Got any suggestions?

We want to hear from you! Send us a message and help improve Slidesgo

Top searches

Trending searches

15 templates

26 templates

49 templates

american history

76 templates

great barrier reef

17 templates

39 templates

Problem-based Learning

It seems that you like this template, problem-based learning presentation, premium google slides theme, powerpoint template, and canva presentation template.

Download the "Problem-based Learning" presentation for PowerPoint or Google Slides and prepare to receive useful information. Even though teachers are responsible for disseminating knowledge to their students, they also embarked on a learning journey since the day they decided to dedicate themselves to education. You might find this Google Slides and PowerPoint presentation useful, as it's already completed with actual content provided by educators. It could also be interesting for parents of school-age children or teenagers.

Features of this template

- Designed for teachers and parents

- 100% editable and easy to modify

- Different slides to impress your audience

- Contains easy-to-edit graphics such as graphs, maps, tables, timelines and mockups

- Includes 500+ icons and Flaticon’s extension for customizing your slides

- Designed to be used in Google Slides, Canva, and Microsoft PowerPoint

- Includes information about fonts, colors, and credits of the resources used

- Available in different languages

What are the benefits of having a Premium account?

What Premium plans do you have?

What can I do to have unlimited downloads?

Don’t want to attribute Slidesgo?

Gain access to over 25200 templates & presentations with premium from 1.67€/month.

Are you already Premium? Log in

Available in

Related posts on our blog.

How to Add, Duplicate, Move, Delete or Hide Slides in Google Slides

How to Change Layouts in PowerPoint

How to Change the Slide Size in Google Slides

Related presentations.

Premium template

Unlock this template and gain unlimited access

Register for free and start editing online

Problem-Based Learning (PBL)

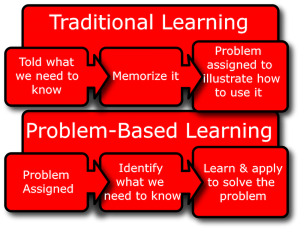

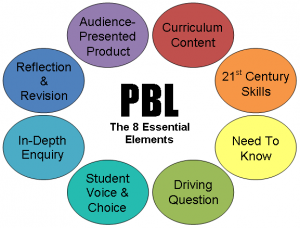

What is Problem-Based Learning (PBL)? PBL is a student-centered approach to learning that involves groups of students working to solve a real-world problem, quite different from the direct teaching method of a teacher presenting facts and concepts about a specific subject to a classroom of students. Through PBL, students not only strengthen their teamwork, communication, and research skills, but they also sharpen their critical thinking and problem-solving abilities essential for life-long learning.

See also: Just-in-Time Teaching

In implementing PBL, the teaching role shifts from that of the more traditional model that follows a linear, sequential pattern where the teacher presents relevant material, informs the class what needs to be done, and provides details and information for students to apply their knowledge to a given problem. With PBL, the teacher acts as a facilitator; the learning is student-driven with the aim of solving the given problem (note: the problem is established at the onset of learning opposed to being presented last in the traditional model). Also, the assignments vary in length from relatively short to an entire semester with daily instructional time structured for group work.

By working with PBL, students will:

- Become engaged with open-ended situations that assimilate the world of work

- Participate in groups to pinpoint what is known/ not known and the methods of finding information to help solve the given problem.

- Investigate a problem; through critical thinking and problem solving, brainstorm a list of unique solutions.

- Analyze the situation to see if the real problem is framed or if there are other problems that need to be solved.

How to Begin PBL

- Establish the learning outcomes (i.e., what is it that you want your students to really learn and to be able to do after completing the learning project).

- Find a real-world problem that is relevant to the students; often the problems are ones that students may encounter in their own life or future career.

- Discuss pertinent rules for working in groups to maximize learning success.

- Practice group processes: listening, involving others, assessing their work/peers.

- Explore different roles for students to accomplish the work that needs to be done and/or to see the problem from various perspectives depending on the problem (e.g., for a problem about pollution, different roles may be a mayor, business owner, parent, child, neighboring city government officials, etc.).

- Determine how the project will be evaluated and assessed. Most likely, both self-assessment and peer-assessment will factor into the assignment grade.

Designing Classroom Instruction

See also: Inclusive Teaching Strategies

- Take the curriculum and divide it into various units. Decide on the types of problems that your students will solve. These will be your objectives.

- Determine the specific problems that most likely have several answers; consider student interest.

- Arrange appropriate resources available to students; utilize other teaching personnel to support students where needed (e.g., media specialists to orientate students to electronic references).

- Decide on presentation formats to communicate learning (e.g., individual paper, group PowerPoint, an online blog, etc.) and appropriate grading mechanisms (e.g., rubric).

- Decide how to incorporate group participation (e.g., what percent, possible peer evaluation, etc.).

How to Orchestrate a PBL Activity

- Explain Problem-Based Learning to students: its rationale, daily instruction, class expectations, grading.

- Serve as a model and resource to the PBL process; work in-tandem through the first problem

- Help students secure various resources when needed.

- Supply ample class time for collaborative group work.

- Give feedback to each group after they share via the established format; critique the solution in quality and thoroughness. Reinforce to the students that the prior thinking and reasoning process in addition to the solution are important as well.

Teacher’s Role in PBL

See also: Flipped teaching

As previously mentioned, the teacher determines a problem that is interesting, relevant, and novel for the students. It also must be multi-faceted enough to engage students in doing research and finding several solutions. The problems stem from the unit curriculum and reflect possible use in future work situations.

- Determine a problem aligned with the course and your students. The problem needs to be demanding enough that the students most likely cannot solve it on their own. It also needs to teach them new skills. When sharing the problem with students, state it in a narrative complete with pertinent background information without excessive information. Allow the students to find out more details as they work on the problem.

- Place students in groups, well-mixed in diversity and skill levels, to strengthen the groups. Help students work successfully. One way is to have the students take on various roles in the group process after they self-assess their strengths and weaknesses.

- Support the students with understanding the content on a deeper level and in ways to best orchestrate the various stages of the problem-solving process.

The Role of the Students

See also: ADDIE model

The students work collaboratively on all facets of the problem to determine the best possible solution.

- Analyze the problem and the issues it presents. Break the problem down into various parts. Continue to read, discuss, and think about the problem.

- Construct a list of what is known about the problem. What do your fellow students know about the problem? Do they have any experiences related to the problem? Discuss the contributions expected from the team members. What are their strengths and weaknesses? Follow the rules of brainstorming (i.e., accept all answers without passing judgment) to generate possible solutions for the problem.

- Get agreement from the team members regarding the problem statement.

- Put the problem statement in written form.

- Solicit feedback from the teacher.

- Be open to changing the written statement based on any new learning that is found or feedback provided.

- Generate a list of possible solutions. Include relevant thoughts, ideas, and educated guesses as well as causes and possible ways to solve it. Then rank the solutions and select the solution that your group is most likely to perceive as the best in terms of meeting success.

- Include what needs to be known and done to solve the identified problems.

- Prioritize the various action steps.

- Consider how the steps impact the possible solutions.

- See if the group is in agreement with the timeline; if not, decide how to reach agreement.

- What resources are available to help (e.g., textbooks, primary/secondary sources, Internet).

- Determine research assignments per team members.

- Establish due dates.

- Determine how your group will present the problem solution and also identify the audience. Usually, in PBL, each group presents their solutions via a team presentation either to the class of other students or to those who are related to the problem.

- Both the process and the results of the learning activity need to be covered. Include the following: problem statement, questions, data gathered, data analysis, reasons for the solution(s) and/or any recommendations reflective of the data analysis.

- A well-stated problem and conclusion.

- The process undertaken by the group in solving the problem, the various options discussed, and the resources used.

- Your solution’s supporting documents, guests, interviews and their purpose to be convincing to your audience.

- In addition, be prepared for any audience comments and questions. Determine who will respond and if your team doesn’t know the answer, admit this and be open to looking into the question at a later date.

- Reflective thinking and transfer of knowledge are important components of PBL. This helps the students be more cognizant of their own learning and teaches them how to ask appropriate questions to address problems that need to be solved. It is important to look at both the individual student and the group effort/delivery throughout the entire process. From here, you can better determine what was learned and how to improve. The students should be asked how they can apply what was learned to a different situation, to their own lives, and to other course projects.

See also: Kirkpatrick Model: Four Levels of Learning Evaluation

I am a professor of Educational Technology. I have worked at several elite universities. I hold a PhD degree from the University of Illinois and a master's degree from Purdue University.

Similar Posts

Cognitive apprenticeship.

Apprenticeship is an ancient idea; skills have been taught by others for centuries. In the past, elders worked alongside their children to teach them how to grow food, wash their clothes, build homes…

Definitions of The Addie Model

What is the ADDIE Model? This article attempts to explain the ADDIE model by providing different definitions. Basically, ADDIE is a conceptual framework. ADDIE is the most commonly used instructional design framework and…

Gamification, What It Is, How It Works, Examples

For many students, the traditional classroom setting can feel like an uninspiring environment. Long lectures, repetitive tasks, and a focus on exams often leave young minds disengaged, craving a more dynamic way to…

Educational Technology: An Overview

Educational technology is a field of study that investigates the process of analyzing, designing, developing, implementing, and evaluating the instructional environment and learning materials in order to improve teaching and learning. It is…

Erikson’s Stages of Psychosocial Development

In 1950, Erik Erikson released his book, Childhood and Society, which outlined his now prominent Theory of Psychosocial Development. His theory comprises of 8 stages that a healthy individual passes through in his…

Planning for Educational Technology Integration

Why seek out educational technology? We know that technology can enhance the teaching and learning process by providing unique opportunities. However, we also know that adoption of educational technology is a highly complex…

Problem-Based Learning

- 1 Understand

- 2 Get Started

- 3 Train Your Peers

- 4 Related Links

What is Problem-Based Learning

Problem-based learning & the classroom, the problem-based learning process, problem-based learning & the common core, project example: a better community, project example: preserving appalachia, project example: make an impact.

All Toolkits

A Learning is Open toolkit written by the New Learning Institute.

Problem-based learning (PBL) challenges students to identify and examine real problems, then work together to address and solve those problems through advocacy and by mobilizing resources. Importantly, every aspect of the problem solving process involves students in real work—work that is a reflection of the range of expertise required to solve issues in the world outside of school.

While problem-based learning can use any type of problem as its basis, the approach described here is deliberately focused on local ones. Local problems allow students to have a meaningful voice, and be instrumental in a process where real, recognizable change results. It also gives students opportunities to source and interact with a variety of local experts.

In many classrooms teachers give students information and then ask them to solve problems at the culmination of a unit. Problem-based learning turns this on its head by challenging students to define the problem before finding the resources necessary to address or solve it. In this approach, teachers are facilitators: they set the context for the problem, ask questions to propel students’ interests and learning forward, help students locate necessary resources and experts, and provide multiple opportunities to critique students’ process and progress. In some cases, the teacher may identify a problem that is connected to existing curriculum; in others the teacher may assign a larger topic and challenge the students to identify a specific problem they are interested in addressing.

This approach is interdisciplinary and provides natural opportunities for integrating a variety of required content areas. Because recognizing and making relationships between content areas is a necessary part of the problem-solving process—as it is in the real world—students are building skills to prepare them for life, work, and civic participation. Problem-based learning gives students a variety of ways to address and tackle a problem. It encourages everyone to contribute and rewards different kinds of success. This builds confidence in students who have not always been successful in school. With the changing needs of today’s world, there is a growing urgency for people who are competent in a range of areas including the ability to apply critical thinking to complex problems, collaborate, network and gather resources, and communicate and persuade others to actively take up a cause.

Problem-based learning builds agency & independence

Although students work collaboratively throughout the process, applying a wide range of skills to new tasks requires them to develop their own specialties that lead to greater confidence and competency. And because the process is student-driven, students are challenged to define the problem, conduct comprehensive research, sort through multiple solutions and present the one that allows them best move forward. This reinforces a sense of self-agency and independence.

Problem-based learning promotes adaptability & flexibility

Investigating and solving problems requires students to work with many different types of people and encounter many unknowns throughout the process. These experiences help students learn to be adaptable and flexible during periods of uncertainty. From an academic standpoint, this flexible mindset is an opportunity for students to develop a range of communication aptitudes and styles. For example, in the beginning research phases, students must gather multiple perspectives and gain a clear understanding of their various audiences. As they move into the later project phases they must develop more nuanced ways to communicate with each audience, from clearly presenting information to persuasion to defending the merits of a new idea.

Problem-based learning is persistent

Educators recognize that when students are working towards a real goal they care about, they show increased investment and willingness to persist through challenges. Problem-based learning requires students to navigate many variables including the diverse personalities on a project team, the decisions and perspectives of stakeholders, challenging and rigorous content, and real world deadlines. Students will experience frustration and failure, but they will learn that working though that by trying new things will be its own reward. And this is a critical lesson that will be carried on into life and work.

Problem-based learning is civically engaged

Because problem-based learning focuses on using local issues as jumping off points it gives students a meaningful context in which to voice their opinions and take the initiative to find solutions. Problems within schools and communities also provide opportunities for students to work directly with stakeholders (i.e. the school principal or a town council member) and experts (i.e. local residents, professionals, and business owners). These local connections make it more likely that students will successfully implement some aspect of their plan and gives students firsthand experience with civic processes.

A problem well put is half solved. – John Dewey

The problem-based learning process described in this toolkit has been refined and tested through the Model Classroom Program, a project of the New Learning Institute. Educators throughout the United States participated in this program by designing, implementing, and documenting projects. The resulting problem-based learning approach provides a clear process and diverse set of tools to support problem-based learning.

The problem-based learning process can help students define problems in new ways, explore multiple perspectives, challenge their thinking, and develop the real-world skills needed for planning and carrying out a project. Beyond this, because the approach emphasizes local and community-based issues, this process develops student drive and motivation as they work towards a tangible end result with the potential to impact their community.

Make it Real

The world is full of unsolved problems and opportunities just waiting to be addressed. The Make It Real phase is about identifying a real problem within the local community, then conducting further investigation to define the problem.

Identify what you do and don’t know about the problem Brainstorm what is known about the problem. What do you know about it at the local level? Is this problem globally relevant? How? What questions would you investigate further?

Discover the problem’s root causes and impacts on the community While it’s easy to find a problem, it’s much harder to understand it. Investigate how the problem impacts different people and places. As a result of these investigations, students will gain a clearer understanding of the problem.

Make it Relevant

Problems are everywhere, but it can often be difficult to convince people that a specific problem should matter to them. The word relevant is from the Latin root meaning “to raise” or “to lift up.” To Make It Relevant, elevate the problem so that people in the community and beyond will take interest and become invested in its resolution. Make important connections in order to begin a plan to address the problem.

Field Studies

Collect as much information as possible on the problem. Conduct the kind of research experts in the field—scientists and historians—conduct. While online and library research is a good starting point, it’s important that students get out into the real world to conduct their own original research! This includes using methods such as surveys, interviews, photo and video documentation, collection of evidence (such as science related activities), and working with a variety of experts and viewpoints.

Develop an action-plan Have students analyze their field studies data and create charts, graphs, and other visual representations to understand their findings. After analyzing, students will have the information needed to develop a plan of action. Importantly, they’ll need to consider how best to meet the needs of all stakeholders, which will include a diverse community such as local businesses, community members, experts, and even the natural world.

Make an Impact

Make An Impact with a creative implementation based on the best research-supported ideas. In many cases, making an impact is about solving the problem. Sometimes it’s about addressing it, making representations to stakeholders, or presenting a possible solution for future implementation. At the most rigorous level, students will implement a project that has lasting impact on their community.

Put your plan into action See the hard work of researching and analyzing the problem pay off as students begin implementing their plans. In so doing, they’ll act as part of a team creating a product to share. Depending on the problem, purpose, and audience, their products might be anything from a website to an art installation to the planning of a community-wide event.

Share your findings and make an impact Share results with important stakeholders and the larger community. Depending on the project, this effort may include awareness campaigns, a persuasive presentation to stakeholders, an action-oriented campaign, a community-wide event, or a re-designed program. In many cases this “final” act leads to the beginning of another project!

With the Common Core implementation, teachers have found different strategies and resources to help align their practice to the standards. Indeed, many schools and districts have discovered a variety of solutions. When considering Common Core alignment, the opportunity presented by methods like problem-based learning hinges on a belief in the art of teaching and the importance of developing students’ passion and love of learning. In short, with the ultimate goal of making students college-, career-, and life-ready, it’s essential that educators put students in the driver’s seat to collaboratively solve real problems.

The Common Core ELA standards draw a portrait of a college- and career-ready student. This portrait includes characteristics such as independence, the ability to adapt communication to different audiences and purposes, the ability to comprehend and critique, appreciation for the value of evidence (when reading and when creating their own work), and the capability to make strategic use of digital media. Developing creative solutions to complex problems provides students with multiple opportunities to develop all of these skills.

Independence

Students are challenged to define the problem and conduct comprehensive research, then present solutions. This student-driven process requires students to find multiple answers and think critically about the best way to act, ultimately building confidence and independence.

Adapting Communication to Different Audiences and Purposes

In the initial research phases, students must gather multiple perspectives and gain a clear understanding of who those audiences are. As they move into the later project phases, they must communicate in a variety of ways (including informative and persuasive methods) to reach diverse audiences.

Comprehending and Critiquing

In examining multiple perspectives, students must summarize various viewpoints, addressing their strengths and critiquing their weaknesses. Furthermore, as students develop solutions they must analyze each idea for its potential success, which compels them to critique their own work in addition to the work of others.

Valuing Evidence

Collecting evidence is essential to the process, whether through visual documentation of a problem, uncovering key facts, or collecting narratives from the community.

Strategic Use of Digital Media

The use of digital media is naturally integrated throughout the entire process. The problem-based learning approach not only builds the specific 21st century skills called for by the Common Core, it also embraces practices supported by hundreds of years of educational theory. This is not the next new thing – problem-based learning is one example of how vetted best educational practices will meet the needs of a future economy and society; and, more immediately, the new Common Core Standards.

Language Arts

The Key Design Considerations for the English Language Arts standards describe an integrated literacy model in which all communication processes are closely connected. Likewise, the problem-based learning approach expects students to read, write, and speak about the issue (whether through interviews or speeches) in a variety of ways (expository, persuasive). In addition, the Key Design Considerations describe how literacy is a shared responsibility across subject areas. Because problem-based learning is rooted in real issues, these naturally connect to science content areas (environmental sciences, engineering and design, innovation and invention), social studies (community history, geography/land forms), math (including operations such as graphing, statistics, economics, and mathematical modeling), and art. As part of this interdisciplinary model, problem-based learning follows a process that touches on key ELA skill areas including research, a variety of writing styles and formats (both reading and writing in these formats), publishing, and integration of digital media.

It’s also important to note that the Common Core calls for an increase in informational and nonfiction text. This objective is easily met through examining real problems. Quite simply, informational and nonfiction text is everywhere – in newspaper articles, public surveys, government documents, etc. Very often, when reading out of context, many students struggle to work through and comprehend these types of complex texts. Because problem-based learning authentically integrates a real purpose with reading informational text, students work harder to comprehend and apply their reading.

Note: Each project has the potential to meet many additional standards. The standards outlined here are only a sampling of those addressed by this approach.

Reading Standards

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.R.6 Assess how point of view or purpose shapes the content and style of a text. In the early phases of problem-based learning, students investigate the topic by reading a range of informational and persuasive texts, and by talking to a variety of experts and community members. As an essential component to these investigations on multiple perspectives, students must be able to understand the purpose of the text, the intended audience, and the individual’s position on the issue (if applicable).

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.R.7 Integrate and evaluate content presented in diverse media and formats, including visually and quantitatively, as well as in words. As students consider multiple perspectives on their identified problem, they naturally will seek a wide range of print materials, media resources (videos, presentations), and formats (research studies, opinion pieces). Comparing and contrasting the viewpoints of these various texts will help students shape a more holistic view of the problem.

Writing Standards

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.W.1 Write arguments to support claims in an analysis of substantive topics or texts using valid reasoning and relevant and sufficient evidence. As students analyze the problem, multiple opportunities for persuasive writing emerge. In the early project phases, students might summarize their perspective on the problem using key evidence from a variety of research (online, community polling, and discussions with experts). In the later project phases, students might develop a proposal or presentation to persuade others to change personal habits or consider a larger change in the community.

Speaking & Listening Standards

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.SL.1 Prepare for and participate effectively in a range of conversations and collaborations with diverse partners, building on others’ ideas and expressing their own clearly and persuasively. Multiple perspectives are an essential component to any problem-based project. As students investigate, they must seek a wide range of opinions and personal stories on the issues. Furthermore, this process is collaborative. Students must trust and work with each other, they must trust and work with key experts, and, in some cases, they must convince others to collaborate with them around a shared purpose or cause.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.SL.5 Make strategic use of digital media and visual displays of data to express information and enhance understanding of presentations. Because each problem-based project requires students to analyze information, share their findings with others, and collaborate on a variety of levels, digital media is naturally integrated into these tasks. Students might create charts, graphs, or other illustrative/photo/video displays to communicate their research results. Students might use a variety of digital formats including graphic posters, video public service announcements (PSAs), and digital presentations to mobilize the community to their cause. Inherent to these processes is special consideration of how images, videos, and other media support key ideas and key evidence and further the effectiveness of their presentation on the intended audience.

Mathematics

Simply put, math is problem solving. Problem-based learning provides multiple opportunities for students to apply and develop their understanding of various mathematical concepts within real contexts. Through the various stages of problem-based learning, students engage in the same dispositions encouraged by the Standards for Mathematical Practice

CCSS.Math.Practice.MP1 Make sense of problems and persevere in solving them. Problem-based learning is all about problem solving. An essential first step is understanding the problem as deeply as possible, rather than rushing to solve it. This is a process that takes time and perseverance, both individually and in collaborative student groups.

CCSS.Math.Practice.MP3 Construct viable arguments and critique the reasoning of others. As students understand and deconstruct a problem, they must begin to form solutions. As part of this process, they must have evidence (including visual and mathematical evidence) to support their position. They must also understand other perspectives to solving the problem, and they must be prepared to critique those other perspectives based on verbal and mathematical reasoning.

CCSS.Math.Practice.MP4 Model with mathematics. Throughout the process, students must analyze information and data using a variety of mathematical models. These range from charts and graphs to 3-D modeling used in science or engineering projects.

CCSS.Math.Practice.MP5 Use appropriate tools strategically. According to the Common Core Math Practices standard, “Mathematically proficient students consider the available tools when solving a mathematical problem. These tools might include pencil and paper, concrete models, a ruler, a protractor, a calculator, a spreadsheet, a computer algebra system, a statistical package, or dynamic geometry software.” In addition to providing opportunities to use these tools, problem-based learning asks students to make effective use of digital and mobile media as they collect information, document the issue, share their findings, and mobilize others to their cause.

School Name | Big Horn Elementary Location | Big Horn, Wyoming Total Time | 1 year Subjects | English Language Arts, Social Studies, Math, Science Grade Level | 3rd Grade Number of Participants | 40 students in two classrooms

Students informed the school about the importance of recycling, developed systems to improve recycling options and implemented a school-wide recycling program that involved all students, other teachers, school principals, school custodians, and the county recycling center.

While investigating their local county history, students were challenged to recognize their role in the community and ultimately realize the importance of stewardship for the county’s land, history and culture. Students began by researching their local history through many first hand experiences including museum visits, local resident interviews and visits to places representing the current culture.

Challenged to find ways to make “A Better Community”, students chose to investigate recycling.

They conducted hands-on research to determine the need for a recycling program through a school survey, town trash pickup and visit to the local Landfill and Recycling Center.

Students then developed a proposal for a school-wide recycling program, interviewed the principal to address their concerns and began to carry out their plan.

Students designed recycling bins for each classroom and worked with school janitors to develop a plan for collection.

Students visited each classroom to distribute the recycling bins and describe how to use them. Students developed a schedule for collecting bins and sorting materials. The program continues beyond the initial school-year; students continue to expand their efforts.

School Name | Bates Middle School Location | Danville, Kentucky Total Time | 8 weeks Subjects | English Language Arts Grade Level | 6th Grade Number of Participants |25 students

Students created Project Playhouse, a live production for the local community. Audience members included community members, parents, and other students. In addition, students designed a quilt sharing Appalachian history, and recorded their work on a community website.

Appalachia has a rich culture full of unique traditions and an impressive heritage, yet many negative stereotypes persist. 6th grade students brainstormed existing stereotypes and their consequences on the community.

Students discussions led them to realize that, in their region, stereotypes were preventing people from overcoming adversity. They set about to conduct further research demonstrating the strengths of Appalachian heritage.

Students investigated Appalachian culture by working with local experts like Tammy Horn, professor at Eastern Kentucky University and specialist in Appalachian cultural traditions; taking a field trip to Logan Hubble Park to explore the natural region; talking with a “coon” hunter and other local Appalachians including quilters, cooks, artists, and writers.

Students developed a plan to curate an exhibition and live production for the local community. Finally, students connected virtually with museum expert Rebecca Kasemeyer, Associate Director of Education at the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery to discuss exhibition design.

For their final projects students produced a series of works exhibiting Appalachian life, work, play and community structure including a quilt, a theatrical performance and a website.

Students invited the community to view their exhibit and theatrical performance.

School Name | Northwestern High School Location | Rock Hill, South Carolina Total Time | One Semester Subjects | Engineering Grade Level | High School Number of Participants | 20 students

Engineering teacher Bryan Coburn presented a scenario to his students inspired by the community’s very real drought, a drought so bad that cars could only be washed on specific days. Students identified and examined environmental issues related to water scarcity in their community.

Based on initial brainstorming, students divided into teams based on specific problems related to a water shortage. These included topics like watering gardens and lawns, watering cars, drinking water to name a few.

Based on their topic, students conducted online research on existing solutions to their specific problem.

Students analyzed their research to develop their own prototypes and plans for addressing the problem. Throughout the planning phase students received peer and teacher feedback on the viability of their prototypes, resulting in many edits before final designs were selected for creation.

Students created online portfolios showcasing their research, 3D designs, and multimedia presentations marketing their designs. Student portfolios included documentation of each stage of the design process, a design brief, decision matrix, a prototype using Autodesk Inventor 3D professional modeling tool, and a final presentation.

Students shared their presentations and portfolios in a public forum, pitching their proposed solution to a review committee consisting of local engineers from the community, the city water manager and the school principal.

Plan Your PBL Experience

Resources to help you plan.

Problem-based learning projects are inspired by students’ real world experiences and the pressing issues and concerns they want to address. Problem-based learning projects benefit teachers by increasing student motivation and engagement, while deepening knowledge and improving essential skills. In spite of the inherent value problem-based learning brings to any educational setting, planning a large project can be an overwhelming task.

Through the New Learning Institute’s Model Classroom, a range of problem-based learning planning tools have been developed and tested in a variety of educational settings. These tools make the planning process more manageable by supporting teachers in establishing the context and/or problem for a project, planning for and procuring the necessary resources for a real-world project (including community organizations, expert involvement, and tools needed for communicating, creating and sharing), and facilitating students through the project phases.

Here are some initial considerations when planning a problem-based learning project. (More detailed tips and planning tools follow.) These questions can help you determine where to begin your project planning. Once you have a clear idea, the problem-based learning planning tools will guide you through the process.

Are you starting from the curriculum? It’s probably tempting to jump in and define a problem for students based on the unit of study. And time constraints may make a teacher-defined problem necessary. If time permits, a problem-based learning project will be more successful if time is built-in for students to define a problem they’d like to address. Do this by building in topic exploration time, and then challenging students to define a problem based on their findings. Including this extra time will allow students to develop their own interests and questions about the topic, deepening engagement and ensuring that students are investigating a problem they’re invested in—all while covering curriculum requirements.

Are you starting from student interest? Perhaps your students want to solve a problem in the school, such as bullying or lack of recycling. Perhaps they’re concerned about a larger community problem, such as a contested piece of parkland that is up for development or a pollution problem in your local waterways. Starting with student interest can help ensure students’ investment and motivation. However, this starting point provides less direct navigation than existing projects or curriculum materials. When taking on a project of this nature, be sure to identify natural intersections with your curriculum. It also helps to enlist community or expert support.

Start Small – Focus on Practices as Entry Points

If you’re new to problem-based learning it makes sense to start small. Many teachers new to this approach report that starting with the smaller practices—such as integrating research methods or having students define a specific problem within a unit of study—ultimately sets the stage for larger projects and more easily leads them to implement a problem-based learning project.

Opportunities to address and solve problems are everywhere. Just look in your own backyard or schoolyard. Better yet, ask students to identify problems within the school community or based on a topic of interest within a unit of study. As you progress through the project, find natural opportunities for research and problem solving by working with the people who are affected by the issue and invested in solving it. Finally, make sure students share their work with an authentic audience who cares about the problem and its resolution.

Be Honest About Project Constraints

When you’re new to problem-based learning, the most important consideration is your project constraints. For example, perhaps you’re required to cover a designated set of standards and content. Or perhaps you have limited time for this project experience. Whatever the constraints, determine them in advance then plan backwards to determine the length and depth of your project.

Identify Intersections With Your Curriculum

Problem-based learning projects are interdisciplinary and have the ability to meet a range of standards. Identify where these intersections naturally occur with the topic students have selected, then design some activities or project requirements to ensure these content areas are covered.

Turn Limitations Into Opportunities

Many educators work in schools with pre-defined curriculum or schedule constraints that make implementing larger projects difficult. In these cases, it may help to find small windows of opportunity during the school day or after school to implement problem-based learning. For example, some teachers implement problem-based learning in special subject courses which have a more flexible curriculum. Others host afterschool “Genius Hour” programs that challenge students to explore and investigate their interests. Whatever opportunity you find, make the work highly visible to staff and parents. Make it an intention to get the school community exploring and designing possibilities of integrating these practices more holistically.

Take Risks and Model Perseverance

The problem-based learning process is messy and full of opportunities to fail, just like real life and real jobs. Many educators share that this is incredibly difficult for their students and themselves. Despite the initial letdown that comes with small failures, it’s important that students see the value in learning from failure and persevering through these challenges. Model risk taking for your students and when you make a mistake or face a challenge, welcome it with open arms by demonstrating what you’ve learned and what you’ll do differently next time around. Let students know that it’s okay to make mistakes; that mistakes are a welcome opportunity to learn and try something new.

Be Less Helpful

A key to building problem-solving and critical thinking capacities is to be less helpful. Let students figure things out on their own. In classroom implementation, teachers repeatedly share that handing over control to the students and “being less helpful” makes for a big mindshift. This shift is often described as becoming a facilitator, which means knowing when to stand back and knowing when to step-in and offer extra support.

Be Flexible

Recognize that there is no one-size-fits-all answer to any problem. Understanding this and being able to identify unique challenges will help students understand that an initial failure is just a bump in the road. Being flexible also helps students focus on the importance of process over product.

Experts are Everywhere

Experts are everywhere; their differing perspectives and expertise help bring learning to life. But think outside the box about who experts are and integrate multiple opportunities for their involvement. Parents and community members who are not often thought of as experts can speak to life, work, and lived historical experiences. Beyond that, the people usually thought of as experts—researchers, scientists, museum professionals, business professionals, university professors—are more available than many teachers think. It’s often just a matter of asking. And don’t take sole responsibility for finding experts! Seek your students’ help in identifying and securing expert or community support. And when trying to locate experts, don’t forget: students can also be experts.

Maintain a List of Your Support Networks

Some schools have brought the practice of working with the community and outside experts to scale by building databases of parent and community expertise and their interest in working with students. See if a school administrative assistant, student intern, or parent helper can take the lead in developing and maintaining this list for your school community.

Encourage Original Research

Online research is often a great starting point. It can be a way to identify a knowledge base, locate experts, and even find interest-based communities for the topic being approached. While online research is literally right at students’ fingertips, make sure your students spend time offline as well. Original research methods include student-conducted surveys, interviewing experts, and working alongside experts in the field.

This Learning is Open toolkit includes a number of tools and resources that may be helpful as you plan and reflect on your project.

Brainstorming Project Details (Google Presentation) This tool is designed to aid teachers as they brainstorm a project from a variety of starting-points. It’s a helpful tool for independent brainstorming, and would also make a useful workshop tool for teachers who are designing problem-based learning experiences.

Guide to Writing a Problem Statement (PDF) You’ve got to start somewhere. Finding—and defining—a problem is a great place to begin. This guide is a useful tool for teachers and students alike. It will walk you through the process of identifying a problem by providing inspiration on where to look. Then it will support you through the process of defining that problem clearly.

Project Planning Templates (PDF) Need a place to plan out each project phase? Use this project planner to record your ideas in one place. This template is great used alone or in tandem with the other problem-based learning tools.

Ladder of Real World Learning Experiences (PDF) Want to determine if your project is “real” enough? This ladder can be used to help teachers assess their project design based on the real world nature of the project’s learning context, type of activities, and the application of digital tools.

Digital Toolkit (Google Doc) This toolkit was developed in collaboration with teachers and continues to be a community-edited document. The toolkit provides extensive information on digital tools that can be used for planning, brainstorming, collaborating, creating, and sharing work.

Assessing student learning is a crucial part of any dynamic, nonlinear problem-based learning project. Problem-based projects have many parts to them. It’s important to understand each project as a whole as well as each individual component. This section of the toolkit will help you understand problem-based learning assessments and help you develop assessment tools for your problem-based learning experiences.

Because the subject of assessments is so complex, it may be helpful to define how it is approached here.

Portfolio-based Assessment

Each phase of problem-based learning has important tasks and outcomes associated with it. Assessing each phase of the process allows students to receive on-time feedback about their process and associated products and gives them the opportunity to refine and revise their work throughout the process.

Feedback-based Assessment

Problem-based learning emphasizes collaboration with classmates and a range of experts. Assessment should include multiple opportunities for peer feedback, teacher feedback, and expert feedback.

Assessment as a System of Interrelated Feedback Tools

These tools may include rubrics, checklists, observation, portfolios, or quizzes. Whatever the matrix of carefully selected tools, they should optimize the feedback that students receive about what and how they are learning and growing.

Assessment Tools

One way to approach developing assessment tools for your students’ specific problem-based learning project is to deconstruct the learning experience into various categories. Together, these categories make up a simple system through which students may receive feedback on their learning.

Assessing Process

Many students and teachers alike have been conditioned to emphasize and evaluate the end product. While problem-based learning projects often result in impressive end products, it’s important to emphasize each stage of the process with students.

Each phase of problem-based learning process emphasizes important skills, from research and data gathering in the early phases to problem solving, collaboration, and persuasion in the later phases. There are many opportunities to assess student understanding and skill throughout the process. The tools here provide many methods for students to self-assess their process, get feedback from peers, and get feedback from their teachers and other adults.

The Process Portfolio Tool (PDF) provides a place for students to collect their work, define their problem and goals, and reflect throughout the process. Use this as a self-assessment tool, as well as a place to organize the materials for student portfolios.

Driving & Reflection Questioning Guidelines (PDF) is a simple tool for teachers who are integrating problem-based learning into the learning process. The tool highlights the two types of questions teachers/facilitators should consider with students: driving questions and reflection questions. Driving questions push students in their thinking, challenging them to build upon ideas and try new ways to solve problems. Reflection questions ask students to reflect on a process phase once it’s complete, challenging them to think about how they think.

The Peer Feedback Guidelines (PDF) will help students frame how they provide feedback to their peers. The guide includes tips on how and when to use these guidelines in different types of forums (i.e. whole group, gallery-style, and peer-to-peer).

The Buck Institute has also developed a series of rubrics that address various project phases. Their Collaboration Rubric (PDF) can help students be better teammates. (Being an effective teammate is critical to the problem-based learning process.) Their Presentation Rubric (PDF) can help students, adult mentors, and outside experts evaluate final presentations. Final presentations are often one of the most exciting parts of a project.

Assessing Subject Matter and Content

A common concern that emerges in any problem-based learning design is whether projects are able to meet all required subject matter content targets. Because many students are required to learn specific content, there is often tension around the student-directed nature of problem-based learning. While teachers acknowledge that students go deeper into specific content during problem-based learning experiences, teachers also want to ensure that their students are meeting all content goals.

Many teachers in the New Learning Institute’s Model Classroom Program addressed this issue directly by carefully examining their curriculum requirements throughout the planning and implementation phases. Begin by planning activities and real world explorations that address core content. As the project evolves, revisit content standards to mark off and record additional standards met and create a contingency plan for those that have not been addressed.

The Buck Institute’s Rubric for Rubrics (DOC) is an excellent source for designing a rubric to fit your needs. Developing a rubric can be the most simple and effective tool for planning a project around required content targets.

Blended learning is another emerging trend that educators are moving towards as a way to both address individualized skill needs and to create space for real world project strategies, like problem-based learning. In these learning environments, students address skill acquisition through blended experiences and then apply their skills through projects and other real world applications. To learn more about blended models, visit Blend My Learning .

Assessing Mindsets and Skills

In addition to assessing process and subject matter content, it may be helpful to consider the other important mindsets and skills that the problem-based learning project experience fosters. These include persistence, problem solving, collaboration, and adaptability. While problem-based learning supports the development of a large suite of 21st century mindsets and skills, it may be helpful to focus assessments on one or two issues that are most relevant. Some helpful tools may include:

The Buck Institute offers rubrics for Critical Thinking (PDF), Collaboration (PDF), and Creativity and Innovation (PDF) that are aligned to the Common Core State Standards. These can be used as is or tailored to your specific needs.

The Character Growth Card (PDF) from the CharacterLab at Kipp is designed for school assessments more than it is for project assessment, but the list of skills and character traits are relevant to design thinking. With the inclusion of a more relevant, effective scale, these can easily be turned into a rubric, especially when paired with the Buck Institute’s Rubric for Rubrics tool.

Host a Teacher Workshop

Teachers are instrumental in sharing and spreading best practices and innovative strategies to other teachers. Once you’re confident in your conceptual and practical grasp of problem-based learning, share your knowledge and expertise with others.

The downloadable presentation decks below (PowerPoint) are adaptable tools for helping you spread the word to other educators. The presentations vary in length and depth. A 90-minute presentation introduces problem-based learning and provides a hands-on opportunity to complete an activity. The half-day and full day presentations provide in-depth opportunities to explore projects and consider their classroom applications. While this series is structured in a way that each presentation builds on the previous one, each one can also be used individually as appropriate. Each is designed to be interactive and participatory.

Getting Started with Problem-based Learning (PPT) A presentation deck for introducing educators to the Learning is Open problem-based learning process during a 90-minute peer workshop.

Dig Deeper with Problem-based Learning – Half-day (PPT) A presentation deck for training educators on the Learning is Open problem-based learning process during a half-day peer workshop.

Dig Deeper with Problem-based Learning – Full day (PPT) A presentation deck for training educators on the Learning is Open problem-based learning process during a full day peer workshop.

Related Links

Problem-based learning: detailed case studies from the model classroom.

For three years, the New Learning Institute’s Model Classroom program worked with teachers to design and implement projects. This report details the work and provides extensive case studies.

Title: Model Classroom: 3-Year Report (PDF) Type: PDF Source: New Learning Institute

Setting up Learning Experiences Using Real Problems

This New York Times Learning Blog article explores how projects can be set-up with real problems, providing many examples and suggestions for this approach.

Title: “ Guest Lesson | For Authentic Learning Start with Real Problems ” Type: Article Source: Suzie Boss. New York Times Learning Blog

Guest Lesson: Recycling as a Focus for Project-based Learning

There are many ways to set-up a project with a real world problem. This article describes the problem of recycling, providing multiple examples of student projects addressing the issue.

Title: “ Guest Lesson | Recycling as a Focus for Project-Based Learning ” Type: Article Source: Suzie Boss. New York Times Learning Blog

Problem-based Learning: Professional Development Inspires Classroom Project

This video features how the Model Classroom professional development workshop model worked in practice, challenging teachers to collaboratively problem-solve using real world places and experts. It also shows how one workshop participant used her experience to design a yearlong problem-based learning project for first-graders called the “Streamkeepers Project.”

Title: Mission Possible: the Model Classroom Type: Video Source: New Learning Institute

Problem-based Learning in an Engineering Class: Solutions to a Water Shortage

Engineering teacher Bryan Coburn used the problem of a local water shortage to inspire his students to conduct research and design solutions.

Title: “ National Project Aims to Inspire the Model Classroom ” Type: Article Source: eSchool News

Making Project-based Learning More Meaningful

This article provides great tips on how to design projects to be relevant and purposeful for students. While it addresses the larger umbrella of project-based learning, the suggestions and tips provided apply to problem-based learning.

Title: “ How to Reinvent Project-Based Learning to Make it More Meaningful ” Type: Article Source: KQED Mindshift

PBL Downloads

Guide to Writing a Problem Statement (PDF)

A walk-through guide for identifying and defining a problem.

Project Planning Templates (PDF)

A planning template for standalone use or to be used along with other problem-based learning tools.

Process Portfolio Tool (PDF)

A self-assessment tool to support students as they collect their work, define their problem and goals, and make reflections throughout the process.

More PBL Downloads

Getting Started with Problem-based Learning (PPT)

A presentation deck for introducing educators to the Project MASH problem-based learning process during a 90-minute peer workshop.

Dig Deeper with Problem-based Learning – Half-day (PPT)

A presentation deck for training educators on the PBL process during a half-day peer workshop.

Dig Deeper with Problem-based Learning – Full day (PPT)

A presentation deck for training educators on the PBL process during a full day peer workshop.

Center for Teaching Innovation

Resource library.

- Establishing Community Agreements and Classroom Norms

- Sample group work rubric

- Problem-Based Learning Clearinghouse of Activities, University of Delaware

Problem-Based Learning

Problem-based learning (PBL) is a student-centered approach in which students learn about a subject by working in groups to solve an open-ended problem. This problem is what drives the motivation and the learning.

Why Use Problem-Based Learning?

Nilson (2010) lists the following learning outcomes that are associated with PBL. A well-designed PBL project provides students with the opportunity to develop skills related to:

- Working in teams.

- Managing projects and holding leadership roles.

- Oral and written communication.

- Self-awareness and evaluation of group processes.

- Working independently.

- Critical thinking and analysis.

- Explaining concepts.

- Self-directed learning.

- Applying course content to real-world examples.

- Researching and information literacy.

- Problem solving across disciplines.

Considerations for Using Problem-Based Learning

Rather than teaching relevant material and subsequently having students apply the knowledge to solve problems, the problem is presented first. PBL assignments can be short, or they can be more involved and take a whole semester. PBL is often group-oriented, so it is beneficial to set aside classroom time to prepare students to work in groups and to allow them to engage in their PBL project.

Students generally must:

- Examine and define the problem.

- Explore what they already know about underlying issues related to it.

- Determine what they need to learn and where they can acquire the information and tools necessary to solve the problem.

- Evaluate possible ways to solve the problem.

- Solve the problem.

- Report on their findings.

Getting Started with Problem-Based Learning

- Articulate the learning outcomes of the project. What do you want students to know or be able to do as a result of participating in the assignment?

- Create the problem. Ideally, this will be a real-world situation that resembles something students may encounter in their future careers or lives. Cases are often the basis of PBL activities. Previously developed PBL activities can be found online through the University of Delaware’s PBL Clearinghouse of Activities .

- Establish ground rules at the beginning to prepare students to work effectively in groups.

- Introduce students to group processes and do some warm up exercises to allow them to practice assessing both their own work and that of their peers.

- Consider having students take on different roles or divide up the work up amongst themselves. Alternatively, the project might require students to assume various perspectives, such as those of government officials, local business owners, etc.

- Establish how you will evaluate and assess the assignment. Consider making the self and peer assessments a part of the assignment grade.

Nilson, L. B. (2010). Teaching at its best: A research-based resource for college instructors (2nd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Illinois Online

- Illinois Remote

- TA Resources

- Teaching Consultation

- Teaching Portfolio Program

- Grad Academy for College Teaching

- Faculty Events

- The Art of Teaching

- 2022 Illinois Summer Teaching Institute

- Large Classes

- Leading Discussions

- Laboratory Classes

- Lecture-Based Classes

- Planning a Class Session

- Questioning Strategies

- Classroom Assessment Techniques (CATs)

- Problem-Based Learning (PBL)

- The Case Method

- Community-Based Learning: Service Learning

- Group Learning

- Just-in-Time Teaching

- Creating a Syllabus

- Motivating Students

- Dealing With Cheating

- Discouraging & Detecting Plagiarism

- Diversity & Creating an Inclusive Classroom

- Harassment & Discrimination

- Professional Conduct

- Foundations of Good Teaching

- Student Engagement

- Assessment Strategies

- Course Design

- Student Resources

- Teaching Tips

- Graduate Teacher Certificate

- Certificate in Foundations of Teaching

- Teacher Scholar Certificate

- Certificate in Technology-Enhanced Teaching

- Master Course in Online Teaching (MCOT)

- 2022 Celebration of College Teaching

- 2023 Celebration of College Teaching

- Hybrid Teaching and Learning Certificate

- 2024 Celebration of College Teaching

- Classroom Observation Etiquette

- Teaching Philosophy Statement

- Pedagogical Literature Review

- Scholarship of Teaching and Learning

- Instructor Stories

- Podcast: Teach Talk Listen Learn

- Universal Design for Learning

Sign-Up to receive Teaching and Learning news and events

Problem-Based Learning (PBL) is a teaching method in which complex real-world problems are used as the vehicle to promote student learning of concepts and principles as opposed to direct presentation of facts and concepts. In addition to course content, PBL can promote the development of critical thinking skills, problem-solving abilities, and communication skills. It can also provide opportunities for working in groups, finding and evaluating research materials, and life-long learning (Duch et al, 2001).

PBL can be incorporated into any learning situation. In the strictest definition of PBL, the approach is used over the entire semester as the primary method of teaching. However, broader definitions and uses range from including PBL in lab and design classes, to using it simply to start a single discussion. PBL can also be used to create assessment items. The main thread connecting these various uses is the real-world problem.

Any subject area can be adapted to PBL with a little creativity. While the core problems will vary among disciplines, there are some characteristics of good PBL problems that transcend fields (Duch, Groh, and Allen, 2001):

- The problem must motivate students to seek out a deeper understanding of concepts.

- The problem should require students to make reasoned decisions and to defend them.

- The problem should incorporate the content objectives in such a way as to connect it to previous courses/knowledge.

- If used for a group project, the problem needs a level of complexity to ensure that the students must work together to solve it.

- If used for a multistage project, the initial steps of the problem should be open-ended and engaging to draw students into the problem.

The problems can come from a variety of sources: newspapers, magazines, journals, books, textbooks, and television/ movies. Some are in such form that they can be used with little editing; however, others need to be rewritten to be of use. The following guidelines from The Power of Problem-Based Learning (Duch et al, 2001) are written for creating PBL problems for a class centered around the method; however, the general ideas can be applied in simpler uses of PBL:

- Choose a central idea, concept, or principle that is always taught in a given course, and then think of a typical end-of-chapter problem, assignment, or homework that is usually assigned to students to help them learn that concept. List the learning objectives that students should meet when they work through the problem.

- Think of a real-world context for the concept under consideration. Develop a storytelling aspect to an end-of-chapter problem, or research an actual case that can be adapted, adding some motivation for students to solve the problem. More complex problems will challenge students to go beyond simple plug-and-chug to solve it. Look at magazines, newspapers, and articles for ideas on the story line. Some PBL practitioners talk to professionals in the field, searching for ideas of realistic applications of the concept being taught.

- What will the first page (or stage) look like? What open-ended questions can be asked? What learning issues will be identified?

- How will the problem be structured?

- How long will the problem be? How many class periods will it take to complete?

- Will students be given information in subsequent pages (or stages) as they work through the problem?

- What resources will the students need?

- What end product will the students produce at the completion of the problem?

- Write a teacher's guide detailing the instructional plans on using the problem in the course. If the course is a medium- to large-size class, a combination of mini-lectures, whole-class discussions, and small group work with regular reporting may be necessary. The teacher's guide can indicate plans or options for cycling through the pages of the problem interspersing the various modes of learning.

- The final step is to identify key resources for students. Students need to learn to identify and utilize learning resources on their own, but it can be helpful if the instructor indicates a few good sources to get them started. Many students will want to limit their research to the Internet, so it will be important to guide them toward the library as well.

The method for distributing a PBL problem falls under three closely related teaching techniques: case studies, role-plays, and simulations. Case studies are presented to students in written form. Role-plays have students improvise scenes based on character descriptions given. Today, simulations often involve computer-based programs. Regardless of which technique is used, the heart of the method remains the same: the real-world problem.

Where can I learn more?

- PBL through the Institute for Transforming Undergraduate Education at the University of Delaware

- Duch, B. J., Groh, S. E, & Allen, D. E. (Eds.). (2001). The power of problem-based learning . Sterling, VA: Stylus.

- Grasha, A. F. (1996). Teaching with style: A practical guide to enhancing learning by understanding teaching and learning styles. Pittsburgh: Alliance Publishers.

Center for Innovation in Teaching & Learning

249 Armory Building 505 East Armory Avenue Champaign, IL 61820

217 333-1462

Email: [email protected]

Office of the Provost

- My presentations

Auth with social network:

Download presentation

We think you have liked this presentation. If you wish to download it, please recommend it to your friends in any social system. Share buttons are a little bit lower. Thank you!

Presentation is loading. Please wait.

Problem Based Learning

Published by Clara de Boer Modified over 5 years ago

Similar presentations

Presentation on theme: "Problem Based Learning"— Presentation transcript:

Problem-Based Learning (PBL)

Understanding by Design Stage 3

Office of Faculty Development

SUNITA RAI PRINCIPAL KV AJNI

Assessing Student Learning

Science Inquiry Minds-on Hands-on.

Big Ideas and Problem Solving in Junior Math Instruction

Technology and Motivation

ENGLISH LANGUAGE ARTS AND READING K-5 Curriculum Overview.

Interstate New Teacher Assessment and Support Consortium (INTASC)

A Framework for Inquiry-Based Instruction through

11/07/06John Savery-University of Akron1 Problem-Based Learning:An Overview John Savery The University of Akron.

1 Linked Learning Summer Institute 2015 Planning Integrated Units.

Four Basic Principles to Follow: Test what was taught. Test what was taught. Test in a way that reflects way in which it was taught. Test in a way that.

Instructional Design for Language Learning Software Constructivist approach: creative use of software Language Learning -contextualized: not isolated chunks.

Problem-Based Learning. Process of PBL Students confront a problem. In groups, students organize prior knowledge and attempt to identify the nature of.

Project Based Learning What, Why & How. Objectives for Today Have you experience the beginning of a project (= Making your own project) Analyze your experience,

Understanding Problem-Based Learning. How can I get my students to think? Asked by Barbara Duch This is a question asked by many faculty, regardless of.

EDN:204– Learning Process 30th August, 2010 B.Ed II(S) Sci Topics: Cognitive views of Learning.

Morea Christenson Jordan Milliman Trent Comer Barbara Twohy Jessica HuberAlli Wright AJ LeCompte Instructional Model Problem Based Learning.

About project

© 2024 SlidePlayer.com Inc. All rights reserved.

- Our Mission

Guiding Students to Harness Mistakes for Learning

With practice and an eventual shift in mindset, students can understand that mistakes are fundamental to how we learn.

As students begin to build the skills they desire, such as solving early puzzles or making circles instead of scribbles, they often experience the frustration of not doing it “right.” Even when we assure them that there is no right or wrong when starting out, or that with practice they'll get better and better, many still suffer distress.

Students often have misunderstandings about mistakes. They may think that speed in comprehension represents knowledge or that mistakes are a sign of lesser intelligence.

For many students in school, their greatest fear is to make a mistake in front of their classmates and suffer a self-imposed humiliation. Let them know that all their classmates have the same fears. Help them understand that setbacks provide opportunities for them to revise their brains’ inaccurate memory circuits, which, if uncorrected, could impede future understanding. Working through periods of confusion strengthens the correct durable networks their brains ultimately construct. Allowing students to make mistakes and correct them with a positive attitude builds their understanding and solidifies accurate learning connections.

.css-1ynlp5m{position:relative;width:100%;height:56px;margin-bottom:30px;content:'';} .css-2tyqqs *{display:inline-block;font-family:museoSlab-500,'Arial Narrow','Arial','Helvetica','sans-serif';font-size:24px;font-weight:500;line-height:34px;-webkit-letter-spacing:0.8px;-moz-letter-spacing:0.8px;-ms-letter-spacing:0.8px;letter-spacing:0.8px;}.css-2tyqqs *{display:inline-block;font-family:museoSlab-500,'Arial Narrow','Arial','Helvetica','sans-serif';font-size:24px;font-weight:500;line-height:34px;-webkit-letter-spacing:0.8px;-moz-letter-spacing:0.8px;-ms-letter-spacing:0.8px;letter-spacing:0.8px;} An error recognized in homework, tests, or class participation may be disappointing, but with timely feedback and opportunities to build accurate memory, their brains rewire neural pathways with the faulty information and will avoid the same mistake next time. .css-1ycc0ui{display:inline-block !important;font-family:'canada-type-gibson','Arial','Verdana','sans-serif';font-size:14px;line-height:27px;-webkit-letter-spacing:0.8px;-moz-letter-spacing:0.8px;-ms-letter-spacing:0.8px;letter-spacing:0.8px;text-transform:uppercase;padding-top:24px;margin-bottom:0 !important;}.css-1ycc0ui::before{content:'—';margin-right:9px;color:black;font-size:inherit;} Judy Willis

Help students persevere through mistakes

Learning is a process of going from the unknown to the known and involves detours through uncertainty and mistakes. By encouraging students to think beyond single approaches and giving them opportunities to make decisions and mistakes, you help them build perseverance and mistake tolerance.

Once students have accomplished goals, reminding them of how they overcame challenges boosts their perseverance after mistakes. Help them recall the experiences when with effort and practice, they made fewer mistakes and enjoyed the pleasure of success. For example, “Remember when you were learning to play soccer and you kept trying even though you felt like giving up?” “Think back to when you struggled to play basic chords on the guitar, and now you have mastered so many!” “Do you remember how your first attempts to write were challenging and now it’s easy for you?”

You can also promote opportunities for students to take the risk of making mistakes when you provide examples of people they admire, who have described their own struggles with mistakes. As Michael Jordan has said , “I’ve missed more than 9,000 shots in my career. I’ve lost almost 300 games. I’ve failed over and over and over again in my life. And that is why I succeed.”

You expand perseverance and understanding with questions that have more than one correct answer. Try extending your wait time—don’t give the answers to their questions before all students have enough time to really consider the question and predict possible answers. Ask students questions where they need to explain their reasons and consider alternative or additional solutions .

Utilize Class Discussions

The power of peers is harnessed when you promote class discussions about mistakes. Start by describing some whopper mistakes that you’ve made and how your life went on even after these big mistakes. Invite students to share mistakes they made in the past and how they felt and reacted. Ask them what they would do differently now confronting similar issues.

Students can discuss examples such as these:

- Sending a text message or media posting without considering all possible outcomes

- Judging people too quickly from appearances or initial interactions

- Making preventable mistakes by starting an assignment before reading all the instructions

- Rushing through reading and finding they don’t remember what they read

- Choosing the first multiple-choice answer that seems right without looking at the other options that really included the most correct response

Knowing that their peers have had similar experiences can help students feel less shame about mistakes—everyone makes them, and it’s OK.

Learning from mistakes leads to discovery

When “learning” is errorless and effortless, the acquisition of new knowledge is limited. To be true learners, students need opportunities to construct their understanding, in addition to making and revising mistakes along the way.

Explain to students how learning from mistakes—understanding where they made the mistake—is powerful cement for their brains to construct the correct understanding and solutions. For example, an error recognized in homework, tests, or class participation may be disappointing, but with timely feedback and opportunities to build accurate memory, their brains rewire neural pathways with the faulty information and will avoid the same mistake next time.

This is because the brain has a system that promotes accurate and strong memories in response to mistakes, enhanced by timely feedback . Called the nucleus accumbens or reward center , this storage house of dopamine responds when making predictions, choices, or answers to questions. Through the nucleus accumbens, dopamine is released from its storage area, resulting in the cementing of accurate predictions and the opportunity to revise incorrect ones.