- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Advance Articles

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- Why Submit?

- About Journal of Communication

- About International Communication Association

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Media stereotypes and prejudice, toward the dynamic of self-reinforcing effects, overview of the empirical work and hypotheses, study 1: prejudice-based selective exposure, study 2: effects of forced exposure, study 3: self-selected exposure and preference-based reinforcement, integrated analysis (studies 2 and 3): net-effect perspective, study 4: net-effect perspective (replication), general discussion, supplementary material, data availability.

- < Previous

Media stereotypes, prejudice, and preference-based reinforcement: toward the dynamic of self-reinforcing effects by integrating audience selectivity

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Florian Arendt, Media stereotypes, prejudice, and preference-based reinforcement: toward the dynamic of self-reinforcing effects by integrating audience selectivity, Journal of Communication , Volume 73, Issue 5, October 2023, Pages 463–475, https://doi.org/10.1093/joc/jqad019

- Permissions Icon Permissions

The media portray various social groups stereotypically, and studying the effects of these portrayals on prejudice is paramount. Yet, audience selectivity—inherent within today’s high-choice media environments—has largely been disregarded. Relatedly, the predominance of forced-exposure designs is a source of concern. This article proposes the integration of audience selectivity into media stereotype effects research. Study 1 ( N = 1,166) indicated that prejudiced individuals tended to approach prejudice-consistent stereotypical news and avoid prejudice-challenging counter-stereotypical news. Using a forced-exposure experiment, study 2 ( N = 380) showed detrimental effects of prejudice-consistent news and beneficial effects of prejudice-challenging news. Relying on a self-selected exposure paradigm, study 3 ( N = 1,149) provided evidence for preference-based reinforcement. Study 4’s “net-effect perspective” ( N = 937) indicated that operationalizing exposure as forced or self-selected can lead to different interpretations of actual societal effects. The findings emphasize the key role played by audience selectivity when studying media effects.

The media portray many social categories, such as minority groups, in a stereotypical way ( Billings & Parrott, 2020 ). This is problematic, as media depictions often represent the main, if not the only, source of information for citizens ( Ramasubramanian & Murphy, 2014 ). Previous research has already acknowledged the importance of studying the effects of exposure to media stereotypes on essential outcomes, such as prejudice. This line of research indicates that while exposure to prejudice-consistent stereotypical depictions can elicit detrimental effects, exposure to prejudice-challenging counter-stereotypical depictions can lead to beneficial effects ( Holt, 2013 ; Mastro & Tukachinsky, 2011 ; Ramasubramanian, 2011 ; Saleem et al., 2017 ).

Yet, the predominance of forced-exposure experiments in previous research on the effects of media stereotypes (e.g., Arendt, 2013 ; Kroon et al., 2016 ; Oliver, 1999 ; Schmuck et al., 2017 ) is a source of concern, as it disregards audience selectivity . Indeed, in the fragmented media environments of today, citizens can choose to expose themselves to content that confirms their preexisting views ( Ramasubramanian & Murphy, 2014 ). From this perspective, some scholars have argued that media effects can be conceptualized as preference-based reinforcement ( Cacciatore et al., 2016 ). Accordingly, an almost exclusive reliance on forced-exposure experiments with “captive participants” ( Druckman et al., 2012 , p. 430) may not suffice. This is because even if a forced-exposure experiment shows, for example, the beneficial effects of prejudice-challenging news, we do not know whether prejudiced individuals would actually read this kind of content in their everyday life. Rather, knowledge on both aspects—i.e., whether individuals select certain types of content and whether exposure elicits causal effects —is helpful for a thorough understanding of the media stereotype effect process.

We contribute to the literature in three important ways. Building upon recent advances in the theorizing on media effects in general ( Cacciatore et al., 2016 ; Knobloch-Westerwick, 2015 ; Slater, 2007 ), we (1) integrate audience selectivity. The effects of media stereotype exposure are conceptualized as a process occurring over time, combining both strands of research: selective exposure and effects. This is the primary theoretical contribution. We report on four studies, demonstrating the added value of integrating audience selectivity by studying preference-based reinforcement and the dynamic of self-reinforcing effects . As a second theoretical contribution, the present paper (2) investigated the role of approach and avoidance tendencies for selective exposure. Previous work has already acknowledged that the two tendencies may result in biased news choice ( Garrett, 2009 ; Jang, 2014 ; Schmuck et al., 2020 ). It is of theoretical importance to treat the two tendencies as separate ( Schmuck et al., 2020 ), because prejudiced individuals can seek prejudice-consistent news without avoiding prejudice-challenging news, and vice versa. There is limited knowledge on the role of both tendencies. As a methodological contribution, the present paper (3) contributes to closing the gap between reality (the high-choice media environments of today) and the methodology (the predominance of forced-exposure designs in existing work). Empirical evidence indicates that operationalizing exposure as forced or self-selected can lead to different interpretations of actual societal effects. Thus, scholars should increasingly think about the use of the self-selected-exposure paradigm as a supplement to forced-exposure experiments . Although both exposure paradigms are relevant, when used in combination , they may help to deepen our understanding.

Stereotypes can be defined as associations between a social category and attributes ( Greenwald et al., 2002 ). Stereotypes are typically simple, overgeneralized, widely accepted, and often resistant to change. Human information processing relies on stereotypes as they reduce the complexity of the social world by serving to stabilize, make predictable, and make manageable a given person’s view on social reality ( Snyder, 1981 ). Unfortunately, the “world outside” often stands in stark contrast to the “pictures in our heads,” as Lippmann (1922) noted. In fact, stereotypes are often inaccurate insofar as most of the time it is simply wrong that all representatives of a given social category show a given attribute. Such overgeneralizations are especially problematic when it comes to stereotypes that include negatively valenced attributes. Importantly, the association of a social category with attributes such as “rapist” or “thief” is likely to be related to an antipathy toward this social category, that is, prejudice ( Allport, 1954 ).

On a most basic level, the concept of a stereotype is agnostic about the valence of the attributes. They can be negatively valenced (e.g., criminal), positively valenced (e.g., diligent), or rather neutral (e.g., tall), as stereotypes are conceptualized on a cognitive level ( Greenwald et al., 2002 ). However, most studies on the detrimental effects of exposure to media stereotypes on prejudice have focused on attributes with a negative valence and have thus studied the effects of prejudice-consistent stereotypical media content (see Billings & Parrott, 2020 ). Consistently, studies on the beneficial effects on prejudice reduction have focused heavily on the effects of prejudice-challenging counter-stereotypical media content—depictions of the social category that go against the widely shared (prejudice-consistent) stereotype (see Billings & Parrott, 2020 ). We also directed our attention to prejudice-consistent stereotypical and prejudice-challenging counter-stereotypical media content.

There is evidence for the detrimental effects of exposure to prejudice-consistent depictions, as well as—albeit to a substantially lesser extent—for the beneficial effects of exposure to prejudice-challenging depictions ( Holt, 2013 ; Mastro & Tukachinsky, 2011 ; Power et al., 1996 ; Ramasubramanian, 2011 ; Saleem et al., 2017 ). Yet, the available evidence comes with some caveats. Although some work utilized nonrandomized observational survey studies with known limitations regarding causal interpretations (e.g., Arendt & Northup, 2015 ; Dixon, 2008 ; Mastro et al., 2007 ; Ramasubramanian, 2013 ; Schemer, 2012 ), most studies on the effects of media stereotypes have utilized experiments relying on forced exposure (e.g., Arendt, 2013 ; Oliver, 1999 ; Schmuck et al., 2017 ). The limits of forced-exposure experiments become evident when today’s high-choice media environments are considered. Following Bennett and Iyengar (2008) , Cacciatore and colleagues (2016) argued that such environments increasingly allow media users to be paired with content that fits with their preexisting views, implicating how media users tend to mostly rely on highly homophilic self-selected content. Ramasubramanian and Murphy (2014) argued in a similar vein, explaining that the media users of today “exercise greater authority when deciding what type of messaging they will allow themselves to be exposed to” (p. 396). The predominance of the forced-exposure paradigm in previous effects research does not do justice to the characteristics of fragmented, high-choice media environments. Audience selectivity must be better accounted for in our theorizing and empirical work. We need to know both whether individuals select certain types of content and whether exposure to this content elicits effects.

We now theorize on the media stereotype effect process, aiming to integrate audience selectivity into the study of the effects of exposure to media stereotypes. This theorizing guided our empirical work and owed much to existing writings focused on the importance of audience selectivity in the study of media effects in general ( Cacciatore et al., 2016 ; Knobloch-Westerwick, 2015 ; Slater, 2007 ). Two general ideas are constitutive for our theorizing:

Prejudice-based selective exposure

As a first general idea, we assumed that prejudice predicts the selection of news, such that it causes people to opt for congenial content and to fend off challenging content. Thus, prejudiced predispositions are assumed to facilitate the approach to prejudice-consistent content and hinder the selection of prejudice-challenging content. This prejudice-based selective exposure is a form of attitude-based selective exposure (e.g., Arendt et al., 2019 ) given that prejudice is conceptualized as a negative attitude toward a social category ( Allport, 1954 ; Dovidio et al., 2010 ). It is driven by a self-consistency motive ( Knobloch-Westerwick, 2015 ) that governs selective exposure insofar as individuals prefer news that aligns with their attitudes, a phenomenon also known as confirmation bias ( Knobloch-Westerwick & Kleinman, 2012 ).

Note that there can be two different tendencies that result in biased news choice ( Garrett, 2009 ; Jang, 2014 ; Schmuck et al., 2020 ): the tendency to approach prejudice-consistent news and the tendency to avoid prejudice-challenging news. Treating the two phenomena as separate is crucial for theory development ( Schmuck et al., 2020 ), because prejudiced individuals can seek prejudice-consistent stereotypical news without avoiding prejudice-challenging counter-stereotypical news, and vice versa. Avoidance-related tendencies have often been explained by cognitive dissonance theory ( Festinger, 1957 ): Prejudiced individuals avoid prejudice-challenging counter-stereotypical news as they may anticipate emotional discomfort resulting from exposure. Conversely, the self-consistency idea, as theorized in the Selective Exposure Self- and Affect-Management (SESAM) model ( Knobloch-Westerwick, 2015 ), conceptualizes news choice as an outcome of a general self-management toward consistency. Of note, this is a broader theoretical idea that can explain both avoidance and approach tendencies. Unfortunately, approach and avoidance tendencies “have received scant research attention thus far” ( Schmuck et al., 2020 , p. 158, see also Garrett, 2009 ). Previous media research, largely stemming from the political communication literature, provides evidence for the relevance of both ( Garrett, 2009 ; Jang, 2014 ; Schmuck et al., 2020 ). However, there is clearly a knowledge gap, especially in the media stereotype domain.

Preference-based reinforcement

As a second general idea, we assumed that exposure to (self-selected) media content can elicit a (reinforcement) effect on prejudice. As already noted, there is evidence from forced-exposure experiments for both the detrimental effects of prejudice-consistent depictions and the beneficial effects of prejudice-challenging depictions ( Holt, 2013 ; Mastro & Tukachinsky, 2011 ; Ramasubramanian, 2011 ; Saleem et al., 2017 )—with known limitations regarding interpretations of actual societal effects, especially in the context of high-choice media environments (see above). Importantly, the combination of both general ideas—prejudice-based selective exposure and (reinforcement) effects—forms the process we label as preference-based reinforcement : Prejudiced individuals prefer news that is congenial to their prejudiced views, and exposure to self-selected (prejudice-consistent) media content, in turn, can reinforce their prejudiced views. The strength of preference-based reinforcement, conceptualized as a process occurring over time, can thus depend on both the strength of the prejudice-based selective exposure and the (reinforcement) effect of (self-selected) exposure. Thus, neither a selective-exposure study nor a forced-exposure experiment used in isolation allow for a thorough understanding of the effect process. Evidence for preference-based reinforcement in the media stereotype domain is pending.

Additional theorizing on actual societal effects: net-effect perspective

Due to the high societal relevance of phenomena such as racism or sexism, we especially aimed to focus our attention on the interpretations of effects obtained in individual studies. We highlighted the question about actual societal effects: What is the net effect of both prejudice-based selective exposure and (reinforcement) effects? Our working hypothesis was that it can lead to different interpretations of actual societal effects (i.e., total effects occurring outside the “lab”) if exposure is operationalized as forced or self-selected: Even if a forced-exposure experiment shows beneficial effects from prejudice-challenging counter-stereotypical news, estimates of actual societal effects are questionable when not additionally assessing whether prejudiced individuals would actually read this content in their everyday life. The net-effect perspective considers both in conjunction: selective exposure and effects. We tentatively assumed that an estimate of actual societal effects can be ascertained best when forced-exposure and self-selected-exposure designs are used in combination . The strength of a combined use has already been acknowledged in other fields, such as political science ( Arceneaux & Johnson, 2013 ; De Benedictis-Kessner et al., 2019 ), political communication ( Stroud et al., 2019 ), psychology ( Johnston, 1996 ; Johnston & Macrae, 1994 ), and media psychology ( Dahlgren, 2021 ). An investigation in the media stereotyping domain is still pending. We provide more details on the net-effect perspective below.

We now outline our formal hypotheses [Hs] and research questions (RQs) that are based on the theorizing outlined above. Study 1 is a selective-exposure study, aimed to test the hypothesis that prejudice predicts news choice (H1). Furthermore, we asked about the role of approach and avoidance tendencies (RQ1). Study 2 used a forced-exposure experiment and we predicted that exposure to prejudice-challenging counter-stereotypical news would reduce prejudice (H2.1), whereas exposure to prejudice-consistent stereotypical news would increase prejudice (H2.2). Whereas studies 1 and 2 echoed the separate strands of previous research—i.e., selective-exposure and forced-exposure effects—,study 3 combined both strands by investigating the dynamic of self-reinforcing effects. We hypothesized a pattern consistent with preference-based reinforcement, that is, a reinforcement effect elicited by exposure to the self-selected content (H3). In addition, and as outlined in detail below, we aimed to estimate actual societal effects in an integrated analysis of the data of both forced (study 2) and self-selected (study 3) exposure (net-effect perspective). RQ2 asked whether estimates of actual societal effects would be different when operationalizing exposure as forced or self-selected. Finally, we conducted a replication study also using a net-effect perspective (study 4).

The empirical work was grounded in the stereotype of the “criminal Afghan asylum seeker,” which is relevant in Austria where the studies were conducted. The focus on this target stereotype seemed appropriate due to several reasons. On a more general level, the study of media stereotypes of refugees is an important avenue in research (Billings & Parrot, 2020). More specifically, there seems to be a widely shared antipathy toward Afghan asylum seekers in Austria (and other European countries), presumably stimulated by the “European refugee crisis” in 2015 and (the news reporting of) negatively valenced key events about criminal Afghan asylum seekers in the aftermath, including many stories of sexual harassment and rape (see Kohlbacher et al., 2020 ). Of note, a breeding ground for prejudice toward Afghan asylum seekers—the majority of whom are Muslim—may also be a broader anti-Muslim prejudice ( Strabac & Listhaug, 2008 ). Furthermore, news coverage on this social category is highly stereotypical, as a content analysis of Austrian newspapers showed ( Steiger, 2021 ). This content analysis found that “on every other day,” a (negatively valenced) prejudice-consistent stereotypical news article appeared. News, as was argued, made “Afghans dangerous, aggressive and criminal people.” Importantly, prejudice-consistent articles tended to be highly arousing, including emotional words and threatening visuals, and they frequently included crimes such as rape. Conversely, prejudice-challenging counter-stereotypical articles were rare. If published, these articles had a positive valence, and it was “striking that the positive reporting [was] often limited to their ability to integrate” (i.e., positive role-model stories of successful integration). These articles tended to be more pallid compared with prejudice-consistent articles. Of note, in these prejudice-challenging articles, Afghans got the chance to speak out and thus to be subjects in the news coverage rather than merely being objects of (negative crime) coverage. This content-analytic evidence guided the development of the stimulus materials in the empirical work, aiming to ensure high external validity.

We collected data for the first three studies simultaneously, and randomly allocated each participant ( N = 2,695 participants across the three studies) to one of the three studies. This combined data-collection approach did not allow us to adjust subsequent studies to the results of a preceding one. However, this was not necessary for tests of our a priori hypotheses. The random allocation procedure ensured that the samples were comparable. The latter is relevant for our integrated analysis combining data from studies 2 and 3 (i.e., net-effect perspective). Study 4 ( N = 937) is a replication study using a net-effect perspective and data were collected after the first three studies. Note that we bought all samples from a commercial market research company, which is well known in Austria and has experience in conducting comparable web-based studies. We used age, gender, and education as the quota variables. The samples for all four studies roughly corresponded to the Austrian population in terms of the quota variables.

Ethics statement

The IRB-COM of the Department of Communication, University of Vienna, approved all four empirical studies (studies 1–3 = Number ID: 20211202086, dated December 3, 2021; study 4 = Number ID: 20221024055, dated October 26, 2022).

The aim of study 1 was to test for prejudice-based selective exposure (H1). We also investigated the role of approach and avoidance tendencies (RQ1). We conducted a large web-based survey with a sample from the Austrian general population ( N = 1,166) based on quota-sampling techniques (age, gender, education). News choice was operationalized with a headline-choice task that had already been used in previous research (e.g., Galdi et al., 2012 ). In each individual trial, participants were presented with two headlines and were asked to choose the one that they preferred reading. We used headlines to measure prejudice-based selective exposure because this content dimension is relevant across different media outlets and genres.

Male (52.1%) and female respondents (47.6%) were nearly equally represented in our sample; three participants chose the “other” option. The majority had no high school diploma (64.9%), one-quarter had a high school diploma (23.9%), and the minority had a university degree (11.2%). Participants ranged in age between 18 and 92 years ( M = 47.74, SD = 16.05).

News choice: headline-choice task

News choice was measured with 10 target trials. In each trial, participants were presented with two headlines and were asked to choose one of them. Participants were randomly allocated to one of three experimental conditions with a specific variation in the target news-choice trials, consistent with our aim of investigating the role of approach and avoidance tendencies: In the first condition ( pos/neg , n = 393), participants could decide between a (positively valenced) prejudice-challenging counter-stereotypical (coded as 0) and a (negatively valenced) prejudice-consistent stereotypical (coded as 1) headline: Do those who show more prejudice toward Afghan asylum seekers prefer to choose the prejudice-consistent depiction of Afghan asylum seekers compared with prejudice-challenging depictions? We saw this as the primary condition to test for prejudice-based selective exposure, as these trials provided both prejudice-consistent stereotypical and prejudice-challenging counter-stereotypical depictions within each news-choice trial. This allowed for a straightforward test of H1, which posited that prejudice predicts news choice. Higher values on the sum score of the 10 target trials indicate a greater tendency to select prejudice-consistent news relative to prejudice-challenging news ( M = 4.91, SD = 3.24, range = 0–10).

The remaining two variants of this task were used to address RQ1 on the role of approach and avoidance tendencies. In the second condition, participants decided between a positively valenced prejudice-challenging (coded as 0) and a neutral (coded as 1) headline ( pos/neutral , n = 384): Does prejudice toward Afghan asylum seekers hinder the selection of prejudice-challenging news? For prejudiced individuals, higher values indicate a greater tendency to avoid prejudice-challenging news ( M = 6.03, SD = 2.57, range = 0–10). In the third condition, participants decided between a neutral (coded as 0) and a negatively valenced prejudice-consistent (coded as 1) headline ( neutral/neg , n = 389): Does prejudice toward Afghan asylum seekers facilitate the approach toward prejudice-consistent stereotypical news? Higher values indicate a greater tendency to approach prejudice-consistent news ( M = 4.50, SD = 2.837, range = 0–10).

We used the same set of 10 prejudice-consistent (e.g., “Fatal rape: Afghan asylum seekers abuse a girl”), prejudice-challenging (e.g., “Successful integration: Positive stories from Afghan asylum seekers”), and neutral headlines (e.g., “We need water from morning to evening”) across the three news-choice conditions.

By randomly pairing these headlines, we created pairs of headlines. These pairs were consequently used for all participants. Note that these headlines were based on real headlines from actual news coverage in the news archives identified in our research. This aimed to ensure high external validity. Importantly, the depiction of Afghan asylum seekers in our headlines corresponds to findings of a recent content analysis ( Steiger, 2021 ; see above). Thus, we acknowledged that prejudice-consistent (prejudice-challenging) headlines provided negatively (positively) valenced depictions of Afghan asylum seekers and tended to be more (less) arousing. The latter is consistent with basic psychological research showing that the relationship between valence and arousal is asymmetrical in that negatively valenced concepts tend to elicit higher arousal ratings than positively valenced concepts do ( Võ et al., 2009 ). For the prejudice-consistent and prejudice-challenging headlines, it was not seen as being appropriate to match stereotypical and counter-stereotypical content in terms of emotional arousal (see Steiger, 2021 ). We emphasized external validity.

Given that this decision may raise internal validity concerns, we decided to measure a given participant’s preference for valenced and arousing content, and used these two predispositions to news choice as covariates in the analysis: A total of 10 additional headline-choice trials were used that had already been used in previous studies ( Arendt et al., 2016 , 2019 ). Afghan asylum seekers were not mentioned in these choice trials. First, we measured the tendency to read positively valenced (e.g., “The sun and the warm temperature make people feel happy,” coded as 1) compared with negatively valenced (e.g., “Meteorological disturbance causes massive damage,” coded as 0) headlines. We used five choice trials, and higher values indicate a stronger preference for positively valenced headlines ( M = 3.01, SD = 1.46, range = 0–5). Second, we measured the tendency to read emotionally arousing articles. We used less arousing (e.g., “Dog bites a child on the leg,” coded as 0) and more arousing (e.g., “Aggressive fighting dog bites poor child,” coded as 1) headlines. Again, we used five trials, and higher values indicate a stronger preference for emotionally arousing headlines ( M = 1.84, SD = 1.39, range = 0–5). The full list of headlines can be found in the Online Supplementary Material (OSM) ( Supplementary Table 1 ).

We used 10 items to measure prejudice. Two of them used a 7-point bipolar scale to measure general negative affective reactions toward Afghan asylum seekers (i.e., whether participants see them as good or bad , positive or negative ). The remaining eight items asked participants to rate each of eight statements (e.g., “Asylum seekers from Afghanistan enrich life and society in Austria,” “Afghan asylum seekers are more prone to violence than others”) on a 7-point scale ranging from strongly disagree (coded as 1) to strongly agree (coded as 7). All statements pointing to a favorable attitude were reverse coded. Higher values indicate more prejudice ( M = 4.92, SD = 1.35, α = .92). A factor analysis confirmed a one-factor solution.

Statistical analysis

We relied on hierarchical multiple regression models and predicted the news-choice score by age, gender, dummy-coded education, preference for positively valenced news, preference for emotionally arousing news (all in step 1), and prejudice (step 2). The change in R 2 in the second step assesses whether prejudice predicts news choice over and above the influence of controls. Given that only three participants chose the “other” gender option and we wanted to include gender as a control—dummy-coding is not appropriate for this low number of participants choosing the other option, we report on the analysis without participants choosing the “other” option. However, models without gender as a control and including these three participants provided very similar results. Zero-order correlations can be found in the OSM ( Supplementary Table 2 ).

To conduct a formal test of moderation , that is, a test of whether effect coefficients indicative of prejudice-based selective exposure significantly differed between the three conditions (i.e., pos/neg, pos/neutral, and neutral/neg), we conducted a multigroup analysis by using the structural equation modeling software AMOS. We defined path models ( df = 0), as noted in the OLS regressions reported above. Importantly, we examined the fit of the model when freely estimating the effect coefficients “prejudice => news choice” relative to a model in which this coefficient was constrained to be equal in all three conditions [see Hayes et al. (2013) for this procedure]. We were interested in whether constraining this coefficient resulted in a decrement in fit, a pattern that would be consistent with a moderation effect, answering RQ1.

Results and discussion

H1 predicted prejudice-based selective exposure and RQ1 questioned the influence of approach and avoidance tendencies. We only report the coefficients of prejudice below. However, full models can be found in the OSM ( Supplementary Tables 3–5 ).

When participants were asked to choose between prejudice-challenging and prejudice-consistent headlines ( pos/neg condition ), prejudice predicted news choice, Δ F (1, 381) = 291.17, Δ R 2 = 0.358, p < .001. The analysis indicated a very strong effect coefficient, B = 1.42, 95% confidence interval (CI) [1.25–1.58], SE = 0.08, β = 0.61, p < .001. Consistent with H1, the more prejudice a given participant showed, the greater their tendency was to select prejudice-consistent stereotypical news relative to prejudice-challenging counter-stereotypical news.

When participants were asked to choose between a prejudice-challenging and a neutral headline ( pos/neutral condition ), prejudice elicited an effect on news choice as well, Δ F (1, 376) = 150.85, Δ R 2 = .278, p < .001. Although the effect size was descriptively lower compared with the one obtained in the pos/neg condition, prejudice strongly predicted news choice as well, B = 1.07, 95% CI [0.90–1.24], SE = 0.09, β = .55, p < .001. The analysis also indicated a significant finding when participants were asked to choose between a neutral and a prejudice-consistent headline ( neutral/neg condition ), Δ F (1, 381) = 50.13, Δ R 2 = 0.090, p < .001. Although the effect coefficient was descriptively smaller, B = 0.67, 95% CI [0.48–0.85], SE = 0.09, β = 0.32, p < .001, prejudice still predicted the tendency to select prejudice-consistent news.

A formal test of moderation across the three conditions provided evidence for moderation, Δχ 2 (2) = 35.29, p < .001. This indicated that the strength of prejudice-based selective exposure significantly differed between the three conditions. An additional formal test of moderation analyzing the difference between the pos/neutral condition and the neutral/neg condition provided evidence for moderation, Δχ 2 (2) = 9.99, p = .002. Given that the neutral headlines were identical in these conditions, this difference indicated that prejudice was a stronger predictor in news-choice trials that included prejudice-challenging counter-stereotypical news compared with trials that included prejudice-consistent stereotypical news.

With prejudiced individuals in mind, we can interpret this finding such that prejudiced individuals tend to approach prejudice-consistent news and, to a greater extent, avoid prejudice-challenging news. We focused on prejudiced individuals in the present research, as it is this segment of the population that represents a threat to an open and humane society and thus requires special scholarly attention. However, the specific interpretation of the role of approach or avoidance tendencies depends on the level of prejudiced predispositions. When considering unprejudiced individuals , the interpretation is reversed: The effect of prejudice on news choice in the neutral/neg condition would instead indicate the strength of the avoidance of prejudice-consistent news; conversely, an effect of prejudice on news choice in the pos/neutral condition would indicate an approach toward prejudice-challenging news. Supplementary Figure 1 provides a visualization of this basic idea. Note that we conducted an additional analysis (see OSM for details), showing that, in rather prejudiced individuals, the strength of the avoidance tendency triggered by prejudice-challenging news was significantly stronger compared with the approach tendency triggered by prejudice-consistent news. Conversely, in rather unprejudiced individuals, the strength of the approach tendency triggered by prejudice-challenging news was significantly stronger compared with the avoidance tendency triggered by prejudice-consistent news.

The finding that the pos/neg condition showed an even stronger effect coefficient compared with the other two conditions, Δ χ 2 (2) = 25.30, p < .001, is consistent with the idea that avoidance and approach tendencies both contributed to biased news choice. In a nutshell, the findings indicated that both avoidance and approach tendencies influenced news choice , answering RQ1. Of interest, the findings also indicated that prejudice-challenging counter-stereotypical news triggered a stronger form of prejudice-based news-choice bias compared with prejudice-consistent stereotypical news.

Our strong focus on external validity when creating the dichotomous news-choice trials may raise internal validity concerns. We acknowledge that our strong focus on external validity should not hinder us from providing a detailed assessment of internal validity issues. Thus, stimulated by comments raised within the review process, we conducted two additional empirical studies focusing on the relevant internal validity concerns (for details, see the OSM section “Additional Evidence Related to Internal Validity Concerns”). This evidence indicated that prejudice-based selective exposure was still observable (1) when using news-choice trials that were matched in terms of arousal and valence and (2) when using a design with a strong focus on internal validity that compares effect size estimates between a condition using headlines that include the stereotype-related group concept (e.g., “ Afghan stabbed wife with a Stanley knife”) with a condition using a matched “control” headline without the stereotype-related group concept (“ Man stabbed wife with a Stanley knife”). This additional evidence is consistent with the conclusions drawn from the evidence reported above.

Study 2 tested for the causal effects of forced exposure to prejudice-challenging counter-stereotypical and prejudice-consistent stereotypical news (H2.1 and H2.2), also relevant for RQ2 (see below). This web-based study ( N = 380) relied on a design with three experimental groups (i.e., prejudice-challenging, control, and prejudice-consistent) with a repeated measurement of prejudice (i.e., before and after forced exposure).

Female (46.2%) and male (53.8%) participants were nearly equally represented. The majority had no high school diploma (62.7%), about a quarter had a high school diploma (24.4%), and a minority had a university degree (12.9%). Participants ranged in age between 18 and 76 years ( M = 45.44, SD = 16.00).

Experimental manipulation

Participants were randomly allocated to one of three experimental groups. In the prejudice-consistent stereotype group ( n = 127), participants read an article in which Afghan asylum seekers were accused of having raped a girl, headlined “Leonie (13) was drugged and raped by Afghans in Vienna in June: She died as a result of these acts.” This article was based on real news content, and such Afghan-related rape stories are frequently present in the Austrian news coverage ( Steiger, 2021 ). Participants allocated to the prejudice-challenging counter-stereotype group ( n = 127) read an article that provided positive role models, headlined “Many of the refugees from Afghanistan were able to gain a foothold: There are many positive examples of integration.” Again, this article was based on real news content, and such positive role-model stories that run counter to the “criminal Afghan asylum seeker” stereotype are relevant in the Austrian news coverage ( Steiger, 2021 ). The selection of these articles was guided by our aim of ensuring high external validity. In the control group ( n = 126), participants read an article about the importance of water, headlined “We need water from morning to evening: For drinking, for cooking, for washing and much more.” Efforts were made to hold relevant factors constant. For example, all articles included the same number of pictures (i.e., three) and had a similar text length (i.e., stereotypical article = 956 words, counter-stereotypical article = 888 words, and control article = 944 words). The three articles can be found in the OSM ( Supplementary Appendix I ).

We used the same measure as in study 1. Consistent with recent scholarship that encourages the adoption of repeated measure designs to increase precision ( Clifford et al., 2021 ), we relied on a repeated measures design and administered the prejudice measure before ( M = 5.00, SD = 1.47, α = 0.94) and after ( M = 5.05, SD = 1.51, α = 0.95) forced exposure.

We relied on a 3 (experimental group: prejudice-challenging, control, prejudice-consistent) × 2 (time of measurement: prejudice measured before and after exposure) mixed analysis of variance. Whereas the experimental group was a between-subjects factor, the time of measurement was a within-subjects factor. A significant effect of exposure would be indicated by a significant interaction (i.e., a change in prejudice over time, depending on the experimental condition: an increase in the prejudice-consistent group and a decrease in the prejudice-challenging group).

H2 predicted the effects of forced exposure to news on prejudice. Specifically, we predicted a reduction in prejudice after exposure to prejudice-challenging news (H2.1) and an increase in prejudice after exposure to prejudice-consistent news (H2.2). The mixed ANOVA provided a significant main effect of time, F (1, 377) = 5.28, p = .022, η 2 = 0.014, and the absence of a main effect of the experimental condition, F (2, 377) = 0.37, p = .694, η 2 = .002. More importantly for the test of the hypotheses, there was a significant interaction effect, F (2, 377) = 26.70, p < .001, η 2 = 0.124. Of interest, whereas forced exposure to prejudice-challenging news reduced prejudice, Δ M = −0.13, 95% CI [−0.19 to −0.06], SD = 0.37, t (126) = −3.86, p < .001, exposure to prejudice-consistent news increased prejudice, Δ M = 0.26, 95% CI [0.18–0.34], SD = 0.46, t (126) = 6.36, p < .001. There was no significant change in prejudice in the control group, Δ M = 0.02, 95% CI [−0.06 to 0.10], SD = 0.44, t (125) = 0.49, p = .628. Figure 1 provides a visualization.

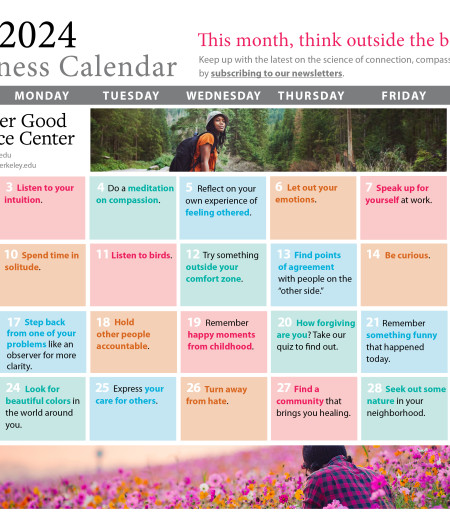

Effects of forced exposure to prejudice-challenging counter-stereotypical, neutral (control group), and prejudice-consistent stereotypical news on prejudice, measured before and after exposure (study 2).

Notes. The figure shows the means of prejudice for each experimental group, measured before and after exposure. Before–after comparisons ( p values) are based on t -tests, reported in detail in the body of the text: Whereas forced exposure to prejudice-challenging counter-stereotypical news content reduced prejudice, exposure to prejudice-consistent stereotypical content increased prejudice; we did not observe a change in the control group.

Of interest, an additional moderation analysis showed that the effects of prejudice-consistent and prejudice-challenging news were not significantly different in those with low or high values of prejudiced predispositions (see Supplementary Appendix II : Additional Moderation Analysis). Taken together, study 2 provided evidence for substantial effects of forced exposure.

Studies 1 and 2 echoed the separate strands of research on selective exposure and effects. Study 3 combined them by relying on self-selected exposure, allowing us to investigate preference-based reinforcement (H3). In this large web-based study ( N = 1,149), we measured prejudice, and subsequently asked participants to select one of two news items. In contrast to study 1’s selective-exposure design (where the task consisted solely of selecting headlines but did not involve actual exposure to the story selected), participants read the selected article. Afterward, we measured prejudice again. This design is similar to those used in other fields, such as political science ( Arceneaux & Johnson, 2013 ), psychology ( Johnston & Macrae, 1994 ), political communication ( Stroud et al., 2019 ), or media psychology ( Dahlgren, 2021 ).

Consistent with the operationalization of news choice in study 1, we used three news-choice conditions to which participants were randomly allocated. Participants were given the opportunity to choose between the same articles used in study 2. Had we used a choice task including all three article options, the chosen option would have had to have been interpreted relative to the other two. A dichotomous task allows for more specific interpretations because there is only one other option (but see study 4). In the first condition ( pos/neg condition , n = 386), participants could decide between a prejudice-challenging counter-stereotypical (“Integration success story: Positive stories from Afghans,” coded as 0) and a prejudice-consistent stereotypical article (“Fatal rape: Afghans abuse a girl,” coded as 1). The majority (81.1%) chose the prejudice-challenging article. In the second condition ( pos/neutral condition , n = 381), participants could decide between a prejudice-challenging (coded as 0) and a neutral (“We need water from morning to evening,” coded as 1) article. Approximately half of the participants (45.1%) chose the prejudice-challenging article. In the third condition ( neutral/neg condition , n = 382), participants decided between a neutral and a prejudice-consistent article. Only a minority (23.3%) chose the prejudice-consistent article.

Male (52.7%) and female (47.3%) respondents were nearly equally represented in our sample; one participant chose the “other” option (0.1%). The majority had no high school diploma (63.3%), about a quarter had a high school diploma (24.4%), and a minority had a university degree (12.4%). Participants ranged in age between 18 and 83 years ( M = 46.13, SD = 15.49).

We used the same measure as in studies 1 and 2. We administered the measure before ( M = 4.96, SD = 1.42, α = 0.93) and after ( M = 4.92, SD = 1.48, α = 0.94) self-selected exposure.

Predispositions in news choice

Consistent with study 1, we controlled for the participant’s preference for valenced ( M = 3.20, SD = 1.47) and arousing ( M = 1.65, SD = 1.40) content.

We used a two-step approach. In a first step, we ran (a) three separate hierarchical binary logistic regression models to predict the dichotomous news choice by prejudice measured before exposure, separately for each of the three conditions (i.e., pos/neg, pos/neutral, and neutral/neg). We controlled for age, gender, education, preference for positively valenced news, and preference for emotionally arousing news. Next, we (b) ran three separate hierarchical multiple regression models, predicting prejudice measured after exposure by prejudice measured before exposure (to control for autoregressive effects), controls (all in the first step), and news choice (i.e., self-selected exposure; second step). The latter model indicates whether self-selected exposure predicted a change in prejudice over time. In a second step, we used the structural equation modeling software AMOS to test for prejudice-based reinforcement by specifying a mediator model (independent variable = pre-prejudice; mediator = self-selected exposure; dependent variable = post-prejudice). Controls were included as well. This analysis allowed us to estimate the indirect effect (i.e., pre-prejudice’s effect on post-prejudice via self-selected exposure). We simultaneously estimated three path models ( df = 0), one for each condition (i.e., pos/neg, pos/neutral, and neutral/neg). Figure 2 provides a visualization.

Conceptual model of preference-based reinforcement (study 3).

Notes. We used the structural equation modeling software AMOS to estimate three mediator models ( df = 0), one for each condition (pos/neg, pos/neutral, and neutral/negative). The figure visualizes the direct effects (solid arrows) and the indirect effect (dashed arrow). Age, gender, dummy-coded education, and predispositions in news choice (i.e., preference for positively valenced news, preference for emotionally arousing news) were used as controls. See the body of the text for effect estimates.

H3 predicted a pattern consistent with preference-based reinforcement. We report on the conceptual variables below. Full models can be found in the OSM ( Supplementary Tables 6–11 ).

Pos/Neg condition

We started by looking at participants who chose between the prejudice-challenging and prejudice-consistent articles. First, prejudice measured before exposure predicted news choice (i.e., increased the likelihood of selecting the prejudice-consistent article relative to the prejudice-challenging article), B = 0.57, SE = 0.13, Wald = 21.08, df = 1, odds ratio = 1.77, 95% CI [1.39–2.26], p < .001. Self-selected exposure to the prejudice-consistent article (relative to the prejudice-challenging article), in turn, predicted an increase in prejudice measured post-exposure, B = 0.29, 95% CI [0.16–0.42], SE = 0.07, β = 0.08, t = 4.31, p < .001. Second, our mediation analysis showed an (unstandardized) indirect effect, coeff = 0.019, 95% CI [0.011–0.031], p = .001. These findings are consistent with preference-based reinforcement and thus support H3.

Pos/neutral condition

Similar findings could be observed in participants who selected between the prejudice-challenging article and the neutral article. First, prejudice measured before self-selected exposure predicted news choice (i.e., increased the likelihood of avoiding the prejudice-challenging article), B = 0.80, SE = 0.10, Wald = 67.62, df = 1, odds ratio = 2.23, 95% CI [1.84–2.70], p < .001. Self-selected exposure to the prejudice-challenging article (relative to the neutral article), in turn, predicted a decrease in prejudice measured post-exposure, B = 0.34, 95% CI [0.23–0.44], SE = 0.05, β = 0.11, t = 6.37, p < .001. (Note that the reported effect coefficient has a positive sign due to our codes: prejudice-challenging article = 0, neutral article = 1.) We also obtained a significant indirect effect, coeff = 0.054, 95% CI [0.039–0.072], p = .002.

Neutral/Neg condition

A slightly different pattern was obtained when analyzing data provided by participants who selected between the neutral and the prejudice-consistent article. Prejudice measured before self-selected exposure did not significantly predict news choice in the logistic regression model (albeit that the effect coefficient points in the predicted direction), B = 0.18, SE = 0.11, Wald = 2.63, df = 1, odds ratio = 1.20, 95% CI [0.96–1.49], p = .105. However, self-selected exposure to the prejudice-consistent article (relative to the neutral article) predicted an increase in prejudice measured post-exposure, B = 0.29, 95% CI [0.16–0.43], SE = 0.06, β = 0.09, t = 4.58, p < .001. Our mediation analysis showed a significant indirect effect, coeff = 0.007, 95% CI [0.001–0.015], p = .0497. Although the indirect effect was significant in a statistical sense, the effect size obtained seemed to be weaker on a descriptive level compared with the other two conditions.

Formal test of moderation

To conduct a formal test of moderation (i.e., a test of whether effect coefficients indicative for preference-based reinforcement significantly differed between the three conditions), we conducted a multigroup analysis, as already reported above (see study 1). We tested whether the effect of pre-prejudice on post-prejudice through its influence on news-choice/self-selected exposure significantly differed among the three choice conditions (i.e., pos/neg, pos/neutral, and neutral/negative). We defined path models, as reported in the OLS regressions reported above. Importantly, we examined the fit of the model when freely estimating the effect coefficients “pre-prejudice => self-selected exposure” and “self-selected exposure => post-prejudice” (see Figure 2 ) relative to a model in which these effect coefficients were constrained to be equal in all three conditions. We were interested in whether constraining these effect coefficients indicative for preference-based reinforcement resulted in a decrement in fit, a pattern that would be consistent with a moderation effect. Indeed, we found evidence for moderation, Δ χ 2 (2) = 41.74, p < .001.

Of note, the effect coefficients reported above indicated that the difference between the three choice conditions was strongly observable for selective exposure (“pre-prejudice => self-selected exposure,” see the logistic regression models reported above). Conversely, the sizes of the reinforcement effects were very similar among the three conditions (“self-selected exposure => post-prejudice,” see the multiple regression models reported above). Therefore, we re-ran the formal moderation analysis reported above two additional times. In the first additional model, we only constrained the selective-exposure path (i.e., “pre-prejudice => self-selected exposure”) and in the second additional model, we only constrained the reinforcement path (i.e., “self-selected exposure => post-prejudice”). Whereas the first model provided evidence for moderation, Δ χ 2 (2) = 41.28, p < .001, the second model did not, Δ χ 2 (2) = 0.46, p = .794. This indicated that the difference in preference-based reinforcement obtained was driven by differences in the strength of prejudice-based selective exposure, emphasizing the crucial role played by audience selectivity.

As reported above, the coefficients (expressed as odds ratios ) were different on a descriptive level: 1.77 (pos/neg), 2.23 (pos/neutral), and 1.20 (neutral/neg). Whereas the first two were significant ( p ’s < .001), the latter was not ( p = .105). Thus, it appeared that the conditions which included prejudice-challenging counter-stereotypical news elicited a stronger bias during selective exposure. We conducted a formal test of moderation by examining the fit of the model when freely estimating the effect coefficient “pre-prejudice => self-selected exposure” relative to a model in which this coefficient was constrained (i.e., pos/neg and pos/neutral versus neutral/neg). This analysis indicated that prejudice especially predicted news choice when prejudice-challenging counter-stereotypical news was included as a choice option, Δ χ 2 (1) = 21.52, p < .001. This is consistent with the findings from study 1.

We now present an integrated analysis, questioning whether the interpretation of actual societal effects depends on the exposure paradigm used (RQ2): Even if a forced-exposure experiment indicates, for example, detrimental effects of prejudice-consistent stereotypical news, we do not know whether individuals would actually read this kind of content in their everyday life. Answering both the question of (1) whether individuals select certain types of content and of (2) whether exposure elicits effects was assumed to be helpful for estimating actual societal effects. The net-effect perspective focuses on these two questions in conjunction. Using the net-effect perspective, we operationalized the “societal effect” as the pre–post change in the sample mean in prejudice when looking at the data for the whole samples from studies 2 and 3, respectively.

We based the integrated analysis on the following observations: Study 2 showed that forced exposure to the prejudice-consistent article elicited a detrimental increase in prejudice (Δ M = 0.26), and forced exposure to the prejudice-challenging article elicited a beneficial reduction in prejudice (Δ M = −0.13). Note that an equally high number of individuals (i.e., 33%) read the prejudice-consistent, neutral, and prejudice-challenging articles in study 2’s forced-exposure experiment due to random assignment. Conversely, in study 3’s self-selected-exposure paradigm, many participants did not actually read the prejudice-consistent stereotypical article when they were able to freely choose among options: Descriptive statistics, calculated over all three of study 3’s choice conditions, indicated that 42% selected the prejudice-challenging counter-stereotypical article compared with only 14% who selected the prejudice-consistent stereotypical article. (The remaining participants selected the neutral article.) Note that in the case of the absence of any selection bias, one would expect a selection likelihood of 33% for each of the three articles in both studies 2 and 3. This is despite the fact that the designs of both studies differ (see Supplementary Appendix III for details). Given that the prejudice-challenging article elicited a beneficial effect and more people actually chose it in study 3, we speculated that the net effect on prejudice in the self-selected-exposure paradigm (study 3) would be more beneficial compared with the effect observed in the forced-exposure paradigm (study 2). As a post hoc hypothesis, we hypothesized an interaction effect insofar as the pre–post change in the sample mean in prejudice depended on the paradigm utilized (i.e., forced vs. self-selected exposure).

This “macro-level” net-effect perspective thus focuses on “societal” effects (i.e., pre–post changes in prejudice observed for the whole samples from studies 2 and 3, simulating prejudice levels in two different “societies”)—in contrast to the individual-level analysis reported in study 2’s and study 3’s sections. Therefore, we now utilize a bird’s eye view: We looked at the change in prejudice (sample means) measured before and after exposure within each “society.” Of note, we did not include (experimental) news-exposure factors in this analysis but only looked at prejudice, simulating a “macro-level” view of these two “societies”: Did these “societies” change in prejudice depending on whether their “citizens” were forced to read a given news item or could freely choose to select their preferred one?

We relied on a two-way 2 (type of exposure: forced or self-selected exposure, i.e., data from study 2 or 3) × 2 (prejudice measured before and after exposure) mixed analysis of variance to determine whether the strength (and direction) of the “societal effect” depended on the type of exposure (forced versus self-selected), which would be indicated by a significant interaction. Indeed, the mixed ANOVA provided a significant interaction, F (1, 1525) = 10.12, p = .001, η 2 = 0.007. Figure 3A provides a visualization. In the “society” in which people could freely choose their news—only 14% read the prejudice-consistent stereotypical news but a total of 42% read the prejudice-challenging counter-stereotypical news—, there was a net decrease in prejudice , t (1146) = −2.78, p = .006. Conversely, in the “society” whose citizens were forced to read an article—a total of 33% read the prejudice-consistent and prejudice-challenging news, respectively—, we did not observe a comparable beneficial change. Conversely, we even obtained a net increase in prejudice , t (379) = 2.16, p = .031.

Net-effect perspective: differences in estimated “societal effects.” (A) Merged data (studies 2 and 3). (B) Replication data (study 4).

Notes. This figure shows the sample means of prejudice measured before and after exposure when relying on the forced-exposure paradigm versus the self-selected-exposure paradigm. This analysis aims to simulate a “macro-level” view of these two “societies”: Did these “societies” change in prejudice depending on whether their “citizens” were forced to read a given news item or could freely choose to select their preferred one? Panel (A) visualizes an integrated analysis based on data from the samples of study 2 (forced-exposure paradigm) and study 3 (self-selected-exposure paradigm). Whereas the forced-exposure paradigm indicated a net increase in prejudice due to media exposure, the self-selected-exposure paradigm indicated a net reduction. Panel (B) visualizes data from the replication study (study 4), replicating the observed effect pattern. Evidence indicates that it can make a fundamental difference for the interpretation of actual societal effects if the findings are based either on the forced- or on the self-selected-exposure paradigm. The findings emphasize the key role played by audience selectivity when studying media effects.

These findings are supportive of the claim that it can make a fundamental difference for the interpretation of actual societal effects depending on whether the findings are based on the forced- or self-selected-exposure paradigm. In fact, estimates of actual societal effects even moved in the opposite direction. This finding deserves scholarly attention: In the forced-exposure paradigm, researchers may tend to focus their attention on the detrimental effect of prejudice-consistent stereotypical news, possibly coming to a rather pessimistic view on societal effects. However, when also considering findings from the self-selected-exposure paradigm (and thus considering audience selectivity), researchers may come to a less pessimistic view, as the majority of individuals simply avoided exposure to the prejudice-consistent stereotypical article. This emphasizes the key role played by audience selectivity when interpreting findings related to media effects phenomena observed in individual studies.

Given that the designs of studies 2 and 3 were different (i.e., a different number of news-choice options: three options in study 2’s forced-exposure design, corresponding to the three experimental groups, versus three separate dichotomous choice trials in study 3’ self-selected-exposure design; see Supplementary Appendix III for a detailed discussion), a replication study was conducted. The aim was to replicate the observed net-effect pattern reported above (see Figure 3A ) using a matched design.

Participants ( N = 937) of a quota-based sample (age, gender, education) who did not participate in the other three studies were randomly allocated to a forced-exposure condition ( n = 472) or a self-selected-exposure condition ( n = 465). In the forced-exposure condition, participants were randomly allocated to read the prejudice-consistent (33.9%), prejudice-challenging (33.7%), or the control (32.4%) article. In the self-selected-exposure condition, participants could select one of the three articles within one news-choice trial that included all three options. More participants selected the prejudice-challenging counter-stereotypical article (34.8%) compared with the prejudice-consistent stereotypical article (18.9%); the control article was selected by 46.2%.

Consistent with the integrated analysis of the merged data from studies 2 and 3 reported above, we relied on a two-way 2 (type of exposure: forced- or self-selected-exposure group) × 2 (prejudice measured before and after exposure) mixed ANOVA. Whether the strength (and direction) of the “societal effect” on prejudice depended on the type of exposure would be indicated by a significant interaction effect. Indeed, the mixed ANOVA produced a significant interaction effect, F (1, 935) = 8.60, p = .003, η 2 = 0.009. Figure 3B provides a visualization. Study 4 thus replicated the pattern observed in the merged analysis of data provided by studies 2 and 3 (see Figure 3A ). The findings from study 4 are thus also supportive of the claim that it can make a fundamental difference for the interpretation of actual societal effects if the findings are based either on the forced- or on the self-selected-exposure paradigm—also emphasizing the key role played by audience selectivity when studying the effects of exposure to media stereotypes.

The present research investigated the media stereotype effect process. In a nutshell, prejudiced predispositions influenced prejudice-consistent news choice and (self-selected) exposure, in turn, elicited a (reinforcement) effect on prejudice. The findings highlight the importance of considering audience selectivity. The study of preference-based reinforcement and thus the dynamic of self-reinforcing effects is, to the best of our knowledge, unprecedented in the research on media stereotypes—our primary theoretical contribution to the media stereotype literature. The findings are also important for recent theorizing on media effects in general that integrates audience selectivity into the effects perspective ( Cacciatore et al., 2016 ; Knobloch-Westerwick, 2015 ; Slater, 2007 )—we provide evidence from the media stereotype domain.

We also investigated the role of approach and avoidance tendencies, providing a theoretical contribution to the selective-exposure literature ( Garrett, 2009 ; Jang, 2014 ; Schmuck et al., 2020 ): Both tendencies are of theoretical importance, because individuals can seek prejudice-consistent stereotypical news without avoiding prejudice-challenging counter-stereotypical news, and vice versa. Evidence indicated that both tendencies played a significant role. Of note, study 1 found that participants preferred prejudice-consistent stereotypical news over neutral news . This challenges cognitive dissonance theory ( Festinger, 1957 ) as the only theoretical explanation for biased selective-exposure behavior, because neutral news should not elicit cognitive dissonance. Conversely, a self-consistency motive, as theorized in the SESAM model ( Knobloch-Westerwick, 2015 ), can explain both tendencies, including the finding from study 1 mentioned above. Of note, Schmuck et al. (2020) provided a similar finding in a different selective-exposure domain (political advertising).

The present research also offers an important methodological contribution for the practice of (future) research in the media stereotype domain: An integrated analysis, relying on a net-effect perspective, used data provided by both the self-selected-exposure and forced-exposure paradigms. Although forced exposure to prejudice-consistent stereotypical news elicited a detrimental effect on the increase in prejudice (study 2), many participants simply avoided reading this prejudice-consistent stereotypical news (study 3). Estimates of “societal effects” were different, depending on whether participants were forced to read given news content or could freely choose to select their preferred article. This observed pattern was replicated (study 4). Note that the net-effect perspective aimed at a more realistic estimation of actual societal effects. However, we are very careful when interpreting real-world implications, as, for example, the news-choice trials including the used headlines were highly specific (and thus still somewhat artificial) when compared with real-world news consumption. Both the forced- and the self-selected-exposure paradigms must still be seen as somewhat simplified compared with the complex media environment in the “world outside.” Therefore, even the self-selected-exposure paradigm cannot be viewed as a natural simulation of the “world outside.” Nevertheless, the commonly used forced-exposure paradigm has important limitations because it clearly fails to reflect the reality where much of the exposure is the result of audience selectivity. The self-selected-exposure paradigm places more attention on this fact. Based on our findings, we argue that scholars should think about increasingly using the self-selected-exposure paradigm as a supplement to forced-exposure experiments. Despite its limitations, when used in combination , both may allow for a better estimation of the real-world impact of media stereotypes. Importantly, we want to emphasize that we do not argue that the self-selected-exposure paradigm is more important than the forced-exposure paradigm or that forced-exposure experiments are useless. Conversely, the forced-exposure paradigm has several strengths, such as it allowing for high confidence in terms of causal interpretations. In addition, some media content in the “world outside” may be seen, at least partly, as “forced”: Individuals using social networking sites may be exposed to content they have chosen (self-selected exposure) and content they have not chosen (as in the forced-exposure paradigm; see Dahlgren, 2021 ). Thus, both paradigms are relevant.

Limitations and promising avenues for future research

We focused on prejudice-based selective exposure, theoretically strongly determined by a self-consistency motive, as outlined by Knobloch-Westerwick (2015) . However, her theorizing also emphasized self-enhancement and self-improvement motives. These additional motives may also play a role. In fact, Knobloch-Westerwick (2015) argued that when threats to the self are salient and negative affect is lingering, news choice will be especially driven by a self-enhancement motive insofar as individuals will then tend to select news content that they perceive will bolster their self. Consider social identity theory ( Tajfel & Turner, 1986 ): Individuals tend to categorize themselves and other salient social categories and their members into “us” versus “them.” A future study could test whether prejudice-based selective exposure is stronger when threats to the self are salient, or when a news user’s different social identities are primed. For example, does the strength of prejudice-based selective exposure increase when one’s own (ingroup) identity has been primed? In addition, Knobloch-Westerwick (2015) argued that when a need or an opportunity to advance one’s own performance and adaptation to the environment becomes salient, news choice will be especially driven by a self-improvement motive. In fact, Knobloch-Westerwick and Kleinman (2012) showed that information utility can override a confirmation bias. These individuals may still distance themselves from the presented view while still taking in the information. These are theoretically fruitful avenues worthy of future study.

A further limitation of the current work is that we only studied short-term effects. In fact, we did not use a temporally more distant follow-up measurement of prejudice to see whether there was a decay in effect size. The strength of the decay may depend on whether exposure was self-selected or forced: Are effects more enduring when news is self-selected? Relatedly, we only used a “one-shot” exposure treatment. Thus, we cannot say whether self-reinforcing effects change depending on the amount of cumulative exposure (see Arendt, 2015 ). It would therefore seem fruitful for a future study to use repeated sessions in which individuals can select news, for example, within consecutive days or weeks. Also relatedly, all participants in studies 2 and 3 were exposed either to prejudice-consistent stereotypical, prejudice-challenging counter-stereotypical, or neutral news content. Thus, we did not investigate the effect elicited by reading both prejudice-consistent and prejudice-challenging news. A future study could test the effects of such “competitive media stereotype environments.” We may find that there is no substantial (or only a slight) pre–post net change in prejudice when participants are exposed to prejudice-consistent stereotypical and prejudice-challenging counter-stereotypical news content under forced exposure. The effects of the articles may (more or less) cancel each other out. However, this may be different when using a self-selection paradigm. Consider prejudiced individuals. They could be asked to select between a prejudice-consistent and a prejudice-challenging article in a first step. Next, they could read the selected article. Afterward, they could be asked to read the second article. It is likely that the participants would rely on some form of motivated reasoning ( Kunda, 1990 ). Such a study may find a substantial effect arising from reading both articles in favor of the one they have selected.

Conclusions

Despite these limitations, the present project provides supporting evidence for the idea of preference-based reinforcement in the media stereotyping domain. Across four empirical studies, we studied the dynamic of self-reinforcing effects. Audience selectivity was a key factor. Future research could think about operationalizing exposure as forced and self-selected.

Supplementary material is available online at Journal of Communication online.

Conflicts of interest : None declared.

Research materials, including stimulus materials and data, can be requested by the author. Please, contact the author.

Allport G. W. ( 1954 ). The nature of prejudice . Addison-Wesley.

Google Scholar

Google Preview

Arendt F. ( 2013 ). Dose-dependent media priming effects of stereotypic newspaper articles on implicit and explicit stereotypes . Journal of Communication , 63 ( 5 ), 830 – 851 . https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12056

Arendt F. , Northup T. ( 2015 ). Effects of long-term exposure to news stereotypes on implicit and explicit attitudes . International Journal of Communication , 9 , 732 – 751 . Retrieved from https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/2691

Arendt F. ( 2015 ). Toward a dose-response account of media priming . Communication Research , 42 ( 8 ), 1089 – 1115 . https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650213482970

Arendt F. , Northup T. , Camaj L. ( 2019 ). Selective exposure and news media brands: Implicit and explicit attitudes as predictors of news choice . Media Psychology , 22 ( 3 ), 526 – 543 . https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2017.1338963

Arendt F. , Steindl N. , Kümpel A. ( 2016 ). Implicit and explicit attitudes as predictors of gatekeeping, selective exposure, and news sharing: Testing a general model of media-related selection . Journal of Communication , 66 ( 5 ), 717 – 740 . https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12256

Arceneaux K. , Johnson M. ( 2013 ). Changing minds or changing channels? Partisan news in an age of choice . University of Chicago Press .

Bennett W. L. , Iyengar S. ( 2008 ). A new era of minimal effects? The changing foundations of political communication . Journal of Communication , 58 ( 4 ), 707 – 731 . https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2008.00410.x

Billings A. , Parrott S. ( 2020 ). Media stereotypes: From ageism to xenophobia . Peter Lang .

Cacciatore M. A. , Scheufele D. A. , Iyengar S. ( 2016 ). The end of framing as we know it… and the future of media effects . Mass Communication and Society , 19 ( 1 ), 7 – 23 . https://doi.org/10.1080/15205436.2015.1068811

Clifford S. , Sheagley G. , Piston S. ( 2021 ). Increasing precision without altering treatment effects: Repeated measures designs in survey experiments . American Political Science Review , 115 ( 3 ), 1048 – 1065 . https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055421000241

Dahlgren P. M. ( 2021 ). Forced versus selective exposure: Threatening messages lead to anger but not dislike of political opponents. Journal of Media Psychology: Theories, Methods, and Applications . Advance online publication . https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-1105/a000302

De Benedictis-Kessner J. , Baum M. , Berinsky A. , Yamamoto T. ( 2019 ). Persuading the enemy: Estimating the persuasive effects of partisan media with the preference-incorporating choice and assignment design . American Political Science Review , 113 ( 4 ), 902 – 916 . https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055419000418

Dixon T. L. ( 2008 ). Crime news and racialized beliefs: Understanding the relationship between local news viewing and perceptions of African Americans and crime . Journal of Communication , 58 ( 1 ), 106 – 125 . https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2007.00376.x

Dovidio J. , Hewstone M. , Glick P. , Esses V. ( 2010 ). The SAGE handbook of prejudice, stereotyping and discrimination . Sage .

Druckman J. N. , Fein J. , Leeper T. J. ( 2012 ). A source of bias in public opinion stability . American Political Science Review , 106 ( 2 ), 430 – 454 . https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055412000123

Festinger L. ( 1957 ). A theory of cognitive dissonance . Stanford University Press .

Galdi S. , Gawronski B. , Arcuri L. , Friese M. ( 2012 ). Selective exposure in decided and undecided individuals: Differential relations to automatic associations and conscious beliefs . Personality & social psychology bulletin , 38 ( 5 ), 559 – 569 . https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167211435981

Garrett K. ( 2009 ). Politically motivated reinforcement seeking: Reframing the selective exposure debate . Journal of Communication , 59 ( 4 ), 676 – 699 . https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2009.01452.x

Greenwald A. G. , Banaji M. R. , Rudman L. A. , Farnham S. D. , Nosek B. A. , Mellott D. S. ( 2002 ). A unified theory of implicit attitudes, stereotypes, self-esteem, and self-concept . Psychological Review , 109 ( 1 ), 3 – 25 . https://doi.org/10.1037//0033-295X.109.1.3

Hayes A. , Matthes J. , Eveland W. ( 2013 ). Stimulating the quasi-statistical organ: Fear of social isolation motivates the quest for knowledge of the opinion climate . Communication Research , 40 ( 4 ), 439 – 462 . https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650211428608

Holt L. F. ( 2013 ). Writing the wrong: Can counter-stereotypes offset negative media messages about African Americans? Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly , 90 ( 1 ), 108 – 125 . https://doi.org/10.1177/1077699012468699

Jang S. ( 2014 ). Challenges to selective exposure: Selective seeking and avoidance in a multitasking media environment . Mass Communication and Society , 17 ( 5 ), 665 – 688 . https://doi.org/10.1080/15205436.2013.835425

Johnston L. ( 1996 ). Resisting change: Information-seeking and stereotype change . European Journal of Social Psychology , 26 ( 5 ), 799 – 825 . https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2420240505

Johnston L. , MaCrae C. ( 1994 ). Changing social stereotypes: The case of the information seeker . European Journal of Social Psychology , 24 ( 5 ), 581 – 592 . https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2420240505

Knobloch-Westerwick S. ( 2015 ). The selective exposure self- and affect-management (SESAM) model: Applications in the realms of race, politics, and health . Communication Research , 42 ( 7 ), 959 – 985 . https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650214539173

Knobloch-Westerwick S. , Kleinman S. B. ( 2012 ). Preelection selective exposure: Confirmation bias versus informational utility . Communication Research , 39 ( 2 ), 170 – 193 . https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650211400597

Kohlbacher J. , Lehner M. , Rasuly-Paleczek G. ( 2020 ). Afghan/inn/en in Österreich—Perspektiven von Integration, Inklusion und Zusammenleben [Afghans in Austria: Perspectives on integration, inclusion, and cohabitation]. Verlag ÖAW .

Kroon A. , van Selm M. , ter Hoeven C. , Vliegenthart R. ( 2016 ). Poles apart: The processing and consequences of mixed media stereotypes of older workers . Journal of Communication , 66 ( 5 ), 811 – 833 . https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12249

Kunda Z. ( 1990 ). The case for motivated reasoning . Psychological Bulletin , 108 ( 3 ), 480 – 498 . https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.108.3.480

Lippmann W. ( 1922 ). Public opinion . Macmillan .

Mastro D. , Behm-Morawitz E. , Ortiz M. ( 2007 ). The cultivation of social perceptions of Latinos: A mental models approach . Media Psychology , 9 ( 2 ), 347 – 365 . https://doi.org/10.1080/15213260701286106

Mastro D. , Tukachinsky R. ( 2011 ). The influence of exemplar versus prototype-based media primes on racial/ethnic evaluations . Journal of Communication , 61 ( 5 ), 916 – 937 . https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2011.01587.x

Oliver M. B. ( 1999 ). Caucasian viewers’ memory of Black and White criminal suspects in the news . Journal of Communication , 49 ( 3 ), 46 – 60 . https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1999.tb02804.x

Power J. , Murphy S. , Coover G. ( 1996 ). Priming prejudice: How stereotypes and counter-stereotypes influence attribution of responsibility and credibility among ingroups and outgroups . Human Communication Research , 23 ( 1 ), 36 – 58 . https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.1996.tb00386.x

Ramasubramanian S. ( 2011 ). The impact of stereotypical versus counter-stereotypical media exemplars on racial attitudes, causal attributions, and support for affirmative action . Communication Research , 38 ( 4 ), 497 – 516 . https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650210384854

Ramasubramanian S. ( 2013 ). Intergroup contact, media exposure, and racial attitudes . Journal of Intercultural Communication Research , 42 , 54 – 72 . https://doi.org/10.1080/17475759.2012.707981

Ramasubramanian S. , Murphy C. ( 2014 ). Experimental studies of media stereotyping effects. In Webster M. , Sell J. (Eds.), Laboratory experiments in the social sciences (pp. 385 – 402 ). Elsevier Academic Press . https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-404681-8.00017-0

Saleem M. , Prot S. , Anderson C. A. , Lemieux A. F. ( 2017 ). Exposure to Muslims in media and support for public policies harming Muslims . Communication Research , 44 ( 6 ), 841 – 869 . https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650215619214

Schemer C. ( 2012 ). The influence of news media on stereotypic attitudes toward immigrants in a political campaign . Journal of Communication , 62 ( 5 ), 739 – 757 . https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2012.01672.x

Schmuck D. , Matthes J. , Paul F. H. ( 2017 ). Negative stereotypical portrayals of Muslims in right-wing populist campaigns: Perceived discrimination, social identity threats, and hostility among young Muslim adults . Journal of Communication , 67 ( 4 ), 610 – 634 . https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12313

Schmuck D. , Tribastone M. , Matthes J. , Marquart F. , Bergel E. ( 2020 ). Avoiding the other side? An eye-tracking study of selective exposure and selective avoidance effects in response to political advertising . Journal of Media Psychology , 32 ( 3 ), 158 – 164 . https://doi-org.uaccess.univie.ac.at/10.1027/1864-1105/a000265