How to write an abstract for a research paper

Read about three elements to include in your research paper abstract and some tips for making yours stand out

Ankitha Shetty

Created in partnership with

You may also like

Popular resources

.css-1txxx8u{overflow:hidden;max-height:81px;text-indent:0px;} The secrets to success as a provost

Using non verbal cues to build rapport with students, emotionally challenging research and researcher well-being, augmenting the doctoral thesis in preparation for a viva, how hard can it be testing ai detection tools.

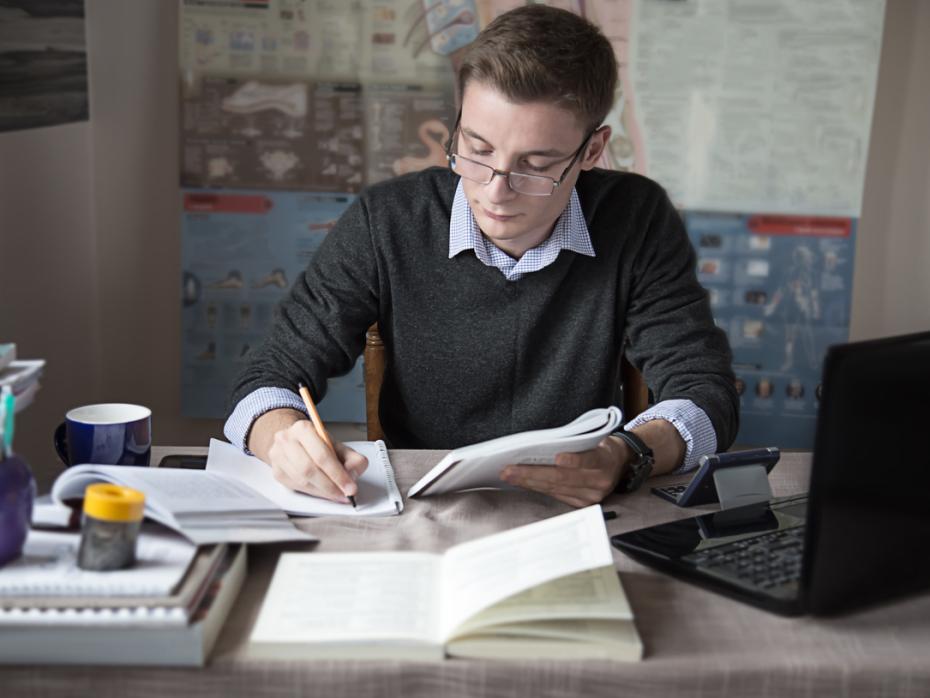

Writing an abstract might not seem to be at the top of your list of priorities when writing your PhD dissertation , but it’s probably the first thing a reader will see when they encounter your research, so it’s worth putting the effort in to get it right. Here are some ways to make it sing.

What is an abstract?

An abstract is a concise overview of an extensive piece of research work such as a thesis, dissertation or research paper. Depending on the discipline, it usually contains the purpose of the research, the methodologies employed and the conclusions derived. Abstracts typically range from 500 to 800 words and appear on a separate page after the title page and acknowledgements, but preceding the table of contents. Although it might be tempting to start your thesis by drafting your abstract, I advise postponing until you’ve completed a first draft so that you ensure you cover all topics discussed in your thesis.

What to include in your abstract

Purpose of the study.

Begin your abstract by concisely defining the problems your study addresses or outlining the gaps in knowledge it fills. It should provide the reader with new and useful information regarding your research in the present or past tense. Use verbs such as “test”, “evaluate” and “analyse” to make the research objective specific, measurable, attainable and time-bound. Avoid providing detailed background information and personal opinions at this stage.

In this part of your abstract, explain how you designed and conducted your research and how it addresses your research questions in the past tense. The aim here is to give the reader a prompt insight into your approach, not to evaluate challenges, validity and reliability. Highlight the samples you used and the data collection and analysis tools you employed.

- Campus resource collection: What I wish I’d known about academia

- Campus resource collection: Resources on academic writing

- What is your academic writing temperament?

Results and conclusion

Summarise and highlight the most significant findings that will allow the reader to understand the conclusions in the present or past tense. At the end of your abstract, the reader ought to have a firm grasp of the main argument. If the motive of the research is to resolve a real-world issue, you can include practical implications and suggestions in the findings. Briefly offer future recommendations for further research, if applicable.

When writing your abstract, imagine who might read your research; a curious reader, not necessarily an expert in the field, expects the information to be accessible and not overly complex.

Tips on how to write an abstract for a research paper

- Explain why you chose this area of research and the significance of the study

- Ask yourself “why?” “what?” “how?” and “so what?” and use the abstract to address these questions.

- Highlight the novelty of your research

- Explain how your research adds to the existing body of literature on the topic

- Explain your research design, highlighting elements such as approach, demographics, sampling and geographical information

- Explain how your research is relevant and significant

- Address practical implications to potential interested parties – for example, any issues relating to policy

- Avoid technical jargon, generalised statements and vague claims that make your work difficult to read

- Avoid acronyms and abbreviations at this stage. Add them into the introduction instead

- Provide concise, consistent and accurate details

- Adhere to the word count limit specified in your instructions

- Include essential keywords for search engine optimisation

- There’s no need to include references at this stage

- Never copy and paste content directly from elsewhere in the thesis; use new vocabulary and phrases to differentiate the abstract from the rest of the text.

These tips will help to make the abstract writing process smoother, allowing you to make a good first impression on whoever comes across your work when you’re ready to send it out into the world.

Ankitha Shetty is an assistant professor (senior scale) at the department of commerce and a coordinator at the Centre for Doctoral Studies at Manipal Academy of Higher Education, India.

If you would like advice and insight from academics and university staff delivered direct to your inbox each week, sign up for the Campus newsletter.

The secrets to success as a provost

Emotions and learning: what role do emotions play in how and why students learn, the podcast: bringing an outsider’s eye to primary sources, a diy guide to starting your own journal, formative, summative or diagnostic assessment a guide, harnessing the power of data to drive student success.

Register for free

and unlock a host of features on the THE site

How to Write an Abstract for Your Paper

An abstract is a self-contained summary of a larger work, such as research and scientific papers or general academic papers . Usually situated at the beginning of such works, the abstract is meant to “preview” the bigger document. This helps readers and other researchers find what they’re looking for and understand the magnitude of what’s discussed.

Like the trailer for a movie, an abstract can determine whether or not someone becomes interested in your work. Aside from enticing readers, abstracts are also useful organizational tools that help other researchers and academics find papers relevant to their work.

Because of their specific requirements, it’s best to know a little about how to write an abstract before doing it. This guide explains the basics of writing an abstract for beginners, including what to put in them and some expert tips on writing them.

Give your papers extra polish Grammarly helps you improve your academic writing Write with Grammarly

What’s the purpose of an abstract?

The main purpose of an abstract is to help people decide whether or not to read the entire academic paper. After all, titles can be misleading and don’t get into specifics like methodology or results. Imagine paying for and downloading a hundred-page dissertation on what you believe is relevant to your research on the Caucasus region—only to find out it’s about the other Georgia.

Likewise, abstracts can encourage financial support for grant proposals and fundraising. If you lack the funding for your research, your proposal abstract would outline the costs and benefits of your project. This way, potential investors could make an informed decision, or jump to the relevant section of your proposal to see the details.

Abstracts are also incredibly useful for indexing. They make it easier for researchers to find precisely what they need without wasting time skimming actual papers. And because abstracts sometimes touch on the results of a paper, researchers and students can see right away if the paper can be used as evidence or a citation to support their own theses.

Nowadays, abstracts are also important for search engine optimization (SEO)—namely, for getting digital copies of your paper to appear in search engine results. If someone Googles the words used in your abstract, the link to your paper will appear higher in the search results, making it more likely to get clicks.

How long should an abstract be?

Abstracts are typically 100–250 words and comprise one or two paragraphs . However, more complex papers require more complex abstracts, so you may need to stretch it out to cover everything. It’s not uncommon to see abstracts that fill an entire page, especially in advanced scientific works.

When do you need to write an abstract?

Abstracts are only for lengthy, often complicated texts, as with scientific and research papers. Similar academic papers—including doctorate dissertations, master’s theses, or elaborate literary criticisms —may also demand them as well. If you’re learning how to write a thesis paper for college , you’ll want to know how to write an abstract, too.

Specifically, most scientific journals and grant proposals require an abstract for submissions. Conference papers often involve them as well, as do book proposals and other fundraising endeavors.

However, most writing, in particular casual and creative writing, doesn’t need an abstract.

Types of abstracts

There are two main types of abstracts: informative and descriptive. Most abstracts fall into the informative category, with descriptive abstracts reserved for less formal papers.

Informative abstracts

Informative abstracts discuss all the need-to-know details of your paper: purpose, method, scope, results, and conclusion. They’re the go-to format for scientific and research papers.

Informative abstracts attempt to outline the entire paper without going into specifics. They’re written for quick reference, favor efficiency over style, and tend to lack personality.

Descriptive abstracts

Descriptive abstracts are a little more personable and focus more on enticing readers. They don’t care as much for data and details, and instead read more like overviews that don’t give too much away. Think of descriptive abstracts like synopses on the back of a book.

Because they don’t delve too deep, descriptive abstracts are shorter than informative abstracts, closer to 100 words, and in a single paragraph. In particular, they don’t cover areas like results or conclusions — you have to read the paper to satisfy your curiosity.

Since they’re so informal, descriptive abstracts are more at home in artistic criticisms and entertaining papers than in scientific articles.

What to include in an abstract

As part of a formal document, informative abstracts adhere to more scientific and data-based structures. Like the paper itself, abstracts should include all of the IMRaD elements: Introduction , Methods , Results , and Discussion .

This handy acronym is a great way to remember what parts to include in your abstract. There are some other areas you might need as well, which we also explain at the end.

Introduction

The beginning of your abstract should provide a broad overview of the entire project, just like the thesis statement. You can also use this section of your abstract to write out your hypothesis or research question.

In the one or two sentences at the top, you want to disclose the purpose of your paper, such as what problem it attempts to solve and why the reader should be interested. You’ll also need to explain the context around it, including any historical references.

This section covers the methodology of your research, or how you collected the data. This is crucial for verifying the credibility of your paper — abstracts with no methodology or suspicious methods won’t be taken seriously by the scientific community.

If you’re using original research, you should disclose which analytical methods you used to collect your data, including descriptions of instruments, software, or participants. If you’re expounding on previous data, this is a good place to cite which data and from where to avoid plagiarism .

For informative abstracts, it’s okay to “give away the ending.” In one or two sentences, summarize the results of your paper and the conclusive outcome. Remember that the goal of most abstracts is to inform, not entice, so mentioning your results here can help others better classify and categorize your paper.

This is often the biggest section of your abstract. It involves most of the concrete details surrounding your paper, so don’t be afraid to give it an extra sentence or two compared to the others.

The discussion section explains the ultimate conclusion and its ramifications. Based on the data and examination, what can we take away from this paper? The discussion section often goes beyond the scope of the project itself, including the implications of the research or what it adds to its field as a whole.

Other inclusions

Aside from the IMRaD aspects, your abstract may require some of the following areas:

- Keywords — Like hashtags for research papers, keywords list out the topics discussed in your paper so interested people can find it more easily, especially with online formats. The APA format (explained below) has specific requirements for listing keywords, so double-check there before listing yours.

- Ethical concerns — If your research deals with ethically gray areas, i.e., testing on animals, you may want to point out any concerns here, or issue reassurances.

- Consequences — If your research disproves or challenges a popular theory or belief, it’s good to mention that in the abstract — especially if you have new evidence to back it up.

- Conflicts of Interest/Disclosures — Although different forums have different rules on disclosing conflicts of interests, it’s generally best to mention them in your abstract. For example, maybe you received funding from a biased party.

If you’re ever in doubt about what to include in your abstract, just remember that it should act as a succinct summary of your entire paper. Include all the relevant points, but only the highlights.

Abstract formats

In general, abstracts are pretty uniform since they’re exclusive to formal documents. That said, there are a couple of technical formats you should be aware of.

APA format

The American Psychological Association (APA) has specific guidelines for their papers in the interest of consistency. Here’s what the 7th edition Publication Manual has to say about formatting abstracts:

- Double-space your text.

- Set page margins at 1 inch (2.54 cm).

- Write the word “Abstract” at the top of the page, centered and in a bold font.

- Don’t indent the first line.

- Keep your abstract under 250 words.

- Include a running header and page numbers on all pages, including the abstract.

Abstract keywords have their own particular guidelines as well:

- Label the section as “ Keywords: ” with italics.

- Indent the first line at 0.5 inches, but leave subsequent lines as is.

- Write your keywords on the same line as the label.

- Use lower-case letters.

- Use commas, but not conjunctions.

Structured abstracts

Structured abstracts are a relatively new format for scientific papers, originating in the late 1980s. Basically, you just separate your abstract into smaller subsections — typically based on the IMRaD categories — and label them accordingly.

The idea is to enhance scannability; for example, if readers are only interested in the methodology, they can skip right to the methodology. The actual writing of structured abstracts, though, is more-or-less the same as traditional ones.

Unstructured abstracts are still the convention, though, so double-check beforehand to see which one is preferred.

3 expert tips for writing abstracts

1 autonomous works.

Abstracts are meant to be self-contained, autonomous works. They should act as standalone documents, often with a beginning, middle, and end. The thinking is that, even if you never read the actual paper, you’ll still understand the entire scope of the project just from the abstract.

Keep that in mind when you write your abstract: it should be a microcosm of the entire piece, with all the key points, but none of the details.

2 Write the abstract last

Because the abstract comes first, it’s tempting to write it first. However, writing the abstract at the end is more effective since you have a better understanding of what is actually in your paper. You’ll also discover new implications as you write, and perhaps even shift the structure a bit. In any event, you’re better prepared to write the abstract once the main paper is completed.

3 Abstracts are not introductions

A common misconception is to write your abstract like an introduction — after all, it’s the first section of your paper. However, abstracts follow a different set of guidelines, so don’t make this mistake.

Abstracts are summaries, designed to encapsulate the findings of your paper and assist with organization and searchability. A good abstract includes background information and context, not to mention results and conclusions. Abstracts are also self-contained, and can be read independently of the rest of the paper.

Introductions, by contrast, serve to gradually bring the reader up to speed on the topic. Their goals are less clinical and more personable, with room to elaborate and build anticipation. Introductions are also an integral part of the paper, and feel incomplete if read independently.

Give your formal writing the My Fair Lady treatment

Formal papers — the kind that requires abstracts — need formal language. But for most of us, that means changing the way we communicate or even think. You may want to consider the My Fair Lady treatment, which is to say, having a skilled mentor coach what you say.

Grammarly Premium now offers a new Set Goals feature that helps you tailor your language to your audience or intention. All you have to do is set the goals of a particular piece of writing and Grammarly will customize your feedback accordingly. For example, you can select the knowledge level of your readers, the formality of the tone, and the domain or field you’re writing for (i.e., academic, creative, business, etc.). You can even set a tone to sound more analytical or respectful!

Here’s a tip: Grammarly’s Citation Generator ensures your essays have flawless citations and no plagiarism. Try it for citing abstracts in Chicago , MLA , and APA styles.

My Timetable

LOG IN to show content

My Quick Links

How to Write an Abstract

An abstract provides the reader with a summary of your project. Depending on the kind of project, abstracts can take on different forms. This can include an abstract for a(n):

- academic journal article

- conference proposal

- Master's thesis/PhD dissertation

- Master’s thesis/PhD dissertation proposal (i.e., a research proposal)

- essay in your course

Abstracts vary in length. For journal articles, abstracts are often between 150-250 words. For conferences and dissertations, however, abstracts can be longer (up to 500 words). Always follow the guidelines provided.

The Purpose and Audience of an Abstract

Regardless of the kind of abstract you are writing, it should entice the reader’s interest. Each of these abstracts has a different purpose and audience.

Journal Article Abstracts

For a journal article, the abstract helps the reader determine whether to read the full paper. When writing an abstract for a journal article, it is important to consider the nature of the journal. For example, is it a specialized or an interdisciplinary journal? When writing for a non-specialized audience, it is best to avoid technical language in the abstract. Consider your language use when writing for a journal in a Canadian context versus an international context, too. Since abstracts and keywords for journal articles are used by search engines, be strategic in the language you use to draw readers to your work.

Conference Abstracts

The conference abstract, meanwhile, helps the attendee decide whether to attend the session. When preparing to write a conference abstract, consider the kind of conference: is it a research-oriented or practice-oriented conference? Also consider the kind of conference session. Are you proposing to share research, facilitate a roundtable, develop a workshop? This will shape the direction of the abstract. Also consider the theme of the conference to ensure that your proposal is in alignment.

Thesis and Dissertation Abstracts

The abstract for a Master’s thesis or PhD dissertation, including a proposal, helps the reader to understand the purpose and scope of the project. Since a thesis or dissertation is a large work, the abstract frames the overarching structure for the reader and reveals the thread that unites the project. It can also help orient the reader to particular points of interest.

Course Essay Abstracts

An abstract for an essay in a course provides the reader an overview of the project.

What to Include in an Abstract

Depending on the academic discipline, the abstract includes different kinds of information.

Arts and Humanities Abstracts

Abstracts in the arts and humanities disciplines often include one to two sentences about the following:

- Introduction: Includes the topic and the problem or debate being explored

- Thesis: Gives a summary of the overarching argument

- Theoretical framework: Explains the theoretical background of the research

- Line of argumentation: Provides the actual reasoning in the argument

- Significance: Positions the importance of the study within a larger field of research

Natural and Social Sciences Abstracts

Meanwhile, abstracts in the natural and social sciences often include one to two sentences about the following:

- Introduction: Includes the topic, what we generally know about the topic, and what the research gap

- Objectives: Includes the purpose of the study, the research question(s), and/or the hypothesis

- Methodology: Provides a general overview of how the study was conducted

- Results: Highlights the most important finding(s) from the research

You may write an abstract for a research proposal that has not yet been conducted. In that case, you will not have information about the results. You should be clear in your framing of the abstract that the research is forthcoming. This could include using the future tense to speak about the methodology.

These are general guidelines. Given the wide range of abstracts, it’s important to tailor the information in an abstract considering the field, audience, and context.

Search for academic programs , residence , tours and events and more.

- Online Degrees

- Find your New Career

- Join for Free

How to Write and Publish a Scientific Paper (Project-Centered Course)

Taught in English

Some content may not be translated

Financial aid available

177,067 already enrolled

Gain insight into a topic and learn the fundamentals

Instructor: Mathis Plapp

Included with Coursera Plus

(2,553 reviews)

Details to know

Add to your LinkedIn profile

See how employees at top companies are mastering in-demand skills

Earn a career certificate

Add this credential to your LinkedIn profile, resume, or CV

Share it on social media and in your performance review

There are 4 modules in this course

What you will achieve:

In this project-based course, you will outline a complete scientific paper, choose an appropriate journal to which you'll submit the finished paper for publication, and prepare a checklist that will allow you to independently judge whether your paper is ready to submit. What you'll need to get started: This course is designed for students who have previous experience with academic research - you should be eager to adapt our writing and publishing advice to an existing personal project. If you just finished your graduate dissertation, just began your PhD, or are at a different stage of your academic journey or career and just want to publish your work, this course is for you. *About Project-Centered Courses: Project-Centered Courses are designed to help you complete a personally meaningful real-world project, with your instructor and a community of learners with similar goals providing guidance and suggestions along the way. By actively applying new concepts as you learn, you’ll master the course content more efficiently; you’ll also get a head start on using the skills you gain to make positive changes in your life and career. When you complete the course, you’ll have a finished project that you’ll be proud to use and share.

Understanding academia

In this section of the MOOC, you will learn what is necessary before writing a paper: the context in which the scientist is publishing. You will learn how to know your own community, through different exemples, and then we will present you how scientific journal and publication works. We will finish with a couple of ethical values that the academic world is sharing!

What's included

8 videos 4 readings 5 quizzes 2 discussion prompts

8 videos • Total 28 minutes

- Introduction by Mathis Plapp • 1 minute • Preview module

- Let me walk you through the course • 3 minutes

- French version of the class • 0 minutes

- Why is publishing important? • 3 minutes

- "KYC": Know Your Community • 4 minutes

- How journals work: the review process • 4 minutes

- Presentation of scientific journals • 4 minutes

- Ethical Guidelines • 5 minutes

4 readings • Total 40 minutes

- Teaching team • 10 minutes

- Breakthroughs! • 10 minutes

- Additional contents • 10 minutes

- Examples of guidelines • 10 minutes

5 quizzes • Total 150 minutes

- Why is publishing important? • 30 minutes

- Know your community • 30 minutes

- How journals work: the review process • 30 minutes

- Communication with the editorial board • 30 minutes

- Ethical Guidelines and intellectual property • 30 minutes

2 discussion prompts • Total 20 minutes

- Your thoughts • 10 minutes

- Compatibility between paper submission and editorial board • 10 minutes

Before writing: delimiting your scientific paper

A good paper do not loose focus throughout the entirety of its form. As such, we are going to give you a more detailed view on how to delimit your paper. We are going to lead you through your paper by taking a closer look at the paper definition which will ensure you don't loose focus. Then we will explain why the literature review is important and how to actually do it. And then we will guide you with advices as to how to find the so-what of your paper! This is important as research is all about so-what!

6 videos 1 reading 5 quizzes 4 discussion prompts

6 videos • Total 26 minutes

- Paper definition "KYP", Know Your Paper • 3 minutes • Preview module

- How to: the literature review 1/2: find a good literature review • 3 minutes

- How to: the literature review 2/2: construction of your own literature review • 6 minutes

- How to: the research design • 3 minutes

- How to: the gap • 4 minutes

- Presentation of Zotero: aggregate references • 4 minutes

1 reading • Total 10 minutes

- Books and tools • 10 minutes

- Literature Review • 30 minutes

- Main ideas • 30 minutes

- The Gap? • 30 minutes

- So, what? • 30 minutes

- Think about it • 30 minutes

4 discussion prompts • Total 40 minutes

- Compatibility between paper and journal • 10 minutes

- Understanding how the literature review is structured • 10 minutes

- Finding Useful References: Difficulties & Strategies for Success. • 10 minutes

- Comparing different research designs on the same subject • 10 minutes

Writing the paper: things you need to know

In this part of the MOOC, you will learn how to write your paper. In a first part, we will focus on the structure of the paper, and then you will be able to see how to use bibliographical tools such as zotero. Finally you will be required to write your own abstract and to do a peer review for the abstract of the others, as in real academic life!

5 videos 2 readings 2 quizzes 1 peer review 2 discussion prompts

5 videos • Total 27 minutes

- The structure of an academic paper • 7 minutes • Preview module

- On writing an academic paper, preliminary tips • 6 minutes

- How to: the bibliography • 3 minutes

- The abstract • 6 minutes

- Zotero: online features • 3 minutes

2 readings • Total 20 minutes

- Important readings before writing a paper • 10 minutes

- More detailed information on how to write your article • 10 minutes

2 quizzes • Total 60 minutes

- The bibliography • 30 minutes

- Please, try by yourself • 30 minutes

1 peer review • Total 60 minutes

- Peer reviewing of an abstract • 60 minutes

- Comparing different constructions of papers • 10 minutes

- Discussing abstracts • 10 minutes

After the writing: the check list

After writing the paper comes the time of reading your paper a few times in order to get everything perfect.In this section you will learn how to remove a lot of mistakes you might have been writing. In the end, you will have to build your own checklist corresponding to your own problems you want to avoid. After this, your article can be submitted and will hopefully be accepted!!

5 videos 3 readings 1 peer review 1 discussion prompt

5 videos • Total 36 minutes

- How to avoid being boring? • 5 minutes • Preview module

- The main mistakes to look for: format • 3 minutes

- 1. The researcher • 9 minutes

- 2. The editor • 13 minutes

- Constructing your checklist • 4 minutes

3 readings • Total 30 minutes

- Avoiding mistakes • 10 minutes

- Format and Writing Readings • 10 minutes

- Tips • 10 minutes

- Now it is your turn: the checking list • 60 minutes

1 discussion prompt • Total 10 minutes

- Several content worth taking a look at • 10 minutes

Instructor ratings

We asked all learners to give feedback on our instructors based on the quality of their teaching style.

École polytechnique combines research, teaching and innovation at the highest scientific and technological level worldwide to meet the challenges of the 21st century. At the forefront of French engineering schools for more than 200 years, its education promotes a culture of multidisciplinary scientific excellence, open in a strong humanist tradition.\n L’École polytechnique associe recherche, enseignement et innovation au meilleur niveau scientifique et technologique mondial pour répondre aux défis du XXIe siècle. En tête des écoles d’ingénieur françaises depuis plus de 200 ans, sa formation promeut une culture d’excellence scientifique pluridisciplinaire, ouverte dans une forte tradition humaniste.

Recommended if you're interested in Education

O.P. Jindal Global University

Introduction to Academic Writing

Stanford University

Writing in the Sciences

University of Cape Town

Research for Impact

University of London

Understanding Research Methods

Why people choose coursera for their career.

Learner reviews

Showing 3 of 2553

2,553 reviews

Reviewed on Mar 1, 2018

The course is well structured that guides a scholar to construct a research paper step by step in a steady and sure way. I would definitely recommend the course for new research scholars.

Reviewed on May 7, 2020

The course was really awesome... Some teachers's pronunciation accent was difficult to understand though the text written below the video helps me a-lot... Thanks to all teachers...

Reviewed on May 19, 2023

INDEED AN EXCELLENT COURSE I HAVE EVER ATTENDED AND I LIKE IT VERY MUCH.

TOO THE POINT AND EXACT ON THE TARGET. CONCISE BUT COMPREHENSIVE. KEEP IT UP AND KEEP MAINTAIN THE POSITION.

Open new doors with Coursera Plus

Unlimited access to 7,000+ world-class courses, hands-on projects, and job-ready certificate programs - all included in your subscription

Advance your career with an online degree

Earn a degree from world-class universities - 100% online

Join over 3,400 global companies that choose Coursera for Business

Upskill your employees to excel in the digital economy

Frequently asked questions

When will i have access to the lectures and assignments.

Access to lectures and assignments depends on your type of enrollment. If you take a course in audit mode, you will be able to see most course materials for free. To access graded assignments and to earn a Certificate, you will need to purchase the Certificate experience, during or after your audit. If you don't see the audit option:

The course may not offer an audit option. You can try a Free Trial instead, or apply for Financial Aid.

The course may offer 'Full Course, No Certificate' instead. This option lets you see all course materials, submit required assessments, and get a final grade. This also means that you will not be able to purchase a Certificate experience.

What will I get if I purchase the Certificate?

When you purchase a Certificate you get access to all course materials, including graded assignments. Upon completing the course, your electronic Certificate will be added to your Accomplishments page - from there, you can print your Certificate or add it to your LinkedIn profile. If you only want to read and view the course content, you can audit the course for free.

What is the refund policy?

You will be eligible for a full refund until two weeks after your payment date, or (for courses that have just launched) until two weeks after the first session of the course begins, whichever is later. You cannot receive a refund once you’ve earned a Course Certificate, even if you complete the course within the two-week refund period. See our full refund policy Opens in a new tab .

Is financial aid available?

Yes. In select learning programs, you can apply for financial aid or a scholarship if you can’t afford the enrollment fee. If fin aid or scholarship is available for your learning program selection, you’ll find a link to apply on the description page.

More questions

Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association, Seventh Edition (2020)

Table of Contents | Supplemental Resources | Introduction (PDF)

Official source for APA Style The Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association, Seventh Edition is the official source for APA Style.

Widely adopted With millions of copies sold worldwide in multiple languages, it is the style manual of choice for writers, researchers, editors, students, and educators in the social and behavioral sciences, natural sciences, nursing, communications, education, business, engineering, and other fields.

Authoritative and easy to use Known for its authoritative, easy-to-use reference and citation system, the Publication Manual also offers guidance on choosing the headings, tables, figures, language, and tone that will result in powerful, concise, and elegant scholarly communication.

Scholarly writing It guides users through the scholarly writing process—from the ethics of authorship to reporting research through publication.

- Spiral-Bound $44.99

- Paperback $31.99

- Hardcover $54.99

- Course adoption

|

|

|

|

It is an indispensable resource for students and professionals to achieve excellence in writing and make an impact with their work.

7 reasons why everyone needs the 7th edition of APA’s bestselling Publication Manual

Full color with first-ever tabbed version

Guidelines for ethical writing and guidance on the publication process

Expanded student-specific resources; includes a sample paper

100+ new reference examples, 40+ sample tables and figures

New chapter on journal article reporting standards

Updated bias-free language guidelines; includes usage of singular “they”

One space after end punctuation!

What’s new in the 7th edition?

Full color All formats are in full color, including the new tabbed spiral-bound version.

Easy to navigate Improved ease of navigation, with many additional numbered sections to help users quickly locate answers to their questions.

Best practices The Publication Manual (7th ed.) has been thoroughly revised and updated to reflect best practices in scholarly writing and publishing.

New student resources Resources for students on writing and formatting annotated bibliographies, response papers, and other paper types as well as guidelines on citing course materials.

Accessibility guidelines Guidelines that support accessibility for all users, including simplified reference, in-text citation, and heading formats as well as additional font options.

New-user content Dedicated chapter for new users of APA Style covering paper elements and format, including sample papers for both professional authors and student writers.

Journal Article Reporting Standards New chapter on journal article reporting standards that includes updates to reporting standards for quantitative research and the first-ever qualitative and mixed methods reporting standards in APA Style.

Bias-free language guidelines New chapter on bias-free language guidelines for writing about people with respect and inclusivity in areas including age, disability, gender, participation in research, race and ethnicity, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, and intersectionality

100+ reference examples More than 100 new reference examples covering periodicals, books, audiovisual media, social media, webpages and websites, and legal resources.

40+ new sample tables and figures More than 40 new sample tables and figures, including student-friendly examples such as a correlation table and a bar chart as well as examples that show how to reproduce a table or figure from another source.

Ethics expanded Expanded guidance on ethical writing and publishing practices, including how to ensure the appropriate level of citation, avoid plagiarism and self-plagiarism, and navigate the publication process.

7th edition table of contents

- Front Matter

- 1. Scholarly Writing and Publishing Principles

- 2. Paper Elements and Format

- 3. Journal Article Reporting Standards

- 4. Writing Style and Grammar

- 5. Bias-Free Language Guidelines

- 6. Mechanics of Style

- 7. Tables and Figures

- 8. Works Credited in the Text

- 9. Reference List

- 10. Reference Examples

- 11. Legal References

- 12. Publication Process

- Back Matter

List of Tables and Figures

Editorial Staff and Contributors

Acknowledgments

Introduction (PDF, 94KB)

Types of Articles and Papers

1.1 Quantitative Articles 1.2 Qualitative Articles 1.3 Mixed Methods Articles 1.4 Replication Articles 1.5 Quantitative and Qualitative Meta-Analyses 1.6 Literature Review Articles 1.7 Theoretical Articles 1.8 Methodological Articles 1.9 Other Types of Articles 1.10 Student Papers, Dissertations, and Theses

Ethical, legal, and professional standards in publishing

Ensuring the Accuracy of Scientific Findings

1.11 Planning for Ethical Compliance 1.12 Ethical and Accurate Reporting of Research Results 1.13 Errors, Corrections, and Retractions After Publication 1.14 Data Retention and Sharing 1.15 Additional Data-Sharing Considerations for Qualitative Research 1.16 Duplicate and Piecemeal Publication of Data 1.17 Implications of Plagiarism and Self-Plagiarism

Protecting the Rights and Welfare of Research Participants and Subjects

1.18 Rights and Welfare of Research Participants and Subjects 1.19 Protecting Confidentiality 1.20 Conflict of Interest

Protecting Intellectual Property Rights

1.21 Publication Credit 1.22 Order of Authors 1.23 Authors’ Intellectual Property Rights During Manuscript Review 1.24 Authors’ Copyright on Unpublished Manuscripts 1.25 Ethical Compliance Checklist

Required Elements

2.1 Professional Paper Required Elements 2.2 Student Paper Required Elements

Paper Elements

2.3 Title Page 2.4 Title 2.5 Author Name (Byline) 2.6 Author Affiliation 2.7 Author Note 2.8 Running Head 2.9 Abstract 2.10 Keywords 2.11 Text (Body) 2.12 Reference List 2.13 Footnotes 2.14 Appendices 2.15 Supplemental Materials

2.16 Importance of Format 2.17 Order of Pages 2.18 Page Header 2.19 Font 2.20 Special Characters 2.21 Line Spacing 2.22 Margins 2.23 Paragraph Alignment 2.24 Paragraph Indentation 2.25 Paper Length

Organization

2.26 Principles of Organization 2.27 Heading Levels 2.28 Section Labels

Sample papers

Overview of Reporting Standards

3.1 Application of the Principles of JARS 3.2 Terminology Used in JARS

Common Reporting Standards Across Research Designs

3.3 Abstract Standards 3.4 Introduction Standards

Reporting Standards for Quantitative Research

3.5 Basic Expectations for Quantitative Research Reporting 3.6 Quantitative Method Standards 3.7 Quantitative Results Standards 3.8 Quantitative Discussion Standards 3.9 Additional Reporting Standards for Typical Experimental and Nonexperimental Studies 3.10 Reporting Standards for Special Designs 3.11 Standards for Analytic Approaches 3.12 Quantitative Meta-Analysis Standards

Reporting Standards for Qualitative Research

3.13 Basic Expectations for Qualitative Research Reporting 3.14 Qualitative Method Standards 3.15 Qualitative Findings or Results Standards 3.16 Qualitative Discussion Standards 3.17 Qualitative Meta-Analysis Standards

Reporting Standards for Mixed Methods Research

3.18 Basic Expectations for Mixed Methods Research Reporting

Effective scholarly writing

Continuity and Flow

4.1 Importance of Continuity and Flow 4.2 Transitions 4.3 Noun Strings

Conciseness and Clarity

4.4 Importance of Conciseness and Clarity 4.5 Wordiness and Redundancy 4.6 Sentence and Paragraph Length 4.7 Tone 4.8 Contractions and Colloquialisms 4.9 Jargon 4.10 Logical Comparisons 4.11 Anthropomorphism

Grammar and usage

4.12 Verb Tense 4.13 Active and Passive Voice 4.14 Mood 4.15 Subject and Verb Agreement

4.16 First- Versus Third-Person Pronouns 4.17 Editorial “We” 4.18 Singular “They” 4.19 Pronouns for People and Animals (“Who” vs. “That”) 4.20 Pronouns as Subjects and Objects (“Who” vs. “Whom”) 4.21 Pronouns in Restrictive and Nonrestrictive Clauses (“That” vs. “Which”)

Sentence Construction

4.22 Subordinate Conjunctions 4.23 Misplaced and Dangling Modifiers 4.24 Parallel Construction

Strategies to Improve Your Writing

4.25 Reading to Learn Through Example 4.26 Writing From an Outline 4.27 Rereading the Draft 4.28 Seeking Help From Colleagues 4.29 Working With Copyeditors and Writing Centers 4.30 Revising a Paper

General Guidelines for Reducing Bias

5.1 Describe at the Appropriate Level of Specificity 5.2 Be Sensitive to Labels

Reducing Bias by Topic

5.3 Age 5.4 Disability 5.5 Gender 5.6 Participation in Research 5.7 Racial and Ethnic Identity 5.8 Sexual Orientation 5.9 Socioeconomic Status 5.10 Intersectionality

Punctuation

6.1 Spacing After Punctuation Marks 6.2 Period 6.3 Comma 6.4 Semicolon 6.5 Colon 6.6 Dash 6.7 Quotation Marks 6.8 Parentheses 6.9 Square Brackets 6.10 Slash

6.11 Preferred Spelling 6.12 Hyphenation

Capitalization

6.13 Words Beginning a Sentence 6.14 Proper Nouns and Trade Names 6.15 Job Titles and Positions 6.16 Diseases, Disorders, Therapies, Theories, and Related Terms 6.17 Titles of Works and Headings Within Works 6.18 Titles of Tests and Measures 6.19 Nouns Followed by Numerals or Letters 6.20 Names of Conditions or Groups in an Experiment 6.21 Names of Factors, Variables, and Effects

6.22 Use of Italics 6.23 Reverse Italics

Abbreviations

6.24 Use of Abbreviations 6.25 Definition of Abbreviations 6.26 Format of Abbreviations 6.27 Unit of Measurement Abbreviations 6.28 Time Abbreviations 6.29 Latin Abbreviations 6.30 Chemical Compound Abbreviations 6.31 Gene and Protein Name Abbreviations

6.32 Numbers Expressed in Numerals 6.33 Numbers Expressed in Words 6.34 Combining Numerals and Words to Express Numbers 6.35 Ordinal Numbers 6.36 Decimal Fractions 6.37 Roman Numerals 6.38 Commas in Numbers 6.39 Plurals of Numbers

Statistical and Mathematical Copy

6.40 Selecting Effective Presentation 6.41 References for Statistics 6.42 Formulas 6.43 Statistics in Text 6.44 Statistical Symbols and Abbreviations 6.45 Spacing, Alignment, and Punctuation for Statistics

Presentation of Equations

6.46 Equations in Text 6.47 Displayed Equations 6.48 Preparing Statistical and Mathematical Copy for Publication

6.49 List Guidelines 6.50 Lettered Lists 6.51 Numbered Lists 6.52 Bulleted Lists

General Guidelines for Tables and Figures

7.1 Purpose of Tables and Figures 7.2 Design and Preparation of Tables and Figures 7.3 Graphical Versus Textual Presentation 7.4 Formatting Tables and Figures 7.5 Referring to Tables and Figures in the Text 7.6 Placement of Tables and Figures 7.7 Reprinting or Adapting Tables and Figures

7.8 Principles of Table Construction 7.9 Table Components 7.10 Table Numbers 7.11 Table Titles 7.12 Table Headings 7.13 Table Body 7.14 Table Notes 7.15 Standard Abbreviations in Tables and Figures 7.16 Confidence Intervals in Tables 7.17 Table Borders and Shading 7.18 Long or Wide Tables 7.19 Relation Between Tables 7.20 Table Checklist 7.21 Sample Tables

Sample tables

7.22 Principles of Figure Construction 7.23 Figure Components 7.24 Figure Numbers 7.25 Figure Titles 7.26 Figure Images 7.27 Figure Legends 7.28 Figure Notes 7.29 Relation Between Figures 7.30 Photographs 7.31 Considerations for Electrophysiological, Radiological, Genetic, and Other Biological Data 7.32 Electrophysiological Data 7.33 Radiological (Imaging) Data 7.34 Genetic Data 7.35 Figure Checklist 7.36 Sample Figures

Sample figures

General Guidelines for Citation

8.1 Appropriate Level of Citation 8.2 Plagiarism 8.3 Self-Plagiarism 8.4 Correspondence Between Reference List and Text 8.5 Use of the Published Version or Archival Version 8.6 Primary and Secondary Sources

Works Requiring Special Approaches to Citation

8.7 Interviews 8.8 Classroom or Intranet Sources 8.9 Personal Communications

In-Text Citations

8.10 Author–Date Citation System 8.11 Parenthetical and Narrative Citations 8.12 Citing Multiple Works 8.13 Citing Specific Parts of a Source 8.14 Unknown or Anonymous Author 8.15 Translated, Reprinted, Republished, and Reissued Dates 8,16 Omitting the Year in Repeated Narrative Citations 8.17 Number of Authors to Include in In-Text Citations 8.18 Avoiding Ambiguity in In-Text Citations 8.19 Works With the Same Author and Same Date 8.20 Authors With the Same Surname 8.21 Abbreviating Group Authors 8.22 General Mentions of Websites, Periodicals, and Common Software and Apps

Paraphrases and Quotations

8.23 Principles of Paraphrasing 8.24 Long Paraphrases 8.25 Principles of Direct Quotation 8.26 Short Quotations (Fewer Than 40 Words) 8.27 Block Quotations (40 Words or More) 8.28 Direct Quotation of Material Without Page Numbers 8.29 Accuracy of Quotations 8.30 Changes to a Quotation Requiring No Explanation 8.31 Changes to a Quotation Requiring Explanation 8.32 Quotations That Contain Citations to Other Works 8.33 Quotations That Contain Material Already in Quotation Marks 8.34 Permission to Reprint or Adapt Lengthy Quotations 8.35 Epigraphs 8.36 Quotations From Research Participants

Reference Categories

9.1 Determining the Reference Category 9.2 Using the Webpages and Websites Reference Category 9.3 Online and Print References

Principles of Reference List Entries

9.4 Four Elements of a Reference 9.5 Punctuation Within Reference List Entries 9.6 Accuracy and Consistency in References

Reference elements

9.7 Definition of Author 9.8 Format of the Author Element 9.9 Spelling and Capitalization of Author Names 9.10 Identification of Specialized Roles 9.11 Group Authors 9.12 No Author

9.13 Definition of Date 9.14 Format of the Date Element 9.15 Updated or Reviewed Online Works 9.16 Retrieval Dates 9.17 No Date

9.18 Definition of Title 9.19 Format of the Title Element 9.20 Series and Multivolume Works 9.21 Bracketed Descriptions 9.22 No Title

9.23 Definition of Source 9.24 Format of the Source Element 9.25 Periodical Sources 9.26 Online Periodicals With Missing Information 9.27 Article Numbers 9.28 Edited Book Chapter and Reference Work Entry Sources 9.29 Publisher Sources 9.30 Database and Archive Sources 9.31 Works With Specific Locations 9.32 Social Media Sources 9.33 Website Sources 9.34 When to Include DOIs and URLs 9.35 Format of DOIs and URLs 9.36 DOI or URL Shorteners 9.37 No Source

Reference Variations

9.38 Works in Another Language 9.39 Translated Works 9.40 Reprinted Works 9.41 Republished or Reissued Works 9.42 Religious and Classical Works

Reference List Format and Order

9.43 Format of the Reference List 9.44 Order of Works in the Reference List 9.45 Order of Surname and Given Name 9.46 Order of Multiple Works by the Same First Author 9.47 Order of Works With the Same Author and Same Date 9.48 Order of Works by First Authors With the Same Surname 9.49 Order of Works With No Author or an Anonymous Author 9.50 Abbreviations in References 9.51 Annotated Bibliographies 9.52 References Included in a Meta-Analysis

Author Variations

Date Variations

Title Variations

Source Variations

Textual Works

10.1 Periodicals 10.2 Books and Reference Works 10.3 Edited Book Chapters and Entries in Reference Works 10.4 Reports and Gray Literature 10.5 Conference Sessions and Presentations 10.6 Dissertations and Theses 10.7 Reviews 10.8 Unpublished Works and Informally Published Works

Data Sets, Software, and Tests

10.9 Data Sets 10.10 Computer Software, Mobile Apps, Apparatuses, and Equipment 10.11 Tests, Scales, and Inventories

Audiovisual Media

10.12 Audiovisual Works 10.13 Audio Works 10.14 Visual Works

Online Media

10.15 Social Media 10.16 Webpages and Websites

General Guidelines for Legal References

11.1 APA Style References Versus Legal References 11.2 General Forms 11.3 In-Text Citations of Legal Materials

Legal Reference Examples

11.4 Cases or Court Decisions 11.5 Statutes (Laws and Acts) 11.6 Legislative Materials 11.7 Administrative and Executive Materials 11.8 Patents 11.9 Constitutions and Charters 11.10 Treaties and International Conventions

Preparing for Publication

12.1 Adapting a Dissertation or Thesis Into a Journal Article 12.2 Selecting a Journal for Publication 12.3 Prioritizing Potential Journals 12.4 Avoiding Predatory Journals

Understanding the Editorial Publication Process

12.5 Editorial Publication Process 12.6 Role of the Editors 12.7 Peer Review Process 12.8 Manuscript Decisions

Manuscript Preparation

12.9 Preparing the Manuscript for Submission 12.10 Using an Online Submission Portal 12.11 Writing a Cover Letter 12.12 Corresponding During Publication 12.13 Certifying Ethical Requirements

Copyright and Permission Guidelines

12.14 General Guidelines for Reprinting or Adapting Materials 12.15 Materials That Require Copyright Attribution 12.16 Copyright Status 12.17 Permission and Fair Use 12.18 Copyright Attribution Formats

During and After Publication

12.19 Article Proofs 12.20 Published Article Copyright Policies 12.21 Open Access Deposit Policies 12.22 Writing a Correction Notice 12.23 Sharing Your Article Online 12.24 Promoting Your Article

Credits for Adapted Tables, Figures, and Papers

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Welcome to the Purdue Online Writing Lab

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

The Online Writing Lab (the Purdue OWL) at Purdue University houses writing resources and instructional material, and we provide these as a free service at Purdue. Students, members of the community, and users worldwide will find information to assist with many writing projects. Teachers and trainers may use this material for in-class and out-of-class instruction.

The On-Campus and Online versions of Purdue OWL assist clients in their development as writers—no matter what their skill level—with on-campus consultations, online participation, and community engagement. The Purdue OWL serves the Purdue West Lafayette and Indianapolis campuses and coordinates with local literacy initiatives. The Purdue OWL offers global support through online reference materials and services.

Social Media

Facebook twitter.

Advancing Physics-Based Simulations: Integrating Conventional and Machine-Learning Approaches for Enhanced Computational Efficiency

- Advisor(s): Terzopoulos, Demetri

This thesis presents novel approaches to improve the accuracy and efficiency of scientific simulations, particularly those involving complex geometries, intrinsic physical modeling, and demanding computational costs.

The first contribution extends the MPM to unstructured meshes, addressing the challenges of the transfer kernel's gradient continuity and stability issue on any general mesh tesselation. The Unstructured Moving Least Squares MPM (UMLS-MPM) incorporates a diminishing function into the MLS kernel's sample weights, ensuring an analytically continuous function and gradient reconstruction. It is the first-of-its-kind framework in this field. Several numerical test cases demonstrate the method's stability and accuracy.

The second contribution is a hybrid scheme for modeling the interaction between compressible flow, shock waves, and deformable structures. By combining recent advancements in time-splitting compressible flow and Material Point Methods (MPMs), this approach seamlessly integrates Eulerian and Lagrangian/Eulerian methods for monolithic flow-structure interactions. Reflective and penetrable boundary conditions handle deforming boundaries with sub-cell particles, while a mixed-order finite element formulation utilizing B-spline shape functions discretizes the coupled velocity-pressure system. This comprehensive framework accurately captures shock wave propagation, temperature/density-induced buoyancy effects, and topology changes in solids.

The third contribution addresses challenges in learning physical simulations on large-scale meshes using Graph Neural Networks (GNNs). Existing state-of-the-art methods often encounter issues related to over-smoothing and incorrect edge construction during multi-scale adaptation. To overcome these limitations, a novel pooling strategy, termed \textit{bi-stride}, is introduced. This approach, inspired by bipartite graph structures, involves pooling nodes on alternate frontiers of the breadth-first search (BFS), eliminating the need for labor-intensive manual creation of coarser meshes and mitigating incorrect edge problems. The proposed \textit{BSMS-GNN} framework employs non-parametrized pooling and unpooling through interpolations, resulting in a substantial reduction of computational costs and improved efficiency. Experimental results demonstrate the superiority of the \textit{BSMS-GNN} framework in terms of both accuracy and computational efficiency in representative physical simulations on large-scale meshes.

Enter the password to open this PDF file:

From article to art: Creating visual abstracts - Parts 1 & 2: A Guide to Visual Abstracts

Michelle Feng He

Ginny Pittman

About this video

What is a visual abstract and why should you use visual abstracts in your research? How can you create a visual abstract and what message from your research should you select? Hear from Michelle Feng He and Ginny Pittman, as they guide you through visual abstracts in parts 1 & 2 of our "From article to art: Creating visual abstracts" module.

About the presenters

Publisher, Elsevier

Based in New York, Michelle joined Elsevier from Springer Nature where she developed the journal strategies across their oncology, surgery, pathology, and life-sciences programs. Her interests and strengths lie in data science, society partnership management, and reviewer engagement programs. As a Publisher, Michelle’s first priority is ensuring that all journal stakeholders have the necessary data to make strategic decisions regarding the impact and growth of their journals.

Executive Publisher, Elsevier

Ginny leads the orthopedics portfolio in the US, with 18 open access and subscription journals. She has over 25 years of experience in scholarly research publishing and educational product development, making an impact in the healthcare and life sciences fields at Wolters Kluwer, Mary Ann Liebert Publishers and Wiley-Blackwell. She has presented to author communities at medical institutions globally and has created new approaches to portfolio development, metrics, and author/editor training and tools, earning multiple awards for innovation.

Visual abstract design resources

- DOI: 10.36655/jetal.v5i2.1484

- Corpus ID: 270415473

Errors Found in Students' Theses: Capitalization, Punctuation, and Spelling

- Nopa Ayu lia Putri

- Published in JETAL: Journal of English… 24 April 2024

- Education, Linguistics

- JETAL: Journal of English Teaching & Applied Linguistic

17 References

Analysis of language errors in student thesis, students’ errors in using punctuation and capitalization, the most frequent capitalization errors made by the efl learners at undergraduate level: an investigation, spelling error analysis in students’ writing english composition, analisis kesalahan ejaan pada karya ilmiah mahasiswa bahasa indonesia stkip bina bangsa getsempena banda aceh, linguistic error analysis on students' thesis proposals., error analysis in academic writing: a case of international postgraduate students in malaysia, errors of spelling, capitalization, and punctuation marks in writing encountered by first year college students in al-merghib university libya, common grammatical errors in the use of english as a foreign language: a case in students’ undergraduate theses, evaluating capitalization errors in saudi female students' efl writing at bisha university, related papers.

Showing 1 through 3 of 0 Related Papers

Introductions

What this handout is about.

This handout will explain the functions of introductions, offer strategies for creating effective introductions, and provide some examples of less effective introductions to avoid.

The role of introductions

Introductions and conclusions can be the most difficult parts of papers to write. Usually when you sit down to respond to an assignment, you have at least some sense of what you want to say in the body of your paper. You might have chosen a few examples you want to use or have an idea that will help you answer the main question of your assignment; these sections, therefore, may not be as hard to write. And it’s fine to write them first! But in your final draft, these middle parts of the paper can’t just come out of thin air; they need to be introduced and concluded in a way that makes sense to your reader.

Your introduction and conclusion act as bridges that transport your readers from their own lives into the “place” of your analysis. If your readers pick up your paper about education in the autobiography of Frederick Douglass, for example, they need a transition to help them leave behind the world of Chapel Hill, television, e-mail, and The Daily Tar Heel and to help them temporarily enter the world of nineteenth-century American slavery. By providing an introduction that helps your readers make a transition between their own world and the issues you will be writing about, you give your readers the tools they need to get into your topic and care about what you are saying. Similarly, once you’ve hooked your readers with the introduction and offered evidence to prove your thesis, your conclusion can provide a bridge to help your readers make the transition back to their daily lives. (See our handout on conclusions .)

Note that what constitutes a good introduction may vary widely based on the kind of paper you are writing and the academic discipline in which you are writing it. If you are uncertain what kind of introduction is expected, ask your instructor.

Why bother writing a good introduction?

You never get a second chance to make a first impression. The opening paragraph of your paper will provide your readers with their initial impressions of your argument, your writing style, and the overall quality of your work. A vague, disorganized, error-filled, off-the-wall, or boring introduction will probably create a negative impression. On the other hand, a concise, engaging, and well-written introduction will start your readers off thinking highly of you, your analytical skills, your writing, and your paper.

Your introduction is an important road map for the rest of your paper. Your introduction conveys a lot of information to your readers. You can let them know what your topic is, why it is important, and how you plan to proceed with your discussion. In many academic disciplines, your introduction should contain a thesis that will assert your main argument. Your introduction should also give the reader a sense of the kinds of information you will use to make that argument and the general organization of the paragraphs and pages that will follow. After reading your introduction, your readers should not have any major surprises in store when they read the main body of your paper.

Ideally, your introduction will make your readers want to read your paper. The introduction should capture your readers’ interest, making them want to read the rest of your paper. Opening with a compelling story, an interesting question, or a vivid example can get your readers to see why your topic matters and serve as an invitation for them to join you for an engaging intellectual conversation (remember, though, that these strategies may not be suitable for all papers and disciplines).

Strategies for writing an effective introduction

Start by thinking about the question (or questions) you are trying to answer. Your entire essay will be a response to this question, and your introduction is the first step toward that end. Your direct answer to the assigned question will be your thesis, and your thesis will likely be included in your introduction, so it is a good idea to use the question as a jumping off point. Imagine that you are assigned the following question:

Drawing on the Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass , discuss the relationship between education and slavery in 19th-century America. Consider the following: How did white control of education reinforce slavery? How did Douglass and other enslaved African Americans view education while they endured slavery? And what role did education play in the acquisition of freedom? Most importantly, consider the degree to which education was or was not a major force for social change with regard to slavery.

You will probably refer back to your assignment extensively as you prepare your complete essay, and the prompt itself can also give you some clues about how to approach the introduction. Notice that it starts with a broad statement and then narrows to focus on specific questions from the book. One strategy might be to use a similar model in your own introduction—start off with a big picture sentence or two and then focus in on the details of your argument about Douglass. Of course, a different approach could also be very successful, but looking at the way the professor set up the question can sometimes give you some ideas for how you might answer it. (See our handout on understanding assignments for additional information on the hidden clues in assignments.)

Decide how general or broad your opening should be. Keep in mind that even a “big picture” opening needs to be clearly related to your topic; an opening sentence that said “Human beings, more than any other creatures on earth, are capable of learning” would be too broad for our sample assignment about slavery and education. If you have ever used Google Maps or similar programs, that experience can provide a helpful way of thinking about how broad your opening should be. Imagine that you’re researching Chapel Hill. If what you want to find out is whether Chapel Hill is at roughly the same latitude as Rome, it might make sense to hit that little “minus” sign on the online map until it has zoomed all the way out and you can see the whole globe. If you’re trying to figure out how to get from Chapel Hill to Wrightsville Beach, it might make more sense to zoom in to the level where you can see most of North Carolina (but not the rest of the world, or even the rest of the United States). And if you are looking for the intersection of Ridge Road and Manning Drive so that you can find the Writing Center’s main office, you may need to zoom all the way in. The question you are asking determines how “broad” your view should be. In the sample assignment above, the questions are probably at the “state” or “city” level of generality. When writing, you need to place your ideas in context—but that context doesn’t generally have to be as big as the whole galaxy!

Try writing your introduction last. You may think that you have to write your introduction first, but that isn’t necessarily true, and it isn’t always the most effective way to craft a good introduction. You may find that you don’t know precisely what you are going to argue at the beginning of the writing process. It is perfectly fine to start out thinking that you want to argue a particular point but wind up arguing something slightly or even dramatically different by the time you’ve written most of the paper. The writing process can be an important way to organize your ideas, think through complicated issues, refine your thoughts, and develop a sophisticated argument. However, an introduction written at the beginning of that discovery process will not necessarily reflect what you wind up with at the end. You will need to revise your paper to make sure that the introduction, all of the evidence, and the conclusion reflect the argument you intend. Sometimes it’s easiest to just write up all of your evidence first and then write the introduction last—that way you can be sure that the introduction will match the body of the paper.

Don’t be afraid to write a tentative introduction first and then change it later. Some people find that they need to write some kind of introduction in order to get the writing process started. That’s fine, but if you are one of those people, be sure to return to your initial introduction later and rewrite if necessary.

Open with something that will draw readers in. Consider these options (remembering that they may not be suitable for all kinds of papers):

- an intriguing example —for example, Douglass writes about a mistress who initially teaches him but then ceases her instruction as she learns more about slavery.

- a provocative quotation that is closely related to your argument —for example, Douglass writes that “education and slavery were incompatible with each other.” (Quotes from famous people, inspirational quotes, etc. may not work well for an academic paper; in this example, the quote is from the author himself.)

- a puzzling scenario —for example, Frederick Douglass says of slaves that “[N]othing has been left undone to cripple their intellects, darken their minds, debase their moral nature, obliterate all traces of their relationship to mankind; and yet how wonderfully they have sustained the mighty load of a most frightful bondage, under which they have been groaning for centuries!” Douglass clearly asserts that slave owners went to great lengths to destroy the mental capacities of slaves, yet his own life story proves that these efforts could be unsuccessful.

- a vivid and perhaps unexpected anecdote —for example, “Learning about slavery in the American history course at Frederick Douglass High School, students studied the work slaves did, the impact of slavery on their families, and the rules that governed their lives. We didn’t discuss education, however, until one student, Mary, raised her hand and asked, ‘But when did they go to school?’ That modern high school students could not conceive of an American childhood devoid of formal education speaks volumes about the centrality of education to American youth today and also suggests the significance of the deprivation of education in past generations.”

- a thought-provoking question —for example, given all of the freedoms that were denied enslaved individuals in the American South, why does Frederick Douglass focus his attentions so squarely on education and literacy?

Pay special attention to your first sentence. Start off on the right foot with your readers by making sure that the first sentence actually says something useful and that it does so in an interesting and polished way.

How to evaluate your introduction draft

Ask a friend to read your introduction and then tell you what they expect the paper will discuss, what kinds of evidence the paper will use, and what the tone of the paper will be. If your friend is able to predict the rest of your paper accurately, you probably have a good introduction.

Five kinds of less effective introductions

1. The placeholder introduction. When you don’t have much to say on a given topic, it is easy to create this kind of introduction. Essentially, this kind of weaker introduction contains several sentences that are vague and don’t really say much. They exist just to take up the “introduction space” in your paper. If you had something more effective to say, you would probably say it, but in the meantime this paragraph is just a place holder.

Example: Slavery was one of the greatest tragedies in American history. There were many different aspects of slavery. Each created different kinds of problems for enslaved people.

2. The restated question introduction. Restating the question can sometimes be an effective strategy, but it can be easy to stop at JUST restating the question instead of offering a more specific, interesting introduction to your paper. The professor or teaching assistant wrote your question and will be reading many essays in response to it—they do not need to read a whole paragraph that simply restates the question.

Example: The Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass discusses the relationship between education and slavery in 19th century America, showing how white control of education reinforced slavery and how Douglass and other enslaved African Americans viewed education while they endured. Moreover, the book discusses the role that education played in the acquisition of freedom. Education was a major force for social change with regard to slavery.

3. The Webster’s Dictionary introduction. This introduction begins by giving the dictionary definition of one or more of the words in the assigned question. Anyone can look a word up in the dictionary and copy down what Webster says. If you want to open with a discussion of an important term, it may be far more interesting for you (and your reader) if you develop your own definition of the term in the specific context of your class and assignment. You may also be able to use a definition from one of the sources you’ve been reading for class. Also recognize that the dictionary is also not a particularly authoritative work—it doesn’t take into account the context of your course and doesn’t offer particularly detailed information. If you feel that you must seek out an authority, try to find one that is very relevant and specific. Perhaps a quotation from a source reading might prove better? Dictionary introductions are also ineffective simply because they are so overused. Instructors may see a great many papers that begin in this way, greatly decreasing the dramatic impact that any one of those papers will have.

Example: Webster’s dictionary defines slavery as “the state of being a slave,” as “the practice of owning slaves,” and as “a condition of hard work and subjection.”

4. The “dawn of man” introduction. This kind of introduction generally makes broad, sweeping statements about the relevance of this topic since the beginning of time, throughout the world, etc. It is usually very general (similar to the placeholder introduction) and fails to connect to the thesis. It may employ cliches—the phrases “the dawn of man” and “throughout human history” are examples, and it’s hard to imagine a time when starting with one of these would work. Instructors often find them extremely annoying.

Example: Since the dawn of man, slavery has been a problem in human history.

5. The book report introduction. This introduction is what you had to do for your elementary school book reports. It gives the name and author of the book you are writing about, tells what the book is about, and offers other basic facts about the book. You might resort to this sort of introduction when you are trying to fill space because it’s a familiar, comfortable format. It is ineffective because it offers details that your reader probably already knows and that are irrelevant to the thesis.

Example: Frederick Douglass wrote his autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave , in the 1840s. It was published in 1986 by Penguin Books. In it, he tells the story of his life.

And now for the conclusion…

Writing an effective introduction can be tough. Try playing around with several different options and choose the one that ends up sounding best to you!

Just as your introduction helps readers make the transition to your topic, your conclusion needs to help them return to their daily lives–but with a lasting sense of how what they have just read is useful or meaningful. Check out our handout on conclusions for tips on ending your paper as effectively as you began it!

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Douglass, Frederick. 1995. Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, Written by Himself . New York: Dover.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

- eng.umd.edu

- Faculty Directory

- Uploading Your Video

- Publications

- Thesis Abstracts

2019 Thesis Abstracts

Two-Phase Flow Regimes and Heat Transfer in a Manifolded-Microgap

by David Deisenroth

Embedded cooling—an emerging thermal management paradigm for electronic devices—has motivated further research in compact, high heat flux, cooling solutions. Reliance on phase-change cooling and the associated two-phase flow of dielectric refrigerants allows small fluid flow rates to absorb large heat loads. Previous research has shown that dividing chip-scale microchannels into parallel arrays of channels with novel manifold designs can produce very high chip-scale heat transfer coefficients with low pressure drops. In such manifolded microchannel coolers, the coolant typically flows at relatively high velocities through U-shaped microgap channels, producing centripetal acceleration forces on the fluid that can be several orders of magnitude larger than gravity. Furthermore, the manifolded microchannels consist of high aspect ratio rectangular channels, short length to hydraulic diameter ratios (L/Dh < 100), and step-like inlet restrictions. The existing literature provides only limited information on each of these effects, and nearly no information on the combined effects, on fluid flow and heat transfer performance.

This study provides fundamental insights into the impact of such channel features and coupled fluid forces on two-phase flow regimes and their associated transport rates. Moreover, because the flows in manifolded microchannel chip coolers are very small and optically inaccessible, a custom visualization test section was developed. The visualization test section was supported by a custom two-phase flow loop, which incorporated three power supplies, two chillers, and two dozen thermofluid sensors with live data monitoring. The fluid flow and wall heat transfer in the visualization test section was simultaneously imaged with a high-speed optical camera and a high-speed thermal camera. The results were reported with maps of the flow regime, wall temperature, wall temperature fluctuation, superheat, heat flux, and heat transfer coefficients under varying heat fluxes and mass fluxes for three manifold designs. Variations in flow phenomena and thermal performance among manifold designs and between R245fa and FC-72 were established. The post-annular flow regime of annular-rivulet was associated with a precipitous decline in wall heat transfer coefficients. The current experimental campaign is the first in the open literature to study the thermal and hydrodynamic characteristics of manifolded-microgap channels in such detail.

Simulation and Analysis of Energy Consumption for Two Complex and Energy intensive Buildings on UMD Campus

by Jason Kelly