world music: A perspective. In H. Lees (Ed.), Music education: Sharing musics of the world (pp. 221–225). Seoul, Korea: Conference Proceedings from World Conference International Society of Music Education.

Campbell, P. S. (1991). Lessons from the world: A cross-cultural guide to music teaching and learning . New York: Schirmer Books.

Campbell, P. S. (Ed.). (1996). Music in cultural context: Eight views on world music education . Reston, VA: Music Educators National Conference.

Campbell, P. S. (2004). Teaching music globally: Experiencing music, expressing culture . New York: Oxford University Press.

Campbell, P. S. (2016). World music pedagogy: Where music meets culture in classroom practice. In C. R. Abril & B. M. Gault (Eds.), Teaching general music: Approaches, issues and viewpoints (pp. 89–11). New York: Oxford University Press.

Chapter Google Scholar

Dewey, J. (1958). Art as experience . New York: Capricorn Books.

Dillon, S. C. (2001). The student as maker: An examination of the meaning of music to students in a school and the ways in which we give access to meaningful music education . Unpublished PhD thesis, La Trobe University, Victoria, Australia.

Dunbar-Hall, P. (2009). Ethnopedagogy: Culturally contextualised learning and teaching as an agent of change. Action, Criticism, and Theory for Music Education, 8 (2), 60–78.

Dunbar-Hall, P., & Gibson, C. (2004). Deadly sounds, deadly places: Contemporary aboriginal music in Australia . Sydney: UNSW Press.

Dunbar-Hall, P., & Wemyss, K. (2000). The effects of the study of popular music on music education. International Journal of Music Education, 36 , 23–34.

Article Google Scholar

Elliott, D. J. (1994). Music, education and musical value. In H. Lees (Ed.), Musical connections: Tradition and change—Proceedings of the 21st World Conference of the International Society for Music Education (Vol. 21). Tampa, FL.

Elliott, D. J., & Silverman, M. (1995). Music matters: A new philosophy of music education . Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

Ellis, C. J. (1985). Aboriginal music education for living: Cross-cultural experiences from South Australia . St Lucia, QLD: University of Queensland Press.

Feld, S. (1984). Sound structure as social structure. Journal of Ethnomusicology, 28 (3), 383–409.

Feld, S. (2013). Sound and sentiment: Birds, weeping, poetics and song in Kaluli expression . Durham and London: Duke University Press.

Gaunt, H., & Westerlund, H. (2013). Collaborative learning in higher music education . London: Routledge.

George, L. (1987). Teaching the music of six different cultures . Danbury, CT: World Music Press.

Glickman, T. (1996). Intercultural music education: The early years. Journal of the Indian Musicological Society, 27 , 52–58.

Gourlay, K. (1978). Towards a reassessment of the ethnomusicologist’s role in research. Journal of Ethnomusicology, 22 , 1–35.

Green, L. (1990). Music on deaf ears: Musical meaning, ideology, education . Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press.

Green, L. (2002). How popular musicians learn: A way ahead for music education . Aldershot, UK: Ashgate Publishing.

Green, L. (2011). Learning, teaching and musical identity: Voices across cultures . Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press.

Hargreaves, D. J., Marshall, N. A., & North, A. C. (2003). Music education in the twenty-first century: A psychological perspective. British Journal of Music Education, 20 (2), 147–163.

Harwood, D. L. (1976). Universals in music: A perspective from cognitive psychology. Journal of Ethnomusicology, 20 , 521–533.

Herndon, M., & McLeod, N. (Eds.). (1982). Music as culture . Norwood, PA: Norwood Editions.

Ho, W.-C. (2014). Music education curriculum and social change: A study of popular music in secondary schools in Beijing, China. Music Education Research, 16 (3), 267–289.

Inskip, C., MacFarlane, A., & Rafferty, P. (2008). Meaning, communication, music: Towards a revised communication model. Journal of Documentation, 64 (5), 687–706. https://doi.org/10.1108/00220410810899718

Ishimatsu, N. (2014). Shifting phases of the art scene in Malaysia and Thailand: Comparing colonized and non-colonized countries. Engage! Public Intellectuals Transforming Society, 1 , 78–87.

Kelly, S. N. (2016). Teaching music in American society: A social and cultural understanding of music education (2nd ed.). New York and London: Routledge.

Lamasisi, F. (1992). Documentation of music and dance: What it means to the bearers of the traditions, their role and anxieties associated with the process. Oceania Monograph Australia, 41 , 222–234.

Langer, S. K. (1953). Feeling and form: A theory of art developed from philosophy in a new key . New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons.

Langer, S. K. (1957). Philosophy in a new key: A study of the symbolism of reason, rite and art . Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Leong, S. (2016). Glocalisation and interculturality in Chinese research: A planetary perspective. In P. Burnard, E. Mackinlay, & K. Powell (Eds.), Routledge handbook of intercultural arts research (pp. 344–357). London: Routledge.

Lomax, A. (1968). Folk song style and culture . Washington, DC: American Association for the Advancement of Science.

Lomax, A. (1976). Cantometrics: An approach to the anthropology of music . Berkeley: University of California Extension Media Centre.

Lundquist, B., & Szego, C. K. (Eds.). (1998). Musics of the world’s cultures: A source book for music educators . Nedlands, WA: CIRCME.

MacDonald, A., Barton, G. M., Baguley, M., & Hartwig, K. (2016). Teachers’ curriculum stories: Thematic perceptions and capacities. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 48 (13), 1336–1351. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2016.1210496

McAllester, D. P. (1984). A problem in ethics. In J. C. Kassler & J. Stubington (Eds.), Problems and solutions: Occasional essays in musicology presented to Alice M. Moyle (pp. 279–289). Sydney, Australia: Hale and Iremonger.

McAllester, D. P. (1996). David P. McAllester on Navajo music. In P. S. Campbell (Ed.), Music in cultural context: Eight views on world music education (pp. 5–11). Reston, VA: Music Educators National Conference.

Merriam, A. P. (1964). The anthropology of music . Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press.

Meyer, L. B. (1961). Emotion and meaning in music . Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Miller, T. E. (1996). Terry E. Miller on Thai music. In P. S. Campbell (Ed.), Music in cultural context: Eight views on world music education (pp. 5–11). Reston, VA: Music Educators National Conference.

Nattiez, J. (1990). Music and discourse: Toward a semiology of music . Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Nettl, B. (1975). Music in primitive cultures: Iran, a recently developed nation. In C. Hamm, B. Nettl, & R. Byrnside (Eds.), Contemporary music and music cultures (pp. 71–100). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Nettl, B. (1992). Ethnomusicology and the teaching of world music. International Journal of Music Education, 20 , 3–7.

Oku, S. (1994). From the conceptual approach to the cross-arts approach. In S. Leong (Ed.), Music in schools and teacher education: A global perspective (pp. 115–132). Nedlands, WA: International Society for Music Education, Commission for Music in Schools and Teacher in Association with CIRCME.

Payne, H. (1988). Singing a sister’s sites: Women’s land rites in the Australian Musgrave ranges . Unpublished PhD thesis, University of Queensland, St Lucia, QLD.

Pratt, G., Henson, M., & Cargill, S. (1998). Aural awareness: Principles and practice . Oxford: Oxford University Press on Demand.

Radocy, R., & Boyle, J. D. (1979). Psychological foundations of musical behaviour . Springfield, IL: C. C. Thomas.

Rampton, B. (2014). Crossing language and ethnicity among adolescents (2nd ed.). London: Routledge.

Ravignani, A., Delgado, T., & Kirby, S. (2016). Musical evolution in the lab exhibits rhythmic universals. Nature Human Behaviour, 1 (1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-016-0007

Reimer, B. (1989). A philosophy of music education (2nd ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Shepard, J., & Wicke, P. (1997). Music and cultural theory . Cambridge: Polity Press.

Small, C. (1996). Music, society, education . Hanover: University Press of New England.

Small, C. (1998). Musicking: The meanings of performing and listening . Hanover: University Press of New England.

Smith, R. G. (1998). Evaluating the initiation, application and appropriateness of a series of customised teaching and learning strategies designed to communicate musical and related understandings interculturally . Unpublished Doctor of Teaching thesis, Northern Territory University, Northern Territory.

Spearritt, G. D. (1980). The music of the Iatmul people of the middle Sepik river (Papua New Guinea): With special reference to instrumental music at Kandangai and Aibom . Unpublished PhD thesis, University of Queensland, St Lucia, QLD.

Steier, F. (1991). Research and reflexivity . London: Sage Publications.

Stock, J. P. (1994). Concepts of world music and their integration within western secondary music education. International Journal of Music Education, 23 , 3–16.

Stone, R. M. (2016). Theory for ethnomusicology . London: Routledge.

Suzuki, S. (1982). Where love is deep: The writings of Shinichi Suzuki (K. Selden, Trans.). St. Louis, MO: Talent Education Journal.

Swanwick, K. (1996). A basis for music education (2nd ed.). Berks, UK: NFER Publishing Company.

Swanwick, K. (1999). Teaching music musically . London and New York: Routledge Publishers.

Swanwick, K. (2001). Musical development theories revisited. Music Education Research, 3 (2), 227–242. https://doi.org/10.1080/14613800120089278

Swanwick, K. (2016). A developing discourse in music education: The selected works of Keith Swanwick . London: Routledge Publishers.

Turek, R. (1996). The elements of music: Concepts and application . New York: McGraw-Hill.

Walker, R. (1990). Musical beliefs: Psychoacoustic, mythical and educational perspectives . New York and London: Teachers College Press Columbia University.

Walker, R. (1992). Open peer commentary: Musical knowledge: The saga of music in the national curriculum. Psychology of Music, 20 (2), 162–179.

Walker, R. (1998). Swanwick puts music education back in its western prison—A reply. International Journal of Music Education, 31 (1), 59–65.

Walker, R. (2001). The rise and fall of philosophies of music education: Looking backwards in order to see ahead. Research Studies in Music Education, 17 (1), 3–18.

Whitman, B. A. (2005). Learning the meaning of music . Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Teacher Education and Early Childhood, University of Southern Queensland, Springfield Central, Brisbane, QLD, Australia

Georgina Barton

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2018 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Barton, G. (2018). The Relationship Between Music, Culture, and Society: Meaning in Music. In: Music Learning and Teaching in Culturally and Socially Diverse Contexts. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-95408-0_2

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-95408-0_2

Published : 14 August 2018

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-319-95407-3

Online ISBN : 978-3-319-95408-0

eBook Packages : Education Education (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

HYPOTHESIS AND THEORY article

The human nature of music.

- 1 Westmead Psychotherapy Program, Sydney Medical School, The University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia

- 2 The MARCS Institute for Brain, Behaviour, and Development, Western Sydney University, Sydney, NSW, Australia

- 3 Department of Psychology, School of Philosophy, Psychology and Language Sciences, The University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, United Kingdom

Music is at the centre of what it means to be human – it is the sounds of human bodies and minds moving in creative, story-making ways. We argue that music comes from the way in which knowing bodies (Merleau-Ponty) prospectively explore the environment using habitual ‘patterns of action,’ which we have identified as our innate ‘communicative musicality.’ To support our argument, we present short case studies of infant interactions using micro analyses of video and audio recordings to show the timings and shapes of intersubjective vocalizations and body movements of adult and child while they improvise shared narratives of meaning. Following a survey of the history of discoveries of infant abilities, we propose that the gestural narrative structures of voice and body seen as infants communicate with loving caregivers are the building blocks of what become particular cultural instances of the art of music, and of dance, theatre and other temporal arts. Children enter into a musical culture where their innate communicative musicality can be encouraged and strengthened through sensitive, respectful, playful, culturally informed teaching in companionship. The central importance of our abilities for music as part of what sustains our well-being is supported by evidence that communicative musicality strengthens emotions of social resilience to aid recovery from mental stress and illness. Drawing on the experience of the first author as a counsellor, we argue that the strength of one person’s communicative musicality can support the vitality of another’s through the application of skilful techniques that encourage an intimate, supportive, therapeutic, spirited companionship. Turning to brain science, we focus on hemispheric differences and the affective neuroscience of Jaak Panksepp. We emphasize that the psychobiological purpose of our innate musicality grows from the integrated rhythms of energy in the brain for prospective, sensation-seeking affective guidance of vitality of movement. We conclude with a Coda that recalls the philosophy of the Scottish Enlightenment, which built on the work of Heraclitus and Spinoza. This view places the shared experience of sensations of living – our communicative musicality – as inspiration for rules of logic formulated in symbols of language.

“There are certain aspects of the so-called ‘inner life’—physical or mental —which have formal properties similar to those of music—patterns of motion and rest, of tension and release, of agreement and disagreement, preparation, fulfilment, excitation, sudden change, etc. Langer (1942 , p. 228).

“The function of music is to enhance in some way the quality of individual experience and human relationships; its structures are reflections of patterns of human relations, and the value of a piece of music as music is inseparable from its value as an expression of human experience” Blacking (1995 , p.31).

“The act of musicking establishes in the place where it is happening a set of relationships, and it is in those relationships that the meaning of the act lies. They are to be found not only between those organized sounds which are conventionally thought of as being the stuff of musical meaning but also between the people who are taking part, in whatever capacity, in the performance” Small (1998 , p.9).

We present a view that places our ability to create and appreciate music at the center of what it means to be human. We argue that music is the sounds of human bodies, voices and minds – our personalities – moving in creative, story-making ways. These stories, which we want to share and listen to, are born from awareness of a complex body evolved for moving with an imaginative, future seeking mind in collaboration with other human bodies and minds. Musical stories do not need words for the creation of rich and inspiring narratives of meaning.

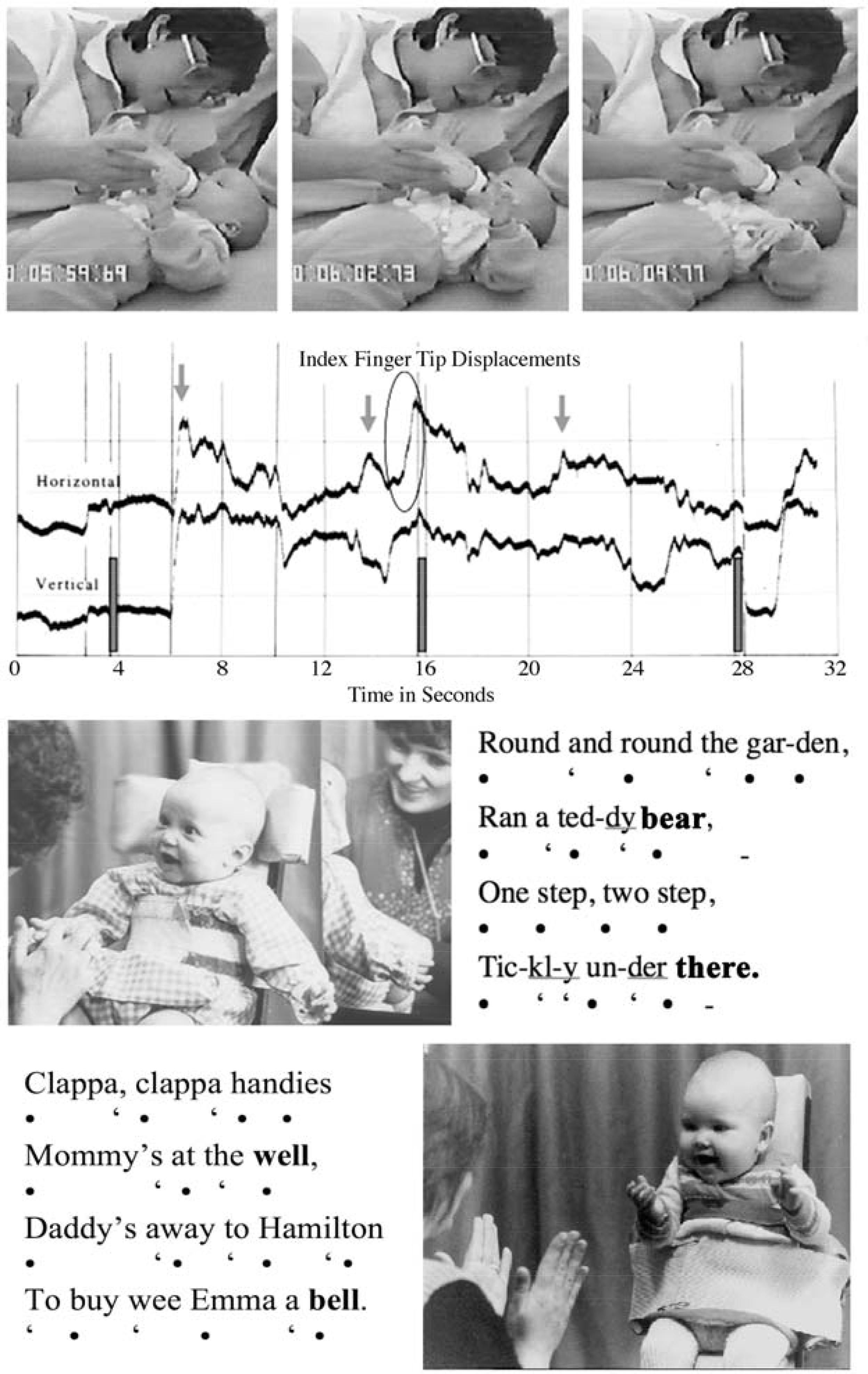

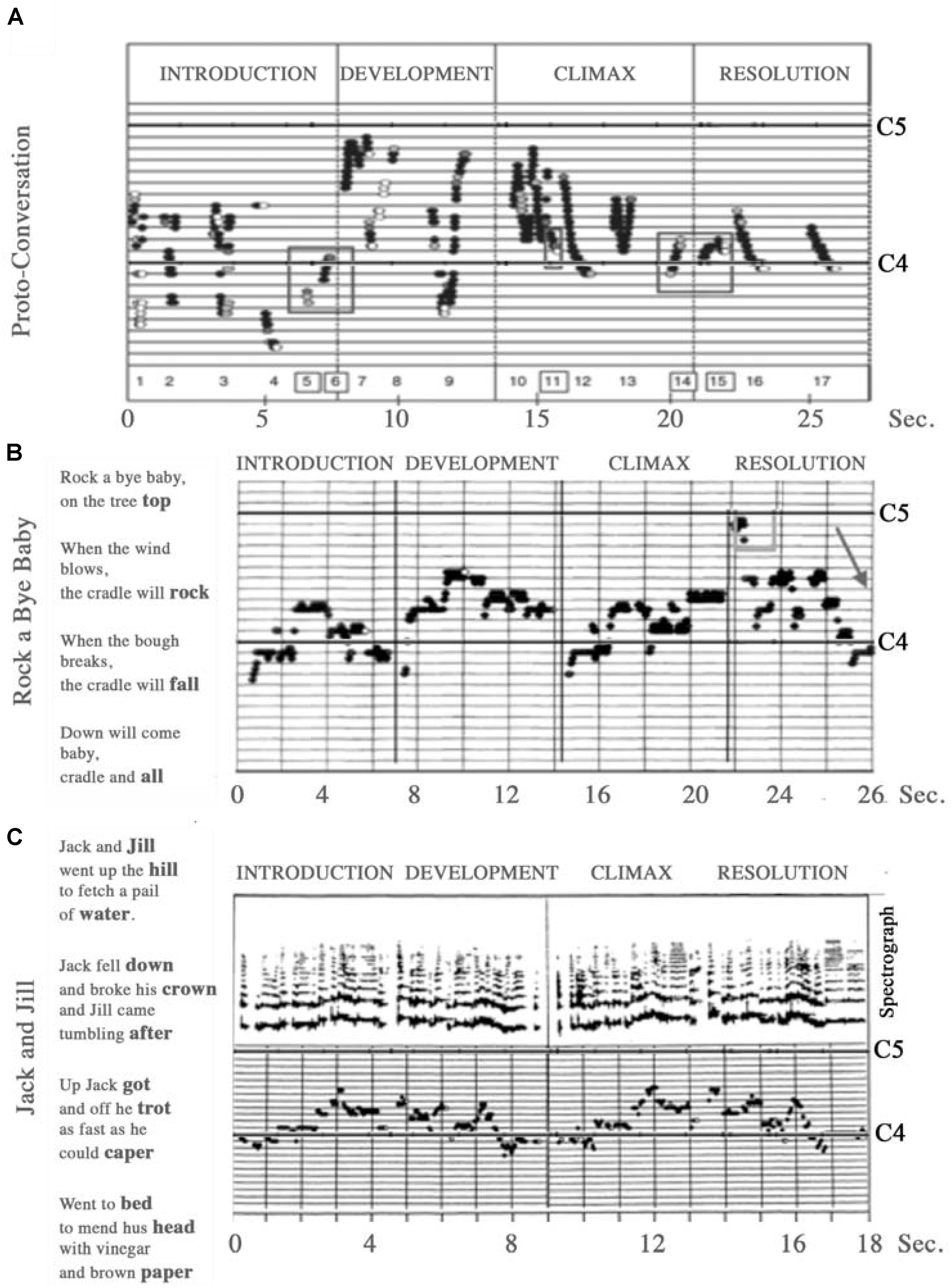

We adopt the word ‘musicking’ (as used above by Christopher Small) to draw attention to the embodied energy that creates music, and which moves us, emotionally and bodily. Further, we argue that music comes from the way in which knowing bodies ( Merleau-Ponty , 2012 [1945] , p. 431) prospectively explore the environment using habitual ‘patterns of action,’ which we have identified as our innate ‘communicative musicality,’ observed while infants are in intimate communication with loving caregivers ( Malloch and Trevarthen, 2009a ). In short case studies of infant interactions with micro analyses of video and audio recordings, we show communicative musicality in the timings and shapes of intersubjective vocalizations and body movements of adult and child that improvise with delight shared narratives of meaning.

Following a survey of the history of discoveries of infant abilities, we propose that the gestural narrative structures of voice and body seen as infants communicate with loving caregivers, ‘protonarrative envelopes’ of expression for ideas of activity ( Panksepp and Bernatzky, 2002 ; Panksepp and Trevarthen, 2009 ), are the building blocks of what become particular cultural instances of the art of music, and of dance, theater and other temporal arts ( Blacking, 1995 ).

As the child grows and becomes a toddler, she or he eagerly takes part in a children’s musical culture of the playground ( Bjørkvold, 1992 ). Soon more formal education with a teacher leads the way to the learning of traditional musical techniques. It is at this point that the child’s innate body vitality of communicative musicality can be encouraged and strengthened through sensitive, respectful, playful, culturally informed teaching ( Ingold, 2018 ). On the other hand, it may wither under the weight of enforced discipline for the sake of conforming to pre-existing cultural rules without attention to the initiative and pleasure of the learner’s own music-making.

The central importance of our abilities for music as part of what sustains our well-being is supported by evidence that communicative musicality strengthens emotions of social resilience to recover from mental stress and illness ( Pavlicevic, 1997 , 1999 , 2000 ). Drawing on the experience of the first author as a counselor, we argue that the strength of one person’s communicative musicality can support the vitality of another’s through the application of skilful techniques that encourage an intimate, supportive, therapeutic, spirited companionship.

Turning to brain science, focussing on hemispheric differences in performance and in response to music, and the affective neuroscience of Jaak Panksepp (1998) , we emphasize that the psychobiological purpose of our ‘muse within’ ( Bjørkvold, 1992 ) grows from the integrated rhythms of neural energy for prospective, sensation-seeking affective guidance of vitality of movement in the brain ( Goodrich, 2010 ; Stern, 2010 ).

We conclude with a Coda – an enquiry into the philosophy of the Scottish Enlightenment, which built on the work of philosophers Heraclitus and Spinoza. This view of living in community gives innate sympathy or ‘feeling with’ other humans a fundamental role within a duplex mind seeking harmony in relationships by attunement of motives ( Hutcheson, 1729 , 1755 ). It places the shared experience of sensations of living – our communicative musicality – ahead of logic formulated in symbols of language.

Music Moves US – Embodied Narratives of Movement

Small (1998) calls attention to music as intention in activity by using the verb musicking – participating as performer or listener with attention to the sounds created and the appreciation and participation by others. The compelling quality of music comes from the relationships of sounds, bodies and psyches. ‘Musicking’ points to our musical life in active ‘I-Thou’ relationships. Only in this intimacy of consciousness and its interests can we share ‘I-It’ identification and use of objects, giving things we use, including musical compositions, meaning ( Buber, 1923/1970 ).

‘I-Thou’ relationships are entered into through the body. The philosopher Merleau-Ponty (2012 [1945]) writes that “The subject only achieves his ipseity [individual personality, selfhood] by actually being a body, and by entering into the world through his body… The ontological world and body that we uncover at the core of the subject are not the world and the body as ideas ; rather, they are the world itself condensed into a comprehensive whole and the body itself as a knowing-body ” (p. 431; italics added). Musicking is knowing bodies coming alive in the sounds they make. Scores and other tools that record the product of musicking, performed or imagined, aid the retention of ideas, as semantics of language does, and they serve discussion and analysis – but they are not the same as the breathing, moving, embodied experience of human musicking ( Mithen, 2005 ).

Musicking is the expression of the sensations of what we call our communicative musicality , for the purpose of creating music that is enlivening and ‘beautiful’ ( Malloch, 1999 ; Malloch and Trevarthen, 2009a ; Trevarthen, 2015 ; Trevarthen and Malloch, 2017b ). We define communicative musicality as our innate skill for moving, remembering and planning projects in sympathy with others through time, creating an endless variety of dramatic temporal narratives in song or instrumental music. We describe this life-sharing in movement as having three components:

Pulse – a regular succession through time of discrete movements (which may, for example, be used to create sound for music, or to create movement with music – dance) using our felt sense of acting which enables the ‘future-creating’ predictive process by which a person may anticipate or create what happens next and when.

Quality – consisting of the contours of expressive vocal and body gesture, shaping our felt sense of time in movement. These contours can consist of psychoacoustic attributes of vocalizations – timbre, pitch, volume – or attributes of direction and intensity of the moving body perceived in any modality.

Narratives of individual experience and of companionship, built from sequences of co-created gestures which have particular attributes of pulse and quality that bring aesthetic pleasure ( Malloch and Trevarthen, 2009b ; Trevarthen and Malloch, 2017b ).

With music we create memorable poetic events in signs that express in sound our experience of living together in the creating vitality of ‘the present moment’ ( Stern, 2004 , 2010 ). The anthropologist and ethnologist Claude Lévi-Strauss draws attention of linguists to the structured ‘raw’ emotive power of music (beyond what words may be ‘cooked’ to say).

“In the first volume of the Mythologiques, Le Cru et le Cuit. Lévi-Strauss refers to music as a unique system of signs possessing ‘its own peculiar vehicle which does not admit of any general, extramusical use’. Yet he also allows that music has levels of structure analogous to the phonemes and sentences of language. The absence of words as the connecting level is an obvious and pertinent fact in the structuring of meaning within music as a sign system.” ( Champagne, 1990 , p. 76).

Goodrich (2010) , in her appreciation of the contribution of neuroscientists Llinás (2001) and Buzsáki (2006) to the science of the mind for skilled movement, cites Llinás’ evidence on the role of intuitive structural ‘rules,’ seen also in a musical performance.

“Llinás describes another method of keeping movement as efficient as possible: motor ‘Fixed Action Patterns’ (FAPs), distinct and complicated ‘habits’ of movement built from reflexes, habits that we develop to streamline both neural action and muscle movement. These are not entirely fixed, despite their name; they are constantly undergoing modification, adaptation, refinement, and they overlap each other… Llinás even argues that the extraordinarily precise motor control of Jascha Heifetz playing Tchaikovsky’s violin concerto is composed of highly elaborated and refined FAPs, a description most instrumentalists would find absolutely plausible” ( Goodrich, 2010 , p. 339).

As Llinás himself writes,

“Can playing a violin concerto be a FAP? Well, not all of it, but a large portion. Indeed, the unique and at once recognisable style of play Mr. Heifetz brings to the instrument is a FAP, enriched and modulated by the specifics of the concert, generated by the voluntary motor system” (Llinás, p. 136).

We add that skilled FAPs are not “composed of reflexes” as separate automatic responses. Rather they are purposeful projects that are animated to be developed imaginatively, and affectively, with exploration of their biomechanical “degrees of freedom,” as in Nikolai Bernstein’s detailed description of how a toddler learns to become a virtuoso in bipedal locomotion, which he calls The Genesis of the Biodynamical Structure of the Locomotor Act ( Bernstein, 1967 , p. 78). The testing of these locomotor acts is with an immediate and essential estimation by gut feelings ( Porges, 2011 ) of any risks or benefits, any fears or joy, they may entail within the body.

Music Reflects the Felt-Sense of our Future-Exploring Motor Intelligence

Consciousness is created as the ongoing sense of self-in-movement with which we experience and manipulate the world around us. Its origin is in our evolutionary animal past, evolved for new collaborative, creative projects, regulated between us by affective expressions of feelings of vitality from within our bodies ( Sherrington, 1955 ; Panksepp, 1998 ; Damasio, 2003 ; Mithen, 2005 ; Stern, 2010 ; Eisenberg and Sulik, 2012 ).

Using the philosopher and psychologist James (1892/1985) as a starting point for exploring the intimacy of feeling that supports and guides psychotherapy, Russell Meares (2005 , p.18), following the ‘conversational model’ of therapy developed with his collaborator psychiatrist/psychotherapist Hobson (1985) , identifies five dimensions of the self:

1. awareness which is necessary for the experience;

2. there is a shape to this inner life;

3. there is a sense of its ongoingness ;

4. our inner life has a connectedness or unity ;

5. our experience of our inner life goes on inside a virtual container which is our background emotional state and the background experience of our body .

These sensuous qualities of the experienced self are expressed in music, and in other temporal arts, as ‘the human seriousness of play’ ( Turner, 1982 ). Music, as Susan Langer says so clearly in the quote at the start of this paper, has qualities of this inner life described by Meares as shape, ongoingness and flow, connectedness and unity. The notion of music as expressive of the movements of our inner life has also been explored by music theorists, most notably Ernst Kurth (1991) . Likewise, in his book Self comes to Mind , Antonio Damasio likens all our emotion and feeling to a ‘musical score’ that accompanies other ongoing mental process ( Damasio, 2010 , p.254).

The ultimate motivation for creating music can even be traced to the cellular level. In Man On His Nature ( Sherrington, 1955 ), in a chapter entitled The Wisdom of the Body , the creator of modern neurophysiology Charles Sherrington called the coming together of communities of cells into the integrated body, nervous system and brain of a person “an act of imagination” (p. 103). Neuroscientist Rudolfo Llinás also grants subjectivity, a sense of self, to all forms of life. “Irritability [i.e., responding to external stimuli with organized, goal-directed behavior] and subjectivity, in a very primitive sense, are properties originally belonging to single cells” ( Llinás, 2001 , p.113). “Thinking”, writes Llinás (2001 , p.62), “ultimately represents movement, not just of body parts or objects in the external world, but of perceptions and complex ideas as well.”

Intrinsic to the sociability of this intelligence of movement is sensitivity for the exploration of the future, which is woven into our creation and experience of music. Karl Lashley (1951) reflecting on the evolution of animal movement, proposed that the ability to predict what might come next, and to plan the ‘serial ordering’ of separate actions, may be understood as the foundation for our logical reasoning as an individual, as it is for the grammar or syntax and prosody of our communication in language. It is essential for musicking. A restless future-seeking intelligence, with our urge to share it, inspires us to express our personalities as ‘story-telling creatures,’ who want to share, and evaluate, others’ stories ( Bruner, 1996 , 2003 ).

All animal life depends on motivated movement – the urge to explore with curiosity – to move towards food with anticipation, to move away from a predator with fear, to interact playfully with a trusted friend ( Eibl-Eibesfeldt, 1989 ; Panksepp and Biven, 2012 ; Bateson and Martin, 2013 ). A great achievement of modern science of the mind was the discovery by a young Russian psychologist Nikolai Bernstein of how all consciously made body movements depend upon an ‘image of the future’ ( Bernstein, 1966 , 1967 ).

Bernstein applied the new technology of movie photography to make refined ‘cyclographic’ diagrams of displacements of body parts, from which he analyzed the forces involved to fractions of a second. His findings reported in Coordination and Regulation of Movements became widely known in English translation in 1967, at the same time as video records of infant behaviors were described more accurately (see next Section The Genesis of Music in Infancy – A Short History of Discoveries), revealing their anticipatory motor control adapted for intelligent understanding of how objects may be manipulated, as well as for communication and cooperation ( Trevarthen, 1984b , 1990b ).

Our musical creativity and pleasure come from the way our body hopes to move, with rhythms and feelings of grace and biological ‘knowing’ (see Merleau-Ponty). The predicting, embodied self of a human being experiences time, force, space, movement, and intention/directionality in being. Together, these form the Gestalt of ‘vitality’ ( Stern, 2010 ), the ‘forms of feeling’ ( Hobson, 1985 ) by which we sense in ourselves and in others that movement, be that movement of the body or of a piece of music, is ‘well-done’ ( Trevarthen and Malloch, 2017b ).

The Genesis of Music in Infancy – A Short History of Discoveries

The ability to create meaning with others through wordless structured gestural narratives, that is, our communicative musicality, emerges from before birth and in infancy. From this innate musicality come the various cultural forms of music.

Any attempt to understand how human life has evolved its unique cultural habits needs to start with observing what infants know and can do. Organisms regulate the development of their lives by growing structures and processes from within their vitality, by autopoiesis that requires anticipation of adaptive functions. And they must develop and protect their abilities in response to environmental affordances and dangers, with consensuality ( Maturana and Varela, 1980 ; Maturana et al., 1995 ). Infants are ready for human cultural invention and collaboration as newly hatched birds are ready for flying – within ‘the biology of love’ ( Maturana and Varela, 1980 ; Maturana and Verden-Zoller, 2008 ). All organisms reach out in time and space to make use of the ‘affordances’ for thought and action ( Gibson, 1979 ).

Infants have no language to learn what other humans know, or what ancestors knew. But the vitality of their spontaneous communicative musicality, highly coordinated and adapted to be shared through narratives with sympathetic and playful companions, enables meaningful communication in the ‘present moment’ ( Stern, 2004 ; Figure 1 , Upper Right), which may build serviceable memories extended in space and time ( Donaldson, 1992 ).

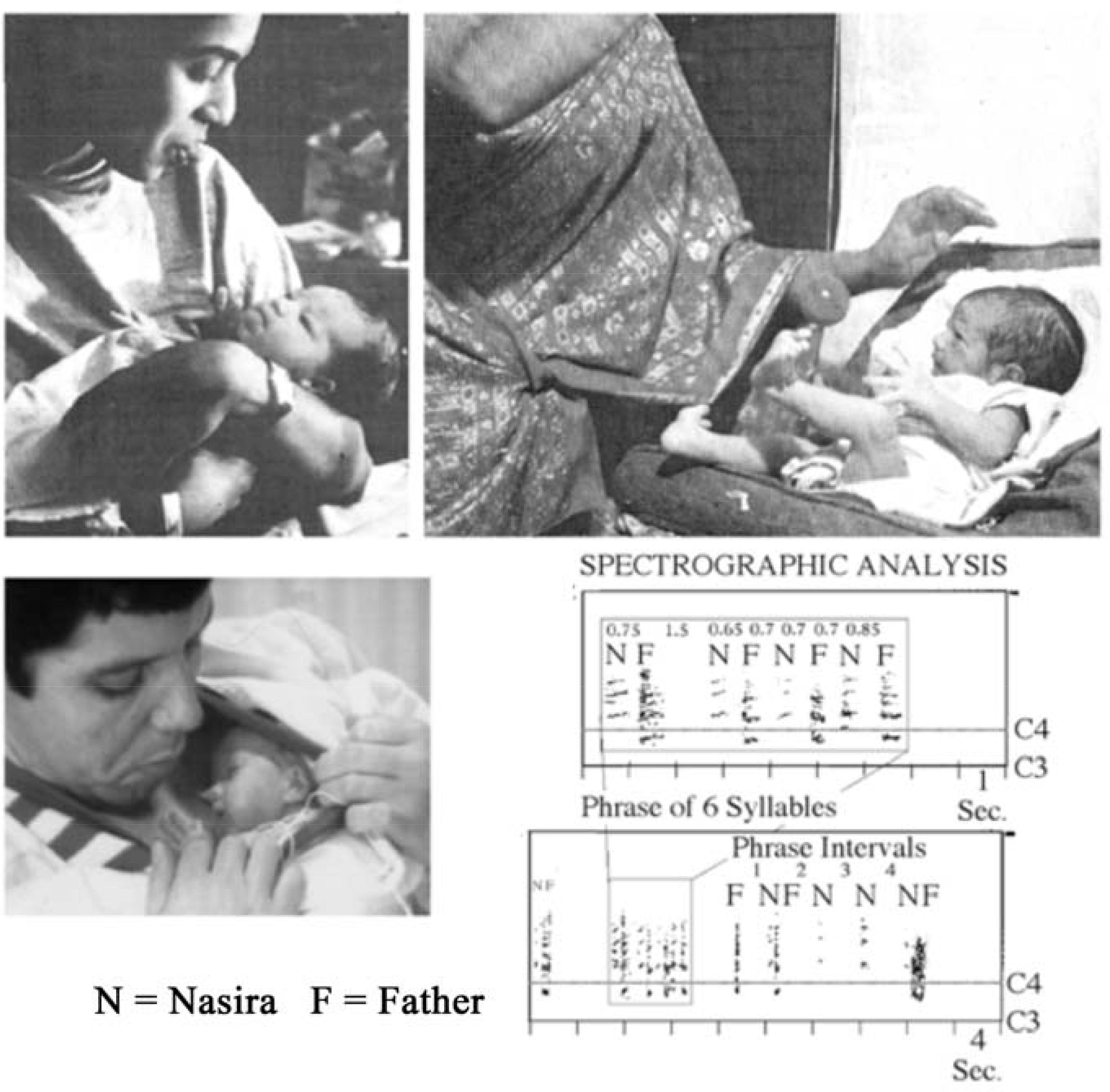

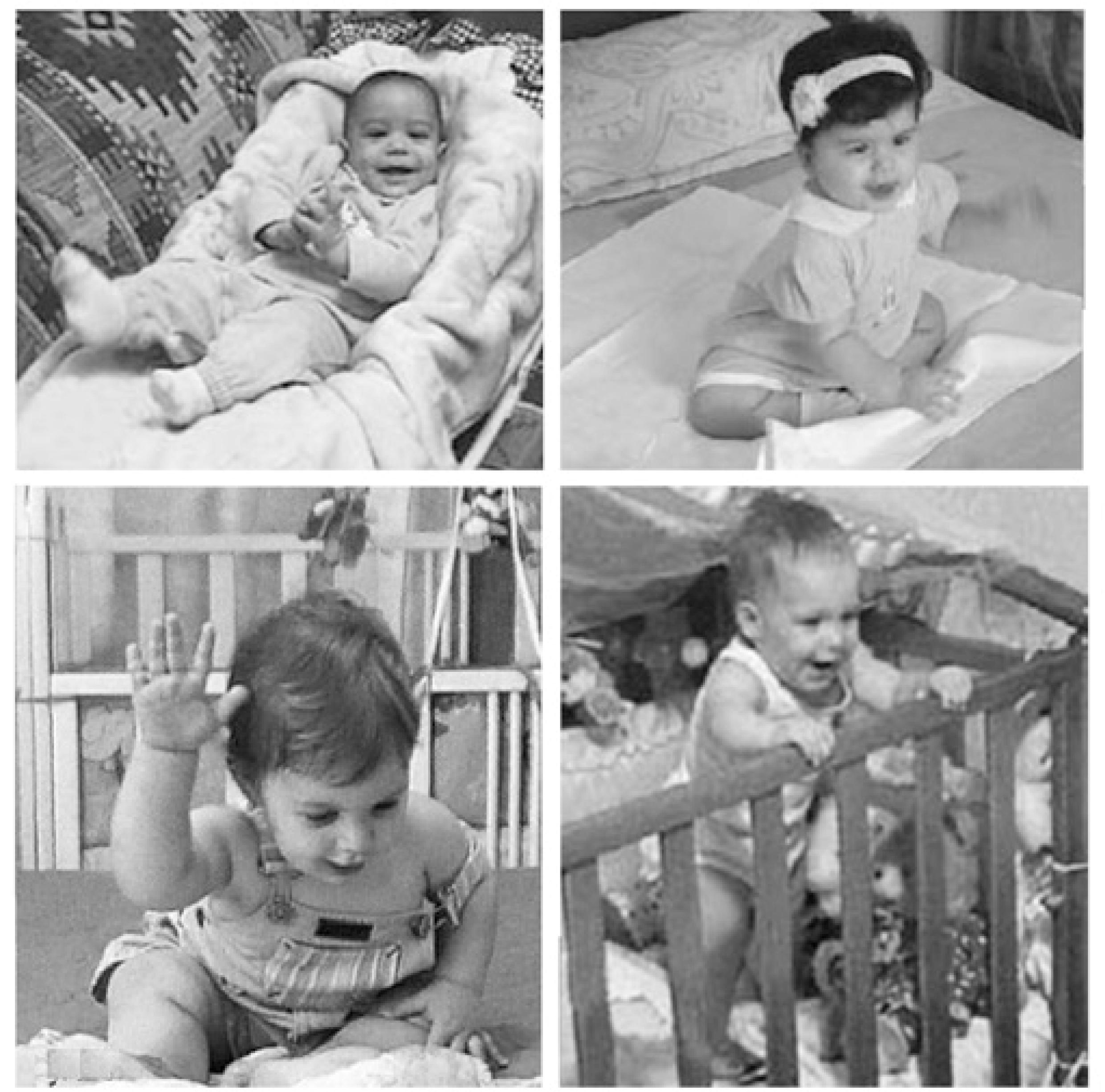

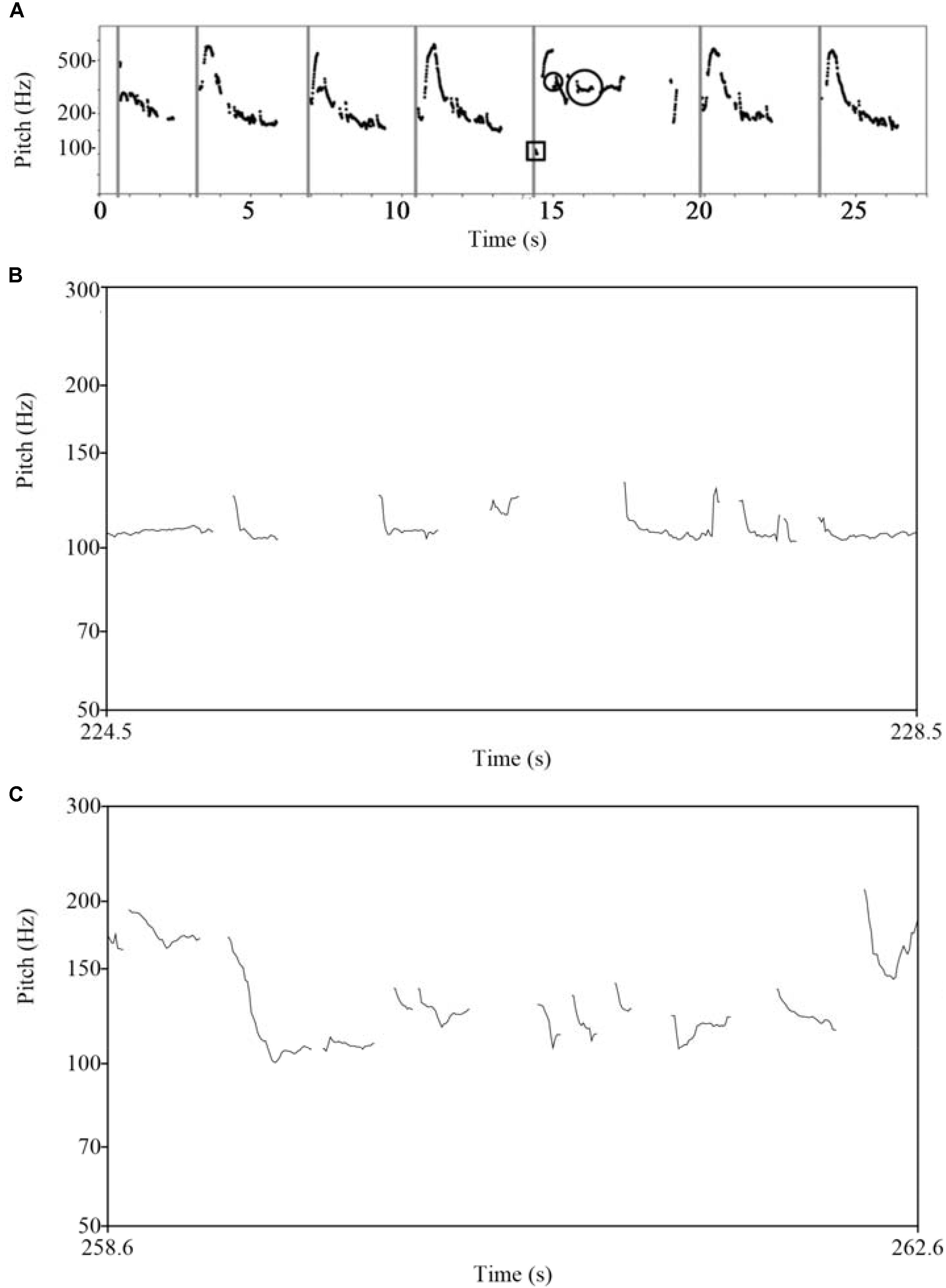

FIGURE 1. Inborn musicality shared in movement. Upper Left: Infant less than one hour after birth watches her mother’s tongue protrusion and imitates. Upper Right: On the day of birth, a baby in a hospital in India shares a game with a woman who moves a red ball. The baby tracks it with coordinated movements of her eyes and head, both hands and one foot. Lower: A two-month premature girl, Nasira, with her father, who holds her against his body in ‘kangaroo’ care. They exchange short ‘coo’ sounds with precisely shared rhythm. Upper Left and Upper Right: Photos for own use of second author from colleagues Vasudevi Reddy and Kevan Bundell. Part reproduced from Trevarthen (2015) , Figure 1, p. 131. Lower: Photo from Trevarthen (2008) , Figure 2, p. 22. Original spectrograph in Malloch (1999) , Figure 3, p. 37.

In this section we review changes in understanding of infant abilities over the past century which can help explain the peculiar way music has in the past been seen by some leading psychologists and linguists as a relatively insignificant epiphenomenon, learned for play, not, as we argue in this paper, a source of all talents for communication, rooted in our innate human communicative musicality of knowing bodies ( Merleau-Ponty , 2012 [1945] ) moving with prospective intuition to engage the world in company, ‘intersubjectively,’ from the start ( Zeedyk, 2006 ).

Two leading scholars in medical science and the science of child development in the past century, Freud (1923) and Piaget (1958 , 1966 ), declared that infants must be born without conscious selves conceiving an external world, and unable to adapt their movements to the expressive behavior of other people. The playful and emotionally charged behaviors of mothers and other affectionate carers were considered inessential to the young infant, who needed only responses to reflex demands for food, comfort and sleep.

Then René Spitz (1945) and Bowlby (1958) revealed the devastating effects on a child’s emotional well-being of separation from maternal care in routine hospital care with nursing directed only to respond to those reflex demands. Spitz observed that babies develop smiling between 2 and 5 months to regulate social contacts ( Spitz and Wolf, 1946 ), and he went on to study the independent will of the baby to regulate engagements of care or communication, by nodding the head for ‘yes’ or shaking for ‘no’ ( Spitz, 1957 ).

In the 1960s a major shift in understanding of the creative mental abilities of infants was inspired by a project of the educational psychologist Bruner (1966 , 1968 ), and the pediatrician Brazelton (1961 , 1979 ), who perceived that infants are gifted with sensibilities for imaginative play and ready to start cultural learning from the first weeks after birth. Supported by insights of Charles Darwin and by new findings of anthropology and animal ethology they studied infant initiatives to perceive and use objects, and they were impressed by the intimate reciprocal imitation that develops between infants and affectionate parents and caregivers who offer playful collaboration with the child’s rhythms and qualities of movement. Film studies showed that young infants make complex shifts of posture and hand gestures that are regulated rhythmically, similar to the same movements of adults ( Bruner, 1968 ; Trevarthen, 1974 ).

While this new appreciation of infant abilities was developed at the Center for Cognitive Studies at Harvard, radically transforming the ‘cognitive revolution’ that was announced there by George Miller, Noam Chomsky and Jerome Bruner in 1960, nearby at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, a project initiated by Bullowa (1979) sought evidence on the behaviors that regulate dialog before language. Bullowa used information from anthropology to draw attention to the measured dynamics of communication.

“For an infant to enter into the sharing of meaning he has to be in communication, which may be another way of saying sharing rhythm …. The problem is how two or more organisms can share innate biological rhythms in such a way as to achieve communication which can permit transmission of information they do not already share.” ( Bullowa, 1979 , p. 15, italics added).