Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Effects of music therapy on depression: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials

Roles Conceptualization, Writing – original draft

Affiliation Bengbu Medical University, Bengbu, Anhui, China

Roles Methodology, Software

Affiliation Anhui Provincial Center for Women and Child Health, Hefei, Anhui, China

Roles Writing – review & editing

Affiliations Bengbu Medical University, Bengbu, Anhui, China, National Drug Clinical Trial Institution, The First Affiliated Hospital of Bengbu Medical University, Bengbu, Anhui, China

Roles Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

- Qishou Tang,

- Zhaohui Huang,

- Huan Zhou,

- Published: November 18, 2020

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0240862

- Peer Review

- Reader Comments

We aimed to determine and compare the effects of music therapy and music medicine on depression, and explore the potential factors associated with the effect.

PubMed (MEDLINE), Ovid-Embase, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, EMBASE, Web of Science, and Clinical Evidence were searched to identify studies evaluating the effectiveness of music-based intervention on depression from inception to May 2020. Standardized mean differences (SMDs) were estimated with random-effect model and fixed-effect model.

A total of 55 RCTs were included in our meta-analysis. Music therapy exhibited a significant reduction in depressive symptom (SMD = −0.66; 95% CI = -0.86 to -0.46; P <0.001) compared with the control group; while, music medicine exhibited a stronger effect in reducing depressive symptom (SMD = −1.33; 95% CI = -1.96 to -0.70; P <0.001). Among the specific music therapy methods, recreative music therapy (SMD = -1.41; 95% CI = -2.63 to -0.20; P <0.001), guided imagery and music (SMD = -1.08; 95% CI = -1.72 to -0.43; P <0.001), music-assisted relaxation (SMD = -0.81; 95% CI = -1.24 to -0.38; P <0.001), music and imagery (SMD = -0.38; 95% CI = -0.81 to 0.06; P = 0.312), improvisational music therapy (SMD = -0.27; 95% CI = -0.49 to -0.05; P = 0.001), music and discuss (SMD = -0.26; 95% CI = -1.12 to 0.60; P = 0.225) exhibited a different effect respectively. Music therapy and music medicine both exhibited a stronger effects of short and medium length compared with long intervention periods.

Conclusions

A different effect of music therapy and music medicine on depression was observed in our present meta-analysis, and the effect might be affected by the therapy process.

Citation: Tang Q, Huang Z, Zhou H, Ye P (2020) Effects of music therapy on depression: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS ONE 15(11): e0240862. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0240862

Editor: Sukru Torun, Anadolu University, TURKEY

Received: June 10, 2020; Accepted: October 4, 2020; Published: November 18, 2020

Copyright: © 2020 Tang et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting Information files.

Funding: The Key Project of University Humanities and Social Science Research in Anhui Province (SK2017A0191) was granted by Education Department of Anhui Province; the Research Project of Anhui Province Social Science Innovation Development (2018XF155) was granted by Anhui Provincial Federation of Social Sciences; the Ministry of Education Humanities and Social Sciences Research Youth fund Project (17YJC840033) was granted by Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China. These funders had a role in study design, text editing, interpretation of results, decision to publish and preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

Depression was reported to be a common mental disorders and affected more than 300 million people worldwide, and long-lasting depression with moderate or severe intensity may result in serious health problems [ 1 ]. Depression has become the leading causes of disability worldwide according to the recent World Health Organization (WHO) report. Even worse, depression was closely associated with suicide and became the second leading cause of death, and nearly 800 000 die of depression every year worldwide [ 1 , 2 ]. Although it is known that treatments for depression, more than 3/4 of people in low and middle-income income countries receive no treatment due to a lack of medical resources and the social stigma of mental disorders [ 3 ]. Considering the continuously increased disease burden of depression, a convenient effective therapeutic measures was needed at community level.

Music-based interventions is an important nonpharmacological intervention used in the treatment of psychiatric and behavioral disorders, and the obvious curative effect on depression has been observed. Prior meta-analyses have reported an obvious effect of music therapy on improving depression [ 4 , 5 ]. Today, it is widely accepted that the music-based interventions are divided into two major categories, namely music therapy and music medicine. According to the American Music Therapy Association (AMTA), “music therapy is the clinical and evidence-based use of music interventions to accomplish individualized goals within a therapeutic relationship by a credentialed professional who has completed an approved music therapy program” [ 6 ]. Therefore, music therapy is an established health profession in which music is used within a therapeutic relationship to address physical, emotional, cognitive, and social needs of individuals, and includes the triad of music, clients and qualified music therapists. While, music medicine is defined as mainly listening to prerecorded music provided by medical personnel or rarely listening to live music. In other words, music medicine aims to use music like medicines. It is often managed by a medical professional other than a music therapist, and it doesn’t need a therapeutic relationship with the patients. Therefore, the essential difference between music therapy and music medicine is about whether a therapeutic relationship is developed between a trained music therapist and the client [ 7 – 9 ]. In the context of the clear distinction between these two major categories, it is clear that to evaluate the effects of music therapy and other music-based intervention studies on depression can be misleading. While, the distinction was not always clear in most of prior papers, and no meta-analysis comparing the effects of music therapy and music medicine was conducted. Just a few studies made a comparison of music-based interventions on psychological outcomes between music therapy and music medicine. We aimed to (1) compare the effect between music therapy and music medicine on depression; (2) compare the effect between different specific methods used in music therapy; (3) compare the effect of music-based interventions on depression among different population [ 7 , 8 ].

Materials and methods

Search strategy and selection criteria.

PubMed (MEDLINE), Ovid-Embase, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, EMBASE, Web of Science, and Clinical Evidence were searched to identify studies assessing the effectiveness of music therapy on depression from inception to May 2020. The combination of “depress*” and “music*” was used to search potential papers from these databases. Besides searching for electronic databases, we also searched potential papers from the reference lists of included papers, relevant reviews, and previous meta-analyses. The criteria for selecting the papers were as follows:(1) randomised or quasi-randomised controlled trials; (2) music therapy at a hospital or community, whereas the control group not receiving any type of music therapy; (3) depression rating scale was used. The exclusive criteria were as follows: (1) non-human studies; (2) studies with a very small sample size (n<20); (3) studies not providing usable data (including sample size, mean, standard deviation, etc.); (4) reviews, letters, protocols, etc. Two authors independently (YPJ, HZH) searched and screened the relevant papers. EndNote X7 software was utilized to delete the duplicates. The titles and abstracts of all searched papers were checked for eligibility. The relevant papers were selected, and then the full-text papers were subsequently assessed by the same two authors. In the last, a panel meeting was convened for resolving the disagreements about the inclusion of the papers.

Data extraction

We developed a data abstraction form to extract the useful data: (1) the characteristics of papers (authors, publish year, country); (2) the characteristics of participators (sample size, mean age, sex ratio, pre-treatment diagnosis, study period); (3) study design (random allocation, allocation concealment, masking, selection process of participators, loss to follow-up); (4) music therapy process (music therapy method, music therapy period, music therapy frequency, minutes per session, and the treatment measures in the control group); (5) outcome measures (depression score). Two authors independently (TQS, ZH) abstracted the data, and disagreements were resolved by discussing with the third author (YPJ).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two authors independently (TQS, ZH) assessed the risk of bias of included studies using Cochrane Collaboration’s risk of bias assessment tool, and disagreements were resolved by discussing with the third author (YPJ) [ 10 ].

Music therapy and music medicine

Music Therapy is defined as the clinical and evidence-based use of music interventions to accomplish individualized goals within a therapeutic relationship by a credentialed professional who has completed an approved music therapy program. Music medicine is defined as mainly listening to prerecorded music provided by medical personnel or rarely listening to live music. In other words, music medicine aims to use music like medicines.

Music therapy mainly divided into active music therapy and receptive music therapy. Active music therapy, including improvisational, re-creative, and compositional, is defined as playing musical instruments, singing, improvisation, and lyrics of adaptation. Receptive music therapy, including music-assisted relaxation, music and imagery, guided imagery and music, lyrics analysis, and so on, is defined as music listening, lyrics analysis, and drawing with musing. In other words, in active methods participants are making music, and in receptive music therapy participants are receiving music [ 6 , 7 , 9 , 11 – 13 ].

Evaluation of depression

Depression was evaluated by the common psychological scales, including Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI), Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D), Cornell Scale (CS), Depression Mood Self-Report Inventory for Adolescence (DMSRIA), Geriatric Depression Scale-15 (GDS-15); Geriatric Depression Scale-30 (GDS-30), Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD/HAMD), Montgomery-sberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS), Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS), Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS), Short Version of Profile of Mood States (SV-POMS).

Statistical analysis

The pooled effect were estimated by using the standardized mean differences (SMDs) and its 95% confidence interval (95% CI) due to the different depression rate scales were used in the included papers. Heterogeneity between studies was assessed by I-square ( I 2 ) and Q-statistic (P<0.10), and a high I 2 (>50%) was recognized as heterogeneity and a random-effect model was used [ 14 – 16 ]. We performed subgroup analyses and meta-regression analyses to study the potential heterogeneity between studies. The subgroup variables included music intervention categories (music therapy and music medicine), music therapy methods (active music therapy, receptive music therapy), specific receptive music therapy methods (music-assisted relaxation, music and imagery, and guided imagery and music (Bonny Method), specific active music therapy methods (recreative music therapy and improvisational music therapy), music therapy mode (group therapy, individual therapy), music therapy period (weeks) (2–4, 5–12, ≥13), music therapy frequency (once weekly, twice weekly, ≥3 times weekly), total music therapy sessions (1–4, 5–8, 9–12, 13–16, >16), time per session (minutes) (15–40, 41–60, >60), inpatient settings (secure [locked] unit at a mental health facility versus outpatient settings), sample size (20–50, ≥50 and <100, ≥100), female predominance(>80%) (no, yes), mean age (years) (<50, 50–65, >65), country having music therapy profession (no, yes), pre-treatment diagnosis (mental health, depression, severe mental disease/psychiatric disorder). We also performed sensitivity analyses to test the robustness of the results by re-estimating the pooled effects using fixed effect model, using trim and fill analysis, excluding the paper without information on music therapy, excluding the papers with more high biases, excluding the papers with small sample size (20< n<30), excluding the papers using an infrequently used scale, excluding the studies focused on the people with a severe mental disease. We investigated the publication biases by a funnel plot as well as Egger’s linear regression test [ 17 ]. The analyses were performed using Stata, version 11.0. All P-values were two-sided. A P-value of less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Characteristics of the eligible studies

Fig 1 depicts the study profile, and a total of 55 RCTs were included in our meta-analysis [ 18 – 72 ]. Of the 55 studies, 10 studies from America, 22 studies from Europe, 22 studies from Asia, and 1 study from Australia. The mean age of the participators ranged from 12 to 86; the sample size ranged from 20 to 242. A total of 16 different scales were used to evaluate the depression level of the participators. A total of 25 studies were conducted in impatient setting and 28 studies were in outpatients setting; 32 used a certified music therapist, 15 not used a certified music therapist (for example researcher, nurse), and 10 not reported relevent information. A total of 16 different depression rating scales were used in the included studies, and HADS, GDS, and BDI were the most frequently used scales ( Table 1 ).

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

PRISMA diagram showing the different steps of systematic review, starting from literature search to study selection and exclusion. At each step, the reasons for exclusion are indicated. Doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052562.g001.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0240862.g001

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0240862.t001

Of the 55 studies, only 2 studies had high risks of selection bias, and almost all of the included studies had high risks of performance bias ( Fig 2 ).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0240862.g002

The overall effects of music therapy

Of the included 55 studies, 39 studies evaluated the music therapy, 17 evaluated the music medicine. Using a random-effects model, music therapy was associated with a significant reduction in depressive symptoms with a moderate-sized mean effect (SMD = −0.66; 95% CI = -0.86 to -0.46; P <0.001), with a high heterogeneity across studies ( I 2 = 83%, P <0.001); while, music medicine exhibited a stronger effect in reducing depressive symptom (SMD = −1.33; 95% CI = -1.96 to -0.70; P <0.001) ( Fig 3 ).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0240862.g003

Twenty studies evaluated the active music therapy using a random-effects model, and a moderate-sized mean effect (SMD = −0.57; 95% CI = -0.90 to -0.25; P <0.001) was observed with a high heterogeneity across studies ( I 2 = 86.3%, P <0.001). Fourteen studies evaluated the receptive music therapy using a random-effects model, and a moderate-sized mean effect (SMD = −0.73; 95% CI = -1.01 to -0.44; P <0.001) was observed with a high heterogeneity across studies ( I 2 = 76.3%, P <0.001). Five studies evaluated the combined effect of active and receptive music therapy using a random-effects model, and a moderate-sized mean effect (SMD = −0.88; 95% CI = -1.32 to -0.44; P <0.001) was observed with a high heterogeneity across studies ( I 2 = 70.5%, P <0.001) ( Fig 4 ).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0240862.g004

Among specific music therapy methods, recreative music therapy (SMD = -1.41; 95% CI = -2.63 to -0.20; P <0.001), guided imagery and music (SMD = -1.08; 95% CI = -1.72 to -0.43; P <0.001), music-assisted relaxation (SMD = -0.81; 95% CI = -1.24 to -0.38; P <0.001), music and imagery (SMD = -0.38; 95% CI = -0.81 to 0.06; P = 0.312), improvisational music therapy (SMD = -0.27; 95% CI = -0.49 to -0.05; P = 0.001), and music and discuss (SMD = -0.26; 95% CI = -1.12 to 0.60; P = 0.225) exhibited a different effect respectively ( Fig 5 ).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0240862.g005

Sub-group analyses and meta-regression analyses

We performed sub-group analyses and meta-regression analyses to study the homogeneity. We found that music therapy yielded a superior effect on reducing depression in the studies with a small sample size (20–50), with a mean age of 50–65 years old, with medium intervention frequency (<3 times weekly), with more minutes per session (>60 minutes). We also found that music therapy exhibited a superior effect on reducing depression among people with severe mental disease /psychiatric disorder and depression compared with mental health people. While, whether the country have the music therapy profession, whether the study used group therapy or individual therapy, whether the study was in the outpatients setting or the inpatient setting, and whether the study used a certified music therapist all did not exhibit a remarkable different effect ( Table 2 ). Table 2 also presents the subgroup analysis of music medicine on reducing depression.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0240862.t002

In the subgroup analysis by total session, music therapy and music medicine both exhibited a stronger effects of short (1–4 sessions) and medium length (5–12 sessions) compared with long intervention periods (>13sessions) ( Fig 6 ). Meta-regression demonstrated that total music intervention session was significantly associated with the homogeneity between studies ( P = 0.004) ( Table 3 ).

A, evaluating the effect of music therapy; B, evaluating the effect of music medicine.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0240862.g006

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0240862.t003

Sensitivity analyses

We performed sensitivity analyses and found that re-estimating the pooled effects using fixed effect model, using trim and fill analysis, excluding the paper without information regarding music therapy, excluding the papers with more high biases, excluding the papers with small sample size (20< n<30), excluding the studies focused on the people with a severe mental disease, and excluding the papers using an infrequently used scale yielded the similar results, which indicated that the primary results was robust ( Table 4 ).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0240862.t004

Evaluation of publication bias

We assessed publication bias using Egger’s linear regression test and funnel plot, and the results are presented in Fig 7 . For the main result, the observed asymmetry indicated that either the absence of papers with negative results or publication bias.

A, evaluating the publication bias of music therapy; B, evaluating the publication bias of music medicine; BDI = Beck Depression Inventory; CDI = Children’s Depression Inventory; CDSS = depression scale for schizophrenia; CES-D = Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression; CS = Cornell Scale; DMSRIA = Depression Mood Self-Report Inventory for Adolescence; EPDS = Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; GDS-15 = Geriatric Depression Scale-15; GDS-30 = Geriatric Depression Scale-30; HADS = Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; HRSD (HAMD) = Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; MADRS = Montgomery-sberg Depression Rating Scale; PROMIS = Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System; SDS = Self-Rating Depression Scale; State-Trait Depression Questionnaire = ST/DEP; SV-POMS = short version of Profile of Mood Stat.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0240862.g007

Our present meta-analysis exhibited a different effect of music therapy and music medicine on reducing depression. Different music therapy methods also exhibited a different effect, and the recreative music therapy and guided imagery and music yielded a superior effect on reducing depression compared with other music therapy methods. Furthermore, music therapy and music medicine both exhibited a stronger effects of short and medium length compared with long intervention periods. The strength of this meta-analysis was the stable and high-quality result. Firstly, the sensitivity analyses performed in this meta-analysis yielded similar results, which indicated that the primary results were robust. Secondly, considering the insufficient statistical power of small sample size, we excluded studies with a very small sample size (n<20).

Some prior reviews have evaluated the effects of music therapy for reducing depression. These reviews found a significant effectiveness of music therapy on reducing depression among older adults with depressive symptoms, people with dementia, puerpera, and people with cancers [ 4 , 5 , 73 – 76 ]. However, these reviews did not differentiate music therapy from music medicine. Another paper reviewed the effectiveness of music interventions in treating depression. The authors included 26 studies and found a signifiant reduction in depression in the music intervention group compared with the control group. The authors made a clear distinction on the definition of music therapy and music medicine; however, they did not include all relevant data from the most recent trials and did not conduct a meta-analysis [ 77 ]. A recent meta-analysis compared the effects of music therapy and music medicine for reducing depression in people with cancer with seven RCTs; the authors found a moderately strong, positive impact of music intervention on depression, but found no difference between music therapy and music medicine [ 78 ]. However, our present meta-analysis exhibited a different effect of music therapy and music medicine on reducing depression, and the music medicine yielded a superior effect on reducing depression compared with music therapy. The different effect of music therapy and music medicine might be explained by the different participators, and nine studies used music therapy to reduce the depression among people with severe mental disease /psychiatric disorder, while no study used music medicine. Furthermore, the studies evaluating music therapy used more clinical diagnostic scale for depressive symptoms.

A meta-analysis by Li et al. [ 74 ] suggested that medium-term music therapy (6–12 weeks) was significantly associated with improved depression in people with dementia, but not short-term music therapy (3 or 4 weeks). On the contrary, our present meta-analysis found a stronger effect of short-term (1–4 weeks) and medium-term (5–12 weeks) music therapy on reducing depression compared with long-term (≥13 weeks) music therapy. Consistent with the prior meta-analysis by Li et al., no significant effect on depression was observed for the follow-up of one or three months after music therapy was completed in our present meta-analysis. Only five studies analyzed the therapeutic effect for the follow-up periods after music therapy intervention therapy was completed, and the rather limited sample size may have resulted in this insignificant difference. Therefore, whether the therapeutic effect was maintained in reducing depression when music therapy was discontinued should be explored in further studies. In our present meta-analysis, meta-regression results demonstrated that no variables (including period, frequency, method, populations, and so on) were significantly associated with the effect of music therapy. Because meta-regression does not provide sufficient statistical power to detect small associations, the non-significant results do not completely exclude the potential effects of the analyzed variables. Therefore, meta-regression results should be interpreted with caution.

Our meta-analysis has limitations. First, the included studies rarely used masked methodology due to the nature of music therapy, therefore the performance bias and the detection bias was common in music intervention study. Second, a total of 13 different scales were used to evaluate the depression level of the participators, which may account for the high heterogeneity among the trials. Third, more than half of those included studies had small sample sizes (<50), therefore the result should be explicated with caution.

Our present meta-analysis of 55 RCTs revealed a different effect of music therapy and music medicine, and different music therapy methods also exhibited a different effect. The results of subgroup analyses revealed that the characters of music therapy were associated with the therapeutic effect, for example specific music therapy methods, short and medium-term therapy, and therapy with more time per session may yield stronger therapeutic effect. Therefore, our present meta-analysis could provide suggestion for clinicians and policymakers to design therapeutic schedule of appropriate lengths to reduce depression.

Supporting information

S1 checklist. prisma checklist..

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0240862.s001

S1 Dataset.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0240862.s002

- 1. World Health Organization. Depression. 2017. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs369/en/ .

- View Article

- Google Scholar

- PubMed/NCBI

- 6. American Music Therapy Association (2020). Definition and Quotes about Music Therapy. Available online at: https://www.musictherapy.org/about/quotes/ (Accessed Sep 13, 2020).

- 9. Wigram Tony. Inge Nyggard Pedersen&Lars Ole Bonde, A Compmhensire Guide to Music Therapy. London and Philadelphia: Jessica Kingsley Publishers. 2002:143. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0387-7604(02)00058-x pmid:12142064

- 10. Higgins J, Altman D, Sterne J. Chapter 8: Assessing risk of bias in included studies. In I. J. Higgins, R. Churchill, J. Chandler &M. Cumpston (Eds.), Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 5.2.0 (updated June 2017). Cochrane 2017.

- 11. Wheeler BL. Music Therapy Handbook. New York, New York, USA: Guilford Publications, 2015.

- 12. Bruscia KE. Defining Music Therapy. 3rd Edition. University Park, Illinois, USA: Barcelona Publishers, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2013-06-507582 pmid:24574460

- 13. Wigram Tony. Inge Nyggard Pedersen&Lars Ole Bonde, A Compmhensire Guide to Music Therapy. London and Philadelphia: Jessica Kingsley Publishen. 2002: 143. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0387-7604(02)00058-x pmid:12142064

- 52. Radulovic R. The using of music therapy in treatment of depressive disorders. Summary of Master Thesis. Belgrade: Faculty of Medicine University of Belgrade, 1996.

REVIEW article

The state of music therapy studies in the past 20 years: a bibliometric analysis.

- 1 School of Kinesiology, Shanghai University of Sport, Shanghai, China

- 2 Department of Sport Rehabilitation, Shanghai University of Sport, Shanghai, China

- 3 Department of Sport Rehabilitation Medicine, Shanghai Shangti Orthopedic Hospital, Shanghai, China

Purpose: Music therapy is increasingly being used to address physical, emotional, cognitive, and social needs of individuals. However, publications on the global trends of music therapy using bibliometric analysis are rare. The study aimed to use the CiteSpace software to provide global scientific research about music therapy from 2000 to 2019.

Methods: Publications between 2000 and 2019 related to music therapy were searched from the Web of Science (WoS) database. The CiteSpace V software was used to perform co-citation analysis about authors, and visualize the collaborations between countries or regions into a network map. Linear regression was applied to analyze the overall publication trend.

Results: In this study, a total of 1,004 studies met the inclusion criteria. These works were written by 2,531 authors from 1,219 institutions. The results revealed that music therapy publications had significant growth over time because the linear regression results revealed that the percentages had a notable increase from 2000 to 2019 ( t = 14.621, P < 0.001). The United States had the largest number of published studies (362 publications), along with the following outputs: citations on WoS (5,752), citations per study (15.89), and a high H-index value (37). The three keywords “efficacy,” “health,” and “older adults,” emphasized the research trends in terms of the strongest citation bursts.

Conclusions: The overall trend in music therapy is positive. The findings provide useful information for music therapy researchers to identify new directions related to collaborators, popular issues, and research frontiers. The development prospects of music therapy could be expected, and future scholars could pay attention to the clinical significance of music therapy to improve the quality of life of people.

Introduction

Music therapy is defined as the evidence-based use of music interventions to achieve the goals of clients with the help of music therapists who have completed a music therapy program ( Association, 2018 ). In the United States, music therapists must complete 1,200 h of clinical training and pass the certification exam by the Certification Board for Music Therapists ( Devlin et al., 2019 ). Music therapists use evidence-based music interventions to address the mental, physical, or emotional needs of an individual ( Gooding and Langston, 2019 ). Also, music therapy is used as a solo standard treatment, as well as co-treatment with other disciplines, to address the needs in cognition, language, social integration, and psychological health and family support of an individual ( Bronson et al., 2018 ). Additionally, music therapy has been used to improve various diseases in different research areas, such as rehabilitation, public health, clinical care, and psychology ( Devlin et al., 2019 ). With neurorehabilitation, music therapy has been applied to increase motor activities in people with Parkinson's disease and other movement disorders ( Bernatzky et al., 2004 ; Devlin et al., 2019 ). However, limited reviews about music therapy have utilized universal data and conducted massive retrospective studies using bibliometric techniques. Thus, this study demonstrates music therapy with a broad view and an in-depth analysis of the knowledge structure using bibliometric analysis of articles and publications.

Bibliometrics turns the major quantitative analytical tool that is used in conducting in-depth analyses of publications ( Durieux and Gevenois, 2010 ; Gonzalez-Serrano et al., 2020 ). There are three types of bibliometric indices: (a) the quantity index is used to determine the number of relevant publications, (b) the quality index is employed to explore the characteristics of a scientific topic in terms of citations, and (c) the structural index is used to show the relationships among publications ( Durieux and Gevenois, 2010 ; Gonzalez-Serrano et al., 2020 ). In this study, the three types of bibliometric indices will be applied to conduct an in-depth analysis of publications in this frontier.

While research about music therapy is extensively available worldwide, relatively limited studies use bibliometric methods to analyze the global research about this topic. The aim of this study is to use the CiteSpace software to perform a bibliometric analysis of music therapy research from 2000 to 2019. CiteSpace V is visual analytic software, which is often utilized to perform bibliometric analyses ( Falagas et al., 2008 ; Ellegaard and Wallin, 2015 ). It is also a tool applied to detect trends in global scientific research. In this study, the global music therapy research includes publication outputs, distribution and collaborations between authors/countries or regions/institutions, intense issues, hot articles, common keywords, productive authors, and connections among such authors in the field. This study also provides helpful information for researchers in their endeavor to identify gaps in the existing literature.

Materials and Methods

Search strategy.

The data used in this study were obtained from WoS, the most trusted international citation database in the world. This database, which is run by Thomson & Reuters Corporation ( Falagas et al., 2008 ; Durieux and Gevenois, 2010 ; Chen C. et al., 2012 ; Ellegaard and Wallin, 2015 ; Miao et al., 2017 ; Gonzalez-Serrano et al., 2020 ), provides high-quality journals and detailed information about publications worldwide. In this study, publications were searched from the WoS Core Collection database, which included eight indices ( Gonzalez-Serrano et al., 2020 ). This study searched the publications from two indices, namely, the Science Citation Index Expanded and the Social Sciences Citation Index. As the most updated publications about music therapy were published in the 21st century, publications from 2000 to 2019 were chosen for this study. We performed data acquisition on July 26, 2020 using the following search terms: title = (“music therapy”) and time span = 2000–2019.

Inclusion Criteria

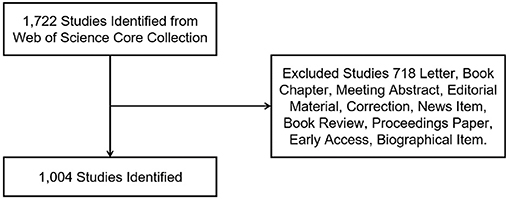

Figure 1 presents the inclusion criteria. The title field was music therapy (TI = music therapy), and only reviews and articles were chosen as document types in the advanced search. Other document types, such as letters, editorial materials, and book reviews, were excluded. Furthermore, there were no species limitations set. This advanced search process returned 718 articles. In the end, a total of 1,004 publications were obtained and were analyzed to obtain comprehensive perspectives on the data.

Figure 1 . Flow chart of music therapy articles and reviews inclusion.

Data Extraction

Author Lin-Man Weng extracted the publications and applied the EndNote software and Microsoft Excel 2016 to conduct analysis on the downloaded publications from the WoS database. Additionally, we extracted and recorded some information of the publications, such as citation frequency, institutions, authors' countries or regions, and journals as bibliometric indicators. The H-index is utilized as a measurement of the citation frequency of the studies for academic journals or researchers ( Wang et al., 2019 ).

Analysis Methods

The objective of bibliometrics can be described as the performance of studies that contributes to advancing the knowledge domain through inferences and explanations of relevant analyses ( Castanha and Grácio, 2014 ; Merigó et al., 2019 ; Mulet-Forteza et al., 2021 ). CiteSpace V is a bibliometric software that generates information for better visualization of data. In this study, the CiteSpace V software was used to visualize six science maps about music therapy research from 2000 to 2019: the network of author co-citation, collaboration network among countries and regions, relationship of institutions interested in the field, network map of co-citation journals, network map of co-cited references, and the map (timeline view) of references with co-citation on top music therapy research. As noted, a co-citation is produced when two publications receive a citation from the same third study ( Small, 1973 ; Merigó et al., 2019 ).

In addition, a science map typically features a set of points and lines to present collaborations among publications ( Chen, 2006 ). A point is used to represent a country or region, author, institution, journal, reference, or keyword, whereas a line represents connections among them ( Zheng and Wang, 2019 ), with stronger connections indicated by wider lines. Furthermore, the science map includes nodes, which represent the citation frequencies of certain themes. A burst node in the form of a red circle in the center indicates the number of co-occurrence or citation that increases over time. A purple node represents centrality, which indicates the significant knowledge presented by the data ( Chen, 2006 ; Chen H. et al., 2012 ; Zheng and Wang, 2019 ). The science map represents the keywords and references with citation bursts. Occurrence bursts represent the frequency of a theme ( Chen, 2006 ), whereas citation bursts represent the frequency of the reference. The citation bursts of keywords and references explore the trends and indicate whether the relevant authors have gained considerable attention in the field ( Chen, 2006 ). Through this kind of map, scholars can better understand emerging trends and grasp the hot topics by burst detection analysis ( Liang et al., 2017 ; Miao et al., 2017 ).

Publication Outputs and Time Trends

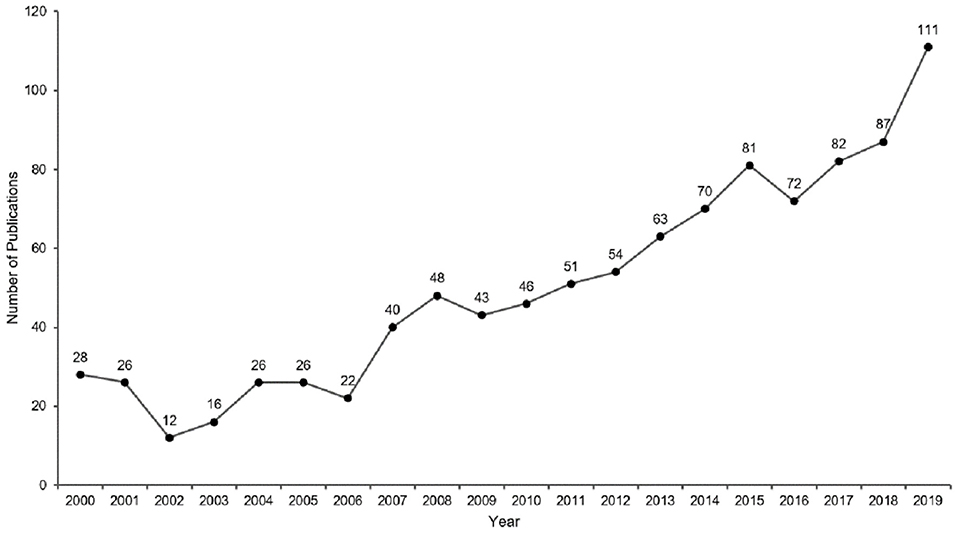

A total of 1,004 articles and reviews related to music therapy research met the criteria. The details of annual publications are presented in Figure 2 . As can be seen, there were <30 annual publications between 2000 and 2006. The number of publications increased steadily between 2007 and 2015. It was 2015, which marked the first time over 80 articles or reviews were published. The significant increase in publications between 2018 and 2019 indicated that a growing number of researchers became interested in this field. Linear regression can be used to analyze the trends in publication outputs. In this study, the linear regression results revealed that the percentages had a notable increase from 2000 to 2019 ( t = 14.621, P < 0.001). Moreover, the P < 0.05, indicating statistical significance. Overall, the publication outputs increased from 2000 to 2019.

Figure 2 . Annual publication outputs of music therapy from 2000 to 2019.

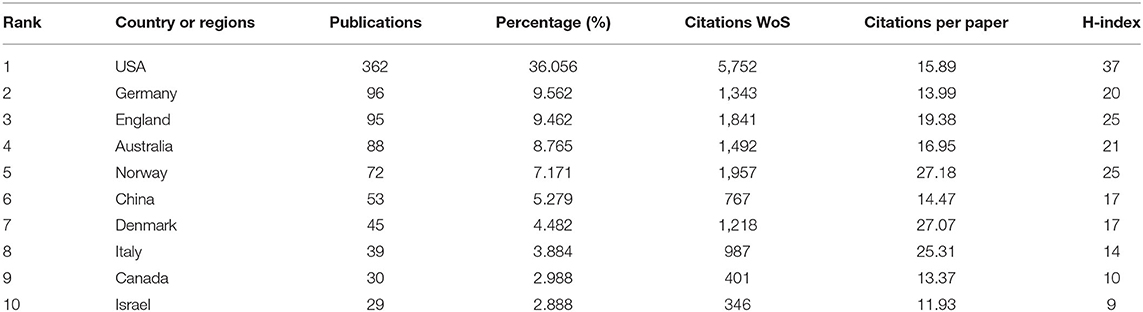

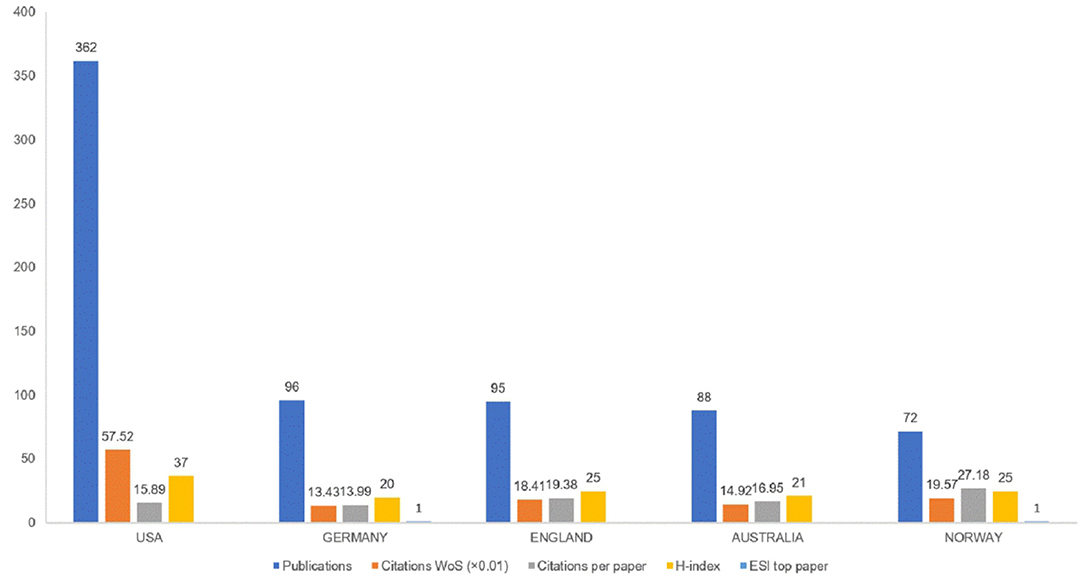

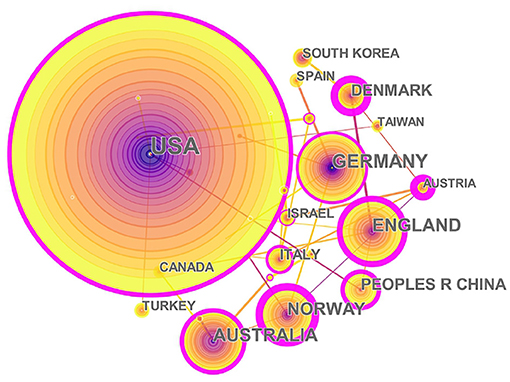

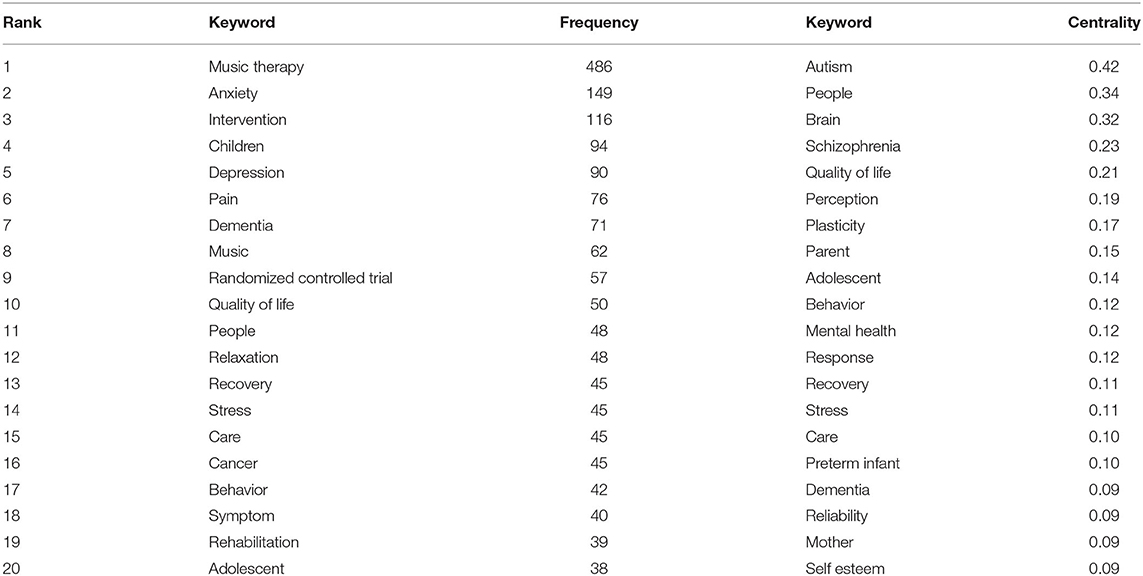

Distribution by Country or Region and Institution

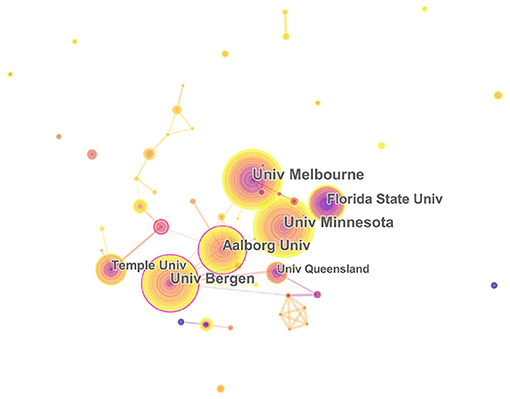

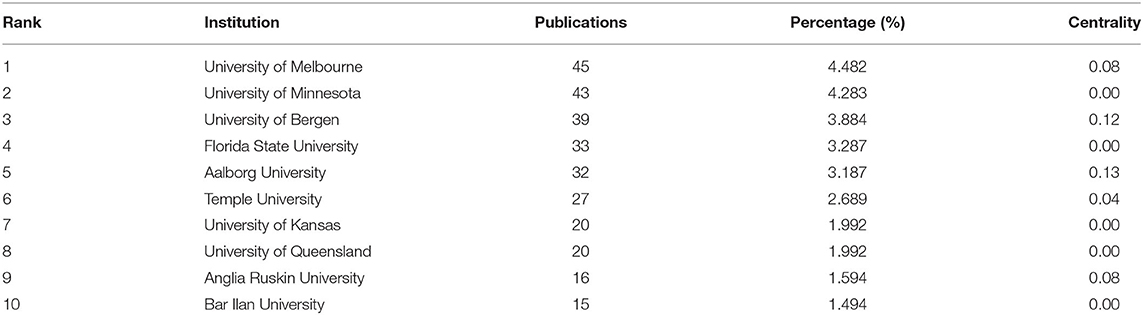

The 1,004 articles and reviews collected were published in 49 countries and regions. Table 1 presents the top 10 countries or regions. Figure 3 shows an intuitive comparison of the citations on WoS, citations per study, Hirsch index (H-index), and major essential science indicator (ESI) studies of the top five countries or regions. The H-index is a kind of index that is applied in measuring the wide impact of the scientific achievements of authors. The United States had the largest number of published studies (362 publications), along with the following outputs: citations on WoS (5,752), citations per study (15.89), and a high H-index value (37). Norway has the largest number of citations per study (27.18 citations). Figure 4 presents the collaboration networks among countries or regions. The collaboration network map contained 32 nodes and 38 links. The largest node can be found in the United States, which meant that the United States had the largest number of publications in the field. Meanwhile, the deepest purple circle was located in Austria, which meant that Austria is the country with the most number of collaborations with other countries or regions in this research field. A total of 1,219 institutions contributed various music therapy-related publications. Figure 5 presents the collaborations among institutions. As can be seen, the University of Melbourne is the most productive institution in terms of the number of publications (45), followed by the University of Minnesota (43), and the University of Bergen (39). The top 10 institutions featured in Table 2 contributed 28.884% of the total articles and reviews published. Among these, Aalborg University had the largest centrality (0.13). The top 10 productive institutions with details are shown in Table 2 .

Table 1 . Top 10 countries or regions of origin of study in the music therapy research field.

Figure 3 . Publications, citations on WoS (×0.01), citations per study, H-index, and ESL top study among top five countries or regions.

Figure 4 . The collaborations of countries or regions interested in the field. In this map, the node represents a country, and the link represents the cooperation relationship between two countries. A larger node represents more publications in the country. A thicker purple circle represents greater influence in this field.

Figure 5 . The relationship of institutions interested in the field. University of Melbourne, Florida State University, University of Minnesota, Aalborg University, Temple University, University of Queensland, and University of Bergen. In this map, the node represents an institution, and the link represents the cooperation relationship between two institutions. A larger node represents more publications in the institution. A thicker purple circle represents greater influence in this field.

Table 2 . Top 10 institutions that contributed to publications in the music therapy field.

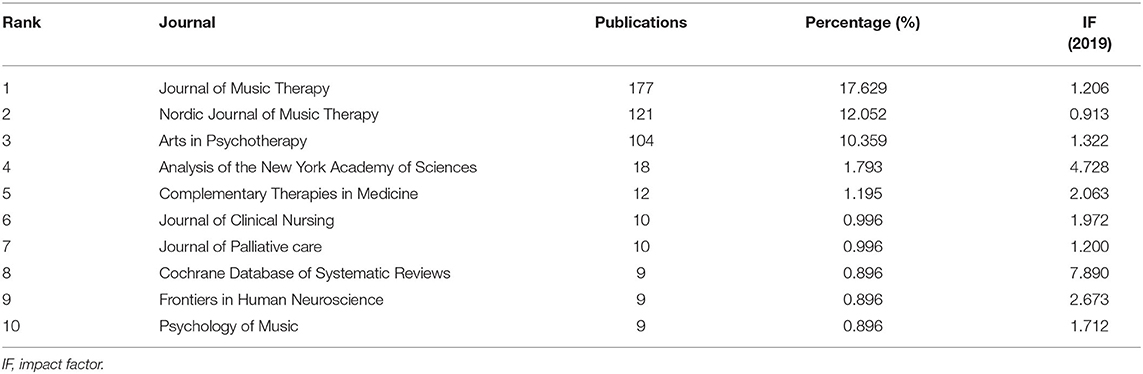

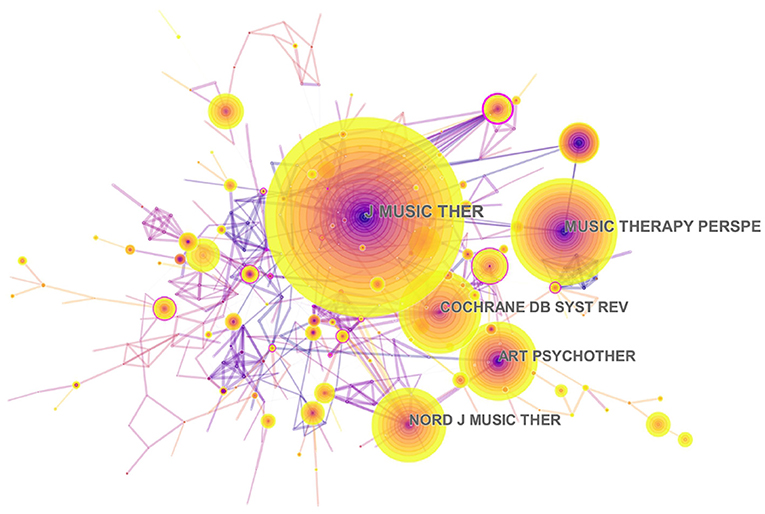

Distribution by Journals

Table 3 presents the top 10 journals that published articles or reviews in the music therapy field. The publications are mostly published in these journal fields, such as Therapy, Medical, Psychology, Neuroscience, Health and Clinical Care. The impact factors (IF) of these journals ranged between 0.913 and 7.89 (average IF: 2.568). Four journals had an impact factor >2, of which Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews had the highest IF, 2019 = 7.89. In addition, the Journal of Music Therapy (IF: 2019 = 1.206) published 177 articles or reviews (17.629%) about music therapy in the past two decades, followed by the Nordic Journal of Music Therapy (121 publications, 12.052%, IF: 2019 = 0.913), and Arts in Psychotherapy (104 publications, 10.359%, IF: 2019 = 1.322). Furthermore, the map of the co-citation journal contained 393 nodes and 759 links ( Figure 6 ). The high co-citation count identifies the journals with the greatest academic influence and key positions in the field. The Journal of Music Therapy had the maximum co-citation counts (658), followed by Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (281), and Arts in Psychotherapy (279). Therefore, according to the analysis of the publications and co-citation counts, the Journal of Music Therapy and Arts in Psychotherapy occupied key positions in this research field.

Table 3 . Top 10 journals that published articles in the music therapy field.

Figure 6 . Network map of co-citation journals engaged in music therapy from 2000 to 2019. Journal of Music Therapy, Arts in Psychotherapy, Nordic Journal of Music Therapy, Music Therapy Perspectives, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. In this map, the node represents a journal, and the link represents the co-citation frequency between two journals. A larger node represents more publications in the journal. A thicker purple circle represents greater influence in this field.

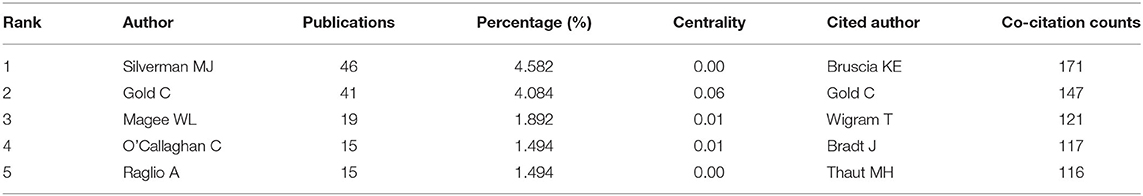

Distribution by Authors

A total of 2,531 authors contributed to the research outputs related to music therapy. Author Silverman MJ published most of the studies (46) in terms of number of publications, followed by Gold C (41), Magee WL (19), O'Callaghan C (15), and Raglio A (15). According to co-citation counts, Bruscia KE (171 citations) was the most co-cited author, followed by Gold C (147 citations), Wigram T (121 citations), and Bradt J (117 citations), as presented in Table 4 . In Figure 7 , these nodes highlight the co-citation networks of the authors. The large-sized node represented author Bruscia KE, indicating that this author owned the most co-citations. Furthermore, the linear regression results revealed a remarkable increase in the percentages of multiple articles of authors ( t = 13.089, P < 0.001). These also indicated that cooperation among authors had increased remarkably, which can be considered an important development in music therapy research.

Table 4 . Top five authors of publications and top five authors of co-citation counts.

Figure 7 . The network of author co-citaion. In this map, the node represents an author, and the link represents the co-citation frequency between two authors. A larger node represents more publications of the author. A thicker purple circle represents greater influence in this field.

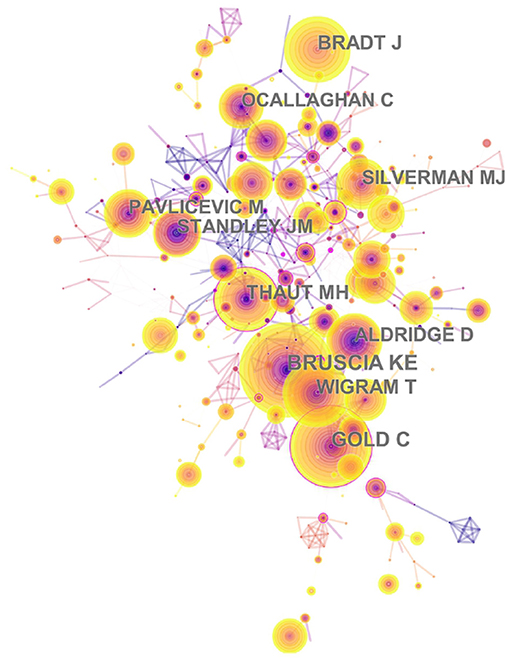

Analysis of Keywords

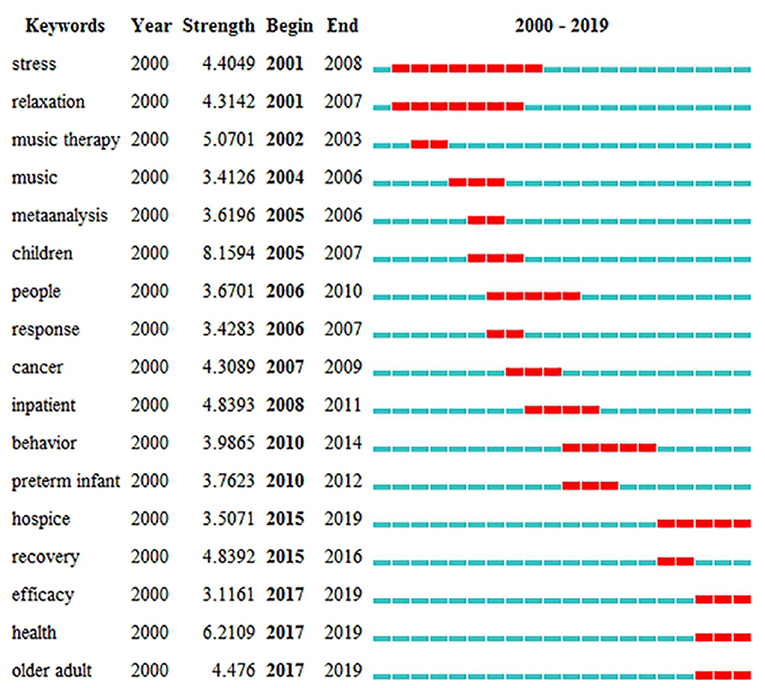

The results of keywords analysis indicated research hotspots and help scholars identify future research topics. Table 5 highlights 20 keywords with the most frequencies, such as “music therapy,” “anxiety,” “intervention,” “children,” and “depression.” The keyword “autism” has the highest centrality (0.42). Figure 8 shows the top 17 keywords with the strongest citation bursts. By the end of 2019, keyword bursts were led by “hospice,” which had the strongest burst (3.5071), followed by “efficacy” (3.1161), “health” (6.2109), and “older adult” (4.476).

Table 5 . Top 20 keywords with the most frequency and centrality in music therapy study.

Figure 8 . The strongest citation bursts of the top 17 keywords. The red measures indicate frequent citation of keywords, and the green measures indicate infrequent citation of keywords.

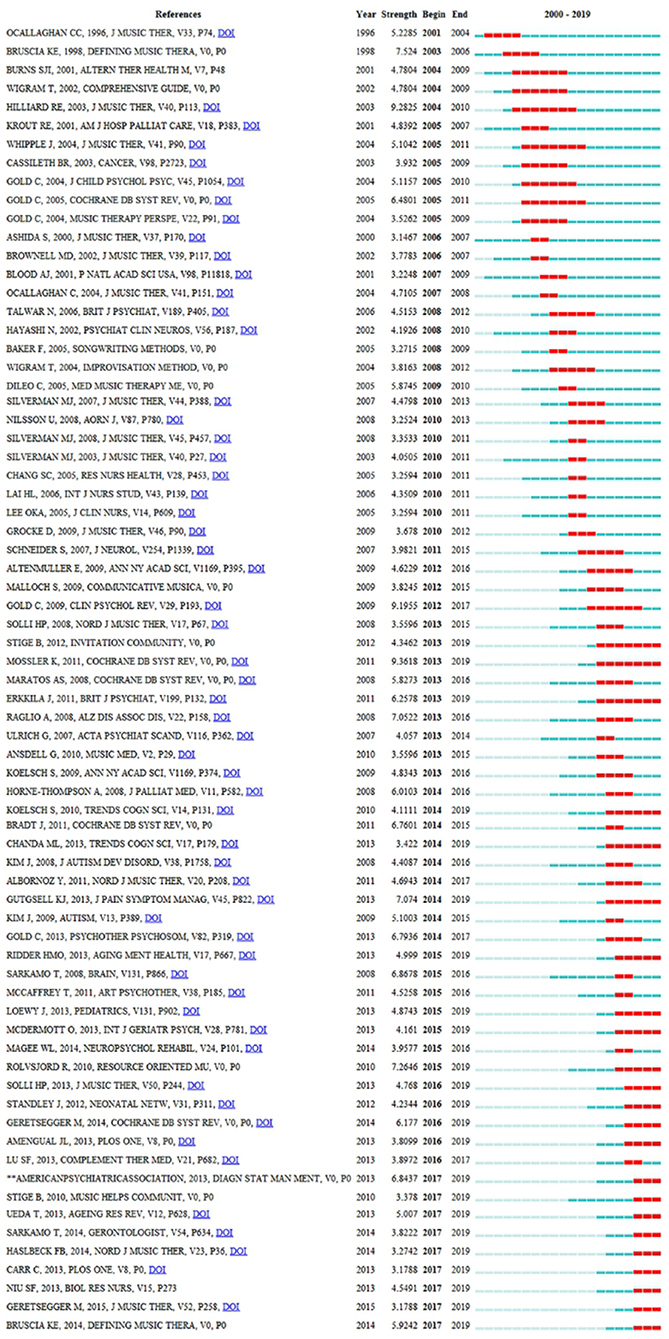

Analysis of Co-cited References

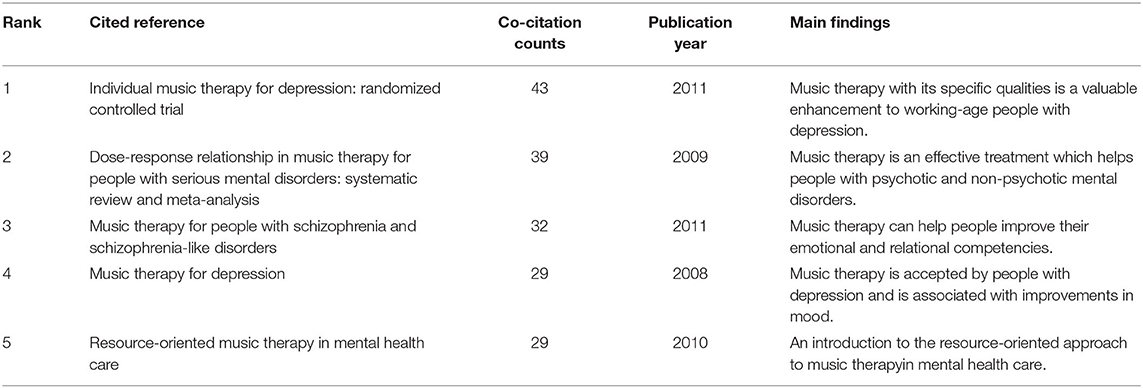

The analysis of co-cited references is a significant indicator in the bibliometric method ( Chen, 2006 ). The top five co-cited references and their main findings are listed in Table 6 . These are regarded as fundamental studies for the music therapy knowledge base. In terms of co-citation counts, “individual music therapy for depression: randomized controlled trial” was the key reference because it had the most co-citation counts. This study concludes that music therapy mixed with standard care is an effective way to treat working-age people with depression. The authors also explained that music therapy is a valuable enhancement to established treatment practices ( Erkkilä et al., 2011 ). Meanwhile, the strongest citation burst of reference is regarded as the main knowledge of the trend ( Fitzpatrick, 2005 ). Figure 9 highlights the top 71 strongest citation bursts of references from 2000 to 2019. As can be seen, by the end of 2019, the reference burst was led by author Stige B, and the strongest burst was 4.3462.

Table 6 . Top five co-cited references with co-citation counts in the study of music therapy from 2000 to 2019.

Figure 9 . The strongest citation bursts among the top 71 references. The red measures indicate frequent citation of studies, and the green measures indicate infrequent citation of studies.

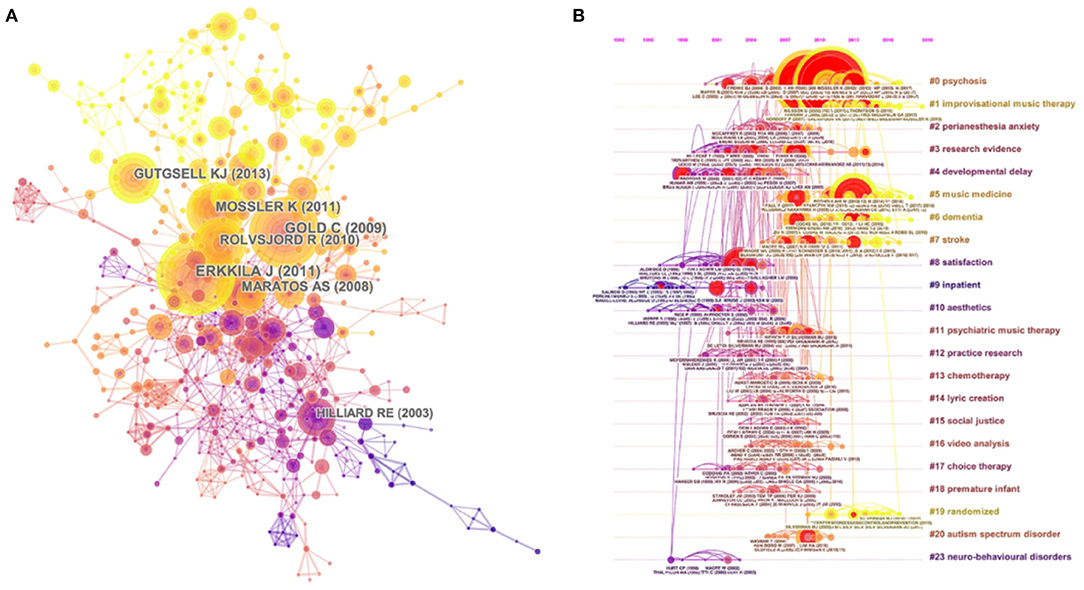

Figure 10A presents the co-cited reference map containing 577 nodes and 1,331 links. The figure explains the empirical relevance of a considerable number of articles and reviews. Figure 10B presents the co-citation map (timeline view) of reference from publications on top music therapy research. The timeline view of clusters shows the research progress of music therapy in a particular period of time and the thematic concentration of each cluster. “Psychosis” was labeled as the largest cluster (#0), followed by “improvisational music therapy” (#1) and “paranesthesia anxiety” (#2). These clusters have also remained hot topics in recent years. Furthermore, the result of the modularity Q score was 0.8258. That this value exceeded 0.5 indicated that the definitions of the subdomain and characters of clusters were distinct. In addition, the mean silhouette was 0.5802, which also exceeded 0.5. The high homogeneity of individual clusters indicated high concentration in different research areas.

Figure 10. (A) The network map of co-cited references and (B) the map (timeline view) of references with co-citation on top music therapy research. In these maps, the node represents a study, and the link represents the co-citation frequency between two studies. A larger node represents more publications of the author. A thicker purple circle represents greater influence in this field. (A) The nodes in the same color belong to the same cluster. (B) The nodes on the same line belong to the same cluster.

Global Trends in Music Therapy Research

This study conducted a bibliometric analysis of music therapy research from the past two decades. The results, which reveal that music therapy studies have been conducted throughout the world, among others, can provide further research suggestions to scholars. In terms of the general analysis of the publications, the features of published articles and reviews, prolific countries or regions, and productive institutions are summarized below.

I. The distribution of publication year has been increasing in the past two decades. The annual publication outputs of music therapy from 2000 to 2019 were divided into three stages: beginning, second, and third. In the beginning stage, there were <30 annual publications from 2000 to 2006. The second stage was between 2007 and 2014. The number of publications increased steadily. It was 2007, which marked the first time 40 articles or reviews were published. The third stage was between 2015 and 2019. The year 2015 was the key turning point because it was the first time 80 articles or reviews were published. The number of publications showed a downward trend in 2016 (72), but it was still higher than the average number of the previous years. Overall, music therapy-related research has received increasing attention among scholars from 2000 to 2020.

II. The articles and reviews covered about 49 countries or regions, and the prolific countries or regions were mainly located in the North American and European continents. According to citations on WoS, citations per study, and the H-index, music therapy publications from developed countries, such as United States and Norway, have greater influence than those from other countries. In addition, China, as a model of a developing country, had published 53 studies and ranked top six among productive countries.

III. In terms of the collaboration map of institutions, the most productive universities engaged in music therapy were located in the United States, namely, University of Minnesota (43 publications), Florida State University (33 publications), Temple University (27 publications), and University of Kansas (20 publications). It indicated that institutions in the US have significant impacts in this area.

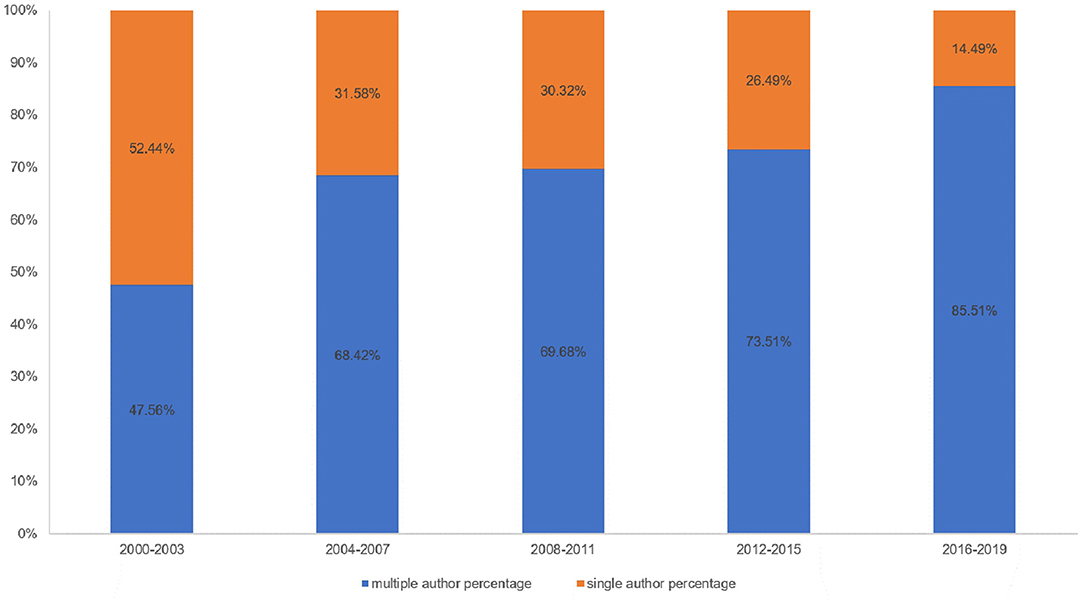

IV. According to author co-citation counts, scholars can focus on the publications of such authors as Bruscia KE, Gold C, and Wigram T. These three authors come from the United States, Norway, and Denmark, and it also reflected that these three countries are leading the research trend. Author Bruscia KE has the largest co-citation counts and is based at Temple University. He published many music therapy studies about assessment and clinical evaluation in music therapy, music therapy theories, and therapist experiences. These publications laid a foundation and facilitate the development of music therapy. In addition, in Figure 11 , the multi-authored articles between 2000 and 2003 comprised 47.56% of the sample, whereas the publications of multi-authored articles increased significantly from 2016 to 2019 (85.51%). These indicated that cooperation is an effective factor in improving the quality of publications.

Figure 11 . The percentage of single- vs. multiple-authored articles. Blue bars mean multiple-author percentage; orange bars mean single-author percentage.

Research Focus on the Research Frontier and Hot Topics

According to the science map analysis, hot music therapy topics among publications are discussed.

I. The cluster “#1 improvisational music therapy” (IMT) is the current research frontier in the music therapy research field. In general, music therapy has a long research tradition within autism spectrum disorders (ASD), and there have been more rigorous studies about it in recent years. IMT for children with autism is described as a child-centered method. Improvisational music-making may enhance social interaction and expression of emotions among children with autism, such as responding to communication acts ( Geretsegger et al., 2012 , 2015 ). In addition, IMT is an evidence-based treatment approach that may be helpful for people who abuse drugs or have cancer. A study applied improving as a primary music therapeutic practice, and the result indicated that IMT will be effective in treating depression accompanied by drug abuse among adults ( Albornoz, 2011 ). By applying the interpretative phenomenological analysis and psychological perspectives, a study explained the significant role of music therapy as an innovative psychological intervention in cancer care settings ( Pothoulaki et al., 2012 ). IMT may serve as an effective additional method for treating psychiatric disorders in the short and medium term, but it may need more studies to identify the long-term effects in clinical practice.

II. Based on the analysis of co-citation counts, the top three references all applied music therapy to improve the quality of life of clients. They highlight the fact that music therapy is an effective method that can cover a range of clinical skills, thus helping people with psychological disorders, chronic illnesses, and pain management issues. Furthermore, music therapy mixed with standard care can help individuals with schizophrenia improve their global state, mental state (including negative and general symptoms), social functioning, and quality of life ( Gold et al., 2009 ; Erkkilä et al., 2011 ; Geretsegger et al., 2017 ).

III. By understanding the keywords with the strongest citation bursts, the research frontier can be predicted. Three keywords, “efficacy,” “health,” and “older adults,” emphasized the research trends in terms of the strongest citation bursts.

a. Efficacy: This refers to measuring the effectiveness of music therapy in terms of clinical skills. Studies have found that a wide variety of psychological disorders can be effectively treated with music. In the study of Fukui, patients with Alzheimer's disease listened to music and verbally communicated with their music therapist. The results showed that problematic behaviors of the patients with Alzheimer's disease decreased ( Fukui et al., 2012 ). The aim of the study of Erkkila was to determine the efficacy of music therapy when added to standard care. The result of this study also indicated that music therapy had specific qualities for non-verbal expression and communication when patients cannot verbally describe their inner experiences ( Erkkilä et al., 2011 ). Additionally, as summarized by Ueda, music therapy reduced anxiety and depression in patients with dementia. However, his study cannot clarify what kinds of music therapy or patients have effectiveness. Thus, future studies should investigate music therapy with good methodology and evaluation methods ( Ueda et al., 2013 ).

b. Health: Music therapy is a methodical intervention in clinical practice because it uses music experiences and relationships to promote health for adults and children ( Bruscia, 1998 ). Also, music therapy is an effective means of achieving the optimal health and well-being of individuals and communities, because it can be individualized or done as a group activity. The stimulation from music therapy can lead to conversations, recollection of memories, and expression. The study of Gold indicated that solo music therapy in routine practice is an effective addition to usual care for mental health care patients with low motivation ( Gold et al., 2013 ). Porter summarized that music therapy contributes to improvement for both kids and teenagers with mental health conditions, such as depression and anxiety, and increases self-esteem in the short term ( Porter et al., 2017 ).

c. Older adults: This refers to the use of music therapy as a treatment to maintain and slow down the symptoms observed in older adults ( Mammarella et al., 2007 ; Deason et al., 2012 ). In terms of keywords with the strongest citation bursts, the most popular subjects of music therapy-related articles and reviews focused on children from 2005 to 2007. However, various researchers concentrated on older adults from 2017 to 2019. Music therapy was the treatment of choice for older adults with depression, Parkinson's disease, and Alzheimer's disorders ( Brotons and Koger, 2000 ; Bernatzky et al., 2004 ; Johnson et al., 2011 ; Deason et al., 2012 ; McDermott et al., 2013 ; Sakamoto et al., 2013 ; Benoit et al., 2014 ; Pohl et al., 2020 ). In the study of Zhao, music therapy had positive effects on the reduction of depressive symptoms for older adults when added to standard therapies. These standard therapies could be standard care, standard drug treatment, standard rehabilitation, and health education ( Zhao et al., 2016 ). The study of Shimizu demonstrated that multitask movement music therapy was an effective intervention to enhance neural activation in older adults with mild cognitive impairment ( Shimizu et al., 2018 ). However, the findings of the study of Li explained that short-term music therapy intervention cannot improve the cognitive function of older adults. He also recommended that future researchers can apply a quality methodology with a long-term research design for the care needs of older adults ( Li et al., 2015 ).

Strengths and Limitations

To the best of our knowledge, this study was the first one to analyze large-scale data of music therapy publications from the past two decades through CiteSpace V. CiteSpace could detect more comprehensive results than simply reviewing articles and studies. In addition, the bibliometric method helped us to identify the emerging trend and collaboration among authors, institutions, and countries or regions.

This study is not without limitations. First, only articles and reviews published in the WoS Science Citation Index Expanded and Social Sciences Citation Index were analyzed. Future reviews could consider other databases, such as PubMed and Scopus. The document type labeled by publishers is not always accurate. For example, some publications labeled by WoS were not actually reviews ( Harzing, 2013 ; Yeung, 2021 ). Second, the limitation may induce bias in frequency of reference. For example, some potential articles were published recently, and these studies could be not cited with frequent times. Also, in terms of obliteration by incorporation, some common knowledge or opinions become accepted that their contributors or authors are no longer cited ( Merton, 1965 ; Yeung, 2021 ). Third, this review applied the quantitative analysis approach, and only limited qualitative analysis was performed in this study. In addition, we applied the CitesSpace software to conduct this bibliometric study, but the CiteSpace software did not allow us to complicate information under both full counting and fractional counting systems. Thus, future scholars can analyze the development of music therapy in some specific journals using both quantitative and qualitative indicators.

Conclusions

This bibliometric study provides information regarding emerging trends in music therapy publications from 2000 to 2019. First, this study presents several theoretical implications related to publications that may assist future researchers to advance their research field. The results reveal that annual publications in music therapy research have significantly increased in the last two decades, and the overall trend in publications increased from 28 publications in 2000 to 111 publications in 2019. This analysis also furthers the comprehensive understanding of the global research structure in the field. Also, we have stated a high level of collaboration between different countries or regions and authors in the music therapy research. This collaboration has extremely expanded the knowledge of music therapy. Thus, future music therapy professionals can benefit from the most specialized research.

Second, this research represents several practical implications. IMT is the current research frontier in the field. IMT usually serves as an effective music therapy method for the health of people in clinical practice. Identifying the emerging trends in this field will help researchers prepare their studies on recent research issues ( Mulet-Forteza et al., 2021 ). Likewise, it also indicates future studies to address these issues and update the existing literature. In terms of the strongest citation bursts, the three keywords, “efficacy,” “health,” and “older adults,” highlight the fact that music therapy is an effective invention, and it can benefit the health of people. The development prospects of music therapy could be expected, and future scholars could pay attention to the clinical significance of music therapy to the health of people.

Finally, multiple researchers have indicated several health benefits of music therapy, and the music therapy mechanism perspective is necessary for future research to advance the field. Also, music therapy can benefit a wide range of individuals, such as those with autism spectrum, traumatic brain injury, or some physical disorders. Future researchers can develop music therapy standards to measure clinical practice.

Author Contributions

KL and LW: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, resources, writing—review, and editing. LW: software and data curation. KL: validation and writing—original draft preparation. XW: visualization, supervision, project administration, and funding acquisition. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This study was supported by the Fok Ying-Tong Education Foundation of China (161092), the scientific and technological research program of the Shanghai Science and Technology Committee (19080503100), and the Shanghai Key Lab of Human Performance (Shanghai University of Sport) (11DZ2261100).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

WoS, Web of Science; ESI, essential science indicators; IF, impact factor; IMT, improvisational music therapy; ASD, autism spectrum disorder.

Albornoz, Y. (2011). The effects of group improvisational music therapy on depression in adolescents and adults with substance abuse: a randomized controlled trial. Nord. J. Music Ther. 20, 208–224. doi: 10.1080/08098131.2010.522717

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Association, A. M. T. (2018). History of Music Therapy . Available online at: https://www.musictherapy.org/about/history/ (accessed November 10, 2020).

Google Scholar

Benoit, C. E., Dalla Bella, S., Farrugia, N., Obrig, H., Mainka, S., and Kotz, S. A. (2014). Musically cued gait-training improves both perceptual and motor timing in Parkinson's disease. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 8:494. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2014.00494

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Bernatzky, G., Bernatzky, P., Hesse, H. P., Staffen, W., and Ladurner, G. (2004). Stimulating music increases motor coordination in patients afflicted with Morbus Parkinson. Neurosci. Lett. 361, 4–8. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2003.12.022

Bronson, H., Vaudreuil, R., and Bradt, J. (2018). Music therapy treatment of active duty military: an overview of intensive outpatient and longitudinal care programs. Music Ther. Perspect. 36, 195–206. doi: 10.1093/mtp/miy006

Brotons, M., and Koger, S. M. (2000). The impact of music therapy on language functioning in dementia. J. Music Ther. 37, 183–195. doi: 10.1093/jmt/37.3.183

Bruscia, K. (1998). Defining Music Therapy 2nd Edition . Gilsum: Barcelona publications.

Castanha, R. C. G., and Grácio, M. C. C. (2014). Bibliometrics contribution to the metatheoretical and domain analysis studies. Knowl. Organiz. 41, 171–174. doi: 10.5771/0943-7444-2014-2-171

Chen, C. (2006). CiteSpace II: Detecting and visualizing emerging trends and transient patterns in scientific literature. J. Am. Soc. Inform. Sci. Technol. 57, 359–377. doi: 10.1002/asi.20317

Chen, C., Hu, Z., Liu, S., and Tseng, H. (2012). Emerging trends in regenerative medicine: a scientometric analysis in CiteSpace. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 12, 593–608. doi: 10.1517/14712598.2012.674507

Chen, H., Zhao, G., and Xu, N. (2012). “The analysis of research hotspots and fronts of knowledge visualization based on CiteSpace II,” in International Conference on Hybrid Learning , Vol. 7411, eds S. K. S. Cheung, J. Fong, L. F. Kwok, K. Li, and R. Kwan (Berlin; Heidelberg: Springer), 57–68. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-32018-_6

Deason, R., Simmons-Stern, N., Frustace, B., Ally, B., and Budson, A. (2012). Music as a memory enhancer: Differences between healthy older adults and patients with Alzheimer's disease. Psychomusicol. Music Mind Brain 22:175. doi: 10.1037/a0031118

Devlin, K., Alshaikh, J. T., and Pantelyat, A. (2019). Music therapy and music-based interventions for movement disorders. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 19:83. doi: 10.1007/s11910-019-1005-0

Durieux, V., and Gevenois, P. A. (2010). Bibliometric indicators: quality measurements of scientific publication. Radiology 255, 342–351. doi: 10.1148/radiol.09090626

Ellegaard, O., and Wallin, J. A. (2015). The bibliometric analysis of scholarly production: How great is the impact? Scientometrics 105, 1809–1831. doi: 10.1007/s11192-015-1645-z

Erkkilä, J., Punkanen, M., Fachner, J., Ala-Ruona, E., Pöntiö, I., Tervaniemi, M., et al. (2011). Individual music therapy for depression: randomised controlled trial. Br. J. Psychiatry 199, 132–139. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.085431

Falagas, M. E., Pitsouni, E. I., Malietzis, G. A., and Pappas, G. (2008). Comparison of PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar: strengths and weaknesses. Faseb J. 22, 338–342. doi: 10.1096/FJ.07-9492LSF

Fitzpatrick, R. B. (2005). Essential Science IndicatorsSM. Med. Ref. Serv. Q. 24, 67–78. doi: 10.1300/J115v24n04_05

Fukui, H., Arai, A., and Toyoshima, K. (2012). Efficacy of music therapy in treatment for the patients with Alzheimer's disease. Int. J. Alzheimer's Dis. 2012, 531646–531646. doi: 10.1155/2012/531646

Geretsegger, M., Holck, U., Carpente, J. A., Elefant, C., Kim, J., and Gold, C. (2015). Common characteristics of improvisational approaches in music therapy for children with autism spectrum disorder: developing treatment guidelines. J. Music Ther. 52, 258–281. doi: 10.1093/jmt/thv005

Geretsegger, M., Holck, U., and Gold, C. (2012). Randomised controlled trial of improvisational music therapy's effectiveness for children with autism spectrum disorders (TIME-A): study protocol. BMC Pediatr. 12:2. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-12-2

Geretsegger, M., Mossler, K. A., Bieleninik, L., Chen, X. J., Heldal, T. O., and Gold, C. (2017). Music therapy for people with schizophrenia and schizophrenia-like disorders. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 5:CD004025. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004025.pub4

Gold, C., Mössler, K., Grocke, D., Heldal, T. O., Tjemsland, L., Aarre, T., et al. (2013). Individual music therapy for mental health care clients with low therapy motivation: multicentre randomised controlled trial. Psychother. Psychosom. 82, 319–331. doi: 10.1159/000348452

Gold, C., Solli, H. P., Krüger, V., and Lie, S. A. (2009). Dose-response relationship in music therapy for people with serious mental disorders: systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 29, 193–207. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.01.001

Gonzalez-Serrano, M. H., Jones, P., and Llanos-Contrera, O. (2020). An overview of sport entrepreneurship field: a bibliometric analysis of the articles published in the Web of Science. Sport Soc. 23, 296–314. doi: 10.1080/17430437.2019.1607307

Gooding, L. F., and Langston, D. G. (2019). Music therapy with military populations: a scoping review. J. Music Ther. 56, 315–347. doi: 10.1093/jmt/thz010

Harzing, A.-W. (2013). Document categories in the ISI web of knowledge: misunderstanding the social sciences? Scientometrics 94, 23–34. doi: 10.1007/s11192-012-0738-1

Johnson, J. K., Chang, C. C., Brambati, S. M., Migliaccio, R., Gorno-Tempini, M. L., Miller, B. L., et al. (2011). Music recognition in frontotemporal lobar degeneration and Alzheimer disease. Cogn. Behav. Neurol. 24, 74–84. doi: 10.1097/WNN.0b013e31821de326

Li, H. C., Wang, H. H., Chou, F. H., and Chen, K. M. (2015). The effect of music therapy on cognitive functioning among older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 16, 71–77. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2014.10.004

Liang, Y. D., Li, Y., Zhao, J., Wang, X. Y., Zhu, H. Z., and Chen, X. H. (2017). Study of acupuncture for low back pain in recent 20 years: a bibliometric analysis via CiteSpace. J. Pain Res. 10, 951–964. doi: 10.2147/jpr.S132808

Mammarella, N., Fairfield, B., and Cornoldi, C. (2007). Does music enhance cognitive performance in healthy older adults? The Vivaldi effect. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 19, 394–399. doi: 10.1007/bf03324720

McDermott, O., Crellin, N., Ridder, H. M., and Orrell, M. (2013). Music therapy in dementia: a narrative synthesis systematic review. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 28, 781–794. doi: 10.1002/gps.3895

Merigó, J. M., Mulet-Forteza, C., Valencia, C., and Lew, A. A. (2019). Twenty years of tourism Geographies: a bibliometric overview. Tour. Geograph. 21, 881–910. doi: 10.1080/14616688.2019.1666913

Merton, R. K. (1965). On the Shoulders of Giants: A Shandean Postscript . New York, NY: Free Press.

Miao, Y., Xu, S. Y., Chen, L. S., Liang, G. Y., Pu, Y. P., and Yin, L. H. (2017). Trends of long noncoding RNA research from 2007 to 2016: a bibliometric analysis. Oncotarget 8, 83114–83127. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.20851

Mulet-Forteza, C., Lunn, E., Merigó, J. M., and Horrach, P. (2021). Research progress in tourism, leisure and hospitality in Europe (1969–2018). Int. J. Contemp. Hospit. Manage. 33, 48–74. doi: 10.1108/IJCHM-06-2020-0521

Pohl, P., Wressle, E., Lundin, F., Enthoven, P., and Dizdar, N. (2020). Group-based music intervention in Parkinson's disease - findings from a mixed-methods study. Clin. Rehabil. 34, 533–544. doi: 10.1177/0269215520907669

Porter, S., McConnell, T., McLaughlin, K., Lynn, F., Cardwell, C., Braiden, H. J., et al. (2017). Music therapy for children and adolescents with behavioural and emotional problems: a randomised controlled trial. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 58, 586–594. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12656

Pothoulaki, M., MacDonald, R., and Flowers, P. (2012). An interpretative phenomenological analysis of an improvisational music therapy program for cancer patients. J. Music Ther. 49, 45–67. doi: 10.1093/jmt/49.1.45

Sakamoto, M., Ando, H., and Tsutou, A. (2013). Comparing the effects of different individualized music interventions for elderly individuals with severe dementia. Int. Psychogeriatr. 25, 775–784. doi: 10.1017/s1041610212002256

Shimizu, N., Umemura, T., Matsunaga, M., and Hirai, T. (2018). Effects of movement music therapy with a percussion instrument on physical and frontal lobe function in older adults with mild cognitive impairment: a randomized controlled trial. Aging Ment. Health 22, 1614–1626. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2017.1379048

Small, H. (1973). Co-citation in the scientific literature: A new measure of the relationship between two documents. J. Am. Soc. Inform. Sci. 24, 265–269. doi: 10.1002/asi.4630240406

Ueda, T., Suzukamo, Y., Sato, M., and Izumi, S. (2013). Effects of music therapy on behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res. Rev. 12, 628–641. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2013.02.003

Wang, X. Q., Peng, M. S., Weng, L. M., Zheng, Y. L., Zhang, Z. J., and Chen, P. J. (2019). Bibliometric study of the comorbidity of pain and depression research. Neural. Plast 2019:1657498. doi: 10.1155/2019/1657498

Yeung, A. W. K. (2021). Is the influence of freud declining in psychology and psychiatry? A bibliometric analysis. Front. Psychol. 12:631516. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.631516

Zhao, K., Bai, Z. G., Bo, A., and Chi, I. (2016). A systematic review and meta-analysis of music therapy for the older adults with depression. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 31, 1188–1198. doi: 10.1002/gps.4494

Zheng, K., and Wang, X. (2019). Publications on the association between cognitive function and pain from 2000 to 2018: a bibliometric analysis using citespace. Med. Sci. Monit. 25, 8940–8951. doi: 10.12659/msm.917742

Keywords: music therapy, aged, bibliometrics, health, web of science

Citation: Li K, Weng L and Wang X (2021) The State of Music Therapy Studies in the Past 20 Years: A Bibliometric Analysis. Front. Psychol. 12:697726. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.697726

Received: 20 April 2021; Accepted: 12 May 2021; Published: 10 June 2021.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2021 Li, Weng and Wang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xueqiang Wang, wangxueqiang@sus.edu.cn

† These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Impact of Music on Mental Health

- December 2021

- MedS Alliance Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences 1(1):101-106

- 1(1):101-106

- CC BY-NC 4.0

- This person is not on ResearchGate, or hasn't claimed this research yet.

Discover the world's research

- 25+ million members

- 160+ million publication pages

- 2.3+ billion citations

- CURR PSYCHOL

- Health Psychol Rev

- Silva Pinho

- Geert-Jan Stams

- Cynthia Quiroga Murcia

- Recruit researchers

- Join for free

- Login Email Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google Welcome back! Please log in. Email · Hint Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google No account? Sign up

American Music Therapy Association

Please enter email. Please enter password.

- Music Therapy Journals & Publications

- Selected Bibliographies

- Researching Music Therapy

- Strategic Priority on Research

- Arthur Flagler Fultz Research Award from AMTA

Follow AMTA on Social Media

- What is Music Therapy?

- Who are Music Therapists?

- AMTA Board of Directors

- What is AMTA?

- Membership in AMTA

- Support Music Therapy

- A Career in Music Therapy

- Schools Offering Music Therapy

- Education and Clinical Training Information

- National Roster Internship Sites

- Find a Job in Music Therapy

- Advertise a Job in Music Therapy

- Scholarship Opportunities for AMTA Members

- Continuing Music Therapy Education

- Advocacy Basics

- Federal Advocacy - for members

- State Advocacy - for members

- AMTA Government Relations Team

- Coalitions & Partnerships - for members

- Advocacy Events - for members

- Find My Legislators

- AMTA Annual Conference

- Special Events & Media

- Sponsor AMTA Events

- Advertising in AMTA Publications

- Publish with AMTA

- Join AMTA/Renew Membership

- Donate to AMTA

- Visit the Bookstore

- Scholarships for AMTA Members

- Official Documents

- AMTA Officials

- News from AMTA Committees & Boards

- Member Toolkit

- Reimbursement Resources

- Online Publications & Podcasts

- AMTA Member Recognition Awards

Learning More About Music Therapy

Amta published journals.

The American Music Therapy Association produces two scholarly journals where research in music therapy is published and shared:

- The Journal of Music Therapy is published by AMTA as a forum for authoritative articles of current music therapy research and theory. Articles explore the use of music in the behavioral sciences and include book reviews and guest editorials. An index appears in issue 4 of each volume.

- Music Therapy Perspectives is designed to appeal to a wide readership, both inside and outside the profession of music therapy. Articles focus on music therapy practice, as well as academics and administration.

Subscriptions to these journals, downloadable articles, and a limited number of open access articles are available on each respective journal's webpage (click the links above for more information).

AMTA Publications Catalog

AMTA publishes a number of monographs, textbooks and other resources about the profession of music therapy. Please see our online bookstore for a complete listing of publications and products available. Use the menu items to navigate to Bookstore>Visit the Bookstore. Then you may choose to Shop for "Merchandise," Select Category, "Publications" and "Go" for a complete list of publications available. Or click this link for the complete list of AMTA Publications.

Numerous databases are available that index and list citations and abstracts to journal articles on music therapy. Some of these databases include links to full text copies (usually for a fee) or provide article retrieval services through your local library (fees vary). Public university open access libraries generally allow persons to enter the library and conduct database searches on their computer terminals on site.

National Library of Medicine: MEDLINE