An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Am J Public Health

- v.110(10); Oct 2020

Hurricane Katrina at 15: Introduction to the Special Section

All authors contributed equally to this editorial.

Hurricane Katrina was a social and public health disaster. 1 From the perspectives of health care systems, the environment, community health, and everything in between, Katrina devastated New Orleans, Louisiana, and the Gulf Coast. In the 15 years since the storm, we have learned much about how devastating natural disasters can be for a community and how many ways public health can be involved in creating opportunities for recovery and preparing for the next disaster. Some of the lessons that we learned and that we need to learn are touched on in this special section.

Hurricane Katrina devastated the public health and health care systems across the US Gulf Coast and exposed the health and racial inequities that have persisted among this community for decades. As Kim-Farley notes (p. 1448), we are reaping what we sow. Individuals and families were affected emotionally, physically, and spiritually because of this disaster. Hurricane Katrina exacerbated the community’s health problems and exposed the fragmentation in care. Despite this, individuals in the community came together to mobilize and organize and to identify solutions to transform how health care was delivered to the community while ensuring health and racial equity. Over time, social norms evolved—shifting from residents accessing care in emergency departments to residents going to community-based health care provider organizations that offered comprehensive and holistic health and wellness services, including mental health and substance abuse disorder treatment.

HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE SYSTEMS

Three contributions to this special section discuss the impact of Hurricane Katrina on individuals’ health and on health care systems. “Hurricane Katrina beat us. We lost the ability to communicate, transport by land and air, and provide health care for the population,” writes Honoré (p. 1463). In this piece, Honoré highlights the inequities that were exposed and lessons from his experience as the commander of Joint Task Force—Katrina. Honoré provides a timely invitation to readers to confront injustices and improve preparedness and response to natural disasters amid COVID-19.

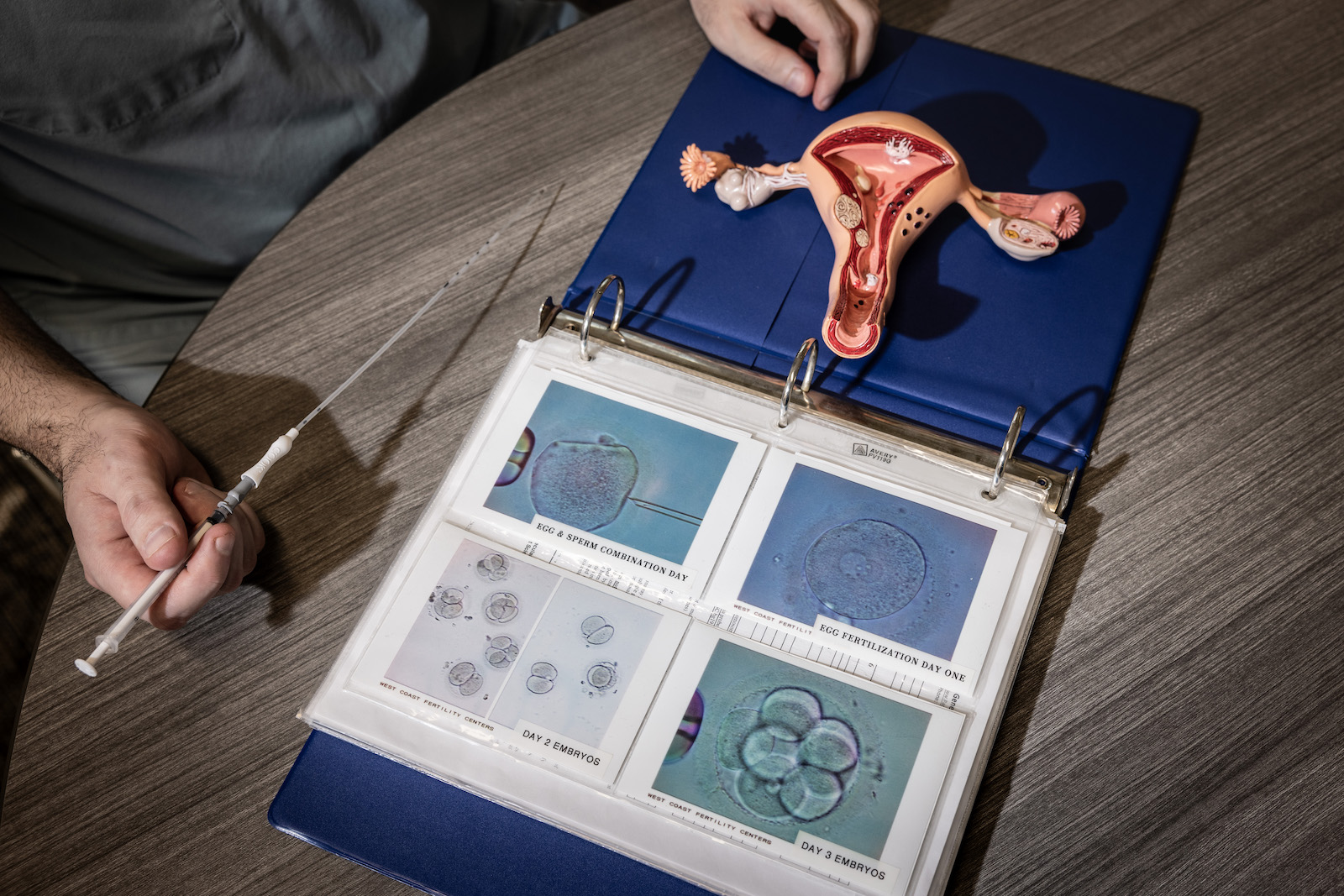

Harville et al. (p. 1466) explore the trends in pregnancy outcomes in women residing in the US Gulf States after Hurricane Katrina and consider whether women had an increase in adverse pregnancy outcomes because of the disaster. Katrina put a spotlight on the need for a major transformation of public health and health care system infrastructure to support the holistic needs of individuals.

Davis et al. (p. 1472) discuss the $100 million federal Primary Care Access and Stabilization Grant program, which paved the way for innovative and sustained public health and health care transformation across Greater New Orleans. This infrastructure offered community residents easily accessible, higher quality holistic care and acted as a catalyst for sustained funding for community-based health care organizations.

ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH

Four contributions to this special section address the environmental health issues raised and affected by Katrina. Hurricane Katrina was a natural event that had disastrous results because of the storm itself and the infrastructure and human failings that led to widespread flooding and power outages. Some of the failings were owing to being unprepared for a natural event of this magnitude. Wilson et al. (p. 1476) argue that we are still unprepared and that there remains work to be done to integrate environmental and public health expertise into a preparedness system. The 2019 Pandemic and All-Hazards Preparedness and Advancing Innovation Act is a recent policy-level action to raise environmental health preparedness. Of course, the outcome of this act will depend on our ability to implement its provisions and address any challenges.

Even when we are prepared for environmental events, the responses are not always quick enough to address the most serious concerns or to understand the full nature of the events. Lichtveld and Birnbaum (p. 1478) comment that we often focus our attention and resources on the immediate response phase and devote insufficient attention to any prolonged recovery. The longer-term problems brought on by Katrina made the environmental health community aware of and responsive to assessment and recovery after the Deepwater Horizon disaster (2010). Having the National Institutes of Health’s Disaster Research Response Program in place may facilitate immediate and longer term responses to future disasters.

Many authors have examined Katrina’s major environmental effects on New Orleans and their endurance. Diaz et al. (p. 1480) review this extensive literature and provide a summary of work related to floods, wastes, land losses, and other environmental consequences of Katrina. The numbers are staggering: 400 billion gallons of floodwaters, 120 million cubic yards of storm debris, and six times the usual annual land loss. Katrina led to the design and construction of the Hurricane Storm Damage Risk Reduction System, which we hope will help to protect New Orleans, at least in the near term.

In addition to the loss of homes and land, Katrina compromised the interiors of thousands of homes. Lichtveld et al. (p. 1485) comment on the mold infestation of homes and the resulting exacerbations of childhood asthma. Community-based participatory research addresses environmental asthma in a manner that can serve as a model for other communities. This model is particularly relevant today, as we come to grips with the full understanding of environmental health threats, disasters, and health disparities.

PUBLIC HEALTH RESPONSE

Hurricane Katrina, coined “the worst natural disaster of the century,” exposed the essential need for a multifaceted cross-sector public health response. This disaster featured a lack of city, state, and federal coordination. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, approximately 1800 people from Louisiana, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, and Georgia lost their lives in Hurricane Katrina. 2 Five contributions to this special section look at promising community health practices that encourage predisaster planning and cross-sector coordination. In true Louisiana form, these contributions are a bit of a gumbo, looking at a variety of topics that affected community health, including public safety, cascading events, food access inequity, and community health workers as well as promising practices in pet evacuation and public health infrastructure.

Murphy et al. (p. 1490) examine the need for public health to integrate with public safety in predisaster planning as opposed to the commonplace postdisaster preparedness strategies. Murphy et al. note that lessons from Hurricane Katrina are vital for creating “a pathway to improve proactive cross-disciplinary integration and all-hazards preparedness.” (p1490) There remains a need to learn from the gaps impeding an integrated response, the federal evaluation of the Department of Homeland Security and Exercise and Evaluation Program, and the local response from the New Orleans City Assisted Evacuation framework.

Greenberg (p. 1493) urges hazard mitigation planning that includes cascading effects as a way to think beyond the natural disaster into certain “trigger events,” which can lead to deadly consequences. Greenberg highlights the need to systematically analyze how a single disaster event can cascade into multiple failures that substantially multiply severe consequences. Including cascading effects is another tool for coordinating public health and emergency response. Greenberg also looks at existing policy to coordinate these efforts through the Stafford Act.

Food access inequities were vastly expanded after Katrina. Rose and O’Malley (p. 1495) compare national programs and their food access approach, along with giving a historical perspective of programming to address the spectrum of food access issues in US metropolitan areas. Food Access 3.0 offers community-driven and socially innovative solutions to the decades-long issue of sustainable and healthy food access for families.

Haywood et al. (p. 1498) provide an account of responding to community needs and organization around community health workers during post-Katrina recovery. In the varied history of the use and acceptance of community health workers in the United States, Wennerstrom et al. describe how this necessary brigade of community liaisons organized to fill a devastating public health void in New Orleans. They state that community health workers “not only supported recovery from the devastation but also learned important lessons through organizing themselves into a professional association to support their growing workforce and influence policy.” (p1498)

Hurricane Katrina had a lasting impact on many policies in emergency preparedness and disaster response for pet safety. Babcock and Smith (p. 1500) review the critical work of disaster planning and pet safety and the lasting aftermath that changed public health policy and disaster response after Katrina. The Pets Evacuation and Transportation Standards Act of 2006, one of the early wins from dismal outcomes in New Orleans, was established with lessons learned following Hurricanes Gustav and Harvey. The need to train city, public health, and community members is key in any preparedness plan. New Orleans has shown innovation in offering training, both live and virtual, to prepare for future events.

Just as health and environmental systems have learned and evolved, so too has the public health system. As Gee (p. 1502) notes, the data systems and other critical public health infrastructure developed after Katrina have enabled more effective responses to the Baton Rouge floods and now COVID-19 than would have previously been possible. With each storm, public health systems improve to address the next one.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

See also Kim-Farley, p. 1448 , and the AJPH Hurricane Katrina 15 Years After section, pp. 1460 – 1503 .

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Browse content in Disability assessment

- Assessment for capacity to work

- Assessment of functional capability

- Browse content in Fitness for work

- Civil service, central government, and education establishments

- Construction industry

- Emergency Medical Services

- Fire and rescue service

- Healthcare workers

- Hyperbaric medicine

- Military - Other

- Military - Fitness for Work

- Military - Mental Health

- Oil and gas industry

- Police service

- Rail and Roads

- Remote medicine

- Telecommunications industry

- The disabled worker

- The older worker

- The young worker

- Travel medicine

- Women at work

- Browse content in Framework for practice

- Health and Safety at Work etc. Act 1974 and associated regulations

- Health information and reporting

- Ill health retirement

- Questionnaire Reviews

- Browse content in Occupational Medicine

- Blood borne viruses and other immune disorders

- Dermatological disorders

- Endocrine disorders

- Gastrointestinal and liver disorders

- Gynaecology

- Haematological disorders

- Mental health

- Neurological disorders

- Occupational cancers

- Opthalmology

- Renal and urological disorders

- Respiratory Disorders

- Rheumatological disorders

- Browse content in Rehabilitation

- Chronic disease

- Mental health rehabilitation

- Motivation for work

- Physical health rehabilitation

- Browse content in Workplace hazard and risk

- Biological/occupational infections

- Dusts and particles

- Occupational stress

- Post-traumatic stress

- Advance articles

- Editor's Choice

- Themed and Special Issues

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- Books for Review

- Become a Reviewer

- About Occupational Medicine

- About the Society of Occupational Medicine

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Permissions

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

- < Previous

Hurricane Katrina: an American tragedy

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Tee L. Guidotti, Hurricane Katrina: an American tragedy, Occupational Medicine , Volume 56, Issue 4, June 2006, Pages 222–224, https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqj043

- Permissions Icon Permissions

The true extent of the American tragedy that is Hurricane Katrina is still unfolding almost 12 months after the event and its implications may be far more reaching. Hurricane Katrina, which briefly became a Category 5 hurricane in the Gulf of Mexico, began as a storm in the western Atlantic. Katrina made landfall on Monday, 29 August 2005 at 6.30 p.m. in Florida as a Category 1 hurricane, turned north, gained strength and made landfall again at 7.10 a.m. in southeast Louisiana as a Category 4 hurricane and rapidly attenuated over land to a Category 3 hurricane. New Orleans is below sea level as a consequence of subsidence and because of elevation of the Mississippi river due to altered flow. The storm brought a nearly 4 m storm surge east of the eye, where the winds blew south to the south shore of Lake Pontchartrain, and gusts of 344 km/h at the storm's peak at ∼1.00 p.m. Levees protecting the city from adjacent Lake Pontchartrain failed, inundating 80% of the city to a depth of up to 8 m. Further east in the Gulf Coast, a storm surge of 10.4 m was recorded at Bay St Louis, Mississippi [ 1 , 2 ].

What followed was horrifying and discouraging. Poor residents and the immobilized were left stranded in squalor. Essential services failed. Heroic rescues were undertaken with wholly inadequate follow-up and resettlement [ 3 ]. Emergency response was feeble. It was only after the military intervened that the situation began, slowly, to improve. New Orleans and much of the Gulf Coast to the east is still a depleted, devitalized, largely uninhabitable wreck. Less than a month later, on 24 September, Hurricane Rita followed. A much stronger storm in magnitude, Rita caused further displacement and disruption in Texas, where evacuation measures, undertaken in near-ideal conditions, were shown to be completely inadequate.

Floods usually conceal more than they reveal. Hurricane Katrina was an exception. It revealed truths about disaster response in the United States that had been concealed. Now, months later, one may assess the response and recovery to the disaster, evaluate how the country handled the challenge and determine what lessons were, or could have been, learned.

Katrina revealed that natural disasters and public health crises are as much threats to national security as intentional assaults. An entire region that played a vital role in the American economy and a unique role in the country's culture ground to a halt. During Katrina and Rita, ∼19% of the nation's oil refining capacity and 25% of its oil producing capacity became unavailable [ 4 ]. The country temporarily lost 13% of its natural gas capacity. Together, the storms destroyed 113 offshore oil and gas platforms. The Port of New Orleans, the major cargo transportation hub of the southeast, was closed to operations. Commodities were not shipped or accessible, including, in one of those statistics that are revealing beyond their triviality, 27% of the nation's coffee beans [ 5 ]. Consequences of this magnitude are beyond the reach of conventional terrorist acts.

Katrina revealed the close interconnection between the natural environment and human health risk. The capacity of wetlands in the Gulf Region to absorb precipitation and to buffer the effects of such storms has been massively degraded in recent years by local development. This has been known for a very long time [ 6 ], but development yielded short-term economic gain while mitigation was expensive. Katrina also revealed that understanding the threat and the circumstances that enable it means nothing if no concrete preparations are taken. The disaster that struck New Orleans, specifically, was not only foreseeable but also understood to be inevitable. Emergency managers had participated in a tabletop exercise that followed essentially an identical scenario just 13 months before, called ‘Hurricane Pam’ [ 7 ]. Had their conclusions and recommendations been acted upon, the actual event may have turned out differently. Although the levees would still have failed, perhaps those responsible for safeguarding the people would not have done so.

Katrina revealed that the federal agency designed to protect all Americans was incompetent. The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) reached its peak under President Clinton, when it enjoyed Cabinet-level rank. Post 9-11 FEMA was subordinated within the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), a department highly focused on terrorism and intentional homeland threats. The wisdom of combining the two was always in doubt. The logical solution is to move FEMA out of DHS but so far there has been no political will to do so and FEMA is so reduced and depleted as an agency that it probably could not now operate at a Cabinet level even were it to have the authority [ 5 , 8 ].

Katrina revealed how large and resilient the American economy has become overall. The evidence for this is how quickly the country has returned to economic growth and business as usual, despite the destruction of a region once economically important [ 9 ]. Katrina devastated ≥223 000 km [ 2 ] of the United States, an area almost as large as Britain. Yet, with one exception, the economy of the country barely registered an effect, even on psychologically volatile indicators such as stock market indices. It is projected that Katrina, as such, will only reduce growth in GDP for the United States by about one half of 1%. Although the southeast region served by New Orleans is very large geographically, it constitutes only 1% of the total American economy [ 10 ]. The lower Mississippi region adds little of its own economic value to GDP, other than tourism and as a source of energy. The exception noted above, of course, was the price of oil, as reflected in the prices of gasoline and refined petroleum products.

Katrina revealed how marginal the Gulf Region had become to the American economy, despite the wealth that passes through it. New Orleans itself was a poor city—it probably still is, although the returning citizens obviously have sufficient resources to allow them to return—and its neighbours in Mississippi and Alabama are not rich, either. The region is economically significant mainly for tourism, transshipment of cargo, oil and gas and for redistribution of wealth (in the form of legalized gambling). Reconstruction efforts may even fuel an economic expansion in the rest of the economy, although precious little prosperity resulting from it is likely to be seen in the devastated Gulf itself anytime soon. Astonishingly, the compounded effect of the war in Iraq, the high price of crude oil and the direct effects of Hurricane Katrina did not set back growth in the American economy, although it may have kept stock market prices level to the end of 2005.

Katrina revealed the great divide that remains between people living next to one another but differing in the clustered characteristics of race, poverty, immobility and ill-health [ 11 , 12 ]. Those who lacked the resources, who could not fend for themselves, who were left behind, who happened to be sick were almost all African–American, and therefore so were the ones who died. Relatively, well off residents near the shore of Lake Pontchartrain also sustained many deaths [ 2 ]. However, the brunt of the storm was clearly borne by the poor and dispossessed. That this was not intentional does not make it any more acceptable.

Honour in this dishonourable story came from the role of rescue, medical, public health and occupational health professionals. Rescuers took personal risks to save the stranded citizens of New Orleans. Public health agencies quickly identified and documented the risks of water contamination [ 13 ], warned of risks from carbon monoxide from portable generators [ 14 ], identified dermatitis and wound infections as major health risks [ 15 ] and identified outbreaks of norovirus-induced gastroenteritis [ 16 ]. Occupational health clinics and occupational health physicians and nurses treated the injured, from wherever they came [ 17 ]. Occupational health professionals returned critical personnel to work as soon as it was possible, to hasten economic recovery and rebuilding. Occupational Safety and Health Administration professionals warned against hazards in the floodwaters and the destroyed, abandoned houses but supplies for personal protection were nowhere to be found. The American College of Occupational and Environmental Health served as a clearing-house for information and provided almost 200 participants with web-supported telephone training on Katrina-related hazards and measures to get workers back on the job safely.

It was not enough. No human effort could have been by then. But what can we, as a medical speciality, do better next time? The occupational health physician is not, as such, a specialist in emergency medicine, an expert in emergency management and incident command or a safety engineer, although many do have special expertise in these areas because of personal interest, prior training or military experience. The occupational health physician is, however, uniquely prepared to work with management and technical personnel at the plant, enterprise or corporate level. We can assist in preparing for plausible incidents, planning for an effective response, identifying resources that will be required, and advising on their deployment.

The occupational physician has critical roles to play in disaster preparedness and emergency management. Our role in disaster preparedness is distinct from those of safety engineering and risk managers. Our role in emergency management is distinct from those of emergency medicine and emergency management personnel. Our roles in both are complementary, sometimes overlapping and predicated on the value that we bring to the table as physicians familiar with facilities. We have the means to protect workers in harm's way and from the many hazards already so familiar from our daily work. Katrina demonstrates that occupational health professionals can translate experience of the ordinary to play an integral role in dealing with the extraordinary.

US National Interagency Coordinating Center. SITREP [Situation Report]: Combined Hurricanes Katrina & Rita. Access restricted but unclassified (3 January 2006 , date last accessed).

Wikipedia. Hurricane Katrina. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hurricane_Katrina (5 January 2006 , date last accessed).

Economist. When government fails, 2005 .

Bamberger RL, Kumins L. Oil and Gas: Supply Issues after Katrina. CRS Report for Congress RS222233. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, Library of Congress, 2005 .

Time 2005 ; 166 : 34 –41.

Louisiana Wetlands Protection Panel. Towards a Strategic Plan: A Proposed Study. Chapter 5. Report of the Louisiana Wetlands Protection Panel. Washington, DC: US Environmental Protection Agency, EPA Report No. 230-02-87-026, April 1987 . http://yosemite.epa.gov/oar/globalwarming.nsf/UniqueKeyLookup/SHSU5BURRY/$File/louisiana_5.pdf (6 January 2006, date last accessed).

Grunwald M, Glasser SB. Brown's turf wars sapped FEMA's strength. Washington Post 2005 ; 129 : A1 ,A8.

FEMA. Hurricane Pam exercise concludes. Region 4 Press Release R6-04-93. 24 July 2004 . http://www.fema.gov/news/newsrelease.fema?id=13051 (3 January 2005, date last accessed).

Samuelson RJ. Waiting for a soft landing. Washington Post 2006 ; 167 : A17 .

Fonda D. Billion-dollar blowout. Time 2005 ; 166 : 82 –83.

Atkins D, Moy EM. Left behind: the legacy of hurricane Katrina. Br Med J 2005 ; 331 : 916 –918.

Greenough PG, Kirsch TD. Hurricane Katrina: Public health response—assessing needs. N Engl J Med 2005 ; 353 : 1544 –1546.

Joint Taskforce. Environmental Health Needs and Habitability Assessment: Hurricane Katrina Response. Initial Assessment. Washington, DC and Atlanta, GA: US Environmental Protection Agency and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2005 .

MMWR. Surveillance for Illness and Injury After Hurricane Katrina—New Orleans, Louisiana , 2005 .

MMWR. Infectious Disease and Dermatologic Conditions in Evacuees and Rescue Workers after Hurricane Katrina—Multiple States, August–September, 2005 , 2005 ; 54 : 1 –4.

MMWR. Norovirus among Evacuees from Hurricane Katrina—Houston, Texas , 2005 .

McIntosh E. Occupational medicine response to Hurricane Katrina crisis. WOEMA Quarterly Newsletter (Western Occupational and Environmental Medical Association) 2005 , pp. 2, 7.

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Contact SOM

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1471-8405

- Print ISSN 0962-7480

- Copyright © 2024 Society of Occupational Medicine

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Monica Powers 1 2 *

AM J QUALITATIVE RES, Volume 8, Issue 1, pp. 89-106

https://doi.org/10.29333/ajqr/14086

OPEN ACCESS 1023 Views 764 Downloads

Download Full Text (PDF)

This study explored the lived experiences of residents of the Gulf Coast in the USA during Hurricane Katrina, which made landfall in August 2005 and caused insurmountable destruction throughout the area. A heuristic process and thematic analysis were employed to draw observations and conclusions about the lived experiences of each participant and make meaning through similar thoughts, feelings, and themes that emerged in the analysis of the data. Six themes emerged: (1) fear, (2) loss, (3) anger, (4) support, (5) spirituality, and (6) resilience. The results of this study allude to the possible psychological outcomes as a result of experiencing a traumatic event and provide an outline of what the psychological experience of trauma might entail. The current research suggests that preparedness and expectation are key to resilience and that people who feel that they have power over their situation fare better than those who do not.

Keywords: mass trauma, resilience, loss, natural disaster, mental health.

- American Psychological Association (2006). APA's response to international and national disasters and crises: Addressing diverse needs. 2005 annual report of the APA policy and planning board. American Psychologist, 61 (5), 513–521. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066x.61.5.513

- Ardila Sánchez, J. G., Houmanfar, R. A., & Alavosius, M. P. (2019). A descriptive analysis of the effects of weather disasters on community resilience. Behavior and Social Issues , 28 , 298–315. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42822-019-00015-w

- Bakic, H., & Ajdukovic, D. (2021). Resilience after natural disasters: the process of harnessing resources in communities differentially exposed to a flood. European Journal of Psychotraumatology , 12 (1), Article 1891733. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2021.1891733

- Bleich, S. N., Findling, M. G., Casey, L. S., Blendon, R. J., Benson, J. M., SteelFisher, G. K., Sayde, J. M. & Miller, C. (2019). Discrimination in the United States: experiences of black Americans. Health services research , 54 , 1399-1408. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.13220

- Boyatzis, R. E. (1998). Transforming qualitative information: Thematic analysis and code development . SAGE Publications.

- Brinkley, D. (2006). The great deluge: Hurricane Katrina, New Orleans, and the Mississippi Gulf Coast . Harper Collins E-books.

- Bronfenbrenner, U., & Evans, G. W. (2000). Developmental science in the 21st century: Emerging questions, theoretical models, research designs and empirical findings. Social Development, 9 (1), 115–125. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9507.00114

- Brunsma, D., Overfelt, D., & Picou, J. S. (Eds.). (2007). The sociology of Katrina: Perspectives on a modern catastrophe (1st ed.). Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.

- Bryant, R. A., Edwards, B., Creamer, M., O'Donnell, M., Forbes, D., Felmingham, K. L., Silove, D., Steel, Z., McFarlane, A. C., van Hoff, M., Nickerson, A., & Hadzi-Pavlovic, D. (2020). A population study of prolonged grief in refugees. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences , 29 , Article e44. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796019000386

- Bui, B. K. H., Anglewicz, P., & VanLandingham, M. J. (2021). The impact of early social support on subsequent health recovery after a major disaster: A longitudinal analysis. SSM-Population Health , 14, Article 100779. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ssmph.2021.100779

- Buras, K. L. (2020). From Katrina to Covid-19: How disaster, federal neglect, and the market compound racial inequities . National Education Policy Center. http://nepc.colorado.edu/publication/katrina-covid

- Calvo, R., Arcaya, M., Baum, C. F., Lowe, S. R., & Waters, M. C. (2015). Happily ever after? Pre-and-post disaster determinants of happiness among survivors of Hurricane Katrina. Journal of happiness studies , 16 , 427-442. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-014-9516-5

- CBC. (2005, September 8). Katrina Death Toll Could be Lower than Featured. CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/world/katrina-death-toll-could-be-lower-than-feared-1.550019

- Cherry, K. E. (2020). The other side of suffering: Finding a path to peace after tragedy . Oxford University Press.

- Colom, S., & Pelot-Hobbs, L. (2022). Constructing the unruly public: Governing affect and legitimate knowledge in post-Katrina New Orleans. Gender, Place & Culture , 29 (9), 1317–1337. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2021.1984215

- Dennis, M. R., Kunkel, A. D., Woods, G., & Schrodt, P. (2006). Making sense of New Orleans flood trauma recovery: Ethics, research design, and policy considerations for future disasters. Analyses of Social Issues & Public Policy, 6 (1), 191–213. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-2415.2006.00107.x

- Douglass, B. G., & Moustakas, C. (1985). Heuristic inquiry: The internal search to know. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 25 (3), 39–55. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022167885253004

- Drapalski, A., Bennett, M., & Bellack, A. (2011). Gender differences in substance use, consequences, motivation to change, and treatment seeking in people with serious mental illness. Substance Use & Misuse, 46 (6), 808–818. https://doi.org/10.3109/10826084.2010.538460

- Drury, J., Carter, H., Cocking, C., Ntontis, E., Tekin Guven, S., & Amlôt, R. (2019). Facilitating collective psychosocial resilience in the public in emergencies: Twelve recommendations based on the social identity approach. Frontiers in Public Health , 7 , Article 141. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2019.00141

- Ehrenreich, J. H. (2003). Understanding PTSD: Forgetting “trauma." Analyses of Social Issues & Public Policy, 3 (1), 15–28. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-2415.2003.00012.x

- Fussell, E. (2015). The long-term recovery of New Orleans’ population after Hurricane Katrina. American Behavioral Scientist , 59 (10), 1231-1245. https://doi.org/10.1177/000276421559118

- Garratt, D., & Stark, J. W. (2009, February 25). Post Katrina disaster response and recovery: Evaluating FEMA’s continuing efforts in the Gulf Coast and response to recent disasters . https://www.fema.gov/pdf/about/testimony/022509_testimony.pdf

- Gesi, C., Carmassi, C., Cerveri, G., Carpita, B., Cremone, I. M., & Dell'Osso, L. (2020). Complicated grief: what to expect after the coronavirus pandemic. Frontiers in psychiatry , 11 , Article 489. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00489

- Gheytanchi, A., Joseph, L., Gierlach, E., Kimpara, S., Housley, J., Franco, Z. E., et al. (2007). The dirty dozen: Twelve failures of the Hurricane Katrina response and how psychology can help. American Psychologist, 62 (2), 118–130. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.62.2.118

- Groen, J. A., & Polivka, A. E. (2008). Hurricane Katrina evacuees: Who they are, where they are, and how they are faring. Monthly Labor Review, 131 (3), 32–51.

- Groen, J. A., & Polivka, A. E. (2009). Going home after Hurricane Katrina: Determinants of return migration and changes in affected areas . U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

- Handayani, A. M. S., & Nurdin, N. (2021). Understanding women’s psychological well-being in post-natural disaster recovery. Medico Legal Update , 21 (3), 151–161.

- Jackson, B. (2005, September 16). Katrina: What happened when . https://www.factcheck.org/2005/09/katrina-what-happened-when/

- Jafari, H., Heidari, M., Heidari, S., & Sayfouri, N. (2020). Risk factors for suicidal behaviours after natural disasters: a systematic review. The Malaysian Journal of Medical Sciences: MJMS , 27 (3), 20–33. https://doi.org/ 10.21315/mjms2020.27.3.3

- Jiang, S., Postovit, L., Cattaneo, A., Binder, E. B., & Aitchison, K. J. (2019). Epigenetic modifications in stress response genes associated with childhood trauma. Frontiers in Psychiatry , 10 , Article 808. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00808

- King, L. S., Osofsky, J. D., Osofsky, H. J., Weems, C. F., Hansel, T. C., & Fassnacht, G. M. (2015). Perceptions of trauma and loss among children and adolescents exposed to disasters a mixed-methods study. Current Psychology , 34 , 524-536. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-015-9348-4

- Klopfer, A. N. (2017). “Choosing to Stay” Hurricane Katrina Narratives and the History of Claiming Place-Knowledge in New Orleans. Journal of Urban History , 43 (1), 115-139. https://doi.org/10.1177/009614421557

- Koslov, L., Merdjanoff, A., Sulakshana, E., & Klinenberg, E. (2021). When rebuilding no longer means recovery: the stress of staying put after Hurricane Sandy. Climatic Change , 165 (3-4), 59. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-021-03069-1

- Lee, E., & Lee, H. (2019). Disaster awareness and coping: Impact on stress, anxiety, and depression. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care, 55, 311–318. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppc.12351

- Maercker, A., Cloitre, M., Bachem, R., Schlumpf, Y. R., Khoury, B., Hitchcock, C., & Bohus, M. (2022). Complex post-traumatic stress disorder. The Lancet , 400 , 60–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00821-2

- Makwana, N. (2019). Disaster and its impact on mental health: A narrative review. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care , 8 (10), 3090–3095. https://doi.org/10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_893_19

- Manove, E. E., Lowe, S. R., Bonumwezi, J., Preston, J., Waters, M. C., & Rhodes, J. E. (2019). Posttraumatic growth in low-income Black mothers who survived Hurricane Katrina. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry , 89 (2), 144–158. https://doi.org/10.1037/ort0000398

- Mao, W., & Agyapong, V. I. (2021). The role of social determinants in mental health and resilience after disasters: Implications for public health policy and practice. Frontiers in Public Health , 9 , Article 658528. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.658528

- McLeish, A. C., & Del Ben, K. S. (2008). Symptoms of depression and posttraumatic stress disorder in an outpatient population before and after Hurricane Katrina. Depression & Anxiety (1091-4269), 25 (5), 416–421. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.20426

- Milanak, M. E., Zuromski, K. L., Cero, I., Wilkerson, A. K., Resnick, H. S., & Kilpatrick, D. G. (2019). Traumatic event exposure, posttraumatic stress disorder, and sleep disturbances in a national sample of US adults. Journal of Traumatic Stress , 32 (1), 14–22. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22360

- Moreno, J., & Shaw, D. (2019). Community resilience to power outages after disaster: A case study of the 2010 Chile earthquake and tsunami. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction , 34 , 448–458.

- Morganstein, J. C., & Ursano, R. J. (2020). Ecological disasters and mental health: causes, consequences, and interventions. Frontiers in Psychiatry , 11 , Article 1. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00001

- Raker, E. J., Lowe, S. R., Arcaya, M. C., Johnson, S. T., Rhodes, J., & Waters, M. C. (2019). Twelve years later: The long-term mental health consequences of Hurricane Katrina. Social Science & Medicine , 242 , 112610. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112610

- Silver, A., & Grek-Martin, J. (2015). “Now we understand what community really means”: Reconceptualizing the role of sense of place in the disaster recovery process. Journal of Environmental Psychology , 42 , 32–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2015.01.004

- Smith Lee, J. R., & Robinson, M. A. (2019). “That’s my number one fear in life. It’s the police”: Examining young Black men’s exposures to trauma and loss resulting from police violence and police killings. Journal of Black Psychology , 45 (3), 143-184. https://doi.org/10.1177/00957984198651

- South, J., Stansfield, J., Amlot, R., & Weston, D. (2020). Sustaining and strengthening community resilience throughout the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond. Perspectives in Public Health , 140 (6), 305–308. https://doi.org/10.1177/1757913920949

- Stough, L. M., Sharp, A. N., Resch, J. A., Decker, C., & Wilker, N. (2016). Barriers to the long‐term recovery of individuals with disabilities following a disaster. Disasters , 40 (3), 387-410. https://doi.org/10.1111/disa.12161

- Thompson, R. R., Jones, N. M., Holman, E. A., & Silver, R. C. (2019). Media exposure to mass violence events can fuel a cycle of distress. Science Advances , 5 (4), Article eaav3502. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aav3502

- Trethewey, N. (2010). Beyond Katrina: A meditation on the Mississippi Gulf Coast . University of Georgia Press.

- Weil, F. D., Rackin, H. M., & Maddox, D. (2018). Collective resources in the repopulation of New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina. Natural Hazards , 94, 927-952. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-018-3432-7

- Weissbecker, I. (2009). Mental health as a human right in the context of recovery after disaster and conflict. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 22 (1), 77–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515070902761065

- Williams, J. M., & Spruill, D. A. (2005). Surviving and thriving after trauma and loss. Journal of Creativity in Mental Health, 1 (3/4), 57–70. https://doi.org/10.1300/J456v01n03_04

- Yabe, T., Tsubouchi, K., Fujiwara, N., Sekimoto, Y., & Ukkusuri, S. V. (2020). Understanding post-disaster population recovery patterns. Journal of the Royal Society Interface , 17 (163), Article 20190532. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsif.2019.0532

The Fletcher Forum of World Affairs, Vol. 30:1 Winter 2006

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- BOOK REVIEW

- 17 June 2020

The devastating history of Hurricane Katrina, the next wave of universities, and a personal memoir of the HIV epidemic: Books in brief

- Andrew Robinson 0

Andrew Robinson’s numerous books include Earth-Shattering Events: Earthquakes, Nations and Civilization .

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Andy Horowitz Harvard Univ. Press (2020)

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

185,98 € per year

only 3,65 € per issue

Rent or buy this article

Prices vary by article type

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Nature 582 , 333 (2020)

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-01749-z

It’s time for your performance review

Futures 29 MAY 24

Time’s restless ocean

Futures 22 MAY 24

The origin of the cockroach: how a notorious pest conquered the world

News 20 MAY 24

Explaining novel scientific concepts to people whose technical acumen does not extend to turning it off, then turning it on again

Futures 15 MAY 24

Chief Editor

Job Title: Chief Editor Organisation: Nature Ecology & Evolution Location: New York, Berlin or Heidelberg - Hybrid working Closing date: June 23rd...

New York City, New York (US)

Springer Nature Ltd

Global Talent Recruitment (Scientist Positions)

Global Talent Gathering for Innovation, Changping Laboratory Recruiting Overseas High-Level Talents.

Beijing, China

Changping Laboratory

Postdoctoral Associate - Amyloid Strain Differences in Alzheimer's Disease

Houston, Texas (US)

Baylor College of Medicine (BCM)

Postdoctoral Associate- Bioinformatics of Alzheimer's disease

Postdoctoral associate- alzheimer's gene therapy.

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Contentious Politics and Political Violence

- Governance/Political Change

- Groups and Identities

- History and Politics

- International Political Economy

- Policy, Administration, and Bureaucracy

- Political Anthropology

- Political Behavior

- Political Communication

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Philosophy

- Political Psychology

- Political Sociology

- Political Values, Beliefs, and Ideologies

- Politics, Law, Judiciary

- Post Modern/Critical Politics

- Public Opinion

- Qualitative Political Methodology

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- World Politics

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Hurricane katrina: analyzing a mega-disaster.

- Arjen Boin , Arjen Boin Department of Public Institutions and Governance, Leiden University

- Christer Brown Christer Brown European Commission

- and James A. Richardson James A. Richardson Public Administration Institute, Louisiana State University

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.1575

- Published online: 28 February 2020

The response to Hurricane Katrina in 2005 has been widely described as a disaster in itself. Politicians, media, academics, survivors, and the public at large have slammed the federal, state, and local response to this mega disaster. According to the critics, the response was late, ineffective, politically charged, and even influenced by racist motives. But is this criticism true? Was the response really that poor? This article offers a framework for the analysis and assessment of a large-scale response to a mega disaster, which is then applied to the Katrina response (with an emphasis on New Orleans). The article identifies some failings (where the response could and should have been better) but also points to successes that somehow got lost in the politicized aftermath of this disaster. The article demonstrates the importance of a proper framework based on insights from crisis management studies.

- Hurricane Katrina

- U.S. disaster response

- New Orleans

- strategic crisis management

- crisis leadership

- crisis analysis

You do not currently have access to this article

Please login to access the full content.

Access to the full content requires a subscription

Printed from Oxford Research Encyclopedias, Politics. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a single article for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

date: 31 May 2024

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

- [66.249.64.20|185.66.15.189]

- 185.66.15.189

Character limit 500 /500

- Help & FAQ

Hurricane Katrina: Who Stayed and Why?

- Agricultural Economics, Sociology and Education

Research output : Contribution to journal › Article › peer-review

This paper contributes to the growing body of social science research on population displacement from disasters by examining the social determinants of evacuation behavior. It seeks to clarify the effects of race and socioeconomic status on evacuation outcomes vis-a-vis previous research on Hurricane Katrina, and it expands upon prior research on evacuation behavior more generally by differentiating non-evacuees according to their reasons for staying. This research draws upon the Harvard Medical School Hurricane Katrina Community Advisory Group's 2006 survey of individuals affected by Hurricane Katrina. Using these data, we develop two series of logistic regression models. The first set of models predicts the odds that respondents evacuated prior to the storm, relative to delayed- or non-evacuation; the second group of models predicts the odds that non-evacuees were unable to evacuate relative to having chosen to stay. We find that black and low-education respondents were least likely to evacuate prior to the storm and among non-evacuees, most likely to have been unable to evacuate. Respondents' social networks, information attainment, and geographic location also affected evacuation behavior. We discuss these findings and outline directions for future research.

All Science Journal Classification (ASJC) codes

- Management, Monitoring, Policy and Law

Access to Document

- 10.1007/s11113-013-9302-9

Other files and links

- Link to publication in Scopus

- Link to the citations in Scopus

Fingerprint

- hurricane Earth & Environmental Sciences 100%

- socioeconomic status Earth & Environmental Sciences 26%

- social network Earth & Environmental Sciences 23%

- social science Earth & Environmental Sciences 22%

- disaster Social Sciences 21%

- social status Social Sciences 20%

- logistics Social Sciences 20%

- determinants Social Sciences 18%

T1 - Hurricane Katrina

T2 - Who Stayed and Why?

AU - Thiede, Brian C.

AU - Brown, David L.

N1 - Funding Information: Acknowledgments This article benefitted greatly from the insights of Max Pfeffer, Scott Sanders, Laura Hathaway, and anonymous reviewers. The authors alone are responsible for mistakes of any kind. This research was supported by the Cornell Population Center, Cornell Population and Development Program, and USDA multi-state research project W-2001 ‘‘Population Dynamics and Change: Aging, Ethnicity and Land Use Change in Rural Communities,’’ administered by the Cornell University Agricultural Experiment Station project 159-6808.

PY - 2013/12

Y1 - 2013/12

N2 - This paper contributes to the growing body of social science research on population displacement from disasters by examining the social determinants of evacuation behavior. It seeks to clarify the effects of race and socioeconomic status on evacuation outcomes vis-a-vis previous research on Hurricane Katrina, and it expands upon prior research on evacuation behavior more generally by differentiating non-evacuees according to their reasons for staying. This research draws upon the Harvard Medical School Hurricane Katrina Community Advisory Group's 2006 survey of individuals affected by Hurricane Katrina. Using these data, we develop two series of logistic regression models. The first set of models predicts the odds that respondents evacuated prior to the storm, relative to delayed- or non-evacuation; the second group of models predicts the odds that non-evacuees were unable to evacuate relative to having chosen to stay. We find that black and low-education respondents were least likely to evacuate prior to the storm and among non-evacuees, most likely to have been unable to evacuate. Respondents' social networks, information attainment, and geographic location also affected evacuation behavior. We discuss these findings and outline directions for future research.

AB - This paper contributes to the growing body of social science research on population displacement from disasters by examining the social determinants of evacuation behavior. It seeks to clarify the effects of race and socioeconomic status on evacuation outcomes vis-a-vis previous research on Hurricane Katrina, and it expands upon prior research on evacuation behavior more generally by differentiating non-evacuees according to their reasons for staying. This research draws upon the Harvard Medical School Hurricane Katrina Community Advisory Group's 2006 survey of individuals affected by Hurricane Katrina. Using these data, we develop two series of logistic regression models. The first set of models predicts the odds that respondents evacuated prior to the storm, relative to delayed- or non-evacuation; the second group of models predicts the odds that non-evacuees were unable to evacuate relative to having chosen to stay. We find that black and low-education respondents were least likely to evacuate prior to the storm and among non-evacuees, most likely to have been unable to evacuate. Respondents' social networks, information attainment, and geographic location also affected evacuation behavior. We discuss these findings and outline directions for future research.

UR - http://www.scopus.com/inward/record.url?scp=84888044638&partnerID=8YFLogxK

UR - http://www.scopus.com/inward/citedby.url?scp=84888044638&partnerID=8YFLogxK

U2 - 10.1007/s11113-013-9302-9

DO - 10.1007/s11113-013-9302-9

M3 - Article

AN - SCOPUS:84888044638

SN - 0167-5923

JO - Population Research and Policy Review

JF - Population Research and Policy Review

Advertisement

Hurricane Katrina: Who Stayed and Why?

- Published: 05 September 2013

- Volume 32 , pages 803–824, ( 2013 )

Cite this article

- Brian C. Thiede 1 &

- David L. Brown 1

3128 Accesses

60 Citations

1 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

This paper contributes to the growing body of social science research on population displacement from disasters by examining the social determinants of evacuation behavior. It seeks to clarify the effects of race and socioeconomic status on evacuation outcomes vis-a-vis previous research on Hurricane Katrina, and it expands upon prior research on evacuation behavior more generally by differentiating non-evacuees according to their reasons for staying. This research draws upon the Harvard Medical School Hurricane Katrina Community Advisory Group’s 2006 survey of individuals affected by Hurricane Katrina. Using these data, we develop two series of logistic regression models. The first set of models predicts the odds that respondents evacuated prior to the storm, relative to delayed- or non-evacuation; the second group of models predicts the odds that non-evacuees were unable to evacuate relative to having chosen to stay. We find that black and low-education respondents were least likely to evacuate prior to the storm and among non-evacuees, most likely to have been unable to evacuate. Respondents’ social networks, information attainment, and geographic location also affected evacuation behavior. We discuss these findings and outline directions for future research.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

An empirical analysis of hurricane evacuation expenditures.

High-resolution human mobility data reveal race and wealth disparities in disaster evacuation patterns

Disaster Disparities and Differential Recovery in New Orleans

As justified later in the paper and in footnote #10, we use a measure of education as an indicator of household socioeconomic status. We refer to “education effects” when discussing the particular findings of our statistical models, but refer to “socioeconomic status” when discussing the conceptualization of our research question and referring to previous literature on evacuation behavior, which has utilized multiple indicators of socioeconomic status.

An extensive review by Dash and Gladwin ( 2007 ) demonstrates that previous research on this topic has examined the effect of numerous other characteristics of evacuees and non-evacuees (e.g., gender), as well as the psychosocial dimensions of the evacuation process.

Gallup Poll #2005-45.

Household evacuation strategies were categorized according to (a) the timing of evacuation and (b) whether or not household members remained united or divided.

Both Elliott and Pais ( 2006 ) and Haney et al. ( 2007 ) report a number of other statistically significant factors in their models. Elliot and Pais find significant gender differences in some comparisons. Haney et al. observe significant differences in evacuation strategies according to employment, religion, and sex. Because they do not interact with or otherwise affect their findings regarding race and socioeconomic status, we exclude this from our discussion for the sake of brevity.

“Affected areas” are defined as those counties and parishes that were declared eligible for “individual assistance” by FEMA.

Adjustments were made for overlap in the sampling frames (see Hurricane Katrina Community Advisory Group 2006 for details).

To easily interpret odds ratios <1.000, one should invert the coefficient \(\left( {\frac{1}{\beta }} \right)\) . The quotient expresses the degree to which respondents in group k of variable x i were less likely to experience outcome Y 1 than those in the reference group, in the same terms as coefficients above 1.000.

Although an income variable was also available, we found that education and income were significantly and strongly correlated ( r = 0.417). We chose to use education and exclude the income variable for two primary reasons. First, the income variable reports household income, which is not appropriate given that our outcome and all other explanatory variables are individual-level indicators. Second, income is more prone to reporting bias than education.

We consider responses of 0–4 to either of the following questions “low” and responses of 5+ “high”: (1) “about how many friends or relatives in the county/parish were you close enough to that you could talk about your private feelings without feeling embarrassed?”; and (2) “about how many friends or relatives who did not live in the country/parish were you close enough to that you could talk about your private feelings without feeling embarrassed?” The median responses to these questions were 5.0 and 4.0, respectively, therefore 4.0 provides a reasonable central point around which to assign respondents to these categories.

Although some respondents’ social network classification may reflect socially insignificant county/parish boundary lines, we have no reason to believe that the distribution of such boundary effects is non-random across the four social network categories or any other variable in our statistical models.

We also consider the possibility that information attainment reflects the respondent’s connection to (isolation from) mainstream society.

This variable consists of three categories: we consider 0–4 recommendations “low” information attainment, 5–15 “medium”, and 16 or greater “high.” These thresholds distribute respondents as evenly as possible across the three categories.

Tables 2 and 3 show the percentage of respondents in each category of each explanatory variable that experienced a given evacuation outcome. For example, we show that among high school dropouts, 31.2 % evacuated prior to the storm and 68.8 % did not evacuate prior to the storm.

This includes systematic reporting biases.

Due to confidentiality restrictions, we were unable to obtain respondents’ zip codes of residence from the Harvard study to link community- and individual-level data. We would have liked, for example, to examine whether living in neighborhoods with high poverty or nativity rates affected the odds that an individual evacuated and the reason for not evacuating.

Barnshaw, J., & Trainor, J. (2007). Race, class, and capital amidst the Hurricane Katrina diaspora. In D. L. Brunsma, D. Overfelt, & J. S. Picou (Eds.), The sociology of Katrina: Perspectives on a modern catastrophe (pp. 91–105). New York: Rowman and Littlefield.

Google Scholar

Campanella, R. (2008). Bienville’s dilemma: A historical geography of new orleans . Lafayette: Center for Louisiana Studies.

Cutter, S. L., Boruff, B. J., & Lynn Shirley, W. (2003). Social vulnerability to environmental hazards. Social Science Quarterly, 84 (2), 242–261.

Article Google Scholar

Dash, N., & Gladwin, H. (2007). Evacuation decision making and behavioral responses: Individual and household. Natural Hazards Review, 8 (3), 69–77.

Dyson, M. E. (2006). Come hell or high water: Hurricane Katrina and the color of disaster . New York: Basic Books.

Elliott, J. R., & Pais, J. (2006). Race, class, and Hurricane Katrina: Social differences in human responses to disaster. Social Science Research, 35 (2), 295–321.

Falk, W. W. (2004). Rooted in place: Family and belonging in a southern black community . New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

Falk, W. W., Hunt, M. O., & Hunt, L. L. (2006). Hurricane Katrina and New Orleanians’ sense of place: Return and reconstitution or ‘gone with the wind’? Du Bois Review, 3 (1), 115–128.

Finch, C., Emrich, C. T., & Cutter, S. L. (2010). Disaster disparities and differential recovery in New Orleans. Population and Environment, 31 (4), 179–202.

Fothergill, A., Maestas, Enrique G. M., & Darlington, J. D. (1999). Race, ethnicity, and disaster in the United States: A review of the literature. Disasters, 23 (2), 156–173.

Fothergill, A., & Peek, L. A. (2004). Poverty and disasters in the United States: A review of recent sociological findings. Natural Hazards, 32 (1), 89–110.

Fussell, E. (2005). Leaving New Orleans: Social stratification, networks, and hurricane evacuation. Understanding Katrina , Social Science Research Council. http://understandingkatrina.ssrc.org/fussell . Accessed 30 Dec 2012.

Gladwin, H., & Peacock, W. G. (1997). Warning and evacuation: A night for hard houses. In W. G. Peacock, B. H. Morrow, & H. Gladwin (Eds.), Hurricane Andrew: Ethnicity, gender, and the sociology of disasters (pp. 52–74). New York: Routledge.

Groen, J. A., & Polivka, A. E. (2008). The effect of Hurricane Katrina of the labor market outcomes of evacuees. The American Economic Review, 98 (2), 43–48.

Groen, J. A., & Polivka, A. E. (2010). Going home after Hurricane Katrina: Determinants of return migration and changes in affected areas. Demography, 47 (4), 821–844.

Haney, T. J., Elliot, J. R., & Fussell, E. (2007). Families and Hurricane response: Evacuation, separation, and the emotional toll of Hurricane Katrina. In D. L. Brunsma, D. Overfelt, & J. S. Picou (Eds.), The Sociology of Katrina: Perspectives on a Modern Catastrophe (pp. 71–90). New York: Rowman and Littlefield.

Hori, M., & Shafer, M. J. (2010). Social costs of displacement in Louisiana after Hurricanes Katrina and Rita. Population and Environment, 31 (1–3), 64–86.

Hosmer, D. W., & Lemeshow, S. (1989). Applied logistic regression . New York: Wiley.

Hunter, L. (2005). Migration and environmental hazards. Population and Environment, 26 (4), 273–302.

Hurricane Katrina Community Advisory Group. (2006). Overview of Baseline Survey Results: Hurricane Katrina Community Advisory Group. www.hurricanekatrina.med.harvard.edu . Accessed 30 Dec 2012.

Kessler, R. C. (2009). Hurricane Katrina community advisory group study [United States] . Ann Arbor: Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research.

Knabb, R. D., Rhome, J. R., & Brown, D. P. (2005). Tropical cyclone report: Hurricane Katrina . Washington: NOAA.

Logan, J. (2012). Making a place for space: Spatial thinking in social science. Annual Review of Sociology, 38 (1), 507–524.

Massey, D. (1990). Social structure, household strategies, and the cumulative causation of migration. Population Index, 56 (1), 3–26.

Mileti, D. S. (2001). Disasters by design: A reassessment of natural hazards in the United States . Washington: Joseph Henry.

Morrow, B. H. (1997). Stretching the bonds: the families of Andrew. In W. G. Peacock, B. H. Morrow, & H. Gladwin (Eds.), Hurricane Andrew: Ethnicity, gender, and the sociology of disasters (pp. 141–170). New York: Routledge.

Morrow, B. H. (1999). Identifying and mapping community vulnerability. Disasters, 23 (1), 1–18.

Myers, C. A., Slack, T., & Singelmann, J. (2008). Social vulnerability and migration in the wake of disaster: The case of Hurricane Katrina and Rita. Population and Environment, 29 (6), 271–291.

Picou, J. S., & Marshall, B. K. (2007). Katrina as a paradigm shift: Reflections on disaster research in the twenty-first century. In D. L. Brunsma, D. Overfelt, & J. S. Picou (Eds.), The Sociology of Katrina: Perspectives on a modern catastrophe (pp. 1–20). New York: Rowman and Littlefield.

Smith, S. K., & McCarty, C. (2009). Fleeing the storm(s): An examination of evacuation behavior during Florida’s 2004 Hurricane season. Demography, 46 (1), 127–145.

Stark, O., & Bloom, D. E. (1985). The new economics of labor migration. The American Economic Review, 72 (2), 173–178.

Stein, R. M., Dueñas-Osorio, L., & Subramanian, D. (2010). Who evacuates when hurricanes approach? The role of risk, information, and location. Social Science Quarterly, 91 (3), 816–834.

Stringfield, J. D. (2010). Higher ground: An exploratory analysis of characteristics affecting returning populations after Hurricane Katrina. Population and Environment, 31 (1–3), 43–63.

Wisner, B., Blaikie, P., Cannon, T., & Davis, I. (Eds.). (2004). At risk: Natural hazards, people’s vulnerability, and disasters (2nd ed.). New York: Routledge.

Zhang, Y., Prater, C. S., & Lindell, M. K. (2004). Risk area accuracy and evacuation from Hurricane Bret. Natural Hazards Review, 5 (3), 115–120.

Zottarelli, L. K. (2008). Post-Hurricane Katrina employment and recovery: The interaction of race and place. Social Science Quarterly, 89 (3), 592–607.

Download references

Acknowledgments

This article benefitted greatly from the insights of Max Pfeffer, Scott Sanders, Laura Hathaway, and anonymous reviewers. The authors alone are responsible for mistakes of any kind. This research was supported by the Cornell Population Center, Cornell Population and Development Program, and USDA multi-state research project W-2001 “Population Dynamics and Change: Aging, Ethnicity and Land Use Change in Rural Communities,” administered by the Cornell University Agricultural Experiment Station project 159-6808.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Development Sociology, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, 14853, USA

Brian C. Thiede & David L. Brown

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Brian C. Thiede .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Thiede, B.C., Brown, D.L. Hurricane Katrina: Who Stayed and Why?. Popul Res Policy Rev 32 , 803–824 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-013-9302-9

Download citation

Received : 28 January 2013

Accepted : 03 August 2013

Published : 05 September 2013

Issue Date : December 2013

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-013-9302-9

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Hurricane Katrina

- Social networks

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Bulletin on Aging & Health

Mortality Impacts of Hurricane Katrina

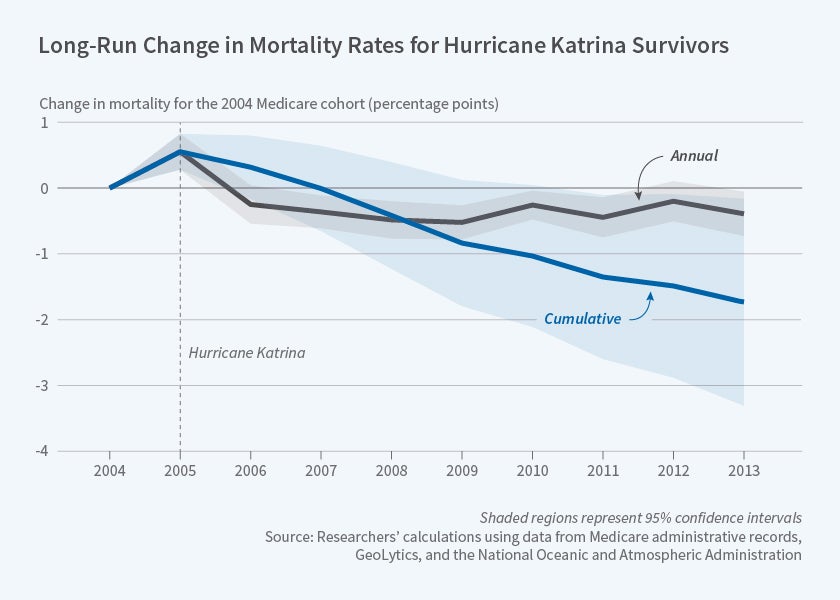

Hurricane Katrina was the costliest storm of its type to ever strike the U.S. mainland. The 2005 storm killed nearly 2,000 individuals and displaced more than one million residents, resulting in the largest migration of U.S. residents since the 1930s Dust Bowl. While the immediate death toll of the storm is well known, the long-term effects of the storm and resulting displacement on health and longevity are less well understood. Former New Orleans residents dispersed across the U.S., raising the possibility that local conditions may have affected the health of movers. In Does When You Die Depend on Where You Live? Evidence from Hurricane Katrina (NBER Working Paper No. 24822 ), researchers T atyana Deryugina and David Molitor examine the long-run mortality impacts of Hurricane Katrina on the elderly and disabled population of New Orleans.

This vulnerable population was deeply impacted by the hurricane — over one half of those killed by the immediate impact of the storm were over age 75, and elderly Medicare beneficiaries made up one-fifth of the displaced population. While the storm and subsequent displacement may have been scarring for this group's health in the short term, moving to areas with better economic and health outcomes may have generated long-term health benefits. Using Medicare administrative data, the researchers identify Medicare beneficiaries living in New Orleans before the storm and track their mobility and mortality over the following eight years. They compare the mortality outcomes of this group to a comparable group of beneficiaries living in 10 control cities before the storm. The researchers find that the mortality rate of the New Orleans beneficiaries was 0.5 percentage points higher in 2005 (the year of the storm), representing an increase of over 10 percent. Most of these excess deaths occurred within a week of the hurricane's landfall. By contrast, Hurricane Katrina led to sustained mortality reductions over the following eight years for those living in New Orleans at the time of the storm. Including the initial storm-related deaths, the hurricane increased the probability of surviving to 2013 by 1.7 percentage points, a nearly 3 percent increase relative to the eight-year survival probability. This result is not explained by healthier beneficiaries being more likely to survive the storm, since the calculation includes storm-related deaths. To explore the role of place in health, the researchers compare mortality outcomes for elderly beneficiaries who left New Orleans for low-mortality regions versus those who left for high-mortality regions. They find a strong relationship between mortality in the destination region and the movers' mortality — with every one-point increase in the destination mortality rate, there is a 0.8 to 0.9 point increase in the movers' mortality. They estimate that 70 percent of the long-run mortality decline is attributable to the change in local mortality rate experienced by hurricane victims. Despite a high death toll in the immediate aftermath of the storm, Hurricane Katrina reduced long-run mortality among elderly and disabled Medicare beneficiaries by inducing relocation to lower-mortality regions. This study joins a growing literature highlighting the critical effect of place on health. As the researchers note, "[o]ur finding that a migrant's individual mortality risk corresponds closely to the destination region's mortality rate suggests that local public health conditions are an important determinant of individual health outcomes, at least for the elderly and disabled populations."

The authors acknowledge funding from the National Institute on Aging (grant R21AG050795).

Researchers

Working groups, conferences.

NBER periodicals and newsletters may be reproduced freely with appropriate attribution.

More from NBER

In addition to working papers , the NBER disseminates affiliates’ latest findings through a range of free periodicals — the NBER Reporter , the NBER Digest , the Bulletin on Retirement and Disability , the Bulletin on Health , and the Bulletin on Entrepreneurship — as well as online conference reports , video lectures , and interviews .

© 2023 National Bureau of Economic Research. Periodical content may be reproduced freely with appropriate attribution.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Hurricane Katrina

- Most Cited Papers

- Most Downloaded Papers

- Newest Papers

- Save to Library

- Last »

- Hurricanes Follow Following

- New Orleans Follow Following

- Incident Command System Follow Following

- Graphic Narrative Follow Following

- Cinematic Affect Follow Following

- Geotourism- Sustainable Tourism- Tourism Geography Follow Following

- Geoconservation Follow Following

- Culture of Cuteness Follow Following

- Geoheritage Follow Following

- Policy Analysis/Policy Studies Follow Following

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- Academia.edu Publishing

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

- Afghanistan

- Budget Management

- Environment

- Global Diplomacy

- Health Care

- Homeland Security

- Immigration

- International Trade

- Judicial Nominations

- Middle East

- National Security

- Current News

- Press Briefings

- Proclamations

- Executive Orders

- Setting the Record Straight

- Ask the White House

- White House Interactive

- President's Cabinet

- USA Freedom Corps

- Faith-Based & Community Initiatives

- Office of Management and Budget

- National Security Council

- Nominations

Chapter Five: Lessons Learned

This government will learn the lessons of Hurricane Katrina. We are going to review every action and make necessary changes so that we are better prepared for any challenge of nature, or act of evil men, that could threaten our people.

-- President George W. Bush, September 15, 2005 1

The preceding chapters described the dynamics of the response to Hurricane Katrina. While there were numerous stories of great professionalism, courage, and compassion by Americans from all walks of life, our task here is to identify the critical challenges that undermined and prevented a more efficient and effective Federal response. In short, what were the key failures during the Federal response to Hurricane Katrina?

Hurricane Katrina Critical Challenges

- National Preparedness

- Integrated Use of Military Capabilities

- Communications

- Logistics and Evacuations

- Search and Rescue

- Public Safety and Security

- Public Health and Medical Support

- Human Services

- Mass Care and Housing

- Public Communications

- Critical Infrastructure and Impact Assessment

- Environmental Hazards and Debris Removal

- Foreign Assistance

- Non-Governmental Aid

- Training, Exercises, and Lessons Learned

- Homeland Security Professional Development and Education

- Citizen and Community Preparedness

We ask this question not to affix blame. Rather, we endeavor to find the answers in order to identify systemic gaps and improve our preparedness for the next disaster – natural or man-made. We must move promptly to understand precisely what went wrong and determine how we are going to fix it.

After reviewing and analyzing the response to Hurricane Katrina, we identified seventeen specific lessons the Federal government has learned. These lessons, which flow from the critical challenges we encountered, are depicted in the accompanying text box. Fourteen of these critical challenges were highlighted in the preceding Week of Crisis section and range from high-level policy and planning issues (e.g., the Integrated Use of Military Capabilities) to operational matters (e.g., Search and Rescue). 2 Three other challenges – Training, Exercises, and Lessons Learned; Homeland Security Professional Development and Education; and Citizen and Community Preparedness – are interconnected to the others but reflect measures and institutions that improve our preparedness more broadly. These three will be discussed in the Report’s last chapter, Transforming National Preparedness.

Some of these seventeen critical challenges affected all aspects of the Federal response. Others had an impact on a specific, discrete operational capability. Yet each, particularly when taken in aggregate, directly affected the overall efficiency and effectiveness of our efforts. This chapter summarizes the challenges that ultimately led to the lessons we have learned. Over one hundred recommendations for corrective action flow from these lessons and are outlined in detail in Appendix A of the Report.

Critical Challenge: National Preparedness

Our current system for homeland security does not provide the necessary framework to manage the challenges posed by 21st Century catastrophic threats. But to be clear, it is unrealistic to think that even the strongest framework can perfectly anticipate and overcome all challenges in a crisis. While we have built a response system that ably handles the demands of a typical hurricane season, wildfires, and other limited natural and man-made disasters, the system clearly has structural flaws for addressing catastrophic events. During the Federal response to Katrina 3 , four critical flaws in our national preparedness became evident: Our processes for unified management of the national response; command and control structures within the Federal government; knowledge of our preparedness plans; and regional planning and coordination. A discussion of each follows below.

Unified Management of the National Response

Effective incident management of catastrophic events requires coordination of a wide range of organizations and activities, public and private. Under the current response framework, the Federal government merely “coordinates” resources to meet the needs of local and State governments based upon their requests for assistance. Pursuant to the National Incident Management System (NIMS) and the National Response Plan (NRP), Federal and State agencies build their command and coordination structures to support the local command and coordination structures during an emergency. Yet this framework does not address the conditions of a catastrophic event with large scale competing needs, insufficient resources, and the absence of functioning local governments. These limitations proved to be major inhibitors to the effective marshalling of Federal, State, and local resources to respond to Katrina.

Soon after Katrina made landfall, State and local authorities understood the devastation was serious but, due to the destruction of infrastructure and response capabilities, lacked the ability to communicate with each other and coordinate a response. Federal officials struggled to perform responsibilities generally conducted by State and local authorities, such as the rescue of citizens stranded by the rising floodwaters, provision of law enforcement, and evacuation of the remaining population of New Orleans, all without the benefit of prior planning or a functioning State/local incident command structure to guide their efforts.

The Federal government cannot and should not be the Nation’s first responder. State and local governments are best positioned to address incidents in their jurisdictions and will always play a large role in disaster response. But Americans have the right to expect that the Federal government will effectively respond to a catastrophic incident. When local and State governments are overwhelmed or incapacitated by an event that has reached catastrophic proportions, only the Federal government has the resources and capabilities to respond. The Federal government must therefore plan, train, and equip to meet the requirements for responding to a catastrophic event.

Command and Control Within the Federal Government