This website uses cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website. Without cookies your experience may not be seamless.

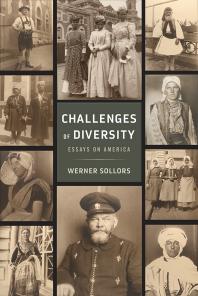

- Challenges of Diversity: Essays on America

In this Book

- Sollors, Werner

- Published by: Rutgers University Press

- View Citation

Table of Contents

- Title Page, Copyright, Dedication

- Introduction

- 1. Literature and Ethnicity

- 2. National Identity and Ethnic Diversity

- 3. Dedicated to a Proposition

- 4. A Critique of Pure Pluralism

- pp. 121-144

- 5. The Multiculturalism Debate as Cultural Text

- pp. 145-204

- Acknowledgments

- pp. 205-206

- pp. 207-215

- About the Author

Additional Information

Project muse mission.

Project MUSE promotes the creation and dissemination of essential humanities and social science resources through collaboration with libraries, publishers, and scholars worldwide. Forged from a partnership between a university press and a library, Project MUSE is a trusted part of the academic and scholarly community it serves.

2715 North Charles Street Baltimore, Maryland, USA 21218

+1 (410) 516-6989 [email protected]

©2024 Project MUSE. Produced by Johns Hopkins University Press in collaboration with The Sheridan Libraries.

Now and Always, The Trusted Content Your Research Requires

Built on the Johns Hopkins University Campus

- Help & FAQ

Challenges of diversity: Essays on America

- Literature and Creative Writing

Research output : Book/Report › Book

What unites and what divides Americans as a nation? Who are we, and can we strike a balance between an emphasis on our divergent ethnic origins and what we have in common? Opening with a survey of American literature through the vantage point of ethnicity, Werner Sollors examines our evolving understanding of ourselves as an Anglo-American nation to a multicultural one and the key role writing has played in that process. Challenges of Diversity contains stories of American myths of arrival (pilgrims at Plymouth Rock, slave ships at Jamestown, steerage passengers at Ellis Island), the powerful rhetoric of egalitarian promise in the Declaration of Independence and the heterogeneous ends to which it has been put, and the recurring tropes of multiculturalism over time (e pluribus unum, melting pot, cultural pluralism). Sollors suggests that although the transformation of this settler country into a polyethnic and self-consciously multicultural nation may appear as a story of great progress toward the fulfillment of egalitarian ideals, deepening economic inequality actually exacerbates the divisions among Americans today.

| Original language | English (US) |

|---|---|

| Publisher | |

| Number of pages | 215 |

| ISBN (Electronic) | 9780813589350 |

| ISBN (Print) | 9780813589336 |

| State | Published - Jan 1 2018 |

ASJC Scopus subject areas

- General Arts and Humanities

Other files and links

- Link to publication in Scopus

- Link to the citations in Scopus

Fingerprint

- E Pluribus Unum Arts & Humanities 100%

- Ellis Island Arts & Humanities 91%

- Multiculturalism Arts & Humanities 86%

- Jamestown Arts & Humanities 84%

- Slave Ship Arts & Humanities 82%

- Plymouth Arts & Humanities 79%

- Cultural Pluralism Arts & Humanities 78%

- Declaration of Independence Arts & Humanities 74%

T1 - Challenges of diversity

T2 - Essays on America

AU - Sollors, Werner

N1 - Publisher Copyright: © 2017 by Rutgers, The State University. All rights reserved.

PY - 2018/1/1

Y1 - 2018/1/1

N2 - What unites and what divides Americans as a nation? Who are we, and can we strike a balance between an emphasis on our divergent ethnic origins and what we have in common? Opening with a survey of American literature through the vantage point of ethnicity, Werner Sollors examines our evolving understanding of ourselves as an Anglo-American nation to a multicultural one and the key role writing has played in that process. Challenges of Diversity contains stories of American myths of arrival (pilgrims at Plymouth Rock, slave ships at Jamestown, steerage passengers at Ellis Island), the powerful rhetoric of egalitarian promise in the Declaration of Independence and the heterogeneous ends to which it has been put, and the recurring tropes of multiculturalism over time (e pluribus unum, melting pot, cultural pluralism). Sollors suggests that although the transformation of this settler country into a polyethnic and self-consciously multicultural nation may appear as a story of great progress toward the fulfillment of egalitarian ideals, deepening economic inequality actually exacerbates the divisions among Americans today.

AB - What unites and what divides Americans as a nation? Who are we, and can we strike a balance between an emphasis on our divergent ethnic origins and what we have in common? Opening with a survey of American literature through the vantage point of ethnicity, Werner Sollors examines our evolving understanding of ourselves as an Anglo-American nation to a multicultural one and the key role writing has played in that process. Challenges of Diversity contains stories of American myths of arrival (pilgrims at Plymouth Rock, slave ships at Jamestown, steerage passengers at Ellis Island), the powerful rhetoric of egalitarian promise in the Declaration of Independence and the heterogeneous ends to which it has been put, and the recurring tropes of multiculturalism over time (e pluribus unum, melting pot, cultural pluralism). Sollors suggests that although the transformation of this settler country into a polyethnic and self-consciously multicultural nation may appear as a story of great progress toward the fulfillment of egalitarian ideals, deepening economic inequality actually exacerbates the divisions among Americans today.

UR - http://www.scopus.com/inward/record.url?scp=85057129818&partnerID=8YFLogxK

UR - http://www.scopus.com/inward/citedby.url?scp=85057129818&partnerID=8YFLogxK

AN - SCOPUS:85057129818

SN - 9780813589336

BT - Challenges of diversity

PB - Rutgers University Press

Set language

Challenges of diversity essays on america.

Werner Sollors Published in 2017

Intro -- Title -- Copyright -- Dedication -- Contents -- Introduction -- 1. Literature and Ethnicity -- 2. National Identity and Ethnic Diversity -- 3. Dedicated to a Proposition -- 4. A Critique o... show more

View online UGent only

Reference details

- Werner Sollors

- For librarians

- For developers

| 01083nam a22002653u 4500 | |||

| 001 | EBC5334094 | ||

| 003 | MiAaPQ | ||

| 005 | 20221216102011.0 | ||

| 006 | m|||||o||d|||||||| | ||

| 007 | cr|cn|||||||||cr||n||||||||| | ||

| 008 | 221216s2017||||xx o|||||||||||eng|d | ||

| 020 | a 9780813589350 | ||

| 035 | a (MiAaPQ)5334094 | ||

| 035 | a (Au-PeEL)5334094 | ||

| 035 | a (CaPaEBR)11536611 | ||

| 035 | a (OCoLC)1030818231 | ||

| 040 | a AU-PeEL b eng c AU-PeEL d AU-PeEL | ||

| 050 | 4 | a PS169 | |

| 082 | a 810.9/358 | ||

| 100 | 1 | a Sollors, Werner. | |

| 245 | 1 | a Challenges of Diversity b Essays on America | |

| 250 | a 1 | ||

| 264 | 1 | a New Brunswick b Rutgers University Press c 2017 | |

| 264 | 4 | c ©2017 | |

| 300 | a 1 online resource (224 pages) | ||

| 336 | a text b txt 2 rdacontent | ||

| 337 | a computer b c 2 rdamedia | ||

| 338 | a online resource b cr 2 rdacarrier | ||

| 505 | a Intro -- Title -- Copyright -- Dedication -- Contents -- Introduction -- 1. Literature and Ethnicity -- 2. National Identity and Ethnic Diversity -- 3. Dedicated to a Proposition -- 4. A Critique of Pure Pluralism -- 5. The Multiculturalism Debate as Cultural Text -- Acknowledgments -- Index -- About the Author | ||

| 520 | a What unites and what divides Americans as a nation? Opening with a survey of American literature through the vantage point of ethnicity, Werner Sollors examines the changing self-understanding of the United States from an Anglo-American to a multicultural country and the role writing has played in that process. | ||

| 588 | a Description based on publisher supplied metadata and other sources. | ||

| 588 | a Electronic reproduction. Ann Arbor, Michigan : ProQuest Ebook Central, YYYY. Available via World Wide Web. Access may be limited to ProQuest Ebook Central affiliated libraries. | ||

| 655 | a Electronic books. | ||

| 776 | 8 | i Print version: a Sollors, Werner t Challenges of Diversity d New Brunswick : Rutgers University Press,c2017 z 9780813589336 | |

| 797 | 2 | a ProQuest (Firm) | |

| 856 | 4 | u https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/unigent-ebooks/detail.action?docID=5334094 | |

Alternative formats

All data below are available with an Open Data Commons Open Database License . You are free to copy, distribute and use the database; to produce works from the database; to modify, transform and build upon the database. As long as you attribute the data sets to the source, publish your adapted database with ODbL license, and keep the dataset open (don't use technical measures such as DRM to restrict access to the database). The datasets are also available as weekly exports .

Collections

- Card catalogue

- Academic Bibliography

- Image library

- Google Books

- Google Scholar

- Registration

- Document delivery (ILL)

- Journals & Articles

- Remote access & VPN

- Live chat offline

- E-mail: [email protected]

- Phone: +32 9 264 94 55

- Addresses & Opening hours

- @libservice

back to top

- Literature & Fiction

- History & Criticism

Sorry, there was a problem.

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

Challenges of Diversity: Essays on America Paperback – October 26, 2017

- Print length 214 pages

- Language English

- Publisher Rutgers University Press

- Publication date October 26, 2017

- Reading age 18 years and up

- Dimensions 6 x 0.5 x 9 inches

- ISBN-10 0813589320

- ISBN-13 978-0813589329

- See all details

Editorial Reviews

About the author, product details.

- Publisher : Rutgers University Press (October 26, 2017)

- Language : English

- Paperback : 214 pages

- ISBN-10 : 0813589320

- ISBN-13 : 978-0813589329

- Reading age : 18 years and up

- Item Weight : 11 ounces

- Dimensions : 6 x 0.5 x 9 inches

- #2,185 in Black & African American Literary Criticism (Books)

- #18,251 in Discrimination & Racism

- #20,296 in African American Demographic Studies (Books)

Customer reviews

| 5 star | 0% | |

| 4 star | 0% | |

| 3 star | 0% | |

| 2 star | 0% | |

| 1 star | 0% |

Our goal is to make sure every review is trustworthy and useful. That's why we use both technology and human investigators to block fake reviews before customers ever see them. Learn more

We block Amazon accounts that violate our community guidelines. We also block sellers who buy reviews and take legal actions against parties who provide these reviews. Learn how to report

No customer reviews

- About Amazon

- Investor Relations

- Amazon Devices

- Amazon Science

- Sell products on Amazon

- Sell on Amazon Business

- Sell apps on Amazon

- Become an Affiliate

- Advertise Your Products

- Self-Publish with Us

- Host an Amazon Hub

- › See More Make Money with Us

- Amazon Business Card

- Shop with Points

- Reload Your Balance

- Amazon Currency Converter

- Amazon and COVID-19

- Your Account

- Your Orders

- Shipping Rates & Policies

- Returns & Replacements

- Manage Your Content and Devices

- Conditions of Use

- Privacy Notice

- Consumer Health Data Privacy Disclosure

- Your Ads Privacy Choices

- A - Z Websites

- Academic Calendar

- Campus Services

- Faculties & Schools

- Student Service Centre

- UBC Directory

- a place of mind

Challenges of Diversity

Essays on America

Sollors is an epochal figure in his field, an inventive and risk-taking thinker who is expanding the scope of African American and American scholarship. Tom Socca, Boston Phoenix

Werner Sollors is a highly sophisticated and discerning commentator on the cluster of issues that Americans associate with the word diversity. The essays collected here are among his finest.' David Hollinger, coeditor of The American Intellectual Tradition: A Sourcebook

A thoroughly thoughtful and thought-provoking read from beginning to end, Challenges of Diversity: Essays on America is an inherently engaging, impressively informed and informative, exceptionally well reasoned, written, and organized work of original scholarship that is unreserved recommended for both community and academic library collections.’ Midwest Book Review

Race and the Rhetoric of Resistance

By Jeffrey B. Ferguson ; Edited by Werner Sollors ; Afterword by George B. Hutchinson

The Psychic Hold of Slavery

Legacies in american expressive culture.

Edited by Soyica Diggs Colbert , Robert J. Patterson , and Aida Levy-Hussen

Writing America

Literary landmarks from walden pond to wounded knee (a reader's companion).

By Shelley Fisher Fishkin

Receive the latest UBC Press news, including events, catalogues, and announcements.

Sign me up! Read past newsletters

our readings and discussions have been focused on establishing a baseline for understanding diversity. In this module, we’ll begin our tour through the four lenses, beginning with history. As we dive

Rutgers University Press Chapter Title: Introduction Book Title: Challenges of Diversity Book Subtitle: Essays on America Book Author(syf : ( 5 1 ( 5 6 2 / / 2 5 S Published by: Rutgers University Press. (2017yf Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1v2xtjj.3 JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected] . Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Rutgers University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Challenges of Diversity This content downloaded from 198.246.186.26 on Mon, 15 Jul 2019 21:57:49 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 3 Introduction Ah me, what are the people whose land I have come to this time, and are they violent and savage, and without justice, or hospitable to strangers, with a godly mind?

—Homer, Odyssey VI:119–121 1 Migration has been a human experience since the earliest times, and epic stories of migrants have accompanied this experience. In the biblical book of Genesis, Adam and Eve are expelled from the Garden of Eden, and the three monotheistic religions have drawn on the story of paradise as an ideal place of origin that man forfeited because of his fallibility. Noah and his family are saved from the environmental disaster of the flood and can start a new life elsewhere. In the book of Exodus, Moses and the Israelites escape from oppressive slavery in Eg ypt. In Vergil’s Aeneid the defeated Trojans leave their city in search of a new country. Such great stories have provided vivid and often heartrending scenes that writers, painters, and composers have returned to. They include scenes of departures, as when Aeneas car - ries his father Anchises out of the burning city and brings his son and the Penates along but loses his wife; of difficult journeys, as when the Israelites This content downloaded from 198.246.186.26 on Mon, 15 Jul 2019 21:57:49 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 4 • Werner Sollors follow a pillar of fire at night and of cloud in the day and miraculously cross the Red Sea to reach the Promised Land; and of arrivals, as when Noah’s ark lands on Mount Ararat after the dove he sent out returns with an olive leaf in her beak. Such epic stories tell tales of the hospitality that Nausikaa extends to Odysseus and that the inhospitable Polyphemus does not. They tell tales of the many obstacles along the way; of the sadness at the loss of family, friends, or homeland; of feeling Fernweh, the yearning for faraway and unknown places; of the hopefulness of new beginnings elsewhere; of the wish for a return from exile in what remains a strange location to the familiar place of origin; or of the migrants’ peculiar sense of seeing the world through the eyes of two places.

Such stories resonate in a world characterized by vast global migra - tions. There were 244 million international migrants in the world in 2015, more than the population of Brazil, the fifth largest country. The United States was the most important host country with 47 million migrants liv - ing there, followed by Germany and Russia, with twelve million migrants each. 2 But for a very long time, Europe was a continent better known for sending migrants abroad, a good many of them to the Americas, than for receiving them. Hence the term “emigration” became more popular than “migration” in Europe. By contrast, American cultural history has been shaped, from colonial times on, by large-scale immigration (as well as by substantial internal migrations), and it is not surprising that some of the ancient migration stories have been invoked and adapted for the American experience. 3 Both the English Puritan settlers who arrived in order to prac- tice their religion freely and the Africans who were enslaved and brought to America against their wills found in their experiences echoes of the Book of Exodus. Thus Cotton Mather wrote about New England: “This New World desert was prefigured long before in the howling deserts where the Israelites passed on their journey to Canaan.” 4 And African Americans created and sang the spiritual “Go Down, Moses,” claiming their freedom with the biblical exclamation, “Let my people go!” When the founding fathers discussed the design of the Great Seal of the United States, Benja - min Franklin proposed “Moses standing on the Shore, and extending his Hand over the Sea, thereby causing the same to overwhelm Pharaoh who is sitting in an open Chariot, a Crown on his Head and a Sword in his Hand.

Rays from a Pillar of Fire in the Clouds reaching to Moses, to express that he acts by Command of the Deity. Motto, Rebellion to Tyrants is This content downloaded from 198.246.186.26 on Mon, 15 Jul 2019 21:57:49 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Introduction • 5 Obedience to God.” 5 Thomas Jefferson thought of choosing the scene of the “children of Israel in the wilderness, led by a cloud by day and a pillar of fire by night.” 6 The final Seal promises a novus ordo seclorum (new order of the ages), an inscription adapted from Vergil’s Eclogues 4:4–10. The motto annuit coeptis also derived from Vergil (Aeneid IX :\f25), and turned a supplication for Jupiter’s assent into the claim that God already “pros- pered this undertaking.” 7 And many an immigrant tale has been called an “American Odyssey.” The United States is a settler-dominated country, the product of a com - posite of waves of immigration and westward migration that have reduced the original inhabitants of the fourth continent to a small minority called Indians. In the mid-nineteenth century, Irish, German, and Scandinavian migrants joined the English settlers, as did the Spanish-speaking popula - tion of the parts of Mexico that the United States annexed. Toward the end of the nineteenth and the beginning of the twentieth century, the so-called new immigration of such south and east European groups as Slavs, Jews, Greeks, and Italians followed, transforming the country from a small English (and English-dominated) colonial offshoot into a polyethnic nation, a process that continued in the second half of the twentieth cen - tury with the still ongoing migratory mass movements of Latin Americans and Asians. The United States has thus become a prototypical immigrant country in which ethnic diversity is a statistical fact as well as a source of debate, of anxiety, and of pride. The statistical fact, well documented by the US Cen - sus Bureau, is readily established: at the moment I am writing this, the tick - ing American population clock shows 324,420,49\f inhabitants, with one immigrant arriving every thirty-three seconds. The American population grew from about 5 million in 1800 to 308 million in 2010, and the total foreign-born population as of 2009 was 38.5 million, among whom 20.5 million came from Latin America, 10.5 million from Asia. \b Divided by race and Hispanic origin, 244 million (or 79 percent) classified themselves as white, 48 million as Hispanic, 39 million as black or African American, 14 million as Asian, and 3 million as American Indian; there were also about 5 million who described themselves as part of two or more races. 9 Divided by ancestry group, 50 million Americans claimed to have German roots, 3\f million Irish origins, 27 million English heritage, and 18 million an Italian background. 10 Yet when looked at through the lens of languages spoken, it This content downloaded from 198.246.186.26 on Mon, 15 Jul 2019 21:57:49 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 6 • Werner Sollors becomes apparent that language loyalty is rather weak for the older immi- grant groups, with only a small fraction of German Americans speaking German and Italian Americans speaking Italian at home. 11 Immigration thus brought an enormous population growth, a fact that made it a source of national pride, all the more so because it took place alongside vast territorial expansions by purchase, conquest, and treaty.

Yet immigration also generated a national population of very diverse ori- gins, and this created times of anxiety and fearfulness over diversity and assimilation. For the Puritans it was inconceivable that Quakers could become part of the Massachusetts Bay Company; for the free whites in a slave-holding country it was self-evident that African slaves and their descendants had no rights that a white man was bound to respect, and plans to resettle freed slaves in Africa became popular for some time. Cot - ton Mather feared that Satan was planning to create “a colony of Irish,” and Benjamin Franklin wondered whether the “swarthy” Germans of Pennsylvania “will shortly be so numerous as to Germanize us instead of our Anglifying them, and will never adopt our language and cus- toms, any more than they can acquire our complexion.” 12 Alexander Hamilton, though he currently enjoys much fame in the world of musicals and is associated with such lines as “Immigrants (We Get the Job Done)” wondered whether, because “ foreigners will generally be apt to bring with them attachments to the persons they have left behind,” their influx to America “must, therefore, tend to produce a heterogeneous compound; to change and corrupt the national spirit; to complicate and confound public opinion; to introduce foreign propensities. In the composition of society, the harmony of the ingredients is all-important, and whatever tends to a discordant intermixture must have an injurious tendency.” 13 Race and religion have often overlapped in calls for exclu - sion, from the nineteenth century to the present. For mid-nineteenth- century Protestant culture, it was the threat of the religious difference that Irish and German Catholic immigrants presented that led to the anti- immigrant Know Nothing movement. Racial anxieties stoked fears of Chinese immigrants and led to the passing of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882 and the Gentlemen’s Agreement with Japan in 1907. The pass- ing of the 1924 Johnson-Reed Act, in the name of US racial homogeneity, restricted each nationality to no more than 2 percent of its presence in the United States as of 1890 (that is, before the “new immigration” This content downloaded from 198.246.186.26 on Mon, 15 Jul 2019 21:57:49 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Introduction • 7 had peaked). And after half a century of high immigration figures, the current political mood, fomented by fears of terrorism, seems again to turn toward restricting the influx of immigrants, with a primary target of the religious difference of Muslims. Diversity implies that it may be challenging to find the unifying ele - ments that hold this heterogeneous population together in a Hamiltonian “harmony of the ingredients.” Nationalisms are often based on myths of shared blood and soil, yet present-day Americans are not of one blood and hail from quite different terrains. Other settler countries chose racial mixing or interpreted figures that seemed to embody such mixing , like the Mexican Virgin of Guadalupe, as symbols of national unity. Mixing races was also common in the parts of Mexico that were annexed, as well as in New Orleans and other parts of formerly French Louisiana where the important category “free man of color” stood between black and white.

For the English colonies and much of the later United States, however, mixing black and white remained a vexed issue through the twentieth cen - tury. Hence turning diversity into unity took different forms. “What is the connecting link between these so different elements,” Alexis de Tocqueville asked in a letter. “How are they welded into one people?” 14 The first three essays in this book pursue this question in various ways and search for the answers given in American texts and symbols. One answer was that enforced assimilation in an English mold, or Anglo-conformity, was the most promising pattern that would unify the population. It made English the dominant language and turned Amer - ica into a graveyard of spoken languages other than English, except only among recent immigrants; currently that means speakers of Spanish and of Asian languages. Anglo-domination also meant that a historical con - sciousness of American culture as an offshoot of England had to be devel - oped and instilled in the population. Though it may always have sounded somewhat odd to hear children with thick immigrant accents sing “Land where our fodders died,” the assertion of Anglo-American patriotism by non-Anglo Americans could sound hollow, at times even duplicitous, when the United States was at war with the countries of origin of millions of immigrants, as was the case during World War I. Furthermore, racially differing groups, most especially blacks and Indians, were excluded or severely marginalized in Anglicization projects. Their status as citizens still needed to be fought for, even though they were clearly a continued and This content downloaded from 198.246.186.26 on Mon, 15 Jul 2019 21:57:49 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 8 • Werner Sollors strong presence in American cultural productions. Could the invocation of shared English origins really serve as a “connecting link” between Ameri- ca’s “different elements”?

Religious typolog y, examined in the opening essay “Literature and Eth - nicity,” was particularly adept in making sacred biblical stories prototypes of secular American tales that could then be seen as their fulfillment on Earth, and the Puritan method of reading migration history in the light of the biblical text has left many traces in the culture. Biblical stories could provide answers to such questions as: Why did we leave? What did we come here to find? And how may we still be connected to the people and places we left behind? For nonadherents to messianic religions and even for nonbelievers, American “civil religion” (Robert Bellah) helped to transfer religious to political sentiments, leaving the meaning of “God” relatively unspecific in the formula “In God We Trust.” Invoking New World Puritan, Pilgrim, and Virginian beginnings—also by people who were not descended from any such group—thus became a way of imagining a cultural connecting link. Feeling like a fellow citizen of George Washington or reciting the founding fathers’ revered political documents could create a feeling of national cohesion that each Fourth of July celebration reenacted. Yet the Declaration of Independence, the sub - ject of the third essay, “Dedicated to a Proposition,” was interpreted and invoked and parodied in heterogeneous ways, sometimes quite irrever - ently, in Massachusetts freedom suits, by immigrants, by Abraham Lincoln and Martin Luther King , and it was echoed differently in the suffrage and labor movements and in the musical Hair. Frederick Douglass’s rhetorical question “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?” stands for many other vantage points from which such documents could be cited for the purpose of demanding urgent changes of the status quo and not yet for celebrat - ing the country’s unity. The “American Creed” was often less a firm set of beliefs in an existing system than a promise that would still need to be ful - filled through struggles and hard work. Beyond Anglo-conformity, religious typolog y, and invocation of founding fathers and their texts, making arrival points stand for ultimate origins could provide some form of family resemblance and American inclusiveness. As the second essay, “National Identity and Ethnic Diver - sity,” suggests, instead of tracing one’s roots back to different places on the globe, one only had to go back to such heterogeneous arrival points This content downloaded from 198.246.186.26 on Mon, 15 Jul 2019 21:57:49 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Introduction • 9 as the Mayflower at Plymouth Rock; a slave ship in Jamestown; and the steerage of a steamship at Castle Garden, Ellis Island, or Angel Island and thus settle on comparable threshold symbols in America. Some immi- grants regarded their moment of arrival on American shores as their true birthday. They sometimes celebrated that birthday with fellow passen - gers, now christened “ship brothers” or “ship sisters.” The shared feeling that a pre-American past had been transcended, that even the Hamilto - nian “attachments to the persons they have left behind” had been severed, could thus paradoxically turn diversity with its “foreign propensities” into another source of unity. This origin story could also lead to an eradication of any past and a reorientation toward the future of things to come. Thus the narrator of one of Edgar Allan Poe’s short stories introduces himself: “Of my coun - try and of my family I have little to say. Ill usage and length of years have driven me from one, and estranged me from the other.” 15 “All the past we leave behind,” Walt Whitman proclaimed in “Pioneers! O Pioneers!” and he continued: “We debouch upon a newer mightier world, varied world, / Fresh and strong the world we seize, world of labor and the march, / Pio - neers! O pioneers!” 16 Willa Cather used Whitman’s poem in a title of one of her novels of immigrant life, while the Norwegian immigrant Ole E.

Rølvaag invoked the text of the poem in one of the volumes of his saga of the settlement by Norwegians in the prairies. What a reader of Herman Melville’s novel Moby-Dick, or, The Whale learns about Captain Ahab’s background is only that he had a “crazy, widowed mother.” 17 In his White- Jacket , Melville wrote that the “Past is, in many things, the foe of mankind,” but that the “Future” is “the Bible of the Free.” 1\b If the past is dead, then migration could be like a rebirth experience. Thus the immigrant Mary Antin begins her memoir, The Promised Land (1912): “I was born, I have lived, and I have been made over. Is it not time to write my life’s story? I am just as much out of the way as if I were dead, for I am absolutely other than the person whose story I have to tell. [. . . ] My second birth was no less a birth because there was no distinct incarnation.” 19 Ethnicity as ancestry could thus lead to the denial, forgetting , or in any event, the overcoming of the past. Here, again, racial difference created an odd counterweight because though self-monitored rebirth, renaming , and other ethnic options were open to the diverse immigrant population that the US Census Bureau considered “white,” “non-whites” were often This content downloaded from 198.246.186.26 on Mon, 15 Jul 2019 21:57:49 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 10 • Werner Sollors believed to remain immutably tied to their past. When a black passenger seated in the white section of a segregated train tells the conductor, “I done quit the race,” he is saying something that is believed to be so impos- sible as to make his statement funny, even at a time when Jim Crow rules were sadistically enforced throughout the society. The nameless narrator- protagonist of Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man fits well into the American “all-the-past-we-leave-behind” camp because we learn little about his par - ents, and he only refers to his grandfather’s one-sentence deathbed maxim, to “overcome’em with yeses, undermin’em with grins, agree’em to death and destruction”—yet the identity shifts of this urban migrant never cross the color line. 20 The color line was crossed, of course, in the extensive lit - erature on racial passing. The word “passing” itself was an Americanism that names the supposed impossibility for characters of mixed-race ances- try to successfully define themselves by their white ancestors and as white, except by deception. In a country that believes in social mobility and wor - ships the upstart as self-made man, racial passing was often a tragic affair.

And for a racially passing person, success furthermore meant abandoning past attachments with a vengeance, for even just acknowledging a colored relative could mean the immediate end of passing , as characters in Jessie Fauset’s or Nella Larsen’s novels rightly fear. Can all Americans perhaps share a form of double consciousness, as their deep history points to other continents? That we are all immigrants could be the answer here, and one finds even the migration across the Bering Strait of the people who would become American Indians merged into this unifying story of a nation of immigrants. The migratory back - ground could be folded into a neatly harmonized family metaphor, as when the Danish immigrant Jacob Riis wrote in his autobiography, The Making of an American (1901): “Alas! I am afraid that thirty years in the land of my children’s birth have left me as much of a Dane as ever. . . . Yet, would you have it otherwise? What sort of a husband is the man going to make who begins by pitching his old mother out of the door to make room for his wife? And what sort of a wife would she be to ask or to stand it?” 21 Mother country and country of marriage partner are thus rec- onciled as unchangeable parts of one single family story. One can surely be proud of both one’s parent and one’s spouse, and spouses should not demand the discarding of their mothers-in-law. One also notices Riis’s weighty phrase, “land of my children’s birth.” As the dominant cultural This content downloaded from 198.246.186.26 on Mon, 15 Jul 2019 21:57:49 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Introduction • 11 outlook may have subtly shifted from following the example of one’s parents to imagining a better future for one’s children, the importance of success stories of upward mobility is not negligible for this reorienta - tion to work. And the fact that American-born children may be the first American citizens in immigrant families intensifies this forward-looking identification. Yet in situations of war or other great conflicts, the immigrants’ parent - age or former citizenship, their “foreign propensities” and “attachments to the persons they have left behind,” could matter again. Public anxieties could emerge and be stoked by rhetoric, culminating in strong majoritar - ian beliefs in the incompatibility of some groups who are believed to tend to “change and corrupt the national spirit.” Attempts to stress and normal - ize hyphenated double identities as family stories did become particularly troubling during World War I, when national loyalty had to be reinforced and seemed to demand “pitching one’s old mother out of the door.” Hence the fast-track abandonment of the hyphens in Americanization campaigns, the Ford Motor Company Melting Pot rituals, and the slogans promis- ing “Americans All!” Yet the more melting-pot catalogs listed the hetero - geneous pasts with the intention of making sure that they would be left behind, the more these differing pasts could also be reclaimed now that they had been named. It is thus telling that Randolph Bourne’s utopian-cosmopolitan notion of a “Transnational America” as well as Horace Kallen’s concept of cultural pluralism emerged in opposition to the wartime assimilation project of the Americanizers. Bourne thought Americanization would lead to the dominance of vapid, lowest-common-denominator popular culture of cheap magazines and movies and eradicate the country’s vibrant cultural- linguistic diversity. Kallen believed that assimilation was a violation of the democracy of ethnic groups that a country like Switzerland realized more fully than melting-pot America, for assimilationists fail to recognize that “men cannot change their grandfathers.” 22 As Philip Gleason showed, this belief in the immutability of ethnoracial origins was a feature that early pluralist thinking shared with that of racists, and neither believed in assim - ilation. Did pluralists, to use Kwame Anthony Appiah’s formulation, sim - ply “replace one ethnocentrism with many”?

23 The complex and somewhat surprising story of the origins of cultural pluralism is the subject of the fourth essay, “A Critique of Pure Pluralism.” This content downloaded from 198.246.186.26 on Mon, 15 Jul 2019 21:57:49 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 12 • Werner Sollors From such beginnings, there slowly emerged a new sense of Ameri- canness that emphasized more and more the aspects of ethnic diversity as constitutive and hopefully unifying features of the country. Rather than generating anxiety, diversity could now become a source of national pride, generating the belief that the inhabitants’ “heterogeneous com - pound” was, in fact, the answer to the quest for national unity. The pro - cess was interrupted by World War II, when the search for “common ground” (also the title of a magazine edited by the Slovenian immigrant Louis Adamic) summoning national unity out of diversity was challenged by the fear of new sets of US relatives of wartime enemies: fifth colum - nists from the European Axis countries, but most especially West Coast Japanese Americans who were held in detention camps for the duration of the war, even though the majority of them held US citizenship. During the Cold War, new fears were targeted toward immigrants who had Com - munist backgrounds and affiliations or who were merely suspected of Communist sympathies. Big changes in race relations and in immigration policies came in the course of the 19\f0s. Neither the Americanizers’ assimilation project nor Bourne and Kallen’s pluralism had paid much attention to African Amer - icans and Indians in their models of transnational or pluralist America; they remained “encapsulated in white ethnocentrism,” as John Higham put it.

24 However, the successes of the civil rights movement forced a new rec- ognition of the privilege of whiteness that earlier models of Americanness had quietly taken for granted or simply ignored in their reflections. The example of African Americans’ struggle for equality inspired the Ameri- can Indian movement, women’s liberation, the struggle for gay rights, and other movements and led to more vocal demands for a more universally egalitarian country, measured by its inclusiveness of previously excluded groups. This was reflected in the 19\f5 Immigration and Naturalization Act that abolished racially motivated national origins quotas. The recognition also gained dominance that past discriminations on the basis of categories like race, gender, and religion needed not just corrections on the individual level but “affirmative action” toward groups that had been discriminated against as groups. This recognition required strenuous attacks on exclu - sionary practices of the past and generated a new hopefulness that stressing what had divided Americans in the past could become the connecting link of the present. This emphasis on group rights is what became known in the This content downloaded from 198.246.186.26 on Mon, 15 Jul 2019 21:57:49 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Introduction • 13 1980s as multiculturalism to its advocates and, a decade later, as identity politics to its critics.

The transformation of an Anglo-American settler country into a poly - ethnic and self-consciously multicultural nation may thus appear as a story of great progress toward the fulfillment of egalitarian ideals in a more and more inclusive society. When seen through the lens of mul - ticulturalism, one could imagine a success story: that a slow equaliza - tion process among different status groups had affirmed the “American Dream” of high social and economic mobility. There are more women in leadership positions than before the 19\f0s, and African Americans and Latinos have a far stronger representation in governmental bodies and educational structures, in business, health care, law, and the military. Dis- crimination on the grounds of race, sex, national origin, or sexual orien - tation is being monitored, and nasty jokes or spiteful comments about minorities are no longer common currency or politely tolerated in many areas of American life. 25 Yet it is also the case that classes have been drifting apart in America.

The status and share in income of poor people has been declining , while that of the highest-earning strata has increased dramatically. Whereas the bottom half made 19.9 percent of the pretax national income in 1980, their share has declined to a mere 12.5 percent in 2014, while that of the top 1 percent has risen from 10.7 percent in 1980 to 20.2 percent in 2014. 26 And this American situation has global relevance, as nowadays the world’s eight richest men—among them six Americans—own as much as the world’s bottom half, or 3.\f billion people. 27 Economic equalization is not in evidence, then, and multicultur - alism’s focus on group rights may have made it harder for the poorer half of Americans to form intergroup alliances, while antisocial tax and healthcare legislation can be advanced in the name of opposing iden - tity politics, thus further deepening the class divide and accelerating the movement toward a multiculturally styled plutocracy. How could social movements be built, Richard Rorty asked, that would attempt to fight the crimes of social selfishness with the same vigor that mul - ticulturalists have focused on the crimes of sadism against minority groups? 2\b Group divisions, reinforced by the bureaucratic procedures of what David Hollinger criticized as America’s “ethnoracial pentagon,” a “rigidification of exactly those ascribed distinctions between persons This content downloaded from 198.246.186.26 on Mon, 15 Jul 2019 21:57:49 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 14 • Werner Sollors that various universalists and cosmopolitans have so long sought to diminish,” seemed to assume a much more permanent and quasi-natu - ral status, obscuring more malleable connections by choice and around shared interests. 29 Pluralism also alienated radical young intellectuals, as Higham observed, “from the rank and file of the American working peo - ple—that is, from all the people except the culturally distinctive minori- ties.” 30 And those nonminority working people could now be mobilized by populist politicians as “forgotten Americans” who consider them - selves free of the racisms of the past but express forceful, and even spite - ful, resentment against those minority groups who were singled out for policies of collective redress or benefit, and against the political and educational elites as well as the liberal press they hold responsible for devising and defending these policies. Multiculturally oriented intellec- tuals in turn register and indict this reaction as racism, xenophobia, and anti-intellectualism. In the face of growing class inequality, multicultur - alism may no longer serve as the “connecting link” between the “differ - ent elements of America,” but might instead enable potentially explosive group divisions and help to create that “discordant intermixture” with “an injurious tendency” that Hamilton feared. Perhaps it is no coinci- dence that the debate about multiculturalism was drawn to the dysto - pian imagination of George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four, a novel that has again moved to the center of public attention. (Erich Fromm’s use of the term “mobile truth” in his 19\f1 afterword to Orwell’s novel also has assumed a new relevance at the present moment.) The last essay in this volume, “The Multiculturalism Debate as Cultural Text,” focusing on the so-called culture wars, includes the sentence, “There may now be many multicultural men and women who are completely disconnected from any proletariat anywhere, and multicultural internationalism may even serve as the marker that separates these intellectuals from people, making multiculturalists instead part of a global ruling class.” Multicul - turalism may thus need a strong infusion of social consciousness and a steady, active attention to economic inequalities. But what other model of integration could we turn to now, when an immigrant arrives every thirty-three seconds in the United States, than multiculturalism’s affir - mation of diversity as a sign of strength? Which tales of hospitality toward refugees and strangers will the cur - rent moment generate in the United States or, as a matter of fact, any - where in the world, since the United States is no longer exceptional as a This content downloaded from 198.246.186.26 on Mon, 15 Jul 2019 21:57:49 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Introduction • 15 host country to large numbers of immigrants. Many other countries have become the destination of global flows of refugees and migrants. More than 140 countries, among them the United States, signed the 1951 United Nations Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, an important international treaty that was expanded by the 19\f7 Protocol and reaffirmed by the 201\f New York Declaration. 31 That most recent declaration stipu - lates “a shared responsibility to manage large movements of refugees and migrants in a humane, sensitive, compassionate and people-centred man - ner.” It continues: Large movements of refugees and migrants must have comprehensive policy support, assistance and protection, consistent with States’ obligations under international law. We also recall our obligations to fully respect their human rights and fundamental freedoms, and we stress their need to live their lives in safety and dignity. We pledge our support to those affected today as well as to those who will be part of future large movements. [. . . ] We strongly condemn acts and manifestations of racism, racial discrim - ination, xenophobia and related intolerance against refugees and migrants, and the stereotypes often applied to them, including on the basis of reli- gion or belief. Diversity enriches every society and contributes to social cohesion. One can only hope that the governments of member countries will live up to the language and spirit of the United Nations and that the stories that dominate our time will resemble Nausikaa’s caring hospitality and not Polyphemus’s violence.

The Illustrations Each essay is accompanied by an image, inviting the reader to ponder how one might be able to visualize multicultural America in a single telling image. Edward A. Wilson, critically casting America as El Dorado (1913; see Figure 1, the opening image of the first essay), imagined the arrival of an immigrant family in the harbor of New York not with the Statue of Liberty but with a golden Fortuna-like goddess who rolls the dice of chance toward the newcomers, thus casting a critical question mark on the myth of America. The representational shortcomings of such artwork This content downloaded from 198.246.186.26 on Mon, 15 Jul 2019 21:57:49 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 16 • Werner Sollors as Howard Chandler Christy’s poster Americans All! (1917, see Figure 2, the frontispiece to the second essay) are immediately apparent, as the Christy girl is a poor allegorical embodiment of the varieties of physical features that the list of ethnic names suggests. The Enlightenment-in - spired egalitarian promise of “All Men Are Created Equal” remains an ideological foundation of any multicultural sensibility, but John Trum - bull’s 1819 painting Declaration of Independence (in its two-dollar bill adaptation, the frontispiece of the third essay, Figure 3) does little to give visual expression to American ethnic diversity. Grant E. Hamil - ton’s cartoon Uncle Sam Is a Man of Strong Features (1898, Figure 4, the image opening the fourth essay) is a valiant, Arcimboldo-style attempt to transform a virtual catalogue of all major ethnic groups—not only English, German, Irish, Swede, French, Italian, Greek, and Russian, but also Indian, Negro, Hebrew, Cuban, Esquimaux, Hawaiian, Turk, and Chinese—into the facial features of the familiar Uncle Sam figure. Uncle Sam’s beard, composed by the only female figure, a stout Quaker woman with piously folded hands, forms a comic counterpoint to the rather wor - risome male specimens. Whether a twenty-first-century viewer is more startled by the Negro and Hawaiian as thick-lipped dark pupils of the eyes, by the big-nosed Hebrew and shiftless Italian as ears, or by the stoic Indian with his outstretched arms as nose and eyebrows, one simply has to wonder about Grant’s employment of grossly stereotypical ethnic fea - tures and his need to give captions to all those figures in order to make the heterogeneous ingredients of America more readily legible. The fifth and last essay opens with a diagram (Figure 5) adapted from Stewart G. and Mildred Wiese Cole’s Minorities and the American Promise (1954) rather than an image, in order to highlight the significance of the now forgot - ten history of mid-century research about cultural diversity and inter - cultural education. In the absence of a single trademark-like image that would recognizably signal America in all its diversity, the cover designer arranged ten of Francis Augustus Sherman’s Ellis Island portrait photo - graphs from the years 1905 to 1920. 32 Sherman worked as chief registry clerk with the Immigration Division of Ellis Island and thus had ample opportunity to get migrants who passed through, or were detained at Ellis Island to pose for him. Starting with the image at the top center of the cover, “Three Women from Guadeloupe,” the photographs represent, in clockwise direction, “Greek soldier,” “Ruthenian Woman,” “Slova - kian Women,” “Algerian Man,” “Danish man,” “Protestant Woman from This content downloaded from 198.246.186.26 on Mon, 15 Jul 2019 21:57:49 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Introduction • 17 Zuid-Beveland, The Netherlands,” “Greek Woman,” “Russian Cossacks,” and “Bavarian Man.” Dressed in traditional costumes, many of Sherman’s subjects stand in front of recognizable Ellis Island buildings, often look straight at the camera, and thus manage to prompt the viewer to wonder about their individual stories, the meaning of migration, and the chal - lenges of diversity.

This content downloaded from 198.246.186.26 on Mon, 15 Jul 2019 21:57:49 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

GET YOUR EXPERT ANSWER ON STUDYDADDY

Post your own question and get a custom answer

Have a similar question?

Continue to edit or attach image(s).

Fast and convenient

Simply post your question and get it answered by professional tutor within 30 minutes. It's as simple as that!

Any topic, any difficulty

We've got thousands of tutors in different areas of study who are willing to help you with any kind of academic assignment, be it a math homework or an article.

100% Satisfied Students

Join 3,4 million+ members who are already getting homework help from StudyDaddy!

(Stanford users can avoid this Captcha by logging in.)

Stanford Libraries will be undergoing a system upgrade beginning Friday, June 21 at 5pm through Sunday, June 23.

During the upgrade, libraries will be open regular hours and eligible materials may be checked out. Item status and availability information may not be up to date. Requests cannot be submitted and My Library Account will not be available during the upgrade.

- Send to text email RefWorks EndNote printer

Challenges of diversity : essays on America

Available online.

- EBSCO Academic Comprehensive Collection

More options

- Find it at other libraries via WorldCat

- Contributors

Description

Creators/contributors, contents/summary.

- Frontmatter

- Challenges of Diversity

- Introduction

- 1. Literature and Ethnicity

- 2. National Identity and Ethnic Diversity

- 3. Dedicated to a Proposition

- 4. A Critique of Pure Pluralism

- 5. The Multiculturalism Debate as Cultural Text

- Acknowledgments

Bibliographic information

Browse related items.

- Stanford Home

- Maps & Directions

- Search Stanford

- Emergency Info

- Terms of Use

- Non-Discrimination

- Accessibility

© Stanford University , Stanford , California 94305 .

- Advanced search

Challenges of diversity : essays on America / Werner Sollors

Full Text available online

Advanced Search

- Browse Our Shelves

- Best Sellers

- Digital Audiobooks

- Featured Titles

- New This Week

- Staff Recommended

- Reading Lists

- Upcoming Events

- Ticketed Events

- Science Book Talks

- Past Events

- Video Archive

- Online Gift Codes

- University Clothing

- Goods & Gifts from Harvard Book Store

- Hours & Directions

- Newsletter Archive

- Frequent Buyer Program

- Signed First Edition Club

- Signed New Voices in Fiction Club

- Off-Site Book Sales

- Corporate & Special Sales

- Print on Demand

| Our Shelves |

- All Our Shelves

- Academic New Arrivals

- New Hardcover - Biography

- New Hardcover - Fiction

- New Hardcover - Nonfiction

- New Titles - Paperback

- African American Studies

- Anthologies

- Anthropology / Archaeology

- Architecture

- Asia & The Pacific

- Astronomy / Geology

- Boston / Cambridge / New England

- Business & Management

- Career Guides

- Child Care / Childbirth / Adoption

- Children's Board Books

- Children's Picture Books

- Children's Activity Books

- Children's Beginning Readers

- Children's Middle Grade

- Children's Gift Books

- Children's Nonfiction

- Children's/Teen Graphic Novels

- Teen Nonfiction

- Young Adult

- Classical Studies

- Cognitive Science / Linguistics

- College Guides

- Cultural & Critical Theory

- Education - Higher Ed

- Environment / Sustainablity

- European History

- Exam Preps / Outlines

- Games & Hobbies

- Gender Studies / Gay & Lesbian

- Gift / Seasonal Books

- Globalization

- Graphic Novels

- Hardcover Classics

- Health / Fitness / Med Ref

- Islamic Studies

- Large Print

- Latin America / Caribbean

- Law & Legal Issues

- Literary Crit & Biography

- Local Economy

- Mathematics

- Media Studies

- Middle East

- Myths / Tales / Legends

- Native American

- Paperback Favorites

- Performing Arts / Acting

- Personal Finance

- Personal Growth

- Photography

- Physics / Chemistry

- Poetry Criticism

- Ref / English Lang Dict & Thes

- Ref / Foreign Lang Dict / Phrase

- Reference - General

- Religion - Christianity

- Religion - Comparative

- Religion - Eastern

- Romance & Erotica

- Science Fiction

- Short Introductions

- Technology, Culture & Media

- Theology / Religious Studies

- Travel Atlases & Maps

- Travel Lit / Adventure

- Urban Studies

- Wines And Spirits

- Women's Studies

- World History

- Writing Style And Publishing

| Gift Cards |

Challenges of Diversity: Essays on AmericaWhat unites and what divides Americans as a nation? Who are we, and can we strike a balance between an emphasis on our divergent ethnic origins and what we have in common? Opening with a survey of American literature through the vantage point of ethnicity, Werner Sollors examines our evolving understanding of ourselves as an Anglo-American nation to a multicultural one and the key role writing has played in that process. Challenges of Diversity contains stories of American myths of arrival (pilgrims at Plymouth Rock, slave ships at Jamestown, steerage passengers at Ellis Island), the powerful rhetoric of egalitarian promise in the Declaration of Independence and the heterogeneous ends to which it has been put, and the recurring tropes of multiculturalism over time (e pluribus unum, melting pot, cultural pluralism). Sollors suggests that although the transformation of this settler country into a polyethnic and self-consciously multicultural nation may appear as a story of great progress toward the fulfillment of egalitarian ideals, deepening economic inequality actually exacerbates the divisions among Americans today. There are no customer reviews for this item yet.  Classic Totes Tote bags and pouches in a variety of styles, sizes, and designs , plus mugs, bookmarks, and more! Shipping & Pickup We ship anywhere in the U.S. and orders of $75+ ship free via media mail! Noteworthy Signed Books: Join the Club! Join our Signed First Edition Club (or give a gift subscription) for a signed book of great literary merit, delivered to you monthly.  Harvard Square's Independent Bookstore © 2024 Harvard Book Store All rights reserved Contact Harvard Book Store 1256 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 Tel (617) 661-1515 Toll Free (800) 542-READ Email [email protected] View our current hours » Join our bookselling team » We plan to remain closed to the public for two weeks, through Saturday, March 28 While our doors are closed, we plan to staff our phones, email, and harvard.com web order services from 10am to 6pm daily. Store Hours Monday - Saturday: 9am - 11pm Sunday: 10am - 10pm Holiday Hours 12/24: 9am - 7pm 12/25: closed 12/31: 9am - 9pm 1/1: 12pm - 11pm All other hours as usual. Map Find Harvard Book Store » Online Customer Service Shipping » Online Returns » Privacy Policy » Harvard University harvard.edu »

Changing Faces: Immigrants and Diversity in the Twenty-First CenturySubscribe to this week in foreign policy, audrey singer and as audrey singer james m. lindsay jml james m. lindsay. June 1, 2003 Herman Melville exaggerated 160 years ago when he wrote, “You cannot spill a drop of American blood without spilling the blood of the world.” However, the results of the 2000 Census show that his words accurately describe the United States of today. Two decades of intensive immigration are rapidly remaking our racial and ethnic mix. The American mosaic—which has always been complex—is becoming even more intricate. If diversity is a blessing, America has it in abundance. But is diversity a blessing? In many parts of the world the answer has been no. Ethnic, racial, and religious differences often produce violence—witness the disintegration of Yugoslavia, the genocide in Rwanda, the civil war in Sudan, and the “Troubles” in Northern Ireland. Against this background the United States has been a remarkable exception. This is not to say it is innocent of racism, bigotry, or unequal treatment—the slaughter of American Indians, slavery, Jim Crow segregation, and the continuing gap between whites and blacks on many socioeconomic indicators make clear otherwise. However, to a degree unparalleled anywhere else, America has knitted disparate peoples into one nation. The success of that effort is visible not just in America’s tremendous prosperity, but also in the patriotism that Americans, regardless of their skin color, ancestral homeland, or place of worship, feel for their country. America has managed to build one nation out of many people for several reasons. Incorporating newcomers from diverse origins has been part of its experience from the earliest colonial days—and is ingrained in the American culture. The fact that divisions between Congregationalists and Methodists or between people of English and Irish ancestry do not animate our politics today attests not to homogeneity but to success—often hard earned—in bridging and tolerating differences. America’s embrace of “liberty and justice for all” has been the backdrop that has promoted unity. The commitment to the ideals enshrined in the Declaration of Independence gave those denied their rights a moral claim on the conscience of the majority—a claim redeemed most memorably by the civil rights movement. America’s two-party system has fostered unity by encouraging ethnic and religious groups to join forces rather than build sectarian parties that would perpetuate demographic divides. Furthermore, economic mobility has created bridges across ethnic, religious, and racial lines, thereby blurring their overlap with class divisions and diminishing their power to fuel conflict. Read the full chapter (PDF-191kb) More on the forthcoming book, Agenda for the Nation . Brookings Metro Foreign Policy Jennifer Lee May 18, 2022 William H. Frey January 11, 2021 February 19, 2020 Have a language expert improve your writingCheck your paper for plagiarism in 10 minutes, generate your apa citations for free.

How to Write a Diversity Essay | Tips & ExamplesPublished on November 1, 2021 by Kirsten Courault . Revised on May 31, 2023. Table of contentsWhat is a diversity essay, identify how you will enrich the campus community, share stories about your lived experience, explain how your background or identity has affected your life, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about college application essays. Diversity essays ask students to highlight an important aspect of their identity, background, culture, experience, viewpoints, beliefs, skills, passions, goals, etc. Diversity essays can come in many forms. Some scholarships are offered specifically for students who come from an underrepresented background or identity in higher education. At highly competitive schools, supplemental diversity essays require students to address how they will enhance the student body with a unique perspective, identity, or background. In the Common Application and applications for several other colleges, some main essay prompts ask about how your background, identity, or experience has affected you. Why schools want a diversity essayMany universities believe a student body representing different perspectives, beliefs, identities, and backgrounds will enhance the campus learning and community experience. Admissions officers are interested in hearing about how your unique background, identity, beliefs, culture, or characteristics will enrich the campus community. Through the diversity essay, admissions officers want students to articulate the following:

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.Think about what aspects of your identity or background make you unique, and choose one that has significantly impacted your life. For some students, it may be easy to identify what sets them apart from their peers. But if you’re having trouble identifying what makes you different from other applicants, consider your life from an outsider’s perspective. Don’t presume your lived experiences are normal or boring just because you’re used to them. Some examples of identities or experiences that you might write about include the following:

Include vulnerable, authentic stories about your lived experiences. Maintain focus on your experience rather than going into too much detail comparing yourself to others or describing their experiences. Keep the focus on youTell a story about how your background, identity, or experience has impacted you. While you can briefly mention another person’s experience to provide context, be sure to keep the essay focused on you. Admissions officers are mostly interested in learning about your lived experience, not anyone else’s. When I was a baby, my grandmother took me in, even though that meant postponing her retirement and continuing to work full-time at the local hairdresser. Even working every shift she could, she never missed a single school play or soccer game. She and I had a really special bond, even creating our own special language to leave each other secret notes and messages. She always pushed me to succeed in school, and celebrated every academic achievement like it was worthy of a Nobel Prize. Every month, any leftover tip money she received at work went to a special 509 savings plan for my college education. When I was in the 10th grade, my grandmother was diagnosed with ALS. We didn’t have health insurance, and what began with quitting soccer eventually led to dropping out of school as her condition worsened. In between her doctor’s appointments, keeping the house tidy, and keeping her comfortable, I took advantage of those few free moments to study for the GED. In school pictures at Raleigh Elementary School, you could immediately spot me as “that Asian girl.” At lunch, I used to bring leftover fun see noodles, but after my classmates remarked how they smelled disgusting, I begged my mom to make a “regular” lunch of sliced bread, mayonnaise, and deli meat. Although born and raised in North Carolina, I felt a cultural obligation to learn my “mother tongue” and reconnect with my “homeland.” After two years of all-day Saturday Chinese school, I finally visited Beijing for the first time, expecting I would finally belong. While my face initially assured locals of my Chinese identity, the moment I spoke, my cover was blown. My Chinese was littered with tonal errors, and I was instantly labeled as an “ABC,” American-born Chinese. I felt culturally homeless. Speak from your own experienceHighlight your actions, difficulties, and feelings rather than comparing yourself to others. While it may be tempting to write about how you have been more or less fortunate than those around you, keep the focus on you and your unique experiences, as shown below. I began to despair when the FAFSA website once again filled with red error messages. I had been at the local library for hours and hadn’t even been able to finish the form, much less the other to-do items for my application. I am the first person in my family to even consider going to college. My parents work two jobs each, but even then, it’s sometimes very hard to make ends meet. Rather than playing soccer or competing in speech and debate, I help my family by taking care of my younger siblings after school and on the weekends. “We only speak one language here. Speak proper English!” roared a store owner when I had attempted to buy bread and accidentally used the wrong preposition. In middle school, I had relentlessly studied English grammar textbooks and received the highest marks. Leaving Seoul was hard, but living in West Orange, New Jersey was much harder一especially navigating everyday communication with Americans. After sharing relevant personal stories, make sure to provide insight into how your lived experience has influenced your perspective, activities, and goals. You should also explain how your background led you to apply to this university and why you’re a good fit. Include your outlook, actions, and goalsConclude your essay with an insight about how your background or identity has affected your outlook, actions, and goals. You should include specific actions and activities that you have done as a result of your insight. One night, before the midnight premiere of Avengers: Endgame , I stopped by my best friend Maria’s house. Her mother prepared tamales, churros, and Mexican hot chocolate, packing them all neatly in an Igloo lunch box. As we sat in the line snaking around the AMC theater, I thought back to when Maria and I took salsa classes together and when we belted out Selena’s “Bidi Bidi Bom Bom” at karaoke. In that moment, as I munched on a chicken tamale, I realized how much I admired the beauty, complexity, and joy in Maria’s culture but had suppressed and devalued my own. The following semester, I joined Model UN. Since then, I have learned how to proudly represent other countries and have gained cultural perspectives other than my own. I now understand that all cultures, including my own, are equal. I still struggle with small triggers, like when I go through airport security and feel a suspicious glance toward me, or when I feel self-conscious for bringing kabsa to school lunch. But in the future, I hope to study and work in international relations to continue learning about other cultures and impart a positive impression of Saudi culture to the world. The smell of the early morning dew and the welcoming whinnies of my family’s horses are some of my most treasured childhood memories. To this day, our farm remains so rural that we do not have broadband access, and we’re too far away from the closest town for the postal service to reach us. Going to school regularly was always a struggle: between the unceasing demands of the farm and our lack of connectivity, it was hard to keep up with my studies. Despite being a voracious reader, avid amateur chemist, and active participant in the classroom, emergencies and unforeseen events at the farm meant that I had a lot of unexcused absences. Although it had challenges, my upbringing taught me resilience, the value of hard work, and the importance of family. Staying up all night to watch a foal being born, successfully saving the animals from a minor fire, and finding ways to soothe a nervous mare afraid of thunder have led to an unbreakable family bond. Our farm is my family’s birthright and our livelihood, and I am eager to learn how to ensure the farm’s financial and technological success for future generations. In college, I am looking forward to joining a chapter of Future Farmers of America and studying agricultural business to carry my family’s legacy forward. Tailor your answer to the universityAfter explaining how your identity or background will enrich the university’s existing student body, you can mention the university organizations, groups, or courses in which you’re interested. Maybe a larger public school setting will allow you to broaden your community, or a small liberal arts college has a specialized program that will give you space to discover your voice and identity. Perhaps this particular university has an active affinity group you’d like to join. Demonstrating how a university’s specific programs or clubs are relevant to you can show that you’ve done your research and would be a great addition to the university. At the University of Michigan Engineering, I want to study engineering not only to emulate my mother’s achievements and strength, but also to forge my own path as an engineer with disabilities. I appreciate the University of Michigan’s long-standing dedication to supporting students with disabilities in ways ranging from accessible housing to assistive technology. At the University of Michigan Engineering, I want to receive a top-notch education and use it to inspire others to strive for their best, regardless of their circumstances. If you want to know more about academic writing , effective communication , or parts of speech , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples. Academic writing

Communication

Parts of speech

In addition to your main college essay , some schools and scholarships may ask for a supplementary essay focused on an aspect of your identity or background. This is sometimes called a diversity essay . Many universities believe a student body composed of different perspectives, beliefs, identities, and backgrounds will enhance the campus learning and community experience. Admissions officers are interested in hearing about how your unique background, identity, beliefs, culture, or characteristics will enrich the campus community, which is why they assign a diversity essay . To write an effective diversity essay , include vulnerable, authentic stories about your unique identity, background, or perspective. Provide insight into how your lived experience has influenced your outlook, activities, and goals. If relevant, you should also mention how your background has led you to apply for this university and why you’re a good fit. Cite this Scribbr articleIf you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator. Courault, K. (2023, May 31). How to Write a Diversity Essay | Tips & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved June 18, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/college-essay/diversity-essay/ Is this article helpful? Kirsten CouraultOther students also liked, how to write about yourself in a college essay | examples, what do colleges look for in an essay | examples & tips, how to write a scholarship essay | template & example, get unlimited documents corrected. ✔ Free APA citation check included ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

Oops! Looks like we're having trouble connecting to our server.Refresh your browser window to try again. Did you store your login in a trusted browser? Here's how to look it up:In Chrome on PC/Mac : Choose the menu icon (top right), then choose "Settings." At the bottom of the Settings page, choose "Show advanced settings." In the "Passwords and Forms" area, choose "Manage Passwords." In Firefox on PC : Choose the menu icon (top right), then "Options" (the gear icon), then choose the "Security" tab. Click on the "Saved Passwords" button to see the logins you're storing, and if needed, "Show Passwords" to display their passwords. In Firefox on Mac : Choose Firefox/Preferences, then click the sidebar icon that looks like a padlock (Security). Click on the "Saved Passwords" button to see the logins you're storing, and if needed, "Show Passwords" to display their passwords. In IE on PC : Choose the gear icon (Tools), then "Internet options." Choose the "Content" tab, then, in the "Autocomplete" area, choose "Settings. Then pick "Manage Passwords" to see your stored logins. In Safari on Mac/PC : Choose Safari/Preferences and then "Passwords." Your saved usernames and passwords will be listed there. On iPad or iPhone : Go to Settings/Safari/Passwords & AutoFill. Choose "Saved Passwords," enter your passcode if prompted, and then look for www.bibliovault.org in the list of passwords. Select the arrow to see your username and password. If you can't find your login in your browser, you can alternately retrieve your username and/or reset your password . Still stuck? Email [email protected] .PUBLISHER LOGIN READERS Browse our collection . PUBLISHERS See BiblioVault's publisher services . STUDENT SERVICES Files for college accessibility offices.

UChicago Accessibility Resources BiblioVault ® 2001 - 2024 The University of Chicago Press What is Generative AI?Generative AI enables users to quickly generate new content based on a variety of inputs. Inputs and outputs to these models can include text, images, sounds, animation, 3D models, or other types of data. How Does Generative AI Work?Generative AI models use neural networks to identify the patterns and structures within existing data to generate new and original content. One of the breakthroughs with generative AI models is the ability to leverage different learning approaches, including unsupervised or semi-supervised learning for training. This has given organizations the ability to more easily and quickly leverage a large amount of unlabeled data to create foundation models. As the name suggests, foundation models can be used as a base for AI systems that can perform multiple tasks. Examples of foundation models include GPT-3 and Stable Diffusion, which allow users to leverage the power of language. For example, popular applications like ChatGPT, which draws from GPT-3, allow users to generate an essay based on a short text request. On the other hand, Stable Diffusion allows users to generate photorealistic images given a text input. How to Evaluate Generative AI Models?The three key requirements of a successful generative AI model are:

Figure 1: The three requirements of a successful generative AI model. How to Develop Generative AI Models?There are multiple types of generative models, and combining the positive attributes of each results in the ability to create even more powerful models. Below is a breakdown:

Figure 2: The diffusion and denoising process. A diffusion model can take longer to train than a variational autoencoder (VAE) model, but thanks to this two-step process, hundreds, if not an infinite amount, of layers can be trained, which means that diffusion models generally offer the highest-quality output when building generative AI models. Additionally, diffusion models are also categorized as foundation models, because they are large-scale, offer high-quality outputs, are flexible, and are considered best for generalized use cases. However, because of the reverse sampling process, running foundation models is a slow, lengthy process. Learn more about the mathematics of diffusion models in this blog post.