Home — Essay Samples — Psychology — The Bystander Effect — Bystander Effect: Human Behavior in Social Situations

Bystander Effect: Human Behavior in Social Situations

- Categories: Human Behavior The Bystander Effect

About this sample

Words: 636 |

Published: Sep 7, 2023

Words: 636 | Page: 1 | 4 min read

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Verified writer

- Expert in: Psychology

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

1 pages / 570 words

1 pages / 616 words

1 pages / 546 words

4 pages / 1718 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on The Bystander Effect

Another form of conditioning is called operant conditioning. This type of study refers to a method of learning that occurs using rewards and punishments to adjust behaviors. Basically, through operant conditioning, an [...]

In Abraham Maslow’s revolutionary paper that was published in 1943, he stated that there was an ascending hierarchy of needs for a person to attain which was key to our understanding of human motivation. Studying only [...]

Constructivism is one of the more modern international theory that takes issue with the realist and liberal theory of anarchy in the international system. It focuses on the ideas of norms, the development of structures [...]

The appropriate case in this analysis will be the early years of actress Emma Stone. Stone is a very famous actress, and has multiple biographies describing her childhood life online. The details of her childhood will be [...]

Educators and extra specialists basically should have learning and comprehension into youngsters' abilities, and respect for together their forces and their human rights to developing autonomy and independence. Kids can [...]

Each day, people are conditioned without even realizing it. This may include being productive at work to avoid losing a job or associating a gas station with anger because it is right next to that one light that never turns [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

How Psychology Explains the Bystander Effect

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Amy Morin, LCSW, is a psychotherapist and international bestselling author. Her books, including "13 Things Mentally Strong People Don't Do," have been translated into more than 40 languages. Her TEDx talk, "The Secret of Becoming Mentally Strong," is one of the most viewed talks of all time.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/VW-MIND-Amy-2b338105f1ee493f94d7e333e410fa76.jpg)

How the Bystander Effect Works

- Real-Life Example

- Explanations

What Is the Meaning of Bystander Effect?

The bystander effect, also known as bystander apathy, refers to a phenomenon in which the greater the number of people there are present, the less likely people are to help a person in distress.

If you witnessed an emergency happening right before your eyes, you would certainly take some sort of action to help the person in trouble, right? While we might all like to believe that this is true, psychologists suggest that whether or not you intervene might depend upon the number of other witnesses present.

When an emergency situation occurs, the bystander effects holds that observers are more likely to take action if there are few or no other witnesses.

Being part of a large crowd makes it so no single person has to take responsibility for an action (or inaction).

In a series of classic studies, researchers Bibb Latané and John Darley found that the amount of time it takes the participant to take action and seek help varies depending on how many other observers are in the room. In one experiment , subjects were placed in one of three treatment conditions: alone in a room, with two other participants, or with two confederates who pretended to be normal participants.

As the participants sat filling out questionnaires, smoke began to fill the room. When participants were alone, 75% reported the smoke to the experimenters. In contrast, just 38% of participants in a room with two other people reported the smoke. In the final group, the two confederates in the experiment noted the smoke and then ignored it, which resulted in only 10% of the participants reporting the smoke.

Additional experiments by Latané and Rodin (1969) found that 70% of people would help a woman in distress when they were the only witness. But only about 40% offered assistance when other people were also present.

What Is a Real-Life Example of the Bystander Effect?

The most frequently cited example of the bystander effect in introductory psychology textbooks is the brutal murder of a young woman named Catherine "Kitty" Genovese. On Friday, March 13, 1964, 28-year-old Genovese was returning home from work. As she approached her apartment entrance, she was attacked and stabbed by a man later identified as Winston Moseley.

Despite Genovese’s repeated calls for help, none of the dozen or so people in the nearby apartment building who heard her cries called the police to report the incident. The attack first began at 3:20 AM, but it was not until 3:50 AM that someone first contacted police.

An initial article in the New York Times sensationalized the case and reported a number of factual inaccuracies. An article in the September 2007 issue of American Psychologist concluded that the story is largely misrepresented mostly due to the inaccuracies repeatedly published in newspaper articles and psychology textbooks.

While Genovese's case has been subject to numerous misrepresentations and inaccuracies, there have been numerous other cases reported in recent years. The bystander effect can clearly have a powerful impact on social behavior, but why exactly does it happen? Why don't we help when we are part of a crowd?

Why Does It Happen?

There are two major factors that contribute to the bystander effect. First, the presence of other people creates a diffusion of responsibility .

Because there are other observers, individuals do not feel as much pressure to take action. The responsibility to act is thought to be shared among all of those present.

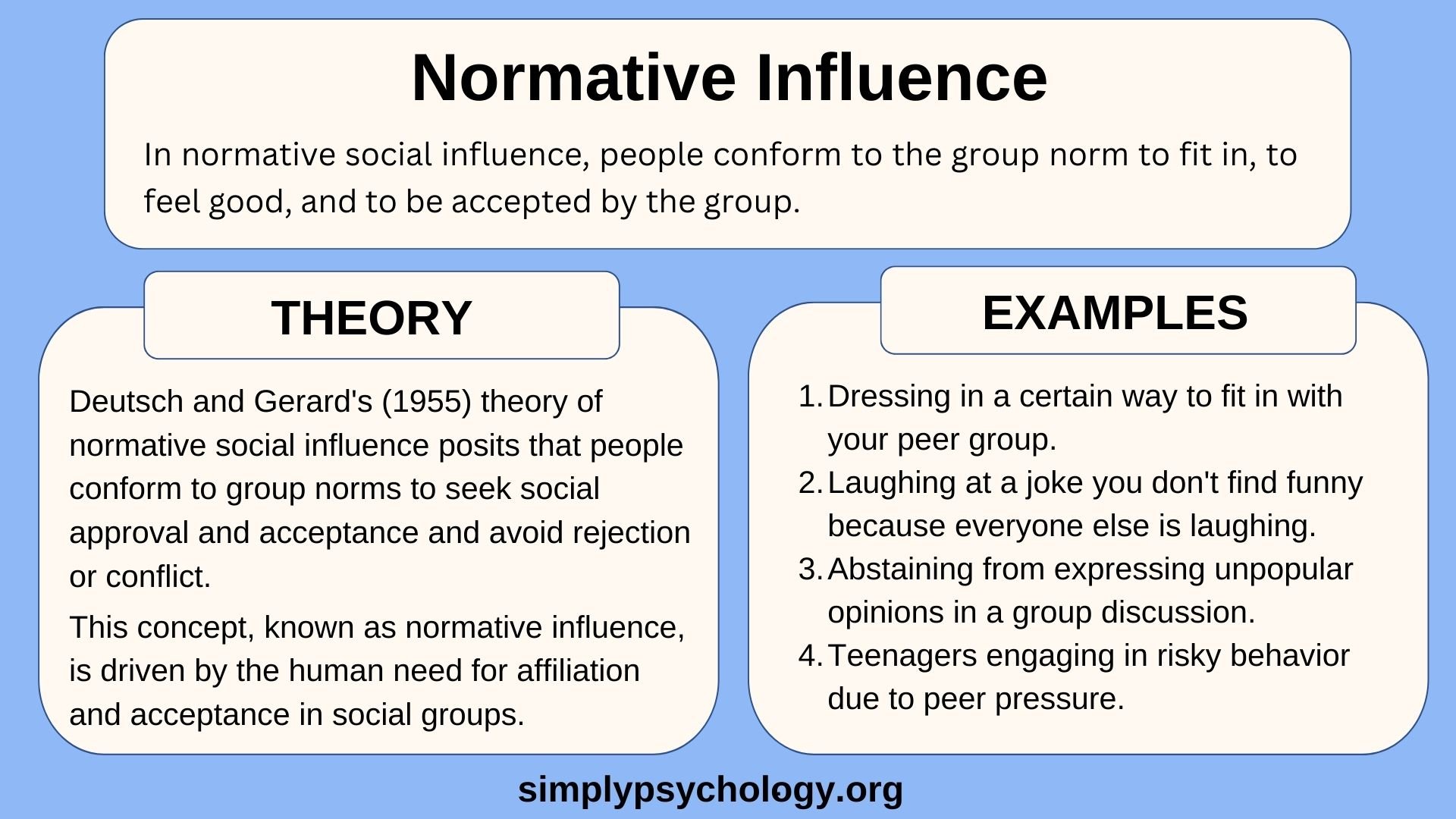

The second reason is the need to behave in correct and socially acceptable ways. When other observers fail to react, individuals often take this as a signal that a response is not needed or not appropriate.

Researchers have found that onlookers are less likely to intervene if the situation is ambiguous. In the case of Kitty Genovese, many of the 38 witnesses reported that they believed that they were witnessing a "lover's quarrel," and did not realize that the young woman was actually being murdered.

A crisis is often chaotic and the situation is not always crystal clear. Onlookers might wonder exactly what is happening. During such moments, people often look to others in the group to determine what is appropriate. When they see that no one else is reacting, it sends a signal that perhaps no action is needed.

Preventing the Bystander Effect

What can you do to overcome the bystander effect ? Some psychologists suggest that simply being aware of this tendency is perhaps the greatest way to break the cycle. When faced with a situation that requires action, understand how the bystander effect might be holding you back and consciously take steps to overcome it. However, this does not mean you should place yourself in danger.

But what if you are the person in need of assistance? How can you inspire people to lend a hand? One often recommended tactic is to single out one person from the crowd. Make eye contact and ask that individual specifically for help. By personalizing and individualizing your request, it becomes much harder for people to turn you down.

Manning R, Levine M, Collins A. The Kitty Genovese murder and the social psychology of helping: the parable of the 38 witnesses . Am Psychol. 2007;62(6):555-62. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.62.6.555

Darley JM, Latané B. Bystander “apathy.” American Scientist. 1969;57:244-268.

Latané B, Darley JM. The Unresponsive Bystander: Why Doesn’t He Help? Prentice Hall, 1970.

Solomon LZ, Solomon H, Stone R. Helping as a function of number of bystanders and ambiguity of emergency . Pers Soc Psychol Bull . 1978;4(2):318-321. doi:10.1177/014616727800400231

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

Bystander Effect and How to Understand It Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Two Approaches Psychologists Use to Understand Bystander Behavior

Bystander effect, reference list.

A bystander can be defined as any person present when an event occurs, but they are not involved. Bystander behaviour is the way people behave in response to a particular event. Various psychologists have done many research methodologies to apprehend the motions behind bystander behaviour. The two research strategies examined during this essay are the discourse analysis method which employs qualitative research the experimental method, which utilizes quantitative research. This approach will be founded on two cases, the first being the killing of Catherine Genovese in 1964 and the second of James Bulger in 1993. Both research methodologies were invented following incidents whereby bystanders were present at crimes and failed to intercede. They will investigate the meaning of the bystander effect from a more profound perspective by considering the case of the murder of Catherine and later an experiment to investigate this incident.

The bystander effect can be understood from the perspective that an individual is slightly likely to intercede in a problematic situation when other people are present. A person who witnesses an emergency event alone has a higher probability of intervening than someone who sees a similar event alone (Byford, 2014, p. 232), as demonstrated in the bystander effect module video (The Open University, 2020b). An actor in distress is lying on the street where people are passing. Many people did not bother to investigate what was happening to the person despite seeing him. A lady walked by and decided to see whether someone would notice her intentions to offer help. After witnessing another member trying to help, she changed her mind and joined him. Two different approaches discussed below were taken to investigate the bystander effect.

Catherine Genovese, a woman, living in New York, was brutally attacked when returning home from work. The incident happened on the streets where she resided near her house. The attack prevailed for almost thirty minutes, whereby she was stabbed many times before losing her life (Byford, 2014, p. 225). After a police investigation, it was discovered that almost 38 bystanders were present during the attack. Some just viewed in the comfort of their homes through windows, and others reported hearing Catherine scream for help (Byford, 2014, p. 225). Even though there were 38 witnesses, only one of them attempted to interfere by yelling, ‘leave the girl alone’ (Byford, 2014, p. 225). When the police were informed, Catherine Genovese had already died. If emergency services had been offered to her some few minutes earlier, she would have survived. This led Latané and Darley to develop a model of bystander behaviour. It applies the five-stage model to indicate the outcomes of a series of bystander intervention decisions. These phases advance from whether the observer witnesses the happening to resolve whether their intervention would put them at risk.

Psychologists Latané and John Darley wanted to investigate why 38 witnesses failed to intercede following the murder of Catherine Genovese. According to their arguments, the neighbours lacked incuriosity (Byford, 2014, p.228). Furthermore, Latané and Darley came with opinions that the failure of intervention from the 38 witnesses did not come from their low interest but rather examined reasons why people respond to emergencies and fail in some scenarios (Byford, 2014, p. 228). Latané and Darley carried out controlled experiments to determine the validity of these assumptions. The experiment was done in a laboratory with participants under control. The investigation was called ‘lady in distress,’ the activities involved included filling out questionnaires (Byford, 2014, p. 229). The participants would be invited by a lady into a room either in pairs or individually to complete a questionnaire. In the process of filling out the questionnaire, the lady would leave the room, leaving a recorded sound of a loud crash and a woman’s scream. This would stimulate a scenario where the lady had climbed on a chair, fallen off, and injured herself.

The main aim of the experiment was to examine the participants’ behaviour. The study was repeated over a hundred times to investigate whether people were willing to help the woman when they were alone or in with the company of another person (Byford, 2014, p. 230). The research findings, it indicated that 70% of individuals, when alone, offered to help the lady in distress, and while in pairs, only 40% intervened. From the results, cases of being with an unknown bystander reduce the chances of help by almost half (Byford, 2014, p. 232). Another third condition was passive confederate, investigated by placing 15 participants in a room, and 14 were told to ignore the lady. It indicated that one person would be influenced by the 14 others to help, accounting for 10% of intervened. Through this, Latané and Darley presented the ‘bystander effect’ (Byford, 2014, p.232). The results would be compared to the audio discussion with Jovan Byford and Catriona Harvard (The Open University, 2020a). Latané and Darley concluded that during an emergency, the presence of others could limit the chances of intervention.

If the amount of people is higher, the response is slower, and if the people present are few or none, the answer is quick. When the experiment conducted is linked to the case of Catherine Genovese, it can be seen that the thirty-eight bystanders present reduced attempts to rescue her. Another incident is the murder of the three-year-old James Bulger in 1993. Robert Venables and Jon Thompson, both ten years old, abducted James Bulger from a shopping centre in Liverpool. They were in a company with James for almost two hours and then decided to take him to an isolated railway track and kill him (Byford, 2014, p. 226). Thirty-eight witnesses were presented in court, stating that they had seen the three boys walk together. Others said that they observed James and concluded that he felt uncomfortable. Surprisingly, none of the witnesses intervened to question why James was in that state. From the principle of the ‘bystander effect’ by Latané and Darley, social psychologist mark Levine argued that there was a probability that the bystanders were alone.

Levine decided to conduct his own research into bystander behaviour using a qualitative discourse analysis approach. Thirty-eight witness testimonies were examined from the trial of Venables and Thompson, and studies were done as to why each witness did not intervene and prevent the situation from happening (Byford, 2014, p. 235). Levine’s research implicated great interest in investigating real-life situations of bystanders. This was done by looking into accounts, explanations, and interactions. Levine, through his study, indicated that lack of intervention would not be associated with the number of bystanders present. He instead examined the relationship existing between the three boys.

Lavine concluded that the bystanders thought that one of the boys was James Bulger’s older brother, and maybe he was sad due to family relations which might have been poor. By the fact that they were together, nobody would think that there were some bad intentions behind this scene. He found that other bystanders were alone when they encountered James and the other boys in his company. Correspondingly, some individuals were just working on the streets with typical day to day routines. They could therefore be concentrating on their issues rather than watching people around. He thus reasoned that there was something else that made the bystanders unreactive to the situation. He concluded that family matters are private, and therefore, the bystanders found it difficult to question them (Byford, 2014, p. 236). The guidelines of life on the streets followed a specific norm.

Despite both methods using different approaches, some aspects are shared in common. For instance, both processes try to come up with an explanation behind bystander behaviour and a practical reason as to why bystanders behave differently when faced with emergency events. Different types of data in both approaches are used to examine bystander behaviour. Latané and Darley used quantitative data, which was seen in his experiment involving counting people and analyzing data (Byford, 2014, p. 231). On the other hand, Levine’s method utilized qualitative data in his study. This further supports the difference that latané and Darley’s study was based on an experiment that was controlled artificial and artificial and not based on real life.

Levine’s study used real-life situations, making his study more appropriate. This is because it had not been manipulated by experiments in any manner. The two methods do not address the same question, even though they explain bystander behaviour (The Open University, 2020b). Latané and Darley’s main aim in the experiment was to explain the failure of the 38 bystanders in the Catherine Genovese case indicating a bystander effect principle. Levine’s study used a different topic, and he argued against the bystander effect by saying that it was irrelevant when applied to the James Bulger case.

The significant difference is that both studies used different data and methodologies, therefore creating their own unique disadvantages and advantages. For example, experiments manipulate and indicate a false impression that is not real life. Discourse analysis examines real-life experiences of people. The life testimonials can be narrated for a detailed explanation of why certain behaviours are possessed by people. Despite of the disclosure analysis being based on real life, it could create some disadvantages. It invades the personality of a person under study, which is against human rights (The Open University, 2020a). Giving out information about other people’s economic, social or political matters can lower their self-esteem.

Experiments are standard in psychology since they can be controlled to allow examination of some unknown features, but they have disadvantages. They create false situations in everyday life like the ‘lady in distress. In conclusion, few differences were seen in the comparison and contrast made in the two studies. The two approaches were different in terms of data where one applied the qualitative and the other method used the quantitative. The remarkable difference spotted is that one course manipulated an experiment to come up with the bystander effect, and the other one applied a real-life situation. However, the investigation created a false implication since it was manipulated for illustrations. Disclosure analysis was seen to be the most effective as it illustrated a real-life situation. This is because it used testimonials made by the bystanders and accurate transcripts to explain the bystander effect.

Byford, J. (2014) ‘Living together, living apart: the social life of the neighbourhood’, in Clarke, J. and Woodward, K. (eds.) Understanding Social Lives, Part 2 , Milton Keynes.

The Open University (2020a) ‘Bystander behaviour discussion’ [Audio], DD102 Introducing the Social Sciences . Web.

The Open University (2020b) ‘The bystander effect’ [Video] DD102 Introducing the Social Sciences . Web.

- "Whitey Bulger" by Kevin Cullen and Shelley Murphy

- Bystander Effect: The Stanford Experiment

- Moral Panic: James Bulger and Mary Bell Cases

- Future Ways for Helping People With Psychology

- The ABC Model of Crisis Intervention vs. Long-Term Therapy

- Rorschach Test and Its Specific Features

- Defining and Measuring of Human Intelligence

- The Narrative Therapy Analysis

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2023, March 18). Bystander Effect and How to Understand It. https://ivypanda.com/essays/bystander-effect-and-how-to-understand-it/

"Bystander Effect and How to Understand It." IvyPanda , 18 Mar. 2023, ivypanda.com/essays/bystander-effect-and-how-to-understand-it/.

IvyPanda . (2023) 'Bystander Effect and How to Understand It'. 18 March.

IvyPanda . 2023. "Bystander Effect and How to Understand It." March 18, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/bystander-effect-and-how-to-understand-it/.

1. IvyPanda . "Bystander Effect and How to Understand It." March 18, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/bystander-effect-and-how-to-understand-it/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Bystander Effect and How to Understand It." March 18, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/bystander-effect-and-how-to-understand-it/.

Bystander Effect In Psychology

Udochi Emeghara

Research Assistant at Harvard University

B.A., Neuroscience, Harvard University

Udochi Emeghara is a research assistant at the Harvard University Stress and Development Lab.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

Take-home Messages

- The bystander effect is a social psychological phenomenon where individuals are less likely to help a victim when others are present. The greater the number of bystanders, the less likely any one of them is to help.

- Factors include diffusion of responsibility and the need to behave in correct and socially acceptable ways.

- The most frequently cited real-life example of the bystander effect regards a young woman called Kitty Genovese , who was murdered in Queens, New York, in 1964 while several of her neighbors looked on. No one intervened until it was too late.

- Notice the event (or in a hurry and not notice).

- Interpret the situation as an emergency (or assume that as others are not acting, it is not an emergency).

- Assume responsibility (or assume that others will do this).

- Know what to do (or not have the skills necessary to help).

- Decide to help (or worry about danger, legislation, embarrassment, etc.).

- Latané and Darley (1970) identified three different psychological processes that might prevent a bystander from helping a person in distress: (i) diffusion of responsibility; (ii) evaluation apprehension (fear of being publically judged); and (iii) pluralistic ignorance (the tendency to rely on the overt reactions of others when defining an ambiguous situation).

- Diffusion of responsibility refers to the tendency to subjectively divide personal responsibility to help by the number of bystanders present. Bystanders are less likely to intervene in emergency situations as the size of the group increases, and they feel less personal responsibility.

What is the bystander effect?

The term bystander effect refers to the tendency for people to be inactive in high-danger situations due to the presence of other bystanders (Darley & Latané, 1968; Latané & Darley, 1968, 1970; Latané & Nida, 1981).

Thus, people tend to help more when alone than in a group.

The implications of this theory have been widely studied by a variety of researchers, but initial interest in this phenomenon arose after the brutal murder of Catherine “Kitty” Genovese in 1964.

Through a series of experiments beginning in the 1960s and 1970s, the bystander effect phenomenon has become more widely understood.

Kitty Genovese

On the morning of March 13, 1964, Kitty Genovese returned to her apartment complex, at 3 am, after finishing her shift at a local bar.

After parking her car in a lot adjacent to her apartment building, she began walking a short distance to the entrance, which was located at the back of the building.

As she walked, she noticed a figure at the far end of the lot. She shifted directions and headed towards a different street, but the man followed and seized her.

As she yelled, neighbors from the apartment building went to the window and watched as he stabbed her. A man from the apartment building yelled down, “Let that girl alone!” (New York Times, 1964).

Following this, the assailant appeared to have left, but once the lights from the apartments turned off, the perpetrator returned and stabbed Kitty Genovese again. Once again, the lights came on, and the windows opened, driving the assaulter away from the scene.

Unfortunately, the assailant returned and stabbed Catherine Genovese for the final time. The first call to the police came in at 3:50 am, and the police arrived in two minutes.

When the neighbors were asked why they did not intervene or call the police earlier, some answers were “I didn”t want to get involved”; “Frankly, we were afraid”; “I was tired. I went back to bed.” (New York Times, 1964).

After this initial report, the case was launched to nationwide attention, with various leaders commenting on the apparent “moral decay” of the country.

In response to these claims, Darley and Latané set out to find an alternative explanation.

Decision Model of Helping

Latané & Darley (1970) formulated a five-stage model to explain why bystanders in emergencies sometimes do and sometimes do not offer help.

At each stage in the model, the answer ‘No’ results in no help being given, while the answer ‘yes’ leads the individual closer to offering help.

However, they argued that helping responses may be inhibited at any stage of the process. For example, the bystander may not notice the situation or the situation may be ambiguous and not readily interpretable as an emergency.

The five stages are:

- The bystander must notice that something is amiss.

- The bystander must define that situation as an emergency.

- The bystander must assess how personally responsible they feel.

- The bystander must decide how best to offer assistance.

- The bystander must act on that decision.

Figure 1. Decision Model of Helping by Latané and Darley (1970).

Why does the bystander effect occur?

Latane´ and Darley (1970) identified three different psychological processes that might interfere with the completion of this sequence.

Diffusion of Responsibility

The first process is a diffusion of responsibility, which refers to the tendency to subjectively divide the personal responsibility to help by the number of bystanders.

Diffusion of responsibility occurs when a duty or task is shared between a group of people instead of only one person.

Whenever there is an emergency situation in which more than one person is present, there is a diffusion of responsibility. There are three ideas that categorize this phenomenon:

- The moral obligation to help does not fall only on one person but the whole group that is witnessing the emergency.

- The blame for not helping can be shared instead of resting on only one person.

- The belief that another bystander in the group will offer help.

Darley and Latané (1968) tested this hypothesis by engineering an emergency situation and measuring how long it took for participants to get help.

College students were ushered into a solitary room under the impression that a conversation centered around learning in a “high-stress, high urban environment” would ensue.

This discussion occurred with “other participants” that were in their own room as well (the other participants were just records playing). Each participant would speak one at a time into a microphone.

After a round of discussion, one of the participants would have a “seizure” in the middle of the discussion; the amount of time that it took the college student to obtain help from the research assistant that was outside of the room was measured. If the student did not get help after six minutes, the experiment was cut off.

Darley and Latané (1968) believed that the more “people” there were in the discussion, the longer it would take subjects to get help.

The results were in line with that hypothesis. The smaller the group, the more likely the “victim” was to receive timely help.

Still, those who did not get help showed signs of nervousness and concern for the victim. The researchers believed that the signs of nervousness highlight that the college student participants were most likely still deciding the best course of action; this contrasts with the leaders of the time who believed inaction was due to indifference.

This experiment showcased the effect of diffusion of responsibility on the bystander effect.

Evaluation Apprehension

The second process is evaluation apprehension, which refers to the fear of being judged by others when acting publicly.

People may also experience evaluation apprehension and fear of losing face in front of other bystanders.

Individuals may feel afraid of being superseded by a superior helper, offering unwanted assistance, or facing the legal consequences of offering inferior and possibly dangerous assistance.

Individuals may decide not to intervene in critical situations if they are afraid of being superseded by a superior helper, offering unwanted assistance, or facing the legal consequences of offering inferior and possibly dangerous assistance.

Pluralistic Ignorance

The third process is pluralistic ignorance, which results from the tendency to rely on the overt reactions of others when defining an ambiguous situation.

Pluralistic ignorance occurs when a person disagrees with a certain type of thinking but believes that everyone else adheres to it and, as a result, follows that line of thinking even though no one believes it.

Deborah A. Prentice cites an example of this. Despite being in a difficult class, students may not raise their hands in response to the lecturer asking for questions.

This is often due to the belief that everyone else understands the material, so for fear of looking inadequate, no one asks clarifying questions.

It is this type of thinking that explains the effect of pluralistic ignorance on the bystander effect. The overarching idea is uncertainty and perception. What separates pluralistic ignorance is the ambiguousness that can define a situation.

If the situation is clear (for the classroom example: someone stating they do not understand), pluralistic ignorance would not apply (since the person knows that someone else agrees with their thinking).

It is the ambiguity and uncertainty which leads to incorrect perceptions that categorize pluralistic ignorance.

Rendsvig (2014) proposes an eleven-step process to explain this phenomenon.

These steps follow the perspective of a bystander (who will be called Bystander A) amidst a group of other bystanders in an emergency situation.

- Bystander A is present in a specific place. Nothing has happened.

- A situation occurs that is ambiguous in nature (it is not certain what has occurred or what the ramifications of the event are), and Bystander A notices it.

- Bystander A believes that this is an emergency situation but is unaware of how the rest of the bystanders perceive the situation.

- A course of action is taken. This could be a few things like charging into the situation or calling the police, but in pluralistic ignorance, Bystander A chooses to understand more about the situation by looking around and taking in the reactions of others.

- As observation takes place, Bystander A is not aware that the other bystanders may be doing the same thing. Thus, when surveying others’ reactions, Bystander A “misperceives” the other bystanders” observation of the situation as purposeful inaction.

- As Bystander A notes the reaction of the others, Bystander A puts the reaction of the other bystanders in context.

- Bystander A then believes that the inaction of others is due to their belief that an emergency situation is not occurring.

- Thus, Bystander A believes that there is an accident but also believes that others do not perceive the situation as an emergency. Bystander A then changes their initial belief.

- Bystander A now believes that there is no emergency.

- Bystander A has another opportunity to help.

- Bystander A chooses not to help because of the belief that there is no emergency.

Pluralistic ignorance operates under the assumption that all the other bystanders are also going through these eleven steps.

Thus, they all choose not to help due to the misperception of others’ reactions to the same situation.

Other Explanations

While these three are the most widely known explanations, there are other theories that could also play a role. One example is a confusion of responsibility.

Confusion of responsibility occurs when a bystander fears that helping could lead others to believe that they are the perpetrator. This fear can cause people to not act in dire situations.

Another example is priming. Priming occurs when a person is given cues that will influence future actions. For example, if a person is given a list of words that are associated with home decor and furniture and then is asked to give a five-letter word, answers like chair or table would be more likely than pasta.

In social situations, Garcia et al. found that simply thinking of being in a group could lead to lower rates of helping in emergency situations. This occurs because groups are often associated with “being lost in a crowd, being deindividuated, and having a lowered sense of personal accountability” (Garcia et al., 2002, p. 845).

Thus, the authors argue that the way a person was primed could also influence their ability to help. These alternate theories highlight the fact that the bystander effect is a complex phenomenon that encompasses a variety of ideologies.

Bystander Experiments

In one of the first experiments of this type, Latané & Darley (1968) asked participants to sit on their own in a room and complete a questionnaire on the pressures of urban life.

Smoke (actually steam) began pouring into the room through a small wall vent. Within two minutes, 50 percent had taken action, and 75 percent had acted within six minutes when the experiment ended.

In groups of three participants, 62 percent carried on working for the entire duration of the experiment.

In interviews afterward, participants reported feeling hesitant about showing anxiety, so they looked to others for signs of anxiety. But since everyone was trying to appear calm, these signs were not evident, and therefore they believed that they must have misinterpreted the situation and redefined it as ‘safe.’

This is a clear example of pluralistic ignorance, which can affect the answer at step 2 of the Latané and Darley decision model above.

Genuine ambiguity can also affect the decision-making process. Shotland and Straw (1976) conducted an interesting experiment that illustrated this.

They hypothesized that people would be less willing to intervene in a situation of domestic violence (where a relationship exists between the two people) than in a situation involving violence involving two strangers. Male participants were shown a staged fight between a man and a woman.

In one condition, the woman screamed, ‘I don’t even know you,’ while in another, she screamed, ‘I don’t even know why I married you.’

Three times as many men intervened in the first condition as in the second condition. Such findings again provide support for the decision model in terms of the decisions made at step 3 in the process.

People are less likely to intervene if they believe that the incident does not require their personal responsibility.

Critical Evaluation

While the bystander effect has become a cemented theory in social psychology, the original account of the murder of Catherine Genovese has been called into question. By casting doubt on the original case, the implications of the Darley and Latané research are also questioned.

Manning et al. (2007) did this through their article “The Kitty Genovese murder and the social psychology of helping, The parable of the 38 witnesses”. By examining the court documents and legal proceedings from the case, the authors found three points that deviate from the traditional story told.

While it was originally claimed that thirty-eight people witnessed this crime, in actuality, only a few people physically saw Kitty Genovese and her attacker; the others just heard the screams from Kitty Genovese.

In addition, of those who could see, none actually witnessed the stabbing take place (although one of the people who testified did see a violent action on behalf of the attacker.)

This contrasts with the widely held notion that all 38 people witnessed the initial stabbing.

Lastly, the second stabbing that resulted in the death of Catherine Genovese occurred in a stairwell which was not in the view of most of the initial witnesses; this deviates from the original article that stated that the murder took place on Austin Street in New York City in full view of at least 38 people.

This means that they would not have been able to physically see the murder take place. The potential inaccurate reporting of the initial case has not negated the bystander effect completely, but it has called into question its applicability and the incomplete nature of research concerning it.

Limitations of the Decision-Helping Model

Schroeder et al. (1995) believe that the decision-helping model provides a valuable framework for understanding bystander intervention.

Although primarily developed to explain emergency situations, it has been applied to other situations, such as preventing someone from drinking and driving, to deciding to donate a kidney to a relative.

However, the decision model does not provide a complete picture. It fails to explain why ‘no’ decisions are made at each stage of the decision tree. This is particularly true after people have originally interpreted the event as an emergency.

The decision model doesn’t take into account emotional factors such as anxiety or fear, nor does it focus on why people do help; it mainly concentrates on why people don’t help.

Piliavin et al. (1969, 1981) put forward the cost–reward arousal model as a major alternative to the decision model and involves evaluating the consequences of helping or not helping.

Whether one helps or not depends on the outcome of weighing up both the costs and rewards of helping. The costs of helping include effort, time, loss of resources, risk of harm, and negative emotional response.

The rewards of helping include fame, gratitude from the victim and relatives, and self-satisfaction derived from the act of helping. It is recognized that costs may be different for different people and may even differ from one occasion to another for the same person.

Accountability Cues

According to Bommel et al. (2012), the negative account of the consequences of the bystander effect undermines the potential positives. The article “Be aware to care: Public self-awareness leads to a reversal of the bystander effect” details how crowds can actually increase the amount of aid given to a victim under certain circumstances.

One of the problems with bystanders in emergency situations is the ability to split the responsibility (diffusion of responsibility).

Yet, when there are “accountability cues,” people tend to help more. Accountability cues are specific markers that let the bystander know that their actions are being watched or highlighted, like a camera. In a series of experiments, the researchers tested if the bystander effect could be reversed using these cues.

An online forum that was centered around aiding those with “severe emotional distress” (Bommel et al., 2012) was created.

The participants in the study responded to specific messages from visitors of the forum and then rated how visible they felt on the forum.

The researchers postulated that when there were no accountability cues, people would not give as much help and would not rate themselves as being very visible on the forum; when there are accountability cues (using a webcam and highlighting the name of the forum visitor), not only would more people help but they would also rate themselves as having a higher presence on the forum.

As expected, the results fell in line with these theories. Thus, targeting one’s reputation through accountability cues could increase the likelihood of helping. This shows that there are potential positives to the bystander effect.

Neuroimaging Evidence

Researchers looked at the regions of the brain that were active when a participant witnessed emergencies. They noticed that less activity occurred in the regions that facilitate helping: the pre- and postcentral gyrus and the medial prefrontal cortex (Hortensius et al., 2018).

Thus, one’s initial biological response to an emergency situation is inaction due to personal fear. After that initial fear, sympathy arises, which prompts someone to go to the aid of the victim. These two systems work in opposition; whichever overrides the other determines the action that will be taken.

If there is more sympathy than personal distress, the participant will help. Thus, these researchers argue that the decision to help is not “reflective” but “reflexive” (Hortensius et al., 2018).

With this in mind, the researchers argue for a more personalized view that takes into account one’s personality and disposition to be more sympathetic rather than utilize a one-size-fits-all overgeneralization.

Darley, J. M., & Latané´, B. (1968). Bystander intervention in emergencies: Diffusion of responsibility . Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 8 , 377–383.

Garcia, Stephen M, Weaver, Kim, Moskowitz, Gordon B, & Darley, John M. (2002). Crowded Minds. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83 (4), 843-853.

Hortensius, Ruud, & De Gelder, Beatrice. (2018). From Empathy to Apathy: The Bystander Effect Revisited. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 27 (4), 249-256.

Latané´, B., & Darley, J. M. (1968). Group inhibition of bystander intervention in emergencies . Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 10 , 215–221.

Latané´, B., & Darley, J. M. (1970). The unresponsive bystander: Why doesn’t he help? New York, NY: Appleton-Century-Croft.

Latané´, B., & Darley, J. M. (1976). Help in a crisis: Bystander response to an emergency . Morristown, NJ: General Learning Press.

Latané´, B., & Nida, S. (1981). Ten years of research on group size and helping . Psychological Bulletin, 89 , 308 –324.

Manning, R., Levine, M., & Collins, A. (2007). The Kitty Genovese murder and the social psychology of helping: The parable of the 38 witnesses. American Psychologist, 62 , 555-562.

Prentice, D. (2007). Pluralistic ignorance. In R. F. Baumeister & K. D. Vohs (Eds.), Encyclopedia of social psychology (Vol. 1, pp. 674-674) . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.

Rendsvig, R. K. (2014). Pluralistic ignorance in the bystander effect: Informational dynamics of unresponsive witnesses in situations calling for intervention. Synthese (Dordrecht), 191 (11), 2471-2498.

Shotland, R. L., & Straw, M. K. (1976). Bystander response to an assault: When a man attacks a woman. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 34 (5), 990.

Siegal, H. A. (1972). The Unresponsive Bystander: Why Doesn’t He Help? 1(3) , 226-227.

Van Bommel, Marco, Van Prooijen, Jan-Willem, Elffers, Henk, & Van Lange, Paul A.M. (2012). Be aware to care: Public self-awareness leads to a reversal of the bystander effect. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 48 (4), 926-930.

Further information

Latané, B., & Nida, S. (1981). Ten years of research on group size and helping. Psychological Bulletin , 89, 308 –324.

BBC Radio 4 Case Study: Kitty Genovese

Piliavin Subway Study

Related Articles

Social Science

Hard Determinism: Philosophy & Examples (Does Free Will Exist?)

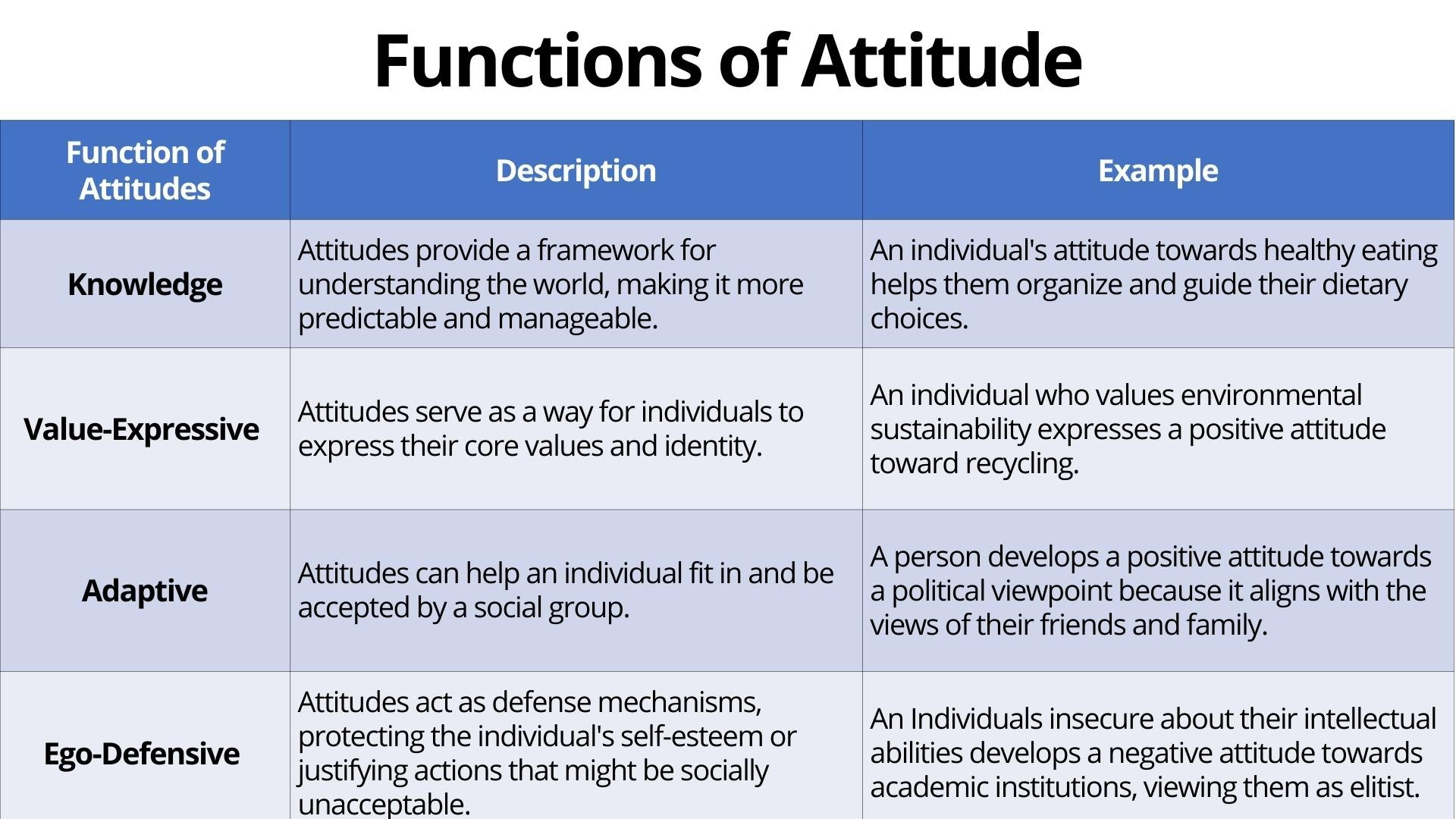

Functions of Attitude Theory

Understanding Conformity: Normative vs. Informational Social Influence

Social Control Theory of Crime

Emotions , Mood , Social Science

Emotional Labor: Definition, Examples, Types, and Consequences

Famous Experiments , Social Science

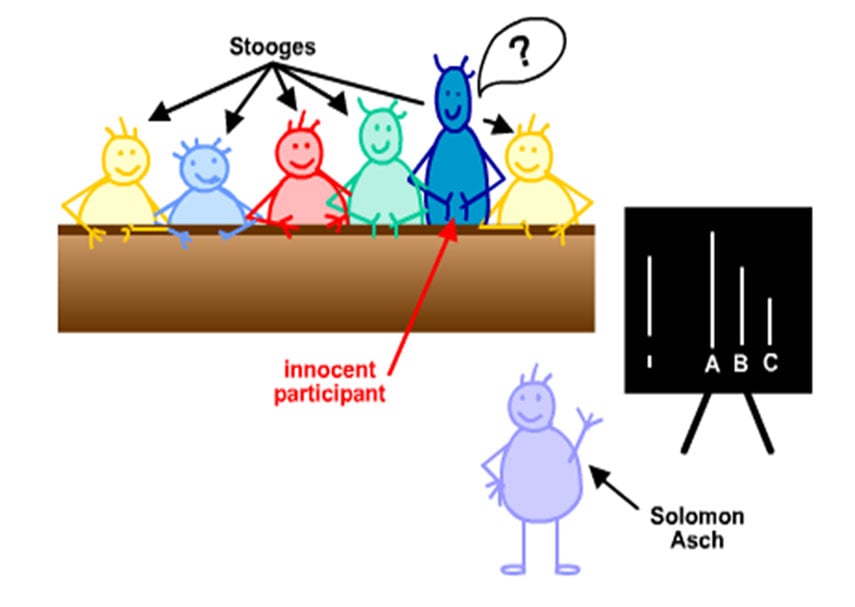

Solomon Asch Conformity Line Experiment Study

- Entertainment

- Environment

- Information Science and Technology

- Social Issues

Home Essay Samples Psychology

Essay Samples on The Bystander Effect

The bystander effect refers to the social phenomenon where individuals are less likely to offer assistance to someone in need when there are other people present. It suggests that the presence of others can influence and inhibit an individual’s willingness to take action, even in emergency situations. The bystander effect was first coined and studied following the infamous case of Kitty Genovese in 1964, where numerous witnesses failed to intervene or call for help during her brutal murder.

Writing a Bystander Effect Essay

The bystander effect essay provides an ideal platform to delve into the complexities surrounding this fascinating subject matter. Here are the tips you can use:

- Begin by introducing the concept of the bystander effect, highlighting its prevalence in various scenarios, such as emergencies, public spaces, and social media.

- Analyze the psychological aspects at play, including diffusion of responsibility and social influence, which contribute to the bystander effect.

- Explore the ethical and moral implications of the bystander effect, discussing the potential consequences of inaction and the importance of taking responsibility for the well-being of others.

- Incorporate relevant studies and academic sources to provide a solid foundation for your arguments and to strengthen the credibility of your analysis.

- By offering practical recommendations to mitigate the bystander effect, such as fostering a sense of responsibility and cultivating empathy, your essay can inspire readers to become proactive agents of change.

Immerse yourself in the captivating realm of the bystander effect with our diverse collection of student essays on bystander effect.

Emergency Management and Bystander Behavior Effect

This essay will compare and contrast two approaches to understanding bystander responses to emergencies. The approaches explored in the essay are the experiment approach and discourse analysis, each being explained in further detail later in the essay. Bystander behavior (effect) can be explained as the...

- Emergency Management

- Human Behavior

- The Bystander Effect

The Concept of a Passive and Active Bystander Effect

Groups willingness to help others can be affected in many ways one specifically being the bystander effect. The bystander effect is the tendency for people be unresponsive in high pressure situations due to the presence of other people (Darley & Latane, 1968). There are two...

- Social Psychology

How Does Being in a Group Affect Bystander Intervention

Bystander impacts how people will react in a certain situation. I think it because our brain reaches maturity in a way that we should have priority first before anything else. For example, if an incident happened on a road, some people are going to the...

The Influence Of Modern Technology Could Shape A Person Into Bystander

Twenty-eight-year-old Catherine 'Kitty' Genovese was murdered and raped on the street in Kew Gardens, New York, in the early morning hours of March 13, 1964. Initially, the incident received little attention until two weeks later, in the New York Times, Martin Gansberg's infamous article, 'Thirty-Eight...

- Modern Society

Explaining the Passive Bystander Effect and Group Polarization

The following essay will discuss the role of informational and normative influences in explaining two psychological phenomena, specifically the Passive Bystander Effect and Group Polarization. Conformity is a type of majority social influence, involving a change in attitude, beliefs or behaviour to align with group...

- Individual Identity

Stressed out with your paper?

Consider using writing assistance:

- 100% unique papers

- 3 hrs deadline option

Factors That Trigger or Decrease the Bystander Effect

According to Ann Gelsheimer (2007) few important factors that may increase or decrease the bystander effect in any given situation are: Group cohesiveness Several researchers have found that increased number of bystanders facilitated helping when the group was highly cohesive and social responsibility was valued...

The Case Study of Bystander Effect

Kitty Genovese, a 28-year-old woman, was murdered in front of her home on March 13, 1964. A New York Times article claimed that 38 witnessed or heard the crime, but no one responded or aided her to help. This event inspired social psychologists John M....

The Bystander Effect: Social Psychological Claim

The Bystander Effect is a Social Psychological claim that most individuals are less likely to help a victim when other people are present. This creates almost a type of fear in most because they are scared of what people would think or say because of...

The Causes and Sonsequences of the Bystander Effect

In an emergency, if there are four or more bystanders, the chances of at least one person intervening is only thirty-one percent. A bystander is defined as an individual who observes or hears an emergency but does not take part in it. The bystander effect...

Genocide Witnesses and the Bystander Effect

'Today, people don't talk anymore about the mass murder of six million human beings' (Wiesenthal 156). Even though this statement refers to the Holocaust, it applies to various genocides that have occurred throughout history. No matter the place or time, the same reaction happens as...

Best topics on The Bystander Effect

1. Emergency Management and Bystander Behavior Effect

2. The Concept of a Passive and Active Bystander Effect

3. How Does Being in a Group Affect Bystander Intervention

4. The Influence Of Modern Technology Could Shape A Person Into Bystander

5. Explaining the Passive Bystander Effect and Group Polarization

6. Factors That Trigger or Decrease the Bystander Effect

7. The Case Study of Bystander Effect

8. The Bystander Effect: Social Psychological Claim

9. The Causes and Sonsequences of the Bystander Effect

10. Genocide Witnesses and the Bystander Effect

- Confirmation Bias

- Neuroscience

- Development

- Child Observation

- Cognitive Psychology

- Child Psychology

Need writing help?

You can always rely on us no matter what type of paper you need

*No hidden charges

100% Unique Essays

Absolutely Confidential

Money Back Guarantee

By clicking “Send Essay”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement. We will occasionally send you account related emails

You can also get a UNIQUE essay on this or any other topic

Thank you! We’ll contact you as soon as possible.

Bystander Effect

Reviewed by Psychology Today Staff

The bystander effect occurs when the presence of others discourages an individual from intervening in an emergency situation, against a bully, or during an assault or other crime . The greater the number of bystanders, the less likely it is for any one of them to provide help to a person in distress. People are more likely to take action in a crisis when there are few or no other witnesses present.

- Understanding the Bystander Effect

- Be an Active Bystander

Social psychologists Bibb Latané and John Darley popularized the concept of the bystander effect following the infamous murder of Kitty Genovese in New York City in 1964. The 28-year-old woman was stabbed to death outside her apartment; at the time, it was reported that dozens of neighbors failed to step in to assist or call the police.

Latané and Darley attributed the bystander effect to two factors: diffusion of responsibility and social influence. The perceived diffusion of responsibility means that the more onlookers there are, the less personal responsibility individuals will feel to take action. Social influence means that individuals monitor the behavior of those around them to determine how to act.

It’s natural for people to freeze or go into shock when seeing someone having an emergency or being attacked. This is usually a response to fear —the fear that you are too weak to help, that you might be misunderstanding the context and seeing a threat where there is none, or even that intervening will put your own life in danger.

It can be hard to tease out the many reasons people fail to take action, but when it comes to sexual assault against women, research has shown that witnesses who are male, hold sexist attitudes, or are under the influence of drugs or alcohol are less likely to actively help a woman who seems too incapacitated to consent to sexual activity.

The same factors that lead to the bystander effect can be used to increase helping behaviors. Individuals are more likely to behave well when they feel themselves being watched by “the crowd,” and when their actions align with their social identities. For example, someone who identifies as pro-environment will take more effort to recycle when they believe they are being observed.

Good people can be complicit in bad behavior (hence the common “just following orders” excuse). Someone who speaks up against bullying is called an “upstander.” Upstanders have confidence in their judgment and values and believe their actions will make a difference. They are more likely to do the right thing because they take the time to stop and think before acting.

The intervention of bystanders is often the only reason why bullying and other crimes cease. The social and behavioral paralysis described by the bystander effect can be reduced with awareness and, in some cases, explicit training. Secondary schools and college campuses encourage students to speak up when witnessing an act of bullying or a potential assault.

One technique is to behave as if one is the first or only person witnessing a problem. Often, when one person takes action, if only to shout, "Hey, what's going on?" or "The police are coming," others may be emboldened to take action as well. That said, an active bystander is most effective when they assume that they themselves are the sole person taking charge; giving direction to other bystanders to assist can, therefore, be critically important.

Don’t expect others to be the first to act in a crisis—just saying “Stop” or “Help is on the way” can prevent further harm. Speak up using a calm, firm tone. Give others directions to get them involved in helping too. Do your best to ensure the safety of the victim, and don’t be afraid to seek assistance when you need it.

If a bystander can help someone without risking their own life and chooses not to, they are usually considered morally guilty. But the average person is typically under no legal obligation to help in an emergency. However, some places have adopted duty-to-rescue laws, making it a crime not to help a person in need.

Yes, some people can be held legally responsible for negative outcomes if they get involved. Fear of legal consequences can be a major contributor to the bystander effect. Some jurisdictions have passed Good Samaritan laws as encouragement for bystanders to act, offering legal protection to those trying to help victims. However, these laws are often limited.

When training yourself to be an active bystander, it helps to cultivate qualities like empathy. Try to see the situation from the victim’s perspective. Worry less about the consequences of helping and more about the example you are setting for future generations. If you are the victim, pick out one person in the crowd and make eye contact. People’s natural tendencies towards altruism may move them to help if given the chance.

Here’s a way to understand how attachment and bonding in infancy shape one’s sense of self, degree of emotional security, and capacity for independent thinking.

Workplace bullying is a community problem that requires a community response to stop the abuse cycle.

Despite being continually reminded that if we “see something, say something,” most people don’t. Research reveals how to boost benevolent bystander behavior.

Engaged citizenship is especially important in a fragmented world.

Taking these simple steps to prepare your kids for what to expect as their bodies develop can reduce harm and strengthen your relationship.

Many morally courageous people in history are praised after great sacrifices are made; is there a way for people to support their bravery in the moment instead?

Let’s teach psychology students about the positive aspects of human nature, rather than highlighting the negative. Early flawed theories and studies have "sold human nature short."

A Personal Perspective: I was walking through an airport when I saw someone who I thought may have overdosed. I wasn't sure what to do.

Can you ask for help when you need it? Learn how to ask in an effective and respectful way to get what you need and protect the relationship, too.

Emergencies often feature acts of heroic altruism. Why do people impulsively risk their lives for others? Because we are interconnected through empathy.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

At any moment, someone’s aggravating behavior or our own bad luck can set us off on an emotional spiral that threatens to derail our entire day. Here’s how we can face our triggers with less reactivity so that we can get on with our lives.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

Why People Stand By

A comprehensive study about the bystander effect.

- Nithya Ganti BASIS Independent Silicon Valley

- Sori Baek Horizon Academics

Bystander effect is the phenomenon that describes how, when more people are around, each individual is less likely to intervene. While the bystander effect is an integral part of studying social behaviors and group thinking, the many caveats it presents itself with must be considered. Every situation differs based on location, people, and circumstance, so the idea of the bystander effect is not valid in every scenario, as evidenced by the various counter-examples and contradictory findings researchers have discovered. However, the bystander effect is still very important to study because understanding what encourages/prevents people from helping is critical to decrease the effect of the bystander effect to promote helping behavior. In this paper, we discuss the various factors that affect the prevalence of the bystander effect: perceived physical and social harm to the helper, responsibility diffusion, and perceived helpfulness.

Author Biography

Sori baek, horizon academics.

Sori Baek is a Ph.D. candidate in the Psychology & Neuroscience Joint Degree Program at Princeton University, and her research is funded by the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship. She is a developmental cognitive neuroscientist, which means that she is mainly interested in how babies and kids think and use their brains. She uses neuroimaging methods and behavioral studies to conduct research on how babies and kids use their brains to perceive things in the world, make and process predictions, learn new things, and remember past events! Prior to her PhD work, she was a Lab Manager and Research Coordinator at the Laboratory of Behavioral and Cognitive Neuroscience at Stanford University. Her personal website with more information her research can be found here: https://www.soribaek.com

References or Bibliography

Asch, S. E. (1955). Opinions and social pressure. Scientific American, 193(5), 31-35. From https://www.jstor.org/stable/24943779

Badalge, K. (2017, May 25). Our phones make us feel like activists, but they're actually turning us into bystanders. Retrieved August 31, 2020, from https://qz.com/991167/our-phones-make-us-feel-like-social-media-activists-but-theyre-actually-turning-us-into-bystanders/

Carlson, M. (2008). I’d rather go along and be considered a man: Masculinity and bystander intervention. Journal of Men’s Studies, 16, 3–17. https://doi.org/10.3149/jms.1601.3

Casey, E. A., & Ohler, K. (2012). Being a positive bystander: Male antiviolence allies’ experiences of “stepping up”. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 27, 62–83

Darley, J. M., & Latané, B. (1968). Bystander intervention in emergen- cies: Diffusion of responsibility. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 8, 377-383. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260511416479

Dumesnil, H., & Verger, P. (2009). Public awareness campaigns about depression and suicide: a review. Psychiatric Services, 60(9), 1203-1213. https://doi.org/10.1176/ps.2009.60.9.1203

Eagly, A. H., & Steffen, V. J. (1986). Gender and aggressive behavior: A meta-analytic review of the social psychological literature. Psychological Bulletin, 100, 309–330. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.100.3.309

Fabiano, P. M., Perkins, H. W., Berkowitz, A., Linkenbach, J., & Stark, C. (2003). Engaging men as social justice allies in ending violence against women: Evidence for a social norms approach. Journal of American College Health, 52, 105–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448480309595732

Falk, G., & Gardner, C. (2002). Stigma: How we treat outsiders. Prometheus Books. https://doi.org/10.2307/3089070

Fischer, P., & Greitemeyer, T. (2013). The positive bystander effect: Passive bystanders increase helping in situations with high expected negative consequences for the helper. The Journal of social psychology, 153(1), 1-5. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224545.2012.697931

Fischer, P., Greitemeyer, T., Pollozek, F., & Frey, D. (2006). The unresponsive bystander: Are bystanders more responsive in dangerous emergencies?. European journal of social psychology, 36(2), 267-278. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.297

Fischer, P., Krueger, J. I., Greitemeyer, T., Vogrincic, C., Kastenmüller, A., Frey, D., ... & Kainbacher, M. (2011). The bystander-effect: a meta-analytic review on bystander intervention in dangerous and non-dangerous emergencies. Psychological bulletin, 137(4), 517. From https://psycnet.apa.org/buy/2011-08829-001?mod=article_inline

Garcia, S. M., Weaver, K., Moskowitz, G. B., & Darley, J. M. (2002). Crowded minds: the implicit bystander effect. Journal of personality and social psychology, 83(4), 843. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.83.4.843

Geyer-Schulz, A., Ovelgönne, M., & Sonnenbichler, A. C. (2010, July). Getting help in a crowd: A social emergency alert service. In 2010 International Conference on e-Business (ICE-B) (pp. 1-12). IEEE. From https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/5740440

Gibbons, F. X., & Wicklund, R. A. (1982). Self-focused attention and helping behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 43(3), 462. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.43.3.462

Galván, V. V., Vessal, R. S., & Golley, M. T. (2013). The effects of cell phone conversations on the attention and memory of bystanders. PloS one, 8(3), e58579. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0058579

Guyton, M. J. (1998). Contributors to individual differences in the development of prosocial responsiveness in preschoolers. Dissertation Abstracts International, 58. (1-B) 0439. From https://www.elibrary.ru/item.asp?id=5543545

Hensley, T. R., & Griffin, G. W. (1986). Victims of groupthink: The Kent State University board of trustees and the 1977 gymnasium controversy. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 30(3), 497-531. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002786030003006

Hudson, J. M., & Bruckman, A. S. (2004). The bystander effect: A lens for understanding patterns of participation. The Journal of the Learning Sciences, 13(2), 165-195. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327809jls1302_2

Hurley, K. (2017, December 27). How to Raise Assertive and Confident Girls. Retrieved September 03, 2020, from https://www.rootsofaction.com/assertive-confident-girls/

Iacoboni, M. (2009). Imitation, empathy, and mirror neurons. Annual review of psychology, 60, 653-670. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163604

Jansen, A. S., Van Nguyen, X., Karpitskiy, V., Mettenleiter, T. C., & Loewy, A. D. (1995). Central command neurons of the sympathetic nervous system: basis of the fight-or-flight response. Science, 270(5236), 644-646. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.270.5236.644

Joyce, A. (2019, April 21). Are you raising nice kids? A Harvard psychologist gives 5 ways to raise them to be kind. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/parenting/wp/2014/07/18/are-you-raising-nice-kids-a-harvard-psychologist-gives-5-ways-to-raise-them-to-be-kind/

Kalafat, J., & Elias, M. (1994). An evaluation of a school-based suicide awareness intervention. Suicide & life-threatening behavior, 24(3), 224–233. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1943-278X.1994.tb00747.x

Karakashian, L. M., Walter, M. I., Christopher, A. N., & Lucas, T. (2006). Fear of negative evaluation affects helping behavior: The bystander effect revisited. North American Journal of Psychology, 8(1), 13-32. From https://intranet.newriver.edu/images/stories/library/stennett_psychology_articles/Fear_of_Negative_Evaluation_Affects_helping_Behavior_-_The_Bystander_Effect_Revisited.pdf

Latané, B., & Darley, J. M. (1968). Group inhibition of bystander inter- vention in emergencies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 10, 215-221. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0026570

Latané, B., & Nida, S. (1981). Ten years of research on group size and helping. Psychological Bulletin, 89, 308-324. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.89.2.308

Leone, R. M., Parrott, D. J., Swartout, K. M., & Tharp, A. T. (2016). Masculinity and bystander attitudes: Moderating effects of masculine gender role stress. Psychology of violence, 6(1), 82. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038926

Obermaier, M., Fawzi, N., & Koch, T. (2016). Bystanding or standing by? How the number of bystanders affects the intention to intervene in cyberbullying. New media & society, 18(8), 1491-1507. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444814563519

O’connell, P., Pepler, D., & Craig, W. (1999). Peer involvement in bullying: Insights and challenges for intervention. Journal of adolescence, 22(4), 437-452. From https://d1wqtxts1xzle7.cloudfront.net/45476023/Peer_involvement_in_bullying_Insights_an20160509-20034-4ikg2s.pdf?1462795346=&response-content-disposition=inline%3B+filename%3DPeer_involvement_in_bullying_insights_an.pdf&Expires=1601704900&Signature=Ey4~mEv9FqRJ6yuUyCsY-NV0CGINhNCIYPn7gE84wEqsj9jI~Cs4spLPEB7Kj22FZQP4wki7odKBAhSFF42LVFsUrBHlGi6agmkiOkpM1JSUSownCWuqhBn9tZfYLK3wJtuizgg-FIwvnFZl1Sed5ASOxSy14HTYvDd26aBp-9JU8d0RYAzNsJzV6ykbCVHKesy37tTBwF~2l9XJMb10yibXUk20tPEGH9ZpndRmp8SQc-6kRDnl~gWH9yIZJnart6-mpmcPxqdPqKVqjOucoyhwlyJ2E9M15A4un8vyZ5oDj6KKus4r-VttpsD~X9EYk8nEGg7YfSSLkOUyX-Y68g__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAJLOHF5GGSLRBV4ZA

Schwartz, S. H., & Clausen, G. T. (1970). Responsibility, norms, and helping in an emergency. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 16, 299-310. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0029842

Spence, J. T. (1983). Comment on Lubinski. Tellegen and Butcher's "Masculinity, femininity, and androgyny viewed and assessed as distinct concepts." Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 44, 440-446. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.44.2.440

Tice, D. M., & Baumeister, R. F. (1985). Masculinity inhibits helping in emergencies: Personality does predict the bystander effect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 49(2), 420. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.49.2.420

Van Bommel, M., van Prooijen, J. W., Elffers, H., & Van Lange, P. A. (2012). Be aware to care: Public self-awareness leads to a reversal of the bystander effect. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 48(4), 926-930. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2012.02.011

How to Cite

- Endnote/Zotero/Mendeley (RIS)

Copyright (c) 2021 Nithya Ganti; Sori Baek

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License .

Copyright holder(s) granted JSR a perpetual, non-exclusive license to distriute & display this article.

Narratives of Bystanding and Upstanding: Applying a Bystander Framework in Higher Education

- First Online: 22 April 2021

Cite this chapter

- Amanda Sugimoto 3 &

- Kathy Carter 4

561 Accesses

Preservice teachers come to higher education with rich, storied knowledge about schools, schooling, and students based on their previous experiences as K-12 students. They then add to this knowledge through their teacher preparation coursework and field-based practicums. This study used a bystander framework and narrative inquiry to explore how previous bystander experiences involving the marginalization or bullying of an emergent bilingual student shaped a group of 108 preservice teachers’ developing storied knowledge about bystanding, upstanding, and issues of social justice in schools. This chapter details both the prominent plot patterns from preservice teacher bystander narratives, and how these narratives were used as pedagogy in the higher education classroom.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Abbreviations

Named by Latané and Darley ( 1969 ), the bystander effect is a psychological phenomenon where the more witnesses there are to an emergency and/or crime, the less likely they are to intervene.

Someone who intervenes in an injurious event, whether or not the intervention was successful. The term “active bystander” can also be used, but we intentionally use the term upstander with students to clearly differentiate bystanding from intervention.

An epistemology that involves studying the human phenomenon of how a person narrates or stories particular experiences, and, in turn, how this storying shapes a person’s beliefs, knowledge, and/or actions.

Banyard, V. L., Moynihan, M. M., & Crossman, M. T. (2009). Reducing sexual violence on campus: The role of student leaders as empowered bystanders. Journal of College Student Development, 50, 446–457. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.0.0083 .

Article Google Scholar

Banyard, V. L., Plante, E. G., & Moynihan, M. M. (2004). Bystander education: Bringing a broader community perspective to sexual violence prevention. Journal of Community Psychology, 32, 61–79. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.10078 .

Barnes, A., Cross, D., Lester, L., Hearn, L., Epstein, M., & Monks, H. (2012). The invisibility of covert bullying among students: Challenges for school intervention. Australian Journal of Guidance and Counseling, 22 (02), 206–226. https://doi.org/10.1017/jgc.2012.27 .

Bierhoff, H. W. (2002). Prosocial behaviour. Psychology Press. https://www.kobo.com/us/en/ebook/prosocial-behaviour-1 .

Bogdan, R. C., & Biklen, S. K. (2006). Qualitative research for education: An introduction to theories and methods. Pearson. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED419813 .

Bruner, J. (1985). Narrative and paradigmatic modes of thought. In E. Eisner (Ed.), Learning and teaching the ways of knowing (pp. 97–115). University of Chicago Press. https://www.tcrecord.org/Content.asp?ContentId=19134 .

Burn, S. M. (2009). A situational model of sexual assault prevention through bystander education. Sex Roles, 60 , 779–792. https://digitalcommons.calpoly.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1030&context=psycd_fac .

Carter, K. (1993). The place of story in the study of teaching and teacher education. Educational Researcher, 22 (1), 5–18. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X022001005 .

Carter, K. (1994). Preservice teachers’ well-remembered events and the acquisition of event-structured knowledge. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 26 (3), 235–252. https://doi.org/10.1080/0022027940260301 .

Carter, K., Sugimoto, A. T., Stoehr, K., & Carter, G. (2019). (Re)Storying school experience and transforming teacher education: Writing a new narrative for LGBTQ students. In L. Wilcox & C. Brant (Eds.), Teaching the teachers: LGBTQ issues in teacher education . American Educational Research Association. https://www.infoagepub.com/products/Teaching-the-Teachers .

Chafe, W. (1990). Some things that narrative tells us about the mind. In B. K. Britton & A. D. Pellegrini (Eds.), Narrative thought and narrative language (pp. 79–98). Erlbaum. http://dx.doi.org/10.4324/9781315808215 .

Chekroun, P., & Brauer, M. (2002). The bystander effect and social control behavior: The effect of the presence of others on people’s reactions to norm violations. European Journal of Social Psychology, 32, 853–867. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.126 .

Clandinin, J., & Connelly, M. (2000). Narrative inquiry: Experience and story in qualitative research. Jossey-Bass. https://www.wiley.com/en-us/Narrative+Inquiry%3A+Experience+and+Story+in+Qualitative+Research-p-9780787972769 .

Clandinin, D. J., Huber, J., Huber, M., Murphy, M. S., Orr, A. M., Pearce, M., & Steeves, P. (2006). Composing diverse identities: Narrative inquiries into the interwoven lives of children and teachers . Routledge. http://dx.doi.org/10.4324/9780203012468 .

Clandinin, D. J., Murphy, M. S., Huber, J., & Orr, A. M. (2009). Negotiating narrative inquiries: Living in a tension-filled midst. The Journal of Educational Research, 103 (2), 81–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220670903323404 .

Clark, A. M. (1998). The qualitative-quantitative debate: Moving from positivism and confrontation to post-positivism and reconciliation. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 27 (6), 1242–1249. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.1998.00651.x .

Clark, R. D., III, & Word, L. E. (1974). Where is the apathetic bystander? Situational characteristics of the emergency. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 29, 279–287. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0036000 .