Career Paths

- Mar 6, 2024

- 11 min read

How to Become a Researcher (Duties, Salary and Steps)

You could uncover the next big thing in our lives.

Mike Dalley

HR and Learning & Development Expert

Reviewed by Chris Leitch

Everything important in our day-to-day life started as a groundbreaking piece of research.

Researchers make ideas come to life, and all of the things that we take for granted wouldn’t be here without research. Therefore, being a researcher offers a rewarding, challenging and varied career path .

This article takes you through the details of being a researcher, including what this exciting role entails, what the working environment and salary are like and, critically, what you can do to get started in the role.

What is a researcher?

A researcher collects data and undertakes investigations into a particular subject , publishing their findings. The purpose of this is to uncover new knowledge or theories. Researchers typically specialize in a particular field and follow rigorous methodologies in order to ensure their research is credible.

What are the different types of researchers?

There are many ways to categorize researchers, such as by their field, expertise or methodologies. Here are six basic types of researchers:

- Applied researchers use existing scientific knowledge to solve problems . They use this knowledge to develop new technologies or methodologies.

- Clinical researchers conduct research related to medical treatments or diseases. They often work in institutions like hospitals or pharmaceutical companies.

- Corporate researchers collect data related to business environments, with the aim to use this to benefit organizations.

- Market researchers gather data related to consumer preferences or an organization’s competitors.

- Social researchers investigate human behavior and the factors influencing this. Social research relates to fields like psychology , anthropology and economics.

- Policy researchers work with companies and governments to investigate the impact of policies, regulations or programs.

What does a researcher do?

Researcher work is quite varied. It begins with reviewing existing research and literature and formulating research questions . Researchers also have to design studies and protocols for their research, and diligently and thoroughly collect data.

Once the data is collected, researchers have to critically analyze their findings and communicate them . To ensure the research is reliable, researchers must embrace peer review , where their research is evaluated by other researchers in the same field, and draw conclusions accordingly. The entirety of this process must be bound by ethical considerations, as researchers have a duty to ensure their work is truthful, integral and accurate.

Researchers also undertake supportive duties, such as applying for grants and funding, and investigating new areas to research.

What is their work environment?

Researchers’ work environment depends greatly on the type of research they are doing and their field. The typical researcher environment can, therefore, vary considerably but might include time in laboratories, academic institutions, office spaces and IT workshops. There might also be the need to undergo onsite fieldwork or attend conferences and workshops.

Researchers work in collaborative environments, and teamwork is common. That said, they also need to undertake plenty of solo work that requires concentration and quiet. Consequently, they need to be happy in a variety of different work settings.

How many hours do they work?

The hours researchers work vary just as much as their working environment. Freelance or contract researchers might work atypical hours, whereas academic or corporate researchers might work more standard hours, such as a 40-hour working week.

Field researchers might have to work longer hours at times in order to collect data. This also might involve travel time.

All researchers might have to work long hours when deadlines are due, or when projects are time-sensitive. Finally, because of the idiosyncratic nature of research work, all researchers might have their favorite personal working style and work their hours in preferred patterns.

How much do they earn?

Owing to the nature of the role, researcher salaries can vary considerably. Based on current market data , the average salary is $82,276 per year .

One of the largest variables in researcher salaries is the field you decide to go into. Academic researchers are typically paid towards the lower end of the scale, as are government researchers. Industry or corporate researchers are paid a lot more, with computer and information research roles paying a median annual salary of over $130,000.

Researcher salaries can also vary based on the job level. Apprentices or research assistants have lower salaries, whereas research scientist or professor-level roles often pay over $100,000. Pay scales are connected to academic reputation, industry credentials, and the industry you work in. This also means that as your career in research progresses, you can expect to take home extremely good paychecks.

What is the job market like for researchers?

Some research roles can be extremely competitive, with tenure-track roles in academic research being highly in demand, as are positions in consulting firms. The labor market for corporate research and governmental research roles can also be very strong, but research is heavily impacted by economic conditions, and roles can be cut in times of recession.

In general, research roles are highly sought-after , and this means competition for them is fierce. This means that you need to have a strong network, undergo continuous professional development, work on your research portfolio, and ensure your résumé and other supporting documentation are up to date.

What are the entry requirements?

Starting your career as a researcher requires plenty of preparation. Here’s what you need to focus on in terms of education, skills and knowledge, and licensing and certification.

Higher education is essential to become a researcher; what degree you choose might depend on what field of research you are interested in. A bachelor’s degree will give you foundational knowledge , whereas a master’s or PhD offers more specialized knowledge and can lead to more career opportunities later in your career journey.

Skills and knowledge

Entry-level researchers need a rich mix of skills and knowledge to be able to fulfil their job duties . Skills to develop include analytical skills , critical thinking ability and solving problems, with other useful ones being IT and presentation skills . Knowledge of research methodologies and rationale, as well as database management, is very useful.

Licensing and certification

Licensing and certification requirements for researchers vary , depending on the field you are planning to go into. Academic credentials, as outlined above, are important, but being a member of relevant professional associations is also highly advised.

Some sensitive areas of research might require you to have specialist credentials, such as certification in Good Clinical Practice if you’re planning to undertake medical research.

Do you have what it takes?

Being a researcher is a labor of love. If your values, passions and talent are related to traits like curiosity, attention to detail, discovering more about the world we live in, and rigorous attention to detail, then being a researcher is the perfect job for you. You also have to have a lot of patience, honesty when it comes to reporting unwelcome results, and resilience.

If you’re not sure what kind of career your skills, interests and passions might lead to, then consider taking CareerHunter’s six-stage assessment . These tests have been developed by psychologists and assess your skills and interests in order to provide you with best-fit careers that you can really thrive in.

How to become a researcher

A lot of preparation is needed to become a researcher. If, after reading this far, you still feel that becoming a researcher is the perfect job for you, then read on to discover how you can make this career dream a reality.

Step 1: Choose your field

Try to choose your research field as soon as you can. This is important, because it might provide you with direction for your higher education. There are so many different research fields to choose from — for example: social sciences, humanities, business, healthcare, engineering , or simply focusing on research theory or methodologies.

It’s important to choose a field that you have a strong interest or passion in. Also, consider where your talents and skills lie, and let this guide your decision too.

Step 2: Get qualified

As we’ve covered already, education is an important first step to becoming a researcher.

Common degrees to focus on can be the sciences (biology, chemistry or physics), computer science , mathematics, or statistics . Alternatively, if you have decided on your chosen research field, then consider obtaining higher education that relates to this.

Being a researcher is a competitive career: good grades in leading institutions will be required if you want to work as a researcher in prestigious organizations.

Step 3: Develop your research skills

Whether it’s part of your higher education or simply learning in your own time, developing research skills such as new methodologies, quantitative and qualitative methods , strategic analysis, or data analytics will keep you professionally competitive.

Additionally, it’s useful to gain experience in using research tools and software. These can include statistics software like SPSS, as well as programming languages like Java and Python. Understanding data visualization and presentation tools can also be hugely helpful.

Step 4: Gain research experience

A great way to start your career as a researcher is to undertake undergraduate research. This could be your own independent research project but is most commonly achieved through research internships or assistantships . With these experiences, you can collaborate with academic leaders, mentors or established researchers on their projects, and learn from their experience and expertise as well.

Another way to gain experience is through volunteering in research-related roles in academic institutions, laboratories or other similar environments.

Step 5: Network with peers

Networking with fellow research professionals enables you to exchange ideas, resources and expertise . Your network might be able to support you in finding research positions as your career progresses.

Grow your network by attending conferences and seminars, and by leveraging your work experience. You can also grow your network by reaching out to researchers on LinkedIn, and by publishing your own research papers as your experience grows.

Step 6: Present and publish your work

Presenting your work and publishing your findings establishes and grows your credibility as a researcher. You can present your research at conferences or even online via websites like YouTube.

Being published or listed as a collaborator on research papers can impact your career hugely , and being featured on important or large-scale research works can truly establish you as a researcher and lead to larger projects or more funding.

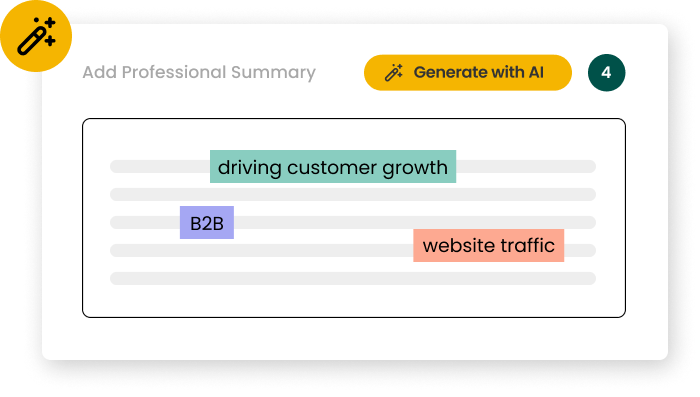

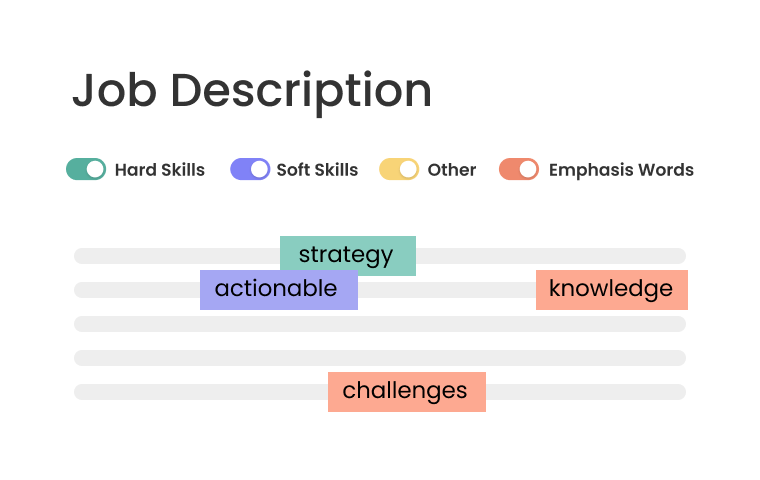

Step 7: Develop your résumé

Ensure that your résumé links to your portfolio of published works , as well as your presentations. It should showcase to potential employers and academic institutions what you have done, and what you’re capable of doing.

Ensure your résumé also references your research skills in a way that relates to the reader, and that it can be parsed effectively in applicant tracking systems .

Step 8: Seek funding

Research requires time and money. By applying for research grants, fellowships, scholarships and projects, you’ll grow your experience and leverage your credibility . Many of these opportunities are competitive, and being able to showcase what you can achieve via your published work, portfolio or résumé is essential.

Applying for funding is a skill in itself, as researchers need to be able to write compelling and thorough applications. You’ll also need to use negotiating and influencing skills in order to secure the funding and get your projects off the ground.

Step 9: Apply for research jobs

Whereas being a researcher often means that you’re working on independent projects, freelancing, or affiliated with an academic institution rather than being employed by one, there are plenty of research jobs out there — and lots of companies have their own in-house research teams.

If you apply for these roles, ensure that your résumé is up to date and that you practice your interviewing skills for them. Research jobs are in demand, and being able to showcase what you do is essential for success.

Step 10: Never stop discovering

Being a successful researcher isn’t just about continuous learning; it’s about endless discovery as well. The best researchers stay curious about their field , exploring new research questions, learning and growing from failure, and asking new questions.

Researchers are passionate about discovery and believe that learning new things and overcoming challenges makes the world a better place. Enthusiastically discovering new things will also ensure that your career as a researcher keeps growing. You’ll also develop resilience and persistence, which are powerful skills to have.

Final thoughts

Being a researcher requires a lot of skills and knowledge, as well as you taking time to figure out exactly what kind of research you want to get involved with. The job is complex and detailed, and can be as frustrating as it can be rewarding.

Becoming a leading researcher requires a lot of career preparation, and hopefully this article can point you in the right direction if you feel this is the perfect job for you. Once you get started, choose your research projects carefully, and who knows? You could be the researcher that uncovers the next big thing in our lives!

Are you thinking about becoming a researcher, or want to share your experiences? Let us know in the comments section below.

Career Exploration

- Assistant Professor / Lecturer

- PhD Candidate

- Senior Researcher / Group Leader

- Researcher / Analyst

- Research Assistant / Technician

- Administration

- Executive / Senior Industry Position

- Mid-Level Industry Position

- Junior Industry Position

- Graduate / Traineeship

- Remote/Hybrid Jobs

- Summer / Winter Schools

- Online Courses

- Professional Training

- Supplementary Courses

- All Courses

- PhD Programs

- Master's Programs

- MBA Programs

- Bachelor's Programs

- Online Programs

- All Programs

- Fellowships

- Postgraduate Scholarships

- Undergraduate Scholarships

- Prizes & Contests

- Financial Aid

- Research/Project Funding

- Other Funding

- All Scholarships

- Conferences

- Exhibitions / Fairs

- Online/Hybrid Conferences

- All Conferences

- Economics Terms A-Z

- Career Advice

- Study Advice

- Work Abroad

- Study Abroad

- Campus Reviews

- Recruiter Advice

- Study Guides - For Students

- Educator Resource Packs

- All Study-Guides

- University / College

- Graduate / Business School

- Research Institute

- Bank / Central Bank

- Private Company / Industry

- Consulting / Legal Firm

- Association / NGO

- All EconDirectory

- 📖 INOMICS Handbook

All Categories

All disciplines.

- Scholarships

- Teaching Advice Articles

- INOMICS Educator Resources

- INOMICS Academy

- INOMICS Study Guides

- All Economics Terms A-Z

- EconDirectory

- All 📖 INOMICS Handbook

Weighing Up the Options

The pros and cons of a career in research.

Read a summary or generate practice questions using the INOMICS AI tool

Soon after the completion of a Master's degree or PhD , everybody is faced with the big question: what next? Although it may seem like a natural progression to continue with further research, there are many other careers open to academics in business, education, communications and journalism, to name but a few examples.

So how do you know if research is the right career choice for you? Well, like with most big decisions, a good way of figuring it out is to weigh the pros and cons of an academic career.

Travel and relocation

One big difference between a career in research and most other fields is the expectation of relocation. The first step for a Master's student or PhD who wants a career in research is to find a position at a university in a town, city or country where they are willing to relocate. It is typical for researchers to move to a new city or country every few years, particularly when pursuing postdoc positions. This is the natural consequence of there not being very many jobs to go around.

Pro: Moving around does have its advantages - it is a unique opportunity to travel to new places and experience life in different countries and cultures. One can meet new people and obtain contacts, both of which are extremely rewarding.

Furthermore, moving offers the valuable experience of working at various institutions, which can give insight into how cultures vary across universities. Being part of an institution like a university provides you a pre-existing network to explore, both professionally and socially, which can make settling down in a new region or country a whole lot easier.

Con: Arranging an international relocation is a lot of work, and it can be hard to make new friends and create a social circle in a new city. Moreover, relocating can be stressful on the mind, causing some to struggle, so having adequate support for a move is essential.

Particularly for those with families, relocation may be demanding for other reasons- your partner may also need a job in your new city and new schools need to be found for children, which can be a challenge. If your partner is also in research, some institutions offer dual career programs which help find research positions for both members of a couple.

Independence and interest

Pro: One great advantage of a career in research is how interesting the work is, and the independence one is afforded. If you are able to secure third-party funding, you can organize your own working schedule and priorities, and choose the topics of research which are of most pressing interest to you.

Within many research institutions there is also the possibility of flexible working hours, which can be especially advantageous to those with young children.

Security and career prospects

Con: One particularly difficult aspect of a research career is the lack of job security. Postdocs are typically employed on short-term contracts for two years, and at the end of this period they must find another position. For the ambitious and determined researcher, this can be an opportunity for fast career progression and the chance to work in a variety of labs.

However, this insecurity can be a source of stress for many researchers as there is no guarantee of long-term stable employment. Progressing from a postdoctoral position to a professorship can be extremely competitive, and the number of professor positions can be reduced due to budget cuts, so in tough times there will be even fewer openings available.

Overall, many more PhDs and postdocs are working than there are professorships available, so you must be extremely determined to follow this path.

Transferable skills

Pro: Although the competition for academic positions is so fierce that a career in research may seem risky, in fact the skills one acquires in the performance of research can be transferred to many other fields. Critical thinking skills are highly developed in researchers.

Besides these, researchers may acquire expertise in mathematics or statistics, in written communication, or in poster and oral presentation. All of these skills can be put to use in other jobs, so if a research position is not available, then you still have other career options open to you.

Whether a career in academia is for you or not will depend entirely on your own levels of determination and persistence, along with weighing the pros against the cons of research. In the end, only you can make the choice - but keep in mind the various advantages and disadvantages of going down this particular career path.

Currently trending in Russia

- PhD Program

- Posted 4 months ago

Graduate Program in Economics and Finance (GPEF) - Fully funded Ph.D. Positions

- Workshop, Conference

- Posted 2 weeks ago

20th Edition International Conference on Applied Business & Economics

- Posted 1 week ago

36th RSEP International Conference on Economics, Finance and Business

Related Items

Call for Research Projects 2024 “Women and Science”

MSc Economics and Finance

PhD in Economics - University of Torino

Featured announcements, cims online summer schools: foundations of dsge macro modelling and…, difference-in-differences and event studies for panel data and…, doctoral programme in economics (mres+phd), mitarbeiter*innen für die banken- und finanzaufsicht, monitoring and forecasting macroeconomic and financial risk: sofie…, upcoming deadlines.

- Jun 30, 2024 MSc/PhD in Quantitative Economics - University of Alicante

- Jun 30, 2024 Monitoring and Forecasting Macroeconomic and Financial Risk: SoFiE European Summer School (Brussels)

- Jun 30, 2024 Master in Monetary and Financial Economics - University of Cyprus

- Jun 30, 2024 MSc/PhD in Economics (IDEA) - Barcelona

- Jul 01, 2024 Doctoral programme in Economics (MRes+PhD)

INOMICS AI Tools

The INOMICS AI can generate an article summary or practice questions related to the content of this article. Try it now!

An error occured

Please try again later.

3 Practical questions, generated by our AI model

For more questions on economics study topics, with practice quizzes and detailed answer explanations, check out the INOMICS Study Guides.

Login to your account

Email Address

Forgot your password? Click here.

Clinical Researcher

Navigating a Career as a Clinical Research Professional: Where to Begin?

Clinical Researcher June 9, 2020

Clinical Researcher—June 2020 (Volume 34, Issue 6)

PEER REVIEWED

Bridget Kesling, MACPR; Carolynn Jones, DNP, MSPH, RN, FAAN; Jessica Fritter, MACPR; Marjorie V. Neidecker, PhD, MEng, RN, CCRP

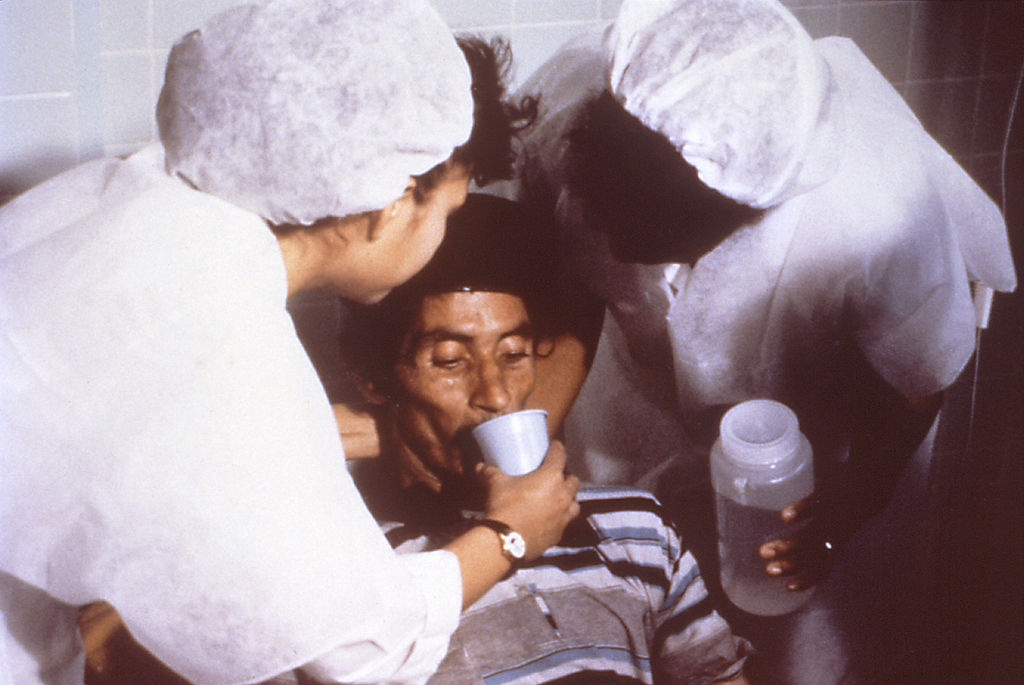

Those seeking an initial career in clinical research often ask how they can “get a start” in the field. Some clinical research professionals may not have heard about clinical research careers until they landed that first job. Individuals sometimes report that they have entered the field “accidentally” and were not previously prepared. Those trying to enter the clinical research field lament that it is hard to “get your foot in the door,” even for entry-level jobs and even if you have clinical research education. An understanding of how individuals enter the field can be beneficial to newcomers who are targeting clinical research as a future career path, including those novices who are in an academic program for clinical research professionals.

We designed a survey to solicit information from students and alumni of an online academic clinical research graduate program offered by a large public university. The purpose of the survey was to gain information about how individuals have entered the field of clinical research; to identify facilitators and barriers of entering the field, including advice from seasoned practitioners; and to share the collected data with individuals who wanted to better understand employment prospects in clinical research.

Core competencies established and adopted for clinical research professionals in recent years have informed their training and education curricula and serve as a basis for evaluating and progressing in the major roles associated with the clinical research enterprise.{1,2} Further, entire academic programs have emerged to provide degree options for clinical research,{3,4} and academic research sites are focusing on standardized job descriptions.

For instance, Duke University re-structured its multiple clinical research job descriptions to streamline job titles and progression pathways using a competency-based, tiered approach. This led to advancement pathways and impacted institutional turnover rates in relevant research-related positions.{5,6} Other large clinical research sites or contract research organizations (CROs) have structured their onboarding and training according to clinical research core competencies. Indeed, major professional organizations and U.S. National Institutes of Health initiatives have adopted the Joint Task Force for Clinical Trial Competency as the gold standard approach to organizing training and certification.{7,8}

Recent research has revealed that academic medical centers, which employ a large number of clinical research professionals, are suffering from high staff turnover rates in this arena, with issues such as uncertainty of the job, dissatisfaction with training, and unclear professional development and role progression pathways being reported as culprits in this turnover.{9} Further, CROs report a significant shortage of clinical research associate (CRA) personnel.{10} Therefore, addressing factors that would help novices gain initial jobs would address an important workforce gap.

This mixed-methods survey study was initiated by a student of a clinical research graduate program at a large Midwest university who wanted to know how to find her first job in clinical research. Current students and alumni of the graduate program were invited to participate in an internet-based survey in the fall semester of 2018 via e-mails sent through the program listservs of current and graduated students from the program’s lead faculty. After the initial e-mail, two reminders were sent to prospective participants.

The survey specifically targeted students or alumni who had worked in clinical research. We purposefully avoided those students with no previous clinical research work experience, since they would not be able to discuss their pathway into the field. We collected basic demographic information, student’s enrollment status, information about their first clinical research position (including how it was attained), and narrative information to describe their professional progression in clinical research. Additional information was solicited about professional organization membership and certification, and about the impact of graduate education on the acquisition of clinical research jobs and/or role progression.

The survey was designed so that all data gathered (from both objective responses and open-ended responses) were anonymous. The survey was designed using the internet survey instrument Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap), which is a secure, web-based application designed to support data capture for research studies. REDCap provides an intuitive interface for validated data entry; audit trails for tracking data manipulation and export procedures; automated export procedures for seamless data downloads to common statistical packages; and procedures for importing data from external sources.{11}

Data were exported to Excel files and summary data were used to describe results. Three questions solicited open-ended responses about how individuals learned about clinical research career options, how they obtained their first job, and their advice to novices seeking their first job in clinical research. Qualitative methods were used to identify themes from text responses. The project was submitted to the university’s institutional review board and was classified as exempt from requiring board oversight.

A total of 215 survey invitations were sent out to 90 current students and 125 graduates. Five surveys were returned as undeliverable. A total of 48 surveys (22.9%) were completed. Because the survey was designed to collect information from those who were working or have worked in clinical research, those individuals (n=5) who reported (in the first question) that they had never worked in clinical research were eliminated. After those adjustments, the total number completed surveys was 43 (a 20.5% completion rate).

The median age of the participants was 27 (range 22 to 59). The majority of respondents (89%) reported being currently employed as clinical research professionals and 80% were working in clinical research at the time of graduate program entry. The remaining respondents had worked in clinical research in the past. Collectively, participants’ clinical research experience ranged from less than one to 27 years.

Research assistant (20.9%) and clinical research coordinator (16.3%) were the most common first clinical research roles reported. However, a wide range of job titles were also reported. When comparing entry-level job titles of participants to their current job title, 28 (74%) respondents reported a higher level job title currently, compared to 10 (26%) who still had the same job title.

Twenty-four (65%) respondents were currently working at an academic medical center, with the remaining working with community medical centers or private practices (n=3); site management organizations or CROs (n=2); pharmaceutical or device companies (n=4); or the federal government (n=1).

Three respondents (8%) indicated that their employer used individualized development plans to aid in planning for professional advancement. We also asked if their current employer provided opportunities for professional growth and advancement. Among academic medical center respondents, 16 (67%) indicated in the affirmative. Respondents also affirmed growth opportunities in other employment settings, with the exception of one respondent working in government and one respondent working in a community medical center.

Twenty-five respondents indicated membership to a professional association, and of those, 60% reported being certified by either the Association of Clinical Research Professionals (ACRP) or the Society of Clinical Research Associates (SoCRA).

Open-Ended Responses

We asked three open-ended questions to gain personal perspectives of respondents about how they chose clinical research as a career, how they entered the field, and their advice for novices entering the profession. Participants typed narrative responses.

“Why did you decide to pursue a career in clinical research?”

This question was asked to find out how individuals made the decision to initially consider clinical research as a career. Only one person in the survey had exposure to clinical research as a career option in high school, and three learned about such career options as college undergraduates. One participant worked in clinical research as a transition to medical school, two as a transition to a doctoral degree program, and two with the desire to move from a bench (basic science) career to a clinical research career.

After college, individuals either happened across clinical research as a career “by accident” or through people they met. Some participants expressed that they found clinical research careers interesting (n=6) and provided an opportunity to contribute to patients or improvements in healthcare (n=7).

“How did you find out about your first job in clinical research?”

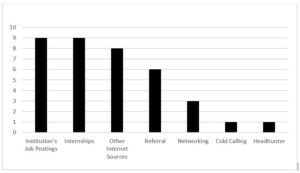

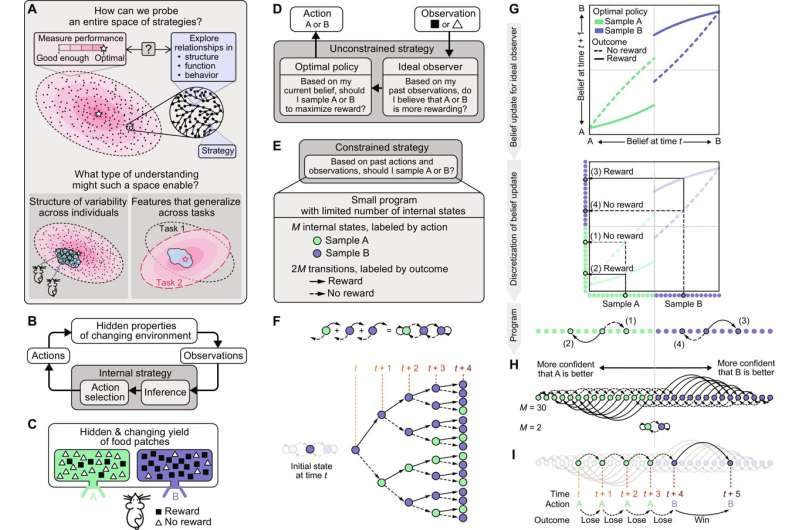

Qualitative responses were solicited to obtain information on how participants found their first jobs in clinical research. The major themes that were revealed are sorted in Figure 1.

Figure 1: How First Jobs in Clinical Research Were Found

Some reported finding their initial job through an institution’s job posting.

“I worked in the hospital in the clinical lab. I heard of the opening after I earned my bachelor’s and applied.”

Others reported finding about their clinical research position through the internet. Several did not know about clinical research roles before exploring a job posting.

“In reviewing jobs online, I noticed my BS degree fit the criteria to apply for a job in clinical research. I knew nothing about the field.”

“My friend recommended I look into jobs with a CRO because I wanted to transition out of a production laboratory.”

“I responded to an ad. I didn’t really know that research could be a profession though. I didn’t know anything about the field, principles, or daily activities.”

Some of the respondents reported moving into a permanent position after a role as an intern.

“My first clinical job came from an internship I did in my undergrad in basic sleep research. I thought I wanted to get into patient therapies, so I was able to transfer to addiction clinical trials from a basic science lab. And the clinical data management I did as an undergrad turned into a job after a few months.”

“I obtained a job directly from my graduate school practicum.”

“My research assistant internship [as an] undergrad provided some patient enrollment and consenting experience and led to a CRO position.”

Networking and referrals were other themes that respondents indicated had a direct impact on them finding initial employment in clinical research.

“I received a job opportunity (notice of an opening) through my e-mail from the graduate program.”

“I was a medical secretary for a physician who did research and he needed a full-time coordinator for a new study.”

“I was recommended by my manager at the time.”

“A friend had a similar position at the time. I was interested in learning more about the clinical research coordinator position.”

“What advice do you have for students and new graduates trying to enter their first role in clinical research?”

We found respondents (n=30) sorted into four distinct categories: 1) a general attitude/approach to job searching, 2) acquisition of knowledge/experience, 3) actions taken to get a position, and 4) personal attributes as a clinical research professional in their first job.

Respondents stressed the importance of flexibility and persistence (general attitude/approach) when seeking jobs. Moreover, 16 respondents stressed the importance of learning as much as they could about clinical research and gaining as much experience as they could in their jobs, encouraging them to ask a lot of questions. They also stressed a broader understanding of the clinical research enterprise, the impact that clinical research professional roles have on study participants and future patients, and the global nature of the enterprise.

“Apply for all research positions that sound interesting to you. Even if you don’t meet all the requirements, still apply.”

“Be persistent and flexible. Be willing to learn new skills and take on new responsibilities. This will help develop your own niche within a group/organization while creating opportunities for advancement.”

“Be flexible with salary requirements earlier in your career and push yourself to learn more [about the industry’s] standards [on] a global scale.”

“Be ever ready to adapt and change along with your projects, science, and policy. Never forget the journey the patients are on and that we are here to advance and support it.”

“Learning the big picture, how everything intertwines and works together, will really help you progress in the field.”

In addition to learning as much as one can about roles, skills, and the enterprise as a whole, advice was given to shadow or intern whenever possible—formally or through networking—and to be willing to start with a smaller company or with a lower position. The respondents stressed that novices entering the field will advance in their careers as they continue to gain knowledge and experience, and as they broaden their network of colleagues.

“Take the best opportunity available to you and work your way up, regardless [if it is] at clinical trial site or in industry.”

“Getting as much experience as possible is important; and learning about different career paths is important (i.e., not everyone wants or needs to be a coordinator, not everyone goes to graduate school to get a PhD, etc.).”

“(A graduate) program is beneficial as it provides an opportunity to learn the basics that would otherwise accompany a few years of entry-level work experience.”

“Never let an opportunity pass you up. Reach out directly to decision-makers via e-mail or telephone—don’t just rely on a job application website. Be willing to start at the bottom. Absolutely, and I cannot stress this enough, [you should] get experience at the site level, even if it’s just an internship or [as a] volunteer. I honestly feel that you need the site perspective to have success at the CRO or pharma level.”

Several personal behaviors were also stressed by respondents, such as knowing how to set boundaries, understanding how to demonstrate what they know, and ability to advocate for their progression. Themes such as doing a good job, communicating well, being a good team player, and sharing your passion also emerged.

“Be a team player, ask questions, and have a good attitude.”

“Be eager to share your passion and drive. Although you may lack clinical research experience, your knowledge and ambition can impress potential employers.”

“[A] HUGE thing is learning to sell yourself. Many people I work with at my current CRO have such excellent experience, and they are in low-level positions because they didn’t know how to negotiate/advocate for themselves as an employee.”

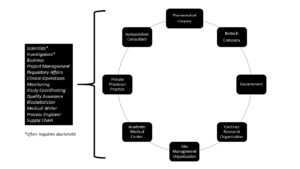

This mixed-methods study used purposeful sampling of students in an academic clinical research program to gain an understanding of how novices to the field find their initial jobs in the clinical research enterprise; how to transition to a clinical research career; and how to find opportunities for career advancement. There are multiple clinical research careers and employers (see Figure 2) available to individuals working in the clinical research enterprise.

Figure 2: Employers and Sample Careers

Despite the need for employees in the broad field of clinical research, finding a pathway to enter the field can be difficult for novices. The lack of knowledge about clinical research as a career option at the high school and college level points to an opportunity for broader inclusion of these careers in high school and undergraduate curricula, or as an option for guidance counselors to be aware of and share with students.

Because most clinical research jobs appear to require previous experience in order to gain entry, novices are often put into a “Catch-22” situation. However, once hired, upward mobility does exist, and was demonstrated in this survey. Mobility in clinical research careers (moving up and general turnover) may occur for a variety of reasons—usually to achieve a higher salary, to benefit from an improved work environment, or to thwart a perceived lack of progression opportunity.{9}

During COVID-19, there may be hiring freezes or furloughs of clinical research staff, but those personnel issues are predicted to be temporary. Burnout has also been reported as an issue among study coordinators, due to research study complexity and workload issues.{12} Moreover, the lack of individualized development planning revealed by our sample may indicate a unique workforce development need across roles of clinical research professionals.

This survey study is limited in that it is a small sample taken specifically from a narrow cohort of individuals who had obtained or were seeking a graduate degree in clinical research at a single institution. The study only surveyed those currently working in or who have a work history in clinical research. Moreover, the majority of respondents were employed at an academic medical center, which may not fully reflect the general population of clinical research professionals.

It was heartening to see the positive advancement in job titles for those individuals who had been employed in clinical research at program entry, compared to when they responded to the survey. However, the sample was too small to draw reliable correlations about job seeking or progression.

Although finding one’s first job in clinical research can be a lengthy and discouraging process, it is important to know that the opportunities are endless. Search in employment sites such as Indeed.com, but also search within job postings for targeted companies or research sites such as biopharmguy.com (see Table 1). Created a LinkedIn account and join groups and make connections. Participants in this study offered sound advice and tips for success in landing a job (see Figure 3).

Table 1: Sample Details from an Indeed.Com Job Search

| Clinical Research Patient Recruiter | PPD | Bachelor’s degree and related experience |

| Clinical Research Assistant | Duke University | Associate degree |

| Clinical Trials Assistant | Guardian Research Network | Bachelor’s degree and knowledge of clinical trials |

| Clinical Trials Coordinator | Advarra Health Analytics | Bachelor’s degree |

| Clinical Research Specialist | Castle Branch | Bachelor’s degree and six months in a similar role |

| Clinical Research Technician | Rose Research Center, LLC | Knowledge of Good Clinical Practice and experience working with patients |

| Clinical Research Lab Coordinator | Coastal Carolina Research Center | One year of phlebotomy experience |

| Project Specialist | WCG | Bachelor’s degree and six months of related experience |

| Data Coder | WCG | Bachelor’s degree or currently enrolled in an undergraduate program |

Note: WCG = WIRB Copernicus Group

Figure 3: Twelve Tips for Finding Your First Job

- Seek out internships and volunteer opportunities

- Network, network, network

- Be flexible and persistent

- Learn as much as possible about clinical research

- Consider a degree in clinical research

- Ask a lot of questions of professionals working in the field

- Apply for all research positions that interest you, even if you think you are not qualified

- Be willing to learn new skills and take on new responsibilities

- Take the best opportunity available to you and work your way up

- Learn to sell yourself

- Sharpen communication (written and oral) and other soft skills

- Create an ePortfolio or LinkedIn account

Being willing to start at the ground level and working upwards was described as a positive approach because moving up does happen, and sometimes quickly. Also, learning soft skills in communication and networking were other suggested strategies. Gaining education in clinical research is one way to begin to acquire knowledge and applied skills and opportunities to network with experienced classmates who are currently working in the field.

Most individuals entering an academic program have found success in obtaining an initial job in clinical research, often before graduation. In fact, the student initiating the survey found a position in a CRO before graduation.

- Sonstein S, Seltzer J, Li R, Jones C, Silva H, Daemen E. 2014. Moving from compliance to competency: a harmonized core competency framework for the clinical research professional. Clinical Researcher 28(3):17–23. doi:10.14524/CR-14-00002R1.1. https://acrpnet.org/crjune2014/

- Sonstein S, Brouwer RN, Gluck W, et al. 2018. Leveling the joint task force core competencies for clinical research professionals. Therap Innov Reg Sci .

- Jones CT, Benner J, Jelinek K, et al. 2016. Academic preparation in clinical research: experience from the field. Clinical Researcher 30(6):32–7. doi:10.14524/CR-16-0020. https://acrpnet.org/2016/12/01/academic-preparation-in-clinical-research-experience-from-the-field/

- Jones CT, Gladson B, Butler J. 2015. Academic programs that produce clinical research professionals. DIA Global Forum 7:16–9.

- Brouwer RN, Deeter C, Hannah D, et al. 2017. Using competencies to transform clinical research job classifications. J Res Admin 48:11–25.

- Stroo M, Ashfaw K, Deeter C, et al. 2020. Impact of implementing a competency-based job framework for clinical research professionals on employee turnover. J Clin Transl Sci.

- Calvin-Naylor N, Jones C, Wartak M, et al. 2017. Education and training of clinical and translational study investigators and research coordinators: a competency-based approach. J Clin Transl Sci 1:16–25. doi:10.1017/cts.2016.2

- Development, Implementation and Assessment of Novel Training in Domain-based Competencies (DIAMOND). Center for Leading Innovation and Collaboration (CLIC). 2019. https://clic-ctsa.org/diamond

- Clinical Trials Talent Survey Report. 2018. http://www.appliedclinicaltrialsonline.com/node/351341/done?sid=15167

- Causey M. 2020. CRO workforce turnover hits new high. ACRP Blog . https://acrpnet.org/2020/01/08/cro-workforce-turnover-hits-new-high/

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. 2009. Research electronic data capture (REDCap): a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 42:377–81.

- Gwede CK, Johnson DJ, Roberts C, Cantor AB. 2005. Burnout in clinical research coordinators in the United States. Oncol Nursing Forum 32:1123–30.

A portion of this work was supported by the OSU CCTS, CTSA Grant #UL01TT002733.

Bridget Kesling, MACPR, ( [email protected] ) is a Project Management Analyst with IQVIA in Durham, N.C.

Carolynn Jones, DNP, MSPH, RN, FAAN, ( [email protected] ) is an Associate Professor of Clinical Nursing at The Ohio State University College of Nursing, Co-Director of Workforce Development for the university’s Center for Clinical and Translational Science, and Director of the university’s Master of Clinical Research program.

Jessica Fritter, MACPR, ( [email protected] ) is a Clinical Research Administration Manager at Nationwide Children’s Hospital and an Instructor for the Master of Clinical Research program at The Ohio State University.

Marjorie V. Neidecker, PhD, MEng, RN, CCRP, ( [email protected] ) is an Assistant Professor of Clinical Nursing at The Ohio State University Colleges of Nursing and Pharmacy.

Sorry, we couldn't find any jobs that match your criteria.

Improving Cardiovascular Research for Transgender and Gender Diverse Populations

Disruptive Technologies Redefining the Path of Clinical Trials

How an Innovative Statistical Methodology Enables More Patient-Centric Design and Analysis of Clinical Trials

- New releases

- All articles

- Introduction

- Meet the team

- Take our survey

- Donate to 80,000 Hours

- Stay updated

- Acknowledgements

- Work with us

- Evaluations

- Our mistakes

- Research process and principles

- What others say about us

- Translations of our content

Research skills

By Benjamin Hilton · Last updated December 2023 · First published September 2023

- Like (opens in new window)

- Tweet (opens in new window)

- Share (opens in new window)

- Save to Pocket Pocket (opens in new window)

Research skills

On this page:.

- 1.1 Research seems to have been extremely high-impact historically

- 1.2 There are good theoretical reasons to think that research will be high-impact

- 1.3 Research skills seem extremely useful to the problems we think are most pressing

- 1.4 If you’re a good fit, you can have much more impact than the average

- 1.5 Depending on which subject you focus on, you may have good backup options

- 2.1 Academic research

- 2.2 Practical but big picture research

- 2.3 Applied research

- 2.4 Stages of progression through building and using research skills

- 3.1 How much do researchers differ in productivity?

- 3.2 What does this mean for building research skills?

- 4.1 How to predict your fit in advance

- 4.2 How to tell if you’re on track

- 5.1 Choosing a research field

- 6.1 Which research topics are the highest-impact?

- 6.2 Find jobs that use a research skills

- 7 Career paths we’ve reviewed that use these skills

- 8 Learn more about research

David Iliff , CC BY-SA 2.5 , via Wikimedia Commons

Norman Borlaug was an agricultural scientist. Through years of research, he developed new, high-yielding, disease-resistant varieties of wheat.

It might not sound like much, but as a result of Borlaug’s research, wheat production in India and Pakistan almost doubled between 1965 and 1970, and formerly famine-stricken countries across the world were suddenly able to produce enough food for their entire populations. These developments have been credited with saving up to a billion people from famine, 1 and in 1970, Borlaug was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.

Many of the highest-impact people in history , whether well-known or completely obscure, have been researchers.

Table of Contents

In a nutshell: Talented researchers are a key bottleneck facing many of the world’s most pressing problems . That doesn’t mean you need to become an academic. While that’s one option (and academia is often a good place to start), lots of the most valuable research happens elsewhere. It’s often cheap to try out developing research skills while at university, and if it’s a good fit for you, research could be your highest impact option.

Key facts on fit

Why are research skills valuable.

Not everyone can be a Norman Borlaug, and not every discovery gets adopted. Nevertheless, we think research can often be one of the most valuable skill sets to build — if you’re a good fit.

We’ll argue that:

Research seems to have been extremely high-impact historically

There are good theoretical reasons to think that research will be high-impact, research skills seem extremely useful to the problems we think are most pressing, if you’re a good fit, you can have much more impact than the average.

- And, depending on which subject you focus on, you may have good backup options .

Together, this suggests that research skills could be particularly useful for having an impact.

Later, we’ll look at:

- How to evaluate your fit for building research skills

How to get started building research skills

- How you can use these skills to have an impact once you’ve started

If we think about what has most improved the modern world, much can be traced back to research: advances in medicine such as the development of vaccines against infectious diseases, developments in physics and chemistry that led to steam power and the industrial revolution , and the invention of the modern computer, an idea which was first proposed by Alan Turing in his seminal 1936 paper On Computable Numbers . 2

Many of these ideas were discovered by a relatively small number of researchers — but they changed all of society. This suggests that these researchers may have had particularly large individual impacts.

That said, research today is probably lower-impact than in the past. Research is much less neglected than it used to be: there are nearly 25 times as many researchers today as there were in 1930. 3 It also turns out that more and more effort is required to discover new ideas, so each additional researcher probably has less impact than those that came before. 4

However, even today, a relatively small fraction of people are engaged in research. As an approximation, only 0.1% of the population are academics, 5 and only about 2.5% of GDP is spent on research and development . If a small number of people account for a large fraction of progress, then on average each person’s efforts are significant.

Moreover, we still think there’s a good case to be made for research being impactful on average today, which we cover in the next two sections.

There’s little commercial incentive to focus on the most socially valuable research. And most researchers don’t get rich, even if their discoveries are extremely valuable. Alan Turing made no money from the discovery of the computer, and today it’s a multibillion-dollar industry. This is because the benefits of research often come a long time in the future and can’t usually be protected by patents. This means if you care more about social impact than profit, then it’s a good opportunity to have an edge.

Research is also a route to leverage. When new ideas are discovered, they can be spread incredibly cheaply, so it’s a way that a single person can change a field. And innovations are cumulative — once an idea has been discovered, it’s added to our stock of knowledge and, in the ideal case, becomes available to everyone. Even ideas that become outdated often speed up the important future discoveries that supersede it.

When you look at our list of the world’s most pressing problems — like preventing future pandemics or reducing risks from AI systems — expert researchers seem like a key bottleneck.

For example, to reduce the risk posed by engineered pandemics , we need people who are talented at research to identify the biggest biosecurity risks and to develop better vaccines and treatments.

To ensure that developments in AI are implemented safely and for the benefit of humanity, we need technical experts thinking hard about how to design machine learning systems safely and policy researchers to think about how governments and other institutions should respond. (See this list of relevant research questions .)

And to decide which global priorities we should spend our limited resources on, we need economists, mathematicians, and philosophers to do global priorities research . For example, see the research agenda of the Global Priorities Institute at Oxford .

We’re not sure why so many of the most promising ways to make progress on the problems we think are most pressing involve research, but it may well be due to the reasons in the section above — research offers huge opportunities for leverage, so if you take a hits-based approach to finding the best solutions to social problems, it’ll often be most attractive.

In addition, our focus on neglected problems often means we focus on smaller and less developed areas, and it’s often unclear what the best solutions are in these areas. This means that research is required to figure this out.

For more examples, and to get a sense of what you might be able to work on in different fields, see this list of potentially high-impact research questions, organised by discipline .

The sections above give reasons why research can be expected to be impactful in general . But as we’ll show below , the productivity of individual researchers probably varies a great deal (and more than in most other careers). This means that if you have reason to think your degree of fit is better than average, your expected impact could be much higher than the average.

Depending on which subject you focus on, you may have good backup options

Pursuing research helps you develop deep expertise on a topic, problem-solving, and writing skills. These can be useful in many other career paths. For example:

- Many research areas can lead to opportunities in policymaking , since relevant technical expertise is valued in some of these positions. You might also have opportunities to advise policymakers and the public as an expert.

- The expertise and credibility you can develop by focusing on research (especially in academia) can put you in a good position to switch your focus to communicating important ideas , especially those related to your speciality, either to the general public, policymakers, or your students.

- If you specialise in an applied quantitative subject, it can open up certain high-paying jobs, such as quantitative trading or data science , which offer good opportunities for earning to give .

Some research areas will have much better backup options than others — lots of jobs value applied quantitative skills, so if your research is quantitative you may be able to transition into work in effective nonprofits or government. A history academic, by contrast, has many fewer clear backup options outside of academia.

What does building research skills typically involve?

By ‘research skills’ we broadly mean the ability to make progress solving difficult intellectual problems.

We find it especially useful to roughly divide research skills into three forms:

- Academic research

Building academic research skills is the most predefined route. The focus is on answering relatively fundamental questions which are considered valuable by a specific academic discipline. This can be impactful either through generally advancing a field of research that’s valuable to society or finding opportunities to work on socially important questions within that field.

Turing was an academic. He didn’t just invent the computer — during World War II he developed code-breaking machines that allowed the Allies to be far more effective against Nazi U-boats. Some historians estimate this enabled D-Day to happen a year earlier than it would have otherwise. 6 Since World War II resulted in 10 million deaths per year, Turing may have saved about 10 million lives.

We’re particularly excited about academic research in subfields of machine learning relevant to reducing risks from AI , subfields of biology relevant to preventing catastrophic pandemics , and economics — we discuss which fields you should enter below .

Academic careers are also excellent for developing credibility, leading to many of the backup options we looked at above, especially options in communicating important ideas or policymaking .

Academia is relatively unique in how flexibly you can use your time. This can be a big advantage — you really get time to think deeply and carefully about things — but can be a hindrance, depending on your work style.

See more about what academia involves in our career review on academia .

Practical but big picture research

Academia rewards a focus on questions that can be decisively answered with the methods of the field. However, the most important questions can rarely be answered rigorously — the best we can do is look at many weak forms of evidence and come to a reasonable overall judgement. which means while some of this research happens in academia, it can be hard to do that.

Instead, this kind of research is often done in nonprofit research institutes, e.g. the Centre for the Governance of AI or Our World in Data , or independently.

Your focus should be on answering the questions that seem most important (given your view of which global problems most matter) through whatever means are most effective.

Some examples of questions in this category that we’re especially interested in include:

- How likely is a pandemic worse than COVID-19 in the next 10 years?

- How difficult is the AI alignment problem going to be to solve?

- Which global problems are most pressing?

- Is the world getting better or worse over time?

- What can we learn from the history of philanthropy about which forms of philanthropy might be most effective?

You can see a longer list of ideas in this article .

Someone we know who’s had a big impact with research skills is Ajeya Cotra. Ajeya initially studied electrical engineering and computer science at UC Berkeley. In 2016, she joined Open Philanthropy as a grantmaker. 7 Since then she’s worked on a framework for estimating when transformative AI might be developed , how worldview diversification could be applied to allocating philanthropic budgets, and how we might accidentally teach AI models to deceive us .

Applied research

Then there’s applied research. This is often done within companies or nonprofits, like think tanks (although again, there’s also plenty of applied research happening in academia). Here the focus is on solving a more immediate practical problem (and if pursued by a company, where it might be possible to make profit from the solution) — and there’s lots of overlap with engineering skills . For example:

- Developing new vaccines

- Creating new types of solar cells or nuclear reactors

- Developing meat substitutes

Neel was doing an undergraduate degree in maths when he decided that he wanted to work in AI safety . Our team was able to introduce Neel to researchers in the field and helped him secure internships in academic and industry research groups. Neel didn’t feel like he was a great fit for academia — he hates writing papers — so he applied to roles in commercial AI research labs. He’s now a research engineer at DeepMind. He works on mechanistic interpretability research which he thinks could be used in the future to help identify potentially dangerous AI systems before they can cause harm.

We also see “policy research” — which aims to develop better ideas for public policy — as a form of applied research.

Stages of progression through building and using research skills

These different forms of research blur into each other, and it’s often possible to switch between them during a career. In particular, it’s common to begin in academic research and then switch to more applied research later.

However, while the skill sets contain a common core, someone who can excel in intellectual academic research might not be well-suited to big picture practical or applied research.

The typical stages in an academic career involve the following steps:

- Pick a field. This should be heavily based on personal fit (where you expect to be most successful and enjoy your work the most), though it’s also useful to think about which fields offer the best opportunities to help tackle the problems you think are most pressing, give you expertise that’s especially useful given these problems, and use that at least as a tie-breaker. (Read more about choosing a field .)

- Earn a PhD.

- Learn your craft and establish your career — find somewhere you can get great mentorship and publish a lot of impressive papers. This usually means finding a postdoc with a good group and then temporary academic positions.

- Secure tenure.

- Focus on the research you think is most socially valuable (or otherwise move your focus towards communicating ideas or policy).

Academia is usually seen as the most prestigious path…within academia. But non-academic positions can be just as impactful — and often more so since you can avoid some of the dysfunctions and distractions of academia, such as racing to get publications.

At any point after your PhD (and sometimes with only a master’s), it’s usually possible to switch to applied research in industry, policy, nonprofits, and so on, though typically you’ll still focus on getting mentorship and learning for at least a couple of years. And you may also need to take some steps to establish your career enough to turn your attention to topics that seem more impactful.

Note that from within academia, the incentives to continue with academia are strong, so people often continue longer than they should!

If you’re focused on practical big picture research, then there’s less of an established pathway, and a PhD isn’t required.

Besides academia, you could attempt to build these skills in any job that involves making difficult, messy intellectual judgement calls, such as investigative journalism, certain forms of consulting, buy-side research in finance, think tanks, or any form of forecasting.

Personal fit is perhaps more important for research than other skills

The most talented researchers seem to differ hugely in their impact compared to typical researchers across a wide variety of metrics and according to the opinions of other researchers.

For instance, when we surveyed biomedical researchers, they said that very good researchers were rare, and they’d be willing to turn down large amounts of money if they could get a good researcher for their lab. 8 Professor John Todd, who works on medical genetics at Cambridge, told us :

The best people are the biggest struggle. The funding isn’t a problem. It’s getting really special people[…] One good person can cover the ground of five, and I’m not exaggerating.

This makes sense if you think the distribution of research output is very wide — that the very best researchers have a much greater output than the average researcher.

How much do researchers differ in productivity?

It’s hard to know exactly how spread out the distribution is, but there are several strands of evidence that suggest the variability is very high.

Firstly, most academic papers get very few citations, while a few get hundreds or even thousands. An analysis of citation counts in science journals found that ~47% of papers had never been cited, more than 80% had been cited 10 times or less, but the top 0.1% had been cited more than 1,000 times. A similar pattern seems to hold across individual researchers , meaning that only a few dominate — at least in terms of the recognition their papers receive.

Citation count is a highly imperfect measure of research quality, so these figures shouldn’t be taken at face-value. For instance, which papers get cited the most may depend at least partly on random factors, academic fashions, and “winner takes all” effects — papers that get noticed early end up being cited by everyone to back up a certain claim, even if they don’t actually represent the research that most advanced the field.

However, there are other reasons to think the distribution of output is highly skewed.

William Shockley, who won the Nobel Prize for the invention of the transistor, gathered statistics on all the research employees in national labs, university departments, and other research units, and found that productivity (as measured by total number of publications, rate of publication, and number of patents) was highly skewed , following a log-normal distribution.

Shockley suggests that researcher output is the product of several (normally distributed) random variables — such as the ability to think of a good question to ask, figure out how to tackle the question, recognize when a worthwhile result has been found, write adequately, respond well to feedback, and so on. This would explain the skewed distribution: if research output depends on eight different factors and their contribution is multiplicative, then a person who is 50% above average in each of the eight areas will in expectation be 26 times more productive than average. 9

When we looked at up-to-date data on how productivity differs across many different areas , we found very similar results. The bottom line is that research seems to perhaps be the area where we have the best evidence for output being heavy-tailed.

Interestingly, while there’s a huge spread in productivity, the most productive academic researchers are rarely paid 10 times more than the median, since they’re on fixed university pay-scales. This means that the most productive researchers yield a large “excess” value to their field. For instance, if a productive researcher adds 10 times more value to the field than average, but is paid the same as average, they will be producing at least nine times as much net benefit to society. This suggests that top researchers are underpaid relative to their contribution, discouraging them from pursuing research and making research skills undersupplied compared to what would be ideal.

Can you predict these differences in advance?

Practically, the important question isn’t how big the spread is, but whether you could — early on in your career — identify whether or not you’ll be among the very best researchers.

There’s good news here! At least in scientific research, these differences also seem to be at least somewhat predictable ahead of time, which means the people entering research with the best fit could have many times more expected impact.

In a study , two IMF economists looked at maths professors’ scores in the International Mathematical Olympiad — a prestigious maths competition for high school students. They concluded that each additional point scored on the International Mathematics Olympiad “is associated with a 2.6 percent increase in mathematics publications and a 4.5 percent increase in mathematics citations.”

We looked at a range of data on how predictable productivity differences are in various areas and found that they’re much more predictable in research.

What does this mean for building research skills?

The large spread in productivity makes building strong research skills a lot more promising if you’re a better fit than average. And if you’re a great fit, research can easily become your best option.

And while these differences in output are not fully predictable at the start of a career, the spread is so large that it’s likely still possible to predict differences in productivity with some reliability.

This also means you should mainly be evaluating your long-term expected impact in terms of your chances of having a really big success.

That said, don’t rule yourself out too early. Firstly, many people systematically underestimate their skills . (Though others overestimate them!) Also, the impact of research can be so large that it’s often worth trying it out, even if you don’t expect you’ll succeed . This is especially true because the early steps of a research career often give you good career capital for many other paths.

How to evaluate your fit

How to predict your fit in advance.

It’s hard to predict success in advance, so we encourage an empirical approach: see if you can try it out and look at your track record.

You probably have some track record in research: many of our readers have some experience in academia from doing a degree, whether or not they intended to go into academic research. Standard academic success can also point towards being a good fit (though is nowhere near sufficient!):

- Did you get top grades at undergraduate level (a 1st in the UK or a GPA over 3.5 in the US)?

- If you do a graduate degree, what’s your class rank (if you can find that out)? If you do a PhD, did you manage to author an article in a top journal (although note that this is easier in some disciplines than others)?

Ultimately, though, your academic track record isn’t going to tell you anywhere near as much as actually trying out research. So it’s worth looking for ways to cheaply try out research (which can be easy if you’re at college). For example, try doing a summer research project and see how it goes.

Some of the key traits that suggest you might be a good fit for a research skills seem to be:

- Intelligence (Read more about whether intelligence is important for research .)

- The potential to become obsessed with a topic ( Becoming an expert in anything can take decades of focused practice , so you need to be able to stick with it.)

- Relatedly, high levels of grit, self-motivation, and — especially for independent big picture research, but also for research in academia — the ability to learn and work productively without a traditional manager or many externally imposed deadlines

- Openness to new ideas and intellectual curiosity

- Good research taste, i.e. noticing when a research question matters a lot for solving a pressing problem

There are a number of other cheap ways you might try to test your fit.

Something you can do at any stage is practice research and research-based writing. One way to get started is to try learning by writing .

You could also try:

- Finding out what the prerequisites/normal backgrounds of people who go into a research area are to compare your skills and experience to them

- Reading key research in your area, trying to contribute to discussions with other researchers (e.g. via a blog or twitter), and getting feedback on your ideas

- Talking to successful researchers in a field and asking what they look for in new researchers

How to tell if you’re on track

Here are some broad milestones you could aim for while becoming a researcher:

- You’re successfully devoting time to building your research skills and communicating your findings to others. (This can often be the hardest milestone to hit for many — it can be hard to simply sustain motivation and productivity given how self-directed research often needs to be.)

- In your own judgement, you feel you have made and explained multiple novel, valid, nontrivially important (though not necessarily earth-shattering) points about important topics in your area.

- You’ve had enough feedback (comments, formal reviews, personal communication) to feel that at least several other people (whose judgement you respect and who have put serious time into thinking about your area) agree, and (as a result) feel they’ve learned something from your work. For example, lots of this feedback could come from an academic supervisor. Make sure you’re asking people in a way that gives them affordance to say you’re not doing well.

- You’re making meaningful connections with others interested in your area — connections that seem likely to lead to further funding and/or job opportunities. This could be from the organisations most devoted to your topics of interest; but, there could also be a “dissident” dynamic in which these organisations seem uninterested and/or defensive, but others are noticing this and offering help.

If you’re finding it hard to make progress in a research environment, it’s very possible that this is the result of that particular environment, rather than the research itself. So it can be worth testing out multiple different research jobs before deciding this skill set isn’t for you.

Within academic research

Academia has clearly defined stages, so you can see how you’re performing at each of these.

Very roughly, you can try asking “How quickly and impressively is my career advancing, by the standards of my institution and field?” (Be careful to consider the field as a whole, rather than just your immediate peers, who might be very different from average.) Academics with more experience than you may be able to help give you a clear idea of how things are going.

We go through this in detail in our review of academic research careers .

Within independent research

As a very rough guideline, people who are an excellent fit for independent research can often reach the broad milestones above with a year of full-time effort purely focusing on building a research skill set, or 2–3 years of 20%-time independent effort (i.e. one day per week).

Within research in industry or policy

The stages here can look more like an organisation-building career , and you can also assess your fit by looking at your rate of progression through the organisation.

As we mentioned above , if you’ve done an undergraduate degree, one obvious pathway into research is to go to graduate school ( read our advice on choosing a graduate programme ) and then attempt to enter academia before deciding whether to continue or pursue positions outside of academia later in your career.

If you take the academic path, then the next steps are relatively clear. You’ll want to try to get excellent grades in undergraduate and in your master’s, ideally gain some kind of research experience in your summers, and then enter the best PhD programme you can. From there, focus on learning your craft by working under the best researcher you can find as a mentor and working in a top hub for your field. Try to publish as many papers as possible since that’s required to land an academic position.

It’s also not necessary to go to graduate school to become a great researcher (though this depends a lot on the field), especially if you’re very talented. For instance, we interviewed Chris Olah , who is working on AI research without even an undergraduate degree.

You can enter many non-academic research jobs without a background in academia. So one starting point for building up research skills would be getting a job at an organisation specifically focused on the type of question you’re interested in. For examples, take a look at our list of recommended organisations , many of which conduct non-academic research in areas relevant to pressing problems .

More generally, you can learn research skills in any job that heavily features making difficult intellectual judgement calls and bets, preferably on topics that are related to the questions you’re interested in researching. These might include jobs in finance, political analysis, or even nonprofits.

Another common route — depending on your field — is to develop software and tech skills and then apply them at research organisations. For instance, here’s a guide to how to transition from software engineering into AI safety research .

If you’re interested in doing practical big-picture research (especially outside academia), it’s also possible to establish your career through self-study and independent work — during your free time or on scholarships designed for this (such as EA Long-Term Future Fund grants and Open Philanthropy support for individuals working on relevant topics ).

Some example approaches you might take to self-study:

- Closely and critically review some pieces of writing and argumentation on relevant topics. Explain the parts you agree with as clearly as you can and/or explain one or more of your key disagreements.

- Pick a relevant question and write up your current view and reasoning on it. Alternatively, write up your current view and reasoning on some sub-question that comes up as you’re thinking about it.

- Then get feedback, ideally from professional researchers or those who use similar kinds of research in their jobs.

It could also be beneficial to start with some easier versions of this sort of exercise, such as:

- Explaining or critiquing interesting arguments made on any topic you find motivating to write about