Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 17 April 2024

Malnutrition enteropathy in Zambian and Zimbabwean children with severe acute malnutrition: A multi-arm randomized phase II trial

- Kanta Chandwe 1 na1 ,

- Mutsa Bwakura-Dangarembizi 2 , 3 na1 ,

- Beatrice Amadi 1 ,

- Gertrude Tawodzera 2 ,

- Deophine Ngosa 1 ,

- Anesu Dzikiti 2 ,

- Nivea Chulu 1 ,

- Robert Makuyana 2 ,

- Kanekwa Zyambo ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5686-5319 1 ,

- Kuda Mutasa 2 ,

- Chola Mulenga 1 ,

- Ellen Besa ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5606-9435 1 ,

- Jonathan P. Sturgeon ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1318-1739 2 , 4 ,

- Shepherd Mudzingwa 2 ,

- Bwalya Simunyola 1 ,

- Lydia Kazhila 1 ,

- Masuzyo Zyambo 5 ,

- Hazel Sonkwe 5 ,

- Batsirai Mutasa 2 ,

- Miyoba Chipunza 1 ,

- Virginia Sauramba 2 ,

- Lisa Langhaug ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9131-8158 2 ,

- Victor Mudenda 1 ,

- Simon H. Murch ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3870-8229 6 ,

- Susan Hill 7 ,

- Raymond J. Playford ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1235-8504 8 , 9 ,

- Kelley VanBuskirk ORCID: orcid.org/0009-0004-9110-9059 1 ,

- Andrew J. Prendergast ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7904-7992 2 , 4 &

- Paul Kelly ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0844-6448 1 , 4

Nature Communications volume 15 , Article number: 2910 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

1120 Accesses

38 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Intestinal diseases

- Paediatric research

Malnutrition underlies almost half of all child deaths globally. Severe Acute Malnutrition (SAM) carries unacceptable mortality, particularly if accompanied by infection or medical complications, including enteropathy. We evaluated four interventions for malnutrition enteropathy in a multi-centre phase II multi-arm trial in Zambia and Zimbabwe and completed in 2021. The purpose of this trial was to identify therapies which could be taken forward into phase III trials. Children of either sex were eligible for inclusion if aged 6–59 months and hospitalised with SAM (using WHO definitions: WLZ <−3, and/or MUAC <11.5 cm, and/or bilateral pedal oedema), with written, informed consent from the primary caregiver. We randomised 125 children hospitalised with complicated SAM to 14 days treatment with (i) bovine colostrum ( n = 25), (ii) N-acetyl glucosamine ( n = 24), (iii) subcutaneous teduglutide ( n = 26), (iv) budesonide ( n = 25) or (v) standard care only ( n = 25). The primary endpoint was a composite of faecal biomarkers (myeloperoxidase, neopterin, α 1 -antitrypsin). Laboratory assessments, but not treatments, were blinded. Per-protocol analysis used ANCOVA, adjusted for baseline biomarker value, sex, oedema, HIV status, diarrhoea, weight-for-length Z-score, and study site, with pre-specified significance of P < 0.10. Of 143 children screened, 125 were randomised. Teduglutide reduced the primary endpoint of biomarkers of mucosal damage (effect size −0.89 (90% CI: −1.69,−0.10) P = 0.07), while colostrum (−0.58 (−1.4, 0.23) P = 0.24), N-acetyl glucosamine (−0.20 (−1.01, 0.60) P = 0.67), and budesonide (−0.50 (−1.33, 0.33) P = 0.32) had no significant effect. All interventions proved safe. This work suggests that treatment of enteropathy may be beneficial in children with complicated malnutrition. The trial was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov with the identifier NCT03716115.

Similar content being viewed by others

Sepsis-associated acute kidney injury: consensus report of the 28th Acute Disease Quality Initiative workgroup

Short-chain fatty acids: linking diet, the microbiome and immunity

The International Scientific Association of Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) consensus statement on the definition and scope of postbiotics

Introduction.

Despite 17 million annual worldwide cases of childhood severe acute malnutrition (SAM), and its high associated mortality when children are hospitalized with complications 1 , 2 , there have been few new treatments for over three decades for children with complicated SAM. Current management follows steps in the WHO guidelines launched in 1999 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 but there is an acknowledged lack of evidence for many interventions 1 , 7 and consensus that more trials are needed. In sub-Saharan Africa, HIV has had a major impact on SAM, causing higher mortality during 8 , 9 and after admission 2 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , complications like persistent diarrhoea 9 , and prolonged hospital admission.

Even after recovery from acute SAM, there are very common chronic consequences, including both stunting of linear growth and short- and long-term inhibition of neurodevelopmental potential 14 . The effects of chronic malnutrition upon cognitive functioning are particularly notable in the domains of attention, memory and learning, contributing to poor school performance 15 and corresponding with abnormalities on neuroimaging 16 . Such long-term consequences may not be averted by providing improved nutrition alone, as small intestinal absorption of nutrients and essential micronutrients is compromised by ongoing malnutrition enteropathy 17 . Effective treatment of malnutrition enteropathy is thus likely to have major benefits for the development of large numbers of children within resource-poor countries.

The small intestinal mucosal damage now recognised as malnutrition enteropathy was first recognised in SAM in the 1960s 18 , 19 . More recent studies confirm the very high frequency of malnutrition enteropathy in resource poor countries and an association between such gut inflammation and mortality in complicated SAM 20 . There is therefore considerable interest in malnutrition enteropathy, which varies from mild villus blunting and inflammation to a severe state with total villus atrophy similar to coeliac disease. Malnutrition enteropathy is characterised by severe epithelial lesions 21 , 22 accompanied by mucosal inflammation in the epithelium and lamina propria together with depletion of secretory cells 23 . The epithelial lesions permit microbial translocation from the gut lumen driving systemic inflammation 24 , 25 . Transcriptomic analysis of mucosal biopsies confirms links between inflammation, villus blunting, microbial translocation and epithelial leakiness 26 .

Recognising that fresh approaches are needed to ameliorate the mucosal damage that characterises malnutrition enteropathy we evaluated four potential therapies in a multi-arm, phase II, randomised controlled trial in two tertiary hospitals in southern Africa (Lusaka, Zambia and Harare, Zimbabwe) 27 . The Therapeutic Approaches to Malnutrition Enteropathy (TAME) trial tested the hypothesis that one or more of these therapies could reduce the severity of malnutrition enteropathy in children with SAM. Each intervention was chosen because of its potential for enhancing intestinal repair. Bovine colostrum contains abundant growth factors, including insulin-like and epidermal growth factors 28 , and demonstrates efficacy in ulcerative colitis 29 , 30 . N-acetyl glucosamine may restore the intestinal barrier since glycosylation is deficient in SAM 31 , 32 , and it has been shown to promote mucosal healing in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) 33 . Teduglutide improves nutrient absorption through mucosal regeneration in intestinal failure 34 , 35 . Budesonide suppresses inflammation with minimal systemic exposure in IBD 36 . A broad range of endpoints was chosen to assess several domains of pathophysiology 37 , 38 relevant to restoring mucosal integrity. The primary endpoint, a composite of faecal biomarkers (myeloperoxidase, α1-antitrypsin, and neopterin) was chosen to reflect mucosal inflammation and loss of barrier function. Secondary endpoints were chosen to reflect enterocyte damage (plasma intestinal fatty acid-binding protein) and the systemic response to microbial translocation (lipopolysaccharide-binding protein (LBP), C-reactive protein (CRP), soluble CD163, soluble CD14), alongside anthropometric measures of nutritional recovery, death, adverse events, diarrhoea, fever and recovery from oedema.

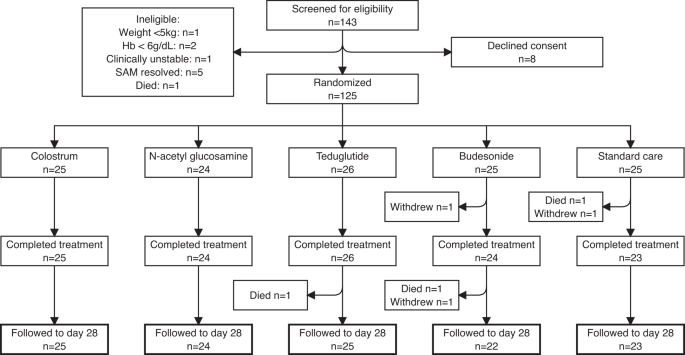

The TAME trial was conducted in the Children’s Hospital of University Teaching Hospital, Lusaka, and Sally Mugabe Hospital, Harare. The third planned site (Parirenyatwa Hospital, Harare) was closed to recruitment due to its use as a COVID-19 centre. Children hospitalised with complicated SAM were enrolled once they were considered stable and ready to transition to higher calorie intakes, to avoid anticipated high early mortality in this high-risk population. Of 143 children screened, 133 were eligible: 8 declined, leaving 125 children enrolled: 62 in Lusaka and 63 in Harare (Fig. 1 , Table 1 ), of whom 43% were female (Table 1 ). Causes of ineligibility were weight <5 kg ( n = 1), clinical instability ( n = 1), haemoglobin <6 g/dL ( n = 2), death prior to enrolment ( n = 1), or resolution of SAM ( n = 5). Children were randomised a median of 5.5 (range 1–21) days after admission (Table 2 ), following blood and stool collection to measure baseline biomarkers; no biomarker data were available from earlier in the hospital admission. One child died and two withdrew before day 15, so 122 children (98%) contributed outcome data (Fig. 1 ). Two further children died and one withdrew between the end of treatment and the day 28 follow-up visit. Adherence and completion were very high: 122/124 (98%) children who survived to day 15 received all planned doses.

One child died and two children withdrew before day 15, so day 15 endpoint data were available for 122 children for most endpoints, and 118 for the primary endpoint; all these children completed their allocated intervention and standard care and are included in the per protocol analysis. A further 2 children died and one withdrew between days 15 and 28. SAM, severe acute malnutrition. Hb, haemoglobin concentration.

Primary endpoint

The median day 15 composite faecal inflammatory score was lower in all treatment groups compared with the standard care group (Table 3 ). Using ANCOVA, with pre-specified P-value threshold of 0.10 and following adjustment for seven key covariates, pairwise comparisons showed the composite score in the teduglutide group was significantly lower than standard care (mean difference −0.89, 90%CI −1.69, −0.10, P = 0.07) (Table 4 ). Results were also stratified by site (Supplementary Table S1 ). In Harare both teduglutide and budesonide reduced the primary outcome compared to standard care, by 2.1 (90%CI 0.7, 3.5; P = 0.02) and 1.4 (0.06, 2.7; P = 0.09) respectively, but the effect was not significant in Lusaka (Supplementary Table S1 ). In the whole group, the ANCOVA model demonstrated no significant effect of sex, HIV infection, oedema, diarrhoea, or baseline weight-for-length Z-score (WLZ) on the faecal inflammatory score.

Secondary endpoints

Amongst secondary biomarker endpoints (Table 4 ), compared with standard care, budesonide reduced plasma CRP (mean reduction 5.2 mg/L; 90%CI 0.8, 9.6; P = 0.05) and sCD163 (mean reduction 405 ng/mL; 90%CI 73, 738; P = 0.05) while colostrum and N-acetyl glucosamine had effects only on CRP (reductions 5.9 mg/L; 90%CI 1.4, 10.3; P = 0.03, and 4.8 mg/L; 90%CI 0.5, 9.2; P = 0.07, respectively). There were notable site-specific differences in CRP, sCD14, sCD163 and iFABP (Supplementary Table S1 ). Transformation of secondary endpoints to approximate a normal distribution did not change the effects observed, except for colostrum, for which an effect was found on GLP-2 only when the values were transformed (Supplementary Table S2 ). N-acetyl glucosamine reduced mean days with diarrhoea by 89% (Table 4 ; ratio of NAG to standard care 0.11; 90%CI 0.04, 0.33; P = 0.001). None of the interventions affected days with fever or oedema, or change in weight, height, or MUAC.

Assessment of endoscopic biopsies

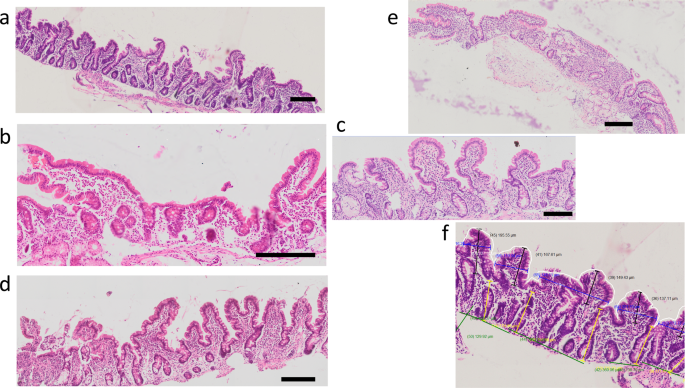

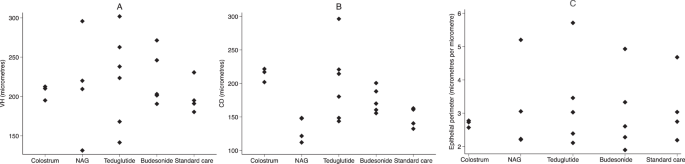

Of 62 children enrolled in Lusaka, endoscopy was carried out on 25 (5 colostrum, 4 N-acetyl glucosamine, 6 teduglutide, 5 budesonide, 5 Standard Care). Of the remainder, 9 children were unsuitable for anaesthesia (mainly upper respiratory infections), one child had no INR result available, 3 children missed endoscopy because no anaesthetist was available; and 24 children missed endoscopy because of instrument breakdowns. Representative specimens are shown in Fig. 2 . Morphometry in post-treatment biopsies showed significant differences in crypt depth (Fig. 3 ; P = 0.02 by Kruskal-Wallis test; by Dunn’s test P = 0.01 for colostrum and P = 0.049 for teduglutide compared to standard care).

Biopsies are from children treated with a colostrum, b N-acetyl glucosamine, c teduglutide, d budesonide, and e standard care. Morphometric analysis is shown in panel f . Scale bars show 200 μm. These biopsies were selected from 22 biopsies from 25 children: 6 in the teduglutide group, 5 in the colostrum group, 5 in the budesonide group, 5 in the standard care group, and 4 in the N-acetyl glucosamine group. Individual data from morphometric analysis are shown in Fig. 3 .

Measurements of villus height (VH) and crypt depth (CD) in 22 biopsies with satisfactory orientation obtained from children completing 14 days of treatment. a villus height ( P = 0.84 by Kruskal-Wallis test across all groups). b crypt depth ( P = 0.02 by Kruskal-Wallis test; by Dunn’s test P = 0.01 for colostrum and P = 0.049 for teduglutide). c, epithelial surface area. NAG, N-acetyl glucosamine. Source Data are provided as a Source Data File (Dataset 1).

Adverse events

A total of 102 clinical adverse events were reported (10 SAEs, 92 non-serious AEs) which did not differ significantly by treatment arm (Supplementary Table S3 ). No AEs or SAEs were adjudicated as related to the investigative products. There were no adverse events related to endoscopy, and no Adverse Events of Special Interest. Laboratory AEs did not differ by treatment allocation (Supplementary Table S4 ). Of the 10 SAEs observed, 3 (2% of the whole cohort) were deaths and 7 (6%) were prolonged hospitalisations or re-admission (Supplementary Table S3 ). Of the three deaths, only one (on day 3) occurred before day 15; the other two occurred on days 20 and 23. Deaths were attributed to fever with diarrhoea ( n = 1; Standard Care arm), tuberculosis ( n = 1; Teduglutide arm), and aspiration pneumonia ( n = 1; Colostrum arm). Seven readmissions or prolonged hospitalisations occurred, due to fever ( n = 2), deterioration of oedema ( n = 1), vomiting ( n = 1), respiratory distress ( n = 1), and a burn from a hot water bottle whilst in hospital ( n = 1). One SAE was a readmission for observation at the day 28 visit after a protocol violation, due to receiving double the protocol dose of budesonide; there were no clinical or laboratory consequences. One child receiving teduglutide was readmitted for vomiting to exclude intestinal obstruction (an Adverse Event of Special Interest) but the illness resolved uneventfully and was adjudicated as unrelated to the investigative product. Laboratory abnormalities occurred in 702 instances, including baseline abnormalities, but did not differ significantly between arms and were all adjudicated as unrelated to the investigative products (Supplementary Table S4 ).

Despite implementation of current treatment guidelines for complicated SAM, mortality remains unacceptably high, particularly in settings with high HIV burden. There is an urgent need for transformative approaches that modify underlying pathogenic pathways 39 . We identified intestinal mucosal damage as a promising target for intervention 27 . This multi-arm phase II clinical trial evaluated four potential new therapies to promote mucosal healing, which were each compared with standard care. Teduglutide showed benefit on the primary endpoint, a composite of three faecal inflammatory markers widely used to define enteropathy in malnourished children. Teduglutide is a GLP-2 agonist widely used in intestinal failure, a clinical syndrome with features in common with the more severe cases of malnutrition enteropathy. Our findings suggest that GLP-2 agonism similarly enhances mucosal healing in children with SAM. No other intervention significantly differed from standard care for the primary outcome. However, budesonide, colostrum and N-acetyl glucosamine reduced the systemic inflammatory marker CRP, which is potentially clinically important as CRP is a predictor of mortality 40 . The increase in crypt depth observed with teduglutide and bovine colostrum likely indicates enhanced mucosal regeneration, as these agents both showed some reductions in inflammatory biomarkers (faecal composite score for teduglutide, CRP for colostrum). N-acetyl glucosamine reduced diarrhoea, which is independently associated with mortality in SAM, potentially reflecting restoration of glycocalyx composition 32 and/or inhibition of enteropathogen colonisation 41 . Collectively, our data identify teduglutide as the leading candidate for future trials, but also suggest there may be benefits from the other treatments, which all have distinct mechanisms of action. This trial highlights the importance of measuring multiple biomarkers, which capture different pathological domains of malnutrition enteropathy. A larger-scale trial of single or combined interventions with outcomes including mortality and readmission is now warranted.

Our hypothesis was that one or more trial interventions could aid mucosal healing, reducing enteropathy, inflammation, and microbial translocation. We selected three faecal biomarkers of mucosal damage and inflammation as a composite primary endpoint, on which we based our sample size calculations. However, we acknowledged a priori that our interpretation would draw on the full range of endpoints, since no single biomarker or composite score captures the complexity of pathogenesis linking mucosal damage to mortality 27 . The effects of trial treatments on different secondary endpoints suggests that each may benefit specific domains of gut dysfunction in SAM 37 .

The potential usefulness of teduglutide is limited by its expense and subcutaneous route of administration. However, many therapies introduced at high prices fall in cost once volume of use increases. By contrast budesonide, which reduced the inflammatory markers CRP and sCD163, is far less costly and easier to administer. Neither should be implemented as part of treatment for SAM without further trial evidence, but the TAME trial demonstrates that use is likely to be safe, and confirms mucosal healing as a promising strategy in severe malnutrition. Although colostrum did not affect the primary endpoint, it increased both plasma levels of GLP-2 (though only after log transformation) and crypt depth. Colostrum contains GLP-2 at around 5 ng/ml and supplementation with colostrum in juvenile pigs undergoing intestinal resection increased plasma GLP-2 levels 42 .

As expected, adverse events were common but serious adverse events uncommon, and there were no events considered related to trial medications. The safety of long-term teduglutide has been assessed in intestinal failure and considered acceptable 35 . No Adverse Events of Special Interest were observed. A trial of mesalazine, another anti-inflammatory drug used in IBD, suggested safety in children with SAM 43 , and our data extend these findings by showing that these medications are also safe. Mortality was low compared to our historical data 9 , 11 . This may be due to the enhanced medical and nursing care usually associated with conduct of a clinical trial, but probably also relates to our caution in focusing on inclusion of clinically stable children. Given our experience of high early mortality in children with complicated SAM, we adopted this strategy to reduce the likelihood of serious adverse events in this phase II trial. In future it would appear desirable to bring forward treatments to the day of admission, when they might be of greatest potential benefit. Treatment duration was 14 days, representing the period of greatest mortality risk in hospitalised children; however, we and others have reported that unacceptably high mortality continues for 48 weeks following hospital discharge 2 , 11 , 13 . It is therefore possible that longer duration of therapies for mucosal healing could be of benefit.

We recognise several limitations. Due to restrictions on recruitment and difficulties transporting medicines and reagents during the COVID-19 pandemic, our enrolment was reduced. However, withdrawal and mortality were much lower than anticipated and we could therefore retain adequate power for the primary endpoint with a smaller sample size. Because this trial was conducted in hospital, adherence to medication was very high, with 98% of children completing intended therapy. This may be unattainable in real-world settings, but overall this trial demonstrated proof of concept for the therapies chosen. Our results were consistent across endpoint domains and biologically plausible for known mechanism of action of each agent, increasing confidence in our findings. Due to the short intervention duration, we saw limited impact on clinical outcomes such as growth. However, future trials powered for clinically important outcomes could explore the optimal timing, dosage and duration of intervention. There are also some challenges in interpreting the biomarkers used in this trial. Faecal biomarkers are subject to dilutional considerations, especially when a significant proportion of the trial participants have diarrhoea. It is also true that the biology of these biomarkers is not fully established. Markers such as myeloperoxidase and neopterin are elaborated by leukocytes, and reflect intestinal mucosal inflammation, but intestinal permeability and trafficking of leukocytes to the gut can be altered in the presence of systemic infections 44 , 45 . Neopterin is synthesised in response to interferon-γ and generally reflects Th1-mediated inflammation. α1-antitrypsin is usually considered a biomarker of protein loss into the gut, but transcriptomic data reveal that it is expressed in the mucosa 26 , 46 . These considerations need to be taken into account in future work. We have no ready explanation for the heterogeneity between study sites. We have previously noted mortality differences between Zambia and Zimbabwe, and there are minor differences in protocol implementation (such as when children are ready for discharge) which might explain some of these effects. This heterogeneity also needs to be taken into account in future work as it underlines the value of performing trials in different countries.

Our findings demonstrate a biologically plausible new treatment paradigm for children with complicated SAM. Intestinal damage is ubiquitous in children with SAM, driving systemic inflammation, contributing to stunting and developmental impairment and increasing mortality. No interventions for malnutrition enteropathy are currently available. We have shown that a short course of therapy added to standard care, aimed at restoring mucosal integrity, can ameliorate underlying pathogenic pathways. Further trials should evaluate these interventions for their effects on mortality, clinical recovery and long-term nutritional restoration to improve the outcomes of children with complicated SAM. Combinations of interventions would be interesting to evaluate in future trials since their distinct mechanisms of action and potential to target multiple domains of malnutrition enteropathy concurrently, may plausibly lead to greater mucosal healing and clinical recovery through synergistic effects.

Ethics approval was obtained from the University of Zambia Biomedical Research Ethics Committee (006-09-17), the National Health Research Committee of Zambia, the Zambia Medicines Regulatory Authority (CT 082/18), the Joint Research Ethics Committee of Harare Central Hospital (JREC/66/19), the Medicines Control Authority of Zimbabwe (CT/176/2019), and the Medical Research Council of Zimbabwe (MRCZ/A/2458). The trial was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The trial was monitored by a Data Safety and Monitoring Board. The trial was registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov (NCT03716115) and first posted on 23 rd October 2018, prior to patient enrolment, and the protocol was published 27 . A CONSORT checklist containing information reporting a randomized controlled trial has been included in Supplementary Note 1 . The trial protocol and statistical analysis plan are included in Supplementary Notes 2 and 3 .

Recruitment, inclusion and exclusion criteria

Children were recruited from 4 th May 2020 to 27 th April 2021, and the trial closed on 25 th May 2021 after the completion of the period of follow up of the last child. Potentially eligible children were identified by the study nursing teams, and written permission to screen was obtained from caregivers. A detailed information sheet in local languages was discussed with caregivers prior to seeking consent. Weight, length and mid-upper arm circumference (MUAC) were measured three times, and eligibility ascertained. Children of either sex were eligible for inclusion if aged 6-59 months and hospitalised with SAM (using WHO definitions: WLZ <−3, and/or MUAC <11.5cm, and/or bilateral pedal oedema), with written, informed consent from the primary caregiver. Children were excluded if unstable (shocked, hypothermic, hypoglycaemic, impaired consciousness), under 5kg body weight, had conditions impairing feeding, haemoglobin below 6 g/dl, or if their caregiver would not consent to child HIV testing or to remaining in hospital throughout the treatment course. Additional exclusion criteria were contraindications to any treatment or other factors that might prejudice study completion or analysis. No payments were made for participation, but transport refunds were made on discharge and on review to permit return home using public transport.

Trial procedures

Children were randomised equally to each of the four interventions, or standard care. Trial identification numbers were allocated sequentially in each site, with randomisation carried out by opening a sealed envelope bearing the corresponding number. The randomisation sequence was prepared by the trial statistician (KVB), stratified by study site, in random permuted blocks of variable size. Interventions began as soon as possible after baseline samples were collected. Children were managed by a team of nurses providing 24-hour cover, ensuring all treatments were administered and adverse events recorded. Study doctors (KC, GT) reported clinical progress daily using a standardised form. All treatment courses were 14 days. Samples for endpoint analysis were collected on day 15 (permissible window 15-19); children were then discharged if ready and reviewed on day 28 (window 28-42). Blood samples for safety monitoring (full blood count, renal and liver function, phosphate) were collected at baseline, 5 and 15 days post-randomisation. We enrolled children with predominantly oedematous SAM, and a high prevalence of HIV infection, and were not powered to evaluate effects in different subgroups of children. Tuberculosis was diagnosed clinically, and specifically searched for in any child with respiratory symptoms, using microscopy and culture of nasogastric aspirates whenever possible, chest X-ray and urine lipoarabinomannan according to clinical protocols.

Investigational products

Bovine colostrum (supplied by Colostrum UK) and N-acetyl glucosamine (Blackburn Distributions, UK) are nutraceuticals, regarded as safe and not licensed as medicines. They were provided as powder and encapsulated to ensure accurate dosing (colostrum 1.5 g 8-hourly throughout; N-acetyl glucosamine 300 mg 8-hourly days 1–7, 600 mg 8-hourly days 8–14). The dose of colostrum (4.5 g/day orally or via nasogastric tube) was chosen to be similar to those used in other published studies involving children. Ismail et al. treated premature infants with a dose of approx. 0.5–1 g colostrum/kg/day to examine gut immune priming 47 , and Barakat & Omar used 3 g/day of colostrum for children aged 6 months to 2 years suffering from acute diarrhoea 48 . The dose of N-acetyl glucosamine was based on our previous study in paediatric Crohn’s disease, where daily dosage of 6 grams augmented expression of epithelial glycosaminoglycans without evidence of adverse effects 33 . Intravenous doses of up to 100 mg have been tolerated in adults without adverse effects 33 and breastfed newborns consume 650–1500 mg of n-acetyl glucosamine per litre of human breast milk from well-nourished mothers 49 . Budesonide 0.5 mg and 1 mg respules (Alliance Healthcare, UK) are designed for nebuliser therapy but used off-licence orally for gastrointestinal therapy. These were opened on the ward and administered orally or by nasogastric tube. Dosage was 1 mg 8-hourly during days 1–7, 1 mg 12-hourly during days 8–11, and then 0.5 mg 12-hourly during days 12–14. The dosage was derived from studies in paediatric Crohn’s disease, where 9 mg enteric-coated daily budesonide proved equally efficacious to 40 mg prednisolone but with substantially reduced adverse effects 50 . Teduglutide (Revestive, Takeda) is licensed widely for intestinal failure but never previously evaluated in SAM. It was provided as 1.25 mg vials which were stored at 4–8 °C, and given by subcutaneous injection (0.05 mg/kg daily, based on weight measured on days 1 and 8). Prior stability testing carried out by Takeda confirmed that the opened vial is stable at 4–8 °C for 24 hours so each vial provided two doses, drawn 24 hours apart. Site rotation was marked on a map of anatomical sites as recommended by the manufacturer. The selected dose for teduglutide (0.05 mg/kg) was found to be the most effective dose in a phase 3, 12-week paediatric trial when compared to two lower doses of 0.025 mg/kg and 0.0125 mg/kg 51 . It is the dose currently approved by the FDA in the US and the EMA in Europe.

Evaluation of endpoints

The primary endpoint was the day 15 composite faecal inflammatory biomarker score, comprising myeloperoxidase, neopterin and α 1 -antitrypsin 27 . Secondary endpoints at day 15 were: changes in anthropometry; plasma biomarkers of enteropathy, microbial translocation and systemic inflammation (iFABP, LBP, CRP, sCD14, CD163, IGFBP-3, and GLP-2); days with diarrhoea, fever, and oedema; and adverse events. For children who were potty trained, stool was collected using a clean pot and then the required amount was transferred to a sterile stool container using a scoop. For those who are were not potty trained, diapers were used. The diapers were put inside out so that the plastic layer was next to the skin. A scoop was used to place a sample in a sterile stool container. The collected sample was then put in a cooler box with ice packs immediately. A sample transmittal form was used to keep track of the transit time from point of collection to receipt in the laboratory. Nursing staff stayed in communication with lab staff to ensure rapid delivery of samples to the laboratory.

Biomarkers were assayed by ELISA (Supplementary Table S5 ) by laboratory scientists (KZ, KM, EB) blinded to study arm, and re-calculated independently (by RN and JS) from raw data on harmonised Gen5 software (Biotek/Agilent, Santa Clara, CA). Serum albumin and lipopolysaccharide, though pre-specified as endpoints, were not included due to failing quality control checks leading to low concordance between sites. IGF-1 values were very close to zero; as insufficient plasma was available for re-testing these data have been omitted. Lactulose/rhamnose urinary excretion tests were only performed on children undergoing endoscopy and only 14 valid data pairs were obtained; these data are therefore not shown.

A subgroup of children in Lusaka additionally underwent endoscopy for duodenal biopsy between days 15 and 19; only the Lusaka site was selected for this due to its considerable experience in paediatric endoscopy over many years. Except for two periods when endoscopy instruments required repair, children were selected sequentially, provided there were no haematological or anaesthetic contraindications. Sedation was administered by an anaesthetist (HS or MZ) and biopsies were collected from the second part of the duodenum using a Pentax 2490i paediatric gastroscope. Biopsies were orientated under a dissecting microscope and fixed before processing into paraffin blocks, sectioning and staining. Slides were scanned at 20x magnification on an Olympus VS-120 scanning microscope and blinded morphometry was performed by a single observer (CM, confirmed by PK) on all villus and crypt units identifiable in well-orientated parts of sections of each biopsy. The criterion used for suitable orientation was that crypts should be visualised throughout their length (see Fig. 2 , and reference 22 ), and then the boundary between crypt and villus compartments delineated. Crypt depth was measured in micrometres (μm) from this boundary to the furthest point of the base of the crypt, where the basement membrane would be expected. Villus height was measured in μm from the boundary to the villus tip in a straight line. Epithelial surface area was measured as the perimeter of the villi where muscularis mucosae could be measured, and expressed per micrometre of muscularis mucosae. Any portions of these sections where crypts were not visualised along their entire length were deemed poorly orientated and not used for morphometry. The median number of villi measured was 6 (IQR 4-9; range 3-13).

Adverse events between enrolment and day 15 or day 28 were reported in real time and reviewed for seriousness, severity, relatedness and expectedness; all serious adverse events were reported to the Sponsor (Queen Mary University of London), ethics committees and national trial regulators. Severity was categorised as mild, moderate or severe using the DAIDS classification ( https://rsc.niaid.nih.gov/clinical-research-sites/daids-adverse-event-grading-tables ), and all AEs reported monthly to the Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC). Three Adverse Events of Special Interest (AESIs) were specifically sought: intestinal obstruction or volume overload for teduglutide, and osmotic diarrhoea for colostrum and N-acetyl glucosamine. Haematology and biochemistry results at baseline, days 5 and 15 were graded using DAIDS tables.

Sample size

The planned sample size was 225 children (45 in each arm), based on the composite biomarker score 27 . Enrolment was slowed by COVID-19, but trial losses were much lower than anticipated (3% observed versus 20% anticipated). The Trial Steering Committee and DMEC therefore reviewed the sample size in January 2021 once 82 children had been enrolled. The decision was made to reduce the sample size, based on a Cohen’s d effect size of 0.3, with 80% power and 90% confidence, and conservative correlation between baseline and follow-up estimates of 0.5, requiring 23 per group across 5 groups to analyse the primary outcome by ANCOVA. Allowing for 5% losses, the sample size of 115 was rounded up to 125 participants in total (25 per group).

Statistical analysis

Per protocol analyses were pre-specified 27 , and all hypothesis testing was 2-sided. Statistical analysis was performed in Stata 17 (Stata corp, College Station, Texas). Analysis of primary and secondary endpoints was based on comparison against standard care. ANCOVA was used to model final endpoint values, with adjustment for core baseline value, sex, baseline presence of oedema, HIV status, baseline diarrhoea, baseline WLZ score, and study site. Mortality was low (3 deaths) so could not be analysed statistically. Covariates chosen were pre-specified to take into account important elements of pathophysiology (worse outcome in HIV infection and oedematous malnutrition and in children with diarrhoea 52 ) and to allow for possible differences between the two countries. For some secondary endpoints negative binomial models were constructed which used a smaller set of adjustment variables (sex & HIV) due to model constraints (Table 2 ). Anthropometric measurements were calculated as change from baseline. The endoscopy subset was analysed separately, comparing post-treatment morphometric measurements by Kruskal-Wallis test, followed by Dunn’s test. Treatment effects were deemed statistically significant if the P value was <0.1 when compared to the control arm, as pre-specified. No adjustments of the false-positive (type I) error rate were planned, in line with the general consensus that adjustment for type I error rate is not required in exploratory multi-arm multi-stage trials in Phase II within the treatment development framework 27 , 53 .

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Data supporting the findings of this study are available in the article and in its Supplementary Information. Source data are provided as a Source Data file for Fig. 3 , and have also been deposited in Figshare under accession code https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.24442699 . The data uploaded to figshare include deidentified individual participant data, trial protocol, and statistical analysis plan.

Bhutta, Z. A. et al. Severe childhood malnutrition. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 3 , 17067 (2017).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Childhood Acute Illness and Nutrition (CHAIN) Network. Childhood mortality during and after acute illness in Africa and south Asia: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Glob. Health 10 , e673–e684 (2022).

Article Google Scholar

WHO Guideline: Updates on the management of severe acute malnutrition in infants and children. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013.

Lenters, L. M., Wazny, K., Webb, P., Ahmed, T. & Bhutta, Z. A. Treatment of severe and moderate acute malnutrition in low- and middle-income settings: a systematic review, meta-analysis and Delphi process. BMC Public Health 13 , S23 (2013).

Article PubMed Central PubMed Google Scholar

Trehan, I. et al. Antibiotics as part of the management of severe acute malnutrition. N. Engl. J. Med. 368 , 425–435 (2013).

Article CAS PubMed Central PubMed Google Scholar

Isanaka, S. et al. Routine Amoxicillin for uncomplicated severe acute malnutrition in children. N. Engl. J. Med. 374 , 444–453 (2016).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Tickell, K. D. & Denno, D. M. Inpatient management of children with severe acute malnutrition: a review of WHO guidelines. Bull. World Health Org. 94 , 642–651 (2016).

Nalwanga, D. et al. Mortality among children under five years admitted for routine care of severe acute malnutrition: a prospective cohort study from Kampala, Uganda. BMC Pediatr. 20 , 182 (2020).

Amadi, B. C. et al. Intestinal and systemic infection, HIV and mortality in Zambian children with persistent diarrhoea and malnutrition. J. Ped Gastroenterol. Nutr. 32 , 550–554 (2001).

CAS Google Scholar

Kerac, M. et al. Follow-up of post-discharge growth and mortality after treatment for severe acute malnutrition (FuSAM study): a prospective cohort study. PLoS One 9 , e96030 (2014).

Article ADS PubMed Central PubMed Google Scholar

Bwakura-Dangarembizi, M. et al. Risk factors for post-discharge mortality following hospitalization for severe acute malnutrition in Zimbabwe and Zambia. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 113 , 665–674 (2021).

Girma, T. et al. Nutrition status and morbidity of Ethiopian children after recovery from severe acute malnutrition: Prospective matched cohort study. PLoS One 17 , e0264719 (2022).

Njunge, J. M. et al. Biomarkers of post-discharge mortality among children with complicated severe acute malnutrition. Sci. Rep. 9 , 5981 (2019).

Bhutta, Z. A., Guerrant, R. L. & Nelson, C. A. 3rd Neurodevelopment, nutrition, and inflammation: the evolving global child health landscape. Pediatrics 139 , S12–S22 (2017).

Kar, B. R., Rao, S. L. & Chandramouli, B. A. Cognitive development in children with chronic protein energy malnutrition. Behav. Brain Funct. 4 , 31 (2008).

Galler, J. R. et al. Neurodevelopmental effects of childhood malnutrition: A neuroimaging perspective. NeuroImage 231 , 117828 (2021).

Prendergast, A. S. J. & Kelly, P. Interactions between intestinal pathogens, enteropathy and malnutrition in developing countries. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 29 , 229–236 (2016).

Brunser, O., Castillo, C. & Araya, M. Fine structure of the small intestinal mucosa in infantile marasmic malnutrition. Gastroenterology 70 , 495–507 (1976).

Shiner, M., Redmond, A. O. & Hansen, J. D. The jejunal mucosa in protein-energy malnutrition. A clinical, histological, and ultrastructural study. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 19 , 61–78 (1973).

Attia, S. et al. Mortality in children with complicated severe acute malnutrition is related to intestinal and systemic inflammation: an observational cohort study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 104 , 1441–1449 (2016).

Amadi, B. et al. Impaired barrier function and autoantibody generation in malnutrition enteropathy in Zambia. EBiomedicine 22 , 191–199 (2017).

Mulenga, C. et al. Epithelial abnormalities in the small intestine of Zambian children with stunting. Front Med (Gastroenterol.) 9 , 849677 (2022).

Liu, T.-C. et al. A novel histological index for evaluation of environmental enteric dysfunction identifies geographic-specific features of enteropathy among children with suboptimal growth. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 14 , e0007975 (2020).

Campbell, D. I., Murch, S. H. & Elia, M. Chronic T cell-mediated enteropathy in rural West African children: relationship with nutritional status and small bowel function. Pediatr. Res. 54 , 306–311 (2003).

Brenchley, J. M. & Douek, D. C. Microbial translocation across the GI tract. Annu Rev. Immunol. 30 , 149–173 (2012).

Chama, M. et al. Transcriptomic analysis of enteropathy in Zambian children with severe acute malnutrition. EBioMedicine 45 , 456–463 (2019).

Kelly, P. et al. TAME trial: a multi-arm phase 2 randomised trial of four novel interventions for malnutrition enteropathy in Zambia and Zimbabwe; a study protocol. BMJ Open 9 , e027548 (2019).

Playford, R. J. & Weiser, M. J. Bovine Colostrum: Its constituents and uses. Nutrients 13 , 265 (2021).

Chandwe, K. & Kelly, P. Colostrum therapy for human gastrointestinal health and disease. Nutrients 13 , 1956 (2021).

Khan, Z. et al. Use of the ‘nutriceutical’, bovine colostrum, for the treatment of distal colitis: results from an initial study. Aliment Pharm. Ther. 16 , 1917–1922 (2002).

Article CAS Google Scholar

Amadi, B. et al. Reduced production of sulfated glycosaminoglycans occurs in Zambian children with kwashiorkor but not marasmus. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 89 , 592–600 (2009).

Bode, L. et al. Heparan sulfate and syndecan-1 are essential in maintaining murine and human intestinal epithelial barrier function. J. Clin. Invest 118 , 229–238 (2008).

Salvatore, S. et al. A pilot study of N-acetyl glucosamine, a nutritional substrate for glycosaminoglycan synthesis, in paediatric chronic inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharm. Ther. 14 , 1567–1579 (2000).

Kocoshis, S. A. et al. Safety and efficacy of Teduglutide in pediatric patients with intestinal failure due to short Bowel Syndrome: A 24-week, Phase III Study. JPEN J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 44 , 621–631 (2020).

Hill, S. et al. Safety findings in pediatric patients during long-term treatment with teduglutide for short-bowel syndrome-associated intestinal failure: pooled analysis of 4 clinical studies. JPEN J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 45 , 1456–1465 (2021).

Rezaie, A. et al. Budesonide for induction of remission in Crohn’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015 , CD000296 (2015).

PubMed Central PubMed Google Scholar

Owino, V. et al. Environmental Enteric dysfunction and growth failure/stunting in global child health. Pediatrics 138 , e20160641 (2016).

Trehan, I., Kelly, P., Shaikh, N. & Manary, M. J. New insights into environmental enteric dysfunction. Arch. Dis. Child 101 , 741–744 (2016).

Picot, J. et al. The effectiveness of interventions to treat severe acute malnutrition in young children: a systematic review. Health Tech. Assess. 16 , 19 (2012).

Article MathSciNet Google Scholar

Wen, B. et al. Systemic inflammation and metabolic disturbances underlie inpatient mortality among ill children with severe malnutrition. Sci. Adv. 8 , eabj6779 (2022).

Article ADS CAS PubMed Central PubMed Google Scholar

Sicard, J. F. et al. N-acetyl-glucosamine influences the biofilm formation of Escherichia coli . Gut Pathog. 10 , 26 (2018).

Paris, M. C. et al. Plasma GLP-2 levels and intestinal markers in the juvenile pig during intestinal adaptation: effects of different diet regimens. Dig. Dis. Sci. 49 , 1688–1695 (2004).

Jones, K. D. et al. Mesalazine in the initial management of severely acutely malnourished children with environmental enteric dysfunction: a pilot randomized controlled trial. BMC Med 12 , 133 (2014).

Wang, J. et al. Respiratory influenza virus infection induces intestinal immune injury via microbiota-mediated Th17 cell-dependent inflammation. J. Exp. Med. 211 , 2397–2410 (2014). Erratum in: J Exp Med. 2014 Dec 15;211(13):2683. Erratum in: J Exp Med 2014;211(12):2396-7.

Sturgeon, J. P., Bourke, C. D. & Prendergast, A. J. Children with noncritical infections have increased intestinal permeability, endotoxemia and altered innate immune responses. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 38 , 741–748 (2019).

Kelly, P. et al. Gene expression profiles compared in environmental and malnutrition enteropathy in Zambian children and adults. EBioMedicine 70 , 103509 (2021).

Ismail, R. I. H. et al. Gut priming with bovine colostrum and T regulatory cells in preterm neonates: a randomized controlled trial. Pediatr. Res. 90 , 650–656 (2021).

Barakat, S. H., Meheissen, M. A., Omar, O. M. & Elbana, D. A. Bovine colostrum in the treatment of acute diarrhea in children: a double-blinded randomized controlled trial. J. Trop. Pediatr. 66 , 46–55 (2020).

PubMed Google Scholar

Miller, J. B., Bull, S., Miller, J. & McVeagh, P. The oligosaccharide composition of human milk: temporal and individual variations in monosaccharide components. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 19 , 371–376 (1994).

Levine, A. et al. A comparison of budesonide and prednisone for the treatment of active pediatric Crohn disease. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 36 , 248–252 (2003).

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Carter, A. et al. Outcomes from a 12-week, open-label, multicenter clinical trial of teduglutide in pediatric short bowel syndrome. J. Pediatr. 181 , 102–111 (2017).

Karunaratne, R., Sturgeon, J. P., Patel, R. & Prendergast, A. J. Predictors of inpatient mortality among children hospitalized for severe acute malnutrition: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 112 , 1069–1079 (2020).

Wason, J. M., Stecher, L. & Mander, A. P. Correcting for multiple-testing in multi-arm trials: is it necessary and is it done? Trials 15 , 364 (2014).

Download references

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the following nurses from the wards and endoscopy unit of UTH: Evelyn Nyendwa, Esther Chilala, Andreck Tembo, Lucy Macwani, Dalitso Tembo, Mary Phiri, Elaine Brittel Sikuyuba, Sophreen Mwaba, Gwendolyn Nayame, Joyce Sibwani, Rose Soko, Kashinga Maseko, and Mulima Mwiinga. We are grateful to the nursing team in Harare Central Hospital: Sarudzai Murumbi, Tariro Zure, and Lucia Manyatera. We also sincerely thank Mr Rizvan Batha of Barts Health Pharmacy for assistance with procurement of investigational products. We are very grateful to the Trial Steering committee (Professors Jay Berkley, Ian Sanderson, and James Wason) and Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (Professor Jim Todd, Doctors Rose Kambarami, Veronica Mulenga, and Philip Ayieko). The TAME trial was sponsored by Queen Mary University of London, but the Sponsor played no role in study design, data collection, analysis, or manuscript writing. The trial was funded by a grant from the Medical Research Council (UK), number MR/P024033/1. AJP and JPS are funded by Wellcome (108065/Z/15/Z for AJP, and 220566/Z/20/Z for JPS). Takeda UK provided teduglutide at a discounted price.

The Medical Research Council (UK) funded the study. Takeda UK provided tedu-glutide at a discounted price.

Author information

These authors contributed equally: Kanta Chandwe, Mutsa Bwakura-Dangarembizi.

Authors and Affiliations

Tropical Gastroenterology & Nutrition group, University of Zambia School of Medicine, Nationalist Road, Lusaka, Zambia

Kanta Chandwe, Beatrice Amadi, Deophine Ngosa, Nivea Chulu, Kanekwa Zyambo, Chola Mulenga, Ellen Besa, Bwalya Simunyola, Lydia Kazhila, Miyoba Chipunza, Victor Mudenda, Kelley VanBuskirk & Paul Kelly

Zvitambo Institute for Maternal and Child Health Research, McLaughlin Avenue, Meyrick Park, Harare, Zimbabwe

Mutsa Bwakura-Dangarembizi, Gertrude Tawodzera, Anesu Dzikiti, Robert Makuyana, Kuda Mutasa, Jonathan P. Sturgeon, Shepherd Mudzingwa, Batsirai Mutasa, Virginia Sauramba, Lisa Langhaug & Andrew J. Prendergast

Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, University of Zimbabwe, Parirenyatwa Hospital, Harare, Zimbabwe

Mutsa Bwakura-Dangarembizi

Blizard Institute, Queen Mary University of London, Newark Street, London, UK

Jonathan P. Sturgeon, Andrew J. Prendergast & Paul Kelly

Department of Anaesthesia, University of Zambia School of Medicine, Nationalist Road, Lusaka, Zambia

Masuzyo Zyambo & Hazel Sonkwe

Warwick University Medical School, Coventry, UK

Simon H. Murch

Great Ormond Street Hospital, London, UK

University of West London, Ealing, London, UK

Raymond J. Playford

University College Cork, College Road, Cork, Ireland

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

KC, MBD, BA, SHM, RJP, SH, AJP and PK initiated and designed the trial. KC, GT, DN, AD, NC, RM, LK, BM and LL designed the trial instruments and data collection procedures. KC, MBD, BA, GT, DN, AD, NC, and RM carried out the daily clinical care and data collection. KZ, KM, CM, EB and VM were responsible for laboratory operating procedures, data acquisition and processing. LK, BM and LL undertook data entry and cleaning. MC, VS and LL undertook monitoring and quality control of the trial. BS and SM designed and implemented the pharmacy and pharmacovigilance procedures. MZ and HS undertook anaesthetic procedures and ensured the safety of children undergoing endoscopy. Analysis was carried out by KVB, JPS, LL, AJP and PK; AJP and PK wrote the initial draft which was revised by all authors.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Paul Kelly .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

RJP was previously an external consultant to Colostrum UK which provided the bovine colostrum used in these studies. RJP has also been an external consultant to Sterling Technology (USA) and an employee of Pantheryx Inc (USA) who produce and distribute bovine colostrum. There was no bovine colostrum company involvement in the production of this article or editing of its content. SH has had funding for teduglutide studies and lectured and participated in advisory boards on behalf of Takeda. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information.

Nature Communications thanks Indi Trehan and the other anonymous, reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information, peer review file, reporting summary, source data, source data, rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Chandwe, K., Bwakura-Dangarembizi, M., Amadi, B. et al. Malnutrition enteropathy in Zambian and Zimbabwean children with severe acute malnutrition: A multi-arm randomized phase II trial. Nat Commun 15 , 2910 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-45528-0

Download citation

Received : 28 April 2023

Accepted : 26 January 2024

Published : 17 April 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-45528-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines . If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Modelling chronic malnutrition in Zambia: A Bayesian distributional regression approach

Contributed equally to this work with: Given Moonga, Johannes Seiler

Roles Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliations Center for International Health, Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich, Munich, Germany, Department of Public Health, Health Services Research and Health Technology Assessment, UMIT—University for Health Sciences, Medical Informatics and Technology, Hall in Tirol, Austria, Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, University of Zambia, Lusaka, Zambia

Roles Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing

¶ ‡ These authors also contributed equally to this work.

Affiliations Department of Public Health, Health Services Research and Health Technology Assessment, UMIT—University for Health Sciences, Medical Informatics and Technology, Hall in Tirol, Austria, Institute and Outpatient Clinic for Occupational, Social and Environmental Medicine, Clinical Centre of the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich, Munich, Germany

Roles Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Institute for medical Information Processing, Biometry, and Epidemiology, Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich, Munich, Germany

Roles Data curation, Supervision, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Department of Humanities, Social and Political Sciences, ETH Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland

Roles Supervision

Affiliation Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, University of Zambia, Lusaka, Zambia

Roles Supervision, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Institute and Outpatient Clinic for Occupational, Social and Environmental Medicine, Clinical Centre of the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich, Munich, Germany

Affiliation Department of Public Health, Health Services Research and Health Technology Assessment, UMIT—University for Health Sciences, Medical Informatics and Technology, Hall in Tirol, Austria

Affiliation School of Veterinary Medicine, University of Zambia, Lusaka, Zambia

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliations Department of Public Health, Health Services Research and Health Technology Assessment, UMIT—University for Health Sciences, Medical Informatics and Technology, Hall in Tirol, Austria, Department of Statistics, University of Innsbruck, Innsbruck, Austria

- Given Moonga,

- Stephan Böse-O’Reilly,

- Ursula Berger,

- Kenneth Harttgen,

- Charles Michelo,

- Dennis Nowak,

- Uwe Siebert,

- John Yabe,

- Johannes Seiler

- Published: August 4, 2021

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0255073

- Reader Comments

The burden of child under-nutrition still remains a global challenge, with greater severity being faced by low- and middle-income countries, despite the strategies in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Globally, malnutrition is the one of the most important risk factors associated with illness and death, affecting hundreds of millions of pregnant women and young children. Sub-Saharan Africa is one of the regions in the world struggling with the burden of chronic malnutrition. The 2018 Zambia Demographic and Health Survey (ZDHS) report estimated that 35% of the children under five years of age are stunted. The objective of this study was to analyse the distribution, and associated factors of stunting in Zambia.

We analysed the relationships between socio-economic, and remote sensed characteristics and anthropometric outcomes in under five children, using Bayesian distributional regression. Georeferenced data was available for 25,852 children from two waves of the ZDHS, 31% observation were from the 2007 and 69% were from the 2013/14. We assessed the linear, non-linear and spatial effects of covariates on the height-for-age z-score.

Stunting decreased between 2007 and 2013/14 from a mean z-score of 1.59 (credible interval (CI): -1.63; -1.55) to -1.47 (CI: -1.49; -1.44). We found a strong non-linear relationship for the education of the mother and the wealth of the household on the height-for-age z-score. Moreover, increasing levels of maternal education above the eighth grade were associated with a reduced variation of stunting. Our study finds that remote sensed covariates alone explain little of the variation of the height-for-age z-score, which highlights the importance to collect socio-economic characteristics, and to control for socio-economic characteristics of the individual and the household.

Conclusions

While stunting still remains unacceptably high in Zambia with remarkable regional inequalities, the decline is lagging behind goal two of the SDGs. This emphasises the need for policies that help to reduce the share of chronic malnourished children within Zambia.

Citation: Moonga G, Böse-O’Reilly S, Berger U, Harttgen K, Michelo C, Nowak D, et al. (2021) Modelling chronic malnutrition in Zambia: A Bayesian distributional regression approach. PLoS ONE 16(8): e0255073. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0255073

Editor: Tzai-Hung Wen, National Taiwan University, TAIWAN

Received: February 23, 2020; Accepted: July 10, 2021; Published: August 4, 2021

Copyright: © 2021 Moonga et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: Data are third party data available from the following sites: https://crudata.uea.ac.uk/cru/data/drought/ https://malariaatlas.org/ https://ngdc.noaa.gov/eog/dmsp/downloadV4composites.html https://sedac.ciesin.columbia.edu/data/set/gpw-v4-population-density-rev11/data-download https://dhsprogram.com/data/ .

Funding: Johannes Seiler acknowledges financial support from the University of Innsbruck through a postdoctoral scholarship. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: No authers have competing interests.

Introduction

The burden of child malnutrition still remains a global challenge, with greater severity being faced by low-and middle-income countries [ 1 – 3 ]. Globally, malnutrition is amongst the most important risk factors associated with illness and death, affecting hundreds of millions of pregnant women and young children [ 3 – 6 ]. Stunting in early childhood is strongly associated with numerous short-term and long-term consequences, including increased childhood morbidity and mortality, delayed growth and motor development and long-term educational and economic consequences later in life [ 7 ]. Undernourishment causes children to start life at mentally suboptimal levels [ 8 ].

Assessment of childhood malnutrition commonly relies on standard anthropometric measures for insufficient height-for-age (stunting) indicating chronic undernutrition, insufficient weight-for-height (wasting), indicating acute undernutrition; and insufficient weight-for-age (underweight), an indicator commonly used to asses, both, chronic, and acute undernutrition [ 9 , 10 ].

Anthropometric measurements are practical techniques for assessing children’s growth patterns during the first years of life. The measurements also provide useful insights into the nutrition and health situation of entire population groups. Anthropometric indicators are less accurate than clinical and biochemical techniques in assessing individual nutritional status. However in resources limited settings, the measurements are a useful screening tool to identify individuals at risk of undernutrition, who can later be referred to subsequent possible confirmatory investigation [ 11 ].

It is estimated that globally 52 million children under-five years of age are wasted, 17 million are severely wasted and 155 million are stunted. Around 45% of deaths among children under-five years of age, most of which occur in the sub-Saharan Africa are linked to undernutrition [ 3 , 9 ]. It is also estimated that four out of ten children under the age of five in Zambia are stunted [ 12 ]. This paper will therefore focus on childhood stunting in Zambia.

Global prevalence of stunting in children younger than five years declined during the past two decades, but still remain unacceptably high in South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa regions [ 5 ]. If current trends remain unchecked, projections indicate that 127 million children under five years of age will be stunted in 2025 [ 1 ]. There is therefore need to heighten various interventions in these affected region and to investigate possible area specific determinants of stunting.

There are already fairly well documented perspectives on determinants of malnutrition. The treatise on these determinants mainly relies on the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) conceptual framework on malnutrition which has evolved over time as more knowledge and evidence on the causes, consequences and impacts of undernutrition is generated. The framework distinguishes between immediate, intermediate and underlying determinants of malnutrition [ 5 , 13 – 15 ].

The immediate causes of undernutrition include inadequate dietary intake and disease, while the underlying causes could include household food insecurity, inadequate care and feeding practices for children, unhealthy household and surrounding environments, and inaccessible and often inadequate health care. Basic causes of poor nutrition encompasses the societal structures and processes that neglect human rights and perpetuate poverty, constraints faced by populations to essential resources [ 13 ].

Several studies done within sub-Saharan Africa investigated determinants such as the mother’s level of education, income levels and these factors have been linked to malnutrition [ 9 , 12 , 16 , 17 ]. The source of the drinking water, the wealth of the household, the area of residence, age of the child, the sex of the child, the breastfeeding duration, the age of the mother has also been investigated and were observed to be significant correlates of stunting [ 12 , 18 ]. Within Zambia, stunting was observed to be more likely among children of less educated mothers (45%) and those from the poorest households (47%) [ 19 ]. The determinates of malnutrition are related to each other and the differences and direction between these levels of determinism as indicated in the UNICEF framework are often not discrete but in reality related. As discussed by Kandala [ 17 ] for example, the mother’s level of education might be influencing child care practises- an intermediate determinant—and the resources available to the household—an underlying determinant.

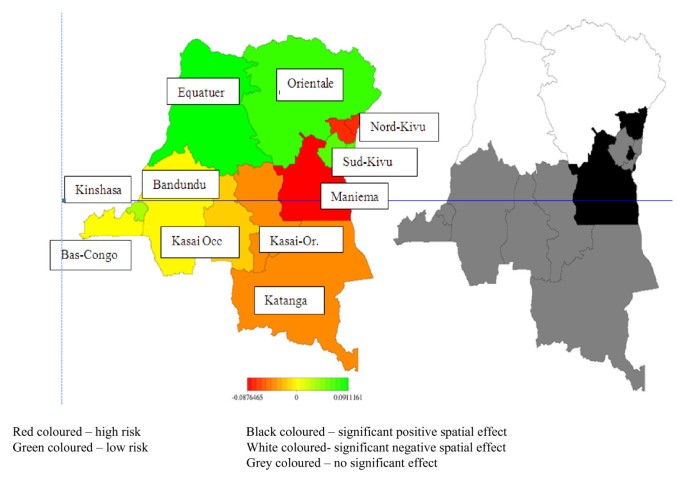

Previous studies elsewhere have observed that stunting tends to show regional variation [ 4 , 9 , 16 ]. We see this trend in Zambia as well, where the decline of stunting has been only gradual and unacceptable, with higher prevalence in Northern province where 50% of the children being stunted, and stunting being less common in Lusaka, Copperbelt, and Western provinces where 36% of children are stunted [ 19 ]. We see this regional variation of stunting in Fig 1 which shows stunting in Zambia in the 2007 and 2013/14 waves of the Zambian Demographic and Health Surveys (ZDHS). The ZDHS is a national-wide survey which is representative at a sub-national level and contains information on trends in fertility, childhood mortality, use of family planning methods, and maternal and child health indicators including HIV and AIDS [ 19 ]. The figure shows the height-for-age z-score, with Western province better than Northern province for the 2007 wave. We see a slight difference in 2013/14 as stunting seemed to get worse in parts of the Western province.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

The panel shows the average height-for-age z-score at district level for 2007 (left) and 2013/14 (right) of Zambia. Source : Demographic and Health Surveys (data) and Database of Global Administrative Areas (boundary information); calculation by authors. The shapefile used to create these maps is republished from [ 54 ] under CC BY license, with permission from Robert J. Hijmans, original copyright [2021].

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0255073.g001

Much of the work done on the determinants of stunting in Zambia, have considered socio-economic characteristics and have assessed the linear effects of these determinants on the conditional mean [ 12 , 20 ], using models specifications such as; linear models, generalized linear models (GLMs) and generalized additive models (GAMs) [ 21 ]. These aproaches are useful and have the advantage of being easy to estimate and to interpret. However, they may risk model misspecification and draw inaccurate estimates, when heterogeneity is present, or when extreme values in the response are present and when a linear relationship is not plausible. In the analysis of certain outcomes, like stunting for example, the interest is not only in the conditional mean, but also in extreme values (height-for-age z-scores), or other parameters of the response. Quantile regression is one possibility to model beyond the conditional mean, with the interest to show variation of the outcome at a quantile level, without making any assumptions of the response distribution. This method for example has been applied in child malnutrition studies [ 16 ]. However, distributional regression offers advantage over quantile regression, as it provides the possibility to characterize the complete probabilistic distribution of the response in one joint model [ 21 , 22 ]. Moreover, distributional regression is more efficient, if prior knowledge on specific aspects of the response distribution is available, or can be estimated [ 23 ]. Furthermore, the characterization of the whole distribution of the response is more informative.

The study by Kandala [ 24 ] which focused on stunting in sub-Saharan countries found that there are distinct spatial patterns of malnutrition that are not explained by the socio-economic determinants or other well-known correlates alone [ 16 , 25 ]. As such, our study includes spatial covariates, since we aim at investigating spatial differences of stunting in Zambia at sub-district level while jointly analysing socio-economic and environmental characteristics.

The following three reasons make our study novel compared to previous work [ 18 ]. Firstly, we jointly analysed remote sensed data and socio-economic covariates at sub-national level. This is made possible due to availability of georeferenced data at the primary sampling unit a household pertains to in the recent two ZDHS datasets. The Demographic and Health Surveys rely in most cases on a two-stage survey, and the primary sampling units corresponds to the enumeration areas from the most recent completed census that has been selected. Georeferenced data is important as it generates more specific information which can facilitate targeted interventions. Secondly, we used Bayesian distributional regression which allows us to model all parameters of the underlying response distribution. Lastly, we used two waves of the demographic health surveys to control for spatio temporal interactions. Therefore, this study demonstrates small area variation in stunting in Zambia and analyse possible inequalities and deprivation at the sub-district level.

Data sources

Socio-economic and georeferenced covariates.

We used data from the 2007 and 2013/14 ZDHS. The ZDHS is a national-wide survey which is representative at a sub-national level and contains information on trends in fertility, childhood mortality, use of family planning methods, and maternal and child health indicators including HIV and AIDS. For these population health indicators, data is collected for women aged 15–49, men aged 15–59 and children below five years of age [ 19 ].

The ZDHS provide besides information on the district a household pertains to, also information about the geolocation of the primary sampling unit a household belongs to, and from which the data was collected. The location of the primary sampling unit is the spatial information used in the empirical analysis. During data processing, GPS coordinates are displaced to ensure that respondent confidentiality is maintained. The displacement is randomly applied so that rural points contain a minimum of 0 and a maximum of 5 km of positional error. Urban points contain a minimum of 0 and a maximum of 2 km of error. A further 1% of the rural sample points are offset a minimum of 0 and a maximum of 10 km [ 26 ].

Demographic Health Surveys have documented weakness for estimation of individual anthropometric measurements. Potential threats to high data quality may occur across various research stages, from survey design to data analysis. There is also often a substantial amount of missing or implausible anthropometric data across surveys [ 27 ].

Furthermore, there is caution over the use of stunting as an individual classifier in epidemiologic research or its interpretation as a clinically meaningful health outcome. Stunting should be used as originally designed to be from its original use as a population level indicator of community well-being [ 28 ], as it reflects past health and nutrition conditions; and an indication of socio-economic development of a country [ 1 ].

Despite the above highlighted limitations of DHS and anthropometric indicators, they remain useful national wide measurements that can be used to estimate child health. Moreover, in general anthropometric measures are a good indicator for planning as they can provide a lot of information to policy makers to answer, how, where and which type of intervention would be favourable in specific settings.

Socio-economic and spatial determinants

The effects of socio-economic factors, such as the education of the mother, household size, wealth of the household on the health status of children are well documented [ 12 , 29 ]. We calculated an index representing the wealth of the household based on the household’s assets using Principal Components Analysis (PCA) following Filmer and Pritchett, and Sahn [ 30 , 31 ]. Previous studies have shown that household wealth status was a predictor of childhood malnutrition. Children from poor households are more likely to be stunted than those from richer households [ 29 ].

In our analysis we investigated the impact of different socio-economic factors, which impact on height-for age Z-score has been discussed in literature. Table 1 gives an overview and the according references.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0255073.t001

Remote sensed covariates

We obtained remote sensed data on drought severity, malaria incidence, and population density. The description, and source to these data sets is provided in Table 2 .

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0255073.t002

For example, the malaria incidence data was obtained from the Malaria Atlas Project (MAP). The project collects malaria data on malaria cases reported by surveillance systems, nationally representative cross-sectional surveys of parasite rate, and satellite imagery capturing global environmental conditions that influence malaria transmission [ 35 ].

Methodology

We assessed the relationships between socio-economic and remote sensed characteristics and anthropometric outcomes using the Bayesian Distributional Regression (BDR). BDR models all parameters of the response distribution based on structured additive predictors and allows to incorporate for example, non-linear effects of metric covariates, spatial effects, or varying effects. Applications of structured additive regression models to topics in Global Public Health are found in several publications [ 39 – 42 ]. This approach permits us to fully analyse the whole distribution [ 41 , 43 ] and our analysis was not restricted to assessing the conditional mean of the height-for-age z-score. Instead suspected heterogeneity across socio-economic and georeferenced factors and the anthropometric measure can be directly captured. In the context of growth failures this is of particular importance, as previous studies highlighted high levels of heterogeneity related to growth failures [ 33 ].

Bayesian distributional regression

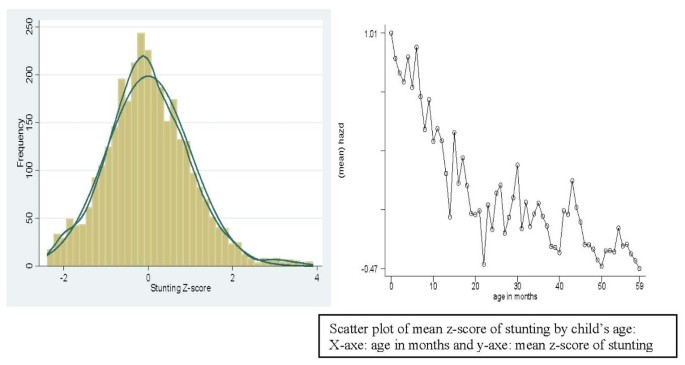

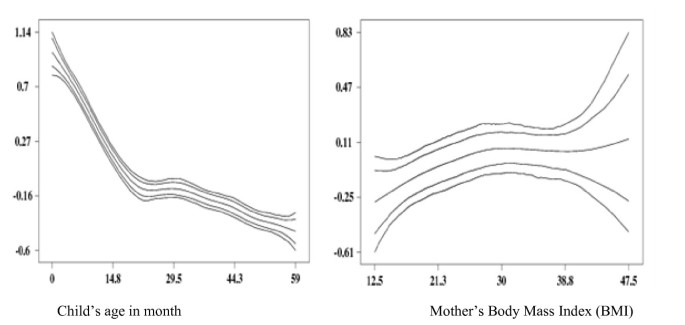

Relying on Bayesian distributional regression requires to specify the distribution of the response variable. Assuming the response distribution to be Gaussian permits to model besides the conditional mean also the variance or standard deviation of the response variable. Graphical analysis using amongst others randomised quantile residuals [ 44 ] strengthens that a Gaussian model is plausible. See also Fig 2 , for more details. In the left- hand panel of Fig 2 the histogram of the height-for-age z-score together with the underlying density illustrates why the normal distribution seems to be an appropriate choice. This is further confirmed in the second and third panel, where the histogram of the quantile residuals including the underlying kernel density estimate, respectively, the QQ-plot of the randomised quantile residuals are shown.

The left-hand panel shows the histogram and kernel density estimates of the height-for-age z-score, the middle panel shows the histogram of the randomised quantile residuals together with the normal density estimates, and the right-hand panels depicts the QQ-plot of the randomised quantile residuals. Source : Demographic and Health Surveys (data); calculation by authors.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0255073.g002

Model selection

The fit of the models are compared by relying on the Deviance Information Criterion (DIC) [ 50 ] and Widely Applicable Information Criterion (WAIC) [ 51 ], and are summarised in Table 3 . As a rule of thumb can be seen that the model with the lowest value describes the data best. We specified six distinct models, aiming to identify the importance of, for instance, socio-economic or georeferenced factors. In more detail, the differences between these models are summarised in Table 4 .

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0255073.t003

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0255073.t004

In the following Section we will discuss the results of Model 5, omitting insignificant terms, as Model 5 has both the lowest DIC and WAIC. Result of the included covariates are however, similar throughout all specifications.

Descriptive analysis

Table 5 shows the baseline characteristics of selected covariates in the population between the two ZDHS survey of 2007 and 2013/14, and remote sensed data aggregates for these waves.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0255073.t005

Data was available for 25,852 children from the two waves, 31% observation were from the 2007 and 69% were from the 2013/14 ZDHS. Levels of stunting decreased between 2007 and 13/14 from a mean z-scores of -1.59 CI(-1.63; -1.55) to -1.47 CI(-1.49; -1.44). The breastfeeding duration declined from 16.22 to 15.69. There was a notable increase in the number of received vaccinations by children from 5.6 to 7.5 vaccinations. There was a slight increase in the number of years the mother spent in school from 7.2 to 7.8. Malaria incidence rates (plasmodium falciparum incidence) declined from 26% to 20%. Night-time light increased from 2.75, to 3.72 (observed values were log transformed), a possible indication of increase in urbanisation. Night-time light was highly correlated ( ρ = 0.73) to population density as such it was omitted in subsequent analysis.