Paraphrasing vs. Summarizing (Differences, Examples, How To)

It can be confusing to know when to paraphrase and when to summarize. Many people use the terms interchangeably even though the two have different meanings and uses.

Today, let’s understand the basic differences between paraphrasing vs. summarizing and when to use which . We’ll also look at types and examples of paraphrasing and summarizing, as well as how to do both effectively.

Let’s look at paraphrasing first.

What is paraphrasing?

It refers to rewriting someone else’s ideas in your own words.

It’s important to rewrite the whole idea in your words rather than just replacing a few words with their synonyms. That way, you present an idea in a way that your audience will understand easily and also avoid plagiarism.

It’s also important to cite your sources when paraphrasing so that the original author of the work gets due credit.

When should you paraphrase?

The main purpose of paraphrasing is often to clarify an existing passage. You should use paraphrasing when you want to show that you understand the concept, like while writing an essay about a specific topic.

You may also use it when you’re quoting someone but can’t remember their exact words.

Finally, paraphrasing is a very effective way to rewrite outdated content in a way that’s relevant to your current audience.

How to paraphrase effectively

Follow these steps to paraphrase any piece of text effectively:

- Read the full text and ensure that you understand it completely. It helps to look up words you don’t fully understand in an online or offline dictionary.

- Once you understand the text, rewrite it in your own words. Remember to rewrite it instead of just substituting words with their synonyms.

- Edit the text to ensure it’s easy to understand for your audience.

- Mix in your own insights while rewriting the text to make it more relevant.

- Run the text through a plagiarism checker to ensure that it does not have any of the original content.

Example of paraphrasing

Here’s an example of paraphrasing:

- Original: The national park is full of trees, water bodies, and various species of flora and fauna.

- Paraphrased: Many animal species thrive in the verdant national park that is served by lakes and rivers flowing through it.

What is summarizing?

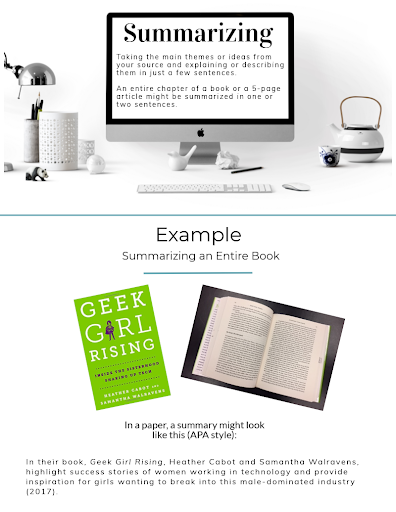

Summarizing is also based on someone else’s text but rather than presenting their ideas in your words, you only sum up their main ideas in a smaller piece of text.

It’s important to not use their exact words or phrases when summarizing to avoid plagiarism. It’s best to make your own notes while reading through the text and writing a summary based on your notes.

You must only summarize the most important ideas from a piece of text as summaries are essentially very short compared to the original work. And just like paraphrasing, you should cite the original text as a reference.

When should you summarize?

The main purpose of summarizing is to reduce a passage or other text to fewer words while ensuring that everything important is covered.

Summaries are useful when you want to cut to the chase and lay down the most important points from a piece of text or convey the entire message in fewer words. You should summarize when you have to write a short essay about a larger piece of text, such as writing a book review.

You can also summarize when you want to provide background information about something without taking up too much space.

How to summarize effectively

Follow these steps to summarize any prose effectively:

- Read the text to fully understand it. It helps to read it a few times instead of just going through it once.

- Pay attention to the larger theme of the text rather than trying to rewrite it sentence for sentence.

- Understand how all the main ideas are linked and piece them together to form an overview.

- Remove all the information that’s not crucial to the main ideas or theme. Remember, summaries must only include the most essential points and information.

- Edit your overview to ensure that the information is organized logically and follows the correct chronology where applicable.

- Review and edit the summary again to make it clearer, ensure that it’s accurate, and make it even more concise where you can.

- Ensure that you cite the original text.

Example of summarization

You can summarize any text into a shorter version. For example, this entire article can be summarized in just a few sentences as follows:

- Summary: The article discusses paraphrasing vs. summarizing by explaining the two concepts. It specifies when you should use paraphrasing and when you should summarize a piece of text and describes the process of each. It ends with examples of both paraphrasing and summarizing to provide a better understanding to the reader.

Paraphrasing vs. summarizing has been a long-standing point of confusion for writers of all levels, whether you’re writing a college essay or reviewing a research paper or book. The above tips and examples can help you identify when to use paraphrasing or summarizing and how to go about them effectively.

Inside this article

Fact checked: Content is rigorously reviewed by a team of qualified and experienced fact checkers. Fact checkers review articles for factual accuracy, relevance, and timeliness. Learn more.

About the author

Dalia Y.: Dalia is an English Major and linguistics expert with an additional degree in Psychology. Dalia has featured articles on Forbes, Inc, Fast Company, Grammarly, and many more. She covers English, ESL, and all things grammar on GrammarBrain.

Core lessons

- Abstract Noun

- Accusative Case

- Active Sentence

- Alliteration

- Adjective Clause

- Adjective Phrase

- Adverbial Clause

- Appositive Phrase

- Body Paragraph

- Compound Adjective

- Complex Sentence

- Compound Words

- Compound Predicate

- Common Noun

- Comparative Adjective

- Comparative and Superlative

- Compound Noun

- Compound Subject

- Compound Sentence

- Copular Verb

- Collective Noun

- Colloquialism

- Conciseness

- Conditional

- Concrete Noun

- Conjunction

- Conjugation

- Conditional Sentence

- Comma Splice

- Correlative Conjunction

- Coordinating Conjunction

- Coordinate Adjective

- Cumulative Adjective

- Dative Case

- Declarative Statement

- Direct Object Pronoun

- Direct Object

- Dangling Modifier

- Demonstrative Pronoun

- Demonstrative Adjective

- Direct Characterization

- Definite Article

- Doublespeak

- Equivocation Fallacy

- Future Perfect Progressive

- Future Simple

- Future Perfect Continuous

- Future Perfect

- First Conditional

- Gerund Phrase

- Genitive Case

- Helping Verb

- Irregular Adjective

- Irregular Verb

- Imperative Sentence

- Indefinite Article

- Intransitive Verb

- Introductory Phrase

- Indefinite Pronoun

- Indirect Characterization

- Interrogative Sentence

- Intensive Pronoun

- Inanimate Object

- Indefinite Tense

- Infinitive Phrase

- Interjection

- Intensifier

- Indicative Mood

- Juxtaposition

- Linking Verb

- Misplaced Modifier

- Nominative Case

- Noun Adjective

- Object Pronoun

- Object Complement

- Order of Adjectives

- Parallelism

- Prepositional Phrase

- Past Simple Tense

- Past Continuous Tense

- Past Perfect Tense

- Past Progressive Tense

- Present Simple Tense

- Present Perfect Tense

- Personal Pronoun

- Personification

- Persuasive Writing

- Parallel Structure

- Phrasal Verb

- Predicate Adjective

- Predicate Nominative

- Phonetic Language

- Plural Noun

- Punctuation

- Punctuation Marks

- Preposition

- Preposition of Place

- Parts of Speech

- Possessive Adjective

- Possessive Determiner

- Possessive Case

- Possessive Noun

- Proper Adjective

- Proper Noun

- Present Participle

- Quotation Marks

- Relative Pronoun

- Reflexive Pronoun

- Reciprocal Pronoun

- Subordinating Conjunction

- Simple Future Tense

- Stative Verb

- Subjunctive

- Subject Complement

- Subject of a Sentence

- Sentence Variety

- Second Conditional

- Superlative Adjective

- Slash Symbol

- Topic Sentence

- Types of Nouns

- Types of Sentences

- Uncountable Noun

- Vowels and Consonants

Popular lessons

Stay awhile. Your weekly dose of grammar and English fun.

The world's best online resource for learning English. Understand words, phrases, slang terms, and all other variations of the English language.

- Abbreviations

- Editorial Policy

- Key Differences

Know the Differences & Comparisons

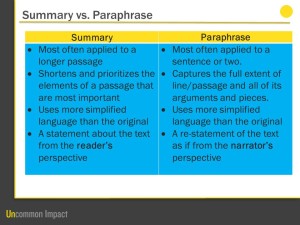

Difference Between Summary and Paraphrase

On the other hand, paraphrase means the restatement of the passage, in explicit language, so as to clarify its hidden meaning, without condensing it. In paraphrasing, the written material, idea or statement of some other person is presented in your own words, which is easy to understand.

These two are used in an excerpt to include the ideas of other author’s but without the use of quotations. Let us talk about the difference between summary and paraphrase.

Content: Summary Vs Paraphrase

Comparison chart, definition of summary.

A summary is an abridged form of a passage, which incorporates all the main or say relevant points of the original text while keeping the meaning and essence intact. It is used to give an overview of the excerpt in brief, to the reader. In summary, the author’s ideas are presented in your own words and sentences, in a succinct manner.

A summary encapsulates the gist and the entire concept of the author’s material in a shorter fashion. It also indicates the source of the information, using citation. Basically the length of the summary depends on the material being condensed.

It encompasses the main idea of every paragraph and the facts supporting that idea. It does not end with a conclusion, however, if there is a message in the conclusion, it is included in the summary. It also uses the keywords from the original material, but it does not use the same phrases or sentences.

Summaries save a lot of time of the reader, as the reader need not go through the entire work to filter the most important information contained in it, rather the reader gets the most relevant information in hand.

Definition of Paraphrase

Paraphrasing is not a reproduction of a similar copy of another author’s work, rather it means to rewrite the excerpt in your own language, using comprehensible words and restructuring the sentences, but without changing the context. Hence, in paraphrasing, the original idea and meaning of the text are maintained, but the sentence structure and the words used to deliver the message would be different.

The paraphrased version of the text is simple and easily understandable. The length is almost similar to the original text, as it only translates the original text into simplest form. It is not about the conversion of the text in a detailed manner, rather it is presented in such a way that goes well with your expression.

In paraphrasing, someone else’s written material is restated or rephrased in your own language, containing the same degree of detail. It is the retelling of the concept, using a different tone to address a different audience.

Key Differences Between Summary and Paraphrase

The points discussed below, explains the difference between summary and paraphrase

- To summarize means to put down the main ideas of the essential points of the excerpt, in your own words, while keeping its essence intact. On the contrary, to paraphrase means to decode the original text in your own words without distorting its meaning or essence.

- A summary is all about emphasizing the central idea (essence) and the main points of the text. In contrast, paraphrasing is done to simplify and clarify the meaning of the given excerpt, so as to enhance its comprehension.

- If we talk about the length of the summary in comparison to the original text, it is shorter, because summary tends to highlight the main points only and excludes the irrelevant material of the text. As against, in case of paraphrasing, the length is almost equal to the original text, because its aim is to decipher, i.e. to convert the complex text in a language which is easily understandable without excluding any material from the text.

- The main objective of summarizing is to compile and present the gist of the author’s idea or concept in a few sentences or points. Conversely, the primary objective of paraphrasing is to clarify the meaning of author’s work in a clear and effective manner when the words used by him/her are not important or the words are too complex to understand.

- A summary is used when you want to give a quick overview of the main ideas to the reader about the topic. On the contrary, Paraphrase is used when the idea or main point is more significant than the actual words used in the material and also when you want to use your own voice to explain the concept or idea.

- A summary does not include lengthy explanations, examples and what the reader has understood. In contrast, a paraphrase does not include the exact same wordings or paragraphs used in the original source, so as to avoid plagiarism.

Steps for Summarizing

- First of all, you need to read the entire passage twice or thrice to grasp the meaning and essence of the material.

- Identify and underline all the important points, ideas and supporting facts which you have read.

- Now, explain the material to yourself, for better understanding.

- Rewrite in your own words, the salient points and central idea from the original text, in a few sentences.

- Omit unnecessary detailing and examples.

- Make a comparison of the original text and the summary which you’ve created.

Steps for Paraphrasing

- Read the entire text carefully, twice or thrice, to absorb the meaning and essence.

- Rewrite the author’s ideas in a unique language, i.e. in your own voice. Make sure that the sentences and words used are your own and it should not be a mere substitution or swapping of words and phrases.

- Further, the sequence in which idea is presented, need not be different from the original source.

- Compare the paraphrased version with the main text, and ensure that the essence clearly presented, as well as make sure that it is free from plagiarism.

- Check that the words and phrases which are directly taken from the text are within quotation marks.

- Provide references.

In a nutshell, a summary is nothing but a shorter version of an excerpt or passage. On the contrary, a paraphrase is the restatement of the original text or excerpt. One can use any of the two sources, as per the requirement, when the idea of any of the sources is relevant to your material, but the wording is not that important.

You Might Also Like:

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Enroll & Pay

- Prospective Students

- Current Students

- Degree Programs

Paraphrase and Summary

Paraphrase and summary are different writing strategies that ask you to put another author’s argument in your own words. This can help you better understand what the writer of the source is saying, so that you can communicate that message to your own reader without relying only on direct quotes. Paraphrases are used for short passages and specific claims in an argument, while summaries are used for entire pieces and focus on capturing the big picture of an argument. Both should be cited using the appropriate format (MLA, APA, etc.). See KU Writing Center guides on APA Formatting , Chicago Formatting , and MLA Formatting for more information.

When you paraphrase, you are using your own words to explain one of the claims of your source's argument, following its line of reasoning and its sequence of ideas. The purpose of a paraphrase is to convey the meaning of the original message and, in doing so, to prove that you understand the passage well enough to restate it. The paraphrase should give the reader an accurate understanding of the author's position on the topic. Your job is to uncover and explain all the facts and arguments involved in your subject. A paraphrase tends to be about the same length or a little shorter than the thing being paraphrased.

To paraphrase:

- Alter the wording of the passage without changing its meaning. Key words, such as names and field terminology, may stay the same (i.e. you do not need to rename Milwaukee or osteoporosis), but all other words must be rephrased.

- Retain the basic logic of the argument, sequence of ideas, and examples used in the passage.

- Accurately convey the author's meaning and opinion.

- Keep the length approximately the same as the original passage.

- Do not forget to cite where the information came from. Even though it is in your own words, the idea belongs to someone else, and that source must be acknowledged.

A summary covers the main points of the writer’s argument in your own words. Summaries are generally much shorter than the original source, since they do not contain any specific examples or pieces of evidence. The goal of a summary is to give the reader a clear idea of what the source is arguing, without going into any specifics about what they are using to argue their point.

To summarize:

- Identify what reading or speech is being summarized.

- State the author’s thesis and main claims of their argument in your own words. Just like paraphrasing, make sure everything but key terms is reworded.

- Avoid specific details or examples.

- Avoid your personal opinions about the topic.

- Include the conclusion of the original material.

- Cite summarized information as well.

In both the paraphrase and summary, the author's meaning and opinion are retained. However, in the case of the summary, examples and illustrations are omitted. Summaries can be tremendously helpful because they can be used to encapsulate everything from a long narrative passage of an essay, to a chapter in a book, to an entire book.

When to Use Paraphrasing vs. Summarizing

Updated June 2022

Module 11: The Research Process—Using and Citing Sources

Paraphrasing, learning objective.

- Describe when and how to paraphrase

There are two ways of integrating source material into your writing other than directly quoting from it: paraphrase and summary.

Paraphrasing and summarizing are similar. When we paraphrase, we process information or ideas from another person’s text and put it in our own words. The main difference between paraphrase and summary is scope : if summarizing means rewording and condensing, then paraphrasing means rewording without drastically altering length. However, paraphrasing is also generally more faithful to the spirit of the original; whereas a summary requires you to process and invites your own perspective, a paraphrase ought to mirror back the original idea using your own language.

What is Paraphrasing?

In a paraphrase, you use your own words to explain the specific points another writer has made. If the original text refers to an idea or term discussed earlier in the text, your paraphrase may also need to explain or define that idea. You may also need to interpret specific terms made by the writer in the original text.

Be careful not to add information or commentary that isn’t part of the original passage in the midst of your paraphrase. You don’t want to add to or take away from the meaning of the passage you are paraphrasing. Save your comments and analysis until after you have finished your paraphrase.

And be careful to remember that your paraphrase still requires a citation. Even when you use someone else’s ideas but put those ideas into your own words, you still need to acknowledge the source of those ideas!

What Does Good Paraphrasing Look Like?

In our first example, the writer is using MLA style to write a research essay for a literature class. Let’s compare two examples.

- Example 1: While Gatsby is deeply in love with Daisy in The Great Gatsby , his love for her is indistinguishable from his love of his possessions (Callahan).

- Example 2: John F. Callahan suggests in his article “F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Evolving American Dream” that while Gatsby is deeply in love with Daisy in The Great Gatsby , his love for her is indistinguishable from his love of his possessions (381).

In example 1, it’s hard to tell what exactly is being paraphrased. Is the entire source about the comparison between Gatsby’s love for Daisy and his love for his possessions? And, if this is the first or only reference to this particular piece of evidence in the research essay, the writer should include more information and signal phrasing about the source of this paraphrase in order to properly introduce it.

In example 2, the writer incorporates the names of the author and the title of the source material, so the credibility of the source material is now clear to the reader. Furthermore, because there is a page number at the end of this sentence, the reader understands that this passage is a paraphrase of a particular part of Callahan’s essay and not a summary of the entire essay.

Here’s another example, from an essay in APA style for a criminal justice class.

- Example 1: Computer criminals have lots of ways to get away with credit card fraud (Cameron, 2002).

- Example 2: Cameron (2002) points out that computer criminals intent on committing credit card fraud are able to take advantage of the fact that there aren’t enough officials working to enforce computer crimes. Criminals are also able to use technology to their advantage by communicating via email and chat rooms with other criminals.

In example 1, the main problem with this paraphrase is that it’s so vague and general that is doesn’t adequately explain to the reader what the point of the evidence really is or why that evidence matters. Remember: your readers have no way of automatically knowing why you as a research writer think that a particular piece of evidence is useful in supporting your point. This is why it is key that you introduce and explain your evidence.

Figure 1 . Paraphrasing sources can sometimes be a tricky skill to develop, and often requires creative thinking. Use the practice examples below to fine-tune your paraphrasing skills.

In example 2, the writer includes additional information that introduces and explains the point of the evidence. In this particular example, the author’s name is also incorporated into the explanation of the evidence as well. In APA, it is preferable to weave in the author’s name into your essay, usually at the beginning of a sentence. However, it would also have been acceptable to end the paraphrase with just the author’s last name and the date of publication in parentheses.

What are the benefits of paraphrasing? It contextualizes the information (who said it, when, and where). It restates all the key points used by the source. Most importantly, it allows t he writer to maintain a strong voice while sharing important information from the source.

Paraphrasing is likely the most common way you will integrate your source information. Quoting should be minimal in most research papers.

Just remember, changing a few words here and there doesn’t count as a paraphrase. Students sometimes attempt to paraphrase by just changing a few words in the source material. The key is to understand the material put it into your own original words, but without changing the ideas. It’s tricky, but practice makes perfect!

Paraphrasing is a skill that takes time to develop. One way of becoming familiar with paraphrasing is by examining successful and unsuccessful attempts at paraphrasing. Read the quote below from page 179 of Howard Gardner’s book titled Multiple Intelligences and then examine the attempt at paraphrasing that follows.

“America today has veered too far in the direction of formal testing without adequate consideration of the costs and limitations of an exclusive emphasis on that approach.” [1]

A critical component of successful paraphrasing includes citing your original source. The citation may be made as an in-text citation, a footnote, or an endnote, but it must be included. You want to make clear and get credit for engaging with other thinkers in your work, and a correct citation foregrounds that strength. Failure to cite your sources is a violation of intellectual integrity (plagiarism), or taking someone else’s words or ideas and presenting them as your own. Sources should be always be cited in the appropriate way. Consider the following examples.

- According to Levy (1997), the tutor-tool framework is useful.

- According to Levy, the tutor-tool framework is useful.

- Michael Levy, Computer-Assisted Language Learning: Context and Conceptualization (New York: Oxford), 178.

Take a look at the following paraphrased passages and determine if it is plagiarized or not plagiarized.

- Gardner, Howard. Multiple Intelligences: New Horizons in Theory and Practice. BasicBooks, 2006 ↵

- OWL at Excelsior College: Paraphrasing. Provided by : Excelsior College . Located at : https://owl.excelsior.edu/research/drafting-and-integrating/drafting-and-integrating-paraphrasing/ . Project : OWL at Excelsior College. License : CC BY: Attribution

- Paraphrase Activity. Authored by : Excelsior OWL. Located at : https://owl.excelsior.edu/research/drafting-and-integrating/drafting-and-integrating-paraphrasing-activity/ . License : CC BY: Attribution

- Avoiding Plagiarism Activity. Provided by : Excelsior OWL. Located at : https://owl.excelsior.edu/plagiarism/plagiarism-how-to-avoid-it/plagiarism-paraphrasing/plagiarism-paraphrasing-try-it-out/ . License : CC BY: Attribution

- Image of writing in chalk. Authored by : Kaboompics. Provided by : Pexels. Located at : https://www.pexels.com/photo/think-outside-of-the-box-6375/ . License : Other . License Terms : https://www.pexels.com/photo-license/

- Quoting examples from Paraphrasing in MLA Style. Authored by : Steven D. Krause. Located at : http://www.stevendkrause.com/tprw/chapter3.html . License : CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- The Word on College Reading and Writing. Authored by : Carol Burnell, Jaime Wood, Monique Babin, Susan Pesznecker, and Nicole Rosevear. Located at : https://openoregon.pressbooks.pub/wrd/chapter/summarizing-a-text/ . License : CC BY-NC: Attribution-NonCommercial

Microsoft 365 Life Hacks > Writing > The Difference Between Summarizing & Paraphrasing

The Difference Between Summarizing & Paraphrasing

Summarizing and paraphrasing are helpful ways to include source material in your work without piling on direct quotes. Understand the differences between these approaches and when to use each.

Summarizing vs. Paraphrasing: The Biggest Differences

Though summarizing and paraphrasing are both tools for conveying information clearly and concisely, they help you achieve this in different ways. In general, the difference is rooted in the scale of the source material: To share an entire source at once, you summarize; to share a specific portion of a source (without quoting directly, of course), you paraphrase.

Write with Confidence using Editor

Elevate your writing with real-time, intelligent assistance

What is Summarizing?

Summarizing is simplifying the content of a source to its main points in your own words. You literally sum up something, distill it down to its most essential parts. Summaries cover whole sources rather than a piece or pieces of a source and don’t include direct quotes or extraneous detail.

How to Summarize

- Understand the original thoroughly. You may start by scanning the original material, paying close attention to headers and any in-text summaries, but once you’re sure that this source is something you’re going to use in your research paper , review it more thoroughly to gain appropriate understanding and comprehension.

- Take notes of the main points. A bulleted list is appropriate here-note the main idea of each portion of the source material. Take note of key words or phrases around which you can build your summary list and deepen your understanding.

- Build your summary. Don’t just use the list you’ve already created—this was a first draft . Craft complete sentences and logical progression from item to item. Double check the source material to ensure you’ve not left out any relevant points and trim anything extraneous. You can use a bulleted or numbered list here or write your summary as a paragraph if that’s more appropriate for your use. Make sure to follow the rules of parallelism if you choose to stay in list form.

What is Paraphrasing?

Paraphrasing is rephrasing something in your own words; the word comes from the Greek para -, meaning “beside” or “closely resembling”, 1 combined with “phrase,” which we know can mean a string of words or sentences. 2 Paraphrasing isn’t practical for entire sources—just for when you want to highlight a portion of a source.

How to Paraphrase

- Read actively . Take notes, highlight or underline passages, or both if you please-whatever makes it easiest for you to organize the sections of the source you want to include in your work.

- Rewrite and revise. For each area you’d like to paraphrase, take the time to rewrite it in your own words. Retain the meaning of the original text, but don’t copy it too closely; take advantage of a thesaurus to ensure you’re not relying too heavily on the source material.

- Check your work and revise again as needed . Did you retain the meaning of the source material? Did you simplify the language of the source material? Did you differentiate your version enough? If not, try again.

Summarizing and paraphrasing are often used in tandem; you’ll likely find it appropriate to summarize an entire source and then paraphrase specific portions to support your summary. Using either approach for including sources requires appropriate citing, though, so ensure that you follow the correct style guide for your project and cite correctly.

Get started with Microsoft 365

It’s the Office you know, plus the tools to help you work better together, so you can get more done—anytime, anywhere.

Topics in this article

More articles like this one.

What is independent publishing?

Avoid the hassle of shopping your book around to publishing houses. Publish your book independently and understand the benefits it provides for your as an author.

What are literary tropes?

Engage your audience with literary tropes. Learn about different types of literary tropes, like metaphors and oxymorons, to elevate your writing.

What are genre tropes?

Your favorite genres are filled with unifying tropes that can define them or are meant to be subverted.

What is literary fiction?

Define literary fiction and learn what sets it apart from genre fiction.

Everything you need to achieve more in less time

Get powerful productivity and security apps with Microsoft 365

Explore Other Categories

What is the difference between paraphrasing & summarizing

Differences between paraphrasing & summarizing, definition and purpose.

Paraphrasing involves rewriting someone else's ideas or a specific text in your own words while maintaining the original meaning and often keeping a similar length to the source material. The primary purpose of paraphrasing is to use another person's ideas in your work without resorting to a direct quotation, thereby showing your understanding of the source while integrating it smoothly into your own narrative.

Summarizing , on the other hand, is the process of distilling a longer piece of text down to its essential points, significantly reducing its length. The goal of summarizing is to provide a broad overview of the source material, capturing only the main ideas in a concise manner, which helps in clarifying the overall theme or argument of the text for the reader.

Detail and Length

The level of detail and the length of the text are key differences between paraphrasing and summarizing. Paraphrasing retains a level of detail similar to the original text, and the paraphrased passage is typically about the same length or slightly shorter than the source. This approach is suitable when specific details or points from the source are necessary to understand the reader in the context of your work.

In contrast, summarizing significantly reduces the length of the original text, focusing only on the central themes or main ideas. This makes summaries particularly useful for giving an overview of long texts, such as books, articles, or comprehensive reports, where only the core message is needed.

Usage in Academic Writing

Both paraphrasing and summarizing are crucial skills in academic writing. They help one effectively incorporate the ideas of others into one's work. Paraphrasing is often preferred when specific evidence or a detailed understanding of the source is required to support one's argument without overusing direct quotes, which can clutter the text and disrupt the flow of the narrative.

Summarizing is a time-saving and efficient strategy when referring to broader concepts or discussing a source's general scope. It's particularly useful during literature reviews or when providing background information where detailed support is unnecessary. Allowing you to succinctly conveys the essence of a sourcerelieves you from overwhelming your readers with unnecessary details while still ensuring they grasp the relevance of the referenced works.

In summary, choosing between paraphrasing and summarizing depends mainly on the writer's intent, the importance of the details in the source material, and how they wish to integrate this information into their own writing.

How to paraphrase in a few steps

Paraphrasing refers to rewriting content in our own words while keeping the original meaning. Here are some steps and tips for effective paraphrasing:

Reading & Understanding the content

Ensure you fully understand the meaning of the text while identifying the essential concepts.

Taking Notes

Write the main ideas without looking at the original text.

Using Synonyms

This step involves replacing words with relevant synonyms; keeping some technical words that can't be replaced is essential.

Changing Sentence Structure

Alter the sentence structure, such as changing active to passive voice or shortening long sentences.

Rephrasing Concepts

Explain the concepts differently, using your own words and style.

Comparing with the original content

Ensure your paraphrased version accurately reflects the original meaning and is not too similar.

Cite the Source

It's essential to credit the source even when paraphrased.

- The original text:

Students frequently overuse direct quotations in taking notes, and as a result, they overuse quotations in the final [research] paper. Probably only about 10% of your final manuscript should appear as a directly quoted matter. Therefore, you should strive to limit the exact transcribing of source materials while taking notes. Lester, James D. Writing Research Papers. 2nd ed., 1976, pp. 46-47.

- The paraphrased text:

In research papers, students often quote excessively, failing to keep quoted material down to a desirable level. Since the problem usually originates during note-taking, it is essential to minimize the material recorded verbatim (Lester 46-47).

Here are some tips to paraphrase:

- Avoid Plagiarism: Don’t copy the text verbatim without quotation marks and proper attribution.

- Maintain Original Meaning: Ensure the paraphrased text conveys the same message as the original.

- Use a Different Structure: Change the information order and rephrase sentences.

- Simplify the Language: Use more straightforward language to make the text more understandable, if appropriate.

Common paraphrasing mistakes

- Not changing enough to avoid plagiarism

One of the most complex parts of paraphrasing a sentence is changing enough to avoid copying and not lose the original meaning. This can be a tricky balancing act, especially if you have to keep some of the wording.

- Distorting the meaning

Likewise, changing the words and sentence structure can accidentally change the meaning. That’s fine if you want to write an original sentence, but if you’re trying to convey someone else’s idea, it's best to rewrite and adequately describe it.

Review your paraphrase to confirm that all the words are correctly used and placed in the correct order for your intended meaning. If unsure, you can ask someone to read the passage to see how they interpret it.

- Forgetting the citation

Some people think that if you put an idea into your own words, you don’t need to cite where it came from—but that’s not true. Even if the wording is your own, the ideas are not. That means you need a citation.

If you have many paraphrased sentences from the exact location in a source, you need only one citation at the end of the passage. Otherwise, you need a citation for each paraphrased sentence from another source in your writing, without exception.

How to summarize in a few steps

Focusing on the main ideas.

Read through the entire piece you want to summarize and identify the most important concepts and themes. Ignore minor details and examples. Focus on capturing the essence of the critical ideas.

If it's an article or book, read introductions, headings, and conclusions to understand the central themes. As you read, ask yourself, "What is the author trying to convey here?" to determine what's most significant.

Keeping it short and straightforward

A summary should be considerably shorter than the original work. Aim for about 1/3 of the length or less. Be concise by eliminating unnecessary words and rephrasing ideas efficiently. Use sentence fragments and bulleted lists when possible.

Maintaining objectivity

Summarize the work factually without putting your own personal spin or opinions on the information. Report the key ideas in an impartial, balanced manner. Do not make judgments about the quality or accuracy of the content.

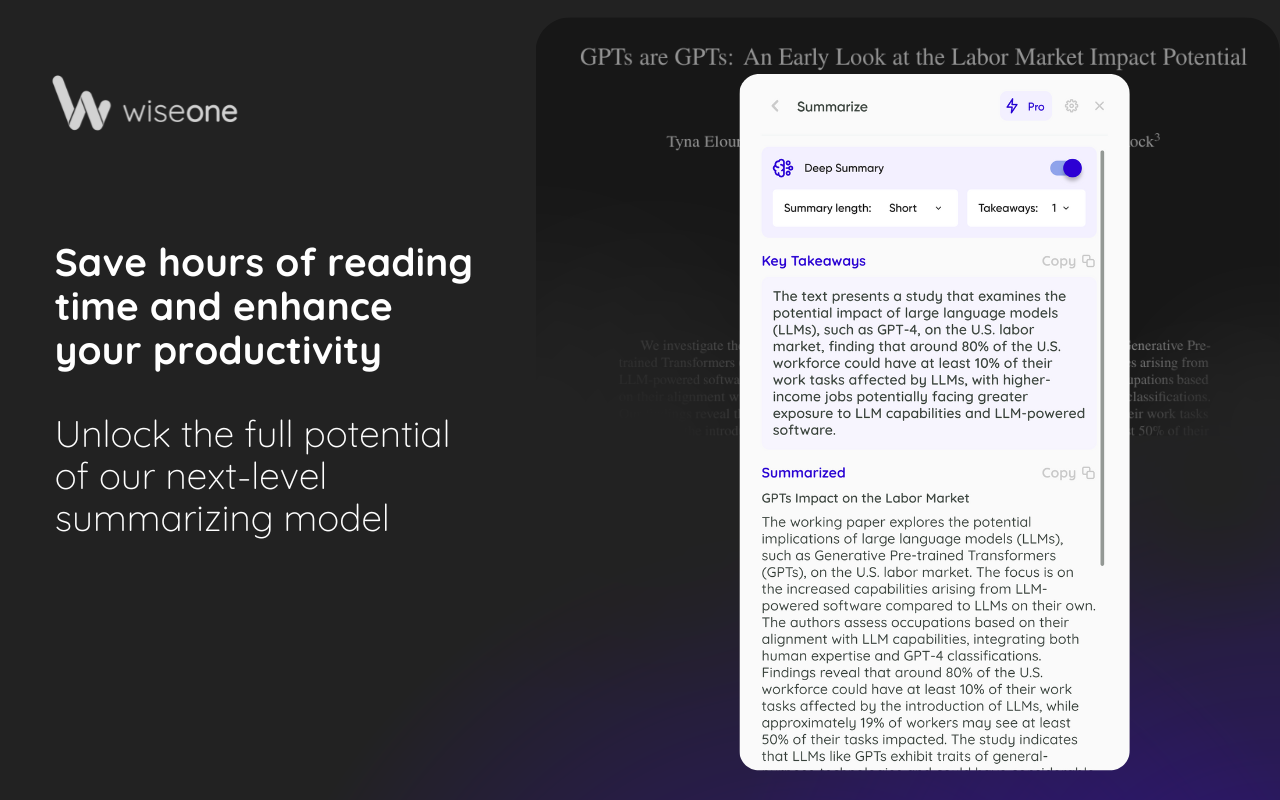

Using a summarizing tool

As AI continues gaining popularity, leveraging dedicated to benefit from their advantage is essential.

Among these tools lies Wiseone , an innovative AI tool that transforms how we read and search for information online.

Wiseone's "Summarize" feature allows you to understand the main points of an article or a PDF document efficiently without the need to read the entire piece by generating thorough summaries with key takeaways.

Don’ts of paragraph summarization

Similarly, keep these in mind as things to avoid:

- Plagiarizing the original paragraph. It’s perfectly fine to include direct quotes, but if you do, cite them properly. However, most of the summary should be in your own words.

- Paraphrasing rather than summarizing. Here’s a way to think of the difference: a summary is a “highlight reel,” and paraphrasing condenses the entire paragraph.

- Omitting key information. When summarizing a paragraph, you might need to mention information from its preceding or following paragraphs, or even other sections from the original work, to give the reader appropriate context for the other information included in the summary.

What is paraphrasing?

What is summarizing.

Summarizing is the process of distilling a longer text down to its essential points, significantly reducing its length. The goal of summarizing is to provide a broad overview of the source material, capturing only the main ideas in a concise manner, which helps in clarifying the overall theme or argument of the text for the reader.

What are the steps to paraphrase?

- Reading & Understanding the content: Ensure you fully understand the meaning of the text while identifying the essential concepts.

- Taking Notes: Write the main ideas without looking at the original text.

- Using Synonyms: This step involves replacing words with relevant synonyms; keeping some technical words that can't be replaced is essential.

- Changing Sentence Structure: Alter the sentence structure, such as changing active to passive voice or shortening long sentences.

- Rephrasing Concepts: Explain the concepts differently, using your own words and style.

- Comparing with the original content: Ensure your paraphrased version accurately reflects the original meaning and is not too similar.

- Cite the Source: It's essential to credit the source even when paraphrased.

What are some tips to paraphrase?

What are the common paraphrasing mistakes.

- Not changing enough to avoid plagiarism: One of the most complex parts of paraphrasing a sentence is changing enough to avoid copying and not lose the original meaning. This can be a tricky balancing act, especially if you have to keep some of the wording.

- Distorting the meaning: Changing the words and sentence structure can accidentally change the meaning. That’s fine if you want to write an original sentence, but if you’re trying to convey someone else’s idea, it's best to rewrite and adequately describe it. Review your paraphrase to confirm that all the words are correctly used and placed in the correct order for your intended meaning. If unsure, you can ask someone to read the passage to see how they interpret it.

- Forgetting the citation: Some people think that if you put an idea into your own words, you don’t need to cite where it came from—but that’s not true. Even if the wording is your own, the ideas are not. That means you need a citation.

What are the steps to summarize content?

- Focusing on the main ideas : Read through the entire piece you want to summarize and identify the most important concepts and themes. Ignore minor details and examples. Focus on capturing the essence of the critical ideas. If it's an article or book, read introductions, headings, and conclusions to understand the central themes. As you read, ask yourself, "What is the author trying to convey here?" to determine what's most significant.

- Keeping it short and straightforward: A summary should be shorter than the original work. Aim for about 1/3 of the length or less. Be concise by eliminating unnecessary words and rephrasing ideas efficiently. Use sentence fragments and bulleted lists when possible.

- Maintaining objectivity: Summarize the work factually without putting your own personal spin or opinions on the information. Report the key ideas in an impartial, balanced manner. Do not make judgments about the quality or accuracy of the content.

Enhance your web search, Boost your reading productivity with Wiseone

The Sheridan Libraries

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Sheridan Libraries

Paraphrasing & Summarizing

- What is Plagiarism?

- School Plagiarism Policies

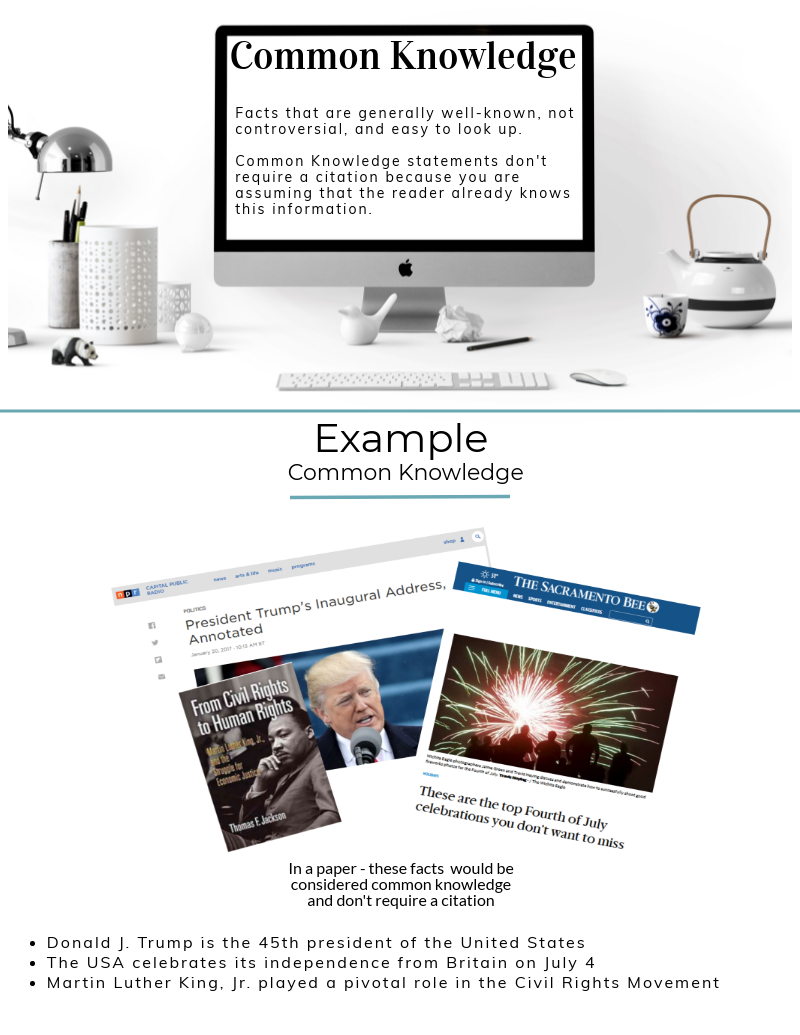

- Common Knowledge

- Minimizing Your Plagiarism Risk

- Student Help

- Helping Prevent Plagiarism in Your Classroom

- Avoiding Plagiarism Course

- Course FAQs

To help the flow of your writing, it is beneficial to not always quote but instead put the information in your own words. You can paraphrase or summarize the author’s words to better match your tone and desired length. Even if you write the ideas in your own words, it is important to cite them with in-text citations or footnotes (depending on your discipline’s citation style ).

Definitions

- Paraphrasing allows you to use your own words to restate an author's ideas.

- Summarizing allows you to create a succinct, concise statement of an author’s main points without copying and pasting a lot of text from the original source.

What’s the difference: Paraphrasing v. Summarizing

Explore the rest of the page to see how the same material could be quoted, paraphrased, or summarized. Depending on the length, tone, and argument of your work, you might choose one over the other.

- Bad Paraphrase

- Good Paraphrase

- Reread: Reread the original passage until you understand its full meaning.

- Write on your own: Set the original aside, and write your paraphrase on a note card.

- Connect: Jot down a few words below your paraphrase to remind you later how you envision using this material.

- Check: Check your rendition with the original to make sure that your version accurately expresses all the essential information in a new form.

- Quote: Use quotation marks to identify any unique term or phraseology you have borrowed exactly from the source.

- Cite: Record the source (including the page) on your note card or notes document so that you can credit it easily if you decide to incorporate the material into your paper.

Explore the tabs to see the difference between an acceptable and unacceptable paraphrase based on the original text in each example.

Original Text

“Business communication is increasingly taking place internationally – in all countries, among all peoples, and across all cultures. An awareness of other cultures – of their languages, customs, experiences and perceptions – as well as an awareness of the way in which other people conduct their business, are now essential ingredients of business communication” (Chase, O’Rourke & Wallace, 2003, p.59).

More and more business communication is taking place internationally—across all countries, peoples, and cultures. Awareness of other cultures and the way in which people do business are essential parts of business communication (Chase, O’Rourke & Wallace, 2003, p.59)

Compare the Original and Paraphrase

Too much of the original is quoted directly, with only a few words changed or omitted. The highlighted words are too similar to the original quote:

More and more business communication is taking place internationally —across all countries, peoples, and cultures . Awareness of other cultures and the way in which people do business are essential parts of business communication (Chase, O’Rourke & Wallace, 2003, p.59)

Original Text

“Business communication is increasingly taking place internationally – in all countries, among all peoples, and across all cultures. An awareness of other cultures – of their languages, customs, experiences and perceptions – as well as an awareness of the way in which other people conduct their business, are now essential ingredients of business communication” (Chase, O’Rourke & Wallace, 2003, p.59).

The importance of understanding the traditions, language, perceptions, and the manner in which people of other cultures conduct their business should not be underestimated, and it is a crucial component of business communication (Chase, O’Rourke & Wallace, 2003, p. 59).

The original’s ideas are summarized and expressed in the writer’s own words with minimal overlap with the original text's language:

The importance of understanding the traditions, language, perceptions, and the manner in which people of other cultures conduct their business should not be underestimated, and it is a crucial component of business communication (Chase, O’Rourke & Wallace, 2003, p. 59).

- Bad Summary

- Good Summary

- Find the main idea: Ask yourself, “What is the main idea that the author is communicating?”

- Avoid copying: Set the original aside, and write one or two sentences with the main point of the original on a note card or in a notes document.

- Connect: Jot down a few words below your summary to remind you later how you envision using this material.

Business communication is worldwide, and it is essential to build awareness of other cultures and the way in which other people conduct their business. (Chase, O’Rourke & Wallace, 2003, p.59).

Compare the Original and Summary

Too much of the original is quoted directly, with only a few words changed or omitted. The highlighted words are too similar to the original text:

Business communication is worldwide, and it is essential to build awareness of other cultures and the way in which other people conduct their business . (Chase, O’Rourke & Wallace, 2003, p.59).

In a world that is increasingly connected, effective business communication requires us to learn about other cultures, languages, and business norms (Chase, O’Rourke & Wallace, 2003, p.59).

The original’s ideas are summarized and expressed in the writer’s own words with minimal overlap:

In a world that is increasingly connected, effective business communication requires us to learn about other cultures , languages , and business norms (Chase, O’Rourke & Wallace, 2003, p.59).

No matter what the source or style, you need to cite it both in-text and at the end of the paper with a full citation! Write down or record all the needed pieces of information when researching to ensure you avoid plagiarism.

Cheat Sheet

- Paraphrasing and Summarizing Download this helpful cheat sheet covering "Paraphrasing and Summarizing."

- << Previous: Quoting

- Next: Minimizing Your Plagiarism Risk >>

- Last Updated: Aug 7, 2023 2:00 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.jhu.edu/avoidingplagiarism

Writing Center FAQs

- Capella FAQs Home

- Capella FAQs

- Writing Center

Q: What is the difference between summarizing and paraphrasing?

- Career Center

- Disability Support

- Doctoral Support

- Learner Records

- Military Support

- Office of Research & Scholarship

- Quantitative Skills Center

- Scholarships & Grants

- Technical Support

- 13 APA Style

- 16 Composition

- 8 References

- 22 Resources

- 24 Writing Center

- 6 Writing Studio

You Search Writing Center FAQs

Search All FAQs

Answer Last Updated: May 22, 2017 Views: 411

Summarizing and paraphrasing are very similar. Both involve taking ideas, words, or phrases from a source and crafting them into new sentences within your writing.

Summarizing is when you briefly state the main concept/s of a topic in your own words.

Paraphrasing is when you briefly recount a specific passage from a piece in your own words.

Whether summarizing or paraphrasing, credit is always given to the author.

- Share on Facebook

Was this helpful? Yes 0 No 0

Still have questions? Email us. [email protected]

Related Topics

September 6

0 comments

Summarizing vs. Paraphrasing: What’s the Real Difference?

By Joshua Turner

September 6, 2023

Summarizing and paraphrasing are two essential skills in writing. They are often used interchangeably, but they have distinct differences. Summarizing is the process of condensing a text into a shorter version, highlighting the main points, and leaving out the details.

On the other hand, paraphrasing is rewording a text in your own words, retaining the original meaning and message.

Understanding summarizing involves identifying the key ideas and concepts in a text and presenting them in a concise and clear manner. It requires a good understanding of the text and the ability to distinguish between essential and non-essential information.

Summarizing is useful when you want to provide a brief overview of a longer text or when you want to highlight the main ideas.

Understanding paraphrasing involves rewording a text in a way that retains the original meaning but uses different words and sentence structures.

It requires a good understanding of the text and the ability to express the ideas in your own words. Paraphrasing is useful when you want to avoid plagiarism or when you want to clarify the meaning of a text.

Key Takeaways

- Summarizing involves condensing a text into a shorter version, highlighting the main points and leaving out the details.

- Paraphrasing involves rewording a text in a way that retains the original meaning but uses different words and sentence structures.

- Summarizing is useful when you want to provide a brief overview of a longer text, while paraphrasing is useful when you want to avoid plagiarism or clarify the meaning of a text.

Definition of Summarizing

Summarizing is the process of condensing a longer piece of text into a shorter, more concise version while retaining the main points and key concepts. It involves creating an overview of the text that captures the gist of the original content.

Purpose of Summaries

The purpose of summaries is to provide readers with a condensed version of a longer text that highlights the main points and key concepts. Summaries are useful for quickly understanding the content of a longer piece of writing, such as an article or book, without having to read the entire text.

Main Points in Summarizing

The main points in summarizing include identifying the key concepts and ideas in the original text, condensing the information into a shorter version, and ensuring that the summary accurately represents the main points of the original text.

Steps in Summarizing

The steps in summarizing include reading the original text carefully, identifying the main points and key concepts, condensing the information into a shorter version, and reviewing the summary to ensure that it accurately represents the main points of the original text. It is important to use your own words when creating a summary and to avoid copying phrases or sentences directly from the original text.

In summary, summarizing is the process of condensing a longer piece of text into a shorter, more concise version while retaining the main points and key concepts. It involves creating an overview of the text that captures the gist of the original content. The purpose of summaries is to provide readers with a condensed version of a longer text that highlights the main points and key concepts.

The steps in summarizing include reading the original text carefully, identifying the main points and key concepts, condensing the information into a shorter version, and reviewing the summary to ensure that it accurately represents the main points of the original text.

Understanding Paraphrasing

Paraphrasing is the act of rephrasing a text in your own words while maintaining the original meaning. It is an essential skill in academic writing , as it allows you to incorporate information from other sources while avoiding plagiarism. Paraphrasing involves interpreting the main ideas in the original text and presenting them in your own voice.

Purpose of Paraphrases

The purpose of paraphrasing is to present information from other sources in a way that is more accessible or relevant to your intended audience. It also allows you to integrate information from multiple sources into a cohesive argument. Paraphrasing can also help you to clarify complex ideas and concepts.

Main Ideas in Paraphrasing

The main ideas in paraphrasing are to understand the original text, interpret the main ideas, and rephrase them in your own words. It is important to maintain the original meaning and avoid changing the author’s intended message. Paraphrasing should also be done in your own voice to avoid plagiarism.

Steps in Paraphrasing

The steps in paraphrasing include reading and understanding the original text, identifying the main ideas, and rephrasing them in your own words. You should also check your paraphrase against the original text to ensure that you have maintained the original meaning. It is also important to cite the original source to avoid plagiarism.

Comparison of Summarizing and Paraphrasing

Summarizing and paraphrasing are two different techniques used to convey information from one source to another.

Length and Detail

Summarizing involves condensing a large amount of information into a concise version while maintaining the main points. On the other hand, paraphrasing involves rephrasing the text in your own words while retaining the original meaning. Summaries are shorter than the original text and omit details, while paraphrases are usually the same length as the original text and include more details.

Quoting and Citation

When summarizing, you don’t need to use direct quotes or citations because you are putting the information into your own words. However, when paraphrasing, you still need to give credit to the original source by using citations and quotation marks when necessary.

Structure and Concepts

Summarizing involves restructuring the original text to make it more concise, while paraphrasing involves rewording the original text. Summarizing focuses on the main points while paraphrasing focuses on the details.

When summarizing, you may need to rearrange the concepts to make them more understandable, while paraphrasing may require you to explain the concepts more clearly.

The audience and purpose of the text can influence whether summarizing or paraphrasing is appropriate. Summarizing is useful when the audience needs a quick overview of the main points, while paraphrasing is useful when the audience needs a more detailed understanding of the text. The purpose of the text can also determine whether summarizing or paraphrasing is appropriate. Summarizing is useful when the purpose is to provide a brief overview, while paraphrasing is useful when the purpose is to explain the details.

Avoiding Plagiarism

Using someone else’s work without proper credit is not only unethical, but it can also have serious consequences. By understanding plagiarism, citing your source material, and using a plagiarism checker, you can ensure that your work is original and free of plagiarism.

Understanding Plagiarism

Plagiarism is the act of using someone else’s work without giving them proper credit. It can be intentional or unintentional, and it can have serious consequences. To avoid plagiarism, understand what it is and how to avoid it.

Citing Source Material

Citing your source material is an essential part of avoiding plagiarism. When you use someone else’s work, you must give them credit by citing the original source. There are different citation styles, such as APA, MLA, and Chicago, so make sure to use the appropriate one for your work.

Using a Plagiarism Checker

Using a plagiarism checker is a great way to ensure that your work is original and free of plagiarism. There are many free and paid tools available online that can help you check your work for plagiarism. These tools compare your work to other sources on the internet and highlight any similarities.

In summary, while summarizing and paraphrasing are similar in that they both involve condensing or rewording information, there are some key differences between them. Summarizing involves reducing a text to its essential points, while paraphrasing involves restating the central idea in your own words.

Accuracy is crucial in both cases, but it is especially important when paraphrasing since it involves conveying information in a new way. Paraphrasing is useful when you want to highlight specific insights or takeaways from a text while summarizing is better suited for providing an overview of the essential information.

When deciding whether to summarize or paraphrase, it’s important to consider the function of the text and the audience you are writing for. Summarizing is useful when you want to provide a quick overview of a text’s most relevant information, while paraphrasing is better suited for conveying the central idea in a new way.

Overall, whether you choose to summarize or paraphrase, the goal is to convey relevant information in a clear and concise manner that helps the reader gain insights and takeaways from the text.

Frequently Asked Questions

Here are some common questions about this topic.

What are some examples of paraphrasing and summarizing, and how do they differ?

Paraphrasing involves restating a passage in your own words while summarizing involves condensing a larger text into a shorter version. For example, paraphrasing a quote in an essay would involve rephrasing it in a way that still conveys the original meaning, while summarizing a news article would involve highlighting the main points in a few sentences.

What are the similarities and differences between summarizing and paraphrasing?

Both summarizing and paraphrasing involve rephrasing information in your own words. However, summarizing involves condensing a larger text into a shorter version, while paraphrasing involves restating a passage in your own words. Both techniques are useful for avoiding plagiarism and presenting information in a clear and concise way.

How do you paraphrase a quote in an essay?

To paraphrase a quote in an essay, you should rephrase the quote in your own words while still maintaining its original meaning. This involves understanding the main idea of the quote and expressing it in a way that fits with the rest of your essay. It is important to properly cite the original source of the quote to avoid plagiarism.

When using a source, should you quote, paraphrase, or summarize it?

The choice between quoting, paraphrasing, or summarizing a source depends on the purpose of your writing. If you want to include a specific passage word-for-word, you should quote it. If you want to restate a passage in your own words, you should paraphrase it. If you want to condense a larger text into a shorter version, you should summarize it.

What is the definition of summarizing?

Summarizing is the act of condensing a larger text into a shorter version that highlights the main points of the original. This technique is useful for presenting information in a clear and concise way and can be applied to a variety of texts, such as news articles, research papers, and books.

You might also like

The Ultimate Guide: What Is the Best Definition of Sobriety?

Psychoanalysis vs. behavior therapy: what’s the difference, unlocking the power of music: how it shapes your behavior, stop guessing here’s which phase of strategic conflict management you can ignore.

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Quoting, Paraphrasing, and Summarizing

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

This handout is intended to help you become more comfortable with the uses of and distinctions among quotations, paraphrases, and summaries. This handout compares and contrasts the three terms, gives some pointers, and includes a short excerpt that you can use to practice these skills.

What are the differences among quoting, paraphrasing, and summarizing?

These three ways of incorporating other writers' work into your own writing differ according to the closeness of your writing to the source writing.

Quotations must be identical to the original, using a narrow segment of the source. They must match the source document word for word and must be attributed to the original author.

Paraphrasing involves putting a passage from source material into your own words. A paraphrase must also be attributed to the original source. Paraphrased material is usually shorter than the original passage, taking a somewhat broader segment of the source and condensing it slightly.

Summarizing involves putting the main idea(s) into your own words, including only the main point(s). Once again, it is necessary to attribute summarized ideas to the original source. Summaries are significantly shorter than the original and take a broad overview of the source material.

Why use quotations, paraphrases, and summaries?

Quotations, paraphrases, and summaries serve many purposes. You might use them to:

- Provide support for claims or add credibility to your writing

- Refer to work that leads up to the work you are now doing

- Give examples of several points of view on a subject

- Call attention to a position that you wish to agree or disagree with

- Highlight a particularly striking phrase, sentence, or passage by quoting the original

- Distance yourself from the original by quoting it in order to cue readers that the words are not your own

- Expand the breadth or depth of your writing

Writers frequently intertwine summaries, paraphrases, and quotations. As part of a summary of an article, a chapter, or a book, a writer might include paraphrases of various key points blended with quotations of striking or suggestive phrases as in the following example:

In his famous and influential work The Interpretation of Dreams , Sigmund Freud argues that dreams are the "royal road to the unconscious" (page #), expressing in coded imagery the dreamer's unfulfilled wishes through a process known as the "dream-work" (page #). According to Freud, actual but unacceptable desires are censored internally and subjected to coding through layers of condensation and displacement before emerging in a kind of rebus puzzle in the dream itself (page #).

How to use quotations, paraphrases, and summaries

Practice summarizing the essay found here , using paraphrases and quotations as you go. It might be helpful to follow these steps:

- Read the entire text, noting the key points and main ideas.

- Summarize in your own words what the single main idea of the essay is.

- Paraphrase important supporting points that come up in the essay.

- Consider any words, phrases, or brief passages that you believe should be quoted directly.

There are several ways to integrate quotations into your text. Often, a short quotation works well when integrated into a sentence. Longer quotations can stand alone. Remember that quoting should be done only sparingly; be sure that you have a good reason to include a direct quotation when you decide to do so. You'll find guidelines for citing sources and punctuating citations at our documentation guide pages.

What’s the Difference? Summarizing, Paraphrasing, & Quoting

- Posted on November 29, 2023 November 29, 2023

What’s the Difference? Summarizing , Paraphrasing , & Quoting

Quoting, paraphrasing , and summarizing are three methods for including the ideas or research of other writers in your own work. In academic writing , such as essay writing or research papers , it is often necessary to utilize other people’s writing.

Outside sources are helpful in providing evidence or support written claims when arguing a point or persuading an audience. Being able to link the content of a piece to similar points made by other authors illustrates that one’s writing is not based entirely off personal thoughts or opinions and has support found from other credible individuals. In scientific work such as reports or experiment related writing, being able to point to another published or peer-reviewed writer can strengthen your personal research and even aid in explaining surprising or unusual findings. In all situations, referencing outside sources also elevates the integrity and quality of your work.

When pulling information from an outside source it is critical to properly use quotations, paraphrasing , or summarizing to avoid plagiarizing from the original passage . Plagiarism is portraying another’s work, ideas, and research as one’s own, and is an extremely serious disciplinary offense. Without using proper quotations, paraphrasing and summarizing , it can be easy to unintentionally plagiarize from the original source . Including citations that reference the author also helps ensure proper credit is given, and no accidental plagiarism occurs. Regardless of if APA , MLA or Chicago style are used, a citation must accompany the work of another author.

This article will compare these three concepts, to help users become more comfortable with each of them and the differing scenarios to utilize each. The article will also provide examples and give pointers to further increase familiarity with these essential techniques and prevent the happening of plagiarism .

What is Quoting?

Quoting is the restatement of a phrase, sentence, thought, or fact that was previously written by another author. A proper direct quotation includes the identical text without any words or punctuation adjusted.

One might use a quotation when they want to use the exact words from the original author , or when the author has introduced a new concept or idea that was of their conception. Oftentimes, the author already used concise, well-thought-out wording for an idea and it may be difficult to restate without using a direct quote .

However when repeating content from someone else’s work, one must use quotation marks with a corresponding citation or it will be considered plagiarism . The proper citation may also vary based on the citation style being used.

Examples of Quoting

In order to further the understanding of how to utilize quotes, some examples of incorrect and correct quotation are provided below.

Original Text: As natural selection acts solely by accumulating slight, successive, favorable variations, it can produce no great or sudden modification; it can act only by very short and slow steps

Incorrect Quotation Example: “Because natural selection acts only by accumulating slight, successive favorable variations. It can produce no greater or sudden modification and can only act by very short and slow steps

Correct Quotation Example: “As natural selection acts solely by accumulating slight, successive, favorable variations, it can produce no great or sudden modification; it can act only by very short and slow steps,” (Darwin 510).

The bad example provided does not include the identical text or identical grammar and punctuation to that of the original source . The quote is also lacking one quotation mark and a citation to attribute the initial author. Meanwhile, the good example i s completely identical to the original text and features a correct citation, making it a great example of a quote in use.

What is Paraphrasing ?

Paraphrasing is taking the written work, thoughts, or research of another author and putting it in one’s own words . Correct paraphrasing is done through the restatement of key ideas from another person’s work, but utilizing different words to avoid copying them. Oftentimes, finding synonyms to the words used by the original author helps to paraphrase .

One would use paraphrasing when they hope to capture the key points of a written work in their own writing . Paraphrasing should also be employed when the content of the original source is more important than the wording used. This writing technique is a good strategy to maintain one’s personal writing style throughout a written work.

Similar to quoting, even paraphrased material should be accompanied by the proper citation to avoid plagiarizing the initial author.

Examples of Paraphrasing

Original Content: The Statue of Liberty, one of the most recognizable symbols of freedom and democracy across the world, was a gift of friendship to America from France. Inaugurated in 1886, the statue is 305 feet tall and represents Libertas, the Roman liberty goddess, bearing a torch in her right hand and a tablet in her left hand with the date of the US Declaration of Independence. Broken shackles lay underneath the statue’s drapery, to symbolize the end of all types of servitude and oppression.

Incorrect Paraphrasing Example: The Statue of Liberty is an evident display of freedom and democracy for the whole world, and was created by France for America to represent their friendship. The 305 foot statue of the Roman liberty goddess Libertas was installed in 1886. The Statue of Liberty has a tablet with the US Declaration of Independence date in one hand and a torch in her other. She also has broken shackles on the ground to represent an end to enslavement and oppression.

Correct Paraphrasing Example: France presented the United States with the Statue of Liberty in 1886 to commemorate the two countries friendship. The Roman goddess of liberty, Libertas, stands 305 feet tall as a well-known tribute to freedom and democracy. The statue commemorates the US Declaration of Independence though the tablet in her left hand that accompanies a torch in her right. The Statue of Liberty also celebrates an end to oppression and servitude, indicated by broken chains by her feet ( Diaz, 2019 ).

The incorrect example provided featured a sentence structure that followed too closely to that of the original text. Additionally, the writer only swapped out a few words for very common synonyms so the paraphrased content is ultimately too similar to the original text. An academic work that used this paraphrase would be cited for plagiarism .

On the other hand, the correct example featured paraphrased content that is properly cited, with variety to the sentence structure and text that includes words beyond just synonyms to words in the original content. This example also contains the main ideas, but is ultimately slightly condensed from the original text.

What Is Summarizing ?

Summarizing is providing a brief description of the key ideas from a written work. This description should be in one’s own writing , and is typically significantly shorter than the source material because it only touches on the main points .

Summaries are commonly used when a writer hopes to capture the central idea of a work, without relying on the specific wording that the original author used to explain the idea. They also can provide a background or overview of content needed to understand a topic being discussed. This strategy still captures the meaning of the original text without straying from one’s personal tone and writing style.

Unlike paraphrasing and quoting, a summary does not require an in- text citation and only occasionally needs accreditation to the original writer’s work .

Examples of Summarizing

In order to further the understanding of how to summarize content in your writing, some examples of incorrect and correct summaries for the short children’s story Goldilocks and The Three Bears are provided below.

Incorrect Summary Example: Once upon a time, Goldilocks went for a walk on the beach when she saw a house and went in it. In the house she found three bowls of soup and decided to try them all, but one was too hot, one was too cold and one was just right. Next, Goldilocks tried to sit in three different chairs but only found one that fit her perfectly. Lastly, she went to the back of the house and found three beds. Just like the soup and chairs she tested all of them before picking one that she liked the best and taking a nice long nap. The End.

Correct Summary Example: In Goldilocks and the Three Bears by Robert Southy, a young girl wanders into the house of three bears where she tastes three different porridges; sits in three different chairs; and naps in three different beds before finding one of each that fits her. Goldilocks is eventually found by the bears who are upset about her intrusion and usage of their personal belongings.

The incorrect example provided would not be considered a good summary for a few reasons. Primarily, this summary does not summarize well, as provides too much unnecessary detail and an individual would still be able to comprehend the main point of the story without it. The summary also ends without touching on the most important point , which is the lesson of the story. This summary also provides inaccurate information, and lacks a citation.

Meanwhile, the correct example is a good summary because it does not spend too much time on any certain aspect of the story. The reader is still able to understand exactly what happens to Goldilocks without consuming any non-essential details. This summary also provides completely accurate information and touches on the main point or lesson from the story.

Differences and Similarities

There are a few major differences and similarities between the three writing techniques discussed.

Quoting, paraphrasing , and summarizing are similar in that they are all writing techniques that can be used to include the work of other authors in one’s own writing . It is common for writers to use these strategies collectively in one piece to provide variety in their references and across their work. These three strategies also share the similarity of helping to prevent plagiarizing the content from the original source . All three of these methods require some form of citation and attribution to the original author to completely avoid plagiarizing.

Oppositely, the main difference between quoting, paraphrasing , and summarizing is that quoting is done word for word from the original work . Both paraphrasing and summarizing only touch on the key points and are written with some variation from the initial author’s work , usually in the style and tone of the new author. When comparing just the latter two, paraphrased material tends to be closer in length to the actual material, because it only slightly condenses the original passage . On the other hand, a summary is most likely significantly shorter than the original author’s work since this method only pulls from the most important points .

Final Thoughts