- Open access

- Published: 06 April 2020

Environmental rehabilitation of damaged land

- Mike Mentis 1

Forest Ecosystems volume 7 , Article number: 19 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

27k Accesses

18 Citations

3 Altmetric

Metrics details

Much land is subject to damage by construction, development and exploitation with consequent loss of environmental function and services. How might the loss be recovered?

This article develops principles of environmental rehabilitation. Key issues include the following. Rehabilitation means restoring the previous condition. Whether or not to restore is not a technical but a value judgement. It is subject to adopting the sustainability ethic. If the ethic is followed under rule of law then rehabilitation must be done always to ‘the high standard’ which means handing down unimpaired environmental function and no extra land management. The elements of the former condition that it is intended to restore must be specified. Restoring these in any given case is the purpose of that rehabilitation project. The specified restoration elements must be easily measurable with a few simple powerful metrics. Some land damage is not fixable so restraint must be exercised in what construction, development and exploitation are permitted. If sustainability is adopted then cost benefit analysis is not a valid form of project appraisal because trading off present benefits against future losses relies on subjectively decided discount rates, and because natural capital is hard to price, indispensable, irreplaceable and non-substitutable. Elements often to be restored include agricultural land capability, landscape form and environmental function. Land capability is a widely used convention and, with landscape form, encapsulate many key land factors, and are easily measurable. Restoring soil and thereby environmental function provides the necessary base for an ecological pyramid.

Conclusions

The need for rehabilitation is not to be justified by cost-benefit or scientific and technological proof, but rests on a value judgement to sustain natural capital for present and future generations. Decision on what activities and projects to permit should be based on what is physically and financially fixable on current knowledge. Business and government must be proactive, develop rehabilitation standards, work out how to meet the standards, design simple powerful metrics to measure performance against the standards, embark on continuous improvement, and report.

Introduction

This article addresses key issues in environmental rehabilitation of land damaged by construction, development and exploitation, based on experience in a developing country, South Africa.

Most of the earth’s land surface has been subject to anthropogenic impact with consequent loss of environmental function and services. Damage can happen at the local, landscape or regional scales by any of many activities including cultivation of dryland or irrigated annual or perennial crops, industrialization, mining, pastoralism, recreation, other resource exploitation, and urbanization. There can be various effects including biodiversity loss, biocide or heavy metal or radionuclide contamination, damage to soil (acidification, compaction, puddling, salinization and sodification), disruption of environmental processes and services such as nutrient cycling and hydrological regime, erosion, eutrophication, land capability loss, landscape destabilization, nutrient impoverishment, overgrazing, and soil organic carbon loss. Environmental rehabilitation means to restore the former condition, and it seeks to reverse the kinds of ill-effects mentioned above. Rehabilitation and restoration are synonymous, and in the environmental management hierarchy of avoid, mitigate, offset, transfer, insure, accept and prepare (Mentis 2015 ) they correspond closest with mitigate. Mentis ( 2015 ) discussed the pros and cons of the elements of the hierarchy. In the context of this article, if the mitigation cannot be done to a high standard then the activity should be avoided. As mentioned below, in cases the damage is already done and more or less irreparable. Where damage is irreparable, offset (investment in protecting or restoring other resources of equivalent type or ecosystem function or value) is a much-vaunted option. The reality though is a risk that project proponents use the offset option as an escape to permit doing irreparable damage. Offset needs economies of scale and can be costly and even non-feasible where replacement resources are in many isolated small patches under different ownership (Mentis 2015 ).

This article addresses big questions. Should rehabilitation be undertaken in the first place? If so, to what standard? On what should rehabilitation focus? Though this author’s primary experience is not in forest per se, but in steppe and savanna a large proportion of which has a climatic climax potential of forest or scrub, the nature of the questions transcends bioclimatic region.

The approach here is in the form of ‘lessons learnt’. For a lesson to be learnt it is not enough that a goal was achieved. In such event, what was learnt? That the method was correct? This is not necessarily so. Success can arise by chance, and it is possible to be ‘fooled by randomness’ (Taleb 2001 ). Usually it takes failure to prompt questions. Typically we set out in Kahneman’s ( 2011 ) automatic thinking mode without much insight, and it is only if and when things go awry that we switch to the deep-thinking, deliberate and effortful mode. Why did the technique disappoint or fail? What were the underlying assumptions with which we started? What was flawed about the assumptions? What new assumptions have we now adopted that, so far, have avoided failure? Even though the revised assumptions and technique now work, it does not necessarily follow that our understanding is correct. In the mindset of Drucker ( 1967 ), a ‘decision’ works until it meets challenges outside of which it was designed. No lesson, let alone starting point, is uncorrectable. Lessons learnt are transient knowledge.

It was in terms of this paradigm of evolving knowledge that the lessons of this article to understand rehabilitation were conceived. On a range of rehabilitation issues the naif’s initial viewpoints are stated below. A naif is an inexperienced person, having a naïve view of things. Here naif is the author. Mostly he set out without interrogating the assumptions of his starting positions, or even being aware of them, and it was only after challenges, disappointment and failure that he asked ‘why am I doing it this way?’ The lessons – the initial viewpoints, their shortcomings, and the revised positions – were not learnt in sequence. Rather, the learning was sporadic across all the lessons. But lessons were interrelated and advance on one did promote learning on others. This took place during 50 years working on conservation, mining, pipeline, powerline, rangeland, road and water storage and supply projects in southern Africa. Naif set out with unquestioned convention or ignorance, the rare insightful publications (Bell 2002 , 2013 ; Macdonald et al. 2015 ) were belated, and learning was experiential. To be sure, rehabilitation know-how has been compiled (e.g. Tanner and Möhr-Swart 2007 ; De Klerk and Claasen 2015 ; Hatting et al. 2019 ), and South African law now requires projects in the mining industry to make financial provision for rehabilitation. However, the compilations are collections of techniques rather than syntheses into integrated ‘ecosystems’ with interactive and interdependent parts. The compilations do not provide a handful of easy-to-measure simple powerful metrics the application of which might index the standard of rehabilitation. Similarly, the law is short on rehabilitation standards on which financial provisioning might be estimated, and on which the adequacy of rehabilitation can be decided. These shortcomings are long-standing and widespread, and recognition of them motivated this author, his decades of work on developing measurable standards, his recent book (Mentis 2019 ), and this article.

Lesson 1 – cost benefit analysis

Should rehabilitation be undertaken? Naif’s first position was to answer the question by cost-benefit analysis (CBA), on the rationale of maximizing return on investment. If the rehabilitation cost was more than the benefits that accrued from doing it, then rehabilitation was not justified, and the funds should be invested in other opportunities that yielded a higher return. This was conceived in a static view of fixed technology, products, processes and consumer demands with ever stricter regulation (Porter and van der Linde 1998 ). Over time the static view gave way to a dynamic one involving innovation (Lesson 9). However, before that fundamental problems emerged with CBA in the context of rehabilitation projects. First, long time spans are involved. Rehabilitation is ‘forever’, which means discounting supposedly should be applied. Yet there is no definitive answer to what discount rate to use. If a high discount is applied then guarantee on the wellbeing of future generations is foreclosed. Even at a low discount rate, long-term survival is in question. If discounting were the only problem, CBA might nevertheless be useful. However, a second serious flaw relates to the nature of the assets involved. In conventional use of CBA things like labour and machinery are interchangeable. If it is cheap and plentiful, use manual labour to build the bridge, otherwise use machinery. By comparison, there are no substitutes for environmental processes such as nutrient cycling, photosynthesis, succession and the weather. Natural capital is indispensable and irreplaceable. This means that even a slow rate of environmental loss cannot be tolerated for long without impairing biospheric function whatever the worth of the immediate benefits and costs of avoiding and remedying any ill-effects. Third, natural capital does not change hands between willing buyer and willing seller. There is no explicit market value for the assets. Prices must be imputed. Discussion of discounting, pricing and sustainability in environmental contexts can be found in, for example, (Pearce et al. 1989 ), Farber and Hemmersbaugh ( 1993 ) and Martinez-Paz et al. ( 2016 ). It may be that project planning can be informed by CBA despite its shortcomings, but plainly CBA can be adjusted to support preconceptions.

Lesson 1 therefore is that CBA cannot be relied on for an objective answer to whether or not to rehabilitate. An alternative and hopefully more definitive decision criterion than cost-benefit is needed.

Lesson 2 – value neutrality of science and technology

To a naïve environmentalist the answer to whether or not to rehabilitate is ‘obviously yes’. He observes that Nature’s self-healing powers are insufficient to quickly remedy the degradation caused by many projects, and unless environmental damage is avoided in the first instance, rehabilitation is necessary if environmental services are to be preserved. Though details might be debated, the technicalities and truth of this are beyond dispute. Yet technical statements, sound as they might be, are silent on the desirability of, say, short-term employment and economic development at the cost of, say, loss of topsoil and curtailed future land productivity. In general, normative arguments (how the world should be) are not derivable from positive statements (how the world is) (attributed to Scottish philosopher David Hume 1711–1776).

Implicit in the naïve environmentalist’s ‘obviously yes’ answer is adoption of the sustainability or similar ethic. Adopting such an ethic is not a technical but a value judgement. The ethic is not in conflict with our technical understanding of the biosphere, but it is not a necessary consequence of that understanding unless or until value is attached to the wellbeing of present and future generations. If the ethic is not adopted nationally, and not enforced, then organizations that disregard detrimental environmental externalities must, at least, erode natural capital or, more likely, average out competitively superior and come to dominate in the market place, with consequent run-down of environmental function. If the ethic is to take effect then an ultimate frame of reference is needed to guide law and action so as to prevent environmentally degrading effects of activities being externalized.

An example of the kind of ultimate frame of reference needed is given in Table 1 in which relevant extracts from the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa are presented. In this article repeated resort to the South African situation is made, not with any pretence that it is the model case, or that it is not paralleled at least to an extent elsewhere (Bell 2002 and 2013 ; Macdonald et al. 2015 ), but because it helps illustrate the issues involved.

In South Africa any activity causing ecological degradation, if not prevented in the first instance, requires rehabilitation. This is so in terms of the Constitution (Table 1 ). Sections of enabling law support it. For example both the National Environmental Management Act and the National Water Act contain clauses on duty of care holding anyone who causes, has caused, or will cause pollution or environmental damage accountable. There is now precedent for enforcement of this in case law (Harmony Gold Company Ltd. vs Regional Director: Department of Water Affairs 2013 ZASCA). A miner sold his mine. The buyer ‘disappeared’. The original mine owner was judged responsible for the unrehabilitated mine works. Further, it is also often a condition of environmental authorization of a project to rehabilitate. The answer therefore to any question in South Africa about ‘should I rehabilitate?’ is unambiguously ‘yes’. This answer is not a necessary consequence of positive knowledge (how the world is) but rests on a normative frame of reference (in South Africa this is the Constitution and supporting laws).

In other situations and countries there might not be an effective Constitution or equivalent ultimate frame of reference. In these cases there is a variety of options to choose from: e.g. Agenda 21 (output from the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro in June 1992, the standards set by the Environmental Protection Agency of the United States, the procedures of the environmental directives of the European Union, World Bank protocols, the environmental and social performance standards of the International Finance Corporation, the Equator Principles, the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) or some combination of these. In South Africa such other documents could only be additive for if they conflict with the Constitution they are invalid. In the absence of an obvious frame of reference, the stakeholders should agree on a frame of their own before embarking on projects and their rehabilitation. A merit of a suitably worded Constitution and supportive regulation is that rehabilitation then has the force of law behind it. This law is necessary to discipline the reluctant rehabilitator. The progressive business will use the law and other documents to devise its appetite for risk in a policy that commits the organization to relevant societal values (Mentis 2019 ).

Lesson 2 therefore was that ‘The guidance we seek for this work cannot be found in science or technology, the value of which utterly depends on the ends they serve, but it can still be found in the traditional wisdom of mankind’ (Schumacher 1973 ).

Lesson 3 – rehabilitation standard

The naïve position was that the standard to which rehabilitation should be done depended on such factors as the nature of the degradation, the future intended land-use, and the affordability of the rehabilitation exercise.

Contrary to naif’s original position, a variable standard for rehabilitation is not realistic, and rather rehabilitation must always be to one and the same high standard, for the following interrelated reasons. First, rehabilitation is mandatory (in South Africa), as already explained. Second, it is easier to apply a law or principle always rather than only sometimes, e.g. 100% rather than 98% of the time. If exceptions to applying the rule are allowed, further rules are required to define when exceptions are allowed. Then possibly exceptions to the exceptions will be required, and so on. This raises a third reason, namely the Constitutional provisions (in South Africa) for equality before the law and the right to lawful, reasonable and procedurally fair administration (Table 1 ). If an exception to effective rehabilitation is allowed in one instance, why not in another, even for different reasons? And how are exceptions administered lawfully, reasonably and fairly? Plainly any exception risks flouting the Constitution and running down natural capital. A fourth reason is that if partial rather than full rehabilitation occurs on whatever lawful or unlawful basis, even only on occasions, then cumulative loss of environmental structure and function is inevitable.

Turning to the future land use, several different shortcomings and oversights can arise. There can be an inclination to downscale the post-rehabilitation required land capability from, say, a pre-mining arable potential to grazing land capability because of the difficulty of reinstating arable land. Often in opencast mining the top 1.5 to 2 m of soil is stripped off and all regarded, and stockpiled, as topsoil. Proper topsoil is usually only about 0.3 m deep, so that when the 1.5 to 2 m of scrambled topsoil and subsoil is emplaced on the new landscape the proper topsoil is so diluted that ‘topsoiling’ is done with subsoil comprising, for example, stone, saprolite, pedocrete and acid materials which are low in soil organic carbon and high in manganese and iron concretions that have a propensity to fix phosphate so it is not available to plants. Arable land capability criteria are then not met. Reinstating to arable land is indeed challenging, but tractor-drawn pull-scrapers can be used to enable stripping of topsoil to be done more clinically than is current common practice. The per capita availability of high potential land is so scarce in some parts of the world, like South Africa, that no loss of arable land is affordable, and applicants for projects on arable land should be required to reinstate to arable, or project authorization refused. In terms of sustainability, pre-project arable or other high-quality land should be restored post-project to arable or similar high-quality land irrespective that the immediate or foreseeable intended future land use does not demand high land capability. The future is uncertain and a principle of sustainability is that unimpaired environmental potential be handed on not least because it is not known how land will need to be used in the future. In effect, it is not the intended, and uncertain, future land use that is of focal concern, but the pre-existing land capability which must be restored – a standard that can be hard to meet but is capable of consistent application. This position conflicts which much of the literature (Bell 2002 and 2013 ; Tanner and Möhr-Swart 2007 ; de Klerk and Claasen 2015 ; Hatting et al. 2019 ) where the intended land use looms large.

There are other cases, analogous to high potential land, of scarce, rare and endangered or valuable resources put at risk by projects and difficult to reinstate. Examples include wetlands, biodiversity and even common, but prized, native pasture grasses such as red grass ( Themeda triandra ).

Seemingly simple activities, such as construction of buried fuel, gas and water pipelines, can have surprising effects. A pipeline down a hillside can destroy a hillslope seep wetland, because an impermeable layer is punctured, or because the back-filled trench is insufficiently compacted, is more permeable than the adjoining undisturbed soil, and acts as a conduit draining the wetland. On land with low relief, and sandy topsoil over clayey subsoil, pipeline construction can transform upslope land from arable or forest capability to wetland where cropping or afforestation are no longer possible. With the pipeline laid at the bottom of the trench, using the sandy topsoil as bedding material, and back-filling with the clayey subsoil, the whole acts as an underground dam impeding subsurface water flow. Understanding the structure, and in particular the hydrological functioning, of the landscape helps to design the project and to guide reinstatement so the original condition is restored and land degradation avoided.

Former biodiversity can be challenging to restore. Typically after disturbance a bare, hostile site exists, with no or few species present. By process of secondary succession conditions ameliorate, colonization by species from near and far occurs, there is gradual accretion in species richness, and ecosystem structure and function develop. Secondary succession can span decades or centuries. This is expected with forests, though in cases the projected restoration of climax species richness and composition can be less than 70 years (Mentis and Ellery 1998 ). Of course, projections can fail, for example because species with limited propagule dispersal might take a long time to colonize. ‘Islands’ of native vegetation left undisturbed in a ‘sea’ of disturbed area can facilitate recovery of species richness and composition (Macdonald et al. 2015 ). These principles would be expected to apply not just to forests but to all vegetation types. Secondary succession in savanna and steppe might be expected to be quicker than for forest. However, in the humid and semi-arid grasslands of southern Africa recovery can also span decades. After 50 years the routes of buried fuel and water pipelines are easily detectable from space by satellite imagery and at close quarters from soil texture, low soil organic carbon and phosphate, and sparse and weedy or seral composition of the herb layer (Mentis 2006 , 2019 ). Climax grass species, such as red grass, are notorious for their tardiness to return after they have been lost by overgrazing or ploughing or other land disturbance.

On the one hand it might be expected that there are limits to speeding up natural process, such as succession. Research on old field succession found that succession was accelerated by application of fertilizer (Davidson 1964 ; Roux 1969 ). My own observations are that with infertile soil, especially scarcity of soil phosphate, only a few pioneer species survive, plants remain small and sparse, and there is no increase in soil organic carbon for 20 years and more. This contrasts with the fertile situation with vigorous plants, dense cover and increasing soil organic carbon and species richness. Macdonald et al. ( 2015 ) pointed to a variety of site conditions in forest rehabilitation after surface mining that can impede colonization, including soil fertility, soil texture, substrate layering, soil moisture, and types of soil organic matter. Bell ( 2013 ) described a range of soil conditions that can constrain plant establishment, performance and survival.

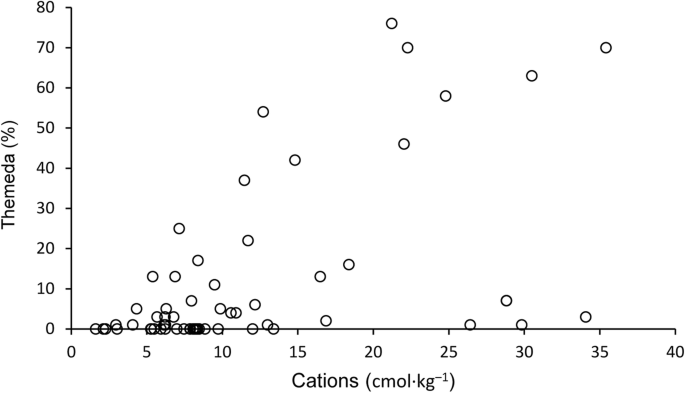

Many attempts have been made to restore red grass, with inconsistent results (Snyman et al. 2013 ). On some pipeline projects red grass grown in nurseries was planted out, but mostly the red grass died out. On Transnet’s New Multi Products Pipeline from Durban to Gauteng, natural recovery of red grass after 6 years was a function of soil base status (percentage red grass = − 4.71 + 1.43 cations in cmol·kg − 1 , n = 61, R 2 = 0.33, P < 0.0001)(Fig. 1 ). Since red grass does not always recover quickly on base-rich soils, but always recovers slowly on base-poor soils, it is inferred that high base status is a necessary but insufficient condition for fast red grass recovery. Macdonald et al. ( 2015 ) explained that the species composition of the establishment biota in forest areas subjected to surface mining is affected by site conditions including topography, drainage and surface roughness in addition to the factors mentioned in the previous paragraph. To promote forest biodiversity Macdonald et al. ( 2015 ) advised that a variable rather than uniform terrain be constructed during landscaping the surface mining disturbance.

Recovery of red grass (percentage of sward composition) as a function of soil base status (cations in cmol·kg −1 )

On the other hand, but still in the context of natural process taking time, attempted restoration of biodiversity and climax species can be premature, for example if soil function has not been re-established. As already mentioned, in severely dystrophic situations soil organic carbon does not increase and species do not accrete. Soil organic carbon is generally regarded as an indicator of soil function, and can be an important factor in nutrient supply and nutrient cycling, especially in coarse-textured soils (Murphy 2014 ; Macdonald et al. 2015 ). After coal mining on the Eastern Highveld of South Africa, replaced soil has a typical soil organic carbon content of 0.5%, while unmined topland soils have about 2% carbon. The rate of carbon replenishment is slow. In a regression analysis using data from 23 fertilized sites, the percentage of carbon was a significant function ( P < 0.0001) of management intensity (rated on 5–4–3-2-1 basis with two applications of nitrogen fertilizer and two defoliations per summer scoring 5, and no nitrogen and no defoliation scoring 1, R 2 = 0.1239) and pasture age (years since establishment, R 2 = 0.1718), viz.

Macdonald et al. ( 2015 ) reported similarly slow rates of accretion of soil organic matter after surface mining in forest areas.

Regarding affordability, to the reluctant rehabilitator any rehabilitation is unaffordable. But if unaffordability is truly the case then the project should be redesigned and if rehabilitation is still unaffordable then project authorization withheld. There might still be cases, for example old projects for which rehabilitation was not contemplated at the outset, where the land users do not have the means to undertake the necessary rehabilitation. Other common instances are where miners have gone insolvent or disappeared leaving unrehabilitated mine works. Outside intervention would then be warranted, probably at taxpayer’s or donor’s expense. Affordability per se should not affect the standard to which rehabilitation should be done, only how it is supported.

Naif’s Lesson 3 then is that the standard to which rehabilitation should be done is better not conditional to this or that, but always be to the same standard which, if it is to be consistent, is to restore it as it was, i.e. to ‘the high standard’ (see below). Any leniency risks flouting equality before the law, and is on a slippery slope to biospheric ruin. In the case of new projects, it is either rehabilitate to the high standard or the project is not authorized. For existing and completed projects where affordability is in question, the high standard of rehabilitation should not be relaxed, and the party responsible held accountable, otherwise there is a legal loophole for reluctant rehabilitators. Application of rehabilitation to the high standard must be tempered with the fact that natural processes (e.g. succession, restoration of soil function) can be hurried along only within limits. However, the state of process can be monitored, e.g. the replenishment of soil organic carbon, as an index of soil function, can be measured.

Lesson 4 – sustainability

Rehabilitation is supposedly ‘forever’, or a permanent fix that is ‘sustainable’. What might sustainable rehabilitation mean? Naif always had a problem with early definitions of sustainability, such as that of the Brundtland Commission. This defined sustainable development as meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs (World Commission on Environment and Development 1987 ). There are several difficulties. First, there are two objective functions – meeting present needs and not compromising the future. These objectives are liable to conflict. Just about any environmental controls, to protect the future, might be interpreted to mean less immediate profit and therefore not meet present needs. Any attempted trade-off here faces the problems already raised on CBA. Second, the needs and the wants of future generations are uncertain. Third, operational guidance is not offered on how to proceed. Since the Brundtland Commission, ‘sustainable’ has become a clichéd word often invoking dubious trading off, discounting, pricing, substitution, maximization and optimization, or it is used without its meaning defined.

Lesson 4 was therefore not to rely on clichéd ‘sustainability’, but to define the necessary foreverness of rehabilitation in operational terms. For example, rehabilitation to ‘the high standard’ means restoring the environment so that it looks and functions as it previously did, without passing on to posterity any maintenance or land management more than is needed for adjoining similar but undisturbed land. ‘Sustainability’ is defined in operational terms by Macdonald et al. ( 2015 ) as ‘ … reclaimed forest is productive and self-sustaining and if it fulfills ecological, economic and social objectives’.

Lesson 5 – rehabilitation criteria

In the context of Lesson 4 the question arises as to whether it is possible to restore it the same as it was. It is improbable that any two spots on earth, or any spot at different times, are exactly the same. There is nearly an infinity of parameters, the earth and the universe are ‘evolving’ irreversibly, and Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle imposes limits to measuring and knowing. To ‘put it back the same as it was’ requires the key criteria of ‘the same’ to be specified. These key criteria are not everything, not all conceivable parameters, but a select few variables relevant to the particular application and measurable within the resource constraints of budget, expertise and time.

Lesson 5 was to identify a select few rehabilitation variables and work out how to measure and report them efficiently. At the outset it was unclear what constituted good rehabilitation and how it might be distinguished from poor rehabilitation. Naif had to observe, try out ideas, collect data, analyze and develop a perspective (Mentis 1999 , 2006 , 2019 ), and he now proposes to his clients that rehabilitation might be approached as follows.

The objective is to minimize the cost of putting it back like it was subject to boundary conditions, for example as follows.

Land capability not less than p

Landscape form exceeds q

Soil loss does not exceed r

Soil fertility exceeds s

Species composition exceeds t

Vegetation structure exceeds u

Vegetation vigour exceeds v

where p , q , r , s , t , u and v are specifications defined by an exact computer algorithm. For example, if the land capability to be restored is ‘arable’, then the computer algorithm specifies the conditions of soil depth, land slope, etc. that must be met for the rehabilitation to be within the boundary conditions of ‘arable land capability’. Enter the site data into the computer and the algorithm consistently outputs an objective result – this meets, or does not meet, the land capability requirement.

The merits of this kind of approach include the following.

There is only one objective function. Maximizing, minimizing or optimizing two or more objective functions simultaneously is improbable, and potential complexity and conflict are avoided.

Minimizing the cost is an objective to which clients and project managers are favourably disposed. It aligns with the business purpose to maximize the wealth of the business owners. Of course such maximization is subject to health, safety, environmental and other constraints. The specifications of getting the rehabilitation done to the high standard are among these constraints on doing business, and they are spelled out exactly. The specifications bound or define what is the acceptable rehabilitation product. This is not a CBA problem involving questionable discounting and pricing of natural capital, but a matter of containing the cost to restore the environment to meet specifications.

Meeting specifications can be of the pass or fail type, or graded to index degree of conformance. This aids in identifying where failures or weaknesses lie, and is a key step in knowing what to fix and then working out how to fix it.

The specifications are partly a knowledge-base. They are accumulated experience. They are amenable to on-going research, revision, improvement and, important, adaptation to varying circumstances. The approach can be tailored to fit many of a variety of applications. The specifications are also partly a function of appetite for risk, a notion indexing how accepting or averse an organization is to attaining a particular performance level. The approach of Bell ( 2013 ) is analogous in that it identifies limiting factors or constraints on rehabilitation that would vary according to circumstances but that might be developed into the specifications suggested above. The same applies in the case of Macdonald et al. ( 2015 ) who described landscape, site (soil) characteristics and management as determinants of rehabilitation outcomes such as productivity, biodiversity and meeting ecological, economic and social requirements.

The objective function and its boundary conditions do not cover everything about the environment. It is not possible to measure, let alone restore, ‘everything’. The resources of budget, manpower and time are finite, so if the objective function and constraints are made ‘comprehensive’ it is likely that the project will be complicated, demanding on resources, therefore costly to implement, and liable not to be continued or even put into effect at all. Partial knowledge is better than no knowledge. Partial knowledge, focused on key performance indicators, is better still. There is a need for simple powerful metrics (Lesson 6).

Lesson 5, learning about rehabilitation criteria, turned out, after resolving the issue of ultimate frame of reference, central to the rehabilitation paradigm. A few key indicators are needed. It is not possible to consider ‘everything’. The selected indicators must be easy to measure and tell a lot. Not only must they individually home in on the fundamental features of landscapes and ecosystems, but their framework must be generic, flexible and scalable. Projects vary in scope and context, and it is useful to have an approach that can be scaled up for rehabilitating massive disturbance such as opencast mining, or scaled down to address simple projects such as buried pipelines that stretch for hundreds of kilometers, and across different bioclimatic regions and scores of properties. The suite of appropriate rehabilitation criteria might also need to change over project lifetime. Initially on rehabilitating opencast mines, focus is on restoring land capability, landscape and environmental function. Ten or 20 years later other indicators – such as biodiversity, certain valued species such as red grass, or crop production – might be more relevant. The indicators must be capable of consistent measurement or rating, so performance against standards can be assessed, shortcomings identified and progress determined. Simple quantification permits development of a relational knowledge so that, for example, if a minimum soil fertility is not met, revegetation will fail to meet a specified standard, or soil organic carbon will not accrete, or if a threshold vegetation structure is not met within 2 years then establishment has failed and must be repeated, and so on.

Lesson 6 – measurement

Naif’s starting position on measurement was that of conventional science. The facts must be obtained by repeatable methods. However, in parallel with developing rehabilitation criteria, the metrics became more than just measurement in environmental and social sciences. They were necessary tools for project management. The business adage applied: if you don’t measure you can’t manage and improve. Measured and reported often, metrics informed stakeholders on whether the rehabilitation standards were met, what variances there were, where corrections were necessary, and for what satisfactorily completed work a contractor was to be compensated.

A further naïve view was scientific description and measurement were whatever it took. However, the more complex and costly a technique is the less likely it will be continued over time. Decision-makers are reluctant to fund exercises that are difficult to execute, people do not understand and the utility of which is not obvious. To paraphrase Schumacher ( 1973 ), any idiot can design a complex technique but it takes thought and application to make it into Einstein’s ‘ … simple, but not too simple’.

Adopting an objective function and boundary conditions, and resorting to simple metrics, enables construction of industry performance and a basis for benchmarking. For example, for naif’s coal mining clients, rehabilitation performance on the seven criteria (boundary conditions) is rated on a 5–4–3-2-1 scale. There are of course limitations to manipulating ordinal data, such as these ratings. To try to make scales on the seven criteria comparable the following were applied across all criteria: 5 means ‘best’ (beyond criticism), 4 is ‘good’ (not perfect), 3 is ‘fair’ (bordering on non-sustainable), 2 is ‘unsatisfactory’ (not sustainable – passes on costs or diminished environmental services to posterity) and 1 means ‘very unsatisfactory’ (little or no effective effort to ameliorate). To illustrate, for rating soil loss let the rate of soil genesis be to the order of 1 t·ha − 1 ·a − 1 , so in assessments modelled rate of soil loss < 2 t·ha − 1 ·a − 1 rates 5 (best), 2–4 t·ha − 1 ·a − 1 rates 4 (good), 4–8 t·ha − 1 ·a − 1 rates 3 (fair), 8–12 t·ha − 1 ·a − 1 rates unsatisfactory (2), and > 12 t·ha − 1 ·a − 1 rates 1 (very unsatisfactory).

Rehabilitation performance at a colliery can then be determined by assessing all seven criteria at several to many sample sites, and by calculating a mean score over all criteria for each colliery at each assessment. Figure 2 shows the frequency distribution of colliery mean scores for 215 assessments undertaken since 2000. Taking this kind of approach, it is possible to make comparisons within times between collieries, and between times within collieries. An individual colliery can be tracked over time, and so can the industry as a whole. Possibly the data are not representative and it is only the most go-ahead companies that subject themselves to outside scrutiny. It might be expected then that the true industry average performance is worse than Fig. 2 shows. There can be other factors that affect performance assessment. First is subjectivity in collecting and using data. One way to limit this problem is to use unambiguously definable parameters for each criterion. For example, land capability uses the methods of agricultural land capability assessment that operate on the basis of constraints involving factors such as soil depth and land slope. The field data sheet must require categorical or numerical data that are easy to determine accurately and repeatably. The data interpretation (scoring against the standards) is best done by an exact computer algorithm, for example using if-then-else logic. This takes the tedium out of scoring, helps with consistency, and preserves mental energy for addressing exceptions. Inevitably a computer algorithm is built on common circumstances, and it is necessary to have an experienced user to check the output and apply his expertise to the unusual situations.

Colliery rehabilitation performance since 2000 ( n = 215, mean = 3.42)

Another factor affecting rehabilitation performance assessment is the evolution of the method over time. As mentioned earlier, the boundary conditions that go along with the rehabilitation objective are, and must be, subject to change, updating and improvement. In the case of data for Fig. 2 , scoring of performance has become more objective with formalization into a computer algorithm. Also, the scoring has become stricter. A future improvement is to shift from scoring colliery performance using the average over all sample sites and all criteria to using the average minimum criterion score for all the sites. In the spirit of rehabilitation to the high standard, a site should perform well on all criteria. By analogy, a chain is only as strong as its weakest link. For example, it is poor rehabilitation to perform well on land capability and landscape form, yet be defective on environmental function.

Lesson 6 was therefore about the power of simple metrics. There is a nest of interrelated requirements – simple, understandable, informative, workable, objective, consistent, reliable, economic, credible to the stakeholders, formalized into exact algorithms, and enable benchmarking. If-then-else logic, available for example in Microsoft’s Excel, handles quantitative and qualitative logic. It encodes knowledge in exact and testable, thereby improvable, form. If a decision turns out wrong, there is a decision trail. Is there a failure in understanding? Is there a computer programming error? Was there a mistake in data entry? Knowledge workers believe that exact algorithms, while with shortcomings, perform better than experts (Kahneman et al. 2016 ). The expert, or the algorithm, alone are useful, but a good model with seasoned expertise is a powerful combination.

Lesson 7 – rehabilitation design

At the outset, naif’s approach was to apply CBA and follow agricultural and soil conservation design with berms on steep slopes, delivering to waterways, and using drop weirs, gabions and reno mattresses and other structures to accommodate the new steep landscapes that were ‘too expensive’ to flatten to moderate gradients. Revegetation was driven by a vision to restore native biodiversity. Presently shortcomings arose. CBA was unworkable (Lesson 1). Structures on the new landscape often suffered from ill-design, they required maintenance (even when well designed), they frequently failed causing more soil erosion than they prevented, and they became long-term liabilities. Trying to install directly the native vegetation usually led to sparse weedy situations prone to soil erosion and alien invader plant colonization. The turning point in this dismal rehabilitation approach was to return to the ultimate purpose. Rehabilitation was not primarily to stop soil erosion and establish a native vegetation. At best, these were necessary but insufficient goals. The key issues were to reinstate land capability, a stable landscape and a functioning environment that delivered the same ecosystem opportunities and services as prior to disturbance, and that did not need any management or maintenance beyond that required for adjoining undisturbed equivalent land. This led to several key design criteria, as follows.

Begin with the end in mind. What must this project look like upon completion?

Design the new landscape as part of project planning.

Avoid a new landscape that requires conservation structures (berms, diversions, gabions, etc.), but if structures are needed design to be low-maintenance or maintenance-free.

Mimic the form of the pre-existing landscape in terms of slope and drainage density.

Reinstate the pre-existing runoff pattern, and design to avoid concentrating runoff and to disperse concentrated runoff.

Design for big events since rehabilitation is ostensibly ‘forever’, viz. bear in mind climate change and design for the 100-, 200- or 500-year rather than for the 10-year event.

Reinstate environmental function, using whatever are appropriate means, as a priority and as preparation for later native biodiversity restoration or crop species selection.

Macdonald et al. ( 2015 ), in their review of rehabilitation of surface mining in forest areas, presented a systematic design to rehabilitation on the basis that the new landscape, its profile across spatial scales and its substrate layering, strongly influence outcomes. Also, post-mining landscaping is now being aided by software modelling based on geomorphic principles to create natural looking and natural functioning landforms (Hancock et al. 2019 ). An example at La Plata mine in New Mexico can be viewed in Google Earth at N 36 o 59.5′ and W 108 o 8.2′.

CBA is a stumbling block in rehabilitation design. Not all environmental damage is fixable, or capable of rehabilitation at affordable cost. What then? Should long term environmental functionality be traded off against immediate profits, jobs and economic development? The inclination of business owners and politicians to do this is well known. However, CBA is not a valid means of deciding this, partly for reasons already considered, but also because of the requirement in South African law to make financial provision for future liabilities and then the difficulties of reliably estimating the liabilities. To explain this, suppose an opencast miner elects not to reduce his spoil piles to low gradients so that, while saving on immediate costs and increasing short-term profits, creates liabilities concerning the long-term integrity of the rehabilitation. Probably the lower the standard of the rehabilitation the bigger the liabilities and the greater the uncertainty in estimating them. The practical challenges of maintenance in the long-term are formidable. Who is going to do it? Who is going to check it is done properly? By Parkinson’s Law (Parkinson 1958 ), whatever the financial provision, it will likely not be sufficient. The reputation of the miner will be at risk, as might be assurance of renewal of his mining licence, approval of new mining licences, and good standing with banks and potential shareholders to fund present and possible future operations. A company could face potentially ruinous claims against it for pollution, damage to the environment, and losses to health and wellbeing. The way ahead is to limit uncertainties and liabilities by rehabilitating to the high standard.

Examples of ‘unfixable’ environmental degradation are the ‘big holes’ scattered across southern Africa (e.g. copper mine at Phalaborwa, diamond-mine big holes at Kimberley and elsewhere, and opencast coal mine final voids). Whether the big holes and adjoining spoil stockpiles are truly unfixable or simply costly to rehabilitate to the high standard, there is evidently no intention to restore the former landscape and its environmental structure and function. Possibly the agricultural land capability is low and the losses to environmental function and services are small in the case of some of these big holes. Yet a critical issue is the precedent created. If something short of rehabilitation to the high standard is to be permitted in one case, why not in others?

Since natural capital is indispensable and non-substitutable, there is no objectively determinable equivalence in number of jobs or amount of economic development. The upshot is that if a proposed project risks costly, unavoidable and unfixable environmental degradation then, on the sustainability ethic, the project should not be granted authorization. One objection to this strict stance is that, at the outset, the rehabilitation design to fix the damage might be unknown, yet given trial-and-error, and adaptive management, solutions might be developed. On these grounds, limited pilot trials might be justifiable. In principle though, if the degradation from a project cannot be avoided or fixed, then, if sustainability is accepted, authorization of the project must be withheld.

Initially naif was indifferent to land capability and the landscape form in the belief that they were not critical to arresting soil erosion and restoring native biodiversity or even just a vegetation cover. The erosion-protection methods of the ‘donga doctors’ and the green fingers of the revegetation experts were at hand. However, it turned out that neither soil protection nor vegetation establishment and maintenance could be assured without designing the new land within narrow bounds.

Starting with the landscape, it is convenient to view at three scales. At the macro scale the runoff pattern should mimic the pre-existing situation, the land should drain to the exterior, and hillslopes must have an even gradient or be concave, not convex, at the lower slope. For projects with limited impact on the landscape, e.g. buried pipelines, it is simple at most locations to restore the original landscape profile and thereby preserve the natural runoff pattern. However, for big-impact projects like opencast mining the new landscape is challenging to design. There is a bulking factor so the new landscape will be higher than the original. If the gradient to which the land is restored exceeds about 1 in 7 a tufted grass cover is insufficient to prevent soil erosion quickly destroying the new landscape. Plainly, factors such as soil erodibility and rainfall erosivity can affect the permissible steepness. It can also be difficult to vegetate steep slopes because erosion strips off topsoil, fertilizer and propagules before protective plant establishment occurs. The new landscape can also be put back with too little slope so that, with differential subsidence of back-filled spoils, there are soon hollows and internal drainage in the landscape, with ingress of rainwater into the old mine pit that can then fill and spill acid mine drainage to the surrounds. Big areas of new landscape also need to be designed with drainage lines. Without deliberate design, drainages will in any case appear and, given the fragmented nature of the back-fill, incise and initiate gully erosion in the new landscape. Erosion resistant barriers should therefore be installed in the designed drainages to provide a hard base to which landscape erosion works.

At the medium scale are conservation structures and terrain unevenness such as humps and hollows. As already explained, the problem with conservation structures is the entropy law. Structures will deteriorate and will require maintenance if they are to remain effective. The maintenance amounts to passing on costs to posterity which conflicts with the sustainability precept. Therefore, designing the new landscape must avoid the need for conservation structures, except for the hard barriers to protect the drainages discussed above. Humps and hollows that might arise because of insufficient landscaping, or because of differential subsidence of back-filled spoils, are undesirable. The humps drain quickly and soil in the hollows can remain saturated for extended periods, lowering land capability. There are various means of countering the humps and hollows. Back-fill can be compacted as it is emplaced. The new landscape can be left to settle for a few years before final smoothing and covering with topsoil. The new landscape should have sufficient slope on it so that even if differential subsidence occurs, surface drainage will nevertheless occur and ponding avoided.

At the fine scale there is surface roughness concerning stone on and in the soil, and other micro-relief factors such as rills, ruts and incomplete surface smoothing at landscaping and topsoiling. In the interests of most post-rehabilitation land-uses, smoothness at the fine scale is desirable. Most future land-users will want easy access across the rehabilitated landscape. Surface roughness reduces land capability, increases wear and tear on machinery, can be unsafe and injure livestock, and either raises the cost, or limits the benefits, of future land use. However, if the pre-disturbance landscape surface was rough then it is appropriate to restore it like that.

Restoring the landscape and land capability overlap but they are not synonymous. Landscaping deals with land form whereas land capability concerns the capacity of the land to support use without resource degradation. Landscaping specifications can be met yet land capability requirements not. For example, the land might drain externally, the lower hill slope might be concave, the slope might be modest so no conservation structures are needed, and the land might be smooth, yet the soil too shallow to qualify for the required, say, arable land capability. Similarly, the required land capability of, say, grazing might be met, yet landscaping standards not satisfied, for example because of internal drainage or convex footslope.

Agricultural land capability is an extensively researched convention. Land capability is determined by constraining factors such as land slope, soil depth, wetness and extremes of soil texture. The more the constraints the lower the land capability. The most constraining factor is operative so, for example, even though land might have low slope, if the soil is shallow the land capability will be low. Land that has no constraints (low slope, deep soil, well-drained, intermediate soil texture) has high capability (i.e. arable). As the constraints increase so the land capability reduces to pasture, grazing, forestry and wilderness capability. The categories may vary depending on the land capability classification system adopted. The logic of land capability rests on the conservation principle that land must never be used beyond its capability. For example, arable land may legitimately be used for grazing, but land of only grazing land capability should not be cropped if the resource base is to be preserved.

Irrespective of future land use, adoption of sustainability requires that the landscape and land capability be restored. Even though the immediate intended land use might be, say, grazing, sustainability requires the original land capability, say arable, to be restored so that an unimpaired environment is bequeathed to posterity. Restoring to arable land capability is challenging, and, so far, is rarely done.

Lesson 7 is that rehabilitation must be designed not on CBA but on producing a durable rehabilitation product that limits liabilities, i.e. rehabilitation to the high standard. Naif learnt that land capability and landscape form were not immaterial. They needed to be designed within narrow limits if sustainability was to be met. They also needed to be ‘got right first time’ because of the difficulty and cost to fix botched land capability and landscape form, and some failures were irreparable, e.g. scrambled top and sub soil. Both land capability and landscape form can be determined by a few quick field observations. They encapsulate critical land characteristics. They exemplify simple powerful metrics for rehabilitation.

Lesson 8 – environmental function

In the context of vegetating the rehabilitation, naif’s first inclination was to rely on secondary succession to establish the native climax species to restore natural biodiversity. This was adopted on many projects, and still is by project managers wanting to contain costs. While protagonists of this approach claim it works, the rehabilitation products do not withstand scrutiny. Relying solely on Nature yields disappointing results, and almost invariably some intervention is required, ranging from a ‘kick-start’ to years and even decades of aftercare just to establish and maintain a plant cover let alone restore environmental function and reinstate an ecological pyramid. Many buried pipeline projects have not recovered in 50 years (Mentis 2006 , Lesson 3). Scars are still evident along the animal-drawn transport routes used when diamonds and gold were discovered on the South African highveld in the late 1800s. Possibly some of the gullied pediments of eastern South Africa date back to the order of 1000 years when the land was first cultivated.

On opencast coal mines the early rehabilitators did not rely on succession nor use native climax grasses, but instead sowed a mixture of pasture grasses, sometimes with legumes. Their rationale was that seed for the climax grasses was not available in quantity, and that in any case these climax grasses were more difficult to establish than commercially available grasses. They hoped legumes would fix nitrogen, reduce the need for expensive fertilizers, and aid revegetation. The logic for the seed mix was apparently a belief that if a spectrum was sowed, hopefully one or other species might prove suitable, germinate and establish. Naif did not, at the outset, have any better ideas, but presently a perspective emerged.

Sowing the seed mix of pasture grasses failed in the poor soils of most rehabilitation areas in the absence of liming and fertilizing (Mentis 1999 , 2006 , 2019 , Lesson 3). If adequate lime and fertilizer were applied, then, in the humid steppe region, three sowed tall-growing grasses ( Chloris gayana , Eragrostis curvula and Digitaria eriantha ) prevailed to the virtual exclusion of all else, including Cynodon dactylon , the legume lucerne ( Medicago sativa ), annual non-grass herbs (weeds) and declared alien invader plants (Mentis 1999 , 2006 , 2019 ). The short-growing C. dactylon was possibly shaded out by the dense tall grasses, and the legume, weeds and invader plants competitively excluded. In the plant world, possession is indeed nine tenths of the law. While lucerne did fix nitrogen, when cows ate lucerne they suffered bloat. Perhaps other legumes, such as poor man’s lucerne ( Sericea lespedeza ), might be better, but they have not been tried sufficiently.

In the early guidelines of the erstwhile Chamber of Mines in South Africa, the late Professor John de Villiers advised that a goal of rehabilitation should be to restore soil function by replenishing soil organic carbon under grass. Around this was founded a so-called revegetation paradigm that establishes a pasture with fertilizer-responsive grasses, maintains this high production system for at least a few years, after which reversion to native grassland can be achieved by withholding fertilizers yet continuing with defoliation management (Mentis 1999 , 2006 , 2019 ).

This revegetation paradigm was corroborated with several data bases involving hundreds of sample sites and showing association of perennial grass establishment and soil organic carbon with soil phosphate, potassium and zinc (Table 2 ). In regression analyses, available soil phosphate was the main independent variable to predict pasture structure, a proxy for revegetation success. That does not prove the paradigm correct, but the balance of evidence is to effect that resort to conventional perennial pasture establishment and maintenance for a few years is an effective method for restoring soil function, and providing a base for an ecological pyramid. On big projects clients want assurance that there is high chance of the revegetation method working. It is not simply a matter of the contractor having to repeat the revegetation at his cost if it fails. Failed revegetation often exposes the unprotected land to erosive storms resulting in irreversible loss of topsoil and long-term impairment to the quality of the rehabilitation. There are indeed other revegetation methods available, and they may be appropriate, depending on circumstances (Mentis 2019 ). However, practitioners of conventional pasture establishment are far down the experience curve, the principles of Henderson’s and Moore’s laws apply (with every doubling of unit good production or service delivery the cost reduces by a constant fraction), and in common circumstances the technique is reliable and cost-effective.

The initial idea of protecting soil with a vegetation cover comprised of native plants has been subordinated by the need to restore environmental function that does not negate the initial intention but in the long term promotes it. Key ingredients of the revegetation paradigm are earthy material that can be developed into soil, fertilizer and adequate soil fertility, fertilizer-responsive grasses, and iterated ‘fertilize, grow grass and defoliate (mow, graze or burn)’ to produce ideally two grass crops per growing season. In this context there is little direct evidence on the role, and the benefits, of the herbivore, especially cattle. However, given that 80%–90% of nutrients ingested by the cow are returned to the pasture in dung and urine, the suspected benefits include the following. Nutrient cycling is set up (compare with cut and bale where nutrients are exported in the hay). This benefits the grasses and, by appropriate grazing and resting schedules, stimulates vegetative reproduction in the grasses that then leads to grazing lawns that are protective of the soil and are productive. Instead of the nutrients being locked up in soil and plants, the nutrients are cycled and become available to an array of wildlife including grasshoppers, butterflies, birds and dung beetles which themselves aid in the nutrient cycling.

It is expected that the nature of the soil strongly affects the plants that grow in it. Bell ( 2013 ), Macdonald et al. ( 2015 ) and Mentis ( 2019 ) gave extensive treatment to soil factors as constraints or limiting factors on revegetation in forest and other areas disturbed by mining and other agents. The constraints are liable to vary according to locality. They need to be identified to guide soil amelioration, plants species selection, propagation and aftercare. The merits of alternative approaches can usefully be compared (Parotta and Knowles 1999 ).

In Lesson 8 naif learnt that the needs of revegetation transcended establishing just an immediate natural vegetation or just any vegetation cover. Revegetation can and should be a primary means of restoring soil and thereby environmental function, and achieving this might have to precede attempts to reinstate a natural vegetation and native biodiversity, or selection of a crop to cultivate.

Lesson 9 – innovation

Naif’s starting position was that of the classic conflict between environmental regulation and company profitability or competitiveness. According to this perception, tightening regulation, such as raising rehabilitation standards, increases costs and erodes company competitiveness, so there is opposition to regulation.

This classic view, intuitively arrived at in Kahneman’s mode 1 thinking, sees the world as static. This view is unrealistic, though, and it misleads government and business into moderating regulation ‘for the sake of the economy’. The reality is that technology, products, processes and consumer needs are not fixed but dynamic (Porter and van der Linde 1998 ). Innovation permits the costs of meeting regulations to be run down. In an era of inevitably ever-increasing environmental regulation, the company that can develop cost-effective regulatory compliance (e.g. rehabilitate to the high standard cheaply and effectively) stands to improve its bottom line, and thereby its competitiveness.

When naif sets out 25 years ago on the initiative of rehabilitation standards the level of practice, and even expectations of it, fell short of what they are today. The lessons explained in this article are testimony to innovation and dynamism in environmental rehabilitation. For example, the progressive mining companies are landscaping to low profiles that do not need berms and other conservation structures, and while only 5 years ago they were saying it was impossible to strip top and sub soil separately they are now modifying their procedures and procuring machinery that could cut the cost of restoring soil and environmental function and produce a better rehabilitation product.

Lesson 9 was therefore a breakaway from rehabilitation being constrained by cost. In the immediate term, the budget does indeed limit what is done, but when project planning begins with the end in mind, new ideas are tested, and improvements adopted, then better rehabilitation costs less.

Lesson 10 – leadership

Naif’s starting position was archetypically reactive – rehabilitation is usually not the core business, so adopt good practice and comply with the law. In effect, this meant following not leading, with several unfavourable consequences that soon became apparent.

The reactive approach is vulnerable to outside intervention. For example, recently in South Africa the Centre for Environmental Rights took the coal mining industry, Department of Water and Sanitation and Department of Mineral Resources to task for non-compliance with the conditions of water use licences (CER 2019 ). The unsatisfactory state of affairs is illustrated by one mining client showing naif the conditions of her water use licence. There were 1000 conditions. It is not feasible to comply with, audit and enforce such complexity. This reflects badly on both business and government. The problem is not that South Africa is an under-resourced developing nation. During the time of the Mandela and Mbeki governments the South African Revenue Services developed superb efficiency. The central issue is the lack of political will in both business and government. Limited resources are no excuse, but rather cogent reason why they should be deployed efficiently.

Along with being reactive is failure to relentlessly pursue efficiency – the ever-better mouse-trap. The reluctant rehabilitator complains that rehabilitation is just a cost, yet he does nothing to limit that cost.

The take-home message of Lesson 10 is for business to be proactive by taking leadership, developing standards, working out how to meet the standards, designing a few simple powerful metrics to measure performance against the standards, embarking on continuous improvement, and reporting. The benefits of being the best are better rehabilitation at less cost, and the deployment of rehabilitation expertise as an offensive weapon against industry competitors and a defensive weapon against would-be outside intervention by activists and government. Peter Drucker, the founder of modern business management, is reputed to have said ‘The best way to predict the future is to make it.’

The lessons presented in this article are summarized in Table 3 . Warranting discussion are issues concerning what constrains achieving high-standard rehabilitation and other environmental management.

The first issue concerns the need and justification for environmental regulation, including rehabilitation. Why do some business and government leaders not support, implement and enforce conservation, environmental management and rehabilitation? There are several possibilities.

The function of business is interpreted strictly to increase business owner wealth with fiduciary responsibility to ensure funds are not expended on non-revenue earning activities like environmental care? But plainly the unbridled pursuit of wealth can hurt people and damage the environment, and law may exist to constrain business and other activity (e.g. the South African Constitution).

Business and government leaders consider that spending on non-revenue activities raises costs, reduces company profitability, and damages the national economy. This static view is surely invalid (Lesson 9) though that of course does not stop people believing it.

The influential leaders are waiting for science and technology to prove that environmental management and rehabilitation are necessary, in disregard or ignorance of value neutral science and technology being incapable of doing that (Lesson 2).

Perhaps the leaders are not ignorant but are populists who believe stakeholders and voters are ignorant and hold the static view of regulation vs costs, and await final proof from science and technology.

Possibly the leaders are smarter than the professionals who write ‘clever’ articles, or perhaps the leaders are not capable of grasping the issues even when explained.

Different leaders likely behave the way they do for different reasons, but in any given case it helps to know the nature of the obstructing or unsupportive mindset.

A second issue is that values, beliefs and actions of leaders are at least as fundamental to effective rehabilitation as the technical knowledge on how to put it back like it was. The human mind is among the most potent of causative agents. Among the other lessons naif learnt is that technical knowledge is a necessary but insufficient means to achievement. Without business owner and top management commitment, high standard rehabilitation will not be achieved regardless of technical know-how, but given owner and management commitment just about any technical obstacle can be overcome. Previously a figure of speech about the impossible was ‘fly to the moon’. Yet United States former President JF Kennedy committed to land a man on the moon, and it happened.

Just how might leadership drive environmental management, including rehabilitation? It needs to make policy commitment and to iterate plan-do-review-revise. Clients vary in their adoption of this. Those who make fastest progress are clients whose top management is committed and requires, after plan-do, a rehabilitation assessment report and a face-to-face discussion addressing such questions as: What are we trying to do? How well are we doing? What should we do now? The same report and in vivo discussion, but without the top managers, results in slower progress, if any. Submitting a report without the review discussion correlates with declining performance. Hence, if business owners want rehabilitation done to a high standard they must appoint top managers who are culturally attuned to design and implement the strategies to see the rehabilitation done (Groysberg et al. 2018 ).

A third constraint is that the requirement to get rehabilitation done is not uniformly applied, at least in South Africa. Mines are targeted. They are indeed among the big damagers to environmental function and services. However, land withdrawn from crop and tree cultivation, decommissioning of road and other linear projects and contaminated industrial land largely escape attention. Even within the mining industry the law is not applied uniformly. This of course is in conflict with the principle of equality before the law. Any leniency predicated on such grounds as affirmative action are short-sighted, for that does not promote national competitiveness and ultimately it is the taxpayer who will suffer, either in footing the bill for the rehabilitation to be undertaken later or in bearing the costs of future impaired environmental function and services.

Availability of data and materials

Please contact author for data request.

Abbreviations

- Cost benefit analysis

Bell RW (2002) Restoration of degraded landscapes: principles and lessons from case studies with salt-affected land and mine revegetation. CMU J 1(1):1–21

Google Scholar

Bell RW (2013) Land restoration. In: Jorgensen SE (ed) Encyclopedia of environmental management. CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group, USA

CER (2019) The truth about Mpumalanga coal mines failure to comply with their water use licences. Centre for Environmental Rights, Cape Town

Davidson RL (1964) An experimental study of succession in the Transvaal Highveld. In: Davis DHS (ed) Ecological studies in southern Africa. Junk, The Hague

De Klerk LP, Claasen M (2015) Proceedings of the workshop on South Africa mining-related landscape rehabilitation status quo: identifying research work required to close knowledge gaps. Report to Water Research Commission. CSIR report no.: CSIR/WR/2015/00/10/C

Drucker PF (1967) The effective executive. Heinemann, London

Farber DA, Hemmersbaugh PA (1993) The shadow of the future: discount rates, later generations and the environment. Vanderbilt Law Rev 46:267–304

Groysberg B, Lee J, Price J, Cheng Y (2018) The leader’s guide to corporate culture: how to manage the eight critical elements of organizational life. Harvard Bus Rev January–February 2018, p 44–52

Hancock GR, Martin Duque JF, Willgoose GR (2019) Geomorphic design and modelling at catchment scale for best mine rehabilitation – The Drayton mine example (New South Wales, Australia). Environ Model Softw. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsoft.2018.12.003

Hatting R, Tanner P, Aken M (2019) Land rehabilitation guidelines for surface coal mines. Land rehabilitation Society of Southern Africa, CoalTech, Minerals Council of South Africa

Kahneman D (2011) Thinking, fast and slow. Penguin, London

Kahneman D, Rosenfield AM, Gandhi L, Blaser T (2016) Noise. Harvard Bus Rev, October 2016:38–46

Macdonald SE, Landhäuser SM, Skousen J, Franklin J, Frouz J, Hall S, Jacobs DF, Quideau S (2015) Forest restoration following surface mining disturbance: challenges and solutions. New For 46:706–732. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11056-015-9506-4

Article Google Scholar

Martinez-Paz J, Amansa C, Casanovas V, Colin J (2016) Pooling expert opinion on environmental discounting: an international Delphi survey. Conserv Soc 14:243–253

Mentis M (2015) Managing project risks and uncertainties. Forest Ecosyst 2:2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40663-014-0026-z

Mentis M (2019) Environmental rehabilitation guide for South Africa. Quickfox, Johannesburg

Mentis MT (1999) Diagnosis of the rehabilitation of opencast coal mines on the Highveld of South Africa. South Afr J Sci 95:210–215

Mentis MT (2006) Restoring native grassland on land disturbed by coal mining on the eastern Highveld of South Africa. South Afr J Sci 102:193–197

CAS Google Scholar

Mentis MT, Ellery WN (1998) Environmental effects of mining coastal dunes: conjectures and refutations. South Afr J Sci 94:215–222

Murphy BW (2014) Soil organic matter and soil function – review of the literature and underlying data. Department of the Environment, Canberra

Parkinson CN (1958) Parkinson’s law: the pursuit of Progress. John Murray, London

Parotta JA, Knowles OH (1999) Restoration of tropical moist forests on bauxite-mined land in the Brazilian Amazon. Restor Ecol 7(2):103–116

Pearce D, Markandya A, Barbier EB (1989) Blueprint for a Green Economy. Earthscan Publications, London.

Porter ME, van der Linde C (1998) Green and competitive: ending the stalemate.In: Portr ME (Ed) On Competition. Harvard Business Review Book, Boston, pp351–375.

Roux E (1969) Grass: a story of Frankenwald. Oxford University Press, Cape Town

Schumacher EF (1973) Small is beautiful: economics as if people mattered. Harper & Row, New York

Snyman HA, Ingram LJ, Kirkman KP (2013) Themeda triandra : a keystone grass species. Afr J Range For Sci 30:99–125

Taleb NN (2001) Fooled by randomness: the hidden role of chance in life and in the markets. Penguin Random House, London

Tanner P, Möhr-Swart M (2007) Guidelines for the rehabilitation of mined land. Chamber of Mines of South Africa/Coal Tech, Johannesburg

World Commission on Environment and Development (1987) Our Common Future. Oxford University Press, USA

Download references

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Adriaan Oosthuizen for drawing attention to geomorphic landscape design.

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Postnet 540, Bag X9, Benmore, 2010, South Africa

Mike Mentis

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

MM compiled the entire manuscript. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Author’s information

The author has formal qualifications in agriculture, business and science (BSc, BSc (honours), MSc, PhD and MBA). He is a Principal Environmental Auditor and Full Member of the Institute of Environmental Management and Assessment of the United Kingdom, a Chartered Environmentalist with the Society for the Environment of the United Kingdom, a Professional Scientist registered with the South African Council for Scientific Professions, an Honorary Member of the Land Rehabilitation Society of Southern Africa, and a member of editorial board for Forest Ecosystems . The author is self-employed and has consulted on business and environmental issues for 30 years.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Mike Mentis .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate, consent for publication, competing interests.

The author declares he has no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Mentis, M. Environmental rehabilitation of damaged land. For. Ecosyst. 7 , 19 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40663-020-00233-4

Download citation

Received : 12 October 2019

Accepted : 23 March 2020

Published : 06 April 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s40663-020-00233-4

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Environmental function

- Land capability

- Landscape form

- Natural capital

- Rehabilitation

- Restoration

- Sustainability

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Int J Environ Res Public Health

Environmental Factors in the Rehabilitation Framework: Role of the One Health Approach to Improve the Complex Management of Disability

Lorenzo lippi.

1 Physical and Rehabilitative Medicine, Department of Health Sciences, University of Eastern Piedmont “A. Avogadro”, 28100 Novara, Italy