- Mission and history

- Platform features

- Library Advisory Group

- What’s in JSTOR

- For Librarians

- For Publishers

In defense of the humanities: Upholding the pillars of human understanding

This essay is part of a series exploring the enduring importance of the humanities. Stay tuned for more insights on why the humanities still matter.

Loss and literature

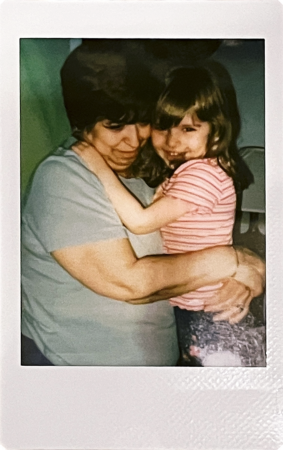

Maria and her grandmother, 2003.

Often, the shortest stories are the most resonant.

In 2020, I lost my maternal grandmother. “Maternal,” in her case, was more than a qualifier–she quite literally played the role of “mother” in my life. My first words, my first steps, and the most formative milestones of my childhood and adolescence happened in her care. She bore the brunt of my insufferable teenage angst, offering a consoling embrace when life seemed to get ahead of me. When I lost her, a chapter of my life ended.

To lose such a constant in one’s early twenties is to lose a tether to one’s reality. The years after my grandmother’s death have been fraught with uncertainty. How could I possibly recover from such a loss? How are my accomplishments meaningful if she is not present to witness them? And, perhaps most disconcerting: who will I be by the time my own life begins to wane?

Everyone copes with and experiences loss differently. For me, it was acutely alienating. My relationship with my grandmother was singular, making my perspective on loss unique. I operated for what felt like ages on the assumption that no matter how much support I had, I could not possibly be seen.

That is, until I picked up A Very Easy Death . This brief, 112-page memoir by Simone de Beauvoir details her mother’s final days from an honest, compassionate perspective. Laden with recollections of a mother-daughter relationship and personal confrontations with mortality, it resonated with me in a way that no other text had. The acts of death and grief are explored in her memoir as though de Beauvoir were sitting across from me at a bistro recounting the experience. For the first time since my own experience and despite preceding me by thirty-six years, someone had finally seen me.

The humanities: Studies of the human condition

The connection I achieved through literature highlights the critical importance of the humanities. Encompassing history, literature, philosophy, art, and more, the humanities provide a lens through which one can view one’s personal experiences–making the universal personal and the personal universal.

The humanities and humanism have evolved significantly over centuries. In Western society, humanism traces back to Greece in the fourth and fifth centuries BCE. Sophists saw humanism as a cultural-educational program, aiming for the development of human faculties and excellence, as noted in Perez Zagorin’s “On Humanism Past & Present.”

Agrippa: Human Proportions in Square. n.d. Wellcome Collection.

In Rome, the concept evolved into “an ideal expressed in the concept of humanitas … [which] designated a number of studies–philosophy, history, literature, rhetoric, and training in the oratory.” Most influential, though, was the humanism that emerged from the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries that was “centered increasingly upon human interests and moral concerns rather than religion.” Its purpose was to cultivate a population of Christian men who were well-spoken, literate, and capable of integrating with high society.

Growing more secular over time, humanist values began to compete with the physical and biological sciences, the social sciences, and other modern subjects which comprised nineteenth century liberal education. Zagorin suggests that scientific and empirical research approaches overtook human-centered perspectives, particularly after the massive loss of life in World War I and the disillusionment that followed.

“Through de Beauvoir’s philosophical inquiries into life and death, I was able to confront and process my own grief more profoundly. Her reflections on mortality and the mother-daughter relationship resonated deeply with me, helping me to navigate my personal loss while also offering insights into the universal human condition.”

Scholarly perspectives on the importance of the humanities

Scholars argue that the humanities are essential for comprehending complex social dynamics and ethical questions. In “The Power of the Humanities and a Challenge to Humanists,” Richard J. Franke argues that humanistic interpretation “contributes to a tradition of interpretation.” Franke posits that human emotions and values are at the core of humanistic study, offering the ability to explore domains that “animate the human experience.” This is precisely how my engagement with Simone de Beauvoir’s memoir, A Very Easy Death, provided a foundation for evaluating broader human concerns.

Le Brun, Charles, 1619-1690., and Hebert, William, fl. 18th century. A Man Whose Profile Expresses Compassion. n.d. Wellcome Collection.

Through de Beauvoir’s philosophical inquiries into life and death, I was able to confront and process my own grief more profoundly. Her reflections on mortality and the mother-daughter relationship resonated deeply with me, helping me to navigate my personal loss while also offering insights into the universal human condition. This connection underscores the humanities’ power to transform personal experiences into a deeper understanding of shared human emotions and values.

Moreover, Franke postulates that subjects under the humanities all lend themselves to critical thinking, which he defines as “that Socratic habit of articulating questions and gathering relevant information in order to make reasonable judgements.” Through the humanities, one can approach topics from varied vantage points to develop a holistic understanding of them.

In a study published in 2018 by the Journal of General Internal Medicine , medical students across institutions suggested that exposure to the humanities had an appreciable influence on their “tolerance of ambiguity, empathy, and wisdom.” The study’s discussion section further indicates that both the performance and observance of drama increase empathy, and that “even good literature prompts better detection of emotions.” These findings highlight that studying the humanities cultivates essential skills and attributes that have practical applications in real-world settings.

Scholarship, then, suggests that the humanities teach us to be human, whether through the ability to form nuanced questions or to feel empathy. I experienced this firsthand while reading Simone de Beauvoir’s A Very Easy Death. Her detailed account of her mother’s final days helped me navigate my own grief. It also gave me a deeper understanding of the emotional complexities involved in facing mortality as a concept. These characteristics—developed through engagement with the humanities—can improve interpersonal relationships and foster a more empathetic and accepting society.

The impact of the humanities extends beyond personal growth; it influences professional practices and societal outcomes. The empathy and wisdom nurtured by humanities education can enhance the quality of patient care in the medical field, as evidenced by the medical students’ testimonies. Similarly, professionals in law, education, and public policy benefit from the critical thinking and ethical reasoning stimulated by humanities education. By emphasizing these real-world applications, we can better advocate for the continued support and integration of the humanities in various sectors of society.

Challenges affecting the humanities: Economic pressures and academic isolation

Even in light of their demonstrated value, the humanities face significant challenges that threaten their vitality and relevance. In “ The Decline of the Humanities and the Decline of Society,” Ibanga B. Ikpe describes how today’s labor market increasingly demands qualifications for specific sectors. Courses in the humanities that are not tailored to particular career paths put them at a disadvantage in universities.

Ikpe also attributes the decline in humanities education to the fact that “economic rather than academic motivations have become the primary basis for decision making in universities.” He raises the notion that the humanities and similar disciplines cannot be elucidated into digestible pieces of information, which makes them more difficult to sell. The more defined the subject, the more profitable. Thus, funding for humanities programs at educational institutions has reduced significantly. This has both limited resources for teaching and research and signaled a devaluation of the humanities as a whole.

Finally, Ikpe presents the argument that humanities scholars are partially to blame for the current state of the humanities. He raises the accusation that humanities scholars have become withdrawn from greater society, sequestering themselves in academia. The niche views and dialogues they produce in this environment may sever their connection with a broader audience.

Sustaining the humanities today

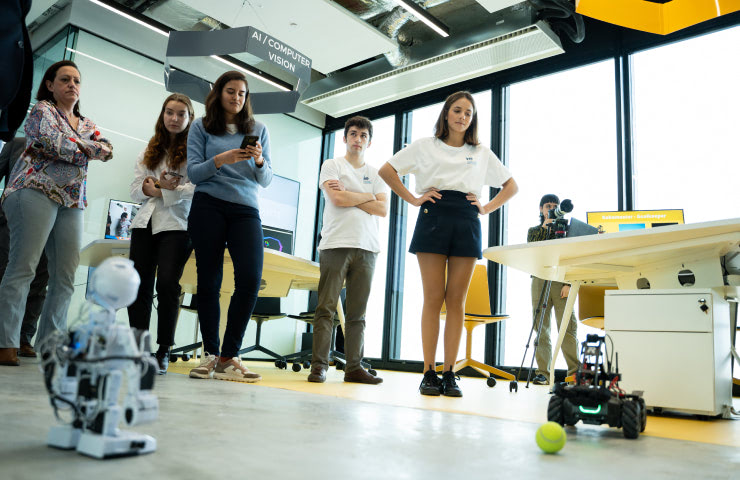

The future implied by the above rings grim, but there are still significant opportunities to advocate for the humanities by highlighting their interdisciplinary relevance to contemporary issues. For example, the study of ethics in philosophy can provide crucial insights into debates on artificial intelligence and biotechnology. Similarly, understanding historical contexts can help policymakers make informed decisions about current social and political challenges.

Organizations like JSTOR play a crucial role in preserving and promoting the humanities. JSTOR’s vast digital library of academic journals, books, and primary sources ensures that humanities scholarship remains accessible to students, researchers, and the public, advancing knowledge, strengthening critical thinking, and supporting interdisciplinary studies.

ITHAKA, the parent organization of JSTOR, is also increasing the utility of this knowledge. More than a mere repository, ITHAKA uses technology to analyze and contextualize vast amounts of information, making it more accessible and meaningful. By doing so, they help transform scholarly resources into practical tools that can drive real change in society. Their initiatives facilitate connections between research and practice, allowing the humanities to inform solutions to contemporary challenges.

By leveraging the support of organizations like JSTOR and embracing technological advancements, we can turn the tide in favor of the humanities. Advocating for their interdisciplinary relevance and addressing contemporary social issues will ensure that these vital disciplines thrive. The humanities are not relics of the past—they are essential to navigating the complexities of the present and shaping the future.

Hilbert College Global Online Blog

Why are the humanities important, written by: hilbert college • feb 8, 2023.

Why Are the Humanities Important? ¶

Do you love art, literature, poetry and philosophy? Do you crave deep discussions about societal issues, the media we create and consume, and how humans make meaning?

The humanities are the academic disciplines of human culture, art, language and history. Unlike the sciences, which apply scientific methods to answer questions about the natural world and behavior, the humanities have no single method or tools of inquiry.

Students in the humanities study texts of all kinds—from ancient books and artworks to tweets and TV shows. They study the works of great thinkers throughout history, including the Buddha, Homer, Aristotle, Dante, Descartes, Nietzsche, Austen, Thoreau, Darwin, Marx, Du Bois and King.

Humanities careers can be deeply rewarding. For students having trouble choosing between the disciplines that the humanities have to offer, a degree in liberal studies may be the perfect path. A liberal studies program prepares students for various exciting careers and teaches lifelong learning skills that can aid graduates in any career path they take.

Why We Need the Humanities ¶

The humanities play a central role in shaping daily life. People sometimes think that to understand our society they must study facts: budget allocations, environmental patterns, available resources and so on. However, facts alone don’t motivate people. We care about facts only when they mean something to us. No one cares how many blades of grass grow on the White House lawn, for example.

Facts gain meaning in a larger context of human values. The humanities are important because they offer students opportunities to discover, understand and evaluate society’s values at various points in history and across every culture.

The fields of study in the humanities include the following:

- Literature —the study of the written word, including fiction, poetry and drama

- History —the study of documented human activity

- Philosophy —(literally translated from Greek as “the love of wisdom”) the study of ideas; comprising many subfields, including metaphysics, epistemology, ethics and aesthetics

- Visual arts —the study of artworks, such as painting, drawing, ceramics and sculpture

- Performing arts —the study of art created with the human body as the medium, such as theater, dance and music

Benefits of Studying the Humanities ¶

There are many reasons why the humanities are important, from personal development and intellectual curiosity to preparation for successful humanities careers—as well as careers in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) and the social sciences.

1. Learn How to Think and Communicate Well ¶

A liberal arts degree prepares students to think critically. Because the study of the humanities involves analyzing and understanding diverse and sometimes dense texts—such as ancient Greek plays, 16th century Dutch paintings, American jazz music and contemporary LGBTQ+ poetry—students become skilled at noticing and appreciating details that students educated in other fields might miss.

Humanities courses often ask students to engage with complex texts, ideas and artistic expressions; this can help them develop the critical thinking skills they need to understand and appreciate art, language and culture.

Humanities courses also give students the tools they need to communicate complex ideas in writing and speaking to a wide range of academic and nonacademic audiences. Students learn how to organize their ideas in a clear, organized way and write compelling arguments that can persuade their audiences.

2. Ask the Big Questions ¶

Students who earn a liberal arts degree gain a deeper understanding of human culture and history. Their classes present opportunities to learn about humans who lived long ago yet faced similar questions to us today:

- How can I live a meaningful life?

- What does it mean to be a good person?

- What’s it like to be myself?

- How can we live well with others, especially those who are different from us?

- What’s really important or worth doing?

3. Gain a Deeper Appreciation for Art, Language and Culture ¶

Humanities courses often explore art, language and culture from different parts of the world and in different languages. Through the study of art, music, literature and other forms of expression, students are exposed to a wide range of perspectives. In this way, the humanities help students understand and appreciate the diversity of human expression and, in turn, can deepen their enjoyment of the richness and complexity of human culture.

Additionally, the study of the humanities encourages students to put themselves in other people’s shoes, to grapple with their different experiences. Through liberal arts studies, students in the humanities can develop empathy that makes them better friends, citizens and members of diverse communities.

4. Understand Historical Context ¶

Humanities courses place artistic and cultural expressions within their historical context. This can help students understand how and why certain works were created and how they reflect the values and concerns of the time when they were produced.

5. Explore What Interests You ¶

Ultimately, the humanities attract students who have an interest in ideas, art, language and culture. Studying the humanities has the benefit of enabling students with these interests to explore their passions.

The bottom line? Studying the humanities can have several benefits. Students in the humanities develop:

- Critical thinking skills, such as the ability to analyze dense texts and understand arguments

- A richer understanding of human culture and history

- Keen communication and writing skills

- Enhanced capacity for creative expression

- Deeper empathy for people from different cultures

6. Prepare for Diverse Careers ¶

Humanities graduates are able to pursue various career paths. A broad liberal arts education prepares students for careers in fields such as education, journalism, law and business. A humanities degree can prepare graduates for:

- Research and analysis , such as market research, policy analysis and political consulting

- Nonprofit work , social work and advocacy

- Arts and media industries , such as museum and gallery support and media production

- Law, lobbying or government relations

- Business and management , such as in marketing, advertising or public relations

- Library and information science , or information technology

- Education , including teachers, curriculum designers and school administrators

- Content creation , including writing, editing and publishing

Employers value the strong critical thinking, communication and problem-solving skills that humanities degree holders possess.

5 Humanities Careers ¶

Humanities graduates gain the skills and experience to thrive in many different fields. Consider these five humanities careers and related fields for graduates with a liberal studies degree.

1. Public Relations Specialist ¶

Public relations (PR) specialists are professionals who help individuals, organizations and companies communicate with public audiences. First and foremost, their job is to manage their organizations’ or clients’ reputation. PR specialists use various tactics, such as social media, events like fundraisers and other media relations activities to shape and maintain their clients’ public image.

PR specialists have many different roles and responsibilities as part of their daily activities:

- Creating and distributing press releases

- Monitoring and analyzing media coverage (such as tracking their clients’ names in the news)

- Organizing events

- Responding to media inquiries

- Evaluating the effectiveness of PR campaigns

How a Liberal Studies Degree Prepares Graduates for PR ¶

Liberal studies majors are required to participate in class discussions and presentations, which can help them develop strong speaking skills. PR specialists often give presentations and speak to the media, so strong speaking skills are a must.

PR specialists must also be experts in their audience. The empathy and critical thinking skills that graduates develop while they earn their degree enables them to craft tailored, effective messages to diverse audiences as PR specialists.

Public Relations Specialist Salary ¶

The median annual salary for PR specialists was $62,800 in May 2021, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. The BLS expects the demand for PR specialists to grow by 8% between 2021 and 2031, faster than the average for all occupations.

The earning potential for PR specialists can vary. The size of the employer can affect the salary, as can the PR specialist’s level of experience and education and the specific duties and responsibilities of the job.

In general, PR specialists working for big companies in dense urban areas tend to earn more than those working for smaller businesses or in rural areas. Also, PR specialists working in science, health care and technology tend to earn more than those working in other industries.

BLS data is a national average, and the salary can also vary by location; for example, since the cost of living is higher in California and New York, the average salaries in those states tend to be higher compared with those in other states.

2. Human Resources Specialist ¶

Human resources (HR) specialists are professionals who are responsible for recruiting, interviewing and hiring employees for an organization. They also handle employee relations, benefits and training. They play a critical role in maintaining a positive and productive work environment for all employees.

How a Liberal Studies Degree Prepares Graduates for HR ¶

Liberal studies majors hone their communication skills through coursework that requires them to write essays, discussion posts, talks and research papers. These skills are critical for HR specialists, who must communicate effectively with company stakeholders, such as employees, managers and corporate leaders.

Additionally, because students who major in liberal studies get to understand the human experience, their classes can provide deeper insight into human behavior, motivation and communication. This understanding can be beneficial in handling employee relations, conflict resolution and other HR-related issues.

Human Resources Specialist Salary ¶

The median annual salary for HR in the U.S. was $122,510 in May 2021, according to the BLS. The demand for HR specialists is expected to grow by 8% between 2021 and 2031, per the BLS, faster than the average for all occupations.

3. Political Scientist ¶

A liberal studies degree not only helps prepare students for media and HR jobs—careers that may be more commonly associated with humanities—but also prepares graduates for successful careers as political scientists.

Political scientists are professionals who study the theory and practice of politics, government and political systems. They use various research methods, such as statistical analysis and historical analysis, to study political phenomena: elections, public opinions, the effects of policy changes. They also predict political trends.

How the Humanities Help With Political Science Jobs ¶

Political scientists need to have a deep understanding of political institutions. They have the skills to analyze complex policy initiatives, evaluate campaign strategies and understand political changes over time.

A liberal studies program provides a solid foundation of critical thinking skills that can sustain a career in political science. First, liberal studies degrees can teach students about the histories and theories of politics. Knowing the history and context of political ideas can be useful when understanding and evaluating current political trends.

Second, graduates with a liberal studies degree become accustomed to communicating with diverse audiences. This is a must to communicate with the public about complex policies and political processes.

Political Scientist Specialist Salary ¶

According to the BLS, the median annual wage for political scientists was $122,510 in May 2021. The BLS projects that employment prospects for political scientists will grow by 6% between 2021 and 2031, about as fast as the average for all occupations.

4. Community Service Manager ¶

Community service managers are professionals who are responsible for overseeing and coordinating programs and services that benefit the local community. They may work for a government agency, nonprofit organization or community-based organization in community health, mental health or community social services.

Community service management includes the following:

- Training and overseeing community service staff and volunteers

- Securing and allocating resources to provide services such as housing assistance, food programs, job training and other forms of social support

- Developing and implementing efficient and effective community policies

- Fundraising and applying for grants grant to secure funding for their programs

In these and many other ways, community service managers play an important role in addressing social issues and improving the quality of life for people in their community.

Community Service Management and Liberal Studies ¶

Liberal studies prepares graduates for careers in community service management by providing the tools for analyzing and evaluating complex issues. These include tools to work through common dilemmas that community service managers may face. Such challenges include the following:

- What’s the best way to allocate scarce community mental health resources, such as limited numbers of counselors and social workers to support people experiencing housing instability?

- What’s the best way to monitor and measure the success of a community service initiative, such as a Meals on Wheels program to support food security for older adults?

- What’s the best way to recruit and train volunteers for community service programs, such as afterschool programs?

Because the humanities teach students how to think critically, graduates with a degree in liberal studies have the skills to think through these complex problems.

Community Service Manager Salary ¶

According to the BLS, the median annual wage for social and community managers was $74,000 in May 2021. The BLS projects that employment prospects for social and community managers will grow by 12% from 2021 to 2031, much faster than the average for all occupations.

5. High School Teacher ¶

High school teachers educate future generations, and graduates with a liberal studies degree have the foundation of critical thinking and communication skills to succeed in this important role.

We need great high school teachers more than ever. The U.S. had a shortage of 300,000 teachers in 2022, according to NPR and the National Education Association The teacher shortage particularly affected rural school districts, where the need for special education teachers is especially high.

How the Humanities Prepare Graduates to Teach ¶

Having a solid understanding of the humanities is important for individuals who want to become a great high school teacher. First, a degree that focuses on the humanities provides graduates with a deep understanding of the subjects that they’ll teach. Liberal studies degrees often include coursework in literature, history, visual arts and other subjects taught in high school, all of which can give graduates a strong foundation in the material.

Second, liberal studies courses often require students to read, analyze and interpret texts, helping future teachers develop the skills they need to effectively teach reading, writing and critical thinking to high school students.

Third, liberal studies courses often include coursework in research methods, which can help graduates develop the skills necessary to design and implement engaging and effective lesson plans.

Finally, liberal studies degrees often include classes on ethics, philosophy and cultural studies, which can give graduates the ability to understand and appreciate different perspectives, cultures and life experiences. This can help future teachers create inclusive and respectful learning environments and help students develop a sense of empathy and understanding toward others.

Overall, a humanities degree can provide graduates with the knowledge, skills and abilities needed to be effective high school teachers and make a positive impact on the lives of their students.

High School Teacher Salary ¶

According to the BLS, the median annual wage for high school teachers was $61,820 in May 2021. The BLS projects that the number of high school teacher jobs will grow by 5% between 2021 and 2031.

Take the Next Step in Your Humanities Career ¶

A bachelor’s degree in liberal studies is a key step toward a successful humanities career. Whether as a political scientist, a high school teacher or a public relations specialist, a range of careers awaits you. Hilbert College Global’s online Bachelor of Science in Liberal Studies offers students the unique opportunity to explore courses across the social sciences, humanities and natural sciences and craft a degree experience around the topics they’re most interested in. Through the liberal studies degree, you’ll gain a strong foundation of knowledge while developing critical thinking and communication skills to promote lifelong learning. Find out how Hilbert College Global can put you on the path to a rewarding career.

Indeed, “13 Jobs for Humanities Majors”

NPR, The Teacher Shortage Is Testing America’s Schools

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, High School Teachers

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Human Resources Specialists

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Political Scientists

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Public Relations Specialists

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Social and Community Service Managers

Recent Articles

Humanities vs. Liberal Arts: How Are They Different?

Hilbert college, feb 5, 2023.

What Is Liberal Studies? Curriculum, Benefits and Careers

Oct 26, 2022.

Starting a Podcast: Checklist and Resources

Dec 12, 2023, learn more about the benefits of receiving your degree from hilbert college.

- Enroll & Pay

Why the humanities?

What are the humanities and why do they matter.

The humanities include disciplines such as history, literature, philosophy, and religious studies; they feature prominently in interdisciplinary departments such as African and African American Studies, Indigenous Studies, and Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies; they also have much in common with the arts and social sciences.

These disciplines help us to understand who we are, what it means to be human, how we relate to others, and the pathways that have led us to this point in time. We cannot navigate our way through the present into the future without a balanced understanding of our diverse, complicated, and often problematic pasts. Appreciating what it means to be human, how relationships work, and how perspectives on these questions vary from culture to culture – these are crucial to our present and future. The humanities take us there.

In a rapidly transforming world and workplace, we need more than ever to nurture critical thinking and the capacity for problem-solving. As a growing number of employers are pointing out, specific skills become increasingly ephemeral in an ever-changing workplace; what they need are employees who can analyze carefully, think creatively, and express themselves clearly, skills fostered by the humanities. Those skills are and will be crucial ingredients for professional success in the bracing twenty-first century workplace. The humanities take us there.

Literacy and critical thinking also play a crucial role in the democratic process, which depends on a citizenry prepared to engage actively and thoughtfully with current events, committed to creative and innovative solutions instead of blind deference to tradition and authority, and watchful of our hard-won freedoms. The humanities take us there.

Every day we witness the many ways in which the world around us becomes ever more interconnected and yet remains deeply divided. The humanities help nurture connections within and between diverse societies, offering pathways for constructive engagement. Learning about and respecting outlooks different from our own is crucial to our survival in the twenty-first century, moving us away from tensions created by ignorance and fear toward informed, sympathetic conversation between cultures. That does not mean forsaking our own identities and loyalties, but it does involve developing the capacity to see beyond them. The humanities take us there.

The expansion of humanistic inquiry in recent decades to recover the voices and past lives of people who have been either ignored or systematically removed from historical narratives and literary canons fits closely with broader trends in our culture toward greater inclusion and a recognition of diverse voices and histories. We are an indispensable part of that process as we seek to understand the many constituent parts that together make up the complex world we inhabit. The humanities take us there.

The humanities are not an optional and unaffordable luxury, as some critics would have us believe. What we do as humanities scholars and in our classrooms could not be more relevant to the world we live in; nor could they be more practical in terms of the skills we need as twenty-first-century citizens. The humanities are a necessity – and not only from a utilitarian perspective. We cannot surrender to a vision of the future that fixates on a narrow economic conception of what is productive and useful. What about our responsibility to nurture our individual capacity for creativity and artistic expression? These are also crucial measurements of our worth, success, and wealth as human beings. We should never undervalue the personal fulfillment and happiness that we can draw from literature, art, music, theater, philosophy, religious studies, and history. An appreciation of our diverse cultural legacies enriches our lives, individually and collectively, and the same is true of becoming actively involved as participants in the creation of new cultural forms. As a growing body of research demonstrates, cultural vitality and personal happiness ultimately lead to economic growth. The humanities take us there.

Please join the quest to support, create, and disseminate new ideas that open our minds, reveal new ways of understanding who we are, and uncover the histories that brought us to the moment we now live in!

(By Richard Godbeer, former director of the Hall Center for the Humanities)

The Hall Center, one of 11 designated research centers that fall under the auspices of the University of Kansas Office of Research, provides an intellectual hub for scholars in the humanities and fosters interdisciplinary conversation across the University of Kansas. Through its public programming, the Hall Center makes visible the significance and relevance of humanities research, engaging broad, diverse communities across the state in dialogue about compelling local, national, and global issues that humanities research addresses. The Hall Center acts on the conviction that the humanities must play a critical role in constructing a humane future for our world.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Critical & Creative Thinking

Key Concepts

This chapter will prepare you to:

- Explain the concepts of critical thinking.

- Evaluate the merits of the questions, not just the answers.

- Evaluate the origins of our values.

- Discuss the implications of perceptions and stereotypes as they relate to an individual.

- Identify historical, geographical, and cultural contexts.

In the Introduction , we presented the idea of metacognition, which is the first step in applying critical and creative thinking to our study of the humanities. We all view the world through a lens; one shaped by our personal experiences. So, to objectively analyze a news story, cartoon, painting, photograph, essay, song, or any number of ways we express our human experience, we begin by being aware of how our brain works.

You may hear the phrase “critical thinking” used many times in a humanities course. In the context of humanities, critical thinking is the process of reflection about our personal values, paradigms, and experiences. Creative thinking is another important tool for studying the humanities. By “creative thinking,” we mean challenging what you think you know and asking you to think outside the box. Creative thinking also acknowledges and explores how other people may see or experience the world differently from us.

Throughout this book are Questions for Critical & Creative Thinking . These questions may present novel situations or be tough to answer. They are designed to help you reflect on why you perceive the world the way you do and perhaps why someone else might see things differently. Some questions may prompt you to expand your personal perspective.

The Looking Exercises and Listening Exercises included at the end of this chapter will help you practice these approaches to critical and creative thinking.

Creative Approaches to Critical Thinking

What is critical thinking.

A key component of critical thinking is analyzing a person or event from multiple perspectives . The opposite of critical thinking would be characterizing a group of people based on a singular experience with one individual. Not only does this limited perspective interfere with critical and creative thinking, but it may also lead us to treat people or situations with unrealistic expectations.

Credit: Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie. “ The Danger of a Single Story .” TEDGlobal 2009. July 2009. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 International. https://www.ted.com/talks/chimamanda_ngozi_adichie_the_danger_of_a_single_story.

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie discusses the damage caused by people’s limited perceptions. She starts by sharing her perceptions of people from her childhood in Nigeria. She then moves on to other people’s perceptions of her and Nigerian culture when she was a student in the United States.

Questions for Critical & Creative Thinking

- Have you ever been subjected to a stereotype?

- Where do you think the basis of this assumption came from? Is there any truth to the idea?

- Do you feel like these stereotypes limit you or encourage you?

What Do We Know?

Our reaction to information—whether it comes via images, sound, or words—is informed by our value systems. Our value systems, in turn, are shaped by personal experience and learned knowledge.

Consider something as fundamental as clothing. The sight of a man wearing a skirt in Salt Lake City would be unusual enough that he would probably elicit some stares. However, maybe not from people living in Scotland or the Pacific islands. This is an example of a response informed by cultural context. In this case, about what is regarded as normal or acceptable attire for men to wear in public. There are also historical imperatives. In present-day society, men and women frequently wear jeans or pants. However, 100 years ago, a woman wearing pants was neither a common nor acceptable fashion statement.

Can you choose which of the following historical factors were at play to allow women in the United States the freedom to wear “men’s” clothing?

- The suffrage movement for women’s right to vote

- World War I and World War II (Hint: military conscription of men necessitated a female workforce.)

- The birth control pill

Think about what people considered normal in earlier historical settings and reflect on your own reaction.

- Do you think they are silly? Funny?

- Or were their standards acceptable because they were based on the information available at the time?

Let us look at another example, this time a symbol most likely associated with negative reactions. The swastika symbol was adopted by the Nazi party during World War II. Because of this, most people perceive the swastika as a symbol of murder and destruction.

The origins of this symbol reach back much further than 20 th -century Germany. The oldest known swastika is estimated to be about 15,000 years old , which puts it in the Paleolithic Period (Stone Age). Throughout history, the swastika was used in regions all over the world, including China, Japan, India, and southern Europe. It has been used to represent good luck, prosperity, and the sun. If not equipped with this knowledge before traveling abroad, it would be easy to assume that Nazi sympathizers had lived in these countries.

Questions to Critical & Creative Thinking

- Prior to reading about the history of the swastika, what conclusions might you have reached if you visited a building displaying a swastika on the wall?

- A swastika symbol on Japanese maps indicates the location of a Buddhist temple. In preparation for the 2020 Olympics, Japan’s national mapmaking department is considering changing the map symbol to something else. Do you think they should or should not change the symbol? Why or why not? Can you think of another way to resolve this issue?

What Is a Creative Approach to Critical Thinking?

As you might imagine from the swastika example, challenging long-held values or beliefs can cause conflict among people, and perhaps discomfort for an individual person. However, it is important to remember that critical and creative thinking does not require you to change your mind but rather, evaluate how you got there. One way to look at it is to imagine that critical thinking is like taking something apart, while creative thinking is like recycling or repurposing something. In the end, you may still end up with the same beliefs. Or you may discover you have acquired some new values.

Again, the goal is to get you thinking about how you think. In an early scene from the movie, The Matrix (1999) , the character Orpheus offers the protagonist Neo a blue pill and a red pill.

“You take the blue pill, the story ends, you wake up in your bed and believe whatever you want to believe. You take the red pill, you stay in wonderland, and I show you how deep the rabbit hole goes.”

Likewise, by encouraging you to think critically and creatively, this course offers you a similar choice. You can superficially engage with the various artifacts presented throughout this book, skip the critical and creative thinking questions, and finish the book with your points of view pretty much unchanged. Or you can accept occasionally feeling uncomfortable as you delve deeper into how people across the centuries and around the world have tried to make sense of the human condition. Blue pill or red pill? You choose!

How to Approach an Artifact

Another critical thinking tool is the use and analysis of artifacts. A humanities artifact could be a piece of writing, music, painting, drawing, sculpture, dance, film, or any number of created works. In her article “ A Method for Reading, Writing, & Thinking Critically ,” Kathleen McCormick explains that we should consider the historical and cultural context when analyzing an artifact of written text. Additional contexts for approaching any type of artifact include economic, political, geographical, social, and religious, to name a few. These contextual pieces offer clues as to what may have motivated a person to compose or create an artifact. Analyzing context can also help us to determine how relevant an artifact is to our contemporary experiences.

In addition to considering context, it is important to ask a series of questions when approaching an artifact of the humanities. Critical and creative thinking encourages us to be actively engaged with a piece of text, music, or art. Some questions you should be asking yourself as you engage with the artifacts presented in this chapter, as well as the rest of the book include:

- Who is the author or creator of the artifact?

- What do we know about the artifact’s historical context, i.e., what was happening when the artifact was created?

- What was the inspiration or motivation for creating this artifact? For example, was it a commissioned piece or spontaneous creation?

- For written text, is there a narrative voice? If so, is it first person or third?

- Does who is speaking make a difference for a narrative?

- What is the main message the author or creator is trying to convey?

- Who, if any, is the author or creator’s intended audience?

- Does this artifact present a familiar concept or message? Is it something new for you?

- Does the author or creator’s message align or conflict with your values?

When we engage with humanities artifacts and then apply critical and creative thinking, we are not merely going through a process of decoding. Hopefully, this book helps you understand that analyzing the humanities using this approach is a sincere thoughtful process that helps broaden your understanding of what the humanities are and why understanding them is so important.

Looking Exercises: Architecture and Painting

These exercises will help you practice using critical and creative analysis of a humanities artifact through a couple of visual examples: building architecture and political painting.

The visual arts are a broad umbrella encompassing artifacts that are appreciated by looking at them. These arts include painting, drawing, sculpture, ceramics, photography, video, printmaking, crafts, architecture, textiles, and much more. These artifacts are the result of people trying to make sense of their physical and inner worlds, and conveying that understanding to other people.

An important first question to ask when considering a visual arts artifact is, was the work commissioned? Meaning, was the piece created at the request of someone else, such as a government, individual, nonprofit group, political group, or otherwise? Naturally, the sentiment embodied in the artifact and the intended audience will likely align with the values of the group or person who commissioned it rather than the artist who created it.

Other important questions might include, when was the piece created? What political issues were prominent at the time? What historical events were happening? By gathering as much contextual information as possible about the artifact, we are better equipped to interpret the artifact’s message or intention.

Architecture

The built environment reflects the age and cultural context in which it was produced. Architecture gives us easy access to visual arts artifacts for analysis. Some contextual questions we can ask:

- What does the style of architecture in my city tell me about the cultural influences of my society?

- Is there a philosophical influence?

- How old is the city?

- Does it maintain some of the influence of the original settlers? If so, how and where did that influence come from?

Architecture may also reflect a building’s function. Public buildings tend to be open and inviting. Some buildings may be designed to deflect attention. The nondescript architecture of homeless shelters helps conceal the vulnerable people living there. This kind of architecture is known as hostile architecture.

For this exercise, use the contextual questions listed above (as well as ones of your own) to analyze the architectural artifact presented by the White House in Washington DC, which was built in 1792. And compare it with Frank Gehry’s Disney Concert Hall, built in Los Angeles in 2003.

Looking at a piece of art, we can ask whether what we see relates to our contemporary setting. Sometimes, in order to fully understand an artifact, we must be familiar with the historical, political, or social context surrounding its creation.

The painting Guernica by Pablo Picasso was first displayed in Paris on May 1, 1937. He painted it during the midst of the Spanish Civil War (July 1936–April 1939) as an artistic reaction to the Nazi’s bombing of the Basque town on April 26, 1937 . The painting is monochromatic, to show the misery inflicted by the aerial bombardment. The images in the painting present the tragedy and suffering of the war: a dismembered soldier and nurse; an all-seeing eye; and the Spanish symbols of a bull and a horse.

One contextual question to ask is, does Picasso’s painting only hold relevance to the Spanish Civil War? Two examples of contemporary situations demonstrate that this painting can be relevant beyond what Picasso may have originally intended. In fact, this artifact presents timeless relevancy to the perception, interpretation, and expression of our human experiences during a war.

On February 28, 1974 , Tony Shafrazi entered the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, and red-spray painted the words “Kill Lies All” over the Guernica. Shafrazi said this was “ a protest against the release on bail of the lieutenant later convicted for his role in the My Lai massacre during the Vietnam War.” The red paint was easily removed, as Guernica was heavily varnished.

On February 5, 2003, Colin Powell delivered a speech at the United Nations (UN) headquarters to make the case for war with Iraq. He was standing in front of a tapestry of Picasso’s Guernica, which hangs in the UN as a reminder of the horror of war and the need for diplomacy first. The tapestry was covered with a blue sheet.

Reports of the UN’s position behind this action vary and the organization did not release an official statement. However, using contextual information, such as the painting’s history, we can deduce some logical reasons. The New York Times reported the UN started covering the tapestry because they were afraid a horse’s screaming head would be visible next to chief UN weapons inspector Hans Blix while he spoke. The article offered an alternative reason , “Mr. Powell can’t very well seduce the world into bombing Iraq surrounded on camera by shrieking and mutilated women, men, children, bulls and horses.”

An article in the Toronto Star ran the quote , “A [un-named] diplomat stated that it would not be an appropriate background if the ambassador of the United States at the U.N. John Negroponte, or Powell, talk about war surrounded with women, children and animals shouting with horror and showing the suffering of the bombings.”

Listening Exercises: Songs and Music

These two exercises apply to how our values shape our listening choices, both in conversations and songs. As described, we prefer listening to speech and music that agree with our values and ideas. In other words, we gravitate to news channels, influential people, and song lyrics that support our world view. This tendency to seek out similar viewpoints ends up reinforcing our world view rather than expanding it.

There are several reasons for this behavior:

- Consensual validation: When we meet people who share similar attitudes, it makes us feel more confident about our world view. For example, if you love jazz music, meeting a fellow jazz lover confirms that your love of jazz is OK and maybe even virtuous.

- Cognitive evaluation: We naturally form positive or negative impressions of other people by generalizing from the information we acquire through experience or absorption. When a person has common interests with us, we assume that we must also share other positive characteristics with that person.

- Certainty of being liked: We assume that someone who shares common interests and viewpoints will probably like us. In turn, we tend to like people if we think they like us.

- Preference for enjoyable interactions: It is just more fun to hang out with someone when you have a lot in common.

- Opportunity for self-expansion: We benefit from new knowledge and experiences as the direct result of spending time with someone else. Oddly, people seeking self-expansion will gravitate toward people who are similar to them, even though a person with dissimilar perspectives would likely provide greater opportunities for self-expansion.

Listen to 15 minutes of news on a network that represents viewpoints contrary to yours.

- How did you feel while listening to a contrary opinion?

- Did you find yourself responding, such as thinking of rebuttals to contradict the information you were hearing?

- Did you learn something new?

The same behaviors influence how we listen to music. Music presents an artifact with many contextual facets. Some people listen to music for entertainment value. Others listen to find meaning in either the music or lyrics, or both. Very often, we attach meanings to music depending on where we were or what was happening when we heard it. Composers will have an inspiration or recall their personal experiences when creating music. Therefore, when analyzing music, it is important to consider the context that includes our personal response, the composer’s motivation, and perhaps outside influences, such as historical events or political movements.

There are fundamental questions we can ask regardless of musical genre:

- When did the artist compose the music?

- How does the genre of music impact its meaning?

- Does the tempo make us feel a certain way, such as sad, energized, relaxed, or irritated? How about the lyrics?

- Who do you think the music was written for? The musician? The listener?

- What do you think is the message is? Is meaning fluid or changeable?

- Does your musical taste change over time? As you get older? Due to events in your life?

Modern Song Lyrics

The two examples in this exercise present music artifacts from very different genres. The first is “ Blurred Lines ,” a song written by Pharell Williams and Robin Thicke. Released on March 26th, 2013, it was immediately involved in a legal dispute. Marvin Gaye’s family sued on the grounds that the song was “ noticeably ripped off ” from Marvin Gaye’s song “ Got To Give It Up .” The plaintiffs won their case and were awarded $5.3 million dollars in damages and 50% of royalties from future sales.

Furthermore, the song was criticized for promoting rape culture . Critics said the “blurred lines” in the title and lyrics were an assault on someone’s right to control sexual consent and the song’s message promoted the objectification of women as sexual objects.

Here are the song lyrics :

I hate these blurred lines I know you want it I hate them lines I know you want it I hate them lines I know you want it But you’re a good girl The way you grab me Must wanna get nasty Go ahead, get at me

- After reading the lyrics, do you think the song is controversial?

- After watching the video clip, does the meaning of the song change for you?

The song faced further controversy when Miley Cyrus joined Robin Thicke on stage at the 2013 MTV Video Music Awards. Cyrus performed twerking dance moves in close contact with Thicke and made sexual gestures using a foam finger. Her dance performance was regarded as an endorsement of the song’s message. (Time marker 04:10)

Credit: Robin Thicke, Miley Cyrus. “Miley Cyrus VMA 2013 with Robin Thicke SHOCKED.” MTV Video Music Awards 2013. Juan Manuel Cruz . YouTube. YouTube. Fair Use of worldwide, non-exclusive, royalty-free license to access content. https://youtu.be/LfcvmABhmxs.

Classical Instrumental Music

https://soundcloud.com/chicagosymphony/beethoven-symphony-no-6-2

Credit: Chicago Symphony Orchestra. Neeme Järvi, conductor. “ Beethoven Symphony No. 6 in F Major, Op. 68 .” SoundCloud. Fair Use of limited, personal, non-exclusive, revocable, non-assignable and non-transferable right and license to use the Platform to view Content. https://soundcloud.com/chicagosymphony/beethoven-symphony-no-6-2.

A very different example of a musical artifact is Ludwig van Beethoven’s Symphony No. 6 , written in 1808. (Making it a slightly older piece than “Blurred Lines.”). Historical context is important for analyzing the message in Beethoven’s composition. For example, what made No. 6 different from his other symphonies? A clue resides in the title Beethoven gave to this piece of music, Pastoral Symphony . According to the Merriam-Webster Dictionary, pastoral means “of, relating to, or composed of shepherds or herdsmen.” This suggests an agricultural theme. This is one of only two symphonies titled by the composer, rather than someone else. Beethoven had a lifelong appreciation of nature and frequently took walks in the countryside. For the premiere, he described this composition as having “ more an expression of feeling than painting .”

Listen to Beethoven’s Symphony No. 6 and pay attention to how the music makes you feel.

- How does the music affect your mood?

- What images appear in your mind as you listen?

- Can you interpret a message conveyed in the music despite there being no lyrics?

Try practicing your analytical listening skills on other instrumental pieces, such as the movie score to Fantasia , Barbie and the Magic of Pegasus , or The Lord of the Rings .

As you move through this book, you may discover information that is already familiar to you. Those cases are an opportunity to put on your critical and creative thinking cap and use it to reflect on your existing world views and values. Observe, and then, ask yourself lots of questions!

- Does your gender, race, sexuality, socio-economic status inform your interpretation of an artifact?

- What was happening historically when you read, listened to, or observed the artifact?

- Are (or were) there external circumstances, such as laws or events, that may have informed your interpretation of an artifact?

- Do you have acquired knowledge that helps deepen your appreciation or understanding of an artifact?

- Do you agree or disagree with an artist or creator’s message? If you disagree, can you appreciate why they felt compelled to create their message?

Remember, these questions are not intended to force you to shift your ideology. However, they do require you to consider how your personal perspective affects your interpretation of artifacts. And hopefully, these questions will encourage you to look at things from a different perspective than the one you are used to using.

The examples, questions, and descriptions in this book are designed to help teach you to:

- See and interpret patterns in people’s behavior.

- View situations from a variety of different perspectives.

- Realize that there may not be definitive answers to questions that arise from the human experience.

For our last example, use your critical and creative thinking skills to reflect on the following quote by Lawrence Wright :

“We prefer an ordered world, regular patterns, familiar forms, and when flaws or distortions occur, provided they are not too gross, our mind’s eye tidies them up. We see what we want or expect to see.”

- Do you agree with Wright? Do you prefer to categorize contemporary and historical events so they fit in with your world view?

- If you disagree, in what way?

- Is it possible that you could be misinterpreting information? Is it possible you do not have possession of all the facts?

- Do you operate in a clearly defined narrative within a clearly defined paradigm?

- Could you possibly change your mind?

The Human Experience: From Human Being to Human Doing Copyright © 2020, Edition 1 by Claire Peterson is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Mythology and Humanities in the Ancient World Delahoyde & Hughes CRITICAL THINKING ABOUT THE HUMANITIES Washington State University is currently taking an impressive lead in finding and fine-tuning ways to improve critical thinking skills. The WSU Critical Thinking Rubric provides a vocabulary for identifying many of the elusive features that teachers seek in their students' work and classroom contributions. The developers of this rubric emphasize the flexibility of it as a tool and encourage teachers to adapt it freely -- liberally, as it were -- to suit their own courses and/or assignments. We think it logical for humanities teachers to consider carefully the rubric's seven components, or subsets thereof, in terms of sequencing. 1) Identifying and summarizing the problem/question at issue (and/or the source's position). This does seem basic, which is not saying that it's a cinch. Students, even teachers, are apt to approach ancient works as if there are no ongoing debates about living issues embedded in the texts and material. A student's "report" on the Greek gods in the pantheon does not reach even this first rung of critical thinking. Wrangling with the notion of the interventions of particular anthropomorphic gods in the Iliad lends itself better to being cast as a problem or question.

2) Identifying and presenting the student's own perspective and position as it is important to the analysis of the issue.

Teachers in many disciplines who have adapted the entire rubric, as a sequence, to their courses have relocated this step to a place much later in the schematic. In certain assignments, and if one reductively translates "perspective" as "opinion," this component may not even be relevant. But in the humanities, we are often at pains to explain to students that somewhere between the dry, probably pointless reporting of factoids and an editorial spewing of their "opinions" comes what we really seek -- their "perspective" -- that is, a well-articulated indication that they have brought some sophisticated worldview of their own to the subject, or that the subject has contributed somehow to the development of that worldview. We have read, for example, many term papers that are impressively researched, superbly organized, excellently written, and utterly pointless. They fall dead because the conclusion merely concludes and readers are left asking "so what?" Indeed, even within the wording of this component of the rubric, one might take issue with the blurring of the terms "perspective" and "position." Someone with a ferocious "position" on an issue may desperately need some "perspective"! So, consider the terms you want to emphasize and consider relocating this component of the rubric before or after what is listed as #6: context.

3) Identifies and considers OTHER salient perspectives and positions that are important to the analysis of the issue.

If there is no awareness that multiple angles or possibilities are inherent in the subject, then it's likely that the student isn't conceptualizing the subject as a problem or question to begin with. Identifying and considering other perspectives and positions means more than the usual academic procedure; that is, the student reads secondary sources or even engages in primary research and applies this information to the topic / problem / question in meaningful ways, which includes generating an argumentative or expository text with a thesis. However, identifying and considering the perspectives of the "Other" has its own set of difficulties and levels of comprehension and interpretation and may be more of a bottleneck than current research statistics indicate. As a vital component of what we do in the humanities, teachers need to clarify the ways this section of the rubric encourages "critical thinking" beyond the standard procedures of secondary and primary research. Considering other perspective must include the process of consciousness or even soul-making that might rightfully be part of what we call the mental discipline of de-centering. This may sound entirely non-profit liberal, but the application can be worked out in specific pedagogical performances in the classroom. Cultural receptivity: In this context, Critical Thinking begins with fostering a willingness to consider seeing the world from another foreign or otherwise remote perspective, especially difficult at times given the way we depend on our facts and figures, the virtuosi of our knowledge, memory, authority, and arrogance. This area nevertheless necessarily includes an affinity for suspending what we know in order to imagine (with a degree of verisimilitude) what is quite literally and physically beyond our experience, culture, ethnicity, religion, gender, and so on. The pedagogical problem begins with a distinct treatise: we can only know what we have experienced. A racist male is not going to denounce his racism by merely researching the history of oppression in America or by reading Richard Wright's Native Son . Obviously educators hope that this person would indeed become less inclined toward racism by doing the above, but getting students to walk a mile in another person's shoes creates a complexity of puzzles and often requires a teaching miracle. For instance, when considering foreign perspectives are we not almost immediately immersed in a kind of cultural or otherwise voyeurism? Or worse yet hamstrung by our own ideological hierarchies which undermine or counter our attempts to achieve genuine empathy and therefore representation of the other? And in some or most cases, isn't gathering other perspectives (in an academic context) about pointing out where these "other perspectives" are wrong or askew? Certainly we also face the very syntax of the English language itself where the subject of the sentence always does something to the predicate. The tantalizing and stereotypical verbs within the sentence diagram often breed acquisition and assault, sometimes with sudden and surprising violence. We need real salience of interpretation. The central accomplishment is to overcome the tendency to lampoon, vivify, or praise the author's perspective strictly from the canvas of our own dramatic self-portrait. This category of the rubric invites precarious ladder-climbing in the classroom. We can feel the ladder sway and the boughs bend. For instance, some female students will read the Iliad in a different way that some male students. As teachesr, we can try to underscore differences based on gender ( at least in the ancient world) through text selection by asking students to also read The Trojan Women by Euripides, which adds to the Homeric drama and certainly identifies and considers other perspectives. The agenda here however is not to generate feminine / masculine polarities or emphasize a point of view that sees women as the grass that gets trampled when the elephants fight. Or to convey that the narratives of the ancient world characterize women as the trophies or spoils of war, vital to the male heroic code. We desire something more; identifying other perspectives is easy; considering other perspectives is more complex. Remember that we are speaking only of one verse of the rubric here, a part that acts in symbiotic relationship with the rubric as a whole and involves a redemptive vision that shifts the inevitable to the creative. As educators we must ask students to explore the incongruous terrain beyond polarities. Identifying and considering other perspectives requires an unprocessed even exotic medium to give it meaning and stimulate the mind's own processes. And whether we seek or shun foreign perspectives, conceit in all its forms is damn near inescapable. At least this awareness alone should shape our capacity for rearranging the way we teach in the humanities.

4) Identifies and assesses the key assumptions .

This means that the student is perceiving the subject somewhat three-dimensionally, or at least reading between the lines. Questioning the assumption that the Greek audience of the Iliad would in all cases have understood the intervening gods as literal characters is a good sign of the critical thinking process. The notion of ethics is curiously included within the rubric wording about assumptions. Are some disciplines or topics void of ethical assumptions? Are Newton's Laws up for ethical analysis? We begin by identifying methods of inquiry appropriate, in particular, to a specific discipline in order to achieve pedagogical goals. In the humanities, we proceed slowly for we suspect that even gravity and its laws will wax ethical at some point in the history and future of the human endeavor. Our fundamental approach to assumptions involves equality or rather thinking critically about how assumptions may perpetuate inequality. We all participate in what Alexis de Tocqueville called the Equality of Condition, regardless of our discipline. In this case, critical thinking is a social force.

5) Identifies and assesses the quality of supporting data/evidence and provides additional data/evidence related to the issue.

The distinction here is between merely regurgitating others' work or reporting from research and truly incorporating the valuable findings.

6) Identifies and considers the influence of the context on the issue.

An appendix to the Critical Thinking Rubric lists possible contexts (cultural, political, ethical, etc.) for consideration. That we still think in terms of ephemeral forces taking over ("Something told me I should go in there"; "The paper suddenly seemed to write itself!") might serve as a context for the issue of anthropomorphic gods intervening at the right times in the Iliad .

7) Identifies and assesses conclusions, implications and consequences .

The rubric's developers admit that it contains a bias towards teachers of writing. This item is difficult to envision outside of some form of writing, where students ideally have moved beyond concluding with simply a reassertion of the thesis, or a limp summary of the preceding discussion. Here too readers are asking, "So what?" and the best signs of critical thinking are those indications that the student has activated the subject by showing its importance. Not every assignment, nor even every class, needs to demand that students succeed in demonstrating all the above skills. Rather, the Critical Thinking Rubric is designed to lend individual teachers some framework and/or some language with which to formulate their assignments and classes, and to help them pinpoint some ways to evaluate not student writing strictly, but student thinking. Texts and materials in the Humanities exist not to be "appreciated" reverentially, but rather to encourage critical thinking themselves. We think Homer, Thucydides, Socrates, Euripides, Ovid, and the rest of the gang would agree.

--Michael Delahoyde --Collin Hughes

- Future Students

- Parents and Families

Center for the Humanities

What are the humanities.

The humanities are the stories, the ideas, and the words that help us understand our lives and our world. They introduce us to people we have never met, places we have never visited, and ideas that may never have crossed our minds. By showing how others have lived and thought about life, the humanities help us decide what is important and what we can do to make our own lives and the lives of others better. By connecting us with other people, the humanities point the way to answers about what is ethical and what is true to our diverse heritage, traditions, and history. They help us address the challenges we face together as families, communities, and nations. As fields of study, the humanities emphasize analysis and exchange of ideas and may be interdisciplinary.

- History and Art History study human, social, political, and cultural developments, as well as aspects of the Social Sciences that use historical or philosophical approaches.

- Literature, Languages, and Linguistics, as well as certain approaches to Journalism and Communication Studies, that explore how we communicate with each other, and how our ideas and thoughts on the human experience are expressed and interpreted.

- Philosophy, Ethics, and Comparative Religion, which consider ideas about the meaning of life and the reasons for our thoughts and actions.

- Jurisprudence, which examines the values and principles which inform our laws.

- Critical and theoretical approaches to and practices of the Arts that explore historical or philosophical questions and reflect upon the creative process.

The humanities should not be confused with “humanism,” a specific philosophical belief, nor with “humanitarianism,” the concern for charitable works and social reform.

- Divisions and Offices

- Grants Search

- Manage Your Award

- NEH's Application Review Process

- Professional Development

- Grantee Communications Toolkit

- NEH Virtual Grant Workshops

- Awards & Honors

- American Tapestry

- Humanities Magazine

- NEH Resources for Native Communities

- Search Our Work

- Office of Communications

- Office of Congressional Affairs

- Office of Data and Evaluation

- Budget / Performance

- Contact NEH

- Equal Employment Opportunity

- Human Resources

- Information Quality

- National Council on the Humanities

- Office of the Inspector General

- Privacy Program

- State and Jurisdictional Humanities Councils

- Office of the Chair

- NEH-DOI Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative Partnership

- NEH Equity Action Plan

- GovDelivery

Martha C. Nussbaum Talks About the Humanities, Mythmaking, and International Development

The 2017 jefferson lecturer in conversation with neh chairman william d. adams.

Martha C. Nussbaum, 2017 Jefferson Lecturer in the Humanities

—Robert Tolchin Photography

On a cold January day in Chicago, Martha C. Nussbaum, the well-lauded philosopher and 2017 Jefferson Lecturer, spoke with NEH Chairman William Adams about the advantages of a humanities education, her passion for ancient Greek and Roman literature, her work at the University of Chicago law school, and her contributions to the field of international development. Several other topics were broached, and still many others could have been added to the agenda, given the extraordinary range of Nussbaum’s thought, which flows mightily across disciplines to better understand the wellsprings of human flourishing and what obstacles stand in the way.

Philosopher John Rawls, author of A Theory of Justice , strongly encouraged Martha Nussbaum to write for a broader public.

—Frederic REGLAIN / Getty Images

When Martha Nussbaum says “we” and the topic is the human capabilities approach, she is usually referring to Amartya Sen, the Nobel Prize-winning economist, with whom she developed this multifaceted standard for measuring national well-being.

—Agence Opale / Alamy Stock Photo

WILLIAM D. ADAMS: Your book Not for Profit made the case for the importance of the humanities in American democratic life. Have things changed substantially since it was published in 2010?

MARTHA C. NUSSBA UM : Data on humanities majors is still a source of concern, but there’s been a big increase in total enrollments in humanities courses in community colleges. And in adult education, too, there’s been a huge upsurge. The preface to the new edition of my book gives data and sources on all this.

We are lucky in the United States to have our liberal arts system. In most countries, if you go to university, you have to decide for all English literature or no literature, all philosophy or no philosophy. But we have a system that is one part general education and one part specialization. If your parents say you’ve got to major in computer science, you can do that. But you can also take general education courses in the humanities, and usually you have to.

ADAMS: Yet I’ve sensed some weakening of our resolve to support the liberal arts. What should we be doing to reinforce your way of thinking about higher education?

NUSSBAUM: There are three points you can make. The one I think should be front and center is that the humanities prepare students to be good citizens and help them understand a complicated, interlocking world. The humanities teach us critical thinking, how to analyze arguments, and how to imagine life from the point of view of someone unlike yourself.

Secondly, we need to emphasize their economic value. Business leaders love the humanities because they know that to innovate you need more than rote knowledge. You need a trained imagination.

Singapore and China, which don’t want to encourage democratic citizenship, are expanding their humanities curricula. These reforms are all about developing a culture of innovation and entrepreneurship.

But the humanities also teach us the value, even for business, of criticism and dissent. When there’s a culture of going along to get along, where whistleblowers are discouraged, bad things happen and businesses implode.

The third point is about the search for meaning. Life is about more than earning a living, and if you’re not in the habit of thinking about it, you can end up middle-aged or even older and shocked to realize that your life seems empty.

ADAMS: Some people who care about the humanities worry about various trends, such as obscure methodologies and language that is difficult to read. Where do you come down on this issue?

NUSSBAUM: I do think there’s a lot of bad writing, and I worry about that in philosophy. I worry about it even more in literary studies, but I wouldn’t blame it on any one methodology.

When a profession is protected by academic freedom and tenure, it tends to turn inward. To a large extent that’s good. The great philosophers of the past who wrote so beautifully—Rousseau, John Stuart Mill—had to write beautifully because they had to sell their work to journals. They had to sell books to the general public because they could not hold positions in universities. Mill was an atheist, and, therefore, could not hold a position in a university.

It’s a good thing that we’re protected by tenure and academic freedom, but we should realize that it creates a risk of getting cut off. Scholars should write, at least sometimes, for the general public. But if I tell my graduate students to write for the general public, where are they going to publish? There are fewer and fewer media outlets for such writing. Dissent is one that they could still write for, The Nation , Boston Review I love. But there are only a few. There are other countries where general media take a much greater interest in philosophy: the Netherlands, Italy, Germany.

ADAMS: You’re a philosopher, so I want to ask, Should we be doing more work in political philosophy that relates to contemporary democracy?

NUSSBAUM: There was a time, before I was in graduate school, when political philosophy pretty much ceased to exist. The positivists thought there were only two things you could do: conceptual analysis or empirical investigation. Any kind of political theory or even ethical theory was nonsense. But John Rawls exploded that idea, both by writing great political theory and by arguing that, in fact, it wasn’t nonsense. I was part of that ferment, which included all kinds of arguments between Rawls and Robert Nozick, and Hilary Putnam. And Stanley Cavell.