Center for Teaching Innovation

Resource library.

- Exam Wrapper Examples

Self-Assessment

Self-assessment activities help students to be a realistic judge of their own performance and to improve their work.

Why Use Self-Assessment?

- Promotes the skills of reflective practice and self-monitoring.

- Promotes academic integrity through student self-reporting of learning progress.

- Develops self-directed learning.

- Increases student motivation.

- Helps students develop a range of personal, transferrable skills.

Considerations for Using Self-Assessment

- The difference between self-assessment and self-grading will need clarification.

- The process of effective self-assessment will require instruction and sufficient time for students to learn.

- Students are used to a system where they have little or no input in how they are assessed and are often unaware of assessment criteria.

- Students will want to know how much self-assessed assignments will count toward their final grade in the course.

- Incorporating self-assessment can motivate students to engage with the material more deeply.

- Self-assessment assignments can take more time.

- Research shows that students can be more stringent in their self-assessment than the instructor.

Getting Started with Self-Assessment

- Identify which assignments and criteria are to be assessed.

- Articulate expectations and clear criteria for the task. This can be accomplished with a rubric . You may also ask students to complete a checklist before turning in an assignment.

- Motivate students by framing the assignment as an opportunity to reflect objectively on their work, determine how this work aligns with the assignment criteria, and determine ways for improvement.

- Provide an opportunity for students to agree upon and take ownership of the assessment criteria.

- Draw attention to the inner dialogue that people engage in as they produce a piece of work. You can model this by talking out loud as you solve a problem, or by explaining the types of decisions you had to think about and make as you moved along through a project.

- Consider using an “exam wrapper” or “assignment wrapper.” These short worksheets ask students to reflect on their performance on the exam or assignment, how they studied or prepared, and what they might do differently in the future. Examples of exam and homework wrappers can be found through Carnegie Mellon University’s Eberly Center.

Helping Students Thrive by Using Self-Assessment

As a teacher, when you design a lesson or unit, you design it with the hope that everything will go according to plan, your students will learn the content, and they’ll be ready to move on to the next concept. If you’ve been a teacher for more than a day or two, however, you know that this often isn’t the case.

Some students will pick up the information and quickly get bored while others will be lost and quickly fall behind. And sometimes, the lesson will fall flat and none of your students will understand much of anything.

Other times, a lesson will work really well with one group of students, but it will flop with another. This is all just par for the course with teaching, and you never know what you’re going to get on any given day.

Thankfully, there is a way you can make your lessons better, more achievable, and more appropriate for all students. The solution is to teach them how to use self-assessment.

Self-assessment is one of those “teach a man to fish” concepts–once students understand how to self-assess, they’ll be more equipped to learn in all aspects of their life. At the very basic level, self assessment is simple: students need to think:

- What was I supposed to learn?

- Did I learn it?

- What questions do I still have?

This formative assessment helps students and teachers understand where they’re at in their learning. The more students learn to do this at your direction and the more techniques they have to self-assess, the more likely they are to inherently do it on their own.

What does self-assessment look like?

Self-assessment can take many forms, and it can be very quick and informal, or it might be more structured and important. In essence though, self assessment looks like students pausing to examine what they do and don’t know. However, if you simply say, “OK, class, time to self-assess,” you’ll likely be met with blank stares.

The more you’re able to walk students through strategies for self-assessment, the more they’ll understand the purpose, process, and value of thinking about their learning. For the best results to reach the most students, aim to incorporate different types of self-assessment, just as you aim to incorporate different ways of teaching into your lessons.

Why self-assessment works

One of the reasons self-assessment is so effective is because it helps students stay within their zone of proximal development when they’re learning. In this zone, students are being challenged, which means they’re learning, but they’re not being pushed too hard into frustration.

The reason this is so helpful is because teachers can see anywhere from 15-150+ students every day, so it’s hard for a teacher to know where every single student is at in his or her learning. Without stopping for self-assessment, it’s easy for a teacher to move on before students are ready or to belabor a concept students mastered days ago.

When students are able to self-assess, they take control of their learning and realize when they need to ask more questions or spend more time working on a concept. Self-assessment that is relayed back to the teacher, either formally or informally, helps the teacher get a better idea of where students are at with their learning.

Another benefit of self-assessment is that students tend to take more ownership and find more value in their learning, according to a study out of Duquesne University. According to the study, formative assessments like self-assessment “give students the means, motive, and opportunity to take control of their own learning.” When teachers give students those opportunities, they empower their students and help turn them into active, rather than passive learners.

Self-assessment also helps students practice learning independently, which is a key skill for life, and especially for students who are pursuing higher education.

How to execute self assessment

To truly make this part of your classroom, you’ll need to explain to students what you’re doing, why you’re doing it, and you’ll need to hold them accountable for their self assessment. The following steps can help you successfully set up self-assessment in your classroom.

Step 1: Explain what self-assessment is and why it’s important

Sometimes teachers have a tendency to surprise students with what’s coming next or to not explain the reasoning behind a teaching strategy or decision. While this is often done out of a desire for control and power as the leader of the classroom, it doesn’t do much to help students and their learning.

If students don’t understand why they’re doing what they’re doing, they usually won’t do it at all, or will just to the bare minimum to go through the motions and get the grade. If students don’t understand the purpose of a learning strategy, they often see it as busy work. Most students are very used to being assessed only by their teachers, so they may not understand why they’re suddenly being asked to take stock of their own learning.

Make sure you take the time to explain why you’re implementing this new learning strategy and how it is going to directly benefit them. That explanation is going to vary based on the age of your students and other factors, but you can give students some variation of the explanation of why self-assessment works above.

Step 2: Always show a model

As you scroll down, you’ll see that we give you some examples of ways to use self assessment; each time you try one of these new techniques, be sure to create an exemplar model for your students. If you want this to work, students need to know what the goal that they’re working toward looks like.

Depending on the type of self-assessment you’re working with, a simple model might be enough, or students might need to practice with the work of others. A low stakes way to start this out is with examples from past students. Pull out an old project from years past and have students assess the project as if it were their own.

Once students learn how to be respectful and constructive with this peer assessment, they can practice with the peers in their class. Including this step often makes it easier for students to assess their own work. It can be hard to look back at your own work or thought process, especially if not much time has passed since you did the work.

Step 3: Teach students different strategies of self-assessment

We all learn best by doing, so rather than just giving students a list of self-assessment strategies, take your time walking through different strategies together. Also remember that the strategy that works best for Jimmy might not work well for Susan, so the more you can diversify self-assessment for your students, the more students you’re going to be able to reach.

Try starting with just one type of self assessment, give students time to master that type, then add another type. As time goes on, you can offer students choice in the type of self-assessment they want to use.

Step 4: Practice

Before you ask students to actively assess their own work, let them practice with some low stakes examples. It’s hard for many people to critique themselves and to recognize they have room for improvement, yet it’s essential.

Give students some examples of work from past students (names always removed) and walk through “self” assessment with those examples together as a class.

Step 5: Create a way to hold students accountable

Self-assessment shouldn’t always be tied to a grade, but students will catch on quickly if you’re not somehow holding them accountable. There are many ways to do this, for example:

- Conference with each student throughout the process

- Make self-assessment part of the final grade for a project or unit

- Create a self-assessment reward chart

The important thing to remember with holding students accountable for their self-assessment is that you should be holding them accountable for doing the self-assessment, but not for what they do or don’t know, nor for the changes they make based on their self-assessment.

Step 6: Don’t stop

Sometimes we have a tendency to try a strategy once or twice and then let it slide as the school year goes on, but as students learn that they’re no longer being held accountable, they will stop. You can’t ever assume a student will keep using a strategy unless you give them explicit instructions and hold them accountable.

Remember that as with anything, students will get better at self-assessment the more they practice it. The more you explicitly assign self-assessment, the more it will become a normal part of the learning process.

Examples of self assessment

Remember that it’s good to use a variety of self-assessment strategies so all students have a chance to find a style that works best for them. Any time you introduce a new strategy or assign self-assessment, be very clear about what students should do and how they should do it.

The strategies we suggest are broken down by age, but always use your best judgment regarding which strategies will be best for your students.

KWL chart: Before starting a lesson or unit, have students write or say what they already know (K) and what they want to know (W) about the topic. After the lesson or unit, they write or say what they learned (L). This can easily evolve into larger discussions and assignments.

Goals: At the end of each lesson, day, week, etc. students write one learning goal they would like to achieve. This can be very open-ended, or it could be very focused, asking students to reflect on one specific subject or topic. You can expand on this by having students return to their goal to see if they met it, encouraging them to ask for help if they haven’t met their goal.

Red, yellow, green: Give each student three circles: one red, one yellow, and one green. Throughout the school day, students place their red circle on their desk if they’re lost or confused, yellow if they’re struggling a little bit, and green if they understand, and they’re good to go. You can also stop to have students check their understanding by asking them to hold up a color. Some students feel shy about admitting they’re confused, so this strategy can also work really well if you have students place their heads down before holding up their circle.

Objective check: In the morning, give students a list of objectives you will cover in school today. Have each student write down an objective they would really like to learn today. At the end of the day, students return to the objective and determine whether they learned it or not.

Tricky spots: Work with students to identify where they struggle (for example, “I have trouble with word problems in math,” or “I have trouble spelling new words”). When starting a new lesson or unit, have each student identify one tricky spot they want to focus on. Be sure to check in with students often on their tricky spot to make sure they are making progress and not getting frustrated.

Highlighting: Have students go back to a writing assignment, worksheet, or project and highlight the section that they think was their best work. As an extension, have them explain why this was their best work. This is an excellent strategy to use with students who struggle or lack confidence in their work.

Self reflection: After a speech or presentation, have students write down three things they did well and one thing they can improve on. Extend this by returning to these during the next speech or presentation; you could even make them part of the rubric for the next assignment.

Exit tickets: Before students can leave the room, they must fill out an exit ticket and hand it to the teacher. You might ask them to write one thing they learned today and one thing they want to learn tomorrow, for example.

Think, pair, share: Pose a reflective question or prompt to students, for example you might tell them to think about or even write down the most important thing they learned in class today. Next, have them pair with a partner or small group to discuss their answer to the question or prompt, and finally, have students report back to the whole class.

Grades 9-12

Rubrics: Before completing a project, give students the rubric you will use to grade their effort. Have students complete a draft of the project and assess themselves using the rubric. After they do this, you might conference with them, give them feedback, or have them complete a reflective assignment. Then, have students complete a second draft that they will turn in for their grade (or to continue to work and improve upon).

Writing conferences: After students write an outline or first draft of an essay, hold an individual conference with each student. Before you provide your input, have students identify the strengths and weaknesses of their work. Use their self assessment as the guide of what you discuss during the conference. You might even find that students are more critical of themselves than you would have been.

Empty rubrics: At the beginning of a project, leave a space on the rubric empty. Help each student fill in the empty spot with something they need to work on, whether it’s something that they’re already good at and want to get even better or it’s something they struggle with and want to get better at.

Similar Posts:

- Discover Your Learning Style – Comprehensive Guide on Different Learning Styles

- 15 Learning Theories in Education (A Complete Summary)

- 35 of the BEST Educational Apps for Teachers (Updated 2024)

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name and email in this browser for the next time I comment.

Skip to Content

Other ways to search:

- Events Calendar

- Student Self-assessment

Self-assessments encourage students to reflect on their growing skills and knowledge, learning goals and processes, products of their learning, and progress in the course. Student self-assessment can take many forms, from low-stakes check-ins on their understanding of the day’s lecture content to self-assessment and self-evaluation of their performance on major projects. Student self-assessment is also an important practice in courses that use alternative grading approaches . While the foci and mechanisms of self-assessment vary widely, at their core the purpose of all self-assessment is to “generate feedback that promotes learning and improvements in performance” (Andrade, 2019). Fostering students’ self-assessment skills can also help them develop an array of transferable lifelong learning skills, including:

- Metacognition: Thinking about one’s own thinking. Metacognitive skills allow learners to “monitor, plan, and control their mental processing and accurately judge how well they’ve learned something” (McGuire & McGuire 2015).

- Critical thinking: Carefully reasoning about the evidence and strength of evidence presented in support of a claim or argument.

- Reflective thinking: Examining or questioning one’s own assumptions, positionality, basis of your beliefs, growth, etc.

- Self-regulated learning: Setting goals, checking in on one’s own progress, reflecting on what learning or study strategies are working well or not so well, being intentional about where/when/how one studies, etc.

Students' skills to self-assess can vary, especially if they have not encountered many opportunities for structured self-assessment. Therefore, it is important to provide structure, guidance, and support to help them develop these skills over time.

- Create a supportive learning environment so that students feel comfortable sharing their self-assessment experiences ( Create a Supportive Course Climate ).

- Foster a growth-mindset in students by using strategies that show students that abilities can be grown through hard work, effective strategies, and help from others when needed ( Fostering Growth Mindset ; Identifying teaching behaviors that foster growth mindset classroom cultures ).

- Set clear, specific, measurable, and achievable learning outcomes so that students know what is expected of them and can better assess their progress ( Creating and Using Learning Outcomes ).

- Explain the concept of self-assessment and some of the benefits (above).

- Provide students with specific prompts and/or rubrics to guide self-assessment ( assessing student learning with Rubrics ).

- Provide clear instructions (see an example under Rubrics below).

- Encourage students to make adjustments to their learning strategies (e.g., retrieval, spacing, interleaving, elaboration, generation, reflection, calibration; Make It Stick , pp. 200-225) and/or set new goals based on their identified areas for improvement.

Self-Assessment Techniques

Expand the boxes below to learn more about techniques you can use to engage students in self-assessment and decide which would work best for your context.

To foster self-assessment as part of students’ regular learning practice you can embed prompts directly into your formative and summative assignments and assessments.

- What do you think is a fair grade for the work you have handed in, and why do you think so?

- What did you do best in this task?

- What did you do least well in this task?

- What did you find was the hardest part of completing this task?

- What was the most important thing you learned in doing this task?

- If you had more time to complete the task, what (if anything) would you change, and why?

Providing students the opportunity to regularly engage in writing that allows them to reflect on their learning experiences, habits, and practices can help students retain learning, identify challenges, and strengthen their metacognitive skills. Reflective writing may take the form of short writing prompts related to assignments (see Embedded self-assessment prompts above and Classroom Assessment Techniques ) or writing more broadly about recent learning experiences (e.g., What? So What? Now What? Journals ). Reflective writing is a skill that takes practice and is most effective when done regularly throughout the course ( Using Reflective Writing to Deepen Student Learning ).

Rubrics are an important tool to help students self-assess their work, especially for self-assessment that includes multiple prompts about the same piece of work. If you’re providing a rubric to guide self-assessment, it is important to also provide instructions on how to use the rubric.

Students are using a rubric (e.g., grading rubric for written assignments (docx) ) to self-assess a draft essay before turning it in or making revisions. As part of that process, you want them to assess their use of textual evidence to support their claim. Here are example instructions you could provide (adapted from Beard, 2021):

To self-assess your use of textual evidence to support your claim, please follow these steps:

- In your draft, highlight your claim sentence and where you used textual evidence to support your claim

- Based on the textual evidence you used, circle your current level of skill on the provided rubric

- Use the information on the provided rubric to list one action you can take to make your textual evidence stronger

Self-assessment surveys can be helpful if you are asking students to self-assess their skills, knowledge, attitudes, and/or effectiveness of study methods they used. These may take the form of 2-3 free-response questions or a questionnaire where students rate their agreement with a series of statements (e.g., I am skilled at creating formulas in Excel”, “I can define ‘promissory coup’”, “I feel confident in my study skills”). A Background Knowledge Probe administered at the very beginning of the course (or when starting a new unit) can help you better understand what students already know (or don’t know) about the class subject. Self-assessment surveys administered over time can help you and students assess their progress toward meeting defined learning outcomes (and provide you with feedback on the effectiveness of your teaching methods). Student Assessment of their Learning Gains is a free tool that you can use to create and administer self-assessment surveys for your course.

Wrappers are tools that learners use after completing and receiving feedback on an exam or assignment ( exam and assignment wrappers , post-test analysis ) or even after listening to a lecture ( lecture wrappers ). Instead of focusing on content, wrappers focus on the process of learning and are designed to provide students with a chance to reflect on their learning strategies and plan new strategies before the next assignment or assessment. The Eberly Center at Carnegie Mellon includes multiple examples of exam, homework, and paper wrappers for several disciplines.

References:

Andrade, H. L. (2019). A critical review of research on student self-assessment . Frontiers in Education , 4, Article 87.

Beard, E. (2021, April 27). The importance of student self-assessment . Northwest Evaluation Association (NWEA).

Brown, P. C., Roediger III, H. L., & McDaniel, M. A. (2014). Make it stick: The science of successful learning . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press

McGuire, S. Y., & McGuire, S. (2015). Teach students how to learn: Strategies you can incorporate into any course to improve student metacognition, study skills, and motivation . New York, NY: Routledge.

McMillan, J. H., & Hearn, J. (2008). Student Self-Assessment: The Key to Stronger Student Motivation and Higher Achievement . Educational Horizons , 87 (1), 40–49.

Race, P. (2001). A briefing on self, peer and group assessment (pdf) . LTSN Generic Centre, Assessment Series No. 9.

RCampus. (2023, June 7). Student self-assessments: Importance, benefits, and implementation .

Teaching (n.d.). Student Self-Assessment . University of New South Wales Sydney.

Further Reading & Resources:

Bjork, R. (n.d.). Applying cognitive psychology to enhance educational practice . UCLA Bjork Learning and Forgetting Lab.

Center for Teaching and Learning (n.d.). Classroom Assessment Techniques . University of Colorado Boulder.

Center for Teaching and Learning (n.d.). Formative Assessments . University of Colorado Boulder.

Center for Teaching and Learning (n.d.). Student Peer Assessment . University of Colorado Boulder.

Center for Teaching and Learning (n.d.). Summative Assessments . University of Colorado Boulder

Center for Teaching and Learning (n.d.). Summative Assessments: Types . University of Colorado Boulder

- Assessment in Large Enrollment Classes

- Classroom Assessment Techniques

- Creating and Using Learning Outcomes

- Early Feedback

- Five Misconceptions on Writing Feedback

- Formative Assessments

- Frequent Feedback

- Online and Remote Exams

- Student Learning Outcomes Assessment

- Student Peer Assessment

- Summative Assessments: Best Practices

- Summative Assessments: Types

- Assessing & Reflecting on Teaching

- Departmental Teaching Evaluation

- Equity in Assessment

- Glossary of Terms

- Attendance Policies

- Books We Recommend

- Classroom Management

- Community-Developed Resources

- Compassion & Self-Compassion

- Course Design & Development

- Course-in-a-box for New CU Educators

- Enthusiasm & Teaching

- First Day Tips

- Flexible Teaching

- Grants & Awards

- Inclusivity

- Learner Motivation

- Making Teaching & Learning Visible

- National Center for Faculty Development & Diversity

- Open Education

- Student Support Toolkit

- Sustainaiblity

- TA/Instructor Agreement

- Teaching & Learning in the Age of AI

- Teaching Well with Technology

University Center for Teaching and Learning

Self-assessment, self assessment.

Self-assessments allow instructors to reflect upon and describe their teaching and learning goals, challenges, and accomplishments. The format of self-assessments varies and can include reflective statements, activity reports, annual goal setting and tracking, or the use of a tool like the Wieman Teaching Practices Inventory. Teaching Center staff can offer individual instructors feedback on their self-assessments and recommendations for how to use results to improve teaching. The Teaching Center can also help schools and departments select, design, and teach instructors to use self-assessment tools.

Sample Self-Assessment Tools

- The Teaching Practices Inventory , a 72-item reflective, self-reporting tool developed by Carl Wieman and Sarah Gilbert, was created for instructors teaching undergraduate STEM courses. It helps instructors determine the extent to which they use research-based teaching practices.

- The Teaching Perspectives Inventory , a 45-item inventory that can be used to determine your teaching orientation. This inventory can be a helpful tool for reflection and improvement of teaching. It can also help you prepare to write or revise a statement of teaching philosophy .

- Instructor Self-Evaluation , created by the Measurement and Research Division of the Office of Instructional Resources at the University of Illinois Urbana

- The Inventory of Inclusive Teaching Strategies, created by the University of Michigan’s CRLT

- Faculty Teaching Self-Assessment form, created by Central Piedmont Community College

- Faculty Self-Evaluation of Teaching , created by the University of Dayton, contains self-evaluation rubrics, a narrative self-evaluation form, and several series of reflective questions.

Resources and Readings for Self-Assessment

Blumberg, P. (2014). Assessing and improving your teaching: Strategies and rubrics for faculty growth and student learning . Jossey-Bass.

Collins, J. B., & Pratt, D. D. (2011). The Teaching Perspectives Inventory at 10 Years and 100,000 respondents: Reliability and validity of a teacher self-report inventory. Adult Education Quarterly, 61 (4), 358–375. ( NOTE: To access this content, you must be logged in or log into the University Library System.)

Holmgren, R.A. (2004, March 26). Structuring self-evaluations. Allegheny College.

Rico-Reintsch, K. I. (2019). Using faculty self-evaluation as an innovative tool to improve university courses. Revista CEA, 5 (10), 69-81. doi:10.22430/24223182.1445

Wieman, C. & Gilbert, S. (2014). The Teaching Practices Inventory: A new tool for characterizing college and university teaching in mathematics and science. CBE Life Sciences Education, 13 (3). doi: 10.1187/cbe.14-02-0023

- Important dates for the summer term

- Generative AI Resources for Faculty

- Student Communication & Engagement Resource Hub

- Summer Term Finals Assessment Strategies

- Importing your summer term grades to PeopleSoft

- Enter your summer term grades in Canvas

- Alternative Final Assessment Ideas

- Not sure what you need?

- Accessibility Resource Hub

- Assessment Resource Hub

- Canvas and Ed Tech Support

- Center for Mentoring

- Creating and Using Video

- Diversity, Equity and Inclusion

- General Pedagogy Resource Hub

- Graduate Student/TA Resources

- Remote Learning Resource Hub

- Syllabus Checklist

- Student Communication and Engagement

- Technology and Equipment

- Classroom & Event Services

- Assessment of Teaching

- Classroom Technology

- Custom Workshops

- Open Lab Makerspace

- Pedagogy, Practice, & Assessment

- Need something else? Contact Us

- Educational Software Consulting

- Learning Communities

- Makerspaces and Emerging Technology

- Mentoring Support

- Online Programs

- Teaching Surveys

- Testing Services

- Classroom Recordings and Lecture Capture

- Creating DIY Introduction Videos

- Media Creation Lab

- Studio & On-Location Recordings

- Video Resources for Teaching

- Assessment and Teaching Conference

- Diversity Institute

- New Faculty Orientation

- New TA Orientation

- Teaching Center Newsletter

- Meet Our Team

- About the Executive Director

- Award Nomination Form

- Award Recipients

- About the Teaching Center

- Annual Report

- Join Our Team

- Featured Articles

- Report Card Comments

- Needs Improvement Comments

- Teacher's Lounge

- New Teachers

- Our Bloggers

- Article Library

- Featured Lessons

- Every-Day Edits

- Lesson Library

- Emergency Sub Plans

- Character Education

- Lesson of the Day

- 5-Minute Lessons

- Learning Games

- Lesson Planning

- Subjects Center

- Teaching Grammar

- Leadership Resources

- Parent Newsletter Resources

- Advice from School Leaders

- Programs, Strategies and Events

- Principal Toolbox

- Administrator's Desk

- Interview Questions

- Professional Learning Communities

- Teachers Observing Teachers

- Tech Lesson Plans

- Science, Math & Reading Games

- Tech in the Classroom

- Web Site Reviews

- Creating a WebQuest

- Digital Citizenship

- All Online PD Courses

- Child Development Courses

- Reading and Writing Courses

- Math & Science Courses

- Classroom Technology Courses

- Spanish in the Classroom Course

- Classroom Management

- Responsive Classroom

- Dr. Ken Shore: Classroom Problem Solver

- A to Z Grant Writing Courses

- Worksheet Library

- Highlights for Children

- Venn Diagram Templates

- Reading Games

- Word Search Puzzles

- Math Crossword Puzzles

- Geography A to Z

- Holidays & Special Days

- Internet Scavenger Hunts

- Student Certificates

Newsletter Sign Up

Search form

The power of reflection and self-assessment in student learning.

Learning is so much more than facts. Facts can be memorized and forgotten. But real learning stays with you for life. It involves developing critical thinking skills, problem-solving abilities, and the capacity for self-improvement. Reflection and self-assessment are vital in deepening understanding, fostering growth, and enhancing student learning.

Reflection Involves Contemplation and Self-Analysis

Reflection is thinking deeply about one's experiences, actions, and thoughts. When students focus on these, they connect theory and practice, and their learning takes on a whole new direction. Through reflection, students can better understand the underlying concepts, ideas, and principles they have encountered, leading to more profound subject matter comprehension.

Try one-minute essays. At the end of a lesson, ask your students to write down their thoughts for one minute. What did they struggle with? What were they good at? The simple act of writing down their thoughts will start a deeper self-analysis process.

By reflecting on their thinking, students can recognize their own strengths and weaknesses, leading to more effective learning strategies and problem-solving skills. When students are given the time and wherewithal to reflect, they develop accountability for their own learning process.

Self-Assessment Follows Self-Reflection

Self-assessment is closely linked to reflection and involves students evaluating their learning and performance. It empowers students to take ownership of their education by actively participating in the evaluation process. Through self-assessment, students develop a deep sense of responsibility and accountability for their progress, contributing to intrinsic motivation and a growth mindset.

Within your grading rubric, allow your students to grade themselves. Did they feel like they gave their all? Could they have done better? Allowing your students the chance to be honest with their work will stimulate academic responsibility.

By examining their work, students can identify their strengths and weaknesses, enabling them to set realistic goals and develop strategies to improve their learning outcomes. Self-assessment also encourages students to take risks and embrace challenges, as they see these as opportunities for growth rather than failures.

Show them the path to continuous improvement, where students are not afraid to make mistakes but view them as valuable learning experiences.

Combine the Two to Develop Critical Thinking Skills

How often do we ask our students to think critically? We need to ask ourselves if they have developed those skills. Thankfully, one significant benefit of reflection and self-assessment is gaining critical thinking skills.

Critical thinking involves analyzing information, evaluating evidence, and making informed judgments. Through reflection, students are encouraged to question assumptions, challenge their own beliefs, and consider alternative perspectives.

By critically examining their experiences and knowledge, students can develop a deeper understanding of the subject matter and become more independent thinkers. Furthermore, they engage in higher-order thinking processes, such as analyzing, synthesizing, and evaluating. These skills are essential not only for academic success but also for lifelong learning and professional development.

Students Begin Looking at the Process, Rather than the Outcome

When students engage in reflection and self-assessment, they shift their focus from grades and external validation to the learning process. They begin to see challenges and setbacks as opportunities for growth and improvement rather than as indicators of failure. This mindset is a breeding ground for resilience, perseverance, and a love for learning.

Recently there has been a shift among high school seniors; they celebrate their college rejection letters, rejoicing in the fact that they put themselves out there and know their failure is only another opportunity for growth.

Students become more willing to take risks, seek feedback, and embrace new challenges, knowing their abilities can be developed over time. When students can reflect on their learning experiences, they develop a deeper connection to the material. They become active participants in their own education rather than passive recipients of information.

And that, as educators, makes our hearts soar!

Motivation and Engagement Come Through Reflection and Self-Assessment

By assessing their progress and setting goals, students become more motivated to strive for excellence and take responsibility for their learning outcomes. Reflection also provides students with a sense of purpose and meaning, as they can see the relevance and application to real-life situations. This intrinsic motivation is a powerful driver for sustained engagement and continuous improvement both in and out of the classroom.

As educators, creating opportunities for students to reflect on their learning experiences and assess their progress is crucial. By doing so, we equip them with the necessary skills and mindset to become lifelong learners who can confidently and purposefully navigate the world's complexities.

EW Lesson Plans

EW Professional Development

Ew worksheets.

Sign up for our free weekly newsletter and receive top education news, lesson ideas, teaching tips and more! No thanks, I don't need to stay current on what works in education! COPYRIGHT 1996-2016 BY EDUCATION WORLD, INC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. COPYRIGHT 1996 - 2024 BY EDUCATION WORLD, INC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

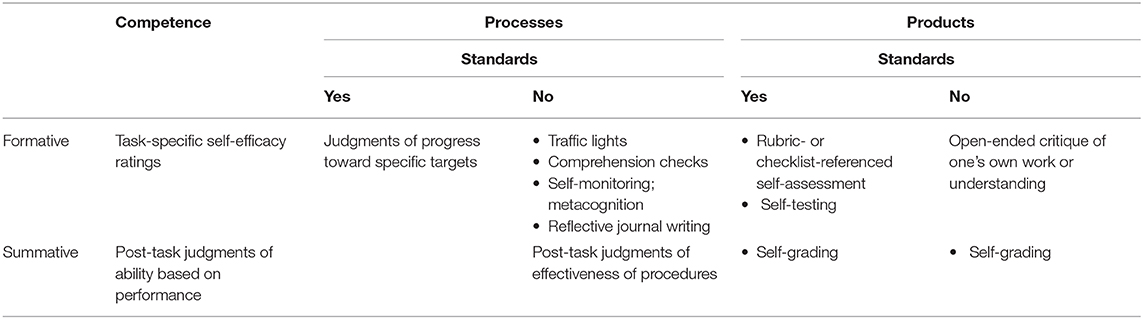

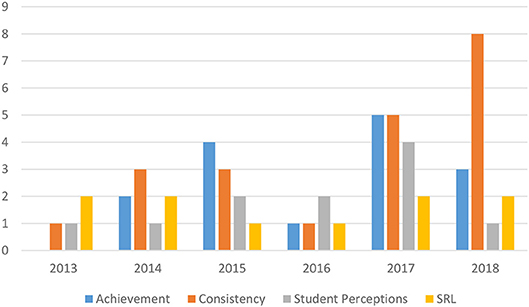

People also looked atSystematic review article, a critical review of research on student self-assessment.