A simplified approach to critically appraising research evidence

Affiliation.

- 1 School of Health and Life Sciences, Teesside University, Middlesbrough, England.

- PMID: 33660465

- DOI: 10.7748/nr.2021.e1760

Background Evidence-based practice is embedded in all aspects of nursing and care. Understanding research evidence and being able to identify the strengths, weaknesses and limitations of published primary research is an essential skill of the evidence-based practitioner. However, it can be daunting and seem overly complex.

Aim: To provide a single framework that researchers can use when reading, understanding and critically assessing published research.

Discussion: To make sense of published research papers, it is helpful to understand some key concepts and how they relate to either quantitative or qualitative designs. Internal and external validity, reliability and trustworthiness are discussed. An illustration of how to apply these concepts in a practical way using a standardised framework to systematically assess a paper is provided.

Conclusion: The ability to understand and evaluate research builds strong evidence-based practitioners, who are essential to nursing practice.

Implications for practice: This framework should help readers to identify the strengths, potential weaknesses and limitations of a paper to judge its quality and potential usefulness.

Keywords: literature review; qualitative research; quantitative research; research; systematic review.

©2021 RCN Publishing Company Ltd. All rights reserved. Not to be copied, transmitted or recorded in any way, in whole or part, without prior permission of the publishers.

- Evidence-Based Medicine / standards*

- Nursing Research*

- YJBM Updates

- Editorial Board

- Colloquium Series

- Podcast Series

- Open Access

- Call for Papers

- PubMed Publications

- News & Views

- YJBM Podcasts (by topic)

- About YJBM PodSquad

- Why Publish in YJBM?

- Types of Articles Published

- Manuscript Submission Guidelines

- YJBM Ethical Guidelines

Points to Consider When Reviewing Articles

- Writing and Submitting a Review

- Join Our Peer Reviewer Database

INFORMATION FOR

- Residents & Fellows

- Researchers

General questions that Reviewers should keep in mind when reviewing articles are the following:

- Is the article of interest to the readers of YJBM ?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the manuscript?

- How can the Editors work with the Authors to improve the submitted manuscripts, if the topic and scope of the manuscript is of interest to YJBM readers?

The following contains detailed descriptions as to what should be included in each particular type of article as well as points that Reviewers should keep in mind when specifically reviewing each type of article.

YJBM will ask Reviewers to Peer Review the following types of submissions:

Download PDF

Frequently asked questions.

These manuscripts should present well-rounded studies reporting innovative advances that further knowledge about a topic of importance to the fields of biology or medicine. The conclusions of the Original Research Article should clearly be supported by the results. These can be submitted as either a full-length article (no more than 6,000 words, 8 figures, and 4 tables) or a brief communication (no more than 2,500 words, 3 figures, and 2 tables). Original Research Articles contain five sections: abstract, introduction, materials and methods, results and discussion.

Reviewers should consider the following questions:

- What is the overall aim of the research being presented? Is this clearly stated?

- Have the Authors clearly stated what they have identified in their research?

- Are the aims of the manuscript and the results of the data clearly and concisely stated in the abstract?

- Does the introduction provide sufficient background information to enable readers to better understand the problem being identified by the Authors?

- Have the Authors provided sufficient evidence for the claims they are making? If not, what further experiments or data needs to be included?

- Are similar claims published elsewhere? Have the Authors acknowledged these other publications? Have the Authors made it clear how the data presented in the Author’s manuscript is different or builds upon previously published data?

- Is the data presented of high quality and has it been analyzed correctly? If the analysis is incorrect, what should the Authors do to correct this?

- Do all the figures and tables help the reader better understand the manuscript? If not, which figures or tables should be removed and should anything be presented in their place?

- Is the methodology used presented in a clear and concise manner so that someone else can repeat the same experiments? If not, what further information needs to be provided?

- Do the conclusions match the data being presented?

- Have the Authors discussed the implications of their research in the discussion? Have they presented a balanced survey of the literature and information so their data is put into context?

- Is the manuscript accessible to readers who are not familiar with the topic? If not, what further information should the Authors include to improve the accessibility of their manuscript?

- Are all abbreviations used explained? Does the author use standard scientific abbreviations?

Case reports describe an unusual disease presentation, a new treatment, an unexpected drug interaction, a new diagnostic method, or a difficult diagnosis. Case reports should include relevant positive and negative findings from history, examination and investigation, and can include clinical photographs. Additionally, the Author must make it clear what the case adds to the field of medicine and include an up-to-date review of all previous cases. These articles should be no more than 5,000 words, with no more than 6 figures and 3 tables. Case Reports contain five sections: abstract; introduction; case presentation that includes clinical presentation, observations, test results, and accompanying figures; discussion; and conclusions.

- Does the abstract clearly and concisely state the aim of the case report, the findings of the report, and its implications?

- Does the introduction provide enough details for readers who are not familiar with a particular disease/treatment/drug/diagnostic method to make the report accessible to them?

- Does the manuscript clearly state what the case presentation is and what was observed so that someone can use this description to identify similar symptoms or presentations in another patient?

- Are the figures and tables presented clearly explained and annotated? Do they provide useful information to the reader or can specific figures/tables be omitted and/or replaced by another figure/table?

- Are the data presented accurately analyzed and reported in the text? If not, how can the Author improve on this?

- Do the conclusions match the data presented?

- Does the discussion include information of similar case reports and how this current report will help with treatment of a disease/presentation/use of a particular drug?

Reviews provide a reasoned survey and examination of a particular subject of research in biology or medicine. These can be submitted as a mini-review (less than 2,500 words, 3 figures, and 1 table) or a long review (no more than 6,000 words, 6 figures, and 3 tables). They should include critical assessment of the works cited, explanations of conflicts in the literature, and analysis of the field. The conclusion must discuss in detail the limitations of current knowledge, future directions to be pursued in research, and the overall importance of the topic in medicine or biology. Reviews contain four sections: abstract, introduction, topics (with headings and subheadings), and conclusions and outlook.

- Is the review accessible to readers of YJBM who are not familiar with the topic presented?

- Does the abstract accurately summarize the contents of the review?

- Does the introduction clearly state what the focus of the review will be?

- Are the facts reported in the review accurate?

- Does the Author use the most recent literature available to put together this review?

- Is the review split up under relevant subheadings to make it easier for the readers to access the article?

- Does the Author provide balanced viewpoints on a specific topic if there is debate over the topic in the literature?

- Are the figures or tables included relevant to the review and enable the readers to better understand the manuscript? Are there further figures/tables that could be included?

- Do the conclusions and outlooks outline where further research can be done on the topic?

Perspectives provide a personal view on medical or biomedical topics in a clear narrative voice. Articles can relate personal experiences, historical perspective, or profile people or topics important to medicine and biology. Long perspectives should be no more than 6,000 words and contain no more than 2 tables. Brief opinion pieces should be no more than 2,500 words and contain no more than 2 tables. Perspectives contain four sections: abstract, introduction, topics (with headings and subheadings), and conclusions and outlook.

- Does the abstract accurately and concisely summarize the main points provided in the manuscript?

- Does the introduction provide enough information so that the reader can understand the article if he or she were not familiar with the topic?

- Are there specific areas in which the Author can provide more detail to help the reader better understand the manuscript? Or are there places where the author has provided too much detail that detracts from the main point?

- If necessary, does the Author divide the article into specific topics to help the reader better access the article? If not, how should the Author break up the article under specific topics?

- Do the conclusions follow from the information provided by the Author?

- Does the Author reflect and provide lessons learned from a specific personal experience/historical event/work of a specific person?

Analyses provide an in-depth prospective and informed analysis of a policy, major advance, or historical description of a topic related to biology or medicine. These articles should be no more than 6,000 words with no more than 3 figures and 1 table. Analyses contain four sections: abstract, introduction, topics (with headings and subheadings), and conclusions and outlook.

- Does the abstract accurately summarize the contents of the manuscript?

- Does the introduction provide enough information if the readers are not familiar with the topic being addressed?

- Are there specific areas in which the Author can provide more detail to help the reader better understand the manuscript? Or are there places where the Author has provided too much detail that detracts from the main point?

Profiles describe a notable person in the fields of science or medicine. These articles should contextualize the individual’s contributions to the field at large as well as provide some personal and historical background on the person being described. More specifically, this should be done by describing what was known at the time of the individual’s discovery/contribution and how that finding contributes to the field as it stands today. These pieces should be no more than 5,000 words, with up to 6 figures, and 3 tables. The article should include the following: abstract, introduction, topics (with headings and subheadings), and conclusions.

- Does the Author provide information about the person of interest’s background, i.e., where they are from, where they were educated, etc.?

- Does the Author indicate how the person focused on became interested or involved in the subject that he or she became famous for?

- Does the Author provide information on other people who may have helped the person in his or her achievements?

- Does the Author provide information on the history of the topic before the person became involved?

- Does the Author provide information on how the person’s findings affected the field being discussed?

- Does the introduction provide enough information to the readers, should they not be familiar with the topic being addressed?

Interviews may be presented as either a transcript of an interview with questions and answers or as a personal reflection. If the latter, the Author must indicate that the article is based on an interview given. These pieces should be no more than 5,000 words and contain no more than 3 figures and 2 tables. The articles should include: abstract, introduction, questions and answers clearly indicated by subheadings or topics (with heading and subheadings), and conclusions.

- Does the Author provide relevant information to describe who the person is whom they have chosen to interview?

- Does the Author explain why he or she has chosen the person being interviewed?

- Does the Author explain why he or she has decided to focus on a specific topic in the interview?

- Are the questions relevant? Are there more questions that the Author should have asked? Are there questions that the Author has asked that are not necessary?

- If necessary, does the Author divide the article into specific topics to help the reader better access the article? If not, how should the author break up the article under specific topics?

- Does the Author accurately summarize the contents of the interview as well as specific lesson learned, if relevant, in the conclusions?

How to Write Limitations of the Study (with examples)

This blog emphasizes the importance of recognizing and effectively writing about limitations in research. It discusses the types of limitations, their significance, and provides guidelines for writing about them, highlighting their role in advancing scholarly research.

Updated on August 24, 2023

No matter how well thought out, every research endeavor encounters challenges. There is simply no way to predict all possible variances throughout the process.

These uncharted boundaries and abrupt constraints are known as limitations in research . Identifying and acknowledging limitations is crucial for conducting rigorous studies. Limitations provide context and shed light on gaps in the prevailing inquiry and literature.

This article explores the importance of recognizing limitations and discusses how to write them effectively. By interpreting limitations in research and considering prevalent examples, we aim to reframe the perception from shameful mistakes to respectable revelations.

What are limitations in research?

In the clearest terms, research limitations are the practical or theoretical shortcomings of a study that are often outside of the researcher’s control . While these weaknesses limit the generalizability of a study’s conclusions, they also present a foundation for future research.

Sometimes limitations arise from tangible circumstances like time and funding constraints, or equipment and participant availability. Other times the rationale is more obscure and buried within the research design. Common types of limitations and their ramifications include:

- Theoretical: limits the scope, depth, or applicability of a study.

- Methodological: limits the quality, quantity, or diversity of the data.

- Empirical: limits the representativeness, validity, or reliability of the data.

- Analytical: limits the accuracy, completeness, or significance of the findings.

- Ethical: limits the access, consent, or confidentiality of the data.

Regardless of how, when, or why they arise, limitations are a natural part of the research process and should never be ignored . Like all other aspects, they are vital in their own purpose.

Why is identifying limitations important?

Whether to seek acceptance or avoid struggle, humans often instinctively hide flaws and mistakes. Merging this thought process into research by attempting to hide limitations, however, is a bad idea. It has the potential to negate the validity of outcomes and damage the reputation of scholars.

By identifying and addressing limitations throughout a project, researchers strengthen their arguments and curtail the chance of peer censure based on overlooked mistakes. Pointing out these flaws shows an understanding of variable limits and a scrupulous research process.

Showing awareness of and taking responsibility for a project’s boundaries and challenges validates the integrity and transparency of a researcher. It further demonstrates the researchers understand the applicable literature and have thoroughly evaluated their chosen research methods.

Presenting limitations also benefits the readers by providing context for research findings. It guides them to interpret the project’s conclusions only within the scope of very specific conditions. By allowing for an appropriate generalization of the findings that is accurately confined by research boundaries and is not too broad, limitations boost a study’s credibility .

Limitations are true assets to the research process. They highlight opportunities for future research. When researchers identify the limitations of their particular approach to a study question, they enable precise transferability and improve chances for reproducibility.

Simply stating a project’s limitations is not adequate for spurring further research, though. To spark the interest of other researchers, these acknowledgements must come with thorough explanations regarding how the limitations affected the current study and how they can potentially be overcome with amended methods.

How to write limitations

Typically, the information about a study’s limitations is situated either at the beginning of the discussion section to provide context for readers or at the conclusion of the discussion section to acknowledge the need for further research. However, it varies depending upon the target journal or publication guidelines.

Don’t hide your limitations

It is also important to not bury a limitation in the body of the paper unless it has a unique connection to a topic in that section. If so, it needs to be reiterated with the other limitations or at the conclusion of the discussion section. Wherever it is included in the manuscript, ensure that the limitations section is prominently positioned and clearly introduced.

While maintaining transparency by disclosing limitations means taking a comprehensive approach, it is not necessary to discuss everything that could have potentially gone wrong during the research study. If there is no commitment to investigation in the introduction, it is unnecessary to consider the issue a limitation to the research. Wholly consider the term ‘limitations’ and ask, “Did it significantly change or limit the possible outcomes?” Then, qualify the occurrence as either a limitation to include in the current manuscript or as an idea to note for other projects.

Writing limitations

Once the limitations are concretely identified and it is decided where they will be included in the paper, researchers are ready for the writing task. Including only what is pertinent, keeping explanations detailed but concise, and employing the following guidelines is key for crafting valuable limitations:

1) Identify and describe the limitations : Clearly introduce the limitation by classifying its form and specifying its origin. For example:

- An unintentional bias encountered during data collection

- An intentional use of unplanned post-hoc data analysis

2) Explain the implications : Describe how the limitation potentially influences the study’s findings and how the validity and generalizability are subsequently impacted. Provide examples and evidence to support claims of the limitations’ effects without making excuses or exaggerating their impact. Overall, be transparent and objective in presenting the limitations, without undermining the significance of the research.

3) Provide alternative approaches for future studies : Offer specific suggestions for potential improvements or avenues for further investigation. Demonstrate a proactive approach by encouraging future research that addresses the identified gaps and, therefore, expands the knowledge base.

Whether presenting limitations as an individual section within the manuscript or as a subtopic in the discussion area, authors should use clear headings and straightforward language to facilitate readability. There is no need to complicate limitations with jargon, computations, or complex datasets.

Examples of common limitations

Limitations are generally grouped into two categories , methodology and research process .

Methodology limitations

Methodology may include limitations due to:

- Sample size

- Lack of available or reliable data

- Lack of prior research studies on the topic

- Measure used to collect the data

- Self-reported data

The researcher is addressing how the large sample size requires a reassessment of the measures used to collect and analyze the data.

Research process limitations

Limitations during the research process may arise from:

- Access to information

- Longitudinal effects

- Cultural and other biases

- Language fluency

- Time constraints

The author is pointing out that the model’s estimates are based on potentially biased observational studies.

Final thoughts

Successfully proving theories and touting great achievements are only two very narrow goals of scholarly research. The true passion and greatest efforts of researchers comes more in the form of confronting assumptions and exploring the obscure.

In many ways, recognizing and sharing the limitations of a research study both allows for and encourages this type of discovery that continuously pushes research forward. By using limitations to provide a transparent account of the project's boundaries and to contextualize the findings, researchers pave the way for even more robust and impactful research in the future.

Charla Viera, MS

See our "Privacy Policy"

Ensure your structure and ideas are consistent and clearly communicated

Pair your Premium Editing with our add-on service Presubmission Review for an overall assessment of your manuscript.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- ADVERTISEMENT FEATURE Advertiser retains sole responsibility for the content of this article

An in-depth look at research strengths of a leading supporter of science

Produced by

In high-quality output, medical and health research is growing strongly despite not being a traditional strength for CAS. Credit: Andrew Brookes·Getty

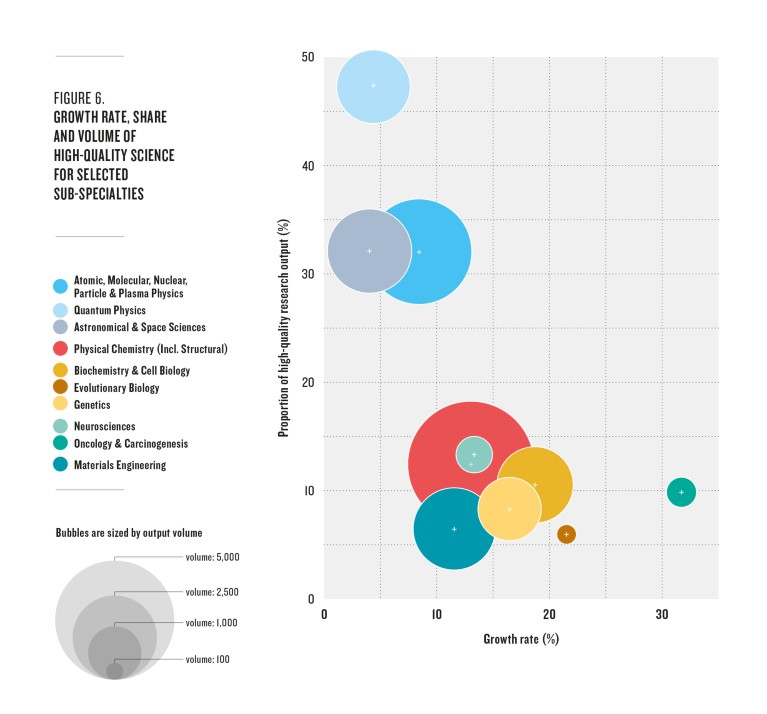

A closer look at high-quality research output by sub specialities provides deeper insights into CAS’s strengths. Here, basic science subjects, particularly in chemical and physical sciences, are still dominant, while applied subjects, in engineering and medical and health sciences, again exhibit the greatest growth.

Top sub specialities by overall output

Across all the sub specialities, CAS publishes most high-quality papers in physical chemistry (5,557 since 2008). Indeed, this is also the sub speciality with the largest volume of total output. Physical chemistry is the basis of many material engineering technologies, so has many applications in both basic research and society more broadly. The next strongest fields are in the physical sciences: atomic, molecular, nuclear, particle, and plasma physics (3,871 papers), and astronomical and space sciences (2,454 papers).

These basic science fields have also received increased numbers of external grants over the past decade. The physical subjects in particular require big science facilities, such as powerful particle accelerators and large radio telescopes. As part of the Pioneer Initiative, CAS has built Mega-Science Research Centers, which provide facilities and platforms for innovative basic research of strategic importance. The Daya Bay Neutrino Experiment, led by the CAS Institute of High Energy Physics, is an example of CAS’s research capacity in this field. It involved several international partners and succeeded in measuring the third type of neutrino oscillation in 2012 1 .

Materials engineering and biochemistry and cell biology also have more than 2,000 high-quality publications apiece. The latter accounted for more than half of all high-quality papers in the biological sciences and had a CAGR of nearly 19%, the second fastest in the field. Several biochemistry papers have come from the two recently opened centres of excellence, led by the Shanghai Institute of Biological Sciences (SIBS) and the Institute of Biophysics (IBP) in Beijing. IBP also led a ‘Priority’ programme studying biomacromolecules, which ran from 2014 to 2018. SIBS is leading another, ongoing ‘Priority’ programme that explores the molecular regulation of cell fate.

Concentration of high quality research

Another way to identify CAS’s strongest research fields is to examine the percentage of high-quality research, namely, the proportion of the output of each sub speciality published in Nature Index journals. Here, several physical and chemical science subjects stand out, suggesting CAS’s robust research capacity ( Figure 6 ).

Quantum physics, in particular, has the highest concentration of high-quality research. Roughly one in every two quantum physics papers is published in a Nature Index journal, a proportion that has remained fairly stable over the past 10 years. Two other physical science subjects, astronomical and space sciences, as well as atomic and molecular physics, have around 33% of papers in the high-quality group. In addition, inorganic chemistry and organic chemistry, two traditional strengths of CAS, have around 17% papers in Nature Index journals.

Quantum physics: A quantum revolution linking basic science and application

Quantum physics examines the fundamental energy and sub-atomic particles of the universe and it represents a growing opportunity for CAS. Thanks to generous governmental support, a number of large, strategically important frontier research facilities have been constructed in recent decades. CAS has turned this advantage into large numbers of high-quality publications and, crucially, into real-world applications.

The Quantum Experiments at Space Scale (QUESS) 2 , which CAS initiated in 2011 as a ‘Priority’ programme is one such project. QUESS is led by Jianwei Pan from the University of Science and Technology of China (USTC), which was established by CAS in 1958, and it made headlines in 2016 when it launched the world’s first quantum satellite.

Named Micius (or Mozi in Chinese), after the ancient Chinese philosopher, the satellite marked a giant step for quantum communication. Pan’s team sent entangled photons from Micius to two ground stations more than 1,200 kilometres apart, demonstrating their potential as quantum keys to achieve ultra-secure communications 3 . This built on an earlier result where Pan’s team demonstrated quantum teleportation and entanglement distribution over about 100 km in ground-based experiments. The CAS team has gone on to construct a 2,000 km ground link between Beijing and Shanghai to send quantum-encrypted keys. The link will enable eavesdrop-proof data transmission, making it the world’s longest terrestrial quantum key distribution network.

Another project, also initiated by Pan, is a 2012 ‘Priority’ programme designed to study coherent control of quantum systems. In that programme, Pan seeks to apply basic theories in quantum physics to quantum computation. By manipulating multi-photon entanglement, Pan’s team developed the first quantum computing prototype, which outperformed early-generation classical computers in modelling photon behaviours 4 . “Our architecture is feasible to be scaled up to a larger number of photons and with a higher rate, to race against increasingly advanced classical computers,” the authors wrote in a Nature Photonics paper 5 .

Collaboration among CAS research groups, and between CAS and other universities, helps propel CAS’s quantum research. One such example is the Center for Excellence in Quantum Information and Quantum Physics, established in 2014 as one of the first five CAS centres for excellence. Led by USTC, the centre includes interdisciplinary resources from the Shanghai Institute of Technological Physics and the Institute of Semiconductors at CAS. It also led the development of the quantum computing prototype alongside the CAS Institute of Physics, Zhejiang University and industry. Meanwhile, Pan’s team is working with industry and local governments to commercialize research in quantum communication and quantum information.

To maintain its edge in quantum physics, CAS also embraced student education. As Pan said in an interview with MIT Technology Review 6 , “we are working hard to develop the workforce of the future in quantum technology.” And the capacity to integrate research and education also underlies CAS’s success in research output.

Health is a growing concern

When looking at growth, applied science subjects have the greatest potential. The highest-growth subject across all sub specialities, with a nearly 32% CAGR, is oncology and carcinogenesis. It is followed by electrical and electronic engineering, with a CAGR of almost 28%. Immunology and clinical sciences also have CAGRs above 20%. Though the total output over the past decade is not large, their fast rise suggests an increasing focus on health-related research, which is reflected in the broader Chinese scientific community.

Cancer research: A healthy growth

Medical and health sciences are not a traditional strength for CAS. Out of CAS’s 100-plus institutes, fewer than 10 have an explicit medical science focus, a majority of which have been established since the turn of the century. However, this type of research is rapidly growing at CAS, and no subject is growing faster than oncology and carcinogenesis: the study of cancer, including its formation and treatment.

Breakthroughs in genomics, immunology and stem cell research have spurred the development of cancer therapies. At CAS, the central government’s ‘Healthy China’ initiative, which emphasizes disease prevention, chronic disease management and high-quality treatment, drove efforts to translate basic research in fields like biological sciences, chemistry, and physics into medical and health innovations.

The focus on clinical application is explicit in a CAS ‘Priority’ programme initiated in 2016, which aimed at developing personalised drugs based on improved understanding of molecular mechanisms of diseases and genetic differences between patients. With developing cancer drugs as a major component, objectives were clearly set to identify biomarkers for drug targets, and obtain new drug certificates.

Led by the Shanghai Institute of Materia Medica (SIMM), in collaboration with other institutes at SIBS, and IBP in Beijing, this programme links basic research to clinical medicine. “In this billion dollar programme, we are trying to apply the concept of molecular typing for diseases to drug discovery,” said Jia Li, the director of SIMM, at the 2019 Pujiang Innovation Forum 7 .

One representative result is a 2018 Cell paper, led by Meiyu Geng of SIMM, reporting potential of a precision treatment strategy for a specific kind of solid tumours by targeting epigenetic crosstalk 8 . The result may inform drug development for this tumour.

Apart from biological or health sciences-related institutes, other CAS institutes also contribute to oncology research. The National Center for Nanoscience and Technology (NCNST), for instance, is developing nanorobots to deliver cancer drugs. In this intelligent system, programmed DNA is folded when entering the bloodstream and unfolds at the tumour site to dispense a cancer-fighting protein 9 . “This breakthrough integrates nanotechnology with molecular biology,” said Yuliang Zhao, director of NCNST who led this Nature Biotechnology study. “It will open a new realm for nanomedicine.”

Much of CAS’s oncology work is cross-disciplinary between physical science and biomedical researchers. NCNST researchers also use nanoparticles to improve cancer imaging, and to combine therapeutic and diagnostic action. Moreover, researchers at the CAS Institute of Physics work with hospital partners to develop improved probing techniques for cancer detection.

Further development of cancer research requires closer integration between CAS’s many institutes and more cross-disciplinary collaboration between physical science and biomedical researchers, and even clinicians. Just as some nanoscience experts outline, the research should be guided by clinical need, as after all, the ultimate goal is to benefit cancer patients.

To promote such clinical application, CAS signed an agreement in early 2019 with the Zhejiang provincial government to establish the Institute of Cancer and Basic Medicine based on Zhejiang Cancer Hospital (which will itself be named the Cancer Hospital of the University of Chinese Academy of Sciences). As CAS’s first dedicated cancer research institution, it will link basic, clinical and translational research, seeking to commercialize its results. Future growth in cancer research output is expected to follow, along with greater clinical benefits.

https://newscenter.lbl.gov/2012/03/07/daya-bay-first-results/

http://www.cas.cn/xw/zyxw/tpxw/201401/t20140116_4024081.shtml

Yin et al. Satellite-based entanglement distribution over 1200 kilometers. Science, 356, 1140-1144 (2017)

Google Scholar

https://futurism.com/china-develops-a-quantum-computer-that-could-eclipse-all-others

Wang et. al. High-efficiency multiphoton boson sampling. Nature Photonics , 11, 361-365 (2017)

https://www.technologyreview.com/s/612596/the-man-turning-china-into-a-quantum-superpower/

http://www.biodiscover.com/news/hot/734329.html

Huang et. al. Targeting Epigenetic Crosstalk as a Therapeutic Strategy for EZH2-Aberrant Solid Tumors. Cell , 175(1), 186-199 (2018)

Li et. al. A DNA nanorobot functions as a cancer therapeutic in response to a molecular trigger in vivo . Nature Biotechnology , 36, 258-264 (2018)

Download references

Related Articles

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

- Log in / Register

- Getting started

- Criteria for a problem formulation

- Find who and what you are looking for

- Too broad, too narrow, or o.k.?

- Test your knowledge

- Lesson 5: Meeting your supervisor

- Getting started: summary

- Literature search

- Searching for articles

- Searching for Data

- Databases provided by your library

- Other useful search tools

- Free text, truncating and exact phrase

- Combining search terms – Boolean operators

- Keep track of your search strategies

- Problems finding your search terms?

- Different sources, different evaluations

- Extract by relevance

- Lesson 4: Obtaining literature

- Literature search: summary

- Research methods

- Combining qualitative and quantitative methods

- Collecting data

- Analysing data

Strengths and limitations

- Explanatory, analytical and experimental studies

- The Nature of Secondary Data

- How to Conduct a Systematic Review

- Directional Policy Research

- Strategic Policy Research

- Operational Policy Research

- Conducting Research Evaluation

- Research Methods: Summary

- Project management

- Project budgeting

- Data management plan

- Quality Control

- Project control

- Project management: Summary

- Writing process

- Title page, abstract, foreword, abbreviations, table of contents

- Introduction, methods, results

- Discussion, conclusions, recomendations, references, appendices, layout

- Use citations correctly

- Use references correctly

- Bibliographic software

- Writing process – summary

- Research methods /

- Lesson 1: Qualitative and quan… /

Quantitative method Quantitive data are pieces of information that can be counted and which are usually gathered by surveys from large numbers of respondents randomly selected for inclusion. Secondary data such as census data, government statistics, health system metrics, etc. are often included in quantitative research. Quantitative data is analysed using statistical methods. Quantitative approaches are best used to answer what, when and who questions and are not well suited to how and why questions.

Qualitative method Qualitative data are usually gathered by observation, interviews or focus groups, but may also be gathered from written documents and through case studies. In qualitative research there is less emphasis on counting numbers of people who think or behave in certain ways and more emphasis on explaining why people think and behave in certain ways. Participants in qualitative studies often involve smaller numbers of tools include and utilizes open-ended questionnaires interview guides. This type of research is best used to answer how and why questions and is not well suited to generalisable what, when and who questions.

Learn more about using quantitative and qualitative approaches in various study types in the next lesson.

Your friend's e-mail

Message (Note: The link to the page is attached automtisk in the message to your friend)

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Med Libr Assoc

- v.90(1); 2002 Jan

Editorial Peer Review: Its Strengths and Weaknesses.

Julia f. sollenberger.

1 Edward G. Miner Library University of Rochester Medical Center Rochester, New York

Weller, Ann C. Editorial Peer Review: Its Strengths and Weaknesses. Medford, NJ: Information Today, 2001. (ASIS&T Monograph Series). 342 p. Hardcover. $44.50. ISBN 1-57387-100-1.

Health sciences librarians study and teach the principles of evidence-based medicine (EBM), search evidence-based health care (EBHC) resources, and strive to practice evidence-based librarianship (EBL) [ 1 ]. In this work, Weller extends “EB” awareness to evidence-based scientific publishing. By providing a systematic review of empirical studies on the editorial peer review process from 1945 to 1997, the author assembles the available evidence on the value and validity of that process and its effect on the quality of the published literature. The author presents the strengths and weaknesses of peer review, analyzes the benefits and shortcomings, makes recommendations for further research, and provides information for improving future studies. With perhaps 6,000 to 7,000 scientific articles written every day [ 2 ] and with the review process for just one journal estimated to cost about $1 million a year [ 3 ], questioning the worth of this process is appropriate.

Though most understand what editorial peer review is, or have experienced it firsthand when submitting manuscripts for review, few have considered its diverse aspects in detail. This book provides insight and brings to light nagging questions such as the following: “What is the evidence that the ‘best’ science or scholarly material is published and the ‘worst’ is rejected?” (p. 51); “What is the value of the review process to authors?” (p. 120); “What is known about the overall quality of reviewers' reports?” (p. 158); “To what degree do reviewers agree with each other when evaluating the same manuscript?” (p. 182); “Is the submission versus acceptance rate for manuscripts different depending on the gender or ethnicity of the author?” (p. 227); and “What kind of statistical errors have been identified through studies of published articles?” (p. 255). Editorial Peer Review offers analyses of research studies that may answer these and other questions. For each question, the author methodically states the criteria for study inclusion, appraises the validity of the studies that address that issue, and, finally, proposes recommendations and draws conclusions based upon the evidence.

The preface of this book succinctly states its purpose and its methodology and describes the structure of the book. It is important to understand this before plunging into the substance of the work. Following the introductory chapter, which includes a brief history of the topic and the process used to compile the relevant studies, chapters appear on rejection rates, editors and editorial boards, authors and authorship, role of reviewers and quality of their reviews (including review agreement and bias), and statistical review of manuscripts. Each of these sections is extensive and substantive. One chapter addresses peer review in an electronic environment, and the final one presents key conclusions and recommendations.

Because the literature covered in the work does not extend beyond 1998, Weller's chapter entitled “Peer Review in an Electronic Environment” is necessarily limited. The rapidity of change in this arena requires conjecture rather than analysis, as few relevant studies are either completed or in progress. The author was obliged to address the electronic aspects of scholarly publishing, because she previously had given the transition from print to electronic as one of the primary reasons for undertaking this project. “As publication moves from print to electronics and the editorial peer review process may undergo change as a result, now is an excellent time to examine the cumulated information on editorial peer review and critically evaluate the entire process” (p. 3). This reviewer looks forward to the author's future investigation and analysis of peer review in a digital world, as the process of electronic publishing matures and a new area of research emerges.

For all other topics covered in this work, the number of studies cited and the depth of analysis are astounding, so much so that the more casual reader may be overwhelmed by the sheer number of references, author names, and study descriptions. Although tables are used effectively throughout the work to present salient characteristics and findings of a large number of research studies, the reader without knowledge of research design or not already familiar with the literature of peer review could find it challenging to digest. Such a reader would do well to attack each chapter in the following manner: (1) read the introductory and background sections, (2) note the research questions and study inclusion criteria, and, (3) finally, move to the recommendations and conclusions. The detail that is included, though necessary for a systematic review of this nature, will be most useful to those who are designing research studies to address the issues of peer review or to journal editors attempting to improve the process. The core elements of the work are of interest to a wide range of readers concerned with scholarly communication, from reviewers, to publishers, writers, and librarians.

There is a simple reason for the complexity of fields of study that encompasses peer review and the volume of the literature included in this systematic review—editorial peer review is not limited to a single discipline. Although the field of medicine has apparently produced a large number of the studies, Weller points out that “Since editorial peer review is not a discipline-specific field, literature on the subject could and does exist in almost every scholarly field with a journal publication outlet” (p. 8). The need to cover disciplines that range from medicine, nursing, education, agriculture, and management science has resulted in an in-depth and extensive treatment.

The author of this work is well known for her investigations of the scientific peer review and publishing process. She is also a highly regarded and active member of the Medical Library Associations' Research Section. Using a clear and precise writing style and declaring her own fascination with the topic, she compares the process of tracking down relevant studies to the design of a mystery novel. In the preface, she reveals that “a strategy somewhat akin to Sherlock Holmes' methodology was needed to identify and locate all studies in this field. With an eagerness similar to Holmes' enthusiastic, ‘The game is afoot,’ I relentlessly tracked down all leads” (p. xiv). In the end, the author's zeal, knowledge of the field, and skills in writing and analysis lead this reviewer to speculate that, given the time, the author herself just might be able to resolve every one of the hundreds of research questions remaining in the field of editorial peer review! Surely few are more qualified to make the attempt.

- Eldredge JD. Evidence-based librarianship: an overview . Bull Med Libr Assoc . 2000 Oct; 88 ( 4 ):289–302. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Arndt KA. Information excess in medicine . Arch Derm . 1992 Sep; 128 ( 9 ):1249–56. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Relman AS. Peer review in scientific journals—what good is it? West J Med . 1990 Nov; 153 ( 5 ):520–2. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Internet , Productivity

30 Best Students Strengths And Weaknesses List & Examples

Whether you are a high school student applying to college or a college student creating a resume for a part-time job , understanding your strengths and weaknesses is key to selling yourself.

Sure, your academic achievements go a long way, but standing out among the large pool of other students with similar achievements requires showing why you are the right fit.

Having a firm grasp of your strengths and weaknesses as a student allows you to answer that question convincingly.

Even if you are not pursuing either goal, understanding what you are good or poor at helps you build on existing successes and improve your overall performance.

Below is a list of strengths and weaknesses with examples of applying them in the real world. Before we dive in, I should tell you that none of these are permanent qualities.

If you identify with more qualities in either category, it doesn’t make you perfect or damaged. Each weakness can be worked on, and every strength requires consistency to stay one.

With that said, here are 30 best strengths and weaknesses as a student with examples.

Examples of Student Strengths

When writing about your strengths as a student, here are some examples worth mentioning. Review the list to choose what best fits your application.

Ask your peers and teachers if you don’t find one that matches your perceived qualities or are unsure of your strengths.

1. Trustworthy

Consider highlighting your trustworthiness, especially if you are applying for a job . Many business owners are wary of young people due to their unpredictability.

Showing that you can be relied upon to carry out tasks and be trusted to handle critical parts of the business is beneficial.

On an application or interview , you might phrase it like this:

“One of the first life lessons I learned was the importance of being trustworthy. I understand that people won’t give me responsibilities if they don’t believe I can handle it without worrying about my reliability.”

2. Creativity Skills For Different and Unusual Perspectives

image source: Alice Dietrich

Today, universities and businesses seek students who can use their different and unusual perspectives to develop successful strategies and solutions.

Sharing how your creativity helped you achieve academic success or solve a problem may help you stand out.

It doesn’t matter if you aren’t visually creative, either. You only need to show you can think in a novel direction.

This strength is helpful, whatever the job or field you wish to major in, but it is crucial in the arts.

3. Self-Learner

As a student, you learn different things in class. Still, the professional world values those who independently find and master learning resources .

Independent learning is not only an admirable trait to include in college or job applications , but one that helps you throughout your life.

This could be via online courses, unpaid (voluntary) internship, or mastering a specific subject. Don’t hesitate to display your self-learning qualities. It could be the defining difference between you and someone who might need a lot of hands-on training.

4. Discipline

image Source: Thao Le Hoang

The ability to stay focused and motivated on a specific goal in unpredictable circumstances is known as self-discipline. To universities and employers, it also means the ability to do the right thing at the right time.

You can communicate this strength by saying something like:

“I study for two hours from 8 to 10 pm every night. There are a hundred other things I’d rather be doing, but I know if I am going to become a [university name] freshman, I have to make sacrifices.”

5. Kindness

In the classroom and the outside world, kindness is a strength. Being capable of treating others with respect and being empathetic to their circumstances is important.

You might think this shouldn’t matter to admission officers or HR, but it shows you can connect with the people around you and leave a positive impact.

It also enhances the likelihood of cultural fit. If an organization values kindness among its staff, showing you have a compatible personality will give weight to your application.

6. Critical Thinking

image Source: Lou Levit

Professors and managers need to know you can figure out the right solution when presented with a problem. Critical thinking is a valuable skill that proves that and a strength for any student who has it.

Critical thinking skills involve the systematic analysis of evidence collected via experience, observation, reasoning, and reflection. It also includes considering a variety of outcomes to make a decision.

You could tell a story of when you demonstrated critical insight to achieve academic success in your application.

7. Planning Skills

Planning involves the consideration of different activities necessary to achieve a goal. It is a skill that requires other skills like communication skills, multitasking, project management skills, and problem-solving.

Planning also involves leveraging hindsight and foresight. If you’ve successfully planned a school or class event, feel free to add it to your application.

Even if you weren’t successful, showing how you failed and what you learned from it is a real advantage, whatever your goals might be.

image source: Devin Avery

One of the most critical student strengths is focus. Being focused means the ability to stay on a task without constant supervision.

As a high school student, focus as part of your strength tells admission officers you have what it takes to succeed in college, where there are plenty of distractions.

Much of the evidence of this is in your academic records, but you can also write something like:

“I am a focused person. It’s a quality I’ve developed because it helps me complete my tasks faster, keeps me sharper, and makes it easier to get several things done.”

9. Time Management Skills

Strong time management enables you to balance competing interests in your schedule. You can manage all your classes, events, and activities without falling behind.

It also shows you can adhere to strict opening and closing schedules as a potential employee.

Breaking down large tasks into a to-do list allows you to estimate the time needed for each assignment more accurately. This way, you can plan your days better and avoid procrastination.

There are plenty of student strengths to choose from, but adding this strength to your application shows you have what it takes to succeed.

10. Coding Skills

image source: Christopher Gower

Coding highlights problem solving skills and can be another major skill in the student strengths and weaknesses list. You might exclusively associate with technology and software design. But it goes beyond that.

Aside from the fact technology is embedded in all spheres of our lives today, coding skills embed other skills. This includes analytical thinking, research, problem-solving skills, self-learning, etc.

Coding is also a sign of efficient thinking.

If you can code software to solve a specific problem—whatever the role or degree—include it in your application. It can help set you apart from other applicants.

11. Collaborative Skills

Don’t discount the value of your ability to work well with others. It is a practical and handy quality for students as projects and programs require them to work with others. Social skills go a long way to accomplishing everyday tasks.

Adding your collaborative and social skills and describing how you’ve used them in your application may benefit you.

“I worked with six classmates to develop an attendance monitoring system for our online classes. It improved the average class attendance by 25%. I’m looking forward to working on new projects with my future classmates.”

12. Open to Criticism

image source: Marcus Winkler

One of the student strengths college admission offices look for is showing you can gracefully accept criticism.

Your professors and peers will criticize you for something you will inevitably do poorly. Knowing that when the time comes, you won’t react negatively and instead channel it into improving your results is worth sharing.

Employees, especially those who believe young people are unteachable, also value these qualities.

In your student application or interview , you can share an instance where your openness to criticism helped better your performance.

13. Open Mindedness

A college is a place with diverse ideas, concepts, and facts. A student needs to be open-minded enough to engage with them to thrive. This is a favorable quality for admission officers.

Being open-minded also shows curiosity, which is a strength for a student. Open-minded students are more likely to learn ideas outside their classroom from books or the internet and apply this knowledge in class discussions.

Future employers are also more likely to see open-minded students as better fits for their adult environment.

14. Determination

School comes with its social and academic challenges. Some manifest in the struggle to make friends or study to pass classes you don’t like.

Coming across as a determined person tells admission officers that you’ve got what it takes to become a successful student.

A tested and trusted way to do that is to share a story of a time you overcame adversity to achieve your goals. The details don’t have to align with the field you’re applying to. It just needs to show the kind of person you are.

15. Growth Mindset and Positive Attitude

A growth mindset enables you to develop your talents and abilities . College admission offices and business owners appreciate this quality in students.

It is especially a great strength to include in an application if you have a less than stellar academic record. Having a growth mindset tells them you are willing to improve existing capabilities and learn new ones. It also signifies that you have good organizational skills.

Including this in your list of strengths and weaknesses will compensate for any deficiencies and reservations the application review personnel might have.

Examples of Student Weaknesses

image source: Tony Tran

College admission officers and employers want a full picture of your personality trait. This means they want to learn what makes you great as much as the things you find challenging.

Below are 15 weaknesses to choose from. Pick the most relevant ones to the field or role you’re applying to.

Also, don’t just state the weakness. Provide context on how it has affected your student life and the steps you’re taking to improve.

1. Fear of Failure

It’s not uncommon for students to experience the fear of failure, and it is not something to be ashamed of either. Even adults still suffer from it.

The fear of failure keeps students from performing optimally and challenging themselves. It also makes them unable to concentrate on their studies as the anxiety overwhelms them.

If this sounds like you, when listing it among your weaknesses, you could say:

“I’d say my number one weakness is a fear of failure. Even when I had the right answer, I refused to share my thoughts in class and became envious of those who did. I have since recognized that it is not their fault, and I’ve been taking mindfulness exercises to overcome this fear.”

2. Self Criticism

image source: LifeWorks

Self-reflection is a strength. However, when you can’t recognize when you’ve done an excellent job and celebrate yourself, it becomes self-criticism and a weakness.

As a student, self-criticism can lead to burnout and self-punishment that keeps you from performing optimally or enjoying the learning environment.

Here’s how you could share this as a weakness to the student interviewer when asked in your interview question:

“Even though I receive stellar comments from teachers, I still feel like I’m not performing to the best of my ability. This has caused periods of burnout and angry outbursts. But I’ve adopted a looser schedule and am trying to be fairer to myself.”

Being apathetic as a student means you don’t care about your studies and the consequences. This mindset keeps you from seeing the value of studying and applying yourself accordingly.

It is a typical student weakness, but answering the question truthfully can make you stand out anyway:

“After a bad result, I develop an apathetic response to my studies, which sets me back and forces me to play catchup. I’ve since recognized the pattern and now study harder to avoid bad results. I’m also learning not to let one bad result outweigh the value of other results.”

4. Impatience

image source: Ashima Pargal

Impatient students have trouble collaborating with others because they want everything done on their schedule. It can also affect how they respond to someone else’s errors or when they have to wait.

This is also a notable weakness to share with employers. Some might even see it as a strength, especially if you phrase it like one.

“I struggle to work with others because I’m fast and impatient. I can be too eager to complete a group assignment, which often leads to conflict with my peers.”

5. Lack of Focus

Lack of focus and a short attention span are common academic weaknesses for modern students. Students with this struggle to concentrate during a lecture or study for long hours.

Of course, this might not be a character trait. Some students have attention deficit disorder and need professional help.

Whatever the case may be, when you list this as a weakness, be specific about how you’re working on it.

“I struggle with paying attention in class and get bored easily when completing a task. To improve my attention span, I meditate, exercise, and take notes by hand to keep myself engaged in class.”

6. Disorganized

image source: Robert Bye

Disorganization means the inability to prioritize tasks and events. It also represents an inability to plan and allocate effort properly. More importantly, it negatively affects consistency.

These things impact the performance levels of students and a potential candidate as a weakness option to discuss during an application.

Yes, admission officers want to see students who have the organization levels to navigate the various demands of college. But combining this weakness with strengths like self-learning and openness to criticism can help you come across as an ideal candidate.

7. Disruptive

Disruptiveness doesn’t just affect your academic and career progress, but they also affect the advancement of others.

A disruptive student is more inclined to pursue their own interests, such as being the class clown or class talkative, than focusing on school work.

Being disruptive is not the ideal weakness to share on an application, but it doesn’t have to be a dealbreaker:

“I have a playful nature and enjoy being the source of fun to others, but I don’t always know how to pick my moments. This can have a disruptive effect. I’ve sought professional help, and I’m learning to decenter myself.”

8. Self-doubt

Self-doubt also means a lack of confidence. It is one of the weaknesses that puts a lower ceiling on a student’s accomplishments. A student riddled with this weakness is less likely to ask for extra credit or volunteer for extracurricular programs.

They are also less likely to be an active participant in class.

“As an introvert, I am reluctant to put myself out there and discover other activities I might be great at. I’ve been placing myself in interactions outside my comfort zone to fix this, and my confidence is improving. I believe more of this will keep the self doubt away.”

9. Stubborn

Stubborn students refuse to alter their attitude or viewpoint even in the face of better arguments. They are more likely to trigger conflict and are always determined to do what they want.

Stubbornness also makes it harder to collaborate and participate in group discussions.

Some professors and employers might appreciate this quality in a student or employee. Others resent it.

Hence, it is advisable to research the tolerable weaknesses of the field or role you are applying to.

10. Too Blunt

image source: Rodolfo Clix

Students who are too blunt might struggle to make friends, impacting how they settle into a college environment. Overly blunt students looking for part-time jobs may also struggle to work with others, especially those applying to roles with leadership responsibilities.

When you mention this weakness in your application or during an interview , clearly state you are working on it.

“I’ve been called blunt, even though I don’t always agree. Nevertheless, I’m taking communication skills classes to learn how to give feedback kindly.”

11. People Pleasing

A student who struggles with pleasing people is less likely to have boundaries and cannot say no to requests, even if it affects their studies.

They volunteer for more tasks they can handle and are unable to balance their schedules to do school work productively.

“I find it hard to say no to requests, which has affected my academics in the past. In the last six months, I’ve gotten a daily planner that helps me organize my life and keeps me from overcommitting myself.”

12. Individualist

image source: Elaine Casap

An individualist prefers to work alone. Either because they are introverts, not a fan of people, or the arrogant belief that they are better.

Neither is a positive personality trait as a student. It portrays an inability to collaborate, but it is a good weakness to share on an application.

Individualism can be both a strength and a challenge if you want to highlight leadership skills.

13. Easily Distracted

Distractible students find it hard to focus on a task or study for long periods. This sets them behind on schoolwork and negatively affects their academic performance.

Admission officers recognize this is common among students, so it is okay to acknowledge it in your application.

“I am easily distracted, but I know while it didn’t seriously impact me in high school, I have to improve my focus if I want to excel in college. I am using Lumosity and StayFocused to improve my focus, and I’ve noticed changes.”

14. Indiscipline

image source: Sam Balye

At minute levels, an undisciplined student has trouble attending classes and regularly completing assignments. In higher doses, they lack control over their behavior, disobey rules, and are a divisive presence.

It might seem unwise to list this as your weakness as a student, but doing so illustrates self introspection and an ability to hold yourself accountable.

15. Procrastination

Finally, procrastination. The bane of the education process. Students putting off work until the last moment is a universal behavior. It is a weakness employees and admission officers are familiar with and can help you stand out if you put it subtly.

“Like many students, I prefer to wait until the last moment to do schoolwork. After auditing a few classes, I’ve realized it will deeply affect my academic performance. I’ve also incorporated daily planners into my routine to allocate my time efficiently.”

What is My Strength and Weakness as a Student? – Sum Up

Sharing your strengths and weaknesses as a student isn’t a meaningless charade. It helps educators and employees assess your potential and how best to nurture and wield your competencies.

Even the research alone can help you identify things you need to better position yourself among your peers.

Lastly, when describing them, be specific and stay as honest as possible.

Tom loves to write on technology, e-commerce & internet marketing. I started my first e-commerce company in college, designing and selling t-shirts for my campus bar crawl using print-on-demand. Having successfully established multiple 6 & 7-figure e-commerce businesses (in women’s fashion and hiking gear), I think I can share a tip or 2 to help you succeed.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

SuMMarY. Critical appraisal is a systematic process used to identify the strengths. and weaknesse s of a res earch article in order t o assess the usefulness and. validity of r esearch findings ...

Abstract. Critical appraisal is a systematic process used to identify the strengths and weaknesses of a research article in order to assess the usefulness and validity of research findings. The most important components of a critical appraisal are an evaluation of the appropriateness of the study design for the research question and a careful ...

The Learning Scientists. Mar 8. Mar 8 Different Research Methods: Strengths and Weaknesses. Megan Sumeracki. For Teachers, For Parents, Learning Scientists Posts, For Students. By Megan Sumeracki. Image from Pixabay. There are a lot of different methods of conducting research, and each comes with its own set of strengths and weaknesses. I've ...

Conclusion: The ability to understand and evaluate research builds strong evidence-based practitioners, who are essential to nursing practice. Implications for practice: This framework should help readers to identify the strengths, potential weaknesses and limitations of a paper to judge its quality and potential usefulness.

An article critique requires you to critically read a piece of research and identify and evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of the article. How is a critique different from a summary? A summary of a research article requires you to share the key points of the article so your reader can get a clear picture of what the article is about.

synthesis research evidence, often adhering to guidelines on the conduct of a review. Seeks to include all knowledge on a topic Is restrictive to focusing a certain method used in studies. Systematic research and review Combines strength of critical review with a comprehensive search process. Typically addresses broad questions to produce 'best

The absence of a critical appraisal hinders the reader's ability to interpret research findings in light of the strengths and weaknesses of the methods investigators used to obtain their data. Reviewers in sport and exercise psychology who are aware of what critical appraisal is, its role in systematic reviewing, how to undertake one, and how ...

Critical appraisal is a systematic process through which the strengths and weaknesses of a research study can be identified. This process enables the reader to assess the study's usefulness and ...

Case reports should include relevant positive and negative findings from history, examination and investigation, and can include clinical photographs. Additionally, the Author must make it clear what the case adds to the field of medicine and include an up-to-date review of all previous cases. These articles should be no more than 5,000 words ...

Research & Structure. Overview of Research Process; Structure of an Academic Argument; Development & Editing. Fundamental Writing Skills for Researchers; Editing: Analyzing your writing strengths and weaknesses; Peer Feedback in Writing Groups; Developing Effective Writing Habits; Strength In Writing. Finding and Citing Literature; Writing for ...

paper from incidentals, have a good understanding of how the ideas relate to broader context, and are able to constructively critique the research process. Roughly, I'm after around half a page (at most one page) with the following: • One or two sentence summary. This is your takeaways in your own words. • Key strengths of the paper.

Common types of limitations and their ramifications include: Theoretical: limits the scope, depth, or applicability of a study. Methodological: limits the quality, quantity, or diversity of the data. Empirical: limits the representativeness, validity, or reliability of the data. Analytical: limits the accuracy, completeness, or significance of ...

Abstract. Study limitations represent weaknesses within a research design that may influence outcomes and conclusions of the research. Researchers have an obligation to the academic community to present complete and honest limitations of a presented study. Too often, authors use generic descriptions to describe study limitations.

Abstract: The purpose of this study is compared strengths and weaknesses of qualitative and quantitative research methodologies in social science fields. Reviewed recent secondary resources, there is no best approach between both research methodologies due to existing strengths and weaknesses among both types of research methodologies.

This paper presents a critical review of the strengths and weaknesses of research designs involving quantitative measures and, in particular, experimental research. The review evolved during the planning stage of a PhD project that sought to determine the effects of witnessed resuscitation on bereaved relatives.

Health is a growing concern. When looking at growth, applied science subjects have the greatest potential. The highest-growth subject across all sub specialities, with a nearly 32% CAGR, is ...

The University of Minnesota provided new students access to take the Gallup Strengths from 2011-2016. This page was created based on those results and a students "Top 5." What are your strengths? Strengths can be used to support your academic and library work from picking a topic for a research paper to finding the sources you need to citing ...

Strengths. Limitations. Complement and refine quantitative data. Findings usually cannot be generalised to the study population or community. Provide more detailed information to explain complex issues. More difficult to analyse; don't fit neatly in standard categories. Multiple methods for gathering data on sensitive subjects.

The author presents the strengths and weaknesses of peer review, analyzes the benefits and shortcomings, makes recommendations for further research, and provides information for improving future studies. With perhaps 6,000 to 7,000 scientific articles written every day ...

This paper presents a critical review of the strengths and weaknesses of research designs involving quantitative measures and, in particular, experimental research. The review evolved during the planning stage of a PhD project that sought to determine the effects of witnessed resuscitation on bereaved relatives. The discussion is therefore supported throughout by reference to bereavement ...

This paper presents a critical review of the strengths and weaknesses of research designs involving quantitative measures and, in particular, experimental research. The review evolved during the planning stage of a PhD project that sought to determine the effects of witnessed resuscitation on bereaved relatives. The discussion is therefore supported throughout by reference to bereavement ...

I do extensive research so that every client is extra prepared. Strategies for talking about weaknesses. We all have weaknesses—that's just a part of being human. But your capacity to recognise a weakness and work towards improvement can be a strength. The key to talking about your weaknesses is to pair self-awareness with an action and a result:

Each weakness can be worked on, and every strength requires consistency to stay one. With that said, here are 30 best strengths and weaknesses as a student with examples. Examples of Student Strengths. When writing about your strengths as a student, here are some examples worth mentioning. Review the list to choose what best fits your application.

DOI: 10.24173/jge.2024.04.27.5 Corpus ID: 269692739; A Study of the Critical Use of Generative Artificial Intelligence in College Writing Classes : Focusing on the strengths and weaknesses of self-introduction letters

Each method for separating and extracting agents is individually revised in terms of the mechanism and interaction of providing rare earth elements. This paper also evaluates past and current trends of these methods and technical extractants and identifies their strengths and weaknesses. Strategical elements, such as rare earth elements, play a ...