The Urban Design Case Study Archive is a project of Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design developed collaboratively between faculty, students, developers, and professional library staff. Specifically, it is an ongoing collaboration between the GSD’s Department of Urban Planning and Design and the Frances Loeb Library. This project received funding from the Veronica Rudge Green Prize for its development and was originally envisioned by professors Peter Rowe and Rahul Mehrotra.

As a collection of case studies, the project aims to support the study of the built environment in urban areas through a rich data model for urban design projects and their related descriptions, interpretations, drawings, and images. It makes use of excellent data entry tools that support the sophisticated search and visualization needed to support its pedagogical aims and scholarly research. Each case study includes digital photographs of the urban context, the projects themselves, and other graphic representation such as site plans, sections, and elevations, as well as texts, commentary, articles, analyses, bibliographies, people involved and interviews to facilitate and encourage discoverability and a flexible navigation within and across case studies depending on research interests.

The project launched in 2023 with urban design projects awarded the Veronica Rudge Green Prize in Urban Design and will continue to cover urban design projects of excellence across the globe. We thank the funders, faculty, staff, students, and the developers Performant Solutions, LLC for bringing this project to fruition.

Veronica Rudge Green Prize in Urban Design

Rahul Mehrotra, John T. Dunlop Professor in Housing and Urbanization

Peter Rowe, Raymond Garbe Professor of Architecture and Urban Design and Harvard University Distinguished Service Professor

Ann Whiteside, Librarian/Assistant Dean for Information Services

Bruce Boucek, GIS, Data, and Research Librarian

Alix Reiskind, Research and Teaching Support Team Lead Librarian

Ines Zalduendo, Special Collections Curator

Research Staff

Boya Guo, DDes ‘22

Liene Asahi Baptista, MAUD ‘23

Yona Chung, DDes ‘25

Priyanka Kar, MAUD ‘24

Sarahdjane Mortimer, MAUD ‘23

Enrique Mutis, MAUD ‘24

Developer/Development Team

Performant Software

Jamie Folsom

Chelsea Giordan

Derek Leadbetter

Ben Silverman

With special thanks to all the image contributors who have generously granted us copyright permission to include their images in the Urban Design Case Study Archive.

Housing and the City: case studies of integrated urban design

This case study report assembles a series of housing initiatives from different cities that are developed to promote inclusive, sustainable and integrated designs. The schemes range in scale and geographic location, but in each case represent a clear commitment to achieve positive social and environmental outcomes through innovative yet people and planet-focused design.

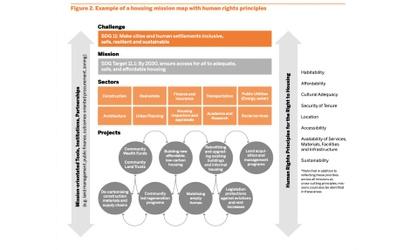

Housing is the backbone of a well-functioning and equitable city. The way in which housing is procured, financed, designed and allocated has significant implications for the lives of all urban residents. However, governments are failing to provide the human right of housing for all. The Council on Urban Initiatives has argued that mission-oriented approaches are needed to galvanise the whole of government engagement, while sectoral investment and cross-disciplinary collaboration are needed to realise the right to housing and prioritise the common good.

Housing has a profound spatial impact on cities. Apartment blocks, condominium towers, detached and terraced houses, self-built shacks and informal slums occupy by far the largest portion of urban land in cities around the world. Decisions about the physical distribution and design of housing will shape the social, economic and environmental dynamics for millions of urban residents for decades to come – particularly in Asia and Africa where urban populations are projected to balloon. Irresponsible development, poor community engagement, and overly permissive regulations and standards have encouraged architectural and urban design practices that foster inequality, exclusion and negative environmental impacts.

The report is divided into three sections: inclusive design, sustainable design and integrated design. Each section highlights examples of housing initiatives with short descriptive texts authored by individual Council members and their teams. From small-scale retrofits in Bogotá’s informal areas to Singapore’s massive state-driven investments, the case studies highlight that governing and designing housing for the common good is critical to the creation of just, green and healthy cities.

- Contributors

- Links

- Translations

- What is Gendered Innovations ?

Sex & Gender Analysis

- Research Priorities

- Rethinking Concepts

- Research Questions

- Analyzing Sex

- Analyzing Gender

- Sex and Gender Interact

- Intersectional Approaches

- Engineering Innovation

- Participatory Research

- Reference Models

- Language & Visualizations

- Tissues & Cells

- Lab Animal Research

- Sex in Biomedicine

- Gender in Health & Biomedicine

- Evolutionary Biology

- Machine Learning

- Social Robotics

- Hermaphroditic Species

- Impact Assessment

- Norm-Critical Innovation

- Intersectionality

- Race and Ethnicity

- Age and Sex in Drug Development

- Engineering

- Health & Medicine

- SABV in Biomedicine

- Tissues & Cells

- Urban Planning & Design

Case Studies

- Animal Research

- Animal Research 2

- Computer Science Curriculum

- Genetics of Sex Determination

- Chronic Pain

- Colorectal Cancer

- De-Gendering the Knee

- Dietary Assessment Method

- Heart Disease in Diverse Populations

- Medical Technology

- Nanomedicine

- Nanotechnology-Based Screening for HPV

- Nutrigenomics

- Osteoporosis Research in Men

- Prescription Drugs

- Systems Biology

- Assistive Technologies for the Elderly

- Domestic Robots

- Extended Virtual Reality

- Facial Recognition

- Gendering Social Robots

- Haptic Technology

- HIV Microbicides

- Inclusive Crash Test Dummies

- Human Thorax Model

- Machine Translation

- Making Machines Talk

- Video Games

- Virtual Assistants and Chatbots

- Agriculture

- Climate Change

- Environmental Chemicals

- Housing and Neighborhood Design

- Marine Science

- Menstrual Cups

- Population and Climate Change

- Quality Urban Spaces

- Smart Energy Solutions

- Smart Mobility

- Sustainable Fashion

- Waste Management

- Water Infrastructure

- Intersectional Design

- Major Granting Agencies

- Peer-Reviewed Journals

- Universities

Housing and Neighborhood Design: Analyzing Gender

- Full Case Study

The Challenge

Integrating gender analysis into architectural design and urban planning processes can ensure that buildings and cities serve well the needs of all inhabitants: women and men of different ages, with different family configurations, employment patterns, socioeconomic status and burdens of caring labor (Sánchez de Madariaga et al., 2013).

Method: Analyzing Gender

Analyzing gender in architectural and urban design can contribute to constructing housing and neighborhoods that better address people’s everyday needs, by fully integrating caring issues—caring for children, the elderly, and disabled—into research design.

Gendered Innovations:

1. Integrating gender expertise into housing and neighborhood design and evaluation is well underway, especially in Europe, and will improve living conditions for its residents, particularly parents, children, and the elderly.

2. Gender-aware housing and neighborhood design will improve pedestrian mobility and use of space for women and men of different ages, care duties, and physical abilities.

Planners, architects, and researchers from various fields have shown that gender roles and divisions of labor result in different needs with respect to built environments. These differences appear at various scales—individual buildings, neighborhoods, cities, and regions—and in the different domains of city building, such as housing, public facilities, transportation, streets and open space, employment and retail space (Sánchez de Madariaga, 2004). Gender analysis of space has identified the ways in which urban environments may enforce gender norms and fail to serve women and men equally (Spain, 2002; Hayden, 2005). Widely unrecognized gender assumptions in architecture and planning contribute to unequal access to urban spaces. While this Case Study addresses urban design in high-income countries, issues, such as safety in public space, or access to water, energy, transportation, and basic sanitation, become high priority in developing countries (Jarvis, 2009; Reeves et al., 2012).

Gendered Innovation 1: Integrating Gender Expertise into Housing and Neighborhood Design and Evaluation

In 2009 and 2010, Vienna was rated as one of the cities with the “highest quality of living in the world” (Irschik et al., 2013). Gender analysis contributed to this excellence: Over the past two decades, gender expertise has become fully integrated into Vienna’s urban planning (Booth et al., 2001):

1991 Two Viennese urban planners described the gendered aspects of urban design in an exhibition, “Who Owns Public Space–Women’s Daily Life in the City.”

1992 The Vienna City Council established the Women’s Office.

1998 The City Planning Bureau established the Co-ordination Office for Planning and Construction Geared to the Requirements of Daily Life and the Specific Needs of Women.

2002 Vienna designated Mariahilf, Vienna’s 6th district, a gender mainstreaming “pilot district,” a test area where gender analysis became an integral part of urban planning (Bauer, 2009; Kail et al., 2006 & 2007).

2010 Gender experts were moved from the Coordination Office directly into groups for “Urban Planning, Public Works and Building Construction.” This final step brought gender experts “in-house,” making them part of the core decision-making in the City of Vienna.

Method: Rethinking Priorities and Outcomes The European Union prioritized gender mainstreaming in 1996 and funded sixty networked projects in efforts to develop gender analysis for urban planning (Horelli et al., 2000; Roberts, 2013). Policy makers and funders that make gender analysis a requirement for funding potentially provide a platform for integrating gender-specific criteria into housing and neighbourhood planning. View General Method

Method: Analyzing Gender The relationship between place, space, and gender is complex and involves a number of steps: 1. Evaluating past urban design practices: Researchers recognized that urban design typically lacked a gender perspective, and was “blind” to differences between groups—women and men, people using different forms of transport and performing different kinds of work, etc. For example, design often focused on the needs of formally-employed persons who “inhabit the environment as consumers […] expecting residential areas to fulfill only one function and judging them by their recreational and leisure value.” This overlooks the needs of women and men who perform housework, child- and eldercare, etc. as well as the needs of “children, adolescents, and the elderly” (MOST-I, 2003; Ullmann, 2013). 2. Mainstreaming gender analysis into design (as discussed in Gendered Innovation 1 above). 3. Analyzing users and services: Designers may look at how various populations use space in relation to paid work, home life and work, social relations, cultural practices, and leisure. Designers may also examine the needs of various populations living in housing units and the needs of the people who service those units, such as cleaners and maintenance people. 4. Obtaining user input: Using co-creation and participatory research techniques , designers may ask users about their daily lived experience. Researchers may use a variety of methods, such as surveys, interviews, or observation. 5. Evaluation and planning (as discussed in Gendered Innovations 1 above). View General Method

Vienna’s example is being adopted by other European cities (Borbíró, 2011). This case study highlights only a few of the designs globally that have mainstreamed gender analysis into urban design and evaluation: 1. At the regional level, the Central European Urban Spaces (UrbSpace) project, supported by the EU’s Regional Development Fund, aims to improve the urban environments of eight Central European countries (Slovakia, Czech Republic, Poland, Hungary, Austria, Slovenia, Germany, and Italy) though renovations of open urban spaces, such as public parks and squares (Rebstock et al., 2011). UrbSpace uses a strategy of integrating the “gender perspective into every stage of the policy process – design, implementation, monitoring and evaluation. (Scioneri et al., 2009). To this end, gender analysis is additionally used as a tool to contribute to other goals: environmental sustainability, public participation in planning, security of urban spaces, and accessibility (Stiles, 2010). For a summary of aspects to consider, see the Urban Planning & Design Checklist.

Gendered Innovation 2: Gender-Aware Housing and Neighborhood Design

Urban designers applying gender analysis have undertaken projects that coordinate design for housing, parks, and transportation to improve the quality of “everyday life.” Innovations in this field include:

A. Housing to Support Child- and Eldercare: Designers recognized that traditional urban design separated living spaces and commercial spaces into separate zones, resulting in large distances between homes, markets, schools, etc. These distances placed significant stress on people combining employment with care responsibilities (Sánchez de Madariaga, 2013). In addition, such design practices often make cars the most practical means of transportation, creating environmental challenges (Blumenberg, 2004)—see Case Study: Climate Change . In response, urban designers have created housing and neighborhoods with on-site child- and elderly-care facilities, shops for basic everyday needs, and often primary-care medical facilities.

Conclusions and Next Steps

The example of Vienna presented in this case study highlights how integrating gender expertise into city planning led to pilot projects, such as Frauen-Werk-Stadt I & II and In der Wiesen Generation Housing that succeeded in incorporating everyday living and caring tasks into the specific housing and neighborhood projects. These projects can serve as a model for larger-scale planning. A next step will involve moving beyond pilot projects toward fully integrating gender analysis into planning and budgeting at the municipal, regional, and national, and regional levels. Further research is also needed to understand how urban structures interact with gender relations, and how these differ across time and space.

Works Cited

Bauer, U.(2009). Gender Mainstreaming in Vienna: How the Gender Perspective Can Raise the Quality of Life in a Big City. Women and Gender Research, 18 (3-4) , 64-72.

Birch, E. (2011). Design of Healthy Cities for Women. In Meleis, A., Birch, E., 7 Wachter, S. (Eds.), Women’s Health and the World’s Cities , pp. 73-92. Philadelphia: Pennsylvania University Press.

Blumenberg, E. (2004). En-Gendering Effective Planning: Spatial Mismatch, Low-Income Women, and Transportation Policy. Journal of the American Planning Association, 70 (3) , 269-281.

Booth, C., & Gilroy, R. (2001). Gender-Aware Approaches to Local and Regional Development: Better-Practice Lessons from across Europe. Town Planning Review, 72 (2) , 217-242.

Borbíró, F. (2011). “Dynamics of Gender Equality Institutions in Vienna: The Potential of a Feminist Neo-Institutionalist Explanation.” Paper Presented at the Sixth Annual European Consortium for Political Research (ECPR) Conference, Reykjavik.

Burton, E., & Mitchell, L. (2006). Inclusive Urban Design: Streets for Life. Oxford: Elsevier Architectural Press.

Greed, C. (2005). Making the Divided City Whole: Mainstreaming Gender into Planning in the United Kingdom. Tijdschrift voor Economische en Sociale Geografie, 97 (3) , 267-280.

Greed, C. (2006). Institutional and Conceptual Barriers to the Adoption of Gender Mainstreaming Within Spatial Planning Departments in England. Planning Theory and Practice, 7(2) , 179-197.

Hayden, D. (2005). What Would A Non-Sexist City Be Like? Speculations on Housing, Urban Design, and Human Work. In Fainstein, S., & Servon, L. (Eds.), Gender and Planning: A Reader , pp. 47-64. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

Horelli, L., Booth, C. and Gilroy, R. (2000). The EuroFEM Toolkit for Mobilising Women into Local and Regional Development , Revised version. Helsinki: Helsinki University of Technology.

Irschik, E., & Kail, E. (2013). Vienna: Progress towards a Fair Shared City. In Sánchez de Madariaga, I., & Roberts, M. (Eds.), Fair Shared Cities: The Impact of Gender Planning in Europe , pp. 292-329. Ashgate, London.

Jarvis, H. and Kantor, P. (2009) Cities and Gender . London: Routledge.

Kail, E., & Prinz, C. (2006). Gender Mainstreaming (GM) Pilot District. Vienna: City of Vienna Municipal Directorate, City Planner’s Office.

Kail, E., & Irschik, E. (2007). Strategies for Action in Neighbourhood Mobility Design in Vienna - Gender Mainstreaming Pilot District Mariahilf. German Journal of Urban Studies, 46 (2).

Magistrat der Stadt Wien. (2012). Alltags- und Frauengerechter Wohnbau. www.wien.gv.at/stadtentwicklung/alltagundfrauen/wohnbau.html

MOST-I: Management of Social Transformations Phase I (2003). Frauen-Werk-Stadt - A Housing Project by and for Women in Vienna, Austria. Paris: United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) MOST Clearing House Best Practices Database. www.unesco.org/most/westeu19.htm

Rebstock, M., Berding, J., Gather, M., Hudekova, Z., & Paulikova, M. (2011). Urban Spaces – Enhancing the Attractiveness and Quality of the Urban Environment: Work Package 5, Action 5.1.3, Methodology Plan for Good Planning and Designing of Urban Open Spaces. Erfurt: University of Applied Sciences, 17.

Reeves, D., Parfitt, B., & Archer, C. (2012). Gender and Urban Planning: Issues and Trends. Nairobi: United Nations Human Settlements Programme.

Reeves, D. (2003). Gender Equality and Plan Making: The Gender Mainstreaming Toolkit. London: Royal Town Planning Institute (RTPI).

Reeves, D. (2005). Planning for Diversity: Policy and Planning in a World of Difference. Abingdon: Routledge.

Roberts, M. (2013). Introduction: Concepts, Themes, and Issues in a Gendered Approach to Planning. In Sánchez de Madariaga, I., & Roberts, M. (Eds.), Fair Shared Cities: The Impact of Gender Planning in Europe , pp. 1-18. Ashgate, London.

Royal Town Planning Institute (RTPI). (2007). Gender and Spatial Planning: RTPI Good Practice Note Seven. London: RTPI.

RTPI. (2007). Gender and Spatial Planning: Good Practice Note 7. London: Royal Town Planning Institute.

Ruiz Sánchez, J. (2013). Planning Urban Complexity at the Scale of Everyday Life: Móstoles Sur, a New Quarter in Metropolitan Madrid. In Sánchez de Madariaga, I., & Roberts, M. (Eds.), Fair Shared Cities: The Impact of Gender Planning in Europe, pp. 402-414. Ashgate: London.

Sánchez de Madariaga, Inés (2004). Urbanismo con perspectiva de género , Fondo Social Europeo- Junta de Andalucía, Sevilla.

Sánchez de Madariaga, Inés and Marion Roberts (Eds.) (2013). Fair Shared Cities. The Impact of Gender Planning in Europe. Ashgate, London.

United Nations (UN). (2010). The Millennium Development Goals Report . New York: UN Publications.

Scioneri, V., & Abluton, S. (2009). Urban Spaces – Enhancing the Attractiveness and Quality of the Urban Environment: Sub-Activity 3.2.3, Gender Aspects. Cuneo: Lamoro Agenziadi Sviluppo.

Ullmann, F. (2013). Choreography of Life: Two Pilot Projects of Social Housing in Vienna. In Sánchez de Madariaga, I., & Roberts, M. (Eds.), Fair Shared Cities: The Impact of Gender Planning in Europe , pp. 415-433. Ashgate, London-New York.

Housing and Neighborhood Design: Analyzing Gender In a Nutshell

Traditionally, cities have separated living and commercial spaces, resulting in large distances between home, daycare, shops, schools, and medical care. In such cities cars often become the preferred means of transportation, creating serious problems for the environment.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

CASE STUDY: Urban Design THE CITY OF MARIKINA CASE STUDY MARIKINA CITY

Related Papers

Civil Engineering and Architecture

Horizon Research Publishing(HRPUB) Kevin Nelson

Peri-urban is commonly defined as an area around the suburban region that has the hybrid characteristics between an urban area and a rural area. The study aimed to investigate the change of regional typology due to the progress of the peri-urban area in Marisa based on the physical and social aspects in 1980 and in 2017. Encompassing two districts, the study employed descriptive-quantitative method and analysis techniques, i.e., overlay, scoring, and spatial. The results showed that in 1980, four districts were included in the rural frame zone (zona bidang desa) category. Moreover, seven sub-districts were categorized as rural-urban frame zone (zona bidang desa kota) while the rest were included in the rural frame zone category. In 2017, a change of typology from rural-urban frame zone to urban-rural frame zone occurred in several villages/sub-districts, i.e., Libuo, South Marisa, North Marisa, and Pohuwato. Over a span of 37 years, the typology of several sub-districts has changed from rural frame zone to urban frame zone in Libuo, South Marisa, North Marisa, and Pohuwato village/sub-district. The urban sprawl in areas in Marisa has increased the need for an integrated policy to create a balanced spatial development.

As two areas directly adjacent to Gorontalo City, the sub-districts of Telaga (Gorontalo Regency) and Kabila (Bone Bolango Regency) are the center of regional growth. The study aimed to examine the physical development of two sub-districts, Telaga and Kabila, since the sub-districts previously mentioned have different regional characteristics and different physical morphology developments influenced by Gorontalo city. That the two sub-districts can be viewed as a peri-urban area of Gorontalo city is a fascinating topic to comprehend the peri-urban area. The stages of this qualitative descriptive research consisted of preliminary survey and observation, distributing questionnaires, collecting data, processing data, data analysis, and data interpretation. Over the last ten years, urban land use has increased in both Telaga and Kabila sub-district by 5% (49.18 ha) and 3% (45.58 ha), respectively. Agropolis activities still dominated the two peri-urban areas. The pattern of land use in the Sub-District of Telaga was the pattern of octopus, while that of Kabila sub-district was a linear pattern (southern part) and frog jump (northern part). Generally, the street pattern in the peri-urban area has a linear path pattern. The development of this peri-urban area seemed unplanned. The situation is understandable since these two areas were initially agrarian villages and hinterland areas of Gorontalo city.

Freek Colombijn

IJESRT Journal

The established economic activity is also influenced by road network patterns and transportation accessibility, to encourage the emergence of new urban activities, activity patterns and movement patterns. The height of land function in the residential area of Marisa is influenced by the ease of accessibility and the demand for residential because it is next to the Central Office district and the urban center. The study aims to (1) Identify components of morphological form comprising land use, road and building network patterns (patterns and densities), (2) Analyzing the morphological form of the old City of Marisa and combine it with characteristic morphological forming components. The methods of research used are qualitative methods of phenomenology. The results showed that (1) the City of Marisa has a characteristic of a village-city frame zone (zobikodes) that is fertile, developing naturally for surplus commodities. The land use pattern of Marisa City, Marisa City Road network, and the patterns and functions of Marisa City are a component of the morphological constituent of Marisa. (2) The City of Marisa forms a compact city i.e. octopus morphology (octopus shaped/star shaped cities) and the custom Tawulongo into local wisdom in organizing the layout of Old Town center Maris

Technology Reports of Kansai University

Antariksa Sudikno

The discussion about a house cannot only be learned from the perceivable physical form, but the house can be a description of the development process of the formation of a family with the social, cultural and economic conditions that underlie it. The physical condition of a residence can also provide an idea of how far the home owner has adapted the technology and culture around him. Family routine activities can also be described in the condition of the existing space configuration in the house. Circulation patterns are intentionally or unintentionally formed from the configuration of space which forms an element of the living space. This is also what happens to community settlements in the Poncokusumo District, Malang Regency. The condition of the area adjacent to Ngadas Village which is very thick with Tengger customs and culture was an interesting reason for the Poncokusumo District as the object of the research. The configuration pattern of the residential space was the result of this research discussion which was analyzed using qualitative methods. house, room, configuration. Key words: house, room, configuration

Journal Innovation of Civil Engineering (JICE)

Jalaluddin Mubarok

Perkembangan perkotaan pada suatu daerah pasti mengalami kemajuan seiring berjalannya peradaban manusia, sehingga pada umumnya perkembangan perkotaan tidak hanya berkembang secara kuantitas atau jumlah penduduk, melainkan juga dari segi perkembangan seni arsitektur, elemen-elemen arsitektur lainnya. Hal ini membuat peneliti merasa penting dalam hal mengkaji dan menganalisa terkait perkembangan perkotaan khususnya pada perkembangan perkotaan menurut teori dari Kevin Lynch yakni Image of the City. Hal ini dilihat dari perkembangannya pasti sudah sangat berbeda dengan teori dan penerapan di perkotaan dan kawasan suatu kota di wilayah tertentu. Hal ini juga mendorong peneliti untuk memetakan terhadap kawasan salah satu perkotaan yang ada di Jawa Timur, yakni kota Malang. Dikarenakan lokasi tersebut berada pada area yang mengalami pertumbuhan dan perkembangan yang sangat pesat, sehingga perlu adanya pengkajian dan pemetaan terhadap elemen-elemen perkotaan yang ada di kota Malang tersebut...

PLANNING MALAYSIA JOURNAL

ILLYANI IBRAHIM

Understanding the urban form is crucial in determining the structure of a city in terms of physical and nonphysical aspects. The physical aspects include built-up areas that can be seen on the earth surface, and the nonphysical aspects include the shape, size, density, and configuration of settlements. The objectives of this study are to (i) analyse the elements of historical urban form that are suitable for the site and (ii) to study on the elements of urban form in Melaka. Content analysis was adopted to analyse the literature of urban form and Melaka. Results show that the following four elements of urban form are suitable to be used for historical urban form analysis: (i) streets, (ii) land use, (iii) buildings, and (iv) open space. The findings also indicate that the selected urban form has successfully delineated in the historical of Melaka as the selected urban elements can be specifically scrutinized with the content analysis. Further study will focus on the historical urban...

Dominador N Marcaida Jr.

This is an updated copy of the profile for Barangay Marupit, Camaligan, Camarines Sur earlier published here at Academia.edu containing additional information and revisions that arose from later research by the author.

irwan wunarlan

IAEME Publication

The Settlement Area in Kampung Aur is a densely populated settlement located on the banks of the Deli River in Medan. Until now there has not been a more appropriate solution to the arrangement of the area and its residents although there are in several cities there have been several types of solutions to the problem of densely populated settlements ranging from forced evictions, the construction of new settlements in the form of flat / flat and village improvement programs. That said, the government began to realize that the problem could not be solved by a one-way system. There must be communication with slum dwellers. This then encourages the authors to make an arrangement of the area and its residents with an approach to the behavior of citizens and the types of settlements at this time. This study aims to produce a design of the area and settlements that can accommodate social and cultural aspects of society through the approach of environmental behavior and types of settlements. To achieve this goal, participatory observation will be carried out in every dominant community in the location. Through this observation it will be seen how the environmental settings and behavior work in Kampung Aur. Data on environmental and behavioral settings will then be processed to produce Kampung Aur design completion criteria. From this study it was found that there are two dominant tribes in Kampung Aur, namely Chinese and Minang.

RELATED PAPERS

Universum (Talca)

Felipe Tello-Navarro

Arfat ahmad Khan

Moulay Ismaili

Revista Brasileira de Ensino de Física

Margarete Domingues

Alejandro Poveda Guevara

CERN European Organization for Nuclear Research - Zenodo

GAY LUMAPGUID

E3S Web of Conferences

Ezozbek TOKHIROV

Jurnal Akuakultur Indonesia

sri nuryati

Polymer Composites

Abdelaziz Lallam

Moran Godess-Riccitelli

Dhiren Panchal

Waste Management

Dimitris Komilis

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health

Jeannette Ickovics

MCN: The American Journal of Maternal/Child Nursing

JIPAGS (Journal of Indonesian Public Administration and Governance Studies)

dine meigawati

Cultures & conflits

Riva KASTORYANO

Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications

Scientific Reports

Hasan Arman

Social Science Microsimulation

Klaus Manhart

Benjamin Kommey

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

- About the Guidelines

- How to Use the Guidelines

- Introduction

- 01. Context

- 02. Building Design

- 03. Collection & Urban Design

- 04. Policy, Research & Implementation Recommendations

- Waste Calculator

- Events + Contact

Battery Park City, NYC

Shared compactor

Best Practice Strategies

- 3.01 Provide loading area at base of a building that can also be used by other buildings

- 3.09 Incorporate community into collection operations

Building staff bringing waste in tilt trucks to shared compactor managed by Battery Park City Authority

The planned high-rise community of Battery Park City is home to 14,000 residents, office buildings and public parks along the Hudson River at the southern tip of Manhattan. The Battery Park City Authority (BPCA) leases land to developers whose buildings must meet special requirements for design, sustainability and community amenities. ← Battery Park City Parks Conservancy, “Who We Are,” link ; Rigorous environmental standards were added in 2000 and updated in 2005. Battery Park City Authority, “Residential Environmental Guidelines” (5/2005), link .

In 2006, construction of the new World Trade Center site led to an explosion in the rat population. The BPCA responded by amending the neighborhood plan to include several shared loading areas equipped with 35 cu yd compactor containers. Just as building developers were required to provide open space, schools and other amenities, developers of specified sites were required to host compactor containers managed by the Battery Park City Authority. Instead of piling bags of refuse on the sidewalk two days a week for pickup the next morning, porters could now deliver bags to a shared compactor each day. Instead of a compactor truck stopping to load bags from every school and residential building in the neighborhood, roll-on/roll-off trucks collect compacted containers from just four locations.

Compactors can hold 150 carts’ worth of material. Each compactor manages material from about 2,000 units and takes about 90 minutes to load each day. Not only has the strategy addressed the rat issue, but it has also been popular with porters. ← Cheryl McMullen, “How a Compacting Program for NY’s Battery Park City Has Improved Quality of Life,” in Waste 360 (5/18/2017), link ; Bill Egbert, “Sanitation Salvation? Battery Park City May Hold the Key to Conquering Downtown’s Garbage Glut,” in Downtown Express (6/16/2016), link .

In Battery Park City shared compactor containers are used only for refuse. Metal, glass, plastic, paper and cardboard are still collected door-to-door with rear-load compactors, as are organics from buildings that participate in the city’s organics-collection pilot. Additional loading area space—or separate time windows allocated to each waste fraction—would be required in order to include these source-separated streams in the consolidated-collection system.

The fact that BPCA controls leasing arrangements for the entire development facilitated the shift from door-to-door pick up to consolidated collection. The fact that new developments were in the planning stages made it convenient to install curb cuts in locations that would provide truck access to the shared compactors. Shifting to shared loading docks in existing neighborhoods with multiple private parcel-owners would require coordination between property owners to achieve these ends.

Roosevelt Island, NYC

Pneumatic collection

3.03 Provide a system of pneumatic tubes connecting buildings to a central terminal

Residential trash from all buildings, except the Cornell Tech campus, is collected by pneumatic tube

Operations diagram by Gibbs and Hill engineers showing how waste flows from chutes in individual buildings through a pneumatic tube to a shared compactor container, 1971

Roosevelt Island is a planned community of 14,000 in the East River, between Manhattan and Queens. The 1969 master plan by Philip Johnson and John Burgee envisioned a full-service community without cars. Tasked with finding a way to remove trash without trucks, engineers installed a pneumatic tube network—the first such system for municipal solid waste in the United States. Trash chutes in the island’s 16 residential complexes are connected via pneumatic tube to a terminal at the islands’s north end. Several times a day, turbines at the collection station are turned on, generating a vacuum. Valves at the bottom of the chutes are opened and trash flows at 50 mph to the terminal, where it is compacted into containers and collected by roll-on/roll-off trucks. ← See Fast Trash: Roosevelt Island’s Pneumatic Tube and the Future of Cities (2010), link .

The system, which has been in continuous operation since the first residents arrived in 1975, has been expanded three times to accommodate new development. The island is managed by the Roosevelt Island Operating Corporation (RIOC), a public benefit corporation of New York State. All developers who lease land from RIOC must connect their buildings to the pneumatic network. As a result, building porters on the island do not manage refuse, and buildings do not provide storage areas for waste. Residents often become aware of the network only on the rare occasions that the system is shut down and bags are piled on the curb, as they are in most New York City neighborhoods. Because collection occurs off the street and without trucks, Roosevelt Island was the sole neighborhood in the city whose DSNY service continued during Hurricane Sandy and the blizzard of 2012.

Because the system was built before curbside recycling was required, recycling is not managed by the system. Newer systems incorporate multiple fractions. (See Vitry-sur-Seine case study, below .)

The Roosevelt Island network also does not collect refuse from businesses, because they must contract with private carters. As a result, the system does not run at full capacity.

Vitry-sur-Seine, France

- 3.03 Provide a system of pneumatic tubes to connect buildings to a central terminal

Residents depositing household waste in an inlet on the sidewalk

Vitry-sur-Seine is a diverse city of 90,000 outside Paris where 75% of residents live in apartment buildings, a third of which is public housing. In 2008, as the city embarked on a major urban renewal project to improve conditions in several of its public housing estates and to develop an interurban tramline, Vitry was also revisiting its waste management plan; it was looking for ways to encourage recycling and reduce the noise and traffic congestion associated with waste collection. After touring Barcelona’s pneumatic networks, the mayor requested that a study of tube collection be done for the renewal project, with the possibility of connecting other neighborhoods in a later phase. ← Anne Allain and Bruno Allioux, Pneumatic Waste Collection in Vitry-sur-Seine (presentation, International Pneumatic Waste Collection Association seminar, Barcelona Smart City Expo World Congress, 11/16/2016), link .

The first-phase of the system, which will serve an eventual 10,000 apartments, began operation in 2015 and now serves 1,200 apartments, small businesses and a school. Most of the 60 input points activated so far are adjacent to building entrances. (Residential inlets are located outside buildings but on private property, to encourage residents and building managers to take ownership of the inlets and reduce maintenance issues.) Vitry’s system currently collects two streams—mixed recycling and refuse—but was designed to allow for a potential third stream: organics. (Glass and bulk items are collected separately.) ← City of Vitry-sur-Seine, “Collecte pneumatique: le réseau s’étend” (9/30/2016), link .

The terminal sits on narrow parcel between two streets. In order to have enough room for trucks to load inside the small facility, containers are filled underground and raised with a crane bridge to a single street-level loading dock. Large picture windows allow passersby to see into the facility, with the tubes and turbines of its otherwise invisible network.

Some funding for the 32 million euro pneumatic network came from the regional waste authority; the rest was financed by the city via a 5% increase in collection fees implemented over several years. Vitry launched its pneumatic system with a communications campaign that included home visits to 80% of the residents whom the new network would serve. A recent city survey showed the response from residents was overwhelmingly positive. Vitry’s project manager is pleased with the service but notes that the network has not improved separation of recyclables and that more education and outreach is necessary.

- Vitry’s pipes were installed in existing streets and sidewalks. Inaccurate below surface survey data caused significant delays and cost increases as the pipes had to be rerouted.

- Contract negotiations were made more challenging by the fact that relatively few manufacturers submitted bids.

Applicability to NYC

New York City could take advantage of large-scale urban renewal and transit projects to install infrastructure that would reduce the impacts of truck collection. Surveys will be critical for any project taking place below city streets. (See The Hague case study, below, on planning for existing conditions.)

Study of High Line Corridor Pneumatic Waste-Management Initiative, NYC

Pneumatic collection, shared containers

3.04 Provide a system of pneumatic tubes connecting shared inputs to a central facility

Overview of district-scale system and potential area it could serve

Linear rights of way and transportation infrastructure such as the High Line could be used to insert pneumatic collection into existing neighborhoods

The High Line viaduct was originally built to bring freight into West Chelsea factories by rail. It is now an iconic park surrounded by residential development and offices. Soon it could channel waste out |of the neighborhood and directly onto railcars via pneumatic tube.

The High Line Corridor Pneumatic Waste-Management Initiative proposes a third chapter for the High Line in which building staff and cleaning crews from the local business improvement district cart waste to shared containers connected to a 1.5-mile long pneumatic tube attached to the underside of the High Line. Recyclables, organics and refuse would be pulsed at different times to a collection terminal at the north end of the High Line, compacted into shipping containers and sent by rail to processing and disposal facilities. Space beneath the shared containers could be used as micro-distribution centers for local last-mile package delivery—or to host cardboard balers or drop-off bins for e-waste and textiles. These parking space-size transfer hubs, or shared utility closets, could be located anywhere within reach of the High Line viaduct, including in the loading docks of the large former-industrial buildings the High Line was built to serve. This concept could be replicated in neighborhoods along any of the city’s elevated-subway, rail or roadway viaducts, or shallow (cut-and-cover) subway lines. In addition to the primary trunk line for the three postconsumer streams, a smaller pneumatic tube could be affixed to the High Line to send food scraps from restaurants and food businesses along the corridor to micro-anaerobic digesters, to produce energy for local use.

The New York State Energy Research and Development Authority (NYSERDA) and New York State Department of Transportation have co-funded an effort led by ClosedLoops to advance project pre-planning from the preliminary feasibility/cost-benefit analysis stage (which is already completed) toward potential implementation. The goals of the current project phase are to identify structurally and operationally viable design solutions for installing pneumatic collection along the High Line; to determine optimal operating and ownership models for the shared infrastructure; and to develop the analyses of public and private costs and benefits that are necessary for project financing. 32 The current initiative evolved through meetings and site visits with community groups, property owners and city agencies. If implemented, it could be a model for community engagement in planning for district-scale waste management. ← Cole Rosengren, “Below the High Line: How pneumatic tubes could alter the future of urban waste collection,” in Waste Dive (4/6/2017), link .

- Multi-stakeholder process involving many properties and city agencies

- Securing space for transfer hubs and collection station

- Business model and project financing

Paris Trilib’

Shared surface container on curb

- 3.05 Shared surface containers in the public realm or on agency property

- 3.08 Design streetscapes that allow curbside access to containers

Paris is a low-rise city with one of the highest population densities in Europe. Most buildings are six stories or fewer. Residents are accustomed to bringing their waste and recyclables down to street-level receptacles inside their building. Each morning or night, building staff roll bins from courtyards and entryways to the curb for collection by semi-automated trucks. Paris collects three streams curbside—refuse, recyclables and glass— and may add a fourth: organics (an organics collection pilot was started in two districts in 2017). Meanwhile, many buildings do not have room to store enough wheeled bins to manage the volume they generate. Citywide, 30% of buildings have no receptacles for glass, and 15% still provide only refuse bins. ← City of Paris, Annual Report on Sanitation Service, 2015,” 39, link ; City of Paris, Annual Report, 60.

While hosting the United Nations Climate Change Conference in 2016, Paris set out to expand access to recycling collection by introducing a new kind of street furniture. In the spirit of the city’s wildly popular bike sharing program, Vélib’, the new recycling kiosks are called Trilib’ (from trier , “to sort”). The kiosks have foot pedal–operated openings on the sidewalk side and a street-facing door from which sanitation crews remove a wheeled container. Trilib’ kiosks include four to six modules providing access to up to five streams: metal and plastic packaging, paper and small cardboard, glass, textiles and large cardboard, each color-coded with its own type of opening. The number and type of containers varies depending on waste generation characteristics in the immediate area. ← “Paris Teste le Tri de Demain : Trilib,” Eco-Emballages blog (undated), link .

Trilib’ is designed to address a number of issues beyond a lack of storage space within buildings and low recycling rates. These other objectives include giving recycling new legitimacy as an activity deserving of a prominent location in public space and normalizing drop-off down the street as a complementary practice in a city used to door-to-door pickup. The repurposing of parking spots for new kiosks also reinforces the city’s commitment to shifting space away from cars. ← Correspondence with Léon Garaix, deputy director, Paris Office of the Deputy Mayor for Sanitation (7/19/2017).

In 2017, as part of a pilot program, 40 Trilib’ stations were installed in four urban contexts: superblocks of apartment towers, town houses, major public spaces and the historic city center. Preliminary results are encouraging. The volume of material collected via Trilib’ has increased from 50 tons the first month to almost 80 by the sixth. The city envisions installing 1,000 stations by 2020 and is contemplating adding additional containers for other types of material. ← City of Paris, Annual Report on Sanitation Service, 2015,” 39, link .

- Capacity: The project team is looking at ways to redesign the kiosks to increase capacity and reduce collection frequency, particularly for bulky materials like cardboard. ← City of Paris, Annual Report on Sanitation Service, 2015,” 39, link.

- Bulky cardboard: Initially, a large opening was provided for bulky cardboard, but this led to problems with overflowing and contamination. Kiosks were modified with a slot opening similar to a large mailbox’s, which seems to be working.

- Noise: The first glass containers were too noisy. The problem was solved by adding sound insulation.

Specially designed surface containers could be installed in public plazas or parking spaces to expand access to recycling in NYC neighborhoods where there is not adequate space for waste storage. Reconceiving bins as public amenities akin to bike-sharing equipment, as Paris has done, could be helpful in siting drop-off stations for a range of materials.

The Hague, Netherlands

Submerged container

Best Practices

- 3.06 Shared submerged containers in the public realm or on public agency property

Truck removing container

The Hague is the Netherlands’ third-largest city. Until recently, door-to-door collection of refuse in bags or wheeled bins was the norm, with residents carrying recyclables to shared containers on certain “recycle streets.” The city struggled to keep its narrow streets clean because seagulls pecked open bags left out for collection, strewing garbage and making a mess. In 2009, The Hague decided to address the issue by replacing bags on the curb with shared containers submerged under the sidewalk. Although the city anticipated some operational efficiencies, its primary objectives in selecting a submerged container system were to improve public and health and hygiene, enhance public space aesthetics and provide an opportunity for residents dispose of refuse 24/7 instead of having to store the material in their small apartments until pickup day. (Recycling is already collected at drop-off locations.) ← The city found reduced litter where submerged containers were used. “Plans for More Underground Waste Containers,” in The Hague Online (7/25/2012), link ; Arjen Baars (director, The Hague Environmental Services) and Richard van Coevoorden (project manager, Department of City Management of the City of The Hague), correspondence with Juliette Spertus, 6/22/2017. Coordinated and translated by Tessa Vlaanderen.

The Hague began switching to submerged containers in 2010 with a plan to install more than 10,000 units in three phases over ten years. In 2017, there were 6,100 below ground units. Eventually, all collection in The Hague will shift to underground containers. The containers are designed to be within convenient walking distance (250 feet [75 meters]) of a residential building’s front door. (If necessary, the containers may be installed at distances up to 410 feet [125 meters].) Each 6.5 cu yd container serves an average of 35-38 households. They are emptied twice weekly and are cleaned, inside and out, twice a year. Equipment is checked once a year. ← The Hague is technology-neutral and has ten-year contracts with multiple vendors. Arjen Baars, 6/22/2017.

The installation process is described in detail on the city’s website. Container location plans are made in collaboration with the municipal committee for public space (an entity composed of key street infrastructure stakeholders, which coordinates short-, medium- and long-term planning), the departments of transportation and environmental services. The city digs test pits in chosen locations to survey underground conditions and informs local residents of the plans. Area residents have the right to object, and if their objections are not resolved to their satisfaction, they can appeal in court. (This has happened in 10% of the cases.) Community outreach occurs at several levels: Information is available online and letters are sent to all residents to explain why the change is being made. During the neighborhood information evenings that are organized to discuss plans with the community, residents can volunteer to be responsible for a submerged container and receive the tools to repair basic jams. Volunteers are usually the first to call when issues arise.

The primary operational change for collection personnel is that truck crews are reduced from three to one, and some training is needed to provide the skills needed to manage the equipment. The shift to submerged containers has led to improved working conditions and reduced labor costs. A shift from fixed routes to a flexible “smart schedule” based on sensors will be implemented next. ← One sanitation worker would be possible, but the perceived security risk and difficulty of maneuvering narrow streets made them keep two. Arjen Baars, 6/22/2017.

Although litter is reduced, the city maintains a cleaning crew to address the 2–3% of locations where bags are improperly discarded beside containers. There is a fine for illegal dumping, but identifying an owner is nearly impossible. Community involvement and ownership is the most powerful solution. ← Arjen Baars, 6/22/2017.

New York City is similar to The Hague in that it is a dense city with infrastructure and utility systems running under its streets. The Hague’s implementation process, involving coordination among key street infrastructure agencies, with test pits to check field conditions, would be appropriate in NYC as well. DSNY’s existing Adopt-a-Basket program could be expanded to include training volunteers to be first responders who could resolve minor maintenance issues with their “adopted” submerged containers. (See BPS 3.06 for collection considerations.)

Punt Verd, Barcelona

Neighborhood-scale recycling center in public realm

Best practices

- 3.07 Staffed drop-off locations

Plan showing containers arranged around a public drop off area with service access around the perimeter

Punts verds (Catalan for “green points”) are small recycling centers installed in plazas and parks. Barcelona developed the semi-permanent staffed facilities to provide residents with opportunities to drop off household hazardous waste, recyclables and smaller bulk items within walking distance of their homes. Punts verds complement larger recycling centers with vehicle access on the outskirts of the city. In 2016, the city’s 23 neighborhood-scale punts verds managed over 2,000 tons of material. ← See Neighborhood Punts Verds labeled “B” in location map, City of Barcelona, Xarxa Punts Verds, link .

The facility design is simple: containers are arranged in such a way that they are accessible for deposits by the public on one side and for emptying by staff on the other. The center is protected from the elements and secured with fences. The only interior spaces are a small office with a restroom for staff and a tiny visitor’s center. Punt verds are designed to be eye-catching to encourage their use and to add visual interest to the surrounding public space. They also provide an opportunity to showcase sustainable design. The modular facility installed in Barceloneta Park in 2013, by Picharchitects, features a planted enclosure and requires little energy for operations: Roofs protecting the drop-off area capture rainwater and fill cisterns used to irrigate planters; solar panels and passive systems generate electricity and hot water. ← Picharchitects, “In Process: Punt Verd, Nuevo Modelo de Punto Verde en la Barceloneta,” Picharcthitects (blog, undated), link .

Architect Felipe Pich-Aguilera Baurier explains: This is not a conventional project. Every aspect had to be invented from scratch to break with the conventional image of a waste plant. A waste project is always subject to “industrial” constraints, such as accommodating truck logistics and ensuring that the site is protected from contamination. For this project, very restrictive safety and hygiene measures were also necessary to ensure coexistence within the urban fabric. As a result, projects tend to be isolated like “bunkers” and would be intimidating to pedestrians and neighbors. Our project tries to achieve a domestic-scale result that can be a meeting place for the neighborhood, while addressing all of the program requirements.

Given that the installation is located at the edge of an urban park, we have tried to design the largest elements so that they assimilate directly with the natural landscape that surrounds them and ensure that no permanent mark is left on the ground. To do this, all the components have been manufactured offsite and assembled so that the facility can be dismantled and removed. ← Note from architect, Felipe Pich-Aguilera Baurier, 9/2017. Translated and edited by Juliette Spertus.

New York City runs SAFE disposal events throughout the five boroughs, where the events are typically well attended and waiting lines can last for hours. Research elsewhere has shown a spike in trash disposal of hazardous waste on days following collection events. Permanent facilities providing predictable, ongoing access to collection could capture a larger portion of materials designated for diversion from regular disposal.

Ménilmontant, Paris

Recycling center and relay point for bulk collection hosted on private property

Best practice Strategies

Section perspective showing vehicles driving into the recycling center adjacent to the gym

Diagram showing the various program elements

View showing pedestrian-oriented context

Plan of basement level; municipal vehicles stage material in large containers while the public drops off at small containers the length of the exterior wall

The City of Paris and Paris-Habitat OPH, a public housing management company, are building a new mixed-use residential complex of 87 units in the Ménilmontant neighborhood of the 20th arrondissement. In addition to the more conventional park and sports complex, the project, designed by Atelier Nadau Lavergne, includes a staffed recycling center or “espace tri”, as well as a hub for aggregating truckloads of bulk materials picked up by appointment from local collection routes. Parisians are already required to bring household hazardous wastes and other material not collected curbside to an espace tri, where materials are staged and sorted before being sent to processing or disposal facilities. These centers tend to be open-air facilities in industrial areas around the expressway that circles the city, with difficult pedestrian access. ← Nadau Lavergne website, link .

The 15,000-square-foot espace tri was included in the program for a mixed-use building in an effort to bring recycling centers closer to where people live and design them in ways that minimize impacts from their operation. The hub for aggregating loads of bulk materials, called the Point Relais d’Encombrant, will reduce miles logged by collection trucks, in turn decreasing congestion and air emissions. By 2020, every arrondissement will have a center—coordinated by a partner organization—where residents will be able to take items for reuse as well as recycling and disposal. To reach this goal, the City will build ten new espaces tri, including the one in Ménilmontant, the first to be located in a residential complex. ← “Une déchèterie sous le sol de Paris,” in Environment Magazine (9/23/2015), link ; Laetitita Van Eeckhout, “Très mauvais élève, Paris se lance vers le ‘zéro déchet’” in Le Monde (2/16/2016), link .

The project team must reassure neighbors that any negative impacts from this new type of facility will be mitigated.

New York City does not have a network of neighborhood-scale facilities collecting household hazardous waste and other non-daily streams. Both the Ménilmontant and Barcelona programs offer convenient and reliable access to neighborhood drop-off facilities. City agencies could specify that publicly funded projects host such facilities, along with the logistics support required to operate and maintain them. (See the Punt Verd case study, above .)

GrowNYC Compost On-The-Go Program, NYC

Staffed drop-off locations in the public realm

Best practice

- 3.07 Provide staffed drop-off locations.

Commuter drop off at transit hub

Dedicated New York City gardeners have composted in their community gardens for decades as a way to improve soil for flowers and vegetables. In 1993, the New York City Department of Sanitation created the NYC Compost Project to leverage this interest in composting and began formally training community gardeners through the city’s botanical gardens to become certified master composters. DSNY has since expanded the scope of the compost project to help develop organics collection and processing capacity in the city with the Local Organics Recovery Program (LORP). LORP sites collect food scraps from the larger community and process them in their urban compost sites.

Concurrently, DSNY began funding collection programs in farmer’s markets, parks, libraries and commuter drop-offs at subway stations. These drop-offs are intended to complement curbside collection, providing convenient access to organics collection for all New Yorkers by 2018. ← Nora Goldstein, Part I: “Community Composting in New York City” (1/2013), link , and Part II: “Greenmarkets Facilitate Food Scraps Diversion in NYC” (2/2014), in BioCycle, link ; NYC DSNY, “NYC Organics Collection: Neighborhoods Served,” link .

The newest DSNY-funded food scrap drop-off effort is called Compost On-The-Go, operated by GrowNYC, DSNY’s nonprofit partner. GrowNYC compost coordinators set up a tent with bins or crates for organics and a refuse bin for any plastic bags used to transport material. For commuter drop-offs, bins are placed on street corners near a subway entrance in time for the morning rush hour. In addition to managing the bins, coordinators provide education and outreach about the importance of organics diversion in NYC. Commuters tend to travel at the same time each day, so volumes increase from week to week as people learn about the program and start saving their food scraps for drop off on their way to work.

Citywide, there are now 106 food scrap drop-off sites. ← Correspondence with DSNY, September 2017.

Unlike the curbside program, in which organics are treated in industrial facilities, the drop-off program often uses urban compost facilities and gardens that are only allowed to accept plant-based material. ← GrowNYC, “Compost Food Scraps,” link .

With support from

FutureVU: Sustainability

Vanderbilt and Civic Design Center’s impact on Nashville’s urban evolution

Posted by hamiltcl on Friday, May 24, 2024 in News .

For over 24 years, the Civic Design Center has stood as a beacon for community-driven urban planning projects and programs. Based in downtown Nashville, this nonprofit organization draws expertise from diverse professional and academic sources, including Vanderbilt University, to engage community members in the envisioning and shaping of the city. Since its formation in 2000, the Civic Design Center has maintained a strong bond with Vanderbilt.

Originating from grassroots opposition to a highway project in the 1990s, the Center emerged not just as an advocacy group but as a symbol of what collective vision can achieve. Former Nashville mayor and current adjunct faculty member Bill Purcell envisioned a civic design center that would form a new narrative in urban planning, with a mission to bring design-focused change that would endure for generations.

To shepherd the budding organization toward its goals, Vanderbilt University loaned James Sandlin to serve as the first executive director. Sandlin worked alongside the University of Tennessee, Knoxville’s Mark Schimmenti, who took on the role of the first design director. These early leaders exemplified the Center’s emphasis on collaborating with higher education institutions.

In 2004, the research of the advocacy group culminated in the publication of The Plan of Nashville: Avenues to a Great City , a comprehensive strategy for the urban future of Nashville, published by Vanderbilt University Press.

“Vanderbilt has been one of our strategic partners since the very beginning of the Civic Design Center’s history,” shares Gary Gaston, MED’17, Civic Design Center CEO. “The breadth at which we collaborate across university departments is a model of academic and nonprofit collaboration.”

“The impact of our combined efforts has significant positive ripple effects on the quality of life for Nashvillians of all ages. Our mentees, interns and fellows from Vanderbilt have each left their mark on the city and we know they continue to do great things as they move forward in life,” Gaston says.

A Vanderbilt alumnus, Gaston earned a master’s degree in community development and action from Peabody College of education and human development.

The long-standing partnership has continued through the contributions of Vanderbilt faculty and staff serving on the Center’s board of directors, including current board member Eric Kopstain , vice chancellor for administration.

This collaboration extends beyond administrative ties, enriching both students and the community. Vanderbilt students serving as interns and research fellows find themselves immersed in real-world projects with tangible impacts, enhancing their academic journeys and preparing them for future leadership roles in civic engagement.

“So many of our students have had opportunities to learn through involvement with the Civic Design Center while we work toward shared goals of more civic participation and more sustainable and equitable urban development,” adds Peabody College professor of human and organizational development and director of graduate studies Brian Christens .

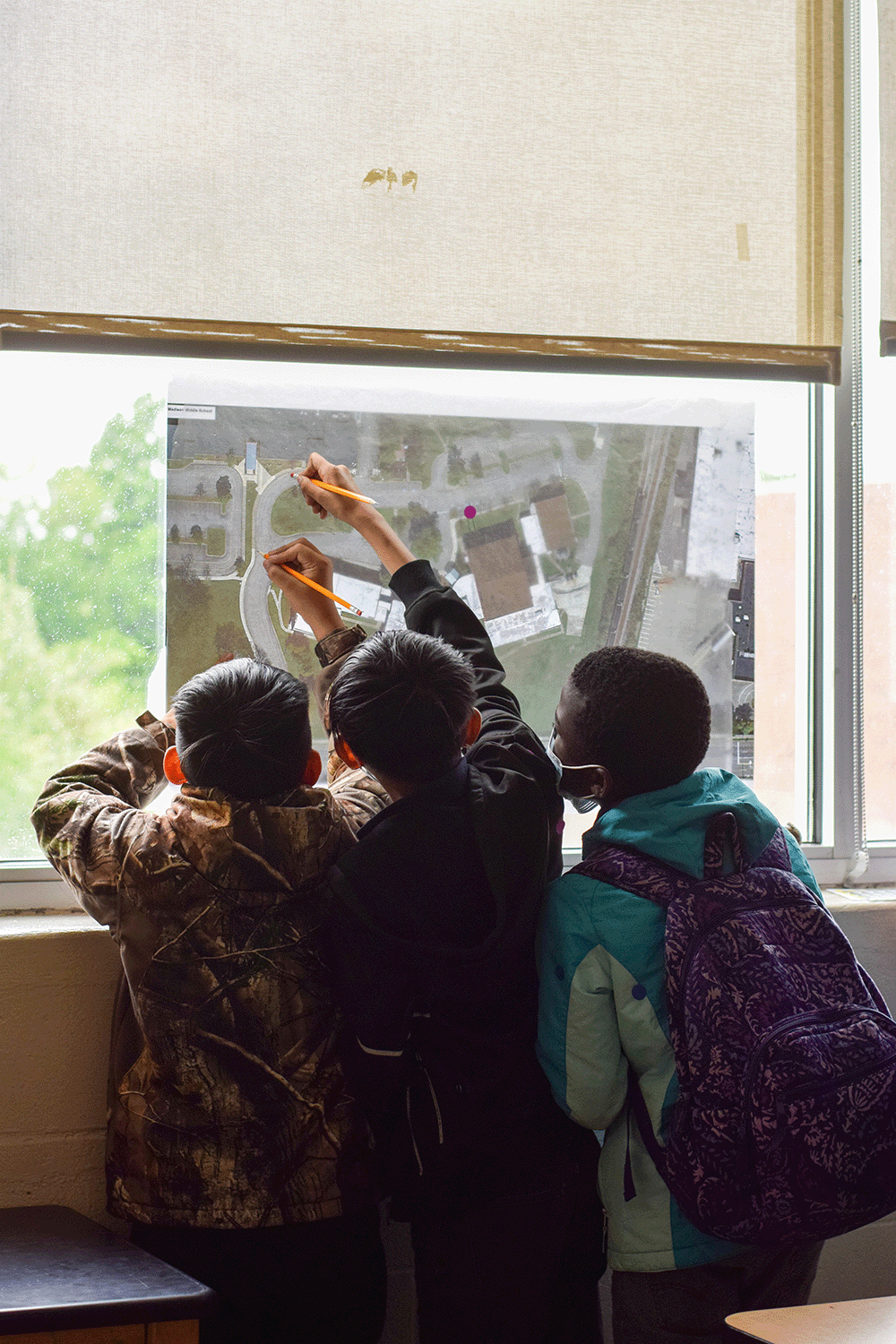

Among the notable initiatives facilitated by this partnership are the Design Your Neighborhood and Nashville Youth Design Team programs, empowering local youth to actively shape their city’s future through education, research and advocacy. Katy Morgan, PhD‘22, and current doctoral students Kayla Anderson and Megan McCormick have been instrumental in creating and developing these initiatives.

Civic Design Center Education Director Melody Gibson partnered with Morgan, Anderson and McCormick, along with Professor Brian Christens, and the Vanderbilt Institute of Visual Research’s Natalie Robbins and Stacy Curry-Johnson on a recent study that examined the influence of the built environment on youth well-being. The Nashville Youth Design Team conducted a Youth Wellness survey among middle and high school students across Davidson County. The survey data served as the basis for a spatial analysis that provided insights into how various environmental factors influence youth well-being in Nashville.

According to Gibson, “The Civic Design Center has been able to use the research capacity from the Peabody graduate students and implement it into our daily programming, which has allowed our community engagement to be continually grounded in research and community empowerment over the years.”

The Civic Design Center’s influence also extends to the School of Engineering. Professor Lori Troxel ’s engineering students have collaborated with the Center on innovative civil engineering solutions to encourage sustainable and community-focused urban development projects including urban parks, affordable housing opportunities and revitalizing underutilized city road connections.

In 2012, Joe Bandy ’s sociology class, Environmental Inequality and Justice, collaborated with the Center on a study of various Nashville neighborhoods and their environmental health factors. This community-based research informed the Center’s publication, Shaping the Healthy Community: The Nashville Plan , released in 2016.

These examples are just a small window into the decades of partnership between Vanderbilt and the Civic Design Center. This collaborative alliance has been instrumental in connecting the university to the Nashville community in a period of significant growth and change in the city, championing urban design solutions that facilitate both continual learning and civic engagement.

Tags: climate change , featured , Land Use , Research , Transportation

Comments are closed

- Annual Report

- What You Can Do

- Subscribe to Newsletter

Quick Links

- PeopleFinder

- Hispanoamérica

- Work at ArchDaily

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

Multi-Use Public Spaces and Urban Design: Copenhagen and Social Integration

- Written by Eduardo Souza

- Published on December 02, 2022

"Life, space, buildings - in that order". This phrase, from the Danish urban architect Jan Gehl , sums up the changes that Copenhagen has undergone in the last 50 years. Currently known as one of the cities with the highest levels of quality of life satisfaction, the way its public spaces and buildings were and are designed have inspired architects, government authorities and urban planners around the world. What we see today, however, is the result of courageous decision-making, much observation and, above all, designs that put people first. Copenhagen will be the UNESCO-UIA World Capital of Architecture in 2023 as well as host of the UIA World Congress of Architects due to its strong legacy in innovative architecture and urban development, along with its concerted efforts in matters of climate, sustainability solutions and livability.

But those who think the city's mentality has always been like this are mistaken. During the 1960s and 1970s, Copenhagen did as most large European cities did, building highways and developing essentially modernist plans, such as the Finger Plan of 1948, which foresaw the urban development of the metropolitan area concentrated linearly alongside a network of 5 major arteries of roads and railroads. The plan, however, did not come to fruition , mainly because Denmark did not have the financial resources at the time –coming out of World War II–, causing the city to take another direction in the following decades.

As Gehl describes it in his book Cities for People , after years of restricting pedestrian spaces in favor of automobiles, in 1962 Copenhagen simply converted the city's traditional main boulevard, Strøget, into a pedestrian walkway. This prompted enormous criticism and skepticism, which targeted, above all, the harsh local climate and the more reserved personality of the Nordic people. What the data proved, however, was a 35 percent increase in the number of pedestrians in the first year alone, and by 2005 the area dedicated to pedestrians and city life had increased sevenfold. This is Jan Gehl's most important contribution to the field of urbanism: working on projects that focus on people (their scale, demands, and particularities) and, along with this, developing methods to measure, quantify and qualify urban spaces.

Public space plays a fundamental role in city life. It is a space for human contact, for meetings between different cultural and social groups, and where planned and spontaneous social interactions can occur. It consists of parks and squares, but also of the streets themselves, which in Copenhagen have the distinction of an extensive and connected network of bicycle paths. This is yet another break that the city has made with the modern design of large highways and dependence on fossil fuels. Cycling is, without a doubt, the best way to get around the city, with more than 40% of its inhabitants using bikes on a daily basis. Pedestrians and cyclists are important for what Jane Jacobs called the "eyes of the street". Because they move at lower speeds and are fully integrated into the urban environment, cyclists become natural observers and engage more with each other and with the attractions offered by the city. Well-designed public spaces make for healthier, more creative and inclusive cities, where regardless of economic status, gender, age, ethnicity, or religion, everyone can participate in the opportunities that cities offer.

One example is the Copenhagen waterfront. The water of the harbor has been treated and is now so clean that it is suitable for swimming. This has created a number of new leisure and living options for the inhabitants , with water sports, urban beaches, and floating structures that are extremely popular with residents and tourists alike. Copenhagen Harbour Bath, designed by BIG + JDS and Kalvebod Waves, by JDS + KLAR are two examples of singular structures, with good architecture, that create movement and new urban amenities in their surroundings.

Town squares have also acquired a special kind of protagonism in Copenhagen's urban spaces, creating areas of conviviality and leisure in everyday life. Israels Plads Square exemplifies well the transformations that the city has undergone. From a vibrant historic open-air market, the square became a lifeless parking lot in the 1950s. The new square, built in 2014, is elevated above the existing street level, keeping the cars underground while creating a large urban playground and activity area above. Another prominent urban attraction is Superkilen . Located in one of the most ethnically diverse and socially challenged neighborhoods in Denmark, the plaza takes a unique approach: it brings in elements from around the world, through objects, textures and colors. As the project designers, Topotek 1 + BIG Architects + Superflex, point out, “A sort of surrealist collection of global urban diversity that in fact reflects the true nature of the local neighborhood – rather than perpetuating a petrified image of homogenous Denmark.”

Yet another lesson from Copenhagen is that you can include community spaces even in the most unusual places. This is the case of Park 'n' Play, by JAJA Architects , which transforms a parking building into an asset for the city, with an active green façade and a rooftop playground. The famous CopenHill Energy Plant and Urban Recreation Center by Danish firm BIG , on the other hand, uses a functional infrastructure building as an artificial mountain where you can even go skiing.

The Danish capital demonstrates to the world that there are realistic solutions for commuting and urban public spaces in large cities, without requiring huge open areas or complex road infrastructures. To do this, it combines in a compact and dense city, a network of public spaces, sustainable mobility, and the human scale. This and other examples of successful public spaces show that a focus on people, their scale and demands is much more important than huge urban plans or imposing skylines.

For more information and tips about the city, go to VisitCopenhagen .

Image gallery

- Sustainability

想阅读文章的中文版本吗?

多用途公共空间和城市设计:哥本哈根与社会一体化

You've started following your first account, did you know.

You'll now receive updates based on what you follow! Personalize your stream and start following your favorite authors, offices and users.

We apologize for the inconvenience...

To ensure we keep this website safe, please can you confirm you are a human by ticking the box below.

If you are unable to complete the above request please contact us using the below link, providing a screenshot of your experience.

https://ioppublishing.org/contacts/

Mobility as a Response to Urban Floods and Its Implications for Risk Mitigation: A Local Area Level Case Study from Guwahati, Assam

- First Online: 29 May 2024

Cite this chapter

- Upasana Patgiri ORCID: orcid.org/0009-0004-5385-1527 8 ,

- Premjeet Das Gupta ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8647-6162 9 &

- Ajinkya Kanitkar ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0862-4187 10

Part of the book series: Climate Change Management ((CCM))

Detrimental effects of climate change and development pressures resulting in hazardous disasters have been a grave challenge of the current Anthropocene. Floods, a common global disaster, are posing a major threat to a large percentage of urban population due to increasing frequency and intensity. Prima facie, the inundations are usually short-term disruptions in case of urban floods. However, research indicates individuals alter their travel behaviour during floods. Mobility is an essential part of human life and when disrupted due to such events can prompt individuals to engage in risk-taking and evacuation behaviours, influenced by various socioeconomic as well as environmental factors. It is vital to comprehend human mobility patterns in both regular and unusual circumstances, from a purview of urban vulnerability, resilience, and sustainability. For this research, the travel behaviour study undertaken at a neighbourhood in Guwahati, Assam, analysed risk taking and evacuation behaviour during floods based on Mobility as a Response (MaaR) framework, comprising built environment, transportation, behavioural control, information-seeking and social response during floods. The primary survey involved collection of data through a structured questionnaire administered to 105 individuals. The analysis techniques include Chi-square and Spearman Rank Correlation tests. The findings suggest that risk taking, and relocation behaviour varies across different demographic and socioeconomic groups and the challenge of accessing various transportation modes and a lack of viable alternative routes for vehicles and pedestrians show a significant correlation with both relocation and risk-taking behaviours.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Institutional subscriptions

Adeola FO (2009) Katrina cataclysm: does duration of residency and prior experience affect impacts, evacuation, and adaptation behaviour among survivors? Environ Dev 41(4):459–489. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916508316651

Article Google Scholar

Ahmouda A, Hochmair HH, Cvetojevic S (2019) Using twitter to analyze the effect of hurricanes on human mobility patterns. Urban Sci 3(3):87. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci3030087

Ajibade I, McBean G, Bezner-Kerr R (2013) Urban flooding in Lagos, Nigeria: patterns of vulnerability and resilience among women. Glob Environ change 23(6):1714–1725

Google Scholar

Ajibade I, Armah FA, Kuuire VZ, Luginaah I, McBean G, Tenkorang EY (2015) Assessing the bio-psychosocial correlates of flood impacts in coastal areas of Lagos, Nigeria. J Environ Plan Manag 58(3):445–463. https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2013.861811

Alam K, Rahman MH (2014) Women in natural disasters: a case study from southern coastal region of Bangladesh. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct 8:68–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2014.01.003

APCB (2013) Conservation of river Bharalu, preparation of detailed project report, city sanitation plan. The Louis Berger Group, Inc., and DHI (India) Water and Environment Pvt. Ltd., Guwahati

Ashley ST, Ashley WS (2008) Flood fatalities in the United States. J Appl Meteorol Climatol 47(3):805–818. https://doi.org/10.1175/2007jamc1611.1

Bempah SA, Øyhus AO (2017) The role of social perception in disaster risk reduction: beliefs, perception, and attitudes regarding flood disasters in communities along the Volta River, Ghana. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct 23:104–108