- Open access

- Published: 05 March 2020

Quantitative ethnopharmacological documentation and molecular confirmation of medicinal plants used by the Manobo tribe of Agusan del Sur, Philippines

- Mark Lloyd G. Dapar 1 , 3 ,

- Grecebio Jonathan D. Alejandro 1 , 2 , 3 ,

- Ulrich Meve 3 &

- Sigrid Liede-Schumann 3

Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine volume 16 , Article number: 14 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

54k Accesses

54 Citations

14 Altmetric

Metrics details

The Philippines is renowned as one of the species-rich countries and culturally megadiverse in ethnicity around the globe. However, ethnopharmacological studies in the Philippines are still limited especially in the most numerous ethnic tribal populations in the southern part of the archipelago. This present study aims to document the traditional practices, medicinal plant use, and knowledge; to determine the relative importance, consensus, and the extent of all medicinal plants used; and to integrate molecular confirmation of uncertain species used by the Agusan Manobo in Mindanao, Philippines.

Quantitative ethnopharmacological data were obtained using semi-structured interviews, group discussions, field observations, and guided field walks with a total of 335 key informants comprising of tribal chieftains, traditional healers, community elders, and Manobo members of the community with their medicinal plant knowledge. The use-report (UR), use categories (UC), use value (UV), cultural importance value (CIV), and use diversity (UD) were quantified and correlated. Other indices using fidelity level (FL), informant consensus factors (ICF), and Jaccard’s similarity index (JI) were also calculated. The key informants’ medicinal plant use knowledge and practices were statistically analyzed using descriptive and inferential statistics.

This study enumerated the ethnopharmacological use of 122 medicinal plant species, distributed among 108 genera and belonging to 51 families classified in 16 use categories. Integrative molecular approach confirmed 24 species with confusing species identity using multiple universal markers (ITS, mat K, psb A- trn H, and trn L-F). There was strong agreement among the key informants regarding ethnopharmacological uses of plants, with ICF values ranging from 0.97 to 0.99, with the highest number of species (88) being used for the treatment of abnormal signs and symptoms (ASS). Seven species were reported with maximum fidelity level (100%) in seven use categories. The correlations of the five variables (UR, UC, UV, CIV, and UD) were significant ( r s ≥ 0.69, p < 0.001), some being stronger than others. The degree of similarity of the three studied localities had JI ranged from 0.38 to 0.42, indicating species likeness among the tribal communities. Statistically, the medicinal plant knowledge among respondents was significantly different ( p < 0.001) when grouped according to education, gender, social position, occupation, civil status, and age but not ( p = 0.379) when grouped according to location. This study recorded the first quantitative ethnopharmacological documentation coupled with molecular confirmation of medicinal plants in Mindanao, Philippines, of which one medicinal plant species has never been studied pharmacologically to date.

Documenting such traditional knowledge of medicinal plants and practices is highly essential for future management and conservation strategies of these plant genetic resources. This ethnopharmacological study will serve as a future reference not only for more systematic ethnopharmacological documentation but also for further pharmacological studies and drug discovery to improve public healthcare worldwide.

Introduction

The application of traditional medicine has gained renewed attention for the use of traditional, complementary, and alternative medicine (TCAM) in the developing and industrialized countries [ 1 , 2 ]. Conventional drugs these days may serve as effective medicines and therapeutics, but some rural communities still prefer natural remedies to treat selected health-related problems and conditions. Medicinal plants have long been used since the prehistoric period [ 3 ], but the exact time when the use of plant-based drugs has begun is still uncertain [ 4 ]. The WHO has accounted about 60% of the world’s population relying on traditional medicine and 80% of the population in developing countries depend almost entirely on traditional medical practices, in particular, herbal remedies, for their primary health care [ 5 ]. Estimates for the numbers of plant species used medicinally worldwide include 35,000–70,000 [ 6 ] with 7000 in South Asia [ 7 ] comprising ca. 6500 in Southeast Asia [ 8 , 9 ]. In the Philippines, more than 1500 medicinal plants used by traditional healers have been documented [ 10 ], and 120 plants have been scientifically validated for safety and efficacy [ 11 ]. Of all documented Philippine medicinal plants, the top list of medicinal plants used for TCAM has been enumerated by [ 12 ]. Most of these Philippine medicinal plants have been evaluated to scientifically validate folkloric claims like the recent studies of [ 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 ].

Because of the increasing demand for drug discovery and development of medicinal plants, the application of a quantitative approach in ethnobotany [ 21 ] and ethnopharmacology [ 22 ] has been rising continuously in the last few decades including multivariate analysis [ 23 ]. However, few studies of quantitative ethnobotanical research were conducted despite the rich plant biodiversity and cultural diversity in the Philippines. In particular, the Ivatan community in Batan Island of Luzon [ 24 ] and the Ati Negrito community in Guimaras Island of Visayas [ 21 ] have been documented, while Mindanao has remained less studied. Despite the richness of indigenous knowledge in the Philippines, few ethnobotanical studies have been conducted and published [ 25 ].

The Philippines is culturally megadiverse in diversity and ethnicity among indigenous peoples (IPs) embracing more than a hundred divergent ethnolinguistic groups [ 26 , 27 ] with known specific identity, language, socio-political systems, and practices [ 28 ]. Of these IPs, 61% are mainly inhabiting Mindanao, followed by Luzon with 33%, and some groups in Visayas (6%) [ 29 ]. One of these local people and minorities is the indigenous group of Manobo , inhabiting several areas only in Mindanao. They are acknowledged to be the largest Philippine ethnic group occupying a wide area of distribution than other indigenous communities like the Bagobo, Higaonon, and Atta [ 30 ]. The Manobo (“river people”) was the term named after the “Mansuba” which means river people [ 19 ], coined from the “man” (people) and the “suba” (river) [ 31 ]. Among the provinces dwelled by the Manobo , the province of Agusan del Sur is mostly inhabited by this ethnic group known as the Agusan Manobo . The origin of Agusan Manobo is still uncertain and immemorial; however, they are known to have Butuano, Malay, Indonesian, and Chinese origin occupying mountain ranges and hinterlands in the province of Agusan del Sur [ 32 ].

Manobo indigenous peoples are clustered accordingly, occupying areas with varying dialects and some aspects of culture due to geographical separation. Their historic lifestyle and everyday livelihood are rural agriculture and primarily depend on their rice harvest, root crops, and vegetables for consumption [ 33 ]. Some Agusan Manobo are widely dispersed in highland communities above mountain drainage systems, indicating a suitable area for their indigenous medicinal plants in the province [ 34 ]. Every city or municipality is governed with a tribal chieftain known as the “Datu” (male) or “Bae” (female) with his or her respective tribal healer “Babaylan” and the tribal leaders “Datu” of each barangay (village) leading their community. Their tribe has passed several challenges over the years but has still maintained to conserve and protect their ancestral domain to continually sustain their cultural traditions, practices, and values up to this present generation. This culture implies that there is rich medicinal plant knowledge in the traditional practices of Agusan Manobo , but their indigenous knowledge has not been systematically documented. Furthermore, there are no comprehensive ethnobotanical studies of medicinal plants used among the Manobo tribe in the Philippines to date.

Documenting the ethnomedicinal plant use and knowledge, and molecular confirmation of species using integrative molecular approach will help in understanding the true identity of medicinal plants in the treatment of health-related problems of the people of Agusan del Sur. This will also help the entire Agusan Manobo community to implement conservation priorities of their indigenous plant species. Furthermore, the provincial government of Agusan del Sur may enforce the proper utilization of their plant resources from IPs. Ideas and knowledge about ethnomedicinal use and practices of medicinal plants give credence to the traditional methods and preparation of herbal medicine by ethnic groups.

Despite the limited funds and qualified personnel in the region, it is very relevant to recognize the role of ethnopharmacology and species identification in the conservation of these plant genetic resources with medicinal properties. With the introduction of the application of molecular barcodes for species identification by [ 35 ], the problem of unauthenticated medicinal species can now be resolved [ 19 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 ].

Significantly, researchers have recently developed the application of ethnopharmacological study into a quantitative approach with measuring values and indices to quantify the relationship between plant species and humans [ 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 ].

This study, therefore, aims to (1) conduct quantitative ethnopharmacological documentation of traditional therapy, (2) evaluate the medicinal plant use and knowledge, and (3) utilize integrative molecular approach for species confirmation of medicinal plants used by the Manobo tribe in Agusan del Sur, Philippines.

Materials and methods

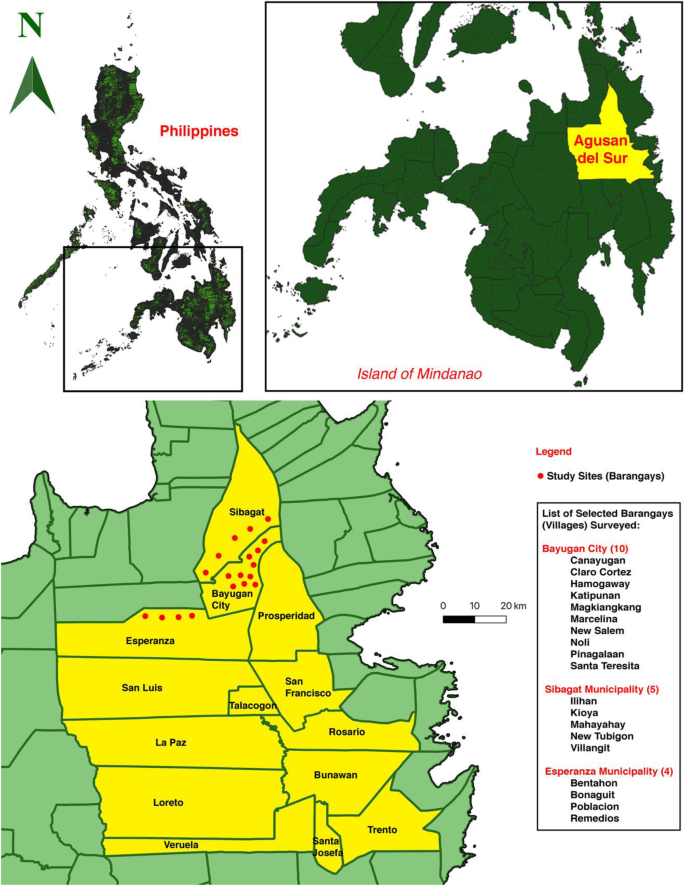

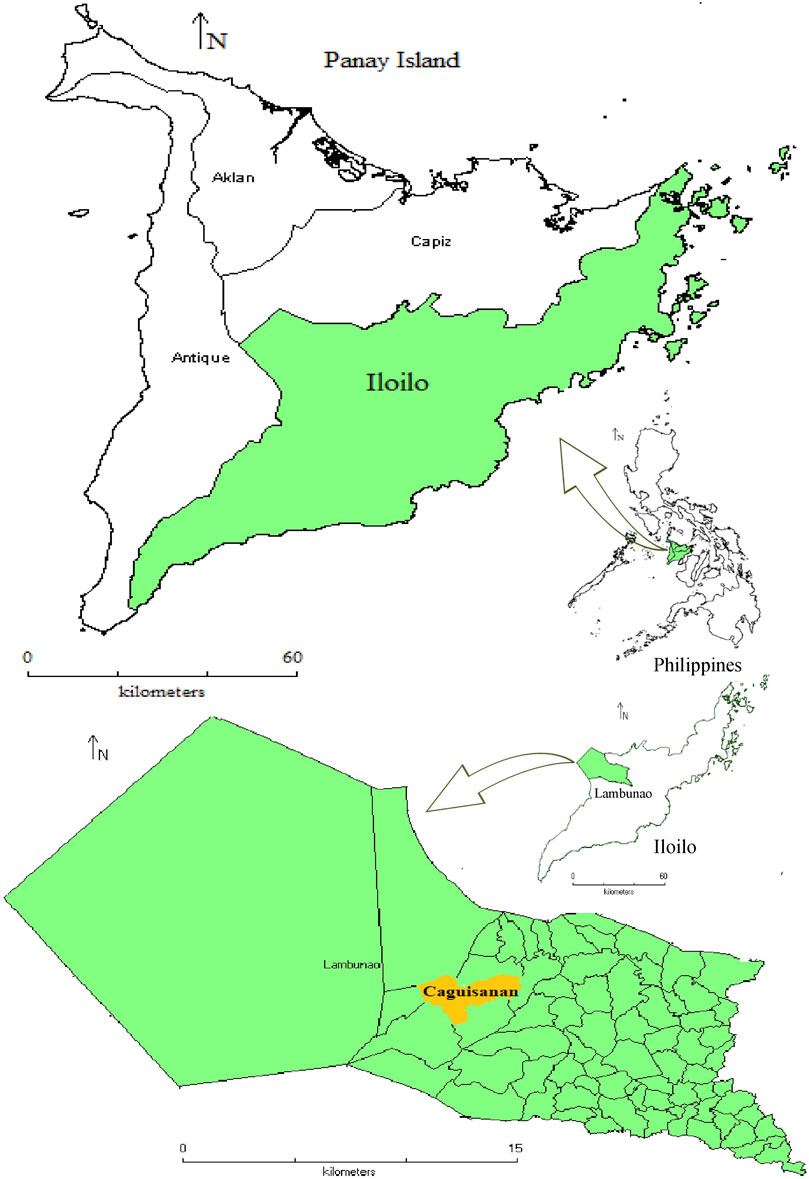

Fieldwork was conducted in the province of Agusan del Sur, Philippines (8° 30′ N 125° 50′ E), bordered from the north by Agusan del Norte, to the south by Davao del Norte, and from the west by Misamis Oriental and Bukidnon, to the east by Surigao del Sur. Agusan del Sur is bounded with mountain ranges from the eastern and western sides forming an elongated basin or valley in the center longitudinal section of the land. The province is subdivided into 13 municipalities (from the largest to smallest land area): La Paz, Esperanza, Loreto, San Luis, Talacogon, Sibagat, Prosperidad, Bunawan, Trento, Veruela, Rosario, San Francisco, and Sta. Josefa; and the only component city, the City of Bayugan (Fig. 1 ). Forestland comprises almost two thirds (74%) of the province of Agusan del Sur, while alienable and disposable (A&D) areas constitute around one-third (26%) of the total land area [ 49 ]. Every city or municipality has a respective community hospital and health center with limited doctors and rural health workers. Typically, local people only visit the hospitals or health centers for surgical and obstetric emergencies. Most residents rely on their medicinal plants for disease treatment and medication due to cost and poor access to healthcare services. This study purposively covered areas of selected city and municipalities (Bayugan, Esperanza, and Sibagat) for accessibility, availability, and security reasons to barangays (villages) with Certification of Ancestral Domain Title (CADT) as endorsed by the National Commission on Indigenous Peoples—CARAGA Administrative Region (NCIP-CARAGA).

Study sites (barangays) from the only city (Bayugan), and the two selected municipalities (Esperanza and Sibagat) in the province of Agusan del Sur

Sampling and interview

Fieldwork was undertaken from March 2018 to May 2019. It consisted of obtaining free prior informed consents, observing rituals, acquiring resolutions, certifications, and permits, conducting semi-structured interviews, focus group discussions, plant and field observations, and medicinal plant collections in selected barangays (villages) of Bayugan, Sibagat, and Esperanza (Fig. 1 ). This study was initiated in coordination with the local government unit (LGU), NCIP-LGU, and Provincial Environment and Natural Resources Office (PENRO) of Agusan del Sur. Consultation meetings and discussions were carried out together with the concerned parties (tribal leaders, tribal healers, and NCIP officers) to discuss research intent as purely academic and to acquire mutual agreement and respect to conduct this study. As approved, the research intent was certified through resolution and certification duly signed by the tribal council of elders following the by-laws of NCIP for the welfare and protection of indigenous peoples, and finally certified by NCIP-CARAGA.

Ethnopharmacological data were collected through semi-structured interviews with Manobo key informants through purposive and snowball sampling who were certified Agusan Manobo . A sampling of these key informants was coordinated with the provincial and local government administration together with the assistance of the tribal leaders and NCIP focal persons in every city or municipality to each of the barangays in selecting those who have knowledge of their medicinal plants and practices. The respective barangay tribal leaders assisted interviews among respondents with no appointments made prior to the visits. The semi-structured questionnaire used was modified and adapted from the Traditional Knowledge Digital Library (TKDL) template, as suggested by the Department of Health—Philippine Institute of Traditional and Alternative Health Care (DOH-PITAHC) (see Additional file 1 ). The Ethics Review Committee of the Graduate School, University of Santo Tomas (USTGS-ERC), approved the study and the questionnaire used with a valid translation to Manobo dialect ( Minanubu ) with the help of a community member and NCIP officer. It has series of questions about the common health problems encountered by the respondents; the actions undertaken to address such problems; the medicinal plants they used (local or vernacular name); the plant’s part(s) used, forms, modes, quantity or dosage, and frequency of administration; the source or transfer of knowledge; and the experienced adverse or side effects. Interviews were accompanied by nurses and allied workers as coordinated by the rural health center to verify reported diseases accurately by the informants.

Meetings and focus group discussions were also performed to review the accuracy of acquired data among the respondents with the help of guided questions among the tribal council of elders comprising the NCIP-recognized indigenous peoples mandatory representatives (IPMRs), the tribal chieftains, the tribal healers, and the respective tribal leaders of every barangay tribal communities together with the NCIP officer.

Plant collection and identification

The collection of plant specimens was conducted through guided field walks with the aid of the traditional healers, expert plant gatherers, and members within the tribal community. The plant habit, habitat, morphological characteristics, vernacular names, and some indigenous terms of their uses were documented. Leaf samples were placed in zip-locked bags containing silica gel for molecular analysis [ 50 ] in preparation for further molecular confirmation. Voucher specimens were deposited in the University of Santo Tomas Herbarium (USTH). Putative plant identification using vernacular names was compared to the reference of local names, Dictionary of Philippines Plant Names by [ 51 ]. Plant identification was assisted by Mr. Danilo Tandang, a botanist and researcher at the National Museum of the Philippines. Specimens unidentifiable by morphology were selected for molecular confirmation. All scientific names were verified and checked for spelling and synonyms and family classification using The Plant List [ 52 ], World Flora Online [ 53 ], The International Plant Names Index [ 54 ], and Tropicos [ 55 ]. The occurrence, distribution, and species identification were further verified using the updated Co’s Digital Flora of the Philippines [ 56 ].

DNA extraction, amplification, and sequencing

Collected plant specimens with insufficient material for identification due to lack of reproductive parts and unfamiliarity were subjected to molecular confirmation. The total genomic DNA was extracted from the silica gel-dried leaf tissues of samples following the protocols of DNeasy Plant Minikit (Qiagen, Germany). The ITS (nrDNA), mat K, trn H- psb A, and trn L-F (cpDNA) markers were used for this study. Primer information and PCR conditions used for amplification using Biometra T-personal cycler (Germany) can be found in Table 1 for future parameter reference. PCR amplicons were checked on a 1% TBE agarose to inspect for the presence and integrity of DNA. Amplified products were sent to Eurofins Genomics (Germany) for DNA sequencing reactions. Sequences were then assembled and edited using Codon Code Aligner v4.1.1. All sequences were then evaluated and compared using BLAST n search query available in the GenBank ( www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov ). The BLAST n method estimates the reliability of species identification as a sequence similarity search program to determine the sequence of interest [ 62 ] regardless of the age, plant part, or environmental factors of the sample [ 63 ].

Quantitative ethnopharmacological analysis

The use-report (UR) is counted as the number of times a medicinal plant is being used in a particular purpose in each of the categories [ 21 , 24 ]. Only one use-report was counted for every time a plant was cited as being used in a specific disease or purpose and even multiple disease or purpose under the same category [ 64 ]. Multiple use-reports were counted when at least two interviewees cited the same plant for the same disease or purpose. The use value (UV) developed by [ 45 ] is used to indicate species that are considered highly important by the given population using the following formula: UV = (ΣUi)/ N , where Ui is the number of UR or citations per species and N is the total number of informants [ 47 , 48 ]. High UV implies high plant use-reports relative to its importance to the community and vice versa. However, it does not determine whether the use of the plant is for single or multiple purposes [ 21 , 24 ]. The relative importance of the plants was also determined by calculating the cultural importance value (CIV) by using the formula: CIV = Σ[(ΣUR)/ N ], where UR is the number of use-reports in use category and N is the number of informants reporting the plant [ 48 ]. The use diversity (UD) of each medicinal plant used was determined using the Shannon index of uses as calculated with the R package vegan [ 65 ].

The ICF introduced by [ 66 ] was used to analyze the degree of informants’ agreement based on their medicinal plant knowledge in each of the categories [ 21 , 24 ]. This is computed using the formula: ICF = (Nur − Nt)/(Nur − 1), where Nur is the number of UR in each category, and Nt is the number of species used for a particular category by all informants. Fidelity level (FL) developed by [ 67 ] is calculated using the formula: FL (%) = (Ip/Iu) × 100, where Ip is the number of informants who independently suggested a given species for a particular disease, and Iu is the total number of informants who mentioned the plant for any use or purpose regardless of category. The maximum value (1.00) means a high degree of informant agreement showing the effectiveness of medicinal plants in each ailment category [ 68 ]. However, a minimum value (0.00) implies no information exchange among the informants [ 69 ]. Jaccard’s similarity index (JI) by [ 70 ] was calculated to evaluate the similarity of medicinal plant species among the three studied areas. The formula of JI is represented as follows: J = C /( A + B ), where A is the number of species found in habitat a, B is the number of species found in habitat b, and C is the number of common species found in habitats a and b. The number species present in either of the habitats is given by A + B (Jaccard).

Statistical tools

The plant URs were computed and analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics software v.23 [ 71 ]. Descriptive and non-parametric inferential statistics Mann-Whitney U and Kruskal-Wallis tests were employed to test for significant differences at 0.01 level of significance. These two statistical analyses measure and compare the medicinal plant use and knowledge of informants when grouped according to location, education, gender, social position, occupation, civil status, and age. The basic values and indices (UR, UC, UV, CIV, UD) were correlated using the Spearman correlation coefficient to compare variables that are not distributed normally.

Integrative molecular confirmation

Selected plant samples unidentifiable by morphology were subjected to an integrative molecular identification approach as previously recommended by [ 42 ] for accurate species identification of plant samples. Selected plant samples were compared with the available morphological characteristics, interview data on vernacular names and traditional knowledge, determining scientific names based on reference of local names using the Dictionary of Philippines Plant Names by [ 51 ], and utilizing multiple molecular markers, ITS (nrDNA), mat K, trn H- psb A, and trn L-F (cpDNA) for sequencing and BLAST matching. Two sequence similarity-based methods using BLAST [ 72 ] were applied for molecular confirmation. BLAST similarity-based identification was adapted from the study of [ 42 ] with a slight modification. This identification involved using the simple method taking the top hits and optimized approach. All successfully sequenced samples were sequentially queried using megablast [ 72 ] online at NCBI nucleotide BLAST against the nucleotide database. For the simple method, all top hits within a 5-point deviation down of the max score were considered. If the max score (− 5 points) showed only a single species, then a species level identification was assigned. On the other hand, if the max score (− 5 points) showed several species but similar genus, then a genus level identification was assigned. However, if the max score (− 5 points) showed multiple species in several genera of the same family, then a family level identification was assigned. In addition, within a 5-point deviation down of the max score, the highest max score and the highest percent identity were also determined. From the top 5 hits down of the max score, an optimized method using the formula, [max score (query cover/identity)], was calculated.

The integrative molecular confirmation combined the simple and optimized BLAST-based sequence matching results with reference of local names, and comparative morphology. As a result, all species identity and generic and familial affinity were further confirmed from the recorded occurrence and distribution of putative species in the study area based on the updated Co's Digital Flora of the Philippines [ 56 ].

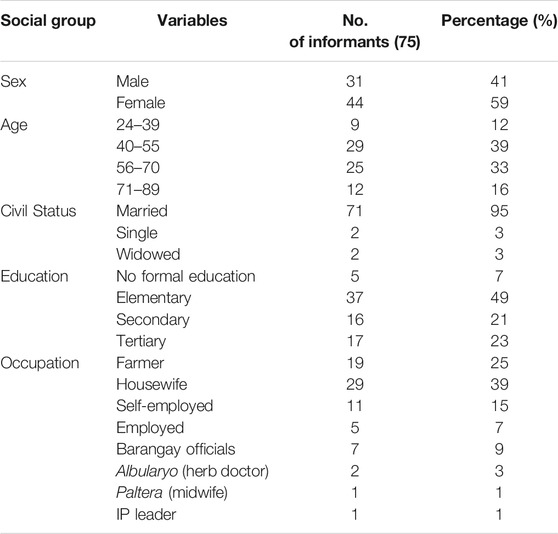

Demography of Informants

A total of 335 Agusan Manobo key informants (more than 10% of the total Manobo population of selected barangays) including traditional healers, leaders, council, and members were interviewed comprised with 106 female and 229 male individuals in an age range from 18–87 years old (median age of 42 years). We considered key informants those who are certified Agusan Manobo and knowledgeable with their medicinal plant uses and practices, may it be tribal officials, elders, and members of the community. Demographics by location, educational level, gender, social position, occupation, civil status, and age of participants are summarized in Table 2 .

Medicinal plant knowledge of Agusan Manobo

The majority of the respondents (90.45%) cited their acquisition of medicinal plant knowledge from their parents. They also mentioned other sources of knowledge like fellow tribe band (67.76%), relatives (64.48%), community (61.49%), and through self-discovery (47.76%). However, the descriptive and inferential statistics revealed varying factors affecting the medicinal plant knowledge among the sampled key informants.

When grouped according to location, there was no significant difference on their medicinal plant knowledge as revealed in Kruskal-Wallis test ( p = 0.379) where the city of Bayugan had the highest number of UR (Md = 112, n = 150), followed by the two municipalities, Esperanza (Md = 111, n = 95) and Sibagat (Md = 108, n = 90). These results showed an exchange of information on these adjacent localities among the Manobo community might it be the council of elders and members who are medicinal plant gatherers, peddlers, and traders.

However, when grouped according to education, respondents who had secondary level as their highest educational attainment (Md = 116, n = 167) showed the topmost medicinal plant knowledge when compared to primary (Md = 105, n = 57) and tertiary (Md = 92, n = 111) as revealed by the highly significant difference presented in Kruskal-Wallis test ( p < 0.001). These results implied that respondents who finished tertiary were more educated with modern medicine and highly acquainted with commercial drugs available over-the-counter for immediate treatment and therapy of their health problems. On the other hand, members with lower educational levels had more medicinal plant knowledge, and most traditional healers, gatherers, and peddlers finished at most on the secondary level.

When grouped according to gender, non-parametric tests revealed that men (Md = 116, n = 229) had more medicinal plant knowledge than women (Md = 104, n = 106), as demonstrated by the significant difference in both Mann-Whitney U test ( p < 0.001) and Kruskal-Wallis test ( p < 0.001). It can be observed that men had more medicinal plant knowledge in Agusan Manobo culture, an observation supported by the fact that in two of the three selected localities, the tribal healers were males, and most of the tribal officials were also males. These results revealed contrary to the previous statistical findings of [ 21 ] in the Ati culture of Visayas where women were more knowledgeable than men because they were more involved in medicinal plant gathering and peddling, and women also played a big role in caring for their sick children.

Also, knowledge of the participants when grouped according to social position varied significantly, as revealed by the Kruskal-Wallis test ( p < 0.001). These results showed that the tribal healers remained the most knowledgeable (Md = 189, n = 3), followed by the Manobo tribal officials (Md = 172, n = 93) with more medicinal plant knowledge when compared to other members of the community (Md = 104, n = 239). The medicinal plant knowledge also varied among the Manobo tribal officials, namely tribal leaders (Md = 178, n = 31), tribal IPMRs (Md = 177, n = 6), tribal chieftains (Md = 172, n = 45), Manobo tribal council of elders (Md = 164, n = 7), and Manobo NCIP focal persons (Md = 160, n = 4).

When grouped according to the occupation, non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test also significantly revealed ( p < 0.001) that informants with occupation in farming (Md = 118, n = 205) and animal husbandry (Md = 116, n = 47) had more medicinal plant knowledge compared to employed (Md = 98, n = 49) and unemployed (Md = 96, n = 16) informants. These results suggested that Manobo people working in line with agriculture were more exposed to medicinal plant knowledge. They were farming crops or raising animals in hinterlands and mountainous areas where most medicinal plants were located. Also, when grouped according to civil status, married informants (Md = 136, n = 147) showed higher medicinal plant knowledge than single ones (Md = 92, n = 188) as revealed by the very high significant difference in both Mann-Whitney U test ( p < 0.001) and Kruskal-Wallis test ( p < 0.001). These results implied that married respondents were more exposed during community gatherings, which involved discussions about medicinal plants with regard to their uses and applications. Exchange of information could be observed when couples were present during the scheduled tribal meetings.

Finally, when grouped according to age, descriptive and inferential statistics revealed that respondents from the age group of more than 65 years old had the highest medicinal plant knowledge (Md = 173, n = 37), followed by 50–65 years old (Md = 155, n = 53), 35–49 years old (Md = 102, n = 103), and 18–24 years old (Md = 96, n = 142), as revealed by the highly significant difference manifested in Kruskal-Wallis test ( p < 0.001). These results corresponded to our expectation because older informants most likely had more knowledge of medicinal plant uses and practices based on their long-term experience. These results may also imply that younger generations were becoming more acquainted and educated with modern therapeutic treatment making them more reluctant in their traditional medicinal plant practices like gathering and peddling. This transforming awareness, social, and cultural experiences could influence their medicinal plant interest, traditional knowledge, and attitudes among the Agusan Manobo . Younger generations are becoming more privileged to be educated as part of the government scholarship programs for indigenous communities resulting in migration to urban communities.

Medicinal plants used

A total of 122 reported medicinal plant species belonging to 108 genera and 51 families were classified in 16 use categories, as shown in Tables 3 and 4 . All informants interviewed agreed about the healing power of medicinal plants, but only 58.5% of the informants use medicinal plants to treat their health conditions. While some respondents (30.75%) directly relied on seeking for tribal healers in their community, still all these Babaylans utilized their known medicinal plants for immediate treatment and therapy. The Agusan Manobo community believed that the combined healing gift and prayers of their Babaylans could increase the healing potential of their medicinal plants. However, the minority (10.75%) of the key informants depended on seeing a medical practitioner and allied health workers in the treatment of their health conditions at a nearby hospital or health center.

Integrative molecular approach

Due to inconclusive morphological identification, unfamiliarity, and confusing species identity because of local name similarity, a total of 24 medicinal plant species were confirmed by DNA sequencing and by comparing the sequences with those present in the GenBank. This method supported ethnopharmacological data to be deposited in a repository, which is essential and helpful for future researchers and investigators for use by data mining approaches [ 73 ]. The molecular data can also be useful to the growing barcoding studies of medicinal plants. Putative identification based on literature, comparative morphology, and molecular sequences using the BLAST search query were tabulated (Table 5 ). The integrative approach combined with a priori data from putative identifications based on the interview data on local or vernacular names, local plant name dictionary, and assessment of available morphological characteristics along with a posteriori data from multiple universal markers, occurrence, and distribution of putative species in the Philippines. This paper applied a more detailed taxonomic identification since all reported medicinal plant taxa were identified (nearly all to species level), as shown in Table 4 . While all generic and familial affinities of medicinal plants were confirmed, four medicinal plants were not identified up to species level due to lack of morphological characteristics, concerning especially the reproductive parts of Piper and Ficus species, several cultivars and hybrids of Rosa species, and several species and varieties of Bauhinia species. Nevertheless, all generic and familial affinities of the medicinal plants documented here were verified combining similarity matching and a priori and a posteriori data as recommended by [ 42 ] to reduce ambiguity and to make it possible assigning a single species identification of their unidentifiable specimens. All determined plant samples with confusing identity having local name similarity and local species pairing, including plant samples with inconclusive morphological identification due to lack of reproductive parts upon collection, were accurately verified using an integrative molecular approach (Table 5 ).

Plant local name similarity

Most notable medicinal plants of Agusan Manobo have confusing species identity bearing similar local names, gender identity, and local species pairing. It is popular to use medicinal plants known as “Lunas” (meaning “cure”) with several plants associated under its name. For instance, the top three medicinal plants in terms of use value and cultural importance value have local name similarity, namely Lunas tag-uli ( Anodendron borneense (King & Gamble) D.J.Middleton), Lunas bagon tapol ( Piper decumanum L.), and Lunas kahoy ( Micromelum minutum (G.Forst.) Wight & Arn.), respectively. These three medicinal plants with the initial word named “Lunas” had almost similar use-reports in nine use categories with high use diversity (UD > 2.0). Other “Lunas”-named specimens such as Lunas bagon puti ( Piper nigrum L.), Lunas pilipo ( Acmella grandiflora (Turcz.) R.K.Jansen), Lunas buyo ( Piper aduncum L.), and Lunas gabi ( Alocasia zebrina Schott ex Van Houtte) also shared similarities from the top three mentioned samples in terms of ethnomedicinal properties as a treatment for cuts and wounds. Also, another three medicinal plants were locally classified with the initial word named “Talimughat” (meaning “recover”), namely “Talimughat lingin” ( Grewia laevigata Vahl), “Talimughat taas” ( Friesodielsia lanceolata (Merr.) Steen.), and “Talimughat pikas” ( Bauhinia sp.). These three medicinal plants were noted with high fidelity for postpartum care and recovery. Plant samples with high fidelity for anemia also had similar local names which were found to be same species, namely “Mayana kanapkap” ( Coleus scutellarioides (L.) Benth . ) and “Mayana pula” ( Coleus scutellarioides (L.) Benth . ).

Some medicinal plants also have attached “genders” (male or female) in their local names, which specify the more effective plant “gender” for a specific medicinal use or purpose. Examples are “Kapayas laki” ( Carica papaya L., male), “Dupang bae” ( Urena lobata L., female), and “Gapas-gapas bae” ( Erechtites valerianifolius (Link ex Spreng.) DC . , female) as effective treatments for dengue virus, postpartum care and recovery, and gas pain and flatulence, respectively. Besides, most species with high use values had local species pairing which were classified by the tribe according to distinct white and red coloration, namely “puti” and “tapol,” respectively, with the latter as more effective than the former in treatment for various health conditions. The following recognized local species pairs as white and red plant samples, respectively, are “Alibangbang puti” ( Phanera semibifida (Roxb.) Benth.) and “Alibangbang tapol” ( Phanera semibifida (Roxb.) Benth.); “Banti puti” ( Omalanthus macradenius Pax & Hoffm.) and “Banti tapol” ( Omalanthus macradenius Pax & Hoffm.); “Lunas-bagon puti” ( Piper nigrum ) and “Lunas-bagon tapol” ( Piper decumanum ); “Tobog puti” ( Ficus fistulosa Reinw. ex Blume) and “Tobog tapol” ( Ficus cassidyana Elmer); and “Tuba-tuba puti” ( Jatropha curcas L.) and “Tuba-tuba tapol” ( Jatropha gossypifolia L.). Local species pairing of “Alibangbang puti” and “Alibangbang tapol” was found to be similar species ( Phanera semibifida (Roxb.) Benth.). Another species pair, “Banti puti” and “Banti tapol” was also found to be similar species ( Omalanthus macradenius Pax & Hoffm.). However, molecular confirmation of all species pairs by the locals did not necessarily point to the same species but were mostly referring to another species. An example study resolving species identity of Piper species used by the Agusan Manobo being a sterile species and unidentifiable by present morphology having confusing local names with the initial word “Lunas” has been molecularly confirmed lately using integrative molecular approach [ 19 ]. Thus, it is always important in any ethnomedicinal, ethnobotanical, and ethnopharmacological studies to obtain the correct identification of medicinal plants by integrating molecular data like this for accuracy, consistency, and dependable species identity for future pharmacological evaluation and natural product investigations.

Species molecular confirmation

Most of all extracted samples for molecular analysis were successfully amplified and sequenced (90%) using multiple universal markers (Table 5 ). Some medicinal plants could not be successfully amplified using the given primer due to low levels of DNA present in the samples [ 74 ] or plant secondary metabolites present as inhibitory factors [ 75 ]. Molecular data obtained were also subject to the availability of sequences of plant samples in the GenBank. The 24 species identified were tabulated in Table 6 , showing six endemic species (27.3%) [ 56 ] and conservation status of all assessed species (37.5%) [ 76 , 77 ] presented five least concern species (83.3%) and a vulnerable species, Cinnamomum mercadoi S.Vidal (16.7%). All edited sequences of each of the four DNA markers in fasta file format were attached as supplementary materials (see Additional files 2 – 5 ) for future reference.

The most certain identity confirmed by this molecular analysis is the familial and generic affinity wherein the specific epithet of each of the 24 medicinal plants presented had to be verified for its occurrence and distribution in the country. All species identified using simple and optimized BLAST-based sequence matching results were further reviewed on their present morphology using taxonomic keys and comparing images and specimens before consulting an expert. Some species names presented in BLAST search query have synonyms showing similar genus among species within 5 points deviation down of the max score. In contrast, others have several genera but under the same family. Two species with molecular data, namely Bauhinia sp. and Ficus sp., were only confirmed up to the genus level due to limited morphological material and because of a high number of varieties, species, and subspecies. A sterile Piper species was confirmed as P. nigrum based on its diagnostic characterization, which could be a new variety obtained only in the wild among the respondents and not the widely cultivated spice known as the world’s most consumed peppercorn.

Of all DNA markers used in this study, two markers, psb A- trn H and trn L-F (cpDNA) successfully amplified and sequenced all 24 uncertain species (100%). A total of 21 species (88%) were amplified and sequenced using the marker ITS (nrDNA), while the coding marker, mat K (cpDNA), recorded at least 17 amplified and sequenced species (71%). In this case, molecular data could increase its identification rate by using multiple universal markers. Several coding and non-coding regions were tested in plants, but a single locus has limited resolving capabilities for closely related species [ 79 , 80 ]. While local names are essential in ethnopharmacological studies, complexities of these local names could lead to confusion and ambiguity, hence, a need for further molecular analysis [ 19 ]. A number of ethnobotanical studies consider vernacular names coupled with morphological and molecular confirmation as part of the identification diagnostics [ 19 , 42 , 81 , 82 , 83 ].

Collection sites

The majority (57%) of the medicinal plants were collected in the wild, while some were collected within the community village (7.2%) and the houses (4.8%). Some local people were cultivating some of these medicinal plants near homes for their convenience, but collecting medicinal plants in the wild during seasonal times or in case of immediate treatment was highly encouraged for efficacy as the locals believed that the plants should grow in their natural setting rather than cultivation. Scientific studies tend to support the idea of medicinal plant collection in the wild because plant secondary metabolites will be mostly expressed in the natural setting under environmental stress and conditions, whereby they could not be comparably expressed under monoculture conditions [ 84 ]. Higher levels of secondary metabolites were also reported in wild populations where plants grow slowly, unlike in much faster-growing monocultures [ 85 ].

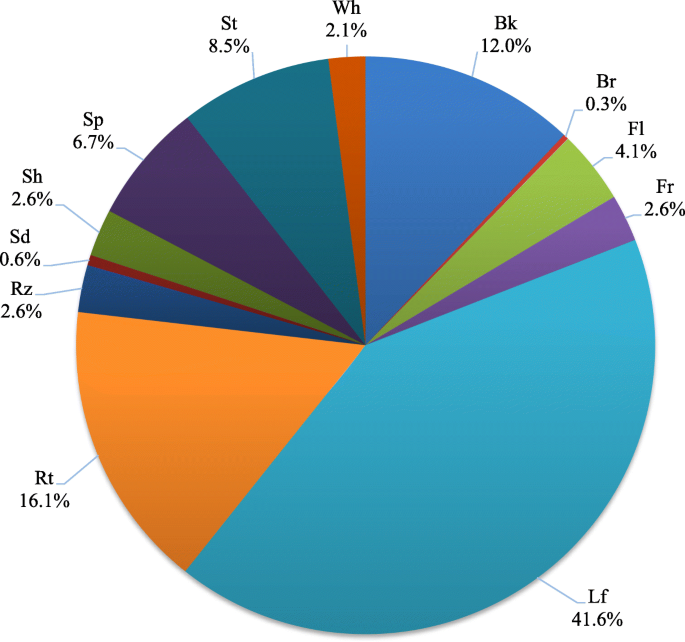

Plant parts used

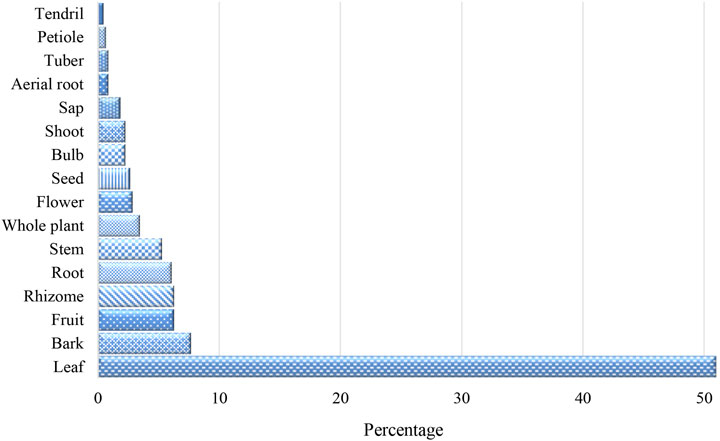

All plant parts were used from different plant species against a variety of diseases. The most frequently used plant parts were the leaves (41.6%), followed by roots (16.1%), barks (12.0%), stems (8.5%), sap or latex (6.7%), and flowers (4.1%) (Fig. 2 ). Sometimes, more than one plant part of the same species is used in combination, like leaves, barks, stems, and roots for preparation and administration, which the locals believed to have a synergistic effect and a more effective medication.

Plant parts used by the Agusan Manobo for medicinal application. Bk, barks; Br, branches; Fl, flowers; Fr, fruits; Lf, leaves; Rt, roots; Rz, rhizomes; Sd, seeds; Sh, shoots; Sp, sap or latex; St, stems; Wh, whole plant

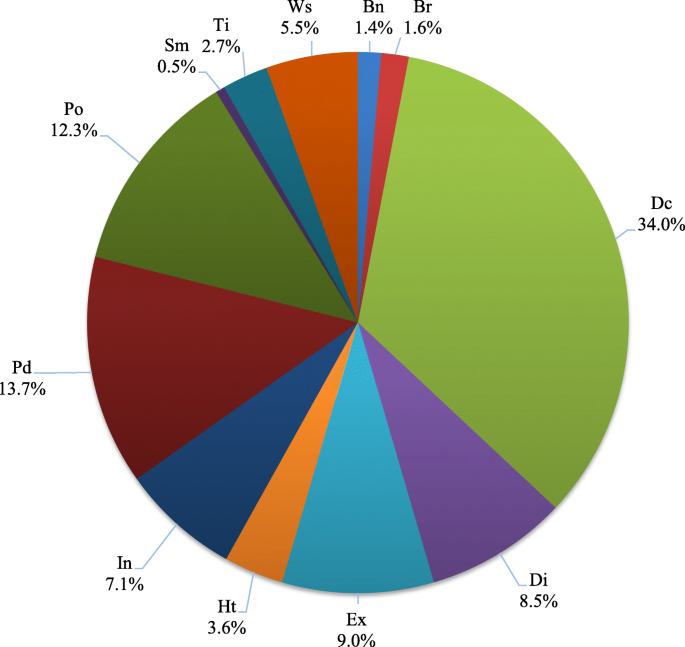

Preparation and administration

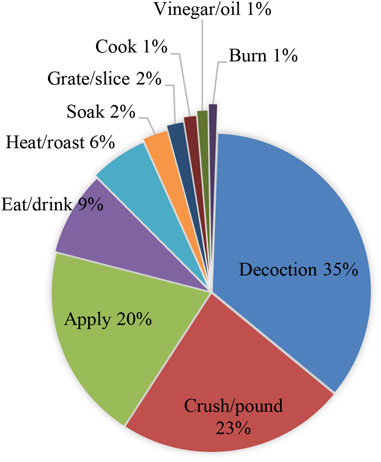

The primary preparation method was decoction (34.0%), followed by pounding, crushing, rubbing, grinding, and powdering (13.7%); poultice (12.3%); extracting (9.0%); directly applying or eating (8.5%); infusion (7.1%); applying as wash, bath, hot compress (5.5%); heating or warming (3.6%); tincture (2.7%); brewing (1.6%); burning (1.4%); and steaming (0.5%) as depicted in Fig. 3 . The more common route of administration was internal (60%) rather than external (40%). This result is contrary to the previous reports in the other Philippine major island ethnic tribes like the Ati Negrito community of Visayas [ 21 ] and the Ivatan community in Luzon [ 24 ] where the external application was more common. While external administration could be safer, according to the Agusan Manobo , the internal application was more common since most of their health conditions were associated internally, making decoction as their most common preparation. In cases of external diseases and illnesses, more prolonged coconut oil infusions of medicinal plant stems and barks were often applied.

Mode of preparation of medicinal plants used by the Agusan Manobo . Bn, burning; Br, brewing; Dc, decoction; Di, directly applying or eating; Ex, extracting; Ht, heating or warming; In, infusion; Pd, pounding, crushing, rubbing, grinding, powdering; Po, poultice; Sm, steaming; Ti, tincture; Ws, as wash, bath, hot compress

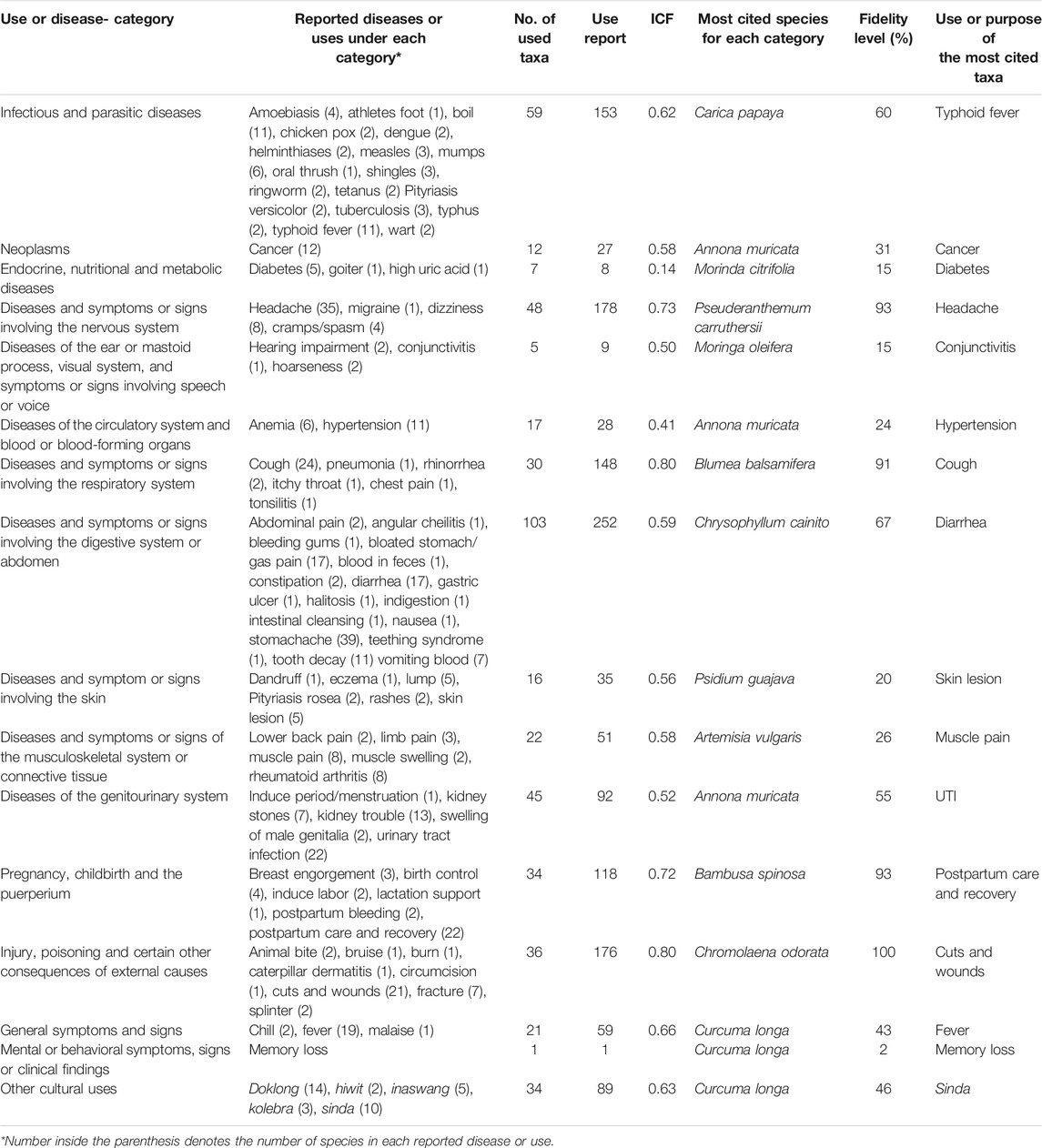

Use categories (UC)

Reported medicinal uses of plants in this study were grouped into 16 category names based on the citations of informants and the likeness to the use category (Table 3 ). Reported uses and diseases in medical terms were verified by the assigned local physicians and allied workers, nearby hospitals and health centers to confirm disease occurrence and epidemiology in the area. A total of 120 reported uses or diseases treated by 122 plant species were documented in the study sites.

Use-report (UR) and use value (UV)

Both UR and UV represent the relative importance of medicinal plants for certain categorized uses or diseases. High values were considered the most important species among the Agusan Manobo . Five medicinal plants with the highest URs (more than 900) as well as UVs (more than 2.5) were Anodendron borneense (UR = 1134; UV = 3.39) in 12 categories, Piper decumanum (UR = 1018; UV = 3.04) in 9 categories, Micromelum minutum (UR = 955; UV = 2.85) in 9 categories, Arcangelisia flava (L.) Merr. (UR = 922; UV = 2.75) in 10 categories, and Cinnamomum mercadoi (UR = 908; UV = 2.71) in 8 categories, as shown in Table 4 . These high UR and UV plants were the most frequently used plant species based on high fidelity level for pregnancy (FL = 88%), skin rashes and itchiness (FL = 95%), hemorrhage (FL = 97%), tumor (FL = 87%), and stomach trouble (FL = 100%), respectively, (Table 11 ).

The respondents consistently reported these in all study sites, but only harvested in the wild. Some other plants can be cultivated with high UVs, as shown in the top 20 species ranked by UV (Table 7 ). While high UV species can often be harvested for medicinal use and purpose, these important species call for conservation priority [ 86 ]. The four medicinal plants included among the top 10 recommended medicinal plants by the Department of Health (DOH) of the Philippines, were cultivated by the Agusan Manobo respondents within their community. These scientifically validated medicinal plants were also reported with high URs, namely “Bayabas” Psidium guajava L. (275) “Lagundi” Vitex negundo L. (475), “Gabon” Blumea balsamifera (L.) DC. (412), and “Tsaang gubat” Ehretia microphylla Lam. (336).

Cultural importance value (CIV)

CIV often identifies species with diverse use-reports in different use categories, which is relatively dependent on the sum of the proportion of informants who cited the medicinal plant use. The usefulness of species based on the number of informants for each species is not only accounted for this additive index but also its versatility [ 47 ]. The top 20 species ranked by CIV included some species with high UV and UD (Table 8 ).

Use diversity (UD)

UD determines medicinal plants dependent on the variety of uses in different use categories. This index considers the widespread contribution of each use category according to the number of reported diseases treated. The top 20 species with high UD did not include all high values of UV and CIV (Table 9 ).

Correlation of the basic values and indices

Table 10 presents the Spearman correlations among all the five variables used to quantify ethnopharmacological data. All correlations were moderate to strongly positive and significant at p < 0.01 ( n = 125). That is, as one variable increases, the other also increases. Of all the variables, UV is entirely dependent on UR (1.00), while UD is highly dependent on UC (0.97). However, the subjectivity of selection criteria among the use categories was avoided as the researcher consulted with physicians and other medical experts in the locality. The correlation index between UV and CIV was quite high (0.73), meaning that the relative importance of medicinal plants used among the Agusan Manobo was relatively dependent on the number of use mentions among the key informants as counted in UR. An interesting point that appeared to corroborate these data is that the number of UR was positively correlated (0.71–1.00), among other basic values and indices. These variables were correlated with the number of uses for a particular ailment and the number of categories considered. Thus, it can be argued that the relative importance of medicinal plants documented in this study was relatively dependent at least, on the number of use-reports among the key informants and the number of use categories following an objective manner. Despite the advantages and uses of these values and indices in determining the relative importance and usefulness of medicinal plants, it is practical to note that no single index can give information about the complete picture of plant importance.

Informant consensus factor (ICF)

ICF measures the agreement among informants on the use of plant species for a particular purpose or disease category. While the agreement among the key informants varies in different categories, the ICF values are all greater than or equal to 0.97 (Table 3 ). These results showed that the exchange of information could be evident among the Agusan Manobo community on their medicinal plant uses and practices. Among the 16 use categories, four categories, namely diseases of the digestive system (DDS), diseases of the skin (DOS), abnormal signs and symptoms (ASS), and other problems of external causes (OEC) had the highest ICF value of 0.99.

Fidelity level (FL)

FL implies the most preferred medicinal plant for a particular disease or purpose. FL value ranges from 1 to 100% depending on the URs cited by the informants for a given species for a particular ailment. Seven species were found with the maximum FL of 100%, including the identified species with the highest number of use mentions, Carica papaya , Premna odorata , Cinnamomum mercadoi , Tinospora crispa , Ficus concinna , Piper decumanum , and Pipturus arborescens which are used for dengue fever, cough with phlegm, stomach trouble, joint pain, fracture and dislocation, anesthetic, and herpes simplex, respectively (Table 11 ).

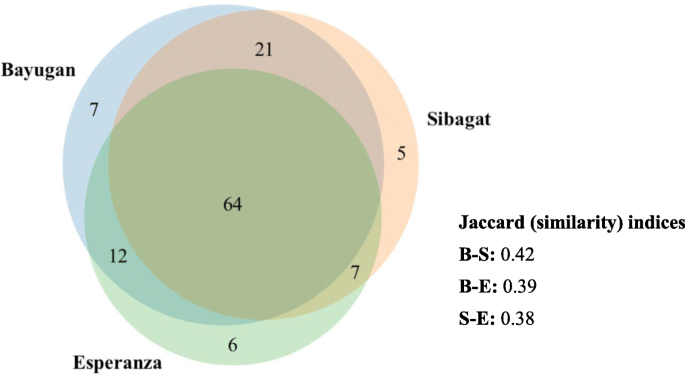

Jaccard’s similarity index (JI)

This is the first ethnopharmacological or ethnobotanical study of indigenous peoples in the province of Agusan del Sur. The variation of the medicinal plants used among the three studied localities was shown in JI (Fig. 4 ). The most overlap of the obtained data and the Jaccard index (similarity) was between the city of Bayugan and the municipality of Sibagat (JI = 0.42), and the least one was between both municipalities of Esperanza and Sibagat (0.38). However, the degree of similarity among the three adjacent localities was proximate with JI ranged from 0.38 to 0.42. While JI conveyed a similarity index ca. 39.7%, the actual overlap is 52.5% (64 species cited among the localities). This similarity could be observed on their comparable ecological types being upland and well-drained areas and due to the active exchange of information on the uses of medicinal plants among the communities during monthly social meetings and preparations in the province of Agusan del Sur.

Overlap in the medicinal plants collected in the three studied localities (city of Bayugan and the municipalities of Sibagat and Esperanza)

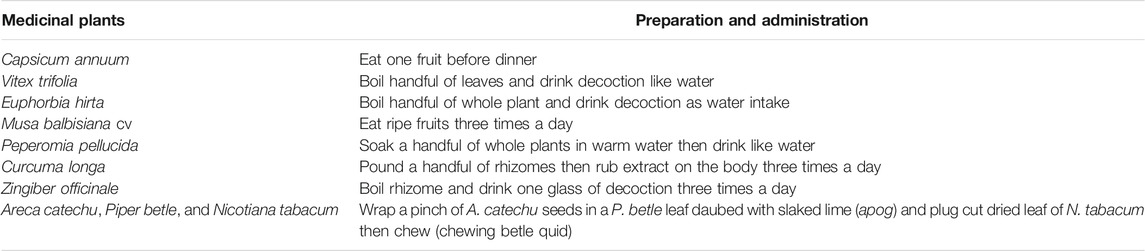

Dosage, frequency, and experienced adverse or side effects of using medicinal plants

For a detailed ethnopharmacological study, it is essential to consider the therapeutic use, medication action, and possible side effects. This study involved documenting the quantity or dosage, administration frequency, and experienced adverse or side effects, as shown in Table 4 . A particular number of plant parts were followed in their mode of preparation. Having leaves as the most frequently used medicinal plant part, 3–5 leaves (or at least an odd number) of decocted, heated, and pounded leaves should be applied. Most of the medicinal plants (82%) were reported by the key informants with no experience of adverse or side effects, while 18% of medicinal plants were experienced with adverse or side effects. There were seven medicinal plants reported to cause abortion in pregnant women once taken or applied. Other listed medicinal plants, when taken in excess, can cause other adverse or side effects. Four of these medicinal plants can cause anemia, dizziness, and weakening, while other plants can cause acid reflux and hypocupremia, burn, and allergy and are even poisonous when eaten or applied. Other reported cases concern excessive intake, which can cause blood viscosity, intestinal weakening, thrombocytopenia, and abnormalities in lactating mothers. These reported adverse or side effects were verified by the attending local medical practitioners and allied medical workers during their hospital visits and in times of emergency. It can be argued that not all medicinal plants used by the tribe are safe for use with no side effects. Thus, it is essential to obtain the reported adverse effects or possible side effects of cited medicinal plants by the informants in all ethnopharmacological studies like this.

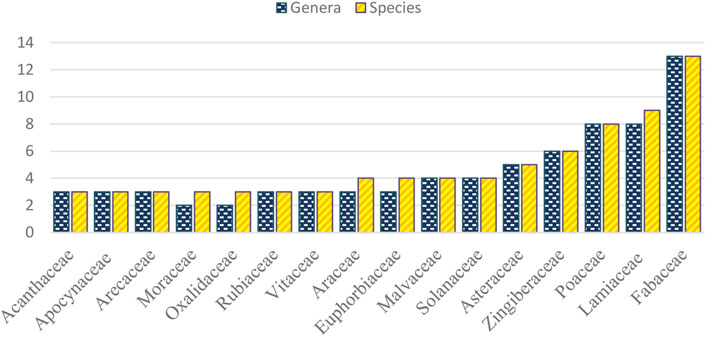

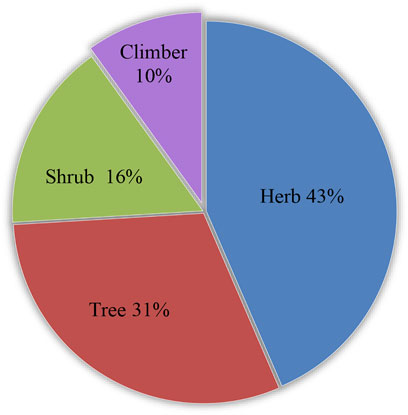

This ethnopharmacological documentation recorded a total of 122 medicinal plant species belonging to 108 genera and 51 families across 16 use or disease categories. The majority of medicinal plants are trees (36%) and herbs (33%), which are mostly found in the wild, while some are cultivated. These are followed by 17% shrubs, 11% climbers, 2% grasses, and 1% ferns. The highest percentage of medicinal trees documented in this study is parallel with the earlier ethnobotanical studies [ 21 , 87 ]. The highest frequency of using leaves and aerial plant organs was also reported in several ethnobotanical studies in the Philippines [ 21 , 24 , 25 , 87 , 88 , 89 , 90 ] and other countries [ 91 , 92 , 93 ]. The highest frequency of decoction for preparation and administration is similar to previous ethnobotanical investigations [ 21 , 87 , 88 , 89 , 90 ].

Lamiaceae was the most represented family with 12 species, followed by Asteraceae with 11, Moraceae with eight species, and Fabaceae with six species. This result is contrary to previous ethnobotanical studies in which Asteraceae were the most represented family [ 24 , 88 , 89 , 90 ]. The Lamiaceae (mint family) possess a wide variety of ornamental, medicinal, and aromatic plants producing essential oils that are used in traditional and modern medicine, food, cosmetics, and pharmaceutical industry [ 94 ]. This family is known for effective pain modulation with potential analgesic or antinociceptive effects, which includes several aromatic medicinal spices like mint, oregano, basil, and rosemary [ 95 ]. Asteraceae (the aster, daisy, composite, or sunflower family) are the largest family of flowering plants which were reported to have pharmacological activities such as antitumor, antibacterial, antifungal, and anti-inflammatory [ 96 ] containing phytochemical compounds such as polyphenols, flavonoids, and diterpenoids [ 97 , 98 ]. The Moraceae (fig family) was reported to have wide variety of chemical constituents with potential biological activities as previously investigated by [ 99 ] in Ficus racemosa L., and [ 100 ] in Ficus carica L., and [ 101 ] in Ficus benjamina L. Fabaceae (pea family) which is the third largest family also contain various bioactive constituents with potential pharmacological and toxicological effects [ 102 ]. A member of this family which has long been cultivated and introduced in the Philippines, Gliricidia sepium (Jacq.) Kunth ex Steud., was investigated to have antimicrobial and antioxidant activities, as well as several phytochemicals present [ 13 ].

The Department of Health (DOH) of the Philippines has continually endorsed 10 medicinal plant species in its traditional health maintenance program: (1) Cassia alata L., (2) Momordica charantia L., (3) Allium sativum L., (4) Psidium guajava L., (5) Vitex negundo L., (6) Quisqualis indica L., (7) Blumea balsamifera (L.) DC., (8) Ehretia microphylla Lam., (9) Peperomia pellucida (L.) Kunth, and (10) Clinopodium douglasii (Benth.) Kuntze . Of all these 10 recommended and clinically tested medicinal plants, four species were included in this survey.

Apparently, the societal gaps which differentiate educational level, gender, position, occupation, and age among the Manobo indigenous community may result in the disappearance of their medicinal plant knowledge and traditional practices. While there was no significant difference in their medicinal plant knowledge in different locations, it is still highly important to document their medicinal plant knowledge to perpetuate their cultural tradition and medicinal practices, as well as protect and conserve these important plant genetic resources.

Many ethnobotanical studies include vernacular names as part of the putative identification. While vernacular names are useful in ethnopharmacology, pharmacognosy, and pharmacovigilance [ 83 , 103 ], reliance on these vernacular names for species identification and classification can cause ambiguity and incorrect identification resulting to research invalidation [ 104 ]. DNA-based identification is a useful tool for accurate species identification. Correct identification of a medicinal plant should be examined using molecular data [ 105 ] for consistency of species and pharmacological investigations of natural products [ 106 ]. Although plant-based drug discovery from ethnobotanical data provides future drug leads, authentication of the plant material is a great challenge and opportunity [ 107 ].

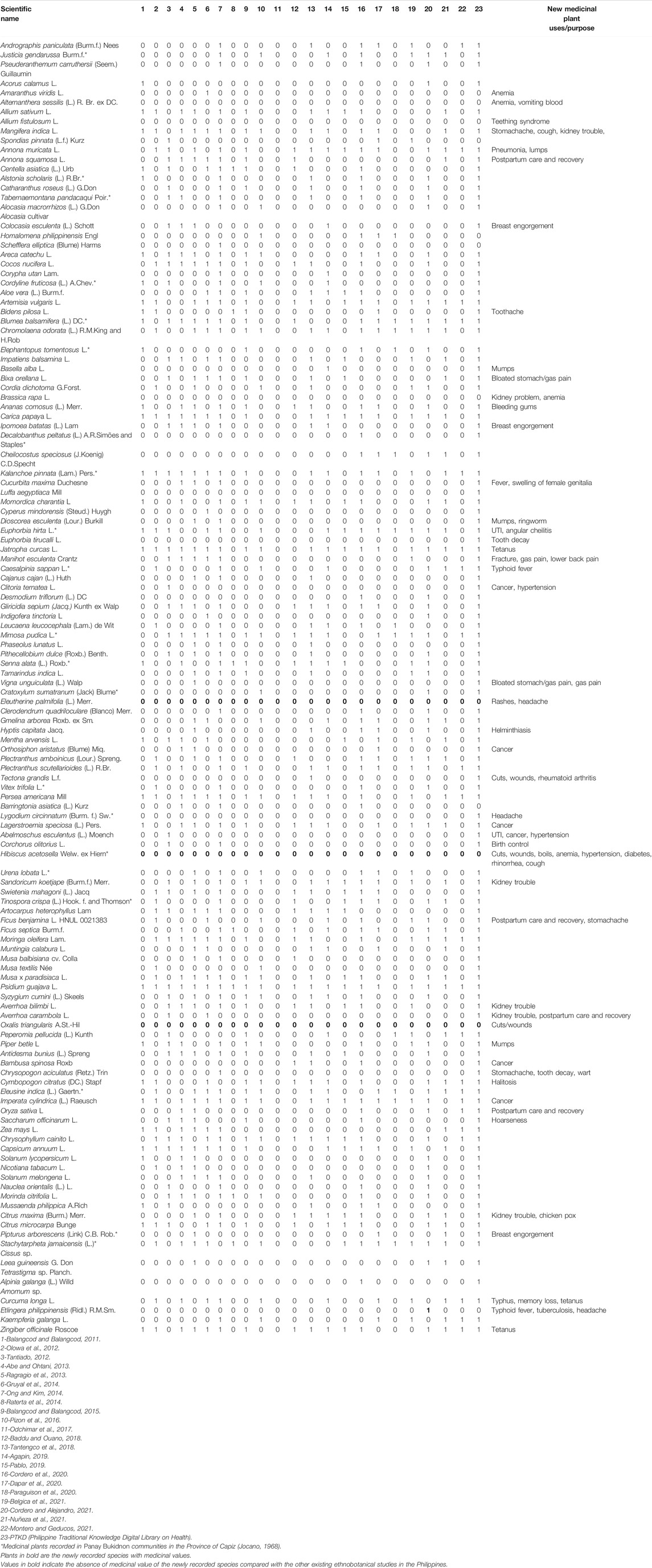

Comparison with previous ethnobotanical studies

Several ethnobotanical and ethnomedicinal studies were conducted in the Philippines, but few involve quantitative analyses in their studies. The majority of ethnobotanical studies conducted in the Philippines purposively selected key informants who are just knowledgeable of their medicinal plants like residents, traditional healers, herbalists, gardeners, traders, and elders, but a limited count of researches focused on specific IPs or tribal communities in the country.

Among the three major islands in the Philippines (Luzon, Visayas, and Mindanao), the island of Mindanao is still underdocumented despite its largest population of indigenous cultural communities/indigenous peoples (ICCs/IPs) in the country. In Luzon, four indigenous groups were documented, namely the Kalanguya tribe in Tinoc, Ifugao [ 108 ]; the Ivatan in Batan Island Batanes [ 24 ]; the Ayta in Dinalupihan, Bataan [ 109 ]; and the Ilongot-Eǵongot in Maria Aurora, Aurora [ 110 ], communities. The plant utilization among local communities was also documented by [ 25 ] in Kabayan, Benguet Province, namely Ibaloi , Kankanaey and Kalanguya in addition to the earlier recorded tribes such as the Negritos [ 111 ], the Tasadays [ 112 , 113 ], the Ifugao [ 114 , 115 ] and the Bontoc [ 116 ]. Other studies of cultural communities involve indigenous knowledge and practices for sustainable management like the Ifugao forests in Cordillera, Philippines [ 117 ].

In Visayas, only the Ati Negrito of Guimaras island [ 21 ], while in Mindanao, three tribes were studied, namely the Higaonon tribe of Iligan City [ 88 ], Subanen tribe of Dumingag, Zamboanga del Sur [ 89 ]; Muslim Maranaos of Iligan City [ 90 ]; Subanen tribe of Lapuyan, Zamboanga del Sur [ 87 ]; and Tagabawa tribe of Davao del Sur [ 118 ]. Of all reported ethnobotanical studies in Mindanao, this is the first study utilizing detailed quantitative analysis of relative importance, effectivity consensus, correlation of indices, and the extent of the potential use of each medicinal plant species among the ICCs/IPs. Moreover, this study also integrated molecular confirmation for the first time applying multiple universal markers and coalescing a priori and a posteriori data for accurate species identification to resolve complex plant local or vernacular names and sterile or non-reproductive plant specimens.

In comparison with existing ethnobotanical studies in the Philippines, a novel plant medicinal use was recorded, namely Anodendron borneense with no existing records of ethnobotanical and pharmacological investigations in the world to date. The ethnopharmacological profile of this medicinal plant is a novel finding in this study, which is consistently on the top list among the values or indices used (UR, UV, and CIV), which is only known among the Agusan Manobo in the province of Agusan del Sur, Philippines. Incorporating data of experienced adverse or side effects in this study introduces a more detailed ethnopharmacological documentation in the Philippines, which could be a reference material for future ethnomedicinal, biological, and pharmacological studies.

Limitations of the present study

Ethnobotanical research broadly encompasses like ethnopharmacology, which involves field-based investigations. However, most of the remote areas and barangays in various municipalities and cities of the Philippines were not always safe from rebels and communists against the Philippine government. Majority of the Manobo tribes documented here live in far-flung hinterlands, remote upland areas alongside rivers, valleys, and creeks having security threats from the rebel movement known as the New People's Army (NPA). Study sites included here obtained security clearance from the provincial and local government administrations to ensure safety and accessibility in the area, and the availability of key informants on the actual documentation and field walks. Language barriers were barely encountered since most respondents could speak the national Filipino language and/or the regional Cebuano or Visayan language aside from their Minanubu dialect. Phenology and year-round seasonal variations are essential factors to consider for accurate observation of the plant and collection of specimens with complete reproductive parts. Some respondents are sometimes unwilling to share their medicinal plant knowledge with others due to their previous experience being taken advantage of by business-related parties of drug and pharmaceutical companies. It was also observed that most respondents are becoming educated with the help of government education programs for IPs, which made them more resistant to allowing themselves to be the subject of study by visitors and outsiders.

In spite of that, it is very important to gain trust, confidence, and respect among the Agusan Manobo community by embracing their rich cultural tradition through ritual observation and tribal immersion within their community. Although they maintain secrecy about their medicinal plant use and knowledge, it is also beneficial to practice keeping their knowledge from possible overexploitation of their medicinal plant resources. This study is the first in the country documenting the rich ethnopharmacological practices of indigenous tribes coupled with integrative molecular confirmation of medicinal plants used. It is highly important to recognize the role of indigenous cultural communities/indigenous peoples (ICCs/IPs) in the Philippines for shared information of ethnopharmacological practices for future preservation of knowledge and conservation priorities of their plant genetic resources. This will benefit their children and future generations before their knowledge becomes lost and forgotten.

Research highlights

The current study revealed the rich ethnopharmacological practices, medicinal plant uses, and knowledge of the Manobo tribe in Agusan del Sur, Philippines.

Exchange of information among the Agusan Manobo communities was observed in different localities; however, the younger generation has a potential decline of interest due to their acquaintance of over-the-counter drugs and modern medicines.

This study reinforced the application of integrative molecular confirmation for medicinal plant species lacking reproductive parts upon collection and/or unidentifiable by present morphology (sterile or non-reproductive) plant material.

Novel medicinal use and some new ethnopharmacological information of medicinal plants were reported in this study.

The consolidated data of this quantitative ethnopharmacology study contributes to the repository of medicinal plant knowledge and the rich source of information for scientists, physicians, and experts such as botanists, taxonomists, phytochemists, pharmacists, environmentalists, conservation biologists, medical doctors, and allied professionals.

This study concluded the culturally rich ethnomedicinal knowledge and ethnopharmacological practices of the Manobo tribe in Agusan del Sur, Philippines. The results of the study revealed a high diversity of medicinal plants used by the Agusan Manobo with 122 species utilized in 16 use categories. Like any other ethnolinguistic indigenous group in the country, traditional knowledge may be lost or forgotten due to possible migration, acculturation, and declining interest of the younger generation in response to the increasing availability of commercial over-the-counter medicine. Their medicinal plants are known by a limited number of individuals, mostly by their healers, elders, and tribal officials. This quantitative ethnopharmacological documentation is the first to show the high consensus and relative importance of medicinal plants used by the Agusan Manobo and provides molecular confirmation of their medicinal plant species with uncertain identity. The combined quantitative ethnopharmacological documentation and species confirmation using an integrative molecular approach of medicinal plants used in traditional medicine is a breakthrough for obtaining more detailed and comprehensive findings that will be a valuable contribution to the repository of knowledge. The findings of this study will serve as reference material for future systematic, biochemical, and pharmacological studies. While the findings of this study are promising, regarding new potential therapeutic agents for healthcare improvement, it is of utmost concern to reconsider important medicinal plant species for conservation priorities as part of the government programs and initiatives to perpetuate the national and world heritage of traditional knowledge on medicinal plants used by many diverse cultural communities.

Availability of data and materials

The authors declare that sequencing data of 24 species identified supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary information files.

UNESCO. Report of the IBC on traditional medicine systems and their ethical implications. 2013. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000217457 . Accessed 15 Aug 2019.

WHO. World Health Organization traditional medicine strategy: 2014-2023. WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data. 2013. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/92455/9789241506090_eng.pdf;jsessionid=8CE16D76ACA6151F5929619AA9B1A411?sequence=1 . Accessed 16 Aug 2019.

WHO. Regulatory situation of herbal medicines. A worldwide review. Geneva: World Health Organization. 1998. p. 1–5.

Jamshidi-Kia F, Lorigooini Z, Amini-Khoei H. Medicinal plants: past history and future perspective. J HerbMed Pharmacol. 2018;7:1–7. https://doi.org/10.15171/jhp.2018.01 .

Article Google Scholar

Farnsworth NR. Ethnopharmacology and drug development. Ciba found Symp. 1994;185:42–59. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470514634.ch4 .

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Schippmann U, Cunningham AB, Leaman DJ. Impact of cultivation of medicinal plants on biodiversity: global trends and issues. In: FAO, biodiversity and the ecosystem approach in agriculture, forestry and fisheries. Satellite event on the occasion of the Ninth Regular Session of the Commission on Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture, Rome, 12-13 October 2002. Inter-Departmental Working Group on Biological Diversity for Food and Agriculture, Rome, Italy. 2002. p. 143–167.

Karki M, William JT. Priority species of medicinal plants in South Asia. In: Report of an Expert Consultation on Medicinal Plants Species Prioritization for South Asia held on 22-23 1997 New Delhi, India; 1999.

Madulid DA, Gaerlan FJM, Romero EM, Agoo EMG. Ethnopharmacological study of the Ati tribe in Nagpana, Barotac Viejo. Iloilo. Acta Manil. 1989;38:25–40.

Google Scholar

Burns G. Nature-guided therapy: brief integrative strategies for health and well-Being. Taylor & Francis. 1998. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315803586 . Accessed 18 Aug 2019.

Book Google Scholar

Dela Cruz P, Ramos AG. Indigenous health knowledge systems in the Philippines: a literature survey. Paper presented at the 13th CONSAL Conference, Manila, Philippines; 2006.

Eusebio J, Umali B. Inventory, documentation and status of medicinal plants research in the Philippines. Medicinal Plants Research in Asia, Volume 1: The framework and project workplans. In Batugal, A., Kanniah, J., Young, L.S. & Oliver, J. edition. International Plant Genetic Research Institute-Regional Office of Asia, the Pacific and Oceana (IPGRI-APO), Serdang, Selangor, DE, Malaysia; 2004.

Tan JG, Sia IC. The best 100 Philippine medicinal plants: The National Library Cataloguing in Publication; 2014.

Abdulaziz AA, Dapar MLG, Manting MME, Torres AJ, Aranas AT, Mindo RAR, Cabrido CK, Demayo CG. Qualitative evaluation of the antimicrobial, antioxidant, and medicinally important phytochemical constituents of the ethanolic extracts of the leaves of Gliricidia sepium (Jacq.). Pharmacophore. 2019;10:72–83.

Añides JA, Dapar MLG, Aranas AT, Mindo RAR, Manting MME, Torres MAJ, Demayo CG. Phytochemical, antioxidant and antimicrobial properties of the white variety of ‘Sibujing’ ( Allium ampeloprasum ). Pharmacophore. 2019;10:1–12.

Dapar MLD, Demayo CGD, Senarath WTPSK. Antimicrobial and cellular metabolic inhibitory properties of the ethanolic extract from the bark of ‘Lunas-Bagon’ ( Lunasia sp.). Int J Pharm Sci Res. 2018;9:88–97. https://doi.org/10.13040/IJPSR.0975-8232.9(1).88-97 .

Article CAS Google Scholar

Dela Peña JF, Dapar MLG, Aranas AT, Mindo RAR, Cabrido CK, Torres MAJ, Manting MME, Demayo CG. Assessment of antimicrobial, antioxidant and cytotoxic properties of the ethanolic extract from Dracontomelon dao (Blanco) Merr. & Rolfe. Pharmacophore. 2019;10:18–29.

Nadayag J, Dapar MLG, Aranas AT, Mindo RAR, Cabrido CK, Manting MME, Torres AJ, Demayo CG. Qualitative assessment of the antimicrobial, antioxidant, and phytochemical properties of the ethanolic extracts of the inner bark of Atuna racemosa . Pharmacophore. 2019;10:52–9.

Uy IA, Dapar MLG, Aranas AT, Mindo RAR, Manting MME, Torres MAJ, Demayo CG. Qualitative assessment of the antimicrobial, antioxidant, phytochemical properties of the ethanolic extracts of the roots of Cocos nucifera L. Pharmacophore. 2019;10:63–75.

Dapar MLG, Demayo CG, Meve U, Liede-Schuman S, Alejandro GJD. Molecular confirmation, constituents and cytotoxicity evaluation of two medicinal Piper species used by the Manobo tribe of Agusan del Sur. Philippines. Phytochem Lett. 2020;36:24–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phytol.2020.01.017 .

Tan MA, Lagamayo MWD, Alejandro GJD, An SSA. Anti-amyloidogenic and cyclooxygenase inhibitory activity of Guettarda speciosa . Molecules. 2019;24:4112. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules24224112 .

Article CAS PubMed Central Google Scholar

Ong HG, Kim YD. Quantitative ethnobotanical study of the medicinal plants used by the Ati Negrito indigenous group in Guimaras island. Philippines. J Ethnopharmacol. 2014;157:228–42 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2014.09.015 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Bruni A, Ballero M, Poli F. Quantitative ethnopharmacological study of the Campidano Valley and Urzulei district, Sardinia. Italy. J Ethnopharmacol. 1997;57:97–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-8741(97)00055-X .

Rivera D, Obón C, Inocencio C, Heinrich M, Verde A, Fajardo J, Palazón JA. Gathered food plants in the mountains of Castilla-La Mancha (Spain): ethnobotany and multivariate analysis. Econ Bot. 2007;61:269–89.

Abe R, Ohtani K. An ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants and traditional therapies on Batan island, the Philippines. J Ethnopharmacol. 2013;145:554–65 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2014.09.015 .

Balangcod TD, Balangcod KD. Plants and culture: plant utilization among the local communities in Kabayan, Benguet Province Philippines. Indian J Tradit Know. 2018;17:609–22.

ILO. Indigenous peoples development programme (IPDP). 2014. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/%2D%2D-asia/%2D%2D-ro-bangkok/%2D%2D-ilo-manila/documents/publication/wcms_245610.pdf . Accessed 18 Aug 2019.

PSA. 2010 census of population and housing: definition of terms and concepts. Quezon City, Philippines: Philippine Statistics Authority; 2016.

NCIP. Primer on census for indigenous peoples. Quezon City, Philippines: National Commission on Indigenous Peoples; 2010.

UNDP. Indigenous peoples in the Philippines. 2010. http://www.ph.undp.org/content/philippines/en/home/library/democratic_governance/FastFacts-IPs.html . Accessed 17 Aug 2019.

NCCA. Manobo. 2015. http://ncca.gov.ph/about-culture-and-arts/culture-profile/manobo/ . Accessed 18 Aug 2019.

Felix MLE. Exploring the indigenous local governance of Manobo tribes in Mindanao. Phil J Pub Adm. 2004;48:125.

ILO. The road to empowerment: strengthening the indigenous peoples rights act. Vol. 1: New ways, old challenges. Manila, International Labour Office; 2007.

Opeña LR, Taguchi AS. Bukidnon folk literature. In Dialogue for development. Edited by Francisco R. Demetrio. Cagayan de Oro: Xavier University; 1975.

Dapar MLD, Demayo CG. Folk medical uses of Lunas Lunasia amara Blanco by the Manobo people, traditional healers and residents of Agusan del Sur, Philippines. Sci Int (Lahore). 2017;29:823–6.

Herbert P, Cywinska A, Ball S. Biological identifications through DNA barcodes. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences. 2003;270:313–21. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2002.2218 .

Newmaster SG, Grguric M, Shanmughanandhan D, Ramalingam S, Ragupathy S. DNA barcoding detects contamination and substitution in North American herbal products. BMC Med. 2013;11:222. https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-11-222 .

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Buddhachat K, Osathanunkul M, Madesis P, Chomdej S, Ongchai S. Authenticity analyses of Phyllanthus amarus using barcoding coupled with HRM analysis to control its quality for medicinal plant product. Gene. 2015;573:84–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gene.2015.07.046 .

Cabelin VLD, Santor PJS, Alejandro GJD. Evaluation of DNA barcoding efficiency of cpDNA barcodes in selected Philippine Leea L. (Vitaceae). Bot Lett.: Acta Botanica Gallica; 2015. https://doi.org/10.1080/12538078.2015.1092393 .

Vassou SL, Kusuma G, Parani M. DNA barcoding for species identification from dried and powdered plant parts: a case study with authentication of the raw drug market samples of Sida cordifolia . Gene. 2015;559:86–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gene.2015.01.025 .

Cabelin VLD, Alejandro GJD. Efficiency of mat K, rbc L, trn H- psb A, and trn L-F (cpDNA) to molecularly authenticate Philippine ethnomedicinal Apocynaceae through DNA barcoding. Pharmacogn Mag. 2016;12 10.4103%2F0973-1296.185780 .

Olivar JE, Alaba JPE, Atienza JF, Tan JJ, Umali M, Alejandro GJD. Establishment of standard reference material (SRM) herbal DNA barcode library of Vitex negundo L. (lagundi) for quality control measures. Food Addit Contam Part A. 2016;33:741–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/19440049.2016.1166525 .

Ghorbani A, Saeedi Y, de Boer HJ. Unidentifiable by morphology: DNA barcoding of plant material in local markets in Iran. PLoS One. 2017;12. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal . pone.0175722.

Alfeche NKG, Binag SDA, Medecilo MMP, Alejandro GJD. Standard reference material (SRM) DNA barcode library approach for authenticating Antidesma bunius (L.) Spreng. (bignay) derived herbal medicinal products. Food Addit Contam Part A. 2019;1–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/19440049.2019.1670868 .

Prance GT, Baleé W, Boom BM, Carneiro RL. Quantitative ethnobotany and the case for conservation in Amazonia. Conserv Biol. 1987;1:296–310. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1739.1987.tb00050.x .

Phillips O, Gentry AH. The useful plants of Tambopata, Peru: I. statistical hypotheses tests with a new quantitative technique. Econ Bot. 1993;47:15–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02862203 .

Reyes-García V, Huanca T, Vadez V, Leonard W, Wilkie D. Cultural, practical, and economic value of wild plants: a quantitative study in the Bolivian Amazon. Econ Bot. 2006;60:62–74. https://doi.org/10.1663/0013-0001 (2006)60[62:CPAEVO]2.0.CO;2.

Tardio J, Pardo-de-Santayana M. Cultural importance indices: a comparative analysis based on the useful wild plants of Southern Cantabria (Northern Spain). Econ Bot. 2008;62:24–39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12231-007-9004-5 .

Bussmann RW, Paniagua Zambrana NY, Sikharulidze S, Kikvidze Z, Kikodze D, Tchelidze D, Khutsishvili M, Batsatsashvili K, Hart RE. A comparative ethnobotany of Khevsureti, Samtskhe-Javakheti, Tusheti, Svaneti, and Racha-Lechkhumi, Republic of Georgia (Sakartvelo). Caucasus. J. Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2016;12:43. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13002-016-0110-2 .

PENRO. Agusan del Sur. 2018. http://www.denrpenroads.com/index.php/about/background . Accessed 20 Aug 2019.

Chase MW, Hills HH. Silica gel: an ideal material for preservation of leaf samples for DNA studies. Taxon. 1991;40:215–20. https://doi.org/10.2307/1222975 .

Madulid DA. A dictionary of Philippines plant names. Vol. I: local name- scientific name. Vol. II: scientific name-local name. Makati City, Bookmark; 2001.

The Plant List. Version 1.1. 2013. http://www.theplantlist.org/ . Accessed 26 Oct 2019.

WFO. World Flora Online. 2019. http://www.worldfloraonline.org . Accessed 27 Oct 2019.

IPNI. The International Plant Names Index. 2019. https://www.ipni.org . Accessed 25 Oct 2019.

Tropicos, 2019. Missouri Botanical Garden. 2019. http://www.tropicos.org . Accessed 24 Oct 2019.

CDFP; Pelser PB, Barcelona JF, Nickrent DL. Co's digital flora of the Philippines. 2011 onwards. www.philippineplants.org . Accessed 28 Oct 2019.

Alejandro GD, Razafimandimbison SG, Liede-Schumann S. Polyphyly of Mussaenda inferred from ITS and trn T-F data and its implication for generic limits in Mussaendeae (Rubiaceae). Am J Bot. 2005;92:544–57. https://doi.org/10.3732/ajb.92.3.544 .

White TJ, Bruns T, Lee S, Taylor J. Amplification and sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In: Innis M, Gelfand D, Sninsky J, White T, editors. PCR Protocols: a guide to methods and applications. San Diego.: Academic Press; 1990. p. 315–22.

CBOL Plant Working Group. A DNA barcode for land plants. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106:12794–12797. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0905845106 .

Kress WJ, Wurdack K, Zimmer E, Weight L, Janzen D. Use of DNA barcodes to identify flowering plants. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:8369–74. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0503123102 .

Taberlet P, Gielly L, Pautou G, Bouvet J. Universal primers for amplification of three non-coding regions of chloroplast DNA. Plant Mol Biol. 1991;17:1105–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00037152 .

McGinnis S, Madden T. BLAST: at the core of a powerful and diverse set of sequence analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkh435 .

Techen N, Parveen I, Pan Z, Khan IA. DNA barcoding of medicinal plant material for identification. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2014;25:103–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copbio.2013.09.010 .

Amiguet VT, Arnason JT, Maquin P, Cal V, Vindas PS, Poveda L. A consensus ethnobotany of the Q'eqchi’ Maya of southern Belize. Econ Bot. 2005;59:29–42. https://doi.org/10.1663/0013-0001(2005)059[0029:ACEOTQ]2.0.CO;2 .