National Museum of African American History & Culture

- Plan Your Visit

- Group Visits

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Accessibility Options

- Sweet Home Café

- Museum Store

- Museum Maps

- Our Mobile App

- Search the Collection

- Initiatives

- Museum Centers

- Publications

- Digital Resource Guide

- The Searchable Museum

- Exhibitions

- Freedmen's Bureau Search Portal

- Early Childhood

- Being Antiracist

- Community Building

- Historical Foundations of Race

- Race and Racial Identity

Social Identities and Systems of Oppression

- Why Us? Why Now?

- Digital Learning

- Strategic Partnerships

- Ways to Give

- Internships & Fellowships

- Today at the Museum

- Upcoming Events

- Ongoing Tours & Activities

- Past Events

- Host an Event at NMAAHC

- About the Museum

- The Building

- Meet Our Curators

- Founding Donors

- Corporate Leadership Councils

- NMAAHC Annual Reports

Whether we are aware of it or not, we are all assigned multiple social identities. Within each category, there is a hierarchy - a social status with dominant and non-dominant groups. As with race , dominant members can bestow benefits to members they deem "normal," or limit opportunities to members that fall into "other" categories.

A person of the non-dominant group can experience oppression in the form of limitations, disadvantages, or disapproval. They may even suffer abuse from individuals, institutions, or cultural practices. "Oppression" refers to a combination of prejudice and institutional power that creates a system that regularly and severely discriminates against some groups and benefits other groups.

We use the video player Able Player to provide captions and audio descriptions. Able Player performs best using web browsers Google Chrome, Firefox, and Edge. If you are using Safari as your browser, use the play button to continue the video after each audio description. We apologize for the inconvenience.

Systems of Oppression The term "systems of oppression" helps us better identify inequity by calling attention to the historical and organized patterns of mistreatment. In the United States, systems of oppression (like systemic racism) are woven into the very foundation of American culture, society, and laws. Other examples of systems of oppression are sexism, heterosexism, ableism, classism, ageism, and anti-Semitism. Society's institutions, such as government, education, and culture, all contribute or reinforce the oppression of marginalized social groups while elevating dominant social groups.

Social Identities A social identity is both internally constructed and externally applied, occurring simultaneously. Educators from oneTILT define social identity as having these three characteristics:

- Exists (or is consistently used) to bestow power, benefits, or disadvantage.

- Is used to explain differences in outcomes, effort, or ability.

- Is immutable or otherwise sticky (difficult, costly, or dangerous) to change.

Stop and Think!

Explore your own social identities [ view PDF ]

Learn More!

Download this fact sheet on privilege and oppression in American society from Kalamazoo College

There is no hierarchy of oppressions. Audre Lorde

Oppression causes deep suffering, but trying to decide whether one oppression is worse than others is problematic. It diminishes lived experiences and divides communities that should be working together. Many people experience abuse based on multiple social identities. Often, oppressions overlap to cause people even more hardship. This overlapping of oppressed groups is referred to as "intersectionality ." Legal scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw coined the term in the 1980s to describe how black women faced heightened struggles and suffering in American society because they belonged to multiple oppressed social groups.

Watch: A short video on black women and the concept of intersectionality. From the NMAAHC, #APeoplesJourney , "African American Women and the Struggle for Equality.”

During the time Crenshaw was articulating the concept of intersectionality, poet-scholar and social activist Audre Lorde warned America against fighting against some oppressions but not others. She insisted, "There is no hierarchy of oppression." All oppressions must be recognized and fought against simultaneously. She pushed American society to understand that although we possess different identities, we are all connected as human beings.

“So long as we are divided because of our particular identities we cannot join together in effective political action.”

Audre Lorde cautioned us about the ways that our various identities can prevent us from seeing our shared humanity. Why do you think she felt this was a danger to all people?

In American society, systems of oppression and their effects on people have a long, profound history. However, America and our society can change. As our country continues to evolve, we can acknowledge its problems and work to make changes for the better. We can join together to resist the status quo and the systemic barriers that exist to create new systems of justice, fairness, and compassion for us all.

To make this better America, each of us should look at our own privileges and power. Some people have more power or influence than others, and this can shift quickly according to circumstances . Do you enjoy power, privilege, or influence? If so, what do you do with it? Do you silently enjoy your moments of comfort? Or, do you take risks to stand in solidarity with others?

Take a moment to reflect

Let's Think

- “I learned a lot about systems of oppression and how they can be blind to one another by talking to black men. I was once talking about gender and a man said to me, ’Why does it have to be you as a woman? Why not you as a human being?’ This type of question is a way of silencing a person's specific experiences. Of course, I am a human being, but there are particular things that happen to me in the world because I am a woman.” - Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

- Why do you think Ngozi Adichie insisted on being able to talk directly about her specific identity as a woman?

- What identities are important to you that others don’t always acknowledge?

- It can be hard to talk about oppression no matter what side you find yourself on. However, these conversations are needed to develop a deeper understanding of the issues and prevent further harm. An effective way to enter into these kinds of conversations is by thinking through your own social identity.

- Do this “Social Identity Timeline Activity” with one or more people .

- Find relevant handouts here . Source: Resource adapted for use by the Program on Intergroup Relations, University of Michigan; Resource hosted by LSA Inclusive Teaching Initiative, University of Michigan .

- Share about the process of your identity formation with your partners using the discussion questions.

- WATCH: How the U.S. Suppressed Native American Identity

- How do you think individuals, institutions, and the dominant American society justified this cruel and inhumane treatment?

- What kept those who had power and voice (government officials, school teachers, civic leaders, regular citizens, etc.) from acknowledging the humanity of these children and preventing this atrocity?

- Banks connects historical oppression to current oppression faced by Native peoples. How can we join together as allies against this oppression?

- Work to be continuously self-reflective about your own privilege and power. Write self-reflections and revisit them so that you can seek out resources and supports to stop your own contributions to oppression.

- Be a Georgia Gilmore by joining with others in teaching, advocating, and organizing locally to dismantle systems of oppression where you are.

Why Us, Why Now?

Subtitle here for the credits modal.

Environment

Two concepts of oppression, there may be a more dangerous, all-pervasive threat than terrorism..

Posted November 27, 2014 | Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

The Oxford English Dictionary defines “oppression” as “the state of being subject to unjust treatment or control.” However, this does not mean that those subjected to unjust treatment or control are aware of it.

This is an aspect of oppression that is largely missed in popular culture when we consider whether we or others are being oppressed. Indeed, when living day to day in concert with the constraints of a given cultural milieu, we seldom consider whether we are actually being oppressed. Instead, we tend to think that one who wants to live according to the constraints of her culture is making a free choice.

In contrast, the usual scenario we think of when we think of oppression is that of someone who is captured, confined, tortured, or otherwise unjustly treated or controlled against his or her protests and pleas for freedom. Those who organize rebellions, or who would do so if they could, are thought to be oppressed. The internal resistance against apartheid in South Africa was viewed as a mark of oppression; while those who acquiesce in their cultural restrictions and taboos, and think none the worst of it, are typically considered free agents.

In United States history, one prominent example of the latter sort of “forced” oppression is that described by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, in 1848, in their influential book, The Communist Manifesto . Therein, Marx and Engels advanced their polemic against the power of capitalism to enslave the working class using the technology of mass production:

"Modern industry has converted the little workshop of the patriarchal master into the great factory of the industrial capitalist. Masses of laborers, crowded into the factory, are organized like soldiers … Not only are they slaves of the bourgeois class, and of the bourgeois State; they are daily and hourly enslaved by the machines, by the overlooker, and, above all, by the individual bourgeois manufacturer himself. The more openly this despotism proclaims gain to be its end and aim, the more petty, the more hateful and the more embittering it is."

In this image of wage slavery, the popular conception of exploitation is clearly illustrated wherein the masses of laborers are bound to an assembly line for an excessive amount of hours per day, under abominable working conditions, and given meager compensation. Indeed, Marx and Engel predicted that such egregious treatment of workers by rich capitalists would inevitably “produce its own gravediggers,” that is, explode into a bloody revolution.

Marx and Engel’s insight into the capacity of technology to oppress is one that should not be overlooked. While technology may itself be neutral, its deployment in this or that way, unconstrained by common sense and ethics , can be a means of exploitation and oppression. This should become abundantly clear in what I will say here. However, the dynamics of oppression is more complex than this popular model admits. Oppression is not necessarily obvious to those who are being oppressed; nor does it necessarily involve dissatisfaction or a tendency to rebel. This is because enculturation can be subtle, systematic, and not ordinarily called into question.

In 1861, in his seminal essay titled, “The Subjection of Women,” John Stuart Mill wrote about one such subtle form of enculturation:

"All causes, social and natural, combine to make it unlikely that women should be collectively rebellious to the power of men ... All men, except the most brutish, desire to have, in the woman most nearly connected with them, not a forced slave but a willing one, not a slave merely, but a favorite. They have therefore put everything in practice to enslave their minds."

Here is a different concept of oppression in contrast to the Marxian one, that of “willing” rather than “forced” slavery. Indeed, a significant number of women living in the United States today (those who have what social workers call a “victim mentality”) still believe they are lucky to be under the control of men who treat them abusively or like possessions.

Willful oppression can take many and sundry subtle forms, some of which even liberal thinkers like Marx and Mill did not foresee. Marx thought that oppression largely involved the consciousness of being forced into living an undesirable life. Mill identified willful oppression but focused on gender -specific oppression, that of the subjection of women by men. But what of willful oppression of the masses, across cultural divides, spanning the “developed” or industrialized world? Is this sort of ubiquitous, willful oppression possible?

Currently, a large percentage of people living in the industrialized “free” world are also members of a global commons in cyberspace. While the servers of this global online community are located inside national borders, the virtual space that this equipment generates transcends any of these geographical boundaries . Nevertheless, the participants of this online global culture have, for the most part, accepted, and assumed, the terms of going online. These terms have been dictated largely by Internet gatekeepers such as Comcast, Verizon, and AT&T, working in cooperation with governmental agencies, in particular, the United State’s National Security Agency (NSA) and Great Britain’s Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ).

Most of us, by now, accept and assume that all of our personal messages, including telephone and email messages, will be filtered and stored in giant government databases. Some of us, perhaps a large majority, accept this suspension of privacy because we think it makes us safer from terrorist attacks. Others assume that whatever the government does must be right. Still others are simply unaware or in disbelief that any abridgment of privacy actually exists or poses a serious threat to civil liberties or personal freedom. Of course, there are also some who do not think privacy is even important in the first place. But all these views involve largely unexamined assumptions. This is unfortunate since, as Socrates starkly expressed, “the unexamined life is not worth living,” and in our high tech milieu, this may be truer today than it was in ancient Athens.

Mill urged us to examine our assumptions about the willful oppression of one sector of our society, namely those who are female. True, we have not yet cast off these chains (there still isn't pay equity, and the number of women still is not equally represented in higher management —including the office of U.S. President—and in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) positions). However , there has been substantial progress toward liberation as a result of affirmative action and related conscious attempts to eliminate oppressive social practices. Without such conscious awareness and effort to challenge cultural assumptions, such progress would have been nil.

It is no different, in principle, with respect to our assumptions about privacy in cyberspace. Unless we actively examine the assumptions governing our freedom (or loss thereof) in cyberspace, we are likely to fall deeper and deeper into a systematic regimen of quietly creeping, ever-expanding oppression. So, a s the technology becomes more and more able to oppress, will we be just as complacent with future, successive encroachments on our privacy?

According to Intel Corporation, in the next decade, the new Bluetooth connection to the internet will be through Brain Computer Interfaces ( BCIs ), which will connect your brain via electrodes directly to the internet. In this environment, your thoughts, not merely the words you type on a keyboard or handheld device, or your voice over a wireless connection, will be online. Your deepest thoughts and most personal secrets will be open to inspection. In this brave new world, government will have the ability (and the authority) to, quite literally, read your mind.

This sort of threat, more than even terrorism, devours the very core of what it means to be human! Will you be as willing to have a cookie implanted in your brain as you are, presently, to have one implanted in your computer?

Oppression cannot only be subtle; it can also be gradual. It can develop over time, in progressive installments, not all at once. The most likely scenario is that we will not wake up one morning and discover that we no longer have any freedom of thought and expression. More likely, we will never come to realize just how oppressed we really have become.

Do you know how far the government has already gone down this slippery slope toward oppressing your freedom of thought and expression? How much research has been spent in developing more powerful forms of surveillance technologies? How little time and money government has invested in trying to protect your privacy from unjust encroachment? What evidence there is that the current surveillance system is really helping to stop terrorism? What the rate of false positives generated by this system really is? What business interests, in particular, are driving the development of surveillance technologies? How much do you actually know, based on evidence, not just government propaganda, about these and other things? How much are you just assuming?

In my latest book, Technology of Oppression: Preserving Freedom and Dignity in an Age of Mass Warrantless Surveillance , I have attempted to carefully trace the history of surveillance, beginning in the late 1960s with the emergence of satellite technologies, and the mounting changes from analog data transmission along copper lines to digital data transmission along fiber optic cables, as well as the Defense Advanced Research Project Agency’s (DARPA's) newly emerging, patented, BCI technologies. I have discussed the incredible progress that has been made in the power of “deep packet” analysis, from the early Narus technologies deployed during the George W. Bush administration to the profoundly greater data processing capabilities of some of the latest technologies. I have carefully examined the evidence regarding the ability of the latest technology to detect terrorist plots with respect to the government’s telephone metadata programs as well as its “upstream programs” such as PRISM, as well as some of its less known (and non-legally regulated) programs such as MUSCULAR. I have examined the algorithms used for calculating the rate of false positives generated by such technologies. I have compared the success of these programs with that of conventional investigations. I have examined the pertinent iterations of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) in connection with the legality of current government data collections as well as the progress of the FIS Court's success in legal oversight (or the lack thereof). Toward ameliorating problems inherent in the present system of surveillance, I have proposed ways for attaining greater transparency about government control of cyberspace, including establishing a global internet forum in which the people of the world can receive information and provide input into the policies that shape their freedom in cyberspace. Toward this end, I have done preliminary work in drafting a set of model rules for regulating network surveillance, which consists of proposed legal and technological constraints on the infrastructure currently being deployed. In brief, I have begun the process of carefully examining many commonplace assumptions about the control of cyberspace instead of just passively accepting them.

This is the second book I have written on this subject. In the aftermath of the Edward Snowden leaks, I discussed the idea of updating my first book with its publisher, Palgrave Macmillan, but, instead, my editor invited me to write a new book. I have worked with parsing technologies for many years, not just as an ethicist but also as an inventor of patented technology aimed at protecting privacy in electronic communications. Given my background, I perceived a moral duty to write this new book. For me personally, it was an opportunity to examine my own assumptions about the current system of surveillance and its potential for oppression. I have tried to do my civic duty. Indeed, all of us should carefully educate ourselves and to examine our assumptions, if we have not already done so.

Unless we change our idea about what oppression is and can be; and, unless we take a rational, cautious, evidence-driven inventory of our assumptions, collectively as a global community, and individually as citizens, we may never come to know just how oppressed we really are, and may soon be.

Elliot D. Cohen, Ph.D. , is the president of the Logic-Based Therapy and Consultation Institute and one of the principal founders of philosophical counseling in the United States.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

At any moment, someone’s aggravating behavior or our own bad luck can set us off on an emotional spiral that could derail our entire day. Here’s how we can face triggers with less reactivity and get on with our lives.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

Beyond Intractability

The Hyper-Polarization Challenge to the Conflict Resolution Field We invite you to participate in an online exploration of what those with conflict and peacebuilding expertise can do to help defend liberal democracies and encourage them live up to their ideals.

Follow BI and the Hyper-Polarization Discussion on BI's New Substack Newsletter .

Hyper-Polarization, COVID, Racism, and the Constructive Conflict Initiative Read about (and contribute to) the Constructive Conflict Initiative and its associated Blog —our effort to assemble what we collectively know about how to move beyond our hyperpolarized politics and start solving society's problems.

By Morton Deutsch

March 2005 with "Current Implications" by Heidi Burgess added in July 2020.

Current Implications

I am writing this section in the summer of 2020, a little over a month after George Floyd was killed by police in Minnesota, and during the resulting world-wide protests about that event and oppression of Blacks and other racial groups. The protestors—and the people responding to them—would be well advised to read this essay, because it shows how deep the problem of minority oppression is. It isn't just a few racially-biassed police; it isn't all police; and it isn't going to be fixed by "defunding" or even reforming the police. It needs to go much deeper than that.

Just look at Deutsch's categories in this essay: More...

| This post is also part of the

|

I consider here five types of injustices that are involved in oppression : distributive injustice , procedural injustice , retributive injustice , moral exclusion , and cultural imperialism . To identify which groups of people are oppressed and what forms their oppression takes, each of these five types of injustice should be examined.

1. Distributive Injustice

Under this heading, I shall briefly consider the distribution of four types of capital -- consumption, investment, skill, and social.[1]

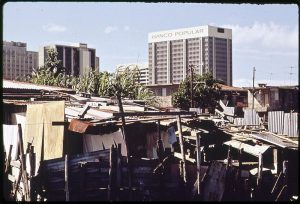

Consumption capital is usually thought of as "standard of living." In industrial societies, this is very much related to income. It includes the amounts and types of food and clean water, housing, clothing, health care, education, physical mobility (such as travel), recreation, and services that are available to members of a group. Clearly, there are gross differences in income and standard living among the different nations, among the different ethnic groups within nations, among the different classes, and between the sexes. For example, compare Sudan with Canada, African Americans with Euro-Americans, employees of General Motors and its executives, males and females.

Sen, for example writes: "women tend in general to fare quite badly in relative terms compared to men, even within the same families. This is reflected not only in such matters as education and opportunity to develop talents, but also in the more elementary fields of nutrition, health, and survival." He estimated that there are "more than a hundred million missing women," in Asia and North Africa, as a result of the unequal deprivations they suffer, compared to men. In other words, the survival rates of women compared to men is considerably lower than could be expected when these are compared to the relative survival rates of men and women in Europe, North America, and sub-Saharan Africa where the differences in consumption capital available to males and females is not as unequal.[2]

Investment capital "is what people use to create more capital". Income is related to consumption capital and, also, wealth, which in turn, is related to investment capital. Generally, wealth is distributed more unequally than income. The inequalities among nations, within nations, among ethnic groups, among the social classes, between the physically impaired and unimpaired, and between the sexes are apt to be considerably greater with regard to investment than consumption capital. In 1992 in the US, the top one percent of the population possessed 45.6% of the financial assets while the bottom 80 percent had only 7.8%, and this discrepancy has undoubtedly increased since then.[3] {Indeed The Pew Research Center reported in 2020 that the median wealth of upper income families went up 33% between 2001 and w016, while middle-income families' net work shrunk 20% and lower-income families' net worth lost 45%. "As of 2016, upper-income families had 7.4 times as much wealth as middle-income families and 75 times as much wealth as lower-income families. These ratios are up from 3.4 and 28 in 1983, respectively." [10]}

Skill capital is the specialized knowledge, social and work skills, as well as the various forms of intelligence and credentials that are developed as a result of education and training and experiences in one's family, community, and work settings. As Perrucci and Wysong point out: "The most important source of skill capital in today's society is located in the elite universities that provide the credentials for the privileged class. For example, the path into corporate law with six-figure salaries and million-dollar partnerships is provided by about two-dozen elite law schools where children of the privileged class enroll. Similar patterns exist for medical school graduates, research scientists, and those holding professional degrees in management and business... People in high-income and wealth-producing professions will seek to protect the market value not only for themselves, but also for their children, who will enter similar fields." It is evident that those in non-privileged groups in many societies will have much less opportunity to enter elite universities and to acquire the skills and credentials which would have high market value.[4]

Social capital is the network of social ties (family, friends, neighbors, social clubs, classmates, acquaintances, etc.), which can provide information and access to jobs and to the means of acquiring the other forms of capital, as well as emotional and financial support. It is the linkage that one has or does not have to organizational power, prestige, and opportunities. The social capital that one can acquire and maintain is affected by such factors as one's family's social class, membership in particular ethnic and religious groups, age, sex, physical disability, and sexual orientation. In most societies the ability to acquire and maintain social capital by those who are underclass or working class, disabled, elderly, members of minority, ethnic, religious of racial groups, or women is considerably more limited than the dominant groups. Personality, undoubtedly, also plays a role: one could expect that individuals who are ambitious, sociable, intelligent, and personally attractive will acquire more social capital than those who are not.

To sum up this section on distributive justice: "Every type of system -- from a society to a family -- distributes benefits, costs, and harms (its reward systems are a reflection of this). One can examine the different forms of capital (consumption, investment, skill, social) and such benefits as income, education, health care, police protection, housing, and water supplies, and such harms as accidents, rapes, physical attacks, imprisonment, death, and rat bites, and see how they are distributed among categories of people: rich versus poor, males versus females, employers versus employees, whites versus blacks, heterosexuals versus homosexuals, police officers versus teachers, adults versus children. Such examination reveals gross disparities in distribution of one or another benefit or harm received by the categories of people involved. Thus, Blacks generally received fewer benefits and more harm than Whites in the United States. In most parts of the world, female children are less likely than male children to receive as much education or inherit parental property, and they are more likely to suffer from sexual abuse."[5]

2. Procedural Injustice

In addition to assessing the fairness of the distribution of outcomes, individuals judge the fairness of the procedures that determine the outcomes. Research evidence indicates that fair treatment and procedure are a more pervasive concern to most people than fair outcomes. Fair procedures are psychologically important, because they encourage the assumption that they give rise to fair outcomes in the present and will also in the future. In some situations, where it is not clear what "fair outcomes" should be, fair procedures are the best guarantee that the decision about outcomes is made fairly. Research indicates that one is less apt to feel committed to authorities, organizations, social policies, and governmental rules and regulations if the procedures associated within them are considered unfair. Also, people feel affirmed if the procedures to which they are subjected treat them with the respect and dignity they feel is their due; if so treated, it is easier for them to accept a disappointing outcome.

Questions with regard to the justice of procedures can arise in various ways. Let us consider, for example, evaluation of teacher performance in a school. Some questions immediately come to mind: Who has "voice" or representation in determining whether such evaluation is necessary? How are the evaluations to be conducted? Who conducts them? What is to be evaluated? What kind of information is collected? How is its accuracy and validity ascertained? How are its consistency and reliability determined? What methods of preventing incompetence or bias in collecting and processing information are employed? Who constitutes the groups that organize the evaluations, draw conclusions, make recommendations, and make decisions? What roles do teachers, administrators, parents, students, and outside experts have in the procedures? How are the ethicality, considerateness, and dignity of the process protected?

Implicit in these questions are some values with regard to procedural justice. One wants procedures that generate relevant, unbiased, accurate, consistent, reliable, competent, and valid information and decisions as well as polite, dignified, and respectful behavior in carrying out the procedures. Also, voice and representation in the processes and decisions related to the evaluation are considered desirable by those directly affected by the decision. In effect, fair procedures yield good information for use in the decision-making processes as well as voice in the processes for those affected by them, and considerate treatment as the procedures are bring implemented.[6]

One can probe a system to determine whether it offers fair procedures to all. Are all categories of people treated with politeness, dignity, and respect by judges, police, teachers, administrators, employers, bankers, politicians and others in authority? Are some but not others allowed to have a voice and representation, as well as adequate information, in the processes and decisions that affect them?

It is evident that those people and groups with more capital are more likely to have access to political leaders and to be treated with more respect by the police, judges, and other authority than those with less capital. Also, their ability to have "voice" in matters that affect them are considerably greater.

3. Retributive Injustice

Retributive injustice is concerned with the behavior and attitudes of people, especially those in authority, in response to moral rule breaking. One may ask: Are "crimes" by different categories of people less likely to be viewed as crimes, to result in an arrest, to be brought to trial, to result in conviction, to lead to punishment or imprisonment or the death penalty, and so on? Considerable disparity is apparent between how "robber barons" and ordinary robbers are treated by the criminal-justice system, between manufacturers who knowingly sell injurious products (obvious instances being tobacco and defective automobiles) and those who negligently cause an accident. Similarly, almost every comparison of the treatment of black and white criminal offenders indicate that, if there is a difference, blacks receive worse treatment.

4. Moral Exclusion

Moral exclusion refers to: who is and is not entitled to fair outcomes and fair treatment by inclusion or lack of inclusion in one's moral community? Albert Schweitzer included all living creatures in his moral community, and some Buddhists include all of nature. Most of us define a more limited moral community.

Individuals and groups who are outside the boundary in which considerations of fairness apply may be treated in ways that would be considered immoral if people within the boundary were so treated. Consider the situation in Bosnia. Prior to the breakup of Yugoslavia, the Serbs, Muslims, and Croats in Bosnia were more or less part of one moral community and treated one another with some degree of civility. After the start of civil strife, (initiated by power-hungry political leaders), vilification of other ethnic groups became a political tool, and it led to excluding others from one's moral community. As a consequence, the various ethnic groups committed the most barbaric atrocities against one another. The same thing happened with the Hutus and Tutsis in Rwanda and Burundi.

At various periods in history and in different societies, groups and individuals have been treated inhumanly by other humans: slaves by their masters, natives by colonialists, blacks by whites, Jews by Nazis, women by men, children by adults, the physically disabled by those who are not, homosexuals by heterosexuals, political dissidents by political authorities, and one ethnic or religious group by another.

When a system is under stress, are there differences in how categories of people are treated? Are some people more apt to lose their jobs, be excluded from obtaining scarce resources, or be scapegoated and victimized? During periods of economic depression, social upheaval, civil strife, and war, frustrations are often channeled to exclude some groups from the treatment normatively expected from other in the same moral community.

Moral exclusion "is perhaps the most dangerous form of oppression." It has led to genocide against the Jews and gypsies by the Nazis, the Turkish genocide of the Armenians, the auto genocide by the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia, the mass killings of the political opposition by the Argentinean generals, to widespread terrorism against civilians by various terrorist groups, to the enslavement of many Africans, to mention only a few examples of the consequences of moral exclusion.[7]

Lesser forms of moral exclusions, marginalization, occur also against whole categories of people: women, the physically impaired, the elderly, and various ethnic, religious and racial groups in many societies where barriers prevent them from full participation in the political, economic, and social life of their societies. The results of these barriers are not only material deprivation but also disrespectful, demeaning, and arbitrary treatment as well as decreased opportunity to develop and employ their individual talents. For extensive research and writing in this area, the work of Susan Opotow, a leading scholar in this area.[8]

5. Cultural Imperialism

" Cultural Imperialism involves the universalization of a dominant group's experience and culture and establishing it as the norm.". Those living under cultural imperialism find themselves defined by the dominant others. As Young points out: "Consequently, the differences of women from men, American Indians or Africans from Europeans, Jews from Christians, becomes reconstructed as deviance and inferiority." To the extent that women, Africans, Jews, Muslims, homosexuals, etc. must interact with the dominant group whose culture mainly provides stereotyped images of them, they are often under pressure to conform to and internalize the dominant group's images of their group.[9]

Culturally dominated groups often experience themselves as having a double identity, one defined by the dominant group and the other coming from membership in one's own group. Thus, in my childhood, adult African-Americans were often called "boy" by members of the dominant white groups but within their own group, they might be respected ministers and wage earners. Culturally subordinated groups are often able to maintain their own culture because they are segregated from the dominant group and have many interactions within their own group, which are invisible to the dominant group. In such contexts, the subordinated culture commonly reacts to the dominant culture with mockery and hostility fueled by their sense of injustice and of victimization.

Note: This was originally one long article on oppression, which we have broken up to post on Beyond Intractability . The next article in the series is: Maintaining Oppression .

Just look at Deutsch's categories in this essay:

- Distributive Injustice: This means that goods and services are distributed unevenly. That's overwhelmingly true in the United States. Blacks (and several other minorities) live in poor neighborhoods that don't have remotely adequate schools, housing, transportation, or access to good jobs. Their educational achievement lags far below whites, their jobs (when they can get them) pay worse that the jobs whites get, consequently their incomes are much lower than white incomes and their ability to accumulate wealth is a small fraction of White's ability to accumulate wealth. They also lag far behind in what Deutsch calls "social capital"—the connections needed to do well. (That is not to say that there aren't poor Whites who also suffer from all of these issues, but on average, Blacks have much poorer access to goods, services, income and wealth than do Whites.)

Not only is this unfair in and of itself, unfair treatment also diminishes the victims' trust in the "system," willingness to respect authorities, and work "within the system." If you don't think that "the system" will treat you fairly, why try to get what you want or need by "working within the system?" This is explained in more detail in a recent CCI Blog post about Gil Pompa's "two taproot theory" of racial conflicts. Gil Pompa is a former director of the U.S. Justice Department's Community Relations Service. He said that in racial conflicts, "there are two taproots growing simultaneously. One is a perception or belief of unfair treatment or discrimination. The other is a lack of confidence in any redress system. There is the belief that, "Even if I complain, it is not going to make a difference." And those two beliefs (or taproots) are growing in force, side-by-side." Add a "triggering incident," and you can get an explosion. (I'll link to a longer explanation of this, once it is posted.) But suffice it to say here that the one taproot is distributive injustice, the second procedural injustice, and the two together are particularly dangerous.)

- Moral Exclusion: Moral exclusion is a huge problem now, as well, but it is not as much an issue of race alone. Rather the moral exclusion that is most prevalent now is between the U.S. political parties. This is evident by attitudes toward marriage: in the 1950s, only 4% of Americans approved of interracial marriages between blacks and whites; in 2016, the number was up to 87%.[11] Twenty five years ago, 60% Americans disapproved of same-sex marriage; now 61% approve of it. [12] But attitudes about cross-political marriages are much more harsh:

In 1958, “33 percent of Democrats wanted their daughters to marry a Democrat, and 25 percent of Republicans wanted their daughters to marry a Republican,” Vavreck writes. “But by 2016, 60 percent of Democrats and 63 percent of Republicans felt that way.”

What Deutsch said in 2005 remains true today:

Is it impossible to imagine mass violence by one party against the other, or one race against another in the United States? One need only to look at the treatment of LatinX immigrants on the border during the Trump administration to see an answer to that question! [13]

- Cultural Imperialism: The last category that Deutsch lists is cultural imperialism, when one culture insists that its cultural norms and beliefs must be be followed by everyone. Republicans charge that this is what is happening with "political correctness," and now, more recently, with the "cancel culture" that they say liberals are using to shame, ostracize, and disempower anyone who is not (or wasn't in the long-lost past) adequately politically correct or "woke." Conversely, the political right has been trying to force its sexual morality on the left through abortion restrictions and religious restrictions on access to birth control.

We are not going to be able to adequately address racism in this country until we grapple with all five of these forms of oppression, and we need to address them not just for Blacks, but for all oppressed people.

Back to Essay Top

[1]Perrucci, Robert and Wysong, Earl (1999). The New Society . Lanham : Rowman & Littlefield.

[2] Dreze, Jean and Sen, A. (1995). India : economic development and social opportunity. Delhi ; New York : Oxford University Press, chapter 7, p.140.

[3]Perrucci, Robert and Wysong, Earl (1999). The New Society . Lanham : Rowman & Littlefield, p.10, 13.

[4]Perrucci, Robert and Wysong, Earl (1999). The New Society . Lanham : Rowman & Littlefield, p.14.

[5] Deutsch, M. and Coleman, P.T. (2000). The handbook of conflict resolution: Theory and Practice. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, p. 56.

[6] Deutsch, M. and Coleman, P.T. (2000). The handbook of conflict resolution: Theory and Practice. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, p.44-45.

[7] Young, M.I. (1990). Justice and the politics of difference . Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, p.53.

[8] Opotow, S.V. (1987). Limits of fairness: An experimental examination of antecedents of the scope of justice . Ann Arbor, MI: University Microfilms International, Dissertation Information Service. Order #8724072. [ Dissertation Abstracts International, 48 (08B), 2500.]

Opotow, S.V. (1990). Deterring moral exclusion: A summary. Journal of Social Issues, 46 (1), 173-182.

Opotow, S.V. (1995). Drawing the line: Social categorization, moral exclusion, and the scope of justice. In B.B. Bunker & J.Z. Rubin (Eds.), Conflict, cooperation, and justice (pp. 347-369). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Opotow, S.V. (1996). Is justice finite? The case of environmental inclusion. In L. Montada & M. Lerner (Eds.), Social justice in human relations: Current societal concerns about justice, Vol. 3 (pp. 213-230). New York: Plenum Press.

Opotow, S.V. (1996). Affirmative action, fairness, and the scope of justice. Journal of Social Issues, 52 (4), 19-24.

Opotow, S.V. (2001). Social injustice. In D.J. Christie, R.V. Wagner, and D.D. Winter (Eds.), Peace, conflict and violence: Peace psychology for the 21 st century (pp. 102-109). New York: Prentice-Hall

[9] Young, M.I. (1990). Justice and the politics of difference . Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, p.59.

[10] Juliana Mesasce Horowitz, Ruth Igielnik, and Rakesh Kochhar, " Trends in Income and Weath Inequality." Pew Research Center Social and Demographic Trends. Jan. 9.2020.

[11] Kevin Enochs " In US, 'Interpolitical' Marriage Increasingly Frowned Upon" Voice of America News. Feb. 3, 2017. https://www.voanews.com/usa/us-interpolitical-marriage-increasingly-frowned-upon Accessed July 3, 2020.

[12] "Attitudes on Same-Sex Marriage" Pew Research Center. May 14, 2019. https://www.pewforum.org/fact-sheet/changing-attitudes-on-gay-marriage/ Accessed July 3, 2020.

[13] See, for instance the Amnesty International article, "U.S.A: 'You dont have any rights here.' https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/research/2018/10/usa-treatment-of-asylum-seekers-southern-border/ .

Use the following to cite this article: Deutsch, Morton. "Forms of Oppression." Beyond Intractability . Eds. Guy Burgess and Heidi Burgess. Conflict Information Consortium, University of Colorado, Boulder. Posted: March 2005 < http://www.beyondintractability.org/essay/forms-of-oppression >.

Additional Resources

The intractable conflict challenge.

Our inability to constructively handle intractable conflict is the most serious, and the most neglected, problem facing humanity. Solving today's tough problems depends upon finding better ways of dealing with these conflicts. More...

Selected Recent BI Posts Including Hyper-Polarization Posts

- Democracy Lighthouse + More on Communicating with Friends and Family -- Sharing several new ideas that have come to us recently on controlling affective polarization and threats to democracy from the family level on up.

- Massively Parallel Peace and Democracy Building Links for the Week of June 23, 2024 -- More useful and interesting reading from colleagues and others in allied fields.

- Democratic Subversion - Part 2 -- Part 2 of 2 newsletters looking at an old, but eerily accurate, description of political events in the United States over the last ten-twenty years, explaining why we are well on our way to a destroyed democracy and what we can do about it.

Get the Newsletter Check Out Our Quick Start Guide

Educators Consider a low-cost BI-based custom text .

Constructive Conflict Initiative

Join Us in calling for a dramatic expansion of efforts to limit the destructiveness of intractable conflict.

Things You Can Do to Help Ideas

Practical things we can all do to limit the destructive conflicts threatening our future.

Conflict Frontiers

A free, open, online seminar exploring new approaches for addressing difficult and intractable conflicts. Major topic areas include:

Scale, Complexity, & Intractability

Massively Parallel Peacebuilding

Authoritarian Populism

Constructive Confrontation

Conflict Fundamentals

An look at to the fundamental building blocks of the peace and conflict field covering both “tractable” and intractable conflict.

Beyond Intractability / CRInfo Knowledge Base

Home / Browse | Essays | Search | About

BI in Context

Links to thought-provoking articles exploring the larger, societal dimension of intractability.

Colleague Activities

Information about interesting conflict and peacebuilding efforts.

Disclaimer: All opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Beyond Intractability, the Conflict Information Consortium, or the University of Colorado.

Beyond Intractability Essay Copyright © 2003-2017 The Beyond Intractability Project, The Conflict Information Consortium, University of Colorado; All rights reserved. Content may not be reproduced without prior written permission. All Creative Commons (CC) Graphics used on this site are covered by the applicable license (which is cited) and any associated "share alike" provisions.

"Current Implications" Sections Copyright © 2016-17 Guy Burgess and Heidi Burgess All rights reserved. Content may not be reproduced without prior written permission.

Guidelines for Using Beyond Intractability resources. Inquire about Affordable Reprint/Republication Rights .

Citing Beyond Intractability resources.

Photo Credits for Homepage and Landings Pages

Privacy Policy

Contact Beyond Intractability or Moving Beyond Intractability The Beyond Intractability Knowledge Base Project Guy Burgess and Heidi Burgess , Co-Directors and Editors c/o Conflict Information Consortium , University of Colorado 580 UCB, University of Colorado, Boulder, CO 80309, USA -- Phone: (303) 492-1635 -- Contact

Powered by Drupal

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

9 Oppression and Power

Geraldine L. Palmer; Jesica Siham Ferńandez; Gordon Lee; Hana Masud; Sonja Hilson; Catalina Tang; Dominique Thomas; Latriece Clark; Bianca Guzman; and Ireri Bernai

Chapter Nine Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Explain the concepts and theories of oppression and power

- Describe the intersection of oppression and power

- Identify strategies used by community psychologists and allies to address oppression and power

“Healing begins where the wound was made.”

-Alice Walker ( The Way Forward is With a Broken Heart)

Community Psychology has grown up amidst times in US history and throughout the world where social change has been the interwoven thread throughout urban and suburban spaces. Social change continues to be the thread we must use to construct new realities. Not uncommon, as community psychologists have discovered over the past few years, social change work can often be more effective starting at the community level and then branching outward to macrosystems.

“….the definition and critical analysis of oppression has left out the complexity, voices and lived experiences of individuals who have been severely impacted by injustice and oppression…” – bell hooks (1994) Macrosystems include influences of governmental policies, corporations, and belief systems. To this end, having a firm understanding of the dynamics that challenge communities is critical. This understanding must extend to grappling with some of the more unjust practices such as oppression and power that have influenced and shaped many of our communities today, particularly where members are people of color. The purpose of this chapter is to introduce the interrelated concepts of oppression and power and explore their relationship to the health and well-being of communities. We conceptualize oppression and power in upcoming sections. First, we give an overview of what oppression is. Second, we discuss the concept of power. Third, we discuss the relationship between oppression and power, because they typically never act alone. Fourth, we look at methodologies to deconstruct oppression and power. Finally, we offer strategies that can, and are, used in Community Psychology practice.

This chapter expands on the discussion of oppression and power in Chapter 1 (Jason et al., 2019) and other current Community Psychology textbooks, primarily through the lens of those who have been and continue to be oppressed. Broadly defined through theoretical and abstract concepts, the definition and critical analysis of oppression have left out the complexity, voices, and lived experiences of individuals who have been severely impacted by injustice and oppression. Our ways of knowing and being are credible and of critical importance to students learning how knowledge and power are created and what evidence is most credible in discussing them. We also include information that portrays the strength and resiliency of community members as a balance to the scholarship. The authors’ perspectives and inclusion of the lived experiences of others will add richness and depth to your studies.

JUST WHAT IS OPPRESSION?

Oppression is defined in Merriam-Webster dictionary as: “Unjust or cruel exercise of authority or power especially by the imposition of burdens; the condition of being weighed down; an act of pressing down; a sense of heaviness or obstruction in the body or mind”. This definition demonstrates the intensity of oppression, which also shows how difficult such a challenge is to address or eradicate. Further, the word oppression comes from the Latin root primere , which actually means “pressed down”. Importantly, we can conclude that oppression is the social act of placing severe restrictions on an individual, group, or institution.

Moreover oppression is often discussed in the same context as the terms “ dehumanization ” and “ exploitation ”. These are terms that portray unjustness and cruelty. To adequately prepare you to effectively address the challenges many communities are facing, we include the terms to help familiarize you with what oppression feels like to the receiver. Understanding the perceptions, meanings, and experiences of community members is critical for work in Community Psychology in order to address social issues such as oppression. The excerpt below gives an example of a person, who also happens to be a community psychologist, describing their lived oppressive experiences:

Case Study 9.1 A Personal Communication

“…I felt this fullness, unexplainable presence, inner pain but it was not tangible, almost like a phantom ache or pain, that sensation a person has when they have lost a limb and it feels like it is still there but it hurts. It filled my body. I was grief-stricken. Sad. I felt that I, WE, THEY, have let our children down. Our Village is no longer protecting our children. That sacred piece of our legacy.

If I can take accountability or acknowledge this wrong, why doesn’t our oppressor? What is the value in destroying a child, a people, their dreams? It is mean, evil, greedy, disastrous, ugly, devilish, and immoral. It is every gunshot into the backs of Black men. It is an assassination of the human spirit. It rapes us of our purpose. Our young people should never, never feel uncared for, unwanted or invisible….

I bow my head with my hands over my ears and I sit in silence. I realize that these feelings have been sitting dormant…”

(-J. Samuel, personal communication, 2018)

It is important to note that while we are providing you with a framework of oppression and power, we will also provide you with examples of action strategies for how community psychologists and allies are supporting the resiliency in communities so that you can feel encouraged to discover your own way into combating oppression.

WHY OPPRESSION?

After studying the concept of oppression, you might be asking- what is the reason for oppression? Typically, a government or political organization that is in power places these restrictions formally or covertly on groups so that the distribution of resources is unfairly allocated—and this means power stays in the hands of those who already have it (a discussion on power follows this section). We understand that oppression occurs when individuals are systematically subjected to political, economic, cultural, or social degradation because they belong to a certain social group—this results from structures of domination and subordination and, correspondingly, ideologies of superiority and inferiority.

According to decolonial theory , over the last 500 years, the colonial matrix of power , patron colonial de poder has been and is one of the primary sources of oppression. Decolonial theory uses a framework that attempts to answer questions pertaining to knowledge, coloniality, and globalization. The “western world” is a production of coloniality and modernity. The latter two terms refer to the socio-cultural norms developed after the 18th century and the chapter in European history known as the Enlightenment. It is defined loosely by industrialization, science, division of labor, capitalism, secularism, education, and liberalism (Smith, 1999). Further western modernity created and constructed the idea of ‘race’ as a biological function, as part of a narrative to indicate the superiority of the white race and the inferiority of all other races (peoples). Western modernity and the colonial matrix of power have constructed a particular place: the West. Read more about the nature and origin of oppression here .

PSYCHOLOGICAL IMPLICATIONS OF OPPRESSION

Oppression is described in psychology as states and processes that include psychological and political components of victimization, agency, and resistance where power relations produce domination, subordination, and resistance (Prilleltensky, 2003). The oppressed group suffers greatly from multiple forms of exclusion, exploitation, control, and violence. The literature on the psychological impact of oppression suggests that the erasure and removal of intrinsic cultural identities influenced by oppressive practices can lead to negative outcomes such as “ internalization of negative group identities and low self-esteem . ”

In understanding psychology of oppression , the oppressed initially adopt “ avoidance reactions ” which are responses that prevent adverse outcomes from occurring. This happens before one truly internalizes the ideologies of the oppressor, which ultimately results in engaging in self-destructive behaviors before reaching the point of internalized racism . and assimilation. Lastly, oppression is not a static concept nor does it have a fixed relationship to racism and discrimination. It changes and can be extremely non-transparent—both covert and overt. The tools of oppression are often disguised or hidden as privileges. Read more here on the impact of oppression and power on communities of color. Case Study 9.2 below provides a number of factors indicative of the impact of oppression from political, economic, and socio-cultural factors on one community in Chicago, IL.

Case Study 9.2 Englewood: Struggling to Rise

Once known as Junction Grove, the rich history of Englewood began in the mid-1800s as the area quickly developed into a rail and commerce crossroads. Junction Grove changed its name to Englewood in 1868, and in 1889, it became part of the City of Chicago. With its cross streets at 63rd and Halsted, the four railroad stations, and the 63rd Street ‘L’ stop, Englewood has long been a transportation hub of the southwest side. This easy access helped to make Englewood one of the largest outlying business districts in the country for much of the first half of the 20th century (Roberts & Stamz, 2002).

Yet, as racial strife shook the 1950s and ’60s, white flight occurred from US communities while African Americans moved in. Subsequently, banks refused to lend money to people trying to start businesses or buy homes in African American neighborhoods, and major grocery stores and other companies refused to open branches. Englewood was no exception (Lydersen, 2011). Further, political redistricting has resulted in Englewood being divided into five districts, each of which is assigned to a different Illinois district. This has created more division and strife. Can you identify the political, economic and socio-cultural factors resulting from oppression and power?

JUST WHAT IS POWER?

Power is a concept that has come to possess numerous meanings for different individuals. Power is multifaceted and takes various forms: power over, power to, and power from (Kloos et al., 2012). Power over is the ability to compel or dominate others, control resources, and enforce commands. Power to is the ability of people to pursue personal and/or collective goals and to develop their own capacities. Power from is the ability to resist coercion and unwanted commands/demands.

Much of the conversations on power have been through the lens of empowerment (Riger, 1993; Rappaport, 1981; Rappaport, 1987). Rappaport (1981) proposed empowerment as a phenomenon of interest for the field, stating the need for a distinction between actual power (i.e., political empowerment) and perceived power (i.e., psychological empowerment).

Furthermore, we understand empowerment as an individualistic concept which needs to incorporate social power. These theorists have conceptualized empowerment as a manifestation of social power and propose three instruments of its implementation. First, it is having control over resources in such a way that they can be used to reward and punish various people . Second, it is the ability to control barriers to participation through defining what we talk about and how we talk about it. One example is expert power, which is based on the “perceived knowledge, skill, or experience of a person or group” (Kloos et al., 2012). Third, it is a force that shapes shared consciousness through myths, ideology, and control of information. To support these concepts, Serrano-García (1984), a community psychologist, discusses both the successes and failures of a community development intervention in her homeland of Puerto Rico in Case Study 9.3.

Case Study 9.3 Proyecto Esfuerzo (Project Effort)

Irma Serrano-Garcia (1984) wrote, “As a member of a group of people who believe in equality and freedom and in the capacity of human beings to achieve both, I write as a Puerto Rican and community psychologist. My work stems from a social change perspective. As a community psychologist with a commitment to the “disadvantaged” groups of society, I believe that my values should be clearly stated… the island was under Spanish rule from 1843 to 1898 making our traditions mainly hispanic and our language, Spanish. The country was turned over to the US as a war booty of the Spanish American War in 1898” (Serrano-Garcia, 1984, p. 174).

To this end, the country was under the rule of the US for some aspects such as citizenship and foreign trade, and some areas were ruled by Puerto Rico’s internal governmental structure. Economically 60% of the citizens earned an annual income of $2,500 or less, while 70% received food stamps (SNAP Benefits) or other public benefits. Unemployed rates soared at 22.7% of the population and 99% of the food was imported. Serrano-Garcia further shared, “Our reality is one of colonization and not self-determination, of hispanic not anglo-saxon traditions and of underdevelopment and not economic growth” (p. 174). This and other factors prompted the onset of community development efforts to foster change directed by the quest for empowerment. The intervention framework to address this challenge included both a community development and research model. Six key points acted as guidelines including familiarization with the community, needs and resources, linking reality, concrete activities and resident’s integration, transition, and end of project. Read more here . How do the six guidelines used in the framework intersect with each other?

LANGUAGE AS POWER

Systems of domination often work not only through physical force but through language. Cultural racism deems a group’s culture as inferior, including its language. A group’s social and political power typically coincides with the status of their language within the society (Belgrave & Allison, 2019). A byproduct of colonialism is the fact that millions of people around the world speak languages not indigenous to their own lands, but to former colonial powers (England, France, Spain, Portugal, etc.). Native cultures and languages were overthrown by the culture and language of the colonizers. Translation works both as a language tool and as an instrument of power, and this is used when languages are translated and when people are transformed, or translated, by changing their sense of their place in society.

Control over language and information is referred to as power/knowledge . Foucault asserts that power is inherently tied to control over and access to information and vice versa. Knowledge is always related to systems of power. James Baldwin (1979) similarly refers to language as a political instrument. The language a person uses communicates their status within that society. He proposed the language barrier that prevented Africans from communicating with one another limited their collective power. According to Baldwin, the development of Black English is a result of particular relationships of power: “A language comes into existence by means of brutal necessity, and the rules of the language are dictated by what the language must convey.”

COLONIALISM AS POWER

Perhaps one of the most expansive and dominating forms of power has been colonialism . During the 19th century, as much as 90% of the world was controlled and/or colonized by western (European and European-derived) nations. This suppression and domination were justified using the construct of race, false research theories that portrayed non-white populations as infantile, incompetent, primitive, savage, and needing western powers to civilize them and bring them into modernity. The rise of settler societies like the US and Canada are the results of centuries of violent conflict, cultural and spatial displacement, and social, economic, and political oppression. During the 20th century, people across Africa, Asia, and Latin America engaged in anti-colonial struggles for independence. Although formal imperial empires came to an end when these countries gained their independence, informal empires remained, as many nations continued to be dependent on former colonial powers. Consequently, political, economic, and military controls were largely maintained within these nations, as a result of adopting the power and oppression of the colonial powers.

OPPRESSION AND POWER: TWO SIDES OF THE SAME COIN

Power and oppression can be said to be mirror reflections of one another in a sense or are two sides of the same coin . Where you see power that causes harm, you will likely see oppression. Oppression emerges as a result of power, with its roots in global colonialism and conquests. For example, oppression as an action can deny certain groups jobs that pay living wages, can establish unequal education (e.g., through a lack of adequate capital per student for resources), can deny affordable housing, and the list goes on. You may be wondering why some groups live in poverty, reside in substandard housing, or simply do not measure up to the dominant society in some facet. We have some idea, but today we are still grappling with these questions and still conducting research studies to better understand.

As discussed at a seminar at the Leaven Center (2003), groups that do not have “power over” are those society classifies or labels as disenfranchised ; they are exploited and victimized in a variety of ways by agents of oppression and/or systems and institutions. They are subjected to restrictions and seen as expendable and replaceable—particularly by agents of oppression. This philosophy, in turn, minimizes the roles certain populations play in society. Sadly, agents of oppression often deny that this injustice occurs and blames oppressive conditions on the behaviors and actions of the oppressed group. Oppression subsequently becomes a system and patterns are adopted and perpetuated. Thai and Lien (2019) in Chapter 6 discuss diversity and highlight the impact of “white privilege” as a major contributor to systems and patterns of oppression for non-privileged individuals and groups.

Additionally, socialization patterns help maintain systems of oppression. Members of society learn through formal and informal educational environments that advance the ideologies of the dominant group, and how they should act and what their role and place are in society. Power is thus exercised in this instance but now is both psychologically and physically harmful. This process of constructing knowledge is helpful to those who seek to control and oppress, through power, because physical coercion may not last, but psychological ramifications can be perpetual, particularly without intervention.

As shared, knowledge is sustained through social processes, and what we come to know and believe is socially constructed, so it becomes ever more important to discuss dominant narratives of our society and the meaning it lends to our culture. It is our role as community psychologists to be a witness, to advocate, and to raise the voice a nd consciousness of those who lack power and /or the capacity to do so themselves. It is also our role to raise the consciousness of those who oppress and disempower. In the next section, we shall take a look at roles community psychologists can play in consciousness raising and deconstructing power and oppression .

ACTION STRATEGIES: DISMANTLING OPPRESSION AND POWER

As mentioned in Chapter 1 (Jason et al., 2019), community psychologists endorse a social justice and critical psychology perspective, where the position is to challenge and address oppressive systems through a number of action strategies including approaches that fall under a dismantling framework. To this end, we now discuss two interconnected, yet distinct community approaches that focus on what is termed the deconstruction and reclaiming of power . Deconstruction has its roots in Jacques Derrida’s work in critical analysis of theoretical and literary language. We speak about reclaiming as simply recovering or getting back. A discussion of liberation, followed by decolonization and reclaiming power through Black Feminist theory, concludes this section, as it demonstrates how power is de-centered and reclaimed for the power and liberation of communities.

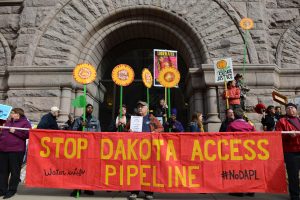

Community psychologists engage topics associated with the dismantling of oppression and power. One of these concepts is liberation. Liberation is defined as the social, cultural, economic, and political freedom and emancipation to have agency, control, and power over one’s life. To live life freely and unaffected or harmed by conditions of oppression is to experience liberation (Watkins, 2002). Although there are varied ways of experiencing liberation – from the individual to the community to the systemic – each one is interconnected with the other. An individual, or psychological sense of liberation, lies in the ability for the person to feel unconstrained by stereotypes and prejudiced ideas that manifest as acts of discrimination. When individuals are constantly feeling that their bodies are being perceived and categorized in biased ways because of their race, ethnicity, gender, sexuality, age, and other visible characteristics, their capacity to act with free will is constrained. For example, students of color at predominantly white institutions of higher education often experience higher levels of stress and anxiety because they experience more micro-aggressions (Hope et al., 2018). Students of color are therefore marked by these experiences in ways that are detrimental to their well-being and academic success. Liberation for these students is limited by the culture of racism and colorblindness inherent in the university. At a collective or community level, liberation is possible when the group is able to gain power and control over the knowledge, systems, and institutions that surround their lives. As Brazilian popular educator, Paulo Freire , suggests, liberation is a social act, a process of becoming free from ideologies that limit our freedom and the institutions or structures that constrain people’s collective determination. Liberation must be understood as having a critical consciousness of the circumstances and conditions of oppression that challenge and limit opportunities for freedom. Liberation is also a practice of working to create change. As Martín-Baró proposes, liberation is the dismantling of oppression and power, and striving to create social change that recognizes the humanity and dignity of all people. As an example of this work, we have included in Case Study 9.4 an excerpt of a letter adopted by the Society for Community Research and Action (SCRA) in opposition to the Dakota Access Pipeline.

Case Study 9.4 The Dakota Access Pipeline

In July 2016, the Army Corps of Engineers approved the plans for the Dallas-based Energy Transfer Partners to construct the Dakota Access Pipeline, a 1,172 mile underground crude oil transportation system stretching from North Dakota to Illinois. It is estimated that the pipeline will pump just under half a million barrels of fracked crude oil per day across the Missouri River, the Mississippi River, and other sources of drinking water, which will impact surrounding communities. Although many will potentially be affected by the proposed pipeline, the Lakota Sioux and the Standing Rock Sioux Indian Reservation spanning North and South Dakota are among those most directly affected by the pipeline and have voiced strong opposition to its continued construction. As psychologists committed to racial, ethnic, and cultural justice we stand in opposition to the continued construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline so long as that pipeline infringes on the environmental health and sacred spaces of indigenous communities…Read more of the letter here . What are examples of dismantling and liberation?

DECOLONIALITY

Although often associated with freedom, decoloniality is not the same nor should it be equated with liberation. Decoloniality is characterized by a process of undoing, disrupting, and de-linking knowledge rooted in Eurocentric thinking that ignores or devalues the local knowledge, experiences, and expertise of non-western peoples or dominant social groups (Maldonado-Torres, 2011). Furthermore, decoloniality challenges coloniality and colonialism – the former defined as the power and control over people and knowledge, and the latter being a process through which power and control are acquired often through violence (Mignolo, 2009). Decoloniality, therefore, contests the assumptions of systems, or the organization of peoples and worlds, into categories. For example, the “ othering ” of Indigenous communities by forcing them onto reservation lands and then subsequently occupying and exploiting these lands and natural resources, as in the Dakota Access Pipeline examples, is a form of coloniality. This “othering” perpetuates the oppression and dehumanization of Indigenous communities across generations (Gone, 2016). Re-thinking and deconstructing Eurocentric/western ideologies and practices that uphold coloniality as the power over people, lands, and knowledge is thus the main point of decolonization. A decolonial standpoint in Community Psychology honors and respects the humanity of all communities, especially those that have been institutionally marginalized, and sees values in local knowledge, culture, and place (Moane, 2003). An example of a decolonial community-based participatory action research project is the collaborative led by Dr. Jesica Siham Ferńandez and Dr. Laura Nichols, involving Mexican immigrant mothers in a community undergoing gentrification in the Silicon Valley (California, US). It centers on the voices, culture, and lived experiences of Mexican and Latinx communities (check out a newspaper report covering the making of the mural, and a short news media coverage showcasing the madres speaking about their process).

BLACK FEMINIST THOUGHT

This section discusses intersectionality as a form of decolonialism that is crucial to a well-rounded understanding of how our multiple identities play into the world around us. Intersectionality, rooted in Black feminist thought, emerged at the turn of the 21st century. Black feminist theory, informed by the work of Collins (1990/2000), Lorde (1984), hooks (1994), the Combahee River Collective , and other Black feminist scholars such as Sojourner Truth and other writers and activists, surfaced as a radical movement. Intersectionality was developed by Kimberlé W. Crenshaw and this short video link should help with understanding. The concept primarily illustrates the intersectional experiences of Black women, whose concerns were neither fully addressed within the Civil Rights Movement, nor the (white) feminist movement. Intersectionality posits that race and gender categories, along with other dimensions of identity and positionality, such as sexuality, age, class and able-bodiness, are clear and have social, legal, political, and economic implications. Within Community Psychology, intersectionality provides a theoretical lens for re-conceptualizing race, along with other categories of difference and positions of power, beyond identity politics. Rather than focusing on the politics of difference, intersectionality describes the interlocking patterns of oppression and marginality that structure people’s lives, opportunities, and enfranchisement. Intersectionality provides a theoretical framework from which we can examine and deconstruct the structures of race and gender oppression (Collins, 1990/2000). Furthermore, intersectionality also offers implications for working toward a practice of solidarity among those interested in advancing social justice.

SYSTEMS PERSPECTIVE