Information Systems Research

Relevant Theory and Informed Practice

- © 2004

- Bonnie Kaplan 0 ,

- Duane P. Truex 1 ,

- David Wastell 2 ,

- A. Trevor Wood-Harper 3 ,

- Janice I. DeGross 4

Yale University, USA

You can also search for this editor in PubMed Google Scholar

Florida International University, USA Georgia State University, USA

University of Manchester, UK

University of Manchester, UK University of South Australia, Australia

University of Minnesota, USA

Part of the book series: IFIP Advances in Information and Communication Technology (IFIPAICT, volume 143)

122k Accesses

410 Citations

54 Altmetric

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this book

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Other ways to access

Licence this eBook for your library

Institutional subscriptions

About this book

Similar content being viewed by others.

Retrospect and prospect: information systems research in the last and next 25 years

Introduction

Introduction: Why Theory? (Mis)Understanding the Context and Rationale

- Enterprise Resource Planning

- development

- e-government

- information processing

- information system

- information technology

- linear optimization

- organization

- service-oriented computing

Table of contents (51 chapters)

Front matter, young turks, old guardsmen, and the conundrum of the broken mold: a progress report on twenty years of information systems research.

- Bonnie Kaplan, Duane P. Truex III, David Wastell, A. Trevor Wood-Harper

Doctor of Philosophy, Heal Thyself

- Allen S. Lee

Information Systems in Organizations and Society: Speculating on the Next 25 Years of Research

- Steve Sawyer, Kevin Crowston

Information Systems Research as Design: Identity, Process, and Narrative

- Richard J. Boland Jr., Kalle Lyytinen

Reflections on the IS Discipline

Information systems— a cyborg discipline.

- Magnus Ramage

Cores and Definitions: Building the Cognitive Legitimacy of the Information Systems Discipline Across the Atlantic

- Frantz Rowe, Duane P. Truex III, Lynette Kvasny

Truth, Journals, and Politics: The Case of the MIS Quarterly

- Lucas Introna, Louise Whittaker

Debatable Advice and Inconsistent Evidence: Methodology in Information Systems Research

- Matthew R. Jones

The Crisis of Relevance and the Relevance of Crisis: Renegotiating Critique in Information Systems Scholarship

- Teresa Marcon, Mike Chiasson, Abhijit Gopal

Whatever Happened to Information Systems Ethics?

- Frances Bell, Alison Adam

Supporting Engineering of Information Systems in Emergent Organizations

- Sandeep Purao, Duane P. Truex III

Critical Interpretive Studies

The choice of critical information systems research.

- Debra Howcroft, Eileen M. Trauth

The Research Approach and Methodology Used in an Interpretive Study of a Web Information System: Contextualizing Practice

- Anita Greenhill

Applying Habermas’ Validity Claims as a Standard for Critical Discourse Analysis

- Wendy Cukier, Robert Bauer, Catherine Middleton

Conducting Critical Research in Information Systems: Can Actor-Network Theory Help?

Conducting and evaluating critical interpretive research: examining criteria as a key component in building a research tradition.

- Marlei Pozzebon

Editors and Affiliations

Bonnie Kaplan

Florida International University, USA

Duane P. Truex

Georgia State University, USA

David Wastell, A. Trevor Wood-Harper

University of South Australia, Australia

A. Trevor Wood-Harper

Janice I. DeGross

Bibliographic Information

Book Title : Information Systems Research

Book Subtitle : Relevant Theory and Informed Practice

Editors : Bonnie Kaplan, Duane P. Truex, David Wastell, A. Trevor Wood-Harper, Janice I. DeGross

Series Title : IFIP Advances in Information and Communication Technology

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/b115738

Publisher : Springer New York, NY

eBook Packages : Springer Book Archive

Copyright Information : IFIP International Federation for Information Processing 2004

Hardcover ISBN : 978-1-4020-8094-4 Published: 30 June 2004

Softcover ISBN : 978-1-4419-5474-9 Published: 08 December 2010

eBook ISBN : 978-1-4020-8095-1 Published: 11 April 2006

Series ISSN : 1868-4238

Series E-ISSN : 1868-422X

Edition Number : 1

Number of Pages : XXIV, 744

Topics : Business Mathematics , Management of Computing and Information Systems , IT in Business , Business and Management, general , Management , Mechanical Engineering

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Elsevier - PMC COVID-19 Collection

Viewpoint: Information systems research strategy

This article 1 , 2 has two aligned aims: (i) to espouse the value of a strategic research orientation for the Information Systems Discipline; and (ii) to facilitate such a strategic orientation by recognising the value of programmatic research and promoting the publication of such work. It commences from the viewpoint that Information Systems (IS) research benefits from being strategic at every level, from individual researcher, to research program, to research discipline and beyond. It particularly advocates for more coordinated programs of research emphasising real-world impact, while recognising that vibrant, individual-driven and small-team research within broad areas of promise, is expected to continue forming the core of the IS research ecosystem. Thus, the overarching aim is the amplification of strategic thinking in IS research – the further leveraging of an orientation natural to the JSIS community, with emphasis on research programs as a main strategic lever, and further considering how JSIS can be instrumental in this aim.

Introduction

This article is motivated by the viewpoint that Information Systems (IS) research (and all research) benefits from being strategic 3 at every level, from individual researcher, to research program, to research discipline and beyond. 4 I first argue the merits of a strategy orientation on the Information Systems discipline (the discipline level) and introduce “IS discipline (ISd) strategy” as a new theme of Strategic Information Systems (SIS) research. My focus is more specifically on ISd research strategy. An important mechanism of ISd research strategy is research programs (the program level). There are strong motivations for research to become more programmatic. Programmatic research (defined in Section ‘(E) ISd-Research Strategic Programs’) is necessarily strategic, entailing larger and longer-term investment and risk, and concomitantly, increased oversight and direction. For scope reasons, I do not focus on the potential value from individuals being strategic in their research activity (the individual level), an important topic warranting separate attention. It is hoped the discussion herein will engender a longer-term and more strategic view of IS research activity, perhaps promoting coalitions, engagement and impact.

The viewpoint proceeds as follows. I next present background to the challenges currently faced by disciplines and briefly explore their contemporary strategic context. I then introduce the notion of Information Systems discipline (ISd) research strategy, identifying five valuable levers or strategy mechanisms: A) strategy theory and its intersection with the nature of the discipline; B) strategic governance; C) strategic methods; D) strategic foci; and E) strategic programs. Having argued the value of adopting a strategy lens on ISd-research, in part four I consider possible paper submissions to JSIS and elsewhere that address any of the five ISd research strategy mechanisms, with an emphasis on strategic programs. The viewpoint concludes with discussion on contributions, limitations and future directions.

Like all disciplines, ISd faces many challenges. Changes in the Higher Education sector worldwide “ have meant a growth in the strength and number of forces acting on academic cultures ” ( Becher & Trowler, 2001, p. xiii ). In recent decades, the way in which knowledge is produced has been changing ( Gibbons et al., 1994 ) and these changes are impacting ISd. Gibbons et al. describe two modes of knowledge production: “ By contrast with traditional knowledge, which we will call Mode 1, generated within a disciplinary, primarily cognitive, context, Mode 2 knowledge is created in broader, transdisciplinary social and economic contexts .” (p.2) Manathunga and Brew (2012, p. 45) contrast Mode 1 as “ a situation where knowledge was principally defined within universities by academics within well-defined disciplinary domains ” with Mode 2 in which “ governments intervene in dictating research agendas through, for example, their funding and evaluation mechanisms requiring researchers to focus on short-term clearly defined project outcomes that have economic benefits ”, “ there is critical questioning by an informed public of the practical and ethical implications of particular discoveries and programmes ” [i] , and there are “ new triple helix linkages between universities, the state and industry ”.

In parts of the world, the shift towards Mode 2 knowledge production has been long-standing ( Trowler, 2012 ). Funding agencies such as governments are playing an important role in this shift, using drivers such as performance-based research funding systems (e.g. ERA in Australia and REF in the UK), funding models that encourage researchers to partner with industry and to achieve commercial outcomes (e.g., co-operative research centres and centres of excellence) and that emphasise research aimed at defined regional and national objectives ( Turpin & Garrett-Jones, 2000 ). While this shift has been less pronounced and less orchestrated in the U.S. and places where universities are comparatively more autonomous and less reliant on government funding ( Lepori et al., 2019 ), it is happening, and has the potential to mushroom as the world transitions to a new state post-COVID-19 5 .

The Information Systems discipline has from its inception needed to adapt rapidly to changing technologies and environments. Merali et al. (2012) consider that the discipline’s “ adaptive characteristics” and “the coexistence of stability (and relatively smooth evolution) at the meta-level with diversity and churn at lower levels suggest the kind of ambidexterity” that will allow “the co-existence of both ‘Mode 1’ research emphasising the creation of a rigorous body of knowledge and establishment of identity of the field and its researchers in academia, and ‘Mode 2’ research having a trans-disciplinary character, working across boundaries with heterogeneous stakeholders and real world problems” (p. 131).

Accelerating social and technological change ( Krishnan, 2009 ) and the de-professionalization of academia have also been impacting disciplines. De-professionalization is evidenced by the number of academics in non-tenured positions ( Mazurek, 2012 ) 6 ; by the “ the multiplicity of managerial responsibilities” being added to the workload of academics ( i.e. additional “ responsibility without power”) ( Demailly & de la Broise, 2009 ); and by “ requirements to meet externally imposed performance criteria” and “ demands to demonstrate the relevance of their work in relation to new institutional mission statements ” ( Beck & Young, 2005, p. 184 ). In 2016 with colleagues, I wrote ( Gable et al., 2016, p. 693 ), “ The challenge today is from de-professionalization, a challenge facing all academic disciplines to varying degrees. We sense a growing tension between the disciplines and institutions that seek increased allegiance from individuals in the face of increasingly demanding organizational KPIs and new directions. That strong institutional pull demands that disciplines better communicate their value proposition and reconsider opportunities for reinforcing and strengthening the values, beliefs, and codes that have underpinned IS research. This is a complex, recent, and potent development demanding further research scrutiny .” [ii]

Articles discussing the state of the Information Systems discipline are many and varied and opinions often conflict. One key debate has centered on what forms the core and scope of IS. This debate generated a series of eleven articles published in the Communications of the Association for Information Systems (CAIS) in 2003 (e.g. Alter, 2003 , Myers, 2003 ) and continues today (e.g. Petter et al., 2018 ). Another debate concerns the nature of the IS discipline; this debate is exemplified by the eight articles in CAIS in 2018 that debated whether information systems is a science (e.g. Dennis et al., 2018 , McBride, 2018 ). These are important debates, as the degree of convergence of a discipline can have political implications. “ Convergent communities are favourably placed to advance their collective interests since they know what their collective interests are, and enjoy a clear sense of unity in promoting them ” ( Becher 1989, p.160 ).

The IS discipline too is varied worldwide. From our 2006 multi-country case study of the state of the IS discipline in Pacific-Asia ( Gable, 2007 ) we observed many differences; for example, there were stark differences in levels of engagement with practice across countries surveyed. That study's theoretical framework ( Ridley, 2006 ) was partly guided by Whitley’s Theory of Scientific Change (1984a) . Scientific fields are seen as “ reputational systems of work organization and control ” ( Whitley, 1984b, p.776 ) and Whitley proposes that there is an inverse relationship between the impact of local contingencies and a discipline’s degree of professionalism and maturity. With reference to Taiwan and Singapore I wrote “ These two cases alone – where local contingencies have much influence on IS in universities, yet where IS in the universities is strong and of high status - suggest a need to revisit the theory, and cast doubt on the theoretical proposition that a mature discipline should be uniform internationally, and relatively uninfluenced by local contingencies ” ( Gable, 2007, p. 17 ).

Many disciplines have questioned whether they will continue existing, for example Sociology ( McLaughlin, 2005 ), Accounting ( Fogarty and Markarian, 2007 ), and Strategic Management ( Jarzabkowski and Whittington, 2008 ). Less apocalyptic prognosticators have over the years suggested various ways of responding and strengthening their discipline (e.g. Keith, 2000 , Kitchin and Sidaway, 2006 , Somero, 2000 , van Gigch, 1989 ). IS researchers have made several recommendations. Thatcher et al. (2018, p. 191) propose three: “ (1) adopt an entrepreneurial model of scholarship, (2) engage with practice, and (3) double down on the intertwining of the social context and IT” . Hirschheim and Klein (2012, p. 193) suggest there is a need for “ continuous effort to define and redefine IS to reflect the evolving boundaries of the field ”. Other prominent researchers have suggested there is value in re-examining current methods and understandings, for example Gregor (2018, p. 114) suggests “ there should be ongoing questioning of our epistemological foundations” . Nunamaker et al. (2017, p. 335) believe that how we conduct research can make a difference and that “ IS researchers can produce higher-impact contributions by developing long-term research programs around major real-world issues, as opposed to ad hoc projects addressing a small piece of a large problem ” [iii] . Perhaps the challenges disciplines have been facing will pale in comparison to new challenges that emerge post-COVID-19, or perhaps COVID-19 will in the main, exacerbate existing forces. 7

In summary, ISd is amidst major change due to accelerating social and technological change, de-professionalization, the inexorable shift towards Mode 2 knowledge production, and COVID-19. A variety of responses has been proposed, all of which imply value from a longer-term strategic orientation and closer proximity to practice.

Information Systems Discipline (ISd) Research Strategy

Through an archival analysis of 316 Journal of Strategic Information Systems (JSIS) research papers, from the journal’s inception through to the end 2009 ( Gable, 2010 ), I discerned a high-level three category classification of Strategic IS (SIS) research: (i) IS for strategic decision making, (ii) Strategic use of IS, and (iii) Strategies for IS issues. As implied in the preceding section, disciplines are facing challenges and discipline-level strategizing is warranted. Herein I propose a fourth category of SIS research; namely, (iv) IS Discipline Strategy. Fig. 1 depicts the relationship between these four nodes or research themes and SIS (wherein SIS is represented as one of several top-level domains of IS research). It is notable that the primary referent or focal phenomenon in (i) and (ii) is the “information system”. In (iii), the primary referent is “IS management” or the “IS function” (whether a formal or informal function; whether central or diffuse). With the addition of (iv) the fourth theme of SIS, I introduce a further primary referent, this time the “IS discipline” (ISd). Of course ISd, like other entities, may also benefit from IS for strategic decision making, strategic use of IS (e.g. the Association for Information Systems (AIS) web presence) and strategies for IS issues (e.g. information management of the AIS eLibrary), thus research in the original three categories may have direct or analogous relevance for ISd as well.

A Strategic Information Systems (SIS) Research Taxonomy (adapted from Gable, 2010 ).

While proactive IS discipline strategizing [iv] may initially seem insular or self-serving and perhaps counter to the general conception of academe as open, collegial and cooperative, I nonetheless believe that many disciplines as traditionally constituted are under some threat and there is value in being proactive rather than passive in responding. All disciplines will benefit from pertinent reflection and positioning (many envisaged findings regarding ISd would have direct, parallel relevance and value in other disciplines).

It is important to note that representing ISd Strategy in Fig. 1 as a fourth theme exaggerates its pertinence in SIS research. This amplification of prominence serves the purposes of this article, the main of which is to promote attention to strategy in IS research. Many alternative classifications of SIS research are possible, and while the suggested four categories of SIS research are not entirely mutually exclusive, nor strictly at the same level of abstraction, they are useful (perhaps a taxonomy rather than a classification).

With reference to Fig. 1 , it is useful to attempt a single overarching research question that captures much of the research represented by each node of such a hierarchy; questions at higher levels being inherently broad, becoming more specific at lower levels (each node can be expanded into a set of underpinning sub-nodes and research questions; such a detailed research agenda was outside scope). The question being asked at the new fourth SIS node is “What is the ISd Vision and how should ISd strategize?” (Recognising that the vision today will likely be much different from 10 or even five years ago). Referring back to the original three categories (themes in Fig. 1 ) identified in ( Gable, 2010 ), in retrospect I suggest the following questions: (i) IS for Strategic Decision Making – How can IS support strategic decision making? (ii) Strategic Use of IS - How can IS be used strategically? (iii) Strategies for IS Issues - What strategies support the IS management/function? (While it is difficult to divine a sufficiently broad yet adequately focused question at the highest SIS node, I suggest “How can IS be strategic? (where IS = Information Systems, IS function, IS discipline).

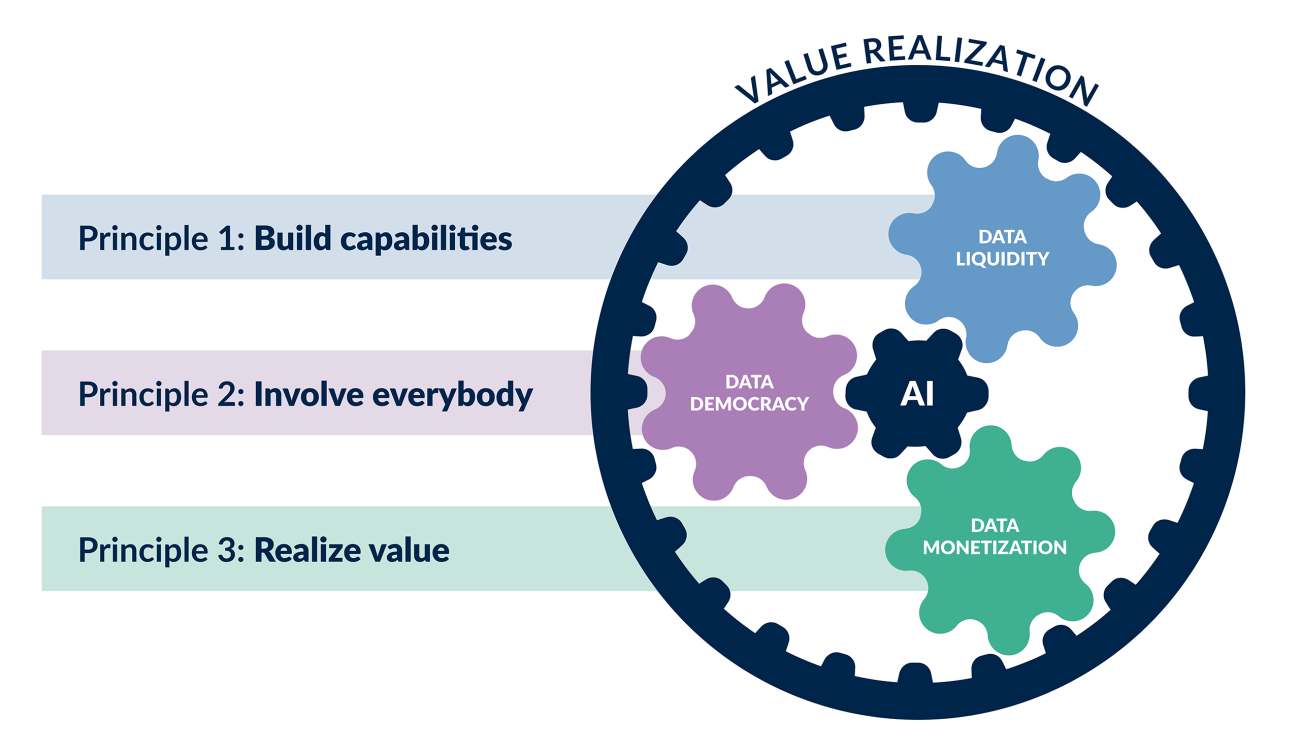

While much of the discussion herein has relevance to ISd broadly, the focus of this article is on ISd-Research strategy, which is differentiated in Fig. 2 as a sub-theme of ISd strategy (other possible sub-themes might be, for example, Teaching & Learning and Professional Service – in Australia many universities evaluate academic performance in these three areas). Following I argue the relevance of five mechanisms of ISd-Research Strategy: (A) ISd-Research Strategy Theory, (B) ISd-Research Strategic Governance, (C) ISd-Research Strategic Methods, (D) ISd-Research Strategic Foci, and (E) ISd-Research Strategic Programs. The dictionary definition of mechanism serves our purposes here; “ An Instrument or process, physical or mental, by which something is done or comes into being ” ( The Free Dictionary by Farlex ). A definition more specific to this article might be “a means of being strategic”. Thus, ISd research is strategically facilitated through these mechanisms. The five mechanisms in Fig. 2 can usefully be considered as pertaining to ISd-Research Strategy practices: (A) how we define ourselves (as a discipline), (B) how we govern (as a discipline), (C) what we do (as a discipline), (D) how we do it (as a discipline), and (E) how we organise (as a discipline). I next discuss each of these five mechanisms (A) through (E) in turn, thereby also further explicating Fig. 2 .

Information Systems Discipline (ISd) Research Strategy: a Research Taxonomy.

(A) ISd-Research Strategy Theory

There is merit in exploring relevant research strategy theory for ISd. The IS discipline can influence perceptions, conceptions and directions of IS research through theorising IS research strategy. While parallels may exist between disciplines and other entities that have been the focus of past strategy research (e.g., commercial enterprises), disciplines, and ISd more specifically, have distinctions of strategic consequence. There is thus value in critically revisiting extant strategy theory with a view to its relevance in this context. 8

In a seminal work on strategy, Mintzberg (1987) presented and discussed several interrelated definitions of strategy: a plan (a consciously intended course of action), a pattern (consistency in behaviour, whether or not intended), a position (locating the organization in the environment), and a perspective (individuals linked by common thinking and behaviour). Mintzberg particularly emphasised the significance of collective perception and action in any strategy, stating “ strategy is not just a notion of how to deal with an enemy or a set of competitors or a market … It also draws us into some of the most fundamental issues about organizations as instruments for collective perception and action ”. Thus, the process of ISd-research strategizing offers value irrespective of the outputs.

The literature on strategy as practice might also aid our understanding. Peppard et al. (2014, p.1) suggest “ In addressing strategy as practice, the focus of research is on strategy praxis, strategy practitioners and strategy practices […] – the work, workers and tools of strategy in other words .” Strategy as practice takes the view that “ we must focus on the actual practices that constitute strategy and strategizing while at the same time reflecting on our own positions, perspectives and practices as researchers ” ( Golsorkhi et al., 2010, p. 2 ). How does the discipline strategize both consciously and unconsciously (e.g. by our patterns of behaviour)? In essence, the five mechanisms of ISd-Research strategy in Fig. 2 represent research practices of the ISd.

The strategy as action approach has been discussed in relation to research on information systems strategy (e.g. Whittington, 2014 ) but has yet to be applied to ISd-research strategy. A novel paper that broaches ISd-research strategy theory is by Merali et al. (2012) which conceptualises the IS research domain as a complex adaptive system. The authors suggest that the field of IS research is relatively diversified and dynamic, with new topics rapidly emerging, thus the landscape of IS research is constantly changing with scholars frequently shifting attention to investigate new IS and IS phenomena. They ultimately argue that the IS domain has sufficient adaptive capacity to evolve in the emerging competitive landscape, responding to the turbulence, uncertainty and dynamism of IS research (a complex adaptive system).

Banville and Landry (1989) had an alternative view of IS research. They characterised MIS [v] as a fragmented adhocracy (which suggested a lack of strategic direction). A few years later, Hirschheim and Klein lamented “ That our current status remains a ‘fragmented adhocracy’ suggests the field may indeed be in crisis or headed for a crisis ” stating that the disconnects within the IS research community arise “ from the lack of communication among the numerous research sub-communities ” (p.254). Hirscheim and Klein recommended addressing the communication deficit through the development of a body of knowledge in information systems. Taylor et al. (2010) were more optimistic: they believed they demonstrated that “ over the 20-year period from 1986 to 2005, the discipline has shifted from fragmented adhocracy to a polycentric state, which is particularly appropriate to an applied discipline such as IS that must address the dual demands of focus and diversity in a rapidly changing technological context ” (p. 647). These dual demands have also been recognised by other IS scholars. For example, Tarafdar and Davison (2018, p. 543) envision IS as “ a flexibly stable discipline that has both (1) a consolidated deep structure (through the Single and Home Disciplinary contributions); and (2) a periphery of flux (through the Cross Disciplinary and Interdisciplinary contributions )”.

What other theory might be relevant to ISd research strategy? In light of the Hirschheim and Klein (2003) call for the development of a body of knowledge in information systems, an example might be analogizing “research knowledge assets” with knowledge assets broadly, and drawing on knowledge management theory. James (2005) usefully bridges knowledge management and strategic management in ways that lend readily to the notion of research knowledge assets. He found that “ existing knowledge assets form the basis of strategies” (p.165). Theories and strategies from other analogous spheres could be adapted and applied to IS research practice. An example might be analogizing research practices with consulting practices and borrowing from Maister (1993) to develop what I call a Research Practices Lifecycle View, which I elaborate further in later discussion on “ISd-Research Strategic Programs”.

(B) ISd-Research Strategic Governance

For our purposes, strategic governance mechanisms are simply defined as mechanisms of alignment of research practice with ISd-Research Strategy . The IS discipline has ability to influence research strategy through introducing and adjusting various governance levers [vi] . High-level examples in Fig. 2 include the Association for Information Systems ( https://aisnet.org ), doctoral consortia, and conferences. The AIS is a primary ISd-Research Strategic Governance Mechanism for many. Reverse-engineering the AIS website would yield, for example, the AIS Faculty Directory (valuable in expanding and tracking membership), the eLibrary (establishing what is in, and what is not), AISWorld Listserv (communicating core ideas), Awards & Recognitions (signalling what is valued), AIS journal viewpoints and review/fit policy e.g. JAIS/CAIS, and so on [vii] . At a more local level, using Australia as an example (being Australian, I use several Australian examples), strategic governance mechanisms include: the AAIS (the Australasian regional branch of the AIS), Australasian Conference on Information Systems (ACIS), Australian Council of Professors and Heads of Information Systems (ACPHIS), IS Heads of Discipline listserve (ISHoDs) and various initiatives of AAIS and ACPHIS. Example initiatives of AAIS and ACPHIS include their lobbying for IS representation on Australian Research Council (ARC) panels, their Journal and Conference rankings [viii] and awards (e.g. ACPHIS Best Australian IS PhD Medal), and representation in the Australian Computer Society, etc.

“Research on strategy broadly suggests that professional organizations use signalling mechanisms such as awards to direct attention to high-level priorities” ( Ghobadi & Robey, 2017, p. 360 ). Best publication awards signal the core values and priorities of the field. 9 The characteristics of papers/theses that receive awards form patterns that influence what is researched and how [ix] . For example, Ghobadi and Robey found that “ most of the award winning IS articles rate high on theory building” and suggested that this is to position IS as a “ distinct discipline” rather than one that mostly borrows theory . The discipline needs to be aware of the patterns of research that awards are solidifying and take note of evolving trends that may necessitate the development of newer more advantageous patterns [x] . Strategic action in this regard is important “ to support the continuous development of the field ” ( Ghobadi and Robey, 2017 ).

As a further example, my co-authors and I ( Gable et al., 2016 ) explored the strategic importance of doctoral consortia as an ISd-Research strategic governance mechanism. We differentiated four levels of consortia: (i) International (ICIS), (ii) Regional (e.g. PACIS), (iii) National (e.g. ACIS) and (iv) Local (e.g. the School of Information Systems Doctoral Consortium at Queensland University of Technology) and considered their relative roles and influence. We argue that “ Consortia are strategic: a centrally important mechanism for sustainment, rejuvenation and defence of the discipline” (p. 691) . Closing the article, we further wrote “ we return to the advent of the 1st ICIS Doctoral Consortium in 1980, seen against a background at that time of questioning the status of Information Systems as a legitimate academic discipline. In some sense, the adversary then was other disciplines, and their perceived higher standards of professionalism. Today there is a different adversary, and again we see the Consortium as a possible vehicle of discipline reinforcement.”

Thus, the strategic influence of existing and potential governance mechanisms is readily apparent. That said, more transformational governance is possible ( Rosemann, 2017 ).

(C) ISd-Research Strategic Methods

The IS discipline has the ability to influence the kinds of questions being asked and research being pursued through the development, promotion and endorsement of contemporary research methods. Grover and Lyytinen (2015) argue the need to “ critically examine and debate the negative impacts of the field's dominant epistemic scripts and relax them by permitting IS scholarship that more fluidly accommodates alternative forms of knowledge production .” Given the IS research phenomenon of interest (the nexus of people and technology) and our proximity to rapidly changing technology, and the dynamism and generativity of these developments, we need as a discipline to explore new and improved ways of researching ( Rai, 2018 ). Moreover, though the outputs and outcomes of strategic methods may offer potential for research broadly, they offer particular advantage to the IS discipline. This is one of several places in the viewpoint where I advocate that ISd “practice what it preaches” by deploying within ISd, research methods developed by ISd, 10 the implicit question being “What new research methods does ISd require in order to remain relevant?” Put differently, the question might be, “What new research methods would be to the advantage of ISd research?”

As an example Galliers (2011, p. 300) suggests that, what previously might have been considered opposing research traditions, “ might unite to provide a more holistic, and ultimately more edifying, research agenda: one that is inclusive of various research approaches, and thereby better able to provide fresh, and more plausible insights into the complex phenomena we study ”. Tarafdar and Davison (2018) warn of the risk of asking narrow research questions in an attempt to reduce their complexity. They observe a “ lack of multiple IS subdisciplines in a single paper [suggesting] that IS phenomena are perhaps not being investigated in their full richness and complexity, reinforcing the concern about narrowly conceptualized research questions” (p.539). More nuanced, creative and relevant questions may demand new methods.

IS is particularly well placed to progress new and strategic research methods by leveraging what we already know, have and do [xi] . I first argue there is merit in exploring the potential from employing various IS representation techniques in the redescription (or reverse engineering) of existing research methods (e.g. Zhang and Gable, 2017 , Leist and Rosemann, 2011 ). In addition to facilitating improved understanding and combining of well-trod methods, such “redescribing the old” is expected to better-inform design of new research methods, particularly those needed by IS given the dynamism of our focal research phenomena. I further subscribe to the views of March and Smith, 1995 , Venable and Baskerville, 2012 who advocate the merits of a design science research (DSR) approach to the design of new research methods: research methods here conceived as designed artifacts, and DSR originating out of IS. Thus, we see that IS is both well placed to contribute to the design of improved and new research methods and to benefit as a discipline from the adoption of such improved and new methods. 11

ISd has not been idle with innovating new methods, in example the extensive methodological thought around Design Science Research (e.g. Vaishnavi et al., 2019 ). As further example, with net-nography (an online research method originating from ethnography employed to study social interaction in digital communication), we observe a phenomenon through the very technologies that we study (thanks to a panellist here). Grover et al. (2020) discuss the dramatic shift occurring to big data research (stating 16% of papers in top IS outlets employed this approach in 2018). They offer several conjectures that suggest possible unanticipated consequences of these approaches: the implication being these approaches have not been researched adequately. Thus, while I do not advocate epistemological anarchy ( Treiblmaier et al., 2018 ), I believe much more is possible. Furthermore, the focus of the information systems discipline on new phenomena, in combination with our position straddling the sciences of the real and artificial, arguably places us in a position of strategic advantage with regard to epistemology. Put simply, if we investigate new phenomena first, then we are well placed for providing leadership in how to investigate it.

(D) ISd-Research Strategic Foci

I here suggest that an important mechanism of ISd-Research Strategy is “ISd-Research Strategic Foci”, the overarching question being “What new research foci are strategic for ISd?” The IS discipline has ability to influence the direction of research in IS through identifying, recognising and promoting promising research foci.

It is apparent that the notions of ISd-Research Strategy and ISd-Research Strategic Foci imply centrally coordinated strategizing and decision-making. While this does occur, I think increasingly (e.g. by AIS in relation to the international discipline; by ACPHIS in relation to the Australian IS discipline; by universities, faculties and schools in relation to the local IS presence), it is acknowledged that historically, developments have been more distributed and organic. Thanks to a panellist who suggested “ The history of the discipline suggests that the strategic foci (at a disciplinary level) are plastic, emergent, and to a considerable extent, responsive to changes in technology and its role and uses. Studies examining the “core of the discipline” have frequently been bottom up” and have identified changes over time. Arguably, this has affected the ability of IS researchers at various levels to articulate the strategic foci of their work and how it aligns with broader institutional or national research strategy .” Such developments have been driven by individual preferences, capabilities, efforts and circumstances, and only indirectly shaped by various governance mechanisms (e.g. doctoral consortia and conference panels, editor and reviewer feedback and other institutional and discipline-cultural influences).

Though the shift to performance-based funding systems which emphasise impact and economic benefits is anticipated to amplify efforts to centrally coordinate research activity (e.g. in Programs – to be discussed), individual-driven and small-team research within broad areas of promise is expected to continue forming the core of the research ecosystem. Such broad areas of promise, or foci, may evolve organically, inductively, from the bottom-up. Blue-sky research is acknowledged to form “ a vital part of scientific discovery ” ( Linden, 2008, p. 10 ). Alternatively, such foci might be promoted top-down, by the AIS or other authorities (international, regional or local) - promoted, but not coordinated. Many recognise that such highly distributed inductively selected research activity is foundational to science. Wu et al. (2019) analysed 65 million papers, patents and software products, spanning 1954–2014, concluding that smaller teams have tended to disrupt science and technology with new ideas and opportunities, ultimately concluding, “ both small and large teams are essential to a flourishing ecology of science and technology ”.

While, I believe that in IS individual-driven and small-team research in IS has predominated and should continue to be strongly encouraged and supported, I later argue that to achieve a flourishing ecology, we also need to promote larger, more programmatic research initiatives [xii, xiii] . I recognise that a dichotomy of small and large initiatives is coarse and accept there is value in considering more of a continuum. As suggested by one senior scholar, “ sometimes people proactively/serendipitously reach out, pool resources if working on the same topic and cumulatively build the research projects. This can be an organic and agile way of doing things rather than the traditional funding way. A combination of programmatic and individual if you will – perhaps a ‘third’ way that could capture the best of both worlds? ”

A journal too can be strategic (in fact all are at some level) and a vehicle for promoting strategic foci, and JSIS is a prime example. In the first issue of JSIS Bob Galliers reported “ In business schools around the world it is often the case that IT, IT strategy and information management are considered at best as optional topics unworthy of being included in the core programme” and “ discussion of information and IT issues is not integrated into other business topics ” ( Galliers, 1991, p. 3 ). Galliers' championing of JSIS in the late 1980s was a strategic move to address this concern and to claim related research for the IS discipline, by promoting an outlet with this focus.

In closing this section, I argue there is value in promoting strategic research foci [xiv] , as distinct from strategic research programs (to be discussed). I believe there is merit in promoting, for example, Digital Innovation as a research focus of individual researchers and small teams (important research questions demanding attention being a key motivation for a focus), while possibly in parallel orchestrating larger more programmatic oversight (e.g. a Digital Innovation research program). Further, not all research foci lend themselves to a programmatic approach or warrant the size of a program.

(E) ISd-Research Strategic Programs

I suggest that an important mechanism of ISd-Research Strategy is strategic ISd Research Programs, or “ISd-Research Strategic Programs”, the overarching question being “What research programs are strategic for ISd?” [xv, xvi] . As mentioned above, differentiating strategic programs from strategic foci highlights the possibly more proactive role of the AIS or other coalitions within the IS discipline in strategically coordinating targeted research. For my purposes herein, research programs are simply “organisations for conducting programmatic research.” I intentionally define programs broadly and loosely to encompass both less, and more formal organisations or orchestrations of research.

The notion of programmatic research is not well established. In Communication, Benoit and Holbert (2008, p. 615) suggest programmatic research “ systematically investigates an aspect of communication with a series of related studies conducted across contexts or with multiple methods .” In Education, Berninger (2009, p. 69) suggests “ Programmatic research is designed to answer questions systematically, with the results of one study informing the research questions and design of the next study in a line of research that seeks comprehensive understanding of a phenomenon .” In Management Information Systems, Martin (1995, p. 28) defines programmatic research as “ a structured plan for conducting studies systematically across the entire span of a chosen field of enquiry .” While all of these definitions overlap and complement, none explicitly addresses the extension of research strategy through to implementation in practice, with feedback, a notion we endorse and depict in Fig. 3 .

Relevance Realisation Lifecycle Model [adapted from Moeini et al, 2019 ].

For the purposes of this paper I define programmatic research as the systematic and holistic investigation of strategically significant phenomenon through multiple coordinated and interrelated projects by a team of researchers, with the joint aims of knowledge contribution and positive impact on the world. An assumption is that programmatic research is in accord with strategy; there can never be reason to initiate research on the scale of a program that is not in accord with strategy. And though a basic-research program is conceivable, herein there is the assumed joint intention of positive impact as well as knowledge contribution. The program itself may extend to impact and outcomes or it may be extensible to impact, and what is meant by holistic must be locally defined. 12

Programmatic research demands closer interaction and cooperation amongst the program members. They rely more closely on each other’s ideas and outputs, the related ownership of which is more complex and nuanced. A program’s scale facilitates specialisation of function, which introduces complexity around the allocation of roles and rewards. The relative longevity of programs suggests the possible need to conceive of intermediate outputs and outcomes of value to the program, where the value to individuals isn’t clear and needs to be managed or orchestrated. Terms often used to differentiate programs (from projects) are larger, longer, more complex, less well defined, with more stakeholders, evolutionary, holding a systems view, exhibiting a plurality of goals, and being more strategic. More specific to research, other terms include multidisciplinary, trans -disciplinary, lifecycle-wide, and multi-paradigmatic (of course these terms do not pertain strictly to either projects or programs).

The Project Management Institute (2008, p. 9) defines a program as “ a group of related projects managed in a coordinated way to obtain benefits and control not available from managing them individually. Programs may include elements of related work outside the scope of the discrete projects in the program. A project may or may not be part of a program but a program will always have projects. ” Thus, there may be outputs/outcomes that pertain to the program but not directly to any of its component projects. This has profound implications for the planning, identification and recognition of value that derives from the research program. Clarke and Davison (2020) argue that what they call “multi-perspective research”, while feasible within individual research projects, may be more readily achieved through research programmes.

A conceptual framework I've found valuable for interrelating and accommodating diversity in programmatic research is what I refer to as a “research practices lifecycle view”. I analogize research practices with consulting practices and borrow from Maister (1993) who differentiates three types of consulting practices: the “big brains” practice which employs considerable raw brain power to solve frontier (unique, bleeding edge, new) problems; the “grey hair” practice which has prior experience of similar situations; and procedural practices which use developed procedures and systems to handle specific problems efficiently. Choo (1995) describes these as background knowledge framework, practical know-how and rule-based procedures. I loosely refer to analogous research practices as Expertise, Experience and Efficiency respectively, and suggest that these are not discrete, but rather positions on a continuum; and that practices tend to start from strong emphasis on Expertise (e.g. novel, basic research), and with the passage of time and through experience gained, move along the continuum towards Efficiency (e.g. incremental replication studies) and relatively more applied research. In a large research group, or through collaboration, such practices can co-exist and complement, with more basic research findings generating more applied, possibly practice-based testing and extension studies (perhaps extending to commercialisation). Each practice area benefits from quite different capabilities and team member motivations, thus accommodating diversity. The Research Practices Lifecycle View framework further demonstrates the value to be gained from a broader and longer-term view of research; it represents a higher level of abstraction in research design/strategy, that spans and interrelates multiple, otherwise disjoint zero-base initiatives.

Ultimately, I chose to amplify the value of programs as distinct strategic mechanisms. Such mechanisms may be higher-order and formal, for example, the AIS Bright ICT Initiative ( Lee, 2015 , Lee et al., 2018 , Lee et al., 2020 ); a key project of this initiative aimed to develop the framework for “ a new and safer Internet platform ” ( Lee, 2015, p. iii ). Programs can vary in size, scope and formality, from substantial and long-lived programs such as AVATAR (Automated Virtual Agent for Truth Assessments in Real-Time), an almost 20 year partnership of eight universities led by the University of Arizona in conjunction with more than ten Government departments ( Nunamaker et al., 2017 ), to more local research concentrations (e.g. the continuing trend in Australia towards concentrating people and resources locally – e.g. within a “Centre” – in areas of perceived strength, promise and advantage 13 ). Though I imply herein that such programs are at this stage often more implicit than explicit (and vary internationally in terms of their prevalence), it is felt that all such forms can be usefully considered under the umbrella of research programs [xvii] .

ISd-Research Strategy Publications

This viewpoint set out with two main aims: (i) to argue the importance of a strategic research orientation for the Information Systems Discipline (discipline level); and (ii) to facilitate such a strategic orientation by trumpeting the value of related research and promoting its publication. Having in Section ‘Information Systems Discipline (ISd) Research Strategy’ above addressed (i), in this section I further address (ii) aiming to partially clear-the-way 14 for manuscript submissions to JSIS and elsewhere, in attention to any node of the ISd-Research Strategy branch in Fig. 2 , but with particular emphasis on research programs (program level).

Thus, a key aim of this viewpoint is to facilitate manuscript submissions that align with any of the five mechanisms in Fig. 2 ; namely, ISd-Research Strategy … (A) theory, (B) governance, (C) methods, (D) foci, and (E) programs. Papers on (A) theory and (B) governance, though important, are anticipated to be rare, with papers on (C) strategic methods again anticipated to be occasional only. Papers arguing for a new strategic research focus (D) would entail a general call for the IS discipline to pursue research in relation to some new or emerging phenomenon of perceived consequence. The expectations of such papers and the standards for acceptance will be demanding. Such papers will tend to encompass a comprehensive review of the pertinent literature (akin to a review or curation), but rather than emphasising theory development, will include greater detail on the research agenda into the future; they should amplify discussion of potential impact and how the focus is strategic for IS [xviii] (in many ways this current paper is such an article, without the rigorous attention to the literature). Thus far in this section, having very briefly accounted for (A) through (D) of Fig. 2 , I now turn my more detailed attention to (E) Programs.

Papers arguing for a new strategic program would detail either a proposed or an in-progress program of research, evidencing to the extent possible the value of and potential from a programmatic approach. There would be strong emphasis on potential future research, as well as on how the proposed future research is strategic for the IS discipline. Note that articles explicating research Programs, much like foci articles, will often (not always) build on an established track record of work across and beyond the discipline, and perhaps parallel or subsume a curation (e.g. https://misq.org/research-curations/ ) or major structured literature review (e.g. see Rivard 2014 ), while bringing a more strategic lens to the analysis and interpretation, and having greater emphasis on strategic prescription. It is useful to differentiate explicitly the design of these larger programmatic initiatives as “research strategy” as compared to “research design” at a more individual project level. Employing this language, I consider the Tarafdar et al. (2018) suggestion for more longitudinal studies [xix] , to be a research strategy, more at the collective program level.

I am not so naïve as to assume I can here offer comprehensive guidance on what to attend to in the design and reporting of research programs [xx] . Rather I constrain my focus to engendering and promulgating the relevance of such research (here I largely equate relevance with impact which I more specifically define in the next section – ( Davison and Bjørn-Andersen, 2019 ) refer to 'societal impact'), for which purpose I draw on Moeini et al. (2019) . Their work suggests several valuable mechanisms of programmatic research including: (i) the value from adopting a multilevel view in research design (I herein usefully employ this view by differentiating between the individual/project level, the program level, and the discipline level), and (ii) the value of a longer, multi-phase view of research design from knowledge-potential-generation through to realised-impact (a more programmatic view). Though their focus is constrained to relevance, which is not the sole intent of programmatic research, the relevance intent demands a consequential and valuable longer-term, more strategic and holistic view [xxi, xxii] .

A Relevance-Centric Approach to Programmatic Research

Fig. 3 depicts the four phases of research relevance realisation differentiated by Moeini et al. (2019) (Potential > Perceived > Used > Realised). Key variations herein to that work are (i) the alternative conception of their four “dimensions” of relevance potential as “stages” of relevance-potential generation, 15 and (ii) the combining of those stages with their phases of relevance realisation in a process view including feedback loops. I believe this lifecycle view represents a more readily actionable and systematic approach to designing relevance into a larger, more strategic research program. Moreover, though the stages of relevance-Potential generation in Fig. 3 (the left-hand side) tend to be associated with research, and the latter three phases of relevance realisation (the right-hand side … Perceived, Used, Realised) tend to be associated with practice, the stages and phases can be tightly intertwined. For example, in action research or action design science research, or through other larger, longer-term more programmatic research that extends to the later phases of relevance realisation, there can be useful iteration back to earlier phases, thus the feedback loops.

My use of the term “impact” throughout this viewpoint has a different connotation from many. I am not referring to impact-factors and citations, but rather I am concerned with influence on practice and policy (societal value). However, unlike many definitions of “impact on practice and policy”, I am not solely focused on the impact of research outside of academia, as some impact frameworks are (e.g. https://re.ukri.org/research/ref-impact/ ); I also value research that impacts the practice of research. I note that the Strategic Methods node C in Fig. 2 is all about research that impacts research practice.

To more clearly position and bound their study, Moeini et al. (2019) (i) differentiate their focus on “potential practical relevance” from other conceptions of relevance, (ii) differentiate dimensions of relevance, (iii) differentiate stakeholders of relevance, and (iv) differentiate levels of analysis of relevance. These distinctions all have value in clarifying discussion on research relevance, each addressing a different question - What type (phase) of relevance realisation? Which dimension (or stage)? For whom (what goal)? And, at what level (e.g. individual project, Program, research area)? I now turn briefly to (iv) differentiating the levels of analysis of relevance.

As stated at the outset, it is my view there is value in a strategic orientation on research at every level, from individual to program to discipline and beyond. Such a multilevel view of research also recognises that the value from research can be at different levels: individual project, program, domain/field (research area); or emergent. As Moeini et al. indicate, “ while each individual article does not necessarily need to have a high potential for practical relevance … a research area needs to provide a degree of potential practical relevance”. 16 The value of some research may be more local e.g. relevant to the program but not to practice broadly. If such an intermediate output is intended, then perhaps there is a greater need to explicitly position the pertinent sub-study within the larger program. To the extent that individuals have some sense of how their individual projects are part of a larger, multilevel undertaking, they will be better placed to understand and explain the merits of their work to peers, research groups, examiners, reviewers, editors, funding bodies and so on. I believe this multilevel view of research strategy worthy of further attention.

In summary, in this section I advocate for more relevant IS research; an underutilized strategic option. I strongly endorse focusing a relevance-lens on programmatic research, my discussion further amplifying the value of the Moeini et al. (2019) phases of relevance-realisation. I believe such a lens, and approach ( Fig. 3 ) is valuable in the design and reporting of research programs. I encourage researchers to consider this view in crafting future-oriented research programs strategic for the Information Systems Discipline.

Rigour in programmatic research strategy

In the preceding section, I suggested the beginnings of a relevance-centric approach to programmatic research strategy and reporting, my aim being to partially clear-the-way for larger, more relevant, impactful and strategic research and publications. I am not alone in calling for such work. Yet the elephant-in-the-room whenever such calls are made is the unbending expectation of rigour ( i.e. the appropriate and adequate application of methods).

With regards rigour, I differentiate three possible units of analysis: the project, the program (design and execution), and reporting on the program (description and evaluation). My emphasis in this section is on rigour of reporting. I earlier differentiated projects and programs, suggesting that research project design/execution rigour has received much valuable attention, and that further such attention can be strategic for the discipline (and thus would align with node C in Fig. 2 ). In the preceding section I cautiously offered sample guidance on a relevance-centric approach to research program design (or strategy), acknowledging that research programs are large, complex and highly varied.

The question thus becomes how does one rigorously report on, or describe, and perhaps evaluate, a research program? [xxiii] Pawson (2013) recommends that such description and evaluation should be motivated by rigorous attention to the existing knowledge base and possibly by the development of a conceptual framework or platform. This part of a proposed program report, would parallel in many ways a review article, some such articles going further than others, to advocate for a research agenda. 17 To the extent that such a research agenda is new, such a review article comes very close to a research foci article, as described earlier (mechanism D in Fig. 2 ); such a research foci article promoting widespread, organic, individual projects that attend to argued areas of research need and value that are strategic for the discipline. A paper reporting on a program however, must go further, to address the coalition of resources and stakeholders, the range of constituent projects and their logic (the program “meta-logic”), and the strategic value and importance of the coalition for all stakeholders (the coalition, the discipline, the world). Moreover, while individual projects should, to the extent possible in their design and reporting, attend to outcomes, the opportunity to elaborate such potential is greater and thus essential with research program reports.

Given that Research Programs tend to be large, complex and unique, any guidance here on their description, can be high-level and exemplary only. It is possible that a design science research approach may be appropriate (e.g. treating the Program as a designed artefact), or Action Design Research or Action Research 18 (e.g. evaluating Program implementation with theoretical implications). Perhaps appropriate too are evaluation research approaches, which are varied and employed widely in the evaluation of both practice- and research-based programs. While the term “Evaluation Research” implies ex post evaluation, which is perhaps characteristic of much if not most such work, anticipation of such evaluation can usefully inform ex ante program strategy and description.

In closing this section, I acknowledge merit in documenting programs at various stages, with some provisos. While I appreciate the value of documenting each stage of a program of research (proposed, in-progress, and completed) including its planning, implementation and operation, and with attention being given to predicted, intermediate or final outputs and outcomes, I anticipate that being compelling in such writing will be easier where a program has at least commenced and there is some empirical evidence of its progress. Where the program is planned, but yet to commence, its publication might be considered a form of research-in-progress. Where the program is in progress or completed, some form of program evaluation may be appropriate.

This viewpoint argues the merit of focusing a strategy lens on the Information Systems Discipline. I introduced IS Discipline (ISd) strategy as a new theme of Strategic IS (SIS) research, subsequently focusing more specifically on ISd research strategy. I have advocated the value of a strategic orientation at every level, from individual, to Program, to Discipline and beyond. Research programs in particular, can be a valuable mechanism of research strategy. Though I acknowledge variation across regions and countries (and no doubt within countries), there are strong motivations for research to become more programmatic. Programmatic research is necessarily strategic, entailing larger and longer-term investment and risk, and concomitantly, increased oversight and direction.

Careful consideration was given to the fit of this Viewpoint with JSIS. Details of that thinking are included as Appendix A (I encourage all authors of submissions to JSIS to undergo similar reflection). Ultimately though, all rationales are peripheral to the central aim of the article, which is the amplification of strategic thinking in IS research – the further leveraging of an orientation natural to the JSIS community, with emphasis on research programs as a main strategic lever, and further considering how JSIS can be instrumental in this aim.

This article is a response to the ongoing call for increased attention to relevance and impact in research (e.g., Rai, 2017a , Tarafdar et al., 2018 ). Moeini et al. (2019, p. 210) include a table of suggested “ opportunities for improving potential practical relevance” , with recommendations for authors, reviewers and journals. Table 1 lists the six recommendations that apply to journals [xxiv] . The promotion herein of research pertaining to any of the mechanisms of ISd-Research Strategy in Fig. 2 , and of programmatic research broadly, addresses much in Table 1 , perhaps with some emphasis on opportunities (1)–(4) in that table. One Senior Editor of JSIS has been explicitly advocating for (5), more linked publications. More engagement on social media (6) has admittedly only just appeared on our radar. I am with this viewpoint attuning JSIS editors, reviewers and Board members to all of these priorities.

Suggestions to Journals for Improving Potential Relevance (based on Moeini et al., 2019, p. 210 ) [xxvi, xxvii] .

In some sense this viewpoint is also a response to the Tarafdar and Davison (2018, p. 537) call for increased intra- and inter-disciplinary research in IS and to the Galliers (2003) call for trans-disciplinary/inter-disciplinary research. 19 Tarafdar and Davison suggest, amongst other things, that IS journal editors “ consider editorial policies such as sections especially devoted to the interdisciplinary contributions .” That recommendation overlaps several of the six suggestions in Table 1 [xxv] .

Tarafdar et al. (2018) , rather than focusing on kinds of research or publications, refer to kinds of researchers required to achieve impact and engagement. Specifically, they argue the need for “public intellectuals” in the Information Systems Discipline. They identify three challenges to the production of impactful research: (i) researchers don’t know how to do such work, (ii) journals lack strategies for disseminating such work, and (iii) academic leaders lack strategies and processes to encourage such work. I hope Section ‘ISd-Research Strategy Publications’ above offers some guidance on how to amplify relevance and impact in research. As regards the Tarafdar et al. (2018) second challenge, a key aim herein has been to influence traditional outlets to be more receptive to such work by both attuning them to the need and value, and exploring (if not explicating outright) criteria for the evaluation of such work. Gill and Bhattacherjee (2009) suggest journals might introduce portfolio targets. JSIS, like other journals, is keen to promote more impactful research broadly; I invite both research that is “designed for impact”, and research that while not designed for impact from the outset, offers compelling interpretation pointing to potential future impactful outputs and outcomes. I hope too that this article engenders more programmatic research as described herein, a response to the Tarafdar et al. (2018) third challenge.

I believe the article offers ideas for several potential readers. For discipline leaders, those who are integrally involved in the oversight and nurturing of the IS discipline, there is little new here; perhaps the discussion suggests a framework around which current thinking might coalesce. For research quality gate-keepers – editors, reviewers, examiners – there is a strong plea to accommodate work pertaining to any of the five mechanisms of Fig. 2 , again with particular emphasis on strategic research programs. At the same time, I am acutely aware, and have been reminded by more than one of the senior scholars, that this plea is not new, and that the obstacles are several and complex (see endnotes).

For program leaders and aspirants to research program-leadership, the article raises many more issues than it solves. That said, it offers some argument for the creation of new, and sustenance of existing research programs, and I hope points the way to important thinking needed to promote improved programmatic research. For many Deans and Heads of School, and for research administrators in universities and governments whose policies strongly influence the course and focus of research, the call herein for more impactful research and the endorsement of research programs as a vehicle, will I expect be welcome.

For individual junior researchers, I apologize for only peripheral consideration of implications. Let it suffice here to suggest that individuals should carefully consider their personal and their projects' fit within the landscape of foci and consider their possible role(s) in programs. It is never too soon to be thinking strategically about who you seek to be: what you aspire to as a researcher. This should be a question asked of every commencing PhD student. Such a strategic orientation on career is all the more important in these uncertain times. For individual seasoned researchers the single message is, consider how in the current and projected climate you align with the other levels. Of course, many seasoned researchers do these things naturally.

Limitations

The emphasis throughout the discussion herein has been on research strategy, without explicitly extending this discussion to teaching and learning strategy. One might question whether it is possible to separate ISd Research Strategy from other discipline strategy, as they are to some degree intertwined. While inattention herein to those linkages may be considered a limitation, I believe ISd research strategy is sufficiently conceptually distinct to warrant separate consideration. “ Academic legitimacy comes with the salience of the subjects studied, the strength of the results obtained, and the plasticity of the field in responding to new challenges” ( King and Lyytinen, 2006 ). That being said, much of what is discussed here has broad relevance to the full discipline. There is merit in future work extending the discourse herein and shining a light on IS teaching and learning, viewing them through a discipline strategy lens [xxviii, xxix, xxx] .

A limitation of the Relevance Realisation Lifecycle view ( Fig. 3 ) is its inattention to what should be the focus across the lifecycle. Yes, relevance, but what more specifically? Rai (2019) argues that the focus across the phases should be problem formulation (which leads to the research question), thereby increasing chances of successfully addressing the dual objectives of scholarly and broa1er impact; and avoiding type III errors (addressing problems that don't matter) ( Rai, 2017a ). He goes further ( Rai, 2017b ) to suggest ways of abstracting the immediate problem to an archetypal problem (so the immediate problem is not over-problematized) and illuminating the distinctive characteristics of the immediate problem to challenge the archetypal problem (so the archetypal problem is not under-problematized). This guidance complements well the ideas of Fig. 3 . In an 'engaged scholarship' approach, engagement with practice is through the processes of problem formulation (which leads to the research question), theory development, research design, and solution assessment. One can argue that by engaging with practice in each of these phases (and doing other things to avoid Type III errors), the dual objectives of scholarly impact and broader impact are more likely to be realized.

I must accept the article is somewhat discipline-centric, with inadequate consideration of the university perspective, universities being the main vehicle of IS discipline research. Academics are members of both a discipline and a university. 20 Disciplines establish and enforce standards of research quality and research value, and universities encourage and facilitate research that meets those standards and delivers value. Historically, the main value sought has been contribution to knowledge. A key gauge of a university researcher's worth is their aggregate contributions to knowledge that meet the discipline standards. A key gauge of a university's research worth is the aggregate of its researchers' contributions to knowledge. Disciplinary involvement promotes training and growth in research standards and methods of their achievement, as well as breadth and depth in the discipline knowledge domain (involvement in the discipline has many other benefits, such as networking with other researchers). Regardless of individual university reward systems, stature within the discipline is perhaps the academic's main credential for advancement. There is however a “new normal”. Universities and disciplines have worked in tandem for over a century and their alignment needs attention.

This article makes no claim to inventorying the extensive, excellent disciplinary strategic advice to date from within the IS discipline. Fig. 2 offers the beginnings of a framework for usefully interrelating that work. Comprehensive inventorying, and interrelating that knowledge base within a coherent framework, is useful further research. The Strategic Methods node would undoubtedly benefit from a comprehensive revisiting of the IS literature (and beyond) to inventory and harmonize to the extent possible, extant methodological thought.

Though this article does not probe the merits and costs of research program involvement for individuals (a theme in the suggested follow-on work), implicit in the arguments is a strong belief in the efficiency and effectiveness of programmatic research; I think the potential for “a larger pie” is there. What isn't obvious is “how that pie gets shared”, which opens up much complexity. I think a general limitation of this article is that it generates expectations of answers while ultimately, in the main, only raising questions. Contrary, I think, to the view of one senior scholar, the article ends up being more descriptive than prescriptive. Lastly, I acknowledge I should have paid greater heed to the Hirschheim (2008) guidelines for the critical reviewing of conceptual papers, but practical realities intervened.

Future directions

The aims of this viewpoint are to espouse the merits of focusing a strategy lens on ISd-research, to facilitate related research and to call for future research in this direction. I believe a multilevel view of research strategy has the potential to be highly revealing, and is worthy of close future research attention. Reflecting back on the mechanistic view in Fig. 2 , I lament how the figure is inexplicit regarding the levels of research implied throughout the article. The discipline-level is clear as a sub-theme (ISd-Research strategy). Programs are explicitly accounted for as a mechanism (ISd-Research programs). Individuals however are only indirectly represented through projects or foci (ISd-Research Foci), and there is no explicit indication of multi-/inter-/trans-disciplinarity beyond disciplines. Shifting to a more multilevel view, I arrived at Table 2 , which cross-references levels of research with the five strategy mechanisms from Fig. 2 .

A Research Level and Strategy Mechanism Cross-Reference.

(a) I here adopt the British spelling where I refer more specifically to programmes as a 'level' as opposed to a mechanism, these being somewhat conflated prior.

It became clear that one can usefully consider the five mechanisms at each level, from: (i) individual, to (ii) programme, to (iii) discipline, iv) to x-disciplinary research (multi-/trans-/inter-disiciplinarity); perhaps worthwhile extending further to a higher 5th level – the ecology or society of research (e.g. Kuhn, 2012 ). I note also that programs are both a mechanism and a level (where levels are in essence groupings of people as in multilevel analysis – e.g. see ( Zhang and Gable, 2017 ).

I introduce Table 2 as an afterthought and suggest much interesting and valuable research could be pursued in attention to each of its cells. Such work, in the first instance, might entail inventorying pertinent thought to date. Such effort would likely be multidisciplinary, drawing from many disciplines. Rather than elaborating the individual cells of Table 2 and its full potential for encouraging further research and interrelating extant research, I make several selective observations. First, I note that extant methodological guidance pertains primarily to the individual project level. There is particular need for methods guidance at the program level; I recognise that multi-method and mixed-method guidance has some pertinence here, but much more is required.

Second, while I suggest the nexus of the individual level and governance pertains to “how individual research is governed”, I am of the view that individual research is largely self-governed. That said, both “how individuals govern their research” and “how their research is governed” are of interest to research organisers (e.g. program leaders/administrators). As mentioned, this article gives short shrift to the individual level, as it does to projects as a mechanism. While this scoping decision has to some extent been because, that level has to date received greater attention (e.g. in terms of methods guidance and our understanding of research projects), Table 2 reveals much need and further potential for attention to the individual level (e.g. How do researchers self-govern their research strategy?).

Beyond Table 2 , other areas of valuable further research are suggested herein. As a methodology for the design and execution of both research projects and programmatic research, there is value in employing the Relevance Realisation Lifecycle Model in Fig. 3 , while reflecting on and reporting on its merits (perhaps making a methodological contribution – mechanism C in Fig. 2 ).

As suggested earlier, with the swing to Mode 2 knowledge and growing emphasis on impact and engagement, discipline-university alignment requires attention. To the extent that discipline measures of stature and value are misaligned with university research goals and reward systems, academics and administrators experience conflict and productivity is compromised (some would argue university reward systems haven't evolved in lock-step with university and society aspirations for impact, thereby further exacerbating alignment). Disciplines and ISd have lagged in establishing measures of quality and value that promote impact. Thus, there is merit in assessing this alignment. Attention to this problem has been a major aim herein. More focused attention to ISd – University alignment is warranted, as are measures of rigour that encourage impact.

Further stretching the conception of “research as practice” there may be merit in analogizing other business concepts from industry (e.g. Business Models ( Fielt, 2014 )) to disciplines and research programs. I am herein talking about value and stakeholders. If programmatic research is to be strategic, it must consider the competition and its consumers and investors. Perhaps analogous with the notion of business model is 'research strategy model' (another example of reverse-cross-fertilization). Big data/data analytics is undoubtedly disrupting traditional (explicit and implicit) research strategy models. Some would argue that much of the contemporary data-driven research is too myopic and piecemeal, suggesting value from a more programmatic view; a new research strategy model.

It was argued earlier that discipline – university alignment is in need of attention. A premise of this argument is that disciplines continue to have value. There will be those who advocate that academics sole-allegiance should be to the university; a view I believe to be short-sighted and narrow. Discipline research standards are not static; rather they are constantly evolving, with new methods needed given new research phenomenon and technologies, a key role of the disciplines being to facilitate (and subsequently enforce) the evolution of new standards in lock step with the changing context, foci and priorities. Thus, any assumption that standards are established and the disciplines have served their role is misplaced.