- Online Academy

- In-Person Training

- Problem Solving Facilitation

- Bespoke In-house Training

- Bespoke In-house Webinar

- Protect & Extend IP your Territory

- New Product or Service Development

- Knowledge Sharing

- Innovation Tools & Culture

- Rapid Response Support

What is TRIZ?

- Structured Innovation

Case Studies

- TRIZ & Other Toolkits

- Published Books

- Innovation Bank

- Effects Database

- In the Press

TRIZ is a systematic approach for understanding and solving any problem, boosting brain power and creativity, and ensuring innovation.

We regularly run live webinars to provide an overview of TRIZ processes and tools, register for free to find out more?

Watch with German subtitles / Mit Deutschen Untertiteln >>

The Origins of TRIZ

Beginning in 1946 and still evolving, TRIZ was developed by the Soviet inventor Genrich Altshuller and his colleagues. TRIZ in Russian = Teoriya Resheniya Izobretatelskikh Zadatch or in English, The Theory of Inventive Problem Solving. Years of Russian research into patents uncovered that there are only 100 known solutions to fundamental problems and made them universally available in three TRIZ solution lists and the Effects Database .

Through enabling clear thinking and the generation of innovative ideas, TRIZ helps you to find an ideal solution without the need for compromise. However it is not a Theory - it is a big toolkit consisting of many simple tools - most are easy to learn and immediately apply to problems. This amazing capability helps us tackle any problem or challenge even when we face difficult, intractable or apparently impossible situations.

TRIZ helps us keep detail in its place, to see the big picture and avoid getting tripped up with irrelevance, waylaid by trivial issues or seduced by premature solutions. It works alongside and supports other toolkits, and is particularly powerful for getting teams to work together to understand problems effectively, collectively generate ideas and innovate.

Developed by Oxford Creativity, Oxford TRIZ™ is simpler than standard or classic TRIZ. Its tools and processes are faster to learn and easier to apply. Oxford TRIZ is true to classic TRIZ (neither adding nor removing anything) but it delivers:

More powerful results

Faster and easier ways to learn and apply triz, step-by-step processes for applying triz toolkits, 'at a glance' understanding, supported by our hallmark commissioned cartoons (from clive goddard), philosophy of making every session effective, efficient and fun, gap-filling where other toolkits fall short.

TRIZ enthusiasts who have failed to use TRIZ effectively or to embed TRIZ into their organisations hail Oxford TRIZ as revelatory.

Very impressed with how Oxford Creativity has been able to create a methodology for applying TRIZ that can be widely used.

"I have learnt new and powerful ways of looking at problems differently to come up with new and viable solutions. It is a toolset that I think all engineers would find useful. "

Michelle Chartered (Aeronautical) Engineer

Join one of our free webinars to learn more about TRIZ, its tools and how they can help you create innovative solutions to your problems.

Alternatively, sign up for Oxford TRIZ Live - Fundamental Problem Solving, our new online course that will give you a solid foundation in TRIZ concepts, tools and techniques and get you using them from day one.

History of TRIZ

How did triz start who was the founder altshuller.

It seems unfair that the work of Altshuller, perhaps one of the greatest engineers of the twentieth century remains quite obscure; especially as the his powerful findings enhances and transforms the work of managerial and technical teams in most countries of the world. He was a remarkable and charismatic man who innovated innovation and inspired many, as an inventor, teacher, and science-fiction author (Altov). The stories about Genrich Saulovich Altshuller (1926-1998) founder of TRIZ, derive mostly from those who worked with him, a community of Jewish intellectuals from Ukraine, Russia, and other countries once part of the Soviet Union. Many of these left Russia when they could, in the early 1990’s, taking TRIZ with them, to reach business and technical communities all over the world. Although TRIZ is a Russian acronym*, in today’s troubled world it is worth emphasising that TRIZ is much more Zelensky than Putin – as it was developed in a Siberian Gulag by those who stood up to Stalin.

Altshuller's groundbreaking work in the field of creative problem-solving derives from analysing the patent database and identifying and sharing the patterns of success in the world’s published knowledge. This is unlike most other creative techniques which cluster round brain prompts to improve brainstorming. TRIZ contains all these too, but they seem less significant than the power of the unique solution techniques uncovered by the TRIZ community in the last century.

Altshuller’s life

Genrich Saulovich Altshuller was bought up in Baku, Azerbaijan, but was born in Tashkent, Uzbekistan on October 15, 1926, at those times both countries were a part of the Soviet Union. Just too young to serve in World War II, Altshuller was patenting his inventions from 1940 when he was just 14. He trained as a diver and electrician and later at the Azerbaijan Oil and Chemistry Institute in Baku. Altshuller joined the Soviet Navy as a mechanical engineer in his early twenties and worked in the Baku patent department, interacting with the Caspian Sea flotilla of the Soviet Navy where, as in all wars, creativity and invention flourished; this had a profound impact on his thinking and future endeavours. It was here that he began to formalize his Theory of Inventive Problem Solving, together with his colleague Raphael Shapiro. TRIZ was born out of the pair's aspiration to create a systematic approach to problem-solving that could replace the hit-or-miss strategies often used by inventors.

Altshuller’s genius observation of the frequent occurrence of identical solutions in different industries

Altshuller ’bottled’ the inventive process. He identified how frequently inventors duplicate each other’s work as they unknowingly reinvent the wheel. They fail to recognise that their efforts are repeating work already achieved (and documented), because their results are published in their own specialist technical language. Altshuller could see how science and engineering (by this time segmented and specialised) had become a ‘Tower of Babel’** because each discipline had its own different technical jargon. It was as if there were now many tribes in technology, with their own tribal language, which they used to write their papers and patents; (Chemists spoke chemistry and physicist spoke physics etc.). Altshuller showed that by stripping out details (which removed most technical jargon) both the problems being solved and their answers were revealed. This research showed that there are only about 100 fundamental ways to solve any problem. Altshuller and his teams gave these ‘ hundred answers to anything’ in three overlapping lists which show us how to:-

- Resolve contradictions (40 Principles)

- Invent future Products (8 Trends)

- Deal with Harms, boost insufficiencies and measure or detect (76 Standard Solutions)

These concept solutions underly all inventive problem-solving and they help us solve particular problems through using the TRIZ Contradiction Matrix and Separation Principles and TRIZ Function Mapping. Also there is the TRIZ Effects Database which answers ‘how to’ questions – so if we wanted to know how to ‘change viscosity’ it would show us all published ways and give an explanation of each. (see https://www.triz.co.uk/triz-effects-database )

Development of TRIZ:

Altshuller and his TRIZ community created their database of technical problems and solutions from various industries by undertaking an exhaustive study of patents, scientific literature, and innovation history. TRIZ ‘uncovered’ all the ways humankind knows to tackle tough challenges and was a vast collaboration of many (including Rafael Shapiro) to formalise the TRIZ methodology by identifying patterns and principles common to all successful inventive solutions. TRIZ aimed to stop needless time-wasting duplication by providing a systematic approach to enable anyone to overcome problems and recognise and resolve contradictions, deal with harms and barriers in their work.

Once built the TRIZ foundations were their gift to the world distilling a vast store of human wisdom into the 3 simple lists of TRIZ concepts. Some erroneously describe TRIZ as complicated because it derives from more rigour and research than all other toolkits put together, but its power is its logical steps and simplicity. It is as easy as learning chess - each tool is can be quickly understood to see how it can be ‘played’ in specific ways – the challenge is knowing how to combine the tools together. There are as many solutions to problems as outcomes in chess – mastering both takes quick learning (and talent?) and then as much practice as possible.

Soviet Suppression:

Despite its immense potential, TRIZ was not initially well-received by the Soviet government, Altshuller's claim that scientists and engineers duplicated each other’s work was unacceptable "non-conformist" thinking, and TRIZ was initially labelled as "bourgeois pseudoscience." Altshuller, along with several of his colleagues, often faced oppression, and their work was kept underground in several different periods. By the late 1940s Altshuller was arrested on political charges and spent time in the infamous Vorkuta Gulag in the Russian Arctic before being released in 1954 (after Stalin’s death). On his arrest the KGB ‘interviewed’ his widowed mother, killing her by pushing her from the balcony of her flat. Despite these setbacks, his determination to pursue his theories did not wane even in the Gulag which he described as his university of life.

Upon his release, Altshuller returned to his work with renewed vigour, working through thousands of patents, extracting their patterns of problem-solving into the TRIZ lists, and also uncovering the contradiction toolkit and the other creative concepts essential to tackling problems such as the Ideal and Ideality, Thinking in Time and Scale (9 boxes) plus many other tools for idea generation.

Recognition and success

Altshuller's determination prevailed, and in the 1960s, he managed to publish some of his TRIZ-related works. He also conducted lectures and workshops to disseminate the principles of TRIZ across the Soviet Union and beyond. His community expanded to include school children from his fortnightly TRIZ comics and his most famous book ‘And Suddenly the Inventor Appeared’. His ideas gained traction among engineers, leading to the formation of TRIZ associations and study groups. After 1990 the political reforms which swept the Soviet Union and its territories enabled TRIZ to surge in popularity and recognition. Altshuller's efforts were finally acknowledged, and he received numerous awards and honours for his groundbreaking work.

TRIZ Today?

Genrich Altshuller's legacy lives on through TRIZ, which continues to influence problem-solving and innovation processes worldwide. TRIZ has been integrated into various industries, including engineering, product development, and management, allowing practitioners to find inventive solutions efficiently. It has proved an essential innovation toolkit in countries like South Korea, China and Japan where they have moved to the top of Patent league tables, pushing aside counties like the UK where there is no official or university take up (exceptions include the universities of Imperial and Bath). However one the world’s leading TRIZ consultancies is based in the UK and created the popular Oxford TRIZ TM. Russian TRIZ development seems to be detailed and complicated (the opposite of TRIZ simplicity)

Altshuller's Legacy

Altshuller’s income derived more from his writings than his TRIZ work because he made TRIZ free to the world and public domain. Altshuller published so many books, articles, and scientific papers, which inspire and clarify the thinking of generations of inventors, innovators, and problem-solvers. In his later years he developed Parkinson’s disease, and he worked on sharing all the habits of geniuses and his last book was called ‘How to be a genius or heretic’ and he died on September 24, 1998, in Petrozavodsk, Russia. Altshuller's work has influenced numerous fields, including engineering, business strategy, and software development. Despite TRIZ being less known than other toolkit , his impact on the world remains undeniable if still largely under-appreciated. The power of TRIZ for boosting genius brain power, inventive problem-solving and innovation could change the world for the better if only it was known and accepted everywhere.

Problems Oxford Creativity has solved for our customers

Oxford Creativity Ltd, Reg No. 03850535

Copyright 2024

Six Sigma Terms: What is TRIZ – The Theory of Inventive Problem Solving?

TRIZ, also known as the theory of inventive problem solving, is a technique that fosters invention for project teams who have become stuck while trying to solve a business challenge. It provides data on similar past projects that can help teams find a new path forward.

TRIZ (pronounced “trees”) started in Russia. It involves a technique for problem solving created by observing the commonalities in solutions discovered in the past. Created by Genrich Altshuller in the former Soviet Union, the Six Sigma technique recognizes that certain patterns emerge whenever inventions are made.

Features of the Technique

Altshuller found that almost every invention falls into one of 40 categories. Each is an area where invention and innovation took place. They include areas such as weight, length and area of moving and stationary objects, speed of the object, temperature illumination intensity, ease of operation and ease of repair.

In practical use, a project team stymied by a challenge can use TRIZ to analyze a matrix of similar challenges and their solutions.

When TRIZ Is Used

TRIZ operates on the idea that someone, somewhere, likely came up with a solution for the challenge you currently face or something similar. Another guiding principle is that contradictions should not be accepted, but rather resolved.

It also provides an answer for those concerned that Six Sigma stifles innovation . TRIZ encourages innovation. As pointed out in a paper on TRIZ conducted by researchers at the University of Belgrade and Metropolitan University in Serbia, not all solutions involving Six Sigma can be found in the process itself.

This “inhibits the ability to identify the control variables. In this case, a methodology that can solve the problem outside of the process boundaries, such as TRIZ, is necessary,” the researchers wrote.

Essentially, TRIZ offers a sophisticated, effective tool for clearing roadblocks.

The Benefits of TRIZ

TRIZ works best in situations where other Six Sigma tools have not accomplished the task. It provides another way to find solutions during the improve phase of the Six Sigma technique DMAIC (define, measure, analyze, improve, control) or the design phase of DMADV (define, measure, analyze, design, verify).

TRIZ allows project teams to globalize an issue and find examples of how people have solved similar challenges. It’s a bit like the old saying, “There’s no need to reinvent the wheel.” It’s possible that teams won’t have to develop a solution on their own, because it’s already been done. On the other hand, knowing the possible combination of the 40 categories that might apply to a specific issue can also spark new ideas.

How TRIZ Works and Examples

TRIZ translates problems from the specific to the generic. It then compares the current challenge with 40 different inventive solutions. This is because in his research, Altshuller found that:

- Problems and solutions repeat across industries and sciences.

- Patterns of technical evolution repeat across industries and sciences.

- Innovations used scientific effects outside the field where they were developed.

It also supplies potential solutions to apparently contradictory issues, such as wanting a more powerful engine that is lighter or wanting something to both operate faster and more accurately.

Most examples for TRIZ involve solving engineering issues, such as the invention of a new type of self-heating container as detailed by TRIZ Journal or creation of automation that can handle the simultaneous filing of 10 interlinked plastic cups with paint.

The Leading Source of Insights On Business Model Strategy & Tech Business Models

TRIZ: Theory of Inventive Problem Solving

- The TRIZ method is an organized, systematic, and creative problem-solving framework. It was developed in 1946 by Soviet inventor and author Genrich Altshuller who studied 200,000 patents to determine if there were patterns in innovation .

- Altshuller acknowledged that not every innovation was necessarily groundbreaking in scope or ambition. From the result of his research, he created five levels of innovation , with Level 1 innovations resulting from obvious or conventional solutions and Level 5 innovations resulting in new ideas that propelled technology forward.

- The TRIZ method has been altered multiple times since it was released and may appear complicated. However, problem-solving teams can take comfort from the fact that others have most likely prevailed against similar problems in the past.

The TRIZ method is an organized, systematic, and creative problem-solving framework. The TRIZ method was developed in 1946 by Soviet inventor and author Genrich Altshuller who studied thousands of inventions across many industries to determine if there were any patterns in innovation and the problems encountered.

Table of Contents

Understanding the TRIZ method

TRIZ is a Russian acronym for Teoriya Resheniya Izobretatelskikh Zadatch , translated as “The Theory of Inventive Problem Solving” in English.

For this reason, the TRIZ method is sometimes referred to as the TIPS method.

From careful research of over 200,000 patents, Altshuller and his team discovered that 95% of problems faced by engineers in a specific industry had already been solved.

Instead, the list was used to provide a systematic methodology that would allow teams to focus their creativity and encourage innovation .

In essence, the TRIZ method is based on the simple hypothesis that somebody, somewhere in the world has solved the same problem already.

Creativity, according to Altshuller, meant finding that prior solution and then adapting it to the problem at hand.

The five levels of the TRIZ method

While Altshuller analyzed hundreds of thousands of patents, he acknowledged that not every innovation was necessarily groundbreaking in scope or ambition.

After ten years of research between 1964 and 1974, he assigned each patent a value based on five levels of innovation :

Level 1 (32% of all patents)

These are innovations that utilize obvious or conventional solutions with well-established techniques.

Level 2 (45%)

The most common form where minor innovations are made that solve technical contradictions.

These are easily overcome when combining knowledge from different but related industries.

Level 3 (18%)

These are inventions that resolve a physical contradiction and require knowledge from non-related industries.

Elements of technical systems are either completely replaced or partly changed.

Level 4 (4%)

Or innovations where a new technical system is synthesized.

This means innovation is based on science and creative endeavor and not on technology.

Contradictions may be present in old, unrelated technical systems.

Level 5 (1%)

The rarest and most complex patents involved the discovery of new solutions and ideas that propel existing technology to new levels.

These are pioneering inventions that result in new systems and inspire subsequent innovation in the other four levels over time.

How the TRIZ method works

Since its release, the TRIZ method has been refined and altered by problem-solvers and scientists multiple times. But the problem-solving framework it espouses remains more or less the same:

Gather necessary information

Problem solvers must start by gathering the necessary information to solve the problem.

This includes reference materials, processes, materials, and tools.

Organize the information

Information related to the problem should also be collected, organized, and analyzed.

This may pertain to the practical experience of the problem, competitor solutions, and historical trial-and-error attempts.

Transform the information into a generic problem

Once the specific problem has been identified, the TRIZ method encourages the problem solvers to transform it into a generic problem.

Generic solutions can then be formulated and, with the tools at hand, the team can then create a specific solution that solves the specific problem.

Make sense of that

The last step in the TRIZ method appears to be rather complicated. But it is important for innovators to remember that most problems are not specific or unique to their particular circumstances.

Someone in the world at some point in time has faced the same issue and overcome it.

When to Use TRIZ:

TRIZ is a valuable problem-solving approach in a variety of scenarios:

1. Complex Technical Challenges:

TRIZ is particularly effective for solving complex engineering and technical problems, especially those involving conflicting requirements or constraints.

2. Innovation and Design:

When organizations seek to foster innovation in product design, TRIZ can help identify inventive solutions and drive creativity.

3. Product Development:

TRIZ can be applied at various stages of product development, from concept generation to troubleshooting and optimization.

4. Process Improvement:

It is useful for optimizing processes and operations, reducing inefficiencies, and eliminating bottlenecks.

5. Patent Analysis:

TRIZ can assist in analyzing patents and inventions to uncover the inventive principles and strategies used by others.

How to Use TRIZ:

Applying TRIZ effectively involves a systematic approach that leverages its principles and tools:

1. Define the Problem:

Clearly define the problem or challenge you are facing, including any contradictions or conflicts within the problem statement.

2. Identify Contradictions:

Identify the contradictions or conflicts inherent in the problem. These could be technical contradictions (e.g., increase strength vs. reduce weight) or physical contradictions (e.g., increase temperature vs. reduce temperature).

3. Apply Inventive Principles:

Consult the TRIZ inventive principles and tools to identify solutions that resolve the contradictions. These principles provide guidance on how to overcome specific challenges.

4. Ideate and Innovate:

Encourage creative thinking and brainstorming to generate potential solutions based on the inventive principles and insights gained from TRIZ analysis .

5. Evaluate and Select Solutions:

Evaluate the generated solutions for feasibility, effectiveness, and alignment with the ideal final result (IFR). Select the most promising solutions for further development.

6. Implement and Test:

Implement the chosen solutions and test them in practice. Monitor their effectiveness and make adjustments as needed.

Drawbacks and Limitations of TRIZ:

While TRIZ is a powerful methodology for inventive problem-solving, it is not without its drawbacks and limitations:

1. Complexity:

TRIZ can be complex and may require training and expertise to apply effectively, especially for novices.

2. Not a Panacea:

TRIZ may not be suitable for every problem. Some challenges may be better addressed through simpler problem-solving methods.

3. Cultural and Language Barriers:

TRIZ originated in Russia and has its own terminology, which can be a barrier for individuals from different cultural and linguistic backgrounds.

4. Resource-Intensive:

The extensive analysis and application of TRIZ principles can be resource-intensive, particularly in terms of time and expertise.

5. Not Suited for Non-Technical Problems:

TRIZ is primarily designed for technical and engineering problems and may not be well-suited for non-technical challenges.

What to Expect from Using TRIZ:

Using TRIZ can lead to several outcomes and benefits:

1. Creative Solutions:

TRIZ helps individuals and teams identify inventive solutions that may not be obvious through traditional problem-solving approaches.

2. Contradiction Resolution:

It offers a systematic way to address and resolve contradictions and conflicts within problems.

3. Innovation and Optimization:

TRIZ can drive innovation in product design, process improvement, and optimization efforts.

4. Structured Problem-Solving:

It provides a structured and systematic approach to problem-solving, making it easier to tackle complex challenges.

5. Knowledge Transfer:

TRIZ allows organizations to capture and transfer knowledge about inventive solutions across different projects and teams.

Complementary Frameworks to Enhance TRIZ:

TRIZ can be further enhanced when combined with complementary frameworks and techniques:

1. Lean Six Sigma:

Lean Six Sigma complements TRIZ by focusing on process improvement and waste reduction. Combining both approaches can lead to optimized processes with inventive solutions.

2. Design Thinking:

Design thinking complements TRIZ by emphasizing user-centered design, empathy, and iterative ideation. It encourages innovative solutions that meet user needs.

3. Brainstorming:

Brainstorming sessions can be used in conjunction with TRIZ to generate a wide range of ideas before applying TRIZ’s systematic analysis .

4. Root Cause Analysis:

Root cause analysis techniques help identify the underlying causes of problems, which can then be addressed using TRIZ’s inventive principles.

5. Simulation and Modeling:

Simulations and modeling tools can be used to test and validate TRIZ-based solutions before implementation.

Conclusion:

The Theory of Inventive Problem Solving (TRIZ) is a powerful and structured methodology for inventive problem-solving.

By leveraging the principles of TRIZ, individuals and teams can identify inventive solutions to complex technical challenges, foster innovation in product design, and optimize processes.

While TRIZ may have some limitations and complexities, its benefits in driving creativity, resolving contradictions, and providing a structured problem-solving approach make it a valuable tool for individuals and organizations seeking inventive solutions.

When combined with complementary frameworks and techniques, TRIZ becomes an even more potent force for innovation and creative problem-solving, allowing organizations to overcome technical challenges and achieve breakthroughs in their fields.

Case Studies

Product Design Improvement

Imagine a company that manufactures smartphones and wants to enhance the design of their devices to stand out in the market. They identify the problem as “Stagnant Smartphone Design.”

- Gather Necessary Information : The team collects data on existing smartphone designs, materials, user feedback, and market trends.

- Organize the Information : They analyze existing smartphone designs, including those of competitors, and categorize common design elements and user preferences.

- Transform into a Generic Problem : The generic problem becomes “How to create a smartphone design that appeals to a wide range of users and differentiates from competitors.”

- Apply Tools and Create a Solution : The team utilizes TRIZ tools to generate innovative design concepts. They explore principles like “Use of Contradictions” to balance features like aesthetics and functionality.

- Recognize Commonality : The team researches historical smartphone design breakthroughs and identifies elements that have successfully appealed to users in the past.

This process may lead to a novel smartphone design that incorporates innovative features, such as flexible displays, while addressing common user preferences.

Supply Chain Optimization

A logistics company faces challenges in optimizing its supply chain operations to reduce costs and improve efficiency. They define the problem as “Inefficient Supply Chain Operations.”

- Gather Necessary Information : Data on current supply chain processes, transportation methods, warehousing, and inventory management are gathered.

- Organize the Information : The team analyzes existing supply chain operations, identifies bottlenecks, and reviews industry best practices.

- Transform into a Generic Problem : The generic problem becomes “How to create a highly efficient and cost-effective supply chain system.”

- Apply Tools and Create a Solution : TRIZ tools are applied to generate innovative solutions. Principles like “Trimming” are used to eliminate redundant steps in the supply chain.

- Recognize Commonality : The team researches successful supply chain optimizations in other industries and adapts relevant strategies.

The result may be a streamlined supply chain system that reduces transportation costs, minimizes inventory waste, and enhances overall efficiency.

Energy-Efficient Building Design

An architectural firm aims to design environmentally friendly buildings with superior energy efficiency. They identify the problem as “Inefficient Building Energy Consumption.”

- Gather Necessary Information : Data on existing building designs, construction materials, HVAC systems, and renewable energy technologies are collected.

- Organize the Information : The team analyzes current building designs, identifies energy consumption patterns, and reviews sustainable building practices.

- Transform into a Generic Problem : The generic problem becomes “How to design buildings that maximize energy efficiency and minimize environmental impact.”

- Apply Tools and Create a Solution : TRIZ tools are used to generate innovative building design concepts. Principles like “Ideal Final Result” help in envisioning energy-neutral structures.

- Recognize Commonality : The team studies environmentally friendly building designs worldwide and integrates successful strategies into their projects.

The outcome may be groundbreaking building designs that incorporate passive heating and cooling, energy-efficient materials, and renewable energy sources to achieve net-zero energy consumption.

Medical Device Innovation

A medical device manufacturer wants to develop a groundbreaking medical device to revolutionize patient care. They identify the problem as “Limited Innovation in Medical Devices.”

- Gather Necessary Information : Data on current medical device technologies, patient needs, regulatory requirements, and clinical studies are gathered.

- Organize the Information : The team reviews existing medical devices, identifies gaps in patient care, and studies medical technology advancements.

- Transform into a Generic Problem : The generic problem becomes “How to create a transformative medical device that significantly improves patient outcomes.”

- Apply Tools and Create a Solution : TRIZ tools are applied to generate innovative medical device concepts. Principles like “Contradiction Resolution” help address challenges like miniaturization and enhanced functionality.

- Recognize Commonality : The team studies pioneering medical device innovations and incorporates successful design elements into their project.

Key takeaways

- TRIZ Method: The TRIZ method is a problem-solving framework developed by Genrich Altshuller in 1946. TRIZ stands for “Teoriya Resheniya Izobretatelskikh Zadatch,” which translates to “The Theory of Inventive Problem Solving.”

- Origin and Purpose: Altshuller studied thousands of patents to identify patterns in innovation and problem-solving across various industries. He aimed to create a systematic methodology for problem-solving that encourages creativity and innovation .

- Level 1: Obvious or conventional solutions using well-established techniques (32% of patents).

- Level 2: Minor innovations overcoming technical contradictions by combining knowledge from related industries (45%).

- Level 3: Inventions resolving physical contradictions using knowledge from non-related industries (18%).

- Level 4: Innovations synthesizing new technical systems based on science and creativity (4%).

- Level 5: Pioneering inventions that lead to new systems and inspire innovation in other levels (1%).

- Gather Necessary Information: Collect relevant information about the problem, processes, materials, and tools.

- Organize the Information: Analyze and organize information related to the problem, including practical experience, competitor solutions, and historical attempts.

- Transform into a Generic Problem: Transform the specific problem into a generic form to formulate generic solutions.

- Apply Tools and Create a Solution: Use available tools to create a specific solution that addresses the specific problem.

- Recognize Commonality: Recognize that most problems have been faced by others in the past and have likely been overcome.

- TRIZ is a systematic problem-solving framework developed by Genrich Altshuller.

- It categorizes innovation into five levels based on the nature of the solution.

- The TRIZ method involves gathering and organizing information, transforming the problem into a generic form, applying tools, and recognizing commonality with past solutions.

- The method encourages problem-solvers to leverage existing solutions and patterns to creatively address new challenges.

The 40 TRIZ Principles

Connected analysis frameworks.

Failure Mode And Effects Analysis

Agile Business Analysis

Business Valuation

Paired Comparison Analysis

Monte Carlo Analysis

Cost-Benefit Analysis

CATWOE Analysis

VTDF Framework

Pareto Analysis

Comparable Analysis

SWOT Analysis

PESTEL Analysis

Business Analysis

Financial Structure

Financial Modeling

Value Investing

Buffet Indicator

Financial Analysis

Post-Mortem Analysis

Retrospective Analysis

Root Cause Analysis

Blindspot Analysis

Break-even Analysis

Decision Analysis

DESTEP Analysis

STEEP Analysis

STEEPLE Analysis

Related Strategy Concepts: Go-To-Market Strategy , Marketing Strategy , Business Models , Tech Business Models , Jobs-To-Be Done , Design Thinking , Lean Startup Canvas , Value Chain , Value Proposition Canvas , Balanced Scorecard , Business Model Canvas , SWOT Analysis , Growth Hacking , Bundling , Unbundling , Bootstrapping , Venture Capital , Porter’s Five Forces , Porter’s Generic Strategies , Porter’s Five Forces , PESTEL Analysis , SWOT , Porter’s Diamond Model , Ansoff , Technology Adoption Curve , TOWS , SOAR , Balanced Scorecard , OKR , Agile Methodology , Value Proposition , VTDF

More Resources

About The Author

Gennaro Cuofano

Discover more from fourweekmba.

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Type your email…

Continue reading

- 70+ Business Models

- Airbnb Business Model

- Amazon Business Model

- Apple Business Model

- Google Business Model

- Facebook [Meta] Business Model

- Microsoft Business Model

- Netflix Business Model

- Uber Business Model

How it works

For Business

Join Mind Tools

Article • 10 min read

Creative Problem Solving

Finding innovative solutions to challenges.

By the Mind Tools Content Team

Imagine that you're vacuuming your house in a hurry because you've got friends coming over. Frustratingly, you're working hard but you're not getting very far. You kneel down, open up the vacuum cleaner, and pull out the bag. In a cloud of dust, you realize that it's full... again. Coughing, you empty it and wonder why vacuum cleaners with bags still exist!

James Dyson, inventor and founder of Dyson® vacuum cleaners, had exactly the same problem, and he used creative problem solving to find the answer. While many companies focused on developing a better vacuum cleaner filter, he realized that he had to think differently and find a more creative solution. So, he devised a revolutionary way to separate the dirt from the air, and invented the world's first bagless vacuum cleaner. [1]

Creative problem solving (CPS) is a way of solving problems or identifying opportunities when conventional thinking has failed. It encourages you to find fresh perspectives and come up with innovative solutions, so that you can formulate a plan to overcome obstacles and reach your goals.

In this article, we'll explore what CPS is, and we'll look at its key principles. We'll also provide a model that you can use to generate creative solutions.

About Creative Problem Solving

Alex Osborn, founder of the Creative Education Foundation, first developed creative problem solving in the 1940s, along with the term "brainstorming." And, together with Sid Parnes, he developed the Osborn-Parnes Creative Problem Solving Process. Despite its age, this model remains a valuable approach to problem solving. [2]

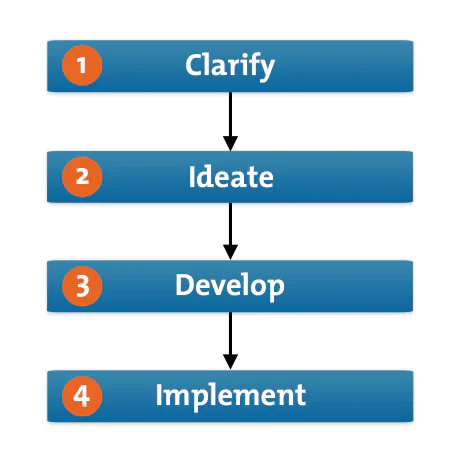

The early Osborn-Parnes model inspired a number of other tools. One of these is the 2011 CPS Learner's Model, also from the Creative Education Foundation, developed by Dr Gerard J. Puccio, Marie Mance, and co-workers. In this article, we'll use this modern four-step model to explore how you can use CPS to generate innovative, effective solutions.

Why Use Creative Problem Solving?

Dealing with obstacles and challenges is a regular part of working life, and overcoming them isn't always easy. To improve your products, services, communications, and interpersonal skills, and for you and your organization to excel, you need to encourage creative thinking and find innovative solutions that work.

CPS asks you to separate your "divergent" and "convergent" thinking as a way to do this. Divergent thinking is the process of generating lots of potential solutions and possibilities, otherwise known as brainstorming. And convergent thinking involves evaluating those options and choosing the most promising one. Often, we use a combination of the two to develop new ideas or solutions. However, using them simultaneously can result in unbalanced or biased decisions, and can stifle idea generation.

For more on divergent and convergent thinking, and for a useful diagram, see the book "Facilitator's Guide to Participatory Decision-Making." [3]

Core Principles of Creative Problem Solving

CPS has four core principles. Let's explore each one in more detail:

- Divergent and convergent thinking must be balanced. The key to creativity is learning how to identify and balance divergent and convergent thinking (done separately), and knowing when to practice each one.

- Ask problems as questions. When you rephrase problems and challenges as open-ended questions with multiple possibilities, it's easier to come up with solutions. Asking these types of questions generates lots of rich information, while asking closed questions tends to elicit short answers, such as confirmations or disagreements. Problem statements tend to generate limited responses, or none at all.

- Defer or suspend judgment. As Alex Osborn learned from his work on brainstorming, judging solutions early on tends to shut down idea generation. Instead, there's an appropriate and necessary time to judge ideas during the convergence stage.

- Focus on "Yes, and," rather than "No, but." Language matters when you're generating information and ideas. "Yes, and" encourages people to expand their thoughts, which is necessary during certain stages of CPS. Using the word "but" – preceded by "yes" or "no" – ends conversation, and often negates what's come before it.

How to Use the Tool

Let's explore how you can use each of the four steps of the CPS Learner's Model (shown in figure 1, below) to generate innovative ideas and solutions.

Figure 1 – CPS Learner's Model

Explore the Vision

Identify your goal, desire or challenge. This is a crucial first step because it's easy to assume, incorrectly, that you know what the problem is. However, you may have missed something or have failed to understand the issue fully, and defining your objective can provide clarity. Read our article, 5 Whys , for more on getting to the root of a problem quickly.

Gather Data

Once you've identified and understood the problem, you can collect information about it and develop a clear understanding of it. Make a note of details such as who and what is involved, all the relevant facts, and everyone's feelings and opinions.

Formulate Questions

When you've increased your awareness of the challenge or problem you've identified, ask questions that will generate solutions. Think about the obstacles you might face and the opportunities they could present.

Explore Ideas

Generate ideas that answer the challenge questions you identified in step 1. It can be tempting to consider solutions that you've tried before, as our minds tend to return to habitual thinking patterns that stop us from producing new ideas. However, this is a chance to use your creativity .

Brainstorming and Mind Maps are great ways to explore ideas during this divergent stage of CPS. And our articles, Encouraging Team Creativity , Problem Solving , Rolestorming , Hurson's Productive Thinking Model , and The Four-Step Innovation Process , can also help boost your creativity.

See our Brainstorming resources within our Creativity section for more on this.

Formulate Solutions

This is the convergent stage of CPS, where you begin to focus on evaluating all of your possible options and come up with solutions. Analyze whether potential solutions meet your needs and criteria, and decide whether you can implement them successfully. Next, consider how you can strengthen them and determine which ones are the best "fit." Our articles, Critical Thinking and ORAPAPA , are useful here.

4. Implement

Formulate a plan.

Once you've chosen the best solution, it's time to develop a plan of action. Start by identifying resources and actions that will allow you to implement your chosen solution. Next, communicate your plan and make sure that everyone involved understands and accepts it.

There have been many adaptations of CPS since its inception, because nobody owns the idea.

For example, Scott Isaksen and Donald Treffinger formed The Creative Problem Solving Group Inc . and the Center for Creative Learning , and their model has evolved over many versions. Blair Miller, Jonathan Vehar and Roger L. Firestien also created their own version, and Dr Gerard J. Puccio, Mary C. Murdock, and Marie Mance developed CPS: The Thinking Skills Model. [4] Tim Hurson created The Productive Thinking Model , and Paul Reali developed CPS: Competencies Model. [5]

Sid Parnes continued to adapt the CPS model by adding concepts such as imagery and visualization , and he founded the Creative Studies Project to teach CPS. For more information on the evolution and development of the CPS process, see Creative Problem Solving Version 6.1 by Donald J. Treffinger, Scott G. Isaksen, and K. Brian Dorval. [6]

Creative Problem Solving (CPS) Infographic

See our infographic on Creative Problem Solving .

Creative problem solving (CPS) is a way of using your creativity to develop new ideas and solutions to problems. The process is based on separating divergent and convergent thinking styles, so that you can focus your mind on creating at the first stage, and then evaluating at the second stage.

There have been many adaptations of the original Osborn-Parnes model, but they all involve a clear structure of identifying the problem, generating new ideas, evaluating the options, and then formulating a plan for successful implementation.

[1] Entrepreneur (2012). James Dyson on Using Failure to Drive Success [online]. Available here . [Accessed May 27, 2022.]

[2] Creative Education Foundation (2015). The CPS Process [online]. Available here . [Accessed May 26, 2022.]

[3] Kaner, S. et al. (2014). 'Facilitator′s Guide to Participatory Decision–Making,' San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

[4] Puccio, G., Mance, M., and Murdock, M. (2011). 'Creative Leadership: Skils That Drive Change' (2nd Ed.), Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

[5] OmniSkills (2013). Creative Problem Solving [online]. Available here . [Accessed May 26, 2022].

[6] Treffinger, G., Isaksen, S., and Dorval, B. (2010). Creative Problem Solving (CPS Version 6.1). Center for Creative Learning, Inc. & Creative Problem Solving Group, Inc. Available here .

You've accessed 1 of your 2 free resources.

Get unlimited access

Discover more content

4 logical fallacies.

Avoid Common Types of Faulty Reasoning

Everyday Cybersecurity

Keep Your Data Safe

Add comment

Comments (0)

Be the first to comment!

Gain essential management and leadership skills

Busy schedule? No problem. Learn anytime, anywhere.

Subscribe to unlimited access to meticulously researched, evidence-based resources.

Join today and save on an annual membership!

Sign-up to our newsletter

Subscribing to the Mind Tools newsletter will keep you up-to-date with our latest updates and newest resources.

Subscribe now

Business Skills

Personal Development

Leadership and Management

Member Extras

Most Popular

Latest Updates

Better Public Speaking

How to Build Confidence in Others

Mind Tools Store

About Mind Tools Content

Discover something new today

How to create psychological safety at work.

Speaking up without fear

How to Guides

Pain Points Podcast - Presentations Pt 1

How do you get better at presenting?

How Emotionally Intelligent Are You?

Boosting Your People Skills

Self-Assessment

What's Your Leadership Style?

Learn About the Strengths and Weaknesses of the Way You Like to Lead

Recommended for you

7 ways to combat anxiety.

Using simple techniques to de-stress

Business Operations and Process Management

Strategy Tools

Customer Service

Business Ethics and Values

Handling Information and Data

Project Management

Knowledge Management

Self-Development and Goal Setting

Time Management

Presentation Skills

Learning Skills

Career Skills

Communication Skills

Negotiation, Persuasion and Influence

Working With Others

Difficult Conversations

Creativity Tools

Self-Management

Work-Life Balance

Stress Management and Wellbeing

Coaching and Mentoring

Change Management

Team Management

Managing Conflict

Delegation and Empowerment

Performance Management

Leadership Skills

Developing Your Team

Talent Management

Problem Solving

Decision Making

Member Podcast

- Business Essentials

- Leadership & Management

- Credential of Leadership, Impact, and Management in Business (CLIMB)

- Entrepreneurship & Innovation

- Digital Transformation

- Finance & Accounting

- Business in Society

- For Organizations

- Support Portal

- Media Coverage

- Founding Donors

- Leadership Team

- Harvard Business School →

- HBS Online →

- Business Insights →

Business Insights

Harvard Business School Online's Business Insights Blog provides the career insights you need to achieve your goals and gain confidence in your business skills.

- Career Development

- Communication

- Decision-Making

- Earning Your MBA

- Negotiation

- News & Events

- Productivity

- Staff Spotlight

- Student Profiles

- Work-Life Balance

- AI Essentials for Business

- Alternative Investments

- Business Analytics

- Business Strategy

- Business and Climate Change

- Design Thinking and Innovation

- Digital Marketing Strategy

- Disruptive Strategy

- Economics for Managers

- Entrepreneurship Essentials

- Financial Accounting

- Global Business

- Launching Tech Ventures

- Leadership Principles

- Leadership, Ethics, and Corporate Accountability

- Leading Change and Organizational Renewal

- Leading with Finance

- Management Essentials

- Negotiation Mastery

- Organizational Leadership

- Power and Influence for Positive Impact

- Strategy Execution

- Sustainable Business Strategy

- Sustainable Investing

- Winning with Digital Platforms

What Is Creative Problem-Solving & Why Is It Important?

- 01 Feb 2022

One of the biggest hindrances to innovation is complacency—it can be more comfortable to do what you know than venture into the unknown. Business leaders can overcome this barrier by mobilizing creative team members and providing space to innovate.

There are several tools you can use to encourage creativity in the workplace. Creative problem-solving is one of them, which facilitates the development of innovative solutions to difficult problems.

Here’s an overview of creative problem-solving and why it’s important in business.

Access your free e-book today.

What Is Creative Problem-Solving?

Research is necessary when solving a problem. But there are situations where a problem’s specific cause is difficult to pinpoint. This can occur when there’s not enough time to narrow down the problem’s source or there are differing opinions about its root cause.

In such cases, you can use creative problem-solving , which allows you to explore potential solutions regardless of whether a problem has been defined.

Creative problem-solving is less structured than other innovation processes and encourages exploring open-ended solutions. It also focuses on developing new perspectives and fostering creativity in the workplace . Its benefits include:

- Finding creative solutions to complex problems : User research can insufficiently illustrate a situation’s complexity. While other innovation processes rely on this information, creative problem-solving can yield solutions without it.

- Adapting to change : Business is constantly changing, and business leaders need to adapt. Creative problem-solving helps overcome unforeseen challenges and find solutions to unconventional problems.

- Fueling innovation and growth : In addition to solutions, creative problem-solving can spark innovative ideas that drive company growth. These ideas can lead to new product lines, services, or a modified operations structure that improves efficiency.

Creative problem-solving is traditionally based on the following key principles :

1. Balance Divergent and Convergent Thinking

Creative problem-solving uses two primary tools to find solutions: divergence and convergence. Divergence generates ideas in response to a problem, while convergence narrows them down to a shortlist. It balances these two practices and turns ideas into concrete solutions.

2. Reframe Problems as Questions

By framing problems as questions, you shift from focusing on obstacles to solutions. This provides the freedom to brainstorm potential ideas.

3. Defer Judgment of Ideas

When brainstorming, it can be natural to reject or accept ideas right away. Yet, immediate judgments interfere with the idea generation process. Even ideas that seem implausible can turn into outstanding innovations upon further exploration and development.

4. Focus on "Yes, And" Instead of "No, But"

Using negative words like "no" discourages creative thinking. Instead, use positive language to build and maintain an environment that fosters the development of creative and innovative ideas.

Creative Problem-Solving and Design Thinking

Whereas creative problem-solving facilitates developing innovative ideas through a less structured workflow, design thinking takes a far more organized approach.

Design thinking is a human-centered, solutions-based process that fosters the ideation and development of solutions. In the online course Design Thinking and Innovation , Harvard Business School Dean Srikant Datar leverages a four-phase framework to explain design thinking.

The four stages are:

- Clarify: The clarification stage allows you to empathize with the user and identify problems. Observations and insights are informed by thorough research. Findings are then reframed as problem statements or questions.

- Ideate: Ideation is the process of coming up with innovative ideas. The divergence of ideas involved with creative problem-solving is a major focus.

- Develop: In the development stage, ideas evolve into experiments and tests. Ideas converge and are explored through prototyping and open critique.

- Implement: Implementation involves continuing to test and experiment to refine the solution and encourage its adoption.

Creative problem-solving primarily operates in the ideate phase of design thinking but can be applied to others. This is because design thinking is an iterative process that moves between the stages as ideas are generated and pursued. This is normal and encouraged, as innovation requires exploring multiple ideas.

Creative Problem-Solving Tools

While there are many useful tools in the creative problem-solving process, here are three you should know:

Creating a Problem Story

One way to innovate is by creating a story about a problem to understand how it affects users and what solutions best fit their needs. Here are the steps you need to take to use this tool properly.

1. Identify a UDP

Create a problem story to identify the undesired phenomena (UDP). For example, consider a company that produces printers that overheat. In this case, the UDP is "our printers overheat."

2. Move Forward in Time

To move forward in time, ask: “Why is this a problem?” For example, minor damage could be one result of the machines overheating. In more extreme cases, printers may catch fire. Don't be afraid to create multiple problem stories if you think of more than one UDP.

3. Move Backward in Time

To move backward in time, ask: “What caused this UDP?” If you can't identify the root problem, think about what typically causes the UDP to occur. For the overheating printers, overuse could be a cause.

Following the three-step framework above helps illustrate a clear problem story:

- The printer is overused.

- The printer overheats.

- The printer breaks down.

You can extend the problem story in either direction if you think of additional cause-and-effect relationships.

4. Break the Chains

By this point, you’ll have multiple UDP storylines. Take two that are similar and focus on breaking the chains connecting them. This can be accomplished through inversion or neutralization.

- Inversion: Inversion changes the relationship between two UDPs so the cause is the same but the effect is the opposite. For example, if the UDP is "the more X happens, the more likely Y is to happen," inversion changes the equation to "the more X happens, the less likely Y is to happen." Using the printer example, inversion would consider: "What if the more a printer is used, the less likely it’s going to overheat?" Innovation requires an open mind. Just because a solution initially seems unlikely doesn't mean it can't be pursued further or spark additional ideas.

- Neutralization: Neutralization completely eliminates the cause-and-effect relationship between X and Y. This changes the above equation to "the more or less X happens has no effect on Y." In the case of the printers, neutralization would rephrase the relationship to "the more or less a printer is used has no effect on whether it overheats."

Even if creating a problem story doesn't provide a solution, it can offer useful context to users’ problems and additional ideas to be explored. Given that divergence is one of the fundamental practices of creative problem-solving, it’s a good idea to incorporate it into each tool you use.

Brainstorming

Brainstorming is a tool that can be highly effective when guided by the iterative qualities of the design thinking process. It involves openly discussing and debating ideas and topics in a group setting. This facilitates idea generation and exploration as different team members consider the same concept from multiple perspectives.

Hosting brainstorming sessions can result in problems, such as groupthink or social loafing. To combat this, leverage a three-step brainstorming method involving divergence and convergence :

- Have each group member come up with as many ideas as possible and write them down to ensure the brainstorming session is productive.

- Continue the divergence of ideas by collectively sharing and exploring each idea as a group. The goal is to create a setting where new ideas are inspired by open discussion.

- Begin the convergence of ideas by narrowing them down to a few explorable options. There’s no "right number of ideas." Don't be afraid to consider exploring all of them, as long as you have the resources to do so.

Alternate Worlds

The alternate worlds tool is an empathetic approach to creative problem-solving. It encourages you to consider how someone in another world would approach your situation.

For example, if you’re concerned that the printers you produce overheat and catch fire, consider how a different industry would approach the problem. How would an automotive expert solve it? How would a firefighter?

Be creative as you consider and research alternate worlds. The purpose is not to nail down a solution right away but to continue the ideation process through diverging and exploring ideas.

Continue Developing Your Skills

Whether you’re an entrepreneur, marketer, or business leader, learning the ropes of design thinking can be an effective way to build your skills and foster creativity and innovation in any setting.

If you're ready to develop your design thinking and creative problem-solving skills, explore Design Thinking and Innovation , one of our online entrepreneurship and innovation courses. If you aren't sure which course is the right fit, download our free course flowchart to determine which best aligns with your goals.

About the Author

Review of TRIZ

- First Online: 02 April 2019

Cite this chapter

- Vladimir Petrov 2

1874 Accesses

Theory of inventive problem solving (TRIZ) is a science, which allows not only to identify and to solve creative problems in each field of knowledge, but also to develop creative (inventive) thinking and develop the features of a creative personality. It can often seem that the problem is based on some “ wild ” idea.

…TRIZ could be looked upon as a generalization of strong sides of creative experience of many generations of inventors: strong solutions are selected and analyzed, while weak and erroneous solutions are studied from critical viewpoint. Genrich Altshuller [G. Altshuller. Theory of Inventive Problem Solving. Review«TRIZ-88» (in Russian). URL: http://www.altshuller.ru/engineering16.asp ].

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Ra’anana, Israel

Vladimir Petrov

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Vladimir Petrov .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Petrov, V. (2019). Review of TRIZ. In: TRIZ. Theory of Inventive Problem Solving. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-04254-7_2

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-04254-7_2

Published : 02 April 2019

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-04253-0

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-04254-7

eBook Packages : Engineering Engineering (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Spencer Greenberg

- 14 min read

Problem-Solving Techniques That Work For All Types of Challenges

Essay by Spencer Greenberg, Clearer Thinking founder

A lot of people don’t realize that there are general purpose problem solving techniques that cut across domains. They can help you deal with thorny challenges in work, your personal life, startups, or even if you’re trying to prove a new theorem in math.

Below are the 26 general purpose problem solving techniques that I like best, along with a one-word name I picked for each, and hypothetical examples to illustrate what sort of strategy I’m referring to.

Consider opening up this list whenever you’re stuck solving a challenging problem. It’s likely that one or more of these techniques can help!

1. Clarifying

Try to define the problem you are facing as precisely as you can, maybe by writing down a detailed description of exactly what the problem is and what constraints exist for a solution, or by describing it in detail to another person. This may lead to you realizing the problem is not quite what you had thought, or that it has a more obvious solution than you thought.

Life Example

“I thought that I needed to find a new job, but when I thought really carefully about what I don’t like about my current job, I realized that I could likely fix those things by talking to my boss or even, potentially, just by thinking about them differently.”

Startup Example

“we thought we had a problem with users not wanting to sign up for the product, but when we carefully investigated what the problem really was, we discovered it was actually more of a problem of users wanting the product but then growing frustrated because of bad interface design.”

2. Subdividing

Break the problem down into smaller problems in such a way that if you solve each of the small problems, you will have solved the entire problem. Once a problem is subdivided it can also sometimes be parallelized (e.g., by involving different people to work on the different components).

“My goal is to get company Z to become a partner with my company, and that seems hard, so let me break that goal into the steps of (a) listing the ways that company Z would benefit from becoming a partner with us, (b) finding an employee at company Z who would be responsive to hearing about these benefits, and (c) tracking down someone who can introduce me to that employee.”

Math Example

“I want to prove that a certain property applies to all functions of a specific type, so I start by (a) showing that every function of that type can be written as a sum of a more specific type of function, then I show that (b) the property applies to each function of the more specific type, and finally I show that (c) if the property applies to each function in a set of functions then it applies to arbitrary sums of those functions as well.”

3. Simplifying

Think of the simplest variation of the problem that you expect you can solve that shares important features in common with your problem, and see if solving this simpler problem gives you ideas for how to solve the more difficult version.

“I don’t know how to hire a CTO, but I do know how to hire a software engineer because I’ve done it many times, and good CTOs will often themselves be good software engineers, so how can I tweak my software engineer hiring to make it appropriate for hiring a CTO?”

“I don’t know how to calculate this integral as it is, but if I remove one of the free parameters, I actually do know how to calculate it, and maybe doing that calculation will give me insight into the solution of the more complex integral.”

4. Crowd-sourcing

Use suggestions from multiple people to gain insight into how to solve the problem, for instance by posting on Facebook or Twitter requesting people’s help, or by posting to a Q&A site like Quora, or by sending emails to 10 people you know explaining the problem and requesting assistance.

Business Example

“Do you have experience outsourcing manufacturing to China? If so, I’d appreciate hearing your thoughts about how to approach choosing a vendor.”

Health Example

“I have trouble getting myself to stick to doing exercise daily. If you also used to have trouble getting yourself to exercise but don’t anymore, I’d love to know what worked to make it easier for you.”

5. Splintering

If the problem you are trying to solve has special cases that a solution to the general problem would also apply to, consider just one or two of these special cases as examples and solve the problem just for those cases first. Then see if a solution to one of those special cases helps you solve the problem in general.

“I want to figure out how to improve employee retention in general, let me examine how I could have improved retention in the case of the last three people that quit.”

“I want to figure out how to convince a large number of people to become customers, let me first figure out how to convince just Bill and John to become customers since they seem like the sort of customer I want to attract, and see what general lessons I learn from doing that.”

Read the books or textbooks that seem most related to the topic, and see whether they provide a solution to the problem, or teach you enough related information that you can now solve it yourself.

Economics Example

“Economists probably have already figured out reasonable ways to estimate demand elasticity, let’s see what an econometrics textbook says rather than trying to invent a technique from scratch.”

Mental Health Example

“I’ve been feeling depressed for a long time, maybe I should read some well-liked books about depression.”

7. Searching

Think of a similar problem that you think practitioners, bloggers or academics might have already solved and search online (e.g., via google, Q&A sites, or google scholar academic paper search) to see if anyone has done a write-up about how they solved it.

Advertising Example

“I’m having trouble figuring out the right advertising keywords to bid on for my specific product, I bet someone has a blog post describing how to approach choosing keywords for other related products.”

Machine Learning Example

“I can’t get this neural network to train properly in my specific case, I wonder if someone has written a tutorial about how to apply neural networks to related problems.”

8. Unconstraining

List all the constraints of the problem, then temporarily ignore one or more of the constraints that make the problem especially hard, and try to solve it without those constraints. If you can, then see if you can modify that unconstrained solution until it becomes a solution for the fully constrained problem.

“I need to hire someone who can do work at the intersection of machine learning and cryptography, let me drop the constraint of having cryptography experience and recruit machine learning people, then pick from among them a person that seems both generally capable and well positioned to learn the necessary cryptography.”

Computer Science Example

“I need to implement a certain algorithm, and it needs to be efficient, but that seems very difficult, so let me first figure out how to implement an inefficient version of the algorithm (i.e., drop the efficiency constraint), then at the end I will try to figure out how to optimize that algorithm for efficiency.”

9. Distracting

Fill your mind with everything you know about the problem, including facts, constraints, challenges, considerations, etc. and then stop thinking about the problem, and go and do a relaxing activity that requires little focus, such as walking, swimming, cooking, napping or taking a bath to see if new ideas or potential solutions pop into your mind unexpectedly as your subconscious continues to work on the problem without your attention.

“For three days, I’ve been trying to solve this problem at work, but the solution only came to me when I was strolling in the woods and not even thinking about it.”

Example from mathematician Henri Poincaré

“The incidents of the travel made me forget my mathematical work. Having reached Coutances, we entered an omnibus to go someplace or other. At the moment when I put my foot on the step, the idea came to me, without anything in my former thoughts seeming to have paved the way for it, that the transformations I had used to define the Fuchsian functions were identical with those of non-Euclidean geometry.”

10. Reexamining

Write down all the assumptions you’ve been making about the problem or about what a solution should I look like (yes – make an actual list). Then start challenging them one by one to see if they are actually needed or whether some may be unnecessary or mistaken.

Psychology Example

“We were assuming in our lab experiments that when people get angry they have some underlying reason behind it, but there may be some anger that is better modeled as a chemical fluctuation that is only loosely related to what happens in the lab, such as when people are quick to anger because they are hungry.”

“I need to construct a function that has this strange property, and so far I’ve assumed that the function must be smooth, but if it doesn’t actually need to be then perhaps I can construct just such a function out of simple linear pieces that are glued together.”

11. Reframing

Try to see the problem differently. For instance, by flipping the default, analyzing the inverse of the problem instead, thinking about how you would achieve the opposite of what you want, or shifting to an opposing perspective.

If we were building this company over again completely from scratch, what would we do differently in the design of our product, and can we pivot the product in that direction right now?”

“Should move to New York to take a job that pays $20,000 more per year? Well, if I already lived in New York, the decision to stay there rather than taking a $20,000 pay cut to move here would be an easy one. So maybe I’m overly focused on the current default of not being in New York and the short term unpleasantness of relocating.”

Marketing Example

“If I were one of our typical potential customers, what would I do to try to find a product like ours?”

12. Brainstorming

Set a timer for at least 5 minutes, and generate as many plausible solutions or ideas that you can without worrying about quality at all. Evaluate the ideas only at the end after the timer goes off.

“I’m going to set a timer for 5 minutes and come up with at least three new ways I could go about looking for a co-founder.”

“I’m going to set a timer for 20 minutes and come up with at least five possible explanations for why I’ve been feeling so anxious lately.”

13. Experting

Find an expert (or someone highly knowledgeable) in the topic area and ask their opinion about the best way to solve the problem.

“Why do you think most attempts at creating digital medical records failed, and what would someone have to do differently to have a reasonable chance at success?”

“What sort of optimization algorithm would be most efficient for minimizing the objective functions of this type?”

14. Eggheading

Ask the smartest person you know how they would solve the problem. Be sure to send an email in advance, describing the details so that this person has time to deeply consider the problem before you discuss it.

“Given the information I sent you about our competitors and the interviews we’ve done with potential customers, in which direction would you pivot our product if you were me (and why)?”

Research Example

“Given the information I sent you about our goals and the fact that our previous research attempts have gotten nowhere, how would you approach researching this topic to find the answer we need?”

15. Guessing

Start with a guess for what the solution could be, now check if it actually works and if not, start tweaking that guess to see if you can morph it into something that could work.

“I don’t know what price to use for the product we’re selling, so let me start with an initial guess and then begin trying to sell the thing, and tweak the price down if it seems to be a sticking point for customers, and tweak the price up if the customers don’t seem to pay much attention to the price.”

“My off the cuff intuition says that this differential equation might have a solution of the form x^a * e^(b x)for some a or b, let me plug it into the equation to see if indeed it satisfies the equation for any choice of a and b, and if not, let me see if I can tweak it to make something similar work.”

“I don’t know what the most effective diet for me would be, so I’ll just use my intuition to ban from my diet some foods that seem both unhealthy and addictive, and see if that helps.”

16. Comparing

Think of similar domains you already understand or similar problems you have already solved in the past, and see whether your knowledge of those domains or solutions to those similar problems may work as a complete or partial solution here.

“I don’t know how to find someone to fix things in my apartment, but I have found a good house cleaner before by asking a few friends who they use, so maybe I can simply use the same approach for finding a person to fix things.”

“This equation I’m trying to simplify reminds me of work I’m familiar with related to Kullback-Leibler divergence, I wonder if results from information theory could be applied in this case.”

17. Outsourcing

Consider whether you can hire someone to solve this problem, instead of figuring out how to solve it yourself.

“I don’t really understand how to get media attention for my company, so let me hire a public relations firm and let them handle the process.”

“I have no fashion sense, but I’d like to look better. Maybe I should hire someone fashionable who works in apparel to go shopping with me and help me choose what I should wear.”

18. Experimenting

Rapidly develop possible solutions and test them out (in sequence, or in parallel) by applying cheap and fast experiments. Discard those that don’t work, or iterate on them to improve them based on what you learn from the experiments.

“We don’t know if people will like a product like the one we have in mind, but we can put together a functioning prototype quickly, show five people that seem like they could be potential users, and iterate or create an entirely new design based on how they respond.”

“I don’t know if cutting out sugar will help improve my energy levels, but I can try it for two weeks and see if I notice any differences.”

19. Generalizing

Consider the more general case of the specific problem you are trying to solve, and then work on solving the general version instead. Paradoxically, it is sometimes easier to make progress on the general case rather than a specific one because it increases your focus on the structure of the problem rather than unimportant details.

“I want to figure out how to get this particular key employee more motivated to do good work, let me construct a model of what makes employees motivated to do good work in general, then I’ll apply it to this case.”

“I want to solve this specific differential equation, but it’s clearly a special case of a more general class of differential equations, let me study the general class and see what I can learn about them first and then apply what I learn to the specific case.”

20. Approximating

Consider whether a partial or approximate solution would be acceptable and, if so, aim for that instead of a full or exact solution.

“Our goal is to figure out which truck to send out for which delivery, which theoretically depends on many factors such as current location, traffic conditions, truck capacity, fuel efficiency, how many hours the driver has been on duty, the number of people manning each truck, the hourly rate we pay each driver, etc. etc. Maybe if we focus on just the three variables that we think are most important, we can find a good enough solution.”

“Finding a solution to this equation seems difficult, but if I approximate one of the terms linearly it becomes much easier, and maybe for the range of values we’re interested in, that’s close enough to an exact solution!”

21. Annihilating

Try to prove that the problem you are attempting to solve is actually impossible. If you succeed, you may save yourself a lot of time working on something impossible. Furthermore, in attempting to prove that the problem is impossible, you may gain insight into what makes it actually possible to solve, or if it turns out to truly be impossible, figure out how you could tweak the problem to make it solvable.

“I’m struggling to find a design for a theoretical voting system that has properties X, Y, and Z, let me see if I can instead prove that no such voting system with these three properties could possibly exist.”