- Privacy Policy

Home » Significance of the Study – Examples and Writing Guide

Significance of the Study – Examples and Writing Guide

Table of Contents

Significance of the Study

Definition:

Significance of the study in research refers to the potential importance, relevance, or impact of the research findings. It outlines how the research contributes to the existing body of knowledge, what gaps it fills, or what new understanding it brings to a particular field of study.

In general, the significance of a study can be assessed based on several factors, including:

- Originality : The extent to which the study advances existing knowledge or introduces new ideas and perspectives.

- Practical relevance: The potential implications of the study for real-world situations, such as improving policy or practice.

- Theoretical contribution: The extent to which the study provides new insights or perspectives on theoretical concepts or frameworks.

- Methodological rigor : The extent to which the study employs appropriate and robust methods and techniques to generate reliable and valid data.

- Social or cultural impact : The potential impact of the study on society, culture, or public perception of a particular issue.

Types of Significance of the Study

The significance of the Study can be divided into the following types:

Theoretical Significance

Theoretical significance refers to the contribution that a study makes to the existing body of theories in a specific field. This could be by confirming, refuting, or adding nuance to a currently accepted theory, or by proposing an entirely new theory.

Practical Significance

Practical significance refers to the direct applicability and usefulness of the research findings in real-world contexts. Studies with practical significance often address real-life problems and offer potential solutions or strategies. For example, a study in the field of public health might identify a new intervention that significantly reduces the spread of a certain disease.

Significance for Future Research

This pertains to the potential of a study to inspire further research. A study might open up new areas of investigation, provide new research methodologies, or propose new hypotheses that need to be tested.

How to Write Significance of the Study

Here’s a guide to writing an effective “Significance of the Study” section in research paper, thesis, or dissertation:

- Background : Begin by giving some context about your study. This could include a brief introduction to your subject area, the current state of research in the field, and the specific problem or question your study addresses.

- Identify the Gap : Demonstrate that there’s a gap in the existing literature or knowledge that needs to be filled, which is where your study comes in. The gap could be a lack of research on a particular topic, differing results in existing studies, or a new problem that has arisen and hasn’t yet been studied.

- State the Purpose of Your Study : Clearly state the main objective of your research. You may want to state the purpose as a solution to the problem or gap you’ve previously identified.

- Contributes to the existing body of knowledge.

- Addresses a significant research gap.

- Offers a new or better solution to a problem.

- Impacts policy or practice.

- Leads to improvements in a particular field or sector.

- Identify Beneficiaries : Identify who will benefit from your study. This could include other researchers, practitioners in your field, policy-makers, communities, businesses, or others. Explain how your findings could be used and by whom.

- Future Implications : Discuss the implications of your study for future research. This could involve questions that are left open, new questions that have been raised, or potential future methodologies suggested by your study.

Significance of the Study in Research Paper

The Significance of the Study in a research paper refers to the importance or relevance of the research topic being investigated. It answers the question “Why is this research important?” and highlights the potential contributions and impacts of the study.

The significance of the study can be presented in the introduction or background section of a research paper. It typically includes the following components:

- Importance of the research problem: This describes why the research problem is worth investigating and how it relates to existing knowledge and theories.

- Potential benefits and implications: This explains the potential contributions and impacts of the research on theory, practice, policy, or society.

- Originality and novelty: This highlights how the research adds new insights, approaches, or methods to the existing body of knowledge.

- Scope and limitations: This outlines the boundaries and constraints of the research and clarifies what the study will and will not address.

Suppose a researcher is conducting a study on the “Effects of social media use on the mental health of adolescents”.

The significance of the study may be:

“The present study is significant because it addresses a pressing public health issue of the negative impact of social media use on adolescent mental health. Given the widespread use of social media among this age group, understanding the effects of social media on mental health is critical for developing effective prevention and intervention strategies. This study will contribute to the existing literature by examining the moderating factors that may affect the relationship between social media use and mental health outcomes. It will also shed light on the potential benefits and risks of social media use for adolescents and inform the development of evidence-based guidelines for promoting healthy social media use among this population. The limitations of this study include the use of self-reported measures and the cross-sectional design, which precludes causal inference.”

Significance of the Study In Thesis

The significance of the study in a thesis refers to the importance or relevance of the research topic and the potential impact of the study on the field of study or society as a whole. It explains why the research is worth doing and what contribution it will make to existing knowledge.

For example, the significance of a thesis on “Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare” could be:

- With the increasing availability of healthcare data and the development of advanced machine learning algorithms, AI has the potential to revolutionize the healthcare industry by improving diagnosis, treatment, and patient outcomes. Therefore, this thesis can contribute to the understanding of how AI can be applied in healthcare and how it can benefit patients and healthcare providers.

- AI in healthcare also raises ethical and social issues, such as privacy concerns, bias in algorithms, and the impact on healthcare jobs. By exploring these issues in the thesis, it can provide insights into the potential risks and benefits of AI in healthcare and inform policy decisions.

- Finally, the thesis can also advance the field of computer science by developing new AI algorithms or techniques that can be applied to healthcare data, which can have broader applications in other industries or fields of research.

Significance of the Study in Research Proposal

The significance of a study in a research proposal refers to the importance or relevance of the research question, problem, or objective that the study aims to address. It explains why the research is valuable, relevant, and important to the academic or scientific community, policymakers, or society at large. A strong statement of significance can help to persuade the reviewers or funders of the research proposal that the study is worth funding and conducting.

Here is an example of a significance statement in a research proposal:

Title : The Effects of Gamification on Learning Programming: A Comparative Study

Significance Statement:

This proposed study aims to investigate the effects of gamification on learning programming. With the increasing demand for computer science professionals, programming has become a fundamental skill in the computer field. However, learning programming can be challenging, and students may struggle with motivation and engagement. Gamification has emerged as a promising approach to improve students’ engagement and motivation in learning, but its effects on programming education are not yet fully understood. This study is significant because it can provide valuable insights into the potential benefits of gamification in programming education and inform the development of effective teaching strategies to enhance students’ learning outcomes and interest in programming.

Examples of Significance of the Study

Here are some examples of the significance of a study that indicates how you can write this into your research paper according to your research topic:

Research on an Improved Water Filtration System : This study has the potential to impact millions of people living in water-scarce regions or those with limited access to clean water. A more efficient and affordable water filtration system can reduce water-borne diseases and improve the overall health of communities, enabling them to lead healthier, more productive lives.

Study on the Impact of Remote Work on Employee Productivity : Given the shift towards remote work due to recent events such as the COVID-19 pandemic, this study is of considerable significance. Findings could help organizations better structure their remote work policies and offer insights on how to maximize employee productivity, wellbeing, and job satisfaction.

Investigation into the Use of Solar Power in Developing Countries : With the world increasingly moving towards renewable energy, this study could provide important data on the feasibility and benefits of implementing solar power solutions in developing countries. This could potentially stimulate economic growth, reduce reliance on non-renewable resources, and contribute to global efforts to combat climate change.

Research on New Learning Strategies in Special Education : This study has the potential to greatly impact the field of special education. By understanding the effectiveness of new learning strategies, educators can improve their curriculum to provide better support for students with learning disabilities, fostering their academic growth and social development.

Examination of Mental Health Support in the Workplace : This study could highlight the impact of mental health initiatives on employee wellbeing and productivity. It could influence organizational policies across industries, promoting the implementation of mental health programs in the workplace, ultimately leading to healthier work environments.

Evaluation of a New Cancer Treatment Method : The significance of this study could be lifesaving. The research could lead to the development of more effective cancer treatments, increasing the survival rate and quality of life for patients worldwide.

When to Write Significance of the Study

The Significance of the Study section is an integral part of a research proposal or a thesis. This section is typically written after the introduction and the literature review. In the research process, the structure typically follows this order:

- Title – The name of your research.

- Abstract – A brief summary of the entire research.

- Introduction – A presentation of the problem your research aims to solve.

- Literature Review – A review of existing research on the topic to establish what is already known and where gaps exist.

- Significance of the Study – An explanation of why the research matters and its potential impact.

In the Significance of the Study section, you will discuss why your study is important, who it benefits, and how it adds to existing knowledge or practice in your field. This section is your opportunity to convince readers, and potentially funders or supervisors, that your research is valuable and worth undertaking.

Advantages of Significance of the Study

The Significance of the Study section in a research paper has multiple advantages:

- Establishes Relevance: This section helps to articulate the importance of your research to your field of study, as well as the wider society, by explicitly stating its relevance. This makes it easier for other researchers, funders, and policymakers to understand why your work is necessary and worth supporting.

- Guides the Research: Writing the significance can help you refine your research questions and objectives. This happens as you critically think about why your research is important and how it contributes to your field.

- Attracts Funding: If you are seeking funding or support for your research, having a well-written significance of the study section can be key. It helps to convince potential funders of the value of your work.

- Opens up Further Research: By stating the significance of the study, you’re also indicating what further research could be carried out in the future, based on your work. This helps to pave the way for future studies and demonstrates that your research is a valuable addition to the field.

- Provides Practical Applications: The significance of the study section often outlines how the research can be applied in real-world situations. This can be particularly important in applied sciences, where the practical implications of research are crucial.

- Enhances Understanding: This section can help readers understand how your study fits into the broader context of your field, adding value to the existing literature and contributing new knowledge or insights.

Limitations of Significance of the Study

The Significance of the Study section plays an essential role in any research. However, it is not without potential limitations. Here are some that you should be aware of:

- Subjectivity: The importance and implications of a study can be subjective and may vary from person to person. What one researcher considers significant might be seen as less critical by others. The assessment of significance often depends on personal judgement, biases, and perspectives.

- Predictability of Impact: While you can outline the potential implications of your research in the Significance of the Study section, the actual impact can be unpredictable. Research doesn’t always yield the expected results or have the predicted impact on the field or society.

- Difficulty in Measuring: The significance of a study is often qualitative and can be challenging to measure or quantify. You can explain how you think your research will contribute to your field or society, but measuring these outcomes can be complex.

- Possibility of Overstatement: Researchers may feel pressured to amplify the potential significance of their study to attract funding or interest. This can lead to overstating the potential benefits or implications, which can harm the credibility of the study if these results are not achieved.

- Overshadowing of Limitations: Sometimes, the significance of the study may overshadow the limitations of the research. It is important to balance the potential significance with a thorough discussion of the study’s limitations.

- Dependence on Successful Implementation: The significance of the study relies on the successful implementation of the research. If the research process has flaws or unexpected issues arise, the anticipated significance might not be realized.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Conceptual Framework – Types, Methodology and...

Context of the Study – Writing Guide and Examples

Critical Analysis – Types, Examples and Writing...

Problem Statement – Writing Guide, Examples and...

Research Paper Introduction – Writing Guide and...

Research Paper Outline – Types, Example, Template

The Savvy Scientist

Experiences of a London PhD student and beyond

What is the Significance of a Study? Examples and Guide

If you’re reading this post you’re probably wondering: what is the significance of a study?

No matter where you’re at with a piece of research, it is a good idea to think about the potential significance of your work. And sometimes you’ll have to explicitly write a statement of significance in your papers, it addition to it forming part of your thesis.

In this post I’ll cover what the significance of a study is, how to measure it, how to describe it with examples and add in some of my own experiences having now worked in research for over nine years.

If you’re reading this because you’re writing up your first paper, welcome! You may also like my how-to guide for all aspects of writing your first research paper .

Looking for guidance on writing the statement of significance for a paper or thesis? Click here to skip straight to that section.

What is the Significance of a Study?

For research papers, theses or dissertations it’s common to explicitly write a section describing the significance of the study. We’ll come onto what to include in that section in just a moment.

However the significance of a study can actually refer to several different things.

Working our way from the most technical to the broadest, depending on the context, the significance of a study may refer to:

- Within your study: Statistical significance. Can we trust the findings?

- Wider research field: Research significance. How does your study progress the field?

- Commercial / economic significance: Could there be business opportunities for your findings?

- Societal significance: What impact could your study have on the wider society.

- And probably other domain-specific significance!

We’ll shortly cover each of them in turn, including how they’re measured and some examples for each type of study significance.

But first, let’s touch on why you should consider the significance of your research at an early stage.

Why Care About the Significance of a Study?

No matter what is motivating you to carry out your research, it is sensible to think about the potential significance of your work. In the broadest sense this asks, how does the study contribute to the world?

After all, for many people research is only worth doing if it will result in some expected significance. For the vast majority of us our studies won’t be significant enough to reach the evening news, but most studies will help to enhance knowledge in a particular field and when research has at least some significance it makes for a far more fulfilling longterm pursuit.

Furthermore, a lot of us are carrying out research funded by the public. It therefore makes sense to keep an eye on what benefits the work could bring to the wider community.

Often in research you’ll come to a crossroads where you must decide which path of research to pursue. Thinking about the potential benefits of a strand of research can be useful for deciding how to spend your time, money and resources.

It’s worth noting though, that not all research activities have to work towards obvious significance. This is especially true while you’re a PhD student, where you’re figuring out what you enjoy and may simply be looking for an opportunity to learn a new skill.

However, if you’re trying to decide between two potential projects, it can be useful to weigh up the potential significance of each.

Let’s now dive into the different types of significance, starting with research significance.

Research Significance

What is the research significance of a study.

Unless someone specifies which type of significance they’re referring to, it is fair to assume that they want to know about the research significance of your study.

Research significance describes how your work has contributed to the field, how it could inform future studies and progress research.

Where should I write about my study’s significance in my thesis?

Typically you should write about your study’s significance in the Introduction and Conclusions sections of your thesis.

It’s important to mention it in the Introduction so that the relevance of your work and the potential impact and benefits it could have on the field are immediately apparent. Explaining why your work matters will help to engage readers (and examiners!) early on.

It’s also a good idea to detail the study’s significance in your Conclusions section. This adds weight to your findings and helps explain what your study contributes to the field.

On occasion you may also choose to include a brief description in your Abstract.

What is expected when submitting an article to a journal

It is common for journals to request a statement of significance, although this can sometimes be called other things such as:

- Impact statement

- Significance statement

- Advances in knowledge section

Here is one such example of what is expected:

Impact Statement: An Impact Statement is required for all submissions. Your impact statement will be evaluated by the Editor-in-Chief, Global Editors, and appropriate Associate Editor. For your manuscript to receive full review, the editors must be convinced that it is an important advance in for the field. The Impact Statement is not a restating of the abstract. It should address the following: Why is the work submitted important to the field? How does the work submitted advance the field? What new information does this work impart to the field? How does this new information impact the field? Experimental Biology and Medicine journal, author guidelines

Typically the impact statement will be shorter than the Abstract, around 150 words.

Defining the study’s significance is helpful not just for the impact statement (if the journal asks for one) but also for building a more compelling argument throughout your submission. For instance, usually you’ll start the Discussion section of a paper by highlighting the research significance of your work. You’ll also include a short description in your Abstract too.

How to describe the research significance of a study, with examples

Whether you’re writing a thesis or a journal article, the approach to writing about the significance of a study are broadly the same.

I’d therefore suggest using the questions above as a starting point to base your statements on.

- Why is the work submitted important to the field?

- How does the work submitted advance the field?

- What new information does this work impart to the field?

- How does this new information impact the field?

Answer those questions and you’ll have a much clearer idea of the research significance of your work.

When describing it, try to clearly state what is novel about your study’s contribution to the literature. Then go on to discuss what impact it could have on progressing the field along with recommendations for future work.

Potential sentence starters

If you’re not sure where to start, why not set a 10 minute timer and have a go at trying to finish a few of the following sentences. Not sure on what to put? Have a chat to your supervisor or lab mates and they may be able to suggest some ideas.

- This study is important to the field because…

- These findings advance the field by…

- Our results highlight the importance of…

- Our discoveries impact the field by…

Now you’ve had a go let’s have a look at some real life examples.

Statement of significance examples

A statement of significance / impact:

Impact Statement This review highlights the historical development of the concept of “ideal protein” that began in the 1950s and 1980s for poultry and swine diets, respectively, and the major conceptual deficiencies of the long-standing concept of “ideal protein” in animal nutrition based on recent advances in amino acid (AA) metabolism and functions. Nutritionists should move beyond the “ideal protein” concept to consider optimum ratios and amounts of all proteinogenic AAs in animal foods and, in the case of carnivores, also taurine. This will help formulate effective low-protein diets for livestock, poultry, and fish, while sustaining global animal production. Because they are not only species of agricultural importance, but also useful models to study the biology and diseases of humans as well as companion (e.g. dogs and cats), zoo, and extinct animals in the world, our work applies to a more general readership than the nutritionists and producers of farm animals. Wu G, Li P. The “ideal protein” concept is not ideal in animal nutrition. Experimental Biology and Medicine . 2022;247(13):1191-1201. doi: 10.1177/15353702221082658

And the same type of section but this time called “Advances in knowledge”:

Advances in knowledge: According to the MY-RADs criteria, size measurements of focal lesions in MRI are now of relevance for response assessment in patients with monoclonal plasma cell disorders. Size changes of 1 or 2 mm are frequently observed due to uncertainty of the measurement only, while the actual focal lesion has not undergone any biological change. Size changes of at least 6 mm or more in T 1 weighted or T 2 weighted short tau inversion recovery sequences occur in only 5% or less of cases when the focal lesion has not undergone any biological change. Wennmann M, Grözinger M, Weru V, et al. Test-retest, inter- and intra-rater reproducibility of size measurements of focal bone marrow lesions in MRI in patients with multiple myeloma [published online ahead of print, 2023 Apr 12]. Br J Radiol . 2023;20220745. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20220745

Other examples of research significance

Moving beyond the formal statement of significance, here is how you can describe research significance more broadly within your paper.

Describing research impact in an Abstract of a paper:

Three-dimensional visualisation and quantification of the chondrocyte population within articular cartilage can be achieved across a field of view of several millimetres using laboratory-based micro-CT. The ability to map chondrocytes in 3D opens possibilities for research in fields from skeletal development through to medical device design and treatment of cartilage degeneration. Conclusions section of the abstract in my first paper .

In the Discussion section of a paper:

We report for the utility of a standard laboratory micro-CT scanner to visualise and quantify features of the chondrocyte population within intact articular cartilage in 3D. This study represents a complimentary addition to the growing body of evidence supporting the non-destructive imaging of the constituents of articular cartilage. This offers researchers the opportunity to image chondrocyte distributions in 3D without specialised synchrotron equipment, enabling investigations such as chondrocyte morphology across grades of cartilage damage, 3D strain mapping techniques such as digital volume correlation to evaluate mechanical properties in situ , and models for 3D finite element analysis in silico simulations. This enables an objective quantification of chondrocyte distribution and morphology in three dimensions allowing greater insight for investigations into studies of cartilage development, degeneration and repair. One such application of our method, is as a means to provide a 3D pattern in the cartilage which, when combined with digital volume correlation, could determine 3D strain gradient measurements enabling potential treatment and repair of cartilage degeneration. Moreover, the method proposed here will allow evaluation of cartilage implanted with tissue engineered scaffolds designed to promote chondral repair, providing valuable insight into the induced regenerative process. The Discussion section of the paper is laced with references to research significance.

How is longer term research significance measured?

Looking beyond writing impact statements within papers, sometimes you’ll want to quantify the long term research significance of your work. For instance when applying for jobs.

The most obvious measure of a study’s long term research significance is the number of citations it receives from future publications. The thinking is that a study which receives more citations will have had more research impact, and therefore significance , than a study which received less citations. Citations can give a broad indication of how useful the work is to other researchers but citations aren’t really a good measure of significance.

Bear in mind that us researchers can be lazy folks and sometimes are simply looking to cite the first paper which backs up one of our claims. You can find studies which receive a lot of citations simply for packaging up the obvious in a form which can be easily found and referenced, for instance by having a catchy or optimised title.

Likewise, research activity varies wildly between fields. Therefore a certain study may have had a big impact on a particular field but receive a modest number of citations, simply because not many other researchers are working in the field.

Nevertheless, citations are a standard measure of significance and for better or worse it remains impressive for someone to be the first author of a publication receiving lots of citations.

Other measures for the research significance of a study include:

- Accolades: best paper awards at conferences, thesis awards, “most downloaded” titles for articles, press coverage.

- How much follow-on research the study creates. For instance, part of my PhD involved a novel material initially developed by another PhD student in the lab. That PhD student’s research had unlocked lots of potential new studies and now lots of people in the group were using the same material and developing it for different applications. The initial study may not receive a high number of citations yet long term it generated a lot of research activity.

That covers research significance, but you’ll often want to consider other types of significance for your study and we’ll cover those next.

Statistical Significance

What is the statistical significance of a study.

Often as part of a study you’ll carry out statistical tests and then state the statistical significance of your findings: think p-values eg <0.05. It is useful to describe the outcome of these tests within your report or paper, to give a measure of statistical significance.

Effectively you are trying to show whether the performance of your innovation is actually better than a control or baseline and not just chance. Statistical significance deserves a whole other post so I won’t go into a huge amount of depth here.

Things that make publication in The BMJ impossible or unlikely Internal validity/robustness of the study • It had insufficient statistical power, making interpretation difficult; • Lack of statistical power; The British Medical Journal’s guide for authors

Calculating statistical significance isn’t always necessary (or valid) for a study, such as if you have a very small number of samples, but it is a very common requirement for scientific articles.

Writing a journal article? Check the journal’s guide for authors to see what they expect. Generally if you have approximately five or more samples or replicates it makes sense to start thinking about statistical tests. Speak to your supervisor and lab mates for advice, and look at other published articles in your field.

How is statistical significance measured?

Statistical significance is quantified using p-values . Depending on your study design you’ll choose different statistical tests to compute the p-value.

A p-value of 0.05 is a common threshold value. The 0.05 means that there is a 1/20 chance that the difference in performance you’re reporting is just down to random chance.

- p-values above 0.05 mean that the result isn’t statistically significant enough to be trusted: it is too likely that the effect you’re showing is just luck.

- p-values less than or equal to 0.05 mean that the result is statistically significant. In other words: unlikely to just be chance, which is usually considered a good outcome.

Low p-values (eg p = 0.001) mean that it is highly unlikely to be random chance (1/1000 in the case of p = 0.001), therefore more statistically significant.

It is important to clarify that, although low p-values mean that your findings are statistically significant, it doesn’t automatically mean that the result is scientifically important. More on that in the next section on research significance.

How to describe the statistical significance of your study, with examples

In the first paper from my PhD I ran some statistical tests to see if different staining techniques (basically dyes) increased how well you could see cells in cow tissue using micro-CT scanning (a 3D imaging technique).

In your methods section you should mention the statistical tests you conducted and then in the results you will have statements such as:

Between mediums for the two scan protocols C/N [contrast to noise ratio] was greater for EtOH than the PBS in both scanning methods (both p < 0.0001) with mean differences of 1.243 (95% CI [confidence interval] 0.709 to 1.778) for absorption contrast and 6.231 (95% CI 5.772 to 6.690) for propagation contrast. … Two repeat propagation scans were taken of samples from the PTA-stained groups. No difference in mean C/N was found with either medium: PBS had a mean difference of 0.058 ( p = 0.852, 95% CI -0.560 to 0.676), EtOH had a mean difference of 1.183 ( p = 0.112, 95% CI 0.281 to 2.648). From the Results section of my first paper, available here . Square brackets added for this post to aid clarity.

From this text the reader can infer from the first paragraph that there was a statistically significant difference in using EtOH compared to PBS (really small p-value of <0.0001). However, from the second paragraph, the difference between two repeat scans was statistically insignificant for both PBS (p = 0.852) and EtOH (p = 0.112).

By conducting these statistical tests you have then earned your right to make bold statements, such as these from the discussion section:

Propagation phase-contrast increases the contrast of individual chondrocytes [cartilage cells] compared to using absorption contrast. From the Discussion section from the same paper.

Without statistical tests you have no evidence that your results are not just down to random chance.

Beyond describing the statistical significance of a study in the main body text of your work, you can also show it in your figures.

In figures such as bar charts you’ll often see asterisks to represent statistical significance, and “n.s.” to show differences between groups which are not statistically significant. Here is one such figure, with some subplots, from the same paper:

In this example an asterisk (*) between two bars represents p < 0.05. Two asterisks (**) represents p < 0.001 and three asterisks (***) represents p < 0.0001. This should always be stated in the caption of your figure since the values that each asterisk refers to can vary.

Now that we know if a study is showing statistically and research significance, let’s zoom out a little and consider the potential for commercial significance.

Commercial and Industrial Significance

What are commercial and industrial significance.

Moving beyond significance in relation to academia, your research may also have commercial or economic significance.

Simply put:

- Commercial significance: could the research be commercialised as a product or service? Perhaps the underlying technology described in your study could be licensed to a company or you could even start your own business using it.

- Industrial significance: more widely than just providing a product which could be sold, does your research provide insights which may affect a whole industry? Such as: revealing insights or issues with current practices, performance gains you don’t want to commercialise (e.g. solar power efficiency), providing suggested frameworks or improvements which could be employed industry-wide.

I’ve grouped these two together because there can certainly be overlap. For instance, perhaps your new technology could be commercialised whilst providing wider improvements for the whole industry.

Commercial and industrial significance are not relevant to most studies, so only write about it if you and your supervisor can think of reasonable routes to your work having an impact in these ways.

How are commercial and industrial significance measured?

Unlike statistical and research significances, the measures of commercial and industrial significance can be much more broad.

Here are some potential measures of significance:

Commercial significance:

- How much value does your technology bring to potential customers or users?

- How big is the potential market and how much revenue could the product potentially generate?

- Is the intellectual property protectable? i.e. patentable, or if not could the novelty be protected with trade secrets: if so publish your method with caution!

- If commercialised, could the product bring employment to a geographical area?

Industrial significance:

What impact could it have on the industry? For instance if you’re revealing an issue with something, such as unintended negative consequences of a drug , what does that mean for the industry and the public? This could be:

- Reduced overhead costs

- Better safety

- Faster production methods

- Improved scaleability

How to describe the commercial and industrial significance of a study, with examples

Commercial significance.

If your technology could be commercially viable, and you’ve got an interest in commercialising it yourself, it is likely that you and your university may not want to immediately publish the study in a journal.

You’ll probably want to consider routes to exploiting the technology and your university may have a “technology transfer” team to help researchers navigate the various options.

However, if instead of publishing a paper you’re submitting a thesis or dissertation then it can be useful to highlight the commercial significance of your work. In this instance you could include statements of commercial significance such as:

The measurement technology described in this study provides state of the art performance and could enable the development of low cost devices for aerospace applications. An example of commercial significance I invented for this post

Industrial significance

First, think about the industrial sectors who could benefit from the developments described in your study.

For example if you’re working to improve battery efficiency it is easy to think of how it could lead to performance gains for certain industries, like personal electronics or electric vehicles. In these instances you can describe the industrial significance relatively easily, based off your findings.

For example:

By utilising abundant materials in the described battery fabrication process we provide a framework for battery manufacturers to reduce dependence on rare earth components. Again, an invented example

For other technologies there may well be industrial applications but they are less immediately obvious and applicable. In these scenarios the best you can do is to simply reframe your research significance statement in terms of potential commercial applications in a broad way.

As a reminder: not all studies should address industrial significance, so don’t try to invent applications just for the sake of it!

Societal Significance

What is the societal significance of a study.

The most broad category of significance is the societal impact which could stem from it.

If you’re working in an applied field it may be quite easy to see a route for your research to impact society. For others, the route to societal significance may be less immediate or clear.

Studies can help with big issues facing society such as:

- Medical applications : vaccines, surgical implants, drugs, improving patient safety. For instance this medical device and drug combination I worked on which has a very direct route to societal significance.

- Political significance : Your research may provide insights which could contribute towards potential changes in policy or better understanding of issues facing society.

- Public health : for instance COVID-19 transmission and related decisions.

- Climate change : mitigation such as more efficient solar panels and lower cost battery solutions, and studying required adaptation efforts and technologies. Also, better understanding around related societal issues, for instance this study on the effects of temperature on hate speech.

How is societal significance measured?

Societal significance at a high level can be quantified by the size of its potential societal effect. Just like a lab risk assessment, you can think of it in terms of probability (or how many people it could help) and impact magnitude.

Societal impact = How many people it could help x the magnitude of the impact

Think about how widely applicable the findings are: for instance does it affect only certain people? Then think about the potential size of the impact: what kind of difference could it make to those people?

Between these two metrics you can get a pretty good overview of the potential societal significance of your research study.

How to describe the societal significance of a study, with examples

Quite often the broad societal significance of your study is what you’re setting the scene for in your Introduction. In addition to describing the existing literature, it is common to for the study’s motivation to touch on its wider impact for society.

For those of us working in healthcare research it is usually pretty easy to see a path towards societal significance.

Our CLOUT model has state-of-the-art performance in mortality prediction, surpassing other competitive NN models and a logistic regression model … Our results show that the risk factors identified by the CLOUT model agree with physicians’ assessment, suggesting that CLOUT could be used in real-world clinicalsettings. Our results strongly support that CLOUT may be a useful tool to generate clinical prediction models, especially among hospitalized and critically ill patient populations. Learning Latent Space Representations to Predict Patient Outcomes: Model Development and Validation

In other domains the societal significance may either take longer or be more indirect, meaning that it can be more difficult to describe the societal impact.

Even so, here are some examples I’ve found from studies in non-healthcare domains:

We examined food waste as an initial investigation and test of this methodology, and there is clear potential for the examination of not only other policy texts related to food waste (e.g., liability protection, tax incentives, etc.; Broad Leib et al., 2020) but related to sustainable fishing (Worm et al., 2006) and energy use (Hawken, 2017). These other areas are of obvious relevance to climate change… AI-Based Text Analysis for Evaluating Food Waste Policies

The continued development of state-of-the art NLP tools tailored to climate policy will allow climate researchers and policy makers to extract meaningful information from this growing body of text, to monitor trends over time and administrative units, and to identify potential policy improvements. BERT Classification of Paris Agreement Climate Action Plans

Top Tips For Identifying & Writing About the Significance of Your Study

- Writing a thesis? Describe the significance of your study in the Introduction and the Conclusion .

- Submitting a paper? Read the journal’s guidelines. If you’re writing a statement of significance for a journal, make sure you read any guidance they give for what they’re expecting.

- Take a step back from your research and consider your study’s main contributions.

- Read previously published studies in your field . Use this for inspiration and ideas on how to describe the significance of your own study

- Discuss the study with your supervisor and potential co-authors or collaborators and brainstorm potential types of significance for it.

Now you’ve finished reading up on the significance of a study you may also like my how-to guide for all aspects of writing your first research paper .

Writing an academic journal paper

I hope that you’ve learned something useful from this article about the significance of a study. If you have any more research-related questions let me know, I’m here to help.

To gain access to my content library you can subscribe below for free:

Share this:

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

Related Posts

Minor Corrections: How To Make Them and Succeed With Your PhD Thesis

2nd June 2024 2nd June 2024

How to Master Data Management in Research

25th April 2024 27th April 2024

Thesis Title: Examples and Suggestions from a PhD Grad

23rd February 2024 23rd February 2024

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Privacy Overview

How To Write Significance of the Study (With Examples)

Whether you’re writing a research paper or thesis, a portion called Significance of the Study ensures your readers understand the impact of your work. Learn how to effectively write this vital part of your research paper or thesis through our detailed steps, guidelines, and examples.

Related: How to Write a Concept Paper for Academic Research

Table of Contents

What is the significance of the study.

The Significance of the Study presents the importance of your research. It allows you to prove the study’s impact on your field of research, the new knowledge it contributes, and the people who will benefit from it.

Related: How To Write Scope and Delimitation of a Research Paper (With Examples)

Where Should I Put the Significance of the Study?

The Significance of the Study is part of the first chapter or the Introduction. It comes after the research’s rationale, problem statement, and hypothesis.

Related: How to Make Conceptual Framework (with Examples and Templates)

Why Should I Include the Significance of the Study?

The purpose of the Significance of the Study is to give you space to explain to your readers how exactly your research will be contributing to the literature of the field you are studying 1 . It’s where you explain why your research is worth conducting and its significance to the community, the people, and various institutions.

How To Write Significance of the Study: 5 Steps

Below are the steps and guidelines for writing your research’s Significance of the Study.

1. Use Your Research Problem as a Starting Point

Your problem statement can provide clues to your research study’s outcome and who will benefit from it 2 .

Ask yourself, “How will the answers to my research problem be beneficial?”. In this manner, you will know how valuable it is to conduct your study.

Let’s say your research problem is “What is the level of effectiveness of the lemongrass (Cymbopogon citratus) in lowering the blood glucose level of Swiss mice (Mus musculus)?”

Discovering a positive correlation between the use of lemongrass and lower blood glucose level may lead to the following results:

- Increased public understanding of the plant’s medical properties;

- Higher appreciation of the importance of lemongrass by the community;

- Adoption of lemongrass tea as a cheap, readily available, and natural remedy to lower their blood glucose level.

Once you’ve zeroed in on the general benefits of your study, it’s time to break it down into specific beneficiaries.

2. State How Your Research Will Contribute to the Existing Literature in the Field

Think of the things that were not explored by previous studies. Then, write how your research tackles those unexplored areas. Through this, you can convince your readers that you are studying something new and adding value to the field.

3. Explain How Your Research Will Benefit Society

In this part, tell how your research will impact society. Think of how the results of your study will change something in your community.

For example, in the study about using lemongrass tea to lower blood glucose levels, you may indicate that through your research, the community will realize the significance of lemongrass and other herbal plants. As a result, the community will be encouraged to promote the cultivation and use of medicinal plants.

4. Mention the Specific Persons or Institutions Who Will Benefit From Your Study

Using the same example above, you may indicate that this research’s results will benefit those seeking an alternative supplement to prevent high blood glucose levels.

5. Indicate How Your Study May Help Future Studies in the Field

You must also specifically indicate how your research will be part of the literature of your field and how it will benefit future researchers. In our example above, you may indicate that through the data and analysis your research will provide, future researchers may explore other capabilities of herbal plants in preventing different diseases.

Tips and Warnings

- Think ahead . By visualizing your study in its complete form, it will be easier for you to connect the dots and identify the beneficiaries of your research.

- Write concisely. Make it straightforward, clear, and easy to understand so that the readers will appreciate the benefits of your research. Avoid making it too long and wordy.

- Go from general to specific . Like an inverted pyramid, you start from above by discussing the general contribution of your study and become more specific as you go along. For instance, if your research is about the effect of remote learning setup on the mental health of college students of a specific university , you may start by discussing the benefits of the research to society, to the educational institution, to the learning facilitators, and finally, to the students.

- Seek help . For example, you may ask your research adviser for insights on how your research may contribute to the existing literature. If you ask the right questions, your research adviser can point you in the right direction.

- Revise, revise, revise. Be ready to apply necessary changes to your research on the fly. Unexpected things require adaptability, whether it’s the respondents or variables involved in your study. There’s always room for improvement, so never assume your work is done until you have reached the finish line.

Significance of the Study Examples

This section presents examples of the Significance of the Study using the steps and guidelines presented above.

Example 1: STEM-Related Research

Research Topic: Level of Effectiveness of the Lemongrass ( Cymbopogon citratus ) Tea in Lowering the Blood Glucose Level of Swiss Mice ( Mus musculus ).

Significance of the Study .

This research will provide new insights into the medicinal benefit of lemongrass ( Cymbopogon citratus ), specifically on its hypoglycemic ability.

Through this research, the community will further realize promoting medicinal plants, especially lemongrass, as a preventive measure against various diseases. People and medical institutions may also consider lemongrass tea as an alternative supplement against hyperglycemia.

Moreover, the analysis presented in this study will convey valuable information for future research exploring the medicinal benefits of lemongrass and other medicinal plants.

Example 2: Business and Management-Related Research

Research Topic: A Comparative Analysis of Traditional and Social Media Marketing of Small Clothing Enterprises.

Significance of the Study:

By comparing the two marketing strategies presented by this research, there will be an expansion on the current understanding of the firms on these marketing strategies in terms of cost, acceptability, and sustainability. This study presents these marketing strategies for small clothing enterprises, giving them insights into which method is more appropriate and valuable for them.

Specifically, this research will benefit start-up clothing enterprises in deciding which marketing strategy they should employ. Long-time clothing enterprises may also consider the result of this research to review their current marketing strategy.

Furthermore, a detailed presentation on the comparison of the marketing strategies involved in this research may serve as a tool for further studies to innovate the current method employed in the clothing Industry.

Example 3: Social Science -Related Research.

Research Topic: Divide Et Impera : An Overview of How the Divide-and-Conquer Strategy Prevailed on Philippine Political History.

Significance of the Study :

Through the comprehensive exploration of this study on Philippine political history, the influence of the Divide et Impera, or political decentralization, on the political discernment across the history of the Philippines will be unraveled, emphasized, and scrutinized. Moreover, this research will elucidate how this principle prevailed until the current political theatre of the Philippines.

In this regard, this study will give awareness to society on how this principle might affect the current political context. Moreover, through the analysis made by this study, political entities and institutions will have a new approach to how to deal with this principle by learning about its influence in the past.

In addition, the overview presented in this research will push for new paradigms, which will be helpful for future discussion of the Divide et Impera principle and may lead to a more in-depth analysis.

Example 4: Humanities-Related Research

Research Topic: Effectiveness of Meditation on Reducing the Anxiety Levels of College Students.

Significance of the Study:

This research will provide new perspectives in approaching anxiety issues of college students through meditation.

Specifically, this research will benefit the following:

Community – this study spreads awareness on recognizing anxiety as a mental health concern and how meditation can be a valuable approach to alleviating it.

Academic Institutions and Administrators – through this research, educational institutions and administrators may promote programs and advocacies regarding meditation to help students deal with their anxiety issues.

Mental health advocates – the result of this research will provide valuable information for the advocates to further their campaign on spreading awareness on dealing with various mental health issues, including anxiety, and how to stop stigmatizing those with mental health disorders.

Parents – this research may convince parents to consider programs involving meditation that may help the students deal with their anxiety issues.

Students will benefit directly from this research as its findings may encourage them to consider meditation to lower anxiety levels.

Future researchers – this study covers information involving meditation as an approach to reducing anxiety levels. Thus, the result of this study can be used for future discussions on the capabilities of meditation in alleviating other mental health concerns.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. what is the difference between the significance of the study and the rationale of the study.

Both aim to justify the conduct of the research. However, the Significance of the Study focuses on the specific benefits of your research in the field, society, and various people and institutions. On the other hand, the Rationale of the Study gives context on why the researcher initiated the conduct of the study.

Let’s take the research about the Effectiveness of Meditation in Reducing Anxiety Levels of College Students as an example. Suppose you are writing about the Significance of the Study. In that case, you must explain how your research will help society, the academic institution, and students deal with anxiety issues through meditation. Meanwhile, for the Rationale of the Study, you may state that due to the prevalence of anxiety attacks among college students, you’ve decided to make it the focal point of your research work.

2. What is the difference between Justification and the Significance of the Study?

In Justification, you express the logical reasoning behind the conduct of the study. On the other hand, the Significance of the Study aims to present to your readers the specific benefits your research will contribute to the field you are studying, community, people, and institutions.

Suppose again that your research is about the Effectiveness of Meditation in Reducing the Anxiety Levels of College Students. Suppose you are writing the Significance of the Study. In that case, you may state that your research will provide new insights and evidence regarding meditation’s ability to reduce college students’ anxiety levels. Meanwhile, you may note in the Justification that studies are saying how people used meditation in dealing with their mental health concerns. You may also indicate how meditation is a feasible approach to managing anxiety using the analysis presented by previous literature.

3. How should I start my research’s Significance of the Study section?

– This research will contribute… – The findings of this research… – This study aims to… – This study will provide… – Through the analysis presented in this study… – This study will benefit…

Moreover, you may start the Significance of the Study by elaborating on the contribution of your research in the field you are studying.

4. What is the difference between the Purpose of the Study and the Significance of the Study?

The Purpose of the Study focuses on why your research was conducted, while the Significance of the Study tells how the results of your research will benefit anyone.

Suppose your research is about the Effectiveness of Lemongrass Tea in Lowering the Blood Glucose Level of Swiss Mice . You may include in your Significance of the Study that the research results will provide new information and analysis on the medical ability of lemongrass to solve hyperglycemia. Meanwhile, you may include in your Purpose of the Study that your research wants to provide a cheaper and natural way to lower blood glucose levels since commercial supplements are expensive.

5. What is the Significance of the Study in Tagalog?

In Filipino research, the Significance of the Study is referred to as Kahalagahan ng Pag-aaral.

- Draft your Significance of the Study. Retrieved 18 April 2021, from http://dissertationedd.usc.edu/draft-your-significance-of-the-study.html

- Regoniel, P. (2015). Two Tips on How to Write the Significance of the Study. Retrieved 18 April 2021, from https://simplyeducate.me/2015/02/09/significance-of-the-study/

Written by Jewel Kyle Fabula

in Career and Education , Juander How

Jewel Kyle Fabula

Jewel Kyle Fabula is a Bachelor of Science in Economics student at the University of the Philippines Diliman. His passion for learning mathematics developed as he competed in some mathematics competitions during his Junior High School years. He loves cats, playing video games, and listening to music.

Browse all articles written by Jewel Kyle Fabula

Copyright Notice

All materials contained on this site are protected by the Republic of the Philippines copyright law and may not be reproduced, distributed, transmitted, displayed, published, or broadcast without the prior written permission of filipiknow.net or in the case of third party materials, the owner of that content. You may not alter or remove any trademark, copyright, or other notice from copies of the content. Be warned that we have already reported and helped terminate several websites and YouTube channels for blatantly stealing our content. If you wish to use filipiknow.net content for commercial purposes, such as for content syndication, etc., please contact us at legal(at)filipiknow(dot)net

Community Blog

Keep up-to-date on postgraduate related issues with our quick reads written by students, postdocs, professors and industry leaders.

What is the Significance of the Study?

- By DiscoverPhDs

- August 25, 2020

- what the significance of the study means,

- why it’s important to include in your research work,

- where you would include it in your paper, thesis or dissertation,

- how you write one

- and finally an example of a well written section about the significance of the study.

What does Significance of the Study mean?

The significance of the study is a written statement that explains why your research was needed. It’s a justification of the importance of your work and impact it has on your research field, it’s contribution to new knowledge and how others will benefit from it.

Why is the Significance of the Study important?

The significance of the study, also known as the rationale of the study, is important to convey to the reader why the research work was important. This may be an academic reviewer assessing your manuscript under peer-review, an examiner reading your PhD thesis, a funder reading your grant application or another research group reading your published journal paper. Your academic writing should make clear to the reader what the significance of the research that you performed was, the contribution you made and the benefits of it.

How do you write the Significance of the Study?

When writing this section, first think about where the gaps in knowledge are in your research field. What are the areas that are poorly understood with little or no previously published literature? Or what topics have others previously published on that still require further work. This is often referred to as the problem statement.

The introduction section within the significance of the study should include you writing the problem statement and explaining to the reader where the gap in literature is.

Then think about the significance of your research and thesis study from two perspectives: (1) what is the general contribution of your research on your field and (2) what specific contribution have you made to the knowledge and who does this benefit the most.

For example, the gap in knowledge may be that the benefits of dumbbell exercises for patients recovering from a broken arm are not fully understood. You may have performed a study investigating the impact of dumbbell training in patients with fractures versus those that did not perform dumbbell exercises and shown there to be a benefit in their use. The broad significance of the study would be the improvement in the understanding of effective physiotherapy methods. Your specific contribution has been to show a significant improvement in the rate of recovery in patients with broken arms when performing certain dumbbell exercise routines.

This statement should be no more than 500 words in length when written for a thesis. Within a research paper, the statement should be shorter and around 200 words at most.

Significance of the Study: An example

Building on the above hypothetical academic study, the following is an example of a full statement of the significance of the study for you to consider when writing your own. Keep in mind though that there’s no single way of writing the perfect significance statement and it may well depend on the subject area and the study content.

Here’s another example to help demonstrate how a significance of the study can also be applied to non-technical fields:

The significance of this research lies in its potential to inform clinical practices and patient counseling. By understanding the psychological outcomes associated with non-surgical facial aesthetics, practitioners can better guide their patients in making informed decisions about their treatment plans. Additionally, this study contributes to the body of academic knowledge by providing empirical evidence on the effects of these cosmetic procedures, which have been largely anecdotal up to this point.

The statement of the significance of the study is used by students and researchers in academic writing to convey the importance of the research performed; this section is written at the end of the introduction and should describe the specific contribution made and who it benefits.

A well written figure legend will explain exactly what a figure means without having to refer to the main text. Our guide explains how to write one.

The term research instrument refers to any tool that you may use to collect, measure and analyse research data.

The purpose of research is to enhance society by advancing knowledge through developing scientific theories, concepts and ideas – find out more on what this involves.

Join thousands of other students and stay up to date with the latest PhD programmes, funding opportunities and advice.

Browse PhDs Now

The title page of your dissertation or thesis conveys all the essential details about your project. This guide helps you format it in the correct way.

Find out the differences between a Literature Review and an Annotated Bibliography, whey they should be used and how to write them.

Akshay is in the final year of his PhD researching how well models can predict Indian monsoon low-pressure systems. The results of his research will help improve disaster preparedness and long-term planning.

Dr Jadavji completed her PhD in Medical Genetics & Neuroscience from McGill University, Montreal, Canada in 2012. She is now an assistant professor involved in a mix of research, teaching and service projects.

Join Thousands of Students

Instantly enhance your writing in real-time while you type. With LanguageTool

Get started for free

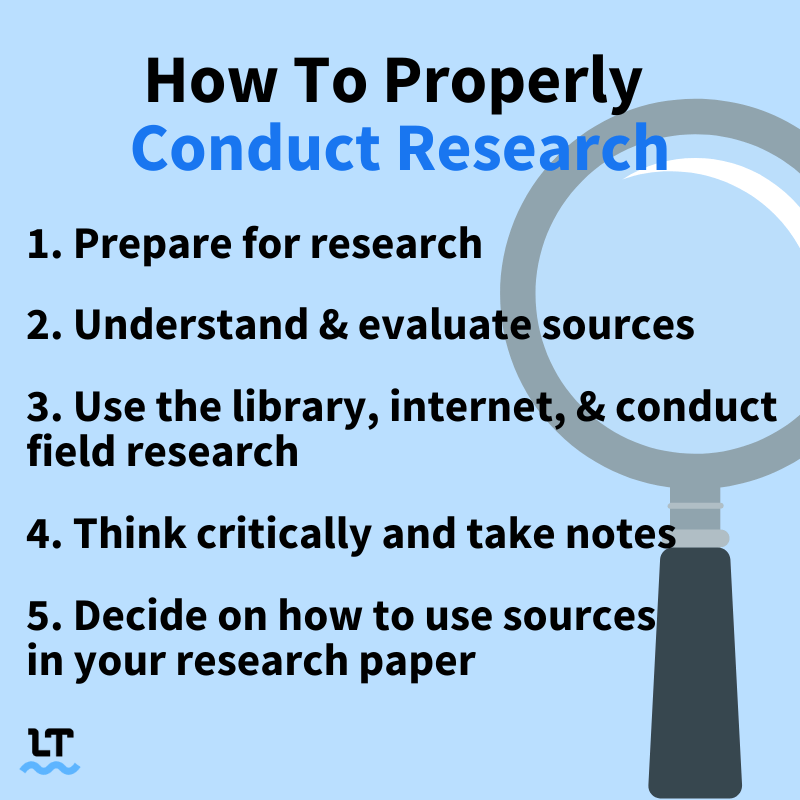

How to Properly and Effectively Conduct Research in Five Steps

Researching is a valuable skill that can help you in school, work, and beyond. This blog post breaks down the research process into five easy-to-follow steps to teach you how to conduct research properly and effectively.

Conducting Research: Table of Contents

What is Research?

Steps to Conducting Research

In an age where misinformation is rampant, knowing how to correctly conduct research is a skill that will set you apart from others. This blog post goes over what research is and breaks down the process into five straightforward steps.

What Is Research?

The word research is derived from the Middle French word “recerche,” which means “to seek.” That term came from the Old French word “recerchier,” meaning “search.” But what exactly is being sought during research? Knowledge and information.

Research is the methodical process of collecting and analyzing data to expand your knowledge, so you can have enough information to answer a question or describe, explain, or predict an issue or observation.

Research is important because it helps you see the world as it really is (facts) and not as you or others think it is (opinions).

The meaning of research may sound quite heavy and significant, but that’s because it is. Proper research guides you to weed out wrong information. Today, having that skill is vital. Below, we’ll teach you how to do research in five easy-to-follow steps.

It’s essential to note that there are different types of research:

- Exploratory research identifies a problem or question.

- Constructive research examines hypotheses and offers solutions.

- Empirical research tests the feasibility of a solution using data.

That being said, the research process may differ based on the purpose of the project. Take the measures below as a general guideline, and be prepared to make changes or take additional steps.

Also, keep in mind that conducting proper research is not easy. You should start with a mindset of being ready to use a lot of time and effort to obtain the information you need.

1. Prepare for Research

Preparing for research is an extensive step in itself. You must:

- Choose a topic or carefully analyze the assignment given to you.

- Craft a research question and hypothesis.

- Plan out your research.

- Create a research log.

- Transform your hypothesis into a working thesis.

2. Understand and Evaluate Sources

Once you have meticulously prepared for research, you should have a thorough understanding of the different types of sources. Doing this helps you learn which types would best fit your research project.

- Primary sources provide direct knowledge and evidence based on your research question.

- Secondary sources provide descriptions or interpretations of primary sources.

- Tertiary sources provide summaries of the primary or secondary sources without providing additional insights.

The data and information you’re seeking can be found in various mediums. The following list shows the types most commonly used in academic research and writing:

- Academic journals

- Books and textbooks

- Government and legal documents

The information you need doesn’t always have to come in the form of printed materials. It can also be found in:

- Multimedia (like radio and television podcasts, or recorded public meetings)

- Social media

Evaluate Your Sources

You must evaluate your sources to ensure that they are credible and authoritative. The information you find on websites, blogs, and social media is not as reliable as that found in academic journals, for example. Always verify the information you find, and then verify again!

To evaluate sources, you should:

- Find out as much as you can about the source

- Determine the intended audience

- Ask yourself if it is fact, opinion, or propaganda

- Analyze the evidence used

- Check how timely the source is

- Cross-check the information

3. Use the Library, Internet, and Conduct Field Research

So, where can you find all these sources? The library is a good place to start because the library staff may be able to guide you in the right direction as to where you should begin your research. If you’re a student, your school library can provide access to:

- Reference works

- Encyclopedias

- Almanacs and atlases

- Catalogs and databases

- And countless books

The internet does provide easy and fast access to all sorts of data, including incorrect information. That’s why it’s important to verify everything you find there. However, the internet is also home to reliable and credible information.

You can find trustworthy sources online, including scholarly works on Google Scholar , for example. Government sites, like the Library of Congress, provide online collections of articles. There are also many websites for reputable publications, such as the New York Times . Make sure to include the latest information on the specific topic.

Lastly, you can also conduct research by collecting data yourself. You can do this in the form of interviews, observations, opinion surveys, and more.

Don’t Forget

Update your working bibliography as you conduct your research, and keep track of everything in your research log!

4. Think Critically and Takes Notes

When you’re researching, it’s important to read everything through a critical lens—don’t just accept what you see at face value. Always ask yourself questions like:

What’s the main idea?

What are the supporting ideas?

Who is the intended audience?

What’s the purpose?

Is there anything else I need to know that was left out?

Take as many notes as you can and look up anything confusing or unclear.

5. Decide on How To Integrate Sources Into Your Research Paper

Now that you have all the information you need, it’s time to figure out how you are going to integrate sources into your research paper.

Are you going to quote your sources directly? Doing so can help you establish credibility, but be sure to limit this, as your research paper should be mainly your ideas and findings (based on theoretical framework). You can also paraphrase or summarize your sources, but make sure to precede them with the author of the source.

If you’re using visuals in your research project, make sure to include them seamlessly. Ensure that there’s a purpose for the visual content (it can demonstrate something better than words alone can). Add the visual immediately after an explanation of it, and take some time to clarify why it’s relevant to the research project.

The most important part of this step is that you do not plagiarize! Always cite your sources. The only information that need not be cited is:

- Common knowledge

- Your findings from field research

Research Takes Time

The truth is that if you want to conduct proper research, you must be willing to dedicate a significant amount of time to it. And properly conducted research is essential to a well-written and credible research paper.

In other words, there are no cutting corners when it comes to research. However, as an advanced, multilingual writing assistant, LanguageTool can take care of the grammar, spelling, and punctuation aspects of your research project. It can help you in paraphrasing sentences to align with the formality required for an academic paper while also ensuring simplicity, conciseness, and fluency when necessary.

LanguageTool lets you focus on the most important aspects of writing a research paper—research and writing—while it focuses on correcting all types of errors. Its advanced technology can also help you avoid plagiarism through paraphrasing. In this case, it’s imperative that if you use this feature, you still include the source in the references or works cited page.

LanguageTool is free to use! Give it a try.

Lunsford, Andrea A. The Everyday Writer with Exercises , 2010.

Types of Sources - Purdue OWL® - Purdue University. “Types of Sources - Purdue OWL® - Purdue University,” n.d. https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/research_and_citation/conducting_research/research_overview/sources.html.

General Guidelines - Purdue OWL® - Purdue University. “General Guidelines - Purdue OWL® - Purdue University,” n.d. https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/research_and_citation/conducting_research/evaluating_sources_of_information/general_guidelines.html.

Ryan, Eoghan. “Types of Sources Explained | Examples & Tips.” Scribbr, May 19, 2022. https://www.scribbr.com/working-with-sources/types-of-sources/.

Unleash the Professional Writer in You With LanguageTool

Go well beyond grammar and spell checking. Impress with clear, precise, and stylistically flawless writing instead.

Works on All Your Favorite Services

- Thunderbird

- Google Docs

- Microsoft Word

- Open Office

- Libre Office

We Value Your Feedback

We’ve made a mistake, forgotten about an important detail, or haven’t managed to get the point across? Let’s help each other to perfect our writing.

- Link to facebook

- Link to linkedin

- Link to twitter

- Link to youtube

- Writing Tips

How to Discuss the Significance of Your Research

- 6-minute read

- 10th April 2023

Introduction

Research papers can be a real headache for college students . As a student, your research needs to be credible enough to support your thesis statement. You must also ensure you’ve discussed the literature review, findings, and results.

However, it’s also important to discuss the significance of your research . Your potential audience will care deeply about this. It will also help you conduct your research. By knowing the impact of your research, you’ll understand what important questions to answer.

If you’d like to know more about the impact of your research, read on! We’ll talk about why it’s important and how to discuss it in your paper.

What Is the Significance of Research?

This is the potential impact of your research on the field of study. It includes contributions from new knowledge from the research and those who would benefit from it. You should present this before conducting research, so you need to be aware of current issues associated with the thesis before discussing the significance of the research.

Why Does the Significance of Research Matter?

Potential readers need to know why your research is worth pursuing. Discussing the significance of research answers the following questions:

● Why should people read your research paper ?

● How will your research contribute to the current knowledge related to your topic?

● What potential impact will it have on the community and professionals in the field?

Not including the significance of research in your paper would be like a knight trying to fight a dragon without weapons.

Where Do I Discuss the Significance of Research in My Paper?

As previously mentioned, the significance of research comes before you conduct it. Therefore, you should discuss the significance of your research in the Introduction section. Your reader should know the problem statement and hypothesis beforehand.

Steps to Discussing the Significance of Your Research

Discussing the significance of research might seem like a loaded question, so we’ve outlined some steps to help you tackle it.

Step 1: The Research Problem