The 7 Best Study Methods for All Types of Students

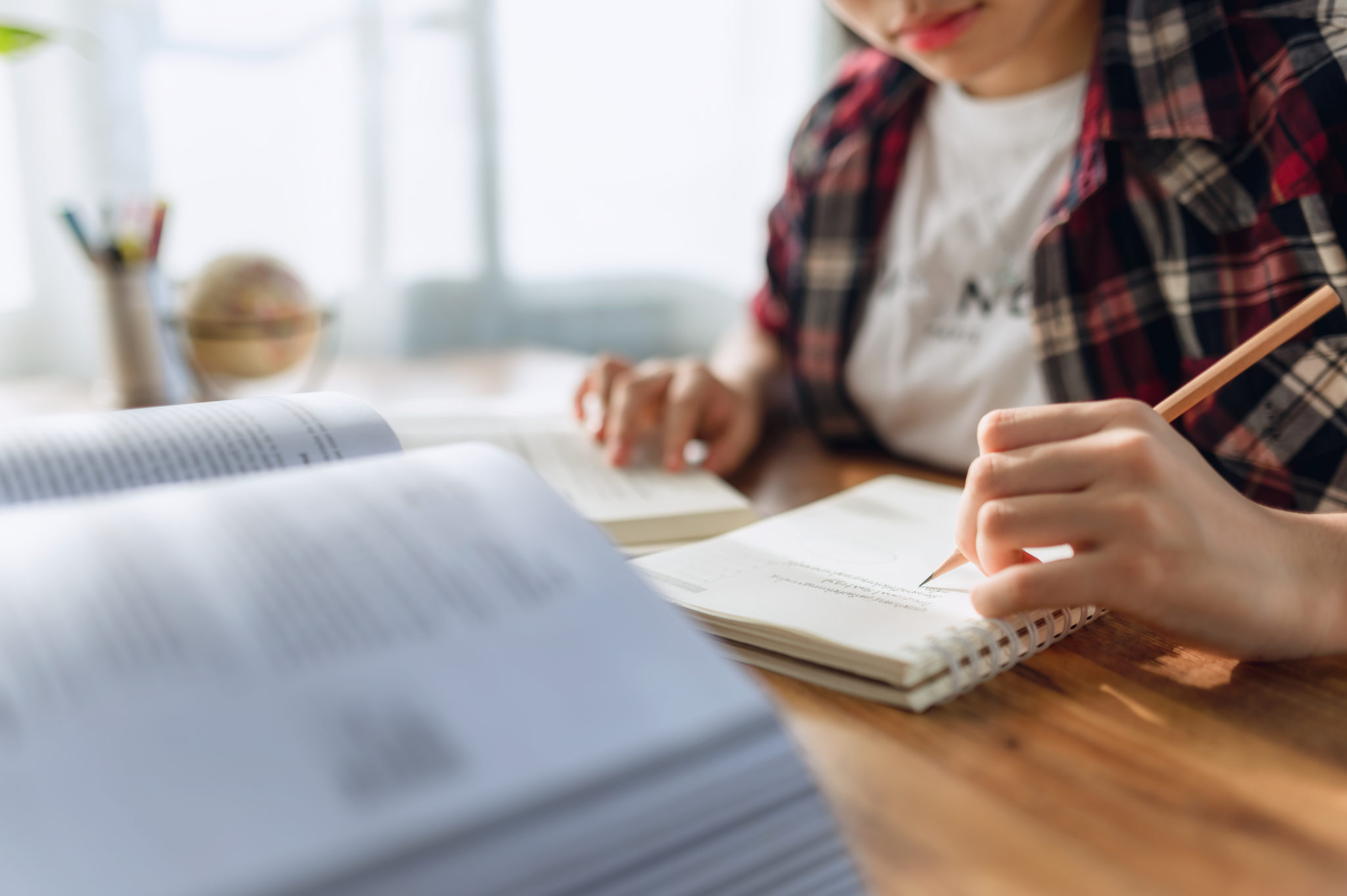

These are seven effective study methods and techniques for students looking to optimize their learning habits.

- By Sander Tamm

- Jan 10, 2023

E-student.org is supported by our community of learners. When you visit links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission.

“You must not fool yourself, and you are the easiest person to fool.” Richard Feynman

Choosing the correct study method is a crucial part of the learning process that students too often skip over. Picking the best study method for the situation can help students reach their full potential, while a poorly chosen study technique will kill any real progress, no matter how hard the student tries to study.

If you’re reading this article, you’re likely the exception, but the reality is that most students rely on ineffective study strategies. Researchers have found that between 83.6% and 84% of students rely on rereading: a study method that provides minimal benefits .

There are far superior study methods out there than rereading. Methods that have been developed and researched by the world’s top learning scientists. Yet, surprisingly few students have ever heard of them. That is why utilizing them effectively will give you not only an edge but an entire leg up on the competition.

These are the seven best study methods all students should know about:

Best Study Methods

Spaced repetition.

Spaced repetition , sometimes called spaced practice, interleaved practice, or spaced retrieval, is a study method that involves separating your study sessions into spaced intervals. It’s a simple concept but a game-changer to most students because of how powerful it is.

To demonstrate how spaced repetition works, let’s bring a real-life example. Let’s say you have an exam coming up in 36 days, and your first study session begins today. In this situation, a well-optimized interval might be:

- Session 1: Day 1

- Session 2: Day 7

- Session 3: Day 16

- Session 4: Day 35

- Exam Date: Day 36

In a nutshell, it’s the opposite of cramming and all-nighters. Rather than concentrating all studying into a small time frame, this method requires you to space out your studying by reviewing and recalling information at optimal intervals until the material has been memorized.

In the 21st century, this technique has gathered increasing popularity, and it’s not without reason. Spaced repetition manages to combine all the existing knowledge we have on human memory, and it uses that knowledge to create optimized algorithms for studying. One of the most popular examples of spaced repetition algorithms is Anki , based on another popular algorithm, SuperMemo .

For example, there is no better study method for medical students than Anki-based flashcard decks. There are entire online communities surrounding medical school Anki. You can get a small glimpse of that by heading over to r/medicalschoolanki .

There, you’ll find a breadth of different medical school Anki decks to choose from, such as:

- Pepper deck

- Lightyear deck

- UWorld deck

- Premed95 deck

But, the power of spaced repetition is not at all only applicable to medical students. Anyone trying to become a better and more efficient learner can benefit from spaced repetition. Spaced repetition is used in conjunction with other study methods, and it’s especially powerful when combined with the following study method we’ll discuss: active recall.

Active Recall

Active recall , sometimes called retrieval practice or practice testing, is a study technique involving actively recalling information (rather than just reading or re-reading it) by testing yourself repeatedly. Most students dread the word “test” for good reasons. After all, tests and exams can be very stressful because they are usually the main point of measure for your academic success.

However, active recall teaches us to look at testing from another angle. Not only should we learn for tests, but we should also learn by testing. Through flashcards, self-generated questions, and practice tests, this study method uses self-testing to help your brain memorize, retain, and retrieve information more efficiently.

One study found that students who conducted only one practice test before an exam got 17% better results right after. Two more studies conducted in 2005 and 2012 , plus a 2017 meta-analysis , yielded similar results, finding that students who used active recall and self-testing outperformed students who did not.

If you’re practicing for an upcoming exam, there’s no better study method than active recall. By using active recall, you’re essentially testing yourself dozens of times over. If you conduct these practice tests over a long period of time through spaced repetition, you’ll be able to ace any exam without cramming.

Keep in mind, though, that while very effective, active recall is also one of the most tiring study techniques on this list. It requires strong mental focus, deep concentration, and intense mental stamina. Active recall is cognitively demanding, so don’t expect to breeze through your learning materials with this method.

Next, I’ll cover my favorite time management strategy for students: the Pomodoro method.

Pomodoro Study Method

The Pomodoro study method is a time-management technique that uses a timer to break down your studying into 25-minute (or 45-minute) increments, called Pomodoro sessions. Then, after each session, you’ll take a 5-minute (or 15-minute) break, during which you entirely distance yourself from the study topic. And after completing four such sessions, you’ll take a more extended 15-to-30-minute break.

To try the Pomodoro technique without installing any software or buying a timer, I recommend you go to YouTube. YouTube is full of Pomodoro-based “study with me” videos from channels such as TheStrive Studies , Ali Abdaal , and MDprospect . Many of them include music, though, so if you’re distracted by music while studying, you might benefit from a purpose-built Pomodoro application such as TomatoTimer or RescueTime .

There are various benefits to using the Pomodoro method: it’s a simple and straightforward technique, it forces you to map out your daily tasks and activities, allows for easy tracking of the amount of time spent on each task, and it provides short bursts of concentrated work together with resting periods.

But, it’s also worth noting that the scientific evidence behind the Pomodoro method is mostly conjectural as there is little scientific research on its effectiveness. And another drawback of the Pomodoro study technique is that it’s not ideal for tasks that require prolonged, uninterrupted focusing. For these kinds of tasks, I recommend that you look into the closely related Flowtime method instead.

Despite that, though, I use the Pomodoro method on a daily basis myself, and it has become an integral and irreplaceable part of my workflow.

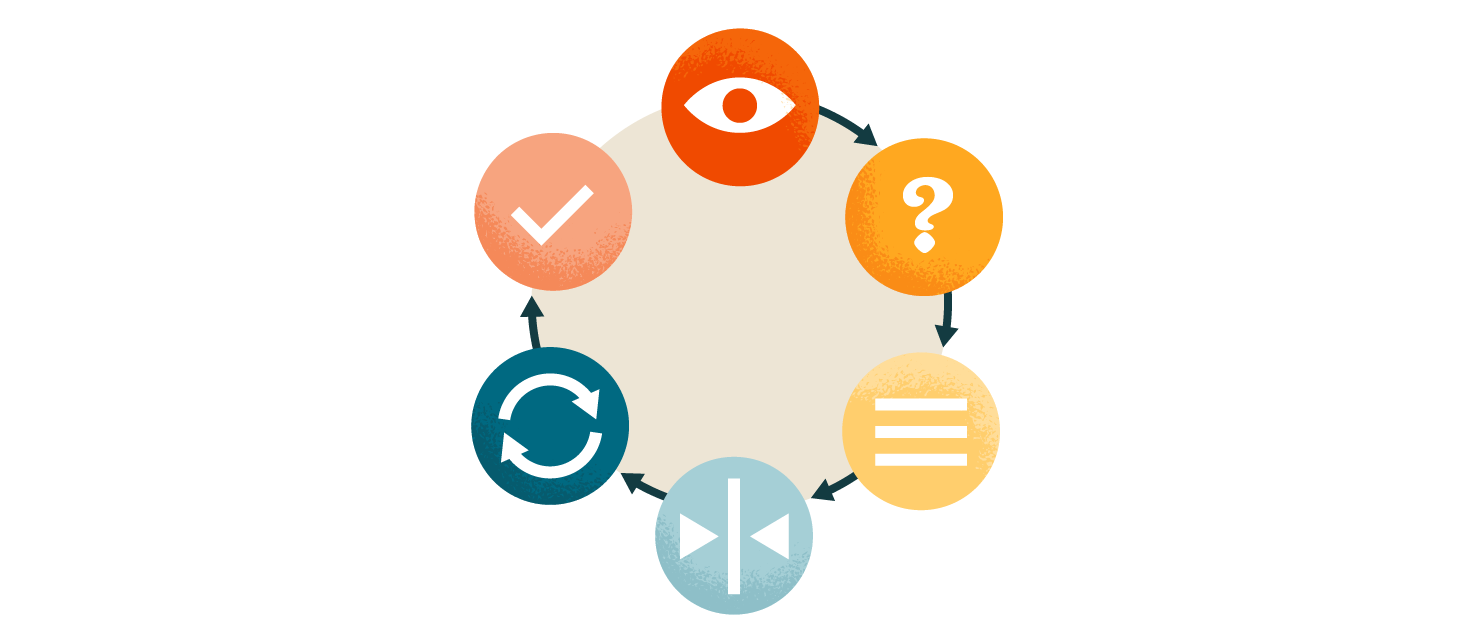

Feynman Technique

The Feynman Technique is a flexible, easy-to-use, and effective study technique developed by Nobel Prize-winning physicist Richard Feynman. It is based on a simple idea: the best way to learn any topic is by teaching it to a sixth-grade child.

While this concept is not as advanced as the super-optimized spaced repetition algorithms I covered earlier, it’s still a method that continues to be relevant nearly a century after its creation.

The Feynman Technique is a powerful learning tool that requires learners to step out of their comfort zone by breaking down even the most complex topics into easily digestible chunks. Digestible enough for the average sixth-grade child.

This may seem like an easy task at first. After all, how difficult could it be to explain something to a child? In practice, it can be very difficult because you have to simplify and explain everything in an age-appropriate manner. When you start using the method, you’ll quickly realize that unless you have fully mastered the topic, meeting a child at their level of understanding is not easy.

To explain something clearly, you need to define all unfamiliar terms, generate straightforward explanations for complex ideas, understand connections between different topics and sub-topics, and articulate what is learned clearly and concisely. The Feynman Technique forces you to learn more deeply and think critically about what you are learning, and that is also why it’s a compelling learning method.

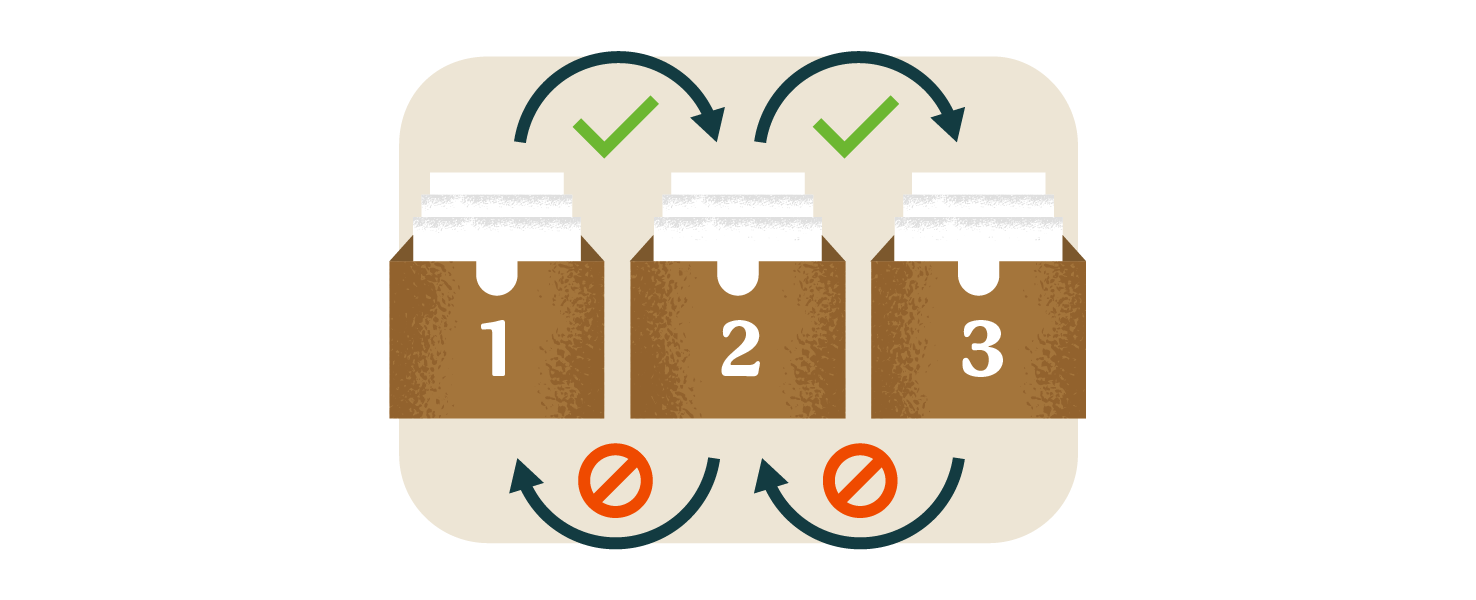

Leitner System

The Leitner System is a simple and effective study method that uses a flashcard-based learning strategy to maximize memorization. It was developed by Sebastian Leitner back in 1972, and it was a source of inspiration to many of the newer flashcard-based methods that succeeded it, such as Anki.

To use the method, you’ll first need to create flashcards. On the front of the cards, you’ll write the questions, and on the back, the answers. Then, once you have your flashcards ready, get three “Leitner boxes” big enough to hold all the cards you’ve created. Let’s name them Box 1, 2, and 3.

Now, you’re all set to start studying with your flashcards. In the beginning, you’ll place all cards in Box 1. Take a card from Box 1 and try to retrieve the answer from your memory. If you recall the answer, put it in Box 2. If not, keep it in Box 1. Then, you’ll repeat this until you’ve reviewed all the cards in Box 1 at least once. After that, you’ll start reviewing each box of cards based on time intervals.

Here’s an animation that shows how the Leitner System works:

Besides card placement, another important detail of the system is scheduling. Every box has a set review frequency, with Box 1 being reviewed the most frequently as it contains all the most difficult-to-learn flashcards. Box 3, on the other hand, will contain the cards you’ve already recalled correctly, which is why it does not need to be reviewed as frequently.

If you’ve never heard of the Leitner system, you might be surprised to hear that some of the world’s biggest learning platforms, such as Duolingo, use a variation to teach hundreds of millions of students. It’s particularly effective at language learning due to the ease of creating translation-based flashcards.

While I love the Leitner System for its simplicity, I don’t use it often anymore due to the lengthy setup process, and other flashcard study methods, such as Anki, tend to be more time-efficient. But, if you prefer physical flashcards over virtual ones, you should consider using the Leitner system. It’s a beautiful study technique that has stood the test of time.

PQ4R Study Method

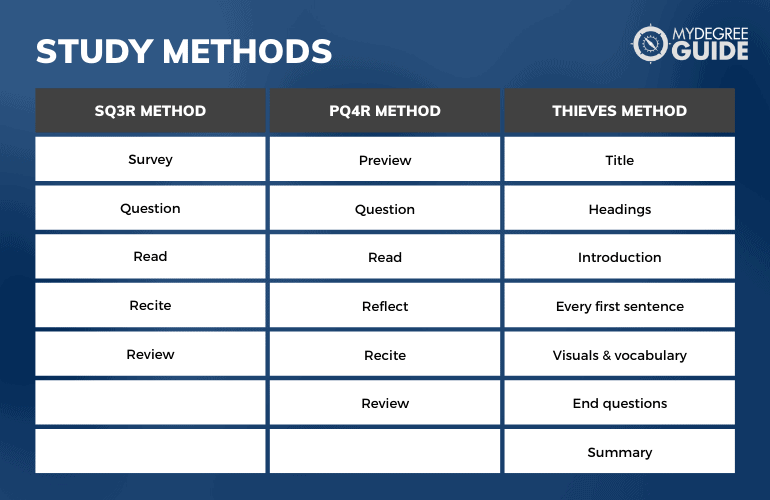

The PQ4R is a study method developed by researchers Thomas and Robinson in 1972 – the same year as the Leitner System was conceived. PQ4R stands for the steps used for learning something new: Preview, Question, Read, Reflect, Recite, and Review. It’s commonly used to improve reading comprehension and is an essential method for students with reading disabilities.

However, the usefulness of PQ4R is not restricted to students with reading disabilities. The same six steps can be taken by any student trying to understand better what they’re reading. Improving reading comprehension is a worthy goal for any student, and if you need to read through a massive textbook for an exam, the PQ4R method offers a practical framework. It will allow you to understand all the passages of the text better and help you retain the information better.

By improving our reading comprehension, we can better synthesize information and interpret text. However, we must be careful not to let this strategy consume too much of our time in study sessions. Many modern learning scientists consider reading a passive and ineffective study strategy, and it’s best to rely on other methods when you can.

While I don’t use this study method as frequently as most other methods on this list, I still consider it an important strategy in my skill set. Whenever I need to extract the most critical details from a large textbook, I bring out the PQ4R to help me get through the information quicker while boosting memorization and retention. The PQ4R is a good study method to have ready, but it’s not something you should view as your primary strategy.

SQ3R Study Method

The SQ3R study method was developed by Francis P. Robinson in 1946 and is the predecessor of the PQ4R method. It’s a time-proven study technique that can be adapted to virtually any subject. The method’s name stands for Survey, Question, Read, Recite, and Review and it can be used to study anything quicker, better, and in a more structured way than conventional methods.

While groundbreaking for its time, the SQ3R study method has the same drawbacks as the newer PQ4R method. For one, it’s mainly used for improving reading comprehension, and reading is not considered an effective study strategy anymore. Another problem the method faces is that it lacks the “reflection” component that the newer PQ4R study method brings to the table.

In addition, three of the five steps of this method involve a passive approach (surveying, reading, and reviewing) rather than an active one. Modern learning theories suggest active retrieval is far better for information retention than passive reading. Thus, I recommend using this study method only when you don’t have the time to use a more robust method, such as spaced repetition.

SQ3R is best used when you have limited time to study, and your primary source of information comes from a textbook. In such cases, the technique can be very helpful for summarizing the key points written in the source material.

Now, it’s time to start wrapping up this article.

In conclusion, there are many excellent study methods you have to choose from as a student in the 21st century. The best one for you will depend on your learning style, the material you are studying, and how much free time you have. When possible, I recommend you study using a combination of spaced repetition, active recall, and the Pomodoro method. But the other strategies listed here certainly have their uses as well. Above all, try to be flexible and keep an open mind. In doing so, you’ll be able to maximize your learning potential.

Sander Tamm

Disadvantages of E-Learning: The Challenge of Hands-on Disciplines

The move to digital platforms poses a particular challenge in fields where hands-on practice is needed. In this article, we’ll look at the main issues at stake and how they can be overcome.

Top 8 Best Online PHP Courses & Free Tutorials

Here are our picks for the very best online PHP courses to help you learn this valuable programming language from the comfort of your own home.

The Outline Note-Taking Method: A Beginner’s Guide

Follow this step-by-step guide to master the outline method of note-taking as a complete beginner.

25 Scientifically Proven Tips for More Effective Studying

Staying on top of schoolwork can be tough.

Whether you’re in high school, or an adult going back to college, balancing coursework with other responsibilities can be challenging. If you’re teetering on the edge of burnout, here are some study tips that are scientifically proven to help you succeed!

Editorial Listing ShortCode:

2024 Ultimate Study Tips Guide

In this guide, we explore scientifically-proven study techniques from scientific journals and some of the world’s best resources like Harvard, Yale, MIT, and Cornell.

In a hurry? Skip ahead to the section that interests you most.

- How to Prepare for Success

- Create Your Perfect Study Space

- Pick a Study Method that Works for You

- Effective Study Skills

- How to Study More Efficiently

- How to Study for Tests

- Memory Improvement Techniques

- Top 10 Study Hacks Backed by Science

- Best Study Apps

- Study Skills Worksheets

- Key Takeaways

This comprehensive guide covers everything from studying for exams to the best study apps. So, let’s get started!

Part 1 – How to Prepare for Success

1. Set a Schedule

“Oh, I’ll get to it soon” isn’t a valid study strategy. Rather, you have to be intentional about planning set study sessions .

On your calendar, mark out chunks of time that you can devote to your studies. You should aim to schedule some study time each day, but other commitments may necessitate that some sessions are longer than others.

Harder classes require more study time. So, too, do classes that are worth several credits. For each credit hour that you’re taking, consider devoting one to three hours to studying each week.

2. Study at Your Own Pace

Do you digest content quickly, or do you need time to let the material sink in? Only you know what pace is best for you.

There’s no right (or wrong) study pace. So, don’t try matching someone else’s speed.

Instead, through trial and error, find what works for you. Just remember that slower studying will require that you devote more time to your schoolwork.

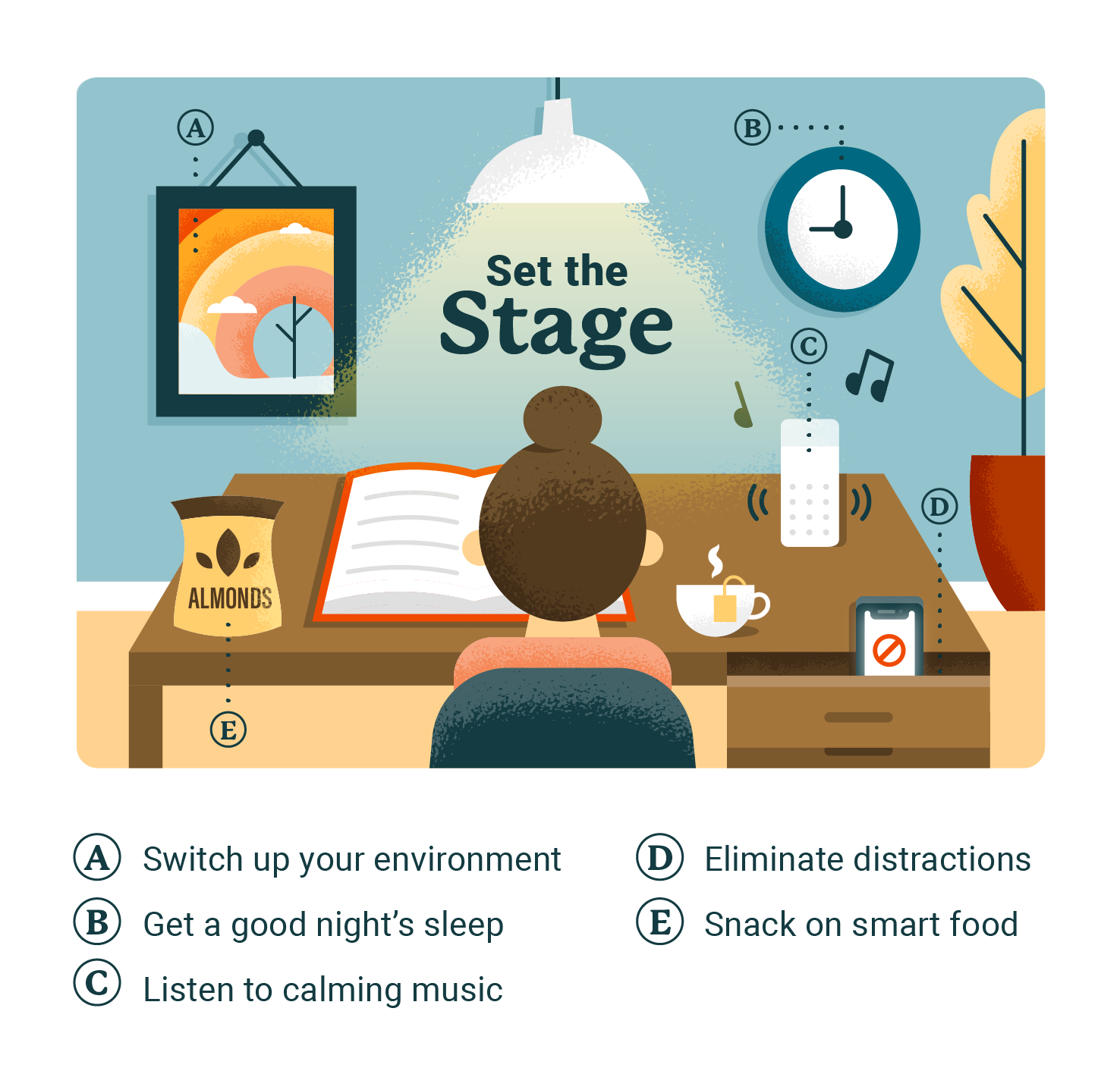

3. Get Some Rest

Exhaustion helps no one perform their best. Your body needs rest ; getting enough sleep is crucial for memory function.

This is one reason that scheduling study time is so important: It reduces the temptation to stay up all night cramming for a big test. Instead, you should aim for seven or more hours of sleep the night before an exam.

Limit pre-studying naps to 15 or 20 minutes at a time. Upon waking, do a few stretches or light exercises to prepare your body and brain for work.

4. Silence Your Cell Phone

Interruptions from your phone are notorious for breaking your concentration. If you pull away to check a notification, you’ll have to refocus your brain before diving back into your studies.

Consider turning off your phone’s sounds or putting your device into do not disturb mode before you start. You can also download apps to temporarily block your access to social media .

If you’re still tempted to check your device, simply power it off until you’re finished studying.

Research shows that stress makes it harder to learn and to retain information.

Stress-busting ideas include:

- Taking deep breaths

- Writing down a list of tasks you need to tackle

- Doing light exercise

Try to clear your head before you begin studying.

Part 2 – Create Your Perfect Study Space

1. Pick a Good Place to Study

There’s a delicate balance when it comes to the best study spot : You need a place that’s comfortable without being so relaxing that you end up falling asleep. For some people, that means working at a desk. Others do better on the couch or at the kitchen table. Your bed, on the other hand, may be too comfy.

Surrounding yourself with peace and quiet helps you focus. If your kids are being loud or there’s construction going on outside your window, you might need to relocate to an upstairs bedroom, a quiet cafe or your local library.

2. Choose Your Music Wisely

Noise-canceling headphones can also help limit distractions.

It’s better to listen to quiet music than loud tunes. Some people do best with instrumental music playing in the background.

Songs with lyrics may pull your attention away from your textbooks. However, some folks can handle listening to songs with words, so you may want to experiment and see what works for you.

Just remember that there’s no pressure to listen to any music. If you do your best work in silence, then feel free to turn your music player off.

3. Turn Off Netflix

If song lyrics are distracting, just imagine what an attention sucker the television can be! Serious studying requires that you turn off the TV.

The same goes for listening to radio deejays. Hearing voices in the background takes your brainpower off of your studies.

4. Use Background Sounds

Turning off the television, talk radio and your favorite pop song doesn’t mean that you have to study in total silence. Soft background sounds are a great alternative.

Some people enjoy listening to nature sounds, such as ocean waves or cracks of thunder. Others prefer the whir of a fan.

5. Snack on Brain Food

A growling stomach can pull your mind from your studies, so feel free to snack as you work. Keep your snacks within arm’s reach, so you don’t have to leave your books to find food.

Fuel your next study session with some of the following items:

- Lean deli meat

- Grapes or apple slices

- Dark chocolate

Go for snacks that will power your brain and keep you alert. Steer clear of items that are high in sugar, fat and processed carbs.

Part 3 – Pick a Study Method That Works for You

Mindlessly reading through your notes or textbooks isn’t an effective method of studying; it doesn’t help you process the information. Instead, you should use a proven study strategy that will help you think through the material and retain the information.

Strategy #1 – SQ3R Method

With the SQ3R approach to reading , you’ll learn to think critically about a text.

There are five steps:

- Survey : Skim through the assigned material. Focus on headings, words in bold print and any diagrams.

- Question : Ask yourself questions related to the topic.

- Read : Read the text carefully. As you go, look for answers to your questions.

- Recite : Tell yourself the answers to your questions. Write notes about them, even.

- Review : Go over the material again by rereading the text and reading your notes aloud.

Strategy #2 – PQ4R Method

PQ4R is another study strategy that can help you digest the information you read.

This approach has six steps:

- Preview : Skim the material. Read the titles, headings and other highlighted text.

- Question : Think through questions that pertain to the material.

- Read : As you work through the material, try to find answers to your questions.

- Reflect : Consider whether you have any unanswered questions or new questions.

- Recite : Speak aloud about the things you just read.

- Review : Look over the material one more time.

Strategy #3 – THIEVES Method

The THIEVES approach can help you prepare to read for information.

There are seven pre-reading steps:

- Title : Read the title.

- Headings : Look through the headings.

- Introduction : Skim the intro.

- Every first sentence in a section : Take a look at how each section begins.

- Visuals and vocabulary : Look at the pictures and the words in bold print.

- End questions : Review the questions at the end of the chapter.

- Summary : Read the overview of the text.

Ask yourself thought-provoking questions as you work through these steps. After completing them, read the text.

Studying Online

Although these three study strategies can be useful in any setting, studying online has its own set of challenges.

Dr. Tony Bates has written a thoughtful and thorough guide to studying online, A Student Guide to Studying Online . Not only does he highlight the importance of paying attention to course design, but he also offers helpful tips on how to choose the best online program and manage your course load.

Part 4 – Effective Study Skills

1. Highlight Key Concepts

Looking for the most important information as you read helps you stay engaged with the material . This can help keep your mind from wandering as you read.

As you find important details, mark them with a highlighter, or underline them. It can also be effective to jot notes along the edges of the text. Write on removable sticky notes if the book doesn’t belong to you.

When you’re preparing for a test, begin your studies by reviewing your highlighted sections and the notes you wrote down.

2. Summarize Important Details

One good way to get information to stick in your brain is to tell it again in your own words. Writing out a summary can be especially effective. You can organize your summaries in paragraph form or in outline form.

Keep in mind that you shouldn’t include every bit of information in a summary. Stick to the key points.

Consider using different colors on your paper. Research shows that information presented in color is more memorable than things written in plain type. You could use colored pens or go over your words with highlighters.

After writing about what you read, reinforce the information yet again by reading aloud what you wrote on your paper.

3. Create Your Own Flashcards

For an easy way to quiz yourself , prepare notecards that feature a keyword on one side and important facts or definitions about that topic on the reverse.

Writing out the cards will help you learn the information. Quizzing yourself on the cards will continue that reinforcement.

The great thing about flashcards is that they’re easily portable. Slip them in your bag, so you can pull them out whenever you have a spare minute. This is a fantastic way to squeeze in extra practice time outside of your regularly scheduled study sessions.

As an alternative to paper flashcards, you can also use a computer program or a smartphone app to make digital flashcards that you can click through again and again.

4. Improve Recall with Association

Sometimes your brain could use an extra hand to help you hold onto the information that you’re studying. Creating imaginary pictures, crafting word puzzles or doing other mental exercises can help make your material easier to remember.

Try improving recall with the following ideas:

- Sing the information to a catchy tune.

- Think of a mnemonic phrase in which the words start with the same letters as the words that you need to remember.

- Draw a picture that helps you make a humorous connection between the new information and the things that you already know.

- Envision what it would be like to experience your topic in person. Imagine the sights, sounds, smells and more.

- Think up rhymes or tongue twisters that can help the information stick in your brain.

- Visualize the details with a web-style mind map that illustrates the relationships between concepts.

5. Absorb Information in Smaller Chunks

Think about how you memorize a phone number: You divide the 10-digit number into three smaller groups. It’s easier to get these three chunks to stick in your mind than it is to remember the whole thing as a single string of information.

You can use this strategy when studying by breaking a list down into smaller parts. Work on memorizing each part as its own group.

6. Make Your Own Study Sheet

Condensing your most important notes onto one page is an excellent way to keep priority information at your fingertips. The more you look over this sheet and read it aloud, the better that you’ll know the material.

Furthermore, the act of typing or writing out the information will help you memorize the details. Using different colors or lettering styles can help you picture the information later.

Just like flashcards, a study sheet is portable. You can pull it out of your bag whenever you have a spare minute.

7. Be the Teacher

To teach information to others, you first have to understand it yourself. Therefore, when you’re trying to learn something new, challenge yourself to consider how you’d teach it to someone else. Wrestling with this concept will help you gain a better understanding of the topic.

In fact, you can even recruit a friend, a family member or a study group member to listen to your mini-lesson. Reciting your presentation aloud to someone else will help the details stick in your mind, and your audience may be able to point out gaps in your knowledge.

8. Know When to Call It a Day

Yes, you really can get too much of a good thing. Although your studies are important, they shouldn’t be the only thing in your life. It’s also important to have a social life, get plenty of exercise, and take care of your non-school responsibilities.

Studies show that too much time with your nose in the books can elevate your stress level , which can have a negative effect on your school performance and your personal relationships.

Too much studying may also keep you from getting enough exercise. This could lower your bone density or increase your percentage of body fat.

Part 5 – How to Study More Efficiently

1. Take Regular Breaks

Study sessions will be more productive if you allow yourself to take planned breaks. Consider a schedule of 50 minutes spent working followed by a 10-minute break.

Your downtime provides a good chance to stand up and stretch your legs. You can also use this as an opportunity to check your phone or respond to emails. When your 10 minutes are up, however, it’s time to get back to work.

At the end of a long study session, try to allow yourself a longer break — half an hour, perhaps — before you move on to other responsibilities.

2. Take Notes in Class

The things that your teacher talks about in class are most likely topics that he or she feels are quite important to your studies. So, it’s a good idea to become a thorough note-taker.

The following tips can help you become an efficient, effective note-taker:

- Stick to the main points.

- Use shorthand when possible.

- If you don’t have time to write all the details, jot down a keyword or a name. After class, you can use your textbook to elaborate on these items.

- For consistency, use the same organizational system each time you take notes.

- Consider writing your notes by hand, which can help you remember the information better. However, typing may help you be faster or more organized.

Recording important points is effective because it forces you to pay attention to what’s being said during a lecture.

3. Exercise First

Would you believe that exercise has the potential to grow your brain ? Scientists have shown this to be true!

In fact, exercise is most effective at generating new brain cells when it’s immediately followed by learning new information.

There are short-term benefits to exercising before studying as well. Physical activity helps wake you up so you feel alert and ready when you sit down with your books.

4. Review and Revise Your Notes at Home

If your notes are incomplete — for example, you wrote down dates with no additional information — take time after class to fill in the missing details. You may also want to swap notes with a classmate so you can catch things that you missed during the lecture.

- Rewrite your notes if you need to clean them up

- Rewriting will help you retain the information

- Add helpful diagrams or pictures

- Read through them again within one day

If you find that there are concepts in your notes that you don’t understand, ask your professor for help. You may be able to set up a meeting or communicate through email.

After rewriting your notes, put them to good use by reading through them again within the next 24 hours. You can use them as a reference when you create study sheets or flashcards.

5. Start with Your Toughest Assignments

Let’s face it: There are some subjects that you like more than others. If you want to do things the smart way, save your least challenging tasks for the end of your studies. Get the hardest things done first.

If you save the toughest tasks for last, you’ll have them hanging over your head for the whole study session. That can cost you unnecessary mental energy.

Furthermore, if you end with your favorite assignments, it will give you a more positive feeling about your academic pursuits. You’ll be more likely to approach your next study session with a good attitude.

6. Focus on Key Vocabulary

To really understand a subject, you have to know the words that relate to it. Vocabulary words are often written in textbooks in bold print. As you scan the text, write these words down in a list.

Look them up in a dictionary or in the glossary at the back of the book. To help you become familiar with the terms, you could make a study sheet with the definitions or make flashcards.

7. Join a Study Group

Studying doesn’t always have to be an individual activity.

Benefits of a study group include:

- Explaining the material to one another

- Being able to ask questions about things you don’t understand

- Quizzing each other or playing review games

- Learning the material more quickly than you might on your own

- Developing soft skills that will be useful in your career, such as teamwork and problem solving

- Having fun as you study

Gather a few classmates to form a study group.

Part 6 – How to Study for Tests

1. Study for Understanding, Not Just for the Test

Cramming the night before a big test usually involves trying to memorize information long enough to be able to regurgitate it the next morning. Although that might help you get a decent grade or your test, it won’t help you really learn the material .

Within a day or two, you’ll have forgotten most of what you studied. You’ll have missed the goal of your classes: mastery of the subject matter.

Instead, commit yourself to long-term learning by studying throughout the semester.

2. Begin Studying at Least One Week in Advance

Of course, you may need to put in extra time before a big test, but you shouldn’t put this off until the night before.

Instead, in the week leading up to the exam, block off a daily time segment for test preparation. Regular studying will help you really learn the material.

3. Spend at Least One Hour per Day Studying

One week out from a big test, study for an hour per night. If you have two big tests coming up, increase your daily study time, and divide it between the two subjects.

The day before the exam, spend as much time as possible studying — all day, even.

4. Re-write Class Notes

After each class, you should have fleshed out your notes and rewritten them in a neat, organized format. Now, it’s time to take your re-done notes and write them once again.

This time, however, your goal is to condense them down to only the most important material. Ideally, you want your rewritten notes to fit on just one or two sheets of paper.

These sheets should be your main study resource during test preparation.

5. Create a Study Outline

Early in the week, make a long outline that includes many of the details from your notes. Rewrite it a few days later, but cut the material in half.

Shortly before the test, write it one more time; include only the most important information. Quiz yourself on the missing details.

6. Make Your Own Flashcards

Another way to quiz yourself is to make flashcards that you can use for practice written tests.

First, read the term on the front side. Encourage yourself to write out the definition or details of that term. Compare your written answer with what’s on the back of the card.

This can be extra helpful when prepping for an entrance exam like the GRE, though there are a growing number of schools that don’t require GRE scores for admission.

7. Do Sample Problems and Essays from Your Textbook

There are additional things you can do to practice test-taking. For example, crack open your book, and solve problems like the ones you expect to see on the test.

Write out the answers to essay questions as well. There may be suggested essay topics in your textbook.

Part 7 – Memory Improvement Techniques

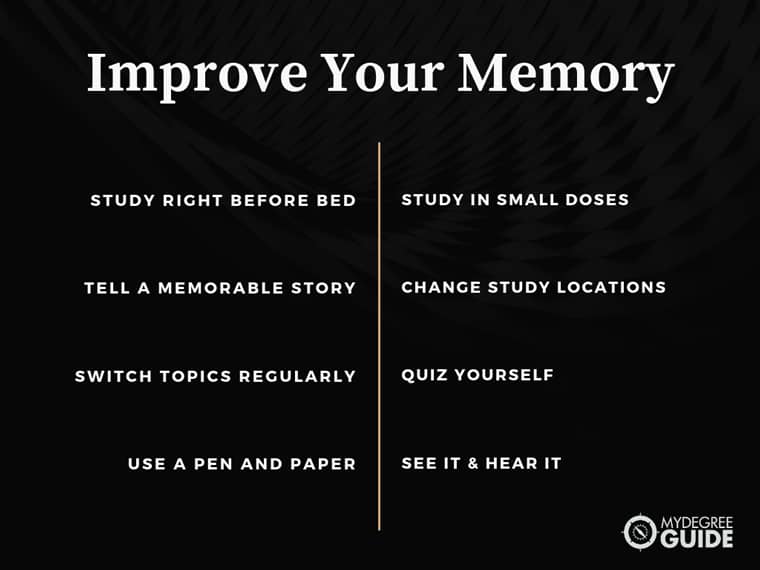

1. Study Right Before Bed

Although you shouldn’t pull all-nighters, studying right before bedtime can be a great idea.

Sleep helps cement information in your brain. Studies show that you’re more likely to recall information 24 hours later if you went to bed shortly after learning it.

Right before bed, read through your study sheet, quiz yourself on flashcards or recite lists of information.

2. Study Small Chunks at a Time

If you want to remember information over the long haul, don’t try to cram it all in during one sitting.

Instead, use an approach called spaced repetition :

- Break the information into parts

- Learn one new part at a time over the course of days or weeks

- Review your earlier acquisitions each time you study

The brain stores information that it thinks is important. So, when you regularly go over a topic at set intervals over time, it strengthens your memory of it.

3. Tell a Story

Sometimes, you just need to make information silly in order to help it stick in your brain.

To remember a list of items or the particular order of events, make up a humorous story that links those things or words together. It doesn’t necessarily need to make sense; it just needs to be memorable .

4. Change Study Locations Often

Studying the same information in multiple places helps the details stick in your mind better.

Consider some of the following locations:

- Your desk at home

- A coffee shop

- The library

- Your backyard

It’s best to switch between several different study spots instead of always hitting the books in the same place.

5. Swap Topics Regularly

Keeping your brain trained on the same information for long periods of time isn’t beneficial. It’s smarter to jump from one subject to another a few times during a long study session.

Along those same lines, you should study the same material in multiple ways. Research shows that using varied study methods for the same topic helps you perform better on tests.

6. Quiz Yourself

Challenge yourself to see what you can remember. Quizzing yourself is like practicing for the test, and it’s one of the most effective methods of memory retention .

If it’s hard to remember the information at first, don’t worry; the struggle makes it more likely that you’ll remember it in the end.

7. Go Old-school: Use a Pen and Paper

The act of writing answers helps you remember the information. Here are some ways to use writing while studying:

- Recopy your notes

- Write the answers to flashcards

- Make a study sheet

- Practice writing essay answers

Writing by hand is best because it requires your attention and focus.

8. See It & Hear It

Say information out loud, and you’ll be more likely to remember it. You’re engaging your eyes as you read the words, your mouth as you say them, and your ears as you hear yourself.

Scientists call the benefit of speaking information aloud production effect .

Part 8 – Top 10 Study Hacks Backed by Science

1. Grab a Coffee

Drinking coffee (or your preferred high-octane beverage) while you study may help keep you alert so you don’t doze off mid-session. There’s even evidence that caffeine can improve your memory skills.

However, avoid sugary beverages. These could cause your energy level to crash in a few hours.

2. Reward Yourself

Studies show that giving yourself a reward for doing your work helps you enjoy the effort more.

Do it right away; don’t wait until the test is over to celebrate. For example, after finishing a three-hour study session, treat yourself to an ice cream cone or a relaxing bath.

3. Study with Others

Working with a study group holds you accountable so it’s harder to procrastinate on your work.

When you study together, you can fill in gaps in one another’s understanding, and you can quiz each other on the material.

Besides, studying with a group can be fun!

4. Meditate

It may be hard to imagine adding anything else to your packed schedule, but dedicating time to mindfulness practices can really pay off.

Studies show that people who meditate may perform better on tests , and they are generally more attentive.

Mindfulness apps can help you get started with this practice.

5. Hit the Gym

To boost the blood flow to your brain, do half an hour of cardio exercise before sitting down to study.

Aerobic exercise gives your brain a major dose of oxygen and other important nutrients, which may help you think clearly, remember facts and do your best work.

6. Play Some Music

Listening to tunes can help you focus. Studies show that the best study music is anything that features a rhythmic beat .

It’s smart to choose a style that you like. If you like classical, that’s fine, but you could also go for electronica or modern piano solos.

7. Grab Some Walnuts

A diet rich in omega-3 fatty acids helps your brain do its best work.

Good sources include:

- Fish: cod liver oil, salmon and mackerel

- Vegetables: spinach and Brussels sprouts

To calm your pre-test jitters, eat a mix of omega-3 and omega-6 foods.

8. Take Regular Breaks

Your brain needs some downtime. Don’t try to push through for hours on end. Every hour, take a break for several minutes.

Breaks are good for your mental health . They also improve your attention span, your creativity and your productivity.

During a break, it’s best to move around and exercise a bit.

9. Get Some Sleep

Although studying is important, it can’t come at the expense of your rest. Sleep gives your brain a chance to process the information that you’ve learned that day.

If you don’t get enough sleep, you’ll have a hard time focusing and remembering information.

Even during busy test weeks, try to get seven to nine hours of sleep each night.

10. Eliminate Distractions

It’s hard to get much studying done when you’re busy scrolling Instagram. Put away your phone and computer while studying, or at least block your social media apps.

Turn off the television while you work, too.

If you’re studying in a noisy area, put on headphones that can help block the distracting sounds.

Part 9 – The Best Study Apps

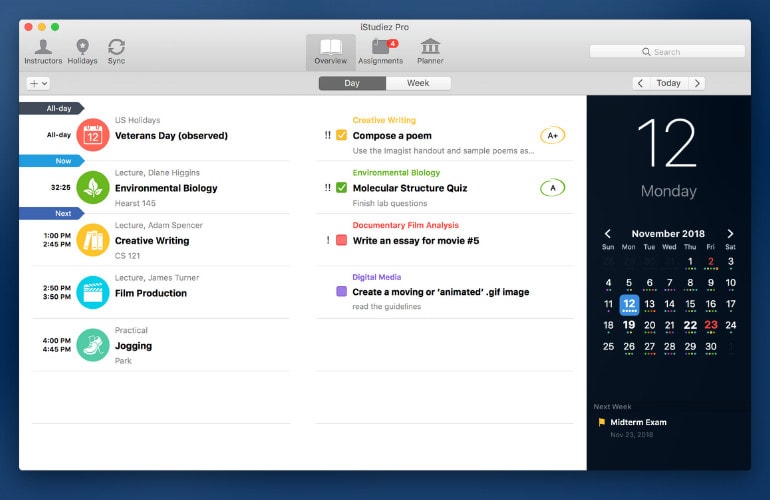

1. iStudiez Pro Legend

Scheduling study time is a must, and iStudiez Pro Legend lets you put study sessions, classes and assignments on your calendar. Color coding the entries can help you stay organized.

For each class, you can enter meeting times and homework assignments, and you can keep track of your grades.

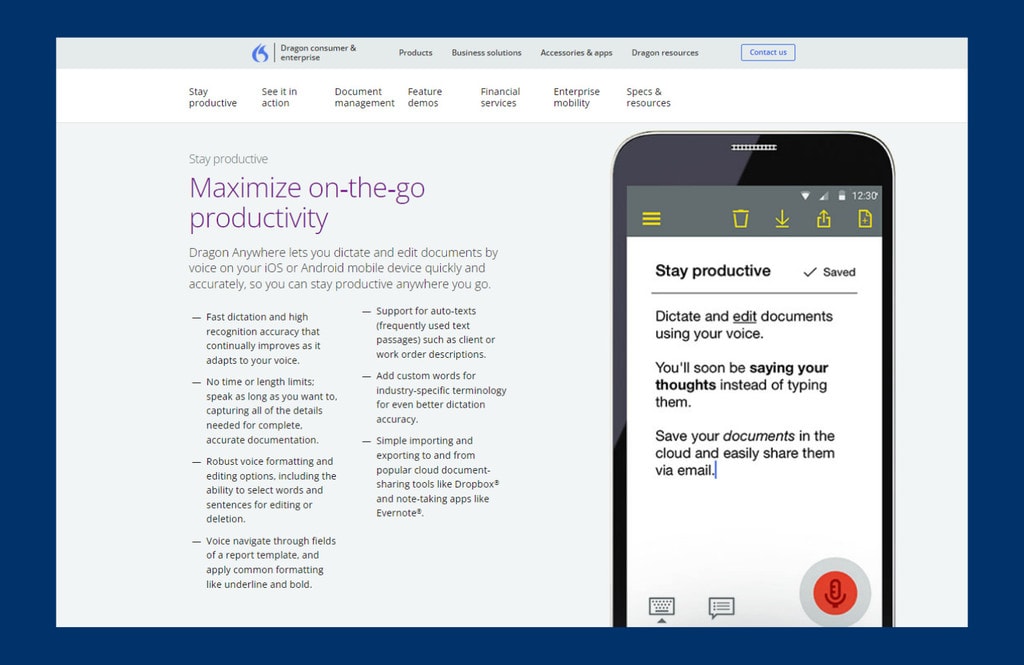

2. Dragon Anywhere

Instead of writing notes in the margins of your textbooks, you can use Dragon Anywhere’s voice dictation feature to record your thoughts and insights.

Just be sure to rewrite your dictated notes in your own handwriting later for maximum learning!

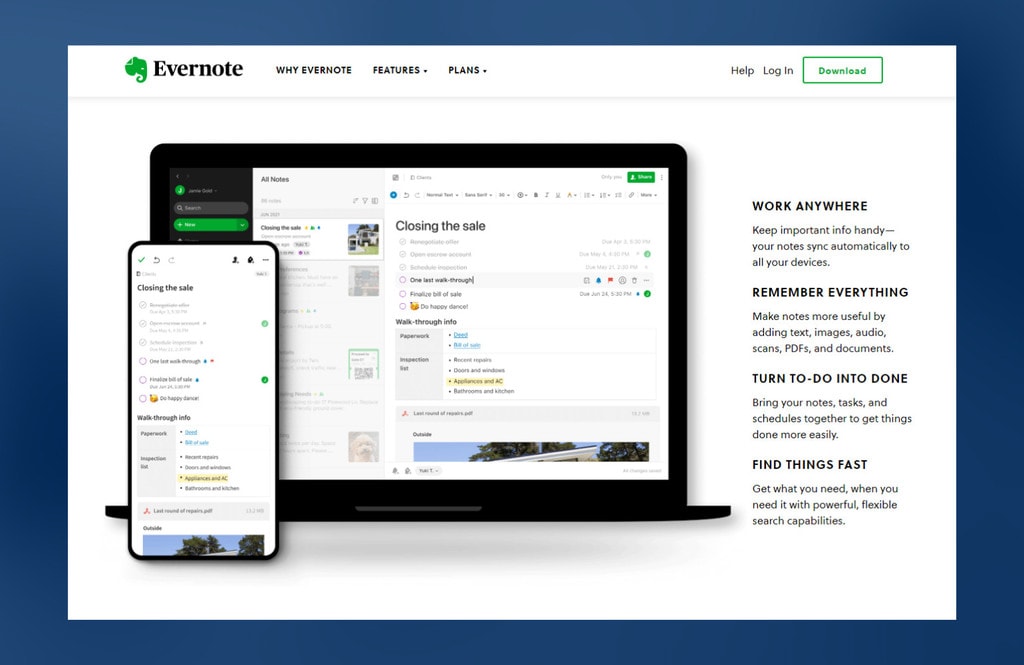

3. Evernote

When you’re in school, you have a lot of responsibilities to juggle, but Evernote can help you organize them.

You can add notes and documents to store them in one digital spot, and tagging them will help you quickly pull up all files for a class or a topic.

4. Quizlet Go

Make digital flashcards that you can practice on your mobile device with Quizlet Go .

This means that you can pull out your phone for a quick study session whenever you have a couple of minutes of downtime. You don’t even need internet access to practice these flashcards.

5. My Study Life

Enter your upcoming tests and assignments into My Study Life , and the app will send you reminder messages.

The app has a calendar so you can keep track of your class schedule. It can even notify you when it’s time to go to class.

6. Exam Countdown Lite

You should start studying for tests at least a week in advance. Input the dates for your exams and assignments into Exam Countdown Lite so you’ll have a visual reminder of when you should begin your test prep.

The app can send you notifications as well.

7. Flashcards+

With Chegg’s Flashcards+ , you can make your own digital flashcards or use ones designed by others.

Because you can add images to your cards, you can quiz yourself on the names of famous artworks, important historical artifacts or parts of a scientific diagram.

Organize information into categories by creating a visual mind map on XMind . This can help you classify facts and figures so you see how they relate to one another.

This visual representation can also help you recall the information later.

9. ScannerPro

Do you have piles of handwritten notes everywhere? Once you have written them out, consider scanning them into digital form. ScannerPro lets you use your phone as a scanner.

You can store your scanned files in this app or transfer them to Evernote or another organization system.

Part 10 – Study Skills Worksheets

Could you use more help to develop your study skills? Rutgers University has dozens of study skills worksheets online .

These documents are packed with tips that can help you become a better student. The checklists and charts can help you evaluate your current strengths and organize your work.

Part 11 – Key Takeaways

You’re a busy person, so you need to make the most of every study session.

By now, you should understand the basics of effective studies:

- Schedule study time

- Study regularly

- Minimize distractions

- Read for information

- Write the important stuff down

- Use creative memory tricks

- Quiz yourself

- Be good to your body and your brain

Put these study tips to good use, and you’ll soon learn that you’ve learned how to study smarter.

Essay and dissertation writing skills

Planning your essay

Writing your introduction

Structuring your essay

- Writing essays in science subjects

- Brief video guides to support essay planning and writing

- Writing extended essays and dissertations

- Planning your dissertation writing time

Structuring your dissertation

- Top tips for writing longer pieces of work

Advice on planning and writing essays and dissertations

University essays differ from school essays in that they are less concerned with what you know and more concerned with how you construct an argument to answer the question. This means that the starting point for writing a strong essay is to first unpick the question and to then use this to plan your essay before you start putting pen to paper (or finger to keyboard).

A really good starting point for you are these short, downloadable Tips for Successful Essay Writing and Answering the Question resources. Both resources will help you to plan your essay, as well as giving you guidance on how to distinguish between different sorts of essay questions.

You may find it helpful to watch this seven-minute video on six tips for essay writing which outlines how to interpret essay questions, as well as giving advice on planning and structuring your writing:

Different disciplines will have different expectations for essay structure and you should always refer to your Faculty or Department student handbook or course Canvas site for more specific guidance.

However, broadly speaking, all essays share the following features:

Essays need an introduction to establish and focus the parameters of the discussion that will follow. You may find it helpful to divide the introduction into areas to demonstrate your breadth and engagement with the essay question. You might define specific terms in the introduction to show your engagement with the essay question; for example, ‘This is a large topic which has been variously discussed by many scientists and commentators. The principal tension is between the views of X and Y who define the main issues as…’ Breadth might be demonstrated by showing the range of viewpoints from which the essay question could be considered; for example, ‘A variety of factors including economic, social and political, influence A and B. This essay will focus on the social and economic aspects, with particular emphasis on…..’

Watch this two-minute video to learn more about how to plan and structure an introduction:

The main body of the essay should elaborate on the issues raised in the introduction and develop an argument(s) that answers the question. It should consist of a number of self-contained paragraphs each of which makes a specific point and provides some form of evidence to support the argument being made. Remember that a clear argument requires that each paragraph explicitly relates back to the essay question or the developing argument.

- Conclusion: An essay should end with a conclusion that reiterates the argument in light of the evidence you have provided; you shouldn’t use the conclusion to introduce new information.

- References: You need to include references to the materials you’ve used to write your essay. These might be in the form of footnotes, in-text citations, or a bibliography at the end. Different systems exist for citing references and different disciplines will use various approaches to citation. Ask your tutor which method(s) you should be using for your essay and also consult your Department or Faculty webpages for specific guidance in your discipline.

Essay writing in science subjects

If you are writing an essay for a science subject you may need to consider additional areas, such as how to present data or diagrams. This five-minute video gives you some advice on how to approach your reading list, planning which information to include in your answer and how to write for your scientific audience – the video is available here:

A PDF providing further guidance on writing science essays for tutorials is available to download.

Short videos to support your essay writing skills

There are many other resources at Oxford that can help support your essay writing skills and if you are short on time, the Oxford Study Skills Centre has produced a number of short (2-minute) videos covering different aspects of essay writing, including:

- Approaching different types of essay questions

- Structuring your essay

- Writing an introduction

- Making use of evidence in your essay writing

- Writing your conclusion

Extended essays and dissertations

Longer pieces of writing like extended essays and dissertations may seem like quite a challenge from your regular essay writing. The important point is to start with a plan and to focus on what the question is asking. A PDF providing further guidance on planning Humanities and Social Science dissertations is available to download.

Planning your time effectively

Try not to leave the writing until close to your deadline, instead start as soon as you have some ideas to put down onto paper. Your early drafts may never end up in the final work, but the work of committing your ideas to paper helps to formulate not only your ideas, but the method of structuring your writing to read well and conclude firmly.

Although many students and tutors will say that the introduction is often written last, it is a good idea to begin to think about what will go into it early on. For example, the first draft of your introduction should set out your argument, the information you have, and your methods, and it should give a structure to the chapters and sections you will write. Your introduction will probably change as time goes on but it will stand as a guide to your entire extended essay or dissertation and it will help you to keep focused.

The structure of extended essays or dissertations will vary depending on the question and discipline, but may include some or all of the following:

- The background information to - and context for - your research. This often takes the form of a literature review.

- Explanation of the focus of your work.

- Explanation of the value of this work to scholarship on the topic.

- List of the aims and objectives of the work and also the issues which will not be covered because they are outside its scope.

The main body of your extended essay or dissertation will probably include your methodology, the results of research, and your argument(s) based on your findings.

The conclusion is to summarise the value your research has added to the topic, and any further lines of research you would undertake given more time or resources.

Tips on writing longer pieces of work

Approaching each chapter of a dissertation as a shorter essay can make the task of writing a dissertation seem less overwhelming. Each chapter will have an introduction, a main body where the argument is developed and substantiated with evidence, and a conclusion to tie things together. Unlike in a regular essay, chapter conclusions may also introduce the chapter that will follow, indicating how the chapters are connected to one another and how the argument will develop through your dissertation.

For further guidance, watch this two-minute video on writing longer pieces of work .

Systems & Services

Access Student Self Service

- Student Self Service

- Self Service guide

- Registration guide

- Libraries search

- OXCORT - see TMS

- GSS - see Student Self Service

- The Careers Service

- Oxford University Sport

- Online store

- Gardens, Libraries and Museums

- Researchers Skills Toolkit

- LinkedIn Learning (formerly Lynda.com)

- Access Guide

- Lecture Lists

- Exam Papers (OXAM)

- Oxford Talks

Latest student news

CAN'T FIND WHAT YOU'RE LOOKING FOR?

Try our extensive database of FAQs or submit your own question...

Ask a question

- Tips for Reading an Assignment Prompt

- Asking Analytical Questions

- Introductions

- What Do Introductions Across the Disciplines Have in Common?

- Anatomy of a Body Paragraph

- Transitions

- Tips for Organizing Your Essay

- Counterargument

- Conclusions

- Strategies for Essay Writing: Downloadable PDFs

- Brief Guides to Writing in the Disciplines

Choose Your Test

Sat / act prep online guides and tips, how to study for a test: 17 expert tips.

Other High School

Do you have a big exam coming up, but you're not sure how to prepare for it? Are you looking to improve your grades or keep them strong but don't know the best way to do this? We're here to help! In this guide, we've compiled the 17 best tips for how to study for a test. No matter what grade you're in or what subject you're studying, these tips will give you ways to study faster and more effectively. If you're tired of studying for hours only to forget everything when it comes time to take a test, follow these tips so you can be well prepared for any exam you take.

How to Study for a Test: General Tips

The four tips below are useful for any test or class you're preparing for. Learn the best way to study for a test from these tips and be prepared for any future exams you take.

#1: Stick to a Study Schedule

If you're having trouble studying regularly, creating a study schedule can be a huge help. Doing something regularly helps your mind get used to it. If you set aside a time to regularly study and stick to it, it'll eventually become a habit that's (usually) easy to stick to. Getting into a fixed habit of studying will help you improve your concentration and mental stamina over time. And, just like any other training, your ability to study will improve with time and effort.

Take an honest look at your schedule (this includes schoolwork, extracurriculars, work, etc.) and decide how often you can study without making your schedule too packed. Aim for at least an hour twice a week. Next, decide when you want to study, such as Tuesdays, Thursdays, and Sundays from 7-8pm, and stick to your schedule . In the beginning, you may need to tweak your schedule, but you'll eventually find the study rhythm that works best for you. The important thing is that you commit to it and study during the same times each week as often as possible.

#2: Start Studying Early and Study for Shorter Periods

Some people can cram for several hours the night before the test and still get a good grade. However, this is rarer than you may hope. Most people need to see information several times, over a period of time, for them to really commit it to memory. This means that, instead of doing a single long study session, break your studying into smaller sessions over a longer period of time. Five one-hour study sessions over a week will be less stressful and more effective than a single five-hour cram session. It may take a bit of time for you to learn how long and how often you need to study for a class, but once you do you'll be able to remember the information you need and reduce some of the stress that comes from schoolwork, tests, and studying.

#3: Remove Distractions

When you're studying, especially if it's for a subject you don't enjoy, it can be extremely tempting to take "quick breaks" from your work. There are untold distractions all around us that try to lure our concentration away from the task at hand. However, giving in to temptation can be an awful time suck. A quick glance at your phone can easily turn into an hour of wasting time on the internet, and that won't help you get the score you're looking for. In order to avoid distractions, remove distractions completely from your study space.

Eat a meal or a snack before you begin studying so you're not tempted to rummage through the fridge as a distraction. Silence your phone and keep it in an entirely different room. If you're studying on a computer, turn your WIFI off if it's not essential to have. Make a firm rule that you can't get up to check on whatever has you distracted until your allotted study time is up.

#4: Reward Yourself When You Hit a Milestone

To make studying a little more fun, give yourself a small reward whenever you hit a study milestone. For example, you might get to eat a piece of candy for every 25 flashcards you test yourself on, or get to spend 10 minutes on your phone for every hour you spend studying. You can also give yourself larger rewards for longer-term goals, such as going out to ice cream after a week of good study habits. Studying effectively isn't always easy, and by giving yourself rewards, you'll keep yourself motivated.

Our pets are not the only ones who deserve rewards.

Tips for Learning and Remembering Information

While the default method of studying is reading through class notes, this is actually one of the least effective ways of learning and remembering information. In this section we cover four much more useful methods. You'll notice they all involve active learning, where you're actively reworking the material, rather than just passively reading through notes. Active studying has been shown to be a much more effective way to understand and retain information, and it's what we recommend for any test you're preparing for.

#5: Rewrite the Material in Your Own Words

It can be easy to get lost in a textbook and look back over a page, only to realize you don't remember anything about what you just read. Fortunately, there's a way to avoid this.

For any class that requires lots of reading, be sure to stop periodically as you read. Pause at the end of a paragraph/page/chapter (how much you can read at once and still remember clearly will likely depend on the material you're reading) and—without looking!—think about what the text just stated. Re-summarize it in your own words, and write down bullet points if that helps. Now, glance back over the material and make sure you summarized the information accurately and included all the important details. Take note of whatever you missed, then pick up your reading where you left off.

Whether you choose to summarize the text aloud or write down notes, re-wording the text is a very effective study tool. By rephrasing the text in your own words, you're ensuring you're actually remembering the information and absorbing its meaning, rather than just moving your eyes across a page without taking in what you're reading.

#6: Make Flashcards

Flashcards are a popular study tool for good reason! They're easy to make, easy to carry around, easy to pull out for a quick study session, and they're a more effective way of studying than just reading through pages of notes. Making your own flashcards is especially effective because you'll remember more information just through the act of writing it down on the cards. For any subjects in which you must remember connections between terms and information, such as formulas, vocabulary, equations, or historical dates, flashcards are the way to go. We recommend using the Waterfall Method when you study with flashcards since it's the fastest way to learn all the material on the cards.

#7: Teach the Material to Someone Else

Teaching someone else is a great way to organize the information you've been studying and check your grasp of it. It also often shows you that you know more of the material than you think! Find a study-buddy, or a friend/relative/pet or even just a figurine or stuffed animal and explain the material to them as if they're hearing about it for the first time. Whether the person you're teaching is real or not, teaching material aloud requires you to re-frame the information in new ways and think more carefully about how all the elements fit together. The act of running through the material in this new way also helps you more easily lock it in your mind.

#8: Make Your Own Study Guides

Even if your teacher provides you with study guides, we highly recommend making your own study materials. Just making the materials will help the information sink into your mind, and when you make your own study guides, you can customize them to the way you learn best, whether that's flashcards, images, charts etc. For example, if you're studying for a biology test, you can draw your own cell and label the components, make a Krebs cycle diagram, map out a food chain, etc. If you're a visual learner (or just enjoy adding images to your study materials), include pictures and diagrams.

Sometimes making your own charts and diagrams will mean recreating the ones in your textbook from memory, and sometimes it will mean putting different pieces of information together yourself. Whatever the diagram type and whatever the class, writing your information down and making pictures out of it will be a great way to help you remember the material.

How to Study for a History Test

History tests are notorious for the amount of facts and dates you need to know. Make it easier to retain the information by using these two tips.

#9: Know Causes and Effects

It's easy and tempting to simply review long lists of dates of important events, but this likely won't be enough for you to do well on a history test, especially if it has any writing involved. Instead of only learning the important dates of, say, WWI, focus on learning the factors that led to the war and what its lasting impacts on the world were. By understanding the cause and effects of major events, you'll be able to link them to the larger themes you're learning in history class. Also, having more context about an event can often make it easier to remember little details and dates that go along with it.

#10: Make Your Own Timelines

Sometimes you need to know a lot of dates for a history test. In these cases, don't think passively reading your notes is enough. Unless you have an amazing memory, it'll take you a long time for all those dates to sink into your head if you only read through a list of them. Instead, make your own timeline.

Make your first timeline very neat, with all the information you need to know organized in a way that makes sense to you (this will typically be chronologically, but you may also choose to organize it by theme). Make this timeline as clear and helpful as you can, using different colors, highlighting important information, drawing arrows to connecting information, etc. Then, after you've studied enough to feel you have a solid grasp of the dates, rewrite your timeline from memory. This one doesn't have to be neat and organized, but include as much information as you remember. Continue this pattern of studying and writing timelines from memory until you have all the information memorized.

Know which direction events occur in to prepare for history tests.

How to Study for a Math Test

Math tests can be particularly intimating to many students, but if you're well-prepared for them, they're often straightforward.

#11: Redo Homework Problems

More than most tests, math tests usually are quite similar to the homework problems you've been doing. This means your homework contains dozens of practice problems you can work through. Try to review practice problems from every topic you'll be tested on, and focus especially on problems that you struggled with. Remember, don't just review how you solved the problem the first time. Instead, rewrite the problem, hide your notes, and solve it from scratch. Check your answer when you're finished. That'll ensure you're committing the information to memory and actually have a solid grasp of the concepts.

#12: Make a Formula Sheet

You're likely using a lot of formulas in your math class, and it can be hard remembering what they are and when to use them. Throughout the year, as you learn a new important formula, add it to a formula sheet you've created. For each formula, write out the formula, include any notes about when to use it, and include a sample problem that uses the formula. When your next math test rolls around, you'll have a useful guide to the key information you've been learning.

How to Study for an English Test

Whether your English test involves writing or not, here are two tips to follow as you prepare for it.

#13: Take Notes as You Read

When you're assigned reading for English class, it can be tempting to get through the material as quickly as possible and then move on to something else. However, this is not a good way to retain information, and come test day, you may be struggling to remember a lot of what you read. Highlighting important passages is also too passive a way to study. The way to really retain the information you read is to take notes. This takes more time and effort, but it'll help you commit the information to memory. Plus, when it comes time to study, you'll have a handy study guide ready and won't have to frantically flip through the book to try to remember what you read. The more effort you put into your notes, the more helpful they'll be. Consider organizing them by theme, character, or however else makes sense to you.

#14: Create Sample Essay Outlines

If the test you're taking requires you to write an essay, one of the best ways to be prepared is to develop essay outlines as you study. First, think about potential essay prompts your teacher might choose you to write about. Consider major themes, characters, plots, literary comparisons, etc., you discussed in class, and write down potential essay prompts. Just doing this will get you thinking critically about the material and help you be more prepared for the test.

Next, write outlines for the prompts you came up with (or, if you came up with a lot of prompts, choose the most likely to outline). These outlines don't need to contain much information, just your thesis and a few key points for each body paragraph. Even if your teacher chooses a different prompt than what you came up with, just thinking about what to write about and how you'll organize your thoughts will help you be more prepared for the test.

Fancy pen and ink not required to write essay outlines.

What to Do the Night Before the Test

Unfortunately, the night before a test is when many students make study choices that actually hurt their chances of getting a good grade. These three tips will help you do some final review in a way that helps you be at the top of your game the next day.

#15: Get Enough Sleep

One of the absolute best ways to prepare for a test-any test-is to be well-rested when you sit down to take it. Staying up all night cramming information isn't an effective way of studying, and being tired the next day can seriously impact your test-taking skills. Aim to get a solid eight hours of sleep the night before the test so that you can wake up refreshed and at the top of your test-taking game.

#16: Review Major Concepts

It can be tempting to try to go through all your notes the night before a test to review as much information as possible, but this will likely only leave you stressed to and overwhelmed by the information you're trying to remember. If you've been regularly reviewing information throughout the class, you shouldn't need much more than a quick review of major ideas, and perhaps a few smaller details you have difficulty remembering. Even if you've gotten behind on studying and are trying to review a lot of information, resist the information to cram and focus on only a few major topics. By keeping your final night review manageable, you have a better chance of committing that information to memory, and you'll avoid lack of sleep from late night cramming.

#17: Study Right Before You Go to Sleep

Studies have shown that if you review material right before you go to sleep, you have better memory recall the next day. (This is also true if you study the information right when you wake up.) This doesn't mean you should cram all night long (remember tip #15), but if there are a few key pieces of information you especially want to review or are having trouble committing to memory, review them right before you go to bed. Sweet dreams!

Summary: The Best Way to Study for a Test

If you're not sure how to study for a test effectively, you might end up wasting hours of time only to find that you've barely learned anything at all. Overall, the best way to study for a test, whether you want to know how to study for a math test or how to study for a history test, is to study regularly and practice active learning. Cramming information and trying to remember things just by looking over notes will rarely get you the score you want. Even though the tips we suggest do take time and effort on your part, they'll be worth it when you get the score you're working towards.

What's Next?

Want tips specifically on how to study for AP exams? We've outlined the f ive steps you need to follow to ace your AP classes.

Taking the SAT and need study tips? Our guide has every study tip you should follow to reach your SAT goal score.

Or are you taking the ACT instead? We've got you covered! Read our guide to learn four different ways to study for the ACT so you can choose the study plan that's best for you.

Christine graduated from Michigan State University with degrees in Environmental Biology and Geography and received her Master's from Duke University. In high school she scored in the 99th percentile on the SAT and was named a National Merit Finalist. She has taught English and biology in several countries.

Ask a Question Below

Have any questions about this article or other topics? Ask below and we'll reply!

Improve With Our Famous Guides

- For All Students

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 160+ SAT Points

How to Get a Perfect 1600, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 800 on Each SAT Section:

Score 800 on SAT Math

Score 800 on SAT Reading

Score 800 on SAT Writing

Series: How to Get to 600 on Each SAT Section:

Score 600 on SAT Math

Score 600 on SAT Reading

Score 600 on SAT Writing

Free Complete Official SAT Practice Tests

What SAT Target Score Should You Be Aiming For?

15 Strategies to Improve Your SAT Essay

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 4+ ACT Points

How to Get a Perfect 36 ACT, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 36 on Each ACT Section:

36 on ACT English

36 on ACT Math

36 on ACT Reading

36 on ACT Science

Series: How to Get to 24 on Each ACT Section:

24 on ACT English

24 on ACT Math

24 on ACT Reading

24 on ACT Science

What ACT target score should you be aiming for?

ACT Vocabulary You Must Know

ACT Writing: 15 Tips to Raise Your Essay Score

How to Get Into Harvard and the Ivy League

How to Get a Perfect 4.0 GPA

How to Write an Amazing College Essay

What Exactly Are Colleges Looking For?

Is the ACT easier than the SAT? A Comprehensive Guide

Should you retake your SAT or ACT?

When should you take the SAT or ACT?

Stay Informed

Get the latest articles and test prep tips!

Looking for Graduate School Test Prep?

Check out our top-rated graduate blogs here:

GRE Online Prep Blog

GMAT Online Prep Blog

TOEFL Online Prep Blog

Holly R. "I am absolutely overjoyed and cannot thank you enough for helping me!”

The Learning Strategies Center

- Meet the Staff

- –Supplemental Course Schedule

- AY Course Offerings

- Anytime Online Modules

- Winter Session Workshop Courses

- –About Tutoring

- –Office Hours and Tutoring Schedule

- –LSC Tutoring Opportunities

- –How to Use Office Hours

- –Campus Resources and Support

- –Student Guide for Studying Together

- –Find Study Partners

- –Productivity Power Hour

- –Effective Study Strategies

- –Concept Mapping

- –Guidelines for Creating a Study Schedule

- –Five-Day Study Plan

- –What To Do With Practice Exams

- –Consider Exam Logistics

- –Online Exam Checklist

- –Open-Book Exams

- –How to Tackle Exam Questions

- –What To Do When You Get Your Graded Test (or Essay) Back

- –The Cornell Note Taking System

- –Learning from Digital Materials

- –3 P’s for Effective Reading

- –Textbook Reading Systems

- –Online Learning Checklist

- –Things to Keep in Mind as you Participate in Online Classes

- –Learning from Online Lectures and Discussions

- –Online Group Work

- –Learning Online Resource Videos

- –Start Strong!

- –Effectively Engage with Classes

- –Plans if you Need to Miss Class

- –Managing Time

- –Managing Stress

- –The Perils of Multitasking

- –Break the Cycle of Procrastination!

- –Finish Strong

- –Neurodiversity at Cornell

- –LSC Scholarship

- –Pre-Collegiate Summer Scholars Program

- –Study Skills Workshops

- –Private Consultations

- –Resources for Advisors and Faculty

- –Presentation Support (aka Practice Your Talk on a Dog)

- –About LSC

- –Meet The Team

- –Contact Us

Effective Study Strategies

So, what are effective study strategies for long-term learning, retrieval practice 1.

Retrieval practice is when you actively recall information (concepts, ideas, etc) from memory and “put it on paper” in different formats (writing, flow charts, diagrams, graphs). At the LSC we often call retrieval practice “Blank Page Testing,” because you just start with a blank piece of paper and write things down. It’s especially helpful because it shows you what you do (and do not) understand, so you can identify what topics you need to review/practice more. Retrieval practice can be challenging and requires a lot of mental effort — but this struggle to remember, recall, and make connections is how we learn.

To learn more about Blank Page Testing , see Mike Chen’s video:

Interleaving 2

Interleaving is when you work on or practice several related skills or concepts together. You practice one skill or concept for a short period of time, then switch to another one, and perhaps another, then back to the first. It not only helps you learn better, it keeps you from falling behind in your other classes! So please go ahead and do some work for the classes you don’t have an exam in this week! It will not only help you learn your exam material better, it will help you stay caught up.

Spaced (or distributed) practice 3

In spaced practice, you spread out practice or study of material in spaced intervals, which leads to better learning and retention. Spaced practice is the opposite of cramming!

Get sleep and make sure you eat and stay hydrated!

Your brain works better when you are rested, hydrated, and nourished. Though it might seem effective to push through without taking a break and stay up studying all night (see the page on strategies that don’t work), it won’t help you in the long run. Instead, develop a study plan, eat a good meal, and have a bottle of water nearby when you take your exam. You will learn and understand the material better if you have a plan – and you will probably need to this information for the next prelim anyway!

Tip: Piper knows that sleeping with your books under your pillow can help with learning! How does this magic work, you might wonder? Though the information in your book won’t travel via osmosis to your brain through the pillow, you will get sleep which improves your long-term learning! Sleep and a good study plan are a great study strategy combo!

Up Next: Guidelines for creating a study schedule

1 Agarwal, P. K. (2020). Retrieval Practice: A Powerful Strategy for Learning – Retrieval Practice. Unleash the Science of Learning. Retrieved from https://www.retrievalpractice.org/retrievalpractice .

2 Pan, S.C. (2015). The Interleaving Effect: Mixing It Up Boosts Learning. Retrieved from https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/the-interleaving-effect-mixing-it-up-boosts-learning/

3 Weinstein, Y. & Smith, M. (2016). Learn How to Study Using… Spaced Practice. Retrieved from https://www.learningscientists.org/blog/2016/7/21-1

- Search This Site All UCSD Sites Faculty/Staff Search Term

- Contact & Directions

- Climate Statement

- Cognitive Behavioral Neuroscience

- Cognitive Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Adjunct Faculty

- Non-Senate Instructors

- Researchers

- Psychology Grads

- Affiliated Grads

- New and Prospective Students

- Honors Program

- Experiential Learning

- Programs & Events

- Psi Chi / Psychology Club

- Prospective PhD Students

- Current PhD Students

- Area Brown Bags

- Colloquium Series

- Anderson Distinguished Lecture Series

- Speaker Videos

- Undergraduate Program

Academic and Writing Resources

- Effective Studying

How to Effectively Study

Research-supported techniques.