An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Springer Nature - PMC COVID-19 Collection

An Overview of the Economics of Sports Gambling and an Introduction to the Symposium

Victor matheson.

College of the Holy Cross, Worcester, USA

Gambling in the Ancient World

Gambling likely predates recorded history. The casting of lots (from which we get the modern term “lottery”) is mentioned both in the Old and New Testaments of the Bible, most famously when Roman soldiers cast lots for the clothes of Jesus during his crucifixion. In Greek mythology, Hades, Poseidon, and Zeus divided the heavens, the seas, and the underworld through a game of chance.

Organized sports also have a long history. The Ancient Olympic Games date back to 776 BCE and persisted until 394 AD. The Circus Maximum in Rome, the home of horse and chariot racing events as well as gladiatorial contests for over one thousand years, was originally constructed around 500 BCE, and the Colosseum in Rome began hosting sporting events including gladiator fights in 80 AD. Variations of the ball game Pitz were played in Mesoamerica for nearly 3000 years beginning as early as 1400 BCE (Matheson 2019 ).

Given the prevalence of both sporting contests and gambling across many ancient civilizations, it is natural to conclude that the combined activity of sports gambling also has a long history. And, indeed it is widely reported that gambling was a popular activity at the Olympics and other ancient Panhellenic events in Greece and at the racing and fighting contests in ancient Rome. Problems associated with gambling were also widely reported. As early as 388 BCE, the boxer Eupolus of Thessaly was known to have paid opponents to throw fights in the Olympics. Rampant gambling in Rome led Caesar Augustus (c. BCE 20) to limit the activity to only a week-long festival called “Saturnalia” celebrated around the time of the winter solstice, while Emperor Commodus (AD 192) turned the royal palace into a casino and bankrupted the Roman Empire along the way (Matheson et al. 2018 ).

Just as in the modern day, gambling was often looked down upon by societal leaders in antiquity. Horace (Ode III., 24; 23 BCE) wrote, “The young Roman is no longer devoted to the manly habits of riding and hunting; his skills seem to develop more in the games of chances forbidden by law.” Juvenal (Satire I, 87; 101 AD), well-known for coining the term “bread and circuses” wrote, “Never has the torrent of vice been to irresistible or the depths of avarice more absorbing, or the passion for gambling more intense. None approach nowadays the gambling table with the purse; they must carry their strongbox. What can we think of these profligates more ready to lose 100,000 than to give a tunic to a slave dying with cold.” (Matheson 2019 ).

Gambling in Renaissance and Pre-industrial Revolution Europe

Gambling in Europe persisted into the Middle Ages and Renaissance. For example, although the true origins of the famous columns in Venice’s Piazza San Marco are lost to the mysteries of time, at least one history suggests they were erected around 1127 by Nicholas Barattieri, who was rewarded for this task by the local government with an exclusive right to operate a gaming table between the columns, an activity otherwise officially prohibited in the Republic (Schiavon 2020 ).

However, without the large sporting events of the ancient world, gambling turned more toward to precursors of modern casino games. Indeed, the gambling that occurred in the “small houses” or “casini” of the city of Venice is the origin of the modern term “casino,” and in 1638 Il Ridotto, “the Private Room,” became the first public, legal casino in the region (Schwarz 2006 ).

Until the formation of professional sports leagues in the mid- to late nineteenth century, horse racing was the predominant type of sports gambling across Europe and North America. The Newmarket Racecourse near Cambridge, UK, was founded in 1636 although races at the location date to even earlier. The racetrack was frequented by King Charles II earning horse racing the title of “the Sport of Kings” (Black 1891 ). The first racetrack in North America was established on Long Island in 1665, and horse racing has persisted in the USA since that time.

Prior to the mid-1800s, bets in horseracing were handled by bookmakers who set odds on individual races. This carries risk for the bookmaker who may be forced to pay out large winning bets as well as the bettor who may find that the bookmaker lacks the funds to cover all payouts. This problem was solved in 1867 in Paris when Joseph Oller, who later went on to open the famous Parisian nightclub the Moulin Rouge, developed pari-mutuel betting.

Under pari-mutuel betting, the returns are based not on independent odds set by a bookmaker but instead are endogenously generated by the gamblers themselves based upon the number and size of the bets made on various race participants (Canymeres 1946 ). This betting system rapidly became wildly popular for racing in Europe and USA and remains the standard for horse racing today throughout the world.

Gambling Throughout US History

Gambling was a common activity throughout colonial and early American history. Lotteries funded activities such as the original European settlement at Jamestown, the operations of prestigious universities such as Harvard and Princeton, and construction of historic Faneuil Hall in Boston. Card rooms were not unusual at taverns and roadhouses across the country, and the activity moved west onto riverboats and into saloons as westward expansion occurred during the 1800s (Grote and Matheson 2017 ).

However, the late 1800s and early 1900 witnessed a widespread decline the legality of all types of gambling throughout the USA. In the sports realm, by 1900 betting on horse races was made illegal except in Kentucky and Maryland, states that to this day host two of the three Triple Crown events in American horseracing, the Kentucky Derby and the Preakness Stakes. States began to relegalize gambling on horse racing in the 1930s as a method of economic stimulus during the Great Depression. Total horse racing handle peaked in the 1970s and has generally declined since that time due to increased competition from alternative forms of gambling such as state lotteries and casinos (and, in fact, many racetracks nationwide, known as “racinos,” are permitted to offer alternative forms of gambling such as slot machines on their grounds (Nash 2009 )). In 2019, horse racing’s handle in the USA totaled $11.0 billion (Jockey Club 2020 ).

The birth of professional sports leagues in the USA also gave immediate rise to new betting opportunities, as well as problems associated with corruption. The oldest professional league in the USA, baseball’s National League, formed in 1876, and by 1877 the Louisville Grays ended the season mired in a betting scandal and ceased operations. Similarly in football, the Ohio League, a forerunner to the modern National Football League (NFL), began play in 1903, and by 1906, the league was embroiled in a match fixing scandal between the Canton Bulldogs and the Massillon Tigers (Grote and Matheson 2017 ).

During the early years of professional sports leagues in the USA, betting on games, although generally illegal like most gambling in the period, was common either through direct bets made with bookies or through “pool cards” allowing gamblers to bet on a slate of games. Nevada, which in 1931 became the first state to relegalize most forms of gambling, authorized sports gambling in 1949, but high tax rates on wagers prevented major casinos from running sports books until 1974. Following the elimination of a 10% tax on sports gambling revenues in the state, the sport betting handle rose dramatically from $825,767 in 1973 to $3,873,217 in 1974, to $26,170,328 in 1975 (Grote and Matheson 2017 ). By 2019, Nevada’s 192 sportsbooks took in $5.3 billion in wagers or roughly 2.7% of total gaming revenues for the state (Nevada Gaming Control Board 2019 ).

While Nevada remained the only state offering full sports books, Montana, Oregon, and Delaware all offered pool cards through their state lotteries beginning in the 1970s. Montana first offered legal pool cards in 1974. Delaware followed in 1976 (even winning a court case against the NFL for the right to offer sports gambling), but its games folded in the following year due to difficulties in adhering to the state’s statutory guidelines about lottery contributions to state coffers. The Oregon Lottery sold NFL pool cards from 1998 to 2007 and National Basketball Association (NBA) game tickets in 1998 and 1999 (although the NBA ticket did not include games featuring Portland’s local NBA team). Pressure from the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) eventually led the state to terminate its sports gambling offerings under the threat of losing the opportunity to host NCAA post-season men’s basketball tournament (March Madness) games (Grote and Matheson 2017 ).

The Professional and Amateur Sports Protection Act (PAPSA), passed in 1992, prohibited states from legalizing sports gambling in any form including lotteries, casinos, and tribal casinos while grandfathering in the four states with existing sports gambling operations. In mid 2010s, the state of New Jersey, in an effort to revive its flagging casinos in Atlantic City, sued to overturn PAPSA, and in May 2018, the US Supreme Court declared PAPSA unconstitutional. While this ruling did not legalize sports gambling in any states, it did allow states the option to legalize sports gambling if they so choose. This symposium examines some of the economic issues facing the sports gambling industry as the American market opens up.

Issues Facing the New Sports Gambling Industry

The first and perhaps easiest question facing the industry is how quickly and how widely will sports gambling be adopted by states? Here it seems clear that sports gambling will follow the pattern seen in lottery and casino adoption, although almost certainly at a much faster pace. As noted by Garrett and Marsh ( 2002 ), once states began to legalize state lotteries, neighboring states began to feel pressure to legalize their own state games or otherwise lose consumer spending to lottery players crossing the border to buy tickets.

By 2020, this pressure had led all but 6 states to adopt lotteries after the first state lottery was reestablished in New Hampshire in 1964. Among the holdouts, Alaska and Hawaii are protected geographically from cross-border purchases, Nevada’s powerful gambling industry has successfully prevented the adoption of a state-sponsored competitor, and conservative religious cultures in Alabama, Mississippi, and Utah have stopped lotteries there. (Religious concerns have not stopped Mississippi from legalizing sports gambling, however. Perhaps God just really wants to put a few bucks down on Ole Miss to upset the Tide this year.)

With respect to sports gambling, New Jersey and Delaware legalized the activity immediately upon the Court’s decision in 2018, and many states followed suit. By the end of 2020, 20 states and the District of Columbia had legalized sports gambling, 6 had legalized sports gambling but were pending launch, and over 20 more states were considering legislation (Rodenberg 2020 ). It appears that sports gambling will soon be legal nearly nationwide.

The next big question facing the industry is assessing the potential size of the sports betting market. If sports wagering is restricted to in-person betting at existing casinos, the impact of nationwide legalization is likely to be quite modest. Extrapolating Nevada’s sport wagering data to the national casino market suggests that nationwide legalization might lead to as much as $20 billion in annual wagers and just under $1 billion in net casino revenues. While these figures may seem high, they pale in comparison to gambling figures in the UK where sports betting has been legal (although highly regulated) since 1960 and is widely available through over 8300 (as of March 2019) small, commercial betting shops spread throughout the country as well as through online betting sites.

In the most recent fiscal year prior to shutdowns caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, in-person betting shops in the UK generated $3.7 billion and online gambling generated another $2.8 billion in net gambling revenues (UK Gambling Commission 2020 ). This implies that UK bettors placed roughly $130 billion in wagers in 2019 or about $2000 per person in the country. If industry were to achieve a similar level of popularity in the US market, this would suggest over $600 billion in annual wagers and $32 billion in net sport gambling revenue. The $32 billion figure would be roughly twice the net gambling revenue generated by state lotteries across the country and slightly less than the $42 billion in net casino gaming revenue generated across the USA. Such revenue figures would likely only be possible with widespread adoption of legalized mobile sports gambling as well as within-game betting on individual plays as opposed to wagering solely on game outcomes.

Obviously, another major question facing the industry is the extent to which expanded access to sports gambling will bring in new players to the gambling industry overall or whether it will simply cannibalize existing gambling options such as state lotteries, horse racing, or casino gaming. The first paper in this symposium examines this topic by analyzing the determinants of sport gambling handle and its effects on other casino gaming at West Virginia casinos during roughly the first year of legalized sports betting in the state (Humpheys 2021). Brad Humphreys finds that the introduction of sports gambling seems to have significantly decreased overall state gaming tax revenues as gains from sport gambling taxes were far outweighed by decreases in tax revenues from video lottery terminals.

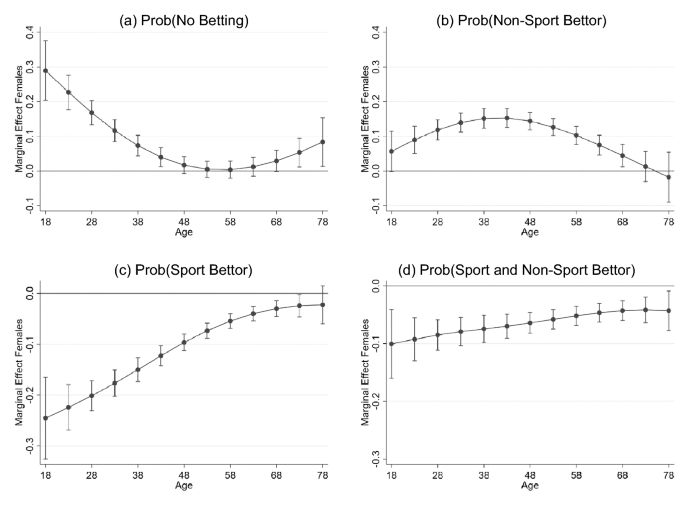

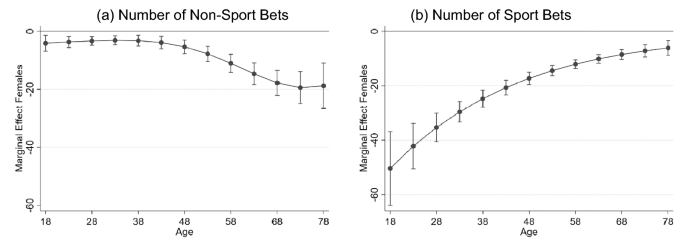

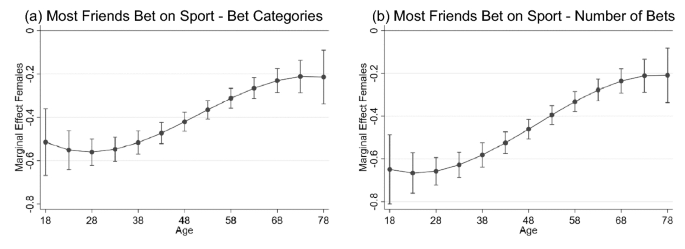

Of course, even if the problem of cannibalization is avoided by sports gambling attracting a new customer base, this is not without its own set of problems as sports wagering may introduce an entirely new population to the problems associated with pathological gambling and problem gaming (McGowan 2014 ). The second paper in this symposium examines health outcomes in Canada related to participation in gambling activities (Humphreys et al. 2021 ). Brad Humphreys, John Nyman, and Jane Ruseski show that recreational gambling has either no effect or even actually reduces the probability of having certain chronic health conditions and has a positive impact on life satisfaction suggesting the possibility that expanded sport gambling in the USA may not be associated with significant adverse health outcomes.

Legalized sports gambling is certain to bring about winners and losers. As noted above, depending on the level of cannibalization, other forms of gambling are likely to be losers such as horse racing, which is likely to continue its long-term decline in gambling handle (Nash 2009 ), and potentially casino gaming as identified by Humphreys ( 2021 ) in this symposium. On the other hand, sports book operators and mobile application developers are likely winners, so casinos themselves may either be either winners or losers in sports gambling legalization. It is interesting to note that established casinos have not been the only players to enter the online sports gambling market. In many states, the companies FanDuel and DraftKings, who prior to sports gambling legalization operated online fantasy football competitions of controversial legality, have already been able to leverage their fan bases in the online fantasy sports gaming communities into more traditional online sports gambling opportunities.

The sports leagues themselves may also be either winners or losers. Historically in the USA, leagues strongly opposed legal sports betting due to the potential for corruption. The history of sports in the USA is littered with betting scandals from the earliest days of the previously mentioned Louisville Grays and Canton Bulldogs to the infamous 1919 “Black Sox” World Series scandal to the 1948 NCAA basketball point-shaving scheme to the more recent actions of Major League Baseball (MLB) player and manager Pete Rose or NBA referee Tim Donaghy.

More recently, however, leagues have become more supportive of sports betting. In part, leagues acknowledge that legal betting markets make it easier for regulators to uncover suspicious betting behavior that could suggest corruption. More importantly, teams and leagues have also slowly recognized the potential for higher fan interest if fans have the opportunity to gamble on games. There is no doubt that the NCAA can attribute a significant portion of its 23-year, $19.6 billion television contract for March Madness on the popularity of “bracket pools,” and likewise the NFL understands the degree to which the explosion of fantasy football leagues has increased the popularity of its games. Humphreys et al. ( 2013 ) developed evidence of a significant correlation between betting and television viewership for regular season men’s NCAA basketball games.

Furthermore, the dramatic increase in professional athlete salaries over the past several decades in the USA has reduced worries of corruption. It is highly unlikely that star players in any major US league would jeopardize their massive earning potential as an athlete by accepting a bribe to alter a game outcome (and non-star players to whom a bribe could potentially be profitable are rarely in a position to influence games).

Those sports that remain at more significant risk to corruption are those with a high level of fan interest but low player salaries. This describes the working conditions of athletes prior to free-agency in the USA such as during the 1919 Black Sox scandal, referees like Tim Donaghy, and players in minor leagues or small national leagues as well as cricket players prior to the relatively recent formation of the Indian Premier League. It also describes the conditions of college athletes in the USA as the NCAA has successfully operated a cartel restricting the ability of even top college players from earning money as a player despite playing for teams generating millions or tens of millions of dollars annually for their host institutions. Thus, it comes as no surprise that the NCAA remains adamantly opposed to sport gambling in contrast to the major professional leagues in the USA.

Sports leagues are naturally eager to take steps to protect themselves against potential corruption in the wake of expanded gambling opportunities. The third paper in the symposium (Depken and Gandar 2021 ) explores the topic of integrity fees, payments by sports books to leagues, supposedly to pay for monitoring to ensure against match fixing. Craig Depken and John Gandar find evidence that integrity fees might influence sports books to establish lines that would minimize the chances for payouts in certain game situations.

Finally, legalized sports gambling will provide researchers with troves of new data to analyze one of the oldest questions in gambling economics: are sports betting markets efficient? The final paper in this symposium provides an excellent example of this type of research (Brymer et al. 2021 ). Rhett Brymer, Ryan M. Rodenberg, Huimiao Zheng, and Tim R. Holcomb examine whether referees in college football’s major conferences can be shown to have particular biases and if these biases are appropriately accounted for in the gambling markets. Studies like these will remain a fertile area for continued economic research.

As guest editor, I wish to thank Eastern Economic Journal co-editors Cynthia Bansak and Allan Zebedee, participants in the sports economics sessions at the 39th annual Eastern Economic Association Conference in New York City, February 2019, and numerous anonymous referees for their assistance in putting together this symposium. Most importantly, thanks go out to Eastern Economic Association Vice President Brad Humphreys who both proposed this symposium and collected and reviewed the participating papers. His name should really be on this guest editor’s introduction, but I guess he will have to settle to being co-author on two fine contributions within this symposium.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

- Black Robert. The Jockey Club and Its Founders: In Three Periods. London: Smith, Elder; 1891. [ Google Scholar ]

- Brymer, Rhett, Ryan M. Rodenberg, Huimiao Zheng, and Tim R. Holcomb. 2021. College Football Referee Bias and Sports Betting Impact. Eastern Economic Journal. 10.1057/s41302-020-00180-6.

- Canymeres, Ferran. 1946. Oller: L’Homme de la belle époque . Les Editions Universelles, Paris. Translated and summarized by the University of Auckland. https://www.cs.auckland.ac.nz/historydisplays/SecondFloor/Totalisators/ToteHistory/BookSummary.pdf . Accessed 1 November 2020.

- Depken, Craig A. and John Gandar. 2021. Integrity Fees in Sports Betting Markets. Eastern Economic Journal . 10.1057/s41302-020-00179-z. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ]

- Garrett Thomas A, Marsh Thomas L. The Revenue Impacts of Cross-Border Lottery Shopping in the Presence of Spatial Autocorrelation. Regional Science and Urban Economics. 2002; 32 (4):501–519. doi: 10.1016/S0166-0462(01)00089-8. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Grote Kent, Matheson Victor. Should Gambling Markets be Privatized? An Examination of State Lotteries in the United States. In: Rodríguez Plácido, Humphreys Brad, Simmons Robert., editors. Sports and Betting. London: Edward Elgar; 2017. pp. 21–37. [ Google Scholar ]

- Humphreys, Brad R. 2021. Legalized Sports Betting, VLT Gambling, and State Gambling Revenues: Evidence from West Virginia. Eastern Economic Journal. 10.1057/s41302-020-00178-0. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ]

- Humphreys, Brad R., John A. Nyman, and Jane E. Ruseski. 2021. The Effect of Recreational Gambling on Health and Well-Being. Eastern Economic Journal . 10.1057/s41302-020-00181-5.

- Humphreys Brad R, Paul Rodney J, Weinbach Andrew P. Consumption Benefits and Gambling: Evidence from the NCAA Basketball Betting Market. Journal of Economic Psychology. 2013; 39 (2):376–386. doi: 10.1016/j.joep.2013.05.010. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Jockey Club. 2020. Pari-mutuel Handle . http://www.jockeyclub.com/default.asp?section=FB&area=8 . Accessed 1 November 2020.

- Matheson Victor. The Rise and Fall (and Rise and Fall) of the Summer Olympics as an Economic Driver. In: Wilson John, Pomfret Richard., editors. Historical Perspectives on Sports Economics: Lessons from the Field. London: Edward Elgar; 2019. pp. 52–66. [ Google Scholar ]

- Matheson Victor, Schwab Daniel, Koval Patrick. Corruption in the Bidding, Construction, and Organization of Mega-Events: An Analysis of the Olympics and World Cup. In: Breuer Markus, Forrest David., editors. The Palgrave Handbook on the Economics of Manipulation in Professional Sports. New York: Palgrave McMillan; 2018. pp. 257–278. [ Google Scholar ]

- McGowan Richard. The Dilemma that is Sports Gambling. Gaming Law Review and Economics. 2014; 18 (7):670–678. doi: 10.1089/glre.2014.1875. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Nash, Betty Joyce. 2009. Sport of Kings: Horse Racing in Maryland . https://www.richmondfed.org/-/media/richmondfedorg/publications/research/econ_focus/2009/spring/pdf/economic_history.pdf .

- Nevada Gaming Control Board. 2019. Monthly Revenue Report, December 2019 . https://gaming.nv.gov/modules/showdocument.aspx?documentid=16490 .

- Rodenberg, Ryan. 2020. United States of sports betting: An updated map of where every state stands , ESPN.com. https://www.espn.com/chalk/story/_/id/19740480/the-united-states-sports-betting-where-all-50-states-stand-legalization .

- Schiavon, Alessia. 2020. Youth Committee of the Italian National Commission for UNESCO . https://artsandculture.google.com/exhibit/the-columns-of-san-marco-and-san-todaro-comitato-giovani-della-commissione-nazionale-italiana-per-l-unesco/2wIyGE9EqYPgIA?hl=en . Accessed 15 November 2020.

- Schwartz David G. Roll the Bones: The History of Gambling. New York: Gotham; 2006. [ Google Scholar ]

- UK Gambling Commission. 2020. Gambling Industry Statistics April 2015 to March 2019 . https://www.gamblingcommission.gov.uk/PDF/survey-data/Gambling-industry-statistics.pdf .

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

A statistical theory of optimal decision-making in sports betting

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation Dept of Biomedical Engineering, City College of New York, New York, NY, United States of America

- Jacek P. Dmochowski

- Published: June 28, 2023

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0287601

- Peer Review

- Reader Comments

The recent legalization of sports wagering in many regions of North America has renewed attention on the practice of sports betting. Although considerable effort has been previously devoted to the analysis of sportsbook odds setting and public betting trends, the principles governing optimal wagering have received less focus. Here the key decisions facing the sports bettor are cast in terms of the probability distribution of the outcome variable and the sportsbook’s proposition. Knowledge of the median outcome is shown to be a sufficient condition for optimal prediction in a given match, but additional quantiles are necessary to optimally select the subset of matches to wager on (i.e., those in which one of the outcomes yields a positive expected profit). Upper and lower bounds on wagering accuracy are derived, and the conditions required for statistical estimators to attain the upper bound are provided. To relate the theory to a real-world betting market, an empirical analysis of over 5000 matches from the National Football League is conducted. It is found that the point spreads and totals proposed by sportsbooks capture 86% and 79% of the variability in the median outcome, respectively. The data suggests that, in most cases, a sportsbook bias of only a single point from the true median is sufficient to permit a positive expected profit. Collectively, these findings provide a statistical framework that may be utilized by the betting public to guide decision-making.

Citation: Dmochowski JP (2023) A statistical theory of optimal decision-making in sports betting. PLoS ONE 18(6): e0287601. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0287601

Editor: Baogui Xin, Shandong University of Science and Technology, CHINA

Received: December 19, 2022; Accepted: June 8, 2023; Published: June 28, 2023

Copyright: © 2023 Jacek P. Dmochowski. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: Data is available at https://github.com/dmochow/optimal_betting_theory .

Funding: The author received no specific funding for this work.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

The practice of sports betting dates back to the times of Ancient Greece and Rome [ 1 ]. With the much more recent legalization of online sports wagering in many regions of North America, the global betting market is projected to reach 140 billion USD by 2028 [ 2 ]. Perhaps owing to its ubiquity and market size, sports betting has historically received considerable interest from the scientific community [ 3 ].

A topic of obvious relevance to the betting public, and one that has also been the subject of multiple studies, is the efficiency of sports betting markets [ 4 ]. While multiple studies have reported evidence for market inefficiencies [ 5 – 11 ], others have reached the opposite conclusion [ 12 , 13 ]. The discrepancy may signify that certain, but not all, sports markets exhibit inefficiencies. Research into sports betting has also revealed insights into the utility of the “wisdom of the crowd” [ 14 – 16 ], the predictive power of market prices [ 17 – 20 ], quantitative rating systems [ 21 , 22 ], and the important finding that sportsbooks exploit public biases to maximize their profits [ 13 , 23 ].

Indeed, the decisions made by sportsbooks to set the offered odds and payouts have been previously analyzed [ 13 , 23 , 24 ]. On the other hand, arguably less is known about optimality on the side of the bettor . The classic paper by Kelly [ 25 ] provides the theory for optimizing betsize (as a function of the likelihood of winning the bet) and can readily be applied to sports wagering. The Kelly bet sizing procedure and two heuristic bet sizing strategies are evaluated in the work of Hvattum and Arntzen [ 26 ]. The work of Snowberg and Wolfers [ 27 ] provides evidence that the public’s exaggerated betting on improbable events may be explained by a model of misperceived probabilities. Wunderlich and Memmert [ 28 ] analyze the counterintuitive relationship between the accuracy of a forecasting model and its subsequent profitability, showing that the two are not generally monotonic. Despite these prior works, idealized statistical answers to the critical questions facing the bettor, namely what games to wager on, and on what side to bet, have not been proposed. Similarly, the theoretical limits on wagering accuracy, and under what statistical conditions they may be attained in practice, are unclear.

To that end, the goal of this paper is to provide a statistical framework by which the astute sports bettor may guide their decisions. Wagering is cast in probabilistic terms by modeling the relevant outcome (e.g. margin of victory) as a random variable. Together with the proposed sportsbook odds, the distribution of this random variable is employed to derive a set of propositions that convey the answers to the key questions posed above. This theoretical treatment is complemented with empirical results from the National Football League that instantiate the derived propositions and shed light onto how closely sportsbook prices deviate from their theoretical optima (i.e., those that do not permit positive returns to the bettor).

Importantly, it is not an objective of this paper to propose or analyze the utility of any specific predictors (“features”) or models. Nevertheless, the paper concludes with an attempt to distill the presented theorems into a set of general guidelines to aid the decision making of the bettor.

Problem formulation: “Point spread” betting

For positive s (home team favored), the home team is said to “cover the spread” if m > s , whereas the visiting team has “beat the spread” otherwise. Conversely, for negative s (visiting team favored), the visiting team covers the spread if m < s , and the home team has beat the spread otherwise. The home (visiting) team is said to win “against the spread” if m − s is positive (negative).

Denote the profit (on a unit bet) when correctly wagering on the home and visiting teams by ϕ h and ϕ v , respectively. Assuming a bet size of b placed on the home team, the conventional payout structure is to award the bettor with b (1 + ϕ h ) when m > s . The entire wager is lost otherwise. The total profit π is thus bϕ h when correctly wagering on the home team (− b otherwise). When placing a bet of b on the visiting team, the bettor receives b (1 + ϕ v ) if m < s and 0 otherwise. Typical values of ϕ h and ϕ v are 100/110 ≈ 0.91, corresponding to a commission of 4.5% charged by the sportsbook.

In practice, the event m = s (termed a “push”) may have a non-zero probability and results in all bets being returned. In keeping with the modeling of m by a continuous random variable, here it is assumed that P ( m = s ) = 0. This significantly simplifies the development below. Note also that for fractional spreads (e.g. s = 3.5), the probability of a push is indeed zero.

Wagering to maximize expected profit.

Consider first the question of which team to wager on to maximize the expected profit. As the profit scales linearly with b , a unit bet size is assumed without loss of generality.

Corollary 1 . Assuming equal payouts for home and visiting teams ( ϕ h = ϕ v ), maximization of expected profit is achieved by wagering on the home team if and only if the spread is less than the median margin of victory .

A subtle but important point is that knowledge of which side to bet on for each match is insufficient for maximizing overall profit. The reason is that even if wagering on the side with higher expected profit, it is possible (and in fact quite common, see empirical results below) that the “optimal” wager carries a negative expectation. Thus, an understanding of when wagering should be avoided altogether is required. This is the subject of the theorem below.

It is instructive to consider the conditions above for typical values of ϕ h and ϕ v . When wagering on the home team with ϕ h = 0.91, positive expectation requires the spread to be no larger than the 0.476 quantile of m . When wagering on the visiting team, the spread must exceed the 0.524 quantile. This means that, if the spread is contained within the 0.476-0.524 quantiles of the margin of victory, wagering should be avoided . Practically, it is thus important to obtain estimates of this interval and its proximity to the median score in units of points .

The result of Theorem 2 is reminiscent of the “area of no profitable bet” scenario described in [ 28 ]. Whereas the latter result is presented in terms of outcome probabilities estimated by the bettor and the sportsbook, Theorem 2 here delineates the conditions under which the sportsbook’s point spread assures a negative expectation on the bettor’s side.

Optimal estimation of the margin of victory.

Theorem 3 . Define an “error” as a wager that is placed on the team that loses against the spread. The probability of error is bounded according to : min{ F m ( s ), 1 − F m ( s )} ≤ p (error) ≤ max{ F m ( s ), 1 − F m ( s )}.

The result of Theorem ( 8 ) provides both the best- and worst-case scenario of a given wager. When F m ( s ) is close to 1/2, both the minimum and maximum error rates are near 50%, and wagering is reduced to an event akin to a coin flip. On the other hand, when the true median is far from the spread (i.e., F m ( s ) deviates from 1/2), the minimum and maximum error rates diverge, increasing the highest achievable accuracy of the wager.

Optimality in “moneyline” wagering

Corollary 4 . Define an “error” as a wager that is placed on the team that loses the match outright. The probability of error in moneyline wagering is bounded according to : min{ F m (0), 1 − F m (0)} ≤ p (error) ≤ max{ F m (0), 1 − F m (0)}.

Notice that optimal decision-making in moneyline wagers requires knowledge of quantiles that may be near 0 (if ϕ v ≫ ϕ h ) or near 1 (if ϕ h ≫ ϕ v ). More subtly, the required quantiles will differ for matches that exhibit different payout ratios. For example, a match with two even sides will require knowledge of central quantiles, while a match with a 4:1 favorite will require knowledge of the 80th and 20th percentiles. The implications of this property on quantitative modeling are described in the Discussion .

The moneyline wagering considered in this section is a two-alternative bet that is popular in North American sports. In European betting markets, the most common type of wager is the three-alternative “Home-Draw-Away” bet where there is no point spread and the task of the bettor is to forecast one of the three potential outcomes: m > 0, m = 0, or m < 0, each of which are endowed with a payout (see, for example, [ 26 , 29 , 30 ]). Clearly the the probability p ( m = 0) will be non-zero in this context. As a result, the methodology here, which models m by a continuous random variable, cannot be straightforwardly applied to the case of the Home-Draw-Away bet. The extension of the present findings to the case of multi-way bets with discrete m is a potential topic of future research.

Optimality in “over-under” betting

The following two results may be proven by replacing m with τ , ϕ h with ϕ o , and ϕ v with ϕ u in the Proofs of Theorems 1 and 2, respectively.

In the special case of ϕ o = ϕ u , one should bet on the over only if and only if the sportsbook total τ falls below the median of t .

Define F t ( τ ) as the CDF of the true point total evaluated at the sportsbook’s proposed total. The following corollary may be proven by following the Proof of Theorem 3.

Corollary 8 . Define an “error” in over-under betting as a wager that is placed on the “over” when t < τ or on the “under” when t > τ. The probability of error is bounded according to : min{ F t ( τ ), 1 − F t ( τ )} ≤ p (error) ≤ max{ F t ( τ ), 1 − F t ( τ )}.

Empirical results from the National Football League

In order to connect the theory to a real-world betting market, empirical analyses utilizing historical data from the National Football League (NFL) were conducted. The margins of victory, point totals, sportsbook point spreads, and sportsbook point totals were obtained for all regular season matches occurring between the 2002 and 2022 seasons ( n = 5412). The mean margin of victory was 2.19 ± 14.68, while the mean point spread was 2.21 ± 5.97. The mean point total was 44.43 ± 14.13, while the mean sportsbook total was 43.80 ± 4.80. The standard deviation of the margin of victory is nearly 7x the mean, indicating a high level of dispersion in the margin of victory, perhaps due to the presence of outliers. Note that the standard deviation of a random variable provides an upper bound on the distance between its mean and median [ 31 ], which is relevant to the problem at hand.

To estimate the distribution of the margin of victory for individual matches, the point spread s was employed as a surrogate for θ . The underlying assumption is that matches with an identical point spread exhibit margins of victory drawn from the same distribution. Observations were stratified into 21 groups ranging from s o = −7 to s o = 10. This procedure was repeated for the analysis of point totals, where observations were stratified into 24 groups ranging from t o = 37 to t o = 49.

How accurately do sportsbooks capture the median outcome?

It is important to gain insight into how accurately the point spreads proposed by sportsbooks capture the median margin of victory. For each stratified sample of matches, the median margin of victory was computed and compared to the sample’s point spread. The distribution of margin of victory for matches with a point spread s o = 6 is shown in Fig 1a , where the sample median of 4.34 (95% confidence interval [2.41,6.33]; median computed with kernel density estimation to overcome the discreteness of the margin of victory; confidence interval computed with the bootstrap) is lower than the sportsbook point spread. However, the sportsbook value is contained within the 95% confidence interval.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

( a ) The distribution of margin of victory for National Football League matches with a consensus sportsbook point spread of s = 6. The median outcome of 4.26 (dashed orange line, computed with kernel density estimation) fell below the sportsbook point spread (dashed blue line). However, the 95% confidence interval of the sample median (2.27-6.38) contained the sportsbook proposition of 6. ( b ) Same as (a), but now showing the distribution of point total for all matches with a sportsbook point total of 46. Although the sportsbook total exceeded the median outcome by approximately 1.5 points, the confidence interval of the sample median (42.25-46.81) contained the sportsbook’s proposition. ( c ) Combining all stratified samples, the sportsbook’s point spread explained 86% of the variability in the median margin of victory. The confidence intervals of the regression line’s slope and intercept included their respective null hypothesis values of 1 and 0, respectively. ( d ) The sportsbook point total explained 79% of the variability in the median total. Although the data hints at an overestimation of high totals and underestimation of low totals, the confidence intervals of the slope and intercept contained the null hypothesis values.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0287601.g001

Aggregating across stratified samples, the sportsbook point spread explained 86% of the variability in the true median margin of victory ( r 2 = 0.86, n = 21; Fig 1c ). Both the slope (0.93, 95% confidence interval [0.81,1.04]) and intercept (-0.41, 95% confidence interval [-1.03,0.16]) of the ordinary least squares (OLS) line of best fit (dashed blue line) indicate a slight overestimation of the margin of victory by the point spread. This is most apparent for positive spreads (i.e., a home favorite). Nevertheless, the confidence intervals of both the slope and intercept did include the null hypothesis values of 1 and 0, respectively. The data for all sportsbook point spreads with at least 100 matches is provided in Table 1 .

Regular season matches from the National Football League occurring between 2002-2022 were stratified according to their sportsbook point spread. Each set of 3 grouped rows corresponds to a subsample of matches with a common sportsbook point spread. The “level” column indicates whether the row pertains to the 95% confidence interval (0.025 and 0.975 quantiles) or the mean value across bootstrap resamples. The dependent variables include the 0.476, 0.5, and 0.524 quantiles, as well as the expected profit of wagering on the side with higher likelihood of winning the bet for hypothetical point spreads that deviate from the median outcome by 1, 2, and 3 points, respectively.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0287601.t001

The distribution of observed point totals for matches with a sportsbook total of τ = 46 is shown in Fig 1b , where the computed median of 44.45 (95% confidence interval [42.25,46.81]) is suggestive of a slight overestimation of the true total. Combining data from all samples, the sportsbook point total explained 79% of the variability in the median point total ( r 2 = 0.79, n = 24; Fig 1d ).

Interestingly, the data hints at the sportsbook’s proposed point total underestimating the true total for relatively low totals (i.e., black line is below the blue for sportsbook totals below 43), while overestimating the total for those matches expected to exhibit high scoring (i.e., black line is above the blue line for sportsbook totals above 43). Note, however, that the confidence intervals of the regression line (slope: [0.72,1.02], intercept: [-1.14, 12.05]) did contain the null hypothesis values. The data for all sportsbook point total with at least 100 samples is provided in Table 2 .

Matches were stratified into 24 subsamples defined by the value of the sportsbook total. The dependent variables are the 0.476, 0.5, and 0.524 quantiles of the true point total, as well as the expected profit of wagering conditioned on the amount of bias in the sportsbook’s total.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0287601.t002

Do sportsbook estimates deviate from the 0.476-0.524 interval?

In the common case of ϕ = 0.91, a positive expected profit is only feasible if the point spread (or point total) is either below the 0.476 or above the 0.524 quantiles of the outcome’s distribution. It is thus interesting to consider how often this may occur in a large betting market such as the NFL. To that end, the 0.476 and 0.524 quantiles of the margin of victory were estimated in each stratified sample (horizontal bars in Fig 2 ; the point spread is indicated with an orange marker; all quantiles are listed in Table 1 ).

With a standard payout of ϕ = 0.91, achieving a positive expected profit is only feasible if the sportsbook point spread falls outside of the 0.476-0.524 quantiles of the margin of victory. The 0.476 and 0.524 quantiles were thus estimated for each stratified sample of NFL matches. Light (dark) black bars indicate the 95% confidence intervals of the 0.476 (0.524) quantiles. Orange markers indicate the sportsbook point spread, which fell within the quantile confidence intervals for the large majority of stratifications. An exception was s = 5, where the sportsbook appeared to overestimate the margin of victory. For two other stratifications ( s = 3 and s = 10), the 0.524 quantile tended to underestimate the sportsbook spread, with the 95% confidence intervals extending to just above the spread.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0287601.g002

For the majority of samples, the confidence intervals of the 0.476 and 0.524 quantiles contained the sportsbook spread. One exception was the spread s = 5, where the margin of victory fell below the sportsbook value (95% confidence interval of the 0.524 quantile: [0.87,4.85]). The margin of victory for s = 3 (95% confidence interval of the 0.524 quantile: [0.78,3.08]) and s = 10 (95% confidence interval of the 0.524 quantile: [6.42,10.06]) also tended to underestimate the sportsbook spread, with the confidence intervals just containing the sportsbook value.

The analysis was repeated for point totals ( Fig 3 , all quantiles listed in Table 2 ). All but one stratified sample exhibited 0.476 and 0.524 quantiles whose confidence intervals contained the sportsbook total ( t = 47, [41.59, 45.42]). Examination of the sample quantiles suggests that NFL sportsbooks are very adept at proposing point totals that fall within 2.4 percentiles of the median outcome.

The 0.476 and 0.524 quantiles of the true point total were estimated for each stratified sample of NFL matches. For all but one stratification ( t = 47, 95% confidence interval [41.59-45.42], sportsbook overestimates the total), the confidence intervals of the sample quantiles contained the sportsbook proposition. Visual inspection of the data suggests that, in the NFL betting market at least, sportsbooks are very adept at proposing totals that fall within the critical 0.476-0.524 quantiles.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0287601.g003

How large of a discrepancy from the median is required for profit?

In practice, it is desirable to have an understanding of how large of a sportsbook bias, in units of points, is required to permit a positive expected profit. To address this, the value of the empirically measured CDF of the margin of victory was evaluated at offsets of 1, 2, and 3 points from the true median in each direction. The resulting value was then converted into the expected value of profit (see Materials and Methods ). The computation was performed separately within each stratified sample, and the height of each bar in Fig 4 indicates the hypothetical expected profit of a unit bet when wagering on the team with the higher probability of winning against the spread . For the sake of clarity, only the four largest samples ( s ∈ {−3, 2.5, 3, 7}) are shown in the Figure, with data for all samples listed in Table 1 .

In order to estimate the magnitude of the deviation between sportsbook point spread and median margin of victory that is required to permit a positive profit to the bettor, the hypothetical expected profit was computed for point spreads that differ from the true median by 1, 2, and 3 points in each direction. The analysis was performed separately within each stratified sample, and the figure shows the results of the four largest samples. For 3 of the 4 stratifications, a sportsbook bias of only a single point is required to permit a positive expected return (height of the bar indicates the expected profit of a unit bet assuming that the bettor wagers on the side with the higher probability of winning; error bars indicate the 95% confidence intervals as computed with the bootstrap). For a sportsbook spread of s = 3 (dark black bars), the expected profit on a unit bet is 0.021 [0.008-0.035], 0.094 [0.067-0.119], and 0.166 [0.13-0.2] when the sportsbook’s bias is +1, +2, and +3 points, respectively (mean and confidence interval over 500 bootstrap resamples).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0287601.g004

The expected profit is negative (i.e., ( ϕ − 1)/2 = −0.045) when the spread equals the median (center column). Interestingly however, for 3 of the 4 largest stratified samples, a positive profit is achievable with only a single point deviation from the median in either direction (the confidence intervals indicated by error bars do not extend into negative values). Averaged across all n = 21 stratifications, the expected profit of a unit bet is 0.022 ± 0.011, 0.090 ± 0.021, and 0.15 ± 0.030 when the spread exceeds the median by 1, 2, and 3 points, respectively (mean ± standard deviation over n = 21 stratifications, each of which is an average over 1000 bootstrap ensembles). Similarly, the expected return is 0.023 ± 0.013, 0.089 ± 0.026, and 0.15 ± 0.037 when the spread undershoots the median by 1, 2, and 3 points respectively. This indicates that sportsbooks must estimate the median outcome with high precision in order to prevent the possibility of positive returns.

The analysis was repeated on the data of point totals. A deviation from the true median of only 1 point was sufficient to permit a positive expected profit in all four of the largest stratifications ( Fig 5 ; t ∈ {41, 43, 44, 45}; error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals; data for all samples is provided in Table 2 ). When the sportsbook overestimates the median total by 1, 2, and 3 points, the expected profit on a unit bet is 0.014 ± 0.0071, 0.073 ± 0.014, and 0.13 ± 0.020, respectively (mean ± standard deviation over n = 24 samples, each of which is a average over 1000 bootstrap resamples). When the sportsbook underestimates the median, the expected profit on a unit bet is 0.015±0.0071, 0.076± 0.014, and 0.14± 0.020, for deviations of 1, 2, and 3 points, respectively. Note that despite the dependent variable having a larger magnitude (compared to margin of victory), the required sportsbook error to permit positive profit is the same as shown by the analysis of point spreads.

Vertical axis depicts the expected profit of an over-under wager, conditioned on the sportsbook’s posted total deviating from the true margin by a value of 1, 2, or 3 points (horizontal axis). The analysis was performed separately for each unique sportsbook total, and the figure displays the results for the four largest samples. A deviation from the true median of a single point permits a positive expected profit in all four of the depicted groups. For a sportsbook total of t = 44 (green bars), the expected profit on a unit bet is 0.015 [0.004-0.028], 0.075 [0.053-0.10], and 0.13 [0.10-0.17] when the sportsbook’s bias is +1, +2, and +3 points, respectively (mean and confidence interval over 500 bootstrap resamples).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0287601.g005

The theoretical results presented here, despite seemingly straightforward, have eluded explication in the literature. The central message is that optimal wagering on sports requires accurate estimation of the outcome variable’s quantiles. For the two most common types of bets—point spread and point total—estimation of the 0.476, 0.5 (median), and 0.524 quantiles constitutes the primary task of the bettor (assuming a standard commission of 4.5%). For a given match, the bettor must compare the estimated quantiles to the sportsbook’s proposed value, and first decide whether or not to wager ( Theorem 2 ), and if so, on which side ( Theorem 1 ).

The sportsbook’s proposed spread (or point total) effectively delineates the potential outcomes for the bettor ( Theorem 3 ). For a standard commission of 4.5%, the result is that if the sportsbook produces an estimate within 2.4 percentiles of the true median outcome, wagering always yields a negative expected profit— even if consistently wagering on the side with the higher probability of winning the bet . This finding underscores the importance of not wagering on matches in which the sportsbook has accurately captured the median outcome with their proposition. In such matches, the minimum error rate is lower bounded by 47.6%, the maximum error rate is upper bounded by 52.4%, and the excess error rate ( Theorem 4 ) is upper bounded by 4.8%.

The seminal findings of Kuypers [ 13 ] and Levitt [ 23 ], however, imply that sportsbooks may sometimes deliberately propose values that deviate from their estimated median to entice a preponderance of bets on the side that maximizes excess error. For example, by proposing a point spread that exaggerates the median margin of victory of a home favorite, the minimum error rate may become, for example, 45% (when wagering on the road team), and the excess error rate when wagering on the home team is 10%. In this hypothetical scenario, the sportsbook may predict that, due to the public’s bias for home favorites, a majority of the bets will be placed on the home team. The empirical data presented here hint at this phenomenon, and are in alignment with previous reports of market inefficiencies in the NFL betting market [ 5 , 32 – 35 ]. Namely, the sportsbook point spread was found to slightly overestimate the median margin of victory for some subsets of the data ( Fig 2 ). Indeed, the stratifications showing this trend were home favorites, agreeing with the idea that the sportsbooks are exploiting the public’s bias for wagering on the favorite [ 23 ].

The analysis of sportsbook point spreads performed here indicates that only a single point deviation from the true median is sufficient to allow one of the betting options to yield a positive expectation. On the other hand, realization of this potential profit requires that the bettor correctly, and systematically, identify the side with the higher probability of winning against the spread. Forecasting the outcomes of sports matches against the spread has been elusive for both experts and models [ 6 , 36 ]. Due to the abundance of historical data and user-friendly statistical software packages, the employment of quantitative modeling to aid decision-making in sports wagering [ 37 ] is strongly encouraged. The following suggestions are aimed at guiding model-driven efforts to forecast sports outcomes.

The argument against binary classification for sports wagering

The minimum error and minimum excess error rates defined in Theorems 3 and 4, respectively, are analogous to the Bayes’ minimum risk and Bayes’ excess risk in binary classification [ 38 ]. Indeed, one can cast the estimation of margin of victory in sports wagering as a binary classification problem, aiming to predict the event of “the home team winning against the spread”. Here this approach is not advocated. In conventional binary classification, the target variable (or “class label”) is static and assumed to represent some phenomenon (e.g. presence or absence of an object). In the context of sports wagering, however, the event m > s need not be uniform for different matches. For example, the event of a large home favorite winning against the spread may differ qualitatively from that of a small home “underdog” winning against the spread. Moreover, the sportsbook’s proposed point spread is a dynamic quantity. To illustrate the potential difficulty of utilizing classifiers in sports wagering, consider the case of a match with a posted spread of s = 4, where the goal is to predict the sign of m − 4. But now imagine that the the spread moves to s = 3. The resulting binary classification problem is now to predict the sign of m − 3, and it is not straightforward to adapt the previously constructed classifier to this new problem setting. One may be tempted to modify the bias term of the classifier, but it is unclear by how much it should be adjusted, and also whether a threshold adjustment is in fact the optimal approach in this scenario. On the other hand, by posing the problem as a regression, it is trivial to adapt one’s optimal decision: the output of the regression can simply be compared to the new spread.

The case for quantile regression

Conventional ordinary least-squares (OLS) regression yields estimates of the mean of a random variable, conditioned on the predictors. This is achieved by minimizing the mean squared error between the predicted and target variable.

The findings presented here suggest that conventional regression may be a sub-optimal approach to guiding wagering decisions, whose optimality relies on knowledge of the median and other quantiles. The presence of outliers and multi-modal distributions, as may be expected in sports outcomes, increases the deviation between the mean and median of a random variable. In this case, the dependent variable of conventional regression is distinct from the median and thus less relevant to the decision-making of the sports bettor. The significance of this may be exacerbated by the high noise level on the target random variable, and the low ceiling on model accuracy that this imposes.

Therefore, a more suitable approach to quantitative modeling in sports wagering is to employ quantile regression, which estimates a random variable’s quantiles by minimizing the quantile loss function [ 39 ]. Any features that are expected to forecast sports outcomes could be provided as the predictors in a quantile regression to produce estimates that are aligned with the bettor’s objectives: to avoid wagering on matches with negative expectation for both outcomes, and to wager on the side with zero excess error.

Potential challenges in moneyline wagering

Bias-variance in sports wagering

The view that low variance implies “simple” models has recently been challenged in the context of artificial neural networks [ 41 ]. Nevertheless, the desire for low-variance, high-bias modeling in sports wagering does suggest the preference for simpler models. Thus, it is advocated to employ a limited set of predictors and a limited capacity of the model architecture. This is expected to translate to improved generalization to future data.

Sport-specific considerations

The three types of wagers considered in this work—point spread, moneyline, and over-under—are the most popular bet types in North American sports. The empirical analysis employed data from the National Football League (NFL). One unique aspect of American football is its scoring system, in which the points accumulated by each team increase primarily in increments of 3 or 7 points. The structure of the scoring imposes constraints on the distribution of the margin of victory m . For example, in American Football, the distribution of the margin of victory is expected to exhibit local maxima near values such as: ±3, ±7, ±10. In the case of games in the National Basketball Association (NBA), the most common margins of victory tend to occur in the 5-10 interval, reflecting the overall higher point totals in basketball and its most common point increments (2 and 3). As a result, the shape and quantiles of the distribution of m may vary qualitatively between the NBA and NFL.

As a final illustrative example of the importance of the quantiles of m , consider the hypothetical scenario of two American football teams playing a match whose parameters θ have been exactly matched three times previously. In those past matches, the outcomes were m = 3, m = 7, and m = 35. In this fictitious example, the median is 7 but the mean is 15. Now imagine that the point spread for the next match has been set to s = 10 (home team favored to win the match by 10 points). Assuming that one has committed to wagering on the match, the optimal decision is to bet on the visiting team, despite that fact that the home team has won the previous matches by an average of 15 points.

Materials and methods

All analysis was performed with custom Python code compiled into a Jupyter Notebook (available at https://github.com/dmochow/optimal_betting_theory ). The figures and tables in this manuscript may be reproduced by executing the notebook.

Empirical data

Historical data from the National Football League (NFL) was obtained from bettingdata.com , who has courteously permitted the data to be shared on the repository listed above. All regular season matches from 2002 to 2022 were included in the analysis ( n = 5412). The data set includes point spreads and point totals (with associated payouts) from a variety of sportsbooks, as well as a “consensus” value. The latter was utilized for all analysis.

Data stratification

In order to estimate quantiles of the distributions of margin of victory and point totals from heterogeneous data (i.e., matches with disparate relative strengths of the home and visiting teams), the sportsbook point spread and sportsbook point total were used as a surrogate for the parameter vector defining the identity of each individual match ( θ in the text). This permitted the estimation of the 0.476, 0.5, and 0.524 quantiles over subsets of congruent matches.

Only spreads or totals with at least 100 matches in the dataset were included, such that estimation of the median would be sufficiently reliable. To that end, data was stratified into 21 samples for the analysis of margin of victory: {-7, -6, -3.5, -3, -2.5, -2, -1, 1, 2, 2.5, 3, 3.5, 4, 4.5, 5, 5.5, 6, 6.5, 7, 7.5, 10) and 24 samples for the analysis of point totals (37, 37.5, 38, 39, 39.5, 40, 40.5, 41, 41.5, 42, 42.5, 43, 43.5, 44, 44.5, 45, 45.5, 46, 46.5, 47, 47.5, 48, 48.5, 49 }. This resulted in the employment of n = 3843 matches in the analysis of point spreads and n = 4300 matches in the analysis of point totals.

Note that the stratification process did not account for varying payouts, for example −110 versus −105 in the American odds system, as this would greatly increase the number of stratified samples while decreasing the number of matches in each sample. It is likely that the resulting error is negligible, however, due to the likelihood of the payout discrepancy being fairly balanced across the home and visiting teams.

Median estimation

In order to overcome the discrete nature of the margins of victory and point totals, kernel density estimation was employed to produce continuous quantile estimates. The KernelDensity function from the scikit-learn software library was employed with a Gaussian kernel and a bandwidth parameter of 2. For the margin of victory, the density was estimated over 4000 points ranging from -40 to 40. For the analysis of point totals, the density was estimated over 4000 points ranging from 10 to 90. The regression analysis relating median outcome to sportsbook estimates ( Fig 1 ) was performed with ordinary least squares (OLS).

Confidence interval estimation

In order to generate variability estimates for the 0.476, 0.5, and 0.524 quantiles of the margin of victory and point total, the bootstrap [ 42 ] technique was employed. 1000 resamples of the same size as the original sample were generated in each case. The confidence intervals were then constructed as the interval between the 2.5 and 97.5 percentiles of the relevant quantity. Bootstrap resampling was also employed to derive confidence intervals on the regression parameters relating the median outcomes to sportsbook spreads or totals ( Fig 1 ), as well as the confidence intervals on the expected profit of wagering conditioned on a fixed sportsbook bias (Figs 4 and 5 ).

Expected profit estimation

To model the idealized case of always placing the wager on the side with the higher probability of winning against the spread, the reported expected profit was taken as the maximum of the two expected values in ( 15 ). The analogous procedure was conducted for the analysis of point totals.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Ed Miller and Mark Broadie for fruitful discussions during the preparation of the manuscript. The author would also like to acknowledge the effort of the reviewers, in particular Fabian Wunderlich, for providing many helpful comments and critiques throughout peer review.

- View Article

- PubMed/NCBI

- Google Scholar

- 2. Bloomberg Media. Sports Betting Market Size Worth $140.26 Billion By 2028: Grand View Research, Inc.; 2021. Available from: https://www.bloomberg.com/press-releases/2021-10-19/sports-betting-market-size-worth-140-26-billion-by-2028-grand-view-research-inc .

- 21. Glickman ME, Stern HS. A state-space model for National Football League scores. In: Anthology of statistics in sports. SIAM; 2005. p. 23–33.

- 38. Devroye L, Györfi L, Lugosi G. A probabilistic theory of pattern recognition. vol. 31. Springer Science & Business Media; 2013.

- 39. Koenker R, Chernozhukov V, He X, Peng L. Handbook of quantile regression. 2017;.

- 41. Neal B, Mittal S, Baratin A, Tantia V, Scicluna M, Lacoste-Julien S, et al. A modern take on the bias-variance tradeoff in neural networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:181008591. 2018;.

- Follow us on Facebook

- Follow us on Twitter

- Criminal Justice

- Environment

- Politics & Government

- Race & Gender

Expert Commentary

Sports betting in the US: A research roundup and explainer

We look at the landscape of legal sports betting in America, explain what the research says about how legalization affects tax revenues, and provide a brief history of the activity.

Republish this article

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License .

by Clark Merrefield, The Journalist's Resource October 25, 2022

This <a target="_blank" href="https://journalistsresource.org/economics/sports-betting-research-roundup-explainer/">article</a> first appeared on <a target="_blank" href="https://journalistsresource.org">The Journalist's Resource</a> and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.<img src="https://journalistsresource.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/cropped-jr-favicon-150x150.png" style="width:1em;height:1em;margin-left:10px;">

On Nov. 8, Californians will vote on two ballot measures that would allow for different forms of sports betting in the state.

Proposition 26 would allow sports betting at licensed casinos and horse tracks on tribal lands and run by federally recognized Native American tribes.

Prop. 27 would allow tribes licensed to offer gambling and major gaming companies to offer online sports betting. These companies include FanDuel and DraftKings, which together make up roughly two-thirds of the U.S. online sports betting market.

“If both pass, they might both go into effect or the result could be decided in court, depending on which one gets more yes votes,” writes CalMatters economics reporter Grace Gedye in an article from June.

Although California is the only state with sports betting on the midterm ballot , it’s not the only state where sports betting is a topic of political discussion — and relevant for journalists across beats to understand. For example, Georgia gubernatorial candidate Stacey Abrams recently expressed support for legalized sports betting in her state. Abrams’ opponent, Gov. Brian Kemp, is opposed.

In Missouri, state lawmakers from both parties support legalizing sports betting , but Gov. Mike Parson is hesitant. Vermont lawmakers are considering taking up a sports betting bill during the next legislative session. Gubernatorial candidates in South Carolina and Texas support legal sports betting. In Florida, there is an ongoing lawsuit over whether the state should be allowed to give the Seminole Tribe the exclusive right to run online sports betting there.

Legal sports wagering in the U.S. has grown vertically in recent years — from less than $5 billion worth of bets placed in 2018 to $57 billion in 2021 — despite sports betting remaining illegal in nearly half of states. Sportsbooks, the entities that take sports bets, bring in about $4 billion yearly after wagers are settled.

The reason for this growth: a May 2018 Supreme Court ruling. Justice Samuel Alito, in delivering the 6-3 decision , reasoned that 1992 federal legislation banning states from allowing sports betting was unconstitutional.

Under the 1992 law, the Professional and Amateur Sports Protection Act, the federal government did not “make sports gambling itself federal crime,” Alito writes in the 2018 decision. “Instead, it allows the [U.S.] Attorney General, as well as professional and amateur sports organizations, to bring civil actions to enjoin violations.” Other than legislative powers the Constitution grants Congress, the federal government cannot “issue direct orders to state legislatures,” Alito writes. The majority interpreted the Professional and Amateur Sports Protection Act as doing so.

Here is how John Holden , an assistant professor of business at Oklahoma State University who has written extensively on sports gambling, explains the 2018 ruling:

“If the federal government wants to make sports betting illegal, they’re free to do so, but they can use the [Federal Bureau of Investigation] and the [Department of Justice] to enforce that,” Holden says. “They can’t tell a state legislature that you need to keep that law on the books and use your state police to go out and bust up gambling rings.”

A fundraising breakdown from the Los Angeles Times shows about $132 million has been raised to support Prop. 26, with about $43 million in opposition funding. Top backers include the Federated Indians of Graton Rancheria, the Pechanga Band of Indians and the Yocha Dehe Wintun Nation. Non-Native American casino and gaming interests are largely opposed — conversely, they have backed Prop. 27, which would open up sports betting to all gambling interests, not just Native American-run casinos.

Tribal gaming brings in nearly $40 billion a year across all tribes that operate gambling enterprises, according to the National Indian Gaming Commission . “Gaming operations have had a far-reaching and transformative effect on American Indian reservations and their economies,” write the authors of a 2015 paper about how the act affected tribal economic development. “Specifically, Indian gaming has allowed marked improvements in several important dimensions of reservation life.”

The landscape of legal sports betting

If California legalizes sports betting, it would represent a major coup for gaming interests in the state. In California, the most populous state, horse racing is the only legal form of sports betting.

Sports wagering is legal in 28 states plus the District of Columbia, according to a recent Washington Post analysis. Seven states prohibit online sports betting and only allow in-person wagers at licensed locations, such as casinos: Delaware, Maryland, Mississippi, Montana, New Mexico, North Carolina and North Dakota. Sports betting is legal but pending rollout in four states: Maine, Massachusetts, Nebraska and Ohio. Kansas is the most recent state to implement legal in-person and online sports gambling, as of Sept. 1.

States place a range of licensing fees on operators and tax rates on sports betting revenue, from a low of 6.75% in Nevada and Iowa to a high of 51% in New Hampshire and New York. States use tax revenues for a variety of purposes . Some, like Delaware, put sports wagering taxes toward their general fund. Colorado uses sports betting taxes to pay for its statewide water plan, Illinois funds transportation infrastructure and New York funds education programs.

In states where sports betting is legal, bettors can wager on nearly any major sporting event, both professional and amateur. For example, bettors can wager on the outcome of a baseball game, as well as events within the game, such as whether a particular player will hit a home run.

Polling indicates California may be unlikely to join the legal betting club. CalMatters reported earlier this month that despite various campaigns raising more than $440 million in marketing related to Props. 26 and 27, each measure is garnering support from less than a third of likely voters, according to October polling from the Institute of Governmental Studies at the University of California, Berkeley.

Below, we explore recent research on sports betting. Among the findings of the seven studies featured here:

- Sports bettors are more likely to be white, male, and exhibit psychological traits consistent with narcissism.

- Tax revenue from sports betting may appear substantial in raw numbers, but the impact on tax coffers is muted when compared with income and sales taxes, or tax revenue from other gambling offerings.

- Evidence is mixed as to whether introducing sports betting cannibalizes — eats away at — revenue from other types of gambling.

- Some college football referees may more heavily penalize betting favorites.

The nonprofit National Council on Problem Gambling estimates as many as 8 million adults in the U.S. may have a mild, moderate or severe gambling problem. However, there is a lack of comprehensive, recent academic research on the extent of gambling addiction in the U.S., and the societal costs.

If you feel you may have a problem with gambling you can get help from the National Council on Problem Gambling by call or text at 1-800-522-4700, or online chat at ncpgambling.org/chat .

Research roundup

The Income Elasticity of Gross Sports Betting Revenues in Nevada: Short-Run and Long-Run Estimates Ege Can and Mark Nichols. Journal of Sports Economics, October 2021.

The study: The authors analyze quarterly sports betting data from Nevada covering 1990 to 2019, to explore whether sports betting might be a viable tax revenue stream for other states. Sports betting has been legal in Nevada for decades, so it is the only state with long-run data that can potentially provide insight on the tax base future in states that have legalized sports betting since 2018. The authors note that Nevada is a “mature” market for sports betting, meaning industry growth is relatively stable year to year. A state that newly legalizes sports gambling is likely to see an immediate jump in sports betting revenue, with industry growth levelling off over time.

The findings: In the short-run, quarter-to-quarter, the rise and fall of sports betting revenue in Nevada is most closely tied to changing sports seasons. The authors suggest this is due to differences in how much bettors wager on various sports — the NFL, for example, is “the most popular sport to place wagers on,” with revenues rising and falling as an NFL season begins and ends. In the long run, taxable income in the state and sports betting revenues tend to grow at similar rates. Sports betting revenue in Nevada is a small fraction of revenues from other sources.

The authors write: “Total sports betting revenue in Nevada, the amount kept by the casinos, was $329 million in 2019, implying $22.2 million in tax revenue for the state. In contrast, casino gambling in Nevada in 2019 was $12 billion, generating $810 million in tax revenue. Sports betting is a gambling activity where the amount retained by the casino, and consequently retained by the state, is relatively small as most of the money from losing bets is transferred to those with winning bets. Therefore, sports gambling is a smaller contributor to tax coffers compared to more traditional tax sources such as income and taxable sales or, if applicable, casino revenue.”

A Comparative Analysis of Sports Gambling in the United States Brendan Dwyer, Ted Hayduk III and Joris Drayer. International Journal of Sports Marketing and Sponsorship, August 2022.

The study: The authors explore whether there are psychological differences between bettors and those who do not bet, as well as differences in how closely bettors identify with social institutions, such as religious organizations and far-right or far-left politics.

The authors surveyed 377 bettors and 402 non-betting sports fans from 47 states and explored differences between bettors and non-bettors in states with legal gambling and states where gambling is banned. They also asked about narcissism, which past research has found “is associated to gambling behavior especially as it relates to risky behavior such as participating in illegal gambling,” the authors write. Bettors in the sample were 81% male, compared with 69% of non-bettors. Among bettors, 64% were white and 27% were Black, while 77% of non-bettors were white and 17% were Black.

The findings: In legal gambling states, bettors felt more self-worth than non-bettors, though in states where gambling is illegal the difference in self-worth was almost nil. In legal gambling states, bettors reported a stronger personal identity, “or the importance with which an individual identifies with their relationship and career,” than non-bettors. This relationship flipped in illegal gambling states, with non-bettors showing a stronger personal identity than bettors. In both illegal and legal gambling states, bettors reported slightly higher levels of social uselessness — “an individual’s perceived lack of worth related to social institutions” — than non-bettors, though the gap was wider in illegal gambling states.

The authors write: “Bettors look different and come from different backgrounds and locations. Psychographically, they were clearly more narcissistic. They also indicated a higher social identity and self-worth, yet perceived themselves as less worthy members of important social institutions. In general, sports bettors out consumed non-bettors as it relates sports spectatorship.”

Game Changing Innovation or Bad Beat? How Sports Betting Can Reduce Fan Engagement Ashley Stadler Blank, Katherine Loveland, David Houghton. Journal of Business Research, June 2021.