Frontiers for Young Minds

- Download PDF

The Impacts of Junk Food on Health

Energy-dense, nutrient-poor foods, otherwise known as junk foods, have never been more accessible and available. Young people are bombarded with unhealthy junk-food choices daily, and this can lead to life-long dietary habits that are difficult to undo. In this article, we explore the scientific evidence behind both the short-term and long-term impacts of junk food consumption on our health.

Introduction

The world is currently facing an obesity epidemic, which puts people at risk for chronic diseases like heart disease and diabetes. Junk food can contribute to obesity and yet it is becoming a part of our everyday lives because of our fast-paced lifestyles. Life can be jam-packed when you are juggling school, sport, and hanging with friends and family! Junk food companies make food convenient, tasty, and affordable, so it has largely replaced preparing and eating healthy homemade meals. Junk foods include foods like burgers, fried chicken, and pizza from fast-food restaurants, as well as packaged foods like chips, biscuits, and ice-cream, sugar-sweetened beverages like soda, fatty meats like bacon, sugary cereals, and frozen ready meals like lasagne. These are typically highly processed foods , meaning several steps were involved in making the food, with a focus on making them tasty and thus easy to overeat. Unfortunately, junk foods provide lots of calories and energy, but little of the vital nutrients our bodies need to grow and be healthy, like proteins, vitamins, minerals, and fiber. Australian teenagers aged 14–18 years get more than 40% of their daily energy from these types of foods, which is concerning [ 1 ]. Junk foods are also known as discretionary foods , which means they are “not needed to meet nutrient requirements and do not belong to the five food groups” [ 2 ]. According to the dietary guidelines of Australian and many other countries, these five food groups are grains and cereals, vegetables and legumes, fruits, dairy and dairy alternatives, and meat and meat alternatives.

Young people are often the targets of sneaky advertising tactics by junk food companies, which show our heroes and icons promoting junk foods. In Australia, cricket, one of our favorite sports, is sponsored by a big fast-food brand. Elite athletes like cricket players are not fuelling their bodies with fried chicken, burgers, and fries! A study showed that adolescents aged 12–17 years view over 14.4 million food advertisements in a single year on popular websites, with cakes, cookies, and ice cream being the most frequently advertised products [ 3 ]. Another study examining YouTube videos popular amongst children reported that 38% of all ads involved a food or beverage and 56% of those food ads were for junk foods [ 4 ].

What Happens to Our Bodies Shortly After We Eat Junk Foods?

Food is made up of three major nutrients: carbohydrates, proteins, and fats. There are also vitamins and minerals in food that support good health, growth, and development. Getting the proper nutrition is very important during our teenage years. However, when we eat junk foods, we are consuming high amounts of carbohydrates, proteins, and fats, which are quickly absorbed by the body.

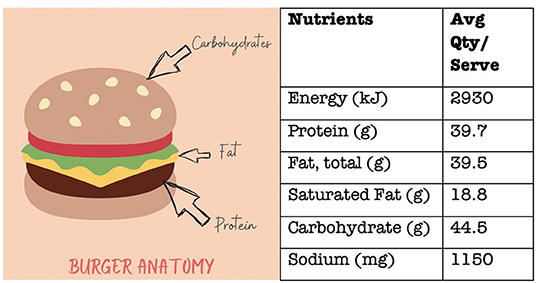

Let us take the example of eating a hamburger. A burger typically contains carbohydrates from the bun, proteins and fats from the beef patty, and fats from the cheese and sauce. On average, a burger from a fast-food chain contains 36–40% of your daily energy needs and this does not account for any chips or drinks consumed with it ( Figure 1 ). This is a large amount of food for the body to digest—not good if you are about to hit the cricket pitch!

- Figure 1 - The nutritional composition of a popular burger from a famous fast-food restaurant, detailing the average quantity per serving and per 100 g.

- The carbohydrates of a burger are mainly from the bun, while the protein comes from the beef patty. Large amounts of fat come from the cheese and sauce. Based on the Australian dietary guidelines, just one burger can be 36% of the recommended daily energy intake for teenage boys aged 12–15 years and 40% of the recommendations for teenage girls 12–15 years.

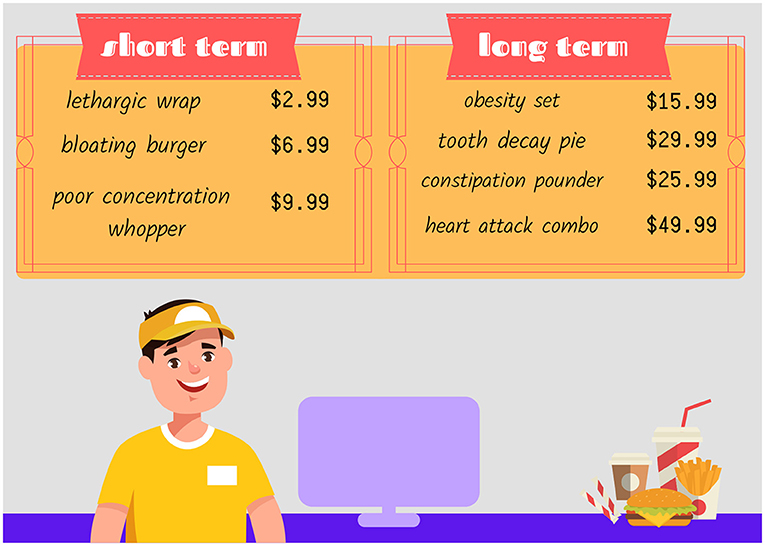

A few hours to a few days after eating rich, heavy foods such as a burger, unpleasant symptoms like tiredness, poor sleep, and even hunger can result ( Figure 2 ). Rather than providing an energy boost, junk foods can lead to a lack of energy. For a short time, sugar (a type of carbohydrate) makes people feel energized, happy, and upbeat as it is used by the body for energy. However, refined sugar , which is the type of sugar commonly found in junk foods, leads to a quick drop in blood sugar levels because it is digested quickly by the body. This can lead tiredness and cravings [ 5 ].

- Figure 2 - The short- and long-term impacts of junk food consumption.

- In the short-term, junk foods can make you feel tired, bloated, and unable to concentrate. Long-term, junk foods can lead to tooth decay and poor bowel habits. Junk foods can also lead to obesity and associated diseases such as heart disease. When junk foods are regularly consumed over long periods of time, the damages and complications to health are increasingly costly.

Fiber is a good carbohydrate commonly found in vegetables, fruits, barley, legumes, nuts, and seeds—foods from the five food groups. Fiber not only keeps the digestive system healthy, but also slows the stomach’s emptying process, keeping us feeling full for longer. Junk foods tend to lack fiber, so when we eat them, we notice decreasing energy and increasing hunger sooner.

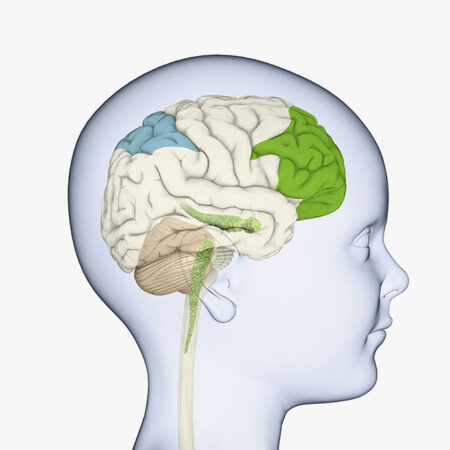

Foods such as walnuts, berries, tuna, and green veggies can boost concentration levels. This is particularly important for young minds who are doing lots of schoolwork. These foods are what most elite athletes are eating! On the other hand, eating junk foods can lead to poor concentration. Eating junk foods can lead to swelling in the part of the brain that has a major role in memory. A study performed in humans showed that eating an unhealthy breakfast high in fat and sugar for 4 days in a row caused disruptions to the learning and memory parts of the brain [ 6 ].

Long-Term Impacts of Junk Foods

If we eat mostly junk foods over many weeks, months, or years, there can be several long-term impacts on health ( Figure 2 ). For example, high saturated fat intake is strongly linked with high levels of bad cholesterol in the blood, which can be a sign of heart disease. Respected research studies found that young people who eat only small amounts of saturated fat have lower total cholesterol levels [ 7 ].

Frequent consumption of junk foods can also increase the risk of diseases such as hypertension and stroke. Hypertension is also known as high blood pressure and a stroke is damage to the brain from reduced blood supply, which prevents the brain from receiving the oxygen and nutrients it needs to survive. Hypertension and stroke can occur because of the high amounts of cholesterol and salt in junk foods.

Furthermore, junk foods can trigger the “happy hormone,” dopamine , to be released in the brain, making us feel good when we eat these foods. This can lead us to wanting more junk food to get that same happy feeling again [ 8 ]. Other long-term effects of eating too much junk food include tooth decay and constipation. Soft drinks, for instance, can cause tooth decay due to high amounts of sugar and acid that can wear down the protective tooth enamel. Junk foods are typically low in fiber too, which has negative consequences for gut health in the long term. Fiber forms the bulk of our poop and without it, it can be hard to poop!

Tips for Being Healthy

One way to figure out whether a food is a junk food is to think about how processed it is. When we think of foods in their whole and original forms, like a fresh tomato, a grain of rice, or milk squeezed from a cow, we can then start to imagine how many steps are involved to transform that whole food into something that is ready-to-eat, tasty, convenient, and has a long shelf life.

For teenagers 13–14 years old, the recommended daily energy intake is 8,200–9,900 kJ/day or 1,960 kcal-2,370 kcal/day for boys and 7,400–8,200 kJ/day or 1,770–1,960 kcal for girls, according to the Australian dietary guidelines. Of course, the more physically active you are, the higher your energy needs. Remember that junk foods are okay to eat occasionally, but they should not make up more than 10% of your daily energy intake. In a day, this may be a simple treat such as a small muffin or a few squares of chocolate. On a weekly basis, this might mean no more than two fast-food meals per week. The remaining 90% of food eaten should be from the five food groups.

In conclusion, we know that junk foods are tasty, affordable, and convenient. This makes it hard to limit the amount of junk food we eat. However, if junk foods become a staple of our diets, there can be negative impacts on our health. We should aim for high-fiber foods such as whole grains, vegetables, and fruits; meals that have moderate amounts of sugar and salt; and calcium-rich and iron-rich foods. Healthy foods help to build strong bodies and brains. Limiting junk food intake can happen on an individual level, based on our food choices, or through government policies and health-promotion strategies. We need governments to stop junk food companies from advertising to young people, and we need their help to replace junk food restaurants with more healthy options. Researchers can focus on education and health promotion around healthy food options and can work with young people to develop solutions. If we all work together, we can help young people across the world to make food choices that will improve their short and long-term health.

Obesity : ↑ A disorder where too much body fat increases the risk of health problems.

Processed Food : ↑ A raw agricultural food that has undergone processes to be washed, ground, cleaned and/or cooked further.

Discretionary Food : ↑ Foods and drinks not necessary to provide the nutrients the body needs but that may add variety to a person’s diet (according to the Australian dietary guidelines).

Refined Sugar : ↑ Sugar that has been processed from raw sources such as sugar cane, sugar beets or corn.

Saturated Fat : ↑ A type of fat commonly eaten from animal sources such as beef, chicken and pork, which typically promotes the production of “bad” cholesterol in the body.

Dopamine : ↑ A hormone that is released when the brain is expecting a reward and is associated with activities that generate pleasure, such as eating or shopping.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

[1] ↑ Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2013. 4324.0.55.002 - Microdata: Australian Health Survey: Nutrition and Physical Activity, 2011-12 . Australian Bureau of Statistics. Available online at: http://bit.ly/2jkRRZO (accessed December 13, 2019).

[2] ↑ National Health and Medical Research Council. 2013. Australian Dietary Guidelines Summary . Canberra, ACT: National Health and Medical Research Council.

[3] ↑ Potvin Kent, M., and Pauzé, E. 2018. The frequency and healthfulness of food and beverages advertised on adolescents’ preferred web sites in Canada. J. Adolesc. Health. 63:102–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.01.007

[4] ↑ Tan, L., Ng, S. H., Omar, A., and Karupaiah, T. 2018. What’s on YouTube? A case study on food and beverage advertising in videos targeted at children on social media. Child Obes. 14:280–90. doi: 10.1089/chi.2018.0037

[5] ↑ Gómez-Pinilla, F. 2008. Brain foods: the effects of nutrients on brain function. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 9, 568–78. doi: 10.1038/nrn2421

[6] ↑ Attuquayefio, T., Stevenson, R. J., Oaten, M. J., and Francis, H. M. 2017. A four-day western-style dietary intervention causes reductions in hippocampal-dependent learning and memory and interoceptive sensitivity. PLoS ONE . 12:e0172645. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0172645

[7] ↑ Te Morenga, L., and Montez, J. 2017. Health effects of saturated and trans-fatty acid intake in children and adolescents: systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 12:e0186672. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0186672

[8] ↑ Reichelt, A. C. 2016. Adolescent maturational transitions in the prefrontal cortex and dopamine signaling as a risk factor for the development of obesity and high fat/high sugar diet induced cognitive deficits. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 10. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2016.00189

- Systematic Review

- Open access

- Published: 12 June 2024

Association between junk food consumption and mental health problems in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis

- Hanieh-Sadat Ejtahed 1 , 2 ,

- Parham Mardi 3 ,

- Bahram Hejrani 4 ,

- Fatemeh Sadat Mahdavi 5 , 6 ,

- Behnaz Ghoreshi 7 ,

- Kimia Gohari 8 ,

- Motahar Heidari-Beni 9 &

- Mostafa Qorbani 7 , 10

BMC Psychiatry volume 24 , Article number: 438 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

937 Accesses

14 Altmetric

Metrics details

Anxiety and depression can seriously undermine mental health and quality of life globally. The consumption of junk foods, including ultra-processed foods, fast foods, unhealthy snacks, and sugar-sweetened beverages, has been linked to mental health. The aim of this study is to use the published literature to evaluate how junk food consumption may be associated with mental health disorders in adults.

A systematic search was conducted up to July 2023 across international databases including PubMed/Medline, ISI Web of Science, Scopus, Cochrane, Google Scholar, and EMBASE. Data extraction and quality assessment were performed by two independent reviewers. Heterogeneity across studies was assessed using the I 2 statistic and chi-square-based Q-test. A random/fixed effect meta-analysis was conducted to pool odds ratios (ORs) and hazard ratios (HRs).

Of the 1745 retrieved articles, 17 studies with 159,885 participants were suitable for inclusion in the systematic review and meta-analysis (seven longitudinal, nine cross-sectional and one case-control studies). Quantitative synthesis based on cross-sectional studies showed that junk food consumption increases the odds of having stress and depression (OR = 1.15, 95% CI: 1.06 to 1.23). Moreover, pooling results of cohort studies showed that junk food consumption is associated with a 16% increment in the odds of developing mental health problems (OR = 1.16, 95% CI: 1.07 to 1.24).

Meta-analysis revealed that consumption of junk foods was associated with an increased hazard of developing depression. Increased consumption of junk food has heightened the odds of depression and psychological stress being experienced in adult populations.

Peer Review reports

Psychological conditions such as bipolar affective disorder, eating disorders, anxiety disorders, and depressive disorders impose a considerable burden across the international community, adversely affecting quality of life [ 1 , 2 ]. Psychological problems including depression, stress, and anxiety, also arise in association with some non-communicable diseases including cardiovascular disease (CVD), stroke, and cancer [ 3 ]. All of these mental health problems have adverse effects on health status, quality of life, and ability to work [ 4 ].

Genetics, socioeconomic status, exercise habits, diet, and nutritional status, are understood to be key contributors to the development of emotional or behavioral problems [ 5 ]. Food-mood relationships underpin well-known pathways, suggesting that unhealthy eating habits and poor nutritional status are correlated with various mental health problems and behavioral disturbances in adults [ 6 ]. This infers that mood and psychological health may be influenced by nutritional habits [ 7 ].

The world-wide consumption of junk foods, which include ultra-processed foods, fast foods, unhealthy snacks, and sugar-sweetened beverages, is increasing. The hallmarks of junk foods are that they have high levels of energy, fat, sugar, and salt, accompanied by low levels of micronutrients, fiber, and other bioactive compounds [ 8 ]. The low nutritional value of junk foods can alter inflammatory pathways, leading to an increase in biomarkers for oxidative stress and inflammation, which contribute to biological changes associated with mental health disorders. In vitro studies have demonstrated that junk food consumption can negatively affect the brain and mental health [ 9 , 10 ].

However, the findings of epidemiological studies are inconsistent. Some studies showed the significant association between junk foods consumption and mental health disorders. However, other studies did not mention any relationship [ 4 , 11 , 12 ]. The aim of this study is to examine the relationship between junk food consumption and mental health disorders in adults by conducting a systematic review and meta-analysis of published studies to date.

The current systematic review and meta-analysis study was conducted according to the PRISMA 2020 statement (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) [ 13 , 14 ], included studies assessing the relationship between junk food consumption and mental health in adults.

Search strategy

A systematic literature search was conducted in PubMed/Medline, ISI Web of Science, Scopus, Cochrane, Google Scholar, and EMBASE up to July 2023. The following keywords were used in this search: “sweetened drink*” OR “sweetened beverage*” OR snack* OR “processed food*” OR “junk food*” OR “soft drinks” OR “sugared beverages” OR “fried foods” OR “instant foods” OR sweets for junk food consumption and “mental health” OR depression OR stress OR anxiety OR “sleep dissatisfaction” OR “sleep disorders” OR happiness OR wellbeing for mental health status. In PubMed, keywords were searched through [tiab] and [MeSH] tags. Articles were required to be written in English language; there was no limitation regarding the year of publication. The reference lists of included papers were also examined to avoid missing other published data.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Two investigators independently screened the articles retrieved during the literature search. Publications that fulfilled the following criteria were eligible for inclusion: (1) observational studies that were conducted in adults (cohort, case-control, cross-sectional); and (2) studies that examined the relationship between junk food consumption and mental health status. We excluded letters, comments, reviews, meta-analyses, ecological, in vitro, and pre-clinical studies, as well as duplicate studies.

Data extraction

For each eligible study, the following information was extracted: first author, year of publication, study design, country, age range, gender, sample size, type of junk food, dietary assessment tool, mental health parameters, mental health assessment tool, study quality score, effect sizes and measures, and covariates.

It should be noted that in the present study, junk food intake was considered using four categories: (i) sweet drinks (fruit-flavored drinks, sweetened coffee, fruit juice drinks, sugared coffee and tea, energy drinks, cola drinks, beverages, soft drinks, lemonade, and soda), (ii) sweet snacks (total sugars, added sugars, sweetened desserts, fatty/sweet products, ice cream, chocolate, artificial sweeteners, sweet snacks, dessert, sauces and dressings, candy, patterns of consumption of sweet, high fat and sugary foods, biscuits and pastries, cakes, pie/cookies, and baked goods), (iii) snacks (including snacks, sauces/added fats, fast food, fast-food pattern, western diet pattern, snacking and convenience pattern, fried foods, fried potato, crisps, salty snacks, convenience pattern, instant foods), and (iv) total junk foods (all types of junk foods).

Quality assessment of studies

The quality of the included studies was examined using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) [ 15 , 16 ]. The NOS assigns a maximum of 9 points to each study: 4 for selection, 2 for comparability, and 3 for assessment of outcomes (for cohort study) or exposures (for case-control study).

The maximum score for cohort and case-control studies were 9 and for cross-sectional studies were 7. In the current analysis, the quality of studies is defined good if the studies get 3 or 4 stars in the selection domain AND 1 or 2 stars in the comparability domain AND 2 or 3 stars in the outcome/exposure domain. Besides, fair quality is defined as 2 stars in the selection domain AND 1 or 2 stars in the comparability domain AND 2 or 3 stars in the outcome/exposure domain and finally, poor quality is defined for 0 or 1 star in the selection domain OR 0 star in the comparability domain OR 0 or 1 star in the outcome/exposure domain.

All steps including searching, article screening, data extraction, and quality assessment of articles were independently performed by two investigators. Disagreements between the two investigators were resolved by discussion to reach consensus.

Statistical analysis

The results of the current quantitative synthesis are presented as hazard ratios (HRs) or odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). STATA version 14.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX) software was used to perform the meta-analysis. We conducted meta-analysis whenever at least two studies investigated similar associations between junk food consumption and mental health problems.

I 2 statistic and chi-square-based Q-test were used for the assessment of heterogeneity. In the current study, a lack of heterogeneity was inferred when the p-value of chi-square-based Q-test exceeded 0.10. Fixed models were used to pool HRs and ORs when the heterogeneity p-value was higher than 0.10. Random models were used to pool the ORs whenever the heterogeneity p-value was equal to or less than 0.10, followed by Galbraith analysis and sensitivity analysis. Subgroup analysis was also conducted to identify the source of heterogeneity. Publication bias was measured using Begg’s test or Egger’s test and considered substantial whenever the resulting p-value was < 0.1.

Systematic search results

The flow diagram for the process of study selection is shown in the PRISMA flowchart (Fig. 1 ). Based on the initial search, we found 1745 papers. After removal of duplicate documents and title and abstract screening, 69 articles remained for more detailed assessment. Full texts of these papers were reviewed carefully by three researchers, with 17 articles satisfying the eligibility requirements for inclusion in the systematic review and meta-analysis.

The PRISMA flowchart for the process of study selection

Characteristics of the included studies

Seventeen studies evaluating a total of 159,885 participants were included in our quantitative synthesis. A considerable number of participants were female, with seven articles restricted to female participants. Most of the included studies were cross-sectional (58.82%), with the remaining seven (47.05%) being cohort studies. It should be noted that Reinks et al. (2013) presented both cross-sectional and longitudinal data. Reinks et al. (2013) and ten other papers (64.70% in total) assessed depression as an outcome. Nine (52.94%) of studies assessed anxiety or stress as outcomes. In terms of dietary exposures, various types of junk foods such as ultra-processed food, beverages, and snacks were evaluated across the 17 studies. Table 1 illustrates detailed characteristics of records including the age of participants and provenance of studies. All of the included studies have good quality.

Qualitative synthesis

Most of the included studies concordantly showed at least a single significant link between junk food consumption and psychological outcomes. This was despite their use of different measures of association, dissimilar exposure duration and outcomes, and heterogenous definitions, all of which made it challenging to draw conclusions from the qualitative synthesis (summarized in Table 2 ). Nevertheless, findings from some studies were discordant. For instance, while Sangsefidi et al. (2020) and Chaplin et al. (2011) demonstrated a significant association between stress and snack intake, Almajwal et al. (2016) and Zenk et al. (2014) reported non-significant findings, despite the use of similar measures of association and comparable adjustments for covariates. Although a notable number of studies showed a significant link between junk food intake and psychological disorders, the level of disagreement across studies meant that a meta-analysis was essential in order to clarify this relationship.

Quantitative synthesis

Pooling or in cross-sectional studies.

Four cross-sectional studies ( n = 13,500) demonstrated that junk food consumption was associated with increased stress (pooled OR = 1.33, 95% CI: 1.02 to 1.65). This finding shows a significant association; however, a notable level of heterogeneity was observed (I² = 74.3%, p = 0.009) (Fig. 2 ; Table 3 ). Also, six cross-sectional studies, including 74,127 participants, illustrated a significant association between junk food consumption and depression, with a pooled OR of 1.16 (95% CI: 1.04 to 1.28) (Fig. 2 ). Overall, junk food consumption indicated a significant association with increased odds of mental health problems (OR = 1.15, 95% CI: 1.06 to 1.23). The Egger’s test for small-study effects indicated evidence of publication bias ( p > 0.001). To address this bias, a trim and fill analysis was conducted, resulting in an adjusted OR of 1.11 (95% CI: 0.95 to 1.30). Funnel plot is presented in Fig. 3 .

Junk food consumption (unhealthy snacks and sweetened beverages) and odds of having depression and stress in cross-sectional studies

Funnel plot, using data from cross-sectional studies investigating the association between junk food consumption and mental health problems

Pooling PR in cross-sectional studies

Two cross-sectional studies focusing on stress with a combined sample size of 2,232 participants reported a PR of 1.31 (95% CI: 1.07–1.55) (Fig. 4 ).

Association between junk foods consumption and having stress in cross-sectional studies

Pooling OR in cohort studies

Pooling results of cohort studies showed that junk food consumption significantly increases the odds of depression by 15% (OR = 1.15; 95% CI: 1.06 to 1.24). After inclusion of the single cohort study that considered stress as its outcome, the overall OR of junk foods consumption and mental disorders was 1.16 (OR = 1.16, 95% CI: 1.07 to 1.24) (Fig. 5 ).

Association between junk foods consumption and having mental health problems in cohort studies

Although Egger’s test for small-study effects yielded a bias coefficient of 2.53, standard error of 1.19, and a p-value of 0.07, trim and fill analysis did not impute any studies, and the overall OR remained unchanged. Figure 6 demonstrates the funnel plot.

Funnel plot, using data from cohort studies investigating the association between junk food consumption and mental health problems

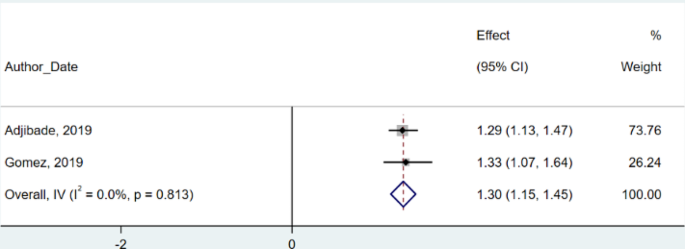

Pooling HR in cohort studies

Aggregating two cohort studies with 41,637 participants showed an HR of 1.30 (95% CI: 1.15 to 1.45) for depression, demonstrating a significant risk increase (Fig. 7 ). Remarkably, these studies showed no heterogeneity (I² = 0.0%, p = 0.81) or publication bias.

Junk food consumption and risk of depression in cohort studies

The meta-analysis reported in the present study showed that high consumption of junk foods was significantly associated with increased risks of depression. In addition, higher junk food consumption was associated with increased odds of depression and psychological stress. This association between consumption of food with low nutritional value and mental health was demonstrated in multiple studies on different populations and cultures [ 17 , 18 , 19 ].

Meta-analysis of prospective studies showed that increased risk of subsequent depression and adverse mental health outcomes were correlated with higher ultra-processed food intake [ 20 ]. According to meta analysis incorporating seven studies, junk food consumption increased the risk of experiencing mental illness symptoms [ 21 ]. For example, one study reporting outcomes for 1591 adults, demonstrated that high consumption of fast foods and processed foods was associated with anxiety, nervousness, restlessness, lack of motivation and depressive symptoms [ 22 ]. In another study, weight gain due to unhealthy eating was associated with deterioration in mental health in 404 adults during the second year of the COVID-19 pandemic [ 23 ]. Our findings are consistent with a recent systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis that included 26 studies and 260,385 participants from twelve countries, which showed that ultra-processed food consumption increased risk of depression [ 24 ].

Epidemiological data suggests that unhealthy food consumption may be associated with poorer mental health through its adverse effects on inflammatory processes, nutritional status, and neurotransmitter function. Inflammation has previously been associated with underlying biological bases for depression [ 25 ]. Several observational and meta-analysis studies have demonstrated an inverse association between the consumption of healthy foods including vegetables, fruits, whole-grain and fish, with depressive symptoms [ 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 ]. Healthy dietary patterns include a significant amount of tryptophan, an essential amino acid and precursor to serotonin; evidence shows that reduction in the availability of serotonin is associated with depression [ 30 , 31 ].

The adoption of western dietary patterns that regularly include junk foods and fast foods can increase the probability of developing inflammatory and cardiovascular diseases. Inflammatory conditions are related to mental health disorders including depression, stress and anxiety [ 32 , 33 ]. In addition, life stressors may augment the interconnection between depressive mood and unhealthy dietary patterns through activation of the brain’s reward system by foods that are high in sugar, fat, and salt [ 34 ].

There is also evidence that brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) may be reduced by consumption of a high fat diet. BDNF is associated with supporting existing neurons and the production of new neurons and implicated in the pathogenesis of depressive disorder. A reduction in BDNF impairs synaptic and cognitive function and neuronal growth, contributing to the development of psychological disorders [ 35 ]. Western-type diets include a higher amount of polyunsaturated omega-6 fatty acids, which increase proinflammatory eicosanoids, and decrease BDNF and neuronal membrane fluidity [ 36 ]. This suggests that the adverse effects of junk and fast foods on mental health might be associated with the high content of unhealthy fats contained in these foods [ 4 ]. Moreover, intake of high amounts of sugar through consumption of sweet drinks and snacks can lead to endothelial dysfunction, inflammation, and exaggerated insulin production that may also influence mood [ 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 ].

Mood disorder may itself influence diet, with some studies reporting that patients with depression consume a large amount of carbohydrate-fat-rich foods during their depressive episodes [ 41 , 42 , 43 ]. Serotonin, an important neurotransmitter for regulating mood, may play a prominent role in this respect given that the sole source of its precursor, tryptophan, is through the diet [ 44 ].

The consumption of ultra-processed foods is positively correlated with unhealthy eating habits, including lower intake of fruits and vegetables and higher intake of sweet foods or beverages [ 8 , 45 ]. It is notable that ultra-processed foods contain additives as well as molecules that are generated by high-temperature heating. These can alter gut microbiota composition and reduce nutrient absorption [ 46 ]. Some studies have explored the association between the gut microbiome and mental health [ 47 , 48 , 49 ], with animal studies suggesting that food additives might increase symptoms of and susceptibility to anxiety and depression via changes of gut microbiota composition [ 50 , 51 ].

The present paper found that the outcomes of studies selected for the meta-analysis were not always in agreement. This may have been due to confounding factors such as past history of depression or negative life events not being included in the analysis, differences in study designs, sample sizes or population characteristics, non-homogeneous assessment of dietary patterns, and inconsistencies in the evaluation of psychological disorders including the use of different diagnostic criteria to define mental health status.

On the other side, some studies have reported that mental health disorders including depression and psychological stress may reduce an individual’s motivation to eat healthy foods and sometime lead to overeating [ 17 ], skipping main meals and replacing them with high calories foods [ 30 ]. Some individuals consume high energy and fatty foods during stressful situations, choosing these more palatable foods as an unconscious or deliberate strategy to change their energy levels and mood [ 52 , 53 ]. Stress affects neuroendocrine function by activating the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, increasing the secretion of glucocorticoids. These change glucose metabolism, promote insulin resistance, and alter the secretion of appetite-related hormones. All of these factors contribute to the propensity to eat more high-calorie palatable food [ 12 ]. However, there are also studies that report no differences in eating patterns under stressful and non-stressful conditions [ 54 , 55 ]. The analysis presented in the present study cannot be used to demonstrate causality. On the basis of the evidence, it is plausible that there is a bidirectional relationship between junk food consumption and mental health [ 17 ]. It remains unclear whether the quality of food choices affects susceptibility to poorer mental health outcomes, and/or the experience of unpleasant emotions influences the quality of food selection [ 30 ]. Evidence for a causal pathway is unclear and needs to be further investigated in well-controlled longitudinal studies. Our meta-analysis on cross-sectional studies showed an association between junk food consumption and increased odds of having stress and depression. Besides, meta-analysis on cohort studies demonstrated that junk foods consumption increases the risk of developing stress and depression.

Strengths and limitations

As the main strength of our study, we have comprehensively and specifically evaluated earlier findings regarding the association between junk food consumption and mental health status in adults. The present study has some limitations arising from the studies selected for meta-analysis. Inconsistencies in design of studies such as the ways that diet is assessed using different dietary questionnaire tools, the influence of seasonal and hormonal variations of depressive symptoms, and the use of different diagnostic criteria for defining mental health status is one of the limitations of this study. Despite the association shown between consumption of junk foods and mental health disorders, the strength of the associations and number of documents included in this study is unable to demonstrate causality.

The present study supports the conclusion that consumption of junk foods that are high in fat and sugar content and of low nutritive value are associated with poorer mental health in adults. Further studies utilizing a longitudinal design are needed to better determine the directionality and effect size of junk food consumption on psychological disorders. Moreover, more studies are warranted to assess the mechanisms involved in this relationship to provide scientific support for changes in public health policies.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request from the authors.

Connell J, Brazier J, O’Cathain A, Lloyd-Jones M, Paisley S. Quality of life of people with mental health problems: a synthesis of qualitative research. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2012;10:138.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Arias D, Saxena S, Verguet S. Quantifying the global burden of mental disorders and their economic value. EClinicalMedicine. 2022;54:101675.

Khaustova OO, Markova MV, Driuchenko MO, Burdeinyi AO. Proactive psychological and psychiatric support of patients with chronic non-communicable diseases in a randomised trial: a Ukrainian experience. Gen Psychiatr. 2022;35(5):e100881.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Sangsefidi ZS, Lorzadeh E, Hosseinzadeh M, Mirzaei M. Dietary habits and psychological disorders in a large sample of Iranian adults: a population-based study. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2020;19:8.

Gu Y, Zhu Y, Xu G. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers in the Fangcang shelter hospital in China. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2022;68(1):64–72.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

El Ansari W, Adetunji H, Oskrochi R. Food and mental health: relationship between food and perceived stress and depressive symptoms among university students in the United Kingdom. Cent Eur J Public Health. 2014;22(2):90–7.

Tuck NJ, Farrow C, Thomas JM. Assessing the effects of vegetable consumption on the psychological health of healthy adults: a systematic review of prospective research. Am J Clin Nutr. 2019;110(1):196–211.

Adjibade M, Julia C, Allès B, Touvier M, Lemogne C, Srour B, et al. Prospective association between ultra-processed food consumption and incident depressive symptoms in the French NutriNet-Santé cohort. BMC Med. 2019;17(1):78.

Hahad O, Prochaska JH, Daiber A, Muenzel T. Environmental noise-Induced effects on stress hormones, oxidative stress, and vascular dysfunction: key factors in the relationship between Cerebrocardiovascular and Psychological disorders. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2019;2019:4623109.

Adnan M, Chy MNU, Kamal A, Chowdhury KAA, Rahman MA, Reza A et al. Intervention in Neuropsychiatric disorders by suppressing inflammatory and Oxidative Stress Signal and Exploration of in Silico studies for potential lead compounds from Holigarna Caustica (Dennst.) Oken leaves. Biomolecules. 2020;10(4).

Xia Y, Wang N, Yu B, Zhang Q, Liu L, Meng G, et al. Dietary patterns are associated with depressive symptoms among Chinese adults: a case-control study with propensity score matching. Eur J Nutr. 2017;56(8):2577–87.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Canuto R, Garcez A, Spritzer PM, Olinto MTA. Associations of perceived stress and salivary cortisol with the snack and fast-food dietary pattern in women shift workers. Stress. 2021;24(6):763–71.

Hasani H, Mardi S, Shakerian S, Taherzadeh-Ghahfarokhi N, Mardi P. The novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19): a PRISMA systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical and paraclinical characteristics. Biomed Res Int. 2020;2020:1–16.

Article Google Scholar

Rethlefsen ML, Kirtley S, Waffenschmidt S, Ayala AP, Moher D, Page MJ, et al. PRISMA-S: an extension to the PRISMA statement for reporting literature searches in systematic reviews. Syst Reviews. 2021;10(1):1–19.

Wells G, Shea B, O’Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, et al. Newcastle-Ottawa quality assessment scale cohort studies. University of Ottawa; 2014.

Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25:603–5.

Crawford GB, Khedkar A, Flaws JA, Sorkin JD, Gallicchio L. Depressive symptoms and self-reported fast-food intake in midlife women. Prev Med. 2011;52(3–4):254–7.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Rossa-Roccor V, Richardson CG, Murphy RA, Gadermann AM. The association between diet and mental health and wellbeing in young adults within a biopsychosocial framework. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(6):e0252358.

van der Velde LA, Zitman FM, Mackenbach JD, Numans ME, Kiefte-de Jong JC. The interplay between fast-food outlet exposure, household food insecurity and diet quality in disadvantaged districts. Public Health Nutr. 2022;25(1):105–13.

Lane MM, Gamage E, Travica N, Dissanayaka T, Ashtree DN, Gauci S, et al. Ultra-processed food consumption and mental health: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Nutrients. 2022;14(13):2568.

Hafizurrachman M, Hartono RK. Junk food consumption and symptoms of mental health problems: a meta-analysis for public health awareness. Kesmas: Jurnal Kesehatan Masyarakat Nasional. (Natl Public Health Journal). 2021;16(1).

Rosenberg L, Welch M, Dempsey G, Colabelli M, Kumarasivam T, Moser L et al. Fast foods, and Processed Foods May worsen perceived stress and Mental Health. FASEB J. 2022;36.

Almandoz JP, Xie L, Schellinger JN, Mathew MS, Marroquin EM, Murvelashvili N, et al. Changes in body weight, health behaviors, and mental health in adults with obesity during the COVID-19 pandemic. Obesity. 2022;30(9):1875–86.

Mazloomi SN, Talebi S, Mehrabani S, Bagheri R, Ghavami A, Zarpoosh M et al. The association of ultra-processed food consumption with adult mental health disorders: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of 260,385 participants. Nutr Neurosci. 2022:1–19.

Coletro HN, Mendonça RD, Meireles AL, Machado-Coelho GLL, Menezes MC. Ultra-processed and fresh food consumption and symptoms of anxiety and depression during the COVID – 19 pandemic: COVID inconfidentes. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 2022;47:206–14.

Li Y, Lv MR, Wei YJ, Sun L, Zhang JX, Zhang HG, et al. Dietary patterns and depression risk: a meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2017;253:373–82.

Hodge A, Almeida OP, English DR, Giles GG, Flicker L. Patterns of dietary intake and psychological distress in older australians: benefits not just from a Mediterranean diet. Int Psychogeriatr. 2013;25(3):456–66.

Mihrshahi S, Dobson AJ, Mishra GD. Fruit and vegetable consumption and prevalence and incidence of depressive symptoms in mid-age women: results from the Australian longitudinal study on women’s health. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2015;69(5):585–91.

Nguyen B, Ding D, Mihrshahi S. Fruit and vegetable consumption and psychological distress: cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses based on a large Australian sample. BMJ Open. 2017;7(3):e014201.

Liu C, Xie B, Chou CP, Koprowski C, Zhou D, Palmer P, et al. Perceived stress, depression and food consumption frequency in the college students of China Seven cities. Physiol Behav. 2007;92(4):748–54.

Rienks J, Dobson AJ, Mishra GD. Mediterranean dietary pattern and prevalence and incidence of depressive symptoms in mid-aged women: results from a large community-based prospective study. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2013;67(1):75–82.

Khosravi M, Sotoudeh G, Majdzadeh R, Nejati S, Darabi S, Raisi F, et al. Healthy and unhealthy dietary patterns are related to Depression: a case-control study. Psychiatry Investig. 2015;12(4):434–42.

Khosravi M, Sotoudeh G, Amini M, Raisi F, Mansoori A, Hosseinzadeh M. The relationship between dietary patterns and depression mediated by serum levels of folate and vitamin B12. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20(1):63.

Le Port A, Gueguen A, Kesse-Guyot E, Melchior M, Lemogne C, Nabi H, et al. Association between dietary patterns and depressive symptoms over time: a 10-year follow-up study of the GAZEL cohort. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(12):e51593.

Miao Z, Wang Y, Sun Z. The relationships between stress, Mental disorders, and epigenetic regulation of BDNF. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(4).

Shakya PR, Melaku YA, Page A, Gill TK. Association between dietary patterns and adult depression symptoms based on principal component analysis, reduced-rank regression and partial least-squares. Clin Nutr. 2020;39(9):2811–23.

Bishwajit G, O’Leary DP, Ghosh S, Sanni Y, Shangfeng T, Zhanchun F. Association between depression and fruit and vegetable consumption among adults in South Asia. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17(1):15.

Kingsbury M, Dupuis G, Jacka F, Roy-Gagnon MH, McMartin SE, Colman I. Associations between fruit and vegetable consumption and depressive symptoms: evidence from a national Canadian longitudinal survey. J Epidemiol Commun Health. 2016;70(2):155–61.

Hamer M, Chida Y. Associations of very high C-reactive protein concentration with psychosocial and cardiovascular risk factors in an ageing population. Atherosclerosis. 2009;206(2):599–603.

Sousa KT, Marques ES, Levy RB, Azeredo CM. Food consumption and depression among Brazilian adults: results from the Brazilian National Health Survey, 2013. Cadernos De Saude Publica. 2019;36(1):e00245818.

Daneshzad E, Keshavarz SA, Qorbani M, Larijani B, Azadbakht L. Association between a low-carbohydrate diet and sleep status, depression, anxiety, and stress score. J Sci Food Agric. 2020;100(7):2946–52.

Włodarczyk A, Cubała WJ, Stawicki M. Ketogenic diet for depression: A potential dietary regimen to maintain euthymia? Progress in neuro-psychopharmacology & biological psychiatry. 2021;109:110257.

Sangsefidi ZS, Salehi-Abarghouei A, Sangsefidi ZS, Mirzaei M, Hosseinzadeh M. The relation between low carbohydrate diet score and psychological disorders among Iranian adults. Nutr Metabolism. 2021;18(1):16.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Moncrieff J, Cooper RE, Stockmann T, Amendola S, Hengartner MP, Horowitz MA. The serotonin theory of depression: a systematic umbrella review of the evidence. Mol Psychiatry. 2022.

Lee J, Allen J. Gender Differences in Healthy and Unhealthy Food Consumption and its relationship with Depression in Young Adulthood. Commun Ment Health J. 2021;57(5):898–909.

Roca-Saavedra P, Mendez-Vilabrille V, Miranda JM, Nebot C, Cardelle-Cobas A, Franco CM, et al. Food additives, contaminants and other minor components: effects on human gut microbiota-a review. J Physiol Biochem. 2018;74(1):69–83.

Simkin DR. Microbiome and Mental Health, specifically as it relates to adolescents. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2019;21(9):93.

Järbrink-Sehgal E, Andreasson A. The gut microbiota and mental health in adults. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2020;62:102–14.

Dickerson F, Dilmore AH, Godoy-Vitorino F, Nguyen TT, Paulus M, Pinto-Tomas AA et al. The Microbiome and Mental Health Across the Lifespan. Current topics in behavioral neurosciences. 2022.

Quines CB, Rosa SG, Da Rocha JT, Gai BM, Bortolatto CF, Duarte MM, et al. Monosodium glutamate, a food additive, induces depressive-like and anxiogenic-like behaviors in young rats. Life Sci. 2014;107(1–2):27–31.

Campos-Sepúlveda AE, Martínez Enríquez ME, Rodríguez Arellanes R, Peláez LE, Rodríguez Amézquita AL, Cadena Razo A. Neonatal monosodium glutamate administration increases aminooxyacetic acid (AOA) susceptibility effects in adult mice. Proceedings of the Western Pharmacology Society. 2009;52:72 – 4.

Choi J. Impact of stress levels on eating behaviors among College Students. Nutrients. 2020;12(5).

Radavelli-Bagatini S, Sim M, Blekkenhorst LC, Bondonno NP, Bondonno CP, Woodman R, et al. Associations of specific types of fruit and vegetables with perceived stress in adults: the AusDiab study. Eur J Nutr. 2022;61(6):2929–38.

Bellisle F, Louis-Sylvestre J, Linet N, Rocaboy B, Dalle B, Cheneau F, et al. Anxiety and food intake in men. Psychosom Med. 1990;52(4):452–7.

Pollard TM, Steptoe A, Canaan L, Davies GJ, Wardle J. Effects of academic examination stress on eating behavior and blood lipid levels. Int J Behav Med. 1995;2(4):299–320.

Download references

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Jillian Broadbear for their invaluable contribution in editing and reviewing this manuscript.

The authors gratefully acknowledge funding provided by the Alborz University of Medical Sciences.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Obesity and Eating Habits Research Center, Endocrinology and Metabolism Clinical Sciences Institute, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Hanieh-Sadat Ejtahed

Endocrinology and Metabolism Research Center, Endocrinology and Metabolism Clinical Sciences Institute, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Social Determinants of Health Research Center, Alborz University of Medical Sciences, Karaj, Iran

Parham Mardi

School of Medicine, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Bahram Hejrani

Student Research Committee, Alborz University of Medical Sciences, Karaj, Iran

Fatemeh Sadat Mahdavi

Clinical Research Development Unit, Shahid Rajaei Educational & Medical Center, Alborz University of Medical Sciences, Karaj, Iran

Non-communicable Diseases Research Center, Alborz University of Medical Sciences, Karaj, Iran

Behnaz Ghoreshi & Mostafa Qorbani

Department of Biostatistics, Faculty of Medicine Sciences, Tarbiat Modares University, Tehran, Iran

Kimia Gohari

Department of Nutrition, Child Growth and Development Research Center, Research Institute for Primordial Prevention of Non-Communicable Disease, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran

Motahar Heidari-Beni

Chronic Diseases Research Center, Endocrinology and Metabolism Population Sciences Institute, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Mostafa Qorbani

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

H.E: conception and design of the study, acquisition and analysis of data, drafting the manuscript, P.M: quality assessment and drafting the manuscript, B.H: screening and data extraction, FS.M: data extraction and drafting the manuscript, BG: data extraction and quality assessment, K.G: data extraction and analysis of data, M.HB: conception and design of the study, drafting the manuscript, M.Q: conception and design of the study, analysis of data and drafting the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Correspondence to Motahar Heidari-Beni or Mostafa Qorbani .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Ejtahed, HS., Mardi, P., Hejrani, B. et al. Association between junk food consumption and mental health problems in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry 24 , 438 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-024-05889-8

Download citation

Received : 12 December 2023

Accepted : 04 June 2024

Published : 12 June 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-024-05889-8

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Mental health

BMC Psychiatry

ISSN: 1471-244X

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

New review unpacks what we know about junk food and 32 health issues

We have long been told that junk food is bad for us.

But a new review by experts at leading Australian and international institutions sheds light on just how damaging a diet of instant noodles, chips, fast food and ready-made meals can be.

The researchers delved into the results of 45 previous studies, published over the past three years, involving almost 10 million participants.

Considered the largest review of its kind, researchers found "strong evidence" that eating ultra-processed foods can put you at higher risk of 32 different health problems, both physical and mental — and even early death.

After what they call "staggering statistics" that reveal "a troubling reality", the research, published in the BMJ , is calling for UN agencies to take stronger action.

And the experts want countries like Australia to adopt similar measures used to curb smoking.

Let's unpack what they found.

What are considered ultra-processed foods?

The umbrella review used the Nova food classification system to define ultra-processed foods (UPF).

Nova is a widely used system that aims at classifying food products according to the nature, extent and purpose of industrial processing.

It classes UPFs as a broad range of ready-to-eat products, including packaged snacks, soft drinks, instant noodles, and ready-made meals.

Researchers also specifically mentioned foods such as packaged baked goods, ice-cream, sugary cereal, chips, lollies and biscuits.

These types of products are characterised as "industrial formulations".

Essentially, UPFs are "products made up of foods that have undergone significant processing and no longer resemble the raw ingredients," said Charlotte Gupta from the Appleton Institute at Central Queensland University.

UPFs are primarily composed of chemically modified substances extracted from foods, along with additives to enhance taste, texture, appearance and durability, with minimal to no inclusion of whole foods.

They also tend to be high in added sugar, fat, and salt, and low in vitamins and fibre.

How much do Australians consume ultra-processed foods?

Based on analyses of worldwide UPF sales data and consumption, the review said there was a shift towards an increasingly ultra-processed global diet.

However, there were considerable differences across countries and regions.

In high-income countries including Australia and the US, the share of dietary energy derived from UPFs ranges from 42 per cent and 58 per cent, respectively.

"Ultra-processed foods, laden with additives and sometimes lacking in essential nutrients, have become ubiquitous in the Australian diet," said Daisy Coyle, research fellow and accredited practising dietitian at The George Institute for Global Health.

"In fact, they make up almost half of what we buy at the supermarket."

The total energy intake from UPFs was as low as 10 per cent and 25 per cent in Italy and South Korea, the review found.

Whereas, for low- and middle-income countries such as Colombia and Mexico, the total energy intake ranged from 16 to 30 per cent.

What are junk foods putting us at risk of?

Overall, the review found that higher exposure to UPFs was consistently associated with an increased risk of 32 adverse health outcomes.

These include cancer, major heart and lung conditions, mental health disorders, and early death.

The researchers stressed that this kind of study "cannot prove the junk food is causing the health problems".

However, they say there is consistent evidence that these types of junk foods are "associated with death of any cause" and specific health conditions.

"While these associations are interesting and warrant further high quality research, they do not and cannot provide evidence of causality," Alan Barclay, a consultant dietitian and nutritionist from the University of Sydney, said in a statement to the Australian Science Media Centre.

The review found "convincing evidence" higher junk food intake was associated with:

- About a 50 per cent increased risk of cardiovascular disease-related death

- A 48 to 53 per cent higher risk of anxiety and common mental disorders

- A 12 per cent greater risk of type 2 diabetes

There was "highly suggestive evidence" for:

- A 21 per cent greater risk of death from any cause

- A 40 to 66 per cent increased risk of heart disease-related death, obesity, type 2 diabetes, and sleep problems

- A 22 per cent increased risk of depression.

"The statistics are staggering – these foods may double your risk of dying from heart disease or from developing a mental health disorder," Dr Coyle said.

There was also evidence for associations between UPFs and asthma, gastrointestinal health, and cardiometabolic diseases but the evidence was limited.

The researchers acknowledged that there were limitations with an umbrella review and they couldn't rule out the possibility that other factors and variations assessing UPF intake may have influenced their results.

Does Australia need to take a tobacco approach to junk food?

The researchers say the findings call for urgent research and public health actions to minimise ultra-processed food consumption.

They want United Nations agencies to consider a framework similar to the approaches taken to tobacco.

For instance, including warning labels on food packaging, restricting advertising and banning junk food being sold near schools.

Currently, Australia has voluntary programs which encourage companies to cut the salt, sugar and fat level from their foods.

There are also health star ratings on foods, but only around 40 per cent of products carry the labels, Dr Coyle told the ABC.

She said more needs to be done to enforce these measures and make them mandatory.

"Existing nutrition policies in Australia aren’t enough to tackle this problem," she said.

"We've put up with voluntary measures and they don't work we don't see changes … Australia is not going in a healthy direction."

Putting warning labels on food, like what we have on cigarette packets, has been effective in places like South America, Dr Coyle said.

Because they are designed to put consumers off purchasing unhealthy products, they put pressure on companies to make improvements to their food.

"Companies don't want to put them on their product so they cut levels of salt and sugar, for instance," she said.

The ABC has reached out to the Australian Food and Grocery Council for comment.

Researchers say there also needs to be more consideration around availability and access to fresh and healthy food.

And more support should be provided to family farmers, and independent businesses that grow, make, and sell unprocessed or minimally processed foods.

- X (formerly Twitter)

Related Stories

Experts say we've become dependent on ultra-processed foods. how did we get here.

Ultra-processed food can be hard to spot. Here are eight to keep off the shopping list

How to spot ultra-processed foods (hint: it's all in the label)

- Food Safety

- Food and Beverage Processing Industry

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Children's Health

If you think kids are eating mostly junk food, a new study finds you're right.

Xcaret Nuñez

Researchers found that 67% of calories consumed by children and adolescents in the U.S. came from ultra-processed foods in 2018, a jump from 61% in 1999. The nationwide study analyzed the diets of 33,795 children and adolescents. Drazen Stader / EyeEm/Getty Images hide caption

Researchers found that 67% of calories consumed by children and adolescents in the U.S. came from ultra-processed foods in 2018, a jump from 61% in 1999. The nationwide study analyzed the diets of 33,795 children and adolescents.

Kids and teens in the U.S. get the majority of their calories from ultra-processed foods like frozen pizza, microwavable meals, chips and cookies, a new study has found.

Two-thirds — or 67% — of calories consumed by children and adolescents in 2018 came from ultra-processed foods, a jump from 61% in 1999, according to a peer-reviewed study published in the medical journal JAMA . The research, which analyzed the diets of 33,795 youths ages 2 to 19 across the U.S., noted the "overall poorer nutrient profile" of the ultra-processed foods.

"This is particularly worrisome for children and adolescents because they are at a critical life stage to form dietary habits that can persist into adulthood," says Fang Fang Zhang , the study's senior author and a nutrition and cancer epidemiologist at Tufts University's Friedman School of Nutrition Science and policy. "A diet high in ultra-processed foods may negatively influence children's dietary quality and contribute to adverse health outcomes in the long term."

It's Not Just Salt, Sugar, Fat: Study Finds Ultra-Processed Foods Drive Weight Gain

One reason for the increase may be the convenience of ultra-processed foods, Zhang says. Industrial processing, such as changing the physical structure and chemical composition of foods, not only gives them a longer shelf life but also a more appetizing taste.

"Things like sugar, corn syrup, some hemp oil and other ingredients that we usually don't usually use in our kitchen, that are extracted from foods and synthesized in the laboratory, those are being added in the final product of ultra-processed foods," Zhang said. "A purpose of doing this is to make them highly palatable. So kids will like those foods that somehow make it hard to resist."

Shots - Health News

Cheap, legal and everywhere: how food companies get us 'hooked' on junk.

During the same two-decade period when the study data was collected, the consumption of unprocessed or minimally processed foods decreased to 23.5% from 28.8%, the study found.

The greatest increase in calories came from ready-to-eat or ready-to-heat meals such as pizza, sandwiches and hamburgers, rising to 11.2% of calories from 2.2%. Packaged sweet snacks and treats such as cakes and ice cream were a runner-up, which made up 12.9% of calorie consumption in 2018, compared with 10.6% in 1999.

When broken down by race and ethnicity, the growth in consumption of ultra-processed foods was significantly higher for Black, non-Hispanic youth, compared to white, non-Hispanic youths. The study also noted that Mexican American youths consumed ultra-processed foods at a persistently lower rate, which the researchers said may indicate more home cooking by Hispanic families.

Opinion: Why Ditching Processed Foods Won't Be Easy — Barriers To Cooking From Scratch

The study also found that the education levels of parents or family income didn't affect consumption of ultra-processed foods, suggesting that these types of foods are common in many households.

But the responsibility for tackling this problem shouldn't fall only on parents, Zhang says.

While she would encourage parents and children to consider "replacing ultra-processed foods with minimally and unprocessed foods," Zhang says changes at the policy level are needed "to achieve a broader and more sustainable impact."

Want Kids To Eat More Veggies? Market Them With Cartoons

Take, for instance, consumption of soda. The consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages dropped to 5.3% from 10.8% of overall calories. The study's researchers noted that the decline could be related to efforts such as soda taxes and raising awareness about the effects sugar has on youth health .

"We may have won this battle, at least partially, for some sugary beverages," Zhang says, "but we haven't yet against ultra-processed foods."

This widespread reliance on junk food is an increasing public health concern as the obesity rate has been rising steadily among U.S. youths for the past two decades.

While the study's authors said that the relationship between childhood obesity and ultra-processed foods is complex, they acknowledge that "cohort studies provide consistent evidence suggesting high intake of ultra-processed foods contributes to obesity in children and young adults."

Indeed, a 2019 study by researchers at the National Institutes of Health found that a diet filled with ultra-processed foods encourages people to overeat and gain weigh t compared to diets that consist of whole or minimally processed foods.

- child nutrition

- food and nutrition

- American diet

- Senior Leadership

- Orange County

- Diversity, Equity and Inclusion

- Distinguished Speakers

- Undergraduate

- Full-Time MBA

- Executive MBA

- Master of Finance

- Master of Innovation and Entrepreneurship

- Master of Professional Accountancy

- Master of Science in Business Analytics

- Master of Science in Biotechnology Management

- Experiences

- Faculty Advisors

- Student Directory

- Leadership Development

- Future Leaders Initiative Program

- Investments, Financial Planning and You

- Digital Learning

- Academic Areas

- Research Abstracts

- Research Colloquia

- Research in Action

- Beall Center for Innovation and Entrepreneurship

- Center for Digital Transformation

- Center for Global Leadership

- Center for Health Care Management and Policy

- Todd and Lisa Halbrook Center for Investment and Wealth Management

- Center for Real Estate

- Employer Partners

- Student Career Services

- Talent Design Studio

- SOCIAL MEDIA

- IN THE MEDIA

- Press Releases

Exposing the Dangers of Targeting Children as Consumers

July 03, 2024 • By The UCI Paul Merage School of Business

Over 50 years ago, studies were done to determine how advertising to children affected their consumption of junk food, cigarettes and alcohol. The results underscored the need to focus more research on the well-being of underage consumers and the influence of marketing on their physical, emotional and mental health.

In the decades since those early studies, academics have continued to explore the interaction between kids and marketing. Professor Connie Pechmann of the UCI Paul Merage School of Business, together with several colleagues from distinguished business schools across the country, has been studying the topic’s history to gain insights that may be useful to policy makers and others.

Pechmann joined Deborah Roedder John, professor of marketing at Carlson School of Management at the University of Minnesota, and Lan Nguyen Chaplin, professor of marketing at the Department of Integrated Marketing Communications, Northwestern University, in coediting a series of papers that provide an overview of the last 50 years of research on the consumer behavior of children. Their lead article, “Understanding the Past and Preparing for Tomorrow: Children and Adolescent Consumer Behavior Insights from Research in Our Field,” was published in April 2024 in the Journal of the Association for Consumer Research , the world’s largest global consumer research organization.

“We’ve been studying children and adolescent consumer behavior for 50 years,” says Pechmann. “The focus has always been on risks to their health and mental well-being. However, the target has changed over time. We started out with television advertising being the greatest risk, but now it’s moved toward social media, cannabis, vape and poverty.”

Overcoming Obstacles to Protect Children

As necessary as it is to understand how advertising negatively affects children, Pechmann says the research can be very difficult. “There isn’t a lot of research done on children because they’re such a protected group. You have to go through many more hurdles. Parents, of course, want to protect their children, and if the activities are illegal—like alcohol or cannabis—parents don’t want to reveal the information, so it makes it even harder.” The necessity of anonymity further limits the potential scope of research, because it prevents researchers from monitoring a subject’s progress over time.

Parents can be a source of complication as well. During interviews, parents can interfere with the process, which can reduce the accuracy of a child’s answers.

Such barriers haven’t stopped Pechmann and her coauthors from studying the consequences of advertising on children and their behaviors. “Everyone is very passionate about children,” she says. “We all started out as children. Many of us have children, so everyone is interested in protecting children and adolescents.”

To overcome the challenges associated with researching children and their consumer behaviors, Pechmann and her coauthors had to be creative. “Several of us arranged to go into schools, and we offered the schools something in return: drug education, for example,” she says. “In exchange for an hour of class time to collect data, we provided an additional class period of drug education to fill their state requirements. It’s not easy, but if you work hard, you can do it.”

Leveraging Government Surveys and Social Media

Some user data on children were available through social media and government surveys. “In Canada, the government decided to do a very large survey of children and adolescents on smoking,” says Pechmann. “California also does a healthy kids survey. Of course it’s anonymous, but they also go through schools, and they provide the data for free. Every once in a while, if we’re trying to reach really young children or children and their parents, we will work through a preschool or a nonprofit group that helps with parenting and very young children.”

Providing a Historical Overview of Childhood Research

In their article, Pechmann and her colleagues provide a historical overview of research on child consumers. “We start out looking at the ’70s and ’80s research on television advertising to children,” says Pechmann. “That was the main issue at the time. In the ’80s and ’90s we studied media literacy and how to teach children to become more savvy consumers. We also studied parenting behavior because parents have a huge influence on their kids. This led to a classification of parenting styles.”

It wasn’t until the mid-1990s through around 2010 that researchers started to look into children’s use of cigarettes and alcohol. “These products are illegal for children to use,” says Pechmann, “so we wanted to understand how they were using them and why. 2010 was also the year we started to study food because of rising childhood obesity rates, which has now spread globally.”

In 2020 research shifted to the effects of social media on children. “The average teenager spends eight and a half hours a day in front of a screen,” Pechmann says. “It’s frightening. Twenty-two percent of adolescent deaths in the United States are from suicide. We don’t always think about the mental health issues that result from these activities.”

In addition to social media consumption, researchers have also looked at how poverty shapes children. “One in six youth who are 17 or younger live in poverty in the United States,” says Pechmann. “That number is increasing, but we also need to talk about multiculturalism because that’s also increasing substantially. Until now, our focus has always been on white youth. We need to focus on Black and Brown children and the issues relevant to them.”

Exposing the Impact of Media and Advertising on Children

Pechmann is optimistic about the positive news coming from the research. “In 2004 the EU finally decided to ban advertising to children and adolescents,” she says. “That was something the United States tried to do in the ’70s and ’80s, but it didn’t succeed. There are some examples of successes, like when we see the smoking rate declined massively because there was so much attention on youth and smoking in the ’90s.”

Youth smoking was in decline until Juul came along with different flavors of vape. “Then it went back up again. Sometimes we close the door, and it opens back up, or it’s a slightly different door.”

The reason why this research is so important is that, up until age 18, young people are highly vulnerable to advertising. “There’s a lot of neuroscience that explains why adolescents and children are so vulnerable,” says Pechmann. “They’re much more attuned to rewards, much less attentive to consequences and risks, much more tolerant of ambiguity, much more sensitive to social cues and much more impulsive, so they don’t have a lot of cognitive control.” This is an advertiser’s dream, she says.

The Importance of Proper Parenting

While the research sometimes seems like it contains an abundance of dismal news, Pechmann wants to emphasize the silver lining. “We’ve learned a lot about what makes a good parent,” she says. “I’m not sure how easy it is to train parents, but we have extensive research that says the best parenting style is authoritative—not authoritarian where you boss [your children] around.”

Parents definitely need to set rules and boundaries, establish consequences, and set expectations so their children don’t make too many troubling choices, she says. “You have to be flexible. If you establish a punishment, it should be a reasonable punishment.”

Emphasizing the Value of Media Literacy

One positive takeaway from the research is the importance of media literacy. “We’ve made a lot of progress in this area because we now really understand how to teach that,” says Pechmann. “For example, California just passed a law that says they have to cover media literacy from elementary school through high school, and we know what to teach.”

Educational strategies must be adjusted for the student’s age, she says. “If someone is 7 or 8 years old, you can’t teach them the same thing as if they’re 17. When they’re 17, you can talk about tobacco companies targeting them. When they’re 7, you can teach them there’s such a thing as an ad that tries to persuade them to do something.” Yet, they have difficulty grasping that idea. “Let them know there’s an agenda behind the ad, and advertisers are likely to exaggerate the benefits. That’s where you start. There’s a lot of guidance here.”

One fascinating aspect of their research showed that the most effective deterrent to smoking, for example, was not to focus on the negative health effects but on social acceptability. “The Truth campaign made big gains against tobacco by saying smoking was socially unacceptable,” says Pechmann.

“That seems to be the way to go because young people don’t expect to live to be 70 years old. They think middle age is 30 or 40, so it doesn’t work to talk about the long-term health effects of smoking. The old anti-smoking and anti-drug messages were very much health-based: ‘Here’s your lung after smoking for years,’ and ‘here’s your brain on drugs.’ That approach has hopefully disappeared because it doesn’t work. Young people want immediate rewards, but they do not want immediate rejection from their friends for being uncool.”

How Persistence Pays Off

When it comes to advocating for children, Pechmann has learned persistence is key. “Today around 14 states have passed media literacy laws,” she says. “You have to be very persistent. If you just keep putting the articles out, and you keep sharing the data, it may take up to 50 years, but eventually we can start to legislate educational programs that benefit children and adolescents.”

The lesson here is to keep going, she says. “We can’t expect an immediate response. It’s taken 40 years, and we’re finally getting traction. The people who did the early research are about to retire, and it’s only now making a difference. That’s the lesson we have to learn as researchers. We are having an impact, but it might take a while.”

Derek Powell, MBA '98: Breaking Barriers and Building Inclusive Workplaces

Innovation and Service Take the Spotlight at Dean's Leadership Circle Grant Pitch Competition

Pamina Barkow Honored with Lauds and Laurels Distinguished Alumni Award

Alumni Ambassador Award Winner Chris Song Sets New Standard for Excellence

Jethro Rothe-Kushel

Associate Director of Communications [email protected]

- Follow us on LinkedIn

- Follow us on Facebook

- Follow us on Instagram

- Follow us on Twitter

- Follow us on YouTube

- Follow us on Flickr

- UCI Homepage

- UCI Outlook

- Privacy Policy

- Staff Directory

- Merage Student Association

- Merage School Store

The numbers are in: Junk food’s toll on physical & mental health

Consuming ultra-processed food, commonly known as junk food, has been associated with a higher risk of more than 30 different adverse mental and physical health outcomes, according to a new study. The research highlights the wide range of health issues that eating this kind of food can cause.

We’re often told that to maintain good health, we need to eat well, which includes a balanced diet low in ultra-processed foods (UPF), which includes packaged baked goods and snacks, sweetened, carbonated drinks, candy, sugary cereals, and ready-to-eat products.

While many of us are well aware of the health risks associated with eating a diet high in UPF, we might not appreciate just how harmful they can be. Researchers have pooled the data from 45 distinct meta-analysis studies associating UPF with adverse health outcomes, providing a high-level summary – an ‘umbrella review’ – of the evidence.