- Curriculum and Instruction Master's

- Reading Masters

- Reading Certificate

- TESOL Master's

- TESOL Certificate

- Educational Administration Master’s

- Educational Administration Certificate

- Autism Master's

- Autism Certificate

- Leadership in Special and Inclusive Education Certificate

- High Incidence Disabilities Master's

- Secondary Special Education and Transition Master's

- Secondary Special Education and Transition Certificate

- Virtual Learning Resources

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Video Gallery

- Financial Aid

Different Learning Styles—What Teachers Need To Know

The concept of “learning styles” has been overwhelmingly embraced by educators in the U.S. and worldwide. Studies show that an estimated 89% of teachers believe in matching instruction to a student’s preferred learning style (Newton & Salvi, 2020). That’s a problem—because research tells us that this approach doesn’t work to improve learning.

What Do We Mean by “Learning Styles”?

It’s true that people have fairly stable strengths and weaknesses in their cognitive abilities, such as processing language or visual-spatial stimuli. People can also have preferences in the way they receive information—Joan may prefer to read an article while Jay may rather listen to a lecture.

The “learning styles” theory makes a big leap, suggesting that students will learn better if they are taught in a manner that conforms to their preferences. More than 70 different systems have been developed that use student questionnaires/self-reports to categorize their supposed learning preferences.

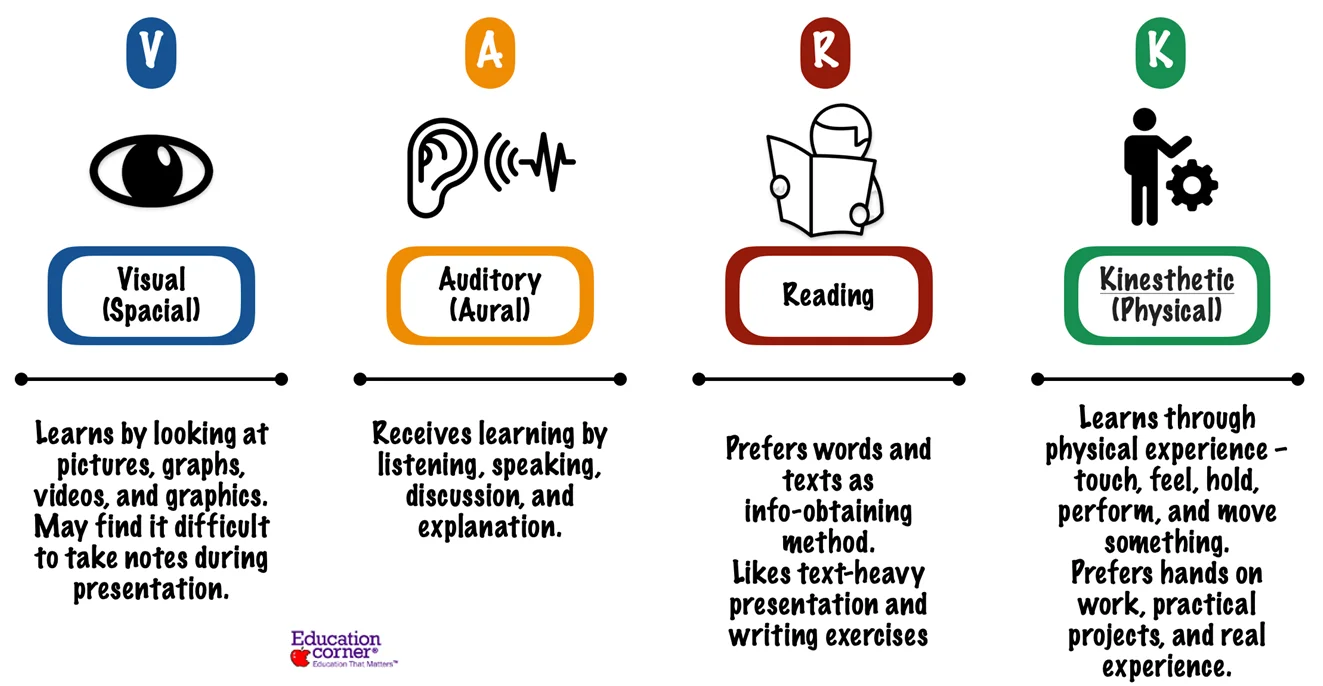

VARK Learning Styles

One of the most popular learning styles inventories used in schools is the VARK system (Cuevas, 2015). Students answer 25 multiple-choice questions that range from how they like their teachers to teach (discussions and guest speakers, textbooks and handouts, field trips and labs, or charts and diagrams) to how they would give directions to a neighbor’s house (draw a map, write out directions, say them aloud, or walk with the person) (VARK Learn Limited, 2021). Based on their responses, the system classifies them as Visual, Auditory, Read-write, and/or Kinesthetic learners and recommends specific learning strategies.

If only it were that simple. While this brief survey may provide some insights for teachers, we must be wary of overestimating the value of the results. By placing students in categories that reflect “preferred learning styles,” we run the risk of oversimplifying the complex nature of teaching and learning to the detriment of our students.

What Does the Science Say?

Study after study has shown that matching instructional mode to a student’s supposedly identified “learning style” does not produce better learning outcomes. In fact, a student’s “learning style” may not even predict the way they prefer to be taught or the way they actually choose to study on their own (Newton & Salvi, 2020).

Simply put, students’ learning preferences as identified via questionnaires do not predict the singular, best way to teach them. A single student may learn best with one approach in one subject and a different one in another. The best approach for them may even vary day-to-day. Most likely, students are best served when a variety of strategies are employed in a lesson.

As appealing as a framework like VARK is—relatively easy to conceptualize and quick to assess—everyone engages in different modes of learning in various ways. The brain processes information in very complex and nuanced ways that can’t be so simply generalized.

Fads are common in education. Having been embraced for several decades, though, “learning styles” has moved beyond fad to what experts refer to as “neuromyth,” one of many “commonly accepted, erroneous beliefs based on misunderstandings of neuroscience that contribute to pseudoscientific practice within education (Ruhaak & Cook, 2018). In fact, the idea that “students learn best when teaching styles are matched to their learning styles” earned a spot in 50 Great Myths of Popular Psychology (Lilienfeld, Lynn, & Beyerstein, 2009), alongside “Extrasensory perception is a well-established scientific phenomenon” and “Our handwriting reveals our personality traits.”

Unfortunately, the myth has become so prevalent that the majority of papers written about learning styles are based on the assumption that matching teaching style to learning style is desirable (Newton, 2015). It’s no surprise, then, that well-intentioned educators (and parents and caregivers) buy into the concept as well.

What Harm Does It Do?

When a student is pigeonholed as a particular “type” of learner, and their lessons are all prepared with that in mind, they could be missing out on other learning opportunities with a better chance of success.

Adapting instruction to individual students’ “learning styles” is no small task—and teachers who attempt to do so are clearly motivated to find the best way to help their students. They could put their time to better use, though.

Better Learning Style Approaches

Universal Design for Learning (UDL) is an evidence-driven framework for improving and optimizing learning for all students. When a learning opportunity provides for 1) multiple means of engagement, 2) multiple means of representation, and 3) multiple means of action and expression, different styles of learning are accounted for at the outset, reducing the need to personalize every activity. Nonprofit CAST.org, where KU Special Education Professor Jamie Basham is Senior Director for Learning & Innovation, offers free UDL Guidelines, with detailed information on how to optimize learning for all your students.

Operating within a UDL framework, teachers should use Evidence-based Practices (EBPs)—specific teaching techniques and interventions that have sufficient published, peer-reviewed studies that demonstrate their effectiveness in addressing specific issues with particular populations of students. (We discussed EBPs for autism spectrum disorder in a previous blog.) In addition, the Council for Exceptional Children recommends a core set of High Leverage Practices –basic, foundational practices that every special education teacher should know and perform fluently.

Evidence-based Learning Style Approaches at KU Special Education

Faculty in the University of Kansas Department of Special Education are world-renowned for their research in UDL and evidence-based special education practices. Students can be assured that our online master’s degrees and graduate certificates focus on research-based teaching and assessment methods—just one of the reasons we’ve been rated the #1 Best Online Master’s Degree in Special Education by U.S. News & World Report for two years in a row. 1

Explore our special education programs and consider how earning an online master’s from a Top 10 Best Education School (among public universities) can help you achieve your goals

CAST (2018). Universal Design for Learning Guidelines version 2.2. Retrieved March 4, 2021 from udlguidelines.cast.org.

Cuevas, J. (2015). Is learning styles-based instruction effective? A comprehensive analysis of recent research on learning styles. Theory & Research in Education. 13 (3), 308–333. doi.org/10.1177/1477878515606621

Lilienfeld, S., Lynn, J., Rucio, J., & Beyerstein, B. (2009) 50 great myths of popular psychology: Shattering widespread misconceptions about human behavior. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN: 978-1405131117

Newton, P. M. (2015). The learning styles myth is thriving in higher education. Frontiers in Psychology, 6 , 1908. doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01908

Newton, P. M. & Salvi, A. (2020). How common is belief in the learning styles neuromyth, and does it matter? A pragmatic systematic review. Frontiers in Education, 5 (602451), 1-14. doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2020.602451

Pashler, H., McDaniel, M., Rohrer, D., and Bjork, R. (2008). Learning styles: Concepts and evidence. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 9 , 105–119. doi.org/10.1111/j.1539-6053.2009.01038.x

Ruhaak, A. E., & Cook, B. G. (2018). The prevalence of educational neuromythings among pre-service special education teachers. Mind, Brain, and Education. 12 (3) 155-161. doi.org/10.1111/mbe.12181

1 Retrieved on May 13, 2021, from usnews.com/best-graduate-schools/top-education-schools/university-of-kansas-06075 2 Retrieved on May 13, 2021, from usnews.com/best-graduate-schools/top-education-schools/edu-rankings

Return to Blog

IMPORTANT DATES

Stay connected.

Link to twitter Link to facebook Link to youtube Link to instagram

The University of Kansas has engaged Everspring , a leading provider of education and technology services, to support select aspects of program delivery.

The University of Kansas prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, ethnicity, religion, sex, national origin, age, ancestry, disability, status as a veteran, sexual orientation, marital status, parental status, retaliation, gender identity, gender expression and genetic information in the University's programs and activities. The following person has been designated to handle inquiries regarding the non-discrimination policies and is the University's Title IX Coordinator: the Executive Director of the Office of Institutional Opportunity and Access, [email protected] , 1246 W. Campus Road, Room 153A, Lawrence, KS, 66045, (785) 864-6414 , 711 TTY.

Create Your Course

The 7 main types of learning styles (and how to teach to them), share this article.

Understanding the 7 main types of learning styles and how to teach them will help both your students and your courses be more successful.

When it comes to learning something new, we all absorb information at different rates and understand it differently too. Some students get new concepts right away; others need to sit and ponder for some time before they can arrive at similar conclusions.

Why? The answer lies in the type of learning styles different students feel more comfortable with. In other words, we respond to information in different ways depending on how it is presented to us.

Clearly, different types of learning styles exist, and there are lots of debates in pedagogy about what they are and how to adapt to them.

For practical purposes, it’s recommended to ensure that your course or presentation covers the 7 main types of learning.

In this article, we’ll break down the 7 types of learning styles, and give practical tips for how you can improve your own teaching styles , whether it’s in higher education or an online course you plan to create on the side.

Skip ahead:

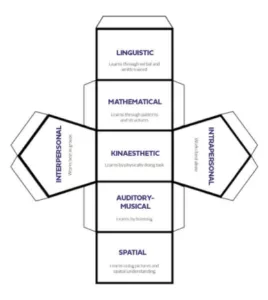

What are the 7 types of learning styles?

How to accommodate different types of learning styles online.

- How to help students understand their different types of learning styles

How to create an online course for all

In the academic literature, the most common model for the types of learning you can find is referred to as VARK.

VARK is an acronym that stands for Visual, Auditory, Reading & Writing, and Kinesthetic. While these learning methods are the most recognized, there are people that do not fit into these boxes and prefer to learn differently. So we’re adding three more learning types to our list, including Logical, Social, and Solitary.

Visual learners

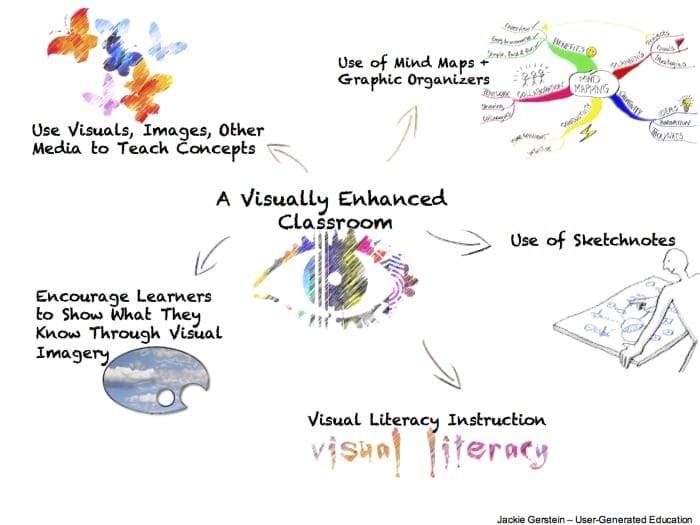

Visual learners are individuals that learn more through images, diagrams, charts, graphs, presentations, and anything that illustrates ideas. These people often doodle and make all kinds of visual notes of their own as it helps them retain information better.

When teaching visual learners, the goal isn’t just to incorporate images and infographics into your lesson. It’s about helping them visualize the relationships between different pieces of data or information as they learn.

Gamified lessons are a great way to teach visual learners as they’re interactive and aesthetically appealing. You should also give handouts, create presentations, and search for useful infographics to support your lessons.

Since visual information can be pretty dense, give your students enough time to absorb all the new knowledge and make their own connections between visual clues.

Auditory/aural learners

The auditory style of learning is quite the opposite of the visual one. Auditory learners are people that absorb information better when it is presented in audio format (i.e. the lessons are spoken). This type of learner prefers to learn by listening and might not take any notes at all. They also ask questions often or repeat what they have just heard aloud to remember it better.

Aural learners are often not afraid of speaking up and are great at explaining themselves. When teaching auditory learners, keep in mind that they shouldn’t stay quiet for long periods of time. So plan a few activities where you can exchange ideas or ask questions. Watching videos or listening to audio during class will also help with retaining new information.

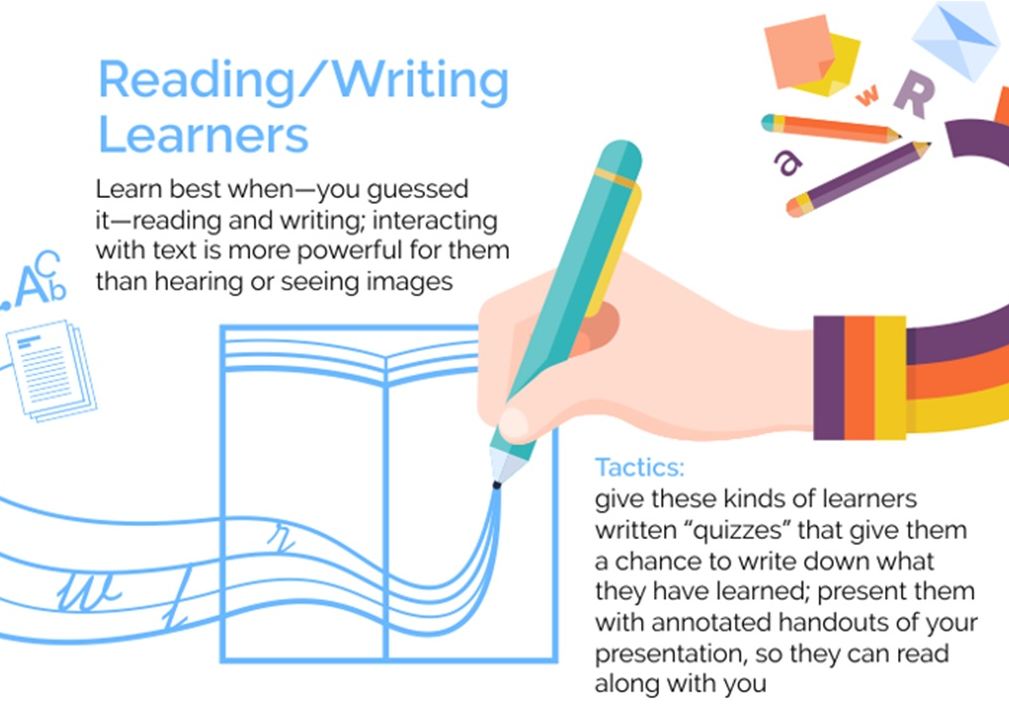

Reading and writing (or verbal) learners

Reading & Writing learners absorb information best when they use words, whether they’re reading or writing them. To verbal learners, written words are more powerful and granular than images or spoken words, so they’re excellent at writing essays, articles, books, etc.

To support the way reading-writing students learn best, ensure they have time to take ample notes and allocate extra time for reading. This type of learner also does really well at remote learning, on their own schedule. Including reading materials and writing assignments in their homework should also yield good results.

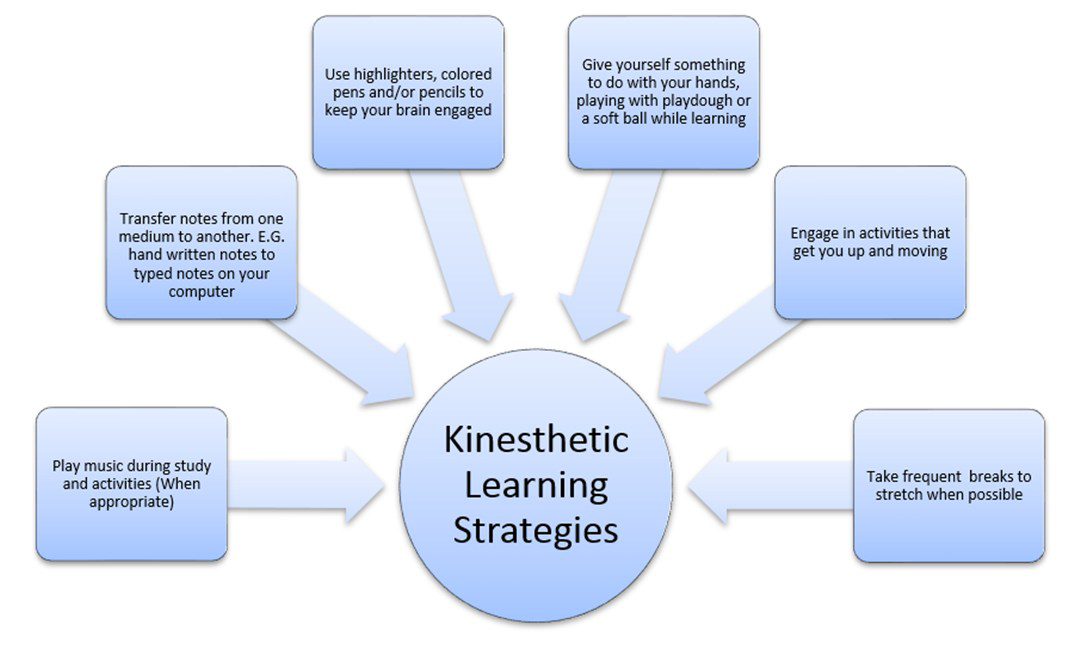

Kinesthetic/tactile learners

Kinesthetic learners use different senses to absorb information. They prefer to learn by doing or experiencing what they’re being taught. These types of learners are tactile and need to live through experiences to truly understand something new. This makes it a bit challenging to prepare for them in a regular class setting.

As you try to teach tactile learners, note that they can’t sit still for long and need more frequent breaks than others. You need to get them moving and come up with activities that reinforce the information that was just covered in class. Acting out different roles is great; games are excellent; even collaborative writing on a whiteboard should work fine. If applicable, you can also organize hands-on laboratory sessions, immersions, and workshops.

In general, try to bring every abstract idea into the real world to help kinesthetic learners succeed.

Logical/analytical learners

As the name implies, logical learners rely on logic to process information and understand a particular subject. They search for causes and patterns to create a connection between different kinds of information. Many times, these connections are not obvious to people to learn differently, but they make perfect sense to logical learners.

Logical learners generally do well with facts, statistics, sequential lists, and problem-solving tasks to mention a few.

As a teacher, you can engage logical learners by asking open-ended or obscure questions that require them to apply their own interpretation. You should also use teaching material that helps them hone their problem-solving skills and encourages them to form conclusions based on facts and critical thinking.

Social/interpersonal learners

Social or interpersonal learners love socializing with others and working in groups so they learn best during lessons that require them to interact with their peers . Think study groups, peer discussions, and class quizzes.

To effectively teach interpersonal learners, you’ll need to make teamwork a core part of your lessons. Encourage student interaction by asking questions and sharing stories. You can also incorporate group activities and role-playing into your lessons, and divide the students into study groups.

Solitary/intrapersonal learners

Solitary learning is the opposite of social learning. Solitary, or solo, learners prefer to study alone without interacting with other people. These learners are quite good at motivating themselves and doing individual work. In contrast, they generally don’t do well with teamwork or group discussions.

To help students like this, you should encourage activities that require individual work, such as journaling, which allows them to reflect on themselves and improve their skills. You should also acknowledge your students’ individual accomplishments and help them refine their problem-solving skills.

Are there any unique intelligence types commonly shared by your students? Adapting to these different types of intelligence can help you can design a course best suited to help your students succeed.

Launch your online learning product for free

Use Thinkific to create, market, and sell online courses, communities, and memberships — all from a single platform.

How to help students understand their different types of learning styles

Unless you’re teaching preschoolers, most students probably already realize the type of learning style that fits them best. But some students do get it wrong.

The key here is to observe every student carefully and plan your content for different learning styles right from the start.

Another idea is to implement as much individual learning as you can and then customize that learning for each student. So you can have visual auditory activities, riddles for logical learners, games for kinesthetic learners, reading activities, writing tasks, drawing challenges, and more.

When you’re creating your first course online, it’s important to dedicate enough time to planning out its structure. Don’t just think that a successful course consists of five uploaded videos.

Think about how you present the new knowledge. Where it makes sense to pause and give students the time to reflect. Where to include activities to review the new material. Adapting to the different learning types that people exhibit can help you design an online course best suited to help your students succeed.

That being said, here are some tips to help you tailor your course to each learning style, or at least create enough balance.

Visual learners

Since visual learners like to see or observe images, diagrams, demonstrations, etc., to understand a topic, here’s how you can create a course for them:

- Include graphics, cartoons, or illustrations of concepts

- Use flashcards to review course material

- Use flow charts or maps to organize materials

- Highlight and color code notes to organize materials

- Use color-coded tables to compare and contrast elements

- Use a whiteboard to explain important information

- Have students play around with different font styles and sizes to improve readability

Auditory learners prefer to absorb information by listening to spoken words, so they do well when teachers give spoken instructions and lessons. Here’s how to cater to this learning type through your online course:

- Converse with your students about the subject or topic

- Ask your students questions after each lesson and have them answer you (through the spoken word)

- Have them record lectures and review them with you

- Have articles, essays, and comprehension passages out to them

- As you teach, explain your methods, questions, and answers

- Ask for oral summaries of the course material

- If you teach math or any other math-related course, use a talking calculator

- Create an audio file that your students can listen to

- Create a video of you teaching your lesson to your student

- Include a YouTube video or podcast episode for your students to listen to

- Organize a live Q & A session where students can talk to you and other learners to help them better understand the subject

Reading and writing (or verbal) learners

This one is pretty straightforward. Verbal learners learn best when they read or write (or both), so here are some practical ways to include that in your online course:

- Have your students write summaries about the lesson

- If you teach language or literature, assign them stories and essays that they’d have to read out loud to understand

- If your course is video-based, add transcripts to aid your students’ learning process

- Make lists of important parts of your lesson to help your students memorize them

- Provide downloadable notes and checklists that your students can review after they’ve finished each chapter of your course

- Encourage extra reading by including links to a post on your blog or another website in the course

- Use some type of body movement or rhythm, such as snapping your fingers, mouthing, or pacing, while reciting the material your students should learn

Since kinesthetic learners like to experience hands-on what they learn with their senses — holding, touching, hearing, and doing. So instead of churning out instructions and expecting to follow, do these instead:

- Encourage them to experiment with textured paper, and different sizes of pencils, pens, and crayons to jot down information

- If you teach diction or language, give them words that they should incorporate into their daily conversations with other people

- Encourage students to dramatize or act out lesson concepts to understand them better

Logical learners are great at recognizing patterns, analyzing information, and solving problems. So in your online course, you need to structure your lessons to help them hone these abilities. Here are some things you can do:

- Come up with tasks that require them to solve problems. This is easy if you teach math or a math-related course

- Create charts and graphs that your students need to interpret to fully grasp the lesson

- Ask open-ended questions that require critical thinking

- Create a mystery for your students to solve with clues that require logical thinking or math

- Pose an issue/topic to your students and ask them to address it from multiple perspectives

Since social learners prefer to discuss or interact with others, you should set up your course to include group activities. Here’s how you can do that:

- Encourage them to discuss the course concept with their classmates

- Get your students involved in forum discussions

- Create a platform (via Slack, Discord, etc.) for group discussions

- Pair two or more social students to teach each other the course material

- If you’re offering a cohort-based course , you can encourage students to make their own presentations and explain them to the rest of the class

Solitary learners prefer to learn alone. So when designing your course, you need to take that into consideration and provide these learners a means to work by themselves. Here are some things you can try:

- Encourage them to do assignments by themselves

- Break down big projects into smaller ones to help them manage time efficiently

- Give them activities that require them to do research on their own

- When they’re faced with problems regarding the topic, let them try to work around it on their own. But let them know that they are welcome to ask you for help if they need to

- Encourage them to speak up when you ask them questions as it builds their communication skills

- Explore blended learning , if possible, by combining teacher-led classes with self-guided assignments and extra ideas that students can explore on their own.

Now that you’re ready to teach something to everyone, you might be wondering what you actually need to do to create your online courses. Well, start with a platform.

Thinkific is an intuitive and easy-to-use platform any instructor can use to create online courses that would resonate with all types of learning styles. Include videos, audio, presentations, quizzes, and assignments in your curriculum. Guide courses in real-time or pre-record information in advance. It’s your choice.

In addition, creating a course on Thinkific doesn’t require you to know any programming. You can use a professionally designed template and customize it with a drag-and-drop editor to get exactly the course you want in just a few hours. Try it yourself to see how easy it can be.

This blog was originally published in August 2017, it has since been updated in March 2023.

Althea Storm is a B2B SaaS writer who specializes in creating data-driven content that drives traffic and increases conversions for businesses. She has worked with top companies like AdEspresso, HubSpot, Aura, and Thinkific. When she's not writing web content, she's curled up in a chair reading a crime thriller or solving a Rubik's cube.

- The 5 Most Effective Teaching Styles (Pros & Cons of Each)

- 7 Top Challenges with Online Learning For Students (and Solutions)

- 6 Reasons Why Creators Fail To Sell Their Online Courses

- The Advantages and Disadvantages of Learning in Online Classes in 2023

- 10 Steps To Creating A Wildly Successful Online Course

Related Articles

The top free and paid teachable alternatives for creators.

We compare and contrast alternatives to online learning platform Teachable. Find out which alternative might be the best fit for you.

How Branded Apps Build Brand Loyalty: Research and Options

Explore several app-relevant definitions & compare branded vs unbranded apps. Backed by compelling new research on the role of branded apps in brand loyalty.

How To Create An Online Academy For Your Business

Learn how to create an online academy for your business and helpful steps to optimize your customer education program.

Try Thinkific for yourself!

Accomplish your course creation and student success goals faster with thinkific..

Download this guide and start building your online program!

It is on its way to your inbox

Center for Teaching

Learning styles, what are learning styles, why are they so popular.

The term learning styles is widely used to describe how learners gather, sift through, interpret, organize, come to conclusions about, and “store” information for further use. As spelled out in VARK (one of the most popular learning styles inventories), these styles are often categorized by sensory approaches: v isual, a ural, verbal [ r eading/writing], and k inesthetic. Many of the models that don’t resemble the VARK’s sensory focus are reminiscent of Felder and Silverman’s Index of Learning Styles , with a continuum of descriptors for how learners process and organize information: active-reflective, sensing-intuitive, verbal-visual, and sequential-global.

There are well over 70 different learning styles schemes (Coffield, 2004), most of which are supported by “a thriving industry devoted to publishing learning-styles tests and guidebooks” and “professional development workshops for teachers and educators” (Pashler, et al., 2009, p. 105).

Despite the variation in categories, the fundamental idea behind learning styles is the same: that each of us has a specific learning style (sometimes called a “preference”), and we learn best when information is presented to us in this style. For example, visual learners would learn any subject matter best if given graphically or through other kinds of visual images, kinesthetic learners would learn more effectively if they could involve bodily movements in the learning process, and so on. The message thus given to instructors is that “optimal instruction requires diagnosing individuals’ learning style[s] and tailoring instruction accordingly” (Pashler, et al., 2009, p. 105).

Despite the popularity of learning styles and inventories such as the VARK, it’s important to know that there is no evidence to support the idea that matching activities to one’s learning style improves learning . It’s not simply a matter of “the absence of evidence doesn’t mean the evidence of absence.” On the contrary, for years researchers have tried to make this connection through hundreds of studies.

In 2009, Psychological Science in the Public Interest commissioned cognitive psychologists Harold Pashler, Mark McDaniel, Doug Rohrer, and Robert Bjork to evaluate the research on learning styles to determine whether there is credible evidence to support using learning styles in instruction. They came to a startling but clear conclusion: “Although the literature on learning styles is enormous,” they “found virtually no evidence” supporting the idea that “instruction is best provided in a format that matches the preference of the learner.” Many of those studies suffered from weak research design, rendering them far from convincing. Others with an effective experimental design “found results that flatly contradict the popular” assumptions about learning styles (p. 105). In sum,

“The contrast between the enormous popularity of the learning-styles approach within education and the lack of credible evidence for its utility is, in our opinion, striking and disturbing” (p. 117).

Pashler and his colleagues point to some reasons to explain why learning styles have gained—and kept—such traction, aside from the enormous industry that supports the concept. First, people like to identify themselves and others by “type.” Such categories help order the social environment and offer quick ways of understanding each other. Also, this approach appeals to the idea that learners should be recognized as “unique individuals”—or, more precisely, that differences among students should be acknowledged —rather than treated as a number in a crowd or a faceless class of students (p. 107). Carried further, teaching to different learning styles suggests that “ all people have the potential to learn effectively and easily if only instruction is tailored to their individual learning styles ” (p. 107).

There may be another reason why this approach to learning styles is so widely accepted. They very loosely resemble the concept of metacognition , or the process of thinking about one’s thinking. For instance, having your students describe which study strategies and conditions for their last exam worked for them and which didn’t is likely to improve their studying on the next exam (Tanner, 2012). Integrating such metacognitive activities into the classroom—unlike learning styles—is supported by a wealth of research (e.g., Askell Williams, Lawson, & Murray-Harvey, 2007; Bransford, Brown, & Cocking, 2000; Butler & Winne, 1995; Isaacson & Fujita, 2006; Nelson & Dunlosky, 1991; Tobias & Everson, 2002).

Importantly, metacognition is focused on planning, monitoring, and evaluating any kind of thinking about thinking and does nothing to connect one’s identity or abilities to any singular approach to knowledge. (For more information about metacognition, see CFT Assistant Director Cynthia Brame’s “ Thinking about Metacognition ” blog post, and stay tuned for a Teaching Guide on metacognition this spring.)

There is, however, something you can take away from these different approaches to learning—not based on the learner, but instead on the content being learned . To explore the persistence of the belief in learning styles, CFT Assistant Director Nancy Chick interviewed Dr. Bill Cerbin, Professor of Psychology and Director of the Center for Advancing Teaching and Learning at the University of Wisconsin-La Crosse and former Carnegie Scholar with the Carnegie Academy for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning. He points out that the differences identified by the labels “visual, auditory, kinesthetic, and reading/writing” are more appropriately connected to the nature of the discipline:

“There may be evidence that indicates that there are some ways to teach some subjects that are just better than others , despite the learning styles of individuals…. If you’re thinking about teaching sculpture, I’m not sure that long tracts of verbal descriptions of statues or of sculptures would be a particularly effective way for individuals to learn about works of art. Naturally, these are physical objects and you need to take a look at them, you might even need to handle them.” (Cerbin, 2011, 7:45-8:30 )

Pashler and his colleagues agree: “An obvious point is that the optimal instructional method is likely to vary across disciplines” (p. 116). In other words, it makes disciplinary sense to include kinesthetic activities in sculpture and anatomy courses, reading/writing activities in literature and history courses, visual activities in geography and engineering courses, and auditory activities in music, foreign language, and speech courses. Obvious or not, it aligns teaching and learning with the contours of the subject matter, without limiting the potential abilities of the learners.

- Askell-Williams, H., Lawson, M. & Murray, Harvey, R. (2007). ‘ What happens in my university classes that helps me to learn?’: Teacher education students’ instructional metacognitive knowledge. International Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning , 1. 1-21.

- Bransford, J. D., Brown, A. L. & Cocking, R. R., (Eds.). (2000). How people learn: Brain, mind, experience, and school (Expanded Edition). Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press.

- Butler, D. L., & Winne, P. H. (1995) Feedback and self-regulated learning: A theoretical synthesis . Review of Educational Research , 65, 245-281.

- Cerbin, William. (2011). Understanding learning styles: A conversation with Dr. Bill Cerbin . Interview with Nancy Chick. UW Colleges Virtual Teaching and Learning Center .

- Coffield, F., Moseley, D., Hall, E., & Ecclestone, K. (2004). Learning styles and pedagogy in post-16 learning. A systematic and critical review . London: Learning and Skills Research Centre.

- Isaacson, R. M. & Fujita, F. (2006). Metacognitive knowledge monitoring and self-regulated learning: Academic success and reflections on learning . Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning , 6, 39-55.

- Nelson, T.O. & Dunlosky, J. (1991). The delayed-JOL effect: When delaying your judgments of learning can improve the accuracy of your metacognitive monitoring. Psychological Science , 2, 267-270.

- Pashler, Harold, McDaniel, M., Rohrer, D., & Bjork, R. (2008). Learning styles: Concepts and evidence . Psychological Science in the Public Interest . 9.3 103-119.

- Tobias, S., & Everson, H. (2002). Knowing what you know and what you don’t: Further research on metacognitive knowledge monitoring . College Board Report No. 2002-3 . College Board, NY.

Teaching Guides

- Online Course Development Resources

- Principles & Frameworks

- Pedagogies & Strategies

- Reflecting & Assessing

- Challenges & Opportunities

- Populations & Contexts

Quick Links

- Services for Departments and Schools

- Examples of Online Instructional Modules

Discover Your Learning Style – Comprehensive Guide on Different Learning Styles

People differ in the way they absorb, process, and store new information and master new skills. Natural and habitual, this way does not change with teaching methods or learning content. This is known as the Learning Style.

By discovering and better understanding learning styles, one can employ techniques to improve the rate and quality of learning. Even if one has never heard the term “learning style” before, they are likely to have some idea of what their learning style is.

For instance, one may learn better through DIY videos instead of reading manuals or pick up things faster by listening to audiobooks instead of sitting down to read. These preferences point to one’s learning style.

How can learning style help in the classroom?

Students can have a single dominant learning style or a combination of styles, which could also vary based on circumstances. While no learning style (or a mix of them) is right or wrong, knowing one’s style can significantly enhance learning.

Research has shown that a mismatch between learning style and teaching can affect students’ learning and behavior quality in class. Studies have found that good learning depends on the teaching materials used, which must align with students’ learning styles.

In recent years, there has been a big push in education on how teachers can better meet students’ needs. Learning style has proven very effective in achieving this. It helps teachers understand how students absorb information and teach effectively.

One study found that over 90% of teachers believed in the learning style idea.

Often, teachers have a lot on their plates, and adjusting instruction to suit different learning styles can sound overwhelming. However, once they master how to appeal to all learners, life in the classroom becomes much easier.

This guide will help you understand various learning styles and how teachers can use them to alter instructions and help students learn more effectively.

This improves classroom management and makes for happier students. The chatty student who constantly interrupts will finally find a positive place in the classroom. The quiet girl who knows all the answers but never raises her hand will feel confident sharing her knowledge.

How can learning style help parents?

As a parent, knowing your child’s learning style helps you find activities and resources tailored to their specific learning styles. This allows you to better connect with them and provide the support they need, which also improves relationships.

Knowing learning styles is also helpful beyond educational settings. It helps you understand how those around you learn—at work, in families, in relationships, or in other settings.

Theory Of Learning Styles

The study of learning styles began in 1910 , and formal learning style assessment instruments were developed for academics in the 1970s. By the 1980s, the VAK model, which stands for Visual, Auditory, and Kinesthetic, had gained popularity in the mainstream media.

Thanks to the Internet, VAK became freely available to teachers for assessment by 2000. Later, another dominant style, reading/writing (R), was added to the VAK model, which expanded it to the VARK model.

The VARK model

The VARK learning style model has been adjusted to include four learning modes:

- Visual (spacial) learners learn best by seeing

- Auditory (aural) learners learn best by hearing

- Reading/writing learners learn best by reading and writing

- Kinesthetic (physical) learners learn best by moving and doing

A short questionnaire is used to identify what a learner prefers to use when taking in, processing, and outputting information.

VARK helps explain why it can sometimes be frustrating to sit in a classroom and not get what’s being taught. It also explains why some students learn well from one teacher but struggle to learn from another.

As a student, if you have experienced feelings like this, they are more likely to originate from an incompatibility with your learning style.

According to Neil Fleming and David Baume , who developed VARK, teachers should understand how students learn, but it’s even more important that students themselves know how they learn.

By identifying their own learning process, students can identify and test strategies that significantly improve learning efficiency. According to Fleming and Baume,

“VARK above all is designed to be a starting place for a conversation among teachers and learners about learning. It can also be a catalyst for staff development – thinking about strategies for teaching different groups can lead to more, and appropriate, variety of learning and teaching.”

This kind of thinking is known as metacognition , which refers to an awareness and understanding of one’s thought processes and how to regulate them. Discovering your own learning style without engaging in metacognition would be impossible.

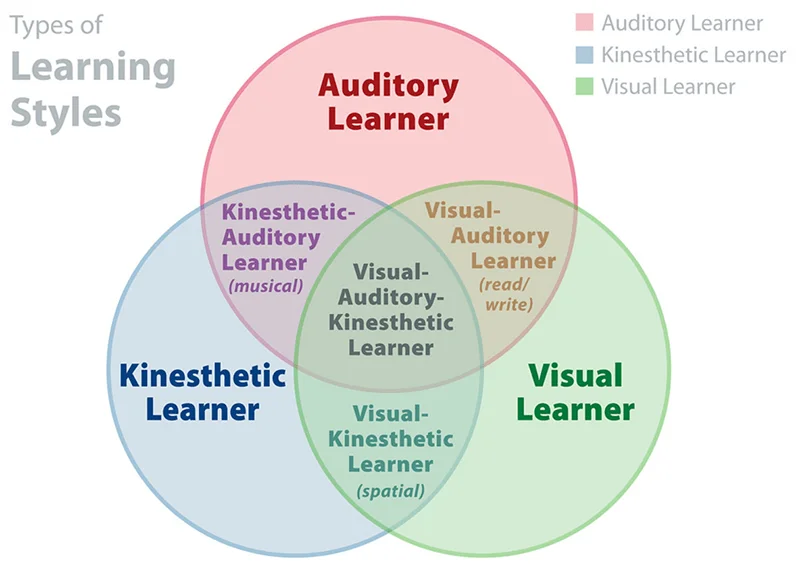

Learning styles can also be multimodal —some have one dominant style, while others combine several learning styles.

Various learning theories, in addition to VAK and VARK, have been developed over time . While the labels used in each theory differ, the learning styles they define often overlap.

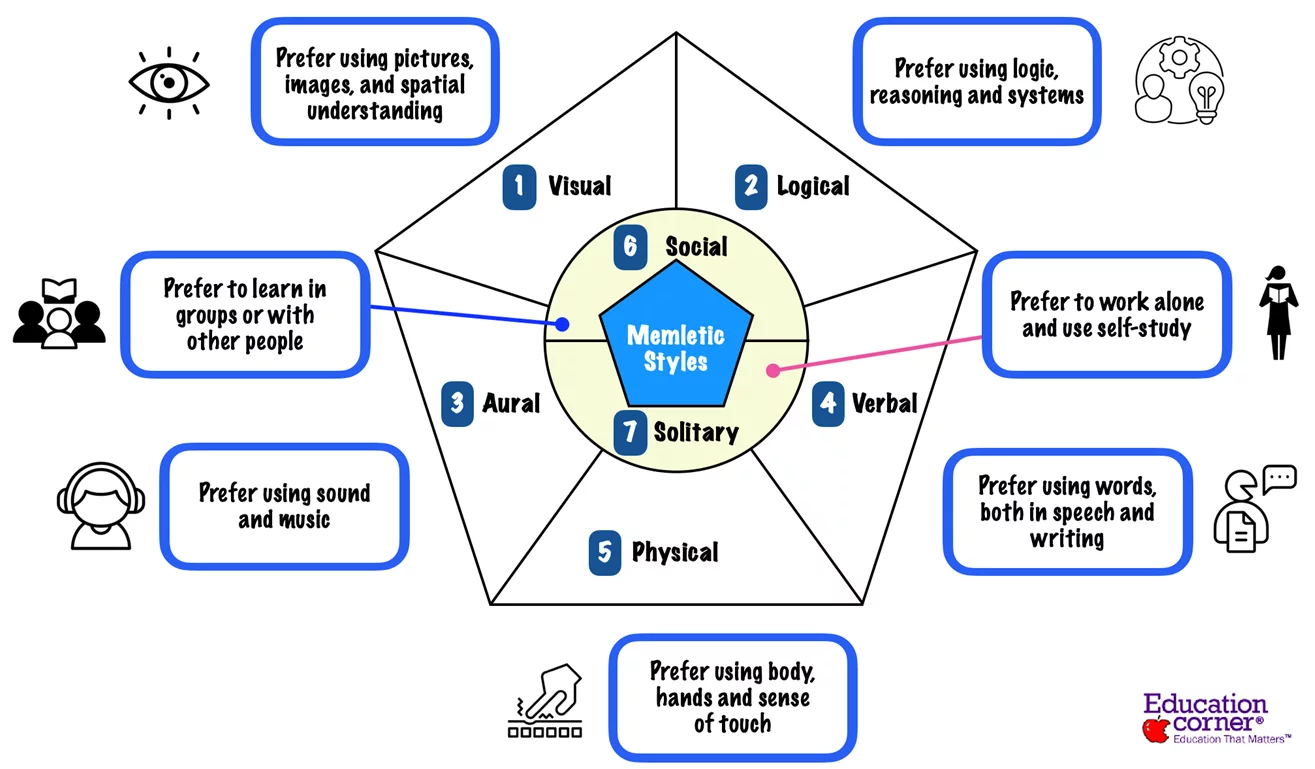

Memletics is another theory that was created in 2003 by Sean Whiteley . It expands upon the VAK model by introducing seven learning styles:

As shown, Memletics adds four more learning styles (Verbal, Logical, Social, and Solitary) to the three learning styles defined in the VAK model. However, it leaves out “Reading/Writing,” added when VAK expanded to VARK.

Due to the nature of these categories, there can be an overlap in learning styles defined in Memletics. Take two solitary learners, for instance. While both learn best in solitary situations, one may learn using logic, while the other may learn by seeing (Visual).

In a study on learning styles, Aranya Srijongjai noted that according to the Memletics model, everyone has a mix of learning styles, and learning styles are not fixed, so instructors should also accommodate other types of learning styles by providing diverse learning environments.

They should vary activities so that students learn in their preferred style and have a chance to develop other styles. Matching and mismatching learning styles and instructional methods will complement the student’s learning performance and create more flexible learners in the long run.

As Srijongjai suggests, students and teachers should not consider learning styles as boxes into which students can be placed. They are just one small piece of the overall puzzle in a student’s learning process.

No matter what learning style theory appeals to you the most, knowing your style helps make learning easier and more successful. Most learners will have at least one dominant style in the VARK theory.

This guide will offer information and advice to teachers, students, and parents to help them understand why and how people learn the way they do.

For each learning style, we have included suggestions for career choices, which in no way are meant to be limiting, but they can be helpful. If you are a visual learner but feel pulled toward one of the fields listed in the auditory learner section, by all means, pursue your passion.

These suggestions merely show what careers a person with a particular style might gravitate toward and where they are likely to excel with minimal effort.

Understanding your learning style is helpful, but again, you should also be careful not to put yourself in a box and define yourself by your learning style. The key is understanding how you learn and avoiding getting caught up in labels and classifications.

Take what insight you can, but don’t let it overcome your thoughts about yourself, as you may very well lie at the intersection of the “standard” learning styles:

Visual Learners

Do you ever remember taking a test in school and thinking, “I don’t remember the answer, but I remember I had it highlighted pink in my notes”? If the answer is yes, then you might be a visual learner.

Visual learners remember and learn best from what they see. This doesn’t necessarily have to be restricted to pictures and videos. They do well with spatial reasoning, charts, graphs, etc. Visual learners often “see” words as pictures or objects in their heads.

Visual learners use their right brain to process information. The human brain processes visual information much faster than plain text. Some reports claim that images are processed 60,000 times faster than text .

As a visual learner, you can quickly take in and retain a lot of information because you prefer this processing method that humans are already very good at.

Visual learners prefer using maps, outlines, diagrams, charts, graphs, designs, and patterns when studying and learning. They are more likely to organize their notes into visual patterns or separate their pages of notes into different sections. Many visual learners also do well by color-coding their notes.

Careers For Visual Learners

Visual learners are often drawn to and do well in STEM fields (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math). Career options include Data Analytics & Visualization, Graphics Design, Photography, Architecture, Construction, Copy Editing, Interior Design, Physics, Advertising, Engineering, and Surgery.

A Note On Visual Learners For Teachers

Sometimes, students who are visual learners might stare out the window or doodle in their notes. If this is the case, let them do it. Locking their eyes constantly on you can be too visually stimulating for these students.

Sometimes, it’s the flower that they draw next to their notes that helps them remember the point by bringing out a visual connection.

It’s also easy for visual learners to get overwhelmed by a lot of visual input. If the classroom setting is chaotic, with many students moving around, it might be too much for these students to take in.

The design of a classroom is very important to visual learners. Clutter or too many posters adorning the walls can easily overwhelm their minds and processing.

Some visual learners may find it helpful to pay careful attention to your movements. They might even remember the silly hand motion you made or how you pointed to a country on the map. Keeping this in mind when delivering your lessons can be very effective.

Lesson Ideas To Help Visual Learners

Draw text and words.

Make it a habit to write new words and add a few quick context clues (e.g., putting the part of speech in brackets or underling the stressed syllable). Pick out a portion of the text with especially vivid imagery and instruct students to draw a picture of what the writing describes. This will help visual learners read and understand the text better.

Visual learners tend to color code things naturally. It can be helpful if you, as a teacher, also color code your notes as you write or post them. You could, for example, designate roles for certain areas of the board and use colors to organize information during the lesson.

Or, for homework or in-class assignments, you could have students annotate/read actively and use different colors for different things you want them to look for. For example, they could highlight dates in blue and names in yellow.

Use charts and graphs

Create charts and graphs to help students visualize information. While math and science subjects typically provide the ideal setting, they can be used in other disciplines as well.

For instance, in a social science class, students could track local election participation rates over ten years and create line graphs to visualize trends. This will give them a deeper understanding of civic involvement dynamics in their community.

Such assignments engage visual learners and allow them to recall information more easily, organize concepts, and articulate their thoughts more easily. Try:

- Venn Diagrams (that represent comparisons and contrasts)

- Timelines (to visually represent a series of events)

- Inverted Triangles (that go from broad topics to more specific ones).

- Story or Essay Planners (that guide students through the steps necessary to complete tasks)

- Charts to list word families – add columns for verbs, adjectives, adverbs, and nouns and fill them as words come up. (e.g., engage, engaging, engagingly, engagement)

Use posters and flashcards

As a project or class assignment, ask students to make posters illustrating key concepts. Students can even present their posters to the class – which would benefit auditory learners. Display these posters on the wall to help drive home important topics.

Flashcards also provide visual cues to young learners and can be used to teach various concepts. To build vocabulary, for example, the word “yummy” may be drawn as swirls of an ice cream cone that helps visual learners remember.

A number of classic games can also be designed using flashcards that help visual learners interact visually and learn better.

Draw reasoning

In math, teach students to draw out their reasoning. For example, instead of verbally explaining how to add 3 and 5, you could create a sketch that depicts two baskets with 3 and 5 apples each. Counting all the apples in your drawing visually demonstrates that 3 plus 5 equals 8, making it easier to understand.

Use gestures

Be aware of your body language when you teach. Including gestures and hand motions when you speak will help visual learners pay attention and make connections.

Auditory Learners

Do you sometimes talk to yourself when thinking hard, studying, or trying to organize something? If that sounds like you, you’re likely an auditory learner.

Auditory learners learn best by carefully hearing and listening. This can include listening to external sources and hearing themselves talk. They will likely volunteer to answer questions and actively participate in classroom discussions.

Auditory learners have a great advantage in the classroom because they are not afraid to speak their minds and easily get answers to their questions. Consequently, they process information very easily, right there in the classroom.

In contrast, reading/writing learners might not even realize they have a question until they’ve had time to go back and process their notes.

For auditory learners, any form of listening or speaking is the most efficient learning method. This can include lectures, audiobooks, discussions, and verbal processing. They are also typically good at storytelling and public speaking.

Many auditory learners prefer studying and working in groups because they prefer to talk through the information, which makes them “social learners,” as per Memletics.

Careers For Auditory Learners

Any job that requires a lot of listening and/or speaking will likely be an excellent fit for an auditory learner. Some career fields to consider include law, psychiatry or therapy, guidance counseling, customer service, sales, speech pathology, journalism, and teaching.

A Note On Auditory Learners For Teachers

Just like visual learners, even auditory learners might stare into space, but for a different reason. Since they process information best by listening, they don’t need to look at notes or PowerPoint very often. While this may seem like they are zoning out or not paying attention, it’s generally not the case.

If you’ve ever caught a student staring off into space and asked them a question, thinking you’ve caught them off guard, only to get the perfect answer, you’ve likely found a very auditory learner.

These students also tend to get chatty during class. This can be great when trying to get a lively class discussion or debate going but not when you need the class to listen intently.

Before this frustrates and angers you, remember that this is how their brain works and learns. As much as you can and as much as is practical based on the subject, try to facilitate discussions and play into this rather than squashing it.

Remember that auditory learners may really struggle with written and visual information.

These are the students who can answer every single question you ask in class and then score just 60% on an exam that tests the same information. If you suspect that a student who bombed a test actually knows much more, give them a chance to answer those questions verbally.

Lesson Ideas To Help Auditory Learners

For obvious reasons, audiobooks are perfect for auditory learners. Give these students the option to listen from an audiobook—this can be effective with both novels and textbooks.

Socratic Seminar

A Socratic seminar is a student-led discussion based on a text in which the teacher asks open-ended questions to begin with. Students listen closely to each other’s comments, think critically for themselves, and articulate their thoughts and responses to others’ thoughts.

They learn to work cooperatively and to question intelligently and civilly. Discussions usually occur in a circle, and the atmosphere is laid-back, encouraging every student to join the conversation.

Auditory learners often lead such discussions. It gives them a chance to shine and be rewarded for talking, which usually gets them in trouble otherwise.

Teacher Kelly Gallagher offers a great handout called Trace the Conversation that can help auditory and visual learners with Socratic seminars. There are many ways to conduct Socratic Seminars; the National Council of Teachers of English has a great explanation .

Speeches, the often hated but necessary school assignment many students dread, are a favorite of auditory learners. When it comes to speeches, auditory learners feel in their element. Speeches can be short and impromptu or long and planned, and they can be on any subject.

Recorded notes

You can either record yourself speaking or permit your students to record lectures so they can listen later. You can also encourage students to record themselves reading their notes.

Text to speech

Students can do this independently, but they might need your prompting or feel better about doing it if you permit them. Document processors like Microsoft Word and Google Docs have text-to-speech and speech-to-text embedded as standard.

Students can, for instance, use speech-to-text to capture their thoughts when writing essays. Text-to-speech can also be beneficial for proofreading and catching errors.

A structured debate is beneficial for auditory learners to get their ideas across. It can be done at all grade levels and in all disciplines. Here is a great resource for some debate ideas and different debate formats for different grade levels.

Reading/Writing Learners

Do you tend to zone out when people talk to you or when you hear a lecture? Would you instead read the transcript or get the information from a book? Then, you’re probably a reading/writing learner. You learn best by reading and writing.

Reading/writing learners often relate to the famous Flannery O’Connor’s quote: “I write because I don’t know what I think until I read what I say.”

For these learners, verbal input can often go into one ear and out from the other without much effect. Seeing notes on the board or a PowerPoint presentation is very important to them, as is taking notes.

These students learn best from books, lists, notes, journals, dictionaries, etc. They can also intuitively help themselves learn by rewriting notes, using flashcards, adding notes to pictures or diagrams, choosing a physical book over an audiobook, and using closed video captions.

Careers For Reading/Writing Learners

Writing is a common and obvious career choice for reading/writing learners, but if this is your learning style, you’re definitely not limited to writing. Editing, journalism, public relations, law, teaching and education, marketing, advertising, researching, translating, and economic advising are all excellent career choices.

A Note On Reading/Writing Learners For Teachers

Reading/writing learners are often your typical “good students.” However, they can really struggle to learn from lectures or completely auditory methods. They may not respond well to class discussions and need more time to process what they hear.

Help them by giving them time to write down their thoughts before asking them to share out loud. This will reduce their stress and allow them to process their thoughts.

As a teacher, you will likely encounter students who need more time to understand a concept, even after you have finished explaining it. These students are most likely reading/writing learners.

Knowing their learning style makes it easier to be more patient and provide them with the necessary support. They sometimes struggle to take notes because they try to write down everything you say. Help them by working with them to pull out the most important parts of your lecture and paraphrase what they hear.

Lesson Ideas To Help Reading/Writing Learners

No matter what the lesson is about, providing handouts highlighting the most important information is one of the best things you can do to help reading/writing learners. It’s also important to give them enough time to write detailed notes.

Essays and reading assignments

These simple assignments work best for reading/writing learners. This is why they often thrive in the traditional classroom setting.

Vocabulary stories

Have students create stories or plays to make their vocabulary words more fun and exciting. This can be done in any subject area that has vocabulary words.

You can give students a topic or let them be creative, but all they have to do is write a story containing x number of vocabulary words. You can also extend this activity to help kinesthetic learners by having students act out their stories for the class.

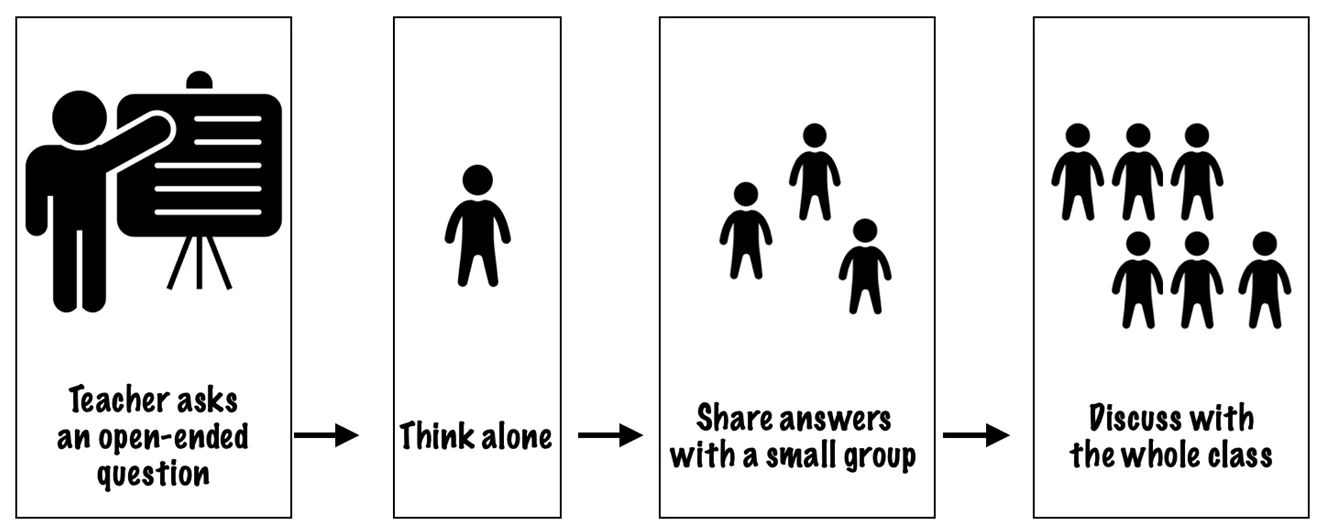

Think, pair, share

Reading/writing learners often struggle with sharing their thoughts out loud. They ace their tests but freeze when you call on them in the class. Think-pair-share can help give them the confidence they need to verbalize their thoughts and is suitable for most age groups in almost any subject area.

First, ask students an open-ended question and give them time to think silently and write their answers. Then, have students pair up in small groups to share their answers. Then, open the discussion to the whole class.

When you ask a question and want students to respond right away, you’ll likely get answers only from the auditory learners—they are the quickest at verbal processing.

With think-pair-share, the reading/writing learners get the time they need to process. In that time, they develop the confidence to construct a verbal response and are very likely to respond.

Kinesthetic Learners

Are you the first to stand up and volunteer to demonstrate an experiment for everyone else? Do you need to change the oil rather than look at a diagram to learn how to do it? If the answer is yes, then you are most likely a kinesthetic learner.

The root word “kines” means motion and a kinesthetic learner learns best by “going through the motion” or doing the task. It’s much easier for them to internalize the information when they are actively moving their body and combining that with what they are learning.

These students tend to shine in demonstrations and experiments. They also learn best from seeing something firsthand, like watching live videos and going on field trips.

Combining a physical motion, such as fidgeting, with a piece of information can help them learn better. They are likelier to use active gesturing and “talk with their hands.”

Careers For Kinesthetic Learners

Any career that allows physical activity and requires movement is right up the alley of a kinesthetic learner. These are the ones who often use the phrase “I don’t sit well.”

Kinesthetic learners typically don’t thrive well at desk jobs. Good career options for such learners include physical or occupational therapy, nursing, dance, theatre, music, automotive technology, welding, on-site engineering jobs, carpentry, agriculture, environmental science, forestry, and marine biology.

A Note On Kinesthetic Learners For Teachers

Just because you see a student fidgeting or being antsy, it doesn’t mean they aren’t paying attention or are bored. Their brain craves that movement to help them make connections.

There’s no need to force such students to sit entirely still as long as they aren’t distracting others in the classroom. Try to connect movement to the concepts you’re teaching as much as possible. Kinesthetic learners need to move, and they can benefit from active brain breaks.

Do your best to keep them active and allow movement in your classroom. If you notice a student with a glazed-over look, take a 30-second break from the lesson and have the entire class stand up, stretch, or do some jumping jacks.

Or you could ask your kinesthetic learner to run a quick errand to the office.

As students, kinesthetic learners often get punished for trying to move and follow their natural learning style. The more you can find ways to reward them for their learning style, the more engaged they will become.

Lesson Ideas To Help Kinesthetic Learners

Labs and experiments.

While labs and experiments are standard in science classes, they can also be successfully implemented in the curriculum of other subjects to benefit kinesthetic learners.

For example, an elementary math lesson could involve measuring each student’s height and creating problems based on the measurements. Geometry, for instance, could be taught using hands-on activities and tangible objects, like clay or building blocks, for better comprehension.

Field trips

With tightening school budgets, it can be hard to plan educational field trips, and that’s understandable. However, field trips need not have to be major events.

An art project, for example, could involve taking students outside and having them draw or photograph what they see. An English lesson could include a nature walk during which students journal or write a story about their little field trip.

Physical props

Use practical and/or memorable props; for example, when teaching a history lesson, dressing in the attire of the era you are teaching about will greatly impact kinesthetic learners. If you’re an anatomy teacher, consider using a model skeleton or demonstrating with your body as a helpful visual aid.

Take a stand

This activity is easy to set up and appeals to both kinesthetic and auditory learners. It requires you to prepare a series of questions that students can agree or disagree with.

For instance, if your students read “To Kill A Mockingbird,” your questions could revolve around racism. (Note: when tackling a sensitive subject such as racism, make sure you know your students and their maturity level)

Have signs on either side of your classroom indicating “agree” and “disagree.” Read through each question and have students move to the side of the room that fits their beliefs. Once there, they can discuss their thoughts with the group that follows their beliefs, and then you can open the discussion to the whole class.

This works well for literature and history lessons. Instead of reading silently, assign students parts and have them act out the story.

Tableaux Vivants

Tableaux Vivants is a time-tested process drama technique that can enhance students’ engagement and comprehension of abstract learning material across the curriculum. It works well in literature and history classrooms and is a great review activity. It is very similar to charades .

It involves breaking students into groups and assigning each group a “scene” – this could be from a work of literature or a scene from history. Each group then works together to create a silent re-enactment consisting of “snapshots” of the scene.

Students pose and pause for 5-10 seconds before moving on to their next pose. Once they have moved through all their poses, the rest of the class guesses what scene they were re-enacting.

Demonstration speeches

Einstein once said: “If you can’t explain it simply, you don’t understand it well enough.” Demonstration speeches allow students to explain something they understand well to their peers.

Ask your students to pick a topic, such as how to make a peanut butter and jelly sandwich. Ask them to give a speech explaining the process while simultaneously demonstrating it.

The demonstration part appeals most to kinesthetic learners. Since students can choose their topic, it also appeals to all other learners, creating an engaging learning experience.

Logical Learners

If a child is good with numbers and asks many questions, they might be a logical learner. A logical learner has a core need to understand what is being learned. For them, simply memorizing facts is not enough. They thrive on orderly and sequential processes.

Individuals who excel at math and possess strong logical reasoning skills are usually logical learners. They notice patterns quickly and have a keen ability to link information that would seem unrelated to others. Logical learners retain details better by drawing connections after organizing an assortment of information.

As a logical learner, you can maximize your ability to learn by seeking to understand the meaning and reasoning behind the subject you’re studying. Avoid rote memorization.

Explore the links between related subject matter and ensure you understand the details. Use ‘systems thinking’ to better understand the relationship between various parts of a system. This will not only help you understand the bigger picture but also help you understand why each component is important.

Social Learners

Social learners have excellent written and verbal communication skills. They are at ease speaking to others and adept at comprehending other people’s perspectives. For this reason, people frequently seek counsel from them.

Social learners learn best when working with groups and take opportunities to meet individually with teachers.

If you like bouncing ideas off others, prefer working through issues as a group, and thoroughly enjoy working with others, you may be a social learner. Seek opportunities to study with others. If your class doesn’t have formal groups, form one.

Solitary Learners

Solitary learners prefer working by themselves in private settings. They avoid relying on others for help when solving problems or studying and frequently analyze their learning preferences and methods.

Solitary learners tend to waste a lot of time on a complex problem before seeking assistance. If you are a solitary learner, you must consciously recognize this limitation and try to seek help more often/sooner when stuck.

Generally, solitary learning can be a very effective learning style for students.

Tips to Simultaneously Help Learners of All Types

Lessons tailored to suit multiple learning styles are often the most effective, as they reach and appeal to most students. Another reason they are best suited is because most people have a combination of learning styles.

The activities discussed in this article provide ample opportunities for all types of learners to benefit. As a teacher, if you try to be creative, you can make little tweaks in almost every lesson to reach different learning styles.

Following are some ideas and ways by which to reach all four VARK learning styles:

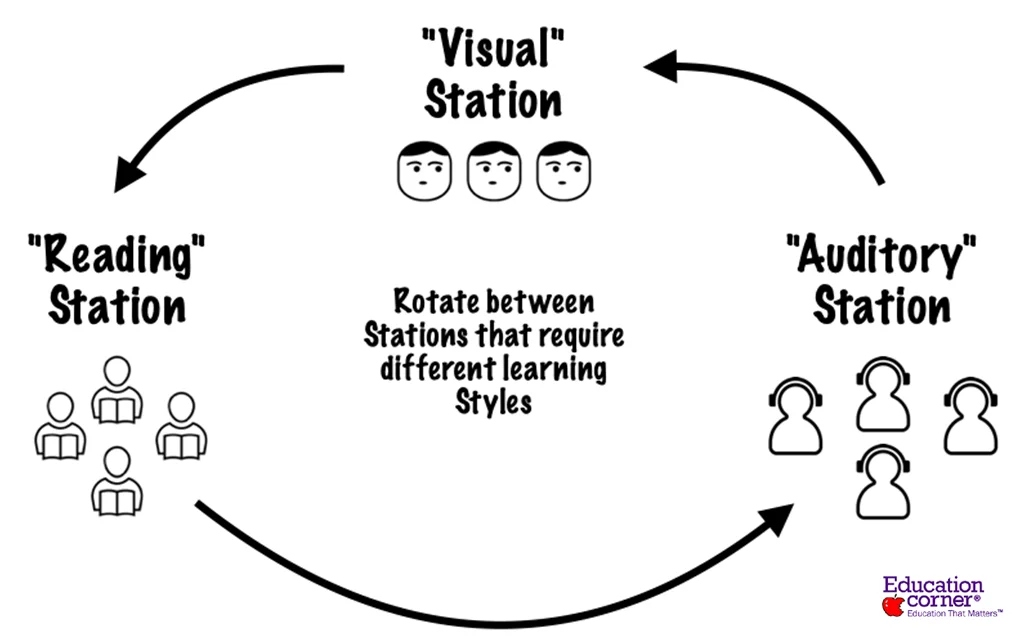

Split your space into multiple stations (or centers) spread throughout the classroom. Break your students into groups so there is a group at every station.

Then, assign activities for each station that focus on a learning style. Have the students rotate with their groups from one station to another.

While the obvious benefit of rotation is that it ensures the activities cover each type of learner’s needs, there is more to it.

Even if you don’t have a center that caters to kinesthetic learners, the simple act of getting up and moving around different stations in the classroom helps them. The same goes for auditory learners; being in small groups and rotating throughout the room encourages discussion.

Give options

Irrespective of what subjects you teach your students, give them options as far as possible. For instance, instead of assigning an essay at the end of a unit, assign a project that can be completed with multiple activities.

Don’t mention which choices align with which learning style—let the students decide. Here is an example of 4 different options for a homework project:

- Write an essay (appeals to reading/writing learners)

- Record a podcast or TED talk (appeals to auditory learners)

- Film a video (appeals to kinesthetic learners)

- Create a poster or multimedia project (appeals to visual learners)

Quite often, students will naturally gravitate toward the option that best suits their learning style.

Allow students to use headphones when working independently in class. This helps cut out distractions for most learning types. Particularly for auditory learners, it can help make connections between what they hear and what they’re learning, which can be very helpful for them when they need to work silently.

Technology has made great strides and deep inroads into education. Several apps and websites can help students in various ways. Here is a list of apps for elementary math that could appeal to all four learning styles.

Games that include pictures and sound can help visual and auditory learners. Reading explanations and lessons on apps helps reading/writing learners. Physically manipulating and touching a device helps kinesthetic learners.

A quick online search will reveal several beneficial websites and apps for almost any discipline.

Final Words

There is no right or wrong when it comes to learning styles; they are simply names and categories assigned to how people’s brains process information.

It is generally easier for those with a dominant reading/writing style to succeed in a traditional academic setting, thus securing the “good student” label. However, education has come a long way, and schools and teachers can cater to various styles.

As a teacher, it’s important to remember that every student is unique. Even two visual learners might differ significantly in terms of what works for them. The best approach is to learn about and understand each student’s unique educational requirements.

After all, students are human beings with unique needs and feelings; teachers who remember this can approach them empathetically.

If you are a student interested in knowing about your learning style, you can begin by taking the VARK questionnaire . Having your students take the questionnaire is a good idea if you’re a teacher. Not only will you discover your student’s learning styles, but they will also be able to identify which techniques work best for them.

Remember, learning style is only a partial explanation of a student’s preferred way of learning. It is never the complete picture. These styles change over time, and every student can have differing degrees of inclination toward a given style.

However, regardless of your position in education, recognizing both your own learning styles and those of others around you can be highly beneficial.

Similar Posts:

- 35 of the BEST Educational Apps for Teachers (Updated 2024)

- 20 Huge Benefits of Using Technology in the Classroom

- 15 Learning Theories in Education (A Complete Summary)

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name and email in this browser for the next time I comment.

Home — Essay Samples — Education — Learning Styles — Importance Of Learning Styles In Teaching

Importance of Learning Styles in Teaching

- Categories: Learning Styles Teaching

About this sample

Words: 775 |

Published: Mar 14, 2024

Words: 775 | Pages: 2 | 4 min read

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Prof. Kifaru

Verified writer

- Expert in: Education

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

1 pages / 431 words

4 pages / 1922 words

3 pages / 1435 words

3 pages / 1538 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Learning Styles

Evaluation essays are a type of academic writing that assesses the quality, value, or effectiveness of a particular subject or topic. The purpose of this essay is to evaluate a chosen topic based on a set of criteria, and [...]

Fleming, Neil. 'VARK: A Guide to Learning Styles.' Accessed from: 1998.

The concept of learning styles has been a topic of interest for educators and psychologists for decades. Understanding how individuals learn best is crucial for effective teaching and learning. In this essay, we will explore the [...]

Visual learners are individuals who learn best through seeing and observing information in a visual format. This includes images, graphs, charts, diagrams, and other visual aids. Visual learners make up a significant portion of [...]

Intelligence is usually defined as our intellectual potential; something we are born with, something which will be measured, and a capacity that is strenuous to alter. Although recently other views have emanated.One of [...]

Language learning strategies are methods that facilitate a language learning task. Strategies are goal-driven procedures and most often conscious techniques. Learning strategies usually used especially in the beginning of a new [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

- Grades 6-12

- School Leaders

Don't Miss the Grand Prize: A $2,500 Office Depot/OfficeMax Card!

What Are Learning Styles, and How Should Teachers Use Them?

Encourage every student to explore material in a variety of ways.

Teachers are often told to make sure their lessons include a variety of activities to cover all learning styles. But what exactly does that mean?

FAQ: What Are Learning Styles?

Imagine you’re teaching a lesson on the presidency of John Adams. You’ll be giving a quiz on Friday, and you ask your students how they’ll be preparing. Some might say they’ll reread the text, then write down the answers to the review questions you’ve given them. Others might plan to watch a video on John Adams’ life, then talk over what they learned with a study partner. Another could plan to take the timeline handout you provided, cut it up into sections, and practice putting those sections in the proper order.

Each of these students is using different ways of learning in an effort to retain and understand the same information. Some like written words, some prefer to hear it and talk about it. Others need to do something with their hands, or see images and diagrams. These are all various learning styles.

What is VARK?

Source: Nnenna Walters

In the mid-1980s, teacher Neil Fleming introduced the VARK model of learning styles. He theorized that students learned in these four general ways, known as styles or modalities:

- Visual: Seeing images, diagrams, videos, etc.

- Auditory: Hearing lectures and having discussions

- Read/Write: Reading the written word and writing things down

- Kinesthetic: Movement and hands-on activities

Fleming developed a questionnaire ( try a version of it here ) that a student could take to see which learning styles they preferred. The results indicate how their learning preferences spread across the spectrum.

One important detail Fleming noted was that just because you prefer or are good at a certain learning activity, that doesn’t mean it’s actually the style that helps you learn the most. “It is possible to like something (preference) and not be good at it (skill or ability). Similarly it is possible to be very skilled at using strategies aligned with one of the VARK modalities but not use that for learning,” he explained . “As an example, a learner who was very skilled at freehand drawing did not use it for her learning and did not enjoy doing it.”

Are learning styles a proven theory?

There’s a lot of argument over the validity of learning styles. Some studies claim to have debunked the theory entirely , stating that everyone uses each of the various styles at one time or another. Critics worry that pigeonholing a student as an “auditory learner” or a “visual learner” might cause them to limit the ways they approach new material.

That said, learning styles are accepted and used in most education programs. Fleming himself published an article in 2012 defending his theory , explaining that it has been misunderstood and misused. His intention was never to limit the ways in which individual students were encouraged to learn. Rather, he wanted teachers to better understand all the different ways they could reach their students.

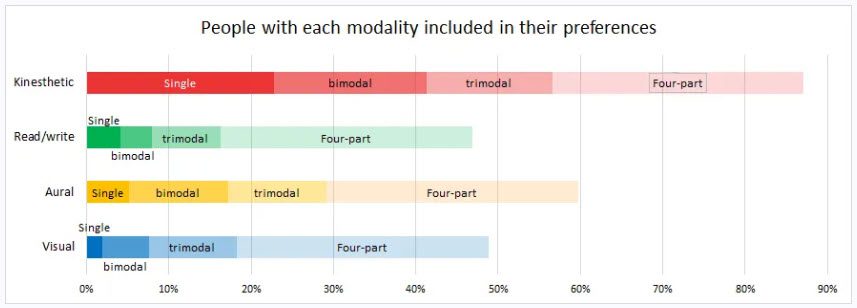

Does a person have just one learning style?

Source: VARK Research

Absolutely not, says Fleming. “Because learners have different preferences between the four modes, it is unlikely that any particular mode will be dominant. That is why multimodality is the most common profile for two-thirds of learners.”

In other words, while some people lean strongly toward one learning type (modality), most are more evenly spread across the spectrum. The way they learn best will depend on the material and situation. The key isn’t to find a single best way for a student to learn. It’s to discover all the ways all students can learn.

How should teachers use learning styles in the classroom?